Abstract

Over the past two decades, there has been growing interest in improving black men’s health and the health disparities affecting them. Yet, the health of black men consistently ranks lowest across nearly all groups in the United States. Evidence on the health and social causes of morbidity and mortality among black men has been narrowly concentrated on public health problems (e.g., violence, prostate cancer, and HIV/AIDS) and determinants of health (e.g., education and male gender socialization). This limited focus omits age-specific leading causes of death and other social determinants of health, such as discrimination, segregation, access to health care, employment, and income. This review discusses the leading causes of death for black men and the associated risk factors, as well as identifies gaps in the literature and presents a racialized and gendered framework to guide efforts to address the persistent inequities in health affecting black men.

Keywords: men’s health, African American, intersectionality, social determinants of health, men’s health disparities, health equity

INTRODUCTION

In 1952, Ralph Ellison published Invisible Man, a novel describing the nameless protagonist’s self-reflexive journey from the American South to the North and his experiences of racial discrimination as a black man during the Great Migration of southern blacks to northern cities (18). As a result of his social experiences, the protagonist realizes that he is socially and politically invisible because the people he encounters and the policies that govern him see him only as a stereotype or caricature. Based on the intersection of his race and gender, society engages with the protagonist according to his social identity as a representation of a group rather than his personal attributes and identity as an individual. Thus, as Ellison so appropriately elucidates, the protagonist is not given a name and is unknown because it is irrelevant to the larger society, which ubiquitously categorizes him as black and male. With this categorization comes a set of stereotypes about criminality, ineptitude, and poor health behaviors, which ironically shift the blame for poor health outcomes to the individual who, like the protagonist, is rarely seen as one. Ellison’s invisible man becomes a metaphor for the historical and current social realities for many black boys and men. This metaphor illuminates the limitations in research on black men’s health, which is part of the focus on this manuscript.

In recent decades, studies of black men’s health have focused somewhat narrowly on four perspectives: (a) maladaptive behaviors that are presumed to reflect deeper cultural and psychological deficits, (b) the victimization and systematic oppression of black males, (c) strategies to promote adaptive coping to racism and other structural barriers, and (d) health-promotion strategies rooted in African and African American cultural traditions (3, 37, 47). We assert that in order to fully understand and improve the health of black men it is imperative to take a more complete view of black men’s health outcomes and obtain a broader understanding of how social experiences and institutional forces influence these outcomes. The legacy of slavery is a root cause of these institutional forces. However, more recent forms of discrimination such as Jim Crow, lynching, de facto segregation, and the prison industrial complex, enacted against black Americans in contemporary US society are enduring versions of institutional forces that manufacture and maintain health disparities. Throughout American history, African Americans have suffered different and worse health status and outcomes, which began as a slave health deficit (5). The treatment of black men and black women was very harsh during slavery; however, where it may have differed is in the demonization and criminalization of black men in ways that require a more nuanced understanding of these determinants of black men’s health (23, 24, 27). This differential treatment may have led to the early reports from the US Census between 1731 and 1812, showing that black males lived shorter lives than did white males and black females (16, 43, 45, 60). This article provides a road map to help public health researchers and practitioners develop strategies to improve the health of black men. By applying four frameworks that help to contextualize the proximal and distal determinants of black men’s health across the life course, the goal is to move beyond restating the poor health profile of black men and instead progress toward a discourse that provides guidance for programmatic and policy interventions.

BLACK MEN’S HEALTH: LEADING CAUSES OF MORBIDITY AND MORTALITY

The health of black men continues to be worse than that of nearly all other groups in the United States. On average, black men die more than 7 years earlier than do US women of all races, and black men die younger than all other groups of men, except Native Americans (25, 76). In 1900, white men could expect to live, on average, for 46.6 years, but black men could expect to live only 32.5 years, more than 14 years less. A similar, but slightly less pronounced, gap was also apparent between white and black women. By 1960, well after the end of slavery, but still amid Jim Crow laws (state and local laws enforcing de-jure racial segregation) throughout the country, disparities had narrowed but were still considerable, with white men living to 67.6 years and black men to 60.7 years. Among women, the racial disparity had narrowed far less during this time. Since the end of official, de jure, or legal, segregation, the disparity between black men and white men’s life expectancy has increased and then declined once more. A similar but less pronounced pattern can be observed between black and white women.

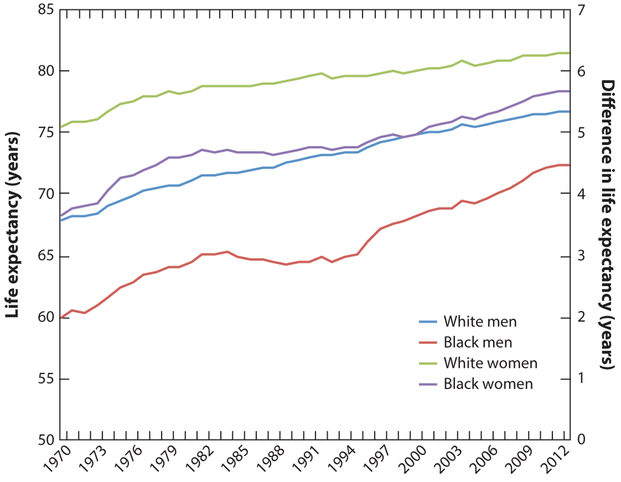

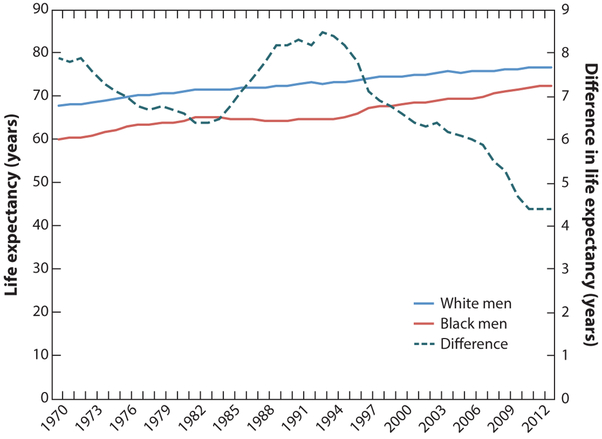

Figures 1–3 show disparities in life expectancy, by race and gender, since 1970. From 1970 to the early 1980s, the absolute difference in life expectancy between black and white men went from less than 8 years (in 1970) to more than 6 years (1983) (Figure 3). However, in 1984, the racial disparities in life expectancy began to rise again, peaking at a difference of 8.5 years in 1993. Since that time, disparities have steadily declined, but still remain unacceptably large. At last measure (in 2013), white men’s life expectancy was 76.7 years while black men’s was 72.3 years, for a difference of 4.4 years. After a disturbing rise in disparities during the 1980s and 1990s, trends are again moving in a positive direction, but there is still a significant gap to close.

