Abstract

We design, develop, and disseminate a ‘virtual population’ of five realistic computational models of deep brain stimulation (DBS) patients for electromagnetic (EM) analysis. We found five DBS patients in our institution’ research patient database who received high quality post-DBS surgery computer tomography (CT) examinations of the head and neck. Three patients have a single implanted pulse generator (IPG) and the two others have two IPGs (one for each lead). Moreover, one patient has two abandoned leads on each side of the head. For each patient, we combined the head and neck volumes into a ‘virtual CT’, from which we extracted the full-length DBS path including the IPG, extension cables, and leads. We corrected topology errors in this path, such as self-intersections, using a previously published optimization procedure. We segmented the virtual CT volume into bones, internal air, and soft tissue classes and created two-manifold, watertight surface meshes of these distributions. In addition, we added a segmented model of the brain (grey matter, white matter, eyes and cerebrospinal fluid) to one of the model (nickname Freddie) that was derived from a T1-weighted MR image obtained prior to the DBS implantation. We simulated the EM fields and specific absorption rate (SAR) induced at 3 Tesla by a quadrature birdcage body coil in each of the five patient models using a co-simulation strategy. We found that inter-subject peak SAR variability across models was independent of the target averaging mass and equal to ~45%. In our simulations of the full brain segmentation and six simplified versions of the Freddie model, the error associated with incorrect dielectric property assignment around the DBS electrodes was greater than the error associated with modeling the whole model as a single tissue class. Our DBS patient models are freely available on our lab website (Webpage of the Martinos Center Phantom Resource 2018 https://phantoms.martinos.org/Main_Page).

Keywords: MRI, deep brain stimulation, body models, safety

Introduction

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) is a well-established treatment for movement disorders (Vidailhet et al 2005, Deuschl et al 2006, Weaver et al 2009). It has been proposed as a treatment for psychiatric disorders (Mayberg et al 2005, Greenberg et al 2006, Schlaepfer et al 2007, Malone et al 2009, Bewernick et al 2010, Denys et al 2010, Huff et al 2010, Puigdemont et al 2011) but the limited current understanding of the interactions between the brain neural networks and the DBS implant is slowing the progress of research and the translation to clinical use for this class of disorders (McIntyre et al 2004, Widge and Dougherty 2015, Widge et al 2015, Herrington et al 2016). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), especially functional MRI (fMRI), is an ideal modality to systematically map in vivo the functional networks changes caused by the DBS therapy. However, the use of MRI for DBS patients is limited because of possible safety risks, including radio-frequency (RF) heating of tissues at the lead tip (Henderson et al 2005). Current manufacturer labeling only allows MRI exam for DBS patients at 1.5 T under strict RF power constraints, limiting B+ and specific absorption rate (SAR) (Medtronics 2015). It would be beneficial to expand MRI scanning of DBS patients to 3 T, where the contrast-to-noise ratio for BOLD imaging is ~4 times greater than at 1.5 T (Wald 2012), and greater RF power as this may allow using larger flip-angle, shorter TR and/or simultaneous multi-slice imaging (Setsompop et al 2012). However, DBS patient safety under these conditions has not been established.

Computational modeling of RF-induced heating in DBS patients during MRI has been shown to be an important tool to investigate RF safety. Commercially available finite element modeling (FEM) solvers, such as Ansys Electronics (ANSYS, Canonsburg, PA) or CST Microwave (Dassault Systemes, Paris, France), use an adaptive tetrahedral mesh that allows efficient representation of the small details of the implant as well as the much larger coil model (Kozlov and Turner 2009, Guérin et al 2014, Golestanirad et al 2016a, 2016b). However, a major bottleneck for accurate modeling of DBS patients inside the MRI RF environment is the absence of realistic DBS patient models. Most of the currently published MRI-DBS models are head-only, do not include extracranial loops (Park et al 2005, Neufeld et al 2009, Angelone et al 2010, Eryaman et al 2011, 2012, 2014, Mohsin 2011, Bonmassar et al 2013, Cabot et al 2013, Iacono et al 2013, Serano et al 2014) and do not include extension cables nor the implanted pulse generator (IPG) (Mohsin et al 2008, Neufeld et al 2009, Angelone et al 2010, Eryaman et al 2011, 2012, 2014, Mohsin 2011, Cabot et al 2013, Iacono et al 2013, Golestanirad et al 2016a, 2016b). We have shown in a previous study that these simplifications have a major impact on the predicted SAR and power absorbed at the tissue/DBS electrodes interface (Guerin et al 2018). Moreover, to our knowledge, none of these previously published models are disseminated freely to the scientific community.

In this work, we develop and disseminate five computational models of DBS patient models suitable for FEM simulation and use them to estimate the normal, inter-subject variability of peak SAR in DBS patients at 3 T. The models are based on head and neck clinical CT scans of DBS patients that were registered and stitched together. The head scans include the top of the head and the lead portion of the DBS implant, whereas the neck scans include the extension cables and the IPG, which is usually implanted in the upper thoracic cage. In addition to detailed modeling of the DBS implant path and internal components, the body of each patient was segmented into three anatomical structure classes: bone, internal air, and soft tissues. For one of the model, we added a model of the major brain tissues (grey matter, white matter, eyes and cerebrospinal fluid) in order to assess the impact of such modeling on lead-tip SAR. These models, like any computational models of patients, are necessarily simplifications: For example, the limited field-of-view of the CT scans used to create the models lead to cropping of the arms and shoulders. Despite this, we believe that these DBS computational models represent a significant improvement of model accuracy and clinical realism compared to the simplified geometries used in previous studies. The models are freely available for download (Webpage of the Martinos Center Phantom Resource 2018).

Methods

Patients selection

The institutional review board (IRB) of the Massachusetts General Hospital approved the use of previously acquired imaging data of DBS for this research project, including open dissemination of the resulting computational body models. Although there were thousands of DBS patients in the database, for most of them the sole imaging data available was a high-resolution head computed tomography (CT) scan for verification of the lead placement after the first DBS surgery. The DBS implantation procedure at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) occurs in two steps: the leads are implanted in the brain first and the IPG and extension cables are implanted about six months after when the leads are ‘set’ and the brain has recovered. The head CT volume acquired after the first surgery is not enough to build a 3D model of the entire implant as it does not cover the IPG nor the extension cables. We therefore searched the database for patients who had received neck CT examinations after the second DBS surgery for reasons that may not be related to their DBS condition. We found 107 patients matching this criterion. Among those, seven were hospital employees and were excluded as per MGH rules. Out of the 100 remaining, only 10 had received the neck CT examination after the second DBS surgery. Five patients were further selected because of the superior quality of their CT images (4 males, 1 female. Age 52 ± 27.7 years old, with minimum of 19 and maximum of 79 years old).

