Abstract

We examined whether gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms were associated with sleep disturbances in a community-based sample of 337 school-age children from Ypsilanti, Michigan.

Parents completed the sleep-related breathing disorder (SRBD) scale of the Pediatric Sleep Questionnaire and the Conners’ parents rating scale, which included questions concerning GI symptoms. One-fifth of the children screened positive for SDB; the same fraction had sleepiness, and one-quarter snored more than half the time. Similarly, one-quarter of children had two or more GI symptoms. Children with positive SDB scores were 2.22 times as likely to have two or more GI symptoms in the past month after confounder adjustment (95% CI 1.39–3.55). In particular, this relationship appeared to be driven by daytime sleepiness, as children with sleepiness had about a 2-fold higher prevalence of two or more GI symptoms (adjusted prevalence ratio= 1.96, 95% CI 1.18–3.26). Neither snoring nor sleep duration were associated with GI symptoms.

Keywords: sleepiness, sleep-disordered breathing, snoring, stomach, bowel, eating problems

INTRODUCTION

Sleep disturbances are prevalent among school-age children in the United States (US) and worldwide1; over the course of childhood, a quarter of children experience at least one sleep disturbance 2. In particular, sleep disordered breathing (SDB) and short sleep duration are common in pediatric populations; the former is characterized by complete or partial obstruction of the airway, habitual snoring, subsequent awakenings during sleep, and daytime sleepiness 3. Sleep disturbances have been linked to adverse health outcomes in school-aged children such as metabolic disorder and cardiovascular morbidity, in addition to a negative impact on mood, emotional well-being, behavior and academic performance 4.

Similarly, gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms are frequently reported in school-aged children, specifically abdominal pain, nausea/vomiting, and constipation or diarrhea. In a prospective study among 3rd through 8th grade US children, 38% reported weekly abdominal pain 5. An international sample from adolescents from 11 different countries reported that half experienced stomachaches at least monthly in the previous 6 months 6.

An association between sleep disturbance and GI symptoms has been observed among children with autism spectrum disorder 7, but rarely examined in general pediatric populations. Three studies, of which one was US-based, examined specific sleep disturbances- obstructive sleep apnea, insomnia, and poor sleep quality- and reported associations with one of the following GI disorders: gastroesophageal reflux disease irritable bowel syndrome 8 and GI regurgitation 9. A broader examination that includes other common sleep disturbances and GI symptoms is lacking. To fill this gap, we sought to examine whether GI symptoms were associated with sleep duration, sleep-disordered breathing and its subscales snoring and daytime sleepiness in a US community-based sample of elementary school-age children.

METHODS

Study population

A community-based sample of elementary school-aged children from Ypsilanti, Michigan participated in this 2006 cross-sectional study. A detailed description of the study design has been previously reported 10. Briefly, parents of children in grades 2 through 5 of the Ypsilanti Public School System were mailed a letter describing the study, a consent form, and a survey about their children’s sleep and behavior. Consent forms and questionnaires were completed by parents of 341 children (28% response rate). In addition, teachers completed the behavior rating scale for each participant. Families received a $20 gift card and teachers received a $10 book token for participation. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Michigan and the School Board.

Sleep measures: Sleep duration and sleep-related breathing disorder survey

Sleep duration was calculated based on parental-reported typical bedtime and wake time of their child during weekdays. Age-based sleep duration recommendations from the National Sleep Foundation and the American Academy of Sleep Medicine 11,12 were used to classify children to sufficient (≥9 hours) and insufficient sleep (<9 hours) groups. Sleep-disordered breathing symptoms were assessed with the validated sleep-related breathing disorder (SRBD) scale of the Pediatric Sleep Questionnaire 13. This scale contains 22 items about snoring, sleepiness, and inattentive/hyperactive behaviors. Possible responses are “yes”, “no” or “don’t know.” The number of affirmative responses is summed, and responding yes to 33% or more of the reported items indicated a positive screen for risk of pediatric SDB. To further examine the individual association of the SDB subscales -snoring and sleepiness- with GI symptoms, we analyzed these separately, as described below.

Snoring subscale

This subscale is composed of the following 4 questions: when sleeping, does your child 1) Snore more than half the time? 2) Always snore? 3) Snore loudly? 4) Have “heavy” or loud breathing? We calculated the proportion of affirmative responses out of the total number of responses and first analyzed snoring as a continuous score, and then examined snoring characteristics- i.e. frequency and intensity-through questions 1 and 3 separately.

