Foamy viruses are the oldest known retroviruses and have been mostly described to be nonpathogenic in their natural animal hosts. SFVs can be transmitted to humans, in whom they establish persistent infection, like the simian lenti- and deltaviruses that led to the emergence of two major human pathogens, human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and human T-lymphotropic virus type 1. This is the first identification of an SFV-specific B-cell epitope recognized by human plasma samples. The immunodominant epitope lies in gp18LP, probably at the base of the envelope trimers. The NHP species the most genetically related to humans transmitted SFV strains that induced the strongest antibody responses. Importantly, this epitope is well conserved across SFV species that infect African and Asian NHPs.

KEYWORDS: emergence, retrovirus, antibody, zoonotic infections

ABSTRACT

Cross-species transmission of simian foamy viruses (SFVs) from nonhuman primates (NHPs) to humans is currently ongoing. These zoonotic retroviruses establish lifelong persistent infection in their human hosts. SFV are apparently nonpathogenic in vivo, with ubiquitous in vitro tropism. Here, we aimed to identify envelope B-cell epitopes that are recognized following a zoonotic SFV infection. We screened a library of 169 peptides covering the external portion of the envelope from the prototype foamy virus (SFVpsc_huHSRV.13) for recognition by samples from 52 Central African hunters (16 uninfected and 36 infected with chimpanzee, gorilla, or Cercopithecus SFV). We demonstrate the specific recognition of peptide N96-V110 located in the leader peptide, gp18LP. Forty-three variant peptides with truncations, alanine substitutions, or amino acid changes found in other SFV species were tested. We mapped the epitope between positions 98 and 108 and defined six amino acids essential for recognition. Most plasma samples from SFV-infected humans cross-reacted with sequences from apes and Old World monkey SFV species. The magnitude of binding to peptide N96-V110 was significantly higher for samples of individuals infected with a chimpanzee or gorilla SFV than those infected with a Cercopithecus SFV. In conclusion, we have been the first to define an immunodominant B-cell epitope recognized by humans following zoonotic SFV infection.

IMPORTANCE Foamy viruses are the oldest known retroviruses and have been mostly described to be nonpathogenic in their natural animal hosts. SFVs can be transmitted to humans, in whom they establish persistent infection, like the simian lenti- and deltaviruses that led to the emergence of two major human pathogens, human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and human T-lymphotropic virus type 1. This is the first identification of an SFV-specific B-cell epitope recognized by human plasma samples. The immunodominant epitope lies in gp18LP, probably at the base of the envelope trimers. The NHP species the most genetically related to humans transmitted SFV strains that induced the strongest antibody responses. Importantly, this epitope is well conserved across SFV species that infect African and Asian NHPs.

INTRODUCTION

Simian foamy viruses (SFVs) are widespread and highly prevalent in nonhuman primates (NHPs). Cross-species transmission of SFV infecting apes and Old World monkeys (OWM) to humans leads to persistent infection, as reported by more than 15 studies carried out worldwide (1, 2). Human exposure to SFV from New World monkeys (NWM) leads to SFV-specific seroreactivity, with undetectable blood SFV DNA (3, 4). Almost all SFV-infected individuals were bitten or injured by a NHP, and no case of human-to-human SFV transmission has yet been reported (1, 2, 5). Therefore, most SFV-infected humans are the first hosts of a zoonotic simian retrovirus. Zoonotic SFV infection merits study because of the possible medical consequences for the affected individuals (6) and as a unique model to understand the emergence of simian retroviruses in the human population, an event with a major impact on public health (7).

The virological status of SFV-infected individuals is characterized by the persistence of replication-competent virus, the lack of major viral adaptation, the detection of SFV DNA in easily accessed body fluids (blood and saliva), and the absence of SFV RNA detection in samples positive for SFV DNA (5, 8–12). SFV-specific seropositivity is defined by a Gag-specific doublet in Western blots, with associated Bet-specific antibodies in some individuals (13, 14). We recently described the presence of high titers of SFV-specific neutralizing antibodies in most individuals infected with a zoonotic gorilla SFV (15). The three subunits of the SFV envelope (leader peptide, gp18LP; surface, gp80SU; and transmembrane, gp48™) are generated by cleavage of a precursor. They form heterotrimers assembled into trimeric spikes (16, 17). A 250-amino-acid genotype-specific region located in gp80SU is targeted by neutralizing antibodies (15).

Antibodies that target immunodominant and conserved epitopes from viral proteins are frequently detected in human plasma samples (18). The identification of such epitopes provides relevant information for the study of viral infections. First, the epitopes may be targeted by antibodies with neutralizing or other antiviral activity. Second, they may be included in assays for the diagnosis and/or titration of virus-specific antibodies. Third, virus-specific antibodies are systemic biomarkers of viral protein expression that may have occurred at any site in the body and at any time since primary infection.

The quantification of virus-specific antibodies is very useful in the context of poorly described infections and when blood sampling is limited by major logistical issues. This is true for studies conducted in humans exposed to SFV who live in remote areas of Africa or Asia (1, 2). No B-cell epitope has yet been described following infection with SFV. Here, we report the presence of an immunodominant epitope located in the extracellular portion of the SFV envelope gp18LP, recognized in ELISAs by plasma samples from Central African hunters infected with SFV. We precisely defined the amino acids involved in such recognition, quantified the titer and breadth of the antibodies, and searched for associations with major characteristics of SFV infection in humans such as SFV DNA levels and duration of infection (6, 15).

RESULTS

Peptide N96-V110 from the SFV envelope is frequently recognized by plasma samples from SFV-infected individuals.

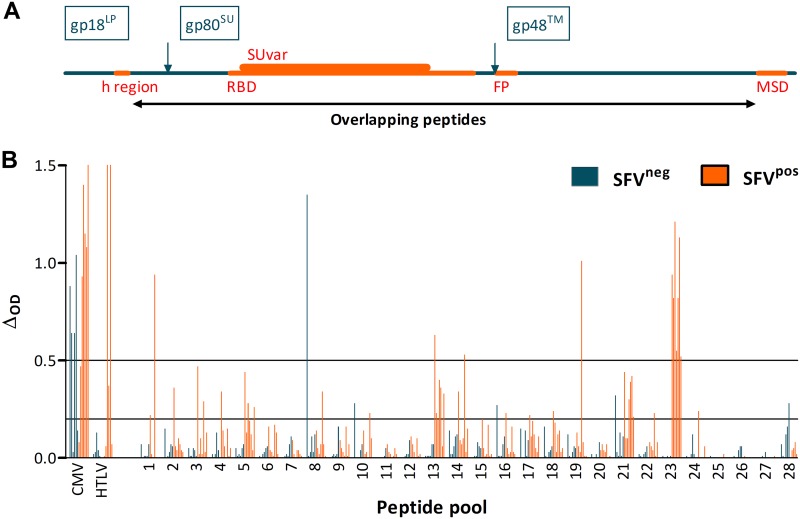

A peptide library covering the external portion of the chimpanzee SFV envelope (SFVpsc_huPFV isolate) was divided into 28 pools. We screened the pools by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for recognition by plasma samples from individuals chronically infected with a chimpanzee SFV (n = 2) or gorilla SFV (n = 5) and six uninfected hunters living in the same villages (Table 1). Ten of the thirteen samples displayed strong reactivity (ΔOD > 0.5) to cytomegalovirus (CMV). The three individuals who were seropositive by diagnostic anti-HTLV-1/2 Western blots reacted with the human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1) peptide in ELISAs, whereas seronegative samples tested negative by ELISA. Thus, samples tested against control peptides reacted with the expected specificity. The seven samples from SFV-infected individuals had strong reactivity to pool 23, whereas no control samples reacted with this pool (Fig. 1). Samples from three SFV-infected individuals and one control had strong reactivity to one or more additional peptide pools (pools 1, 8, 13, 14, or 19). Samples from SFV-infected (n = 21 pools recognized by six samples) and control individuals (n = 5 pools recognized by two samples) showed moderate reactivity (0.2 < ΔOD ≤ 0.5).

TABLE 1.

