Abstract

Background

Violence against women represents a violation of a fundamental human right and is a significant cause of death and disability worldwide. In developing countries, this issue is particularly dramatic and in sub-Saharan Africa were reached 65% of women reporting domestic violence.

Objective

In this study, we assessed the burden and pattern of domestic violence registered at Beira Central Hospital, Mozambique from 2011 to 2015.

Methods

We performed a descriptive analysis of data collected at the CHB Legal Medicine Service.

Results

In five years, are recorded a total amount of 1,491 admissions for domestic violence of which 1307 were females. About 80% of all female cases are represented by the 11–40 age range and, in almost 90% the aggressor was the current or past partner. More than 75% were cases of repeated violence and in more than 60% there were minors attending the phenomenon.

Conclusion

It is crucial to act immediately and with a multi-disciplinary approach in order to fight domestic violence, especially against women due to its dramatic consequences as isolation, inability to work, loss of wages, lack of participation in regular activities and limited ability to care for themselves and their children.

Keywords: Domestic violence, violence against women, sexual violence, physical violence

Introduction

Violence against women is a violation of a fundamental human right with significant impact on the public health involving physical, sexual, reproductive and mental state of a woman and it represents a significant cause of death and disability worldwide1. Violence against women includes physical, sexual and psychological violence occurring in the family (including battering, sexual abuse of female children in the household, dowry-related violence, marital rape, female genital mutilation and other traditional practices harmful to women, non-spousal violence and violence related to exploitation). Physical, sexual and psychological violence also occurring within the general community and they are often perpetrated or condoned by the State, wherever it occurs2. Although reducing violence against women is indicated as a key strategy for the achievement of the Millennium Development Goals and many efforts are underway in order to prevent and eliminate violence against women and girls worldwide, but we are still far from the achieving this goal3,4.

A particular form is the domestic violence or intimate partner violence that refers to the range of sexual, psychological, and physical coercive acts used against adult and adolescent women by current or former male intimate partners4. Intimate partner abuse may take various form, including physical violence, sexual violence emotionally abusive behaviors (such stalking, belittlement, humiliation) and economic restriction5. It is estimated that, worldwide, between 10 to 60% of women who have ever been married or partnered have experienced at least one incident of physical violence from a current or former partner6. The wide variation in the prevalence reported is due to different factors: studies methods and design, differences in violence definition and measurement, and lack of data from developing countries4,6.

The WHO Multi-country study on Women's Health and Domestic Violence Against Women, performed in 10 countries, showed that a variable proportion between 15–71% of ever-partnered women had experienced physical or sexual violence and the greatest amount was reported in Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Peru, and Tanzania6. Unfortunately, violent acts were not isolated events but, in the majority repeated and sometimes frequent.

Despite lack and poor quality of data, in sub-Saharan Africa 65% of women reported domestic violence7. The Demographic Health Survey conducted in seven sub-Saharan African countries (Cameroon, Kenya, Malawi, Rwanda, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe) reported a wide percentage of women (15–49 years) who had experienced physical violence ranging from around 30% in Malawi to 60% in Uganda8.

In Mozambique, the few data available suggests that violence against women is widespread with 54% of polled women had been subject to physical or sexual violence and it is a more evident phenomenon in both rural and urban areas9,10.

The aim of our study was to assess the burden and pattern of domestic violence based on Legal Medicine registers of Beira Central Hospital, Mozambique from 2011 to 2015.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by National Ethical Board (CNBS) by the Protocol Number 108/CNBS/17

Setting

The city of Beira has about 500,000 inhabitants, of which 17% are less than 5 years. The Central Hospital of Beira (CHB) is a 1020-bed government tertiary referring and teaching Hospital for the central region of the Country (population of about 7 million) in Mozambique and the second hospital in the country. The CHB Legal Medicine service, counting on four specialists, is a landmark for the whole city of Beira and represents the institution that assists justice in different areas of law, both for the requests of prosecutor's offices, court and the criminal police.

Methods

The CHB Legal Medicine specialists collected and reviewed all out-patient records of patients admitted to the Service during the 2011–2015 period. The extracted data provided a database with personal and related to violence information, organized in the following variables: gender, age group (0–10, 11–20, 21–30, 31–40, over 40 years) and employment of the victim, referring institution, type of violence, episode's severity, relationship with the perpetrator, reason, repetition, setting and location of the event, presence of other people at the event, time interval between event and specialist counseling.

We conducted a descriptive analysis of the collected data as yet available.

