Abstract

Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV) is a highly infectious virus infecting pigs with high morbidity, especially for newborn piglets. Several PEDV strains were isolated from the intestinal tracts of diarrheic piglets from the Beijing area, China. Sequencing of the whole-genome of the PEDV isolates (GenBank numbers MG546687-MG546690) yielded sequences of 28033–28038 nt. The phylogenetic tree revealed that these strains from the Beijing area belonged to group II, while the vaccine strain, CV777, belonged to group I. We also determined the genetic correlation between these strains and CV777 strain. However, it showed that these strains in the Beijing area had unique mutations. The sequence identity of PEDV strains showed that these strains are most similar to these strains LZW, CH/JX-1/2013, USAIllinois972013, USAKansas1252014, CH/GDZQ/2014, SHQPYM2013, AJ1102, CHZMDZY11, KoreaK14JB01, and CHYJ130330, respectively. The possible recombination events indicate that PEDV in this studies were possibly recombinant strain formed by parent strains USAIllinois972013, KoreaK14JB01, CHYJ130330, and CHZMDZY11. These PEDV strains has been genetic recombination and mutations. The variant strains characterized in this study help to the evolutionary analysis of PEDV.

Keywords: PEDV, Sequence analysis, Isolation, Phylogenetic tree, Whole-genome

Introduction

Porcine epidemic diarrhea (PED) is a highly infectious disease of swine. It causes severe watery diarrhea, vomiting, dehydration and death in suckling and nursing piglets that are typically 1–2 weeks of age [1, 2]. Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV) is a member of the Coronaviridae family [3, 4]. The virus strain was first isolated in Belgium in 1973 and designated coronavirus CV777 [1]. There were only a few reports in the following decades [5–7]. However, a new PEDV strain has emerged in Asia since 2010 [7–10]. In China, the positive rate of PEDV in some provinces was over 50% in 2010–2011 [7]. In USA, classical PEDV first identified in the state of Ohio in 2013, and a variant PEDV was reported in 2014 [11]. In Japan, more than 490,000 pigs died of PED from 2013 to 2015 [12]. In Korea, PED outbreaks reoccurred in 2013 [13, 14]. In Europe, isolates were reported from the Ukraine, Belgium, Holland, France, Germany, Portugal and Italy from 2013 to 2015 [15]. These isolates were closely related to those strains reported from North America [11, 15].

Diarrhea disease broke out in some large-scale pig farms in the Beijing area of China from 2015 to 2016. The newborn piglets had high mortality rates, resulting in heavy loss to pig farms. The CV777 vaccines used failed. PEDV strains were isolated and identified from the small intestine of diarrhea samples obtained at these pig farms. Whole genome sequencing and recombinant analysis was performed, with the aim of examining the genomes for viral mutations and recombination. The molecular epidemiological information of PEDV can help develop efficient diagnostic reagent and vaccine.

Materials and methods

Virus isolation and identification

Intestine samples of dead piglets with diarrhea were collected from several piglets infected with PEDV from 2015 to 2016. These infected piglets were chosen from 4 different large-scale swine farms located in Beijing and Hebei provinces in China. PEDV detection were positive via RT-PCR. For total RNA extraction, samples were frozen with liquid nitrogen. All procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Beijing University of Agriculture (Beijing, China).

The fresh intestine samples were collected under sterile conditions, made then into slurry, filter sterilization. Vero E6 cells were washed with PBS twice. After adsorption for 60 min at 37 °C, PEDV growth medium was added [16]. The Vero E6 cell cultures were observed for 4 days for cytopathic effects (CPE).

Complete nucleotide sequence of PEDV

Total RNA was obtained from intestine samples using TRIzol (Invitrogen, USA), per the manufacturer’s instructions (Promega, USA), and was used for cDNA synthesis. PCR was performed to amplify the target gene using specific primers (reference sequence number: NC003436.1), as shown in Table 1. PCR reaction contained primers, cDNA, dNTP mix and Hifi polymerase (Transgen, China) in 1× Hifi buffer. PCR products were sequenced from both ends by Sangon Biotech co. ltd. The coding sequences for PEDV were deposited in the GenBank database under accession numbers MG546687-MG546690.