Virtual CT

Out of the five patients selected, only one had received a CT examination covering the entire length of the DBS implant (i.e. from the IPG to the top of the head). For the other four patients, we manually co-registered the post-DBS surgery head and neck CTs using Freeview, a visualization tool available within the open source platform FreeSurfer (Fischl 2012) (rigid registration). The alignment of the bone structures in the neck and head required specific attention: we placed the seamline between the two volumes as close to the top of the skull as possible, because bone structures and soft tissues move less between scans in this region than in the lower jaw region. The resulting stitched CT, which we call ‘virtual CT’, was down-sampled from 0.625 mm isotropic to 1 mm isotropic resolution.

Creation of the DBS implant model

The generation of the DBS model from the virtual CT volume was performed as described in our previous study (Guerin et al 2018). Briefly, the steps were as follows: (1) segmentation of the DBS cables (lead and extension cables), (2) extraction of a one-pixel wide cable representation (i.e. skeletonization), (3) reconstruction of the left and right DBS paths from the disconnected ‘skeleton’ segments, (4) smoothing and resampling, (5) analysis and topology correction of the path. The last step was implemented as an optimization procedure: The DBS path, represented as a set of linear segments, was deformed continuously to guarantee that (i) the curvature was smaller than 1/R at every point along the path and (ii) the distance between any two segments of the path was greater than 2R, where R is the DBS cable radius. The first constraint (i) guarantees that the cable turns are physical while the second constraint (ii) removes cable intersections (Guerin et al 2018). For all patients, we modeled a generic DBS implant with four 1.5 mm-long, 1.27 mm-diameter electrodes based on that mimics the Medtronic lead 3389 (Medtronic Inc. Minneapolis, MN). In order to simplify the computational model, we did not model the helicoidal structure of the implant’ internal conductor wires. Instead, we modeled four straight cables running parallel to each other and connecting each electrode to the IPG. The IPG, electrodes, conductor wires, insulator sleeve and insulator end-cap models were generated using a combination of Matlab (Mathworks, Natick MA), Sketchup (Trimble, Sunnyvale CA), and Inventor (Autodesk, San Rafael CA) tools. The internal conductor wires were connected to the IPG via 2 kΩ resistors to model the high input impedance of the device at RF frequencies. The implant IPG, internal conductors and electrodes were modeled as copper while the insulator sleeve was modeled as a generic plastic insulator (EM properties shown in table 1).

Table 1.

Dielectric properties of simulated materials at 3 Tesla (123 MHz).

| Tissue | Conductivity (S m−1) | Relative permittivity |

|---|---|---|

| Copper | 58 × 106 | 1 |

| Lead insulation | 0 | 3.4 |

| Bone | 0.07 | 14.9 |

| Internal air | 0 | 1 |

| Soft tissues (=muscle) | 0.72 | 64.3 |

| Grey matter | 0.58 | 75.7 |

| White matter | 0.34 | 53.9 |

| Average of GM and WM | 0.46 | 64.8 |

| CSF | 2.13 | 85.5 |

| Eyes | 1.50 | 69.1 |

Creation of the body surface mesh

Generation of surface mesh models was performed following the steps outlined in figures 1 and 2. The virtual CT was first segmented automatically into air, average tissue and bone classes using the expectation-maximization segmenter without atlas of 3D Slicer (Fedorov et al 2012). In the second step, small voxel islands were removed and internal air voxels (lungs, trachea, sinuses etc…) were assigned a different class index than the background. The third step was a semi-automatic cleanup of the segmented volume using tools such as thresholding, region growing, holes/gap filling, island removal, and open/close morphological operations using Simpleware ScanIP (Synopsys Inc., Mountain View CA). These were used to remove noise artefacts as well as voxels corresponding to the DBS implant, the patient table of the CT scanner as well as dental implants. The three tissue classes were then meshed using a marching cube approach and simplified in Meshlab (STEP #4).

Figure 1.

Segmentation and meshing pipeline for creation of the initial body model surface meshes (rough mesh). The output of this pipeline is a set of surface meshes representing the bone, soft tissues and internal air volumes. The meshes contain topological errors however and need to be corrected before being used in the Ansys Electronics simulation (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Pipeline for creation of the simulation-ready mesh from the rough meshes created in figure 1 (i.e. correction of topological errors). Unlike the rough meshes, the simulation-ready meshes contains non-intersecting surfaces that are 2-manifold and watertight.

The meshes obtained from the pipeline of figure 1 are not suitable for FEM simulation as they are not 2-manifold nor watertight. To correct these topological errors, we applied a separate processing pipeline summarized in figure 2 (Davids et al 2017). In short, we (i) discretized the surface mesh data back to voxel space using the surf2volz function of the iso2mesh package (Fang and Boas 2009); (ii) recomputed surface meshes using CGAL (Fabri et al 1998) resulting in non-intersecting closed surface meshes for each tissue class where all neighboring tissues align perfectly (i.e. neighboring tissues share the same faces without empty space or overlaps) and (iii) we corrected 0-manifold (i.e. edges connected to 0 face. These edges are connected to the mesh via a single vertex or point) and 1-manifold (i.e. edges connected to a single face, which indicates that the mesh has a boundary and is therefore not a closed or ‘watertight’ surface) artefacts using an in-house Matlab script. This resulted in perfectly aligned, 2-manifold, non-intersecting, watertight surface meshes for the bone, internal air and soft tissue classes. The final body models were given nicknames to protect patient confidentiality. Tissue classes were assigned dielectric properties based on the Gabriel data at 3 T (Gabriel et al 1996), which are shown in table 1. The soft tissue class was directly in contact with the electrodes. The body models are shown in figure 3.