Results

From 2011 to 2015, the number of visits progressively increased from 30 to 505, for a total amount of 1,491 admissions over the five-year period considered (Table 1). Over two-thirds of the visits concerns victims that had been addressed to the Legal Medicine Service by the Women's Law Association And Development (Muleide) (1,137, 76.1%), one fifth by the Police (303, 20.3%), the remaining by the accuser (13, 0.9%) and the Tribunal (6, 0.4%). In three cases, it has been indicated that the person had been sent to a specialist visit from more than one institution. In only 2.3% of cases the referring institution is not indicated.

Table 1.

Admissions distribution by year

| Year | No admissions |

| 2011 | 30 |

| 2012 | 261 |

| 2013 | 235 |

| 2014 | 460 |

| 2015 | 505 |

| Total | 1,491 |

The vast majority of visits concerns women (1,307 female vs 170 male), determining a male: female ratio of about 1:8. Missing data are 14 (0.9%).

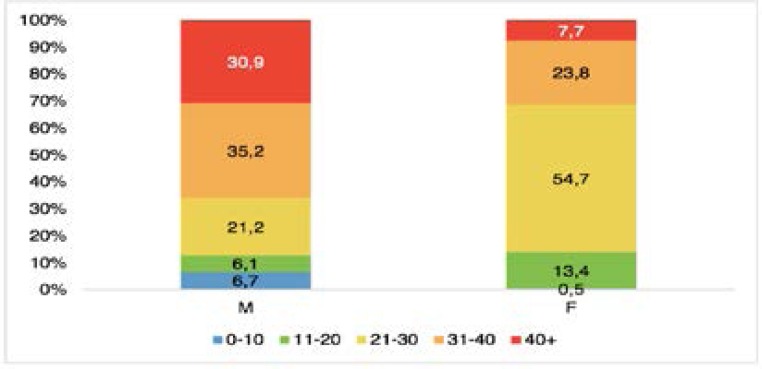

Global admissions distribution by age shows that the third decade of life is the most represented, covering half of the cases (744); 24.6% (367) concerns subjects aged between 31 and 40, 12.8% (188) ranging from 11 to 20, 1.3% (19) children and the rest (151) pertains to people over 40 years of age. Admissions distribution stratified by age and gender shows differences between males and females, as shown in the figure below (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Admissions distribution by gender and age.

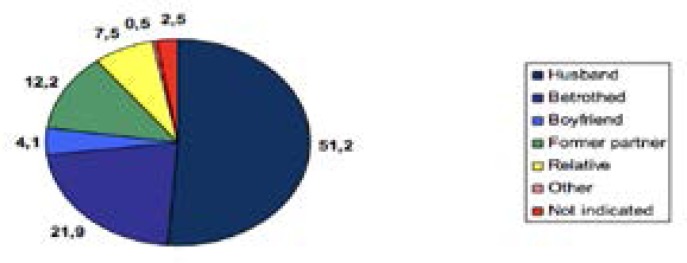

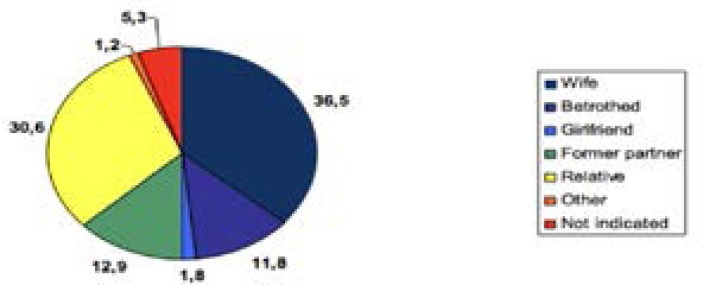

Accesses distribution by aggressor was stratified by gender of the victim, indicating significant differences between males and females: nearly three-quarters of these are attacked by the current partner (77.2%), 12.2% by the former partner, 7.5% by a family member. Regard to males, the aggressor is the partner in half the cases, the former partner in 12.9% and a family member in almost a third of the cases (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2.

Female's admissions distribution by abuser.

Figure 3.

Male's admissions distribution by abuser.

