Highlights

-

•

Necrotizing acute community-acquired pneumonia due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa are rare.

-

•

Second description of a septic shock secondary to a necrotizing CAP with bacteremia due to P. aeruginosa for which pulmonary origin was proven by bronchoalveolar lavage fluid on a patient who survived.

-

•

Anti-pseudomonal monotherapy may be may be a better option for older patients

-

•

Despite risk factors related to the host or to the bacteria, the evolution remains unpredictable.

Keywords: septic shock, community-acquired pneumonia, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, cavity lesion

Abstract

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is an uncommon cause of necrotizing acute community-acquired pneumonia (CAP). Only thirteen cases have been previously reported in the literature. In this article, we describe a case of previously healthy 80-year-old male patient, who presented in septic shock caused by necrotizing CAP. Despite inadequate empiric antimicrobial treatment, the patient survived and was able to return to his home after three weeks of hospitalization. To the best of our knowledge, this is the second case of septic shock secondary to P. aeruginosa necrotizing CAP and bacteremia, with optimal clinical outcome. We highlight the evolution of this pathology remains unpredictable, despite the factors related to the host and the bacterium.

Introduction

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a cause of nosocomial pneumonia in mechanically ventilated patients or with risk factors. Rarely, it can be responsible for acute community-acquired pneumonia (CAP). The risk factors identified for CAP are structural lung abnormalities, tobacco, alcohol, and contact with P. aeruginosa contaminated water. In this article, we describe a case of an 80-year-old male patient admitted to Intensive care unit (ICU), for septic shock due to P. aeruginosa necrotizing CAP and bacteremia.

Case presentation

An 80-year-old male presented to the emergency department at the end of January for three day history of severe right sided chest pain associated with dyspnea and fever. He denied any use of alcohol or tobacco. Past medical history consisted of hypertension, hypothyroidism, and calcified pleural plaques of unknown cause: he was a baker and had no past history of asbestos exposure. Six weeks prior to the presentation, he was diagnosed with autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA) during a short hospitalization and was getting treated with oral prednisone 70 mg daily. Recent laboratory work up consisted of negative HIV, hepatitis B and hepatitis C serologies. Antinuclear antibodies were positive with anti double-stranded DNA titer 1:360 but did not meet the criteria for lupus. Plasma protein electrophoresis was normal. A Positron emission tomography (PET) scan and a chest-abdomen-pelvis computed tomography (CT) were normal.

