Abstract

When the Deepwater Horizon oil rig blew out in 2010, the immediate threats to productive deep water and estuarial fisheries and the region’s fishing and energy economies were obvious. Less immediately obvious, but equally unsettling, were risks to human health posed by potential damage to the regional food web. This paper describes grassroots and regional efforts by the Gulf Coast Health Alliance: health risks related to the Macondo Spill Fishermen’s Citizen Science Network project. Using a community-based participatory research approach and a citizen science structure, the multiyear project measured exposure to petrogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, researched the toxicity of these polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon compounds, and communicated project findings and seafood consumption guidelines throughout the region (coastal Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama). Description/analysis focuses primarily on the process of building a network of working fishermen and developing group environmental health literacy competencies.

Keywords: CBPR, citizen science, petrogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, environmental health literacy, cumulative risk

Introductiona

GC-HARMS Regional Fishermen’s Citizen Science Network: Social Context and Process Overview

When the Deepwater Horizon (DWH) semisubmersible drilling rig exploded in April 2010, the ensuing catastrophe set off a chain reaction of adverse consequences for residents of fishing communities along the northern Gulf coast of the United States. The obvious difficulties experienced by responsible parties in stemming the oil flow and protecting estuarial waters and marshes damaged public confidence in the overall disaster response. Divergent estimates of the rate of oil flow and routes of plume proliferation complicated the task of gathering spilled oil and preventing the incursion of plumes into prime areas of the gulf fishery. The sheer volume of oil released caused a series of fishing closures in federal and state waters at the very onset of shrimping season, a situation particularly threatening to local small-scale commercial and subsistence economies. Early dissonance in messaging around the risk posed by direct exposure to crude oil in the environment and consumption of exposed seafood caused confusion both for coastal residents and within the public health community. Finally, the use of relatively underresearched dispersant agents during the industrial spill abatement response compounded this confusion and added the possibility of another exposure risk to the ecosystem and human health. Certainty regarding the safety of the food web so vital to the sustainability of north gulf-fishing communities was nowhere evident, and trust in agencies charged with protecting human health and managing natural ecosystems was badly eroded during the early stages of the DWH crisis.1

In response to the public health crisis, the U.S. National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) sought proposals for its research program, DHW Disaster Research Consortia: Health Impacts and Community Resiliency, which were to include a strongly supported Community Outreach and Dissemination Core (CODC).2 Research funding was awarded to a university-community consortium that cocreated Gulf Coast Health Alliance: health Risks related to the Macondo Spill (GC-HARMS). This project’s research on petrogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) exposures and health impacts was designed as community-based participatory research (CBPR).3 This decision stemmed from positive outcomes with a similar approach to environmental public health research in the Houston area: Project COAL (Communities Organized Against Asthma & Lead), a multiyear program to collaboratively assess threats from lead exposure and asthma triggers in near North Side Houston Latino neighborhoods.4 Potential community partners and the GC-HARMS science team hoped that this approach would repair trust and promote maximum empowerment for affected communities as they collaborated with university science teams in addressing health risks and economic damage stemming from the DWH disaster.3,5

The WK Kellogg Foundation Community Health Scholars Program defines CBPR as follows:

... a collaborative approach to research that equitably involves all partners in the research process and recognizes the unique strengths that each brings. CBPR begins with a research topic of importance to the community and has the aim of combining knowledge with action and achieving social change ...6

A CBPR approach values selection of a research focus that reflects community-identified needs, a commitment to trust and mutuality, and sharing of resources and data. This genre of community research promotes inclusion, integrates transparency into every aspect of the process, builds bi/multidirectional communication relationships, and mandates a democratic decision-making process.6,7 Because CBPR practices are premised on close involvement of community partners in management of research and project logistics, this approach seemed the best means for developing mutual respect and procedural justice among collaborators with a wide range of priorities and points of view.5–11

In order to include affected communities directly in formulating the study design and ensure that the project addressed identified community research needs, the University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB) NIEHS P30 Center in Environmental Toxicology Community Outreach and Engagement Core staff conducted a preproject phone survey of community organizations with which the Community Outreach and Engagement Core had established a prior working relationship through participation in a preexisting regional Environmental Justice Encuentro Network.12 Suggestions from the original core of community partners expanded the range of this convenience sample, and eventually, twenty-six separate community-based organizations responded to informal queries on possible research priorities, current and past levels of involvement with the disaster, and general vision and focus of their organization’s activities. The organizations also were asked to gauge their interest in doing this type of labor-intensive work and their capacity to serve as an active component of a long-term research and resiliency-building team (See Table 1).

Table 1.

Environmental Health Network Scoping Survey.

| 1. | What scientific and/or medical information about the long- or short-term effects of the gulf oil spill on human health does your organization need to better serve the needs of your community (or constituency)? |

| 2. | In light of the oil spill, what needs and priorities are at the top of the list for the regions and issues your organization represents? |

| 3. | Would you be willing to participate in a community-based participatory process: to identify needs, frame scientific questions, and conduct collaborate research on environmental exposure/human health issues related to or stemming from the gulf oil spill? |

| 4. | How do you see your organization’s role in such a CBPR process? (both directly active and support roles) |

| 5. | Would you like to suggest other community-based organizations that could make significant contributions to this project? |

| 6. | What would be the easiest, most convenient way for your organization to communicate with the group on an ongoing basis? (e-mail, phone conference, other) |

| 7. | Would you be available for face-to-face meetings or in-the-field briefings if travel/expense subsidies were available? Do you have any suggestions for a large meeting venue that maximizes accessibility for all? |

| 8. | What barriers to full participation can you anticipate before we even begin to work together? (These barriers could stem from race, class, geography—any factors that affect the power dynamic or flow of logistical resources—or lack of basic organizational resources due to the pressures of the oil crisis, the economy, and ongoing hurricane recovery.) (Questions were used by CODC staff to guide phone conversations with environmental nonprofits in Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama and Texas prior to initiating ground-level planning for GC-HARMS) |

Note. CODC = Community Outreach and Dissemination Core; GC-HARMS = Gulf Coast Health Alliance: health Risks related to the Macondo Spill.

Responses from community-based organizations echoed a similar priority for research focused on current safety of the food web and natural ecosystems, the risks to human health from continued consumption of gulf seafood, and resiliency challenges faced by fishing communities, given the harsh economic realities of fishing closures and a widespread national perception that gulf seafood may no longer be safe to consume.12 These expressed needs were integrated into a research proposal that focused on the health effects of exposure to petrogenic PAH components of crude oil and understanding how population health and social-economic factors may undermine or strengthen community resilience in the Gulf.2,3

GC-HARMS, the Resultant NIEHS-Funded Study, Consisted of the Following Components

The study included three projects. Through Project 1, cohorts of exposed gulf-fishing community members living in coastal Louisiana and Mississippi received comprehensive health assessments which included measures of petrogenic PAH in biospecimens (blood/urine) and exposure-related health effects. Project 1 also investigated inherent/traditional community resilience in affected communities; these findings were translated to shape outreach and engagement activities with stakeholder communities. The seafood sampling process was included as a function of Project 1.3

Project 2 consisted of (a) exposure assessment and biomonitoring research in seafood and human population and also used (b) Inverse Modeling to predict future exposure risks in the event of another drilling/exploration or shipping-related disaster3 (see Reference Supplement 1: Inverse Modeling).

