Abstract

Introduction

Social media may play a role in adolescent sexual development. The limited research on social media use and sexual development has found both positive and negative influences. The focus of this study is on sexual agency: a positive sexual outcome. This paper describes the protocol for the Social Networks and Agency Project (SNAP) study which aims to examine the relationship between online and offline social networks and the development of healthy relationships and sexual agency in adolescence.

Methods and analysis

The SNAP study is a mixed methods interdisciplinary longitudinal study. Over an 18-month period, adolescents aged 15–17 years at recruitment complete three questionnaires (including demographics, sexual behaviour, sexual agency and social networks); three in-depth interviews; and fortnightly online diaries describing their sexual behaviour and snapshots of their social networks that week. Longitudinal analyses will be used to describe changes in sexual behaviour and experiences over time, sexual agency, social media use, and social network patterns. Social network analysis will be used to capture relational data from which we will be able to construct sociograms from the respondent’s perspective. Interview data will be analysed both in relation to emergent themes (deploying a grounded theory approach), and from a cross-disciplinary perspective. This mixed method analysis will allow for comparisons across quantitative and qualitative data, for consistency and differences, and will enhance the robustness of data interpretation and conclusions drawn, as multiple data sources are triangulated.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval was granted by the University of Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee and the Family Planning New South Wales Ethics Committee. The study will provide comprehensive, prospective information on the social and sexual development of adolescents in the age of social media and findings will be disseminated through conference presentations and peer-reviewed publications.

Keywords: sexual agency, social media, adolescent relationships, social networks

Strengths and limitations of this study.

An interdisciplinary approach generates a more complete understanding of the nature of complex issues like adolescent social networks and sexual agency.

The development and validation of a novel scale to measure sexual agency in adolescents.

The repeated collection of multiple data types over an 18-month time period during a key developmental phase of adolescence.

However, a longer longitudinal study would provide more in-depth information about this important developmental phase.

Introduction

Healthy sexual development in adolescents is influenced by a range of factors, including parents, schools, peers and the media.1–5 Media, and now social media, have a significant reach in adolescents’ lives. Smartphones and easy access to the Internet make digital communication a part of daily life in many countries.6–12 Studies from the USA, the UK and Australia show that up to 97% of young people are active on some form of social media, many across several social media sites.6 9 13 More than a third report using their main social networking sites several times a day.13 A 2013 survey found almost all the Australian young people surveyed had used a social networking site (97% of those aged 14–15 years, 99% of those aged 16–17 years), 62% accessing social media daily.14

Online cultures offer young people opportunities for learning, play, self-expression and the development of resilience.15 16 We do not yet know what role these media play in sexual development. However, a recent review addressing young people’s online behaviours and sexual risks stated that adolescents who encounter one type of risk tend to encounter others, and they occur both online and offline. There is also a direct association between online and offline sexual activity in adolescents: higher rates of sexual engagement online are related to higher rates offline and vice versa.17 Consequently, the Social Networks and Agency Project (SNAP) study seeks to better understand the ways that young people understand and express sexual agency in both online and offline contexts rather than to address young people’s online activities in isolation, or to assume causative effects of social media interaction.

The limited research on social media use and sexual development has shown both positive and negative influences. Qualitative research with young people in Australia, the UK and North America suggests that young people use social media to negotiate sexuality and gender identity in complex and diverse ways, from jokes and flirtation, to intimacy or aggression.5 18 19 Particular groups may benefit more from social media than others. For example, among those aged 18–24 years, participants who identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual or other same-sex attraction (LGB) used social network sites (SNS) for identity development and communication more than their heterosexual peers.20 Those who used SNS for LGB identity development demonstrated improved mental health outcomes.

Several studies looking specifically at sexually explicit online content have shown associations (though not causal) between exposure to this content and sexual behaviours. A systematic review of cross-sectional studies found a strong association between self-reported exposure to sexual content in new media and sexual behaviours in young people.21 However, as temporal relationships were not clear, it is plausible to conclude that adolescents who began to have sex were also those most interested in sexual content in the media, rather than exposure to sexual content in the media accelerating the adolescents' initiation of sexual activity.

