The regulation of heat shock proteins which protect M. tuberculosis against stress generated by macrophages during infection is poorly understood. In this study, we show that PhoP, a virulence regulator of the tubercle bacilli, controls heat shock-responsive genes, an essential pathogenic determinant of M. tuberculosis. Our results unravel that in addition to classical DNA-protein interactions, complex mechanisms of regulation of heat shock-responsive genes occur through multiple protein-protein interactions. Together, these findings delineate a fundamental regulatory pathway where transcription factors PhoP, HspR, and HrcA interact with each other to control stress-specific expression of heat shock proteins.

KEYWORDS: global regulation, heat shock repressors, heat shock response, M. tuberculosis PhoP, protein-protein interactions

ABSTRACT

A hallmark feature of Mycobacterium tuberculosis pathogenesis lies in the ability of the pathogen to survive within macrophages under a stressful environment. Thus, coordinated regulation of stress proteins is critically important for an effective adaptive response of M. tuberculosis, the failure of which results in elevated immune recognition of the tubercle bacilli with reduced survival during chronic infections. Here, we show that virulence regulator PhoP impacts the global regulation of heat shock proteins, which protect M. tuberculosis against stress generated by macrophages during infection. Our results identify that in addition to classical DNA-protein interactions, newly discovered protein-protein interactions control complex mechanisms of expression of heat shock proteins, an essential pathogenic determinant of M. tuberculosis. While the C-terminal domain of PhoP binds to its target promoters, the N-terminal domain of the regulator interacts with the C-terminal end of the heat shock repressors. Remarkably, our findings delineate a regulatory pathway which involves three major transcription factors, PhoP, HspR, and HrcA, that control in vivo recruitment of the regulators within the target genes and regulate stress-specific expression of heat shock proteins via protein-protein interactions. The results have implications on the mechanism of regulation of PhoP-dependent stress response in M. tuberculosis.

IMPORTANCE The regulation of heat shock proteins which protect M. tuberculosis against stress generated by macrophages during infection is poorly understood. In this study, we show that PhoP, a virulence regulator of the tubercle bacilli, controls heat shock-responsive genes, an essential pathogenic determinant of M. tuberculosis. Our results unravel that in addition to classical DNA-protein interactions, complex mechanisms of regulation of heat shock-responsive genes occur through multiple protein-protein interactions. Together, these findings delineate a fundamental regulatory pathway where transcription factors PhoP, HspR, and HrcA interact with each other to control stress-specific expression of heat shock proteins.

INTRODUCTION

A hallmark feature of tuberculosis (TB) pathogenesis lies in the ability of the pathogen to survive within macrophages under a stressful environment. One of the pathways by which Mycobacterium tuberculosis survives exposure to unfavorable conditions encountered within the host involves the induction of a strong stress protein response following phagocytosis (1, 2). During infection, heat shock proteins, as a member of the major stress protein families, are induced in both the host and the pathogen to maintain cellular integrity and to contribute to immune signaling for recognition of the pathogen (3). In fact, elevated expression of heat shock proteins is necessary for bacterial adaptation to inhospitable conditions during intracellular growth and for survival of the bacilli. Thus, the pathogenesis of M. tuberculosis is significantly influenced by the regulatory expression of heat shock proteins. However, our knowledge of the underlying regulatory mechanism which couples heat shock conditions with global gene expression in M. tuberculosis remains superficial.

Although the pathogen does not encounter significantly increased temperature following the uptake of M. tuberculosis by host cells, heat shock proteins are induced possibly because bacterial adaptation to an inhospitable phagosome (during intracellular survival and growth) requires their elevated expression (4). In keeping with this, (i) heat shock proteins function to protect M. tuberculosis against stress generated by host macrophages during infection (5, 6) and (ii) partial disruption of heat shock regulation of M. tuberculosis strongly impacts virulence mechanisms, disabling the bacterium’s ability to establish a chronic infection (4). Remarkably, DNA microarray experiments demonstrate that acr2 (Rv0251c), which is a member of the α-crystallin family of molecular chaperone genes and which shows the highest activation during heat shock (4), is also the most upregulated gene following phagocytosis of M. tuberculosis by macrophages (2). Importantly, acr2 expression remains essential for virulence in a murine model of tuberculosis (7). Thus, it is of interest to understand the molecular mechanism of regulation of heat shock-inducible gene expression of M. tuberculosis.

Although alternative sigma factors have been implicated in activation of hsp70 expression (8), the major control of heat shock protein-encoding genes such as hsp70-dnaK is attributable to the release of transcriptional repression in a stress-specific manner (6). While canonical annotation of the M. tuberculosis genome shows the presence of two heat shock repressors, HspR and HrcA, deletion of hspR was of very little consequence on expression of groE-hsp60 proteins (6). These results suggest that a second repressor hrcA locus in the genome plays an important role in the M. tuberculosis heat shock response. To investigate this, Stewart and coworkers compared whole-genome expression profiles of a ΔhspR strain and the double mutant ΔhrcA ΔhspR strain (4). Their results suggest that transcription control of a large number of heat shock-responsive genes is likely regulated by the hrcA locus as the major regulator. However, to date, the mechanism for regulating the heat shock-inducible genes of M. tuberculosis remains unknown.

Consistent with an overwhelming regulatory control by PhoP of approximately 2% of the genome, including the ESX-1 secretion apparatus (a major pathogenic determinant [9, 28]), mutations in phoP account for in vivo as well as ex vivo attenuation (9, 10). Previously, we showed that expression of acr2, a gene encoding a member of the widespread heat shock-inducible α-crystallin family of molecular chaperones which stabilize proteins during stress conditions, is dependent on the phoP locus (11). In this study, we wanted to investigate the impact of phoP on the M. tuberculosis transcriptome under heat shock conditions. Our microarray data implicate expression of numerous heat shock-responsive genes, including the essential chaperonin gene groEL2, by the phoP locus. Further probing highlighted the critical importance of protein-protein interactions involving PhoP as the nodal regulator and its mechanism of controlling stress-specific regulation of heat shock-responsive gene expression. Taking these findings together, we identify the most important regulatory circuits, showing interactions of PhoP with two heat shock repressors (HspR and HrcA) and how they coordinate mechanisms to transcriptionally control heat shock-responsive genes. Most importantly, consistent with the major regulatory involvement of PhoP as the nodal regulator, a ΔphoP variant displayed significantly higher heat shock-dependent cell death than wild-type (WT) bacilli.

RESULTS

phoP plays a global role in heat shock response of M. tuberculosis.

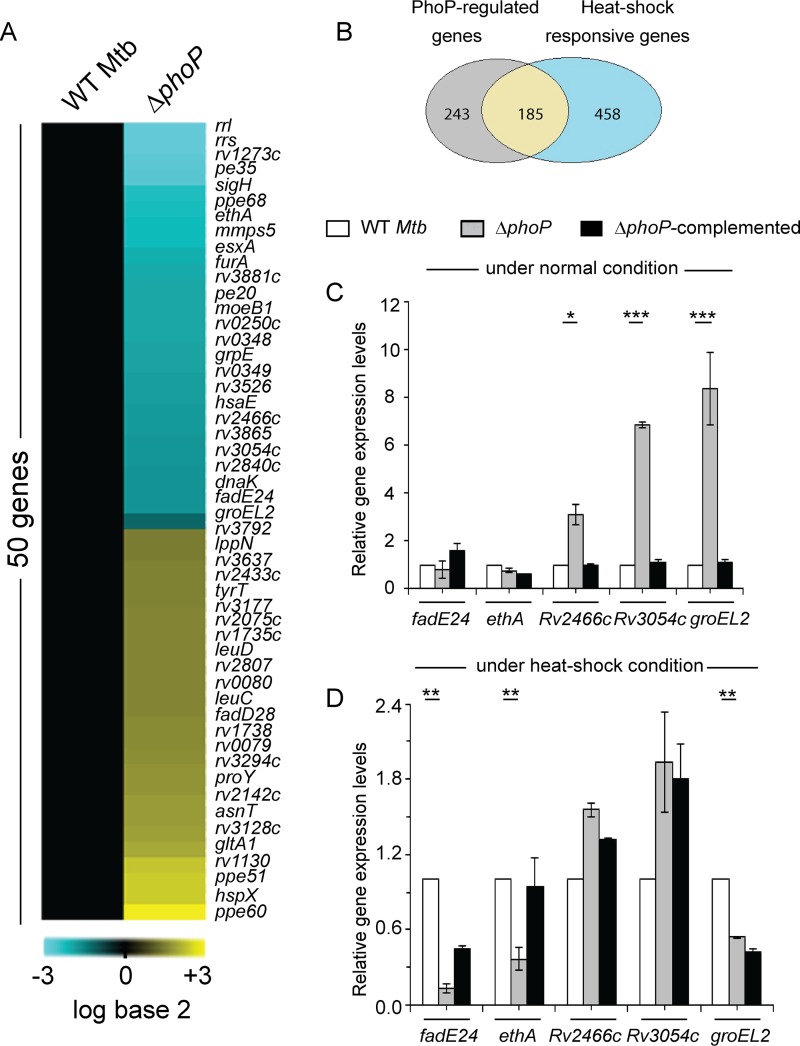

To examine whether phoP plays a global role in controlling heat shock response of M. tuberculosis, we performed microarray experiments using WT H37Rv and ΔphoP strains under both normal and heat shock conditions. Notably, the ΔphoP strain showed differential expression of a large fraction of the heat shock-responsive genes (Fig. 1A). Our results show that out of ∼643 heat shock-responsive genes, approximately 185 are regulated by the phoP locus (Fig. 1B). Functional classification of these genes demonstrates a major impact of the phoP locus on diverse physiological functions, with the most-affected genes being for intermediary metabolism and respiration (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

