Abstract

Comparisons between observed data and model simulations represent a critical component for establishing confidence in population physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (Pop-PBPK) models. Numerical predictive checks (NPC) that assess the proportion of observed data that correspond to Pop-PBPK model prediction intervals (PIs) are frequently used to qualify such models. We evaluated the effects of 3 components on the performance of NPC for qualifying Pop-PBPK model concentration-time predictions: (1) correlations (multiple samples per subject), (2) residual error, and (3) discrepancies in the distribution of demographics between observed and virtual subjects. Using a simulation-based study design, we artificially created observed pharmacokinetic (PK) datasets and compared them to model simulations generated under the same Pop-PBPK model. Observed datasets containing uncorrelated and correlated observations (+/− residual error) were formulated using different random-sampling techniques. In addition, we created observed datasets where the distribution of subject body weights differed from that of the virtual population used to generate model simulations. NPC for each observed dataset were computed based on the Pop-PBPK model’s 90% PI. NPC were associated with inflated type-I-error rates (>0.10) for observed datasets that contained correlated observations, residual error, or both. Additionally, the performance of NPC were sensitive to the demographic distribution of observed subjects. Acceptable use of NPC was only demonstrated for the idealistic case where observed data were uncorrelated, free of residual error, and the demographic distribution of virtual subjects matched that of observed subjects. Considering the restricted applicability of NPC for Pop-PBPK model evaluation, their use in this context should be interpreted with caution.

Keywords: physiologically based pharmacokinetic, model evaluation, numeric predictive check, prediction interval, simulation-based study

Introduction

Through their biologically relevant structure and mechanistic design, physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) models aim to provide comprehensive estimates of drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) within an organism. PBPK models strategically segregate parameters between those that are drug and system (organism) specific. Based on an understanding that drug-specific parameters are fixed, system-specific parameters can be modified to produce predictions specific to an organism of interest [(1). With the inclusion of stochastic population algorithms within PBPK modeling software platforms, users can generate complete sets of system-specific parameters for virtual populations of individuals based on tertiary demographic information such as age, weight, height, sex, and race. By integrating knowledge and inferences regarding biological variability in humans, such algorithms permit for the creation of realistic populations of subjects that vary in terms of anatomy (e.g., organ weights) and physiology (e.g., blood flows) (2). Population PBPK (Pop-PBPK) models perform pharmacokinetic (PK) simulations for each member of these virtually generated populations. Such simulations are inferred to provide assessments of the average tendency and extent of variability of compound PK for real-world subjects who conform to demographics that are similar to those of the virtual population. Though comparisons of model simulations to observed data is considered a critical component for establishing confidence in model predictions, there remains a lack of consistency as to how PBPK models are evaluated within literature (3).

To assess the quality of concentration-time predictions garnered by Pop-PBPK models, visual predictive checks (VPC) and numerical predictive checks (NPC) are typically employed (1). Based on current Pop-PBPK model evaluation practices, predicted percentiles (e.g., 5th and 95th) of concentration-time values are computed for a virtual population whose demographics resemble those of observed subjects. VPC, which are qualitative in nature, graphically compare observed concentrations to model-predicted percentiles (4). In contrast, NPC quantitatively compare the proportion of observed data that corresponds to model-simulated percentiles with their expected proportion. The proportion of observed data falling outside the model’s 90% prediction interval (PI) represents a commonly used NPC for assessing model quality (5, 6). For suitable models, the proportion of observed data exceeding model-based percentiles should be congruent to the expected proportion (e.g., 10% of observations are expected to exceed the model’s 90% PI). Though several publications have employed NPC to qualify Pop-PBPK model predictions (5–7), their suitability for evaluating such models has, to our knowledge, never been assessed.

Using a simulation-based design, we aimed to evaluate the performance of NPC for qualifying Pop-PBPK model plasma concentration-time predictions. Specifically, the analysis will evaluate the effects of 3 components on the utility of currently implemented NPC used for Pop-PBPK model qualification: (1) correlation (i.e., multiple PK samples per patient), (2) random residual error, and (3) discrepancies in the distribution of demographics between observed and virtual subjects.

Methods

The performance of NPC based on the 90% PI was evaluated using artificially created observed and simulated datasets generated under the same Pop-PBPK model. Model parametrization and specific considerations pertaining to the creation of observed datasets are depicted below.

Software

Pop-PBPK modeling was performed in PK-Sim® (version 7.2, http://open-systems-pharmacology.org). All graphical plots and data management (e.g., formatting) were performed in R (version 3.4.3, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and RStudio (version 1.1.383, RStudio, Boston, MA, USA) with the ggplot2, cowplot, xlsx, and rlist packages. The piecewise cubic hermite interpolating polynomial (pchip) function from the pracma package in R was used for all data interpolations. The quantile function from the stats package in R was used to compute percentiles for model simulations. Exact binomial tests were performed using the binom.test function from the stats package in R.

