Abstract

Context.

Identifying factors that affect terminally ill patients’ preferences for and actual place of death may assist patients to die wherever they wish.

Objective.

The objective of this study was to investigate factors associated with preferred and actual place of death for cancer patients in Johannesburg, South Africa.

Methods.

In a prospective cohort study at a tertiary hospital in Johannesburg, South Africa, adult patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers were enrolled from 2016 to 2018. Study nurses interviewed the patients at enrollment and conducted postmortem interviews with the caregivers.

Results.

Of 324 patients enrolled, 191 died during follow-up. Preferred place of death was home for 127 (66.4%) and a facility for 64 (33.5%) patients; 91 (47.6%) patients died in their preferred setting, with a kappa value of congruence of 0.016 (95% CI = −0.107, 0.139). Factors associated with congruence were increasing age (odds ratio [OR]: 1.03, 95% CI: 1.00–1.05), use of morphine (OR: 1.87, 95% CI: 1.04–3.36), and wanting to die at home (OR: 0.44, 95% CI: 0.24–0.82). Dying at home was associated with increasing age (OR 1.03, 95% CI 1.00–1.05) and with the patient wishing to have family and/or friends present at death (OR 6.73, 95% CI 2.97–15.30).

Conclusion.

Most patients preferred to die at home, but most died in hospital and fewer than half died in their preferred setting. Further research on modifiable factors, such as effective communication, access to palliative care and morphine, may ensure that more cancer patients in South Africa die wherever they wish. J Pain Symptom Manage 2019;57:923–932. © 2019 American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Palliative care, preferred place of death, actual place of death, cancer patients, sub-Saharan Africa, prospective study

Introduction

Death in the patient’s preferred setting is increasingly considered a valid indicator of effective palliative care.1 Reports from high-income countries (HICs) suggest that most patients prefer to die at home (60%—93.5%), whereas few (0.4%—4.9%) preferred to die in a hospital or other health care facility.1-3 However, Italian patients who preferred a hospital death did not want to burden family as well as perceived hospital as a safer care setting.3

Population surveys from lower and middle income countries indicate mixed preferences, with 83% in India, 52.7% in Kenya, and 36% in Namibia preferring home death.4-6 In China, cancer patients were more likely to prefer home death (53.6%), especially those with less education, living with close family, or those in rural areas,7 whereas in sub-Saharan Africa, a health care facility was the preferred place of care at end of life (HIV/AIDS), owing to lack of support for families providing home care.8 Our recent work highlights the burden on family caregivers of cancer patients at end of life.9

In HICs, death at home is associated with patient’s preference, family and caregiver support, patient’s low functional status, having an advanced directive, and availability of home-based palliative care.10-12 Death in hospital is associated with previous hospitalization, higher level of functioning, and patients’ and families’ expectation for cure or life-prolonging treatment.10,12

In sub-Saharan Africa, hospital-based death (28.7% in Ethiopia and 51% in Zambia) was associated with younger age, female gender, higher education level, being married, and living in an urban area.13,14 In Mexico City, 54% of cancer patients dying at home were younger, had more formal education, and lived in counties with higher densities of hospital beds.15

We are not aware of any published study regarding preferred versus actual place of death (POD) for terminally ill cancer patients in southern Africa. This study aimed to investigate factors associated with preferred and actual POD and with agreement between the two from data collected prospectively in a cohort of patients with end-stage cancer in Soweto, Johannesburg, South Africa.

Methods

Setting

The study was conducted at the Gauteng Centre for Palliative Care (GCPC) at Chris Hani Baragwanath Academic Hospital (CHBAH) in Soweto, Johannesburg in South Africa. CHBAH is a tertiary level public sector hospital serving a predominantly black urban population. Being one of the few public sector facilities of its kind in South Africa, GCPC has provided palliative care services to CHBAH inpatients, clinic-based outpatients, and home-based patients in Soweto since 2007.

Study Design and Participants

We conducted a prospective cohort study of the experiences of patients with incurable cancers receiving palliative care (National Cancer Institute grant no. R01 CA192627). Patients diagnosed with breast, gastrointestinal, soft tissue sarcoma, or melanoma, who had been presented to the combined surgical oncology meeting at CHBAH; and patients diagnosed with lung cancer referred from the pulmonology unit, were considered eligible if assessed as having a life expectancy of less than six months, were aged ≥18 years, had a primary caregiver willing to participate in the study, and were considered by the study staff to be competent to complete the initial interview. After providing informed consent, both patients and caregivers were interviewed in person by trained palliative care nurses from GCPC. The same interviewers conducted the postmortem interviews with the patient-designated caregivers. All patients, whether consenting or not, were offered palliative care services.

Data Collection and Measurement Tools

Collected information included patient age, gender, self-identified race, marital status, education, employment status, home ownership, household amenities, and home appliances, as well as clinical factors including cancer diagnosis, comorbidities, and treatments. Socioeconomic status was derived from the Demographics and Health Surveys Program’s wealth index as previously described.9,16 Records of home ownership, source of electricity, type of water access, toilet type, vehicle ownership, and possession of household items such as fridges, microwaves, washing machines, land phones, cell phones, and beds were used. We conducted principal component analysis and patients were grouped into quintiles using the first principal component. The items with the highest first component eigenvalues were possession of a refrigerator (0.31), indoor flush toilet (0.30), microwave (0.28), washing machine (0.26), and commercial electricity (0.26). At the baseline interview and at each visit to the GCPC clinic, study nurses assessed palliative care needs using the African Palliative Care Association (APCA) Palliative Outcome Scale, a validated tool for measuring physical and emotional symptom burden in Africa.17 Items assessed included the following: pain and other symptoms, patient worry, assistance and advice, ability to share feelings, and feeling at peace and that life is worthwhile. The scores of the six-point APCA scale were individually summed for three categories: physical and psychosocial (0–15), interpersonal (0–10), and existential (0–10).18