FIG 1.

phoP locus is required for expression of heat shock-responsive genes of M. tuberculosis. (A) Heat shock-dependent levels of gene expression of WT and ΔphoP strains were compared by microarray experiments showing 50 significantly regulated genes from the cells grown with a heat shock at 45°C for 1 h 30 min. Cyan and yellow signify elevated or lowered gene expression, respectively, relative to WT M. tuberculosis grown under normal conditions (37°C). (B) Overlap of heat shock-responsive genes which displayed a ≥2-fold change in their expression in WT M. tuberculosis as a function of heat stress with genes which demonstrated ≥2-fold phoP-dependent differences of expression. Of the 643 heat shock-responsive genes, 185 were differentially regulated in the ΔphoP mutant. (C and D) Expression of heat shock-responsive genes in WT, ΔphoP, and ΔphoP complemented M. tuberculosis H37Rv grown with or without heat shock was examined by RT-qPCR as described in Materials and Methods. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. The average fold differences in expression levels with standard deviations from replicates were determined for at least three independent RNA preparations. The data reported in this study have been deposited in the NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus (38) and are accessible through GEO series accession number GSE100596.

To validate the microarray data, we next performed reverse transcriptase quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) of a few representative M. tuberculosis genes (see Fig. S2). Table S1 lists the page-purified oligonucleotide primers used in the RT-qPCR experiments. In agreement with the microarray data, we observed significantly higher expression of three heat shock-inducible genes (Rv2466, Rv3054, and groEL2) in the ΔphoP strain relative to that in WT bacteria under normal conditions (Fig. 1C). We next compared the expression of these genes relative to that in WT bacteria during heat stress (Fig. 1D). Strikingly, we found significantly lower expression of fadE24, ethA, and groEL2 in the ΔphoP mutant than in WT M. tuberculosis. These results suggest that phoP plays a major role in heat shock-dependent activation of gene expression. Together, consistent with the microarray data, the RT-qPCR experiments reveal that a large number of heat shock-responsive genes are regulated by the phoP locus.

Repression of heat shock-inducible genes.

Next, we utilized “mycobacterial recombineering” (12) to construct ΔhrcA and ΔhspR strains (see Fig. S3A and B) to probe the mechanism of regulation. The mutants were verified by gene-specific PCR using corresponding genomic DNA as PCR templates (Fig. S3C and D, respectively; Table S2 lists relevant oligonucleotide primers used in cloning, and Table 1 shows the plasmid constructs used in this study). The genomic DNA of the ΔhrcA strain showed the unique presence of a 1.3-kb hyg cassette, while the hrcA gene product was absent (Fig. S3C, compare lane 3 and lane 2). In contrast, the complemented mutant, which utilized the integrative pSTKi (13) harboring a copy of the hrcA gene, showed the presence of both the gene-specific product and the hyg cassette (lane 4). Likewise, hspR-specific amplification from the genomic DNA of the ΔhspR strain yielded similar results (Fig. S3D). Furthermore, we verified the mutant constructs by Southern blot analyses (Fig. S3E). In the Southern blot analysis, WT M. tuberculosis showed two specific bands of approximately 10 and 8.3 kb when probed with hrcA- and hspR-specific probes, respectively. Hybridization of ΔhrcA genomic DNA using identical probes detected an hspR-specific band (∼8.3 kb) only. In contrast, only the hrcA-specific product (∼10 kb) was detectable in the ΔhspR mutant-derived genomic DNA. Our additional RT-qPCR experiments showed that while mRNA levels of hrcA and hspR remained undetectable in the corresponding mutants (Fig. S3E and F), their expressions in the correspondingly complemented strains were largely restored to the WT level. Table S3 lists the strains used in this study.

TABLE 1.

Plasmids used in cloning reported in this study

| Plasmid | Characteristic(s) | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| pET15b | E. coli cloning vector, Ampra | Novagen |

| pET-hspR | HspR residues 1–126 cloned in pET15b | This study |

| pET-hrcA | HrcA residues 1–343 cloned in pET15b | This study |

| pET15b-hspRΔ10 | HspR residues 1–116 cloned in pET15b | This study |

| pET15b-hrcAΔ18 | HrcA residues 1–325 cloned in pET15b | This study |

| pGEX-4T-1 | E. coli cloning vector, Ampr | GE Healthcare |

| pGEX-hrcA | HrcA residues 1–343 cloned in pGEXT-4T-1 | This study |

| pGEX-hspR | HspR residues 1–126 cloned in pGEXT-4T-1 | 11 |

| pGEX-phoP | PhoP residues 1–247 cloned in pGEX-4T-1 | 32 |

| p19Kpro | Mycobacterial expression vector, Hygrb | 14 |

| p19Kpro-phoP | PhoP residues 1–247 cloned in p19Kpro | 15 |

| p19Kpro-hrcA | HrcA residues 1–343 cloned in p19Kpro | This study |

| pSTKi | Integrative mycobacterial expression vector, Kanrc | 13 |

| pSTKi-hrcA | HrcA residues 1–343 cloned in pSTKi | This study |

| pSTKi-hspR | HspR residues 1–126 cloned in pSTKi | This study |

| pSTKi-hrcAΔ18 | HrcA residues 1–325 cloned in pSTKi | This study |

| pSTKi-hspRΔ10 | HspR residues 1–116 cloned in pSTKi | This study |

| pUAB300b | Episomal mycobacteria-E. coli shuttle plasmid | 16 |

| pUAB300-hrcA | HrcA residues 1–343 cloned in pUAB300 | This study |

| pUAB300-hspRΔ10 | HspR residues 1–116 cloned in pUAB300 | This study |

| pUAB300-hrcAΔ18 | HrcA residues 1–325 cloned in pUAB300 | This study |

| pUAB400c | Integrative mycobacterium-E. coli shuttle plasmid | 16 |

| pUAB400-phoP | PhoP residues 1–247 cloned in pUAB400 | 11 |

| pUAB400-phoPN | PhoP residues 1–141 cloned in pUAB400 | This study |

| pUAB400-phoPC | PhoP residues 141–247 cloned in pUAB400 | This study |

Ampr, ampicillin resistant.

Hygr, hygromycin resistant.

Kanr, kanamycin resistant.

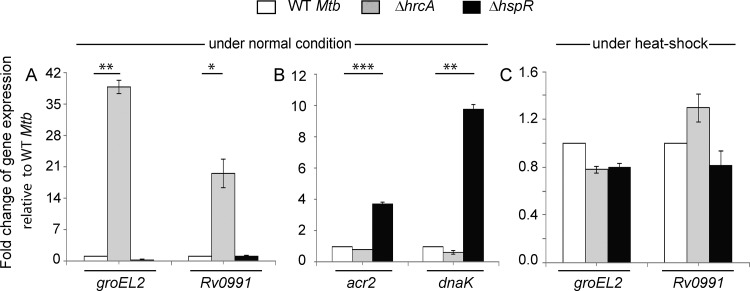

Previous studies by Stewart and coworkers showed that while HrcA functions as a regulator of groEL2 and Rv0991, HspR controls expression of acr2 and dnaK expression in M. tuberculosis (4). In agreement with these results, we observed a significant activation of groEL2 and Rv0991 expression in the ΔhrcA strain under normal conditions (Fig. 2A); however, the WT and ΔhspR strains showed comparable groEL2 expression. Further corroborating our previous results (11), we observed a strong upregulation of acr2 and dnaK expression in the ΔhspR strain but not in the WT and the ΔhrcA mutant (Fig. 2B). Thus, genes which were not repressed in the ΔhrcA mutant showed WT-like repression in the ΔhspR mutant, and genes which were not repressed in the ΔhspR mutant showed WT-like repression in the ΔhrcA mutant. These results confirm that (i) the two genome-encoded heat shock repressors function independently of their respective regulons and (ii) the genes belonging to either HspR or HrcA regulon are targets of PhoP. In line with the general mechanism of repressor function, under heat shock conditions, both the WT and the mutants showed comparable levels of expression of heat shock-inducible genes (Fig. 2C).

FIG 2.

Both HrcA and HspR function as major heat shock repressors. mRNA levels of indicated genes were determined by RT-qPCR in WT and mutant bacteria under normal (A and B) and heat shock (C) conditions of growth, as described in the legend for Fig. 1C and D. The results unambiguously demonstrate specific regulatory effects of the repressors; panel C shows comparable levels of expression of heat shock-inducible genes under heat stress. In all cases, the average fold differences in expression levels with standard deviations from replicate experiments were determined from at least three independent RNA preparations.*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

In vivo recruitment of regulators.