Sleepiness subscale

This subscale included the following 4 questions: does your child 1) Wake up feeling un-refreshed in the morning? 2) Have a problem with sleepiness during the day? 3) Has a teacher or other supervisor commented that your child appears sleepy during the day? 4) Is it hard to wake your child up in the morning? Similar to the snoring subscale, we calculated the proportion of positive responses and first analyzed as a continuous score, and then examined daytime sleepiness as reported by parents or teachers in questions 2 and 3 separately.

Gastrointestinal symptoms: Conners’ parents rating

The Conners’ parent rating is a validated scale clinically used to identify behavioral problems in children aged 3 to 17 y 14. Each question is rated on a Likert scale where 0= not true at all, 1= just a little, 2=pretty much, and 3=very much. This scale includes six domains: conduct problems, learning problems, psychosomatic, impulsive-hyperactive, anxiety, and hyperactivity index. For each domain, a T-score, ranging from 0–100, is calculated for age and sex norms, with a mean T-score of 50 and standard deviation (SD) of 10. A threshold of ≥60 (at least one SD) was used to classify children with anxiety.

The psychosomatic domain included four questions on GI symptoms. Specifically, parents were asked how often in the past month children were bothered by 1) problems with eating (i.e. poor appetite, getting up between bites) 2) stomachaches 3) vomiting or nausea 4) bowel problems (i.e. frequently loose, irregular habits, constipation). For each symptom, a child with a reported response of ≥1 on the Likert scale was classified as having GI symptoms. Because these symptoms naturally cluster, we created a composite score of 2 or more to identify children with GI symptoms.

Covariates

Socio-demographic and health data including information on the child’s sex, age, race/ethnicity, medication use, height, weight, and qualification for school lunch assistance (a proxy for socioeconomic status) were reported by parents. These variables were categorized as shown in Table 1. We calculated BMI (kg/m2) and height-for-age z-scores according to the Center for Disease Control reference 15.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic and health characteristics in relation to sleep duration and sleep-related breathing disorder among 337 elementary schoolchildren from Ypsilanti, Michigan

| Child socio-demographic and health characteristics | Na | Sleep duration (minutes), mean ± SD | Screened positive for risk of SDB, % | Sleepiness subscale, mean ± SD | Snoring subscale, mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 164 | 593 ± 51 | 20.1 | 0.27 ± 0.32 | 0.18 ± 0.28 |

| Female | 173 | 594 ± 53 | 18.5 | 0.25 ± 0.30 | 0.18 ± 0.31 |

| P value | 0.86 | 0.71 | 0.65 | 0.83 | |

| Age | |||||

| 6 to <8 y | 41 | 615 ± 43 | 19.5 | 0.20 ± 0.29 | 0.19 ± 0.29 |

| 8 to <10 y | 169 | 599 ± 46 | 20.1 | 0.26 ± 0.31 | 0.20 ± 0.32 |

| ≥10 y | 127 | 580 ± 59 | 18.1 | 0.28 ± 0.30 | 0.14 ± 0.25 |

| P value | <0.0001 | 0.91 | 0.24 | 0.16 | |

| BMI-for-age z scoresb | |||||

| <−1 | 26 | 605 ± 43 | 7.7 | 0.21 ± 0.29 | 0.11 ± 0.21 |

| −1 to 0 | 41 | 589 ± 41 | 7.3 | 0.19 ± 0.26 | 0.10 ± 0.20 |

| 0 to <1 | 60 | 578 ± 65 | 13.3 | 0.26 ± 0.30 | 0.11 ± 0.22 |

| ≥1 | 106 | 590 ± 49 | 29.3 | 0.30 ± 0.32 | 0.26 ± 0.35 |

| P value | 0.15 | 0.002 | 0.04 | 0.001 | |

| Height-for-age z scoresb | |||||

| <−1 | 42 | 580 ± 58 | 21.4 | 0.38 ± 0.34 | 0.18 ± 0.31 |

| −1 to 0 | 41 | 587 ± 42 | 17.1 | 0.20 ± 0.30 | 0.14 ± 0.29 |

| 0 to <1 | 53 | 597 ± 46 | 18.9 | 0.22 ± 0.28 | 0.16 ± 0.27 |

| ≥1 | 101 | 588 ± 56 | 17.8 | 0.25 ± 0.29 | 0.20 ± 0.31 |

| P value | 0.39 | 0.96 | 0.13 | 0.46 | |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 139 | 595 ± 43 | 18.0 | 0.24 ± 0.30 | 0.15 ± 0.26 |

