Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The trends in prevalence and incidence of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) dementia remain uncertain.

METHODS

A sample of 2,794 participants with a clinical diagnosis for AD dementia.

RESULTS

The 2010 census standardized prevalence of AD dementia was 14.5% (95% CI= 13.7, 15.3), and annual incidence was 2.3% (1.7, 2.9). Both prevalence and incidence showed substantial variation over time, but no secular trends. The prevalence of AD dementia did not change significantly from 14.6% (95% CI= 13.0, 16.2) in 1994–1997 to 14.7% (95% CI= 13.2, 16.2) in 2010–2012 (p=0.84). The annual incidence of AD dementia was 2.8% (95% CI= 2.2, 3.2) in 1998–2000 and 2.2% (95% CI= 1.6, 2.8) in 2004–2006 (p=0.20), and remained steady to 2010–2012. The prevalence and incidence among African Americans were approximately twice that among European Americans.

CONCLUSIONS

The prevalence and incidence of AD dementia showed substantial variation between 1994 and 2012, but no secular trend.

INTRODUCTION

The possibility of systematic temporal trends in prevalence and incidence of clinically diagnosed Alzheimer’s disease (AD) dementia has received substantial recent attention. Although the evidence remains uncertain, several recent publications from the US and Europe have suggested decreases in the age-specific occurrence roughly over the last three decades.1-5 Such a trend toward decreased occurrence would be highly welcome because of the severe impact of the condition on the lives of affected people and their families, the major burdens it places on society, and increasing occurrence from population aging. Although African Americans (AAs) have higher prevalence and incidence of AD dementia than European Americans (EAs),6-7 trends data are lacking for AAs and other minority groups. We, therefore, tested the trends in the prevalence and incidence of AD dementia from 1994 to 2012 in 2,794 individuals from the Chicago Health and Aging Population (CHAP), a geographically defined population-based biracial study of AAs and EAs.