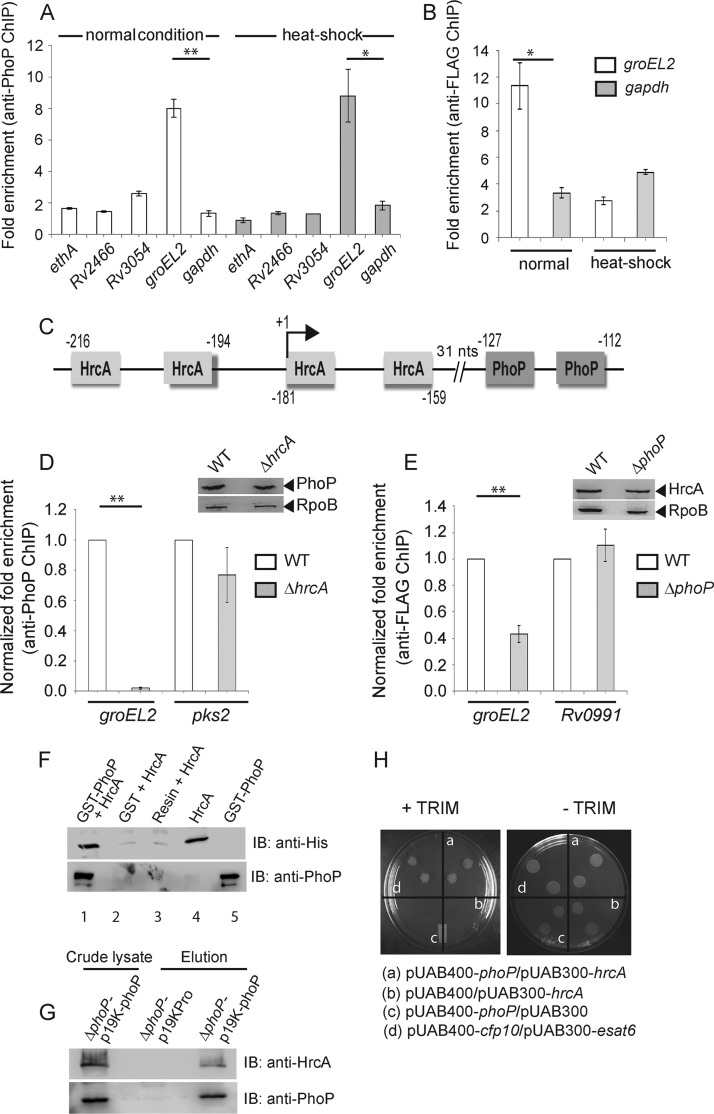

Although by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)-qPCR we were unable to observe significant recruitment of PhoP within a majority of its target promoters, our results showed effective PhoP recruitment within the groEL2 promoter, under both normal and heat shock conditions (Fig. 3A). These results are consistent with the presence of a likely PhoP binding motif (−127 to −112, relative to the translational start site) within the groEL2 regulatory region. While we presume an indirect role of the phoP locus for other heat shock-responsive genes, in vivo binding results are in agreement with regulation data under both normal and stress conditions (Fig. 1). Next, to determine HrcA recruitment, the repressor was expressed as a FLAG-tagged protein, and ChIP experiments were carried out using an anti-FLAG antibody (Thermo) (as described in Materials and Methods). As expected, we found considerable recruitment of HrcA within the groEL2 promoter of WT M. tuberculosis (Fig. 3B). However, HrcA recruitment was insignificant under heat shock conditions, suggesting derepression of promoter activity during stress (Fig. 2C). Figure 3C shows a schematic presentation of the groEL2 regulatory region comprising newly identified PhoP and previously reported HrcA binding sites (4). Note that our attempt to examine the formation of a ternary (PhoP-groEL2up-HrcA) complex was unsuccessful, since PhoP and/or HrcA was ineffective in forming a complex stable for gel electrophoresis.

FIG 3.

In vivo recruitment of regulators. (A) Recruitment of PhoP within heat shock-responsive genes, under both normal and heat shock conditions, was investigated by ChIP-qPCR using anti-PhoP antibody (Alpha Omega Sciences) as described previously (24). (B) To examine HrcA recruitment within groEL2up, FLAG-tagged HrcA was expressed in WT M. tuberculosis (see Materials and Methods), and ChIP-qPCR was carried out using anti-FLAG antibody (Thermo Scientific). (C) Schematic presentation of the newly identified PhoP and previously reported HrcA binding sites (4) within the groEL2 regulatory region. The locations of binding sites are indicated by nucleotide positions relative to the translational start site of groEL2. The transcription start site (+1) is shown by an arrow. (D and E) To compare in vivo recruitments of PhoP in WT and ΔhrcA strains (D) and HrcA in WT and ΔphoP strains (E), fold enrichments were determined relative to the PCR signal from mock IP sample without adding antibody. Insets show comparable PhoP and HrcA expression in crude cell lysates of indicated mutants containing 10 μg of total protein; RpoB was used as the loading control. (F) To examine PhoP-HrcA interaction in vitro, crude extract expressing His6-tagged HrcA was incubated with glutathione-Sepharose previously immobilized with GST-PhoP. Fractions of bound proteins (lane 1) were analyzed by Western blotting using anti-HrcA (top) or anti-PhoP (bottom) antibody. As controls, glutathione-Sepharose was immobilized with GST alone (lane 2) or the resin alone (lane 3); lanes 4 and 5 resolved purified HrcA and GST-PhoP, respectively. (G) To confirm PhoP-HrcA interaction in vivo, crude cell lysates of the ΔphoP mutant expressing His6-tagged PhoP (p19Kpro-phoP) (Table 1) were incubated with preequilibrated Ni-NTA and eluted with 250 mM imidazole; left lane, input sample; middle lane, control elution from the crude lysate of cells lacking phoP expression; right lane, M. tuberculosis HrcA showing coelution with PhoP. (H) M-PFC experiment to examine the PhoP and HrcA interaction involved coexpression of indicated fusion constructs in M. smegmatis. Growth of transformants on 7H11-Kan-Hyg in the presence of TRIM indicated in vivo protein-protein association between PhoP and HrcA. Coexpression of empty vectors and the esat6-cfp10 pair were included as negative and positive controls, respectively. All of these strains grew well in the absence of TRIM. **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05.

Having shown recruitment of both PhoP and HrcA within the groEL2 promoter, we investigated whether that recruitment of the regulators is linked. In ChIP experiments, we observed a significant reduction of PhoP recruitment within the groEL2 regulatory region of the ΔhrcA strain relative to that for the WT bacteria (Fig. 3D). However, PhoP recruitments within the pks2 promoter (regulated by PhoP but not by HrcA) remained comparable between the WT and the mutant. The inset in the figure shows comparable levels of phoP expression in WT and the ΔhrcA M. tuberculosis. Likewise, HrcA recruitment within the groEL2 regulatory region but not Rv0991 (which is regulated by HrcA but not by PhoP) was significantly reduced in the ΔphoP mutant relative to that in WT bacteria (Fig. 3E). Thus, we conclude that the presence of both hrcA and phoP is necessary for effective recruitment of PhoP and HrcA, respectively, within the target promoter. Unfortunately, this experiment could not be extended to other heat shock-responsive promoters, as we were unable to observe a significant fold enrichment in ChIP-qPCR studies using anti-PhoP antibody (Fig. 3).

Having noted this link, we attempted an in vitro pulldown assay to investigate whether HrcA interacts with PhoP. In this experiment, glutathione transferase (GST)-PhoP was immobilized on glutathione-Sepharose followed by incubation with purified recombinant HrcA. Upon elution of column-bound proteins, we detected the presence of both proteins in the same fraction (Fig. 3F, lane 1). However, an identical experiment with only the GST tag (lane 2) or the resin alone (lane 3) did not detect HrcA, suggesting that PhoP interacts with HrcA. In an in vivo experiment, His-tagged PhoP was expressed in the ΔphoP mutant using the p19Kpro expression vector (14) as described previously (15). The cell lysate (Fig. 3G, input sample, left lane) was incubated with Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) beads, and following multiple washings with the binding buffer, bound proteins were eluted with imidazole. While the eluent showed the clear presence of HrcA (third lane), we were unable to detect HrcA from the cell lysate of the ΔphoP mutant carrying p19Kpro (empty vector control, second lane), suggesting specific interactions between PhoP and HrcA in vivo. We next utilized a previously reported mycobacterial protein fragment complementation assay (M-PFC) (16), in which the bait and prey plasmids were prepared as C-terminal fusions with complementary fragments of mDHFR (Table 1; see Materials and Methods). Next, Mycobacterium smegmatis transformants were selected on 7H10-kanamycin (Kan)-hygromycin (Hyg) plates either in the presence or in the absence of 15 μg/ml trimethoprim (TRIM). Although cells harboring empty vectors did not show any growth on 7H10-TRIM plates, cells coexpressing PhoP/HrcA grew well in the presence of TRIM (Fig. 3H). Together, the M-PFC results are consistent with the above in vitro and in vivo data to suggest that PhoP interacts with HrcA.

Probing PhoP-heat shock repressor protein-protein interactions.