As a result of adolescents expressing themselves online, they may find themselves engaging in what might be termed online risk-taking behaviour. Adolescents have noted experiencing social pressure regarding sexual activity in Internet chat rooms.2 22Pujazon-Zazik and Park found that up to 5% of the users aged 14–17 years had revealing photographs of themselves in swimsuits or their underwear on their profile page.22 Another study identified that 24% of adolescents referenced sexual behaviour; with girls being more likely to do so.23 This could suggest that social media affect girls’ confidence, or sexual agency, in different ways than it does for boys. It should also be noted, however, that broader social and cultural norms relating to appropriate gendered bodily comportment and display may influence individual young people’s subjective experience of ‘body confidence’ in a range of settings and contexts beyond social media.24 Further, Gill and Orgad25 suggest that the notion of ‘confidence’ itself is implicitly gendered within contemporary popular media and academic discourse.25 That is, the capacity to express or deploy ‘confidence’ is primarily measured in relation to women’s deficits in relation to an (ill-defined) masculine ‘norm’, while men’s ‘confidence’ or ‘agency’ is rarely addressed in and of itself. Thus, more investigation—and critical reflection—needs to occur before a hypothesis can be formed.

This study will examine the impact of social networks, both on and offline, on the development of healthy relationships and sexual agency. Sexual agency is the ability to communicate and negotiate about one’s sexuality, while having empathy for a partner’s wants and needs. To have sexual agency means making informed and ethical choices for themselves and accepting the responsibility of those choices. Sexual behaviour is not necessarily related to sexual agency: someone can be having sex and not have high agency within these interactions; conversely, someone can have never had sex and have very high agency (Development and Validity Testing of a Scale to Measure Sexual Agency, currently in preparation for submission)

The focus of this study on sexual agency is a sexual outcome that we want to promote, rather than prevent (such as sexually transmitted infections or unintended pregnancies). Considering positive sexuality outcomes is important: we know that women who receive sex-negative messages engage in more high-risk sexual behaviours than women who receive sex-positive and instructional messages from their parents.26 Similarly, adolescents who express more sex-positive attitudes have been found to be more responsible users of contraception.27 Additionally, girls whose mothers candidly discussed sexual desire and pleasure with them reported experiencing a higher degree of agency and pleasure during their first sexual experience.28

We see two key aspects of social media that lend us to hypothesise that they may support the development of sexual agency. First, online social media provide adolescents with additional opportunities for peer (and non-peer) interaction: Adolescents place high value on their social interactions; the expansion and elaboration of adolescents’ social lives is an essential element of their development. This is critical for their ability to form healthy relationships into the future and is a goal of adolescence.3 Social media are individualised and interactive, such that a person can immediately express him or herself, including expression and engagement of a sexual nature. Additionally, the control of authorities (eg, schools, parents) in relation to social media is much lower than for other social interactions. Social media give adolescents freedoms that they do not have in everyday life, including in the adult-supervised home and school environments where they spend the majority of their time.29 Up to 50% of adolescents feel more comfortable expressing themselves online rather than in face-to-face communication.30

This study takes an interdisciplinary approach; combining research design and theory from the disciplines of social research, public health, clinical practice, media and cultural studies and social network modelling. It uses mixed methods to provide comprehensive, prospective information on the social development of early adolescents.

Aim

To explore the nature and development of sexual agency in adolescents, and to determine if and how online and offline social networks affect the development of sexual agency.

Methods and analysis

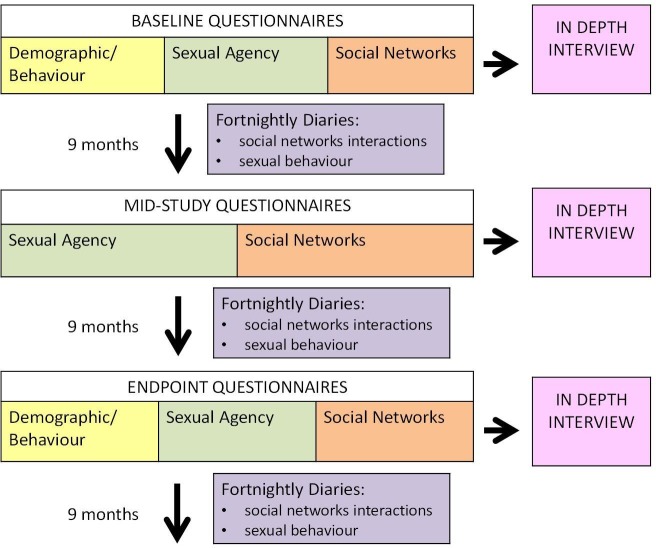

‘Online and offline social networks and the development of sexual agency - The SNAP (Social Networks and Agency Project) study’ is a mixed method prospective observational study that utilises a range of data collection methods (figure 1). The study will run between August 2015 and December 2018. Participants will be followed for 18 months. Enrolment into the study is now complete: recruitment took place between February 2016 and February 2017; thus final follow-up is expected to be completed by September 2018.

Figure 1.

Study design and data collection.

Patient and public involvement

The development and design of the study were informed by adolescent’s experiences and preferences. Young people were involved in the piloting and formalising of the study measures.

Participants will be provided with tailored results written in newsletter form as well as copies of formal publications when requested.

