Abstract

Objective

Hospitals in the UK are under increasing clinical and financial pressures. Following introduction of childhood rotavirus vaccination in the UK in 2013, rotavirus gastroenteritis (RVGE) hospitalisations reduced significantly. We evaluated changes in ‘hospital pressures’ (demand on healthcare resources and staff) following rotavirus vaccine introduction in a paediatric setting in the UK.

Design

Retrospective hospital database analysis between July 2007 and June 2015.

Setting

A large paediatric hospital providing primary, secondary and tertiary care in Merseyside, UK.

Participants

Hospital admissions aged <15 years. Outcomes were calculated for four different patient groups identified through diagnosis coding (International Classification of Disease, 10th edition) and/or laboratory confirmation: all admissions; any infection, acute gastroenteritis and RVGE.

Methods

Hospital pressures were compared before and after rotavirus vaccine introduction: these included bed occupancy, hospital-acquired infection rate, unplanned readmission rate and outlier rate (medical patients admitted to surgical wards due to lack of medical beds). Interrupted time-series analysis was used to evaluate changes in bed occupancy.

Results

There were 116 871 admissions during the study period. Lower bed occupancy in the rotavirus season in the postvaccination period was observed for RVGE (−89%, 95% CI 73% to 95%), acute gastroenteritis (−63%, 95% CI 39% to 78%) and any infection (−23%, 95% CI 15% to 31%). No significant overall reduction in bed occupancy was observed (−4%, 95% CI −1% to 9%). No changes were observed for the other outcomes.

Conclusions

Rotavirus vaccine introduction was not associated with reduced hospital pressures. A reduction in RVGE hospitalisation without change in overall bed occupancy suggests that beds available were used for a different patient population, possibly reflecting a previously unmet need.

Trials registration number

Keywords: nosocomial infections, hospital, epidemiology, rotavirus, quality in health care

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study used 8 years of retrospective routinely collected data from a large paediatric hospital in the UK.

This is the first study to examine the effects of a vaccine on wider measures of hospital pressures in the UK.

Our analysis highlights the importance of the presentation of data from the full study period in a time series analysis, rather than restricting the results to a ‘before-after’ comparison.

Our analysis was complicated by inevitable changes in hospital practices over the 8-year study period, in particular changes in patient flow, laboratory procedures, infection control and clinical coding.

Introduction

In the context of increasing patient need and constrained resources, the UK’s National Health Service (NHS) faces growing clinical and financial pressures. Currently, the NHS is failing to meet targets for urgent, emergency and planned care.1 2 Hospital admission rates have been increasing for the past decade; if the increases continue at the current rate an extra 22 hospitals with 800 beds each will be required by 2022.3 Although highest for the elderly, increases in admission rates are occurring across all age groups.3 In children aged 0–14 years, the number of hospital admission episodes increased from 1.7 to 2.0 million between 2004–05 and 2014–154 and emergency department (ED) attendances have risen by approximately 300 000 between 2011–12 and 2014–15,5 leaving paediatric services with increased demand but a short fall of medical staffing.6

While the problems the NHS faces are complex, there are ongoing disease prevention mechanisms which can help alleviate some of the burden. Vaccines, for example, are the most effective defence against infectious diseases.7 For highly efficacious vaccines targeting childhood diseases with a large hospitalisation burden, it is possible that the reduction in beds occupied for infections caused by the vaccine target pathogen reduces hospital pressures, and potentially nosocomial infections.8 9

Prior to vaccine introduction in the UK, rotavirus gastroenteritis (RVGE) was a major cause of hospital admission in young children during the winter/spring months. It was estimated that in children <5 years of age, 20% of ED attendances and 45% of hospitalisations for acute gastroenteritis (AGE) were due to rotavirus infections.10 The UK introduced the monovalent two-dose rotavirus vaccination (Rotarix, GSK) into the routine childhood immunisation schedule in July 2013. Rotavirus vaccine uptake increased rapidly to over 90% for one dose11 and early vaccine impact studies suggest a significantly reduced incidence of RVGE hospitalisations in children.7 12 13 The aim of this study was to assess hospital pressures at a large UK NHS paediatric hospital before rotavirus vaccine and following rotavirus vaccine introduction using routinely collected data. As there are no direct measures of hospital clinical pressures (on healthcare resources and staff), evidenced proxy indicators were used: bed occupancy, hospital-acquired infection rate, unplanned readmission rate and rate of outliers (medical patients admitted to surgical wards).