Patient interviews explored choices for care at end of life, including preferred POD with the question: “If you were dying or at the end of your life, where would you most want to be?” The possible responses were as follows: home, hospital, nursing home (step-down facility), inpatient hospice, or “other.” If the response was “other,” the patient was asked to explain what was meant by other. Illness understanding was assessed using the question “How would you describe your current health status?” previously used in a USA Coping with Cancer Study.19 Responses included “relatively healthy,” “relatively healthy but terminally ill,” “seriously ill but not terminally ill,” and “seriously ill and terminally ill.” Postmortem interviews with the caregivers covered the circumstances of the patient’s death, including location of death for which the following were possible answers: “Hospital,” “hospice,” “home,” “nursing home (step down),” or “other.” “Other” was clarified by the interviewer. This was followed by the question: “Were family or friends present? and “Did the patient want family and/or friends there?” Possible answers to this question included “yes,” “no,” or “unsure,” Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at the University of the Witwatersrand.20

Data Analysis

Data for preferred POD and actual POD were extracted from the GCPC’s REDCap database. Dependent variables analyzed were preferred POD, actual POD, and their agreement. Independent variables were sociodemographic factors (patient’s age, gender, marital status, self-reported race, level of education, past and present employment status, distance from CHBAH, home ownership, and socioeconomic status), clinical factors (site of primary tumor, duration from formal diagnosis to death, HIV status, and other comorbidities), ECOG performance status, pain medications, whether the patient wanted family and/or friends present at time of death, patient illness understanding, and baseline and last APCA scores before death.

We compared patients who died at home to those who died in the hospital/facility with respect to the independent variables. Descriptive statistics (frequencies and percentages) were reported for categorical variables and compared using Pearson’s χ2 test and Fisher’s exact test where appropriate; means and medians were reported for continuous variables and compared using t-tests and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests.

We used binary logistic regression to determine which factors were independently associated with preferred and actual home death. All variables that were significant at P < 0.1 on univariate analysis were evaluated in the multivariate analysis and nonsignificant factors were dropped with stepwise backward regression. A two-sided P-value of <0.05 was considered significant throughout. We determined the extent of agreement (congruence) between preferred POD and actual POD using Cohen’s kappa coefficient (k).21 We used Stata version 15 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) for our analyses.22

Results

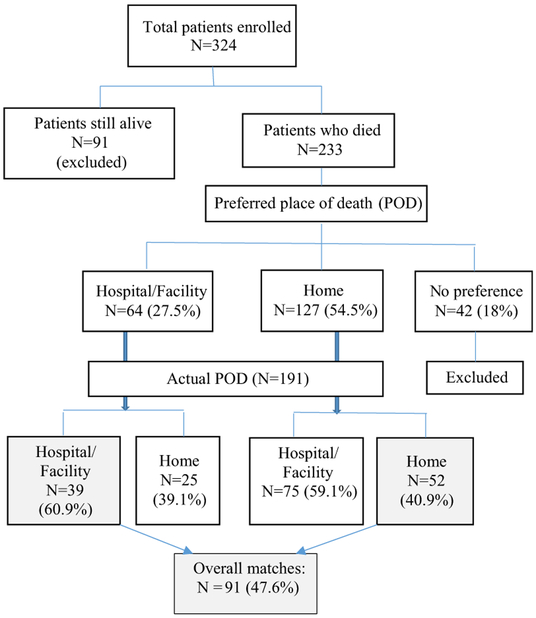

Between May 2016 and February 2018, 324 patients and their caregivers were enrolled; 233 patients died during follow-up; each of the patients had a caregiver who was interviewed subsequently. Of the 233 patients, 191 (82.0%) had expressed a preference regarding POD: 127 (54.5%) preferred home and 64 (27.5%) preferred a hospital/facility.

The mean age of the 191 patients at enrollment was 57.6 years (SD 13.26); 106 (55.5%) were women; 172 (89.5%) self-identified as black; 77 (40.3%) were married or had a partner; and 163 (85.3%) were unemployed (Table 1). The most common cancers among these patients were lung (31.4%), breast (28.3%) and GI/hepatobiliary (38.7%). At enrollment, 94 (49.2%) patients had other noncommunicable diseases (hypertension, other cardiac illnesses, stroke, asthma/COPD, diabetes), 50 (26.9%) were HIV positive, and 23 (12.0%) had tuberculosis. In interviews after the patients died, their caregivers reported that 77 patients (40.3%) died at home and 114 (59.7%) died in a health care facility (110 in a hospital, three in hospice, and one in a care facility) (Table 2).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics of Patients With Advanced Cancer Attending the Palliative Care Unit of CHBAH

| Patient Characteristics | N = 191 (%) |

|---|---|

| Age in yrs (mean ± SD) | 57.64 ± 13.26 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 85 (44.50) |

| Female | 106 (55.50) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 62 (32.50) |