Compound physico-chemistry and ADME

Pop-PBPK model simulations were generated for a theoretical compound whose physico-chemical and ADME properties are defined in Table 1. Tissue-to-plasma partition coefficients (Kp) were estimated using the in-silico tissue-composition-based approach as presented by Rodgers and Rowland (8–10). Fraction unbound in plasma was 0.10. Albumin represented the only plasma binding partner. Metabolism was exclusively modulated by hepatic CYP3A4 using a first-order intrinsic clearance (CLint,3A4 = 0.25 L/min/umol CYP3A4). No additional pathways (e.g., glomerular filtration) contributed to drug clearance. Based on the abovementioned parameterization, an initial simulation conducted in PK-Sim® depicting administration of a 100 mg intravenous bolus dose to a 30-year-old white American male (80.4 kg, 178.5 cm) displayed a whole-blood clearance of 3.5 mL/min/kg. As such, the theoretical compound was classified as a low extraction ratio (ER) drug (hepatic ER = 0.17).

Table 1:

Compound physico-chemistry and ADME information for the theoretical compound

| Physico-chemistry | LogP pKa MW fup |

2.5 NA (neutral) 350 g/mol (0 halogens) 0.1 |

| ADME | Binding protein CLint,3A4 (hepatic) |

Albumin 0.25 L/min/umol CYP3A4 |

LogP, logarithm of the octanol-water partition coefficient (lipophilicity); pKa, negative logarithm of the acid dissociation constant; MW, molecular weight; fup, plasma fraction unbound; CLint,3A4, intrinsic clearance intrinsic clearance of (hepatic) isozyme CYP3A4.

Virtual population demographics

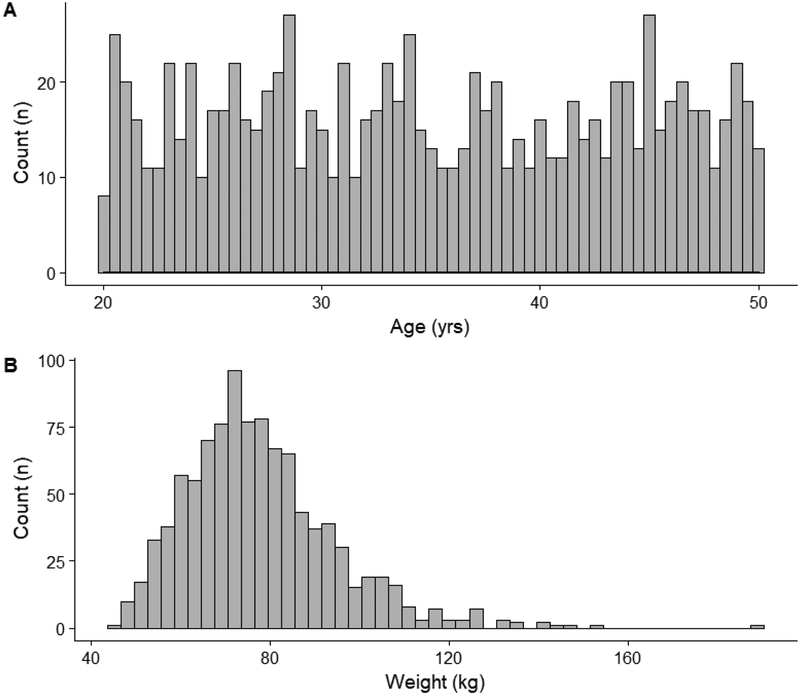

Using the population module in PK-Sim®, an adult virtual population consisting of 1000 individuals was generated. The age of virtual subjects ranged between 20–49 years and followed a uniform distribution. The male-to-female ratio was 50:50. Subjects were generated based on the demographics of a white American population. Of note, in addition to the anatomical and physiologic variability associated with organ volumes and perfusion rates, the population module in PK-Sim® implicitly introduced variability towards plasma protein concentrations and hepatic intrinsic clearance values. The magnitude of this variability is based on prior physiologic knowledge pertaining to the specific plasma protein (i.e., albumin) and hepatic isozyme (i.e., CYP3A4) defined in the model (11). Figure 1 depicts the distribution of ages and weights for the generated virtual population.

Fig 1.

Age and weight distribution (A and B, respectively) of the generated adult virtual population (n=1000)

Generation of observed data

Observed datasets were artificially generated based on the results of a Pop-PBPK simulation using the above-described theoretical compound and adult virtual population (n=1000). All subjects were administered a 100 mg dose via an intravenous bolus (i.e., instantaneous administration). Peripheral venous plasma drug concentrations estimated by the Pop-PBPK model were imported into R, where separate observed PK datasets were generated. By applying specific sampling strategies for subject selection and PK sample collection, observed datasets based on uncorrelated (i.e., one sample per patient) and correlated (i.e., multiple samples per patient) study designs, as well as designs where the distribution of weight between observed and virtual subjects differed (i.e., modified sampling distribution) were created.