Project 3 focused on developing toxicological characterizations of target pet-rogenic PAH in the DWH oil spill by (a) evaluating toxicity of selected alkylated and oxygenated PAH, and PAH extracts from seafood using validated cell-based assay systems and (b) characterizing the metabolism of the petro-genic PAH.3

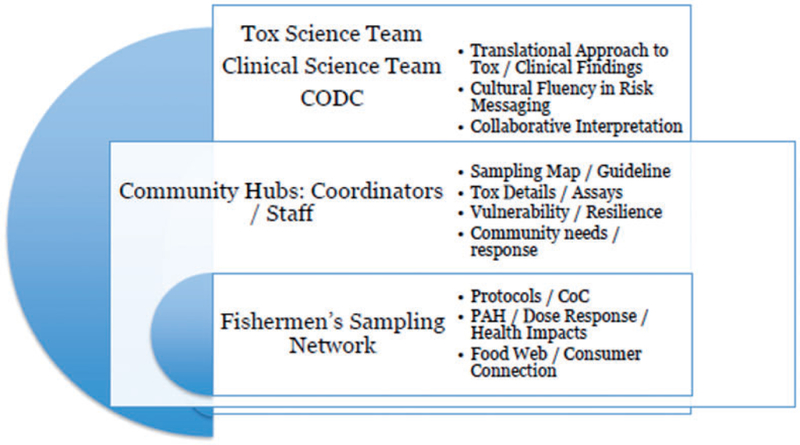

A CODC served as connective tissue uniting scientific research teams, community-based organizations (hubs), and regional fishermen in a multidirectional communication network to identify and prioritize needs, answer environmental health questions, develop community-specific frameworks for data analysis, share project findings, and shape their interpretation. The major task of the CODC was maintaining a complex CBPR partnership throughout the course of the study, serving as a communication channel among research collaborators and geographically distant—in some cases, very isolatedcommunity hubs.3

The CODC was charged with delivering a seafood consumption guideline based on research findings and disseminating a comprehensive risk communication message that reflects the project’s toxicological findings. These messages were created in collaboration with community hubs to ensure that basic science and epidemiologic analysis translated fluently across culture and geography. Ultimately, an iterative series of public forums and two web-based tools—a sampling site map (http://gcharms.leanweb.org/seafood-sampling-map/) and a seafood portions calculator (https://www.utmb.edu/scg/)—were produced to ground the project’s toxicological findings in the cultural lifeways of the region. The GC-HARMS Citizen Science (Citizen Science) Network was originally conceived as an engagement, education, and dissemination strategy to meet these CODC environmental health communication goals, as well as a means of physically sampling marine organisms from the food web.3,13,14

Six community hubs were created across the tristate area: three in Louisiana, two in Mississippi, and one in Alabama. Three major hubs were designated for coordination of this community field science network of fishermen. These sampling hubs with affiliated community organizations were located at Houma, LA (United Houma Nation); Gulfport, MS (Vietnamese Community Partner); and Coden-Bayou la Batre, AL (South Bay Communities Alliance and Alabama Fisheries Cooperative).3,12 After notification by NIEHS that the GC-HARMS project would be funded, but before the actual funding stream was officially established, the lead institution, UTMB at Galveston, TX, leveraged existing monies to launch a pilot project for developing and field testing a model of collaboration with local fishermen. The objectives of fieldwork on the water were to obtain seafood samples for laboratory assays that would establish pet-rogenic PAH content and suggest potential toxicity and to select sampling sites based on environmental observations. This model was developed primarily through collaboration between the GC-HARMS science team, community hub coordinators, and the Louisiana Environmental Action Network (LEAN) community science consultant and MacArthur Fellow, Wilma Subra.12,14 The seafood sampling pilot project was launched in July 2011 in Mobile Bay.

Sampling protocols derived from Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)-approved procedures were incorporated into hands-on text, chart, and oral PowerPoint presentations geared toward an audience of working fishermen and concerned community members.15 Standardizing procedures for maintaining purity of samples, accurate collection of data on environmental conditions while sampling, careful recording of each site’s geographical position (expressed as GPS coordinates), and maintenance of chain of custody (CoC) were primary outcome goals for basic science. Enhancing regional environmental health literacy and building community hub capacity to understand and subsequently interpret the scientific concepts underlying GC-HARMS were equally important process-driven resiliency goals.14

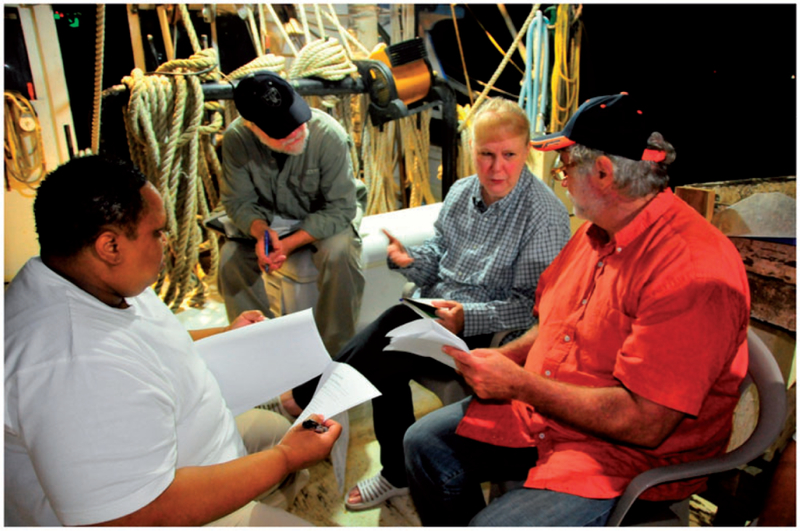

Based on pilot results—in terms of both toxicological findings and process efficacy—a comprehensive proposal, covering research goals, timelines, and sampling logistics, was developed by community hub coordinators, GC-HARM project scientists, and Wilma Subra. Before actual implementation of the funded program in December 2011, this proposal was presented to fishermen and community members at sites in Dulac, LA; Gulfport, MS; and Coden, AL. The project components in this proposal included (a) presentation of proposed project goals and objectives, (b) developing functional definitions and promoting community discussion of important scientific terms: petrogenic PAH, bioavailability, bioaccumulation, dose-response parameters, environmental health risk, community resiliency, (c) reviewing proposed outline of sampling protocols, techniques, and equipment for use onboard fishing vessels, (d) providing overview of data collection, organization, and recording steps, (e) explaining protocols for maintenance of CoC throughout the process, (f) demonstrating sample preparation for shipping and/or pickup, and (g) codeveloping project protocols for discussion of findings as the data evolved.12,14 Feedback from fishermen and community members attending these presentations informed the final version of the engagement process and the citizen science protocols. The fishermen were also encouraged to log or otherwise report observations of changes in environmental conditions and were directly responsible for choosing sample sites which, in most cases, reflected the most productive seasonal fishing waters from past experience. Results of the pilot were overwhelmingly positive and feedback from fishermen was incorporated into refinements of materials and process. Fishermen and hub coordinators were also instrumental in targeting specific finfish species for capture, based on their knowledge of local consumption preferences.5,9,14

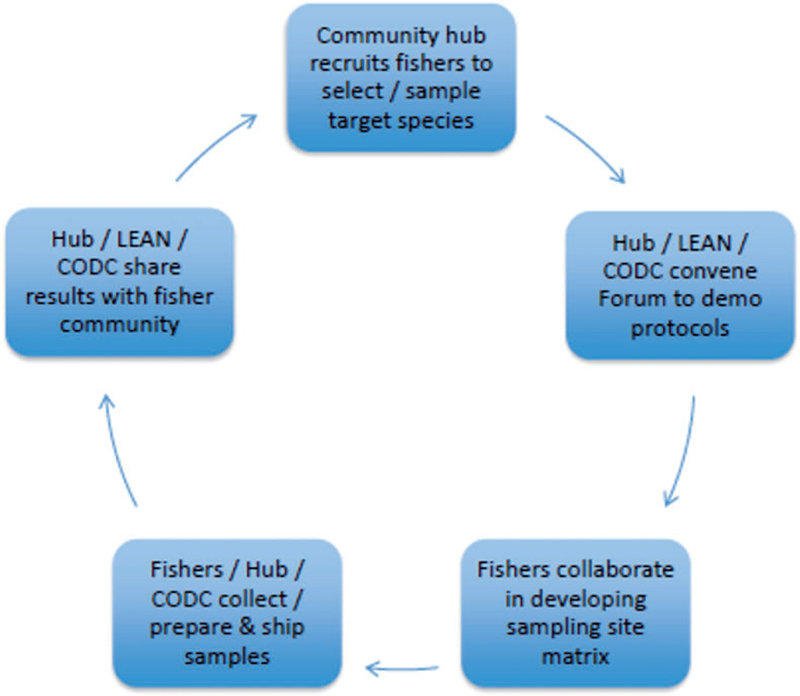

As soon as community hub organizations approved final versions of process protocols, the program officially rolled out in December 2011. Fishermen’s Forums for working (or retired) fisherfolk, their families, and other concerned community residents were facilitated in five locations throughout the Louisiana United Houma Nation catchment area (Houma, Galliano in Terrebonne/ Lafourche Parishes, Lafitte in Jefferson Parish, Buras in Plaquemines Parish, and Los Islenos in St. Bernard Parish). Similar forums were convened in Gulfport-Biloxi, MS and Coden-Bayou la Batre and Theodore, AL. The Fishermen’s Forum series was produced through collaborative efforts of community hub coordinators from the United Houma Nation, the project’s Vietnamese-American community partner, the Alabama Fisheries Cooperative, and CODC field staff based at UTMB. These forums served a dual purpose: as opportunities for bidirectional exchange of information and commentary on the project and as venues to recruit area fishermen as participants in the sampling process. Recruitment efforts targeted small-scale commercial and subsistence shrimpers, crabbers, and oystermen, as well as recreational fin fishermen (See Figure 1).14,16

Figure 1.

