Abstract

Psoriasis is a common immune-mediated disease that affects 2–4% of individuals in North America and Europe. In the past decade, advances in research have led to an improved understanding of immune pathways involved in the pathogenesis of psoriasis and has spurred the development of targeted therapeutics. Recently, three psoriasis autoantigens have been described: cathelicidin (LL-37), a disintegrin and metalloprotease domain containing thrombospondin type 1 motif-like 5 (ADAMTSL5), and lipid antigens generated by phospholipase A2 group IVD (PLA2G4D). It is important to establish the expression, regulation, and therapeutic modulation of these psoriasis autoantigens. In this study, we performed immunohistochemistry and two-color immunofluorescence on non-lesional and lesional psoriasis skin to characterize ADAMTSL5 and LL-37, and their co-expression with CD3+ T-cells, CD11c+ dendritic cells, and CD163+ macrophages, which are the main immune cells that drive this disease. Our results showed that ADAMTSL5+ and LL37+ cells are significantly (p<0.05) increased in lesional skin and are co-expressed by many dendritic cells, macrophages, and some T-cells in the dermis. Gene expression analysis showed significant (p<0.05) upregulation of LL-37 in lesional skin and significant downregulation following treatment with etanercept. ADAMTSL5+ and LL37+ cells are also significantly decreased by IL-17 or TNFα blockade, suggesting feed-forward induction of psoriasis autoantigens by disease-related cytokines.

INTRODUCTION:

Psoriasis is a common inflammatory skin disease with high prevalence in most industrialized countries [1]. Individuals with psoriasis have thickened, sharply demarcated, erythematous plaques with silver scales [2] and have an increased risk of developing comorbidities such as psoriatic arthritis, Crohn’s disease, depression, cardiovascular disease, and metabolic syndrome [3]. The etiology of psoriasis is not entirely understood, though genetic susceptibility [4] and environmental stimuli [5] are important factors contributing to the pathogenesis of this condition.

Psoriasis is one of the most prevalent T-cell mediated diseases [6]. The effectiveness of immune-modulating medications [6–8] for the treatment of psoriasis underscores the vital role of the immune system and the aberrant adaptive and innate immune responses in psoriasis pathogenesis. Psoriasis has primarily been classified as an immune-mediated inflammatory disorder rather than an autoimmune condition [9] largely due to the fact that no convincing autoantigens had previously been identified. Recently, three psoriasis autoantigens have been reported to be involved in the pathogenesis of psoriasis, namely cathelicidin (LL-37) [10], a disintegrin and metalloprotease domain containing thrombospondin type 1 motif-like 5 (ADAMTSL5) [11], and lipid antigens generated by phospholipase A2 group IVD (PLA2G4D) [12]

LL-37, a keratinocyte-derived antimicrobial peptide overexpressed in psoriatic skin, is a 37 amino acid cationic peptide produced from the extracellular cleavage of the C-terminal end of the 18 kDa hCAP18 protein in keratinocytes [13] and proteinases [14]. LL-37 is upregulated in psoriatic lesions and has been shown to contribute to psoriasis pathogenesis primarily through the activation of dendritic cells (DCs), which subsequently promote the activation and expansion of pathogenic T cells [10,15,16]. A recent study also reported the increased expression of a novel cytosolic Phospholipase A2 lipid antigen, PLA2G4D, in psoriatic lesions [12]. PLA2G4D was observed to be expressed in psoriatic keratinocytes and mast cells and generates lipid antigens that are recognized by CD1a-restricted T-cells thereby inducing the production of IL-22 and IL-17A [12]. Lastly, ADAMTSL5 is a novel protein that is secreted and shown to bind to fibrillin-1 and fibrillin-2 and could play a role in modulating microfibril functions [17]. In psoriasis, ADAMTSL5 was found to be presented by HLA-C*06:02 -restricted melanocytes that activate IL-17-producing T cells [11]. We recently described the diffuse distribution of ADAMTSL5 in lesional and non-lesional psoriatic skin by immunohistochemistry, including its expression in keratinocytes and unidentified dermal cells [18].