Uncorrelated datasets:

For uncorrelated datasets, we employed a stratified random sampling strategy to select 40 subjects. The sampling technique divided the virtual population (n=1000) into 3 segments based on age: 20–29, 30–39, and 40–49 years. Approximately equal numbers of subjects were selected from each segment. Reselection of subjects was prohibited. Additionally, the sampling method was constrained to select an equal proportion of males and females. The implemented selection strategy ensured that the demographic composition (i.e., age, sex, body weight, etc.) of observed datasets matched that of the virtual population. Selected subjects were randomly assigned to a single sample collection interval as defined in Table 2. Within each collection interval, the specific time of PK sampling was randomly selected. Observed data were generated by interpolating PBPK model-simulated concentrations at the selected random sampling time point for each subject. Based on this design, each subject contributed only one PK sample towards the analysis (i.e., 40 subjects; 40 PK samples).

Table 2:

Random sampling intervals used to generate observed data

| Sampling Interval | Time |

|---|---|

| A | 5–30 mins |

| B | 1–2 hrs |

| C | 3–4 hrs |

| D | 5–7 hrs |

| E | 9–12 hrs |

| F | 16–24 hrs |

Correlated datasets:

For correlated datasets (multiple PK samples per subject), we used a similar stratified random-sampling strategy to select 12 subjects. The number of PK samples each subject contributed was randomly assigned based on the following scheme: 5 samples (2 subjects), 4 samples (3 subjects), 3 samples (4 subjects), and 2 samples (3 subjects). For each subject, individual samples were randomly allocated to separate collection intervals (Table 2). The time of PK sampling within an interval was randomly selected. Similar to above, the output of PBPK model simulations was interpolated at the selected time points for each subject to generate observed data. Based on this sampling design, each correlated dataset contained a total of 40 PK samples from 12 selected subjects.

Modified sampling distribution datasets:

Four observed datasets, each incorporating a different sampling distribution for patient selection, were created to assess the influence of demographic (e.g., weight) discrepancies between observed and simulated (virtual) subjects on the performance of NPC. For each dataset, subjects were selected from a subset of the generated virtual population based on weight (kg). To minimize the influence of individuals with extreme weight values on the analysis, virtual subjects with weights >120 kg were excluded from the virtual population. The geometric mean (GEOMEAN) and log-normal standard deviation (LNSD) of weight for the remaining 977 virtual subjects in the truncated virtual population was 75 kg and 0.19, respectively. Subject selection among the 4 datasets was facilitated using the different sampling distributions to randomly generate body weight values: (1) log-normal distribution with the same GEOMEAN (75 kg) and LNSD (0.19) as the truncated virtual population, (2) log-normal distribution with the same GEOMEAN but half the associated variability (LNSD=0.09), (3) log-normal distribution with the same GEOMEAN but twice the associated variability (LNSD=0.38), and (4) uniform distribution. Virtual subjects with body weights closest to the randomly generated values were included in the observed dataset. As an added constraint, the difference in body weight between the selected virtual subject and the randomly generated value was required to be ≤1 kg. The sampling strategy was constrained to prevent subject reselection. Using this approach, 40 subjects were selected from the truncated virtual population for each observed dataset. Similar to the procedures described for the uncorrelated dataset, each selected subject was assigned to contribute a single PK sample towards the analysis (i.e., each dataset contained 40 subjects; 40 PK samples).

Evaluation procedure

For each data type (uncorrelated, correlated, and modified sampling distribution), 1000 replicate observed datasets were generated and compared to the model’s 90% PI. The interval was defined by the 5th and 95th percentiles of Pop-PBPK model-simulated plasma concentrations at each time point. For analysis of uncorrelated and correlated datasets, the model’s 90% PI was computed based on simulations for all 1000 virtual subjects; whereas, for datasets created using modified sampling distributions, the model’s 90% PI was computed for the 977 virtual subjects with body weights ≤120 kg. For each observed dataset, the proportion of observations falling outside the model’s 90% PI was computed based on Equation 1.

| (1) |

Where N is the total of number concentrations in the observed dataset, yi,tobs is ith observed concentration at time t, y5,tsim is the 5th percentile of simulated concentrations at time t corresponding to the virtual population, and y95,tsim corresponds to the 95th percentile of simulated concentrations at time t.

Current use of percentile-based NPC for Pop-PBPK model qualification implicitly assumes that observations are independent and each have an equal chance of exceeding model-simulated PI. For a fixed number of observations (i.e., trials), the amount of data points falling outside a model’s PI is therefore expected to follow a binomial distribution. Correspondingly, NPC for each replicate dataset were computed using the exact binomial test to evaluate if the proportion of observations falling outside the model’s 90% PI was statistically greater than the expected proportion (0.10). Statistical significance was asserted using a p-value <0.05. As both model simulations and observed data were generated under the same Pop-PBPK model, the rate of statistically significant results over all observed datasets was interpreted as an approximation of the type-I-error rate (i.e., incorrectly asserting that the data and model are incongruent). Computed type-I-error rates were compared to a nominal value of 0.05. Next, we graphically compared the distribution of observations that exceeded the model’s 90% PI, over all replicate datasets, to that of a binomial distribution (n=40, p=0.10). For instances where model simulations provide an appropriate depiction of observed data, as is the case in the current study, the distribution of observed datasets should conform to a binomial distribution if the proposed NPC is appropriate for model qualification. In contrast, divergence between the two distributions indicates inferiority of the proposed NPC. Additionally, for each data type, we computed the total number of replicate observed datasets where the proportion of observations falling outside the model’s 90% PI exceeded 10% (i.e., the expected proportion). This value provided an indication of how often a simple NPC, which did not apply any formal statistical test, would convey discordance between model simulations and observations.

