SUMMARY

Objective:

To compare key intracellular redox-regulated signaling pathways in chondrocytes derived from knee joint femoral cartilage and ankle joint talar cartilage in order to determine if differences exist that might contribute to the lower prevalence of ankle osteoarthritis (OA).

Methods:

Femoral and talar chondrocytes were treated with H2O2 generators (menadione or 2-3-dimethoxy-1,4-napthoquinone (DMNQ), fragments of fibronectin (FN-f)) to stimulate MAP kinase signaling (MAPK), or with IGF-1 to stimulate the Akt signaling pathway. Hyperoxidation of the peroxiredoxins, used as a measure of redox status, and phosphorylation of proteins pertinent to MAPK (p38, ERK, JNK, c-Jun) and Akt (Akt, PRAS40) signaling cascades were detected by immunoblotting.

Results:

Treatment of femoral and talar chondrocytes with menadione, DMNQ or FN-f led to a time dependent increase in extracellular-regulated kinase (ERK) and p38 phosphorylation. DMNQ and FN-f stimulation enhanced phosphorylation of JNK and its downstream substrate, c-Jun. Menadione treatment did not stimulate JNK activity but hyperoxidized the peroxiredoxins and inhibited IGF-1-induced Akt activation. In all experiments, chondrocytes derived from the femur and talar joints displayed comparable MAP kinase responses after treatment with various catabolic stimuli, as well as similar Akt signaling responses after IGF-1 treatment.

Conclusions:

MAP kinase and Akt signaling in response to factors that modulate the intracellular redox status were similar in chondrocytes from knee and ankle joints suggesting that redox signaling differences do not explain differences in OA prevalence. Talar chondrocytes, when isolated from their native matrix, can be used to examine redox-regulated cell signaling events relevant to OA in either joint.

Keywords: Redox signaling, MAP kinase, Oxidative stress, Osteoarthritis

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a major cause of disability worldwide, and represents a significant individual and socioeconomic burden. The susceptibility to OA appears to differ amongst joints1,2. Whereas the development of symptomatic knee OA is multifactorial, being associated with increasing age, obesity, joint injury, genetics and gender3, the risk factors for symptomatic ankle OA are primarily associated with prior joint injury4. The prevalence of ankle OA is much lower than that of the knee and is diagnosed in around 1% of the population4. Symptomatic knee OA is diagnosed in around 9% of the US population at age 60 years, which rises to approximately 15% of non-obese individuals by 85 years. In obese individuals, this number increases to 32%3. The difference in the prevalence of OA between the knee and ankle has led some investigators to suggest differences at the level of the chondrocyte may be a contributing factor5.

An important mechanism contributing to OA development and progression is an imbalance between anabolic and catabolic signaling activities that result in enhanced matrix degradation and cell death6–8. One important family of intracellular signaling proteins pertinent to OA pathogenesis are the MAP kinases. Primarily consisting of p38, extracellular-regulated kinase (ERK) and c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (or stress activated protein kinase) (JNK), these kinases are upregulated in OA tissues and are associated with pro-catabolic signaling that contributes to the production of matrix degrading enzymes, such as MMP-13, and activation of pro-death pathways7,8. The enhanced catabolic signaling observed in aging and OA is associated with a decline in anabolic signal transduction9. Although activation of the IGF-1/Akt pathway stimulates cartilage matrix synthesis and promotes chondrocyte survival10,11, Akt signaling is also sensitive to age-associated oxidative stress- induced inhibition9,11 which could significantly alter chondrocyte and cartilage integrity to promote OA.

In an attempt to explain the differences in OA prevalence in the knee and ankle joints, several reports have chosen to analyse matrix composition and the biomechanical properties of cartilage and chondrocytes derived from the femur and talus. Comparative analyses demonstrate that mean cell density12, as well as proteogly can and collagen synthesis rates, are greater in chondrocytes derived from the talus when compared to the femur1,12,13. In addition, the water content, hydraulic permeability and energy dissipation have been observed to be lower in talar chondrocytes compared to femur chondrocytes13. Femur and talar chondrocytes have been shown to display comparable reductions in GAG content and collagen and proteoglycan synthesis rates after stimulation with the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1β in one study14, while another study demonstrated enhanced IL-1β-induced proteoglycan loss and an increased abundance of aggrecanase and matrix metalloprotease neoepitopes in femoral cartilage explants when compared to talar cartilage explants1. The observed biomechanical and biochemical differences between femur and talar chondrocytes, as well the reported differences in cartilage degradation and assembly in femur and talus cartilage lesions could, in part, account for differences in OA prevalence in the knee and ankle joints.

An imbalance in reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and antioxidant capacity of the cell contributes an increase in oxidative stress conditions7,8. Oxidative stress can disturb anabolic and catabolic cell signal transduction and contribute to the pathogenesis of OA6,9,11,15,16. Various inducers of ROS can stimulate pro-catabolic MAP kinase signaling and inhibit IGF-1 induced Akt signaling resulting in reduced proteoglycan synthesis9,11 and enhance chondrocyte death15 in talar chondrocytes. Although MMP-13 and MMP-3 release in response to ROS generated by fragments of fibronectin (FN-f) is comparable between femoral and talar chondrocytes17,18, femoral chondrocytes have been found to be more sensitive to FN-f-induced proteoglycan loss17,19 and display enhanced NITEGE neoepitope levels, indicative of increased aggrecan degradative products19. In cartilage plugs with evidence of early lesion formation, knee cartilage also appears to display diminished markers of matrix synthesis and upregulation of collagen degradation markers when compared to early lesions evident in ankle cartilage plugs20.