In this present study, we sought out to describe the expression of ADAMTSL5 and LL-37 in lesional and non-lesional psoriatic skin, as well as characterize their co-expression within pathogenic immune cells before and after treatment with TNFα and IL-17 antagonists. We show that ADAMTSL5+ and LL-37+ cells are significantly (p<0.05) increased in lesional compared to non-lesional psoriatic skin. Using two-color immunofluorescence, we also show that many ADAMTSL5+ and LL-37+ cells are co-expressed with CD11c+ dendritic cells and CD163+ macrophages in the superficial and deep dermis, as well as some CD3+ T-cells in dermal aggregates. Expression of these autoantigens in skin lesions from patients treated with ixekizumab and etanercept also showed significant (p<0.05) decreases of ADAMTSL5+ and LL-37+. Microarray analysis data of patients treated with brodalumab showed upregulation of both ADAMTSL5 and LL-37 genes in lesional skin with downregulation following treatment.

METHODS:

Patient characteristics

Lesional, non-lesional, and post-treatment (n=10) skin biopsies were obtained from patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis under IRB-approved protocols. Informed consent was obtained and the study was performed in adherence with the Declaration of Helsinki Principles.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) and Immunofluorescence (IF).

Standard procedures were used for IHC and IF as previously described [19]. For IHC, lesional, non-lesional, and post-treatment frozen tissue sections from psoriatic patients were stained with a polyclonal ADAMTSL5 antibody produced in chicken (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO) and two clones of LL-37 antibody (clones H7 and OSX12, Abcam, Cambridge, MA) produced in mouse. Biotin-labeled goat anti-chicken and horse anti-mouse (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) was used to detect the chicken and mouse antibodies, respectively. The staining signal was amplified with avidin-biotin complex (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and developed using chromogen 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). The number of positive cells per mm epidermis surface length was counted manually using computer-assisted image analysis (NIH Image 6.1;http://rsb.info.nih.gov/nih-image).

For two-color immunofluorescence with markers for T-cells (CD3), dendritic cells (CD11c), and macrophages (CD163), frozen tissue sections from psoriatic patients were fixed with acetone and blocked in 10% normal goat serum (Vector Laboratories) for 30 minutes. Tissue sections were incubated with ADAMTSL5 (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO), CD3 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), CD11c (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA), and CD163 (Acris, Rockville, MD) overnight at 4°C and amplified with goat anti-chicken Alexa Fluor 568 (Invitrogen, Eugene, OR) and goat anti-mouse Alexa Flour 488 for 30 minutes the following day. On another set of tissue sections, we incubated the two clones of LL-37 (clones H7 and OSX12, Abcam, Cambridge, MA) antibody overnight at 4°C followed by blocking with 10% normal mouse serum for 30 mins. The same sections were then stained overnight with a FITC labeled CD3 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), FITC labeled CD163 (Acris, Rockville, MD) and zenon-labeled CD11c (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). The tissue sections stained with CD3-FITC and CD163-FITC were then amplified with anti-flourescein Alexa Flour 488 (Invitrogen, Eugene, OR) for 30 mins the following day.

Histologic images were acquired using the appropriate filters of a Zeiss Axioplan 2 widefield fluorescence microscope with a Plan Neofluar 20 × 0.7 numerical aperture lens and a Hamamatsu Orca ERcooled charge-coupled device camera, controlled by METAVUE software (MDS Analytical Technologies, Downington, PA). Images in each figure are presented both as single color stains (green and red) located above the merged image so that localization of two markers on similar or different cells can be appreciated. Cells that co-express the two markers in a similar location are yellow in color. A white line denotes the junction between epidermis and the dermis. Dermal collagen produced green autofluorescence, and antibodies conjugated with a fluorochrome often produced background epidermal fluorescence.

Quantitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR).

RNA was extracted from lesional, non-lesional, and post-treatment skin biopsies using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, U.S.A.). qRT-PCR was performed using EZ PCR core reagents, primers, and probes (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, U.S.A.) as previously published (19). Sequences of primers and probes used in this study are found in Table S1. The results were normalized to the hARP housekeeping gene.

Statistical Analysis.

Quantitative (cell counts) changes in IHC and Log-2 transformed qRT-PCR data were assessed estimating a mixed-effect model with fixed-factors: Time (Baseline/Post-treatment), Tissue (LS/NL) and its interactions, considering random intercept for each patient. P values from the t tests were adjusted for multiple hypotheses using the Bonferroni Correction.

RESULTS:

Distribution and Expression Pattern of ADAMTSL5 and LL-37

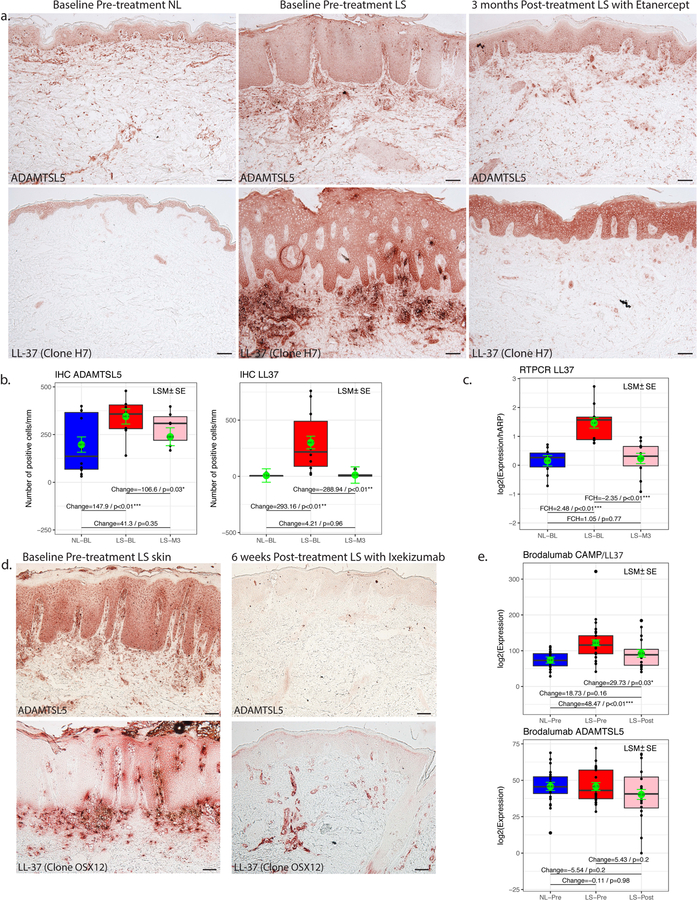

We performed immunohistochemistry staining of ADAMTSL5 and LL-37 on lesional and non-lesional psoriasis tissues to determine the distribution and expression pattern of these antigens (Figure 1). We observed that there was increased expression of both ADAMTSL5 and LL-37 antibodies in lesional compared to non-lesional skin (Figure 1a). In agreement with previously published data, ADAMTSL5 was expressed in keratinocytes and distinct dermal cells in the papillary dermis and near the dermo-epidermal junction (DEJ). LL-37, on the other hand, was more strongly expressed in keratinocytes as well as in dermal cells near the DEJ and cellular aggregates in the superficial and deep dermis. Similar staining patterns were seen with two different clones of LL-37 monoclonal antibodies. We counted the number of ADAMTSL5+ and LL-37+ cells in the epidermis and dermis and found that they were both significantly (p<0.05) increased in lesional skin compared to non-lesional skin (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

(a) Representative immunohistochemistry images for ADAMTSL5 and LL-37 in lesional skin showed increased expression in keratinocytes and dermal cells compared to NL skin and (b) significant (p<0.05) increase in number of ADAMTSL5+ and LL-37+ cells in lesional compared to non-lesional skin. Scale bar = 100 μm. Error bars represent standard errors of the mean and p values are as indicated.