METHODS

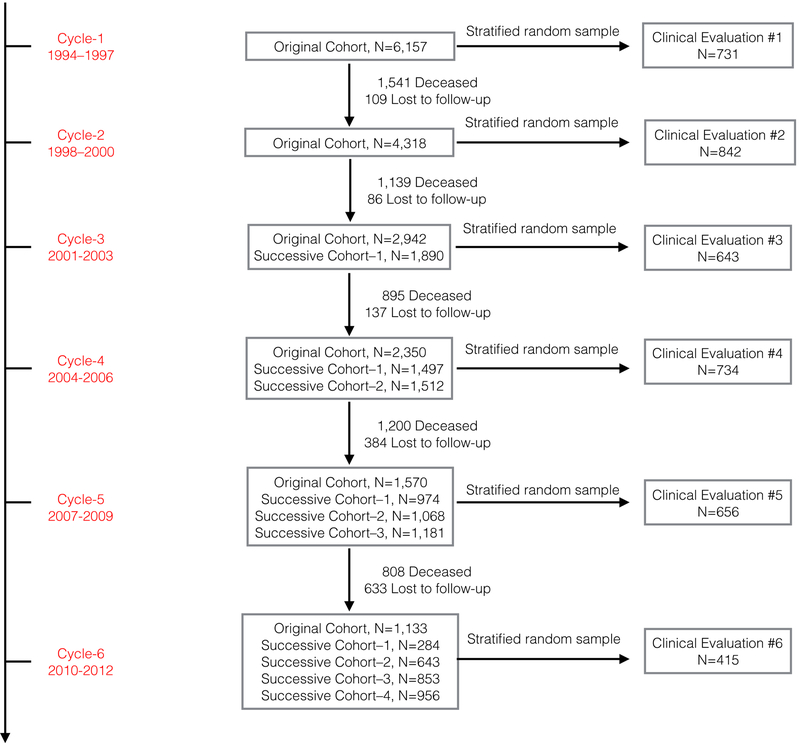

The CHAP study is a prospective population-based study of the epidemiology of AD dementia and related disorders among adults over the age of 65, which included six triennial data collection cycles.8 The study started in 1993 and followed and enrolled new participants until 2012. The recruitment for this study started with 78.7% of all residents over the age of 65 enrolling to participate in 1993, the first cycle of data collection. In each data collection cycles, thereafter, new participants were enrolled as successive cohorts. In total, the CHAP study enrolled 10,801 participants residing on the south side of Chicago. Neurocognitive tests were administered every three years for up to six times over the duration of the study. At each of these population assessments, a stratified random sample of participants was selected for a detailed clinical evaluation including clinical diagnosis of prevalent and incident AD dementia starting in 1994. A total of 2,794 participants were selected over the entire study duration (Figure 1). The Institutional Review Board of Rush University Medical Center approved the CHAP study. All participants also provided signed written informed consent.

Figure 1. The CHAP Study Design and Clinical Evaluations Sample Selection between 1994 and 2012.

The N in the study cohort shows the number eligible for the population interview to be selected for clinical evaluations. The N in the clinical evaluation shows the number of study participants with a clinical diagnosis for each triennial cycle. In CHAP study, a total of 4,021 clinical evaluations are performed on 2,794 participants between 1994 and 2012.

Clinical Diagnosis of AD Dementia

Examiners blinded to population interview cognitive testing and stratum of selected individuals performed uniform clinical evaluations between 1994 and 2012.9 The detailed clinical evaluations included a structured medical history, neurologic examinations, and a battery of 19 neurocognitive tests. A board-certified neurologist, who was blinded to previously collected tests, provided an AD and dementia diagnosis according to the NINCDS-ADRDA criteria.10 Clinically diagnosed AD dementia required a history of cognitive decline and evidence of impairment in memory and one or more other cognitive domains.

Statistical Analysis

The descriptive analysis was stratified by race, AAs vs. EAs, with sample-weight-adjusted means and standard errors for continuous demographic characteristics, and raw frequencies and weighted percentages for categorical measures.

Several steps were involved in the estimation and testing of the AD dementia trends. A carry forward approach was used to estimate the prevalence and incidence of AD dementia (Table S1 in Supplementary Appendix).11 The study design features included estimation of sampling weights based on age (5 groups – 65-69 years, 70-74 years, 75–79 years, 80-84 years, and 85 and older), sex (males vs. females), race (AAs vs. EAs), and three groups of memory scores based on East Boston Memory Test (low, medium, and high). More details on the design features of the study are provided in the Supplementary Appendix.

We estimated the average prevalence and incidence of AD dementia in the CHAP study using a weighted logistic regression model adjusting for age (four indicators with 65-69 as the reference category), sex (0 for males and 1 for females), and race (0 for European Americans and 1 for African Americans). The average prevalence and incidence specific to triennial cycles or three-year intervals included indicators for time-specific triennial cycles. The three-year intervals overlapped with clinical evaluations for prevalent and incidence AD dementia that was based on sample selection from recently completed population cognitive testing. More details on the parameterization are provided in Statistical Models in Supplementary Appendix.

A sample weighted delete-one jackknife approach was used to estimate quasi-binomial logistic regression-based parameter estimates and their standard errors.12 A stratified survey design with sampling weights and delete-one jackknife were implemented in R program using Survey package.13 After estimating the parameters of the regression models, study-specific estimates were standardized to the 2010 US census data. More details are provided in Standardization Algorithm in Supplementary Appendix. The demographic characteristics of the US population are also shown in Supplementary Table 2. The number of people living in the US with prevalent AD dementia and developing incident AD dementia was estimated using the count of US population over the age of 65 at specific calendar years and the prevalence and annual incidence of census standardized estimates during those calendar years. In a secondary analysis, we included the years of education in our regression model to study the role of education on our prevalence and incidence estimates, and to examine if the changes in education might be related to the secular trends in AD dementia.