Figure 1.

Life expectancy by race and gender, 1970–2013. Data taken from Centers for Disease Control, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System, Life expectancy at birth for selected years (8, 9).

Figure 3.

Differences in life expectancy between black and white men, 1970–2012. Data taken from Centers for Disease Control, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System, Life expectancy at birth for selected years (8, 9).

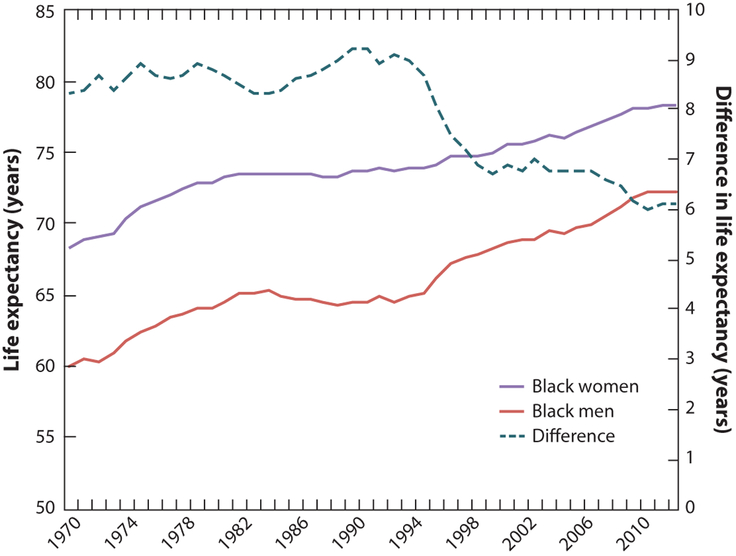

In the United States, black men, white men, black women, and white women share many of the same leading causes of death, but there are some notable differences by race, gender and age (Table 1). The gender gap in life expectancy between black men and women (6.1 years) is wider than the racial gap among men (4.4 years) or among women (3.0 years). The gender gap in life expectancy between black men and women is also larger than the gender gap between white men and women (4.7 years). In 2013, the top three causes of mortality among men overall were heart disease, cancer, and unintentional injuries (7); however, the only race by gender group for which homicide is a top-five cause of death is for black males between the ages of 15 and 44 (Table 1). In addition to homicide, diseases of the lower respiratory tract, HIV disease, and septicemia are among the top-10 causes of death for black men between the ages of 25 and 59 years. Among US men overall, suicide, Alzheimer’s disease, influenza, and pneumonia figure in the top-10 causes of death, but they do not for black men. Also, AIDS is seven times more prevalent in black men than in white men, and black men are more than nine times more likely to die from AIDS and HIV-related illness.

Table 1.

Top 10 causes of death for black men compared with black women, white men, and white women, 2013. Data taken from Reference 57

| Cause of death | Black men | Black women | White men | White women |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart disease | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Malignant neoplasms | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Unintentional injury | 3 | 7 | 3 | 6 |

| Cerebrovascular diseases | 4 | 3 | 5 | 4 |

| Homicide | 5 | NA | NA | NA |

| Diabetes mellitus | 6 | 4 | 6 | 7 |

| Chronic lower respiratory disease | 7 | 5 | 4 | 3 |

| Nephritis, nephrotic syndrome, and nephrosis | 8 | 6 | - | 9 |

| Septicemia | 9 | 9 | - | 10 |

| Influenza and pneumonia | 10 | - | 9 | 8 |

NA, not applicable.

Even for within-race comparisons, the health factors affecting black men and black women differ. Black men succumb to many of the same leading causes of mortality as black women, with two important exceptions: Hypertension and Alzheimer’s as causes of death in black women replace homicide and HIV in black men (6).

Black men are more likely than other segments of the population to have undiagnosed or poorly managed chronic conditions (e.g., diabetes, cancers, heart disease) and to delay seeking medical care (34, 48, 76, 79). Notably, these gaps are not explained solely by the relatively lower socioeconomic status of black men compared with white men or by differences in patterns of health behaviors (30, 38, 76). As overall mortality and morbidity have improved in the United States, black men remain more likely to die from chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and cancers, compared with their white counterparts, and it is not readily understood why (30, 79).

Although the mortality gap between black and white women began closing during the past four decades, the gap between black and white men has widened (71). One study argues that part of this change may be a function of the combined effect of state-specific changes and the racial distribution across states (42). A 2013 study showed that black men between the ages of 25 and 64 years have higher total mortality rates than all other racial and ethnic groups (51). However, the 2013 study by Levine and colleagues also showed that between 1999 and 2007, in 66 US counties, black men in this same age group had lower mortality than their white counterparts, which the authors attributed to black men having higher incomes and less poverty, including a higher percentage of elderly veterans than white men (51). Whereas the study by Levine and colleagues illustrates that there is some geographic diversity in racial disparities among men, the mortality gap between black and white men may be explained, in part, by the fact that black men’s incomes have not increased at the same rate as have the incomes of black or white women. In fact, the median income for black and white men in their thirties has declined since the 1970s (79), and black men’s unemployment rates remain higher than those of other groups of men (30). Although population-level health disparities are typically displayed by race or gender, data presented by race and gender, which would allow us to examine the unique health profile of black men, are rarely available (see Figure 1 for life expectancies by race and gender) (47, 79).

Data presented by race and gender highlight black men’s unique health patterns and the need to systematically explore variations among men and among blacks. The data and research findings about black men’s health do not adequately explain the sources of morbidity and mortality that are similar to those that affect other men or black women, but that may be found to operate differently when intersections of race and gender are considered (37). Historically, health research and public health data about men have focused on white men and have rarely considered the unique patterns of health that vary at the intersection of race and gender. There is a critical need to better explain black men’s trends of mortality and health as we move into the twenty-first century and to increase the visibility of black men’s health by adopting a combined race–gender focus within public health.