Table 1.

Primers of the PEDV genes

| Genes | Forward primer (5′–3′) | Reverse primer (5′–3′) | Position |

|---|---|---|---|

| PEDVORF1P1 | ATGGCTAGCAACCATGTCACATTGG | TGCATGCTTACCCTTACGTGGACC | 293–4285 |

| PEDV ORF1P2 | GCAAAGGCCATTGATGTTTATACCA | TCGAAGCACAAACCAGATGTACCAA | 4286–8033 |

| PEDV ORF1P3 | TCTTTATTAACTTCGACCAGTGGCA | GAACTTACGTGGTGGTTCTAGCTCA | 8034–11986 |

| PEDV ORF1P4 | ATTTCAGATAAACCGGACCTGCGTG | GCACAAAAACCATGCCAGGAACAAG | 11987–15954 |

| PEDV ORF1P5 | ATCGGTGAGTTTGTGTTTGAGAAGG | GTCAAAGCAGAACCACTTAGCATCC | 15955–18214 |

| PEDV ORF1P6 | ATGTGGTTCGCAAGCGTATAGTTCA | TCATTTGTTTACGTTGACCAAATGATTAGA | 18215–20633 |

| PEDV ORF3 | ATGTTTCTTGGACTTTTTCAATAC | TCATTCACTAATTGTAGCATACTCG | 24794–25448 |

| PEDVE | ATGCTACAATTAGTGAATGATAATGGG | TTATACGTCAATAACAGTACTGGGG | 25449–25686 |

| PEDVM | ATGTCTAACGGTTCTATTCCC | TTAGACTAAATGAAGCACTTTCTC | 25687–26396 |

| PEDVN | ATGGCTTCTGTCAGCTTTCAGGATCG | TTAATTTCCTGTGTCGAAGATCTCGTTGA | 26397–27704 |

| PEDV5UTR | ACTTAAAAAGATTTTCTATCTACGGATA | AGCCGGCAGTTACTGGTTT | 1–292 |

| PEDV3UTR | ACAATGTTAGACCGGCTTATCCT | GTGTATCCATATCAACACCGTCAG | 27705–28038 |

| PEDVS | ATGAAGTCTTTAACCTACTTCTGGTTGTT | TCACTGCACGTGGACCTTTTC | 20634–24793 |

Sequence analysis

Nucleotide and amino acid sequences of PEDV were aligned by the ClustalW method. Sequence alignments of the whole genome and construction of trees were also performed by the neighbor-joining method in MEGA7 software. Information of the other strains that were chosen in this study, including years and locations of isolation and GenBank accession numbers proposed, are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

PEDV strains used in this study

| Strains | Location | Date | Accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|

| CH/BJ9/2015 | Beijing, China | 2015 | MG546687 |

| CH/BJ2/2016 | Beijing, China | 2016 | MG546688 |

| CH/BJ11/2016 | Beijing, China | 2016 | MG546690 |

| CH/HB9/2016 | Hebei, China | 2016 | MG546689 |

| CV777 | Belgium | 1978 | AF353511 |

| CH/GDZQ/2014 | Gangdong, China | 2014 | KM242131 |

| CHZMDZY11 | Henan, China | 2011 | KC196276 |

| CH/JX-1/2013 | Jiangxi, China | 2013 | KF760557 |

| SHQPYM2013 | Shanghai, China | 2013 | KJ196348 |

| CHYJ130330 | Gangdong, China | 2013 | KJ020932 |

| CH/YNKM-8/2013 | Yunnan, China | 2013 | KF761675 |

| CH/FJZZ-9/2012 | Fujian, China | 2012 | KC140102 |

| CH/GDGZ/2012 | Gangdong, China | 2012 | KF384500 |

| AJ1102 | Hubei, China | 2011 | JX188454 |

| LC | Gangdong, China | 2012 | JX489155 |

| KC189944 | Hubei, China | 2013 | KC189944 |

| SD-M | Shandong, China | 2012 | JX560761 |

| ZJCZ4 | Zhejiang, China | 2012 | JX524137 |

| LZW | Beijing, China | 2014 | KJ777678 |

| KoreaK14JB01 | Korea | 2014 | KJ623926 |

| USAIllinois972013 | Illinois, USA | 2013 | KJ645689 |

| USAKansas1252014 | Kansas, USA | 2014 | KJ645701 |

| SeCoV/Italy/213306/2009 | Italy | 2009 | KR061459 |

Recombination analysis

Comparison and analysis of the whole PEDV genome sequences and the reference PEDV strains were conducted using MegAlign programs (DNAStar, Madison, WI).

