The latent human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) transcriptome has been extremely difficult to define due to the scarcity of naturally latent cells and the complexity of available models. The genomic era offers many approaches to transcriptome profiling that hold great potential for elucidating this challenging issue.

KEYWORDS: cytomegalovirus, herpesvirus, latency, transcriptome

ABSTRACT

The latent human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) transcriptome has been extremely difficult to define due to the scarcity of naturally latent cells and the complexity of available models. The genomic era offers many approaches to transcriptome profiling that hold great potential for elucidating this challenging issue. The results from two recent studies applying different transcriptomic methodologies and analyses of both experimental and natural samples challenge the dogma of a restricted latency-associated transcription program. Instead, they portray the hallmark of HCMV latent infection as low-level expression of a broad spectrum of canonical viral lytic genes.

INTRODUCTION

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) is a widespread pathogen infecting most of the population worldwide. Like other herpesviruses, it can establish latent infection that persists for the lifetime of the host. Although HCMV infection in healthy individuals is mostly asymptomatic, reactivation from latency in immunocompromised individuals constitutes a serious health burden (1–3). Molecular understanding of the interplay between virus and host during HCMV latency and reactivation could pave the way to target latently infected cells and to prevent reactivation in vivo.

HCMV has a wide cell tropism within its human host (4). The cellular environment is a key factor in determining the outcome of HCMV infection, as cellular epigenetic mechanisms are important in regulating viral gene expression (5–8). Unlike many cell types that support lytic infection, in cells of the early myeloid lineage, the virus establishes latent infection characterized by maintenance of the viral genome in the absence of infectious virus production (9–14). Therefore, studies of both experimental latency and of latency in the natural context largely focus on CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPCs) and CD14+ monocytes (15). Both HPCs and CD14+ monocytes are dividing cells; this therefore raises the question of how HCMV latency is maintained. Gammaherpesviruses also reside in replicating B cells, and it is well established that during gammaherpesvirus latency, only a limited set of viral genes is expressed, which are important for the maintenance of the viral genome during latency (16–19). Thus, it was consequently presumed that the latent transcriptional program in HCMV is similarly restricted to a very limited group of functional genes and thus is qualitatively different from the transcriptional pattern during lytic infection (20–22).

The earliest studies that looked for latency-associated gene expression identified a number of transcripts arising from the major immediate early promoter (MIEP) region of HCMV, but no function was assigned to them (23, 24). More systematic mapping of latency-associated transcripts was conducted with the emergence of microarray technology. Two studies detected a number of viral transcripts in experimentally latently infected myeloid progenitor cells, utilizing HCMV gene-specific microarrays (25, 26). The latent transcripts reported by these studies were used as a guideline for targeted efforts to identify gene products important for latency establishment and maintenance. Subsequent work detected a number of these transcripts during natural latency, mainly using high-sensitivity low-throughput approaches, such as nested PCR, building a short list of viral genes that were generally accepted to represent a distinct transcriptional profile during latent infection (20, 21, 27). More recently, RNA sequencing was applied to experimentally infected as well as naturally infected CD14+ monocytes and HPCs, revealing wider gene expression profile, but still limited to under 20 viral genes (28). Two recent studies performed thorough analyses of the viral transcriptome during HCMV latent infection, in both natural and experimental settings, and revealed that the pool of viral transcripts in latently infected cells is much broader than previously appreciated, with work from our lab pointing to the high similarity to late lytic viral transcriptome, albeit at much lower levels (29, 30).