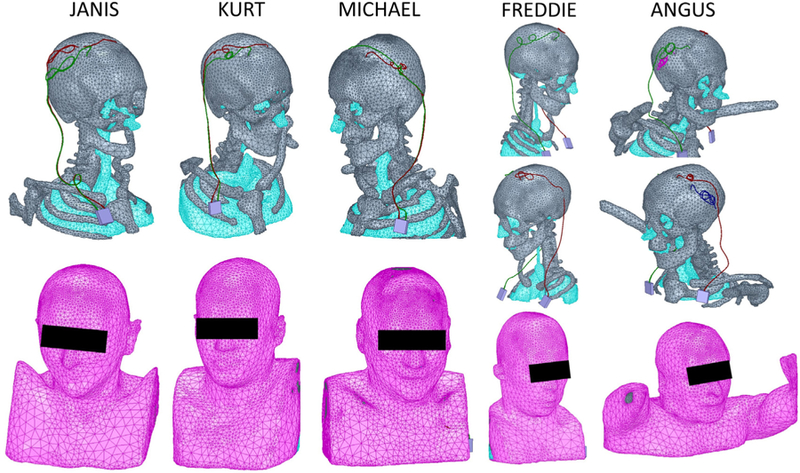

Figure 3.

Visualization of the five DBS patient models. All patients are implanted bilaterally (the right DBS lead is in green, the left in red). The model names are fictional, to protect patient confidentiality. The first three models (Janis, Kurt, Michael) have a single IPG whereas the last two (Freddie, Angus) have two (one for each DBS lead). Note that the Angus model also has two abandoned lead (pink and dark blue) that are not connected to an IPG and are therefore inactive.

Electromagnetic simulation

We simulated the electromagnetic (EM) fields induced in the five patient models by a 3 T birdcage coil (BC) shown in figure 4. The coil is a shielded high-pass body BC with 32 rungs, driven in quadrature at 123 MHz (port locations are shown in figure 4). EM simulations were performed using a co-simulation strategy using the Ansys Electronics software package (Ansys, Canonsburg PA) for both the field simulation (FEM) and the circuit simulation (Kozlov and Turner 2009, Guérin et al 2014, 2015). Tuning capacitors were modeled as such in the field simulation step (as opposed to replacing them by ports and fine tuning their value in the circuit simulation step), in order to minimize RAM and CPU requirements. Input power was 0.04 W (1 Volt driving each quadrature port). The simulated coil was tuned and matched for each body model in order to guarantee minimal reflected power for all patient models (this could otherwise be a confounding factor when reporting lead-tip SAR values). Tuning and matching capacitors were adjusted in the Ansys Electronics circuit simulator in order to achieve S11 < −20 dB at the driving ports of the BC coil (the optimized capacitor values were similar for all body models, with a variation smaller than 10% across models). For each body model, we performed a single full-wave simulation which was subsequently used for both tuning & matching and EM field calculation. This is a positive feature of the co-simulation process which dramatically reduces computation time compared to other full-wave simulation approaches such as FDTD (Kozlov and Turner 2009, Guérin et al 2014, 2015). The Ansys Electronics FEM field solver (previously known as HFSS) discretizes the simulation space using a tetrahedral mesh that is refined in an iterative process in order to guarantee accurate representation of the electric field in regions where it varies rapidly. In addition, we imposed maximum tetrahedron edge length constraints that are shown in figure 5. Constraints were imposed in the entire body region (edge length < 15 mm), in a box encompassing the left and right DBS lead-tips (edge length < 3 mm) and in smaller cylinders surrounding each lead tip (edge length < 0.5 mm). Maximum edge length constraints were also imposed in an air box surrounding the coil. This was done to help the field simulator converge faster (since we know that the electric field varies very quickly in these regions) as well as to ensure adequate representation of the electric field with no artifacts. The tetrahedron discretization used in Ansys Electronics is adaptive and multiscale and is therefore efficient for solving Maxwell’s equations in models with vastly different geometrical dimensions (the coil has a characteristic length expressed in meters whereas the DBS electrodes’ characteristic length is expressed in millimeters). However, this representation is not easy to manipulate for post-processing of the fields. We therefore exported the field solutions onto a voxel grid with uniform isotropic resolution of 0.1 mm by interpolation of the fields values at voxel positions using the tetrahedron basis functions (this was done using the Field Calculator tool in Ansys Electronics). We point out that the resolution of the tetrahedron mesh used internally by Ansys Electronics and that of the voxel grid used for post-processing are not related in a simple manner, since these are different bases of representation of the fields. In particular, the maximum tetrahedron edge length (constrained to be smaller than 0.5 mm in the vicinity of the DBS electrodes) can typically be greater than the voxel grid resolution (we use 0.1 mm) without compromising the accuracy of the field representation. This is for two reasons. First, at constant edge length, a tetrahedron volume is 8.5 times smaller than that of a cube (Vcube = a3, Vtet = a3/(6 √2), where a is the edge length of the cube and tetraheadron). Second, the field variation inside tetrahedrons is modeled as a linear variation of the field values at the vertices (1st order basis function) (Jin 2011) whereas the field variation in a voxel element is modeled as constant (0th order basis function). As a result, fewer tetrahedron elements than voxel elements are needed to accurately represent EM fields. Since the metric of interest in this work is SAR at the DBS electrode-tissue interface, convergence of the ANSYS adaptive meshing process was assessed by tracking the absorbed power around the DBS electrode tips at each iteration. Convergence was reached when this metric varied by less than 3%.

Figure 4.

(A) Coil simulated in this work, loaded with the Freddie patient model. The coil is a 32-rung high-pass BC driven in quadrature (the 0° and 90° driving port locations are shown in red). (B) Top view of the simulation setup showing the shield (in grey), coil and patient model.

Figure 5.

Visualization of the Ansys Electronics mesh solution for Kurt (mesh solutions for the other models are similar). The figure insets show increasing zoom levels around the electrode tips, which are accompanied with more stringent maximum tetrahedral edge length constraints.