For uncorrelated and correlated datasets, the analysis also examined the effect of adding residual variability towards observed concentration values on NPC performance. To facilitate this assessment, a proportional residual variability of 20% was added to observed datasets using Equation 2.

| (2) |

Where Cobs,error is the observed concentration value with residual error added, Cobs is the observed concentration value without error, and εprop is the proportional random error. In congruence to current PBPK modeling practices, where residual error is not accounted for, observed datasets (uncorrelated and correlated) with added residual error were compared to 90% PI(s) generated from Pop-PBPK model simulations that do not incorporate residual error.

Results

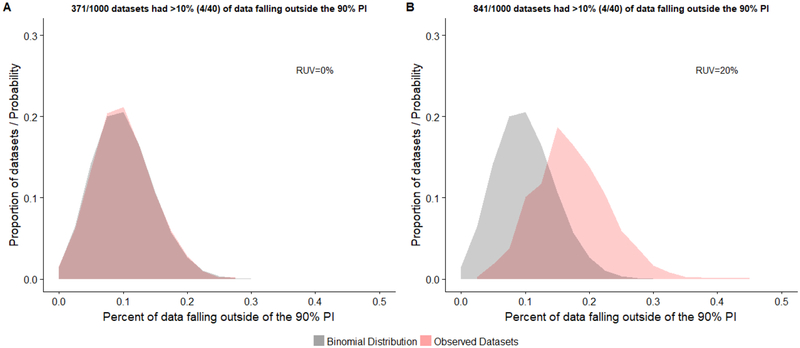

The utility of NPC for qualifying Pop-PBPK model predictions against observed datasets that were generated under the same model was assessed for each data type (Figures 2, 3, and 4). For uncorrelated datasets (i.e., 40 samples from 40 subjects) devoid of residual error, 37.1% of replicates had >10% of plasma concentrations falling outside the model’s 90% PI. This value increased to 84.1% of replicates when a 20% proportional residual error was introduced. A binomial distribution with an event success rate (p) of 0.1 provided an appropriate depiction of the distribution of uncorrelated datasets without residual error (Figure 2A). The computed type-I-error rate associated with use of the exact binomial test was in close agreement with the nominal value (Table 3). However, when residual error was added, the distribution of replicates shifted away from the depicted binomial distribution (right shift), indicating that the model’s 90% PI underestimated the magnitude of observed variability (Figure 2B). Correspondingly, the type-I-error rate was inflated (0.372; Table 3).

Fig 2.

Distribution of the proportion of observed concentrations falling outside the model’s 90% prediction interval (PI) for uncorrelated data (1000 replicates). Generated observed datasets consisted of 40 concentrations values from 40 different subjects. Distributions are depicted for observed datasets without (A) and with (B) a proportional residual unspecified variability (RUV) of 20%. The probability density for a binomial distribution with an event success rate (p) of 0.1 is displayed for reference.

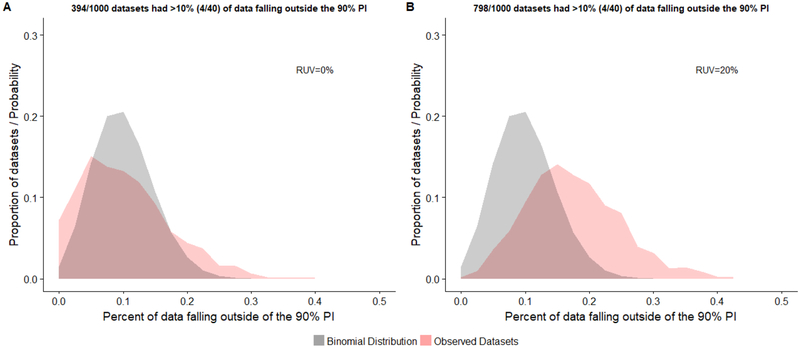

Fig 3.

Distribution of the proportion of observed concentrations falling outside the model’s 90% prediction interval (PI) for correlated data (1000 replicates). Generated observed datasets consisted of 40 concentrations values from 12 patients. Distributions are depicted for observed datasets without (A) and with (B) a proportional residual unspecified variability (RUV) of 20%. The probability density for a binomial distribution with an event success rate (p) of 0.1 is displayed for reference.