| Married/partner | 77 (40.30) |

| Divorced/separated | 13 (6.80) |

| Widowed | 39 (20.40) |

| Race | |

| Black | 171 (89.50) |

| Colored | 15 (7.90) |

| Indian | 1 (0.50) |

| White | 4 (2.10) |

| Highest level of education | |

| No education/primary | 66 (34.60) |

| Secondary education and above | 125 (65.40) |

| Employment status | |

| Unemployed | 163 (85.30) |

| Employed (including self-employed, informal trading) | 28 (14.70) |

| Site of primary tumor Breast | |

| Breast | 54 (28.30) |

| Lung | 60 (31.40) |

| Gastrointestinal Tract and hepatobiliary | 74 (38.70) |

| Sarcoma and melanoma | 3 (1.60) |

| Distance from CHBAH in Km, median (IQR) | 10.34 (6.07–20.65) |

| Comorbidities | |

| Diabetes | 14 (7.30) |

| Hypertension | 65 (34.00) |

| Cardiac disease/stroke | 5 (2.60) |

| Asthma/COPD | 10 (5.20) |

| Tuberculosis | 23 (12.00) |

| HIV positive | 50 (26.20) |

| Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group at baseline (by interviewer) | |

| 0–2 | 138 (72.30) |

| 3–4 | 53 (27.70) |

| Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group at baseline (by caregiver) | |

| 0–2 | 114 (59.70) |

| 3–4 | 77 (40.30) |

| Pain medicationsa | |

| Step 1 (nonopioids, paracetamol) | 25 (13.70) |

| Step 2 (tramadol, codeine phosphate) | 64 (35.20) |

| Step 3 (morphine) | 93 (51.10) |

| Missing data | 9 |

| Patient’s illness understanding | |

| Relatively healthy | 61 (31.94) |

| Relatively healthy but terminally ill | 4 (2.09) |

| Seriously ill but not terminally ill | 115 (60.21) |

| Seriously and terminally ill | 11 (5.76) |

| Time between diagnosis of cancer and deatha | |

| Less than 3 months | 76 (40.00) |

| Three to 6 months | 41 (21.58) |

| More than 6 months | 73 (38.42) |

| Time between enrollment and death, days, median (IQR) | 59 (19–121) |

| Time between enrollment and death (months) a | |

| Less than 1 month | 69 (36.32) |

| One to less than 3 months | 53 (27.89) |

| Three to less than 6 months | 30 (15.79) |

| Six months or more | 38 (20.00) |

| Last APCA POS factor score, median (IQR), mean | |

| Physical and psychosocial (0–15), 0 (best), 15 (worst) | 7.00 (4.0–10.0), 6.77 |

| Interpersonal (0–10), 0 (worst), 10 (best) | 8.00 (7.0–10.0), 7.93 |

| Existential (0–10), 0 (worst), 10 (best) | 8.0 (5.0–10.0), 7.00 |

| Preferred place of death | |

| Hospital, or other institution (hospice, nursing home) | 64 (33.51) |

| Home | 127 (66.49) |

CHBAH = Chris Hani Baragwanath Academic Hospital; IQR = interquartile range; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; APCA POS = African Palliative Care Association Palliative Outcome Scale.

Missing values for the variables are as follows: pain medications (n = 9), time between diagnosis of cancer and death (n = 1), time between enrollment and death (n = 1).

Table 2.

Patients’ Characteristics and Associations With Actual and Preferred Home Death

| Actual Place of Deat |

Preferred Place of Death |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital/Facility N = 114 | Home N = 77 | Unadjusted Analysis | Hospital/Facility N = 64 | Home N = 127 | Unadjusted Analysis | |

| Characteristics | Mean ± SD | OR (95% CI)a | Mean ± SD | OR (95% CI)d | ||

| Age in yrs | 55.88 (12.97) | 60.24 (13.3) | 1.03 (1.00–1.05)e | 57.58 (12.85) | 57.67 (13.50) | 1.00 (0.98–1.02) |

|

N (%) |

N (%) |

|||||

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 46 (40.4) | 39 (50.6) | 1.52 (0.85–2.72) | 24 (37.5) | 61 (48.0) | 1.54 (0.83–2.85) |

| Female | 68 (59.6) | 38 (49.4) | 1 (Ref) | 40 (62.5) | 66 (52.0) | 1 (Ref) |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married/ partner | 48 (42.1) | 29 (37.7) | 1 (Ref) | 26 (40.6) | 51 (40.2) | 1 (Ref) |

| Not married | 66 (57.9) | 48 (62.3) | 1.20 (0.67–2.17) | 38 (59.4) | 76 (59.8) | 1.02 (0.55–1.88) |

| Highest level of education | ||||||

| No formal education/primary | 34 (29.8) | 32 (41.6) | 1.67 (0.91–3.07) | 21 (32.8) | 45 (35.4) | 1.12 (0.59–2.12) |

| Secondary education and above | 80 (70.2) | 45 (58.4) | 1 (Ref) | 43 (67.2) | 82 (64.6) | 1 (Ref) |

| Wealth quintileb | ||||||

| Quintile 1 (poorest) | 31 (27.2) | 11 (14.3) | 1 (Ref)e | 16 (25.0) | 26 (20.5) | 1 (Ref) |

| Quintile 2 | 16 (14.0) | 18 (23.4) | 3.17 (1.21–8.30) | 10 (15.6) | 24 (18.9) | 1.48 (0.56–3.88) |

| Quintile 3 | 21 (18.4) | 16 (20.8) | 2.14 (0.83–5.53) | 12 (18.8) | 25 (19.7) | 1.28 (0.51–3.24) |

| Quintile 4 | 20 (17.5) | 22 (28.6) | 3.10 (1.24–7.75) | 15 (23.4) | 27 (21.3) | 1.11 (0.46–2.69) |

| Quintile 5 (wealthiest) | 26 (22.8) | 10 (13.0) | 1.08 (0.40–2.95) | 11 (17.2) | 25 (19.7) | 1.40 (0.54–3.59) |