Impact of body model realism on DBS lead-tip SAR

In addition to the models shown in figure 3, we created a brain model for Freddie containing grey matter (GM), white matter (WM), cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and the eyes. This brain model was derived from a 1 mm isotropic clinical MPRAGE acquisition (MRI) of the same patient acquired before surgical implantation of the DBS leads. We segmented the MPRAGE data into GM, WM and CSF classes using the expectation-maximization segmenter with atlas of 3D Slicer (Fedorov et al 2012). The eyes were segmented manually. Voxel representations of the GM, WM, CSF and eyes classes were transformed into 2-manifold, watertight, non-intersecting surface meshes following the processing pipelines shown in figures 1 and 2. This surface mesh brain model was manually registered to the bone/air/soft tissues Freddie model shown in figure 3 using rotations and translations (rigid registration). We initially attempted to model the full DBS implant model of figure 3 in conjunction with this brain segmentation Freddie model, but found that the Ansys Electronics internal meshing routine systematically failed. Therefore, we simulated a simplified DBS implant model with the correct geometrical path but containing only the lead portion of the implant (i.e. extension cables and IPG were not modeled) and with a single, straight internal conductor. The resulting model is shown in figure 6(A).

Figure 6.

(A) Tissue classes of the Freddie body model with full brain segmentation. Also shown are the simplified DBS left and right leads, which do not comprise extension cables nor the IPG and contain a single internal straight wire conductor. (B) Conductivity maps (coronal slice) of the full brain segmentation and the six simplified Freddie body models.

In order to assess the impact of model simplification on SAR, we also generated six simplified Freddie models with a single tissue class assigned to the whole body (uniform body model) and for the brain (uniform brain) shown in figure 6(B). The uniform body models are denoted UNIF BODY 1–3 and were assigned dielectric properties equal to those of average of grey and WM, WM and GM, respectively. The uniform brain body models are denoted UNIF BRAIN 1–3 and were assigned, in the brain, dielectric properties equal to those of average of GM and WM, WM and GM, respectively (the bones, internal air and soft tissue classes were unchanged across those models, i.e. only the dielectric properties of the average brain were varied). The dielectric properties of the different tissue classes are given in table 1. All models were loaded in the 3 T birdcage coil of figure 4(A) and were simulated as explained in the previous section. In order to assess the impact of body model realism on SAR under multiple excitation conditions, we analyzed SAR maps obtained while driving the coil in linear mode at ports 0° and 90° (as opposed to in quadrature mode).

Results

Creation of the virtual CT (registration and stitching of the head & neck CTs) took ~30 min per patient. Extraction of the DBS path and topology correction took ~1 h. Creation of the full implant model around the geometrical path took ~1 additional hour using VBS scripting within the Ansys Electronics environment. The automatic segmentation of the virtual CT volume into bone, air and soft tissue classes was very fast (a couple of seconds). Manual cleaning and correction of errors in the automatic segmentation was the bottleneck of the entire approach, taking ~10 h per patient. Creation of the final watertight, 2-manifold surface meshes from the clean segmented data was relatively fast, ~15 min per model.

In Janis, Kurt and Michael (figure 3), a single IPG is used to drive both the left and right DBS electrodes. In contrast, Freddie and Angus (figure 3) are implanted with two IPGs that individually drive the left and right DBS leads. In Angus, in addition to the two functional DBS leads, two bilateral abandoned leads are also present for unknown reasons. The surface meshes of Kurt, Angus, Freddie, Michael and Janis contain 150 516; 196 922; 142 306; 184 253 and 150 294 faces, respectively. This level of mesh complexity allows accurate representation of the DBS implant and major bone and internal air body structures while minimizing memory requirement, so that the resulting models are relatively easy to manipulate.

Figure 7 shows B1+ magnitude, electric field magnitude and unaveraged SAR maps created in the five DBS patient models by the 3 T quadrature birdcage coil shown in figure 4. B1+ is, as expected, relatively uniform— although not perfectly so—over the imaging volume. The B1+ artifact caused by the DBS implant is clearly visible on those images. This is due to the fact that the current induced by the BC onto the internal metallic wiring of the DBS implant creates a magnetic field with a non-zero right-handed transverse component. The severity of this artifact depends on the magnitude of the induced current as well as the angle between the DBS lead and the static B0 magnetic field. The electric field maps show large electric field magnitudes in the bone, which is expected since this is a low conductivity material. Despite this, SAR is low in the skull because of the proportionality between SAR and the electrical conductivity. The DBS-induced B1+ and electric field artifacts do not match spatially. This is because the electric field, and therefore SAR, is large only at the locations of contact between the brain tissue and the DBS electrodes (at other locations along the lead, the insulation sheath prevents the current induced on the DBS wiring to flow into the brain tissue). In contrast, the B1+ artifact is present all along the lead and not at the electrode location. This is because the insulating sheath of the implant is essentially transparent to magnetic fields: Like all other materials in the body, its permeability is close to 1.

Figure 7.

B1+ magnitude, electric field magnitude and unaveraged SAR maps at 3 transverse locations for the 5 patient models simulated.

We have shown in a previous publication that accurate reporting of peak SAR values in DBS patients requires calculation of the SAR distribution on a high-resolution grid (Guerin et al 2018). This is due to the very rapid variation of SAR around the implant tip. For this reason, we show on figure 8 maximum intensity projection maps of SAR, for all patient models, computed on a 0.1 mm isotropic grid. In addition, we show SAR maps for different levels of mass averaging: from no averaging up to 10 mg averaging (voxels belonging to the DBS implant were excluded from the averaging volume). We use a logarithmic color scale to allow visualization of the SAR distribution in the vicinity as well as away from the electrodes. Peak SAR decreases monotonically with the size of the target averaging mass. Interestingly, the peak SAR variability across the different patients (standard deviation of figure 9(A)) also decreases monotonically so that the inter-subject percent peak SAR variability is independent from the target averaging mass (figure 9(B)).

Figure 8.

Maximum intensity projection of the 0.1 mm isotropic SAR maps of the simulated patient models with different averaging, ranging from no averaging to 10 mg averaging. The BC is driven in quadrature for all patients (0.04 W total input power). The image scale is logarithmic to allow clear visualization of the SAR variation in the vicinity and away from the lead.

Figure 9.

(A) Mean and standard deviation of peak SAR across all body models for different averaging volumes. (B) Variability (=standard deviation/mean) of peak SAR across all patient models for different averaging volumes.