The putative recombinant sequence of these strains in this study and its parental strains were conducted using recombination detection program (RDP) version 4.97 with seven recombination detection methods (RDP, GENECONV, Chimaera, MaxChi, BootScan, SiScan, and 3Seq). In order to improve the reliability of detection, the recombination breakpoints through at least 5 of these methods was taken as confirmatory for any putative recombination event (p value is 0.01). The phylogenetic tree of recombination and non-recombination were constructed to verify the reliability of these results.

Results

Virus isolation and identification

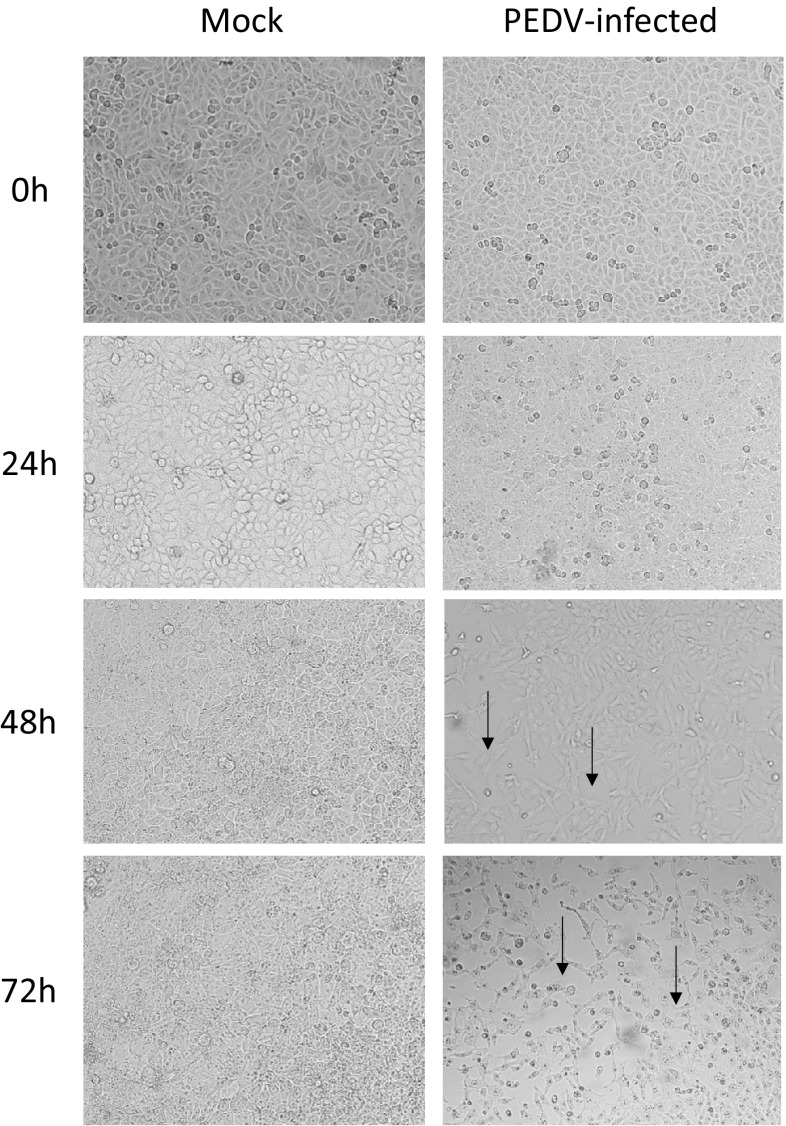

Vero E6 cells were used for viral multiplication. Cytopathic effects (CPE) appeared 48 h after inoculating virus, and more than 70% CPE with cell clustering, detachment, and syncytium formation were observed at 72 h. These results indicated that the isolated PEDV could cause pathological changes in Vero E6 cells (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Pathogenicity experiment of PEDV-infected Vero cells in different periods. Cytopathic effects appeared 48 h after the initial infection, and more than 50% cytopathic effects were observed at 72 h. No cytopathic effects occurred in the control wells