There is a lack of data comparing the effects of anabolic and catabolic stimuli to regulate MAP kinase and Akt signaling path-ways in knee and ankle chondrocytes. For the current study, we selected various stimuli with which to treat chondrocytes and assess MAP kinase and IGF-1-mediated Akt signaling in the context of studying redox signaling. We chose to treat cells with 2-methyl-1,4-napthoquinone (menadione) based on our recent findings that menadione, which is a redox cycling oxidant, generates high levels of H2O2 that result in oxidative stress conditions associated with activation of p38 MAP kinase signaling and inhibition of IGF-1 induced Akt signaling that in turn promotes cell death in talar chondrocytes15. Chondrocytes were also treated with 2-3-dimethoxy-1,4-napthoquinone (DMNQ), another redox cycler which has been shown to generate H2O2 and stimulate MAP kinase signaling21–23. The effect of treatment with FN-f was also examined. FN-f have been identified in OA cartilage and synovial fluid and have been shown to activate cartilage matrix degradation by stimulation of MAP kinase pathways16,24–27 that requires the presence of ROS16,28. To examine pro-anabolic cell signaling responses that are modulated by ROS, we chose to treat cells with IGF-1 due to our prior findings demonstrating that IGF-1 stimulates cartilage matrix synthesis and promotes chondrocyte survival through activation of the Akt signaling pathway in talar chon- drocytes11,29,30 an effect which is inhibited by ROS9,15.

Methods

Antibodies and reagents

Antibodies to phospho-p38 (Thr180/Tyr182), total-P38, phospho-ERK (Thr202/Tyr204), total-ERK, phospho-JNK (Thr183/Tyr185), total JNK, phospho-c-Jun (Ser73), total-c-Jun, phospho-Akt (Ser473), total-Akt, phospho-PRAS40 (Thr246), total PRAS40 and β-tubulin were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. Antibodies to Prx-SO2/3 were purchased from Abcam. Menadione, DMNQ, and N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich. IGF-1 was purchased from Austral Biologicals. For experiments using FN-f, endotoxin-free human recombinant FN-f (domains 7e10 of native fibronectin (42kd)) was produced using a plasmid expression construct (kind gift from Dr. Harold Erickson (Duke University, Durham, NC)) as described11,31. Standard lysis buffer was purchased from Cell Signaling Technologies (#9803) and was comprised of 20 mM TriseHCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM Na2EDTA, 1 Mm EGTA, 1% Triton, 2.5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 μg/ml leupeptin).

Human primary chondrocyte isolation and culture

Full depth human articular cartilage was obtained from the tibiofemoral (femur) and talocrural (talus) joints of the same tissue donors (matched pairs) through collaboration with the Gift of Hope Organ and Tissue Donor Network (Itasca, IL). Cartilage donors had no known joint problems or history of arthritis. A modified version of the 5-point Collins grading system was used to identify macroscopic degenerative changes to cartilage surfaces32 and only tissues graded 0e3 were used in this study (femur range 0e3, talar range 1e3) (Table I). When removing the cartilage from the joint surface, we avoided areas that exhibited any sign of degenerative change. Donor ages ranged from 36 to 85 yrs (av age, 71.85 ± 12.12) (5 female and 9 male donors) (Table I). Chondrocytes were isolated and cultured as described10. Experiments were performed on chondrocyte monolayers upon 80–90% confluency. Chondrocytes were incubated in serum-free conditions overnight prior to experimental incubations. For each individual experiment (biological replicate), cell signaling responses were compared using chondrocytes isolated from the femur and talus of the same donor. Use of human tissue was in agreement with both Rush University Medical Center and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Institutional Review Boards.

Table I.

Gender, age distribution, and Collins grade of chondrocytes derived from the femur and talus of human tissue donors

| Gender | Age (years) | Collins grade: Femur | Collins grade: Talus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 68 | 3 | 1 |

| Female | 77 | 3 | 1 |

| Female | 66 | 2.5 | 1 |

| Female | 71 | 3 | 2.5 |

| Female | 85 | 3 | 1.5 |

| Male | 36 | 0 | 1 |

| Male | 75 | 3 | 1.5 |

| Male | 76 | 3 | 1 |

| Male | 61 | 2.5 | 1 |

| Male | 77 | 3 | 1 |

| Male | 82 | 2 | 2 |

| Male | 76 | 3 | 2.5 |

| Male | 80 | 2.5 | 1 |

| Male | 76 | 2 | 1 |

| Range | 36–85 yrs | 0–3 | 1–3 |

| Mean 士 SD | 71.85 yrs ± 12.12 | 2.53 ± 0.81 | 1.35 ± 0.56 |

Analysis of chondrocyte intracellular signaling

Chondrocyte monolayers were treated with 25 μM menadione, 25 μM DMNQ, 1 μM FN-f or 50 ng/ml IGF-1 for the indicated times. For co-treatment experiments with menadione and IGF-1, chon- drocytes were treated with 25 μM menadione (30 min) prior to IGF-1 stimulation (30 min). After experimental incubations, chondrocyte monolayers were rinsed in ice cold PBS and lysed in standard lysis buffer under gentle agitation for 30 min (4°C) prior to centrifugation at 13,000 rpm (10 min) to remove insoluble protein fractions. Quantification of total protein was determined using the Pierce Micro BCA kit (Thermo Scientific). Cell lysates (10 μg protein/sample) were then combined with 10% β-mercaptoethanol and 5X loading buffer (reducing conditions) and immunoblotted as previously described33. Analyses of phosphoproteins were identified using phospho-specific antibodies. Blots were then stripped and probed with antibodies to the total protein for loading controls, with the exception of phospho-c-Jun blots, which were normalized to β-tubulin. In order to detect hyperoxidized Prxs as a marker of oxidative stress, cells were treated with menadione for the indicated times, washed twice in PBS and incubated for 10 min prior to lysis in an alkylating buffer (40 mM HEPES, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM EGTA, 200 units/ml catalase, PMSF and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail 2 (pH7.4)) containing 100 mM NEM. Pre-treatment with NEM promotes the alkylation of reduced thiols and abolishes artificial Prx oxidation that may occur as an artefact of cell lysis as previously described15,34, lysates were then harvested in standard lysis buffer containing 100 mM NEM and immunoblotting was performed under reducing conditions. An antibody to PrxSO2/3 was used to identify hyperoxidized forms of Prx 1–4 as previously described15,34. Blots were stripped and reprobed with antibodies to β-tubulin as a loading control.