Figure 10 shows peak SAR around the left and right electrodes for all patient models for a target averaging mass of 1 mg of tissue (for Angus, we also show the peak SAR in the vicinity of the left and right abandoned leads). There does not seem to be a consistent pattern of dominant left/right peak SAR depending on the side of the IPG implantation. Indeed, Kurt and Janis are implanted on the right side, yet peak SAR is around the left electrode for Kurt and around the right electrode for Janis.

Figure 10.

Peak SAR of the simulated models around the left and right electrodes. SAR maps were averaged using a target mass of 1 mg. All patient models have two leads, except Angus who has two active and two abandoned leads.

SAR maps (1 mg average) of the full brain segmentation and six simplified Freddie body models are shown in figure 11 for excitation of the BC at the 0° and 90° ports (linear polarization). The SAR map of the full brain segmentation model is used as the reference to compute errors, as this is the model with the highest level of realism. For each excitation condition, the SAR maps appear similar across models. The 1 mg average peak SAR variability across the full brain segmentation and simplified models (standard deviation divided by mean) was 14% when driving the coil at the 0° port and 18% when driving it at the 90° port. The B1+ efficiency of the coil was very similar in all models (25.2 ± 0.9 nT V−1 for the 0° port excitation, 25.0 ± 0.9 nT V−1 for the 90° port excitation. This represents a B1+ variability across model of <4%).

Figure 11.

(A) 1 mg average SAR maximum intensity projection maps for the full brain segmentation and the six simplified Freddie models when driving the BC coil at the 0° port (1 Volt excitation, linear polarization). Also shown in the conductivity map for the full brain segmentation model. The black numbers below each SAR map are the peak SAR in mW/kg. (B) Same as A, but when driving the BC coil at the 90° port (1 Volt excitation, linear polarization).

Figure 12 shows the peak SAR values obtained for all the Freddie body models as well as the prediction error of the six simplified models. Both for the uniform body and uniform brain models, the minimum error was achieved when assigning the dielectric properties of the tissue in contact with the DBS electrodes to those of WM (UNIF BODY 2 and UNIF BRAIN 2). This is because, in the full brain segmentation model, the DBS electrodes are in contact with the WM, therefore WM is the correct tissue choice to use in the simplified models. Overall, the peak SAR prediction errors were smaller for the uniform brain models (UNIF BRAIN 1–3) than for the uniform body models (UNIF BODY 1–3), which indicates that the more tissue classes modeled, the more accurate the resulting SAR prediction.

Figure 12.

(A) Peak 1 mg average SAR values for the full brain segmentation and the six simplified Freddie models. (B) Peak 1 mg SAR error for the six simplified Freddie models (reference is the full brain segmentation model).

Discussion

In this work, we designed and developed a virtual population of five DBS models based on clinical CT images of patients scanned at the Massachusetts General Hospital. The patient models are realistic representations of the DBS implants path and internal components, IPG as well as three of the most relevant tissue classes for EM simulation (bones, internal air and soft tissues). The overall process for creation of the models was relatively fast, the bottleneck being manual correction and cleanup of the automatic bone/air/soft tissue expectation-maximization segmentation output—this took ~10 h per patient, which is significant but not excessive given that the models are created once and can then be used in many simulations. Other steps were much faster (combined time less than 3 h). A major difficulty in performing this work was the lack of availability of high-quality CT patient images covering the entire length of the implant. Indeed, among the thousands of DBS patients treated at our institution, we found only five who received post-DBS implantation 3D CT imaging of both the neck and head and whose image quality was sufficient to create computational models. Mining the patient database and selecting the suitable patient data took several weeks of work.

Despite our best effort to create accurate representations of the implant and organs for each patient, these models are necessarily a simplified representation of reality. An important limitation of our models is that they are truncated below the shoulders and exclude the arms. This was unavoidable because of the reduced field-of-view of the neck CT volumes. Initially, we attempted to remediate this issue by using chest CT volumes in addition to head and neck volumes to create a virtual CT encompassing the arms and the entire torso. However, chest volumes were exceedingly difficult to co-register to the neck CT volumes as the arms, shoulders and lungs move dramatically between imaging sessions. Doing so may require more advanced non-rigid registration of the different volumes, which we will investigate in future work. Another problem with this approach is that only 2 of the 5 patients selected received chest CT exams in addition to their neck and head CTs. A potential solution could be to morph existing full-body models such as the ones from the Virtual Population (Christ et al 2010, Gosselin et al 2014) to our cropped models in order to create realistic limb and torso extensions. An even simpler solution could be to extend the truncated models using simple cylindrical shapes for the arms and the torso. Although this is not a realistic representation of the patients anatomy, this would allow more realistic modeling of loading of the MRI coil (Wolf et al 2012). Ideally, full body models should be created using whole body CT scans of the DBS patients, given that MRI is not easily available for this patient cohort. However, such a study may be difficult to justify because of the increased radiation exposure inherent to CT imaging.

Another limitation of the DBS implant models presented in this work is that they are simplified versions of the devices implanted in vivo. For example, we modeled straight internal conductors instead of helicoidal ones, as in actual devices. As explained in Guerin et al (2018), this impacts the accuracy of SAR predictions but is difficult to overcome because modeling small-pitch helices using FEM is exceedingly difficult due to meshing errors, RAM limitation problems, long computation times, etc. For the patient simulated in Guerin et al (2018), modeling the helicoidal nature of the DBS implant internal conductor resulted in peak SAR values (non-averaged) equal to 0.6× and 1.5× those of the straight conductor model at 1.5 T and 3 T, respectively. In other words, at 1.5 T modeling of helicoidal DBS conductors resulted in a smaller peak SAR than when modeling straight conductors. At 3 T the conclusion is reversed: Helicoidal lead-tip SAR was greater than straight-conductor lead-tip SAR. These observations are in agreement with the work of Cabot et al (2013), who also found that helicoidal lead-tip SAR was smaller than straight-conductor lead-tip SAR at 1.5 T. The difference in SAR values for the helicoidal and straight conductor models was much more pronounced in Cabot et al (10× difference) than in our work however (1.5× difference), which is likely due to the fact that the helix modeled by Cabot et al were much more tightly wound (0.33 mm pitch) than the one we modeled (2 mm pitch). These simulation results show that the shape of the internal DBS conductor (straight versus helicoidal) has a major impact on DBS safety predictions, with the direction of this variation (safer or less safe) depending on the field strength, length of the implant and pitch of the helix simulated. The transfer function (TF) approach for DBS lead-tip SAR prediction (Park et al 2007, Neufeld et al 2009, Cabot et al 2013, Córcoles et al 2015, Gudino et al 2015) can handle very complex geometries such as the internal helicoidal conductors, and in principle is well adapted to this problem. However, in most implementations, the TF of an implant is simulated or measured for a straight configuration of the implant without loops or turns whereas actual implant paths typically contain many turns, loops and kinks. The inductance matrix of the discretized implant (i.e. the matrix of self- and mutual-inductance values for the different segments of the discretized lead) depends on the precise implant path, therefore in theory the TF should be computed for the exact implant path geometry in the patient. This is arguably not much simpler than performing a full-wave simulation of the patient with the DBS implant. Despite these limitations of the TF approach, it is possible that a combination of the TF and full-wave EM simulation approaches could lead to accurate modeling of the internal DBS lead structure with reduced computational complexity. One possible idea, which we will study in future work, could be to simulate the TF of a realistic implant path using a full-wave simulation in a uniform sphere or cylinder, which would reduce the computational burden. Such an accurate TF computation could then be used to quickly simulate the lead-tip SAR when illuminating this specific patient with different EM excitations (different coils, isocenter positions etc…).