| African American | 74 | 589 ± 60 | 21.7 | 0.29 ± 0.34 | 0.19 ± 0.30 |

| Other | 124 | 597 ± 53 | 20.2 | 0.27 ± 0.30 | 0.21 ± 0.31 |

| P value | 0.51 | 0.80 | 0.45 | 0.49 | |

| Enrollment in school lunch program | |||||

| No | 141 | 596 ± 46 | 11.4 | 0.17 ± 0.25 | 0.13 ± 0.26 |

| Yes | 190 | 592 ± 55 | 25.3 | 0.32 ± 0.32 | 0.22 ± 0.31 |

| P value | 0.51 | 0.002 | <0.0001 | 0.003 | |

| Medication use | |||||

| No | 246 | 595 ± 52 | 13.8 | 0.23 ± 0.28 | 0.16 ± 0.28 |

| Yes | 89 | 589 ± 54 | 34.8 | 0.36 ± 0.35 | 0.25 ± 0.32 |

| P value | 0.37 | <0.0001 | 0.001 | 0.02 | |

| Anxiety T scores | |||||

| <60 | 253 | 593 ± 54 | 14.6 | 0.21 ± 0.28 | 0.16 ± 0.28 |

| ≥60 | 82 | 596 ± 46 | 33.7 | 0.42 ± 0.35 | 0.25 ± 0.33 |

| P value | 0.60 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.02 |

These sample sizes are based on the full sample of children who have at least one sleep measure (n=337). Sample sizes are slightly different depending on the sleep measure (for SDB measures n=337; for sleep duration and sleepiness subscale n=328; for snoring subscale n=326).

Calculated based on the CDC reference [15]

Statistical Analysis

Of the 341 children whose parents returned the initial questionnaire, 337 completed the SRBD scale and the Conners’ survey questions and thus were included in the analytic sample. We first examined associations of sleep measures or GI symptoms by categories of anthropometric and sociodemographic correlates. We then used Poisson regression with a log link and robust error variance to calculate prevalence ratios and 95% confidence intervals, where presence of at least two GI symptoms was the dichotomous outcome with sleep measures as predictors. In adjusted analyses, we controlled for potential confounders determined a prior: sex, age, enrollment in school lunch program, medication use, and anxiety. To address missingness of weight and height values, we conducted sensitivity analyses where we imputed (10 times) the missing BMI- and height-for-age z scores using a Markov Chain Monte Carlo technique with the Proc MI procedures of SAS. We used Proc MIANALYZE to combine parameter estimates. Except for these sensitivity analyses, all analyses were performed in Stata 13.1.

RESULTS

The mean age of the children was 9.0 (SD 1.3), and about half of the sample (49%) were male. The average weekday sleep duration ± SD was 9.9 (SD 0.9) hours. Sleep duration was inversely associated with age category. One-fifth of the children screened positive for SDB and a similar proportion had parental-reported sleepiness, while one-quarter snored >half the time. Children at risk of SDB had higher BMI-for-age z-scores, were more likely to be enrolled in the school lunch program, to have anxiety T scores ≥60, or to be on some type of medication (Table 1). Of children with medication use, 46% used allergy or asthma medications, 28% used stimulants, 8% used depression, anxiety or mood stabilizing drugs, 6% used drugs for dermatologic issues, 6% used sleep medications, and 18% used another type of drug. Sleepiness and snoring subscales were positively associated with BMI-for-age z scores, enrollment in school lunch program, medication use and anxiety T scores.