Studying viral gene expression in natural samples is highly challenging, as it is very hard to detect. The proportion of infected mononuclear cells in seropositive individuals was estimated, by PCR-driven in situ hybridization, at 1:10,000 to 25,000, with a copy number of 2 to 13 genomes per infected cell (31). Using digital PCR, viral genomes were detected in less than half of seropositive individuals, and the viral load was <10 genomes in 10,000 cells in most individuals (32, 33); from these genomes, viral transcription is expected to be extremely low. Thus, interrogation of the HCMV transcript pool in natural samples in a high-throughput manner requires an immense amount of transcriptomic data. Publically available RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) repositories offer a great opportunity to explore massive data sets from many individuals and various tissues. Analysis of the human RNA-seq atlas generated by the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) Consortium (34) revealed 29 samples containing HCMV reads (30). The list of transcripts found in these samples included many of the HCMV transcripts expressed during lytic infection, and their relative levels correlated with those during late lytic experimental infection of fibroblasts. Essentially, there was no evidence for a highly restricted latency-associated viral gene expression program in any of the tissues in this natural setting. However, since the data are taken from tissue samples, it remains unclear which cell types contained viral reads and what was their infection status. The Goodrum group conducted HCMV transcriptome analysis in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from seropositive individuals, utilizing a targeted enrichment approach that facilitated at least 6,000-fold enrichment (29). The results indicate that >90% of the lytic transcriptome was present in these samples, and also in this data set, the relative viral transcript levels correlate with the late lytic transcriptome in fibroblasts. Although in these targeted experiments the cells are better defined, the enrichment procedure makes it hard to quantify how prevalent viral gene expression is. The evidence from these two different studies, applying two different comprehensive and unbiased transcriptomic approaches, indicates that in natural setting, many viral transcripts could be identified. Although the source of the cells that express these transcripts remains unclear, overall, these surveys did not result in data that support the dogma of a restricted well-defined latency-specific transcriptional program.

Due to challenges of analyzing latently HCMV-infected cells from HCMV-positive individuals, in vitro HCMV-infected primary cells, namely, HPCs, granulocyte-monocyte progenitors (GMPs), and monocytes, serve as a model. The caveats of these systems are their heterogeneity and the possibility that they represent dynamic differentiation states, depending on their culturing methods and other factors. Since HCMV reactivation is associated with myeloid differentiation, this may affect viral transcriptome analysis when done at the population level. In addition, HCMV latency may represent multiple programs, which will also be lost in bulk analyses. Single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) is a powerful methodology which can define cellular heterogeneity and has proven to be instrumental in studying viral infections, as their dynamics and progression rely, to a great extent, on the host cell (35–37). The scRNA-seq we applied to HCMV-infected CD14+ monocytes and CD34+ HPCs (30) should be considered as a sampling procedure where the reads per cell reflect random sampling from a pool of approximately 100,000 mRNA molecules, which differs between cells depending on the cell type or regulatory state. In order to perform reliable analysis despite sparse data from single cells, the next step in any scRNA-seq experiment is to use a probabilistic model that stratifies cells based on their similarity in the sampled transcriptome. The result of this analysis is a gene expression signature extracted from a group of cells, which can be conceived as a meta-cell. If enough cells are sampled, this facilitates the measurement of even lowly expressed genes, allowing unbiased analysis of viral gene expression, taking into account cellular and viral heterogeneity.

The analysis of 3,655 experimentally infected monocytes revealed that most of the cells constitute a large continuous population, with only a small group that formed a distinct population. The small distinct population exhibited high levels of viral gene expression, and although we cannot ascertain that they are undergoing bona fide productive infection, they display a viral transcriptome that closely resembles a late lytic transcriptome in macrophages and fibroblasts in both pattern and levels. The vast majority of cells, on the other hand, exhibited very low to undetectable viral gene expression levels, indicating that they are not lytically infected. This low expression level is not a technical issue related to scRNA sequencing, as the relative levels of viral transcripts out of the total transcripts are comparable to the levels when performing RNA-seq on bulk samples containing large numbers of cells. In fact, the use of molecular barcoding (unique molecular identifiers) provides a more reliable quantification of transcripts, as it bypasses amplification biases during library construction. The prominent difference in viral gene expression between the population of cells that showed repressed expression of viral gene expression and the lytic population was in the levels of viral transcripts and not the pattern of viral gene expression. Looking within the continuous latent population, it was evident that viral gene expression levels gradually and progressively declined, a phenomenon that was tightly linked to the time postinfection. Nevertheless, throughout the latent population, the most highly expressed genes were the most highly expressed in late lytic infection stage, and the transcripts that became undetectable were the lower-expressing ones in late lytic infection stage, indicating continuous repression of the same transcriptional program. Importantly, the comparison between gene expression patterns was done using Spearman’s correlation, which is based on ranking, and therefore, the similarity in expression pattern could not stem from a few extreme transcripts or outliers (38).