Another limitation of our models is that they do not model the main brain tissues such as GM, WM, eyes and CSF, except for Freddie. Simulations of the full brain segmentation Freddie model and its simplified versions in this work indicate that, for accurate prediction of the peak SAR when using an average-brain model, it is important to set the dielectric properties of the average brain to that of the tissue in contact with the electrodes in the actual patient. In this work, for both the 0° port and 90° port excitation conditions, modeling the average brain as GM instead of WM (which is the correct choice since this is the tissue in contact with the DBS electrodes in the full brain segmentation model) yielded a peak SAR prediction error of 36% (UNIF BRAIN 3). In contrast, the error associated with modeling the brain as a single tissue class assigned to the correct WM dielectric properties was only 6% (UNIF BRAIN 2). In the actual Freddie patients, we point out that electrodes are in fact in contact with the sub-thalamic nucleus (STN), which is GM. The STN is not included in the 3D Slicer atlas that we used for Freddie’s brain segmentation however, which is the reason why in our model the electrodes are in contact with WM (we do not expect this to affect our conclusion. The main point is to assign to the average model the dielectric properties of the tissue in contact with the DBS electrodes, be it WM or GM or something else). We also found that modeling tissue classes distal to the DBS electrodes, such as bones and internal air, improved the accuracy of the peak SAR prediction, but that this effect was smaller (SAR prediction error was 20% for BODY UNIF 2) than the effect of incorrect modeling of the correct tissue class in contact with the electrode (SAR prediction error was 36% for UNIF BRAIN 3). We point out that, although these errors are significant, they are much smaller than those associated with inaccuracies in modeling the DBS implant. In our previous work, we found lead-tip SAR variations as high as 4-fold when modeling (or not) extracranial loops (Guerin et al 2018) and variations in the 1.5–1.9-fold range associated with modeling (or absence of modeling) of helicoidal internal wires, extension cables and the IPG (Guerin et al 2018). Other authors have reported similar results. Cabot et al found that modeling helicoidal internal wires versus straight wires had a 21-fold effect on lead-tip SAR in their model (study performed at 1.5 T) (Cabot et al 2013). Golestani Rad et al found that different modeling of the DBS extracranial loops (i.e. figure eight loop, concentric loop or no loop) led to lead-tip SAR variations as large as 151-fold (study performed at 3 T) (Golestanirad et al 2016a). Based on these results, we rank the relative importance of modeling realism as follows: (1) Accurate modeling of the DBS implant (extension cables, IPG, correct modeling of the DBS path including extracranial loops, correct modeling of the DBS implant internal structure); (2) Modeling of the proper tissue class in contact with the DBS electrodes; (3) Realistic modeling of the other tissue classes distal from the DBS electrodes, such as bone, internal air, eyes etc… Since the errors associated with (1) are orders of magnitude greater than those associated with (2) and (3), our recommendation to researchers interested in DBS patient safety for MRI is to focus on the development of highly realistic DBS implant models as opposed to generation of realistic body models with many tissue classes.

We were able to include representations of the GM, WM, CSF and eyes tissue classes to the Freddie model but not the other models. The main reason is the absence of availability of high quality T1-weighted MR images for Janis, Kurt, Michael and Angus. Another problem is that including a brain segmentation in the DBS patient model significantly increases the complexity of the EM solve and, as explained in the previous paragraph, does not result in a large improvement in SAR prediction accuracy (only 6%, which is the SAR prediction error of UNIF BRAIN 2). This increased complexity can in fact have a negative effect on SAR prediction accuracy. Indeed, in this work we were not able to simulate the full brain segmentation Freddie body model in conjunction with our most realistic model of the DBS implant for this patient (this caused failures of the Ansys Electronics internal meshing routine). Instead, we were forced to simulate a simplified DBS implant model with no extension cables, no IPG and a single straight internal conductor. This, as explained above, results in a much greater SAR prediction error than realistic modeling of the patient’ brain.

Despite the limitations discussed above, we believe that the DBS computational models presented in this work can be a valuable tool to the MRI safety modeling community as they represent a natural ‘next step’ in modeling realism for this patient cohort. Indeed, the alternative used by many researchers is to use existing body models (such as the Virtual Family (Christ et al 2010)) and ‘implant’ them with made-up DBS implant paths. These models often do not have the length of actual implants (for example, often only the lead portions of the implants are modeled, not the extension cables), do not have extracranial loops and do not model the IPG. As explained above, these simplifications are known to have a large impact on predicted SAR (Golestanirad et al 2016a, 2016b, Guerin et al 2018). In contrast, the models presented here are full-length (lead and extension cables are modeled) and include the IPG as well as three of the most important anatomical structure classes for EM simulation: bone, air, and soft tissues. In addition, unlike mixed models (made-up DBS path in a realistic body model), in our models the DBS implant and patient anatomy are perfectly registered since they are both extracted from the same data.