Theoretical framework

This study is guided by an interdisciplinary framework of healthy sexual development.1 This framework identifies 15 key domains of understanding healthy sexual development rather than placing and emphasises solely on age of first sex. These domains include, among others; freedom from unwanted activity, an understanding of consent and ethical conduct more generally, an understanding of safety, agency, resilience, open communication, self-acceptance, awareness and acceptance that sex is pleasurable, and competence in mediated sexuality.1 Further, we take an interdisciplinary approach, acknowledging the importance of different research disciplines to more fully understand a complex issue such as sexual agency in adolescence. This approach is reflected in the skills of research team across sexual health, adolescent development, social science, media and communications and social networks. The interdisciplinary approach has informed the mixed methods study design and will inform analysis and interpretation and dissemination of findings.

Participants

Participants aged between 15 and 17 years were eligible and living in New South Wales, Australia, at the time of recruitment and competent to provide informed consent. This age group, which represents the last 3 years of secondary school, is the age at which most young Australians initiate sexual behaviours and relationships.31 Experiences at this life stage are likely to be formative in the development of sexual agency of individuals. A target sample of 100 participants was set with the expectation of retaining a minimum of 50 participants at the end of the study.

Recruitment

Participants were recruited through a range of convenient locations where researchers had established relationships: three Family Planning New South Wales (FPNSW) clinics, social media sites, the 2016 Promoting Adolescent Sexual Health conference, NSW and one independent school. For recruitment through the FPNSW clinics, promotional materials were left at the Ashfield, Penrith and Newcastle FP clinic sites. Social media recruitment was via paid advertisements on Facebook and Instagram, targeting the study age population. One independent (private) Sydney school was approached for permission to recruit participants and study promotional materials were distributed.

Data collection

Questionnaires

Over the course of the study, participants’ complete three online questionnaires; at baseline, mid study and end of study:

Sociodemographic, sexuality, relationships and sexual behaviour

Items adapted from the National Survey of Australian Secondary Students and Sexual Health32:

Gender identity, age, ethnicity.

Self-reported school attendance, academic performance, satisfaction.

Family and household composition.

Parents’ education and employment.

Sexual identity.

Experience of different sexual behaviours, including age of first experiences.

Current relationships.

Attitudes and expectations about sex.

Sexual agency

A sexual agency measure was developed and pilot tested among 31 participants of various age, race, sexual orientation and gender identities (this measure is described in Development and Validity Testing of a Scale to Measure Sexual Agency, currently in preparation for submission). Cognitive interviews were conducted to test readability, clarity, comprehensiveness and validity of item questions. This scale is designed to measure domains of sexual agency including taking pleasure, assertiveness, sexual health communication and awareness, understanding boundaries and empathy and emotions related to feelings of control. While there are not currently any validated measures that specifically look at sexual agency among adolescents, there are several validated measures that have looked at the related concepts of sexual assertiveness, communication, cost and benefit analysis and behaviour. We used The ‘Hulbert Index of Sexual Assertiveness’33 in designing this scale, which can be used for adolescents who both have and have not had sex. A mean total score (out of 100) is calculated from all items.

Social networks

Informed by egocentric social network methodology advocated by Burt34 including in health,35 participants are asked to nominate between 5 and 10 people with whom they interact the most (participants’ network members). Participants are asked to describe their network members’ gender, first name and first initial of surname and occupation. For each network member participants are then asked to describe:

Their relationship with this person (eg, friend, romantic partner).

Level of relationship closeness (Very close/close/ not really close/not close at all).

Most common mode of interaction (eg, face to face, short message service (SMS), social media, video calling).

Frequency of interactions that are face to face (eg, every day, several times a week, once a week, once a month, less than once a month).

What percent of interactions that are not face to face.

What percent of interactions are flirtatious.

To complete the personal social network (ie, the person-to-person relationship), participants are then asked about the closeness of each network member to the other network members.

Interviews

Semistructured interviews are being conducted face-to-face or via Skype with all participants at baseline, mid-point, and at the end of the participant’s involvement in the study. Interviews are conducted by authors LL, SC and KA. Themes and questions used in the second and third interviews will be informed using an iterative process as the study progresses. This process will involve an initial examination of interview data from a purposively selected sample of participants. Investigators will discuss key themes emerging from the data and gaps in what information the data provided before finalising the semi-structured interview guide for the subsequent interviews. Examples of topics and questions included in interviews are as follows:

Baseline interview

Social media use. What platforms do you use? How do you use them?

Sharing information online. What do you share online? How do you decide what to share and who to share with?

Sexual interactions online. What do you think about online sexual communication, sharing sexual texts or images, learning about sex online?