WHY ARE BLACK MEN INVISIBLE AND MISSING? THE EMERGING NEED FOR A RACE AND GENDER HEALTH AGENDA

Returning to the theme of invisibility, Ralph Ellison’s notion of figurative invisibility can be expanded to include the actual physical invisibility of black men in the black community and in key forms of civic engagement. According to an analysis by Wolfers and colleagues (82), data from the US Census demonstrate that there are more than 1.5 million black men between the ages of 25 and 54 years who are missing from daily life as a result of premature mortality (900,000 black men) or incarceration (625,000 black men) (83). Black men who are released from prison are also invisible as a result of not being represented in national survey samples, which, therefore, grossly mischaracterize black men’s social, economic, and health statuses. This undercounting of black men adversely affects the perceived and actual need for economic resources and social services, and the political needs of the communities to which these men return upon release. Many formerly incarcerated men are unable to obtain legitimate employment and do not participate in civic life, which not only affects them but also affects the communities where they and their families live (64). Black men disappear from daily life into concrete cells and are released into cities across the United States that relegate them beyond the social and economic margins into a chasm of social isolation, which reinforces their physical and figurative invisibility, much like Ellison’s protagonist. Paradoxically, where black men are hypervisible is in the criminal justice system, and they increasingly have fatal encounters with police officers (29) while remaining invisible in research and policies aimed at improving their health.

Attention to the health of black men tends to fall between research on racial and ethnic health disparities and men’s health. In research on health disparities, there is a need to look beyond race and ethnicity to consider gender and other factors that shape psychological and social experiences. In addition, in research on men’s health, issues of racial or ethnic diversity are typically rendered invisible (31, 37). Although there are multiple masculinities that shape men’s beliefs about, and experiences regarding, masculinity and manhood, most explorations of masculinity among black men explore how they exhibit traditional notions of masculinity and respond to scales that represent hegemonic notions of masculinity (35, 36).

The problem of focusing on race and ethnicity or gender also extends from descriptive studies to intervention studies (37). For example, interventions to increase healthy eating, physical activity, or weight loss among black Americans rarely recruit equal sample sizes of black men and women (59). Although these interventions appear to be somewhat effective for black men, it is likely that paying greater attention to surface-level and deep structural factors associated with being a certain gender, in addition to race and ethnicity, could enroll a larger proportion of men and yield more effective interventions for black men (17, 34).

Increasingly, there is a recognition that more attention needs to be paid to the fact that being a black man is more than the additive effects of being black and being male (31). Integrating race and gender using an intersectional approach could add a depth of understanding to how public health conceptualizes black men’s health. Intersectionality is an approach to research that highlights the need to reconceptualize the social determinants of health for populations at the nexus of key, socially-relevant identities (e.g., race, ethnicity, gender, age). This need is particularly acute for the examination of black men. An intersectional racialized and gendered approach to understanding the social, economic, and health trajectories of black men offers a framework for understanding the systemic and structural barriers that limit them from optimizing their chances to live long, healthy lives (31, 32, 37).

MASCULINITY AND BLACK MEN’S HEALTH:DRAWING CONNECTIONS BETWEEN RACE,GENDER, SOCIOECONOMIC STATUS, AND HEALTH

One of the unique aspects of studying black men’s health is that black men are simultaneously advantaged by gender yet marginalized by race (63, 81). Structural forces in the United States that vary by race have limited how black men can define themselves in relation to cultural ideals and gender role identities (e.g., fulfilling the role of economic provider) (58, 74). Although men’s gender identity is often thought of as an innate quality that is the natural result of being a biological male, gendered ideals are constructed through intrapersonal and interpersonal relationships (50). What it means to be a black man is influenced by historical, social, cultural, and economic factors.

Gender identity is signified by beliefs and behaviors that are practiced in social interactions and, therefore, varies among cultures and individuals (2). The dominant form of masculinity in Western societies is one imbued with hegemony that privileges traditional gender norms and family forms (66, 68). Black men in their middle-adult years often evaluate their sense of manhood against their ability to fulfill their roles as provider, husband, father, employee, and community member (37, 41, 58). Many black men cannot achieve success in these roles as a result of a cycle of poverty that emerges from a history of black men being paid less than 75% of what white men are paid. The cycle of poverty is shown when we compare the 9.5% unemployment rate of black men with the 4% unemployment rate of white men. The structural barriers to black men fulfilling the provider role may lead to more stress-related health issues because black men who define themselves through fulfilling traditional roles may see themselves as being less of a man owing to their inability to provide financially for their families. Historically, black men have been far less likely than white men to be the sole providers for their households, yet there are still cultural and social pressures that tend to view men through this narrow lens (32, 37). In the next section, we review how masculinity influences behaviors and access to, and utilization of, health care services.

Factors that affect men’s health care–seeking behaviors and men’s access to, and use of, health care services must be understood in terms of men’s adherence to masculine ideals. Men are 24% less likely than women to have visited a doctor within the past year but are 32% more likely to be hospitalized (40, 73, 79, 84). Black men are far less likely to access health care than are white men or any group of women. Black men are 75% less likely to have health insurance than white men. Thirty percent of all men, compared with 19% of all women, do not have a regular physician (40). Nonetheless, access to or a lack of access to health insurance alone does not explain health care utilization rates.

Black men in all income groups are 50% less likely to have had contact with physicians during the past year, even when they have health insurance (40). The avoidance of health care providers by men has been offered as a partial explanation for their increased mortality rates from heart disease and other chronic diseases (40, 73, 79, 84). A man’s socioeconomic position further complicates this story. Men in lower social and economic positions may also conform more to traditional male role norms, which allows them to diminish their vulnerabilities (39, 40). When compared with white men, black men do not benefit equally from higher educational attainment in terms of their access to health-promoting neighborhood resources, ability to maintain employment, access to social networks of people who can facilitate access to jobs, or their access to wealth to buffer against emergencies and unexpected needs (69, 79). Black men and men who are socially or economically disadvantaged may also distrust health care systems and providers, and they are more likely than white men to experience discrimination in health care settings (1, 13, 26, 39).