Statistical analysis

Densitometric analysis of immunoblots was carried out in ImageJ version 1.48 and data were graphed using GraphPad Prism version 7.01 (GraphPad Software, Inc.). Exact biological replicates for each experiment are provided in the figure legends. Results are presented as mean values normalized to their representative loading control with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Statistical analysis was performed using SAS v 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). All tests were performed based on a 0.05 level of significance. Normal distribution of the data was confirmed using ShapiroeWilk tests. Paired t-tests were used to determine mean differences, with 95% CI’s between treated vs untreated samples. To understand whether differences between treated and control values vary between talus and femur, we first calculated the differences between treated and control values from the same sample; then we applied paired t-tests to compare these differences between joints. Normality checks were carried out on the differences between joints, which were approximately normally distributed. Results are presented as mean differences and 95% CI’s.

Results

Femur and talar chondrocytes isolated from the same human donors display similar levels of ROS-induced PrxSO2/3 formation and MAP kinase signaling responses

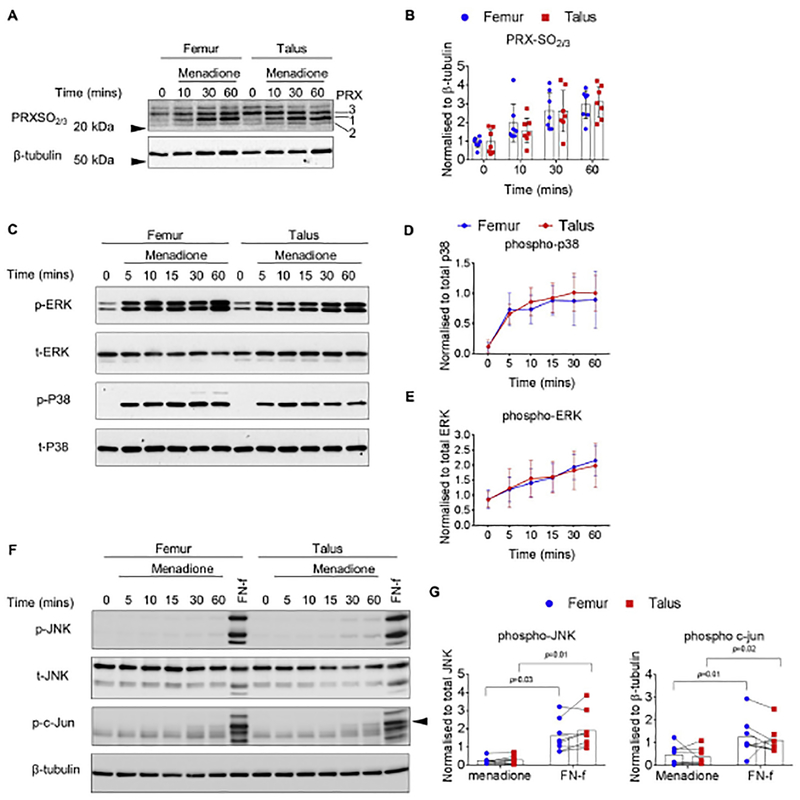

Human chondrocytes isolated from the femur and talus of the same donors were treated with menadione for the indicated times to induce oxidative stress as we have previously described15. Immunoblotting was performed on cell lysates with an antibody that specifically detects the hyperoxidized (Prx-SO2 and Prx-SO3) forms of Prx 1e4, as a marker of oxidative stress. In femur and talus chondrocyte cultures, treatment with menadione induced a significant increase in PrxSO2/3 formation at 30 and 60 min when compared to untreated control values (Fig. 1(A) and (B), supplementary Table I). The increased PrxSO2/3 formation over time was similar between femur and talar chondrocytes and no statistically significant differences were observed at 10 min (mean, 0.46; 95%CI, (−1.30, 0.39)), 30 min (mean, −0.01; 95%CI, (−1.07, 1.04)) or 60 min (mean, 0.34; 95%CI, (−0.10, 0.77)) [Fig. 1(A) and (B)]. Next, we assessed the ability of menadione to stimulate MAP kinase phosphorylation in femur and talar chondrocytes. In agreement with our previous findings15, menadione treatment led to an increase in both ERK and p38 phosphorylation over the time course, which was maximal at 60 min (Fig. 1(C), (D),(E), supplementary Table II). Menadione-induced phosphorylation of ERK and p38 was comparable between femur and talar chondrocytes at all time points studied (Table II). Menadione induced very weak phosphorylation of JNK and its downstream substrate c-Jun in both femur and talar chondrocytes (Fig. 1(F) and (G), supplementary Table III). We have previously identified FN-f as a strong inducer of the JNK pathway that was inhibited in the presence of dimedone suggesting oxidation of protein thiols to sulfenic acids was required16. No differences between femur and talar chondrocytes in JNK (mean, 0.30; 95%CI, (−0.11, 0.71)) or c-Jun (mean, −0.06; 95%CI, (−0.65, 0.54)) were observed.

Fig. 1.

Effect of menadione on Prx hyperoxidation and MAP kinase signaling in human femur and talar chondrocytes. Confluent human articular chondrocytes isolated from the femur and tali of the same donor were treated for 0e60 min with menadione (25 μM). (A) Representative immunoblots from n = 7 independent donors showing PrxSO2/3 formation in response to menadione treatment. (B) Densitometric analysis from PrxSO2/3 immunoblots from n = 7 independent donors. PrxSO2/3 bands were normalized to β-tubulin and data is presented as mean values ± 95% confidence Intervals (CI). No significant differences between femoral and talar chondrocytes were observed at any time point. (C) Chondrocytes were treated for 0–60 min with menadione (25 μM) and harvested lysates were subjected to immunoblotting with antibodies to phosphorylated p38 or ERK. Representative immunoblots from n = 9 independent donors (D-E) Densitometric analysis showing menadione-induced phosphorylation of p38 and ERK. Phosphorylated bands were normalized to total protein as loading controls and presented as mean values ± 95% CI. No significant differences between femoral and talar chondrocytes were observed at any time point. (F) Cell lysates were also immunoblotted and probed with antibodies for JNK and c-Jun. Chondrocytes were treated with FN-f (1 μM) for 60 min for comparison. Representative immunoblots from n = 8 independent donors. Arrow on c-Jun blots indicates an electrophoretic shift of the c-Jun monomer, which is indicative of serine and threonine phosphorylation (maximal phosphorylation). (G) Densitometric analysis comparing the effects of menadione and FN-f to phosphorylate JNK and c-Jun at 60 min. Data are presented as mean values ± 95% CI comparing menadione treated cells to FN-f treated cells at 60 min. Significant increases in FN-f-induced phosphorylation of JNK and c-Jun were observed when compared to menadione treatment in both the femur and talus. No significant differences between femoral and talar chondrocytes were observed at any time point. Mean differences, 95% CI and P-values comparing the effects of menadione to hyperoxidize the Prxs and phosphorylate MAP kinases in femur and talus chondrocytes over time can be found in supplementary Table I–III.