In the latest time points we analyzed, 7 and 14 days postinfection, almost no viral reads were detected. Viral gene expression in cells from these time points was less correlated to viral gene expression in the lytic population, but this reduction in the correlation coefficient is expected given the scarcity of viral reads, leading to high sampling error. Still, even at this extremely repressed state, the viral transcripts that were detected were largely those that were highly expressed in lytic cells. Importantly, this very low expression could not be attributed to the sparse nature of scRNA-seq, as we analyzed 1,219 cells allowing us to efficiently quantify the expression of 12,000 genes. When genes are ranked based on their expression levels in these cells, the few viral transcripts that were still detected rank between 7,500 (RNA 2.7) and 11,413 (UL80). Given that it is estimated that around 10,000 different transcripts are expressed in levels that are greater than 1 copy per cell in a given cell, this low ranking reflects a state in which the virus is almost completely repressed. The parsimonious explanation for these measurements is a gradual repression of a similar viral gene expression program along the time after infection. Thus, in this comprehensive single-cell analysis, there was no evidence for a cell population exhibiting a clear latent-specific transcriptome, and the prominent difference in gene expression was quantitative. Nevertheless, as it is known that the proportion of cells reactivating from latency is extremely low, it remains possible that there is a small population of cells that exhibit a differential program and were missed in this analysis. At the sampling depth and coverage efficiency we obtained, subpopulations of less than 0.3% (11 to 12 cells) could have been missed (30).

Significantly, single-cell analysis of CD34+ HPCs also revealed viral gene expression that largely resembles the late lytic transcriptome, but in these cells, viral gene expression was even more heavily repressed. Furthermore, analysis of the independent data set of experimentally infected CD34+ HPCs and fibroblast from a study by Cheng et al. (29) also revealed a similar pattern, that the most highly expressed genes in latent cells were the most highly expressed in late lytic infection and the very low and undetectable genes are those that are low expressing in late lytic infection (30). The Goodrum group also demonstrated that viral gene expression in these latent cultures is largely unaffected by presence of ganciclovir, which inhibits viral DNA lytic replication, indicating that this expression profile is independent of viral DNA replication (29).

Since the definition of latency encompasses the ability of the virus to reactivate, and it is currently difficult to connect between snapshots of gene expression profiles and a functional outcome, it remains possible that most of the cells that were probed represent abortive infection and not latency. However, this reservation is true for any study analyzing viral gene expression. Additionally, since both studies profiled only polyadenylated RNAs, the possibility that nonpolyadenylated RNAs, such as microRNAs (miRNAs), are expressed in a latency-specific manner could not be precluded. Furthermore, several studies suggested that different isoforms of viral transcripts are expressed specifically during latency (39–41). Our single-cell RNA-seq libraries capture only the 3′ ends of transcripts, preventing any analysis of differential isoform expression. The Goodrum group also did not analyze differential viral isoform expression (29), and their enrichment procedure will make such analysis challenging. Therefore, an unbiased assessment of whether specific isoforms indeed represent a bona fide latency program awaits future analysis.

Notably, by using recombinant viruses supporting latent-like or replicative modes of infection in HPCs, Cheng et al. (29) suggest 30 genes which are antagonistically expressed between these two modes of infection. The single-cell analysis of infection in CD14+ monocytes or CD34+ HPCs also revealed few viral genes that exhibited higher relative expression in latent infection than in lytic infection. Nevertheless, none of the viral genes that have well-documented roles in latency establishment, such as US28 and UL138, were among these differentially expressed genes. This illustrates that differences in relative gene expression pattern between latent and lytic modes of infection, at least in these experimental models, is not necessarily a requirement for a functional role in latency or reactivation. Therefore, these new data sets raise the possibility that exhibiting differential expression is not necessarily an indication of viral genes that functionally contribute to distinct modes of infection.

