Abstract

SUMMARY – Schwannoma as an extracranial nerve sheath tumor rarely affects brachial plexus. Due to the fact that brachial plexus schwannomas are a rare entity and due to the brachial plexus anatomic complexity, schwannomas in this region present a challenge for surgeons. We present a case of a 49-year-old female patient with a slow growing painless mass in the right supraclavicular region that was diagnosed as schwannoma and operated at our department. The case is described to remind that in case of supraclavicular tumors, differential diagnosis should take brachial plexus tumors, i.e. schwannomas, in consideration. Extra caution is also required on fine needle aspiration procedures or biopsies of schwannomas due to the possible iatrogenic injury of the nerve and adjacent structures. On operative treatment of schwannoma, complete tumor resection should be achieved while preserving the nerve.

Key words: Neurilemmoma; Nerve Sheath Neoplasms; Brachial Plexus; Biopsy, Fine-Needle; Case Reports

Introduction

Schwannoma or neurilemmoma is a benign encapsulated nerve sheath tumor that arises from the Schwann cells along the course of a nerve and can affect the third to twelfth cranial nerves, peripheral and autonomic nerves (1-4). Schwannomas rarely affect brachial plexus, accounting for approximately 5% of all cases of schwannomas (5, 6). Due to the fact that brachial plexus schwannomas are a rare entity and due to the brachial plexus anatomic complexity, schwannomas in this region present a challenge for surgeons.