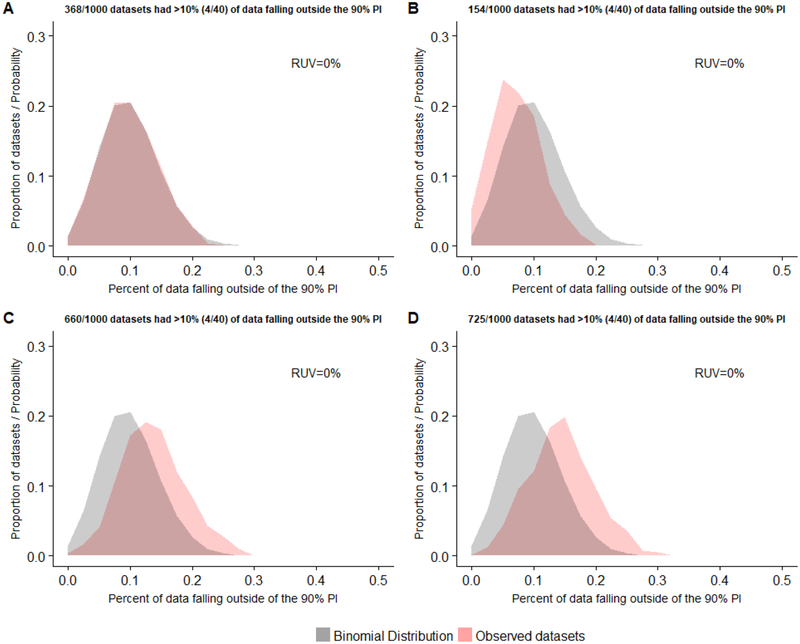

Fig 4.

Distribution of the proportion of observed concentrations falling outside the model’s 90% prediction interval (PI) for data generated using 4 different sampling distributions for patient selection (by body weight): (A) log-normal distribution with GEOMEAN = 75 kg and LNSD = 0.19, (B) log-normal distribution with GEOMEAN = 75 kg and LNSD = 0.09, (C) log-normal distribution with GEOMEAN = 75 kg and LNSD = 0.38, and (D) uniform distribution. One-thousand replicate datasets consisting of 40 samples from 40 subjects were created using each sampling distribution. Observed datasets did not include residual unspecified variability (RUV). The probability density for a binomial distribution with an event success rate (p) of 0.1 is displayed for reference.

Table 3:

Type-I-error rates for NPC based on the 90% PI

| Uncorrelated datasets (40 samples from 40 subjects) | ||

| Residual error | Type-I-error ratea | |

| 0 % | 0.042 | |

| 20% | 0.372 | |

| Correlated datasets (40 samples from 12 subjects) | ||

| Residual error | Type-I-error ratea | |

| 0 % | 0.125 | |

| 20% | 0.401 | |

| Modified sampling distribution datasets (40 samples from 40 | ||

| subjects; 0% residual error) | ||

| Subject selection sampling distribution | Type-I-error ratea | |

| Log-Normal (GEOMEAN = 75kg, LNSD = 0.19) | 0.034 | |

| Log-Normal (GEOMEAN = 75kg, LNSD = 0.09) | 0.002 | |

| Log-Normal (GEOMEAN = 75kg, LNSD = 0.38) | 0.167 | |

| Uniform | 0.201 | |

Represents the proportion of replicate datasets (n=1000) were the amount of data falling outside the model’s 90% PI was statistically greater than 10% based on the exact binomial test. Statistical significance was adjudged using a P value of <0.05.

For correlated datasets (i.e., 40 samples from 12 subjects) without residual error, 39.4% of replicate observed datasets had >10% of concentration values falling outside the model-defined PI. Similar to the uncorrelated case, the addition of residual error increased the amount of replicates where >10% of observations fell outside the 90% PI (79.8%). The distribution of correlated datasets without residual error was graphically dissimilar to that of the depicted binominal distribution (Figure 3A). With the addition of residual error, the distribution of datasets displayed a shift towards the right of the binomial distribution (Figure 3B), similar to that described above. Computed type-I-error rates associated with the exact binomial test were 0.125 and 0.401 for correlated datasets with and without residual error, respectively (Table 3).

When used to evaluate model performance against observed datasets that were uncorrelated (i.e., 40 samples from 40 subjects), devoid of residual error, and comprised of subjects where the distribution of body weight varied, NPC based on the 90% PI exhibited dissimilar results. For replicate observed datasets where the sampling distribution employed for subject selection mirrored the log-normal body weight distribution of the virtual population (i.e., LNSD = 0.19), 36.8% of replicates had >10% of concentration values falling outside the model’s 90% PI. The distribution of these replicates paralleled that of the binomial distribution (Figure 4A). The type-I-error rate among replicate datasets was 0.034 (Table 3).

For observed datasets where subjects were selected based on body weight using a sampling distribution with half the associated variability (i.e., LNSD = 0.09) compared to the virtual population, only 15.4% had >10% of data points falling outside the 90% PI. The distribution of replicates exhibited a shift towards the left of the theoretical binomial distribution, indicating a tendency of the model’s 90% PI to overestimate the extent of variability within observed datasets (Figure 4B).