RESULTS

Demographic Characteristics of the CHAP Sample

The average age at clinical diagnosis of AD dementia was 76.2 years and average participant education was 12.7 years (Table 1). About 60% of participants reported a history of hypertension, 9% reported having diabetes, and 10% reported a history of stroke. In general, AAs were about 1.4 years younger and had significantly lower global cognition than EAs. AAs also had less education, lower annual income, and reported higher levels of common chronic health conditions than EAs.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 2,794 African Americans (AAs) and European Americans (EAs) at the time of Clinical Diagnosis of AD Dementia in CHAP Study

| AAs N=1,561 |

EAs N=1,233 |

All Participants N=2,794 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y, mean (SE) | 75.6 (0.25) | 77.0 (0.32) | 76.2 (0.20) |

| Global cognition, mean (SE) | 0.07 (0.03) | 0.55 (0.03) | 0.26 (0.02) |

| Education, y, mean (SE) | 11.6 (0.15) | 14.4 (0.15) | 12.7 (0.12) |

| ≤ 12y, N, % | 1,091, 67% | 490, 34% | 1,581, 54% |

| 13–16y, N, % | 398, 27% | 521, 45% | 919, 34% |

| ≥ 17y, N, % | 70, 6% | 221, 21% | 291, 12% |

| Annual income | |||

| Less than 15,000, N, % | 526, 34% | 186, 14% | 712, 26% |

| 15,000-29,999, N, % | 590, 45% | 335, 28% | 925, 38% |

| Over 30,0000, N, % | 266, 21% | 567, 58% | 823, 36% |

| Females, N, % | 970, 66% | 740, 63% | 1710, 65% |

The sample weight adjusted mean and standard error of the mean are presented. Raw frequencies are presented, but the percentages are sample weight adjusted percentages

The sample weight adjusted demographic characteristics (age, female sex, and AA race/ethnicity) in each of the triennial cycles is shown in Table S3 in Supplementary Appendix. Briefly, the average age at clinical assessments varied between 76 and 80 years, the percentage of females between 59 and 71, and percentage of AAs between 54% and 68% over the 6 triennial clinical evaluations for AD dementia. These fluctuations make it important to stratify and/or adjust for demographic characteristics in our analysis, and standardize the study-specific estimates to the 2010 US census data.

Average Prevalence and Annual Incidence of AD dementia

After standardizing the CHAP estimates to 2010 US census data, the average prevalence of AD dementia was 14.5% (95% CI= 13.7, 15.3). The prevalence of AD dementia was nearly two-fold higher among AAs compared to EAs (27.0% vs. 13.3%). The age-specific prevalence of AD dementia increased from 3.2% (95% CI= 2.3, 4.1) among 65–74 years old to 52.1% (95% CI=48.5, 55.9) among those over 85 years old. The CHAP estimate of the average prevalence of AD dementia (23.5%) was higher than the census-standardized estimates, mostly, because of a larger number of AAs in the study. Nevertheless, the racial differences and age-specific increases in the average prevalence estimates were similar between study-specific and census-standardized estimates.

After standardizing the CHAP estimates to the 2010 US census data, the average annual incidence of AD dementia was 2.3% (95% CI= 1.7, 2.9) (Table 2). The average annual incidence of AD dementia increased drastically with age among 65–74 years old compared to those over 85 years old. Even after adjusting for 2010 US census age and sex distributions, the annual incidence of AD dementia was almost twice as high among AAs as among EAs (3.9% vs. 2.1%). The CHAP average annual incidence of AD dementia was 3.6% (95% CI= 3.3, 3.9), but the average annual incidence and age-specific annual incidence of AD dementia in the study population was still higher among AAs compared to EAs.

Table 2.