Case Report

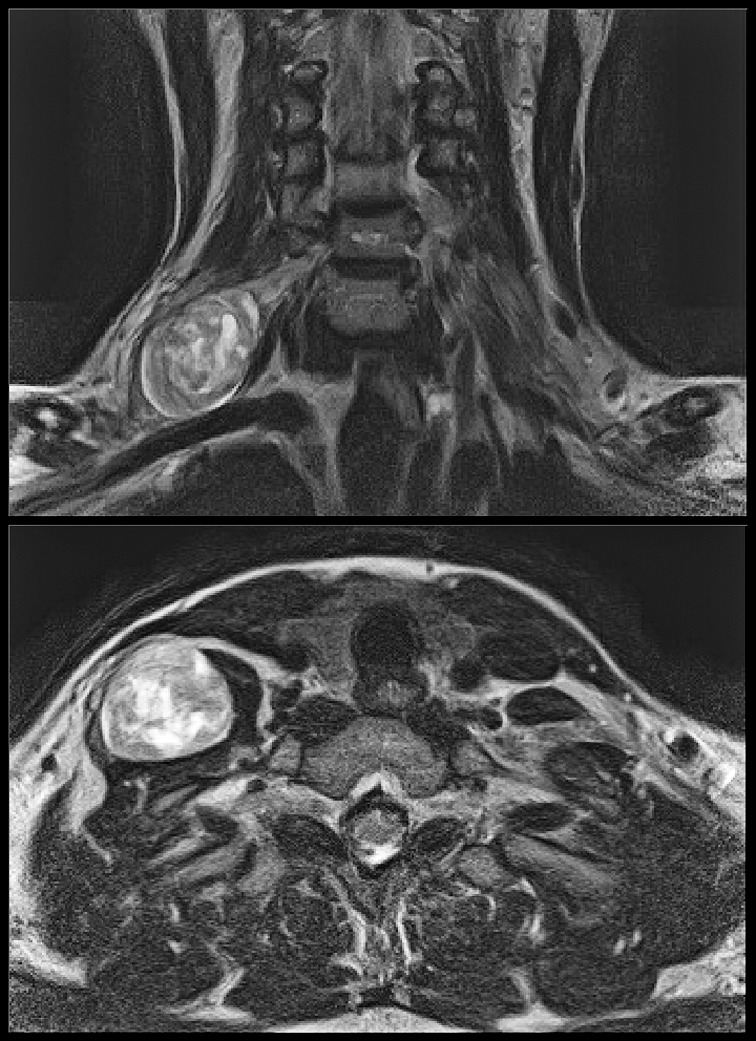

We present a case of a 49-year-old female patient with a slow growing painless mass in the right supraclavicular region, observed one year before first examination. On examination, the patient had a firm, mobile swelling in her right supraclavicular region without weakness, numbness or loss of function of the upper limb. There were no changes in color or pulse of the arm, and no indications of swelling or muscle atrophy. The rest of the neck was normal on palpation. Ear, nose and throat examination showed unremarkable findings. Personal medical history was without any remarks. Family history was negative for similar tumor. After physical examination and ultrasound examination of the neck, fine needle aspiration cytology of the tumor was recommended. During the fine needle aspiration procedure of the tumor, the patient felt painful sensations on the dorsum of the thumb and forefinger of her right hand. Cytologic findings suggested mesenchymal tumor. Then, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed to define tumor location and size, and to delineate tumor margins and relationship with adjacent structures (7). MRI revealed a sharply delineated spindle shaped lesion of 61x28x34 mm in size, indivisible of C7 nerve, from its roots at the C5-6 level segment and the middle trunk of the brachial plexus, which was moderately heterogeneously contrast imbibed (Fig. 1). On tumor palpation, the neurologist recorded unpleasant sensory sensations in the C6 dermatome due to irritation of C6 root sensory fibers. Preoperative electrodiagnostic study (electrophysiological examination) revealed normal sensory and motor nerve conduction.

Fig. 1.

Radiological findings. Magnetic resonance imaging, coronal and axial scans showing a large schwannoma arising from the right brachial plexus.

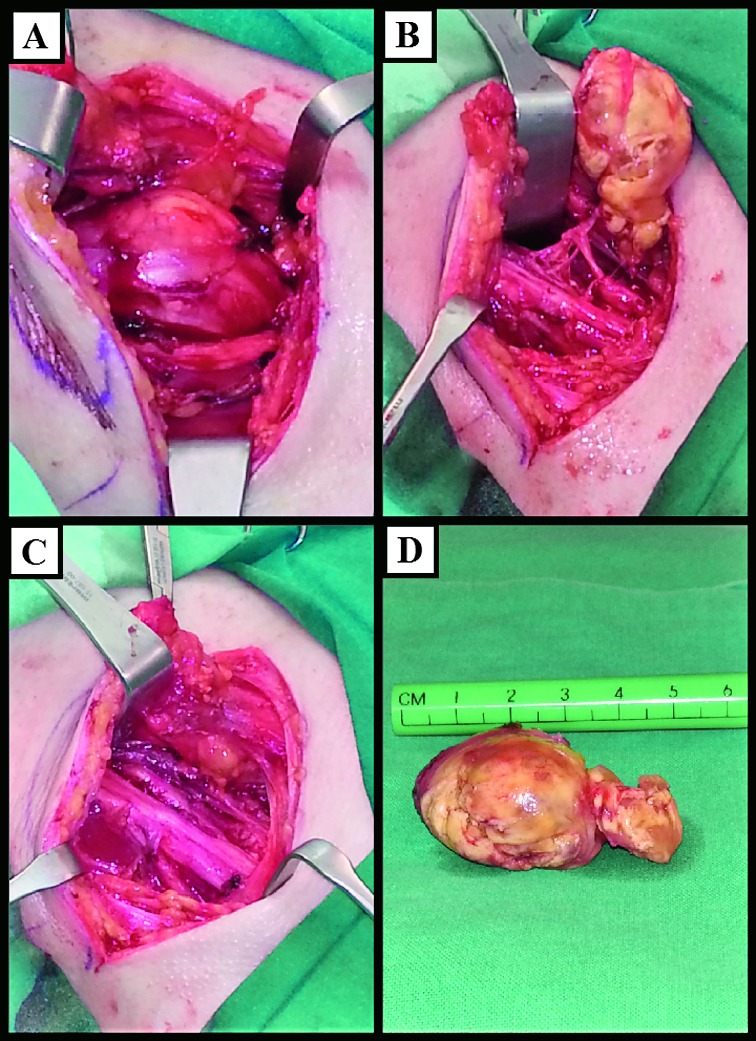

In May 2014, the patient underwent enucleation of the tumor under general anesthesia through the anterior supraclavicular approach. Exploration revealed the tumor which was a smooth oval formation with nerve fascicles stretched and displaced over the dome of the mass (Fig. 2). The tumor was attached eccentrically to the axis to the nerve, without nerve enlargement. After identification of the tumor, all attention was devoted to the identification, isolation and mobilization of all adjacent plexus elements. We were able to dissect nerve fascicles and enucleate the tumor with preservation of all the nerve fascicles.