| Site of primary tumor | ||||||

| Breast | 36 (31.6) | 18 (23.4) | 1 (Ref) | 25 (39.1) | 29 (22.9) | 1 (Ref) |

| Lung | 36 (31.6) | 24 (31.2) | 1.33 (0.62–2.87) | 16 (25.0) | 44 (34.6) | 2.37 (1.08–5.18)e |

| GIT and hepatobiliary | 39 (34.2) | 35 (45.5) | 1.79 (0.87–3.71) | 21 (32.8) | 53 (41.7) | 2.18 (1.04–4.54) |

| Sarcoma and melanoma | 3 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | n/a | 2 (3.1) | 1 (0.8) | 0.43 (0.04–5.04) |

| Distance from CHBAH in Km, median (IQR) | 10.34 (6.07–21.10) | 9.83 (6.23–16.75) | 0.89 (0.97–1.01) | 12.69 (6.50–23.51) | 9.84 (5.85–16.43) | 0.99 (0.98–1.01) |

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| Other NCDs | 47 (41.2) | 26 (33.8) | 0.73 (0.40–1.33) | 23 (35.9) | 50 (39.4) | 1.16 (0.62–2.16) |

| Tuberculosis | 16 (14.0) | 7 (9.1) | 0.61 (0.24–1.57) | 7 (10.9) | 16 (12.6) | 1.17 (0.46–3.01) |

| HIV infection | 32 (28.1) | 18 (23.4) | 0.78 (0.40–1.52) | 17 (26.6) | 33 (26.0) | 0.97 (0.49–1.92) |

| Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group at baseline (by interviewer) | ||||||

| 0–2 | 82 (71.9) | 56 (72.7) | 1.04 (0.54–1.99) | 38 (59.4) | 100 (78.7) | 2.53 (1.32–4.88)e |

| 3–4 | 32 (28.1) | 21 (27.3) | 1 (Ref) | 26 (40.6) | 27 (21.3) | 1 (Ref) |

| Pain medicationsc | ||||||

| Step 1 and 2 | 57 (53.3) | 32 (42.7) | 1 (Ref) | 32 (52.5) | 57 (47.1) | 1 (Ref) |

| Step 3 | 50 (46.7) | 43 (57.3) | 1.53 (0.85–2.78) | 29 (47.5) | 64 (52.9) | 1.24 (0.67–2.29) |

| Missing data | 7 | 2 | 3 | 6 | ||

| Patient’s illness understanding | ||||||

| Relatively healthy | 41 (36.0) | 20 (26.0) | 1 (Ref) | 13 (20.3) | 48 (37.8) | 1 (Ref)e |

| Relatively healthy but terminally ill | 2 (1.7) | 2 (2.6) | 2.05 (0.27–15.63) | 2 (3.1) | 2 (1.6) | 0.27 (0.03–2.11) |

| Seriously ill but not terminally ill | 65 (57.0) | 50 (64.9) | 1.58 (0.82–3.01) | 42 (65.7) | 73 (57.5) | 0.47 (0.23–0.97) |

| Seriously and terminally ill | 6 (5.3) | 5 (6.5) | 1.71 (0.46–6.28) | 7 (10.9) | 4 (3.2) | 0.15 (0.04–0.61) |

| Did the patient want family and/or friends present at death? | ||||||

| Yes | 64 (56.1) | 69 (89.6) | 6.73 (2.97–15.30)f | 39 (60.9) | 94 (74.0) | 1.83 (0.96–3.46) |

| No or not sure | 50 (43.9) | 8 (10.4) | 1 (Ref) | 25 (39.1) | 33 (26.0) | 1 (Ref) |

| Preferred place of death | ||||||

| Hospital | 39 (34.2) | 25 (32.5) | 1 (Ref) | N/A | ||

| Home | 75 (65.8) | 52 (67.5) | 1.08 (0.59–2.0) | N/A | ||

Significant values represented in bold type.

CHBAH = Chris Hani Baragwanath Academic Hospital; IQR = interquartile range; NCD = noncommunicable disease.

OR for home death.

Wealth quintile is a proxy for socioeconomic status.

Step 1 = paracetamol, Step 2 = tramadol hydrochloride or codeine phosphate, Step 3 = morphine (oral formulations).hydrochloride or codeine phosphate, Step 3 = morphine (oral formulations).

OR for preferred home death.

P < 0.05.

P < 0.001.

The mean age of the 127 patients who had preferred to die at home was 57.7 years (SD 13.5); 66 (52.0%) were women; 51 (40.2%) were married or had a partner; 82 (64.6%) had a secondary level of education or higher; and 45 (35.4%) had primary level education or less.

The mean age of 77 patients who died at home was 60.2 years (SD 13.3); 38 (49.4%) were women; 29 (37.7%) were married or had a partner; 45 (58.4%) had a secondary level of education or higher; and 32 (41.6%) had primary level education or less. Fifty-two (67.5%) patients had expressed a preference to die at home and 69 patients (89.6%) wanted family and friends to be present.

Patients’ preference for death at home was associated with an ECOG performance status of 0–2 (odds ratio [OR] 2.53, 95% CI 1.32–4.88; P = 0.01) or having lung cancer or breast cancer (OR 2.18, 95% CI 1.04–4.54; OR 2.37, 95% CI 1.08—5.18, respectively; P = 0.05), whereas the patients who perceived themselves to be seriously ill were less likely to prefer death at home (OR 0.47, 95% CI 0.23–0.97; P = 0.02) (Table 2). Dying at home was associated with increasing age (OR 1.03, 95% CI 1.00–1.05; P = 0.02). Patients whose caregivers reported that they had wanted family and/or friends to be present were more likely to die at home than those who did not or were not sure (OR 6.73, 95% CI 2.97–15.30; P < 0.001). Preference for death at home was not associated with actual death at home (Table 2).