Accordingly, the computed type-I-error rate (0.002) was considerably less than the nominal value of 0.05 (Table 3).

When a sampling distribution with twice the associated variability (i.e., LNSD = 0.38) compared to the virtual population was employed for subject selection, 66% of observed datasets had >10% of data points outside the model’s 90% PI. The distribution of replicates shifted towards the right of the theoretical binomial distribution, indicating a propensity of the model’s 90% PI to underestimate the extent of variability within observed datasets (Figure 4C). Here, the type-I-error was inflated (0.167) in comparison to the nominal rate (Table 3).

Finally, for datasets that employed a uniform sampling distribution for subject selection, 72.5% of datasets had a >10% of concentration values exceeding the 90% PI. Compared to the theoretical binomial, the distribution of replicates displayed a rightward shift, conveying that the 90% PI underestimated the magnitude of variability within observed datasets (Figure 4D). Correspondingly, an increased type-I-error rate was noted (0.201; Table 3).

Discussion

The presented analysis serves to highlight limitations associated with the use of NPC for evaluating Pop-PBPK model concentration predictions. Using simulation-based study designs, where both observed data and simulations were generated under the same model, the analysis demonstrated several examples where use of NPC based on the 90% PI were associated with an increased bias (i.e., inflated type-I-error rates). Theoretically, NPC associated with 90% PI implicitly assumes that each data point has an equal chance (i.e., 10%) of falling outside the interval. As such, the distribution of data falling outside the 90% PI should conform to that of a theoretical binominal distribution. In the presented analyses, agreement with the theoretical binomial distribution only occurred in cases where observed data were uncorrelated, free of residual error, and the distribution of demographics (e.g., body weight) between the observed and virtual subjects was congruent (Figures 2A and 4A). Notably, such conditions lack external validity with regards to real-world PK analyses, where datasets are commonly correlated (i.e., multiple samples per patient) in nature and intrinsically contain residual error.

For observed datasets that contained correlated observations (without residual error), the proportion of datasets where >10% of observations exceeded the model’s 90% PI was ~ 40% (Figure 3A). With application of the exact binomial test, the proportion of data falling outside the model’s 90% PI was deemed to be statistically greater than 0.10 for 12.5% of datasets (Table 3). This means that for approximately 13% of instances, the NPC would erroneously conclude that the model is inadequate (i.e., encounter a type-I error). This result is similar to the findings presented by Brendel et al. (12) who used a simulation-based study design to evaluate the influence of within-subject correlations (i.e., multiple observations per subject) on the type-I-error rate associated with the exact binomial test. Their analysis reported inflated type-I-error rates for NPC based on population PK (PopPK) model-generated 50th, 80th, and 90th percentiles.

Of note, the computation of NPC as described in this work for Pop-PBPK model evaluation differs from NPC used to evaluate PopPK models. The difference is related to how the proportion of observations falling outside model-simulated percentiles are calculated. For Pop-PBPK models, patient-specific observations are compared to simulated percentiles based on virtual populations comprised of subjects whose demographics can differ from that of the sampled patient. For example, members of the virtual population will typically vary (within a user-defined range) in terms of age, height, and weight from that of the observed patient. In contrast, for PopPK models, patient-specific observations are compared to simulated percentiles that are specific to each observation (13). These simulations incorporate covariate information from the patient and stochastic variability (e.g., between subject variability and residual error) to generate simulated PIs. However, despite this computational difference, our results are consistent with the abovementioned PopPK study that demonstrated the detrimental effects of within-subject correlations on NPC performance (12). Furthermore, within their investigation, Brendel et al. proposed the use of a decorrelated NPC, whereby the proportion of observed data corresponding to model PIs was computed following decorrelation of both observed data and PopPK simulations (12). Application of the exact binomial test using decorrelated data was found to attenuate the type-I-error rate to near nominal values. Unfortunately, we were unable to evaluate the impact of a similar decorrelation process for Pop-PBPK modeling, as such methodologies have yet to be developed for this platform.

Residual variability is characteristically endemic to all PK datasets and can arise from multiple sources including process (e.g., misspecifications of dosages and timings) and measurement (e.g., assay) errors (14). However, unlike empiric population PK models, which incorporate residual error using random-effect components (15), PBPK model simulations do not routinely incorporate residual error. As is routine practice, within the current analysis we compared observed datasets with residual error to PBPK model simulations that were devoid of such errors. When observed datasets were correlated and contained a 20% proportional residual error, the analysis found that for approximately 80% of replicates, the proportion of data falling outside the model’s 90% PI exceeded the nominal value (i.e., 0.10; Figure 3B). Considering that both the 90% PI and observed datasets, prior to the inclusion of residual error, were derived from the same model, this finding challenges the validity of NPC for qualifying Pop-PBPK model predictions with respect to ‘realistic’ PK datasets.