In addition to developing and disseminating the five DBS patient models presented in this work, we simulated the inter-patient variability of peak SAR at 3 Tesla using a quadrature birdcage body coil for excitation. The main result is that the peak SAR variability is independent of the SAR averaging method and is equal to ~45%. This is due to the fact that both the population average and the population standard deviation of peak SAR decrease in the same amount with increasing target averaging mass, thus their ratio is roughly constant. Because of this, we hypothesize that the normal inter-patient variability of peak temperature across DSB patients is also ~45%, which we will verify in a future publication.

Acknowledgments

NIH grants K99/R00 EB019482 and NIH grant R01EB006847. The mention of commercial products, their sources, or their use in connection with material reported herein is not to be construed as either an actual or implied endorsement of such products by the Department of Health and Human Services.

References

- Angelone LM, Ahveninen J, Belliveau JW and Bonmassar G 2010. Analysis of the role of lead resistivity in specific absorption rate for deep brain stimulator leads at 3T MRI medical imaging IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 29 1029–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bewernick BH, Hurlemann R, Matusch A, Kayser S, Grubert C, Hadrysiewicz B, Axmacher N, Lemke M, Cooper-Mahkorn D and Cohen MX 2010. Nucleus accumbens deep brain stimulation decreases ratings of depression and anxiety in treatment-resistant depression Biol. Psychiatry 67 110–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonmassar G, Serano P and Angelone LM 2013. 6th Int. IEEE/EMBS Conf. on Neural Engineering (NER) pp 747–50 [Google Scholar]

- Cabot E, Lloyd T, Christ A, Kainz W, Douglas M, Stenzel G, Wedan S and Kuster N 2013. Evaluation of the RF heating of a generic deep brain stimulator exposed in 1.5 T magnetic resonance scanners Bioelectromagnetics 34 104–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christ A, Kainz W, Hahn EG, Honegger K, Zefferer M, Neufeld E, Rascher W, Janka R, Bautz W and Chen J 2010. The virtual family— development of surface-based anatomical models of two adults and two children for dosimetric simulations Phys. Med. Biol 55 N23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Córcoles J, Zastrow E and Kuster N 2015. Convex optimization of MRI exposure for mitigation of RF-heating from active medical implants Phys. Med. Biol 60 7293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davids M, Guérin B, Schad LR and Wald LL 2017. Modeling of peripheral nerve stimulation thresholds inrealistic body models Proc. ISMRM vol 25 p 3 [Google Scholar]

- Denys D, Mantione M, Figee M, van den Munckhof P, Koerselman F, Westenberg H, Bosch A and Schuurman R 2010. Deep brain stimulation of the nucleus accumbens for treatment-refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 67 1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deuschl G, Schade-Brittinger C, Krack P, Volkmann J, Schäfer H, Bötzel K, Daniels C, Deutschländer A, Dillmann U and Eisner W 2006. A randomized trial of deep-brain stimulation for Parkinson’s disease New Engl. J. Med 355 896–908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eryaman Y, Akin B and Atalar E 2011. Reduction of implant RF heating through modification of transmit coil electric field Magn. Reson. Med 65 1305–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eryaman Y, Turk EA, Oto C, Algin O and Atalar E 2012. Reduction of the radiofrequency heating of metallic devices using a dual-drive birdcage coil Magn. Reson. Med 69 845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eryaman Y et al. 2014. Parallel transmit pulse design for patients with deep brain stimulation implants Magn. Reson. Med 73 1896–903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabri A, Giezmann G-J, Kettner L and Schönherr S 1998. On the design of CGAL the computational geometry algorithms library Technical Report Departement Informatik, ETH Zürich vol 291 [Google Scholar]

- Fang Q and Boas DA 2009. Tetrahedral mesh generation from volumetric binary and grayscale images IEEE Int. Symp. on Biomedical Imaging: From Nano to Macro pp 1142–5