In a multivariate logistic regression model controlling for site of primary cancer and preferred POD, dying at home was marginally associated with increasing age (OR 1.04, 95% CI 1.01–1.06; P = 0.01). Patients who wanted family and friends present were more likely to die at home (OR 7.83, 95% CI: 3.27–18.71). Wealth quintile and preferred POD were not associated with home death (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariate Logistic Regression Model of the Factors Associated With Death at Home

| Univariate Analysis |

Multivariate Analysis |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | P-Value |

| Age in yrs | 1.03 (1.00–1.05) | 1.04 (1.01–1.06) | 0.01 |

| Site of primary tumor | |||

| Breast | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | |

| Lung | 1.33 (0.62–2.87) | 0.90 (0.38–2.13) | 0.53 |

| GIT and hepatobiliary | 1.79 (0.87–3.71) | 1.69 (0.74–3.88) | 0.21 |

| Sarcoma and melanoma | N/A | N/A | |

| Did the patient want family and/or friends present at death? | |||

| Yes | 5.60 (1.99–15.75) | 7.83 (3.27–18.71) | <0.01 |

| No or not sure | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | |

| Preferred place of death | |||

| Hospital/facility | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | 0.41 |

| Home | 1.08 (0.59–2.0) | 0.74 (0.36–1.51) |

OR = odds ratio; N/A = not applicable.

Only variables with P < 0.1 on univariate analysis are represented in this table, adjusting for cancer type and patient’s preferred place of death. Wealth quintile was not included in the final model because it was not significant in the multivariate analysis.

Overall, 91 (47.6%) patients achieved their preference for POD. The kappa value of congruence (kappa = 0.016, 95% CI = −0.107 to 0.139) indicated poor to slight agreement between the preferred and actual place death. Of 91 patients, 52 died at home and 39 died in hospital (Fig. 1, Table 4). In a pooled analysis of determinants of congruence of POD (Table 5), using a multivariate logistic regression model controlling for site of primary cancer, the factors associated with congruence were increasing age (OR: 1.03, 95% CI: 1.00–1.05), and use of morphine (those on Step 3 pain medications were more likely to achieve their preference for POD [OR: 1.87, 95% CI: 1.04–3.36], whereas those wanting to die at home were less likely to achieve congruence [OR: 0.44, 95% CI: 0.24–0.82]).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart indicating analysis of preferred and actual place of death.

Table 4.

Determinants of Death in the Preferred Place

| Preferred Place of Death (Hospital) |

Preferred Place of Death (Home) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Died in Hospital (Preferred) |

Died at Home (Not Preferred) |

Died in Hospital (Not Preferred) |

Died at Home (Preferred) |

|||||

| Characteristics | N = 39 (%) | N = 25 (%) | OR (95% CI) | P-Value | N = 75 (%) | N = 52 (%) | OR (95% CI) | P-Value |

| Age in yrs, mean ± SD | 56.67 ± 12.68 | 59.00 ± 13.24 | 0.99 (0.95–1.03) | 0.48b | 55.47 ± 13.19 | 60.85 ± 13.45 | 1.03 (1.00–1.06) | 0.03b |

| Highest level ofeducation | ||||||||

| No formal education/primary | 12 (30.8) | 9 (36.0) | 0.79 (0.27–2.29) | 0.66 | 22 (29.3) | 23 (44.2) | 1.91 (0.91–4.00) | 0.084 |

| Secondary educationand above | 27 (69.2) | 16 (64.0) | 1 (Ref) | 53 (70.7) | 29 (55.8) | 1 (Ref) | ||

| Distance from CHBAH in Km, median (IQR) | 9.06 (6.38–19.19) | 16.14 (7.34–25.44) | 1.04 (1.00–1.09) | 0.04c | 8.80 (5.85–16.43) | 10.39 (5.96–16.44) | 1.00 (0.98–1.12) | 0.33c |

| Site of primary tumor | ||||||||

| Breast | 16 (41.0) | 9 (36.0) | 1 (Ref) | 0.37 | 20 (26.7) | 9 (17.3) | 1 (Ref) | 0.425 |

| Lung | 11 (28.2) | 5 (20.0) | 1.24 (0.32–4.71) | 25 (33.3) | 19 (36.5) | 1.69 (0.63–4.53) | ||

| GIT and hepatobiliary | 10 (25.6) | 11 (44.0) | 0.51 (0.16–1.67) | 29 (38.7) | 24 (46.2) | 1.84 (0.71–4.78) | ||

| Sarcoma and melanoma | 2 (5.1) | 0 (0.0) | N/A | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | N/A | ||

| Patient’s illness understanding | ||||||||

| Relatively healthy | 10 (25.6) | 3 (12.0) | 1 (Ref) | 0.18a | 31 (41.3) | 17 (32.7) | 1 (Ref) | 0.07a |

| Relatively healthy but terminally ill | 1 (2.6) | 1 (4.0) | 0.30 (0.01–6.38) | 1 (1.3) | 1 (1.9) | 1.82 (0.11–31.03) | ||

| Seriously ill but not terminally ill | 22 (56.4) | 20 (80.0) | 0.33 (0.08–1.37) | 43 (57.4) | 30 (57.7) | 1.27 (0.60–2.70) | ||

| Seriously and terminally ill | 6 (15.4) | 1 (4.0) | 1.80 (0.15–21.48) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (7.7) | N/A | ||

| Pain medications | ||||||||

| Step 1 and 2 | 18 (48.6) | 14 (58.3) | 1 (Ref) | 0.46 | 39 (55.7) | 18 (35.3) | 1 (Ref) | 0.03a |