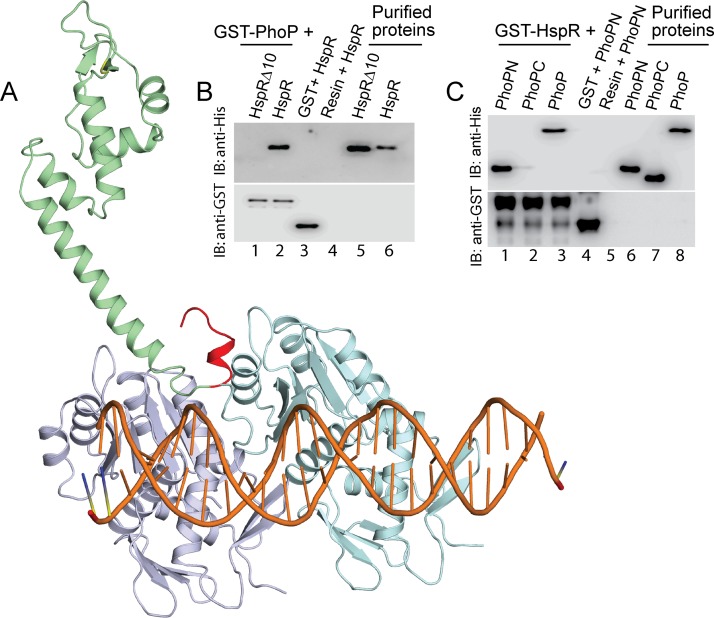

As structural data are not available, HspR and HrcA structures were predicted using the Phyre2 Web portal (17) (see Fig. S4 and S5, respectively). Using PDB identifier (ID) 3D6Z (18) as the template, Phyre2 predicted an HspR structure with 99.85% confidence, and a HrcA structure was predicted at a 90% confidence level using the PDB ID 1STZ (19) as the template. To probe the interaction(s) further, we docked HspR and HrcA structures individually onto the complete PhoP-DNA complex (PDB ID 5ED4) using the ZDock server (20). Based on the score, the ZDock predicted 10 different conformations of the PhoP-DNA-HspR complex. Strikingly, the structural analysis revealed that 7 of 10 conformations show a common binding site of HspR to the PhoP-DNA complex (see Fig. S4), thus generating a consensus binding pattern (Fig. 4A). However, despite predicting 10 different conformations, a consensus binding model was not apparent upon structural docking of HrcA onto the PhoP-DNA complex (Fig. S5). Considering the structural complexity of the macromolecular complex and limitations of “rigid body docking,” the above failure might be attributable to limitations of the prediction method. However, a closer inspection of the structural model of the HspR-PhoP-DNA complex suggests that the C-terminal region of HspR interacts with the N-terminal region of PhoP (Fig. 4A).

FIG 4.

Docking of HspR structure on PhoP-DNA complex. (A) The docking of HspR structural model on PhoP-DNA complex utilized a submission of the respective structural coordinates to the docking server ZDock (20) as detailed in Results. (B) To examine the role of the C-terminal 10 residues of HspR (shown in red in panel A) in PhoP-HspR interactions, crude lysates of cells expressing His6-tagged HspRΔ10 were incubated with glutathione-Sepharose, previously immobilized with GST-PhoP. Fractions of bound proteins (lane 1) were analyzed by Western blotting using anti-His (top) or anti-GST (bottom) antibody. Control sets include glutathione-Sepharose immobilized with GST alone (lane 3) or the resin alone (lane 4); lanes 5 and 6 resolve purified HspRΔ10 and HspR, respectively. (C) In vitro interactions of HspR and indicated PhoP domains (PhoPN and PhoPC) were investigated by incubating crude cell lysates of His6-tagged PhoP domains with glutathione-Sepharose previously immobilized with GST-HspR. The results suggest that the PhoPN, and not PhoPC, retains the ability to interact with HspR (see Results for more details). Note that PhoP N and PhoP C domain constructs, used in this study, were previously shown to be fully functional on their own (21).

To examine the accuracy of the predicted structural model, we analyzed the in vitro interactions between recombinant His-tagged HspRΔ10, lacking C-terminal 10 residues (residues 126 to 143) of HspR, with the GST-PhoP as described previously (11). Upon elution of column-bound proteins, we were unable to detect the presence of both PhoP and HspRΔ10 proteins in the same fraction (Fig. 4B, lane 1). However, under identical conditions, we detected both PhoP and full-length HspR in the same fraction (lane 2), suggesting that the PhoP-HspR interaction involves C-terminal residues of HspR. In vitro DNA binding assays with the purified WT and truncated proteins (as shown in Fig. S6A) suggested structural integrity of the truncated variant (Fig. S6B). As expected, in the M-PFC experiments, PhoP failed to demonstrate protein-protein interaction with HspRΔ10, the truncated repressor (Fig. S6C). From these results, we speculate that not a few residues in a stretch but possibly a constellation of amino acids contribute to protein-protein interactions.

Having confirmed the accuracy of the model showing possible interaction between PhoP and the C-terminal end of HspR, we next assessed the role of different stretches of the PhoP N domain in PhoP-HspR interactions. During in vitro pulldown assays with GST-HspR, mutant PhoP proteins (each with three potential HspR-contacting residues replaced with Ala) showed protein-protein interactions as effectively as WT PhoP (Fig. S7A). We next sought to probe the PhoP-HspR interaction using truncated PhoP domains, previously shown to be functional on their own (21). During in vitro experiments, PhoPN, comprising N-terminal PhoP residues 1 to 141, showed an effective protein-protein interaction with HspR (Fig. 4C, lane 1); however, PhoPC (comprising C-terminal PhoP residues 141 to 247), under identical conditions, failed to show an effective interaction with HspR (lane 2). To further confirm these results, we performed M-PFC experiments. As expected, cells coexpressing PhoPN and HspR but not PhoPC/HspR (Fig. S7B) supported M. smegmatis growth in the presence of TRIM. Taking these results together, we conclude that PhoPN interacts with the C-terminal end of HspR. It is noteworthy that the C-terminal hydrophobic tail of HspR is also known to be required for DnaK-assisted HspR functioning as a DNA binding transcriptional repressor (22).

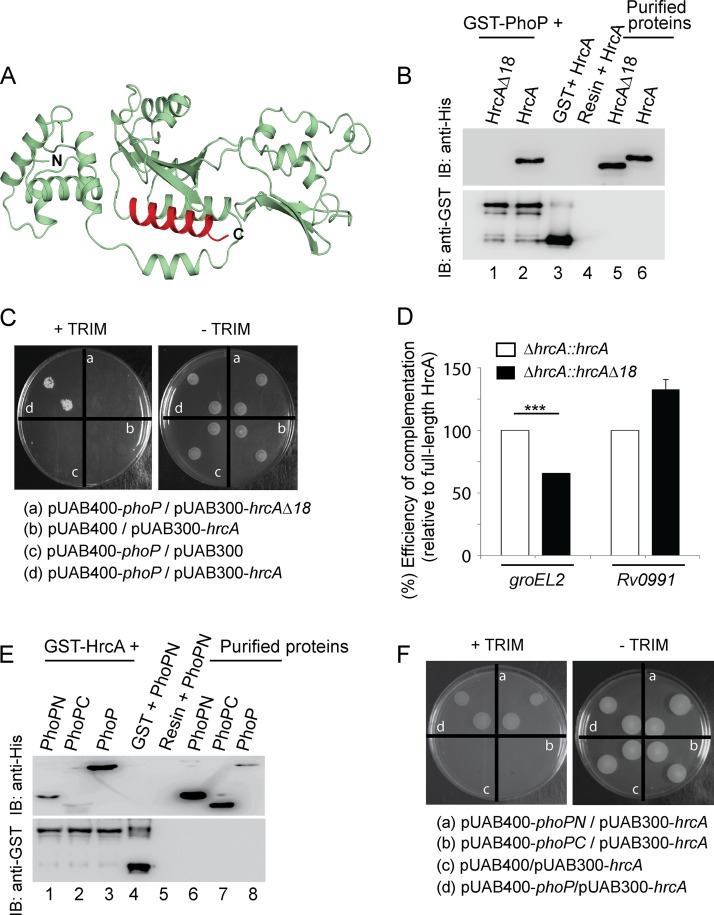

With the evidence showing the N domain of PhoP interacts with HspR, we next probed the PhoP-HrcA interaction more closely. Based on the HrcA structural model (Fig. 5A), we designed HrcAΔ18, a C-terminal truncated mutant of HrcA comprising amino acid residues 1 to 325 (Table 1). In vitro pulldown studies using GST-PhoP and truncated HrcA (His-tagged) (as described in Fig. 4B) suggest the C-terminal 18 residues of HrcA are essential for PhoP-HrcA interactions (Fig. 5B). These results were further confirmed by additional M-PFC experiments (Fig. 5C). Together, these results establish the specificity of PhoP-HrcA interactions. To examine the effect of C-terminal truncation of HrcA on its regulatory activity, we compared expression of groEL2 and that of Rv0991 (target genes of HrcA) (Fig. 2G) in a ΔhrcA strain complemented with truncated HrcA and the full-length HrcA, respectively (Fig. 5D). Strikingly, HrcAΔ18, unlike full-length HrcA, only partially complemented groEL2 expression. However, Rv0991 expression, which remains independent of PhoP-HrcA interactions, was restored by either of the two proteins. Thus, in conjunction with the above results, we conclude that the regulation of groEL2 expression requires PhoP-HrcA interaction, the lack of which accounts for the failure to restore groEL2 expression level in the ΔhrcA::hrcAΔ18 mutant (but not in the ΔhrcA::hrcA strain). Taken together with in vitro, ex vivo, and in vivo findings, these results suggest a pathway in which the interaction between a pair of repressors with a common nodal regulator controls the expression of specific heat shock-dependent genes.