GC-HARMS community fishermen training: work flow process map.

CODC = Community Outreach and Dissemination Core; LEAN = Louisiana Environmental Action Network.

The format for on-site Fishermen’s Forums evolved during the initial year of these presentations as audience feedback asked for less scientific jargon (though not less actual science), more practical advice on validity of existing seafood consumption guidelines as communities continued to eat from the local-regional food web, and more attention to adverse physical changes in the fishery, post DWH.17,18 Per the iterative nature of the Forum design, variability in environmental health literacy levels became a primary factor in selecting relevant science and the verbal-visual framing for these presentations. Finfish collection protocol materials were modified to include (a) a diagram illustrating a point under the dorsal fin where the person performing sampling should harvest a one cubic inch dorsal plug for methyl mercury assay of finfish tissue and (b) provision of kits containing all materials necessary for cleaning, packaging, and labeling various parts of finfish specimens. A series of questions designed by Project 2 Co-Principal Investigator, Gilbert T. Rowe (Texas A&M University), pertinent to fishermen working on the water was used as a guide to discussions of changes and/or damage to ecosystem. Information from these discussions served as ground-truthing experiences for affected communities and often informed future choices of sampling locations (See Table 2).

Table 2.

Questions Used to Guide Discussion of Fishermen’s Field Observations.

| (Note to fishermen: Observations can come from anywhere possible evidence of oil-related changes are encountered—oyster reefs, up in the marshes and bayous, down at the cuts to the Gulf, offshore, near oil rigs, offshore banks, etc.) | |

| 1. | Where have you found any oil or oil-derived materials such as tar balls? |

| 2. | Has the species composition of what you catch changed? This should include by-catch too. |

| 3. | Do the species you catch look normal? Has that changed over time? |

| 4. | Do the species you catch seem to be reproducing a normal way, at normal rates and normal times? Have you seen anything unusual in terms of reproduction? |

| 5. | What species of finfish do you eat most often? What species of finfish are most popular where you live? Has oil in the water or any other changes in these species interrupted traditional patterns of finfish consumption? |

| 6. | Does your gear get oily during use? If so, where and when and how often does this occur? |

| 7. | What waters are still oily? Where do you find the oil? Do you find that the oil is disappearing? Is it moving? If so, where and how fast? (Discussion points created by Gilbert T. Rowe, PhD; Texas A&M University at Galveston TX) |

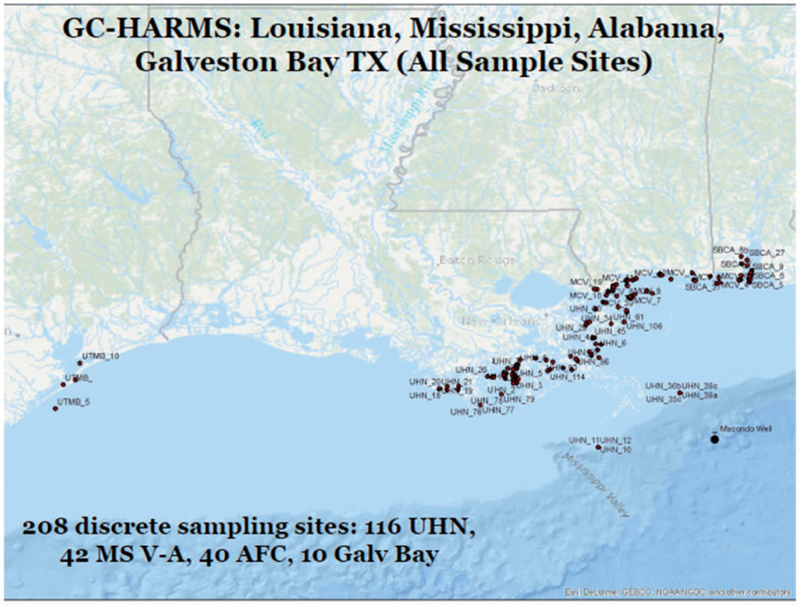

Despite some attrition within the Fishermen’s Citizen Science Network during the formal seafood-sampling period (December 2011–January 2014), community fishermen successfully followed project protocols to collect samples of shrimp (brown-white), blue crab, oysters, and a variety of finfish species including speckled trout, red fish (red drum), black drum, sheepshead, flounder, red snapper, and grouper. In total, community fishermen collected marine life samples at 198 sites within the tristate coastal area. Individual sport fishermen and project CODC staff collected marine organisms at an additional ten sample sites in Galveston Bay for use as comparative “controls” which brought the total of discrete sites to 208 (See Figure 2).12,14

Figure 2.

Regional seafood sampling matrix developed in collaboration with GC-HARMS Citizen Science Network Fishermen (December 2011-January 2014).

(Points indicate GPS-located sites where seafood samples were taken by Citizen Science Network Fishermen from United Houma Nation (LA), Mississippi Coalition of Vietnamese- American Fisherfolk and Families (Gulfport/Biloxi, MS), and Alabama Fisheries Cooperative (Bayou la Batre/Coden, AL.)

AFC = Alabama Fisheries Cooperative; GC-HARMS = Gulf Coast Health Alliance: health Risks related to the Macondo Spill; UHN = United Houma Nation.

From the perspective of CBPR practice values, science work flow and basic environmental health literacy outcomes, the Fishermen’s Citizen Science Network fulfilled its open-ended mission, but the path from inception to creation was not without its pitfalls, setbacks, and delays.5,12,14,19

Assessing Challenges Specific to Direct Involvement of Gulf Fishermen in Citizen Field Science

Beyond the practical logistics of juggling weather, complicated geography—on some occasions beyond the reliable reach of smartphone GPS apps—equipment failures, and the general unpredictability of aquatic species, GC-HARMS CODC staff confronted multiple challenges many of which derived directly from the social/political dynamics surrounding the DWH spill in the early stages of framing the Fishermen’s Citizen Science Network. Much of that early difficulty stemmed from a basic lack of public trust based on what was perceived as self-serving publicity statements and ineffectual capping and abatement efforts on the part of the responsible party.1,8,12,14 Official industry estimates of the rate of flow for crude oil released from the damaged wellhead grew steadily larger as the crisis persisted and early efforts by the responsible party to cap the gusher—specifically the top hat and junk shot strategies—fizzled in full view on a world stage. The decision to use Corexit 9500A and related crude oil dispersants seemed fraught with potential for unknown risks to the ecosystem and human health and, again, appeared calculated to mask the scope of the release and consequent damage.1,20 Inconsistencies in training and use of personal protective equipment within the Vessels of Opportunity program and difficulties faced by individuals seeking local physicians with expertise in occupational and environmental health compounded the confusion and sense of moral outrage in coastal fishing communities.21,22 In addition, the official seafood consumption guideline developed and widely disseminated by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration was criticized as unrealistic because it failed to address genomic and cultural diversity in the Gulf population and ignored the special needs of vulnerable populations.18,22 All of these issues were raised and debated at numerous community forums throughout the tristate region; CODC field staff attended these events in communities such as Dulac, Montegut, Houma, Diamond, New Orleans (all south Louisiana); Biloxi, MS and Coden, AL throughout the preproject scoping phase of GC-HARMS.12,14

Another daunting aspect of the situation derives from the multilayered cumulative risk burdens of many coastal communities in the north Gulf. A succession of strong hurricanes from 2005 to 2012 left a legacy of unmet housing needs, damaged infrastructure, and economic dislocation from which the area, despite its inherent resilience, had yet to fully recover.23–25 Fishing communities are often closely proximate to industrial point sources of air-, water- and soil-borne pollution or may receive discharges and effluent from upstream sources. Legacy pollutants from poorly regulated waste streams, active disposal and storage sites, and orphaned or improvised dumps are also a constant in some of these communities, particularly in south Louisiana.26,27 Because the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act essentially exempts energy industry exploration and production waste from regulations applied to other hazardous materials, some fishing-based communities are potentially exposed, and exposure-related health effects are usually neither monitored individually, nor tracked epidemi- ologically.28–30 Finally, access to healthcare in this region could best be characterized as spotty, especially among low-income or seasonal workers, and the percentage of uninsured and underinsured is relatively high. And regional access to occupational medicine specialists for private patients is especially limit-ed.23,27,31 Simply put, the fishermen and their communities had so many urgent issues directly linked to the DWH spill and preexisting cumulative risk factors to address that outreach staff needed to make a strong introductory case for the community benefits of participation in a proposed multiyear scientific study to garner significant support.