Study participants

| SFV status | Ethnic group | Code | Country | Sex | Age (yr) | Duration of infection (yr) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uninfecteda | Bantus | AKO255 | Cameroon | M | 43 | |

| BAD19 | Cameroon | M | 44 | |||

| BAD449 | Cameroon | M | 36 | |||

| BAD459 | Cameroon | M | 36 | |||

| BAD552 | Cameroon | M | 40 | |||

| BAD554 | Cameroon | M | 22 | |||

| Pygmies | BAK141 | Cameroon | M | 52 | ||

| BAK165 | Cameroon | M | 58 | |||

| BAK279 | Cameroon | M | 49 | |||

| BAK281 | Cameroon | M | 27 | |||

| BOBAK26 | Cameroon | M | 37 | |||

| BOBAK42 | Cameroon | M | 33 | |||

| CEBAK235 | Cameroon | M | 59 | |||

| CEBAK82 | Cameroon | M | 58 | |||

| MEBAK189 | Cameroon | M | 52 | |||

| MEBAK194 | Cameroon | M | 25 | |||

| Gorilla SFVb | Bantus | BAD348 | Cameroon | M | 33 | 14 |

| BAD447 | Cameroon | M | 61 | 21 | ||

| BAD448 | Cameroon | M | 53 | 9 | ||

| BAD456 | Cameroon | M | 35 | 13 | ||

| BAD463 | Cameroon | M | 44 | 7 | ||

| BAD468 | Cameroon | M | 35 | 12 | ||

| BAD551 | Cameroon | M | 41 | 14 | ||

| Pygmies | BAK132 | Cameroon | M | 67 | 37 | |

| BAK133 | Cameroon | M | 51 | 21 | ||

| BAK177 | Cameroon | M | 41 | 15 | ||

| BAK228 | Cameroon | M | 70 | 40 | ||

| BAK232 | Cameroon | M | 60 | 20 | ||

| BAK235 | Cameroon | M | 55 | 28 | ||

| BAK300 | Cameroon | M | 31 | 1 | ||

| BAK33 | Cameroon | M | 45 | 21 | ||

| BAK40 | Cameroon | M | 42 | 12 | ||

| BAK55 | Cameroon | M | 68 | 38 | ||

| BAK56 | Cameroon | M | 73 | 33 | ||

| BAK74 | Cameroon | M | 47 | 21 | ||

| BOBAK153 | Cameroon | M | 68 | 15 | ||

| LOBAK2 | Cameroon | M | 57 | 27 | ||

| Chimpanzee SFV | Bantus | AG15 | Cameroon | M | 71 | 43 |

| BAD316 | Cameroon | M | 51 | 15 | ||

| BAD327 | Cameroon | M | 33 | 3 | ||

| H3GAB56 | Gabon | M | 48 | 1 | ||

| H4GAB56 | Gabon | M | 51 | 1 | ||

| Pygmies | CH66 | Cameroon | M | 60 | 4 | |

| PYL106 | Cameroon | M | 60 | 45 | ||

| PYL149 | Cameroon | M | 60 | 15 | ||

| Cercopithecus SFV | Bantus | AG16 | Cameroon | M | 43 | 20 |

| AKO254 | Cameroon | F | 70 | − | ||

| BAD436 | Cameroon | M | 56 | 21 | ||

| BAD50 | Cameroon | M | 60 | 4 | ||

| CAMVAE3 | Cameroon | M | 29 | 4 | ||

| H14GAB34 | Gabon | M | 73 | 40 |

Plasma samples from six individuals were used for the initial screening, as presented in Fig. 1, and 10 other samples were used to assess the specificity of peptide N96-V110 recognition, as described in the text.

FIG 1.

Reactivity of plasma samples from SFV-uninfected and SFV-infected individuals to peptide pools covering the external portion of the chimpanzee SFV envelope. (A) Scheme of the organization of the SFV envelope protein. The amino acid positions are those of the SFVpsc_huPFV strain. The 988-residue envelope precursor is cleaved by furins (arrows) into the leader peptide (gp18LP, aa 1 to 126), surface protein (gp80SU, aa 127 to 571), and transmembrane protein (gp48™, aa 572 to 988). The hydrophobic region (h region, aa 68 to 84), receptor binding domain (RBD, aa 225 to 555), genotype-specific variable region (SUvar, aa 241 to 491), fusion peptide (FP, aa 572 to 598), and membrane-spanning domain (MSD, aa 939 to 975) are drawn in orange. The black line indicates the region covered by the overlapping peptides. (B) Binding of 1:200-diluted plasma samples of six SFV-uninfected (AKO255, BAD19, BAD449, BAD459, BAD552, and BAK165) and seven SFV-infected individuals (SFVggo: BAD448, BAD468, BAK74, BAK133, and LOBAK2; SFVptr: BD327 and PYL106) to 28 peptide pools was quantified by ELISA. Peptides from CMV and HTLV-1 were used as controls. ΔOD, defined as the difference between the OD of peptide-coated wells and diluent-treated wells, is presented. Bars at ΔOD of 0.2 and 0.5 indicate values used to identify samples with high or moderate seroreactivity, as described in the text.

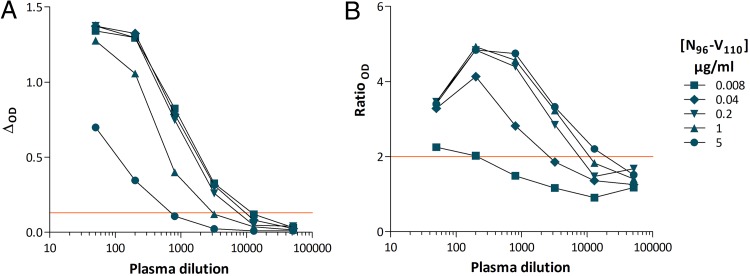

We focused on the frequent, high level, and SFV-specific reactivity to pool 23 (Fig. 1B). Peptides from pool 23 were tested individually for recognition by the five samples from gorilla SFV-infected hunters. All samples reacted with a single peptide: 96NKDIQVLGPVIDWNV110 (N96-V110). The specificity of the antibody-peptide interaction was confirmed by cross-titration of peptides and plasma samples: six serial dilutions (1:50 to 1:51,200) of the plasma sample from individual BAD468 were tested for binding to peptide N96-V110 coated at five concentrations (5 to 0.008 μg/ml). The ΔOD and ratioOD were maximal for peptide concentrations between 0.2 and 5 μg/ml and lower, but above threshold, at 0.04 μg/ml (Fig. 2). We detected antibody binding at plasma dilutions of 1:3,200 and below (Fig. 2). At the lowest plasma dilution (1:50), nonspecific binding led to a lower ratioOD than at higher dilutions (Fig. 2B). This result and those of additional titration experiments (not shown) established a sample dilution of 1:200 and peptide concentration of 1 μg/ml for optimal screening of plasma samples against peptide N96-V110.

FIG 2.

Plasma sample and peptide N96-V110 titration shows the specificity of recognition. Six dilutions (1:50 to 1:51,200) of the plasma sample from individual BAD468 were tested for binding to peptide N96-V110 coated at five concentrations (5 to 0.008 μg/ml). The ΔOD (A) and ratioOD (B) are shown on the graph. Red lines indicate positivity thresholds (ΔOD ≥ 0.13; ratioOD ≥ 2).

We confirmed the specificity of peptide N96-V110 recognition by testing additional samples. The peptide was recognized by 11 of 13 samples from gorilla SFV-infected individuals and none of the samples from 10 uninfected controls. In conclusion, we showed that peptide N96-V110 contains a B-cell epitope recognized by plasma antibodies from most humans infected with a zoonotic gorilla SFV.

Reactivity to peptide N96-V110: fine mapping of the epitope using truncated and alanine substitution variants.

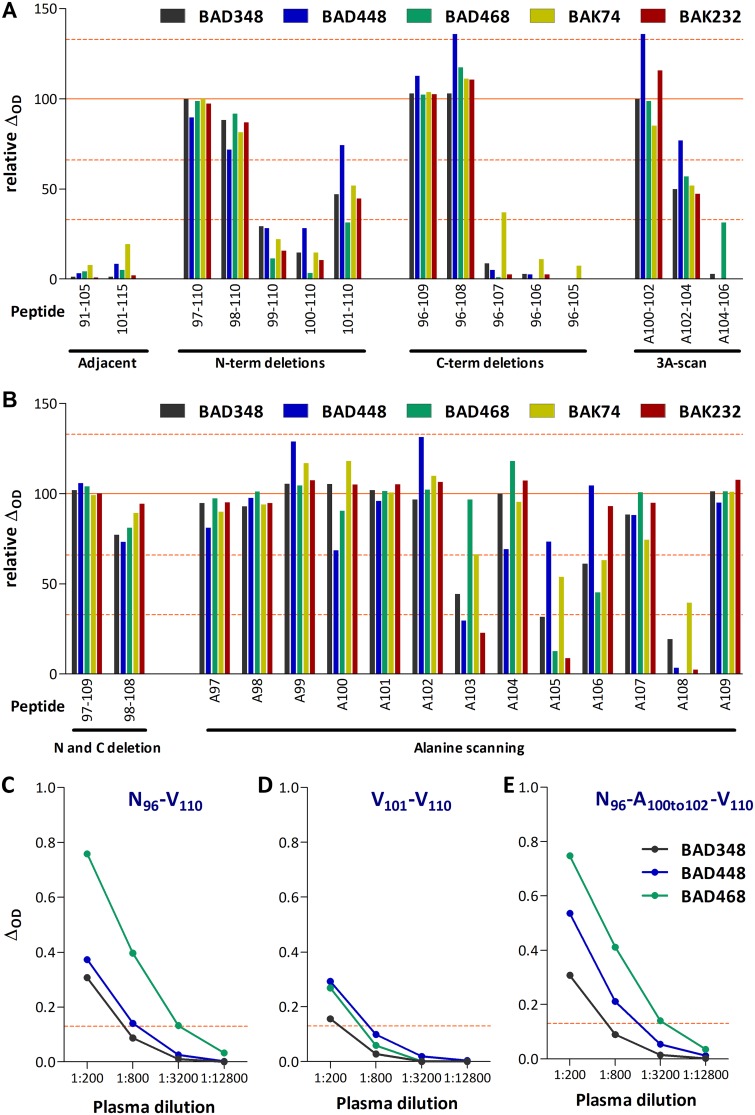

We then sought to identify the B-cell epitope contained in peptide N96-V110. The recognition of modified peptides was assessed by ELISA, and the results are expressed as percentages using peptide N96-V110 as the reference (Table 2). No sample recognized the adjacent peptides, S91-V105 and V101-V115, used for screening. We therefore designed a first peptide set to test whether sequential N-term and C-term deletions and triple alanine mutations in the center of the peptide affected the binding of plasma antibodies. Residues N96, K97, N109, and V110 were dispensable for peptide recognition (Fig. 3A). Alanine substitution of the Q100V101L102 or L102G103P104 stretches had a modest or intermediate impact on peptide recognition, respectively, whereas substitution of the P104V105I106 stretch abolished recognition.