Fig. 2.

Intraoperative findings. (A) Encapsulated mass splitting the fasciscles of the right brachial plexus; (B) schwannoma after separation from fascicles of the brachial plexus; (C) brachial plexus after enucleation of schwannoma; (D) enucleated schwannoma, macroscopic view.

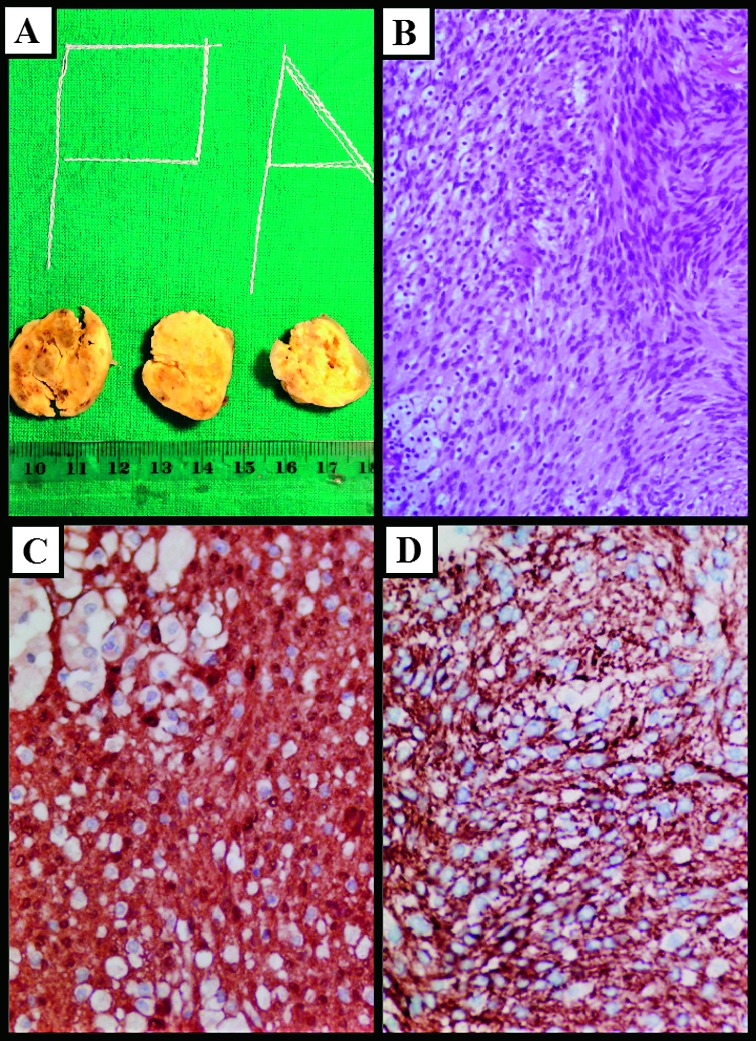

The histopathologic diagnosis was schwannoma. The specimen obtained was an encapsulated oval, soft tumor, grossly measuring 4.5x3.5x2.5 cm. The cut surface was yellowish with areas of hemorrhage (Fig. 3). Histologically, the tumor was composed of spindle shaped cells arranged in interlacing fascicles with nuclear palisading. Focal pseudocystic areas and foamy histiocytes were also found, as well as hyalinized blood vessels. There was no nuclear atypia or mitotic activity. Immunohistochemical analysis showed diffuse strong expression of S-100 protein and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) in tumor cells.

Fig. 3.

Histologic findings. (A) Tumor cut surface was yellowish with focal areas of hemorrhage; (B) fascicles of monomorphic spindle shaped cells and foamy histiocytes (hematoxylin and eosin staining, X20); (C) intense cytoplasmic expression of S100 in tumor cells (X40); (D) intense cytoplasmic expression of GFAP in tumor cells (X40).