Additionally, the current work demonstrates the importance of creating virtual populations that appropriately reflect the distribution of demographics, such as body weight, of observed subjects. For several published PBPK modeling analyses, comparisons between observed data and model predictions is facilitated by employing stochastic algorithms to generate virtual populations that conform to the age or weight range of observed study subjects (16, 17). Although this practice ensures similarity with respect to the span of said demographics between the observed and virtual populations, one cannot infer that the virtual population appropriately recapitulates the underlying demographic distribution among observed subjects. This study demonstrated how such demographic mismatches (e.g., body weight) between observed and virtual populations can influence the conclusions drawn from comparisons between simulations and observed data. For cases where the distribution of body weight among observed subjects was associated with less variability than the virtual population (Figure 4B), the expected number of instances (datasets) where >10% of data points fell outside the 90% PI was suppressed (compared to the binomial distribution). Under such circumstances, the ability to reject models using percentile-based metrics is more prohibitive and may limit the capacity for identifying true model misspecification. In contrast, for observed datasets where the degree of variability associated with subjects’ body weight was greater than that of the virtual population (Figure 4C), use of NPC based on the 90% PI frequently concluded that model predictions were incongruent with observed values. A similar result was depicted when the 90% PI, which was generated based on a virtual population where body weights conformed to a log-normal distribution, was evaluated against observed datasets from subjects whose body weights followed a uniform distribution (Figure 4D).

The presented study is not without limitations. First, presented quantitative results are only applicable towards the proposed theoretical example. However, model parameterization and study design were purposely defined in a ubiquitous manner (e.g., small molecule, lipophilic, low extraction ratio, high protein binding, intravenous administration etc.) as to provide some degree of external relevance towards realistic PK datasets. Second, the analysis solely examined the effects of a 20% residual error component on the performance of NPC. Of note, the performance of NPC appears to be highly sensitive to the magnitude of residual variability. For example, the addition of higher degrees of residual variability onto observed datasets will increase the proportion of observations that exceed the model’s 90% PI; whereas, addition of lower degrees of variability will result in the opposite. Therefore, results pertaining to the effect of residual variability should be discussed in tandem with the examined magnitude (i.e., 20%). Lastly, the simulation-based study assessed the performance of NPC under ideal circumstances, where observed data and simulations were generated under the same model. As such, the analysis does not provide an assessment of the applicability of NPC for evaluating cases where model misspecification is present.

Among published PBPK modeling analyses, the manner in which NPC are used to qualify Pop-PBPK model concentration predictions is not well defined. Use of a clear criterion for model acceptance/rejection has yet to be established. Additionally, computed NPC are typically not assessed for statistical significance (5, 6). As a result, models are deemed successful even when the proportions of data falling outside the model’s 90% PI exceed the nominal value (10%). Considering the presented drawbacks associated with how NPC are implemented for Pop-PBPK model evaluation, their use in this context should be viewed with an appropriate degree of caution. The issues identified by this study do not assert that NPC based on simulated PIs are universally poor metrics for assessing model performance. For example, application of such NPC towards PopPK modeling exercises can provide critical information regarding model agreement/misspecification (18). However, our results indicate that based on current practices, use of NPC to compare model simulations to ‘realistic’ PK datasets, containing correlated observations with residual error, can lead to erroneous conclusions about Pop-PBPK model performance. Although the only evaluation of relevance of PBPK models is against in-vivo datasets, use of in-vivo data in the context of this study would have been infeasible. Considering the need to understand the underlying parameterization of the ‘true’ model and substantial data requirements (e.g., thousands of replicate datasets), a simulated-based study was considered necessary. As the number of drug regulatory submissions containing PBPK modeling analyses increase (19), there is a clear need for metrics capable of discerning between acceptable vs. unacceptable models. The results presented by this research affirm this need for new and more informative metrics for PBPK model qualification.

Conclusion

The presented analysis demonstrates the limitations of using NPC for qualifying Pop-PBPK model concentration-time predictions. NPC based on the 90% PI were associated with inflated type-I-error rates for PK datasets that contained correlated observations (i.e., multiple samples per patient), residual error, or both. Additionally, the performance of NPC was sensitive to the demographic distribution of virtual subjects. Acceptable use of NPC was only demonstrated for the idealistic case where PK data were uncorrelated, free of residual error, and the demographic distribution (e.g., body weight) of virtual subjects matched that of observed subjects. Considering the restricted applicability of NPC for Pop-PBPK model evaluation, their use in this context should be interpreted with caution.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health (1R01-HD076676–01A1; M.C.W.).