ADAMTSL5+ and LL-37+ cells are co-expressed in dendritic cells and macrophages

To determine which immune cells express the ADAMTSL5 and LL-37 antigens, we performed two-color immunofluorescence on non-lesional and lesional psoriasis skin with markers for dendritic cells (CD11c), macrophages (CD163) and T-cells (CD3) (Figure 2 and 3). We found that many ADAMTSL5+ cells were co-expressed with CD11c+ dendritic cells in the superficial dermis (Figure 2a) and CD163+ macrophages in the deeper dermis (Figure 2b). There were some ADAMTSL5+ cells that also co-expressed with CD3+ T-cells in the dermal aggregates (Figure 2c). Likewise, many LL-37+ cells co-expressed with CD11c+ dendritic cells near the DEJ (Figure 3a), while those in the deeper dermis were co-expressed with CD163+ macrophages (Figure 3b). A few LL-37+ cells were also co-expressed with CD3+ T-cells in the dermal aggregates (Figure 3c).

Figure 2.

(a) Representative two-color immunofluorescence on non-lesional and lesional skin for ADAMTSL5 (red) with CD11c (green) showing co-localization of many ADAMTSL5+ cells with CD11c+ dendritic cells in the superficial dermis and DEJ. (b) ADAMTSL5 (red) with CD163 (green) showing co-localization of many ADAMTSL5+ cells with CD163+ macrophages in the superficial and deep dermis. (c) There were also some ADAMTSL5+ cells that co-localized with CD3+ T-cells in the dermal aggregates. Dermal cells staining positive for both ADAMTSL5 and CD11c, CD163 or CD3 appear as yellow. Scale bar = 100 μm.

Figure 3.

(a) Representative two-color immunofluorescence on non-lesional and lesional skin for LL37 (clone OSX12)(green) with CD11c (red) showing co-localization of many LL37+ cells with CD11c+ dendritic cells near the DEJ. (b) LL37 (clone H7)(red) with CD163 (green) showing co-localization of many LL37+ cells with CD163+ macrophages in the superficial and deep dermis. (c) Some LL37+ cells (red) co-localized with CD3+ T-cells (green) in the dermal aggregates. Dermal cells staining positive for both LL-37 and CD11c, CD163 or CD3 appear as yellow. Scale bar = 100 μm.

ADAMTSL5+ and LL-37+ cells are decreased after treatment.

To show the effect of treatment on ADAMTSL5 and LL-37, we also performed immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining and gene expression analysis on baseline lesional, non-lesional, and post-treatment tissues from patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis treated with etanercept, ixekizumab and brodalumab (Figure 4). Post-treatment biopsies were from patients treated with etanercept for 3 months (Figure 4a–c), ixekizumab for 6 weeks (Figure 4d), and brodalumab for 6 weeks (Figure 4e).

Figure 4.

(a) Representative immunohistochemistry images for ADAMTSL5 and LL-37 on baseline non-lesional, lesional and post-treatment lesional skin of patients treated with Etanercept for 3 months showed increased expression of both antigens in Lesional skin compared to NL skin. (b) Cell counts showed significant (p<0.05) increase of ADAMTSL5+ and LL-37+ cells in lesional compared to NL skin, and significant decrease in post-treatment compared to baseline lesional skin. (c) qRT-PCR showed significant downregulation of ADAMTSL5 in LS compared to NL skin and upregulation in post-treatment compared to baseline lesional skin. (d) Representative immunohistochemistry images for ADAMTSL5 and LL-37 (clone OSX12) on baseline and post-treatment lesional skin of patients treated with Ixekizumab for 6 weeks showed increased expression of both antigens in Lesional skin compared to NL skin. Scale bar = 100 μm. (e) In patients treated with Brodalumab for 6 weeks, there was significant upregulation in gene expression of LL-37 in lesional compared to NL skin and significant downregulation in post-treatment compared to baseline lesional skin. Shown are average normalized log expression values for non-lesional, lesional and post-treatment (n=6). Error bars represent standard errors of the mean and p values are as indicated.