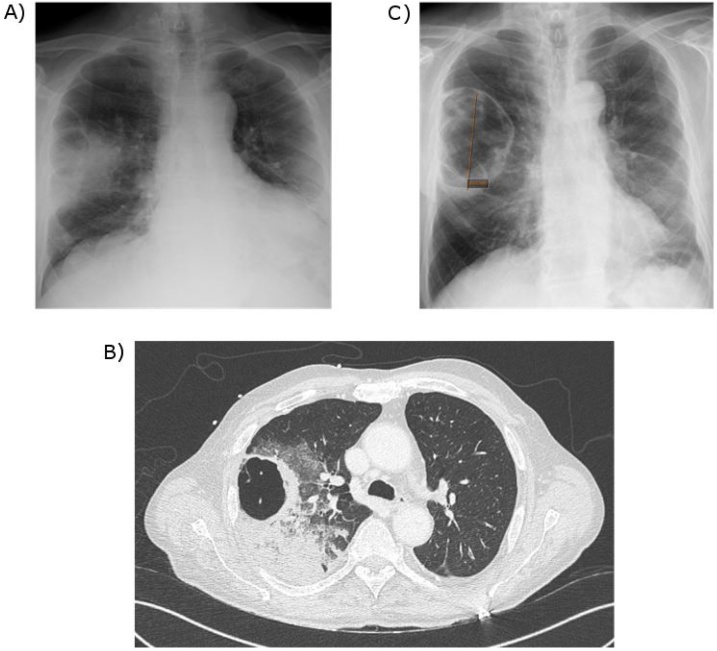

At arrival to the emergency department, the patient was dyspneic with respiratory rate of 27 breaths/min, heart rate of 93 beats/ min and fever of 39 °C. His lung auscultation was negative for crackles. The patient was hypotensive, with blood pressure of 80/60 mmHg, which did not respond to the initial intravenous fluids, thus required vasopressor support with norepinephrine. He was admitted to the ICU with the diagnosis of sepsis shock. The laboratory tests showed leukocytosis with white blood cell count of 27,100/mm3, hemoglobin level of 14.5 g/dL and platelet count of 187,000/mm3. The arterial blood gas collected on two liters of oxygen showed pH of 7.48, PaO2 of 62 mmHg, and PaCO2 of 35 mmHg. C-reactive protein (CRP) was elevated at 130 mg/L. The patient had acute kidney injury with creatinine at 1.386 mg/dL (baseline: 0.795 mg/dL). Lactic acid was elevated to 31.53 mg/dL. Procalcitonin (PCT) was increased to 14.6 ng/mL. Blood cultures were obtained. Pneumococcal and Legionella urine antigens were negative. The anteroposterior (AP) chest x-ray (Fig. 1A) showed pulmonary consolidation in the right upper lobe (RUL) with a cavity. Chest, abdomen and pelvic CT (Fig. 1B) showed RUL consolidation associated with septated cavitation. Empiric antimicrobial therapy was started with intravenous (IV) cefotaxime 2 g x 3 daily and IV levofloxacin 500 mg twice daily. On the second day of hospitalization, blood cultures became positive for pan-sensitive P. aeruginosa. The antimicrobials were changed to IV cefepime 2 g over eight hours twice daily for three weeks.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of chest imaging:

A) Anteroposterior Chest X-ray at admission: infiltration of the right upper lobe associated with a cavity.

B) Computed tomography (CT) of thorax without contrast at admission: consolidation associated with cavitation.

C) Anteroposterior Chest X-ray after 14 days of antibiotic therapy: significant decrease of pulmonary consolidation and presence of a residual cavity of 10 cm diameter.

The patient underwent bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) with positive culture of P. aeruginosa at the concentration of 105/mL. The respiratory strain susceptibility pattern was identical to the blood culture. The acid-fast bacilli stain was negative. The patient's clinical condition improved on IV cefepime. The vasopressor was rapidly weaned on the second day and oxygen therapy was stopped on the fourth day of hospitalization. He was transferred out of the ICU to the pulmonology floor and was later discharged from the hospital after 3 weeks of IV cefepime. Repeat chest x-ray at 2 weeks (Fig. 1C) showed dramatic decrease of the pulmonary consolidation with residual 10 cm cavity.

Discussion

Necrotizing CAP due to P. aeruginosa is rare. In the literature, we found 13 cases of necrotizing CAP due to P. aeruginosa associated with cavitation. Table 1 summarizes the 11 most recent cases [[1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10]]. The main risk factors for necrotizing CAP due to P. aeruginosa are: lung structural abnormalities (including cystic fibrosis, emphysema, bronchial dilatation, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), immunocompromised condition (including neoplasia, neutropenia, prolonged antibacterial therapy, immunosuppression), and exposure to contaminated liquids (including hot tub, spa, humidifier) [1,2]. This patient had none of these risk factors prior to the hospitalization during he was diagnosed AIHA, however he had been treated with prednisone 70 mg daily for six weeks prior to presentation with necrotizing CAP. The PET scan and the chest-abdomen-pelvis CT during his hospitalization on hematology floor did not reflect abnormality except pleural plaques.

Table 1.

Literature review of different necrotizing CAP cases associated with cavitation.