FIG 5.

C-terminal end of HrcA interacts with the N-terminal domain of PhoP. (A) The HrcA structural model showing the C-terminal truncation (shown in red) was generated as described in Results. (B) To assess the importance of the C-terminal 18 residues of HrcA in PhoP-HrcA interactions, crude lysates of cells expressing His6-tagged HspRΔ10 were incubated with glutathione-Sepharose previously immobilized with GST-PhoP, and samples were analyzed as described in the legend for Fig. 4B. (C) M-PFC experiment to examine interaction between PhoP and truncated HrcA involved coexpression of indicated fusion constructs (including PhoP and HrcA as the positive control) in M. smegmatis as described in the legend for Fig. 3G. (D) Restoration of expression of indicated genes in the ΔhrcA mutant was examined via RT-qPCR by complementing with either the full-length or the truncated hrcA gene. The results suggest in vivo relevance of the C-terminal end of HrcA, a region involved in protein-protein interactions with PhoP. As a control, regulation of phoP-independent Rv0991 expression by the truncated HrcA remained unaffected. (E) In vitro interactions of HrcA and indicated PhoP domains (PhoPN and PhoPC) were investigated by incubating crude cell lysates of His6-tagged PhoP domains with glutathione-Sepharose previously immobilized with GST-HrcA. The results suggest that PhoPN, and not PhoPC, retains the ability to interact with HspR (see Results for more details). (F) M-PFC experiments to examine the interaction between HrcA and indicated PhoP domains involved coexpression of indicated fusion constructs (including PhoP and HrcA as the positive control) in M. smegmatis as described in the legend for Fig. 3G.

To further probe the PhoP-HrcA interaction, we next used purified PhoP domains (His tagged) and GST-HrcA (as described in Fig. 4C). Our results unambiguously prove that similar to HspR (11), PhoPN shows effective protein-protein interaction with HrcA (Fig. 5E). The results were also validated by M-PFC experiments using the full-length regulator pair as positive control (Fig. 5F). Taking these results together, we conclude the PhoP N domain also interacts with the C-terminal end of HrcA, the other M. tuberculosis heat shock repressor. An effort to quantify interaction affinity using alamarBlue at multiple TRIM concentrations yielded confusing results, possibly because of interference from HrcA and/or HspR homologs of M. smegmatis.

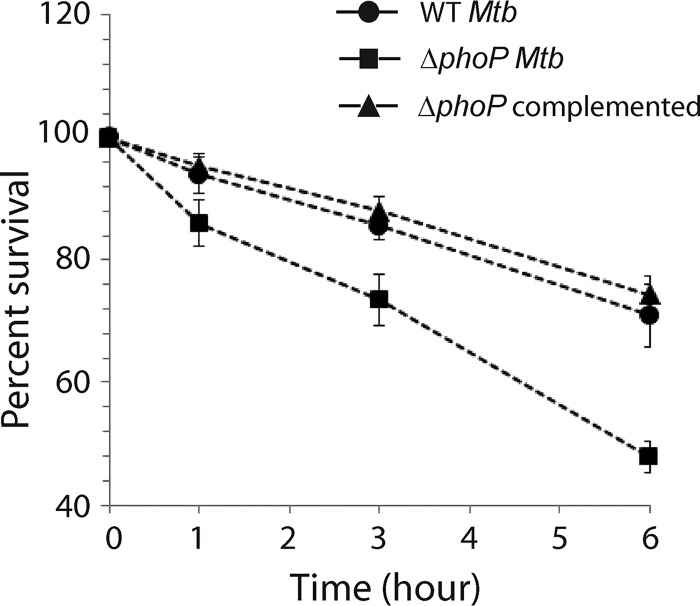

With a global impact of the phoP locus on the M. tuberculosis transcriptome (related to heat shock-responsive genes), we next investigated the impact of phoP on M. tuberculosis physiology under heat stress. Thus, we studied the role of the phoP locus on survival of the tubercle bacilli under heat stress. We exposed WT M. tuberculosis and the ΔphoP and complemented mutant strains to 45°C for various lengths of time and examined their survival by CFU plating (Fig. 6). We observed that the ΔphoP mutant was significantly more susceptible to heat shock than the WT strain (compare 48% ± 2% survival of the mutant versus 71% ± 5% survival of the WT bacilli grown under 6 h of heat shock). However, the ΔphoP complemented strain, under identical conditions, showed comparable survival to that of the WT bacilli. In keeping with the regulatory role of the phoP locus, these results demonstrate that phoP plays a major role in the survival of M. tuberculosis under heat shock conditions.

FIG 6.

Deletion of phoP from M. tuberculosis H37Rv reduces its survivability under heat stress. WT and ΔphoP M. tuberculosis strains were compared for survival under increasing heat stress by CFU counting (n = 3). Although the ΔphoP strain grew comparably well as the WT bacilli under normal conditions, it remained significantly growth defective under heat stress. However, the growth defect of the mutant was completely restored in the complemented mutant. Note that 100% survival of the bacilli is assumed at the zero time point.

DISCUSSION

The results reported in this study provide new biological insights into how virulence-associated phoP plays a global role in the regulation of heat shock-responsive gene expression. We identify a new protein-protein interaction between PhoP and one of the heat shock repressors, HrcA, which is required for the repression of heat shock-inducible genes under normal conditions. These results are not merely an extension of the previously studied heat shock-specific acr2 regulation for the following reasons. First, our results comprise the first account of global regulation of the heat shock response in M. tuberculosis. Second, independent functioning of the two genome-encoded heat shock repressors (HspR and HrcA) has been shown clearly. The third and perhaps most interesting finding highlights the role of the virulence regulator PhoP as a common requirement for effective functioning of both heat shock repressors via specific protein-protein interactions. We further demonstrate that effective interactions involve the N-terminal domain of PhoP and the C-terminal end of heat shock repressors. We postulate that PhoP-repressor protein-protein interactions, in addition to their respective DNA binding functions, regulate the expression of specific heat shock-inducible genes in M. tuberculosis. Together, these results account for the lowered survival of the ΔphoP strain relative to the WT bacilli under increasing heat stress.

Having shown the roles of both PhoP and HrcA in regulating heat shock-responsive genes (Fig. 1 and 2), we next considered whether these regulators are functionally connected. Our results demonstrate that PhoP-HrcA protein-protein interaction accounts for concomitant binding of both the regulators as corepressors of groEL2 expression (Fig. 3). These results take on more significance in light of the previous finding that PhoP and HspR function as corepressors of heat shock-inducible acr2 expression (11). We further utilized ΔhrcA and ΔhspR mutants in our in vivo regulatory studies to determine that phoP, hrcA, and hspR loci together coordinate a global role in heat shock-inducible gene expression. What offers a new mechanistic insight is the finding that the regulation of a specific set of heat shock-inducible genes is dependent on multiple protein-protein interactions, with PhoP as the common transcriptional regulator. We propose that the availability of repressor (HspR or HrcA) binding sites within the target promoters most likely determines which interaction, at any given time, is more relevant.

Notably, PhoP-HrcA-groEL2 regulation follows a hybrid model and is clearly different from the PhoP-HspR-acr2 regulatory scheme. This is because while PhoP and HrcA function as corepressors of groEL2 expression under normal conditions (Fig. 1C and 2A, respectively), during heat shock, PhoP activates groEL2 expression (Fig. 1D) without any assistance from HrcA (Fig. 2A). Although this model is consistent with PhoP binding to the groEL2 promoter under both normal and stress conditions (Fig. 3A), this situation is unlike the regulation of acr2 expression, where both PhoP and HspR bind and leave the target site together (11). Therefore, PhoP appears to be interacting with HrcA only under normal conditions. However, there are two apparent contradictions. First, while the presence of HrcA is essential for PhoP recruitment under normal conditions (Fig. 3D), how is PhoP recruited within the groEL2 promoter under heat stress (Fig. 3A) in the absence of HrcA (Fig. 3B)? The second related issue concerns the mechanism of activation of gene expression by PhoP under heat shock conditions. The question remains whether what we observed in the ΔphoP mutant is attributable to phoP-dependent activation or whether it is due to the absence of a functional PhoP-HrcA interaction leading to derepression of target promoter activity. From the observations that (i) groEL2 is expressed at a significantly lower level in the ΔphoP strain (relative to WT M. tuberculosis) only under heat shock conditions and (ii) PhoP shows recruitment within groEL2 promoter under heat stress (even in the absence of HrcA), we propose that PhoP functions as a specific activator of groEL2 expression during heat stress. While we cannot rule out the possibility of PhoP functioning independently under heat shock conditions, two explanations might account for PhoP functioning during heat stress. Either there is involvement of another protein/factor along with PhoP under heat shock conditions or the regulator during stress undergoes a conformational change which provides the binding energy so that it can now bind to the target promoter(s) on its own.