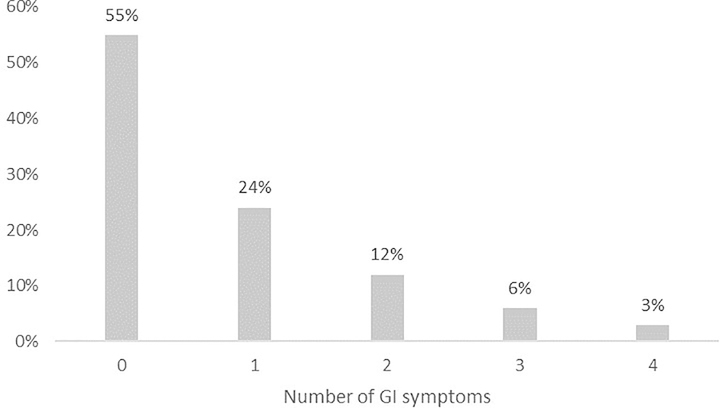

Similarly, GI symptoms were common in this sample, with one-quarter of children having trouble with eating, about a third having stomachaches, one-tenth having nausea/vomiting, and one-fifth having bowel problems. In general, one-quarter of children had two or more of these GI symptoms in the past month (Figure 1); within this group, the most common complaint in this group of children was stomachaches, followed by eating problems, bowel problems, and nausea/vomiting, respectively (Supplemental Material). Children using medication and who had anxiety T scores ≥60 were more likely to have had two or more GI symptoms in the past month (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Distribution of the number of GI symptoms reported per child.

Table 2.

Children with 2 or more gastrointestinal symptoms among 337 elementary school children from Ypsilanti, Michigan, by socio-demographic and health characteristics

| Child socio-demographic and health characteristics | Reported having 2 or more GI symptoms |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 21.3 |

| Female | 15.0 |

| P value | 0.13 |

| Age | |

| 6 to <8 y | 17.1 |

| 8 to <10 y | 17.2 |

| ≥10 y | 19.7 |

| P value | 0.84 |

| BMI-for-age z scores | |

| <−1 | 15.4 |

| −1 to 0 | 14.6 |

| 0 to <1 | 25.0 |

| ≥1 | 12.3 |

| P value | 0.20 |

| Height-for-age z scores | |

| <−1 | 23.8 |

| −1 to 0 | 14.6 |

| 0 to <1 | 11.3 |

| ≥1 | 16.8 |

| P value | 0.43 |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White, non-Hispanic | 20.9 |

| African American | 12.1 |

| Other | 21.7 |

| P value | 0.11 |

| Enrollment in school lunch program | |

| Yes | 16.3 |

| No | 19.5 |

| P value | 0.46 |

| Medication use | |

| No | 15.0 |

| Yes | 25.8 |

| P value | 0.02 |

| Anxiety T scores | |

| <60 | 15.4 |

| ≥60 | 26.5 |

| P value | 0.02 |

Sleep-disordered breathing was related to parent-reported GI symptoms (Table 3). Children who screened positive for SDB were 2.53 times as likely to have two or more GI symptoms in the past month as those without SDB (95% CI 1.63–3.94; P<0.01). The association remained after adjustment for sex, age, enrollment in the school lunch program, medication use, and anxiety T scores ≥60 (PR 2.22, 95% CI 1.39–3.55; P<0.01).

Table 3.

Association between gastrointestinal symptoms and measures of sleep duration and sleep-disordered breathing among 337 elementary schoolchildren from Ypsilanti, Michigan

| Sleep measurea | N | Probability of reporting 2 or more GI symptoms | Unadjusted prevalence ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted prevalence ratio (95% CI)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep duration | ||||