TABLE 2.

Peptides and their recognition by samples from gorilla SFV-infected individualsd

ELISA results were classified as negative (light blue); positive with relative values of <66% (gold), 66 to <133% (red), and ≥133% (brown); and not tested (gray).

Sequences from most macaque SFV strains correspond to peptide N96-A100-V110, which was included in mapping set 2.

N96-V110 refers to the peptide with the SFVptr-huPFV sequence.

Peptides with sequences from other SFVs are named with a three-letter code (pve, mac…) if a single sequence is shared by all members from a SFV species (e.g., ppy) or if identical sequences are found in all or most isolates (e.g., pve and mac). The strain name was added for unique sequences (e.g., ggo_huBAK82). Abbreviations are as reported in a recent taxonomy and nomenclature report (19).

FIG 3.

Mapping of amino acids involved in plasma sample binding to peptide N96-V110. Plasma samples from five SFV-infected individuals were tested for binding to peptide N96-V110 and its variants (Table 2). Wells coated with peptide N96-V110 provided the reference value. Relative binding was calculated for wells coated with variant peptides and is expressed as the percentage of the reference value. Bars indicate 33, 66, 100, and 133% levels. For each peptide, the position of the first and last amino acids or the position of the amino acid replaced by an alanine are indicated on the graph. (A) The first peptide set comprised the two 15mers adjacent to peptide N96-V110, ten N- and C-terminal truncated variants, and three peptides in which three consecutive amino acids were replaced by an alanine. (B) The second peptide set comprised peptides with combined N- and C-terminal deletions and single alanine mutations. (C to E) Plasma samples from individuals BAD348 (gray symbols), BAD448 (blue), and BAD468 (green) were titrated for the recognition of peptides N96-V110 (C), V101-V110 (D), and N96-A100to102-V110 (E), coated at 1 μg/ml. The ΔOD values are presented as a function of sample dilution, and the red lines indicate the positivity threshold (ΔOD ≥ 0.13).

We tested a second set of mutated peptides to confirm and refine our results (Fig. 3B). Peptides K97-N109, D98-W108, N96-A97-V110, and N96-A109-V110 were recognized almost as efficiently as the reference peptide N96-V110, confirming that the antigenic region is within peptide D98-W108. W108 had the strongest impact on recognition, since its substitution to alanine abolished recognition by all samples. G103, V105, and I106 had a strong impact on recognition by some, but not all, plasma samples. Deletion of D98 or both D98 and I99 abolished peptide recognition (Fig. 3A), whereas their substitution to A had no effect on plasma antibody binding (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, alanine substitution of Q100 had no effect on binding (Fig. 3B) and peptide V101-V110 was better recognized than peptide Q100-V110. These results suggest that amino acids (aa) D98, I99, and Q100 may affect antibody binding through modification of the peptide’s conformation. We observed mutations that led to increased binding of modest magnitude (relative ΔOD between 133 and 150%) for a single sample. The testing of additional sample dilutions (Fig. 3C to E), as well as samples from four additional individuals (BAD447, BAD456, BAK33, and BAK55; Table 2), confirmed high interindividual variability in the recognition of peptides modified at positions 103, 105, and 106. In conclusion, peptide N96-V110 contains a B-cell epitope located between aa D98 and W108 with six essential positions (in boldface) and five positions tolerant to changes (in small capitals): 96 NKDI qvlG pVI dW NV110.

Reactivity of plasma samples from gorilla SFV-infected humans to naturally occurring variants of peptide N96-V110.

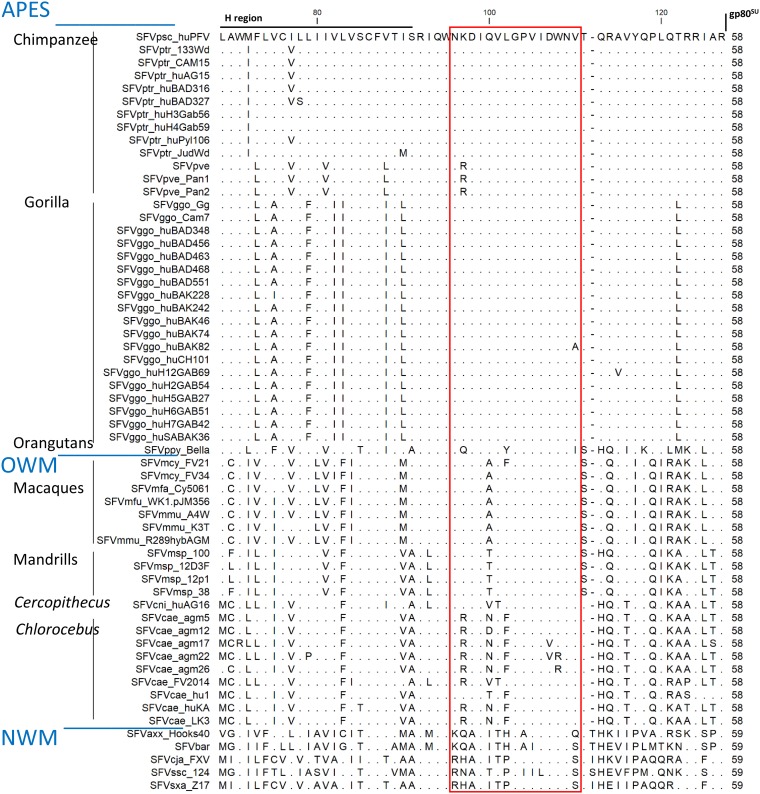

(i) Sequence alignments. We next assessed whether naturally occurring differences in sequence affect plasma binding. We aligned the envelope sequences from known SFV isolates (Fig. 4 shows all isolates and Table 2 those for which a peptide was tested; rules for NHP and SFV species names are described reference 19). N96-V110 sequences were well conserved across 33 ape SFV strains (Fig. 4), with the presence of two conservative (K97R, shared by SFV isolates from Pt verus and V110I in SFVppy) and two nonconservative changes (L102Y in SFVppy and V110A in SFVggo-huBAK82). Comparison of the ape SFVs showed the 21 OWM SFVs to share the K/R polymorphism and to differ mostly at positions 100 to 102. All macaque SFVs harbored the nonconservative Q100A change, and only one strain had an additional conservative change (SFVmcy_FV21, L102F). Mandrill SFVs shared the conservative Q100T change. Most Chlorocebus and the Cercopithecus SFVs shared the conservative K97R, V101T, and/or L102F changes and were polymorphic at position 100, where N, V, T, or D replaced Q100. Three Chlorocebus aethiops (African green monkeys) SFV strains had nonconservative D107V and/or W108R changes, and these were the only SFV strains with variability at positions shown to be important for plasma antibody binding. The five NWM SFVs differed mostly in the N-terminal half of peptide N96-V110 and at position 110. Comparison of the ape SFVs showed the NWM SFV sequences to be identical or harbor conservative changes at five of the six essential positions (99, 103, 105, 106, and 108).

FIG 4.

Alignment of the C-terminal gp18LP protein sequences from SFV. The gp18LP protein sequences extending from the hydrophobic region to the gp18LP/gp80SU cleavage site were aligned. We included all sequences from our previous envelope analysis (20) and those published and/or deposited in GenBank since SFVsxa_Z17 (KP143760.1), SFVmfa_Cy5061 (LC094267.1), SFVmmu_K3T (MF280817.1), SFVcae_FV214 (MF582544.1), SFVbar (MH368762.1), SFVmsp_100 (MK014759), SFVmsp_12D3F (MK014758), SFVmsp_12p1 (MK014761), and SFVmsp_38 (MK014760). Identical residues are indicated by dots. The red square highlights the N96-V110 sequence. The sequences are ordered according to the phylogeny of host species and within each species in alphabetical order.