Table II.

Effect of menadione on p38 and ERK MAP kinase phosphorylation in femur compared to talar chondrocytes

| Time (min) | Talus vs Femur pERK | Talus vs Femur p-P38 |

|---|---|---|

| Time point | Statistical test | |

| Paired t-test | Paired t-test | |

| 5 min | 0.06 (−0.31, 0.42) P = 0.72 | −0.08 (−0.25, 0.09) P = 0.31 |

| 10 min | 0.16 (−0.42, 0.74) P = 0.54 | 0.12 (−0.10, 0.33) P = 0.24 |

| 15 min | 0.04 (−0.30, 0.38) P = 0.78 | 0.03 (−0.09, 0.16) P = 0.55 |

| 30 min | −0.09 (−0.41, 0.22) P = 0.51 | 0.13 (−0.14, 0.40) P = 0.29 |

| 60 min | −0.16 (−0.56, 0.25) P = 0.40 | 0.11 (−0.21, 0.42) P = 0.46 |

Data presented shows mean differences, 95% CI (in parentheses) and P-values for t- tests between differences in femur and differences in talus at the corresponding time point.

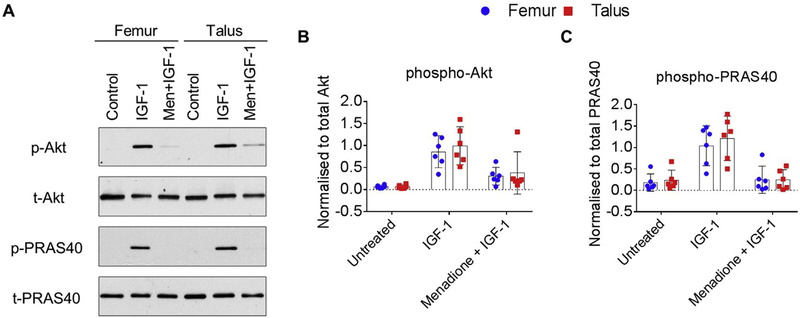

ROS-induced inhibition of IGF-1 stimulated Akt activation is similar between femur and talar chondrocytes isolated from the same human donors

Having previously identified that menadione-induced oxidative stress led to inhibition of IGF-1-stimulated Akt signaling in talar chondrocytes15, our next aim was to compare this response with donor matched chondrocytes derived from the femur. Stimulation of femur and talar chondrocytes with IGF-1 led to a significant increase in Akt phosphorylation and phosphorylation of its down- stream substrate and marker of activation, PRAS40, when compared to control (Fig. 2(A)–(C), and supplementary Table IV). No differences between femur and talar chondrocytes in the ability of IGF-1 to phosphorylate Akt (mean difference, 0.27; 95%CI, (−0.14,0.68)) or PRAS 40 (mean difference, 0.32; 95%CI, (−0.22, 0.87)) were observed. Pretreatment of femur and talar chondrocytes with menadione, prior to stimulation with IGF-1, significantly inhibited Akt and PRAS40 phosphorylation [Fig. 2(A)–(C)]. The effect of menadione to inhibit IGF-1 induced Akt and PRAS40 phosphorylation did not differ between femur and talar chondrocytes (Akt mean difference, 0.00; 95%CI, (−0.36, 0.36); PRAS40 mean difference, −0.40; 95%CI, (−1.02, 0.23)).

Fig. 2.

Effect of menadione on IGF-1 signaling in human femur and talar chondrocytes. Confluent human articular chondrocytes isolated from the femur and talus of the same donor were treated for 30 min with IGF-1 (50 ng/ml) or pre-treated with menadione (25 μM) for 30 min prior to IGF-1 treatment (30 min). (A) Representative immunoblots from n = 6 independent donors showing the phosphorylation of Akt and its downstream marker of activation, PRAS40. (B-C) Densitometric analysis showing phosphorylation of Akt and pPRAS40. Phosphorylated bands were normalized to total protein as loading controls and presented as mean values ± 95% CI (n = 6).

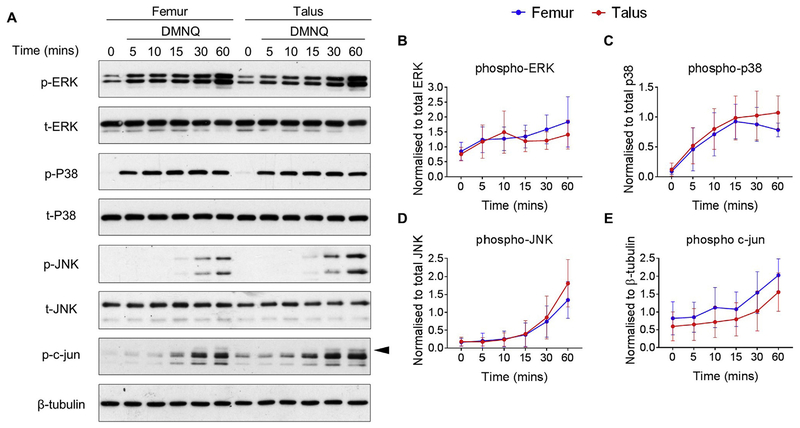

Treatment of femur and talar chondrocytes with the redox cycling agent, DMNQ, generates similar MAP kinase signaling responses