While the DNA binding mechanism of PhoP is well known (23), our knowledge of protein-protein interactions involving the major virulence regulator has been limited to a few examples (15, 24). Thus, biochemical studies are required to identify newer working partners of the regulator. Having identified HspR (11) and HrcA (this study) as functional partners of PhoP, we attempted to decipher the origin of binding specificity. Our structure-guided docking results provide new insights into the protein-protein interaction that remain unavailable from the structural data alone. Although we cannot rule out the possibility of involvement of other regions of PhoP, here, we identified specific interactions between the PhoP N domain and both HspR and HrcA (Fig. 4 and 5, respectively). Thus, the likelihood that the interactions are nonspecific seems very low. However, we were unable to observe simultaneous recruitment of both PhoP and HrcA using an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) as we had previously demonstrated in PhoP-HspR-acr2 regulatory scheme (11). Therefore, it is arguable whether both the regulators are bound to groEL2 promoter (at the same time) resulting in DNA looping. We suggest the following explanations that support the proposed mechanism. First, the in vivo recruitment of PhoP and HrcA under normal conditions was dependent on each other (Fig. 3). Second, the binding site of PhoP within the promoter was ∼50 bp away from the HrcA binding site (4) (Fig. 3C), a result which is analogous to PhoP and HspR recruitment within ∼50 bases of the acr2 promoter (11) and consistent with DNA looping. Finally, the fact that the DNA binding functions are restricted to the C domain of PhoP (21) and N domain of HspR/HrcA (25, 26), these results showing interactions between PhoP N domain and the repressor (HspR/HrcA) C domains are remarkably consistent with our previously proposed model postulating PhoP-HspR functioning as corepressors (11).

The results showing activation of groEL2, an essential chaperonin gene (27), by the phoP locus during heat shock stress suggest that the presence of phoP is required for groEL2 activation (Fig. 1D). Consistent with this result, unlike acr2 regulation, even under heat shock conditions, PhoP is recruited within the regulatory region of groEL2 (Fig. 3A). These results are in keeping with the higher sensitivity of the mutant strain (relative to the WT bacilli) to increasing heat stress. Notably, while the ΔphoP mutant showed considerably higher susceptibility to heat shock than WT bacteria, complementation of the mutant bacilli restored the bacterial survival pattern to the WT level. Although we cannot rule out the possibility of another PhoP-dependent mycobacterial response impacting the survival phenotype of the mutant under heat stress conditions, the above results showing phoP-dependent regulation of a large number of heat shock-responsive genes most likely through specific interactions with both the mycobacterial heat shock repressors facilitate an integrated view of our results. Together, these findings provide new mechanistic insights of striking significance into the regulation of heat shock-responsive groEL2 of M. tuberculosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

E. coli DH5α and E. coli BL21(DE3) strains were grown at 37°C in LB medium containing appropriate antibiotics and used for cloning and for overexpression of mycobacterial proteins, respectively. The ΔphoP and complemented mutants were described previously (28). The construction of the ΔhspR and ΔhrcA strains and the complemented mutants is described below. M. tuberculosis strains, as listed in Table S3 in the supplemental material, were grown aerobically at 37°C in Middlebrook 7H9 liquid broth (containing 0.2% glycerol, 0.05% Tween 80, and 10% albumin-dextrose-catalase [ADC]) or on 7H10 agar medium (containing 0.5% glycerol and 10% oleic acid-albumin-dextrose-catalase [OADC]). For heat shock stress, M. tuberculosis was grown as described previously (11). Transformation of wild-type (WT) and mutant M. tuberculosis strains and selection of transformants on appropriate antibiotics were carried out as described previously (29).

RNA isolation and microarray analysis.

Total RNA from M. tuberculosis grown in 7H9 medium was isolated and purified as described elsewhere (30). Briefly, 25 ml of bacterial culture of each strain was grown to mid-log phase (optical density at 600 nm [OD600] of 0.4 to 0.6) at 37°C in 7H9 medium (pH 7.0) containing 10% ADC with shaking at 90 rpm. In each case, the cultures were divided in half; the first half was used as a control and the other half of the cultures was subjected to heat shock at 45°C for 1 h 30 min. This was followed by the addition of 75 ml 5 M guanidinium thiocyanate (GTC), 25 mM sodium citrate, 1% β-mercaptoethanol, and 0.5% Tween 80. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation, washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and lysed by resuspending in acetate-EDTA buffer (10 mM Na-acetate, 2 mM EDTA) containing acid-washed glass beads (one-sixth of the final volume; Sigma), 2% SDS, and acid-saturated phenol (pH 4.5) (Ambion). Following incubation at 65°C for 30 min, with intermittent vortexing (3 × 20 s) every 10 min, total RNA was extracted with chloroform-isoamyl alcohol and precipitated with chilled ethanol. To remove genomic DNA, RNA was treated with RNase-free DNase I (Invitrogen) for 20 min at room temperature; the quality of RNA samples was assessed by intactness of 23S and 16S rRNA using formaldehyde-agarose gel electrophoresis, and RNA concentrations were determined by measuring the absorbance at 260 nm.

For microarray analysis, the purity and integrity of RNA were examined by microfluidics-based capillary electrophoresis using an RNA 6000 Nano kit Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies). The sample labeling was performed using a Quick-Amp labeling kit, One Color (Agilent Technologies). Next, a cDNA master mix was added to the denatured RNA sample and incubated at 40°C for 2 h for double-stranded cDNA synthesis. For cRNA synthesis, newly synthesized double-stranded cDNA was used as the template, and in vitro transcription was performed for 2 h 30 min at 40°C to incorporate Cy3 CTP. The fragmentation of labeled cRNA and hybridization were carried out using the Gene Expression Hybridization kit (Agilent Technologies). The hybridized slides were washed with Gene Expression wash buffers (Agilent Technologies) and scanned using the Microarray Scanner (Agilent Technologies). Data extraction from images was performed using Feature Extraction software (version 11.5.1.1; Agilent Technologies). The extracted raw data were analyzed using GeneSpring GX software (Agilent Technologies). Normalization of the data was performed in GeneSpring GX using the 75th percentile shift method, and fold change values were obtained by comparing test samples with respect to specific control samples. Genes showing fold upregulation of >0.6 (log base 2) or fold downregulation <−0.6 (log base 2) in the test samples relative to that in the control sample were identified. P values of replicate data sets were calculated by Student’s t test based on a volcano plot algorithm. Differentially regulated genes were clustered using hierarchical clustering based on a Pearson coefficient correlation algorithm to identify significant gene expression patterns. Genes were classified based on functional category and pathways using the biological analysis tool DAVID (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/).

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR.

Total RNA was extracted from each bacterial culture grown with or without heat shock as described above. cDNA synthesis and PCRs were performed using a Superscript III platinum-SYBR green one-step qRT-PCR kit (Invitrogen) with appropriate primer pairs (200 nM). RT-qPCR cycling conditions in a real-time PCR detection system (Applied Biosystems) were as follows: 50°C for 45 min and 95°C for 5 min, each for one cycle followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 65°C for 30 s. To evaluate the PCR efficiency, a standard curve was generated for each pair of primers using serially diluted RNA samples, and PCR efficiency was always within the acceptable range of 95% to 105%. The endogenously expressed M. tuberculosis gapdh (Rv1436) was used to normalize each sample, and approximate fold difference was calculated using the ΔΔCT method (31). The average fold changes in expression levels of genes and standard deviations from replicates of experiments were determined from at least three independent RNA preparations. The oligonucleotide primers used in RT-qPCR experiments are listed in Table S1. Control reactions with platinum Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen) confirmed the absence of genomic DNA in all our RNA preparations.

Cloning.

Isolation and purification of nucleic acids, digestion with restriction enzymes, other enzymatic manipulations, and analyses of nucleic acids or fragments by agarose gel electrophoresis were according to standard procedures (11). An M. tuberculosis hspR overexpression construct has been described earlier (11). Likewise, truncated hspR (containing 348 bp of the open reading frame [ORF] excluding the terminal 30 bp), full-length hrcA (containing 1,029 bp of the ORF), and truncated hrcA (containing 975 bp of the ORF excluding the terminal 54 bp) were cloned in T7-lac-based expression system pET15b (Novagen) as recombinant fusion proteins containing an N-terminal His6 tag. The cloning strategy resulted in pET-hspRΔ10, pET-hrcA, and pET-hrcAΔ18 comprising 116 amino acids of HspR lacking the C-terminal 10 residues of HspR, 343 amino acids of full-length HrcA, and 325 amino acids of HrcA lacking the C-terminal 18 residues of HrcA, respectively. GST-tagged PhoP and HspR have been described earlier (11, 32). Plasmid pGEX-hrcA expressing HrcA with an N-terminal GST tag was generated by cloning PCR-derived hrcA ORF fragment between BamHI and XhoI sites of pGEX 4T-1 (GE Healthcare). To complement hrcA and hspR expression in the respective mycobacterial mutants, the ORFs were cloned and expressed in mycobacterial expression vector pSTKi (13). To express FLAG-tagged hrcA in M. tuberculosis, the ORFs were cloned and expressed in mycobacterial expression vector p19Kpro (14). The list of oligonucleotide primers used in cloning is provided in Table S2. In all cases, nucleotide sequences of the constructs were verified by automated DNA sequencing.