Methods

Setting

Alder Hey Children’s NHS foundation Trust (Alder Hey) is located in Liverpool, UK and is one of the largest paediatric hospitals in Europe, with a catchment population of over 7.1 million. Alder Hey provides primary, secondary and tertiary care facilities for >200 000 children each year and has approximately 240 inpatient beds; this study used data prior to the opening of a new hospital premises in October 2016. General medicine, general surgery and a range of specialist services are provided. There is also a large ED. Patients with a suspected or confirmed RVGE are admitted to a room within the cubicle areas of one of the general medical wards. If no beds are available in the general medical wards, cubicle areas in specialised medical wards or surgical wards are used.

Data sources

Retrospective hospital database analysis (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT03271593) was conducted at Alder Hey. Anonymised bed admission and laboratory data were extracted by the hospital informatics department from routine patient databases. Patient data were extracted for the period July 2000–June 2015; analysis was restricted to the period July 2007–June 2015 since changes were made to clinical coding in 2006, and bed availability data were only available from February 2006 onwards.

Study population and definitions

We included all inpatients aged 0–14 years admitted between 1 July 2007 and 30 June 2015, who attended at least one ward other than the ED. Excluded from analysis were any patients aged 15 years or older at time of admission, day patients and those who were admitted and discharged from the ED or observation unit without attending another ward.

Outcomes were calculated for four different patient groups identified through International Classification of Disease, 10th edition (ICD-10) hospital discharge diagnosis codes:

All admissions.

Any infection: admissions coded as any infection (ICD-10 A00-B99 and J09-J22 in any diagnostic code) or as non-infectious gastroenteritis (K52.9).14

AGE: admissions coded as AGE (ICD-10 A00-A09 in any diagnostic code) or as non-infectious gastroenteritis (K52.9).14

RVGE: admissions coded as RVGE (ICD-10 A08.0 in any diagnostic code) and/or laboratory-confirmed as rotavirus.14 Laboratory confirmation for RVGE was defined as rotavirus antigen detected by either immunochromatographic test or by enzyme immunoassay in a faecal specimen of a child with AGE. A distinction was made between community-acquired (CA) and hospital-acquired (HA) RVGE: HA RVGE was defined as any patient with a positive test for rotavirus infection with a sample date >2 days after admission and no record of diarrhoea or vomiting on admission.7 Testing for RVGE was done on clinicians’ request. The testing policy for RVGE did not change over the study period.

Diagnosis coding for non-infectious gastroenteritis (ICD-10 K52.9) was included since unspecified gastroenteritis was classified under this code until April 2012.15

The prevaccination period was defined as 1 July 2007–30 June 2013; the postvaccination period was defined as 1 July 2013–30 June 2015. The rotavirus season was defined as 1 January–31 May; the period when laboratory detection rate in the UK is highest.16

Outcomes

The following outcomes were calculated:

Bed occupancy: number of patients allocated a bed on a specific ward divided by number of available beds at that ward at 12:00 noon. Bed occupancy for any infection, AGE and RVGE were determined using the definitions above. For HA RVGE, only bed occupancy on the ward where the patient tested positive for rotavirus was included. For CA RVGE, total hospital stay was attributed to rotavirus. Sensitivity analyses were conducted with bed availability data collected at 09:00 and 17:00 hours.

HA bloodstream infection rate: number of HA bloodstream infections per 1000 admissions with length of stay >2 days. We used indicator organisms to describe HA infection: a HA bloodstream infection was defined as identification of methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus or methicillin-resistant S. aureus or Escherichia coli or Candida species in a blood sample obtained >2 days after admission. HA bloodstream infection rate was used as an outcome measure since, as for other outcome measures such as HA rotavirus, this may be an indicator of how changes in hospital pressures could influence infection control practices and subsequent nosocomial transmission.

Unplanned readmission: number of patients with an emergency readmission within 7 days after discharge per 1000 admissions.8

Outlier rate: number of medical patients admitted to a surgical ward per 1000 admissions. A medical patient was defined as any patient classified under haematology/oncology, general paediatrics, endocrinology, nephrology, rheumatology, respiratory medicine, dermatology or accident and emergency.

Calculations of bed occupancy, HA infection rate and unplanned readmission rate were restricted to nine general medical wards. Several wards opened or closed during the study period. Changes in ward structure were taken into account in the outcomes calculated by including data according to the wards’ opening periods.