Postoperatively, the patient developed paresthesia and numbness in the first three fingers of her right hand. Electromyoneurography done two months after the surgery showed reduced sensory potential amplitude of the right median nerve compared to the preoperative findings. There were no signs of damage to the motor fibers. Three months after the operation, the patient confirmed improvement of the postoperative status and paresthesia of only the tip of the thumb and forefinger of her right hand. Physical therapy was performed. Fourteen months after the surgery, there was no radiological evidence of recurrence but the patient still had paresthesia of the tip of her right thumb and forefinger.

Discussion

Primary tumors of the brachial plexus are rare (7) and can be divided into two groups, peripheral neural sheath tumors and peripheral non-neural sheath tumors. Schwannomas, together with neurofibromas, are peripheral nerve sheath tumors and rarely affect brachial plexus (5, 8, 9). In the literature, most of the publications on brachial plexus schwannomas are case reports or small series of patients (2-4, 6-13). Among studies with larger number of cases are those by Knight et al., who present 94 cases of brachial plexus schwannomas (1), and by Kim et al. who present a series of 54 brachial plexus schwannomas treated over 30 years (14). In Croatia, we found only one case report of brachial plexus schwannoma that manifested as apical thoracic schwannoma (15).

The majority of schwannomas arise sporadically as a single benign tumor although there are cases of multiple schwannomas (12). Schwannomas usually arise spontaneously although schwannomas are a principal feature of two hereditary tumor diseases, neurofibromatosis type 2 and schwannomatosis (16). A defining feature for neurofibromatosis type 2 is the presence of bilateral vestibular schwannomas and only 4% of all schwannomas are associated with neurofibromatosis type 2 (12, 16). Small tumors are usually uninodular but larger tumors may be multinodular with degenerative features including cyst formation, fibrosis and calcification (1, 17).

Clinical presentation of brachial plexus tumors is variable according to its location, extension, neural elements involved and pathology (7). Symptoms are caused by direct nerve invasion, infiltration of surrounding tissues, or local mass effect (7). Schwannomas in this region usually present as a local slow growing mass but may present with symptoms of nerve compression (10). According to Go et al., a growing mass is the most common presenting symptom (95%); other presenting signs and symptoms are paresthesia and numbness (54%), direct tenderness and pain (27%), and radiating pain (23%) (7). In patients included in the study by Lee et al., the most common presenting symptom was a palpable mass and tingling sensation when the mass was compressed (8). In the study by Go et al., preoperative sensory deficit was more common than preoperative motor deficit (54% vs. 41% of patients) (7). According to Knight et al., painful paresthesia in the distribution of the involved nerve induced by percussion is the single most useful sign in diagnosing schwannoma (1). Tang et al. claim that positive Tinel’s sign carries a high predictive value for schwannoma although they had a series of 8 patients (3). According to some authors, schwannomas are mobile from side to side but fixed in the long axis of the nerve (12).

Differential diagnosis of supraclavicular tumors includes different benign and malignant conditions such as supraclavicular lymph node, lipoma, lymphangioma, hemangioma, lymphoma, lymph node metastasis, fibrosarcoma, leiomyosarcoma, sarcoidosis, and tuberculosis (18). Other possible conditions are schwannoma, neurofibroma, granular cell tumor, schwannomatosis, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors and malignant granular cell tumors. Neurofibromas are also benign peripheral nerve sheath tumors that arise from the connective tissue of peripheral nerve sheaths (4). Neurofibroma mostly produces fusiform enlargement of the involved nerve, and fascicles are embedded in the tumor, which makes it impossible to distinguish between tumor and neural tissue (7, 8). Neurofibromas are mostly solitary but may occur as multiple tumors in neurofibromatosis type 1 (4). Schwannomatosis or neurilemmomatosis is a hereditary disease (12, 16), which presents with two or more nonintradermal schwannomas and at least one has histologic confirmation (19). Patients with schwannomatosis must not fulfill diagnostic criteria for neurofibromatosis type 219. Features that are characteristic of neurofibromatosis type 1, such as six or more café-au-lait spots, freckling in the axillary or inguinal region, and two or more Lisch nodules are not associated with schwannomatosis (12, 20). Malignant change does not occur in schwannomatosis but it does in neurofibromatosis type 1 (12). Granular cell tumor is fusiform and multiple lobulate enlargement of the involved nerve, which is similar to gross features of neurofibromas, but has much harder consistency with poor demarcation between neural tissue and tumor, which impedes complete tumor resection (7). Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNST) often produce loss of peripheral function unlike schwannomas (12). MPNST are usually seen in neurofibromatosis type 1 (18).