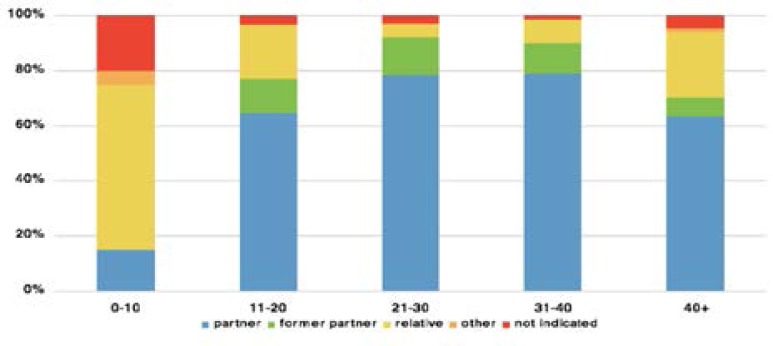

Stratification of admissions by aggressor and age of the victim shows that, during childhood (0–10 years), the abuser is a relative in the majority of the episodes and in 20% the aggressor is not indicated. In the other age groups, the aggressor is usually represented by the partner or, less commonly, by the former partner, as depicted in the chart below (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Admissions distribution by age and abuser.

Physical assault, unrelated to other forms of abuse, represents almost all forms of reported violence, involving 96% of admissions (1,431) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Admissions distribution by type of abuse.

| Type of abuse | N | % |

| Physical | 1,431 | 96.0 |

| Psychological | 8 | 0.5 |

| Sexual | 2 | 0.1 |

| Physical + psychological | 19 | 1.3 |

| Physical + sexual | 3 | 0.2 |

| Physical + psychological + sexual | 1 | 0.1 |

| Not indicated | 27 | 1.8 |

| Total | 1,491 | 100 |

In 45.7% of cases, it is not indicated whether the current episode is the first; among the remaining, the majority is part of a repeating phenomenon (622 repeated event vs 187 first time event).

With regard to the presence of witnesses of violence, the data is unknown for more than 70%. Among the 406 cases in which it was collected, it emerges that in 63% of the events there were minor attending alone (231) or in the presence of adults (26).

The accessibility of the service has been explored considering the time interval between the abuse and the legal advice, which in the vast majority of cases (1,153) was carried out over the first week of the episode (90%).

Discussion

Domestic violence represents a worldwide multifactorial issue involving community, educational, social, political and health aspects. In developing countries, the problem of domestic violence and, in particular, violence against women is pronounced since resources are limited, and women often have highly constrained choices for economic, social, and emotional reasons. Mozambique has one of the lowest human and social development indicators in the world, ranking at 185 out of 187 countries with a Human Development Index of 0.327 in 201611. In addition, across the country, official, quality and standardized data are missing and domestic violence represents a neglected issue.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study in Mozambique assessing the burden and the pattern of domestic violence.

The main finding of our study is the steady increase in the number of cases referred and reported at the Legal Medicine service. More than a real increase, this trend reflects a better hospital organization (only in 2011 was a dedicated register introduced), a greater population awareness and the presence of organization focused on this topic as Muleide. Muleide is an association promoting gender balance, respect for the human rights of women (especially vulnerable women) and the enhancement of their social status. The main objective of Muleide is to sustain a fairer society, which guarantees rights equality between men and women and equal access and control of resources and power. This association seems to be crucial on this issue as referred over three-quarters of all women accessed to the Hospital service. As it was foreseeable, most of the victims (88.5%) were females highlighting that is urgent to implement and adopt laws, policies and strategies to prevent violence against women and girls and to increase usage of existing quality violence against women services. For both, males and females, the most affected age group seems to be between 20 and 40 years but maybe this represent only a major possibility for those to refer the violence. About 80% of all female cases are represented by the 11–40 age range, the fertile age, and it is related to the type of abuser. In fact, the aggressor of women victims was most of all the partner (or ex-partner) (89.4%) and only in 7.5% of cases was a family member. This data is particularly dramatic considering that they are or will be mothers and, thus, protecting them means protecting the present and future offspring. Instead, with regard to males, although in most cases the aggressor was the present or past partner, for more than 30% the violence was performed by a family member. These data, in addition to the data regarding violence suffered by children mainly by family members, suggests that preventive and educational interventions should be addressed not only women, in order to empower them, but also male and the whole community to educate them and prevent abusive behavior.

Another particular aspect emerging from our study concerns the nature of violence: more than 95% of reported, was physical violence. Of course, this is not the reality but reflect the context: on one hand, there are not trained health workers, tools and appropriate equipment to notice and record sexual and psychological violence. On the other hand, both victims and health workers are afraid of repercussions and retaliation. Moreover, we have to consider the psychological aspect for which, the victim of sexual abuse experiences deep feelings of guilt and shame, making it difficult to confess and even more to denounce the violence. These considerations not only stresses once again the necessity of prompt interventions for the victims but also urges measures in order to protect health workers allowing them to fulfill their duty of denunciation.