For patients treated with etanercept, IHC staining showed increased expression of ADAMTSL5 and LL-37 on keratinocytes and dermal cells in baseline lesional skin compared to non-lesional skin and a subsequent decreased expression in post-treatment lesional skin (Figure 4a). Cell counts showed significant (p<0.05) increases in ADAMTSL5+ and LL-37+ positive cells in lesional skin compared to non-lesional skin and a significant decrease in the number of ADAMTSL5+ and LL-37+ cells in post-treatment lesional skin compared to baseline lesional skin (Figure 4b). qRT-PCR also showed significant (p<0.05) up-regulation in gene expression of LL-37 in baseline lesional compared to non-lesional skin and significant down-regulation in post-treatment lesional compared to baseline lesional skin (Figure 4c).

In patients treated with ixekizumab, IHC staining showed increased expression of ADAMTSL5 and LL-37 on keratinocytes and dermal cells in baseline lesional skin and a subsequent decreased expression in post-treatment lesional skin (Figure 4d).

We also looked into the possibility that ADAMTSL5 and LL-37 are IL-17-regulated molecules, so we checked our microarray analysis data of patients treated with brodalumab (Figure 4e). We found significant (p<0.05) upregulation of LL-37 in lesional skin compared to non-lesional skin and significant (p<0.05) downregulation following treatment. We also noted upregulation of ADAMTSL5 in lesional skin and downregulation following treatment. There was a positive correlation between LL37 and IL17A, as well as LL37 and IL17F (Supplemental Figure S1).

DISCUSSION:

Psoriasis has been characterized as a T-cell mediated disorder with a probable autoimmune pathogenesis due the following: (1) a strong association with the HLA-C*06:02 allele, the primary psoriasis susceptibility locus; (2) the absence of an identified infectious agent or exogenous antigen that triggers the development of disease; and (3) the clinical efficacy of immunomodulatory agents directed against T-cells [20]. Recently, multiple studies have described several autoantigens involved in the pathogenesis of psoriasis including LL-37 [10], ADAMTSL5 [11], and lipid antigens generated by PLA2G4D [12], thus suggesting psoriasis is an autoimmune disease.

Our group recently published the cutaneous expression of ADAMTSL5 in psoriatic lesional and non-lesional skin and showed that this antigen is not only expressed by melanocytes but also by keratinocytes and discrete but undefined dermal cells near the DEJ and in the superficial and deep dermis [18]. In this present study, we show that LL-37 is also widely expressed in keratinocytes and many dermal cells. Using two-color immunofluorescence, we also show that many LL37+ and ADAMTSL5+ cells are co-expressed with CD11c+ dendritic cells in the superficial dermis and near the DEJ, as well as CD163+ macrophages in the deeper dermis. Some LL37+ and ADAMTSL5+ cells also co-expressed with CD3+ T-cells that form aggregates in the superficial dermis. This fits our working model for psoriasis suggesting that several immune cells (e.g. DCs, macrophages) may present these antigens to autoreactive Th17 cells with ensuing activation and clonal expansion [21].