To further examine the role of MAP kinase stimulation in response to redox-regulated catabolic stimulation, we treated cells with DMNQ, which, similarly to menadione is a redox cycling agent. Although DMNQ is less electrophilic than menadione and appears to cause less cell death after short term exposure, DMNQ has been shown to increase ROS levels22 and activate MAP kinase signaling in epithelial cells21. We therefore hypothesized that DMNQ treatment would lead to phosphorylation of the MAP kinases in chondrocytes. Treatment of femur and talar chondrocytes with 25 μM DMNQ led to a significant increase in ERK phosphorylation, which peaked at 60 min in both femur and talar chondrocytes (Fig. 3(A) and (B), and supplementary Table V). DMNQ treatment led to significant phosphorylation of p38 within 5 min, an effect which was sustained over the 60 min time course (Fig. 3(A), (C), and supplementary Table V). DMNQ stimulated strong phosphorylation of JNK and c-Jun at 60 min (Fig. 3(C) and (D), supplementary Table V). Responses in femur and talar chondrocytes were comparable for all the MAP kinases (Table III) with the exception of p38 at 60 min (mean, 0.26; 95%CI, 0.10, 0.42).

Fig. 3.

Effect of DMNQ on MAP kinase signaling in human femur and talar chondrocytes. Confluent human articular chondrocytes isolated from the femur and talus of the same donor were treated for 0–60 min with DMNQ (25 μM). (A) Representative immunoblots from n = 8 independent donors showing MAP kinase phosphorylation. (B-E) Densitometric analysis showing phosphorylation of p38, ERK, JNK and c-Jun. Phosphorylation of proteins were normalized to total protein as a loading control with the exception of c-Jun which was normalized to β-tubulin and presented as mean values ± 95% CI (n = 8). Mean differences, 95% CI and P-values comparing the effects of DMNQ to phosphorylate MAP kinase phosphorylation in femur and talus chondrocytes over time can be found in supplementary Table V.

Table III.

Effect of DMNQ on MAP kinase phosphorylation between femur and talar chondrocytes

| Time (min) | Talus vs Femur pERK | Talus vs Femur p-P38 | Talus vs Femur p-JNK | Talus vs Femur p-c-Jun |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time point | Statistical test | |||

| Paired t-test | Paired t-test | Paired t-test | Paired t-test | |

| 5 min | −0.03 (−0.34, 0.29) P = 0.85 | 0.03 (−0.12, 0.19) P = 0.64 | −0.04 (−0.15, 0.06) P = 0.36 | 0.02 (−0.23, 0.28) P = 0.85 |

| 10 min | −0.31 (−0.86, 0.23) P = 0.22 | 0.06 (−0.24, 0.36) P = 0.65 | −0.03 (−0.10, 0.04) P = 0.35 | −0.18 (−0.63, 0.27) P = 0.37 |

| 15 min | −0.06 (−0.32, 0.44) P = 0.71 | 0.03 (−0.09, 0.15) P = 0.55 | 0.00 (−0.11, 0.11) P = 0.93 | −0.06 (−0.23, 0.11) P = 0.45 |

| 30 min | 0.29 (—0.01, 0.58) P = 0.06 | 0.12 (−0.04, 0.28) P = 0.12 | 0.10 (−0.19, 0.38) P = 0.45 | −0.29 (−0.82, 0.23) P = 0.23 |

| 60 min | 0.34 (−0.32, 0.99) P = 0.26 | 0.26 (0.10, 0.42) P=0.01 | 0.44 (−0.32, 1.21) P = 0.21 | −0.25 (−0.96, 0.46) P = 0.44 |

Data presented shows mean differences, 95% CI (in parentheses) and P-values for t-tests between differences in femur and differences in talus at the corresponding time point.

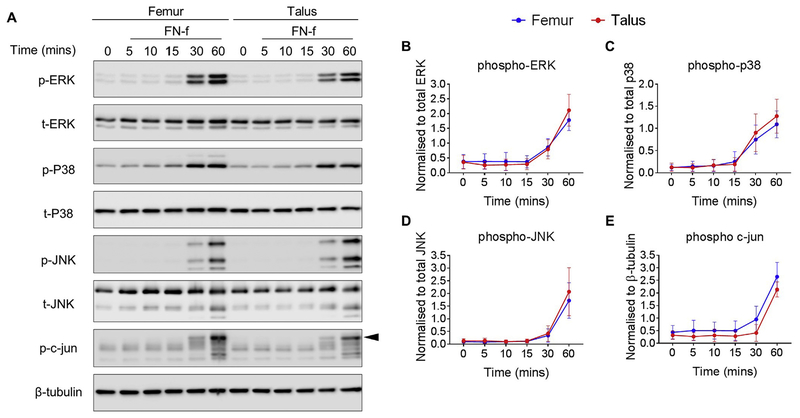

FN-f treatment stimulates similar MAP kinase signaling responses in femur and talar chondrocytes isolated from the same human donors

Previous data suggests that chondrocytes derived from human femur and talar cartilage display similar levels of MMP-1318 and MMP-3 release into cell culture media as well as comparable proteoglycan degradation rates17 in response to stimulation with FN-f. As a result, we decided to compare the effect of FN-f-induced MAP kinase phosphorylation in femur and talar chondrocyte cultures. FN-f stimulation led to a significant increase in ERK and p38 phosphorylation within 60 min and 30 min respectively (Fig. 4(A)–(C), and supplementary Table VI). FN-f -induced phosphorylation of ERK and p38 were comparable between femur and talar chondrocytes at all-time points (Fig. 4(A)–(C), Table IV). Treatment with FN-f caused a significant increase in JNK phosphorylation at 60 min in both talar and femur chondrocytes in accordance with phosphorylation of its downstream substrate and marker of activity, c-Jun (supplementary Table VI). The responses were similar in talar and femur (Fig. 4(A), (D), (E), Table IV).

Fig. 4.