Overall, our analysis emphasizes an undeniable surprising similarity between latent and late lytic transcriptional programs in the two studies. These results, together with results from natural samples, challenge the view of a well-defined HCMV latency-specific transcriptional program that is composed of few selective functional genes. Instead, these measurements raise the possibility of a gradual repression of viral gene expression resulting in low-level expression of a program that resembles late lytic infection stage. Importantly, although these findings suggest that most viral genes are not transcribed in a latency-regulated manner, they do not undermine their possible importance in establishment and maintenance of latency. Based on the prevalent view that only a limited number of genes are expressed during HCMV latency, only several candidates for viral functions that may control HCMV latency have been studied. The recent data from Shnayder et al. (30) and Cheng et al. (29) suggest many more viral gene candidates that may contribute during latent infection.

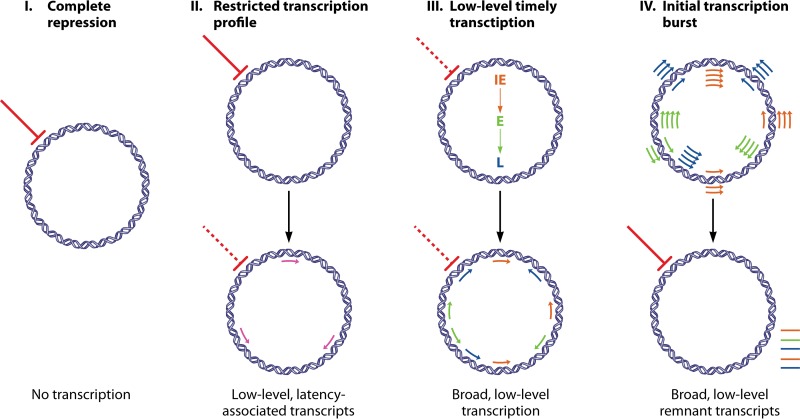

Another important withstanding question is, what are the molecular events leading to the viral transcriptional state during latency? Several options could be considered (Fig. 1). First, after viral entry, the virus is immediately repressed, and there is no de novo viral gene transcription. This option seems improbable, in light of the evidence in the literature of measurable levels of viral transcripts in latent infection (25, 26, 28–30) and results showing undetectable levels of viral transcripts following infection with UV-inactivated virus (29, 30). Second, following entry, in response to suppression of the virus by the host environment, the virus initiates a latency-regulated transcriptional program leading to the expression of a limited number of genes which are required for the establishment and maintenance of latency. Although this option represents the leading dogma, as described above, the recent high-throughput studies of HCMV latency challenge it. Third, the virus initiates the timely transcriptional cascade of productive infection at some level but is prematurely interrupted by cellular mechanisms. A fourth alternative is that very early after viral entry, there is a burst of viral gene expression that is followed by massive repression or even complete repression of viral transcription. The last two options are more likely in light of the entirety of the data in the literature. Importantly, a transcriptional burst was reported in the very early stage of murine CMV (MCMV) lytic infection (42, 43) and interestingly, also at the first phase of herpes simplex virus (HSV) reactivation from latency prior to the timely cascade of viral gene expression (44, 45).

FIG 1.

Molecular events leading to the latent HCMV transcriptome state. (I) Following viral entry, the virus is immediately repressed, and there is no de novo viral gene transcription. (II) Following viral entry, the virus is transcriptionally repressed by the host environment, and in response, the virus initiates a latency-regulated transcriptional program leading to the expression of a limited number of latency-associated genes. (III) The virus initiates the timely transcriptional cascade of productive infection at some level but is prematurely interrupted and strongly repressed by cellular mechanisms leading to low-level expression of transcripts from all three kinetic classes. (IV) Very early after viral entry, there is a burst of viral gene expression across the whole viral genome that is followed by massive repression. In that case, most of the transcripts that were detected in latent infections are remnants of the initial burst. Complete repression is marked by a solid line. Incomplete repression is marked by a dashed line. IE, intermediate early; E, early; L, late.