| 9 hr or more | 305 | 17.7 | Reference | Reference |

| < 9 hr | 23 | 21.7 | 1.23 (0.54, 2.77) | 1.25 (0.55, 2.83) |

| P value | 0.62 | 0.60 | ||

| Sleep-disordered breathing | ||||

| Screened positive for SDB | ||||

| No | 272 | 14.0 | Reference | Reference |

| Yes (score >0.33) | 65 | 35.4 | 2.53 (1.63, 3.94) | 2.22 (1.39, 3.55) |

| P value | <0.0001 | 0.006 | ||

| SDB subscale, continuous | 7.38 (3.21, 17.01) | 5.61 (2.16, 14.57) | ||

| P value | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||

| Snoring | ||||

| Snoring subscale, continuous | 1.89 (0.96, 3.74) | 1.74 (0.86, 3.51) | ||

| P value | 0.07 | 0.12 | ||

| Snores >half the time | ||||

| No | 247 | 17.8 | Reference | Reference |

| Yes | 76 | 18.4 | 1.03 (0.60, 1.78) | 0.99 (0.58, 1.69) |

| P value | 0.90 | 0.97 | ||

| Snores loudly | ||||

| No | 275 | 16.4 | Reference | Reference |

| Yes | 50 | 22.0 | 1.34 (0.75, 2.42) | 1.16 (0.65, 2.07) |

| P value | 0.32 | 0.61 | ||

| Sleepiness | ||||

| Sleepiness subscale, continuous | 4.02 (2.20, 7.34) | 3.60 (1.85, 7.02) | ||

| P value | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||

| Daytime sleepiness | ||||

| No | 262 | 14.5 | Reference | Reference |

| Yes | 62 | 32.3 | 2.22 (1.40, 3.54) | 1.96 (1.18, 3.26) |

| P value | 0.001 | 0.009 | ||

| Teacher-rated sleepiness | ||||

| No | 298 | 15.4 | Reference | Reference |

| Yes | 35 | 40.0 | 2.59 (1.59, 4.21) | 2.17 (1.28, 3.67) |

| P value | <0.0001 | 0.004 |

All sleep measures are based on parent report. Teacher-rated sleepiness refers to whether a parent has been informed by the child’s teacher that the child appears sleepy in class.

Adjusted for sex, age, enrollment in school lunch program, medication use and anxiety T scores

Within the SDB subscales- sleepiness and snoring- only sleepiness was associated with GI symptoms, such that children with parent-reported daytime sleepiness had a 1.96 times higher adjusted prevalence of having two or more GI symptoms (95% CI 1.18–3.26; P<0.01) than those without daytime sleepiness. Similarly, children with teacher-rated sleepiness (yes/no) had a 2.17 times higher prevalence of GI symptoms after adjustment for sex, age, enrollment in the school lunch program, medication use, and anxiety T scores ≥60 (95% CI 1.28–3.67; P<0.01).

Neither sleep duration nor snoring characteristics including frequency and intensity, were related to prevalence of GI symptoms. Finally, the sensitivity analyses for missingness in BMI- and height-for-age z-scores did not substantially differ from the complete-case analysis and were not included in the tables.

DISCUSSION

In this community-based sample of urban elementary school children, a significant proportion– about a half – had at least one GI symptom, a fifth had daytime sleepiness or screened positive for SDB; and SDB symptoms were associated with a 2-fold higher prevalence of GI symptoms. In particular, the observed association was driven by daytime sleepiness rather than presence of snoring. The significant overlap between sleep disturbances and GI symptoms should raise awareness of pediatric clinicians and parents alike when encountering children with either of these problems and may guide their approach to evaluation and treatment.

The finding that daytime sleepiness, but not snoring, was associated with GI symptoms carries implications for a much wider pediatric population. Sleepiness- which is the opposite of alertness, or an increased tendency to fall asleep during the day- was observed in 19% of our sample and confirms previous prevalence reports in school aged children 16. Daytime sleepiness usually indicates either short sleep duration or poor quality of sleep (or both) during the nightly sleep period, and may be in part attributed to poor sleep hygiene practices such as consumption of caffeinated beverages or use of electronic media before bedtime 17. In school-aged children, sleepiness has negative consequences for behavior and mood, cognition, attention and concentration, that in turn, limits performance in school and other social settings 4.

The GI symptoms examined in this study – stomachaches, vomiting and nausea, trouble with eating, and bowel problems – are common among school-aged children. Indeed, in a sample of US elementary and middle school students the prevalence of abdominal pain was 38%, 5 and a systematic review that incorporated pediatric data from 11 countries, reported a prevalence of childhood constipation in up to 30% of children 18. High prevalence of GI complaints in school-aged children is a public health concern with demonstrated negative impact on school attendance 19, health-related quality of life 20, and future GI symptoms and anxiety disorders 21. Furthermore, the predictors of GI symptoms in this age group remain poorly understood 22, making treatment and prevention difficult.