Conflicts of interest: A.R.M and H.W. have no conflicts of interest to declare. M.C.W. receives support for research from the NIH (5R01-HD076676), NIH (HHSN275201000003I), NIAID/NIH (HHSN272201500006I), FDA (1U18-FD006298), the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (HHSO1201300009C), and from the industry for the drug development in adults and children (www.dcri.duke.edu/research/coi.jsp). C.P.H. receives salary support for research from National Institute for Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) (K23HD090239), the U.S. government for his work in pediatric and neonatal clinical pharmacology (Government Contract HHSN267200700051C, PI: Benjamin, under the Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act), and industry for drug development in children.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

References

- 1.Maharaj AR, Edginton AN. Physiologically based pharmacokinetic modeling and simulation in pediatric drug development. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol. 2014;3:e150. doi: 10.1038/psp.2014.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Willmann S, Hohn K, Edginton A, Sevestre M, Solodenko J, Weiss W, et al. Development of a physiology-based whole-body population model for assessing the influence of individual variability on the pharmacokinetics of drugs. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn. 2007;34(3):401–31. doi: 10.1007/s10928-007-9053-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sager JE, Yu J, Ragueneau-Majlessi I, Isoherranen N. Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Modeling and Simulation Approaches: A Systematic Review of Published Models, Applications, and Model Verification. Drug Metab Dispos. 2015;43(11):1823–37. doi: 10.1124/dmd.115.065920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Djebli N, Fabre D, Boulenc X, Fabre G, Sultan E, Hurbin F. Physiologically based pharmacokinetic modeling for sequential metabolism: effect of CYP2C19 genetic polymorphism on clopidogrel and clopidogrel active metabolite pharmacokinetics. Drug Metab Dispos. 2015;43(4):510–22. doi: 10.1124/dmd.114.062596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hornik CP, Wu H, Edginton AN, Watt K, Cohen-Wolkowiez M, Gonzalez D. Development of a Pediatric Physiologically-Based Pharmacokinetic Model of Clindamycin Using Opportunistic Pharmacokinetic Data. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2017;56(11):1343–53. doi: 10.1007/s40262-017-0525-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salerno SN, Edginton A, Cohen-Wolkowiez M, Hornik CP, Watt KM, Jamieson BD, et al. Development of an Adult Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Model of Solithromycin in Plasma and Epithelial Lining Fluid. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol. 2017;6(12):814–22. doi: 10.1002/psp4.12252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jiang XL, Zhao P, Barrett JS, Lesko LJ, Schmidt S. Application of physiologically based pharmacokinetic modeling to predict acetaminophen metabolism and pharmacokinetics in children. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol. 2013;2:e80. doi: 10.1038/psp.2013.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rodgers T, Leahy D, Rowland M. Physiologically based pharmacokinetic modeling 1: predicting the tissue distribution of moderate-to-strong bases. J Pharm Sci. 2005;94(6):1259–76. doi: 10.1002/jps.20322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodgers T, Leahy D, Rowland M. Tissue distribution of basic drugs: accounting for enantiomeric, compound and regional differences amongst beta-blocking drugs in rat. J Pharm Sci. 2005;94(6):1237–48. doi: 10.1002/jps.20323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rodgers T, Rowland M. Physiologically based pharmacokinetic modelling 2: predicting the tissue distribution of acids, very weak bases, neutrals and zwitterions. J Pharm Sci. 2006;95(6):1238–57. doi: 10.1002/jps.20502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. PK-Sim® Ontogeny Database (version 7.1) 2017 https://github.com/Open-Systems-Pharmacology/OSPSuite.Documentation/blob/master/PK-Sim%20Ontogeny%20Database%20Version%207.1.pdf.

- 12.Brendel K, Comets E, Laffont C, Mentre F. Evaluation of different tests based on observations for external model evaluation of population analyses. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn. 2010;37(1):49–65. doi: 10.1007/s10928-009-9143-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilkins J, Karlsson M, Jonsson E. Patterns and power for the visual predictive check. PAGE 15 Abstr 1029 [wwwpage-meetingorg/?abstract=1029]. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duffull SB, Wright DF, Winter HR. Interpreting population pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic analyses - a clinical viewpoint. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;71(6):807–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2010.03891.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mould DR, Upton RN. Basic concepts in population modeling, simulation, and model-based drug development-part 2: introduction to pharmacokinetic modeling methods. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol. 2013;2:e38. doi: 10.1038/psp.2013.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang W, Nakano M, Sager J, Ragueneau-Majlessi I, Isoherranen N. Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Model of the CYP2D6 Probe Atomoxetine: Extrapolation to Special Populations and Drug-Drug Interactions. Drug Metab Dispos. 2017;45(11):1156–65. doi: 10.1124/dmd.117.076455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin W, Heimbach T, Jain JP, Awasthi R, Hamed K, Sunkara G, et al. A Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Model to Describe Artemether Pharmacokinetics in Adult and Pediatric Patients. J Pharm Sci. 2016;105(10):3205–13. doi: 10.1016/j.xphs.2016.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nguyen TH, Mouksassi MS, Holford N, Al-Huniti N, Freedman I, Hooker AC, et al. Model Evaluation of Continuous Data Pharmacometric Models: Metrics and Graphics. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol. 2017;6(2):87–109. doi: 10.1002/psp4.12161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao P Application of Physiologically-based Pharmacokinetic Modeling to Support Dosing Recommendations – The US Food and Drug Administration Experience. 2016. EMA Workshop on PBPK Guideline 2016 [cited 2018 07/23]; Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Presentation/2016/12/WC500217569.pdf. [Google Scholar]