- Fedorov A, Beichel R, Kalpathy-Cramer J, Finet J, Fillion-Robin J-C, Pujol S, Bauer C, Jennings D, Fennessy F and Sonka M 2012. 3D Slicer as an image computing platform for the quantitative imaging network Magn. Reson. Imaging 30 1323–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischl B 2012. FreeSurfer NeuroImage 62 774–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel S, Lau R and Gabriel C 1996. The dielectric properties of biological tissues: II. Measurements in the frequency range 10 Hz to 20 GHz Phys. Med. Biol 41 2251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golestanirad L, Angelone LM, Iacono MI, Katnani H, Wald LL and Bonmassar G 2016a. Local SAR near deep brain stimulation (DBS) electrodes at 64 and 127 MHz: a simulation study of the effect of extracranial loops Magn. Reson. Med 78 1558–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golestanirad L, Keil B, Angelone LM, Bonmassar G, Mareyam A and Wald LL 2016b. Feasibility of using linearly polarized rotating birdcage transmitters and close-fitting receive arrays in MRI to reduce SAR in the vicinity of deep brain simulation implants Magn. Reson. Med 77 1701–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosselin M-C, Neufeld E, Moser H, Huber E, Farcito S, Gerber L, Jedensjoe M, Hilber I, Di Gennaro F and Lloyd B 2014. Development of a new generation of high-resolution anatomical models for medical device evaluation: the virtual population 3.0 Phys. Med. Biol 59 5287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg BD, Malone DA, Friehs GM, Rezai AR, Kubu CS, Malloy PF, Salloway SP, Okun MS, Goodman WK and Rasmussen SA 2006. Three-year outcomes in deep brain stimulation for highly resistant obsessive–compulsive disorder Neuropsychopharmacology 31 2384–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudino N, Sonmez M, Yao Z, Baig T, Nielles-Vallespin S, Faranesh A, Lederman R, Martens M, Balaban R and Hansen M 2015. Parallel transmit excitation at 1.5 T based on the minimization of a driving function for device heating Med. Phys 42 359–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guérin B, Gebhardt M, Cauley S, Adalsteinsson E and Wald LL 2014. Local specific absorption rate (SAR), global SAR, transmitter power, and excitation accuracy trade-offs in low flip-angle parallel transmit pulse design Magn. Reson. Med 71 1446–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guérin B, Gebhardt M, Serano P, Adalsteinsson E, Hamm M, Pfeuffer J, Nistler J and Wald LL 2015. Comparison of simulated parallel transmit body arrays at 3 T using excitation uniformity, global SAR, local SAR and power efficiency metrics Magn. Reson. Imaging 73 1137–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerin B, Serano P, Iacono M, Herrington T, Widge A, Dougherty D, Bonmassar G, Angelone L and Wald L 2018. Realistic modeling of deep brain stimulation implants for electromagnetic MRI safety studies Phys. Med. Biol 63 095015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson JM, Tkach J, Phillips M, Baker K, Shellock FG and Rezai AR 2005. Permanent neurological deficit related to magnetic resonance imaging in a patient with implanted deep brain stimulation electrodes for Parkinson’s disease: case report Neurosurgery 57 E1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrington TM, Cheng JJ and Eskandar EN 2016. Mechanisms of deep brain stimulation J. Neurophysiol 115 19–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huff W, Lenartz D, Schormann M, Lee S-H, Kuhn J, Koulousakis A, Mai J, Daumann J, Maarouf M and Klosterkötter J 2010. Unilateral deep brain stimulation of the nucleus accumbens in patients with treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder: outcomes after one year Clin. Neurol. Neurosurgery 112 137–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacono MI, Makris N, Mainardi L, Angelone LM and Bonmassar G 2013. MRI-based multiscale model for electromagnetic analysis in the human head with implanted DBS Comput. Math. Methods Med 10.1155/2013/694171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Jin J-M 2011. Theory and Computation of Electromagnetic Fields (New York: Wiley; ) ( 10.1002/9780470874257) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlov M and Turner R 2009. Fast MRI coil analysis based on 3D electromagnetic and RF circuit co-simulation J. Magn. Reson 200 147–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malone DA Jr, Dougherty DD, Rezai AR, Carpenter LL, Friehs GM, Eskandar EN, Rauch SL, Rasmussen SA, Machado AG and Kubu CS 2009. Deep brain stimulation of the ventral capsule/ventral striatum for treatment-resistant depression Biol. Psychiatry 65 267–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayberg HS, Lozano AM, Voon V, McNeely HE, Seminowicz D, Hamani C, Schwalb JM and Kennedy SH 2005. Deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression Neuron 45 651–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre CC, Savasta M, Kerkerian-Le Goff L and Vitek JL 2004. Uncovering the mechanism (s) of action of deep brain stimulation: activation, inhibition, or both Clin. Neurophysiol 115 1239–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medtronics 2015. MRI Guidelines for Medtronics Deep Brain Stimulation Systems (Minneapolis, MN: Medtronic; ) [Google Scholar]

- Mohsin SA 2011. Concentration of the specific absorption rate around deep brain stimulation electrodes during MRI Prog. Electromagn. Res 121 469–84 [Google Scholar]

- Mohsin SA, Sheikh NM and Saeed U 2008. MRI induced heating of deep brain stimulation leads: effect of the air-tissue interface Prog. Electromagn. Res 83 81–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neufeld E, Kühn S, Szekely G and Kuster N 2009. Measurement, simulation and uncertainty assessment of implant heating during MRI Phys. Med. Biol 54 4151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SM, Kamondetdacha R, Amjad A and Nyenhuis J 2005. MRI safety: RF-induced heating near straight wires IEEE Trans. Magn 41 4197–9 [Google Scholar]

- Park SM, Kamondetdacha R and Nyenhuis JA 2007. Calculation of MRI-induced heating of an implanted medical lead wire with an electric field transfer function J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 26 1278–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puigdemont D, Pérez-Egea R, Portella MJ, Molet J, de Diego-Adeliño J, Gironell A, Radua J, Gómez-Anson B, Rodríguez R and Serra M 2011. Deep brain stimulation of the subcallosal cingulate gyrus: further evidence in treatment-resistant major depression Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol 15 121–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlaepfer TE, Cohen MX, Frick C, Kosel M, Brodesser D, Axmacher N, Joe AY, Kreft M, Lenartz D and Sturm V 2007. Deep brain stimulation to reward circuitry alleviates anhedonia in refractory major depression Neuropsychopharmacology 33 368–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serano P, Angelone LM and Bonmassar G 2014. Evaluation of multi-section resistive tapered stripline (RTS) lead wires to reduce SAR near implanted DBS electrodes during MRI Proc. of the ISMRM vol 22 p 4867 [Google Scholar]

- Setsompop K, Gagoski BA, Polimeni JR, Witzel T, Wedeen VJ and Wald LL 2012. Blipped-controlled aliasing in parallel imaging for simultaneous multislice echo planar imaging with reduced g-factor penalty Magn. Reson. Med 67 1210–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidailhet M, Vercueil L, Houeto J-L, Krystkowiak P, Benabid A-L, Cornu P, Lagrange C, Tézenas du Montcel S, Dormont D and Grand S 2005. Bilateral deep-brain stimulation of the globus pallidus in primary generalized dystonia New Engl. J. Med 352 459–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wald LL 2012. The future of acquisition speed, coverage, sensitivity, and resolution NeuroImage 62 1221–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver FM, Follett K, Stern M, Hur K, Harris C, Marks WJ Jr, Rothlind J, Sagher O, Reda D and Moy CS 2009. Bilateral deep brain stimulation vs best medical therapy for patients with advanced Parkinson disease J. Am. Med. Assoc 301 63–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webpage of the Martinos Center Phantom Resource. 2018 https://phantoms.martinos.org/Main_Page.

- Widge AS, Arulpragasam AR, Deckersbach T and Dougherty DD 2015. Emerging Trends in the Social and Behavioral Sciences Emerging Trends in the Social and Behavioral Sciences: An Interdisciplinary, Searchable and Linkable Resource ed Scott RA and Kosslyn SM (New York: Wiley; ) ( 10.1002/9781118900772.etrds0103) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Widge AS and Dougherty DD 2015. Deep brain stimulation for treatment-refractory mood and obsessive-compulsive disorders Curr. Behav. Neurosci. Rep 2 187–97 [Google Scholar]

- Wolf S, Diehl D, Gebhardt M, Mallow J and Speck O 2012. SAR simulations for high-field MRI: how much detail, effort, and accuracy is needed? Magn. Reson. Med 69 1157–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]