Descriptive analysis

Data analyses were performed using R V.3.2.0 (R Core Team, Vienna). The number of admissions for each patient group, length of stay and age of RVGE patients was described prevaccine and postvaccine introduction during the rotavirus season. Differences between continuous variables were tested using Student’s t-test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test if not normally distributed and χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables.

Statistical analysis

To assess any changes in bed occupancy following rotavirus vaccine introduction, interrupted time-series analysis was used as previously described.7 Monthly expected bed occupancy was estimated by fitting a negative binomial regression model to prevaccine monthly bed occupancy data, adjusted for seasonality and secular trends using calendar month and rotavirus year (July to June), respectively. A negative binomial model was chosen to account for overdispersion in the data. This model was used to predict the expected bed occupancy rate in the absence of vaccination, where the postvaccine introduction change is expressed by the difference between the expected and observed bed occupancy. To quantify change in average bed occupancy in the rotavirus season as a result of introduction of the vaccine, a second model included a binary indicator variable for the vaccine period, enabling the computation of risk ratios (RR) and associated 95% CIs. This second model was restricted to the rotavirus season and adjusted for calendar month and rotavirus year. Percentage change in average bed occupancy was calculated as 100(1−RR).

Patient and public involvement statement

This study was conducted using secondary data and there was no new contact with patients throughout the study. No patients were directly involved in designing the research question, conducting the research or interpretation of the research findings. Investigators have presented these findings at national and international events.

Results

In total, there were 116 871 admissions among 68 838 unique patients at any time in the year during the study period from 1 July 2007 to 30 June 2015. Of those admissions, 48 852 occurred during the rotavirus season.

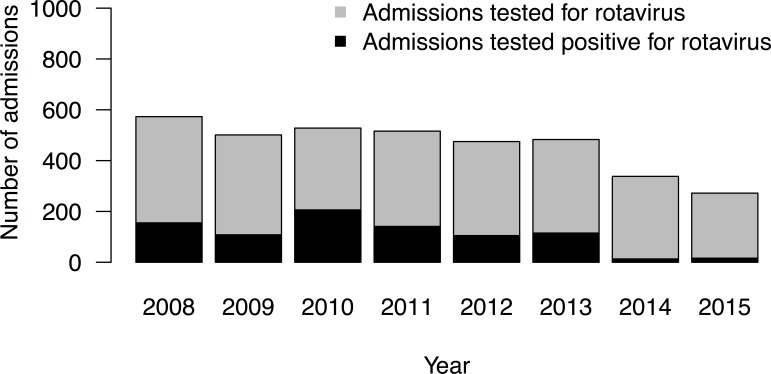

Testing for rotavirus remained stable throughout the prevaccination study period, with a median of 509 (IQR=481–539) admissions tested each rotavirus season, of which a median of 128 (25.2%) were positive (figure 1). In the rotavirus seasons following rotavirus vaccine introduction, the proportion of rotavirus-positive test results among admissions tested dropped to 3.8% (13/338) and 5.9% (16/272) in 2014 and 2015, respectively.

Figure 1.

Number of admissions tested for rotavirus in the rotavirus season in Alder Hey NHS Foundation Trust, July 2007–June 2015. NHS, National Health Service.