Finally, fishermen are fiercely independent with very few professional organizations at the grassroots level. And they often share a dual seasonal identity as fishermen and workers in many facets of the energy industry (such as tug captains, equipment haulers, rig personnel), so this disaster curtailed all of their usual work opportunities. State and federal fishing waters were closed at what would have been the opening of brown shrimp season, and the federal government declared a moratorium on energy exploration in the gulf1,32 (see Reference Supplement 2: Timelines and Geography of Fishing Waters Closures and Federal Moratorium on Drilling/Exploration).

Project field staff informally approached the Louisiana Oysterman’s Association, the Louisiana Shrimp Association, and the United Commercial Fishermen’s Association to profile the project during its early stages. While none of these organizations expressed strong negative opinions about the project, they were dubious about how the seafood industry, and individual fishermen seeking damage compensation from the responsible parties, would actually benefit from documenting levels of PAH in their catch. This mirrored a similar ambivalence in communities. Some fishermen objected strongly to the project, voicing a position that any testing that yields nondetects or minimal levels of target PAH might hurt their prospects in the damage recovery process. On the other hand, finding detectable amounts—even if below federal levels of concern—might damage regional/national perception of the Gulf brand and freeze out prospects for marketing their catch.1 Contention was particularly acute over sampling in Barataria Bay—formerly one of the region’s most productive fisheries but heavily oiled while the blown wellhead was still uncapped. CODC personnel opted not to pursue systematic sampling in any such contested area to prevent further polarization within the ranks of fishermen and their communities. During these sensitive early stages of the project, community hub coordinators served as connective tissue and multidirectional information conduits. The hubs answered questions from the community, conveyed concerns, and recruited several fishermen as potential citizen field science seafood samplers process in all three states.25,b,c

The Vietnamese-American fishermen along the Mississippi coast posed yet another set of challenges due to linguistic and cultural marginalization. Most of the smaller scale fishermen are older—ages of project participants ranged from forty-two to seventy-nine years—and their preferred language is Vietnamese. This made on-site translation essential when CODC staff interacted with fishermen. The storm surge from Hurricane Katrina did immense damage to the Mississippi coast, and issues of economic hardship and dislocation from former housing still loom large among members of this group. Their community has a more circumscribed range of exchanges with other groups in the region, and the efforts of the community hub coordinator were absolutely essential in developing a network of available small-scale commercial fishermen and translators. The project was not able to connect effectively with the Vietnamese fleet of larger scale commercial freezer-boats because their extended time at sea (five to eight weeks) made logistics of communications, storage, and sample retrieval too difficult.

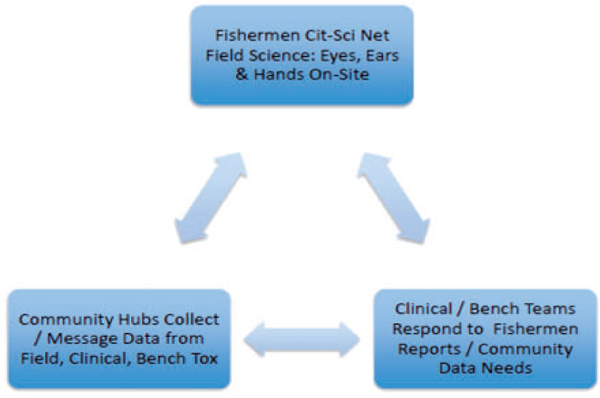

Despite various obstacles beyond the project’s direct control, support for Fishermen’s Citizen Science Network remained solid. The science team, CODC, and community hub coordinators acknowledged that the project needed the professional fishing skills of area fishermen to succeed. Their direct involvement allowed for a sufficiently wide range of geographical flexibility in responding to changes in the ecosystem due to oil plume migration, or changes in behavior, reproductive activity, and herd health in the target species. Their local knowledge of the coast provided necessary expertise in developing the project’s matrix of sampling areas and their familiarity with the various species streamlined the onboard sampling process. Fishermen still play an iconic role in the traditional life of gulf coastal communities, and their support for GC-HARMS was an essential factor in overcoming initial skepticism toward working with outside institutions.33 Their livelihoods depend directly on the health and sustainability of the food web and the quality of their catch, so their level of commitment was strongly personal and steady. Network fishermen were essential actors in achieving the environmental health literacy outcomes of GC-HARMS as peer-to-peer risk communicators (See Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Crucial role of fishermen in GC-HARMS CBPR collaboration: observation, field sampling, flow of information.

(Fishermen Citizen Science Network serves integral role linking community hubs and clinical/ bench science/CODC teams to maintain iterative, multidirectional communication relationship.)

Benefits of Hub Coordinator/Fishermen’s Citizen Science Network Collaboration

The benefits of close collaboration of the Epidemiology/Toxicology science teams with a Citizen Science Network of area fishermen and GC-HARMS hub coordinators from local community-based organizations cover a wide range of project essentials from ease of data collection and documentation, to informed reportage of local events and perceptions, and dissemination of information and risk messages from the project on a granular level in the direct parlance of place. The overarching—though often aspirational—outreach goal informed by CBPR practice values is always that scientific process and research agendas and the lived reality of collaborating communities find a good and useful symbiosis.5–9

During the early stages of the emergency response to the DWH catastrophe and well into the initial year of GC-HARMS projects, community hubs and project fishermen offered invaluable access to anecdotal evidence of the environmental health impacts on coastal residents. Fishermen maintained close contact reporting back to hub coordinators and CODC field staff on specific, possibly exposure-related health conditions experienced by themselves, family members, and neighbors in the various coastal communities. The multiple rounds of Fishermen’s Forums were invaluable conduits for information specific to unique locales; this is especially important in a project that comprises several governmental and regulatory environments, extensive geography and cultural diversity. CODC staff became aware of acute, short-term respiratory problems and more chronic pediatric conditions resembling asthma in the tiny fishing villages of Buras, Pointe à La Hache and Grand Bayou, LA (Plaquemines Parish); severe eye irritation from contact exposure to gulf water in Coden, AL; and the intermittent presence of strong crude oil-related odors with accompanying short-term neurological effects in lower Terrebonne and Lafourche Parishes by listening to fishermen close to the source of the problem.34,35,c

Anecdotal information on employment patterns, access to healthcare, and grassroots economic hardships stemming from the DWH economic turndown, etc. also helped extend the scope of epidemiological research—most specifically with respect to design of the project’s survey instrument and framing potential questions to inform data analysis. This grassroots perspective widened the project’s window on health disparities, regional cumulative risk burdens, socioeconomic impacts of the DWH, and ways in which Gulf communities may strengthen and maintain resilience. The community hubs and Citizen Science Network leveraged regional and community-specific channels of communication to “carry the news” of local crisis forums, events, symposia, and the ever- changing state of coalition advocacy along the Gulf coast. This connectivity kept researchers throughout the consortium in close touch with the feelings and beliefs of affected residents.33 Culturally nuanced reportage kept research planning grounded and was critical to framing realistic perspectives on community-level economic impacts of the spill in terms of traditional seafood consumption patterns. Information filtered through the network helped clarify variables in regional risk perceptions and tracked changes as state-federal restoration activities commenced and fishing closures as well as the moratorium on new energy exploration were lifted.

Throughout GC-HARMS, these networks stayed close to the local pulse and helped researchers and CODC navigate the complex and changing regional social dynamic within which the project is embedded. The fishermen’s network role in communicating the final version of the project’s risk message, seafood consumption guideline, and related public health advisories on a peer-to-peer basis was an important facet of dissemination efforts in the final months of GC-HARMS.14 Community hubs deploy a variety of communication tools for greater regional penetration of these same messages, and the LEAN now hosts a permanent web-based archive—designed in a collaboration between their staff and UTMB CODC—of the project including an interactive seafood sampling map of the entire tristate matrix that enables visitors to gain specific information such as sampling activity dates, species sampled, aggregate petrogenic PAH levels/standard deviation, GPS location, and method of sampling, if available, for each sampling site on the display36 (see http://gcharms.leanweb.org/seafood-sampling-map/).