Sequence analysis of the whole genome

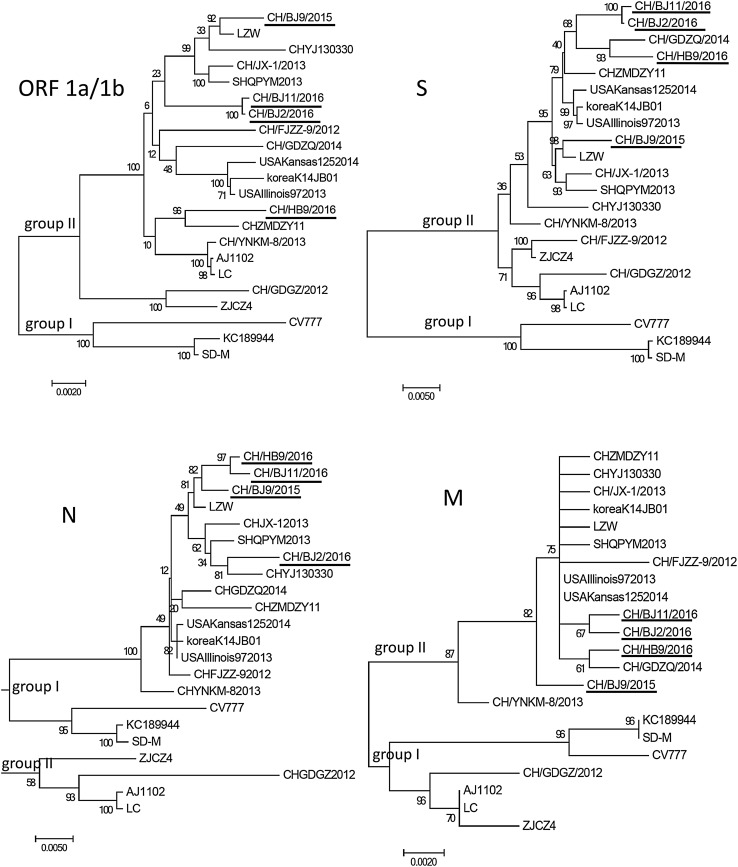

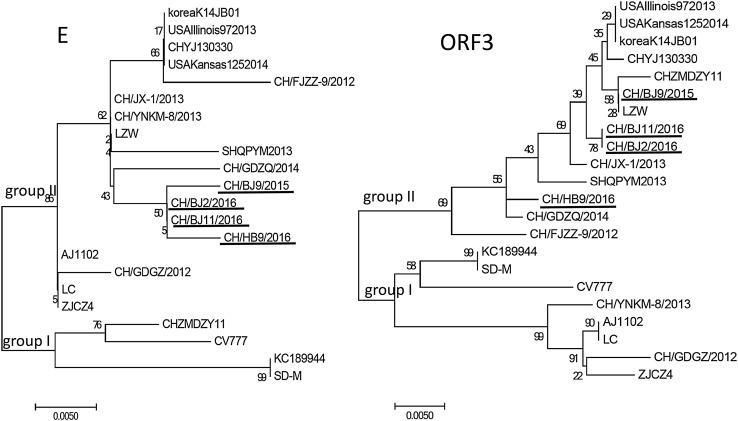

The organization of the genome of PEDV was characteristic of the gene order 5′-ORF1a/1b-S-ORF3-E-M-N-3′ [2, 4, 17, 18]. Sequencing of the complete gene of the four isolates (GenBank numbers: MG546687-MG546690) yielded sequences of 28033–28038 bp, which compared with 18 typical strains available in GenBank (Table 2). The phylogenetic tree showed that these 22 PEDV strains divided into two groups (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of the PEDV nucleotide sequences of 22 PEDV isolates, including the reference strains. The trees were constructed by the neighbor-joining method in MEGA7 software. Bootstrap values were indicated for each node from 1000 replicates. The names of the strains, years and places of isolation, as well as GenBank accession numbers proposed, are shown in Table 2. The strains in this study are indicated by underline