Fine needle aspiration procedures and biopsy are limited because the procedure can damage intact fascicles or cause hemorrhage and lead to neurological deficit (8, 10). Microscopically, the tumor contains a mixture of two distinctive areas. Antoni A areas are cellular with nuclear palisading and Verocay bodies where two rows of palisading nuclei are separated by pink fibrillary material. Antoni B areas are less cellular and microcystic areas. Degenerative changes such as cyst formation, focal calcifications and hyalinized, thrombosed blood vessels with associated hemorrhage and deposition of fibrin are typically present. An inflammatory infiltrate is present, especially histiocytes (21).

Yafit et al. propose an algorithm for treating extracranial head and neck schwannomas and it includes three treatment options, i.e. expectant observation in asymptomatic patients, surgery for better long-term results in patients with progressive or symptomatic disease, and radiotherapy in symptomatic patients unsuitable to undergo surgical treatment (22). According to Knight et al., each mass arising from a nerve trunk which causes pain and which is attended by deepening loss of function is considered a malignant tumor until proven otherwise (1). Resection of tumor is the choice in most of benign and malignant brachial plexus tumors (7).

There are several surgical approaches depending on tumor localization. An anterior supraclavicular approach is convenient for tumors involving roots and trunks. Lower tumors involving cords and terminal nerves require an anterior infraclavicular approach; when there is more extensive involvement of the plexus, including its retroclavicular part, a combined anterior approach with or without section of the clavicle is necessary (7). Knight et al. in their study recommend the following approaches: supraclavicular approach, transclavicular exposure, and posterior subscapular approach (1). Ahn et al. prefer intracapsular approach, where after the almost complete removal of the tumor, the capsule is carefully dissected from the brachial plexus (20). Lee et al. also advocate intracapsular incision since extracapsular excision can damage normal fascicles during dissection of the capsule (8). Surgical approach does not have influence on postoperative outcomes, as these are related to the grade of resection at surgery and pathologic features of the tumor (7).

Postoperative neurological dysfunction may occur after total resection. Postoperative paresthesia and numbness developed in 3 of 22 patients who had relatively small size tumors (7). Transitory nerve paresis may occur even when benign tumors are carefully dissected. Tang et al. have reported in their study that schwannomas had in large proportion fascicular involvement that would consequently lead to distal neurological deficit because fascicular involvement could not be identified preoperatively (3). Also, the tumor and the fascicles cannot be divided using microscopy during excision, so a portion of fascicles have to be excised with the tumor (3). These authors call for caution when motor nerve or mixed nerve is damaged because then the surgeon should consider using nerve (intrafascicular) graft. In the case of distal sensory deficit, nerve graft is not recommended since it is considered clinically insignificant because of overlapping of sensory nerves (3).

Conclusion

The case is presented to remind that in case of supraclavicular tumors, brachial plexus tumors, that is schwannomas, should be considered on differential diagnosis. Extra caution is required with fine needle aspiration procedures or biopsies of the schwannomas due to the possible iatrogenic injury of the nerve and adjacent structures. The operative treatment of schwannoma should achieve complete tumor resection while preserving the nerve.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Assist. Prof. Anita Škrtić and Nikolina Vučemilo for supervision and technical help.