Working From a Hybrid Model of CBPR, Citizen Science, and Environmental Health Literacy: Concepts, Training, Protocols, and Techniques in GC-HARMS Citizen Science Network

Because of the frequency of industrial accidents in the Gulf, the LEAN and their science consultant, Wilma Subra, developed a process to respond to local environmental crises with rapid deployment of community education, air-water-soil sampling, analysis, and interpretive services. UTMB NIEHS Community Outreach and Engagement Core staff also had previous experience with Subra’s community-based approach when she guided a similar process to assay sediment left on Galveston Island (Galveston, TX) by storm surge from Hurricane Ike. She developed a set of EPA-approved sampling protocols, presented a citizen sampler training workshop, helped choose appropriate sampling locations on the island, accompanied the sampling crew into the field, assisted in packing/shipping collected samples to a commercial analytic lab, and coprepared an interpretation of the analytic data with UTMB toxicologist, Jonathon Ward.37 The LEAN/Subra Company process used in GC-HARMS combined presentation of relevant environmental health concepts, an overview of protocols for field collection of samples, maintenance of CoC and use of photography for documentation, and hands-on proper use of sampling and personal protective equipment.15

GC-HARMS adopted this model for use in the Mobile Bay area as a pilot project (July 2011), with the addition of some basic toxicological terms specific to the research goals of GC-HARMS. The major goals of the pilot included (a) delivery and discussion of EHL concepts germane to the DWH spill, (b) smooth integration of the sampling process into the work flow of a shrimp boat in action, and (c) postsampling preparation of shrimp, crab, and finfish samples for storage and/or shipping. While the process for oyster collection was reviewed, logistics of distance, available time, and seasonal regulations made it impossible to visit an oyster reef during the day available for the sampling session. The CODC team rolled out the curriculum in July and field-tested the sampling methodology on board a shrimp boat owned by a member of the Alabama Fisheries Cooperative. Based on debriefing with the core group from Alabama Fisheries Cooperative, GC-HARMS field staff and Subra, the curriculum was expanded to include more toxicology and marine ecology con-cepts.9,12,16 The LEAN model featured a one-month turnaround for community discussion of results from a commercial analytic lab, but this frame had to be extended to allow for considerable extra time—based on the work flow limitations of the academic gas chromatography-mass spectrometry lab and research on the unknowns in petrogenic PAH metabolomics that would ultimately impact species-specific levels of concern and risk assessment.

The Final Version of the Citizen Science Pedagogical Model Included Six Components

A—Orientation to goals of GC-HARMS: the overarching goal of the research study was synopsized: exploring DWH disaster-related health impacts and community resiliency by fostering collaboration among affected communities and science teams from four universities. Each component project of the study was summarized with a minimum of scientific jargon, and greatest emphasis was placed not only on the role of fishermen in providing seafood samples for PAH analysis through Projects 2 and 3 but also on recruitment of human subjects for surveys, physicals, and collection of specimens. This was primarily to build awareness that human subjects were also vital to the study though it was made clear that participants would be randomly selected rather than volunteers. Participants in the first study-wide meeting of GC-HARMS community hub coordinators and researchers held at UTMB in 2012 covered this same territory in more detail and participated in an interactive CBPR values and principles training workshop.5,9,38

-

B—Basic science: the environmental health education team defined petrogenic PAHs as components in the structure of crude oil and contrasted them with more commonly encountered pyrogenic PAHs. Fishermen often raised questions about possible exposure to pyrogenic PAHs by workers in the Vessels of Opportunity program developed by the responsible party. Following the same organizational pattern as the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) hazardous substance fact sheet on pyrogenic PAH (ATSDR ToxFAQs™), fishermen were introduced to concepts of PAH fate and transport, and exposure pathways, with particular emphasis on ingestion of contaminated seafood and direct contact with crude oil, weathered tar mats, or tar balls.39,40 Potential health effects were framed in terms of individual dose responses based on frequency, magnitude, duration of the exposure and timing (age-framed in terms of biological development) or special vulnerability factors such as pregnancy, nursing mother, and preexisting health conditions.41 Discussions related bioavailability to ease with which PAHs might be ingested by marine life and bioaccumulation described as the process by which toxic substances were stored in body fat or organs. Describing the metabolic transformation of PAH through a series of related metabolites of varying toxicity proved difficult: the process was often described as “clearing” and the metabolites as “fingerprints,” or evidence (biomarkers) of initial exposure to petrogenic PAHs in crude oil.41 This educational process was kept informally conversational and organized around venues familiar to the fishermen (See Figure 5). Concepts were functionally linked to realities of life on the water, the sustainable health of gulf fisheries, and establishing a guideline for safe levels of seafood consumption.42

Because many concepts did not translate well from English to Vietnamese, the environmental health education piece of the training process among Vietnamese fishermen was framed as analogies using ideas such as bioavailability, bioaccumulation, dose-response parameters, and health risks and delivered through a translator. Because of an observed lack of familiarity with the relationship between heavy metal bioaccumulation in the food web (most specifically, methyl mercury) and the special vulnerabilities of pregnant females, fetuses, and children in early developmental periods, and heavy rates of higher level predator finfish consumption within this community, special emphasis was placed on communicating these facts to collaborating fishermen during the training process, even though these substances were not included in the suite of petrogenic PAH targeted in the GC-HARMS assays. Working in the Vietnamese community underscored the value of assessing levels of environmental health literacy prior to designing a training approach.

-

C—Methods, tools, techniques (field sampling): instruction in field collection techniques occurred in a wide variety of venues. A series of large group Fishermen’s Forums were initially produced as community events in Montegut, LA; Gulfport and Biloxi, MS; and Coden, AL to promote awareness of the project goals and recruit fishermen as network participants. These events were coproduced by the local community hub organization in collaboration with the lead institution (UTMB) and included an overview of preliminary data from the pilot and other, published scientific findings framing the DWH oil spill impacts. Community hub organizations and CODC staff found these mass events, while useful as general information portals and capacity-building vehicles, were less effective in delivering curricular components to specific fishermen than smaller, more focused sessions.

Wilma and CODC staff trimmed the material and focused solely on communicating toxicological constructs associated with the project, EPA-approved collection/storage protocols, and demonstrating proper use of basic equipment. Content educators walked each participant through the less than intuitive documentation process, providing assistance when necessary (See Figure 6).15

D—Methods, tools, techniques (lab/clinical): the GC-HARMS integration meeting in 2012 also included a tour of the laboratory facility used to assay marine life tissues and human specimens. Project 2 staff invited hub coordinators and community fishermen into their laboratories and explained their work flow, specifically mapping how samples taken in the field would be cataloged and stored prior to assay. They clarified that their initial task involved developing and perfecting a methodology for the assays based on validated practice standards before they actually began work on field samples and developed a data base. Inside the lab, staff introduced hub coordinators and fishermen to the −80 freezers where samples were banked and to the gas chromatography-mass spectrometry instruments where PAH assays would be performed.

E—Project responsibilities: presampling discussions focused most intently on the importance of adhering to collection protocols to insure the credibility of samples. Everyone understood that samples without a CoC trail or lacking a field report with vital information like GPS coordinates and a discrete sample number were of no value, and there were very few fatal errors in this process. However, wrapping, labeling, shipping, and storage of samples still varied among fishermen, and CODC staff often had to transcribe information from field reports onto labels for freezer storage. All fishermen were provided with stipends, provided they followed the CoC process and their samples could be entered into the data base.

F—Understanding how scientific standards and methodology impact the time-line for reporting and discussing results of the project: during the early stages of GC-HARMS, the analytic science team evaluated various protocols in order to adopt the best-suited procedures for the measurement of petrogenic PAHs in seafood. This process caused a significant delay in the actual analysis of seafood samples.43 Because project fishermen had no previous experience with the processes employed in the gas chromatography-mass spectrometry work flow, it was necessary to explain the timeline for steps taken by lab staff to develop standard operating procedures so that analytic work on samples from a number of different species could proceed efficiently and with confidence in the results. Unfortunately, this explanation came after the project was well underway, in response to questions from participating fishermen concerned about the quality of their catch and uncomfortable with the time lapse between sampling and feedback. This process was repeated when the turnaround time on actual PAH data seemed overly extended, prompting additional questions. Project principal investigators and CODC personnel scheduled on-site visits to community hubs and an annual regional CODC gathering to present results of assays and discuss progress on establishing the toxicity of detected compounds; to consider the varieties, relative toxicities, and pathways of metabolites produced during the process of “clearing” PAH from the human body; and to explain how experimentally derived levels of concern were being used to develop guidelines for safe consumption of seafood products. Throughout the project time span, balancing the urgent needs of communities coping with an environmental health crisis and its social/economic dimensions with the painstaking processes of laboratory assay and data analysis created a complex and nuanced dynamic.44

Figure 5.