Recombination analysis of PEDV

The sequence identity between PEDV strains in this studies and typical strains in terms of their according genes or regions were calculated. The highest percentage of nucleotide identities of 5′-UTR, ORF1a/1b, S, M, N, E, ORF3, and 3′-UTR of PEDV compared with other PEDV strains were show in Table 3. For ORF1a/1b gene, these strains are most similar to these strains, LZW, SHQPYM2013, AJ1102, CH/YNKM-8/2013, CH/JX-1/2013, USAKansas1252014, and CHZMDZY11, respectively. For S gene, these strains are most similar to these strains LZW, KoreaK14JB01, USAIllinois972013, USAKansas1252014, and CH/GDZQ/2014, respectively. The percentage of nucleotide identities of S of PEDV strains in this study compared with recombined strains SeCoV is 90.4–90.7%. For M gene, these strains are most similar to these strains USAIllinois972013 and USAKansas1252014. For N gene, these strains are most similar to these strains LZW and CHYJ130330. For E gene, these strains are most similar to these strains LZW, CH/JX-1/2013, and CH/YNKM-8/2013. For ORF3 gene, these strains are most similar to these strains LZW, CH/JX-1/2013, USAIllinois972013, USAKansas1252014, and CH/GDZQ/2014, respectively (Table 3).

Table 3.

Percentage of sequence identities of the complete genome and different regions of PEDV strains compared with those of other PEDV strains

| Strain | 5′-UTR | ORF1a/1b | S | M | N | E | ORF3 | 3′-UTR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CH/BJ9/2015 | ||||||||

| Strain | CH/JX-1/2013 | LZW | LZW | USAIllinois972013, USAKansas1252014 | LZW | CH/JX-1/2013, CH/YNKM-8/2013, LZW | LZW | CH/JX-1/2013, CHYJ130330 |

| Percenta | 99.3 | 99.7 | 99.2 | 99.7 | 99.4 | 99.1 | 100 | 99.4 |

| CH/BJ2/2016 | ||||||||

| Strain | AJ1102, CH/YNKM-8/2013, LC | SHQPYM2013 | KoreaK14JB01, USAIllinois972013, USAKansas1252014 | USAIllinois972013, USAKansas1252014 | CHYJ130330 | CH/JX-1/2013, CH/YNKM-8/2013, LZW | CH/JX-1/2013, USAIllinois972013, USAKansas1252014 | CH/JX-1/2013, CHYJ130330 |

| Percenta | 98.6 | 99.2 | 98.9 | 99.7 | 98.9 | 99.6 | 99.7 | 99.4 |

| CH/BJ11/2016 | ||||||||

| Strain | AJ1102, CH/YNKM-8/2013, LC | AJ1102, CH/YNKM-8/2013, CH/JX-1/2013, LZW, SHQPYM2013, USAKansas1252014 | KoreaK14JB01, USAIllinois972013, USAKansas1252014 | USAIllinois972013, USAKansas1252014 | LZW | CH/JX-1/2013, CH/YNKM-8/2013, LZW | CH/JX-1/2013, USAIllinois972013, USAKansas1252014 | CH/JX-1/2013, CHYJ130330 |

| Percenta | 98.6 | 99.1 | 98.8 | 99.7 | 99.2 | 99.6 | 99.7 | 99.4 |

| CH/HB9/2016 | ||||||||

| Strain | ZJCZ | CHZMDZY11 | CH/GDZQ/2014 | USAIllinois972013, USAKansas1252014 | LZW | CH/JX-1/2013, CH/YNKM-8/2013, LZW | CH/GDZQ/2014 | CH/JX-1/2013, CHYJ130330 |