PROFILING HEALTH BEHAVIORS IN BLACK MEN’S HEALTH

In addition to the economic and social factors that affect the relationship between manhood and health, black men’s views of themselves and their definitions of manhood appear to be broader than the conceptions of manhood reported for white men (32, 33, 41, 46, 77). Although research on white men’s definitions of masculinity and manhood tend to focus on virility, risk taking, physical strength, hardiness, and economic and social power (14, 74), studies of black men indicate that their definitions of manhood also tend to include spirituality, connection to the community, interdependence within their family, and the achievement of social status through their roles in community-based organizations and institutions (32, 33, 41, 74). It is unclear if this difference is due to racial or ethnic differences between men of the same age or the fact that the vast majority of research on white men and masculinity has focused on college age or young adult white men.

Across the life course, the stressors associated with beliefs and expectations about men’s economic opportunities and social marginalization can directly and indirectly contribute to men having poor health behaviors and high rates of premature mortality (79). Striving for masculinity may lead to stress and ways of coping that result from trying to achieve economic success and social status and also to risky behaviors that may represent traditional aspects of masculinity (e.g., eating large portions, alcohol abuse, substance use, risky types of physical activity, inconsistency in safe-sex practices) (4, 32).

Behaviors that directly affect health are modifiable and can have a positive or negative impact on the health profile of men (30,75); however, these health behaviors can depend on determinants of disparities in men’s health, such as childhood socioeconomic status, parental wealth accumulation, access to health care in childhood, or the quality of childhood health care (30, 56, 76, 84). Specifically, despite men having agency to engage in healthy behavior, all men do not have equal opportunities to make healthy choices (52). Health behaviors are used in daily interactions to help men negotiate social power and social status, but these same health practices can either undermine or promote health (14). However, men, regardless of race, often prefer to risk their physical health and well-being rather than be associated with traits they or others may perceive as feminine (19). Men’s adherence to traditionally masculine ideals is theorized to contribute to the disparity between men’s and women’s health outcomes (14, 84). The challenges of demonstrating masculine ideals through educational attainment and economic means may lead to disparities in health behaviors and outcomes between black men and women and between black men and other groups of men. In other words, several factors that intersect with masculine identities and expressions impact the health profiles of black men.

FRAMING BLACK MEN’S HEALTH: SOCIAL AND BEHAVIORAL DETERMINANTS

Consistent with the overall public health evidence, the bulk of research on determinants of health for black men has focused on either the determinants of racial differences in health status or on the determinants of gender differences in health status, with greater emphasis on the former. Perhaps the most notable insights have come from the robust set of studies that point to two primary and related mechanisms that account for racial disparities in health: racial disparities in socioeconomic resources and the added burden for black men and women of experiences of racial discrimination (72, 79, 80). However, far less is known about (a) whether the burden on health of each of these pathways is greater (or lesser) in black men versus black women and (b) whether the pathways and their resultant effects on health status are experienced differently between these two groups (31, 65). Indeed, evidence from the fields of sociology and economics suggests that in the context of the labor market, some black men may experience greater discrimination and, therefore, greater socioeconomic disadvantage than black women (61).

Thus, to improve the health of black men, it is critical to understand the ways that social and economic determinants influence black men’s health and health behaviors. This will help to shift the focus of public health interventions (and related resources) toward changing the social and economic determinants that have the greatest likelihood of improving the health outcomes of black men (79). Next, we address these conceptual gaps by highlighting four complementary frameworks or theories (i.e., life-course theories, the environmental affordances model, the intersectionality framework, and critical race theory) that help to enhance our understanding of the social and economic contexts of black men’s health.

FRAMEWORKS FOR STUDYING BLACK MEN’S HEALTH

Life-Course Theory and Model

A focus on black men’s health can benefit from incorporating life-course theory (32, 44, 75). Life-course theory suggests that an individual’s health status in adulthood results from exposures that act in three primary ways: (a) through a latency mechanism in which early life exposures (particularly those that occur during critical or developmentally sensitive periods of early childhood) influence adult health irrespective of the intervening set of exposures, be they damaging or corrective; (b) through a cumulative mechanism, which suggests that it is the combination of exposures over time that lead to ill health; and (c) through a pathway mechanism in which subsequent exposures are dependent on previous exposures, which then create an exposure trajectory that determines health status.

A range of studies that draws on life-course theory has demonstrated both independent and combined influences of early (childhood) and late (adult) socioeconomic status on a variety of health outcomes (11, 28, 54). Given the potential importance of socioeconomic disadvantage in explaining health disadvantages among black men and women, it is somewhat surprising that more studies have not drawn on life-course theory to explain racial disparities in health (28, 75). In fact, a PubMed search for the terms “black,” “life course,” and “socioeconomic” produced only 26 studies. Of these, only a handful were relevant to this review of black men’s health, but those that were relevant showed consistent evidence of all pathways through which social and economic factors affect health over the life course. We also conducted a search for studies that applied a life-course theory approach to the other major mechanism for racial health disparities cited in the literature, experiences of discrimination (using the search terms “black,” “life course,” and “discrimination”). This yielded only 10 studies, of which none seemed to address life-course experiences of discrimination.

Thorpe & Kelley-Moore (75) have suggested that studies of health disparities that include a life-course approach use more biological, psychosocial, and environmental measures across the life course and that these also capture an ecological perspective. For example, different time points and duration of exposure have been used in some studies of the influence of the environment on racial differences in predisposition to hypertension and stroke across the life course for blacks and whites. According to Gilbert and colleagues (28), black men have a higher risk for developing hypertension when exposed to segregated environments earlier in life. These environmental factors are often unaccounted for in the study of black men’s health, and they are needed to explore and explain the complexity of black men’s health profiles, as well as to determine how these profiles are structured not only by social and physical environments but also by policies that negatively shape health outcomes and health behaviors (e.g., in terms of access to and use of health care services), especially when it comes to cardiovascular disease (28, 38).