GC-HARMS citizen science educational outreach leveraged use of nontraditional venues to bring process to network fishermen.

Louisiana Environmental Action Network Science Consultant, Wilma Subra, presents overview of environmental health concepts and sampling protocols to members of the Alabama Fisheries Cooperative Onboard Captain Sidney Schwartz’s shrimp boat prior to fishing (Dog River, Alabama, 2011).

Figure 6.

Louisiana Environmental Action Network community science consultant, Wilma Subra, details seafood sampling protocols with fisherman volunteers.

(Use of informal venues specific to fishermen and their interests allowed for undivided focus on components of citizen science curriculum and field collection protocols. Louisiana Environmental Action Network, Bayou Inter-Faith Shared Community Organizing, GC- HARMS CODC; Galliano, LA, 2012.)

Evaluating the Process Outcomes of the GC-HARMS Fishermen’s Citizen Science Network

Throughout the course of the project’s early engagement phase, 203 fishermen, their families, and various community officials attended Fishermen’s Forums in targeted communities within the GC-HARMS catchment area: five southern parishes in coastal Louisiana; Gulfport and Biloxi, MS; and Coden/Bayou La Batre, AL. Out of this initial response, fifty-two commercial/subsistence or recreational fishermen agreed to participate as samplers. Because Galveston Bay samples were used as a control, the CODC personally recruited two additional participants in the Galveston area but without staging a Fishermen’s Forum. Citizen scientist fishermen successfully processed multiple organisms providing scientifically valid samples from 208 sample sites during the network’s active period (December 2011-January 2014)14 (see Reference Supplement 3: Responses to Fishermen’s Observation Prompts).

There was intense discussion on how the spill and resulting oil plume may have impacted water quality and the integrity of marshland, as well as the size and geographical distribution of various common marine species, the relationship of tidal flow to oiling on oyster reefs, and, invariably, exposure-based human health impacts. Responses to these prompts and suggestions from individual fishermen were instrumental in developing a targeted sampling matrix that covered as many oil-impacted areas as possible. This bidirectional framework allowed for the same fruitful mix of local knowledge and specialized expertise described by Fischer as “participatory praxis” in his analysis of community resource mapping and popular epidemiology in the developing world, and the United States.45 Our ongoing conversations with fishermen around these themes during the sampling program allowed the science team to stay current with community risk perception, respond to ongoing changes in the physical environment, and address other emerging impacts. When conversations on health risk happened at work sites, nonparticipating fishermen often became involved through mere proximity, but often, as the project progressed, because they were interested in the risk message and concerned for their families’ health. This peer-to-peer risk communication in situ reached many working fishermen who never attended any of the formal Fishermen’s Forums.14

CODC personnel formally queried the community hub coordinators at the project’s halfway point (2013) regarding efficacy and challenges related to the Fishermen’s Citizen Science Network from the perspective of on-site managers. Results of this qualitative, dialogic process indicated the following: (a) In terms of an approach to this type of research—community engaged, with important scientific unknowns, during a period of social turmoil stemming from the environmental health impacts under investigation, involving disparate communities over a large geographic expanse—CBPR was a wise choice because of its emphasis on transparency, direct involvement of community partners in framing/implementing the science, and overcoming initial lack of trust in outside institutions due to mishandling of the crisis in its early stages.16,33 (b) The hub coordinators all agreed that engaging regional fishermen in the Citizen Science Network enhanced the value of the project because of their expertise on the water and the importance of their work in the coastal economy. They were considered exceptionally motivated stakeholders in the process and out-comes, and their opinions well respected in their communities.33 (c) Exposure to the process increased functional (though not necessarily theoretical) environmental health literacy of the fishermen and the use of informal, work-related venues for instruction made the process more meaningful46,47 (see Reference Supplement 4: Framework for Evaluation of Citizen Science Impacts Using Criteria Grounded in Environmental Health Literacy).

In a less positive vein, some of the coordinators observed that the lack of rapid turnaround with site-specific results from PAH analysis caused discontent and increased skepticism within the network. A widely observed decrease in productivity within the fishery caused many smaller fishing operations to curtail or attenuate commercial fishing; this, in turn, made it more difficult for hub coordinators to keep fishermen committed to the project.48,49 Additionally, some of the fishermen perceived both the protocol training and sampling as one-time events, not part of a process. Last, since recreational (not commercial) fishermen were sources for finfish samples, on a few occasions, hub coordinators were left to clean, bag, and label samples because these fishermen had no interest in that part of the process.

Summary

In conclusion, participation in the Fishermen’s Citizen Science Fishermen’s Network training process certainly had a positive impact on the capacity of network fishermen to understand and follow sample collection protocols and seemed to increase their general awareness of environmental health. Though results varied individually, this growth was evidenced in their capacity for independent sampling and sample preparation, their astute monitoring of the state of the ecosystem during the project, and their conversational understanding of terms like PAH, exposure pathways, and the general concept of dose-response parameters. When network fishermen, and other community participants learned that their area lacks access to specialists in environmental health whose practices are open to the general public rather than restricted to workers of contracted industrial clients, they felt newly empowered to question diagnoses of health impacts—possibly related to oil or oil/dispersant exposures—in cases where health practitioners did not integrate environmental health exposures into their diagnostic algo-rithms.31,50 In addition, exposure to the training process and managing logistics for seafood sampling seemed to increase the self-reported overall environmental health literacy of the community hub coordinators.

Supplementary Material

Figure 4.

Environmental health literacy conceptual goals of GC-HARMS Citizen Science Network goals for fishermen, community hub coordinators, and research/CODC teams. (GC-HARMS environmental health literacy framework accommodates a range of project environmental health concepts and competencies based on interests, needs, and potential utility.)

CoC = chain of custody; CODC = Community Outreach and Dissemination Core; PAH = polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This project was conducted through the Community Engagement Core (CEC) at the Center of Excellence in Environmental Toxicology at the Perlman School of Medicine of the University of Pennsylvania, supported in part by P30-ES013508 from the NIEHS and through the Center for Environmental Toxicology and the Sealy Center for Environmental Health and Medicine at the UTMB, funded in part by P30-ES006676 and U19-ES020676 from the NIEHS. The findings do not represent the official opinion or polices of the NIEHS or NIH.

Author Biographies

Academic Authors

John Sullivan served as liaison with community hub coordinators for the GCHARMS CODC. He helped create and manage activities of the Fishermen’s Citizen Science Network and oversaw operations of the sampling process in the field. Sullivan has represented the project at NIEHS grantees meetings, organized annual CODC meetings within GC-HARMS Network, and presented findings/outcomes at successive American Public Health Association meetings during the project. Sullivan previously served as director of the Public Forum & Toxics Assistance Division of the Community Outreach and Engagement Core of the NIEHS P30 Center in Environmental Toxicology at UTMB (Galveston, TX). He is a practitioner of Augusto Boal’s Theatre of the Oppressed within a CBPR context and previously served as a guest coeditor with Eduardo Siqueira (MD, ScD) for a New Solutions special feature on Popular Arts & Education in CBPR (2009).

Sharon Croisant, MS, PhD, CEC Director, is an associate professor in the UTMB Department of Preventive Medicine and Community Health. An investigator in both the Center in Environmental Toxicology and the Institute for Translational Sciences, she serves as director ofCommunity Engagement for both. She has a strong record of leading community engagement efforts in environmental health, having assumed the role of CEC Director in 2009, after serving as director of Children’s Asthma and Lead Outreach since 2001. A major focus of her career has centered on translational research, that is, building interfaces between and among environmental research, education, and community health, especially through a CBPR approach. She has established long-standing, ongoing collaborative relationships with community stakeholders across the Gulf Coast with a vested interest in using research findings to direct community-based intervention and outreach activities. Croisant was principal investigator on Project 1 (Community Health Assessment) and directed the project’s CODC during the course of GC-HARMS.

Marilyn Howarth is an occupational and environmental medicine physician. she directs the CEC (Community Engagement Core) in the Center of Excellence in Environmental Toxicoloy at the University of Pennsylvania. Her work through the center includes community-engaged research and outreach aimed at improving environmental health and policy and environmental health literacy. Howarth was a crucial member of the GC-HARMS risk communication team.