| Percenta | 99.7 | 99.2 | 98.9 | 99.7 | 99.2 | 99.1 | 99.6 | 99.4 |

aThe highest nucleotide precent identities of different regions

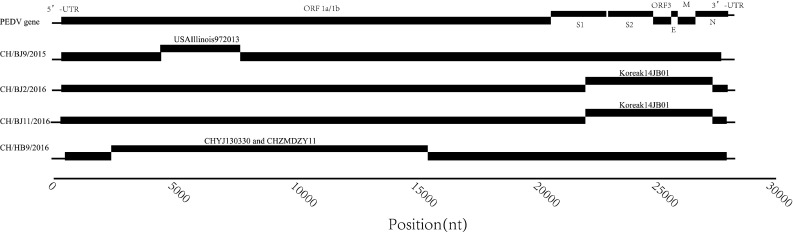

Frequent mutation and recombination of genes may occur in epidemics of PEDV. In order to detect these possible recombination events, 19 reference strains were used as parent strains for RDP, GENECONV, Chimaera, MaxChi, BootScan, SiScan, and 3Seq program analysis. The results showed that PEDV in this study were possibly recombinant strain formed by parent strains USAIllinois972013, KoreaK14JB01, CHYJ130330 and CHZMDZY11 (Fig. 3). USAIllinois972013 is major parent of PEDV strain CH/BJ9/2015, the recombination region locates on 4669-8176nt; KoreaK14JB01 is minor parent of PEDV strains CH/BJ2/2016 and CH/BJ11/2016, the recombination region locates on 21744-27721nt; CHYJ130330 is major parent of PEDV strain CH/HB9/2016 and CHZMDZY11 is minor parent of CH/HB9/2016, their recombination region locates on 2218-15942nt. However, there may be a deviation in the prediction of software. It requires further confirms these recombination events.

Fig. 3.

Results of the recombination analysis of PEDV strains. The putative recombinant sequence of PEDV strains and its parent strains were conducted using recombination detection program version 4.97 (RDP) with seven recombination detection methods (RDP, GENECONV, Chimaera, MaxChi, BootScan, SiScan, and 3Seq, p value is 0.01)

Discussion

Since 2011, a large number of piglets died as a result of PEDV outbreaks, causing much economic loss in China [2–4, 7–10, 18–21]. In this study, the deceased piglets that provided intestine samples had been immunized with the CV777 vaccine previously. This showed that the classic vaccine strain exhibited lower protective efficacy against the variant PEDV [22, 23]. The phylogenetic trees showed that, these PEDV isolates from the Beijing area belonged to group II, while the traditional vaccine strain, CV777, belonged to group I based on the comparison of several important genes in PEDV, such as ORF1a/1b, S, M, N, E, and ORF3. However, N, as a conserved gene, was inconsistent with the above results, which also suggested that the N sequence or protein is suitable for universal detection. The ORF1a/1b gene were two long ORFs which encoding the non-structural replicase polyproteins of PEDV. The strain from 2015 in the Beijing area shared the greatest homology in ORF1a/1b with LZW, which was also isolated in Beijing; it showed the continuity of heredity.

The S sequence of isolates in 2015 in the Beijing area showed a closer relationship with a previous isolate, LZW. Other isolates in 2016 in the Beijing area showed a closer relationship with previous isolates in Guangdong. This revealed that S genes accumulated variations faster based on inherent genetic characteristics or recombinant genes from other isolates [10, 20, 24].

The 1–1180 bp section in the S1 region of PEDV genes is prone to mutate [24]. Sequence analysis revealed that isolated PEDV strains and these variant PEDV strains were reported had insertion in 167–178 sites (GTGAAAACCAGG) and 421–423 sites (TGA), also deletion in 218 (A), 471–474 (ATAT) and 481–482 (TG) comparing with CV777. These insertion, deletion, or introducing stop codon (TGA) of sequence resulted in frameshift mutation and abnormally transcripts of S1 gene. It is a reason for failed vaccination with CV777 vaccine. However, different from other recent isolates, these strains in the Beijing area had shared sites with CV777 in the S1 region, such as A5G (this specific nucleotide change led to the amino acid change K–R), C70T, and T1043C (which led to the amino acid change F–S). This determined the genetic correlation between these strains in the Beijing area and the CV777 strain. It was remarkable that E sequences of isolates in the Beijing area had distinct differences from other isolates. There were unique variations in the E gene in these strains, such as T27G. This showed that these isolates from the Beijing area had unique mutations. This might provide a gene reference for other mutations of PEDV in the future.