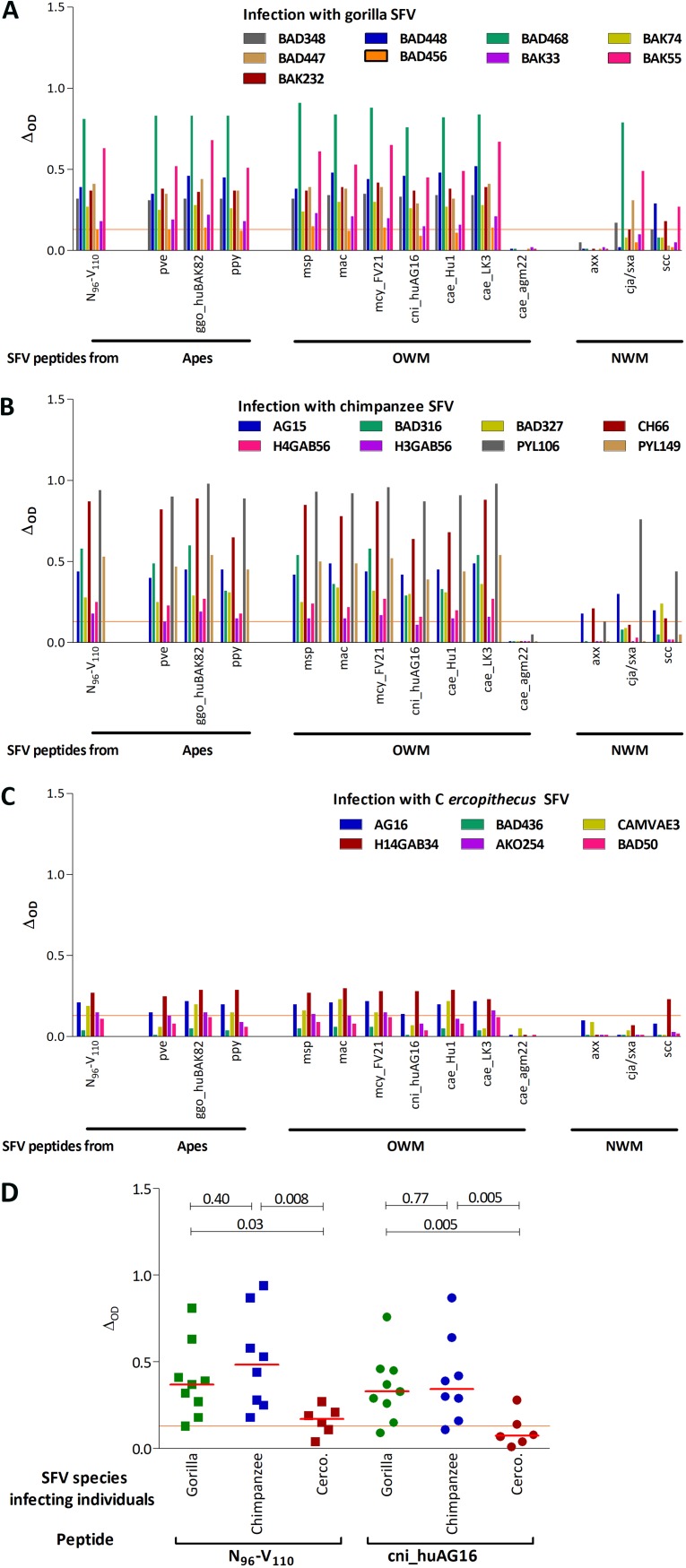

(ii) Most variant peptides from apes and OWM SFV are recognized by plasma samples. Thirteen new peptides corresponding to major SFV species were synthesized and tested for their recognition by samples from individuals infected with gorilla (n = 9, Fig. 5A), chimpanzee (n = 8, Fig. 5B), or Cercopithecus SFV (n = 6, Fig. 5C). All but two samples, both from Cercopithecus SFV-infected individuals, recognized peptide N96-V110 and most of its naturally occurring variants. Binding magnitudes were similar for peptide N96-V110, the three peptides from apes SFV (pve, ggo_huBAK82, ppy), and six of the seven peptides from OWM SFV (msp, mac, mcy_FV21, cni, cae-hu1, and cae-LK3). The three peptides from NWM SFV strains (axx, cja/sxa, and ssc) were recognized by two to eight plasma samples, with high interindividual variability. The peptide from SFVcae_agm22 harbored two nonconservative changes, D107V and W108R, and was not recognized by any of the tested samples.

FIG 5.

Recognition of variant peptides by plasma samples from SFV-infected individuals. Plasma samples from SFV-infected individuals were tested for binding to peptide N96-V110 and its naturally occurring variants. The ΔOD is presented for peptide N96-V110 and 13 peptides with sequences found in SFV from apes, OWM, and NWM. The peptide sequences are presented in Table 2. (A to C) Plasma samples were obtained from Cameroonian hunters infected with gorilla (A, n = 9), chimpanzee (B, n = 8), or Cercopithecus (C, n = 6) SFV. (D) The ΔOD are presented for peptide N96-V110, of which the sequence is found in most chimpanzee and gorilla SFV strains circulating in Cameroon and the Cercopithecus SFV cni_huAG16 strain obtained from a Cameroonian hunter (9). Plasma samples were obtained from Cameroonian hunters infected with gorilla (green symbols), chimpanzee (blue), or Cercopithecus (brown) SFV. Bars represent the median values and red lines the positivity threshold (ΔOD ≥ 0.13). P values from the Wilcoxon signed-rank test are shown.

(iii) Infection with an ape SFV is associated with higher binding magnitude to peptide N96-V110. We then compared the magnitude of binding, defined as the ΔOD, to two peptides: peptide N96-V110, whose sequence is found in most gorilla and chimpanzee SFVs, and peptide cni_huAG16, with a sequence from a zoonotic Cercopithecus SFV (9). Samples from gorilla or chimpanzee SFV-infected individuals had a significantly higher magnitude of binding against both peptides than those from Cercopithecus SFV-infected individuals (Fig. 5D). Importantly, the level of binding to peptides N96-V110 and cni_huAG16 (Fig. 5D) was similar and species dependent. Our data show that individuals infected with an ape SFV generated higher levels of antibodies that bind the N96-V110 epitope than those infected with an OWM SFV strain.

Recognition of peptide N96-V110: binding magnitude, plasma titers, avidity, and breadth are strongly correlated.

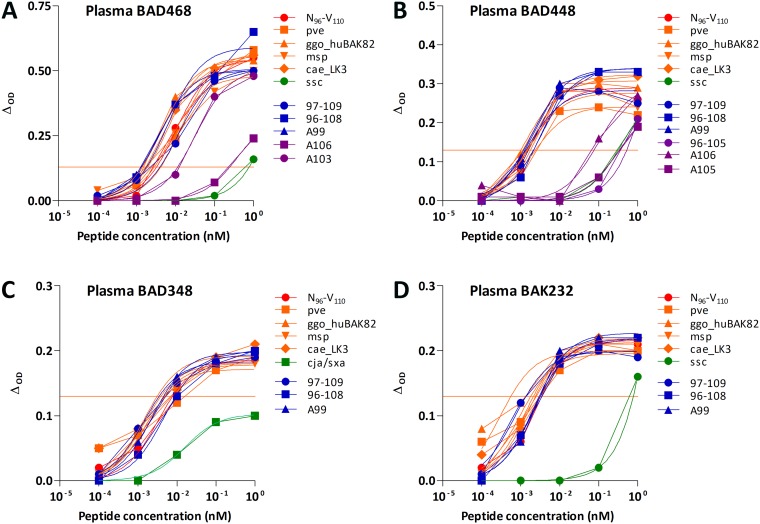

Several plasma samples had slightly lower or higher reactivities to the variant peptides than peptide N96-V110 at high peptide concentrations. We thus sought a subtler impact of amino acid changes by determining the 50% effective concentration (EC50) of peptides from SFV viruses circulating in Africa (pve, ggo_huBAK82, msp., and cae_LK3), truncated and mutated peptides with equivalent or possibly better recognition, and those that are rarely recognized. For the four plasma samples, the highest avidities were observed for peptides recognized with the highest binding magnitudes (Fig. 6). Responses to peptide N96-V110 and other frequently recognized peptides were homogeneous: for a given plasma sample, the avidities varied by <10-fold and <20-fold for a given peptide. The avidities were generally lower (>100 pM) for peptides recognized by a small number of samples.

FIG 6.

Avidity of plasma antibodies for peptide N96-V110 and its variants. Plasma samples from the individuals BAD468 (A), BAD448 (B), BAD348 (C), and BAK232 (D) were tested at a 1:200 dilution for the recognition of serial dilutions of peptide N96-V110 (red symbols), apes and OWM SFV variants (pve, ggo_huBAK82 and msp., cae_LK3; orange symbols), NWM variants (ssc and cja/sxa; green symbols), frequently recognized mutated peptides (K97-N109, N96-W108, and N96-A99-V110; blue symbols), and rarely recognized mutated peptides (N96-V105, N96-A103-V110, N96-A105-V110, and N96-A106-V110; purple symbols). The peptide sequences are presented in Table 2. For each sample, the titration was performed for reactive peptides only (Fig. 3 and 5). The nonlinear three-parameter regression lines are shown. Red lines indicate the positivity threshold (ΔOD ≥ 0.13).