Gilbert T. Rowe, a regents’ professor at the Galveston branch campus of Texas A&M University in College Station, investigates the diversity and dynamics of communities of organisms in the marine habitats worldwide. In GC-HARMS, he constructed simulations of the cycling and fates of PAH within the food webs affected by the spilled oil. He also developed a set of talking points and openended questions for use in project Fishermen’s Forums to elicit grassroots reportage on field conditions that helped design a targeted matrix for sampling seafood.

Harshica Fernando received her PhD from University of Illinois at Chicago and currently serves as an assistant professor at Prairie View A & M University. During the GC-HARMS project, she performed gas chromatography–mass spectrometry analysis of seafood and human biologic samples to measure petrogenic PAH levels and document overall trends. This trend analysis played a crucial role in developing the GC-HARMS risk message.

Amanda Phillips-Savoy, MD, M PH, FAAFP, FACOEM, is a faculty member in the Lafayette Medical Program and the Department of Family Medicine at the LSUHSC-University Hospitals and Clinics. She is boarded in occupational medicine in addition to a Masters of Public Health in Occupational Medicine and is also boarded in sports medicine. Phillips’ research interests include CBPR, practice-based research networks, Lynch syndrome, sepsis, quality improvement, and resident education interventions. Phillips-Savoy served as a health consultant and advocate throughout the process, visiting with families and fielding questions about the oil spill and environmental health outcomes. She also reviewed and commented on all of the printed documentation of results and risk communication efforts regarding seafood safety.

Dan Jackson completed his doctoral research studying the molecular pharmacology and toxicology of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Jackson contributed to calculating safe seafood consumption guidelines by testing PAH extracts with the chemical activated luciferase gene expression bioassay and extrapolating cancer risk based on toxic equivalency factors. His research interests lie in understanding mechanisms of toxicity at the cell and molecular level. He is now a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Pennsylvania.

John Prochaska is a social and environmental epidemiologist with primary research interests in methods utilizing action-based and stakeholderengaged research approaches in dissemination and implementation research. His interests lie across the spectrum of environmental public health and disease prevention and include working with communities to better understand their pathogenic and salutogenic exposures. His application of qualitative and mixed-methods research, geographic information systems, systems thinking, and computer modeling methods provides a broad range of tools for understanding these issues, as well as translation of research generated through this research to a broad array of audiences. He has more than a decade of experience working with action-based and stakeholderengaged research.

Ghulam A. S. Ansari, professor in the Departments of Pathology and Biochemistry & Molecular Biology has a successful research career in toxicology. He has been continuously funded by agencies such as the NIEHS, EPA, National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health, World Health Organization, and National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. In this project, his expertise in analytical toxicology was utilized to analyze marine and human plasma samples for petrogenic PAH.

Trevor M. Penning, director of Center of Excellence in Environmental Toxicology at the University of Pennsylvania is an expert in PAH metabolism and bioactivation. He is a Fellow of the American Chemical Society and senior editor for Cancer Research in Population Science and Prevention. He is one of the most cited authors in the PAH literature and has published more than 260 peer-reviewed articles. Center of Excellence in Environmental Toxicology is a P30 Environmental Health Sciences Core Center funded by NIEHS.

Cornelis Elferink obtained his PhD in Biochemistry from the University of Adelaide, Australia, and conducted a Postdoctoral Fellowship at Stanford University before initially joining the faculty at Wayne State University and subsequently the Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology at the UTMB where he is currently professor and the Mary Gibbs Jones Distinguished Chair in Environmental Toxicology, and the director of the Sealy Center for Environmental Health and Medicine. Elferink’s long-term basic science research objective is to understand the role of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor in liver homeostasis and liver regeneration following hepatic injury. He also headed the collaborative research team linking scientists from several academic institutions with Gulf of Mexico stakeholder communities impacted by the Deepwater Horizon disaster to examine the human health consequences of the oil spill using CBPR strategies.

Footnotes

Throughout this paper, the terms Macondo oil spill, Deepwater Horizon oil spill, and British Petroleum oil spill are used interchangeably to refer to the same catastrophic explosion, fire, and consequent oil spill which killed 11 oil platform workers, injured 17 others, and caused a long-term environmental catastrophe with wide-ranging negative outcomes for U.S. Gulf Coast communities. The terms fishermen, fishers, and fisherfolk are also equivalent and used interchangeably to refer to both an occupational group and a traditional culture informed by fishing and life on the water. In deference to the diversity of cultural backgrounds, gender inclusion and language usage (parlance of place) within GC-HARMS we have opted to use all of these terms.

Louisiana Environmental Action Network’s anecdotal report of ambivalence to sampling by fishermen in Lafitte/Barataria LA area. These reports were corroborated by CODC personnel through dialogue with organizers of an ad hoc fishermen’s advocacy group, “Go Fish,” in the town of Lafitte, LA, 2010–2012.

(CODC) Between 5 May 2010 and approximately October 2012, CODC personnel dialogued with community members affected by the DWH spill and aftermath in Terrebonne, Lafourche, Plaquemines, St. Bernard, and Jefferson Parishes (LA); Pass Christian, Gulfport, and Biloxi (MS); and Bayou la Batre, Coden, and Theodore (AL)—both formally through Fishermen’s Forums and informally in interviews/conversations. Health conditions that seemed to coincide with the period of the spill extending beyond the official completion of the abatement response were constant topics. This emphasis on human health impacts was particularly evident in Buras, LA (Plaquemines Parish) and Coden, AL (Mobile Co.).

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Community Partner Authors

Louisiana Environmental Action Network (LEAN): Situated in Baton Rouge LA, the LEAN is a community-based not-for-profit organization that has been working since 1986 to resolve the unique environmental struggles present in Louisiana. Through education, empowerment, advocacy, and support, LEAN provides the necessary tools and services to individuals and communities facing environmental problems that often threaten their health, safety, and quality of life. LEAN served as a coordinating hub for the GC-HARMS projects, recruiting fishermen for training as citizen scientists/seafood samplers, convening annual regional community hub meetings during the course of the project, posting project updates on their web site, and finally, creating and archiving a project web-tool, the GC-HARMS Seafood-Sampling Map (http://gcharms.leanweb.org/seafood-sampling-map/) that displays areas where samples were taken, PAH measurements from samples, and an interpretive guide that explains the science behind this phase of the project and links with more in-depth information for web visitors who want to know more. For in-depth information about LEAN, visit: https://leanweb.org.

United Houma Nation:

Based in Houma LA, the UHN is a state-recognized tribe of approximately 17,000 members residing within a six-parish (county) service area encompassing 4570 square miles. The six parishes, Terrebonne, Lafourche, Jefferson, St. Mary, St. Bernard, and Plaquemines parishes, are located along the southeastern coast of Louisiana. Within this area, distinct tribal communities are situated among the interwoven bayous and canals where Houmas traditionally earned a living. Although by land and road these communities are distant, they were historically very close by water. The Houma Nation faces some of the most challenging threats to their culture and way of life due to climate change. Severe ongoing coastal erosion, deterioration of marshland due to energy industry access canals and infrastructure, alarming sea level rise, and vulnerability to increasingly stronger Gulf storms in areas with a high density of energy industry transport, refining, and storage infrastructure loom large in their future as a people. During GC-HARMS, the UHN served as a community hub for the Fishermen’s Citizen Science Network within their catchment parishes while building and maintaining a cohort for the project’s community longitudinal health study. For more information, see: http://www.unitedhoumanation.org.

Bayou Interfaith Shared Community Organizing (BISCO):

From its headquarters in Thibodaux, LA, BISCO builds the voice and power of local residents to address the most pressing issues facing their communities. The disasters of the last decade—Hurricanes Katrina and Rita in 2005, Hurricanes Gustav and Ike in 2008, the BP oil drilling disaster in 2010, and the River Flood of 2011—have severely impacted Terrebonne and Lafourche parishes in BISCO’s outreach focus area. The fallout from these disasters may seem local but are important regionally and nationally. BISCO looks forward to a better, safer, more prosperous future; we teach our community leaders how to advocate for issues that need to be addressed. During the GC-HARMS project, BISCO served as a community information hub that provided updates on project findings, helped circulate the project seafood consumption risk message at the grassroots level, and convened meetings that gave local/regional public health officials an opportunity to talk directly to GC-HARMS science and outreach personnel about communicating the project risk message to local communities. For more information, visit BISCO at: http://bisco-la.org/home/about_bisco.