Viral gene recombination and mutation results in evolution [25]. Gene recombination and mutation often occurs in coronavirus, such as PEDV, SARSCoV, and infectious bronchitis virus (IBV) [26–29]. There is evidence that the S gene of epidemic PEDV strains and genome of transmissible gastroenteritis virus (TEGV) strains have recombined when both were present in the same host to form a new recombinant porcine coronavirus, SeCoV [30, 31]. This S sequence of SeCoV strain share above 90% homology with S sequence of PEDV strains in this study. However, analysis of the recombination of PEDV strains showed that, no recombination event was occurred between SeCoV strain and PEDV strains in this study. These PEDV strains isolated in Beijing area shows recombination events with PEDV isolated in USA, PEDV isolated in Korea, and PEDV isolated in China in sequence. It suggests the accelerated spread of PEDV virus.

Viral recombination and mutation causes immune failure. The new and effective vaccine is critical to control the occurrence of PEDV. The study of the effective vaccine must be based on the characteristic analysis of variant viruses [32]. The new data on the evolutionary analysis of PEDV is provided in this study. These data will be helpful for research on PEDV vaccine and control.

Several PEDV strains were isolated from the intestinal tracts of diarrheic piglets from the Beijing area, China. These PEDV strains has been genetic recombination and mutations. The variant strains characterized in this study help to the evolutionary analysis of PEDV.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the pig farm owners their collaboration.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31572499). The funders did not play any role in the design, conclusions or interpretation of the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Experimental animals used in the study were cared for in accordance with the internationally accepted standards for the care and handling of laboratory animals. All procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Beijing University of Agriculture (Beijing, China). The Animal Ethics Committee approval number was BUAACUC2016-1. All samples were collected after informed written consent was obtained from the owners.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Pensaert MB, Bouck PD. A new coronavirus-like particle associated with diarrhea in swine. Adv Virol. 1978;58(3):243–247. doi: 10.1007/BF01317606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li ZL, et al. Molecular characterization and phylogenetic analysis of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV) field strains in south China. Virus Genes. 2012;45(1):181. doi: 10.1007/s11262-012-0735-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li Z, et al. Sequence and phylogenetic analysis of nucleocapsid genes of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV) strains in China. Adv Virol. 2013;158(6):1267. doi: 10.1007/s00705-012-1592-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang DQ, et al. Whole-genome analysis of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV) from eastern China. Adv Virol. 2014;159(10):2777. doi: 10.1007/s00705-014-2102-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takahashi K, Okada K, Ohshima K. An outbreak of swine diarrhea of a new-type associated with coronavirus-like particles in Japan. Nihon Juigaku Zasshi. 1983;45(6):829–832. doi: 10.1292/jvms1939.45.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Song D, Park B. Porcine epidemic diarrhoea virus: a comprehensive review of molecular epidemiology, diagnosis, and vaccines. Virus Genes. 2012;44(2):167–175. doi: 10.1007/s11262-012-0713-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang D, Fang L, Xiao S. Porcine epidemic diarrhea in China. Virus Res. 2016;226:7. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2016.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pan Y, et al. Isolation and characterization of a variant porcine epidemic diarrhea virus in China. Virology Journal. 2012;9(1):195. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-9-195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun R, et al. Genetic variability and phylogeny of current chinese porcine epidemic diarrhea virus strains based on spike, ORF3, and membrane genes. Sci World J. 2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/208439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hao J, et al. Bioinformatics insight into the spike glycoprotein gene of field porcine epidemic diarrhea strains during 2011–2013 in Guangdong, China. Virus Genes. 2014;49(1):58. doi: 10.1007/s11262-014-1055-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang L, Byrum B, Zhang Y. New variant of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus, United States, 2014. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20(5):917–919. doi: 10.3201/eid2005.140195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horie M, et al. Isolation and molecular characterization of porcine epidemic diarrhea viruses collected in Japan in 2014. Adv Virol. 