Cathelicidins are a gene family that are known for their antimicrobial action. The human cathelicidin peptide, LL-37, is a keratinocyte-derived antimicrobial peptide that is strongly expressed in the epidermis and dermis of lesional psoriatic skin [15]. In response to skin trauma or viral/bacterial infections, LL-37 forms complexes with extracellular self-nucleic acids and promotes loss of immune tolerance through the stimulation of endosomal toll-like receptor (TLR)-7/9 and TLR-8 in plasmacytoid (pDC) and myeloid (mDC) dendritic cells, respectively [15–16]. The activation of pDCs and mDCs subsequently promote the expansion of T cells that produce IFN-γ and Th17 cytokines [10]. A recent study showed that LL-37 was recognized as an autoantigen by circulating T-cells in up to 75% of patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis and triggers activation of innate immune cells [13]. In macrophages, LL-37 promotes cell differentiation towards a proinflammatory signature. In one study, monocytes cultured with M-CSF in the presence of LL-37 resulted to a proinflammatory macrophage differentation, while the peptide also enhanced the GM-CSF-driven macrophage differentiation [22]. LL-37 was reported to be internalized by human macrophages through the P2X7 receptor and the LL-37/P2X7R complex is associated with clathrin-mediated endocytosis [23]. Taken together, the primary mechanisms by which LL-37 appears to contribute to the development of psoriasis is 1) through the early stimulation of pathogenic immune cells, specifically the pDC and mDC populations, and 2) by serving as an autoantigen for the activation of IFN-γ and Th17-producing T cells.

Another group identified ADAMTSL5 as an autoantigen for IL-17-producing CD8+ T cells in psoriasis when presented by HLA-C*06:02 [14]. ADAMTSL5, a novel protein reportedly produced by melanocytes, was discovered in the late 2000s and appears to be important for microfibril function [11]. This protein may be distributed on epithelial cells and connective tissues during mouse embryonic development and localized on the pericellular and subcellular extracellular matrix of cells [17]. ADAMTSL5 may be an intracellular antigen in keratinocytes or dermal connective tissue cells or an extracellular deposition and it may trigger the reactivity of immune cells like dendritic cells and macrophages [21]. The mechanism by which the antigen is taken up by immune cells is still not yet understood.

It is interesting to note that both LL-37 and ADAMTSL5 are directly or indirectly regulated by IL-17 [20]. IL-17 increases transcription of LL-37 and induces the production of CXCL1 (a chemokine that was first identified as a melanocyte growth factor), which could stimulate melanocytes for ADAMTSL5 expansion in psoriatic lesions [21]. Our findings that both ADAMTSL5 and LL-37 are broadly expressed in keratinocytes and co-expressed with many dendritic cells and macrophages in psoriasis lesions suggests the possibility that activating DCs may become more sensitive as an antigen presenting cell irrespective of the antigen. Alternatively, the expression of autoantigens in keratinocytes could also create the potential for these antigens to be processed by MHC class I molecules and, in the process, become target cells for autoreactive T cells found in psoriatic skin.

The association between PLA2G4D and psoriasis is significant for several reasons. First, PLA2G4D is a novel phospholipase A2 (PLA2) enzyme that is absent is normal, healthy skin [24]. Second, its expression along with PLA2 activity is increased in psoriatic skin lesions [25]. Third, the increased PLA2G4D expression in mast cells and keratinocytes results in the generation of non-peptide, lipid antigens that are recognized by CD1a-restricted T cells, which produce high amounts of Th-1 and Th-17 cytokines [12]. These findings provide evidence for the potential role of non-peptide antigens in the pathogenesis of psoriasis, which could explain why subsets of psoriasis patients lack LL-37 or ADAMTSL5-specific T cells. Unfortunately, these lipid antigens are more difficult to characterize since they cannot be stained using traditional immunohistochemical antibodies – one limitation of our present study. Additional larger studies are needed to fully characterize the expression profiles of LL-37 and ADAMTSL5 in the skin and to determine their function in non-DC and macrophage immune cells.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Correlation plot between LL37 and IL17A/F

Table S1. Table of Antibodies used for IHC/IF and Primers for qRT-PCR

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS:

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant UL1 RR024143 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR). JEH and JGK were supported in part by grant # UL1TR001866 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), National Institutes of Health (NIH) Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program. The content of this study is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

J.G.K. has been a consultant to and has received research support from companies that have developed or are developing therapeutics for psoriasis: Abbvie, Amgen, Boehringer, Bristol-Myers-Squibb, Celgene, Dermira, Idera, Janssen, Leo, Lilly, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sanofi, Serono, Sun, Valeant, and Vitae.