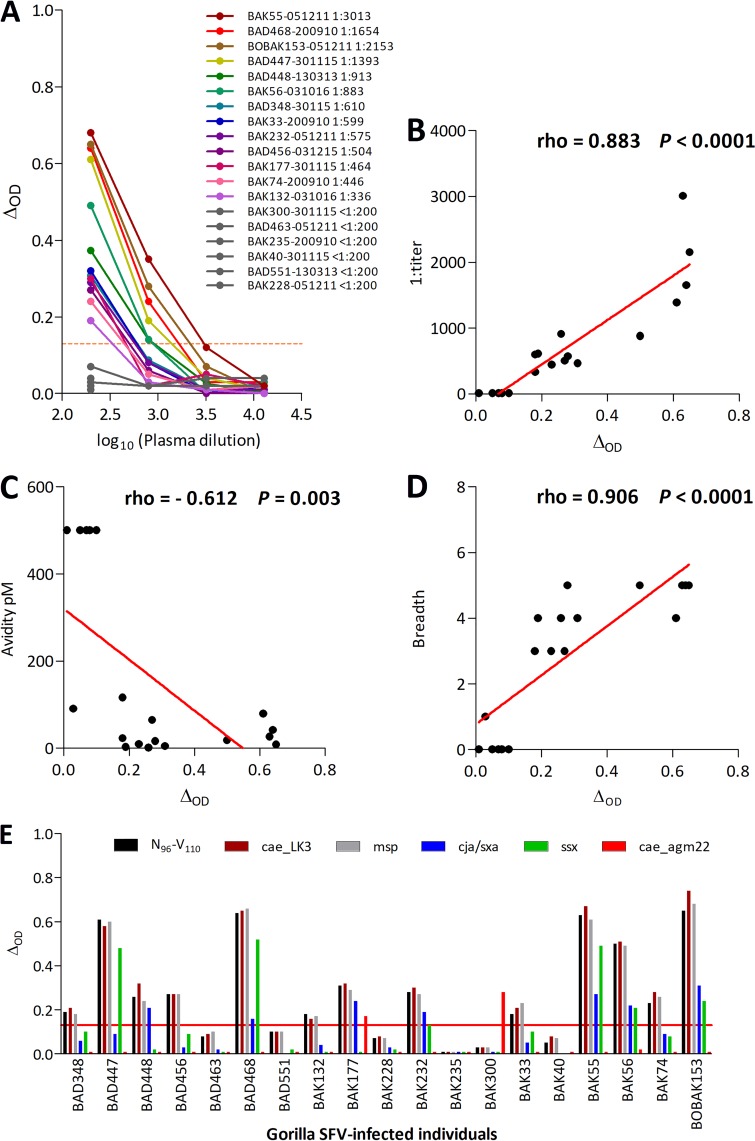

Samples were available for 19 gorilla SFV-infected individuals to assess several parameters of plasma antibody binding to peptide N96-V110 (Fig. 7A to D). The binding magnitude was defined as the ΔOD for a plasma dilution of 1:200 and a peptide concentration of 1 nM. It ranged from 0.01 to 0.65 (median [interquartile range], 0.23 [0.08-0.50]). Plasma antibody titers ranged from <1:200 to 1:3,013 (540 [<1:200-1,033]), and plasma avidities for peptide N96-V110 ranged from 1.9 to >500 pM (42 [10; >500]). There was high interindividual variability in the recognition of variant peptides. We therefore assessed the breadth of the response, defined by the number of peptides recognized out of the six tested (N96-V110, cae_LK3, msp., cae_agm22, cja/sxa, and ssc; Fig. 7E). The breadth ranged from 0 to 5 peptides (3 [0 to 5]). The binding magnitude strongly correlated with the titer, avidity, and breath (Fig. 7B to D).

FIG 7.

The binding magnitude of peptide N96-V110 is strongly correlated with titer, avidity, and breadth. (A) Fourfold dilutions (1:200 to 1:12,800) of plasma samples from 19 gorilla SFV-infected hunters were tested for binding to peptide N96-V110 (1 nM). The ΔOD is presented as a function of plasma dilution (log10 transformed). Plasma sample titers were defined as the inverse of the plasma dilution required to achieve the positivity threshold, as described in Materials and Methods. Titers (B), avidity (C), and breadth (D) are presented as a function of binding magnitude for plasma samples from the 19 SFV-infected individuals presented in panel A. (E) Binding magnitude of the samples from 19 gorilla SFV-infected individuals to six peptides (N96-V110, msp., cae_LK3, cja/sxa, ssx, and cae_agm22). The peptide concentration was 1 nM, and the plasma dilution was 1:200. In panels A and E, the ΔOD is presented, and the red line indicates the positivity threshold (ΔOD ≥ 0.13).

The plasma of one gorilla SFV-infected hunter reacts with the variant Chlorocebus peptide while failing to bind to the reference peptide.

Among the 19 gorilla SFV-infected individuals, two had samples that reacted with the cae_agm22 peptide (Fig. 7E), which harbors two nonconservative changes, D107V and W108R. The sample from individual BAK300 recognized only this variant, whereas the sample from individual BAK177 reacted against cae_agm22 and four other peptides. A nested PCR was performed on buffy-coat DNA from these two individuals, using previously published protocol and primers (20). The SFV env gene amplified from the blood cells from both BAK177 and BAK300 encoded the reference 96NKDIQVLGPVIDWNV110 sequence. Neither BAK300 nor BAK177 reported contact with Chlorocebus. They lived in a rainforest area of South Cameroon, whereas Chlorecebus inhabits the savanna in central and north Cameroon. We also performed a blast search and found no significant sequence homology with other pathogens or host proteins that would support antigenic mimicry as the mechanism underlying the unexpected reactivity against the cae_agm22 peptide.

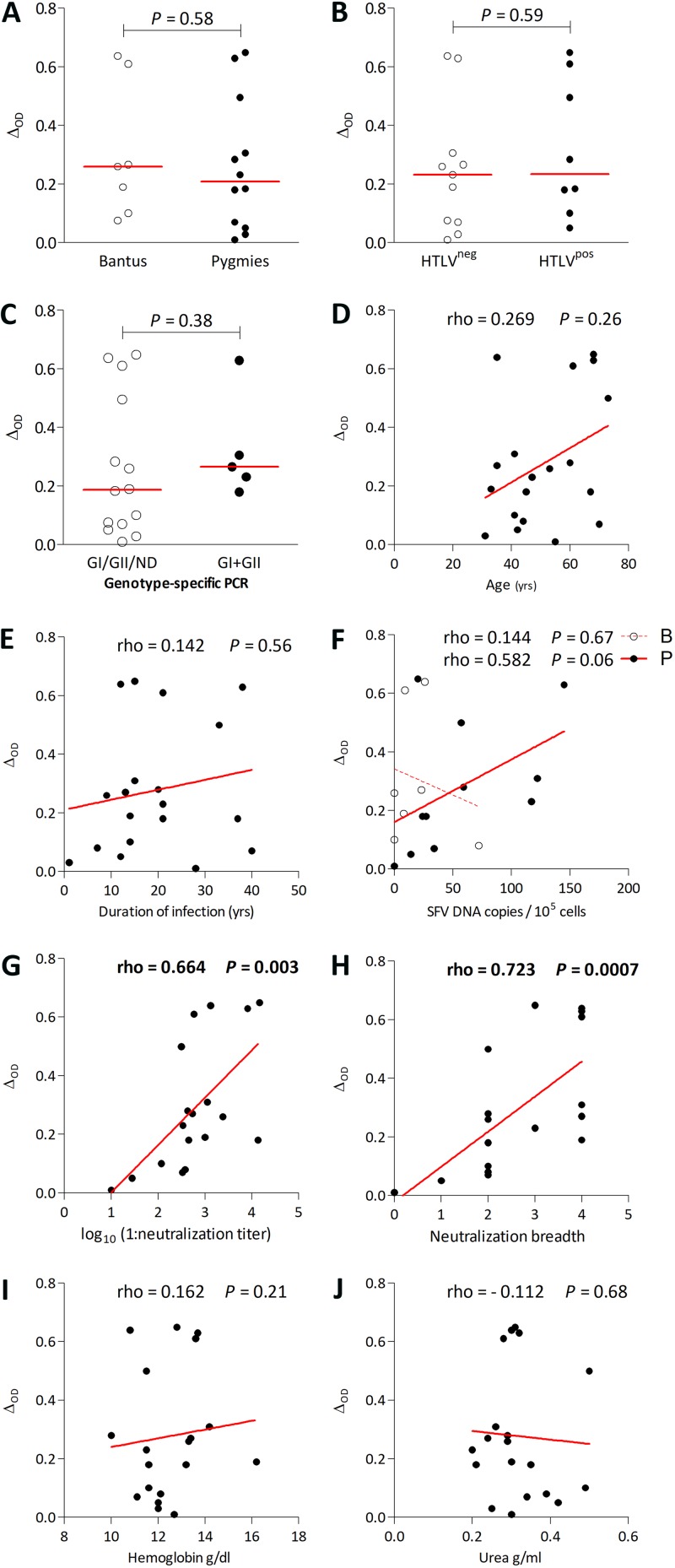

Recognition of peptide N96-V110 by samples from gorilla SFV-infected individuals: association with infection parameters.

We next assessed whether plasma recognition of peptide N96-V110 is associated with parameters of SFV infection, using data from the 19 gorilla SFV-infected individuals. For each sample, we considered the most highly recognized peptide (peptide N96-V110 for all individuals, except BAK300, who recognized peptide cae_agm22). The binding magnitude to peptide N96-V110 was similar for Bantus and Pygmies and for HTLV-1-infected and uninfected individuals (Fig. 8A and B). Two gorilla SFV genotypes that differ mostly in the central region of the env gene infect humans and NHPs (20), and we recently described coinfection by strains from the two genotypes (15). Binding magnitude to peptide N96-V110 did not differ between individuals found to be infected with one or two SFV genotypes (Fig. 8C). Binding magnitude was not correlated with age or the duration of infection but tended to be correlated with SFV DNA in Pygmies (Fig. 8D to F). We previously performed neutralization assays against each of the two genotypes from gorilla and chimpanzee SFV (SFVggo_huBAD468, SFVggo_huBAK74, SFVpsc_huHSRV.13 (prototype foamy virus [PFV]), and SFVpve_Pan2 [SFV7]) using a BHK-21-derived indicator cell line (15). Binding magnitude to peptide N96-V110 strongly correlated with neutralization titers and breadth quantified on the same plasma samples (Fig. 8G and H). Overall, the magnitude of the antibody response to peptide N96-V110, located in the gp18LP, correlates with the magnitude of neutralizing antibodies that target the gp80SU; thus, the two antibody responses have distinct specificities, but their levels correlate. There was no association between binding magnitude and hemoglobin or urea levels (Fig. 8I and J) or hematological parameters previously reported to be significantly different between SFV-infected individuals and matched controls (6). We obtained similar results when considering plasma titer, avidity, or breadth (data not shown). Overall, binding to peptide N96-V110 by plasma samples was not statistically associated with demographic or infection-related variables except neutralization titers.