Effect of FN-f on MAP kinase signaling in human femur and talar chondrocytes. Confluent human articular chondrocytes isolated from the femur and talar of the same donor were treated for 0–60 min with FN-f (1 μM). (A) Representative immunoblots from n = 7 independent donors showing MAP kinase phosphorylation. Arrow on c-Jun blots indicates electrophoretic shift of the c-Jun monomer, which is indicative of complete serine and threonine phosphorylation (maximal phosphorylation). (B-E) Densitometric analysis showing phosphorylation of p38, ERK, JNK and c-Jun. Phosphorylated bands were normalized to total protein as loading controls and presented as mean values with 95% CI. (n = 7). No significant differences between femoral and talar chondrocytes were observed at any time point. Mean differences, 95% CI and P-values comparing the effects of FN-f to phosphorylate MAP kinase phosphorylation in femur and talus chondrocytes over time can be found in supplementary Table VI.

Table IV.

Effect of FN-f on MAP kinase phosphorylation in femur compared to talar chondrocytes

| Time (min) | Talus vs Femur pERK | Talus vs Femur p-P38 | Talus vs Femur p-JNK | Talus vs Femur p-c-Jun |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time point | Statistical test | |||

| Paired t-test | Paired t-test | Paired t-test | Paired t-test | |

| 5 min | −0.10(−0.25, 0.05) P = 0.16 | −0.04 (−0.09, 0.02) P = 0.15 | 0.01 (−0.03, 0.05) P = 0.50 | −0.12 −0.31,0.08) P = 0.19 |

| 10 min | −0.08 (−0.39, 0.22) P = 0.52 | 0.00(−0.12, 0.13) P = 0.94 | −0.03 (−0.07, 0.01) P = 0.11 | −0.07 −0.36, 0.22) P = 0.58 |

| 15 min | −0.06 (−0.44, 0.33) P = 0.72 | −0.07 (−0.24, 0.11) P = 0.41 | −0.03 (−0.07, 0.01) P = 0.13 | −0.10 −0.32, 0.12) P = 0.31 |

| 30 min | −0.04 (−0.51, 0.43) P = 0.83 | 0.15 (−0.12, 0.41)P = 0.22 | 0.05 (−0.28, 0.37) P = 0.75 | −0.42 一0.86, 0.03) P = 0.06 |

| 60 min | 0.36 (−0.06, 0.78) P = 0.08 | 0.18 (0.03, 0.33) P=0.03 | 0.31 (−0.33, 0.95) P = 0.28 | −0.39 −0.81,0.04) P = 0.07 |

Data presented shows mean differences, 95% CI (in parentheses) and P-values for t-tests between differences in femur and differences in talus at the corresponding time point.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate cell signal transduction in femur and talar chondrocytes. We chose to specifically focus on MAP kinase and Akt signaling responses due to cumulative evidence demonstrating that disturbances in these signaling pathways can lead to chondrocyte dysfunction which may contribute to OA development and progression. Our previous findings demonstrate that these cell signaling pathways are at least in part, regulated by the redox status of the cell7. Our major finding here is that isolated femur and ankle chondrocytes display very similar catabolic and anabolic signaling responses after stimulation with compounds that have been shown to alter intracellular ROS levels. These findings suggest that differences in the prevalence of knee and ankle OA cannot be attributed to differences in these redox sensitive pathways. Activation of MAP kinase signaling or inhibition of Akt signaling, therefore, may contribute to OA development and progression in either joint.

An imbalance between anabolic and catabolic cell signaling activities contributes to cartilage degradation and enhances OA development and progression7,35, but there remains a severe lack of data examining the cell signaling events that may lead to compromised cartilage homeostasis and matrix degradation in femur and talar chondrocytes. Our studies were conducted in using isolated human chondrocytes rather than explants in order to remove the effects of the extracellular matrix and study differences at the level of the cell. It is possible that cells within talar and femur explants could have responded differently from isolated cells. However, analysis of time-sensitive cell signaling events including protein phosphorylation and oxidation cannot be reliably measured in cartilage explants due to the need for rapid cell lysis and extraction of signaling proteins after experimental treatments. Also, the high variation in cell number from explant to explant can potentially confound interpretation and analysis of such chondrocyte signaling events.

Although increased ROS levels can lead to indiscriminate cellular damage, recent evidence suggests that ROS accumulation can disturb physiological and homeostatic cell signal transduction to compromise cellular integrity. We have previously demonstrated that treatment of chondrocytes with compounds that generate intracellular ROS can activate MAP kinase signaling pathways and inhibit anabolic signaling in talar chondrocytes9,15. We chose to further these findings and examine the role of MAP kinase and IGF-1 signaling in response to various ROS-generating stimuli in femur chondrocytes, and compare these responses to those observed in donor matched talar chondrocytes, to assess if alterations in redox sensitive signaling pathways could explain the differences in knee and ankle OA prevalence.

In the present study, we did not find evidence of biologically significant differences in catabolic and anabolic cell signaling responses between femur and talar chondrocytes after treatment with compounds that have been shown to alter the intracellular redox status, or with the growth factor IGF-1. We first tested the effect of menadione treatment to hyperoxidize the peroxiredoxin (Prx) family of antioxidant enzymes in both femur and talar chondrocytes. Our data demonstrates that menadione treatment led to an increase in global Prx hyperoxidation, which is in accordance with our previous findings in talar chondrocytes15 and demonstrates its ability to generate high levels of oxidative stress. Prx hyperoxidation leads to inhibition of Prx peroxidase activity, which is hypothesised to contribute to increased H2O2-mediated cell signaling events36,37. Recent data from our lab demonstrates that Prx hyperoxidation is associated with increased MAP kinase signaling and chondrocyte cell death15. In agreement with these findings, the current study shows that menadione-induced chondrocyte Prx hyperoxidation correlated with an increase in p38 and ERK phosphorylation in both femur and talar chondrocytes. Conversely however, menadione failed to activate the JNK pathway.

