LETTER

In their recent report, Costafreda and Kaplan (1) claim that CRISPR/Cas9 knockout of TIM1 (also called HAVCR1) renders the GL37 clone of African green monkey kidney (AGMK) cells resistant to infection with hepatitis A virus (HAV). They concluded that TIM1 “is required for infection” and is a “functional receptor” for HAV, as Kaplan and colleagues suggested many years ago (2). This surprised us, as we had previously found that both naked and quasi-enveloped HAV (eHAV) virions (3) readily infect Vero (and Huh-7.5) cells in which TIM1 expression was knocked out by CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing (4). We observed that the binding of quasi-enveloped virions to Vero cells was reduced (but not eliminated) at 4°C by TIM1 knockout, suggesting that TIM1 acts as an accessory attachment factor by binding phosphatidylserine (Ptd-Ser) on the eHAV quasi-envelope surface (5, 6). However, eHAV infection proceeded efficiently at 37°C, and we noted no differences in either binding or infection with naked HAV (4).

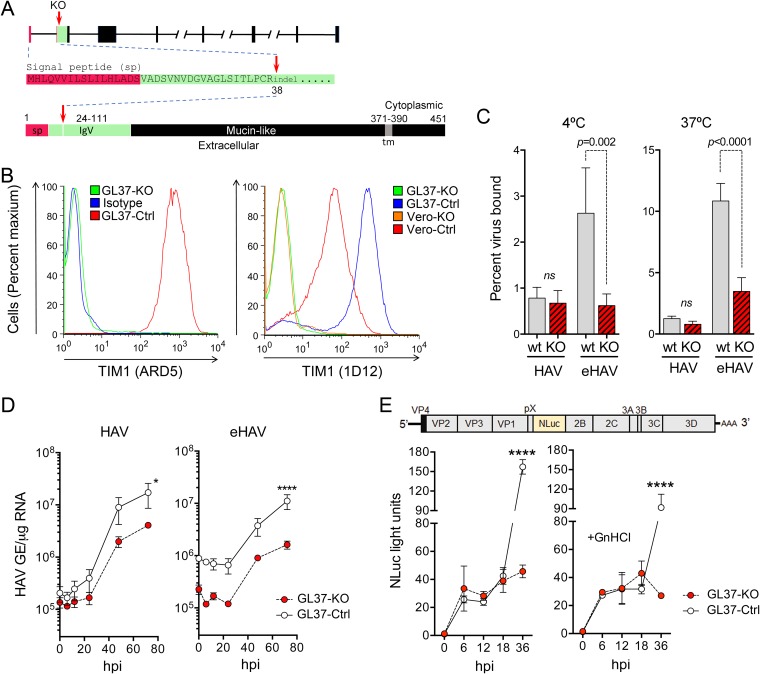

We suggested to Dr. Kaplan that we exchange our knockout cell lines to resolve these conflicting observations but were told that his cells were no longer available due to a freezer malfunction. We thus generated a new TIM1 knockout cell line (GL37-KO) using GL37 cells obtained from Dr. Kaplan in 2012 and one of the single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) described by Costafreda and Kaplan that target exon 2 (ACACTGCCCTGCCGCTACAA) (1) (Fig. 1A) cloned into the lenticrisprV2 plasmid (Addgene catalog number 52961) (4). Lentivirus-transduced GL37 cells were expanded in media containing puromycin for 3 weeks, as described previously (4). DNA sequencing of surviving cells showed 100% identity to the Chlorocebus aethiops genome (GenBank accession number X98252.1) and confirmed disruption of the TIM1 sequence by small indels at codon 38, leading to a frameshift within exon 2 (Fig. 1A). Cell surface staining with antibodies to human TIM1 confirmed the loss of TIM1 expression in the GL37-KO cells compared to its expression in control cells (GL37-Ctrl) transduced with a nontargeting sgRNA (AACCTACGGGCTACGATACG) (Fig. 1B).

FIG 1.

GL37-KO cells lacking expression of TIM1 are permissive for HAV infection. (A) Organization of the TIM1 gene and its protein product in C. aethiops. Red arrows indicate where the sequence is disrupted (codon 38) with small indels in exon 2. At the bottom is shown the domain structure of TIM1 with amino acids numbered and the signal peptide (sp) sequence shown in red and the IgV domain (residues 24 to 111), which binds Ptd-Ser, in green. tm, transmembrane domain. (B) Flow cytometry analysis of cell surface staining for TIM1 with ARD5 (10) (left) and 1D12 (Biolegend) (right) monoclonal antibodies. Isotype, GL37-Ctrl cells stained with isotype control IgG. (C) Percent binding of iodixanol gradient-purified naked HAV and quasi-enveloped HAV to GL37-Ctrl and GL37-KO cells at 4°C (left) and 37°C (right). Results shown are means ± standard errors of the means (SEM) from 3 independent experiments, each with 2 to 3 technical replicates. ns, nonsignificant. (D) HAV RNA in lysates of GL37-Ctrl and GL37-KO cells following infection with gradient-purified naked (left) and quasi-enveloped (right) virus. GE, genome equivalents; hpi, hours postinoculation. Results are means of a total of 4 replicates ± SEM from 2 independent experiments. *, P = 0.017; ****, P < 0.0001 at 72 h. (E) At the top is shown the HM175/18f-NLuc genome organization, which has the nanoluciferase (NLuc) sequence inserted between the VP1pX and 2B coding sequences. Below is shown nanoluciferase activity in GL37-Ctrl and GL37-KO cell lysates following infection with detergent-treated HM175/18f-NLuc virus in the absence (left) or presence (right) of 5 mM guanidine hydrochloride (GnHCl). Nanoluciferase expression was insensitive to GnHCl between 6 and 18 hpi, indicating that it is due to translation of input naked viral genomes. Results are means of a total of 4 replicates ± SEM from 2 independent experiments. ****, P < 0.0001 at 72 h. All statistical testing was by two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Sidak’s multiple-comparison test.