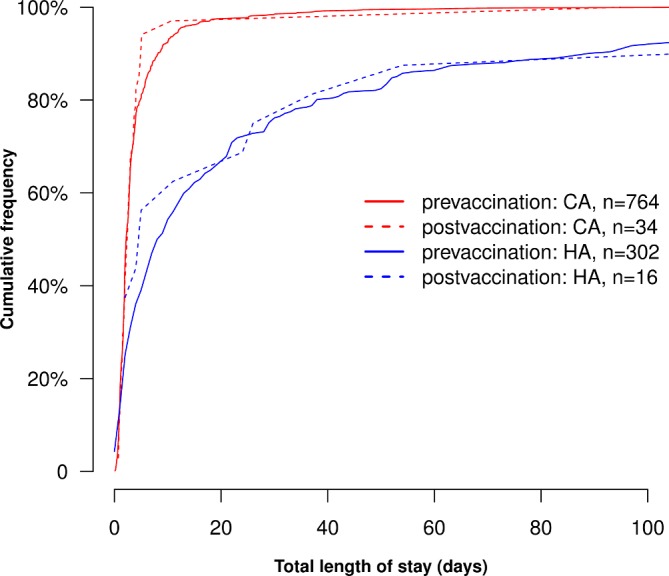

The median age of patients with RVGE was 11 months in the prevaccination period, and 22 months in the postvaccination period (p=0.06). Median length of hospital stay for patients with CA RVGE did not differ between the prevaccination and postvaccination period (2.2 vs 2.4 days, p=0.89). Median length of stay from RVGE diagnosis to discharge for patients with HA RVGE was not significantly different between the prevaccination and postvaccination period (8.5 days prevaccination vs 5.0 days postvaccination, p=0.88) (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Total length of stay for CA and HA RVGE in Alder Hey NHS Foundation Trust. For HA RVGE, length of stay was calculated from date of first positive test. CA, community-acquired; HA, hospital-acquired; RVGE, rotavirus gastroenteritis.

Length of stay for all admissions was highest during the respiratory virus season in November/December and slightly increased from 2007 to 2012 (p<0.001) (online supplementary figure 1). No significant change in length of stay for all admissions was observed for the period 2012 to 2015 (p=0.21).

bmjopen-2018-027739supp001.pdf (570.3KB, pdf)

Bed occupancy

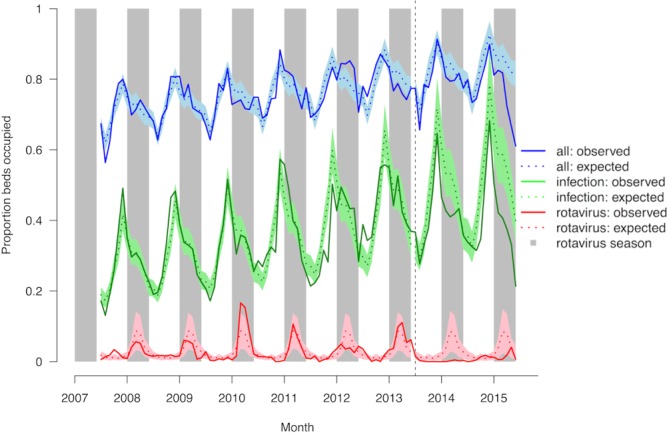

Figure 3 shows the average monthly bed occupancy for general medical wards for all admissions, admissions with a diagnosis of any infection and admissions with a diagnosis of RVGE. Bed occupancy for AGE is shown in online supplementary figure 2. Clear seasonal patterns were observed for total bed occupancy, with highest overall bed occupancy for the respiratory virus season in November/December, and lowest overall bed occupancy in the summer months. A year-on-year increase was observed for overall bed occupancy over the study period (p<0.001), from 79% bed occupancy in December 2007 to 90% in December 2014.

Figure 3.

Observed and expected bed occupancy for any admission, any infection and rotavirus gastroenteritis on general medical wards in Alder Hey NHS Foundation Trust, July 2007–June 2015. The coloured shading represents the 95% CI for the expected incidence. Grey shading represents the rotavirus season (January–May). The vertical hashed line represents the introduction of rotavirus vaccine in the UK in July 2013. NHS, National Health Service.

Bed occupancy for RVGE showed clear seasonal peaks before introduction of the vaccine, with highest occupancy shown for February/March. After introduction of the rotavirus vaccine, bed occupancy for RVGE in the rotavirus season was reduced by 89% (95% CI 73% to 95%) (table 1). Bed occupancy for any infectious disease increased year on year in the prevaccination period, both within and outside the rotavirus season (p<0.001 and p<0.001 respectively), as did bed occupancy for AGE (p<0.001 within, p=0.04 outside rotavirus season). Postintroduction of the vaccine, observed bed occupancy for AGE in the rotavirus season was reduced by 63% (95% CI 39% to 78%) after adjustment for the positive trend in the prevaccination period. Observed bed occupancy for any infection in the rotavirus season was reduced by 23% (95% CI 15% to 31%). No significant reduction was observed when considering observed versus expected bed occupancy for any cause of admission (−4%, 95% CI −1% to 9%). Sensitivity analyses with bed availability data taken at 09:00 and 17:00 hours provided similar results.

Table 1.