Similarly to menadione, DMNQ is a redox cycling agent that has been shown to generate intracellular ROS levels, including H2O2, capable of depleting glutathione and forming mixed disulfides in rat hepatocytes38 and activating MAP kinase signaling in various cell types21,23,39. We report for the first time, the effect of DMNQ toactivate MAP kinase signaling pathways in human chondrocytes. Treatment with DMNQ led to strong phosphorylation of p38, ERK, JNK and cJun and these responses were overall comparable between femur and talar chondrocytes. The finding that DMNQ led to strong activation of JNK whereas menadione failed to do so, suggests that the MAP kinases can be differentially regulated by ROS-inducing stimuli. The mechanisms behind this differential activation were beyond the scope of the current study but may be worthy of future investigation. The only instance where we observed statistical significance between chondrocytes isolated from the femur and talus was when we analysed phosphorylation of p38 and ERK at later time points after stimulation with DMNQ. We observed marginally lower phosphorylation of ERK at 30 min in talar chondrocytes when compared with those from the femur (P = 0.02) whereas we observed marginally lower p38 phosphorylation in chondrocytes isolated from the femur when compared to talus at 60 min (P = 0.01). The biological significance of these findings at only two time points, although statistically different, may be negligible, especially in light of the vast amount of data presented herein that demonstrates the cell signaling responses in femur and talar chondrocytes are comparable, including p38 and ERK phosphorylation in response to menadione and FN-f.

Our findings with FN-f stimulation mirror those observed with DMNQ whereby p38, ERK, JNK and c-Jun where all highly phosphorylated over the time course studied and no differences between femur and talus where observed. These findings are in agreement with prior data that demonstrates similar levels of FN-f- induced MMP-13 and MMP-3 release in chondrocytes17,18 butdisagree with the work of others which report that femur cartilage explants are more sensitive to FN-f induced proteoglycan loss and aggrecan cleavage when compared to talar cartilage explants19. This leads us to conclude that any differences observed in response to FN-f in the femur and talus chondrocytes are not due to differences in FN-f induced signaling. Phosphorylation of specific MAP kinase isoforms can significantly alter downstream signaling events and cell fate. Although this study did not specifically evaluate each MAP kinase isoform individually, when examining the differences between p44ERK1 and p42ERK2, p46JNK1 and p54JNK2, as well as the hyperoxidation of Prx1, 2, and 3, we did not observe any obvious differences between femur and talus.

The growth factor IGF-1 has been shown to activate pro- anabolic cell signaling pathways but older chondrocytes that display enhanced levels of oxidative stress15,40 have a reduced response to IGF-111,15. Here, we show that femur and talar chondrocytes display comparable Akt activation, as measured by phosphorylation of Akt and its downstream substrate PRAS40, in response to IGF-1 treatment. Pre-treatment with menadione, prior to IGF-1 stimulation led to significant inhibition of Akt activity, an effect which was comparable between both femur and talar chondrocytes. As a result, we suggest that ROS-induced inhibition of pro-anabolic signaling may be a contributing factor leading to chondrocyte dysfunction in both knee and ankle OA.

In summary, our data demonstrate that human, donor matched, femur and talar chondrocytes display comparable MAP kinase and Akt signaling responses after stimulation with various ROS generating stimuli or the growth factor IGF-1. As a result, we conclude that the differences in the prevalence of human knee and ankle OA cannot be attributed to differences in these redox sensitive path-ways and redox-regulated alterations in cell signal transduction may contribute to OA pathogenesis in both joints. Strategies which aim to alter the redox status of the cell, or that target restoration of homeostatic signaling, may be of therapeutic benefit in knee and ankle OA. Additionally, due to the degenerative changes that occur in aging human knee cartilage, our findings suggest that the use of cartilage derived from the talus may represent an alternative source of normal chondrocytes for which to investigate cell signaling changes in the context of OA relevant to both the knee and the ankle.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Gift of Hope Organ and Tissue Donor Network and the donor families for providing normal donor tissue. We also would like to acknowledge Dr. A. Margulis for procurement of human donor tissues.

Financial support

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging (AG044034), National Institute of Arthritis, Musculoskeletal, and Skin Diseases (AR049003 and AR064166) and the American Federation of Aging Research. Human tissue procurement was also supported in part by the Klaus Kuettner Chair of Osteoarthritis Research (SC).

Footnotes

Competing interest statement

The authors have no competing interests to disclose.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2018.12.010.