Construction of M. tuberculosis gene replacement mutants.

The 5′ homology (1,030 bp encompassing bp −1000 to +30) and the 3′ homology (1,030 bp encompassing the distal 30 bases of the respective ORFs and 1,000 bases downstream) of Rv0353 and Rv2374c, respectively, were amplified from the M. tuberculosis H37Rv genomic DNA by KOD DNA polymerase (Toyobo Biosciences) using appropriate primer pairs (Table S2). The primers contained pfIMI sites in the flanks to yield ends compatible for cloning with the hyg cassette (amplified using specific primers) and oriEp cosI fragment generated from p0004S (a kind gift of W. Jacob). Also, EcoRV sites were inserted both in the 5′ flank of the forward primer and the 3′ flank of the reverse primer. The amplicons comprising homologous sequences at both the 5′ and 3′ ends and hyg cassette were next digested with pfIMI and ligated to the oriEp cosI fragment to generate the allelic exchange substrate (AES). Next, the AES was digested with EcoRV to generate linear AES for recombineering. To generate the mutants, M. tuberculosis H37Rv was electroporated with pNit-ET (a kind gift of E. Rubin [33]), the transformed cells were grown until an A600 of 0.4, the expression of recombineering proteins was induced by the addition of 5 μM isovaleronitrile, and the cultures were allowed to grow until an A600 of 0.8. Electrocompetent cells, prepared as described previously (12), were then electroporated with 200 ng of linear AES. Transformed colonies were selected on a 7H11 agar plate containing 100 μg/ml Hyg; a few colonies were picked up, cells were grown, and genomic DNA was isolated. Finally, the potential colonies were screened by PCR using specific primers to confirm the gene replacement mutants. The ΔphoP, ΔsigE, and ΔsigH mutants of M. tuberculosis and the correspondingly complemented strains have been described earlier (28, 34, 35). The following antibiotics were used as appropriate: hygromycin (Hyg), 100 μg/ml; kanamycin (Kan), 20 μg/ml. Studies related to M. tuberculosis H37Rv strains were carried out in a biosafety level 3 (BSL3) facility per institutional biosafety guidelines.

Southern blot hybridization.

For Southern blot analyses, approximately 1 μg of genomic DNA of WT and mutant M. tuberculosis strains was digested with BamHI and resolved by agarose gel electrophoresis. The DNA samples were next transferred onto an Immobilon membrane (Millipore) by vacuum-based blotting and hybridized with radiolabeled gene-specific probes. The hrcA- and hspR-specific probes were generated by PCR using [α-32P]dCTP (BRIT, India) and oligonucleotide primers (Table S2), which were used to clone the respective ORFs; prehybridization, hybridization, and washing steps were carried out as described previously (36). The results were developed and digitalized with a Fuji phosphorimager (GE Healthcare).

Proteins.

M. tuberculosis PhoP and its domains were expressed and purified as described previously (21). Full-length and truncated HrcA and truncated HspR were expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) as fusion proteins containing an N-terminal His6 tag and purified by immobilized metal-affinity chromatography (Ni-NTA; Qiagen) as described previously for HspR (11). Both the full-length and the truncated variants of HspR and HrcA were expressed with N-terminal GST tags, as described for GST-PhoP (11). Finally, the proteins were stored in buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.9), 500 mM NaCl, and 10% glycerol. In all cases, the purity was verified by SDS-PAGE, protein concentrations were determined by Bradford reagent with bovine serum albumin (BSA) as the standard, and the results were compared with Quant-iT protein assay kits/Qubit fluorometer (Invitrogen) and expressed as equivalents of protein monomers.

Immunoblotting.

Cell lysates of M. tuberculosis were resolved by 12% SDS-PAGE and visualized by Coomassie blue staining or by Western blot analysis. For immunoblotting, resolved samples were electroblotted onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore) and were detected by affinity-purified anti-PhoP, anti-HspR, and anti-HrcA antibodies elicited in rabbit (Bioneeds). RNA polymerase was used as a loading control and was detected with a monoclonal antibody against the β subunit of RNA polymerase, RpoB (Abcam). Anti-His and anti-GST antibodies were from GE Healthcare. Goat anti-rabbit and goat anti-mouse secondary antibodies (Abexome Biosciences) conjugated to horseradish peroxidase were used. Blots were developed with Luminata Forte chemiluminescence reagent (Millipore).

Chromatin IP.

ChIP experiments using actively growing cultures of M. tuberculosis were performed as described previously (37). DNA-protein complexes in growing cells were crosslinked by 1% formaldehyde for 20 min, and cross-linking was quenched by the addition of 125 mM glycine. Immunoprecipitation (IP) was carried out using affinity-purified anti-PhoP (Alpha Omega Sciences) or anti-FLAG antibodies (Thermo Scientific) and protein A/G-agarose beads (Pierce). qPCR was performed using PAGE-purified primer pairs (Sigma) (Table S1) that contained appropriate promoter regions of interest. Typically, 40 cycles of amplifications were carried out in a real-time PCR detection system (Applied Biosystems) using serially diluted DNA samples (mock, IP treated, and total input). In vivo recruitment of PhoP or HrcA was examined by ChIP-qPCR using appropriate dilutions of IP DNA in a reaction buffer containing SYBR green mix (Invitrogen), 0.2 μM page-purified primers, and 1 U Platinum Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen). Enrichment of PCR signal from the anti-PhoP or anti-FLAG IP relative to the signal from an IP experiment without adding any antibody (mock) was measured to determine the efficiency of recruitment. The specificity of PCR enrichment was verified by performing ChIP-qPCR on identical IP samples using gapdh-specific primers. Data represent the means of duplicate qPCR measurements using at least three independent M. tuberculosis cultures. In all cases, melting curve analysis was carried out to confirm amplification of a single product.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays.

Purified proteins (HspR and its truncated variant) were used to assess DNA binding to the acr2up2 promoter fragment as described previously (11). The PCR-amplified fragment was end labeled with [γ-32P]ATP (1,000 Ci nmol−1) using T4 polynucleotide kinase and purified from the free label by Sephadex G-50 spin columns (GE Healthcare). Next, various concentrations of purified proteins were incubated with the end-labeled probe in a total volume of 10 or 20 μl binding mix (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 50 mM NaCl, 0.2 mg/ml of bovine serum albumin, 10% glycerol, 1 mM dithiothreitol, ≈50 ng of labeled DNA probe, and 0.2 μg of sheared herring sperm DNA) at 20°C for 20 min. To resolve DNA-protein complexes, samples were analyzed by electrophoresis on a 6% (wt/vol) nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel in 0.5× TBE (89 mM Tris base, 89 mM boric acid, and 2 mM EDTA) at 70 V and 4°C. The position of the radioactive material was determined by exposure to a phosphor storage screen, and bands were quantified by the phosphorimager (Fuji).

Mycobaterial protein fragment complementation assays.

To express M. tuberculosis PhoP or its domains in M. smegmatis, the phoP gene and its domain constructs were cloned in the integrative vector pUAB400 (Kanr) (Table 1) between MfeI and HindIII sites, as described previously (11). Similarly, hrcA, truncated hrcA, and truncated hspR were cloned in episomal plasmid pUAB300 (Hygr) (Table 1) between BamHI/HindIII sites to generate pUAB300-hrcA, pUAB300-hrcAΔ18, and pUAB300-hspRΔ10, respectively, as described for pUAB300-hspR (11). The constructs were verified by DNA sequencing. Next, cotransformed cells were selected on 7H10-Kan-Hyg plates, and M-PFC experiments were performed as described previously (11). As a positive control, ESAT-6/CFP-10 expressing constructs used in M-PFC experiments have been reported earlier (24).

Data availability.

The data reported here, including a complete list of genes, have been deposited in the NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus and are accessible through GEO series accession number GSE100596.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by, a research grant (to D.S.) from SERB (EMR/2016/004904), Department of Science and Technology (DST), and by intramural support from the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), Government of India. R.R.S. and R.S. were supported by CSIR; D.A. and P.R.S. were supported by SERB, DST and DBT, respectively, for their predoctoral fellowships.

The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

We thank Arthur Landy for critical reading of the manuscript. We also thank G. Marcela Rodriguez and Issar Smith (The Public Health Research Institute, New Jersey Medical School, UMDNJ) for ΔphoP and the complemented M. tuberculosis strains, Eric Rubin (Harvard School of Public Health) for the pNIT plasmid, Adrie Steyn (University of Alabama) and Ashwani Kumar (CSIR-IMTECH) for pUAB300/pUAB400 plasmids, and Hayden T. Pacl (Steyn Lab, University of Alabama) for generating the heat map from the microarray data. We thank Roohi Bansal for preliminary M-PFC results, V. Anil Kumar for helpful discussions, and Renu Sharma for technical assistance. We acknowledge Genotypic Technology Private Limited (India) for the microarray results and data analysis reported in this work.