Average monthly bed occupancy and decline in bed occupancy comparing the pre-rotavirus vaccination and post-rotavirus vaccination period for any admission, any infection, acute gastroenteritis and rotavirus gastroenteritis on general medical wards in Alder Hey NHS Foundation Trust, July 2007–June 2015

| Variable | Average bed occupancy in rotavirus season (range) | Crude risk ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted risk ratio (95% CI)* | Decline in bed occupancy (95% CI) |

P value | |

| Prevaccination | Postvaccination | |||||

| All | 77% (70%–85%) | 79% (67%–87%) | 1.03 (0.99 to 1.08) | 0.96 (0.91 to 1.01) | 4% (−1% to 9%) | 0.15 |

| Any infection† | 39% (25%–56%) | 42% (33%–51%) | 1.09 (0.95 to 1.25) | 0.77 (0.69 to 0.85) | 23% (15% to 31%) | <0.001 |

| AGE† | 5% (1%–16%) | 3% (1%–8%) | 0.72 (0.45 to 1.13) | 0.37 (0.22 to 0.61) | 63% (39% to 78%) | <0.001 |

| RVGE‡ | 5% (0%–17%) | 1% (0%–4%) | 0.18 (0.09 to 0.35) | 0.11 (0.05 to 0.27) | 89% (73% to 95%) | <0.001 |

*Adjusted for seasonality and secular trend.

†Diagnosis of any infection and AGE by clinical coding only.

‡Diagnosis of RVGE by clinical coding and laboratory results.

AGE, acute gastroenteritis; NHS, National Health Service; RVGE, rotavirus gastroenteritis.

Hospital-acquired bloodstream infection rate

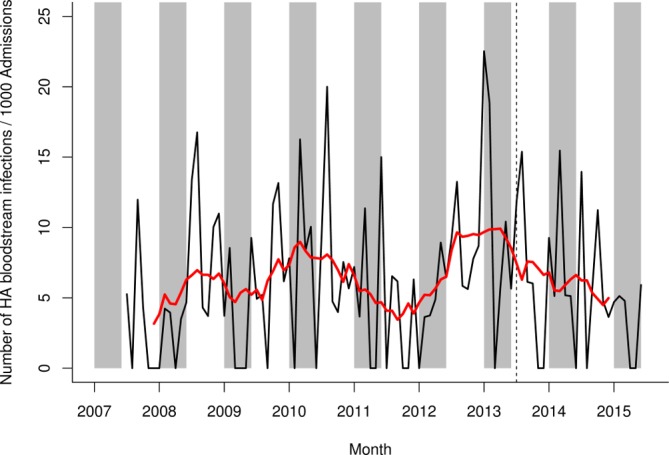

A decrease in HA bloodstream infection was observed in the postvaccination period, although this did not appear different from secular trends in the prevaccination period (figure 4).

Figure 4.

HA bloodstream infection rate on general medical wards in Alder Hey NHS Foundation Trust, July 2007–June 2015. Black line shows raw data, red line shows smoothed data. Grey shading represents the rotavirus season (January–May). The vertical hashed line represents the introduction of rotavirus vaccine in the UK in July 2013. HA, hospital-acquired; NHS, National Health Service.

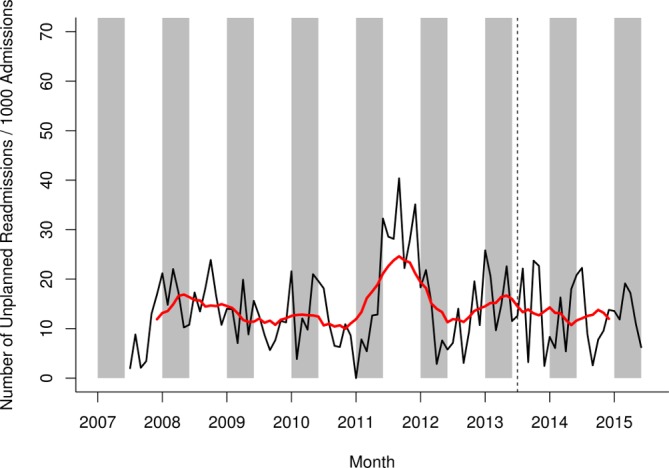

Unplanned readmission rate

No difference was observed between the unplanned readmission rate in the prevaccination period and the postvaccination period (figure 5).

Figure 5.

Unplanned readmission rate for any admission on general medical wards in Alder Hey NHS Foundation Trust, July 2007– June 2015. Raw data in black, smoothed data in red. Grey shading represents the rotavirus season (January–May). The vertical hashed line represents the introduction of rotavirus vaccine in the UK in July 2013. NHS, National Health Service.