| Step 3 (morphine) | 19 (51.4) | 10 (41.7) | 1.48 (0.52–4.17) | 31 (44.3) | 33 (64.7) | 2.31 (1.10–4.85) | ||

| Did the patient want family and/or friends there? | ||||||||

| Yes | 17 (43.6) | 22 (88.0) | 0.11 (0.03–0.41) | 0.01 | 47 (62.7) | 47 (90.4) | 5.6 (1.99–15.75) | <0.01 |

| No and not sure | 22f (56.4) | 3g (12.0) | 1 (Ref) | 28d (37.3) | 5e (9.6) | 1 (Ref) | ||

| Time between enrollment and death, days, median (IQR) | 50 (20–189) | 57 (27–102) | 1.00 (0.99–1.00) | 0.319 | 15 (17–109) | 70 (23–130) | 1.00 (0.99–1.00) | 0.523 |

CHBAH = Chris Hani Baragwanath Academic Hospital; IQR = interquartile range; N/A = not applicable (cell empty); NCD = noncommunicable disease—hypertension, diabetes, cardiac diseases/stroke, asthma/chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Variables with P < 0.05 are shown in bold face.

Fisher’s exact test.

Student’s t-test.

Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

23 of the 28 were not sure

4 of the 5 were not sure

17 of the 22 were not sure

All 3 were not sure.

Table 5.

Multivariate Logistic Regression Model of the Factors Associated With Congruence Between Preferred and Actual Place of Death

| Characteristics | Univariate Analysis OR (95% CI) | Multivariate Analysis OR (95% CI) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in yrs | 1.02 (1.00–1.04) | 1.03 (1.00–1.05) | 0.037 |

| Site of primary tumor | |||

| Breast | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | |

| Lung | 1.16 (0.56–2.42) | 1.12 (0.49–2.54) | 0.787 |

| GIT and hepatobiliary | 0.99 (0.49–1.99) | 1.08 (0.50–2.34) | 0.838 |

| Sarcoma and melanoma | 2.32 (0.20–27.1) | 0.93 (0.05–17.85) | 0.963 |

| Pain medications | |||

| Step 1 and 2 | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | 0.019 |

| Step 3 (morphine) | 1.87 (1.04–3.36) | 2.14 (1.13–4.04) | |

| Preferred place of death | |||

| Hospital/facility | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | 0.012 |

| Home | 0.44 (0.24–0.82) | 0.42 (0.22–0.83) |

Significant values represented in bold type.

Only variables significant on multivariate analysis at P < 0.05 are represented in this table, adjusting for cancer type.

Patients who preferred to die and actually died in hospital were less likely than others (according to the caregiver) to want family or friends to be present (OR 0.14, 95% CI 0.03–0.54, P = 0.001). Patients who preferred to die in hospital but died at home lived farther from CHBAH than those who died in hospital (OR 1.04, 95% CI 1.00–1.09, P = 0.04). Patients who preferred to die and actually died at home were older than others (OR 1.03, 95% CI 1.00–1.06, P = 0.03), were more likely to be taking morphine (oral formulation) for pain (OR 2.31, 95% CI 1.10–4.85, P = 0.03), and were more likely to want family or friends to be present (P = 0.001) (Table 4).

Discussion

In this study, most cancer patients preferred dying at home to dying in the hospital or other facility, but most died in hospital. Patients who died at home were older and more likely to want to die among family or friends.

Fewer of our patients died at home than those in a study from Mexico City (40.3% vs. 54%).15 However, the percentage of hospital deaths we observed was similar to that reported for all adult deaths in a Zambian postmortem survey (58.8% vs. 51%), but higher than that reported in an Ethiopian study of death certificates (28.7%), possibly because health care facilities are more accessible in Johannesburg and in Zambia.13,14 In Zambia, 67% of deaths due to cancer occurred within a health care facility, similar to our findings. Younger people were more likely to die in hospital in Ethiopia and Mexico City, whereas we found that older people were more likely to die at home. No association between marital status and POD was found in our study or in studies from Ethiopia, Zambia, and Mexico City. However, in many HIC studies, patients who were more educated or married were more likely than others to die at home.11,23 Other factors influencing home death in HICs included patient and caregiver preference, living with relatives and having extended family support, as well as access to palliative care services. Our study found no association with patient preference or living with relatives, although wanting family present was a significant factor for dying at home. All our patients were enrolled in our palliative care program; however, not all patients received regular palliative care home visits due to resource constraints. Our recent study revealed significant challenges experienced by caregivers taking care of patients at home, possibly indicating a lack of adequate support through home-based services,9 which may have led to readmission to hospital.

In our present study, 47.6% of patients’ actual POD matched their preferred POD, 27.2% for home death, and 20.4% for hospital death. Overall, patients achieving their preferred POD were more likely to be older and to be taking morphine for pain; however, those preferring to die at home were less likely to do so. Congruence for home death was more likely for patients who preferred to have family present. Congruence for hospital death was less likely for patients who lived further from CHBAH or who wanted family present.

In Connecticut, 29.9% of cancer patients died in their preferred setting. Home death was preferred by 87.4% of patients, whereas 12.7% preferred death in a hospital or other facility. Only 22.5% who preferred home death died at home, whereas three patients who preferred to die in hospital actually died there. Factors positively affecting dying in a preferred setting in Connecticut were home hospice services and a perception that family could help them achieve their POD.24 Rehospitalization negatively affected dying in a preferred setting. In a European study (Spain, Italy, Netherlands, and Belgium), palliative care provision by GPs was the only significant factor associated with death in the preferred setting.12

Our study has a number of strengths: its prospective longitudinal design, relatively large sample size, and complete follow-up with remarkably little missing data. However, our data come from a single center serving urban public sector patients; our findings therefore may not be generalizable to other populations in South Africa. We did not collect data on caregivers’ circumstances that might have affected actual POD or on caregivers’ preferences for place of care or POD for the patient. We also did not consider the number of palliative care consultations each patient received.