Overall Prevalence and Annual Incidence (95% Confidence Interval) of Clinically Diagnosed AD Dementia, by Age and Race

| Age, y | CHAP Prevalence | 2010 US Population Standardized Prevalence | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AAs | EAs | All Participants | AAs | Non-AAs | All Participants | |

| 65-74 | 9.3 (7.5, 11.0) | 2.1 (1.4, 2.8) | 5.5 (4.4, 6.6) | 11.4 (9.6, 13.2) | 3.2 (2.3, 4.1) | 3.2 (2.3, 4.1) |

| 75-84 | 38.2 (35.9, 40.6) | 14.9 (13.3, 16.4) | 28.1 (26.5, 30.0) | 38.4 (36.0, 40.8) | 15.4 (13.9, 16.9) | 16.3 (14.8, 17.8) |

| Over 85 | 78.4 (75.5, 81.3) | 49.5 (45.5, 53.5) | 69.3 (66.6, 72.0) | 78.9 (75.6, 82.3) | 47.0 (43.5, 50.5) | 52.1 (48.5, 55.9) |

| All Ages | 27.2 (25.6, 28.9) | 14.4 (13.2, 15.6) | 23.5 (22.6, 24.3) | 27.0 (25.4, 28.6) | 13.3 (12.3, 14.3) | 14.5 (13.7, 15.3) |

| Age, y | CHAP Annual Incidence | US Population Standardized Annual Incidence | ||||

| AAs | EAs | All Participants | AAs | Non-AAs | All Participants | |

| 65-74 | 1.5 (1.0, 2.0) | 0.3 (0.1, 0.6) | 0.7 (0.4, 1.0) | 1.5 (1.0, 2.0) | 0.3 (0.1, 0.5) | 0.4 (0.1, 0.6) |

| 75-84 | 5.9 (5.2, 6.7) | 3.0 (2.4, 3.4) | 4.4 (3.9, 4.8) | 6.0 (5.3, 6.7) | 2.9 (2.3, 3.4) | 3.2 (2.7, 3.7) |

| Over 85 | 11.8 (9.5, 14.1) | 7.4 (6.1, 8.8) | 9.8 (8.4, 11.0) | 11.7 (9.2, 14.1) | 7.4 (6.0, 8.8) | 7.6 (6.9, 9.8) |

| All Ages | 4.1 (3.7, 4.6) | 2.6 (2.3, 3.0) | 3.6 (3.3, 3.9) | 3.9 (3.1, 4.7) | 2.1 (1.6, 2.6) | 2.3 (1.7, 2.9) |

Time-Specific Prevalence and Incidence of AD dementia between 1994 and 2012

For better comparability, the time-specific CHAP estimates were also standardized to the 2010 US census demographic characteristics. After standardizing to the 2010 US census data, the prevalence of AD dementia was 14.6% (95% CI= 13.0, 16.2) in 1994–1997 and 14.7% (95% CI= 13.2, 16.2) in 2010–2012, (p=0.84) (Table 3). The US standardized prevalence of AD dementia showed variability over time: 16.5% (95% CI= 15.2, 18.3) in 1998–2000, 13.0% (95% CI= 11.3, 14.7) in 2007–2009, and 14.7% (95% CI= 13.2, 16.2) in 2010–2012. In essence, the prevalence of AD dementia showed variability over the years with increases and decreases over specific time intervals, but no secular evidence of a declining trend in the prevalence of AD dementia. A similar trend – an initial increase between 1994–1997 and 1998–2000, followed by a decrease until 2007–2009, which was followed by an increase in 2010–2012 was observed in the study-specific estimates, and among AAs and EAs, although in each of the study periods AAs had prevalence twice as high as EAs.