Romantic relationships. Have you met someone online? How do online and offline romantic relationships differ? How do you interact online with someone you are interested in? How does flirting work online?

Mid-point interview

Sexual health and information. Where do you get information about sexual health? How do people know they are ready for sex? How do they negotiate the kind of sexual activity they might want? What is your definition of safe sex?

Sexual relationships. What is an ideal sexual relationship? Do social media influence how you form ideas of what a relationship should be?

Flirting online. What is the intention behind flirting online? What is your experience of using dating apps? Do you think it’s ok to flirt with someone other than your partner?

Final interview

Sexual agency. What does sexual agency mean to you? Is it a useful concept? How has being in the study affected your views on sex and your sexual agency?

Online and offline relationships. Do you think that it is useful to distinguish between online and offline communication? How have your relationships changed over the past 18 months? If you could tell your parents or teachers anything about sexual agency or how young people communicate what would you tell them?

Diaries

Structured electronic 2-weekly diaries capture participants’ social networks interactions and sexual behaviour over the preceding 2 weeks, for the full 18 months of follow-up. Every 2 weeks, participants receive an email with a link to a secure online data collection site hosted by University of Sydney (Redcap), followed up with two reminder SMSs, if the diary is not completed.

Diary questions about social networks interactions ask participants: to nominate five people (network members) they interacted with most in the past 2 weeks. They are asked what percentage of these interactions with each contact was face-to-face versus non-face-to-face and the percentage of interactions with each network member was flirtatious. Diary questions about sexual behaviour include: number of sexual partners, whether casual or regular partner (including whether they are boyfriend/girlfriend, friend with benefits, hook-up or other), gender of partner, frequency of sex with the partner, and condom use with the partner. For sexually active participants, they are asked about their most recent sexual activity: who initiated the sexual activity, their sexual desire and that of their partners, their enjoyment, what sexual activities were engaged in, use of condoms, whether sex was spontaneous or planned, whether pressure was involved, and who was more in control of the sexual activity. These items were derived from a validated scale to measure online risks developed by Vannier and O’Sullivan.36

Retention

In order to keep adolescents involved in the study over time, they will receive incentives for their participation. Adolescents will receive a $20 gift-card after completing each baseline, mid-study and end of study interview and questionnaire set. Furthermore, participants’ will receive a $20 gift card after completion of every five fortnightly diaries they complete. This incentive structure was developed to provide regular rewards in an effort to keep participants engaged throughout the study. The study coordinator will stay in close contact with the participants, via SMS or email to give them regular study updates or reminders and participants will have access to the research coordinator to ask questions at any time.

Analysis

This is an exploratory study rather than hypothesis driven research. The qualitative interview data will be used to complement findings from the quantitative data (survey, social network and diary data) with the overall aim of developing an explanatory framework of social media influence on the development of sexual agency. Informed by this framework, the impact of social media on the development of sexual agency in adolescence will be evaluated in a longitudinal analysis.

Questionnaires: data on sexual agency and sexual behaviour are collected at three key time points across the 18 months of follow-up.

Examples of research questions to be explored using questionnaire data include:

Does sexual agency change over mid-late adolescence (15–19 years)?

What factors are associated with higher or lower levels of sexual agency?

What factors are associated with changing sexual agency?

Is sexual agency associated with experiences of sexual behaviour?

Interviews: All qualitative data will be digitally recorded, transcribed and thematically analysed. Initial interviews will be read and early themes, impressions, and patterns noted. As new data are gathered, analysis will continue to test the early set of concepts, patterns and relationships. This process will continue until a coherent and robust framework takes shape.

Interview data will be analysed both in relation to emergent themes (deploying a grounded theory approach),37 and in relation to themes emerging from a review of cross-disciplinary literature that addresses the intersection of young people’s sexual cultures, their relationships with friends and families, their social media use and their sexual health information seeking practices.17–20 38 This process aims to map the multiple ways that young people’s social media use might be supportive, undermining or irrelevant to the development of sexual agency, and to better understand the roles that online and offline social relationships (both sexual and non-sexual) might play in supporting sexual health, and social and emotional well-being more broadly.4

Social Network surveys and analysis: At the time of enrolment, mid-way into the study and at the end of the study, we will collect data about the respondent’s friends and the relationships between friends to elicit the personal social network of the respondent.

Examples of research questions explored here include:

What patterns of interactions are observable within the personal network at the tie level, individual level and network level?

Is there an association between network properties and demographic attributes of adolescents?

Is there an inherent relationship between network properties and sexual agency during this key developmental stage? If so, which network properties are most conducive to sexual agency?

To what extent is online social media manifested in the social networks of adolescents and in the context of sexual agency development?