| Reference | Age (in years) | Sex* | Risk factors | Pneumonia location* | Positive samples | Treatment and outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kunimasa et al [1] | 25 | M | Hot tub | RUL | Sputum | meropenem + levofloxacin: Survival |

| Crnich et al [2] | 40 | M | Hot tub, Tobacco |

RUL | Sputum Hot tub water |

ciprofloxacin : Survival |

| Sakamoto et al [3] | 47 | M | Corticosteroids Tobacco |

LUL | Sputum Blood |

ampicillin/sulbactam: Death |

| Gharabaghi et al [4] | 26 | M | None | LUL | Sputum Lung biopsy |

ciprofloxacin : Survival |

| Vikram et al [5] | 62 54 |

M M |

Tobacco, malignancy Tobacco, alcohol |

RUL RUL |

Sputum | ciprofloxacin : Survival |

| Okamoto et al [6] | 39 | F | Tobacco Alcohol |

RUL | Sputum Pleural fluid Blood |

plasmapheresis + meropenem + ciprofloxacin : death |

| Shaulov et al [7] | 44 | M | Tobacco Alcohol |

RUL | Blood Sputum |

ceftriaxone + azithromycin + metronidazole : death |

| Maharaj et al [8] | 63 | F | COPD* Tobacco |

RUL | Sputum BAL* |

ceftazidime: Survival |

| Ayumi Fudji et al [9] | 29 | M | None | RUL | Sputum Blood |

tazocillin : Survival |

| Quirk et al [10] | 40 | F | None | LUL | Eye Skin biopsy Sputum |

ceftazidime : Survival |

| Present case (Riviere et al) |

80 | M | Corticosteroids | RUL | Blood BAL |

cefepime : Survival |

*LUL: left upper lobe / RUL: right upper lobe.

*M: male / F: female.

*COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

*BAL: bronchoalveolar lavage

The literature review did not show any specific radiologic symptomatology of necrotizing CAP due to P. aeruginosa. However Hatchette et al. [11] described two-thirds of this pneumonia occurs in the right upper lobe, which was the case for our patient. Fetzer et al. reviewed a series of 7 autopsies and described two presentations of P. aeruginosa CAP: the presence of diffuse subpleural hemorrhagic nodular lesions and occasional necrotic parenchyma; or the formation of a 5 cm necrotic lung lesion within the lobular boundaries that included multiple necrotic nodules surrounded by hemorrhagic parenchyma [12].

Regarding antimicrobial management for CAP, the literature is summarized in Table 1 [[1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10]]. It is generally not appropriate to administer empiric anti-Pseudomonas therapy. However, based on the severity of the clinical presentation, the need for care in the ICU, along with the presence of P. aeruginosa infection risk factors, broader antimicrobial therapy can be considered. In our case, the risk factors were old age and the use of corticosteroids. Our patient was immunocompromised after receiving a cumulative dose of prednisone greater than 600 mg which is associated with a risk of opportunistic infections. Furthermore, P. aeruginosa is more likely to colonize recently hospitalized patients, as it was the case for this patient. These additional risk factors may discuss an initial broader antibimicrobial therapy. There are only few studies comparing anti-pseudomonal monotherapy versus combination of antibacterials. The current assumption is that two anti-pseudomonal antibiotics are required in case of bacteremia or severe pneumonia due to Pseudomonas. Indeed, one report found that the therapeutic association was associated with a higher mortality rate than monotherapy for older patients [13]. While in some cases the evolution of the CAP due to P. aeruginosa can be devastating, in the present case, the outcome was favorable despite inadequate initial antimicrobial therapy and IV cefepime monotherapy during 3 weeks. This case shows that anti-pseudomonal monotherapy may be a better option for older patients. Indeed, although the most commonly used antimicrobial is ceftazidime, no study has shown a difference in survival between cefepime and ceftazidime in severe bacterial infections. In addition, it seems that cefepime has a better diffusion into the lung. This is the only the second case of septic shock secondary to P. aeruginosa necrotizing CAP with bacteremia in a patient with favorable outcome [14].

For our patient, host risk factors were old age and the use of corticosteroids. Pathogen related virulence factors in similar cases have not been described in the literature. For our patient pathogen related virulence factors have been investigated: it is a wild P. aeruginosa that does not have virulence factors. The strain does not produce the exotoxin ExoU of the type III secretion system (major factor of virulence in the lung). Detection of Colistin resistance was negative. These elements do not explain the speed of installation or the severity of the infection. We propose that a future research of P. aeruginosa virulence factors leading to cavitary pneumonia could explain the severity and rapid progression of the disease.

Authors_statement

The authors state that this work has not been submitted and published in another journal.

The publication has been approved by all authors, the responsible authorities under whose aegis the work has been carried out.