References

- 1.Knight DM, Birch R, Pringle J. Benign solitary schwannomas: a review of 234 cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:382–7. 10.1302/0301-620X.89B3.18123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yun DH, Kim HS, Chon J, Lee J, Jung PK. Thoracic outlet syndrome caused by schwannoma of brachial plexus. Ann Rehabil Med. 2013;37:896–900. 10.5535/arm.2013.37.6.896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tang CY, Fung B, Fok M, Zhu J. Schwannoma in the upper limbs. BioMed Res Int. 2013;2013:167196. 10.1155/2013/167196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kohyama S, Hara Y, Nishiura Y, Hara T, Nakagawa T, Ochiai N. A giant plexiform schwannoma of the brachial plexus: case report. J Brachial Plex Peripher Nerve Inj. 2011;6:9. 10.1186/1749-7221-6-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lusk MD, Kline DG, Garcia CA. Tumors of the brachial plexus. Neurosurgery. 1987;21:439–53. 10.1227/00006123-198710000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumar A, Akhtar S. Schwannoma of brachial plexus. Indian J Surg. 2011;73:80–1. 10.1007/s12262-010-0141-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Go MH, Kim SH, Cho KH. Brachial plexus tumors in a consecutive series of twenty-one patients. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2012;52:138–43. 10.3340/jkns.2012.52.2.138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee HJ, Kim JH, Rhee SH, Gong HS, Baek GH. Is surgery for brachial plexus schwannomas safe and effective? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472:1893–8. 10.1007/s11999-014-3525-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fujii T, Yajima R, Morita H, Yamaguchi S, Tsutsumi S, Asao T, et al. FDG-PET/CT of schwannomas arising in the brachial plexus mimicking lymph node metastasis: report of two cases. World J Surg Oncol. 2014;12:309. 10.1186/1477-7819-12-309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rashid M, Salahuddin O, Yousaf S, Qazi UA, Yousaf K. Schwannoma of the brachial plexus; report of two cases involving the C7 root. J Brachial Plex Peripher Nerve Inj. 2013;8:12. 10.1186/1749-7221-8-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen F, Miyahara R, Matsunaga Y, Koyama T. Schwannoma of the brachial plexus presenting as an enlarging cystic mass: report of a case. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;14:311–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ogose A, Hotta T, Morita T, Otsuka H, Hirata Y. Multiple schwannomas in the peripheral nerves. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1998;80:657–61. 10.1302/0301-620X.80B4.8532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patel ML, Sachan R, Seth G. Radheshyam. Schwannoma of the brachial plexus: a rare cause of monoparesis. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013:bcr2012008525. 10.1136/bcr-2012-008525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim DH, Murovic JA, Tiel RL, Moes G, Kline DG. A series of 397 peripheral neural sheath tumors: 30-year experience at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Centre. J Neurosurg. 2005;102:246–55. 10.3171/jns.2005.102.2.0246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vucetic B, Hudorovic N, Vicic-Hudorovic V. Supraclavicular approach for removal of apical thoracic schwannoma. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2015;127:497–8. 10.1007/s00508-014-0654-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pećina-Šlaus N, Zeljko M, Pećina HI, Nikuševa Martić T, Bačić N, Tomas D, et al. Frequency of loss of heterozygosity of the NF2 gene in schwannomas from Croatian patients. Croat Med J. 2012;53:321–7. 10.3325/cmj.2012.53.321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jadhav CR, Angeline NR, Kumar B, Bhat RV, Balachandran G. Axillary schwannoma with extensive cystic degeneration. J Lab Physicians. 2013;5:60–2. 10.4103/0974-2727.115925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boulanger X, Ledoux JB, Brun AL, Beigelman C. Imaging of the non-traumatic brachial plexus. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2013;94:945–56. 10.1016/j.diii.2013.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baser ME, Friedmann JM, Evans DG. Increasing the specificity of diagnostic criteria for schwannomatosis. Neurology. 2006;66:730–2. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000201190.89751.41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahn JY, Kwon SO, Shin MS, Shim JY, Kim OJ. A case of multiple schwannomas of the trigeminal nerves, acoustic nerves, lower cranial nerves, brachial plexuses and spinal canal: schwannomatosis or neurofibromatosis? Yonsei Med J. 2002;43:109–13. 10.3349/ymj.2002.43.1.109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anghel A, Tudose I, Terzea D, Raducu L, Sinescu RD. Unusual median nerve schwannoma: a case presentation. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2014;55:159–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yafit D, Horowitz G, Vital I, Locketz G, Fliss DM. An algorithm for treating extracranial head and neck schwannomas. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;272:2035–8. 10.1007/s00405-014-3156-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]