Sociodemographic and cultural factors associated with POD may not be amenable to intervention by health care providers. However, there are some factors that may be modifiable with timely palliative care provision. Patients who were taking morphine for pain were more likely to die in their preferred place, especially if at home. Although consumption of morphine-equivalent strong opioid analgesics per cancer death is considered by the WHO to be an indicator of palliative care service provision,25 an association between morphine usage and palliative care service provision cannot be assumed in this study owing to insufficient data.

Where caregivers indicated that patients would prefer to have family or friends present, patients were more likely to die at home, if preferred, but where caregivers were unsure of the patient’s preference, patients were more likely to die in hospital even if they preferred to die at home. While the patients were not asked directly by the interviewer regarding who they would like to be present, and the caregivers were not asked if they had asked the patients themselves, which is a limitation in this study, it is of concern that 47 (24.6%) of the 191 caregivers were unsure, which may indicate a lack of communication about end-of-life care, between the patient and the caregiver. Such communication would be complicated by the lack of acknowledgment of the terminal stage of the illness by the patient. Most of our patients did not acknowledge being terminally ill. Patients who considered themselves relatively well were less likely to die at home if preferred. A previous study from our center reported that most patients (76.9%) would not want to know how long they had to live even if their doctors knew.26 This finding highlights a further challenge to effective and appropriate communication about end-of-life preferences between health care providers, patients, and their families and may also affect illness understanding. Inadequate communication and subsequent inappropriate expectations could add to the emotional and physical burden on caregivers trying to cope with limited resources and result in hospitalization of the patient. A lack of illness understanding and continued hope for cure may also have driven some patients, especially younger ones, to return to hospital for further treatment and ultimately to die there.

Conclusion

Enabling patients to die in their preferred place is considered an indicator of effective palliative care provision.1 From our study, we observed that most patients did not die in their preferred setting and that while most preferred to die at home, most were dying in hospital. Patients who received morphine for pain were more likely to die where they preferred, and patients whose family caregivers knew that they wanted family present at the end of life were more likely to die at home.

Health care practitioners should be urged to discuss with terminally ill patients, their goals of care, and end-of-life preferences including preferred POD and should encourage such communication between patients and their families as well as discussing practical options for meeting their needs.1,27 However, given our patients’ responses to discussing dying with their doctors, more research is required to understand and implement best practice in facilitating culturally appropriate end-of-life communication.

Challenges to providing care at home by caregivers may contribute to terminally ill patients choosing to die in hospital or not dying at home if they preferred to. Adequate palliative care services provide support for patients and families, both practically and emotionally. Accessible palliative care may lead to more patients dying in their preferred place, especially if at home. The association between morphine usage and achieving preferred POD in our setting may indicate better access to palliative care for those patients; however, this cannot be assumed and needs to be explored in more depth.

Our study has highlighted factors that are associated with terminally ill cancer patients treated at CHBAH, dying at home or in a preferred setting. Further research is required to improve our understanding of these associations to improve the services required to support patients and their families.

Disclosures and Acknowledgments

This work was supported by research grants from the National Cancer Institute awarded to Drs. Jacobson, Joffe, Neugut, and Ruff (R01 CA192627); Dr. Stephen Emerson and Dr. Ruff (P30 CA013696–41S4) (subaward no. 1 [GG010416–62]; Dr. Abate-Shen and Charmaine Blanchard (P30 CA013696–43S4) (subaward no. 3 [GG010416-BI]; and Dr. Prigerson (R35 CA197730); as well as the South African Medical Research Council/University of the Witwatersrand. Common Epithelial Cancer Research Centre (MRC/University of the Witwatersrand CECRC) awarded to Dr. Ruff and the Conquer Cancer Foundation Young Investigator Award to Dr. O’Neil.

Footnotes

Dr. Blanchard declares travel and accommodation fees from Janssen Pharmaceuticals and Dr. O’Neil declares personal fees from Ipsen outside the submitted work. Dr. Neugut receives consultant fees from Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, United Biosource Corp, Hospira, and Eisai and EHE International. All other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval: Ethics approval was obtained from the University of Witwatersrand, Human Research Ethics Committee (Medical) (Certificate M160118 dated 24/02/2016) and from Columbia University (IRB protocol number AAAQ7954 dated 17/03/2016) before the commencement of this study.

Contributor Information

Charmaine L. Blanchard, Centre for Palliative Care, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa ; Non Communicable Diseases Research Division, Wits Health Consortium, Johannesburg, South Africa.

Oluwatosin Ayeni, MRC Developmental Pathways to Health Research Unit, Department of Paediatrics, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg; Non Communicable Diseases Research Division, Wits Health Consortium, Johannesburg, South Africa.

Daniel S. O’Neil, Herbert Irving Comprehensive Cancer Center, College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University, New York, New York; Department of Medicine, College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University, New York, New York; Department of Epidemiology, Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University, New York, New York.

Holly G. Prigerson, Cornell Center for Research on End-of-Life Care Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, New York, USA.

Judith S. Jacobson, Herbert Irving Comprehensive Cancer Center, College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University, New York, New York; Department of Epidemiology, Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University, New York, New York.

Alfred I. Neugut, Herbert Irving Comprehensive Cancer Center, College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University, New York, New York; Department of Medicine, College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University, New York, New York; Department of Epidemiology, Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University, New York, New York.