ABBREVIATIONS USED:

- ADAMTSL5

- LL-37

- PLA2G4D

- DC

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The other authors state no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES:

- 1.Parisi R, Symmons DPM, Griffiths CEM, Aschroft DM, Identification and Management of Psoriasis and Associated ComorbidiTy (IMPACT) project team. Global epidemiology of psoriasis: a systematic review of incidence and prevalence. J Invest Dermatol 2013;133(2):377–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lowes MA, Bowcock AM, Krueger JG. Pathogenesis and therapy of psoriasis. Nature 2007;445(7130):866–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oliveira Mde F, Rocha Bde, Duarte GV. Psoriasis: classical and emerging comorbidities. An Bras Dermatol 2015;90(1):9–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harden JL, Krueger JG, Bowcock AM. The immunogenetics of psoriasis: a comprehensive review. J Autoimmune 2015;64:66–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boehncke W-H, Schön MP. Psoriasis. Lancet 2015;386(9997):983–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gottlieb SL, Gilleaudeau P, Johson R, Estes L, Woodworth TG, Gottlieb AB, Krueger JG. Response of psoriasis to a lymphocyte-selective toxin (DAB389IL-2) suggests a primary immune, but not keratinocyte, pathogenic basis. Nat Med 1995. May;1(5):442–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gubner R Effect of ‘aminopterin” on epithelial tissues. Arch Dermatol 1983;119(6):513–24 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krueger JG, Ferris LK, Menter A, Wagner F, White A, Visvanathan S, lalovic B, Aslanyan S, Wang EEL, Hall D, Solinger A, Padula S, Scholl P. Anti-IL-23A mAb BI 655066 for treatment of moderate-to-severe psoriasis: safety, efficacy, pharmacokinetics, and biomarker results of a single-rising-dose, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015;136(1):116–124.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuek A, Hazleman BL, Östör AJK. Immune-mediated inflammatory diseases (IMIDs) and biologic therapy: a medical revolution. Postgrad Med J 2007;83(978):251–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lande R, Botti E, Jandus C, Dojcinovic D, Fanelli G, Conrad C, Chamilos G, Feldmeyer L, Marinari B, Chon S, Vence L, Riccieri V, Guillaume P, Navarini AA, Romero P, Costanzo A, Piccolella E, Gilliet M, Frasca L. The antimicrobial peptide LL37 is a T-cell autoantigen in psoriasis. Nat Commun 2014;5:5621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arakawa A, Siewert K, Stöhr J, Besgen P, Kim S-M, Rühl G, Nickel J, Vollmer S, Thomas P, Krebs S, Pinkert S, Spannagl M, Held K, Kammerbauer C, Besch R, Dornmair K, Prinz JC. Melanocyte antigen triggers autoimmunity in human psoriasis. J Exp Med 2015;212(13):2203–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheung KL, Jarrett R, Subramaniam S, Salimi M, Gutowska-Owsiak D, Chen YL, Hardman C, Xue L, Cerundolo V, Ogg G. Psoriatic T cells recognize neolipid antigens generated by mast cell phospholipase delivered by exosomes and presented by CD1a. J Exp Med 2016. September 26 pii: jem.20160258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Yamasaki K, Schauber J, Coda A, Lin H, Dorschner RA, Schechter NM, Bonnart C, Descargues P, Hovnanian A, Gallo RL. Kallikrein-mediated proteolysis regulates the antimicrobial effects of cathelicidins in skin. Faseb J 2006; 20:2068–2080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sørensen OE, Follin P, Johnsen AH, Calafat J, Tjabringa GS, Hiemstra PS, Borregaard N. Human cathelicidin, hCAP-18, is processed to the antimicrobial peptide LL-37 by extracellular cleavage with proteinase 3. Blood 2001; 97:3951–3959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lande R, Gregorio J, Facchinetti V, Chatterjee B, Wang YH, Homey B, Cao W, Su B, Nestle FO, Zal T, Mellman I, Schroder JM, Liu YJ, Gilliet M. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells sense self-DNA coupled with antimicrobial peptide. Nature 2007; 449:564–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ganguly D, Chamilos G, Lande R, Gregorio J, Meller S, Facchinetti V, Homey B, Barrat FJ, Zal T, Gilliet M. Self-RNA-antimicrobial peptide complexes activate human dendritic cells through TLR7 and TLR8. J Exp Med 2009. August 31;206(9):1983–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bader HL, Wang LW, Ho JC, Tran T, Holden P, Fitzgerald J, Atit RP, Reinhardt DP, Apte SS. A disintegrin-like and metalloprotease domain containing thrombospondin type 1 motif-like 5 (ADATMSL5) is a novel fibrillin-1-, fibrillin-2-, and heparin-binding member of the ADATMS superfamily containing a netrin-like module. Matrix Biol 2012. September-October;31(7–8):398–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bonifacio KM, Kunjravia N, Krueger JG, Fuentes-Duculan J. Cutaneous expression of a disintegrin-like and metalloprotease domain containing thrombospondin type 1 motif-like 5 (ADAMTSL5) in psoriasis goes beyond melanocytes. J Pigment Disord 2016. October;3(3). pii: 244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fuentes-Duculan J, Suárez-Fariñas M, Zaba L C, Nograles KE, Pierson KC, Mitsui H, Pensabene CA, Kzhyshkowska J, Krueger JG, Lowes MA. A subpopulation of CD163-positive macrophages is classically activated in psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol 2010: 130: 2412–2422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krueger JG. An autoimmune “attack” on melanocytes triggers psoriasis and cellular hyperplasia. J Exp Med 2015. December 14;212(13):2186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim J, Krueger JG. Highly Effective New Treatments for Psoriasis Target the IL-23/Type 17 T Cell Autoimmune Axis. Annu Rev Med 2016. September 23 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Van Der Does AM, Beekhuizen H, Ravensbergen B, Vos T, Ottenhoff THM, van Dissel JT, Drijfhout JW, Hiemstra PS, Nibbering PH. LL-37 directs macrophage differentiation toward macrophages with a proinflammatory signature. J Immunol 2010; 185:1442–1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tang X, Basavarajappa D, Haeggström JZ, Wan M. P2X7 receptor regulates internalization of antimicrobial peptide LL-37 by human macrophages that promotes intracellular pathogen clearance. J Immunol 2015;195(3):1191–1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chiba H, Michibata H, Wakimoto K, Seishima M, Kawasaki S, Okubo K, Mitsui H, Torii H, Imai Y. Cloning of a gene for a novel epithelium-specific cytosolic phospholipase A2, cPLA2delta, induced in psoriatic skin. J Biol Chem 2004. March 26;279(13):12890–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quaranta M, Knapp B, Garzorz N, Mattii M, Pullabhatla V, Pennino D, Andres C, Traidl-Hoffmann C, Cavani A, Theis FJ, Ring J, Schmidt-Weber CB, Eyerich S, Eyerich K. Intraindividual genome expression analysis reveals a specific molecular signature of psoriasis and eczema. Sci Transl Med 2014. July 9;6(244):244ra90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Correlation plot between LL37 and IL17A/F

Table S1. Table of Antibodies used for IHC/IF and Primers for qRT-PCR