Table 3:

Time-Specific Age-Adjusted Prevalence and Annual Incidence (95% Confidence Interval) of Clinically Diagnosed AD Dementia between 1994 and 2012, by Race

| Years | CHAP Time-Specific Prevalence | 2010 US Census Standardized Prevalence | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AAs | EAs | All Participants | AAs | Non-AAs | All Participants | |

| 1994-1997 | 25.8 (23.1, 28.6) | 14.1 (12.3, 15.9) | 20.6 (18.2, 22.9) | 27.2 (24.3, 30.1) | 13.3 (11.6, 15.1) | 14.6 (13.0, 16.2) |

| 1998-2000 | 29.3 (26.8, 31.8) | 16.5 (14.8, 18.2) | 23.5 (21.4, 25.7) | 30.8 (28.2, 33.4) | 15.4 (13.9, 17.3) | 16.5 (15.2, 18.3) |

| 2001-2003 | 26.1 (23.9, 28.5) | 14.3 (12.6, 16.0) | 20.8 (18.8, 22.9) | 27.5 (25.1, 30.0) | 13.6 (11.9, 15.2) | 14.8 (13.1, 16.5) |

| 2004-2006 | 25.6 (23.2, 27.9) | 12.8 (11.2, 14.3) | 19.8 (17.8, 21.8) | 25.1 (22.8, 27.4) | 12.1 (10.6, 13.5) | 13.2 (11.7, 14.8) |

| 2007-2009 | 26.0 (23.2, 28.7) | 12.3 (10.6, 14.0) | 19.8 (17.6, 22.0) | 24.3 (21.7, 27.0) | 12.1 (10.3, 13.6) | 13.0 (11.3, 14.7) |

| 2010-2012 | 30.0 (26.6, 33.5) | 14.9 (12.6, 17.1) | 23.2 (20.3, 26.2) | 27.0 (25.0, 29.0) | 13.5 (12.2, 14.8) | 14.7 (13.2, 16.2) |

| CHAP Time-Specific Annual Incidence | 2010 US Census Standardized Annual Incidence | |||||

| AAs | EAs | All Participants | AAs | Non-AAs | All Participants | |

| 1998-2000 | 4.9 (4.0, 5.8) | 3.0 (2.4, 3.6) | 4.1 (3.3, 4.8) | 5.3 (4.3, 6.2) | 2.7 (2.2, 3.2) | 2.8 (2.2, 3.2) |

| 2001-2003 | 4.1 (3.2, 4.9) | 2.3 (1.8, 2.9) | 3.3 (2.6, 4.0) | 4.3 (3.4, 5.2) | 2.2 (1.7, 2.8) | 2.4 (1.8, 3.0) |

| 2004-2006 | 4.0 (3.1, 4.8) | 2.1 (1.6, 2.6) | 3.1 (2.4, 3.8) | 3.9 (3.0, 4.8) | 2.0 (1.5, 2.5) | 2.2 (1.7, 2.7) |

| 2007-2009 | 3.7 (2.6, 4.6) | 1.9 (1.3, 2.5) | 2.8 (2.1, 3.5) | 3.4 (2.3, 4.3) | 2.0 (1.4, 2.6) | 2.1 (1.6, 2.7) |

| 2010-2012 | 4.3 (3.1, 5.5) | 2.2 (1.4, 2.9) | 3.3 (2.4, 4.3) | 4.1 (2.9, 5.2) | 2.1 (1.4, 2.7) | 2.2 (1.6, 2.8) |

The CHAP study estimates of the annual incidence of AD dementia were also standardized to US census data (Table 3). The census-standardized estimate of annual incidence of AD dementia was 2.8% (95% CI= 2.2, 3.2) in 1998–2000 and 2.2% (95% CI= 1.6, 2.8) in 2010–2012, (p=0.20). In essence, the annual incidence of AD dementia showed a questionable decline, with most of this apparent decline between 1998–2000 and 2004–2006, and stable estimates thereafter. The study-specific annual incidence was slightly higher than census-standardized estimates but showed a similar pattern of change over time. The change in annual incidence of AD dementia was similar in AAs and EAs over the study period. The study-specific annual incidence of AD dementia among AAs decreased by 0.6% from 1998–2000 to 2010–2012, and among EAs decreased by 0.8% from 1998–2000 to 2010–2012.