In terms of association with development of sexual agency at the:

Network level: Adolescents who have high personal network density, and particularly those with high centralization within their personal network would experience a high degree of sexual agency development. This is primarily due to the degree of homophily (where similar friends share the same interest)39 and the fact that those individuals who have a high concentration of interactions around them would experience higher degree of development of sexual agency or otherwise. In short, we predict a significant association between density, centralization and sexual agency. The same network variables are hypothesised to associate significantly with social media use in a positive direction.

Actor level: We hypothesise that adolescents who have a high degree of centrality (ie, many others interacting with them), and those who play a closeness and brokerage role (ie, very central within the personal network and can reach many others within their personal networks)40 would have a significant association with development of sexual agency. This is also hypothesised for social media use in a positive direction.

Tie strength: As per the theory of the strength of weak ties,41 weak ties allow for access to novel information, which would otherwise not be accessible due to redundancy of information from the cohesive group. Strong ties, on the other hand, are useful for complex problem solving, and conducive to trust. Given that adolescents tend to socialise with those they are comfortable with, we hypothesise strong ties, rather than weak ties would have a significant association with the development of sexual agency and the direction of the association could be either way.

As the social network data collected will be from the respondent’s perspective, the egocentric network approach will be used,42 where all interactions between the respondent and the friends as well as interactions between friends themselves will be recalled from the respondent’s perspective. The name generator question that will be used is:

’Looking back over the last 6 months, please list up to 10 people (eg, friends, boyfriend/girlfriend, family member, etc.) you interacted with the most.’

Attribute data about the friends (eg, gender, occupation, medium of communication, flirt with or not, etc.) and data about the tie (eg, frequency of interaction and closeness) will also be collected. To complete the personal network, the respondent is also asked to recall which of the friends interacted with the other, and in doing so, the closeness of the relationship is also elicited.

Analysis: With each egocentric network obtained, we will analyse their network to understand the following key properties (the definitions and mathematical expressions of which are available in Wasserman et al 43:

Ego-density: this is the density of the network that excludes the respondent (in other words, the density of the interactions of the friends only).

Betweenness centrality: the extent to which the respondent lies in the shortest path of all others in the network. this explains brokerage capacity—a central role that yields information benefits such as novel information and creativity.

Degree centrality: simply, the number of ties the respondent has to her friends. Degree centrality explains information flow and influence (eg, number of followers, etc).

Efficiency: a measure of brokerage that explains whether an individual optimises the brokerage capacity in networks by bridging groups that are otherwise not connected.

Constraint: a measure of the extent to which a network is so tightly connected that information becomes redundant quickly.

Tie strength: a measure of how frequent and how close one is to all others within the network.

Aside from the visual network analysis that allows us to explore patterns in relationships, we will also be using the above network properties as an attribute of the individual which can then be statistically tested on a dependent variable. For instance, we can regress (using multiple regression) or correlate (eg, Pearson’s correlation) network variables against other variables such as sexual agency.

When grouped into high-low groups (eg, groups with high efficiency or low efficiency), independent sample t-tests can then be conducted to determine whether there is an association between groups. For instance, we will be able to understand whether female or male adolescents have networks with higher or lower network efficiency. As a further example, the same test can be applied for adolescents who enjoy school or do not.

Diaries—sexual behaviour: We will conduct longitudinal analyses to describe changes in sexual behaviour and experiences over time, sexual agency, social media use, and social network patterns. Analysis will use a multi-level approach, to account for within person and between person changes.

Examples of research questions explored using diary—sexual behaviour data include:

What specific patterns of sexual experience, sexual agency, social media use and social networks are common to adolescents during this key developmental stage?

What event-specific and individual characteristics are associated with participants’ enjoyment/satisfaction of a sexual experience?

What event-specific and individual characteristics are associated with condom use during a sexual experience?