We declare no conflict of interest.

R.R.S., D.A., P.R.S., R.S., V.K.N., S.K., and D.S. designed the research; R.R.S., D.A., P.R.S., R.S., and S.K. performed the research; D.A., V.K.N., and S.K. contributed new reagents; R.R.S., R.S., S.K., and D.S. analyzed the data; D.S. conceived and coordinated the study and wrote the paper; R.R.S., V.K.N., and S.K contributed to writing the final version of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.00013-19.

REFERENCES

- 1.Monahan IM, Betts J, Banerjee DK, Butcher PD. 2001. Differential expression of mycobacterial proteins following phagocytosis by macrophages. Microbiology 147:459–471. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-2-459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schnappinger D, Ehrt S, Voskuil MI, Liu Y, Mangan JA, Monahan IM, Dolganov G, Efron B, Butcher PD, Nathan C, Schoolnik GK. 2003. Transcriptional adaptation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis within macrophages: insights into the phagosomal environment. J Exp Med 198:693–704. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asea A, Kabingu E, Stevenson MA, Calderwood SK. 2000. HSP70 peptide-bearing and peptide-negative preparations act as chaperokines. Cell Stress Chaperones 5:425–431. doi:. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stewart GR, Wernisch L, Stabler R, Mangan JA, Hinds J, Laing KG, Young DB, Butcher PD. 2002. Dissection of the heat-shock response in Mycobacterium tuberculosis using mutants and microarrays. Microbiology 148:3129–3138. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-10-3129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee BY, Horwitz MA. 1995. Identification of macrophage and stress-induced proteins of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Clin Invest 96:245–249. doi: 10.1172/JCI118028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stewart GR, Snewin VA, Walzl G, Hussell T, Tormay P, O'Gaora P, Goyal M, Betts J, Brown IN, Young DB. 2001. Overexpression of heat-shock proteins reduces survival of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the chronic phase of infection. Nat Med 7:732–737. doi: 10.1038/89113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stewart GR, Newton SM, Wilkinson KA, Humphreys IR, Murphy HN, Robertson BD, Wilkinson RJ, Young DB. 2005. The stress-responsive chaperone alpha-crystallin 2 is required for pathogenesis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol Microbiol 55:1127–1137. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raman S, Song T, Puyang X, Bardarov S, Jacobs WR Jr, Husson RN. 2001. The alternative sigma factor SigH regulates major components of oxidative and heat stress responses in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Bacteriol 183:6119–6125. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.20.6119-6125.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frigui W, Bottai D, Majlessi L, Monot M, Josselin E, Brodin P, Garnier T, Gicquel B, Martin C, Leclerc C, Cole ST, Brosch R. 2008. Control of M. tuberculosis ESAT-6 secretion and specific T cell recognition by PhoP. PLoS Pathog 4:e33. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0040033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee JS, Krause R, Schreiber J, Mollenkopf HJ, Kowall J, Stein R, Jeon BY, Kwak JY, Song MK, Patron JP, Jorg S, Roh K, Cho SN, Kaufmann SH. 2008. Mutation in the transcriptional regulator PhoP contributes to avirulence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Ra strain. Cell Host Microbe 3:97–103. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh R, Anil Kumar V, Das AK, Bansal R, Sarkar D. 2014. A transcriptional co-repressor regulatory circuit controlling the heat-shock response of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol Microbiol 94:450–465. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Kessel JC, Hatfull GF. 2007. Recombineering in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat Methods 4:147–152. doi: 10.1038/nmeth996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parikh A, Kumar D, Chawla Y, Kurthkoti K, Khan S, Varshney U, Nandicoori VK. 2013. Development of a new generation of vectors for gene expression, gene replacement, and protein-protein interaction studies in mycobacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 79:1718–1729. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03695-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Smet KA, Kempsell KE, Gallagher A, Duncan K, Young DB. 1999. Alteration of a single amino acid residue reverses fosfomycin resistance of recombinant MurA from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Microbiology 145:3177–3184. doi: 10.1099/00221287-145-11-3177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anil Kumar V, Goyal R, Bansal R, Singh N, Sevalkar RR, Kumar A, Sarkar D. 2016. EspR-dependent ESAT-6 protein secretion of Mycobacterium tuberculosis requires the presence of virulence regulator PhoP. J Biol Chem 291:19018–19030. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.746289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singh A, Mai D, Kumar A, Steyn AJ. 2006. Dissecting virulence pathways of Mycobacterium tuberculosis through protein-protein association. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:11346–11351. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602817103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kelley LA, Mezulis S, Yates CM, Wass MN, Sternberg MJ. 2015. The Phyre2 web portal for protein modeling, prediction and analysis. Nat Protoc 10:845–858. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2015.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Newberry KJ, Huffman JL, Miller MC, Vazquez-Laslop N, Neyfakh AA, Brennan RG. 2008. Structures of BmrR-drug complexes reveal a rigid multidrug binding pocket and transcription activation through tyrosine expulsion. J Biol Chem 283:26795–26804. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804191200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu J, Huang C, Shin DH, Yokota H, Jancarik J, Kim JS, Adams PD, Kim R, Kim SH. 2005. Crystal structure of a heat-inducible transcriptional repressor HrcA from Thermotoga maritima: structural insight into DNA binding and dimerization. J Mol Biol 350:987–996. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pierce BG, Wiehe K, Hwang H, Kim BH, Vreven T, Weng Z. 2014. ZDOCK server: interactive docking prediction of protein-protein complexes and symmetric multimers. Bioinformatics 30:1771–1773. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pathak A, Goyal R, Sinha A, Sarkar D. 2010. Domain structure of virulence-associated response regulator PhoP of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: role of the linker region in regulator-promoter interaction(s). J Biol Chem 285:34309–34318. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.135822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bandyopadhyay B, Das Gupta T, Roy D, Das Gupta SK. 2012. DnaK dependence of the mycobacterial stress-responsive regulator HspR is mediated through its hydrophobic C-terminal tail. J Bacteriol 194:4688–4697. doi: 10.1128/JB.00415-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.He X, Wang L, Wang S. 2016. Structural basis of DNA sequence recognition by the response regulator PhoP in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Sci Rep 6:24442. doi: 10.1038/srep24442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bansal R, Anil Kumar V, Sevalkar RR, Singh PR, Sarkar D. 2017. Mycobacterium tuberculosis virulence-regulator PhoP interacts with alternative sigma factor SigE during acid-stress response. Mol Microbiol 104:400–411. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hobman JL. 2007. MerR family transcription activators: similar designs, different specificities. Mol Microbiol 63:1275–1278. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown NL, Stoyanov JV, Kidd SP, Hobman JL. 2003. The MerR family of transcriptional regulators. FEMS Microbiol Rev 27:145–163. doi: 10.1016/S0168-6445(03)00051-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stapleton MR, Smith LJ, Hunt DM, Buxton RS, Green J. 2012. Mycobacterium tuberculosis WhiB1 represses transcription of the essential chaperonin GroEL2. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 92:328–332. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walters SB, Dubnau E, Kolesnikova I, Laval F, Daffe M, Smith I. 2006. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis PhoPR two-component system regulates genes essential for virulence and complex lipid biosynthesis. Mol Microbiol 60:312–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goyal R, Das AK, Singh R, Singh PK, Korpole S, Sarkar D. 2011. Phosphorylation of PhoP protein plays direct regulatory role in lipid biosynthesis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Biol Chem 286:45197–45208. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.307447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Amin-Ul Mannan M, Sharma S, Ganesan K. 2009. Total RNA isolation from recalcitrant yeast cells. Anal Biochem 389:77–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2009.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. 2008. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat Protoc 3:1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gupta S, Pathak A, Sinha A, Sarkar D. 2009. Mycobacterium tuberculosis PhoP recognizes two adjacent direct-repeat sequences to form head-to-head dimers. J Bacteriol 191:7466–7476. doi: 10.1128/JB.00669-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wei JR, Krishnamoorthy V, Murphy K, Kim JH, Schnappinger D, Alber T, Sassetti CM, Rhee KY, Rubin EJ. 2011. Depletion of antibiotic targets has widely varying effects on growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:4176–4181. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018301108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Manganelli R, Voskuil MI, Schoolnik GK, Smith I. 2001. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis ECF sigma factor sigmaE: role in global gene expression and survival in macrophages. Mol Microbiol 41:423–437. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Manganelli R, Voskuil MI, Schoolnik GK, Dubnau E, Gomez M, Smith I. 2002. Role of the extracytoplasmic-function sigma factor sigma(H) in Mycobacterium tuberculosis global gene expression. Mol Microbiol 45:365–374. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fol M, Chauhan A, Nair NK, Maloney E, Moomey M, Jagannath C, Madiraju MV, Rajagopalan M. 2006. Modulation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis proliferation by MtrA, an essential two-component response regulator. Mol Microbiol 60:643–657. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Edgar R, Domrachev M, Lash AE. 2002. Gene Expression Omnibus: NCBI gene expression and hybridization array data repository. Nucleic Acids Res 30:207–210. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data reported here, including a complete list of genes, have been deposited in the NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus and are accessible through GEO series accession number GSE100596.