Maureen Joffe, MRC Developmental Pathways to Health Research Unit, Department of Paediatrics, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg; Non Communicable Diseases Research Division, Wits Health Consortium, Johannesburg, South Africa.

Keletso Mmoledi, Chris Hani Baragwanath Academic Hospital Johannesburg; Centre for Palliative Care, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa; Non Communicable Diseases Research Division, Wits Health Consortium, Johannesburg, South Africa.

Mpho Ratshikana-Moloko, Chris Hani Baragwanath Academic Hospital, Johannesburg; Centre for Palliative Care, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa; Non Communicable Diseases Research Division, Wits Health Consortium, Johannesburg, South Africa.

Paul E. Sackstein, Department of Epidemiology, Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University, New York, New York.

Paul Ruff, Division of Medical Oncology, Department of Internal Medicine, University of the Witwatersrand Faculty of Health Sciences, Johannesburg; Non Communicable Diseases Research Division, Wits Health Consortium, Johannesburg, South Africa.

References

- 1.Oxenham D, Finucane A, Arnold E, Russell P. Delivering preference for place of death in a specialist palliative care setting. BMJ Qual Improv Rep 2013;2:u201375.w897 Available from 10.1136/bmjquality.u201375.w897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jeurkar N, Farrington S, Craig TR, et al. Which hospice patients with cancer are able to die in the setting of their choice? Results of a retrospective cohort study. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:2783–2787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beccaro M, Costantini M, Rossi PG, et al. Actual and preferred place of death of cancer patients. Results from the Italian survey of the dying of cancer (ISDOC). J Epidemiol Community Health 2006;60:412–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Priyadarshini Kulkarni PK, Anavkar V, Ghooi R. Preference of the place of death among people of Pune. Indian J Palliat Care 2014;20:101–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Downing J, Gomes B, Gikaara N, et al. Public preferences and priorities for end-of-life care in Kenya: a population-based street survey. BMC Palliat Care 2014;13:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Powell RA, Namisango E, Gikaara N, et al. Public priorities and preferences for end-of-life care in Namibia. J Pain Symptom Manage 2014;47:620–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gu X, Cheng W, Cheng M, Liu M, Zhang Z. The preference of place of death and its predictors among terminally ill patients with cancer and their caregivers in China. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2015;32:835–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gysels M, Pell C, Straus L, Pool R. End of life care in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review of the qualitative literature. BMC Palliat Care 2011;10:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Neil DS, Prigerson HG, Mmoledi K, et al. Informal caregiver challenges for advanced cancer patients during end-of-life care in Johannesburg, South Africa and distinctions based on place of death. J Pain Symptom Manage 2018;56:98–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gomes B, Higginson IJ. Factors influencing death at home in terminally ill patients with cancer: systematic review. BMJ 2006;332:515–521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alonso-Babarro A, Breura E, Varela-Cerdeira M, et al. Can this patient be discharged home? Factors associated with at-home death among patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:1159–1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Roo ML, Miccinesi G, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, et al. Actual and preferred place of death of home-dwelling patients in four European countries: making sense of quality indicators. PLoS One 2014;9:e93762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anteneh A, Araya T, Misganaw A. Factors associated with place of death in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Palliat Care 2013;12:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chisumpa VH, Odimegwu CO, De Wet N. Adult mortality in sub-Saharan Africa, Zambia: where do adults die? SSM Popul Health 2017;3:227–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cárdenas-Turanzas M, Carrillo MT, Tovalín-Ahumada H, Elting L. Factors associated with place of death of cancer patients in the Mexico City Metropolitan area. Support Care Cancer 2007;15:243–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rutstein SO, Johnson K. The DHS wealth index DHS Comparative Reports No 6. Calverton, Maryland, USA: ORC Macro, 2004. Available from https://dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-CR6-Comparative-Reports.cfm. Accessed July 6, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harding R, Selman L, Agupio G, et al. Validation of a core outcome measure for palliative care in Africa: the APCA African palliative Outcome scale. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2010;8:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harding R, Selman L, Simms VM, et al. How to analyze palliative care outcome data for patients in sub-Saharan Africa: an international, multicenter, factor analytic examination of the APCA African POS. J Pain Symptom Manage 2013;45:746–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Epstein AS, Prigerson HG, O’Reilly EM, Maciejewski PK. Discussions of life expectancy and changes in illness understanding in patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:2398–2403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) - a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bell CL, Somogyi-Zalud E, Masaki KH. Methodological review:measured and reported congruence between preferred and actual place of death. Palliat Me 2009;23: 482–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.StataCorp. Stata: Release 15 Statistical Software. College Station, TX: Stata Corp LLC, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen J, Pivodic L, Miccinesi G, et al. International study of the place of death of people with cancer: a population-level comparison of 14 countries across 4 continents using death certificate data. Br J Cancer 2015;113: 1397–1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tang ST, Mccorkle R. Determinants of congruence between the preferred and actual place of death for terminally ill cancer patients. J Palliat Care 2003;19:230–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Noncommunicable Diseases Global Monitoring Framework: Indicator Definitions and Specifications. World Health Organisation, 2014. Available from https://www.who.int/nmh/ncd-tools/indicators/GMF_Indicator_Definitions_Version_NOV2014.pdf. Accessed January 21, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shen MJ, Prigerson HG, Ratshikana-Moloko M, et al. Illness understanding and end-of-life care communication and preferences for patients with advanced cancer in South Africa. J Glob Oncol 2018:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Agar M, Currow C, Shelby-James TM, et al. Preference for place of care and place of death in palliative care: are these different questions? Palliat Me 2008;22:787–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]