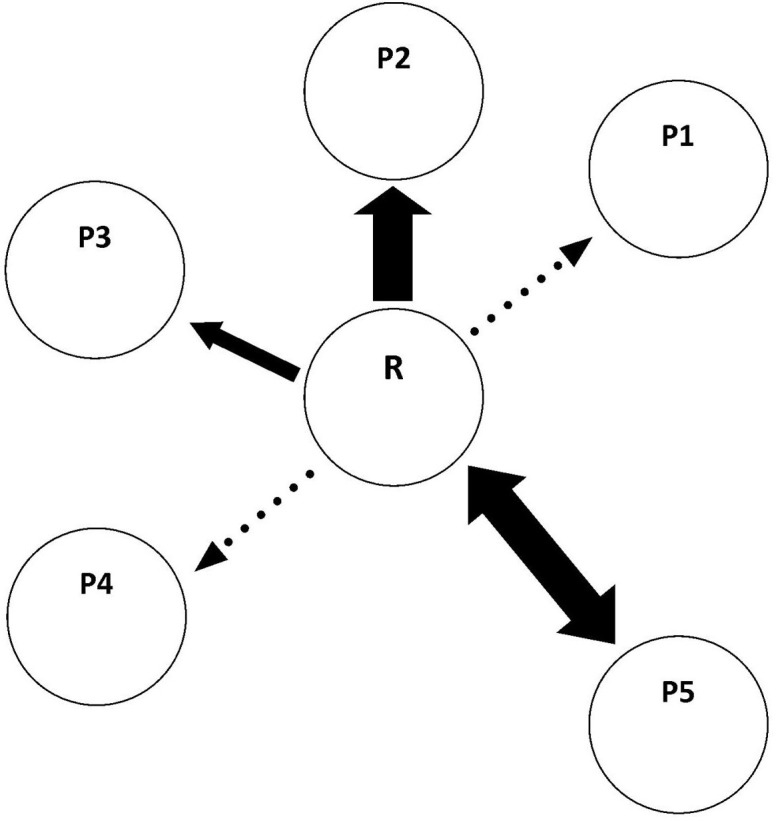

Diaries—social networks: The diaries capture relational data that shows social media usage and interactions between the respondent and his or her friends (see figure 2). From this relational data, we will be able to construct the sociogram from the respondent’s perspective. We are then able to calculate degree centrality, which is simply the sum of incoming or outgoing ties. Degree centrality has been associated with popularity in terms of who interacts with whom or who follows whom.40 The other important relational notion is the strength of these ties – that is, how often do the interactions take place.44 This can be summed up and normalised to a scale of 1 to 5, where five means very often (ie, a strong tie) and one means seldom (ie, a weak tie).41 An average value for tie strength can then be computed for the respondent. These values can then be used in independent sample t-tests to test if there is a statistically significant difference in network properties (of tie strength and degree centrality) between groups demonstrating sexual agency and groups otherwise.

Figure 2.

Example of social networks information collected via social network diaries. Black arrow, social media engagement and sexual activity engagement; dotted arrow, social media interaction and no sexual activity engagement; P, partner/friend; R, respondent; thickness of arrow, tie strength.

Mixed methods analyses

We will use qualitative data from each participant and undertake comparisons across questionnaire and diary data, for consistency and differences. The qualitative data will also be explored in order to explain and understand better specific findings arising from the quantitative data. This will enhance the robustness of data interpretation and conclusions drawn, as multiple data sources are triangulated.

Ethics and dissemination

The study team closely considered the question of how to assess the competence or capacity of prospective participants aged less than 18 years to provide informed consent.

Once an adolescent expressed a desire to participate, we asked them if they felt comfortable with us obtaining parental consent. If they did not feel comfortable with obtaining parental consent, we undertook a competency assessment to ensure they had the ability to provide informed consent themselves.

Study questionnaires and interview guides were carefully designed and written to ask questions about participants’ everyday experiences and not about distressing events specifically. Prior to the in-depth interview participants are reminded that the interviewer is obligated to notify the appropriate authorities if disclosure of sexual abuse, assault, self-harm or of harming others occurs. In addition, rather than treating informed consent as a ‘one-off’ process, our approach with this target group is to engage in a process of ongoing dialogue around consent from first contact to completion of the study. This is based on best practice descriptions in the literature,45–48 advice from professionals in contact with adolescents, as well as the experience of members of the research team in the conduct of study of those under the age of 18.

In the unlikely event of disclosures of unwanted sex or sexual assault, a member of the study team will assist the participant in negotiating any situations of difficulty and if deemed appropriate, to liaise with their general practitioner, school counsellor, and Family Planning counselling. All participants regardless of disclosure are provided with information of national counselling services.

Adolescents receive one $20 gift card after each of the three in-depth interviews. For every five fortnightly diaries submitted they receive another $20 gift card of their choice for a possible study total of $220 AUD. To minimise the potential for coercion to participate in the study, we did not advertise the monetary values of gifts on any recruitment flyers. However, to ensure fully informed consent, the study Participation Information Statement included the value of any reimbursements offered and how they are calculated.

It is envisioned that the overall results of the research study will lead to journal publications. Results could also be presented in the form of conference presentations. Young people will be asked for their input into the writing of a plain language report. Researchers will seek input and engagement with health and educational policy sector stakeholders around the findings and their translation.

Discussion

The study will provide comprehensive, prospective information on the social and sexual development of adolescents. The longitudinal mixed methods study will capture the development of sexual agency and behaviours, the online and offline interactions adolescents engage in, and how these are linked. It will also assess adolescents’ perceptions of these on their sexual development. These findings will allow us to understand the diversity of adolescent socialisation in the age of social media.