2016;161(8):2189–2195. doi: 10.1007/s00705-016-2900-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chung HC, et al. New emergence pattern with variant porcine epidemic diarrhea viruses, South Korea, 2012–2015. Virus Res. 2016;226:14–19. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2016.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee S, Lee C. Outbreak-related porcine epidemic diarrhea virus strains similar to US strains, South Korea, 2013. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20(7):1223. doi: 10.3201/eid2007.140294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pensaert MB, Martelli P. Porcine epidemic diarrhea: a retrospect from Europe and matters of debate. Virus Res. 2016;226:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2016.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oka T, et al. Cell culture isolation and sequence analysis of genetically diverse US porcine epidemic diarrhea virus strains including a novel strain with a large deletion in the spike gene. Vet Microbiol. 2014;173(3–4):258–269. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2014.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sj P, et al. Molecular characterization and phylogenetic analysis of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV) field isolates in Korea. Adv Virol. 2011;156(4):577. doi: 10.1007/s00705-010-0892-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang H, et al. Isolation, molecular characterization and an artificial infection model for a variant porcine epidemic diarrhea virus strain from Jiangsu Province, China. Adv Virol. 2017;1:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s00705-017-3518-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sung MH, et al. Evolutionary characterization of the emerging porcine epidemic diarrhea virus worldwide and 2014 epidemic in Taiwan. Infect Genet Evol. 2015;36:108–115. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2015.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Su Y, et al. Detection and phylogenetic analysis of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus in central China based on the ORF3 gene and the S1 gene. Virol J. 2016;13(1):192. doi: 10.1186/s12985-016-0646-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fan B, et al. Characterization of Chinese porcine epidemic diarrhea virus with novel insertions and deletions in genome. Sci Rep. 2017;7:44209. doi: 10.1038/srep44209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Song D, Moon H, Kang B. Porcine epidemic diarrhea: a review of current epidemiology and available vaccines. Clin Exp Vaccine Res. 2015;4(2):166–176. doi: 10.7774/cevr.2015.4.2.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Annamalai T, et al. Cross protective immune responses in nursing piglets infected with a US spike-insertion deletion porcine epidemic diarrhea virus strain and challenged with an original US PEDV strain. Vet Res. 2017;48(1):61. doi: 10.1186/s13567-017-0469-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Niraj M, et al. S1 domain of the porcine epidemic diarrhea virus spike protein as a vaccine antigen. Virol J. 2016;13(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12985-015-0456-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Su S, et al. Epidemiology, genetic recombination, and pathogenesis of coronaviruses. Trends Microbiol. 2016;24(6):490–502. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2016.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thor SW, et al. Recombination in avian gamma-coronavirus infectious bronchitis virus. Viruses. 2011;3(9):1777–1799. doi: 10.3390/v3091777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao Y, et al. Evolution of infectious bronchitis virus in China over the past two decades. J Gen Virol. 2016;97(7):1566–1574. doi: 10.1099/jgv.0.000464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hu J, et al. Evolution and variation of the SARS-CoV genome. Genom Proteom Bioinform. 2003;1(3):216–225. doi: 10.1016/S1672-0229(03)01027-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holmes EC, Rambaut A. Viral evolution and the emergence of SARS coronavirus. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2004;359(1447):1059–1065. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boniotti MB, et al. Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus and discovery of a recombinant swine enteric coronavirus, Italy. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22(1):83–87. doi: 10.3201/eid2201.150544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Belsham GJ, et al. Characterization of a novel chimeric swine enteric coronavirus from diseased pigs in central eastern Europe in 2016. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2016;63(6):595–601. doi: 10.1111/tbed.12579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Graham RL, et al. Evaluation of a recombination-resistant coronavirus as a broadly applicable, rapidly implementable vaccine platform. Commun Biol. 2018;1:179. doi: 10.1038/s42003-018-0175-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]