Our findings on the association between sleep disturbances and GI symptoms corroborate but also extend previous reports that were limited to children with autism spectrum disorder or to a single sleep disturbance and a single GI disorder. For example, a link between obstructive sleep apnea and gastroesophageal reflux disease has been observed in a small sample of Polish children aged 2 to 16 years 8. Further, in a Chinese sample of adolescents, those with poor sleep were almost twice as likely to have irritable bowel syndrome as those with adequate sleep 23. Short sleep duration (<7 hours) has been associated with constipation in Hong Kong elementary school children 24, and one US study linked insomnia with gastric regurgitation 9. Nonetheless, our community-based study associates multiple common sleep disturbances with several prevalent GI symptoms, thus allowing generalizability of these findings on a much broader scale. In contrast to the prior literature, we found that sleep duration was not associated with prevalence of GI symptoms. This discrepancy may be attributed to measurement error of average bedtimes and wake times.

Mechanistic pathways linking sleep disturbances and GI symptoms are plausibly bi-directional. The pathway from sleep disturbances to GI symptoms is supported by the finding that sleep disturbances are associated with weakened immunity 25, which leads to higher chance of infections and GI symptoms. Research among adult shift workers also adds insight; as circadian rhythm disturbances in a Michigan sample of nurses with rotating shifts have been associated with a higher prevalence of abdominal pain and IBS 26. Finally, although not necessarily specific to GI-related pain, one longitudinal study among US adolescents found that lower quality of sleep predicted pain (including abdominal pain) the next day 27. In contrast, GI symptoms at bedtime or during the night could lead to sleep disturbances. 28 Further examination in longitudinal studies is warranted to disentangle the directions. It is particularly relevant to ascertain whether improvements in sleepiness of school-aged children may alleviate the burden of common GI symptoms.

This study has several strengths; first, we used a community-based sample that allows generalizability of the findings to a broader pediatric population; second, we used validated questionnaires for assessing SDB and behavior; finally, we accounted for salient potential confounders including anxiety and medication use. However, this study is not without limitations; first, the cross-sectional design precludes evaluation of the temporality between sleep and GI symptoms. Second, the assessment of GI symptoms was ascertained from the Conners’ scale, and not according to GI-specific Rome III criteria. Finally, the 28% response rate, although similar or better than other urban community-based samples29, may introduce selection bias. However, to examine the potential for selection bias, we compared the distribution of race/ethnicity in our sample with Ypsilanti Census statistics at the time of the survey 30. While we found higher proportions of Caucasians and children with lower socioeconomic status compared to the Ypsilanti Census, these characteristics were not associated with GI symptoms, and suggesting these response patterns did not bias the estimates.

In summary, the observed association of sleepiness and GI problems highlight the co-occurrence of two common childhood complaints and may prove useful to clinicians and parents to identify children with multiple problems that can then be treated or managed. Children who display frequent GI symptoms should also be asked about their sleep hygiene and daytime sleepiness, and vice versa. As predictors of common GI problems in children remain poorly understood, our findings would motivate further inquiries into the potential role of sleep disturbances and the directionality of the association.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding source: This work was supported by NIH/NCRR/University of Michigan Medical School Clinical Research Initiatives Program [5 M01 RR000042]. Dr. Jansen is funded through a T32 grant from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases [5T32DK071212-12]. Dr. Dunietz is supported by a T32 grant from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke [NIH/NINDS T32 NS007222]. Dr. O’Brien is supported in part by grants from the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute [R01 HL105999] and the American Sleep Medicine Foundation.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: None of the authors have any conflicts of interest with the work presented.