Despite the lack of accurate data, two other critical aspects emerge from our study: more than 75% (622/809) were cases of repeated violence and in more than 60% (257/406) of cases there were minor attending the phenomenon. As reported by international literature, usually violence is not a sporadic phenomenon, but is a chronic conduct within a relationship/but is a chronic way to relate between two specific individuals. Children's involvement in domestic violence, even if in the role of witnesses, is extremely worrying, in the light of the recent scientific evidence, which shows that assisted violence is comparable to directly suffered violence in terms of damage to child's development.

Finally, considering the time between the abuse and reference, the majority were referred within 7 days. In some respects, it is good because the victims do not spend much time before reporting but, at the same time, it could be a problem with some injuries, and therefore potential tests, may disappear.

The main limitations of this study are the poor quality and the lack of data due to the absence of guidelines and standardized case record. In fact, our data were extracted by descriptive reports drawn at the discretion of the doctor on duty, so we do not have the same indicators for each victim. We have no information regarding pregnant women nor number of deaths due to domestic violence. Moreover, we have no data regarding clinical conditions and the follow-up, so it is impossible to consider the implications and complications (i.e. orthopedic and gynecological).

Despite these limitations, our preliminary study has several health, legal, social and political implications:

I) Multi-sectorial policies should be developed that address discrimination against women, promote gender equality, support women and help to move towards more peaceful cultural norms; II) It is necessary to increase the awareness among the whole community; III) It is mandatory to create adequate and standardized guidelines and places to the management of victims in an integrated approach (medical, legal and psychological); IV) Health workers have to be trained, protected and well informed regarding legal duties in denouncing violence; V) It is desirable to create a community network that includes health services, police and associations.

Conclusion

This is a small step in fighting domestic violence, especially against women due to its dramatic consequences as isolation, inability to work, loss of wages, lack of participation in regular activities and limited ability to care for themselves and their children. More and larger studies are needed to know the state-of-the-art and the current evidence on this topic in order to facilitate the choice of the best strategy depending on the sociocultural and resource-dependent context. to facilitate the choice of the best strategy depending on the sociocultural and resource-dependent context.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

None.

References

- 1.WHO, author. Global and regional estimates of violence against women: prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. UN; 2013. [October 2017]. http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/violence/9789241564625/en/Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Watts C, Zimmerman C. Violence against women: global scope and magnitude. Lancet. 2002 Apr 6;359(9313):1232–1237. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08221-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO, author. Addressing violence against women and achieving the Millennium Development Goals. 2005. [October 2017]. http://www.who.int/gender/documents/MDGs&VAWSept05.pdf.

- 4.WHO, author. Researching Violence Against Women: A Practical Guide for Researchers and Activists. 2005. [October 2017]. http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/violence/9241546476/en/

- 5.Devries KM, Mak JY, García-Moreno C, Petzold M, Child JC, Falder G, Lim S, Bacchus LJ, Engell RE, Rosenfeld L, Pallitto C, Vos T, Abrahams N, Watts CH. Global health. The global prevalence of intimate partner violence against women. Science. 2013 Jun 28;340(6140):1527–1528. doi: 10.1126/science.1240937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.WHO, author. Multi-country Study on Women's Health and Domestic Violence against Women. 2005. [October 2017]. http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/violence/24159358X/en/

- 7.Durevall D, Lindskog A. Intimate partner violence and HIV in ten sub-Saharan African countries: what do the Demographic and Health Surveys tell us? Lancet Glob Health. 2015 Jan;3(1):e34–e43. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70343-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Africa Program. Gender-based Violence in sub-Saharan Africa: A review of Demographic and Health Survey findings and their use in National Planning. [October 2017]. https://www.wilsoncenter.org/event/gender-based-violence-sub-saharan-africa-review-demographic-and-health-survey-findings-and.

- 9.UN WOMEN. Africa, Mozambique: [October 2017]. http://africa.unwomen.org/en/where-we-are/eastern-and-southern-africa/mozambique. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cruz GV, Domingos L, Sabune A. The Characteristics of the Violence against Women in Mozambique. Health. 2014;6:1589–1601. [Google Scholar]

- 11.UNDP, author. Human Development Reports. 2016. [October 2017]. http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/human-development-index-hdi.