References

- 1.Eger W, Schumacher BL, Mollenhauer J, Kuettner KE, Cole AA. Human knee and ankle cartilage explants: catabolic differences. J Orthop Res 2002;20:526–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huch K, Kuettner KE, Dieppe P. Osteoarthritis in ankle and knee joints. Semin Arthritis Rheum 1997;26:667–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Losina E, Weinstein AM, Reichmann WM, Burbine SA, Solomon DH, Daigle ME, et al. Lifetime risk and age at diagnosis of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis in the US. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2013;65:703–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valderrabano V, Horisberger M, Russell I, Dougall H, Hintermann B. Etiology of ankle osteoarthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2009;467:1800–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuettner KE, Cole AA. Cartilage degeneration in different human joints. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2005;13:93–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hui W, Young DA, Rowan AD, Xu X, Cawston TE, Proctor CJ. Oxidative changes and signalling pathways are pivotal in initiating age-related changes in articular cartilage. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:449–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Loeser RF, Collins JA, Diekman BO. Ageing and the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2016;12:412–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collins JA, Diekman BO, Loeser RF. Targeting aging for disease modification in osteoarthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2018;30: 101–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Loeser RF, Gandhi U, Long DL, Yin W, Chubinskaya S. Aging and oxidative stress reduce the response of human articular chondrocytes to insulin-like growth factor 1 and osteogenic protein 1. Arthritis Rheum 2014;66:2201–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loeser RF, Pacione CA, Chubinskaya S. The combination of insulin-like growth factor 1 and osteogenic protein 1 promotes increased survival of and matrix synthesis by normal and osteoarthritic human articular chondrocytes. Arthritis Rheum 2003;48:2188–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yin W, Park JI, Loeser RF. Oxidative stress inhibits insulin-like growth factor-I induction of chondrocyte proteoglycan synthesis through differential regulation of phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase-Akt and MEK-ERK MAPK signaling pathways. J Biol Chem 2009;284:31972–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huch K Long-term effects of osteogenic protein-1 on biosynthesis and proliferation of human articular chondrocytes. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2001;19:525–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Treppo S, Koepp H, Quan EC, Cole AA, Kuettner KE, Grodzinsky AJ. Comparison of biomechanical and biochemical properties of cartilage from human knee and ankle pairs. J Orthop Res 2000;18:739–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Candrian C, Bonacina E, Frueh JA, Vonwil D, Dickinson S, Wirz D, et al. Intra-individual comparison of human ankle and knee chondrocytes in vitro: relevance for talar cartilage repair. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2009;17:489–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Collins JA, Wood ST, Nelson KJ, Rowe MA, Carlson CS, Chubinskaya S, et al. Oxidative stress promotes peroxiredoxin hyperoxidation and attenuates pro-survival signaling in aging chondrocytes. J Biol Chem 2016;291:6641–7654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wood ST, Long DL, Reisz JA, Yammani RR, Burke EA, Klomsiri C, et al. Cysteine-mediated redox regulation of cell signaling in chondrocytes stimulated with fibronectin fragments. Arthritis Rheum 2016;68:117–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dang Y, Cole AA, Homandberg GA. Comparison of the catabolic effects of fibronectin fragments in human knee and ankle cartilages. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2003;11:538–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Forsyth CB, Cole A, Murphy G, Bienias JL, Im HJ, Loeser RF Jr. Increased matrix metalloproteinase-13 production with aging by human articular chondrocytes in response to catabolic stimuli. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2005;60:1118–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kang Y, Koepp H, Cole AA, Kuettner KE, Homandberg GA. Cultured human ankle and knee cartilage differ in susceptibility to damage mediated by fibronectin fragments. J Orthop Res 1998;16:551–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aurich M, Squires GR, Reiner A, Mollenhauer JA, Kuettner KE, Poole AR, et al. Differential matrix degradation and turnover in early cartilage lesions of human knee and ankle joints. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:112–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abdelmohsen K, Gerber PA, von Montfort C, Sies H, Klotz LO. Epidermal growth factor receptor is a common mediator of quinone-induced signaling leading to phosphorylation of connexin-43: role of glutathione and tyrosine phosphatases. J Biol Chem 2003;278:38360–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Escobales N, Nunez RE, Jang S, Parodi-Rullan R, Ayala-Pena S, Sacher JR, et al. Mitochondria-targeted ROS scavenger improves post-ischemic recovery of cardiac function and attenuates mitochondrial abnormalities in aged rats. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2014;77:136–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klotz LO, Hou X, Jacob C. 1,4-naphthoquinones: from oxidative damage to cellular and inter-cellular signaling. Molecules 2014;19:14902–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ding L, Guo D, Homandberg GA. Fibronectin fragments mediate matrix metalloproteinase upregulation and cartilage damage through proline rich tyrosine kinase 2, c-src, NF- kappaB and protein kinase Cdelta. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2009;17:1385–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Homandberg GA, Meyers R, Williams JM. Intraarticular injection of fibronectin fragments causes severe depletion of cartilage proteoglycans in vivo. J Rheumatol 1993;20: 1378–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Homandberg GA, Meyers R, Xie DL. Fibronectin fragments cause chondrolysis of bovine articular cartilage slices in culture. J Biol Chem 1992;267:3597–604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Long DL, Willey JS, Loeser RF. Rac1 is required for matrix metalloproteinase 13 production by chondrocytes in response to fibronectin fragments. Arthritis Rheum 2013;65:1561–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Del Carlo M, Schwartz D, Erickson EA, Loeser RF. Endogenous production of reactive oxygen species is required for stimulation of human articular chondrocyte matrix metalloproteinase production by fibronectin fragments. Free Radic Biol Med 2007;42:1350–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greene MA, Loeser RF. Function of the chondrocyte PI-3 kinase-Akt signaling pathway is stimulus dependent. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2015;23:949–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Starkman BG, Cravero JD, Delcarlo M, Loeser RF. IGF-I stimulation of proteoglycan synthesis by chondrocytes requires activation of the PI 3-kinase pathway but not ERK MAPK. Biochem J 2005;389:723–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leahy DJ, Aukhil I, Erickson HP. 2.0 angstrom crystal structure of a four-domain segment of human fibronectin encompassing the RGD loop and synergy region. Cell 1996;84:155–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muehleman C, Chubinskaya S, Cole AA, Noskina Y, Arsenis C, Kuettner KE. William J. Stickel Gold Award. Morphological and biochemical properties of metatarsophalangeal joint cartilage. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 1997;87:447–59. 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Del Carlo M Jr, Loeser RF. Nitric oxide-mediated chondrocyte cell death requires the generation of additional reactive oxygen species. Arthritis Rheum 2002;46:394–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cox AG, Winterbourn CC, Hampton MB. Measuring the redox state of cellular peroxiredoxins by immunoblotting. Methods Enzymol 2010;474:51–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lotz M, Loeser RF. Effects of aging on articular cartilage homeostasis. Bone 2012;51:241–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Klomsiri C, Karplus PA, Poole LB. Cysteine-based redox switches in enzymes. Antioxidants Redox Signal 2011;14: 1065–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wood ZA, Poole LB, Karplus PA. Peroxiredoxin evolution and the regulation of hydrogen peroxide signaling. Science 2003;300:650–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Toxopeus C, van Holsteijn I, Thuring JW, Blaauboer BJ, Noordhoek J. Cytotoxicity of menadione and related quinones in freshly isolated rat hepatocytes: effects on thiol homeostasis and energy charge. Arch Toxicol 1993;67:674–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seanor KL, Cross JV, Nguyen SM, Yan M, Templeton DJ. Reactive quinones differentially regulate SAPK/JNK and p38/mHOG stress kinases. Antioxidants Redox Signal 2003;5:103–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Loeser RF, Carlson CS, Del Carlo M, Cole A. Detection of nitrotyrosine in aging and osteoarthritic cartilage: correlation of oxidative damage with the presence of interleukin-1beta and with chondrocyte resistance to insulin-like growth factor 1. Arthritis Rheum 2002;46:2349–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.