Data: Data will be provided upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1.Owens JA, Spirito A, McGuinn M, Nobile C. Sleep habits and sleep disturbance in elementary school-aged children. J Dev Behav Pediatr February 2000;21(1):27–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Owens J Classification and epidemiology of childhood sleep disorders. Prim Care September 2008;35(3):533–546, vii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lumeng JC, Chervin RD. Epidemiology of pediatric obstructive sleep apnea. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2008;5(2):242–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shochat T, Cohen-Zion M, Tzischinsky O. Functional consequences of inadequate sleep in adolescents: a systematic review. Sleep Med Rev February 2014;18(1):75–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saps M, Seshadri R, Sztainberg M, Schaffer G, Marshall BM, Di Lorenzo C. A prospective school-based study of abdominal pain and other common somatic complaints in children. J Pediatr March 2009;154(3):322–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Swain MS, Henschke N, Kamper SJ, Gobina I, Ottova-Jordan V, Maher CG. An international survey of pain in adolescents. BMC Public Health. May 13 2014;14:447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klukowski M, Wasilewska J, Lebensztejn D. Sleep and gastrointestinal disturbances in autism spectrum disorder in children. Dev Period Med Apr-Jun 2015;19(2):157–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wasilewska J, Kaczmarski M, Debkowska K. Obstructive hypopnea and gastroesophageal reflux as factors associated with residual obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol May 2011;75(5):657–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singareddy R, Moole S, Calhoun S, et al. Medical complaints are more common in young school-aged children with parent reported insomnia symptoms. J Clin Sleep Med December 15 2009;5(6):549–553. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Brien LM, Lucas NH, Felt BT, et al. Aggressive behavior, bullying, snoring, and sleepiness in schoolchildren. Sleep Med August 2011;12(7):652–658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hirshkowitz M, Whiton K, Albert SM, et al. National Sleep Foundation’s updated sleep duration recommendations: final report. Sleep Health. 2015;1(4):233–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paruthi S, Brooks LJ, D’Ambrosio C, et al. Consensus Statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine on the Recommended Amount of Sleep for Healthy Children: Methodology and Discussion. J Clin Sleep Med 2016;12(11):1549–1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chervin RD, Hedger K, Dillon JE, Pituch KJ. Pediatric sleep questionnaire (PSQ): validity and reliability of scales for sleep-disordered breathing, snoring, sleepiness, and behavioral problems. Sleep Med 2000;1(1):21–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Conners KC. Manual for Conners Rating Scales: Instruments for Use with Children and Adolescents. Multi Health Systems; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Grummer-Strawn LM, et al. CDC growth charts: United States. Advance Data. 2000(314):1–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blader JC, Koplewicz HS, Abikoff H, Foley C. Sleep problems of elementary school children. A community survey. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med May 1997;151(5):473–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hale L, Guan S. Screen time and sleep among school-aged children and adolescents: a systematic literature review. Sleep Med Rev June 2015;21:50–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van den Berg MM, Benninga MA, Di Lorenzo C. Epidemiology of childhood constipation: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. October 2006;101(10):2401–2409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roth-Isigkeit A, Thyen U, Stoven H, Schwarzenberger J, Schmucker P. Pain among children and adolescents: restrictions in daily living and triggering factors. Pediatrics. February 2005;115(2):e152–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petersen S, Hagglof BL, Bergstrom EI. Impaired health-related quality of life in children with recurrent pain. Pediatrics October 2009;124(4):e759–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramchandani PG, Fazel M, Stein A, Wiles N, Hotopf M. The impact of recurrent abdominal pain: predictors of outcome in a large population cohort. Acta Paediatr May 2007;96(5):697–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spee LA, Lisman-van Leeuwen Y, Benninga MA, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, Kollen BJ, Berger MY. Predictors of chronic abdominal pain affecting the well-being of children in primary care. Ann Fam Med March 2015;13(2):158–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou HQ, Yao M, Chen GY, Ding XD, Chen YP, Li DG. Functional gastrointestinal disorders among adolescents with poor sleep: a school-based study in Shanghai, China. Sleep Breath. December 2012;16(4):1211–1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tam YH, Li AM, So HK, et al. Socioenvironmental factors associated with constipation in Hong Kong children and Rome III criteria. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr July 2012;55(1):56–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bryant PA, Trinder J, Curtis N. Sick and tired: Does sleep have a vital role in the immune system? Nat Rev Immunol June 2004;4(6):457–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nojkov B, Rubenstein JH, Chey WD, Hoogerwerf WA. The impact of rotating shift work on the prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome in nurses. Am J Gastroenterol. April 2010;105(4):842–847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lewandowski AS, Palermo TM, De la Motte S, Fu R. Temporal daily associations between pain and sleep in adolescents with chronic pain versus healthy adolescents. Pain. October 2010;151(1):220–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lewin DS, Dahl RE. Importance of sleep in the management of pediatric pain. J Dev Behav Pediatr August 1999;20(4):244–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.MacGregor E, McNamara JR. Comparison of return procedures involving mailed versus student-delivered parental consent forms. Psychological Reports. 1995;77(3_suppl):1113–1114. [Google Scholar]

- 30.SchoolDataDirect 2009.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.