Environmental Affordances Model

The environmental affordances model provides a framework for explaining how racial differences in the contexts where people are exposed to stress may contribute to differences in coping behaviors and mental and physical health outcomes. Jackson & Knight (48) argue that stressful social and economic living conditions combined with restricted access to a range of potential resources to manage those conditions, may contribute to behavioral responses to stress that may adversely affect health outcomes. This testable, theory-driven model is also designed to explain the fact that black Americans tend to have lower rates of mood and anxiety disorders and other psychiatric diagnoses than white Americans, but black Americans tend to have higher rates of chronic physical health diseases than white Americans (48). Jackson & Knight explain this counterintuitive finding by describing how coping strategies for dealing with stress are shaped by the gender-appropriate coping strategies that the built environment affords people the opportunity to use. For black men, the coping resources available in their neighborhoods are often tobacco, alcohol, physical inactivity, and substance abuse. Despite the negative physical health effects associated with these coping mechanisms, these behaviors may have protective effects on mental health, such as by reducing anxiety and stress.

Intersectionality Framework

The intersectionality framework can be a useful theoretical and methodological tool for broadening the breadth of research on intersectional identities (15, 78). Although intersectionality was originally developed as a framework to explain the experiences of black women, it is also applicable to black men (34, 37). Similar to black women, black men’s identities straddle the intersection of race and gender. Although black women are sexualized, black men are criminalized (29), particularly younger black men (65). Research has shown that black men may experience more intense discrimination than black women and men of other racial and ethnic groups because they tend to be assessed, and interacted with, on the basis of a range of negative race- and gender-based stereotypes (28, 65, 79).

The purpose of the intersectionality framework is to provide a lens that “focuses on the complexity of relationships among multiple social groups within and across analytical categories” (55, p. 1786). Rather than simply controlling for race or gender in a statistical model, using an intersectional approach helps to explain the unique psychological factors that underlie the experiences that exist at the nexus of race and gender identities. Moreover, intersectionality theory provides the opportunity to examine how US and race-specific standards of masculinity influence the health and health behaviors of black men. The gendered, racialized, and economic factors that shape black men’s health outcomes cannot be understood independently; they are inextricably intertwined and experienced simultaneously with the social determinants of health. Only through an intersectional lens can they be adequately understood (31).

This approach to intersectionality is what McCall (55) calls the “intercategorical complexity” (or categorical) approach (p. 1773). Choo & Ferree (12) call this approach the “process-centered model of intersectionality” (p. 134). This approach not only compares the outcomes of different race-gender groups as mentioned above, but also examines the effects of specific covariates for each group. This approach “begins with the observation that there are relationships of inequality among already constituted social groups, as imperfect and ever changing as they are, and takes those relationships as the center of analysis.… The subject is multigroup, and the method is systematically comparative” (55, pp. 1784–86). Choo & Ferree (12, p. 134) argue that the categorical or process-centered approach to intersectionality “runs the risk of focusing on abstract structures” by downplaying the agency of individuals who are simultaneously “experiencing the impact of micro- and meso-interactions.” They state that researchers can overcome this limitation by focusing on “cultural meanings and the social construction of categories” (12, p. 134). The intersectionality framework suggests that race- and gender-based experiences affect health differently across groups. To understand the health of groups defined by race and gender, it is critical to consider how these socially relevant factors combine in unique ways to shape the social experiences that influence health outcomes.

Critical Race Theory

When we consider race as a primary determinant of health outcomes for black men, we can consider the work of critical race theory as it has been applied in public health (20, 21). Marable (53) has suggested that “black America still sees itself as the litmus test of the viability and reality of American democracy” because “African American striving for freedom and human rights embodies the country’s best examples of sacrifice for the realization of democracy’s highest ideals” (p. 24). Because of the social and economic constraints on black men pursuing hegemonic masculine ideals, black men have the poorest status across a number of health outcomes and black men are systematically disengaged from institutions that provide aid and support, such as employment, education, and health care. The inability to realize democratic ideals becomes embodied in the lived experiences of black men in the United States as they continue to be underrepresented in, or underserved by, these institutions and, thus, are unable to access the same benefits of living in the United States as are other groups defined by race and gender.

The methodology of public health critical race theory provides a framework that can be used to improve research and interventions to address the inequities described for black men (20–22). Public health critical race theory is an approach that builds on critical race theory and public health theories and methods to articulate how best to understand and address social and health issues to achieve social justice for marginalized groups. Specifically, this theory addresses racialization and its influence on historical and current patterns of racial relation. Public health critical race theory also considers the social construction of knowledge and strategies to achieve three goals: (a) to provide pathways to better lift the voices of marginalized populations, (b) to identify appropriate measures to capture social constructions of race, and (c) to develop action steps to address the inequality being discussed from a community-engaged perspective.

For black men, the challenge of making a healthful change in their lifestyle or behavior is shaped by long-standing social and historical conditions of inequality. These conditions comprise a system of institutional racism or a process of assigning value, privilege, and opportunity on the basis of physical characteristics (49). Critical race theory acknowledges the inability to redress the roots of prejudice based on skin color, and for our purposes, skin color and perceived gender become identities that are more difficult to remediate within the American legal system as compared with other identities. All forms of racism and gender discrimination undermine progress; however, the inability to address the intersections of race and gender erode the traditional sensibilities of manhood for many black men.

Applying and Integrating These Theories: A Case Example

Improving black men’s health depends on a clearer conceptualization of how to utilize theoretical models such as those we have discussed. Using the example from Ray’s work below, we illustrate strategies to apply life-course theories, the environmental affordances model, the intersectionality framework, and critical race theory.