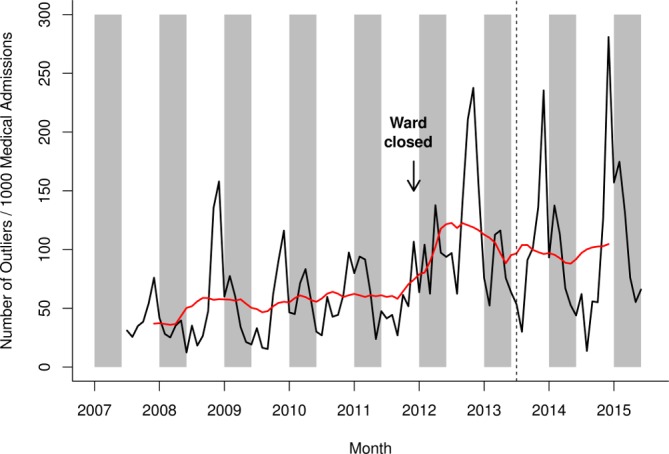

Outlier rate

Clear seasonal patterns were observed for the outlier rate, with the highest peak during the respiratory virus season in November/December, and a secondary peak during the rotavirus season in January–May (figure 6). The outlier rate increased in 2012, and remained high throughout 2013–2015, both within and outside the rotavirus season. The increase in outlier rate is synchronous with the closure of one specific ward, a large general medical ward in November 2011 and the opening of a new medical admission unit (short-stay department prior to discharge or admission to other wards).

Figure 6.

Outlier rate for any admission in Alder Hey NHS Foundation Trust, July 2007–June 2015. Raw data in black, smoothed data in red. Grey shading represents the rotavirus season (January–May). The vertical hashed line represents the introduction of rotavirus vaccine in the UK in July 2013. NHS, National Health Service.

Discussion

This is the first study to examine the effects of national vaccine introduction on wider measures of hospital pressures in the UK. The introduction of rotavirus vaccine has led to a large reduction in RVGE hospitalisation,7 reflected in the reduction in proportion of admissions tested rotavirus-positive and the reduction in bed occupancy due to RVGE and AGE as described here. Lower bed occupancy for RVGE and AGE in the rotavirus season postvaccine introduction was concordant with lower bed occupancy for any infection in the rotavirus season in the postvaccination period. Despite the reduction in RVGE hospitalisation, overall bed occupancy was not reduced. This suggests that a large, busy NHS Trust, such as Alder Hey, operates at full capacity and that the beds that became available by the reduction of RVGE hospitalisations were occupied by a different patient population, probably reflecting a previously unmet need and/or physicians having greater freedom to admit patients if beds have become available. The absence of a reduction in overall bed occupancy could explain why reductions in the other proxy measures (HA-infection rate, unplanned readmission rate, outlier rate) were not observed.

Two other studies have examined hospital pressures since rotavirus vaccination introduction. A study conducted in two Finnish hospitals concluded that bed occupancy for RVGE and AGE decreased since introduction of the vaccine.17 There is no discussion of changes in total bed occupancy, or on other proxy measures for hospital pressures following rotavirus vaccine introduction. A study conducted in a general hospital in Belgium (36 paediatric beds) concluded that bed-day occupancy, bed-day turnover and unplanned readmissions for AGE were lower in the postvaccination compared with the prevaccination periods, and that this resulted in improved quality of care for overall admissions.8 In our study, the reduction of bed occupancy for RVGE did not result in a change in overall bed occupancy or other measures of hospital pressure. No change in hospital length of stay for RVGE patients was observed. Median hospital stay for CA RVGE was shorter in Alder Hey NHS Foundation Trust than reported in the Belgian study (2.2 vs 4.1 days), suggesting a difference in management of RVGE cases, and could be an indicator of higher hospital pressure and more rapid patient turnover in Alder Hey.

Several caveats need to be considered when using routinely collected data. Our analysis was complicated by changes in hospital practices, in particular changes in patient flow, laboratory procedures, infection control and clinical coding. First, several wards relevant to this study opened or closed during the study period. Although ward closures were accounted for in the bed occupancy analysis, more subtle changes in patient dynamics still influenced our results. A steep increase was observed for the outlier rate in 2012, with the higher level sustained throughout 2013–2015. The increase in outlier rate is synchronous with the closure of a large general medical ward in November 2011, and the opening of a new medical admission. It is possible that the change in ward structure led to an increased bed usage in surgical and specialised medical wards.