Number of People in the US with Prevalence and Incidence of AD dementia

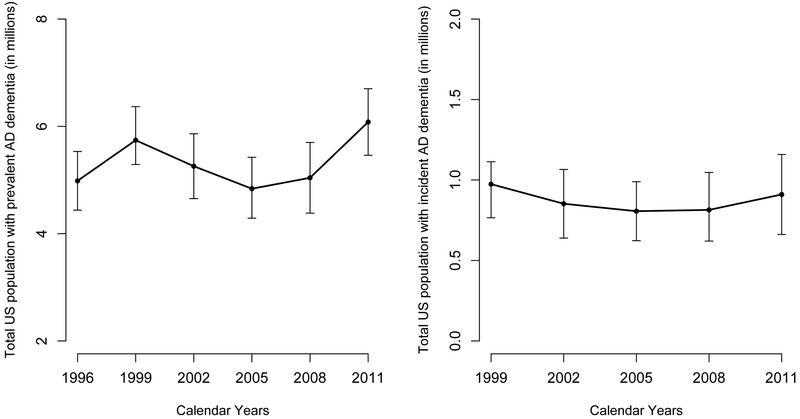

If the CHAP study estimates were to be projected to the US population, we estimate that about 4.9 (4.3, 5.5) million Americans had AD dementia in 1996, which increased to 6.1 (5.5, 6.7) million in 2011 (Figure 2). An estimated 4.8 (4.3, 5.4) million had AD dementia in 2005, which was the lowest over the entire study duration. For annual incidence of AD dementia, 974,340 (765,553 – 1,113,531) Americans developed incident AD dementia in 1999, which decreased to 806,296 (623,046 – 989,544) Americans in 2008. However, the projected number of Americans developing AD dementia increased to 910,051 (661,855 – 1,158,247) in 2011, slightly lower than the 1999 count, showing considerable variability over the years.

Figure 2. Estimated Number of Individuals (95% Confidence Interval) Living in the US with Prevalent AD Dementia and Developing Incident AD Dementia in Specific Years between 1994 and 2012.

The number of people with prevalent and developing incident AD in millions and the 95% confidence limits for these counts is shown in the two panels. The left panel shows the number of people with prevalent AD dementia. The right panel shows the number of people with incident AD dementia. The estimated numbers are estimated based on the CHAP study sample.

As a secondary analysis, the inclusion of education in our regression model increased the prevalence of AD dementia slightly from 14.6% to 14.7%, mostly since the average education was lowest during our first triennial cycle (1994-1996), but did not significantly change the incidence estimates or the time-specific trends in later years.

DISCUSSION

Our findings indicate that the prevalence of AD dementia showed considerable temporal variability over an 18-year study, from 1994 to 2012. At certain time intervals, the prevalence of AD dementia appeared to increase or decrease, but no sustained temporal trends were observed. We employed multiple ways of measuring the occurrence of AD dementia: prevalence and annual incidence figures both for our specific study and standardized to the US census, prevalence and incidence estimates for AA and EA racial/ethnic groups, and prevalence and incidence estimates for three broad age groups. Similar patterns and absence of a sustained temporal trend were consistently seen for each of those measures.

Several studies have reported a decline in the age-specific prevalence of dementia over recent years,3-5 but some issues may benefit from further investigation. Typically the reported trends were estimated from measures of AD dementia prevalence at two points only, 2000 and 2012,3 and 1989–1994 and 2008–2011.5 The substantial variation in prevalence and incidence over time that we observed is unlikely to be a feature of only our study. The results obtained from restricting our analysis to only pairs of the multiple points available would have differed substantially from one another depending on the points selected. Some of the differences in prevalence seen previously from which trends were estimated are large and may be unlikely to be sustained over time. A point of rough similarity between some of the results of these studies and our results is that sometimes’2,16 the decrease in the occurrence of AD dementia appeared to be early in the period of observation and to be followed by a period of stability, roughly similar to the pattern of non-significant variations we observed. Most notably, the Framingham study reported substantial decreases in incidence rates between late 1970s to early 1980s and late 1990s to early 2000s, but the incidence in late 2000s to early 2010s was similar to the late 1990s to early 2000s.2