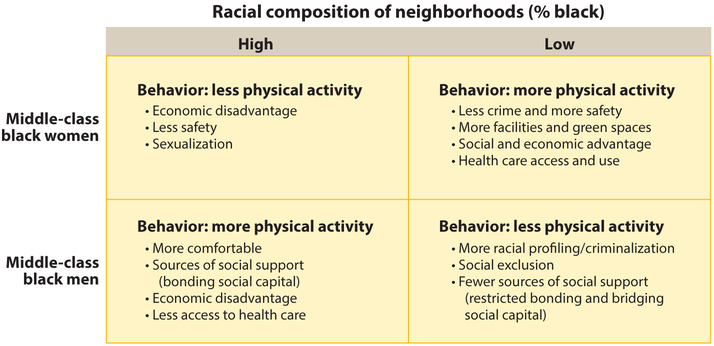

Using a sample of middle-class blacks and whites (N=482) living in urban and suburban areas, Ray (67) focused on how perceptions of the racial composition of neighborhoods influenced leisure-time physical activity. Ray used two separate measures (one that measured the perceived percentage of blacks in a neighborhood and another that measured the perceived percentage of whites in a neighborhood) and showed that black men were less likely to be physically active as the perceived percentage of whites in a neighborhood increased. Alternatively, they were more likely to be physically active in neighborhoods perceived as predominately black. Conversely, black women were more likely to be physically active in neighborhoods perceived to be predominately white and less likely to be physically active in neighborhoods perceived as predominately black (10, 62). Ray used the intersectionality framework to illuminate how black men’s physical activity may be shaped by concerns of being racially profiled, whereas black women’s physical activity may be shaped by concerns about safety. Based on the social structures that place middle-class and poor black neighborhoods close to each other, communities with a higher perceived percentage of blacks are also perceived as less safe (10, 62). Additionally, neighborhoods perceived as predominately white are perceived as having more facilities and programs that may cater to women. For example, fitness centers in more affluent neighborhoods are creating women-only zones where women can avoid male-dominated spaces.

Each framework we have described provides a unique contribution to how researchers and practitioners may better address several important gaps within the literature on men’s health and health disparities. The example in Figure 4 illustrates intersectionality. Life-course theory would prompt for an additional examination of how effects on black men’s physical activity might affect their health outcomes if experienced consistently over time. Environmental affordances theory would prompt for additional consideration of the physical environments black men experience, such as their neighborhoods and how those spaces shape their access to making healthful decisions, as well as exposing them to various chemical toxins and limiting their access to educational and economic resources. Finally, critical race theory would potentially add a layer of insights in relation to the salience of race and the racialization processes that occur at interpersonal and institutional levels. When we add gender to the examination of the experiences of black men, we understand more about the differences between black men and black women and their divergent health trajectories.

Figure 4.

A typology of neighborhood racial composition and health behaviors, by race and gender.

Using the example of Ray’s work, we focus on the health behaviors of black men within two contexts: high racial composition versus low racial composition (as measured by the percentage of black residents in a neighborhood) (Figure 4). Physical activity differs for black men and black women by the social, economic, and other demographic factors associated with where they live. We can extend this argument to consider other contexts, such as the workplace, health care settings, and schools (28). For the purpose of this example, we focus on the role of the neighborhood. How black men experience their social world (much like Ellison’s protagonist discussed earlier) has an impact on their perceived sense of safety, sense of community, the depth and scope of their social capital or social ties, and their access to and use of health-promoting resources.

What this example suggests, first, is that there may be an overall lack of health resources available to black men and there are barriers to how black men access these resources. Second, we cannot expect social and health policies that may promote economic development, education, and access to health care for all to help overcome the unique challenges that black men face. Third, when we refer to the example above, there are specific approaches and applications that can be used with each theoretical model to consider how to enhance the health of black men over their life course by attending to a focus on race and gender (that is, how these race and gender identities are advantaged and disadvantaged), thus countering racial discrimination and enhancing the social and physical contexts in which black men live, go to school, work, and spend their leisure time.

THE FUTURE OF BLACK MEN’S HEALTH:CONCLUSION AND IMPLICATIONS

The road ahead for improving black men’s health is to counter the social, economic, and health outcomes that relegate black men to invisibility from an early age. The challenge to public health, as well as other disciplines, is to take advantage of the tools, methods, and approaches that help us better understand the ways that social determinants of health have combined in unique ways to consistently lead to poorer health outcomes for black men than other groups at the intersections of race and gender. With these tools, we can better identify solutions to ensure that black men reap the benefits of public health, economic, social, and political interventions. To improve health outcomes for black men in the United States, conceptualizing the issues using the life-course theories, the environmental affordances model, intersectionality framework, and critical race theory will help to create better programs and policies to reduce racial and gender disparities in health.

The work presented illustrates the complexity of black men’s health. Safford et al. (70) proposed that overall health is a function of “the interactions between biological, cultural, environmental, socioeconomic, and behavioral forces” (p. 382). Consequently, interventions to improve black men’s health need to be equally multifaceted because there is no one strategy that will fix black men’s health. What will improve black men’s health and reduce racial and gender disparities in health is a more sophisticated conceptualization of the problem and a coordinated set of policies and programs that link the diverse sectors of society to collaborate across education, criminal justice, medicine, labor, urban planning, and public health to recognize that the poor health outcomes of black men are the result of policies enacted by all these entities over time. Creating solutions to improve the poor health of black men may come only when we collectively recognize how to undo and ameliorate policies and practices that have unwittingly produced the health profile of black men we see today.

Figure 2.

Differences in life expectancy between black men and black women, 1970–2012. Data taken from Centers for Disease Control, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System, Life expectancy at birth for selected years (8, 9).

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The authors are not aware of any affiliations, memberships, funding, or financial holdings that might be perceived as affecting the objectivity of this review.

LITERATURE CITED

- 1.Ashton CM, Haidet P, Paterniti DA, Collins TC, Gordon HS, et al. 2003. Racial and ethnic disparities in the use of health services: bias, preferences, or poor communication? J. Gen. Intern. Med 18:146–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Battle J, Scott BM. 2000. Mother-only versus father-only households: educational outcomes for African American males. J. Afr. Am. Men 5:93–116 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bowman PJ. 1989. Research perspectives on black men: role strain and adaptation across the adult life cycle In Black Adult Development and Aging, ed. Jones RL, pp. 117–50. Berkeley, CA: Cobb & Henry [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruce MA, Griffith DM, Thorpe RJ Jr. 2015. Stress and the kidney. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis 22:46–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Byrd WM, Clayton LA. 2000. An American Health Dilemma: A Medical History of African Americans and the Problem of Race, Beginnings to 1900. Vol. 1 New York: Routledge; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.CDC (Cent. Dis. Control Prev.). 2011. Leading causes of death. [Google Scholar]

- 7.CDC (Cent. Dis. Control Prev.). 2014. Leading causes of death. Last updated Feb. 18, 2015, CDC, Atlanta: http://www.cdc.gov/men/lcod/2011/LCODrace_ethnicityMen2011.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 8.CDC (Cent. Dis. Control Prev.). 2015. National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). Updated Dec. 11,CDC, Atlanta: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ [Google Scholar]