FIG 8.

Plasma sample binding to peptide N96-V110 is correlated with neutralization magnitude and breadth, and the binding magnitude of plasma samples to peptide N96-V110 is presented according to ethnicity (A), to HTLV-1 infection (B), and to the number of viral genotypes detected with a genotype-specific PCR (15) (C). Mann-Whitney P values are shown above the graphs. The binding magnitude to peptide N96-V110 is presented as a function of age (D), duration of infection (E), SFV DNA levels in blood cells for the two ethnic groups (F), neutralization titer (G), neutralization breadth (H), hemoglobin level (I), and urea level (J). The lines represent the linear regression curves. Results from Spearman tests are indicated on the graphs, and statistically significant results are shown in boldface.

DISCUSSION

Here, we identified an immunodominant and conserved B-cell epitope in the SFV gp18LP envelope subunit, recognized by plasma samples drawn from SFV-infected Central African hunters. The peptide N96-V110 contains the first B-cell epitope described after infection with SFV. The same region of the feline FV (FFV) envelope is recognized by cat antibodies (21), showing that the short external portion of gp18LP is an evolutionary conserved antigenic site. Plasma samples from individuals infected with gorilla and chimpanzee SFV displayed frequent and broad cross-recognition of naturally occurring variant sequences of apes and OWM SFV. However, there was high interindividual variability in cross-recognition of the most distant sequences from NWM and a Chlorocebus SFV strain. The magnitude of plasma antibody binding to peptide N96-V110 was strongly dependent on the SFV species infecting the individuals.

Our primary goal was to identify B-cell epitopes with conserved sequences for their subsequent use in studies of SFV-infected humans. We therefore extensively characterized the amino acids involved in binding by plasma antibodies and the recognition of various SFV strains. First, we defined six essential amino acids, using truncated and alanine variants, and proposed a putative binding motif 96 NKDI qvlG pVI dW NV110. Second, we observed that amino acid changes in apes and OWM SFV sequences are located at positions found to have a minor impact on recognition by plasma samples. Third, we observed a major exception, i.e., the W108R change in some Chlorocebus SFV strains (22). Systematic testing of plasma samples revealed rare recognition of peptide cae_agm22 by samples from two gorilla SFV-infected individuals, leading to modification of the putative binding motif to 96 NKDI qvlG pVI d/ vW/R NV110. A single SFV-infected individual exclusively recognized peptide N96-V110-cae_agm22, whereas 31 recognized peptide N96-V110. All SFV sequences from Central African hunters and NHPs had a W at position 108 (9, 20), including the two individuals whose plasma samples reacted with peptide cae_agm22. We cannot exclude the presence of gorilla SFV quasispecies carrying a W108R change in body compartments other than blood or their circulation prior to sampling. However, SFV sequences are known to be very stable (22). Coinfection with a Chlorocebus SFV is very unlikely as this monkey species does not inhabit the South and East Cameroon. The three-dimensional molecular structure of the SFV envelope is currently unknown, precluding speculation on various antibody binding modes and contact sites. The recognition of peptide cae_agm22 may be the most striking example of interindividual variability in the interaction between antibodies and variant peptide N96-V110. For individual BAK300, the recognition of a variant sequence and lack of recognition of the autologous sequence is confusing. Since the autologous sequence is immunogenic in most studied individuals, the absence of reacting antibodies may reflect the lack of cells with adequate specificity among the naive B-cell repertoire of individual BAK300 (23). Alternatively, previously primed B cells cross-reacting with peptide cae_agm22 may have prevented the development of B cells that specifically react with the autologous peptide, a process called “original antigenic sin” (24). Overall, the detailed recognition pattern supports the wide use of peptide N96-V110 and a limited set of its variants to detect specific B-cell responses in humans infected with strains from apes and OWM.

We had the opportunity to test serological reactivities of individuals infected with three different SFV species (gorilla, chimpanzee, and Cercopithecus). The binding magnitude to peptide N96-V110 was lower for individuals infected with Cercopithecus SFV than for those infected with a gorilla or a chimpanzee SFV. The binding magnitude to naturally occurring sequence variants from apes and Cercopithecus was almost identical for all plasma samples. A direct relationship between viral load and the level of the antibody response is frequently observed among individuals chronically infected with HIV-1 or HTLV-1 (25–30). Thus, the lower antibody response to Cercopithecus SFV than to ape SFV in humans may be indirect evidence for lower replication levels of Cercopithecus SFV during either the primary or the chronic phase of the infection. This is consistent with lower rates of SFV DNA detection in individuals infected with macaque SFV than for those infected with ape SFV and the absence of such DNA in humans infected with NWM SFV (3, 5, 12, 31). An alternative explanation could be lower immunogenicity of Cercopithecus SFV than that of ape SFV. Serological reactivity of naturally infected NHPs would be instrumental in answering this question. Biological relatedness between hosts may affect both the expression patterns of pathogens and the associated immune response. Indeed, humans share more pathogens with great apes than with other NHPs (32). Overall, the recognition of peptide N96-V110 may reflect the outcome of zoonotic infection by different SFV species.

We observed that the binding magnitude to peptide N96-V110 statistically correlated with neutralization titer and breadth. These antibodies target two different parts of the SFV envelope: the newly identified epitope is located in the gp18LP, whereas neutralization is mediated by antibodies that recognize the gp80SU (15). The correlation suggest that the immunogenicity of both envelope subunits is under the influence of the same viral and host factors.

There was no correlation between binding magnitude to peptide N96-V110 and ethnicity, age, or duration of infection. In Pygmies, the binding magnitude correlated with blood SFV DNA levels; in Bantus, the absence of such association could be explained by low and homogenous SFV DNA levels and a smaller number of tested individuals. In baboons, coinfection with STLV-1 is associated with higher blood SFV DNA levels (33). Here, we did not observed differences in binding magnitude between individuals infected or not with HLTV-1. Higher neutralization breadth was associated with higher hemoglobin and lower urea levels (15), which are two hematological parameters whose levels are significantly different between SFV-infected individuals and controls (6). We did not observe such association with binding to peptide N96-V110. The gorilla SFV-infected individuals were selected on the basis of available samples at the time the assays were performed (22 for neutralization and 19 for binding activity). Eighteen samples were included in both studies, ruling out a major effect of participant selection. Thus, their association with hematological parameters differed, despite the correlation of antibody measures obtained with the two assays. This may reflect the in vivo antiviral activity of neutralizing antibodies only.

We identified an epitope contained in a region previously reported to be frequently recognized by sera of FFV-infected cats and pumas (21, 34). Among the six putative essential positions in the SFV peptide (96 NKDI QVLG PVI DW NV110), four are identical with those of the FFV K94-V108 peptide (94 KEAI THPG PVL SWQV108), and one is conserved. However, with the present peptide set, we detected little reactivity to the transmembrane (gp48™) protein, in contrast to cat sera, which react with peptides located in the fusion peptide proximal region or membrane proximal external region (21, 34). FFV and SFV envelopes share some of their immunogenic and antigenic properties, as previously shown by genotype-specific neutralization (15, 35).

Low-resolution cryo-electron microscopy of the native envelope glycoprotein from chimpanzee SFV showed that the trimeric envelope glycoprotein inserted in the viral membrane is arranged in hexagonal assemblies (17). The spacers connecting the envelope trimers at the surfaces of virions are most likely composed of gp18LP and/or gp48™. Peptide N96-V110 may be part of this spacer. Indeed, this structure is probably accessible to antibodies and sequence conservation across SFV strains is consistent with structural constraints.

In conclusion, we report here the first identification of an immunodominant B-cell epitope in SFV. The in-depth characterization of viral sequence affecting its recognition by plasma antibodies demonstrated similar antigenicity across most SFV strains infecting OWM and apes. Characterization of the humoral response in infected NHPs would be helpful to substantiate our findings in humans, as shown for virological studies (12, 33, 36, 37). The stronger antibody response in humans infected by ape SFV species may be significant, since it suggests higher viral protein expression of these SFV species in their new human hosts.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population.

Blood samples were collected from adult populations living in villages and settlements across rural areas of the rainforest in Cameroon and Gabon (5, 6, 14, 38). Participants gave written informed consent. Ethics approval was obtained from the relevant national authorities in Cameroon (the Ministry of Health and the National Ethics Committee) and France (the Commission Nationale de l’Informatique et des Libertés (CNIL) and the Comité de Protection des Personnes Ile-de-France IV). SFV infection was diagnosed by a clearly positive Gag doublet on Western blots, using plasma samples from the participants, and amplification of the integrase gene and/or long terminal repeat DNA fragments by PCR, using cellular DNA isolated from blood buffy coats (5). The origin of the SFV was identified by phylogenetic analysis of the sequence of the integrase gene (5). Plasma samples from 51 participants were used for this study: 48 Cameroonians and 3 Gabonese (Table 1). Sixteen participants were not infected with SFV, eight were infected with chimpanzee SFV, 21 were infected with gorilla SFV, and 6 were infected with Cercopithecus SFV. All participants, but one, were male: 24 were Bantus, and 27 were Pygmies. Their median (interquartile range) age was 51 (39-60) years. The duration of infection was defined as the elapsed time between receiving the wound—as reported by the individual—and the sampling and was 15 (10-26) years. The parameters used to characterize SFV infection have been described in previous publications: blood SFV DNA levels were determined by quantitative PCR carried out on buffy coats from gorilla SFV-infected participants (5); blood tests were carried out at the Centre Pasteur du Cameroun in Yaoundé (6); SFV neutralization titer and breadth were quantified in plasma samples and mono and dual infections were determined by genotype-specific PCR of blood cell samples (15).