The Stockholm Study15 showed no decrease in the prevalence of AD dementia, as did the Indianapolis Ibadan study16 in an urban US population sample. Earlier reports from the CHAP study,17 and the Bordeaux Study18 showed no significant trends in the annual incidence of clinically diagnosed AD dementia. Also, the previous CHAP report17 did not provide time-specific prevalence and incidence rates of AD dementia and did not standardize the estimates to the 2010 US census data. The previous studies and our study do not directly consider population aging and its effects on AD dementia occurrence. As the risk of the condition is very strongly related to age,19 the continuing dramatic increases in size the oldest population age groups20 is a major driver of projected future estimates of the condition.19,21 It seems highly desirable to integrate the varying estimates of age-specific trends with projections of population aging, about which there is substantial agreement, even before the debate about which trends are most likely is settled. We also showed that even if the prevalence of AD dementia remained steady over the years, the estimated number of Americans affected by AD dementia is bound to increase significantly over time.

The CHAP study has several strengths and weaknesses. The major strengths of this study are the size of the study, population-based design in a clearly defined and well-characterized sample of a community dwellers, large number of AAs and EAs for meaningful analysis race comparisons, six cycles of data collection spanning almost two decades, a strong effort to ensure consistent study procedures over its entire duration, and use of a carry forward method that accounted for the increased lifespan of people with dementia through cross-referencing to date of death using the National Death Index.

Several limitations of our study also need to be noted. The biracial CHAP study is a population sample of residents living in four urban neighborhoods on the south side of Chicago and may not generalize well to the US population. The biracial nature of this study made standardization to US population much harder to interpret. To resolve this issue, we classified the US population into two broad race/ethnic groups – AAs (non-Hispanic AAs), and combined non-Hispanic white and Hispanic white and all other races into the EAs and others category. This would make our overall US census adjusted estimates conservative since Hispanic whites have higher prevalence and incidence of AD dementia than non-Hispanic whites.22-23 The standardization of our estimates to the US population provides some degree of comparability with nationally representative estimates. The inclusion of years of education slightly increased our prevalence estimate in 1994-1996, but did not impact later cycle estimates as education remained steady. We did not investigate the role of vascular factors on prevalence and incidence of AD dementia, and will be a topic of interest for future investigations. Despite our efforts to ensure consistent procedures over the life of the study, substantial temporal variation in the prevalence and incidence estimates for AD dementia was observed. The operational methodology for forming these estimates is known to be challenging, but it is not clear how much the variation reflects these general challenges and how much it reflects issues peculiar to our study.

Our findings suggest that the prevalence and annual incidence of AD dementia may have shown some decline during certain time intervals, but the changes through the study period were not consistent to conclude a secular trend. In conclusion, a closer monitoring of the prevalence and annual incidence of AD dementia in epidemiologic studies with strong study designs, and clinical diagnosis of AD or comprehensive surveillance tools are needed to monitor the secular changes in prevalence and incidence of AD dementia over the next two decades.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Estimated the prevalence and incidence of AD dementia in a population study and standardized to 2010 US census data.

The overall prevalence of AD dementia was 14.5% and incidence was 2.3% after standardization to the 2010 US census data.

Prevalence and incidence of AD dementia showed variability, but no secular decline in trends between 1994 and 2012.

Future surveillance needed to study variations in AD dementia trends.