Second, several changes in laboratory procedures were observed during the study period, most notably the introduction of PCR for the rapid testing of respiratory pathogens in 2013. Faster diagnosis of respiratory infection could have had implications for patient treatment, isolation practices and patient flow and could have influenced the measured hospital pressure outcomes. The number of admissions tested for rotavirus did not change significantly over the study period, which provides confidence that the drop in RVGE in the postvaccine era is a real effect, and not caused by a change in testing policy.

Third, there were changes in infection prevention and control (IPC) practices in later years of the study, including an increase in IPC staff; the introduction of isolation and hand hygiene posters, bed space dividers screens and infection control enclosure isolation pods and changes in environmental cleaning. Changes in IPC practices will most likely have resulted in changes in HA infection rates—it is difficult to disentangle their effect on HA infection from any effect due to a reduction in hospital pressures following rotavirus vaccine introduction.

We observed that bed occupancy for any infectious disease increased in the prevaccination period, both within and outside the rotavirus season. An increase in bed occupancy for any respiratory infection (online supplementary figure 3) and any gastroenteritis was observed, but neither increase can fully account for the overall increase in any infection. It is possible that the increase in infection observed is due to an artefact of the recording of the data. Online supplementary figure 4 shows that all clinical diagnostic coding increased over the study period. Clinical diagnostic coding increased for both cases with and without any infection recorded. We observed that bed occupancy for any infection in the rotavirus season was lower than the expected bed occupancy for any infection based on prevaccination estimates. The increase in any clinical diagnostic coding was sustained in 2014 and 2015, providing confidence that our observation of lower than expected bed occupancy for any infection in the postvaccination period is a true finding.

Our analysis highlights the importance of the presentation of data from the full study period in a time-series analysis, rather than restricting the results to a ‘before-after’ comparison, when there is non-homogeneity in disease management, hospital management and data collection over time. A long-term increase in bed occupancy for any infection could be observed (possibly due to an increase in clinical coding) that predated the introduction of vaccination: taking this ongoing increase in admissions coded as infection into account, a reduction in bed occupancy for any infection can be observed.

A further consideration is how changes to the catchment population size and referral patterns during the study period could affect our findings and their interpretation. There has been a small but steady population growth in the surrounding region consistent with a national trend, which could increase demand on the hospital and dampen any effect of rotavirus vaccination on reducing these pressures. Finally, the impact of any changes in referral policy during the study period is difficult to quantity as Alder Hey serves a region of over 7.1 million people.

Routinely collected hospital data can be used for the evaluation of a (vaccination) policy, but our study highlights the difficulty of evaluating a (vaccination) policy in a period with concurrent changes in patient flow, laboratory procedures and IPC practices.

The introduction of rotavirus vaccination has led to a dramatic reduction in hospitalisation for RVGE and thus a reduction in bed occupancy for RVGE. However, overall bed occupancy was not reduced further highlighting the severe strain the NHS is under and that demand is outstripping capacity. Bed occupancy continues to rise and even a highly effective routine vaccine only freed-up beds which were then filled by admissions, making no overall headway into reducing the overall pressures the NHS is facing.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Karl Edwardson, Christine Gerrard, Fiona Hardiman, Carly Quirk and Stephanie Longmuir for their contribution in preparing the datasets required for this study. The authors would also like to thank Business & Decision Life Sciences platform for editorial assistance and manuscript coordination, on behalf of GSK. Stephanie Garcia coordinated manuscript development and editorial support.

Footnotes

Contributors: DH, RPDC, MC, NAC, NF designed the study and wrote the protocol. EH performed the analyses and wrote the manuscript. JSC and MC provided data for the study. NB-Z provided statistical support. DH, RPDC, MC, JSC, NB-Z, NF, NAC provided advice on the understanding of the findings. ET and BS provided external advice. All authors approved the final version of the paper for submission.

Funding: GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA funded this study (NCT03271593) and was involved in all stages of study conduct. GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA also took in charge all costs associated with the development and publication of this manuscript.