If the in vitro infection models adequately reflect the events that occur during HCMV latency, these high-throughput measurements indicate that HCMV latency at the cell level is a state in which no viral progeny is produced and there are very low levels of viral transcripts. Therefore, viral RNAs or proteins that have a role in the establishment of latency probably act mainly at the early stages of latency establishment or are functional even at low levels.

High-temporal-resolution measurements, at a single-cell level, of the early steps during latent and lytic infections of different myeloid populations will help shed light on the molecular events that lead to the wide but repressed viral gene expression in latent cells. Furthermore, these could provide an outstanding opportunity to determine the initial factors that govern these two discrete infection outcomes. We anticipate that future work using single-cell and unbiased genomic approaches will deepen our understanding of the complex interplay between the virus and host during latency and will help pave the way to novel insights and potentially new therapeutic strategies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Miri Shnayder for providing valuable feedback.

Work in the Stern-Ginossar lab on HCMV latency is supported by a European Research Council starting grant (StG-2014-638142) and by a research grant from Nona L. Abrams.

REFERENCES

- 1.Griffiths PD. 2010. Cytomegalovirus in intensive care. Rev Med Virol 20:1–3. doi: 10.1002/rmv.646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crough T, Khanna R. 2009. Immunobiology of human cytomegalovirus: from bench to bedside. Clin Microbiol Rev 22:76–98. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00034-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Limaye AP, Kirby KA, Rubenfeld GD, Leisenring WM, Bulger EM, Neff MJ, Gibran NS, Huang M-L, Hayes TKS, Corey L, Boeckh M. 2008. Cytomegalovirus reactivation in critically ill immunocompetent patients. JAMA 300:413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sinzger C, Digel M, Jahn G. 2008. Cytomegalovirus cell tropism. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 325:63–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saffert RT, Penkert RR, Kalejta RF. 2010. Cellular and viral control over the initial events of human cytomegalovirus experimental latency in CD34+ cells. J Virol 84:5594–5604. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00348-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saffert RT, Kalejta RF. 2007. Human cytomegalovirus gene expression is silenced by Daxx-mediated intrinsic immune defense in model latent infections established in vitro. J Virol 81:9109–9120. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00827-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reeves MB. 2011. Chromatin-mediated regulation of cytomegalovirus gene expression. Virus Res 157:134–143. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2010.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sinclair J. 2010. Chromatin structure regulates human cytomegalovirus gene expression during latency, reactivation and lytic infection. Biochim Biophys Acta Gene Regul Mech 1799:286–295. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Movassagh M, Gozlan J, Senechal B, Baillou C, Petit J, Lemoine F. 1996. Direct infection of CD34+ progenitor cells by human cytomegalovirus: evidence for inhibition of hematopoiesis and viral replication. Blood 88:1277–1283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sindre H, Tjonnfjord GE, Rollag H, Ranneberg-Nilsen T, Veiby OP, Beck S, Degre M, Hestdal K. 1996. Human cytomegalovirus suppression of and latency in early hematopoietic progenitor cells. Blood 88:4526–4533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhuravskaya T, Maciejewski JP, Netski DM, Bruening E, Mackintosh FR, St. Jeor S. 1997. Spread of human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) after infection of human hematopoietic progenitor cells: model of HCMV latency. Blood 90:2482–2491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kondo K, Kaneshima H, Mocarski ES. 1994. Human cytomegalovirus latent infection of granulocyte-macrophage progenitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 91:11879–11883. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.25.11879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hahn G, Jores R, Mocarski ES. 1998. Cytomegalovirus remains latent in a common precursor of dendritic and myeloid cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95:3937–3942. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taylor-Wiedeman J, Sissons JGP, Borysiewicz LK, Sinclair JH. 1991. Monocytes are a major site of persistence of human cytomegalovirus in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Gen Virol 72:2059–2064. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-72-9-2059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goodrum F. 2016. Human cytomegalovirus latency: approaching the Gordian knot. Annu Rev Virol 3:333–357. doi: 10.1146/annurev-virology-110615-042422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arvey A, Tempera I, Tsai K, Chen H-S, Tikhmyanova N, Klichinsky M, Leslie C, Lieberman PM. 2012. An atlas of the Epstein-Barr virus transcriptome and epigenome reveals host-virus regulatory interactions. Cell Host Microbe 12:233–245. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kang M-S, Kieff E. 2015. Epstein-Barr virus latent genes. Exp Mol Med 47:e131. doi: 10.1038/emm.2014.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bruce AG, Barcy S, DiMaio T, Gan E, Garrigues HJ, Lagunoff M, Rose TM. 2017. Quantitative analysis of the KSHV transcriptome following primary infection of blood and lymphatic endothelial cells. Pathogens 6:11. doi: 10.3390/pathogens6010011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weidner-Glunde M, Mariggiò G, Schulz TF. 2017. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latency-associated nuclear antigen: replicating and shielding viral DNA during viral persistence. J Virol 91:e01083-16. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01083-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Slobedman B, Cao JZ, Avdic S, Webster B, McAllery S, Cheung AK, Tan JC, Abendroth A. 2010. Human cytomegalovirus latent infection and associated viral gene expression. Future Microbiol 5:883–900. doi: 10.2217/fmb.10.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Poole E, Sinclair J. 2015. Sleepless latency of human cytomegalovirus. Med Microbiol Immunol 204:421–429. doi: 10.1007/s00430-015-0401-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dupont L, Reeves MB. 2016. Cytomegalovirus latency and reactivation: recent insights into an age old problem. Rev Med Virol 26:75–89. doi: 10.1002/rmv.1862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kondo K, Mocarski ES. 1995. Cytomegalovirus latency and latency-specific transcription in hematopoietic progenitors. Scand J Infect Dis Suppl 99:63–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kondo K, Xu J, Mocarski ES. 1996. Human cytomegalovirus latent gene expression in granulocyte-macrophage progenitors in culture and in seropositive individuals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93:11137–11142. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.11137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goodrum FD, Jordan CT, High K, Shenk T. 2002. Human cytomegalovirus gene expression during infection of primary hematopoietic progenitor cells: a model for latency. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99:16255–16260. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252630899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheung AKL, Abendroth A, Cunningham AL, Slobedman B. 2006. Viral gene expression during the establishment of human cytomegalovirus latent infection in myeloid progenitor cells. Blood 108:3691–3699. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-12-026682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sinclair JH, Reeves MB. 2013. Human cytomegalovirus manipulation of latently infected cells. Viruses 5:2803–2824. doi: 10.3390/v5112803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rossetto CC, Tarrant-Elorza M, Pari GS. 2013. Cis and trans acting factors involved in human cytomegalovirus experimental and natural latent infection of CD14+ monocytes and CD34+ cells. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003366. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheng S, Caviness K, Buehler J, Smithey M, Nikolich-Žugich J, Goodrum F. 2017. Transcriptome-wide characterization of human cytomegalovirus in natural infection and experimental latency. Proc Natl Acad Sci 114:E10586–E10595. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1710522114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shnayder M, Nachshon A, Krishna B, Poole E, Boshkov A, Binyamin A, Maza I, Sinclair J, Schwartz M, Stern-Ginossar N. 2018. Defining the transcriptional landscape during cytomegalovirus latency with single-cell RNA sequencing. mBio 9:e00013-18. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00013-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Slobedman B, Mocarski ES. 1999. Quantitative analysis of latent human cytomegalovirus. J Virol 73:4806–4812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jackson SE, Sedikides GX, Okecha G, Poole EL, Sinclair JH, Wills MR. 2017. Latent cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection does not detrimentally alter T cell responses in the healthy old, but increased latent CMV carriage is related to expanded CMV-specific T cells. Front Immunol 8:733. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parry HM, Zuo J, Frumento G, Mirajkar N, Inman C, Edwards E, Griffiths M, Pratt G, Moss P. 2016. Cytomegalovirus viral load within blood increases markedly in healthy people over the age of 70 years. Immun Ageing 13:1. doi: 10.1186/s12979-015-0056-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ardlie KG, Deluca DS, Segre AV, Sullivan TJ, Young TR, Gelfand ET, Trowbridge CA, Maller JB, Tukiainen T, Lek M, Ward LD, Kheradpour P, Iriarte B, Meng Y, Palmer CD, Esko T, Winckler W, Hirschhorn JN, Kellis M, MacArthur DG, Getz G, Shabalin AA, Li G, Zhou Y-H, Nobel AB, Rusyn I, Wright FA, Lappalainen T, Ferreira PG, Ongen H, Rivas MA, Battle A, Mostafavi S, Monlong J, Sammeth M, Mele M, Reverter F, Goldmann JM, Koller D, Guigo R, McCarthy MI, Dermitzakis ET, Gamazon ER, Im HK, Konkashbaev A, Nicolae DL, Cox NJ, Flutre T, Wen X, Stephens M, et al. 2015. The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) pilot analysis: multitissue gene regulation in humans. Science 348:648–660. doi: 10.1126/science.1262110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Russell AB, Trapnell C, Bloom JD. 2018. Extreme heterogeneity of influenza virus infection in single cells. Elife 7:e32302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zanini F, Pu S-Y, Bekerman E, Einav S, Quake SR. 2018. Single-cell transcriptional dynamics of flavivirus infection. Elife 7:e32942. doi: 10.7554/eLife.32942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Steuerman Y, Cohen M, Peshes-Yaloz N, Valadarsky L, Cohn O, David E, Frishberg A, Mayo L, Bacharach E, Amit I, Gat-Viks I. 2018. Dissection of influenza infection in vivo by single-cell RNA sequencing. Cell Syst 6:679–691.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2018.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goodrum F, McWeeney S. 2018. A single-cell approach to the elusive latent human cytomegalovirus transcriptome. mBio 9:e01001-18. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01001-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tarrant-Elorza M, Rossetto CC, Pari GS. 2014. Maintenance and replication of the human cytomegalovirus genome during latency. Cell Host Microbe 16:43–54. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jenkins C, Abendroth A, Slobedman B. 2004. A novel viral transcript with homology to human interleukin-10 is expressed during latent human cytomegalovirus infection. J Virol 78:1440–1447. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.3.1440-1447.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Collins-McMillen D, Rak M, Buehler J, Igarashi-Hayes S, Kamil JP, Moorman N, Goodrum FD. 2018. Alternative promoters drive human cytomegalovirus reactivation from latency. bioRxiv doi: 10.1101/484436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Marcinowski L, Lidschreiber M, Windhager L, Rieder M, Bosse JB, Rädle B, Bonfert T, Györy I, De Graaf M, Prazeres Da Costa O, Rosenstiel P, Friedel CC, Zimmer R, Ruzsics Z, Dölken L. 2012. Real-time transcriptional profiling of cellular and viral gene expression during lytic cytomegalovirus infection. PloS Pathog 8:e01002908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Erhard F, Baptista MA, Krammer T, Hennig T, Lange M, Arampatzi P, Juerges C, Theis FJ, Saliba A-E, Doelken L. 2019. scSLAM-seq reveals core features of transcription dynamics in single cells. bioRxiv doi: 10.1101/486852. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Kim JY, Mandarino A, Chao MV, Mohr I, Wilson AC. 2012. Transient reversal of episome silencing precedes VP16-dependent transcription during reactivation of latent HSV-1 in neurons. PLoS Pathog 8:1002540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Du T, Zhou G, Roizman B. 2011. HSV-1 gene expression from reactivated ganglia is disordered and concurrent with suppression of latency-associated transcript and miRNAs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:18820–18824. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117203108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]