- 9.CDC (Cent. Dis. Control Prev.). 2015. National Vital Statistics System (NVSS). Updated Dec. 11, CDC, Atlanta: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss.htm [Google Scholar]

- 10.Charles CZ. 2003. The dynamics of racial residential segregation. Annu. Rev. Sociol 29:167–207 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chichlowska KL, Rose KM, Diez-Roux AV, Golden SH, McNeill AM, Heiss G. 2009. Life course socioeconomic conditions and metabolic syndrome in adults: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Ann. Epidemiol 19:875–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choo HY, Ferree MM. 2015. Practicing intersectionality in sociological research: a critical analysis of inclusions, interactions, and institutions in the study of inequalities. Sociol. Theory 28:129–49 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB, Williams MV, Moody-Ayers S. 1999. Attitudes and beliefs of African Americans toward participation in medical research. J. Gen. Intern. Med 14:537–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Courtenay WH. 2000. Constructions of masculinity and their influence on men’s well-being: a theory of gender and health. Soc. Sci. Med 50:1385–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crenshaw K. 1991. Mapping the margins: intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanf. Law Rev. 43:1241–99 [Google Scholar]

- 16.David PA, Gutman HG, Sutch R, Temin P, Wright G. 1976. A Reckoning with Slavery: A Critical Study in the Quantitative History of American Negro Slavery. New York: Oxford Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ellis KR, Griffith DM, Allen JO, Thorpe RJ, Bruce MA. 2015. “If you do nothing about stress, the next thing you know, you’re shattered”: perspectives on African American men’s stress, coping and health from African American men and key women in their lives. Soc. Sci. Med 139:107–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ellison R. 1952. Invisible Man. New York: Random House [Google Scholar]

- 19.Evans J, Frank B, Oliffe JL, Gregory D. 2011. Health, illness, men and masculinities (HIMM): a theoretical framework for understanding men and their health. J. Men’s Health 8:7–15 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ford CL, Airhihenbuwa CO. 2010. The public health critical race methodology: praxis for antiracism research. Soc. Sci. Med 71:1390–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ford CL, Airhihenbuwa CO. 2010. Critical race theory, race equity, and public health: toward antiracism praxis. Am. J. Public Health 100:693–98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ford CL, Airhihenbuwa CO. 2010. The public health critical race methodology: praxis for antiracism research. Soc. Sci. Med 71:1390–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frazier EF. 1939. Negro Family in the United States. Notre Dame, IN: Univ. Notre Dame Press [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frazier EF. 1957. The Negro in the United States. New York: Macmillan [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gadson SL. 2006. The third world health status of black American males. J. Natl. Med. Assoc 98:488–91 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gary TL, Stark SA, LaVeist TA. 2007. Neighborhood characteristics and mental health among African Americans and whites living in a racially integrated urban community. Health Place 13:569–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Giddings PJ. 1984. When and Where I Enter: The Impact of Black Women on Race and Sex in America. New York: Harper Collins [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gilbert KL, Elder K, Lyons S, Kaphingst KA, Blanchard M, Goodman MS. 2015. Racial composition over the lifecourse: examining separate and unequal environments and the risk for heart disease for African American men. Ethn. Dis 25:295–304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gilbert KL, Ray R. 2015. Why police kill black males with impunity: applying Public Health Critical Race Praxis (PHCRP) to address the determinants of policing behaviors and “justifiable” homicides in the USA. J. Urban Health doi: 10.1007/s11524-015-0005-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gilbert KL, Ray R, Langston M. 2014. Vicious cycle of unequal treatment and social dis(ease) of African American males and health. In Urban Ills: Twenty-First Century Complexities of Urban Living in Global Contexts, Vol. 2, ed. Yeakey CC Thompson VLS, Wells A pp. 23–36. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books; 2nd ed. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Griffith DM. 2012. An intersectional approach to men’s health. J. Men’s Health 9:106–12 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Griffith DM. 2015. I am a man: manhood, minority men’s health and health equity. Ethn. Dis 25:287–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Griffith DM, Brinkley-Rubinstein L, Thorpe RJ, Bruce MA, Metzl JM. 2015. The interdependence of African American men’s definitions of manhood and health. Fam. Community Health 38:284–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Griffith DM, Ellis KR, Allen JO. 2013. An intersectional approach to social determinants of stress for African American men: men’s and women’s perspectives. Am. J. Men’s Health 7(Suppl.):19S–30S [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Griffith DM, Gunter K, Watkins DC. 2012. Measuring masculinity in research on men of color: findings and future directions. Am. J. Public Health 102(Suppl. 2):S187–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Griffith DM, Johnson JL. 2012. Implications of racism for African American men’s cancer risk, morbidity and mortality In Social Determinants of Health Among African American Men, ed. Treadwell HM, Xanthos C, Holden KB, Braithwaite RL, pp. 21–38. New York: Jossey-Bass [Google Scholar]

- 37.Griffith DM, Metzl JM, Gunter K. 2011. Considering intersections of race and gender in interventions that address US men’s health disparities. Public Health 125:417–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Griffith DM, Thorpe RJ Jr. 2016. Men’s physical health and health behaviors In APA Handbook of the Psychology of Men and Masculinities, ed. Wong YJ, Wester SR, pp. 709–30. Washington, DC: APA [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hammond WP. 2010. Psychosocial correlates of medical mistrust among African American men. J. Community Psychol 45:87–106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hammond WP, Chantala K, Hastings JF, Neighbors HW, Snowden L. 2011. Determinants of usual source of care disparities among African American and Caribbean black men: findings from the national survey of American life. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 22:157–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hammond WP, Mattis JS. 2005. Being a man about it: manhood meaning among African American men. Psychol. Men Masc 6:114–26 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Harper S, MacLehose RF, Kaufman JS. 2014. Trends in the black-white life expectancy gap among US states, 1990–2009. Health Aff. 33:1375–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heckler M. 1985. Report of the Secretary’s Task Force on Black and Minority Health. Washington, DC: US Dep. Health Hum. Serv. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hertzman C, Power C. 2003. Health and human development: understandings from life-course research. Dev. Neuropsychol 24:719–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hine DC, Jenkins E, eds. 1999. A Question of Manhood: a Reader in US Black Men’s History and Masculinity, Volume 1. “Manhood Rights”: The Construction of Black Male History and Manhood, 1750-1870. Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hunter AG, Davis JE. 1992. Constructing gender: an exploration of Afro-American men’s conceptualization of manhood. Gend. Soc 6:464–79 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jack L, Griffith DM. 2013. The health of African American men: implications for research and practice. Am. J. Men’s Health 7(Suppl. 4):5S–7S [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jackson JS Knight KM. 2006. Race and self-regulatory health behaviors: the role of the stress response and the HPA axis In Social Structure, Aging and Self-Regulation in the Elderly, ed. Schaie KW, Carstensten LL, pp. 189–240. New York: Springer [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jones CP. 2000. Levels of racism: a theoretic framework and a gardener’s tale. Am. J. Public Health 90:1212–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kimmel MS. 2006. Manhood in America: A Cultural History. New York: Oxford Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- 51.Levine RS, Rust G, Aliyu M, Pisu M, Zoorob R. 2013. United States counties with low black male mortality rates. Am. J. Med 126:76–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lohan M. 2007. How might we understand men’s health better? Integrating explanations from critical studies on men and inequalities in health. Soc. Sci. Med 65:493–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Marable M. 1995. Beyond Black and White: Rethinking Race in American Politics and Society. New York: Verso [Google Scholar]