Strengths of the SNAP study include the interdisciplinary approach, which we believe will provide a more complete understanding of adolescent social interactions and sexual agency, the repeated collection of multiple data types over an 18 month time period, the richness of both the qualitative and quantitative data, and the development and validation of a novel scale to measure sexual agency. Weaknesses of the study include the non-random sampling approach which necessarily results in a sample that is not representative of all Australian adolescents, and the small sample size, which limits the ability for definitive quantitative inferences.

SNAP’s mixed-methods approach to the interplay of young people’s online and offline relationships is novel in that it does not presume a causative relationship between online and offline sexual expression and/or romantic relationships. The study aims to identify the ways that young people’s social media use intersects with other forms of information seeking and interpersonal communication, in order to better understand the complex contexts and settings in which young people develop a sense of self-understanding and self-efficacy in relation to sex and sexuality. The results will inform educational and school policy, and be of use in a variety of settings including sexual education. Providing feedback, training, and support to schools as an outcome of this research will be a significant benefit. The results will inform health promotion activities and the development of resources for adolescents and their parents and support the provision of youth-friendly adolescent clinical services. It will also potentially inform policy on social media use and healthy development in adolescence more generally.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: SC led the team that conceived of the presented idea. SC, MSCL, KA, KSKC and SRS designed the study; LL, DB and MK contributed in interpreting the design into practicality and implementing the study. All authors discussed the paper and contributed to the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the Australian Research Council Discovery Project (DP150104066).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval was granted by both the University of Sydney Ethics Committee (Project number 2015/489) and the NSW Family Planning Ethics Committee (Project number R2015-10).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. McKee A, Albury K, Dunne M, et al. Healthy sexual development: a multidisciplinary framework for research. International Journal of Sexual Health 2010;22:14–19. 10.1080/19317610903393043 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Widman L, Choukas-Bradley S, Helms SW, et al. Adolescent susceptibility to peer influence in sexual situations. J Adolesc Health 2016;58:323–9. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.10.253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Collins WA, Welsh DP, Furman W. Adolescent romantic relationships. Annu Rev Psychol 2009;60:631–52. 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Byron P. Friendship, sexual intimacy and young people’s negotiations of sexual health. Cult Health Sex 2017;19:486–500. 10.1080/13691058.2016.1239133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Albury K. Young people, media and sexual learning: rethinking representation. Sex Educ 2013;13:S32–S44. 10.1080/14681811.2013.767194 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Australian Communications and Media Authority. ’Trends in media use by children and young people: insights from the kaiser family foundation’s generation m2 2009 (usa), and results from the acma’s media and communications in australian families 2007'. Commonwealth of Australia 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Green L, Brady D, Ólafsson K, et al. Risks and Safety for Australian Children on the Internet: Full Findings from the AU Kids Online Survey of 9-16-year-olds and their parents. 4: ARC Centre of Excellence for Creative Industries and Innovation, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Livingstone S, Bober M. "UK children go online: Final report of key project findings.", 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Livingstone S, Haddon L, Görzig A. Ólafsson K, Risks and safety on the internet: the UK report. London: LSE, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 10. O’Keeffe GS, Clarke-Pearson K. Council on Communications and Media. The impact of social media on children, adolescents, and families. Pediatrics 2011;127:800–4. 10.1542/peds.2011-0054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Steinberg L. Cognitive and affective development in adolescence. Trends Cogn Sci 2005;9:69–74. 10.1016/j.tics.2004.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wolak J, Mitchell K, Finkelhor D. Unwanted and wanted exposure to online pornography in a national sample of youth Internet users. Pediatrics 2007;119:247–57. 10.1542/peds.2006-1891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Common Sense Media. Social media, social life: how teens view their digital lives, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Australian Communications and Media Authority. Like, post, share: Young Australian’s experience of social media. Commonwealth of Australia 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Third A, Bellerose D, Dawkins U, et al. Children’s Rights in the Digital Age: A Download from Children Around the World. Melbourne: Young and Well Cooperative Research Centre, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Livingstone S, Helsper E. Balancing opportunities and risks in teenagers’ use of the internet: the role of online skills and internet self-efficacy. New Media Soc 2010;12:309–29. 10.1177/1461444809342697 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Livingstone S, Mason J. Sexual Rights and Sexual Risks among Online Youth. London: London School of Economics/ ENACSO, the European NGO Alliance for Child Safety Online, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ringrose J, Barajas KE. Gendered risks and opportunities? Exploring teen girls' digitized sexual identities in postfeminist media contexts. International Journal of Media & Cultural Politics 2011;7:121–38. 