If the article is accepted, it can not be published elsewhere, including in electronic format, in the same form, in English or in any other language, without the prior permission of the publisher holding the copyright.

Acknowledgements

PR wrote the article, made the bibliographic research and the submission of this clinical case.

DP made the bibliographic research, proofreading and layout.

ED contributed to the review of literature and proofreading.

HM participated in the review of literature and correction.

SL participated in proofreading and layout of the table and Fig. 1.

FP participated in the review of the literature and correction of the document.

PV participated in the review of literature and correction

JD participated in the review of literature and correction

PJ participated in the review of literature and correction

GB had the idea of writing this case report, participated in the bibliography research and proofreading of the document.

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

There is no funding source or support for this case report.

Ethical approval was not required for this case report.

References

- 1.Kunimasa K., Ishida T., Kimura S. Successful Treatment of Community-Acquired fulminant Pseudomonas aeruginosa Necrotizing Pneumonia in a Previously Healthy Young Man. Intern Med. 2012;51(17):2473–2478. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.51.7596. Epub 2012 Sep 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crnich C.J., Gordon B., Andes D. Hot tub-associated necrotizing pneumonia due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:e55–e57. doi: 10.1086/345851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sakamoto N., Tsuchiya K., Hikone M. Community-acquired necrotizing pneumonia with bacteriemia Caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a patient with emphysema: An autopsy case report. Respir Investig. 2018;56(Mar (2)):189–194. doi: 10.1016/j.resinv.2017.12.008. Epub 2018 Jan 12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gharabaghi M.A., Abdollahi S.M., Safavi E. Community Acquired Pseudomonas pneumonia in an immune competent host. BMJ Case Rep. 2012;(May) doi: 10.1136/bcr.01.2012.5673. 2012, pii: bcr0120125673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vikram H.R., Shore E.T., Venkatesh P.R. Community Acquired Pneumonia Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Conn Med. 1999;63(May (5)):271–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Okamoto M., Yamaoka J., Chikayama S. Successful Treatment of a Previously Healthy Woman with Pseudomonas aeruginosa Community-acquired Pneumonia Plasmapheresis. Intern Med. 2012;51(19):2809–2812. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.51.7921. Epub 2012 Oct 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shaulov A., Benenson S., Cahan A. A 44-year-old man with Cavitary pneumonia and shock. Neth J Med. 2011;69(Sep (9)):402–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maharaj S., Isache C., Seegobin K. Necrotizing Pseudomonas aeruginosa Community-Acquired Pneumonia: A case report and Review of the Literature. Case Rep Infect Dis. 2017 doi: 10.1155/2017/1717492. 2017, Epub 2017 May 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fujii A., Seki M., Higashiguchi M. Community-acquired, hospital-acquired, and healthcare-associated pneumonia Caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Respir Med Case Rep. 2014;12(Mar (30-3)) doi: 10.1016/j.rmcr.2014.03.002. eCollection 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quirk J.A., Beaman M.H., Blake M. Community-acquired pseudomonas pneumonia in a normal host panophtalmittis complicated by metastatic cutaneous and pustules. Aust N Z J Med. 1990;20(Jun (3)):254–256. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.1990.tb01033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hatchette T.F., Gupta R., Marrie T.J. Pseudomonas aeruginosa community-acquired pneumonia in previously healthy adults: case report and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:1349–1356. doi: 10.1086/317486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fetzer A.E., Werner A.S., Hagstrom J.W. Pathologic features of pseudomonal pneumonia. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1967;96:1121–1130. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1967.96.6.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Obodozie-Ofoegbu O.O., Teng C., Mortensen E.M. Antipseudomonal monotherapy or combination therapy for older adults with community-onset pneumonia and multidrug-resistant risk factors: a retrospective cohort study. Am J Infect Control. 2019;(Mar) doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2019.02.018. pii: S0196-6553(19)30106-3. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoogwerf B.J., Khan M.Y. Community-acquired bacteremic Pseudomonas pneumonia in a health adult. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1981;123(Jan (1)):132–134. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1981.123.1.132. PubMed PMID: 6779684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]