Competing interests: Rotarix is a trademark of the GSK group of companies. NAC, NF and DH are in receipt of research grant support from the GSK group of companies for the conduct of the present study. NAC has received honoraria for participation in GSK Rotavirus Vaccine Advisory Board Meetings from the GSK group of companies and from Watermark Research Partners for participation in independent data monitoring committee of GSK-sponsored clinical trials of Rotavirus vaccine. The institution of NAC and NF received grant from the GSK group of companies for the conduct of other analysis, not related to the present work. DH received grants from the GSK group of companies and Sanofi Pasteur, and Merck & Co (Kenilworth, New Jersey, USA) outside the submitted work. NB-Z reports grants from the GSK group of companies and from Takeda Pharmaceuticals outside the submitted work. BS and ET are employees of the GSK group of companies. EH, RC, MC and JC have nothing to disclose.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval was provided by the NHS Research Ethics Committee, North East—Newcastle & North Tyneside 2 and by the Alder Hey Children’s NHS Foundation Trust Research and Development Department.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The results summary for this study (GSK study identifier: 205369—ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03271593) is available on the GSK Clinical Study Register and can be accessed at www.gsk-clinicalstudyregister.com. The full data that support the findings of this study are held by Alder Hey Children’s NHS Foundation Trust and restrictions apply to the availability of these data as they are not publicly available. Aggregated data may be available from the authors/Alder Hey Children’s NHS Foundation Trust on reasonable request and with permission of Alder Hey Children’s NHS Foundation Trust.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Limb M. NHS misses key performance targets again in June. BMJ 2016;354:i4443 10.1136/bmj.i4443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. O’Dowd A. NHS winter pressures are becoming an all year reality, warn experts. BMJ 2016;354:i4907 10.1136/bmj.i4907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Smith P, McKeon A, Blunt I, et al. NHS hospitals under pressure: trends in acute activity up to 2022: Nuffield Trust, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hospital Episode Statistics Anlysis - Health and Social Care Information Centre. Hospital episode statistics - Admitted Patient Care, England - 2014-15, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Health and Social Care Information Centre. Hospital episode statistics – NHS Accident and Emergency Attendences in England - 2014-15, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Torjesen I. Paediatric services can’t fill rotas. BMJ 2016;354:i4495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hungerford D, Read JM, Cooke RP, et al. Early impact of rotavirus vaccination in a large paediatric hospital in the UK. J Hosp Infect 2016;93:117–20. 10.1016/j.jhin.2015.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Standaert B, Alwan A, Strens D, et al. Improvement in hospital Quality of Care (QoC) after the introduction of rotavirus vaccination: An evaluation study in Belgium. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2015;11:2266–73. 10.1080/21645515.2015.1029212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Forster AJ, Stiell I, Wells G, et al. The effect of hospital occupancy on emergency department length of stay and patient disposition. Acad Emerg Med 2003;10:127–33. 10.1197/aemj.10.2.127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Harris JP, Jit M, Cooper D, et al. Evaluating rotavirus vaccination in England and Wales. Part I. Estimating the burden of disease. Vaccine 2007;25:3962–70. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.02.072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Public Health England. National rotavirus immunisation programme: preliminary data for England, February 2016 to July 2016. HPR 2016;10. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Atchison CJ, Stowe J, Andrews N, et al. Rapid Declines in Age Group-Specific Rotavirus Infection and Acute Gastroenteritis Among Vaccinated and Unvaccinated Individuals Within 1 Year of Rotavirus Vaccine Introduction in England and Wales. J Infect Dis 2016;213:243–9. 10.1093/infdis/jiv398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hungerford D, Vivancos R, Read JM, et al. Rotavirus vaccine impact and socioeconomic deprivation: an interrupted time-series analysis of gastrointestinal disease outcomes across primary and secondary care in the UK. BMC Med 2018;16:10 10.1186/s12916-017-0989-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. World Health Organisation. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems - 10th revision, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wilson SE, Deeks SL, Rosella LC. Importance of ICD-10 coding directive change for acute gastroenteritis (unspecified) for rotavirus vaccine impact studies: illustration from a population-based cohort study from Ontario, Canada. BMC Res Notes 2015;8:439 10.1186/s13104-015-1412-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hungerford D, Vivancos R, Read JM, et al. In-season and out-of-season variation of rotavirus genotype distribution and age of infection across 12 European countries before the introduction of routine vaccination, 2007/08 to 2012/13. Euro Surveill 2016;21 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2016.21.2.30106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hartwig S, Uhari M, Renko M, et al. Hospital bed occupancy for rotavirus and all cause acute gastroenteritis in two Finnish hospitals before and after the implementation of the national rotavirus vaccination program with RotaTeq®. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:632 10.1186/s12913-014-0632-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-027739supp001.pdf (570.3KB, pdf)