10.1386/macp.7.2.121_1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Boyd D. It’s Complicated: the social lives of networked teens Yale: Yale University Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ceglarek PJD, Ward LM. A tool for help or harm? How associations between social networking use, social support, and mental health differ for sexual minority and heterosexual youth. Comput Human Behav 2016;65:201–9. 10.1016/j.chb.2016.07.051 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Smith LW, Liu B, Degenhardt L, et al. Is sexual content in new media linked to sexual risk behaviour in young people? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex Health 2016;13:501 10.1071/SH16037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pujazon-Zazik M, Park MJ. To tweet, or not to tweet: gender differences and potential positive and negative health outcomes of adolescents' social internet use. Am J Mens Health 2010;4:77–85. 10.1177/1557988309360819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Moreno MA, Parks M, Richardson LP. What are adolescents showing the world about their health risk behaviors on myspace? MedGenMed 2007;9:9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Albury K. Selfies, sexts and sneaky hats: young people’s understandings of gendered practices of self-representation. International Journal of Communication 2015;9:1734–45. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gill R, Orgad S. The confidence cult(ure). Australian Feminist Studies 2015;30:324–44. 10.1080/08164649.2016.1148001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ward LM, Wyatt GE. The effects of childhood sexual messages on african-american and white women’s adolescent sexual behavior. Psychol Women Q 1994;18:183–201. 10.1111/j.1471-6402.1994.tb00450.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fisher W, Byrne D, White L. Emotional Barriers To Contraception : Byrne D, Fisher W, Adolescents, Sex, And Contraception. In: Fisher DBW, editor. Adolescents, Sex, And Contraception. Hillside NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wyatt GE, Lyons-Rowe S. African American women’s sexual satisfaction as a dimension of their sex roles. Sex Roles 1990;22:509–24. 10.1007/BF00288167 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Boyd D. Why youth♥ social network sites: The role of networked publics in teenage social life, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Livingstone S, Kirwil L, Ponte C, et al. In their own words: what bothers children online? with the EU Kids Online Network. London, UK: London School of Economics and Political Science, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Smith AM, Agius P, Mitchell A, et al. Secondary Students and Sexual Health 2008. 70 Melbourne: Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health & Society, La Trobe University, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mitchell A, Patrick K, Heywood A, et al. 5th National Survey of Australian Secondary Students and Sexual Health 2013. Melbourne: Australian Research Centre for Sex Health and Society, Latrobe University, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hurlbert DF. The role of assertiveness in female sexuality: a comparative study between sexually assertive and sexually nonassertive women. J Sex Marital Ther 1991;17:183–90. 10.1080/00926239108404342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Burt RS. Network items and the general social survey. Soc Networks 1984;6:293–339. 10.1016/0378-8733(84)90007-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. In: Chung KK, Hossain L, Davis J, eds Exploring sociocentric and egocentric approaches for social network analysis. Proceedings of the 2nd international conference on knowledge management in Asia Pacific, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Vannier SA, O’Sullivan LF. Sex without desire: characteristics of occasions of sexual compliance in young adults' committed relationships. J Sex Res 2010;47:429–39. 10.1080/00224490903132051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative research. London: SagePublications Ltd, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Baym NK. Personal connections in the digital age. 2 edn Indianapolis: John Wiley and Sons, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 39. McPherson JM, Smith-Lovin L. Homophily in voluntary organizations: status distance and the composition of face-to-face groups. Am Sociol Rev 1987;52:370–9. 10.2307/2095356 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Freeman LC. Centrality in social networks conceptual clarification. Soc Networks 1978;1:215–39. 10.1016/0378-8733(78)90021-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Granovetter MS. The strength of weak ties. Am J Sociol 1973;78:1360–80. 10.1086/225469 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42. International Conference on Knowledge Management Asia Pacific. : Chung KSK, Hossain L, Davis J, Exploring Sociocentric and Egocentric Approaches for Social Network Analysis. New Zealand: Victoria University Wellington, 2005:27–9. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wasserman S, Faust K, Granovetter M, Social Network Analysis: Methods and Applications. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Marsden PV, Campbell KE. Measuring tie strength. Social Forces 1984;63:482–501. 10.1093/sf/63.2.482 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Alderson P, Morrow V. Ethics, social research and consulting with children and young people, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Burke TM, Abramovitch R, Zlotkin S. Children’s understanding of the risks and benefits associated with research. J Med Ethics 2005;31:715–20. 10.1136/jme.2003.003228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hill M. Ethical considerations in researching children’s experiences. Researching children’s experience 2005:61–86. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sanci LA, Sawyer SM, Kang MS, et al. Confidential health care for adolescents: reconciling clinical evidence with family values. Med J Aust 2005;183:410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.