- 54.Matthews KA, Schwartz JE, Cohen S. 2011. Indices of socioeconomic position across the life course as predictors of coronary calcification in black and white men and women: coronary artery risk development in young adults study. Soc. Sci. Med 73:768–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McCall L. 2005. The complexity of intersectionality. Signs 30:1771–800 [Google Scholar]

- 56.Meryn S, Jadad AR. 2001. The future of men and their health: Are men in danger of extinction? BMJ 323:1014–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Natl. Cent. Health Stat. 2015. Health, United States, 2014: With Special Feature on Adults Aged 55–64. Hyattsville, MD: Natl. Cent. Health Stat. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Neighbors HW, Sellers SL, Zhang R, Jackson JS. 2011. Goal-striving stress and racial differences in mental health. Race Soc. Probl 3:51–62 [Google Scholar]

- 59.Newton RL, Griffith DM, Kearney WB, Bennett GG, Newton RL Jr, et al. 2014. A systematic review of weight loss, physical activity and dietary interventions involving African American men. Obes. Rev 15:93–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nickens H. 1986. Report of the Secretary’s Task Force on Black and Minority Health: a summary and a presentation of health data with regard to blacks. J. Natl. Med. Assoc 78(6):577–80 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pager D. 2003. The mark of a criminal record. Am. J. Sociol 108:937–75 [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pattillo-McCoy M. 1999. Black Picket Fences: Privilege and Peril Among the Black Middle Class. Chicago: Univ. Chicago Press [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pease B. 2009. Racialised masculinities and the health of immigrant and refugee men In Men’s Health: Body, Identity and Context, ed. Broom A, Tovey EP, pp. 182–201. New York: Wiley [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pettit B. 2012. Invisible Men: Mass Incarceration and the Myth of Black Progress. New York: Russell Sage Found. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pieterse AL, Carter RT. 2007. An examination of the relationship between general life stress, racism-related stress, and psychological health among black men. J. Couns. Psychol 54:101–9 [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ray R. 2014. Stalled desegregation and the myth of racial inequality in the U.S. labor market. Du Bois Rev. 11:477–87 [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ray R. 2015. Black people don’t exercise in my neighborhood: relationship between perceived racial composition and leisure-time physical activity among middle class blacks and whites Work. Pap. 2015-013, Md. Popul. Res. Cent., Univ. Md., College Park: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ray R, Rosow JA. 2012. The two different worlds of black and white fraternity men: visibility and accountability as mechanisms of privilege. J. Contemp. Ethnogr 41:66–94 [Google Scholar]

- 69.Royster DA. 2007. What happens to potential discouraged? Masculinity norms and the contrasting institutional and labor market experiences of less affluent black and white men. Ann. Am. Acad. Polit. Soc. Sci 609:153–80 [Google Scholar]

- 70.Safford MM, Allison JJ, Kiefe CI. 2007. Patient complexity: more than comorbidity. The vector model of complexity. J. Gen. Intern. Med 22(Suppl. 3):382–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Satcher D, Higginbotham EJ. 2008. The public health approach to eliminating disparities in health. Am. J. Public Health 98:400–3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Smedley BD. 2012. The lived experience of race and its health consequences. Am. J. Public Health 102:933–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Staples B. 1998. Just walk on by: A black man ponders his power to alter public space. Lit. Cavalc 50:38 [Google Scholar]

- 74.Summers MA. 2004. Manliness and Its Discontents: The Black Middle Class and the Transformation of Masculinity, 1900–1930. Chapel Hill: Univ. N.C. Press [Google Scholar]

- 75.Thorpe RJ, Kelley-Moore JA. 2013. Life course theories of race disparities In Race, Ethnicity, and Health, ed. LaVeist TA, Isaac LA, pp. 355–74. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2nd ed. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Warner DF, Hayward MD. 2006. Early-life origins of the race gap in men’s mortality. J. Health Soc. Behav 47:209–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Whitehead TL. 1997. Urban low-income African American men, HIV/AIDS, and gender identity. Med. Anthropol. Q 11:411–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wilkins AC. 2012. Becoming black women: intimate stories and intersectional identities. Soc. Psychol. Q 75:173–96 [Google Scholar]

- 79.Williams DR. 2003. The health of men: structured inequalities and opportunities. Am. J. Public Health 93:724–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Williams DR, Mohammed SA. 2009. Discrimination and racial disparities in health: evidence and needed research. J. Behav. Med 32:20–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wingfield AH. 2013. No More Invisible Man: Race and Gender in Men’s Work. Philadelphia: Temple Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wolfers J, Leonhardt D, Quealy K. 2015. The methodology: 1.5 million missing black men New York Times, April 20 http://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/21/upshot/the-methodology-1-5-million-missing-black-men.html

- 83.Wolfers J, Leonhardt D, Quealy K. 2015. 1.5 million missing black men New York Times, April 20 http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2015/04/20/upshot/missing-black-men.html

- 84.Xanthos C, Treadwell HM, Holden KB. 2010. Social determinants of health among African-American men. J. Men’s Health 7:11–19 [Google Scholar]