Peptides.

We designed 169 peptides of 15 aa, overlapping by 10 aa and covering the SFVpsc_huPFV envelope sequence expected to be exposed on the external portion of the viral particle between the hydrophobic region in gp18LP and the membrane-spanning domain in the transmembrane domain gp48™ (C86-L940; sequence based on GenBank accession number U21247; Fig. 1A). Peptides were synthesized by Gencust (Ellange, Luxemburg). Each peptide was solubilized according to the manufacturer’s instructions in H2O, methanol, dimethyl sulfoxide, 0.05 M carbonate-bicarbonate (pH 9.6) buffer (carbonate buffer), acetonitrile, or acetic acid. Peptide pools were designed according to their composition and solubility. Pools 1 to 22 contained 12 peptides distributed in a matrix design, with each peptide present in two pools (39). Six pools (pools 23 to 28) were designed to group acidic peptides displaying precipitation at neutral pH or to avoid inclusion of cysteine containing peptides in dimethyl sulfoxide containing pools. The last six pools contained 2 to 12 peptides, each present in a single pool. Peptides containing CMV and HTLV-1 immunodominant epitopes were used as positive controls: CETDDLDEEDTSIYLSPPPVPPVQVVAKRLPRPDTPRT from the pp28 CMV tegument protein, KSGTGPQPGSAGMGGAKTPSDAVQNILQKIEKIKNTEE from the pp150 CMV tegument protein, and INTEPSQLPPTAPPLLPHSNLDHI from HTLV-1 gp46 (40, 41). The synthesis of variant peptides was performed by Smartox SAS (Saint-Martin d’Hères, France) and GenScript (Hong Kong, China), and the peptides were solubilized in carbonate buffer.

ELISA.

Clear high-binding flat-bottom polystyrene 96-well microplates (R&D Systems, Lille, France) were coated overnight at 4°C with peptides diluted in carbonate buffer at a concentration of 1 μg/ml for each peptide. The plates were then washed (5 × 0.2 ml/well) with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) supplemented with 0.1% Tween 20 (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint-Quentin Fallavier, France). The plasma samples and reagents were diluted in PBS–0.1% Tween 20 supplemented with. 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA; R&D Systems), and incubations were performed at room temperature in a humidified box, unless otherwise stated. Free binding sites were blocked with PBS–0.1% Tween 20–1% BSA for at least 90 min, 1:200-diluted plasma samples were added, and the plates were incubated for 1 h, followed by incubation in horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-human IgG H+L (1:40,000; Jackson Immuno Research Europe, Ely, UK) for 1 h and then in 0.25 mg/ml o-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride in 0.05 M citrate buffer (pH 5) and 0.012% H2O2 for 30 min. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 1.8 M H2SO4 (vol/vol), and the absorbance was read at 493 nm. All samples were tested in duplicate, and the average optical density (OD) values were used. The peptide diluent was used as the negative control, and antibody binding to peptides was expressed as the difference (ΔOD) and the ratio (ratioOD) of the OD (ΔOD = ODtest – ODcontrol; ratioOD = ODtest/ODcontrol). Plasma samples from five SFV-uninfected individuals were tested for binding to peptide N96-V110 and 21 variant peptides. The means plus two standard deviations of the ΔOD and the ratioOD were 0.13 and 2.0, respectively. These values were used to define the dual cutoff criterion in the ELISA. Inclusion of the ratioOD in this composite cutoff avoids inadequate classification of plasma samples with high nonspecific reactivity.

Avidity was defined as the peptide concentration required to achieve 50% of the maximal effective reaction (EC50). The nonlinear three-parameter regression of ΔOD as a function of log10 peptide concentration was fitted with the least-squares method and used to calculate the EC50, with the constraint on background set to 0, using Prism 5 software (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA). The magnitude of the responses between plasma samples tested in different experiments were compared by normalizing the ΔOD to the values of reference plasma samples included in each assay. Plasma sample titers were defined as the inverse of the plasma dilution required to achieve the positivity threshold (ΔOD ≥ 0.13). We did not use the EC50 to define titers, since the maximal ΔOD could not be achieved at a 1:200 dilution for all samples.

Statistical analysis.

The binding magnitude of plasma samples to different peptides was compared using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. The Spearman rank test was used to assess correlations between binding magnitude and parameters that describe peptide recognition and those characterizing SFV infection. The Mann-Whitney test was used to compare binding magnitude to peptide N96-V110 between groups defined by ethnicity or mono/dual infection.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank M. Bourgine for her helpful advice on the ELISAs. We thank members of the Unité d’Épidémiologie et Physiopathologie des Virus Oncogènes for discussions and technical advice. The text has been edited by a native English speaker.

C.L. was personally supported by a doctoral grant from the French government program Investissement d’Avenir, Laboratory of Excellence, Integrative Biology of Emerging Infectious Diseases (LabEx IBEID). This study was supported by the Institut Pasteur in Paris, France, the Program Transversal de Recherche from the Institut Pasteur (PTR#437), and the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (grant ANR-10-LABX-62-IBEID; REEMFOAMY project, ANR 15-CE-15-0008-01). The funding agencies had no role in the study design, generation of results, or writing of the manuscript.

F.B. conceptualized and designed the study, acquired funding, and wrote the paper. C.L., D.B., and T.M. performed experiments. C.L., D.B., T.M., and F.B. validated and analyzed the data. E.B., A.M.-O., and R.J. supervised field work and provided resources. A.G. coordinated the field study and designed the study.