Acknowledgment:

This research was supported by NIH grants RF1-AG057532 (K.B.R.), R01-AG051635 (K.B.R.) and R01-AG11101 (D.A.E.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial Disclosure: The authors report no disclosure relevant to this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Prince M, Ali GC, Guerchet M, Prina AM, Albanese E, Wu YT. Recent global trends in the prevalence and incidence of dementia, and survival with dementia. Alzheimers Res Ther 2016;8:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Satizabal CL, Beiser AS, Chouraki V, Chêne G, Dufouil C, Seshadri S. Incidence of Dementia over Three Decades in the Framingham Heart Study. N Engl J Med 2016;374:523–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Langa KM, Larson EB, Crimmins EM, et al. A Comparison of the Prevalence of Dementia in the United States in 2000 and 2012. JAMA Intern Med 2017;177:51–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lobo A, Saz P, Marcos G, et al. Prevalence of dementia in a southern European population in two different time periods: the ZARADEMP Project. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2007;116:299–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matthews FE, Arthur A, Barnes LE, et al. A two-decade comparison of prevalence of dementia in individuals aged 65 years and older from three geographical areas of England: results of the Cognitive Function and Ageing Study I and II. Lancet 2013;382:1405–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steenland K, Goldstein FC, Levey A, Wharton W. A meta-analysis of Alzheimer’s disease incidence and prevalence comparing African Americans and Caucasians. J Alzheimers Dis 2015;50:71–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Evans DA, Bennett DA, Wilson RS, Bienias JL, et al. Incidence of Alzheimer disease in a biracial urban community. Arch Neurol 2003;60:185–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bienias JL, Beckett LA, Bennett DA, Wilson RS, Evans DA. Design of the Chicago Health and Aging Project. J Alz Dis 2003;5:349–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilson RS, Bennette DA, Bienias JL, et al. Cognitive activity and incident AD in a population-based sample of older adults. Neurology 2002;59:1910–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan M. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology 1984;34:939–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brookmeyer R, Evans DA, Hebert L, et al. National estimates of the prevalence of Alzheimer's disease in the United States. Alzheimers Dement 2011;7: 61–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lumley T Analysis of complex survey samples. Journal of Statistical Software 2004;9(1):1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lumley T Survey: analysis of complex survey samples". R package version 3.31–5. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gao S, Ogunniyi A, Hall KS, et al. Dementia incidence declined in African-Americans but not in Yoruba. Alzheimers Dement 2016;12:244–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qiu C, von Strauss E, Backman L, Winblad B, Fratiglioni L. Twenty-year changes in dementia occurrence suggests decreasing incidence in central Stockholm, Sweden. Neurology 2013;80:1888–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rocca WA, Petersen RC, Knopman DS, et al. Trends in the incidence and prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease, dementia, and cognitive impairment in the United States. Alzheimers Dement 2011;7:80–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hebert LE, et al. Change in risk of Alzheimer disease over time. Neurology 2010;75:786–791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grasset L, Brayne C, Joly P, et al. Trends in dementia incidence: evolution over a 10-year period in France. Alzheimers Dement 2016;12:272–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hebert LE, Weuve J, Scherr PA, Evans DA. Alzheimer disease in the United States (2010–2050) estimated using the 2010 Census. Neurology 2013;80:1778–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Colby SL, Ortman JM. Projections of the size and composition of the US population: 2014 to 2060. www.census.gov Accessed June 10th, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prince M, Bryce R, Albanese E, Wimo A, Ribeiro W, Ferri CP. The global prevalence of dementia: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9:63–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haan MN, Mungas DM, Gonzalez HM, Ortiz TA, Acharya A, Jagust WJ. Prevalence of dementia in older latinos: The influence of type 2 diabetes mellitus, stroke and genetic factors. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003;51:169–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Samper-Ternent R, Kuo YF, Ray LA, Ottenbacher KJ, Markides KS, Al Snih S. Prevalence of health conditions and predictors of mortality in oldest old Mexican Americans and non-Hispanic whites. J Am Med Dir Assn 2012;13(3):254–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.