Dustin Nguyen-Vietnamese Community Partner:

From his base in D’Iberville, MS, Mr. Nguyen serves Vietnamese-Americans living in many communities along the Mississippi coast. Mr. Nguyen is an insurance professional who, in addition to offering translation services for monolingual Vietnamese-speaking clients, often serves as a navigator for members of his community attempting to access healthcare, interpret regulations and enrollment protocols related to the Affordable Care Act, or purchase policies that suit their needs. Mr. Nguyen organized and maintained a cohort during his community’s longitudinal health study. Through his business insuring commercial fishing vessels, he was able to network with fishermen and reinforce risk communication efforts of the GCHARMS CODC.

Center for Environmental & Economic Justice (CEEJ):

Rooted in Biloxi, MS, but playing an important role in regional Environmental Justice issues, CEEJ was founded in 1989 by Bishop James L. Black. CEEJ is the oldest continuous existing 501(c)(3) (except NAACP) minority-led social justice organization in the area. CEEJ’s objectives include organizing grassroot community people and other community-based organizations to affect socioeconomic development issues and environmental justice concerns that are germane to people of color and other impacted ethnicities. Also, CEEJ is working to eliminate environmental health hazards and promote economic sustainability through community education, hazard control training, and by engaging in social justice issues that affect Afro-Americans and other impacted ethnicities in Mississippi. CEEJ managed and maintained a cohort during the longitudinal community public health study, organized a fishermen recruitment and training session, and convened a succession of community forums disseminating seafood consumption risk guidelines developed during the project. For additional information on CEEJ, please visit: http://www.centerforenvironmental.org/about.html.

Alabama Fisheries Cooperative (AFC):

Operating from the Coastal Response Center in Coden, AL, AFC worked with shrimp and fin fishermen, crabbers, and oystermen along the Alabama coast with primary emphasis on Mobile Bay and proximate estuarial systems. During the course of the GC-HARMS project, AFC served as a community seafood sampling hub with the Fishermen’s Citizen Science Network project while maintaining a major profile as active, articulate advocates for truth-telling: in terms of the actual health risks posed by petrogenic PAH (and other oil and dispersant components). AFC also worked extensively with the Federation of Southern Cooperatives on an ongoing project to create a functional cooperative structure for fishermen and processors in coastal Alabama. For more information on the activities of the Alabama Fisheries Cooperative, visit https://alafishcoop.wordpress.com.

Project Community Scientist Author:

Wilma Subra (Subra Company): From her base in New Iberia, LA, Wilma Subra provides customized, on-site citizen science sampling training using EPA CoCapproved sample collection protocols, data analysis, and ultimately helps communities refine their environmental public health advocacy with clearly defined goals and scientifically credible evidence. Nationally acclaimed as a MacArthur Prize-winning environmental public health scientist, Ms. Subra has worked with communities on a wide range of environmental public health issues such as fracking emissions-produced water impacts on groundwater, emissions into fence line communities from refining and chemical production facilities, hazardous waste storage and treatment, municipal water treatment facilities, etc. She served as project community scientist during GC-HARMS providing sample preparation training and environmental health literacy instruction for fishermen in the Citizen Science Network and was a valuable member of the GC-HARMS risk communication team, working on-site from Coden, AL to Dulac, LA during the project.

References

- 1.Juhasz A Black tide: The devastating impact of the BP oil spill. Somerset, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.NIEHS RFA. Deepwater Horizon disaster research consortia: health impacts and community resiliency (U19), https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/rfa-files/RFA-ES-11-006.html (accessed May 2018).

- 3.GC-HARMS overview: Gulf Coast Health Alliance: health Risks related to the Macondo Spill (GC-HARMS; ), http://www.utmb.edu/GCHARMS/ (accessed January 2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.NIEHS. Advancing environmental justice; communities organized against asthma & lead. Research Triangle Park, NC: NIEHS, 2015, pp. 18, 39–40, https://www.mehs.nih.gov/research/supported/assets/docs//a_c/advancing_environmental_justice_508.pdf (accessed January 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCloskey DJ, Aguilar-Gaxiola S and Michener JL. Principles of community engagement (NIH Publication: #11–7782; Developed by U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, Clinical & Translational Science Awards). 2nd ed. Washington, DC: U. S. Government Printing Office, 2011, pp. 43–55, 107–149. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kellogg WK. An effective approach to understanding communities. Battle Creek, MI: WK Kellogg Foundation, https://www.wkkf.org/news-and-media/article/2009/01/an-effective-approach-to-understanding-communities (accessed May 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gills D. Unequal and uneven: critical aspects of community - University partnership. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association Press, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’Fallon L and Dearry A. Community-based participatory research as a tool to advance environmental health sciences. Environ Health Perspect 2002; 110(Supplement 2): 155–159, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1241159/ (accessed May 2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Minkler M and Wallerstein N. Introduction to community based participatory research In: Minkler M and Wallerstein N (eds) Community based participatory research for health. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2003, pp. 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katz DL. Representing your community in community-based participatory research: differences made and measured. Prev Chron Dis 2004; 1: A12, http://www.cdc.gov/ped/issues/2004/jan/03_0024.htm (accessed May 2018). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prakash S. Power, privilege and participation: meeting the challenge of equal research alliances. Race, Poverty Environ 2005; XI: 16–19, http://reimaginerpe.org/book/export/html/1 (accessed May 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sullivan J, Croisant S, Bambas-Nolen A, et al. Building community-researcher CBPR capacity and incubating partnerships through an Environmental Justice Network/Community Science Workshop: building bidirectional research capacity through access to knowledge and skills. Living Knowl Int J Community Based Res 2012; 10: 12–14, http://www.livingknowledge.org/livingknowledge/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/LK10-Journal-May12.pdf (accessed May 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen P, Diaz N and Rosenthal M. Dissemination of results in community-based participatory research. Am J Prev Med 2010; 28: 372–378, http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0749379710004083 (accessed May 2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sullivan J, Croisant S, Subra W, et al. (# 313640) Building and nurturing a citizen science network with fishermen and fishing communities post DWH oil disaster. In: Presentation abstract: American Public Health Association annual meeting, New Orleans, LA, 15–18 November 2014, https://apha.confex.com/apha/142am/webprogram/Paper313640.html (accessed May 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 15.(EPA 823-B-00-007) Guidance for assessing chemical contaminant data for use in fish advisories, http://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2015-01/documents/fish-volume1.pdf (2000, accessed May 2018).

- 16.Leung-Rubin C, Sprague-Martinez L, Chu J, et al. Community-engaged pedagogy: a strengths-based approach to involving diverse stakeholders in research partnerships. Prog Community Health Partnersh 2012; 6: 481–490, http://muse.jhu.edu/login?auth=0&type=summary&url=/joumals/progress_in_community_health_ partnerships_research_education_and_action/v006/6.4.rubin.html (accessed May 2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Golke J, Doke D, Tipre M, et al. A review of seafood safety after the Deepwater Horizon blowout. Environ Health Perspect 2011; 119: 1062–1069, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3237364/ (accessed May 2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rotkin-Ellman M, Wong K and Solomon G. Seafood contamination after the BP gulf oil spill and risks to vulnerable populations: a critique of the FDA risk assessment. Environ Health Perspect 2012; 120: 157–161, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3279457/ (2011, accessed May 2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wallerstein N and Duran B. The conceptual, historical and practice roots of community-based participatory research and related participatory traditions In: Minkler M and Wallerstein N (eds) Community based participatory research for health. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2003, pp. 27–52. [Google Scholar]

- 20.EPA: BP response to monitoring and assessment directive. Archived document, https://archive.epa.gov/emergenvcy/bpspill/web/pdf/5-21bp-response.pdf (accessed August 2018).

- 21.Mowbray R Participants in vessels of opportunity program can pursue damage claims, BP says, www.nola.com/news/gulf-oilspill/index.ssf/2011/10/participants_in_vessels_of_opportunity (accessed May 2018).

- 22.McCormick S After the cap: risk assessment, citizen science, and disaster recovery. Ecol Soc 2012; 17: 31, https://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol17/iss4/art31/ (accessed 14 August 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 23.AEHR: Advocates for Environmental Human Rights, Gulf States Human Rights Working Group. The human rights crisis in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina (Submitted to the United Nations Universal Periodic Review/9th Session on the Working Group of the UPR Human Rights Council, 22 November 22 – 3 December 2010), http://www.ehumanrights.org/docs/AEHR-GSHRWG-Katrina-Aftermath-Joint-Report-USA.pdf (accessed March 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morse R Environmental justice through the eye of Hurricane Katrina. Washington, DC: Health Policy Institute, Joint Center for Political & Economic Studies, 2008, https://web.stanford.edu/group/scspi/_media/pdf/key_issues/Environment_policy.pdf (accessed May 2018). [Google Scholar]