The authors had no conflicting interests relevant to the study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gessain A, Rua R, Betsem E, Turpin J, Mahieux R. 2013. HTLV-3/4 and simian foamy retroviruses in humans: discovery, epidemiology, cross-species transmission, and molecular virology. Virology 435:187–199. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2012.09.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pinto-Santini DM, Stenbak CR, Linial ML. 2017. Foamy virus zoonotic infections. Retrovirology 14:55. doi: 10.1186/s12977-017-0379-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stenbak CR, Craig KL, Ivanov SB, Wang X, Soliven KC, Jackson DL, Gutierrez GA, Engel G, Jones-Engel L, Linial ML. 2014. New World simian foamy virus infections in vivo and in vitro. J Virol 88:982–991. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03154-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muniz CP, Cavalcante LTF, Jia H, Zheng H, Tang S, Augusto AM, Pissinatti A, Fedullo LP, Santos AF, Soares MA, Switzer WM. 2017. Zoonotic infection of Brazilian primate workers with New World simian foamy virus. PLoS One 12:e0184502. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0184502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Betsem E, Rua R, Tortevoye P, Froment A, Gessain A. 2011. Frequent and recent human acquisition of simian foamy viruses through apes’ bites in Central Africa. PLoS Pathog 7:e1002306. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buseyne F, Betsem E, Montange T, Njouom R, Bilounga Ndongo C, Hermine O, Gessain A. 2018. Clinical signs and blood test results among humans infected with zoonotic simian foamy virus: a case-control study. J Infect Dis 218:144–151. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiy181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peeters M, D’Arc M, Delaporte E. 2014. Origin and diversity of human retroviruses. AIDS Rev 16:23–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boneva RS, Switzer WM, Spira TJ, Bhullar VB, Shanmugam V, Cong ME, Lam L, Heneine W, Folks TM, Chapman LE. 2007. Clinical and virological characterization of persistent human infection with simian foamy viruses. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 23:1330–1337. doi: 10.1089/aid.2007.0104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rua R, Betsem E, Calattini S, Saib A, Gessain A. 2012. Genetic characterization of simian foamy viruses infecting humans. J Virol 86:13350–13359. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01715-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rua R, Betsem E, Gessain A. 2013. Viral latency in blood and saliva of simian foamy virus-infected humans. PLoS One 8:e77072. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rua R, Betsem E, Montange T, Buseyne F, Gessain A. 2014. In vivo cellular tropism of gorilla simian foamy virus in blood of infected humans. J Virol 88:13429–13435. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01801-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Engel GA, Small CT, Soliven K, Feeroz MM, Wang X, Kamrul Hasan M, Oh G, Rabiul Alam SM, Craig KL, Jackson DL, Matsen Iv FA, Linial ML, Jones-Engel L. 2013. Zoonotic simian foamy virus in Bangladesh reflects diverse patterns of transmission and coinfection. Emerg Mic Infect 2:e58. doi: 10.1038/emi.2013.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cummins JE, Boneva RS, Switzer WM, Christensen LL, Sandstrom P, Heneine W, Chapman LE, Dezzutti CS. 2005. Mucosal and systemic antibody responses in humans infected with simian foamy virus. J Virol 79:13186–13189. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.20.13186-13189.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Calattini S, Betsem EBA, Froment A, Mauclere P, Tortevoye P, Schmitt C, Njouom R, Saib A, Gessain A. 2007. Simian foamy virus transmission from apes to humans, rural Cameroon. Emerg Infect Dis 13:1314–1320. doi: 10.3201/eid1309.061162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lambert C, Couteaudier M, Gouzil J, Richard L, Montange T, Betsem E, Rua R, Tobaly-Tapiero J, Lindemann D, Njouom R, Mouinga-Ondémé A, Gessain A, Buseyne F. 2018. Potent neutralizing antibodies in humans infected with zoonotic simian foamy viruses target conserved epitopes located in the dimorphic domain of the surface envelope protein. PLoS Pathog 14:e1007293. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilk T, de Haas F, Wagner A, Rutten T, Fuller S, Flugel RM, Lochelt M. 2000. The intact retroviral Env glycoprotein of human foamy virus is a trimer. J Virol 74:2885–2887. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.6.2885-2887.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Effantin G, Estrozi LF, Aschman N, Renesto P, Stanke N, Lindemann D, Schoehn G, Weissenhorn W. 2016. Cryo-electron microscopy structure of the native prototype foamy virus glycoprotein and virus architecture. PLoS Pathog 12:e1005721. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu GJ, Kula T, Xu Q, Li MZ, Vernon SD, Ndung’u T, Ruxrungtham K, Sanchez J, Brander C, Chung RT, O’Connor KC, Walker B, Larman HB, Elledge SJ. 2015. Comprehensive serological profiling of human populations using a synthetic human virome. Science 348. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa0698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khan AS, Bodem J, Buseyne F, Gessain A, Johnson W, Kuhn JH, Kuzmak J, Lindemann D, Linial ML, Löchelt M, Materniak-Kornas M, Soares MA, Switzer WM. 2018. Spumaretroviruses: updated taxonomy and nomenclature. Virology 516:158–164. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2017.12.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Richard L, Rua R, Betsem E, Mouinga-Ondeme A, Kazanji M, Leroy E, Njouom R, Buseyne F, Afonso PV, Gessain A. 2015. Cocirculation of two env molecular variants, of possible recombinant origin, in gorilla and chimpanzee simian foamy virus strains from Central Africa. J Virol 89:12480–12491. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01798-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muhle M, Bleiholder A, Lochelt M, Denner J. 2017. Epitope mapping of the antibody response against the envelope proteins of the feline foamy virus. Viral Immunol 30:388–395. doi: 10.1089/vim.2016.0156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schweizer M, Schleer H, Pietrek M, Liegibel J, Falcone V, Neumann-Haefelin D. 1999. Genetic stability of foamy viruses: long-term study in an African green monkey population. J Virol 73:9256–9265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Havenar-Daughton C, Abbott RK, Schief WR, Crotty S. 2018. When designing vaccines, consider the starting material: the human B cell repertoire. Curr Opin Immunol 53:209–216. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2018.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lessler J. 2014. Charting the life-course epidemiology of influenza. Science 346:919–920. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa0613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Etenna SL, Caron M, Besson G, Makuwa M, Gessain A, Mahe A, Kazanji M. 2008. New insights into prevalence, genetic diversity, and proviral load of human T-cell leukemia virus types 1 and 2 in pregnant women in Gabon in equatorial central Africa. J Clin Microbiol 46:3607–3614. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01249-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burbelo PD, Meoli E, Leahy HP, Graham J, Yao K, Oh U, Janik JE, Mahieux R, Kashanchi F, Iadarola MJ, Jacobson S. 2008. Anti-HTLV antibody profiling reveals an antibody signature for HTLV-I-associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis (HAM/TSP). Retrovirology 5:96. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-5-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuramitsu M, Sekizuka T, Yamochi T, Firouzi S, Sato T, Umeki K, Sasaki D, Hasegawa H, Kubota R, Sobata R, Matsumoto C, Kaneko N, Momose H, Araki K, Saito M, Nosaka K, Utsunomiya A, Koh KR, Ogata M, Uchimaru K, Iwanaga M, Sagara Y, Yamano Y, Okayama A, Miura K, Satake M, Saito S, Itabashi K, Yamaguchi K, Kuroda M, Watanabe T, Okuma K, Hamaguchi I. 2017. Proviral features of human T cell leukemia virus type 1 in carriers with indeterminate Western blot analysis results. J Clin Microbiol 55:2838–2849. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00659-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coelho-dos-Reis JG, Peruhype-Magalhães V, Pascoal-Xavier MA, de Souza Gomes M, do Amaral LR, Cardoso LM, Jonathan-Gonçalves J, Ribeiro ÁL, Starling ALB, Ribas JG, Gonçalves DU, de Freitas Carneiro-Proietti AB, Teixeira-Carvalho A, Martins-Filho OA. Giph. 2017. Flow cytometric-based protocols for assessing anti-MT-2 IgG1 reactivity: high-dimensional data handling to define predictors for clinical follow-up of human T-cell leukemia virus type-1 infection. J Immunol Meth 444:36–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2017.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rusert P, Kouyos RD, Kadelka C, Ebner H, Schanz M, Huber M, Braun DL, Hoze N, Scherrer A, Magnus C, Weber J, Uhr T, Cippa V, Thorball CW, Kuster H, Cavassini M, Bernasconi E, Hoffmann M, Calmy A, Battegay M, Rauch A, Yerly S, Aubert V, Klimkait T, Boni J, Fellay J, Regoes RR, Gunthard HF, Trkola A, Swiss Hivcs T. 2016. Determinants of HIV-1 broadly neutralizing antibody induction. Nat Med 22:1260–1267. http://www.nature.com/nm/journal/v22/n11/abs/nm.4187.html#supplementary-information. doi: 10.1038/nm.4187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kadelka C, Liechti T, Ebner H, Schanz M, Rusert P, Friedrich N, Stiegeler E, Braun DL, Huber M, Scherrer AU, Weber J, Uhr T, Kuster H, Misselwitz B, Cavassini M, Bernasconi E, Hoffmann M, Calmy A, Battegay M, Rauch A, Yerly S, Aubert V, Klimkait T, Böni J, Kouyos RD, Günthard HF, Trkola A. 2018. Distinct, IgG1-driven antibody response landscapes demarcate individuals with broadly HIV-1 neutralizing activity. J Exp Med 215:1589–1608. doi: 10.1084/jem.20180246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muniz CP, Zheng H, Jia H, Cavalcante LTF, Augusto AM, Fedullo LP, Pissinatti A, Soares MA, Switzer WM, Santos AF. 2017. A non-invasive specimen collection method and a novel simian foamy virus (SFV) DNA quantification assay in New World primates reveal aspects of tissue tropism and improved SFV detection. PLoS One 12:e0184251. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0184251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Davies TJ, Pedersen AB. 2008. Phylogeny and geography predict pathogen community similarity in wild primates and humans. Proc R Soc Biol Sci 275:1695–1701. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2008.0284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alais S, Pasquier A, Jegado B, Journo C, Rua R, Gessain A, Tobaly-Tapiero J, Lacoste R, Turpin J, Mahieux R. 2018. STLV-1 coinfection is correlated with an increased SFV proviral load in the peripheral blood of SFV/STLV-1 naturally infected non-human primates. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 12:e0006812. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muhle M, Bleiholder A, Kolb S, Hubner J, Lochelt M, Denner J. 2011. Immunological properties of the transmembrane envelope protein of the feline foamy virus and its use for serological screening. Virology 412:333–340. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2011.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zemba M, Alke A, Bodem J, Winkler IG, Flower RLP, Pfrepper KI, Delius H, Flugel RM, Löchelt M. 2000. Construction of infectious feline foamy virus genomes: Cat antisera do not cross-neutralize feline foamy virus chimera with serotype-specific env sequences. Virology 266:150–156. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Choudhary A, Galvin TA, Williams DK, Beren J, Bryant MA, Khan AS. 2013. Influence of naturally occurring simian foamy viruses (SFVs) on SIV disease progression in the rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta) model. Viruses 5:1414–1430. doi: 10.3390/v5061414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Feeroz MM, Soliven K, Small CT, Engel GA, Andreina Pacheco M, Yee JL, Wang X, Kamrul Hasan M, Oh G, Levine KL, Rabiul Alam SM, Craig KL, Jackson DL, Lee E-G, Barry PA, Lerche NW, Escalante AA, Matsen Iv FA, Linial ML, Jones-Engel L. 2013. Population dynamics of rhesus macaques and associated foamy virus in Bangladesh. Emerg Mic Infect 2:e29. doi: 10.1038/emi.2013.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mouinga-Ondeme A, Caron M, Nkoghe D, Telfer P, Marx P, Saib A, Leroy E, Gonzalez JP, Gessain A, Kazanji M. 2012. Cross-species transmission of simian foamy virus to humans in rural Gabon, Central Africa. J Virol 86:1255–1260. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06016-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Precopio ML, Butterfield TR, Casazza JP, Little SJ, Richman DD, Koup RA, Roederer M. 2008. Optimizing peptide matrices for identifying T-cell antigens. Cytometry 73A:1071–1078. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Greijer AE, van de Crommert JMG, Stevens SJC, Middeldorp JM. 1999. Molecular fine-specificity analysis of antibody responses to human cytomegalovirus and design of novel synthetic-peptide-based serodiagnostic assays. J Clin Microbiol 37:179–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Desgranges C, Souche S, Vernant JC, Smadja D, Vahlne A, Horal P. 1994. Identification of novel neutralization-inducing regions of the human T-cell lymphotropic virus type I envelope glycoproteins with human HTLV-1-seropositive sera. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 10:163–173. doi: 10.1089/aid.1994.10.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]