Using methods described previously (4), we observed no significant differences between the binding of naked HAV to GL37-KO and its binding to GL37-Ctrl cells at either 4°C or 37°C (Fig. 1C). As might be expected from our earlier results, the binding of quasi-enveloped HAV to the knockout cells was strongly reduced. However, in contrast to the results of Costafreda and Kaplan (1), GL37-KO cells were permissive for infection with either naked or quasi-enveloped virus (Fig. 1D). The reduced binding of eHAV to the knockout cells is consistent with TIM1 facilitating eHAV attachment via interactions with Ptd-Ser, as we observed with Vero-KO cells (4). This also explains lower virus yields following several rounds of replication at 72 h, as most progeny virus is likely to be quasi-enveloped.

To gain a clearer view of the requirement for TIM1 in first-round infections with naked HAV, we inoculated cells with a reporter virus expressing nanoluciferase (HM175/18f-NLuc) (Fig. 1E, top) after treating it with 0.5% NP-40. We observed similar 25- to 30-fold increases in nanoluciferase activity in the GL37-KO and GL37-Ctrl cells 6 to 18 h after inoculation, indicating equivalent levels of viral entry and cytoplasmic translation of the viral RNA (Fig. 1E, bottom left). Later increases in nanoluciferase 36 h postinoculation in GL37-Ctrl cells were due to new genome synthesis and second-round infections, as they were significantly reduced by the replication inhibitor guanidine hydrochloride (GnHCl) (Fig. 1E, bottom right). Unlike with the first-round infection with naked, nonenveloped virus, these second-round infections, presumably with quasi-enveloped eHAV, were sensitive to TIM1 knockout.

These data highlight the importance of TIM1 as an attachment factor for quasi-enveloped HAV in GL37 cells and confirm our earlier conclusions that TIM1 is not an essential entry factor for either HAV or eHAV (4). The GL37 clone of AGMK cells was isolated several decades ago by Yasuo Moritsugu in Tokyo, Japan, who considered it exceptionally permissive for HAV replication (7). This exceptional permissiveness of GL37 cells is likely due to their high expression of TIM1, which is much higher in GL37 cells than in Vero cells (Fig. 1B, right), and its ability to facilitate eHAV attachment.

HAV entry and uncoating remain poorly explained given the exceptional stability of the hepatovirus capsid (8, 9). We believe that it is important not to conflate the concepts of attachment factors and receptors for this picornavirus. We define a receptor as a molecule that interacts directly with the HAV capsid in a specific manner to mediate its endocytosis and/or initiate the process of uncoating. Whether such a receptor exists for HAV remains unknown.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (R01-AI103083, R01-AI131685, and U19-AI109965 to S.M.L. and R01-AI077519 and U54-AI057160 to W.M.).

Footnotes

For the author reply, see https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.02040-18.

REFERENCES

- 1.Costafreda MI, Kaplan G. 2018. HAVCR1 (CD365) and its mouse ortholog are functional hepatitis A virus (HAV) cellular receptors that mediate HAV infection. J Virol 92:e02065-17. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02065-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaplan G, Totsuka A, Thompson P, Akatsuka T, Moritsugu Y, Feinstone SM. 1996. Identification of a surface glycoprotein on African green monkey kidney cells as a receptor for hepatitis A virus. EMBO J 15:4282–4296. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1996.tb00803.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feng Z, Hensley L, McKnight KL, Hu F, Madden V, Ping L, Jeong S-H, Walker C, Lanford RE, Lemon SM. 2013. A pathogenic picornavirus acquires an envelope by hijacking cellular membranes. Nature 496:367–371. doi: 10.1038/nature12029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Das A, Hirai-Yuki A, González-López O, Rhein B, Moller-Tank S, Brouillette R, Hensley L, Misumi I, Lovell W, Cullen JM, Whitmire JK, Maury W, Lemon SM. 2017. TIM1 (HAVCR1) is not essential for cellular entry of either quasi-enveloped or naked hepatitis A virions. mBio 8:e00969-17. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00969-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moller-Tank S, Maury W. 2014. Phosphatidylserine receptors: enhancers of enveloped virus entry and infection. Virology 468–470:565–580. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2014.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feng Z, Li Y, McKnight KL, Hensley L, Lanford RE, Walker CM, Lemon SM. 2015. Human pDCs preferentially sense enveloped hepatitis A virions. J Clin Invest 125:169–176. doi: 10.1172/JCI77527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Totsuka A, Moritsugu Y. 1994. Hepatitis A vaccine development in Japan, p 509–513. In Nishioka K, Suzuki H, Mishiro S, Oda T(ed), Viral hepatitis and liver disease. Springer-Verlag, Tokyo, Japan. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang X, Ren J, Gao Q, Hu Z, Sun Y, Li X, Rowlands DJ, Yin W, Wang J, Stuart DI, Rao Z, Fry EE. 2015. Hepatitis A virus and the origins of picornaviruses. Nature 517:85–88. doi: 10.1038/nature13806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rivera-Serrano EE, González-López O, Das A, Lemon SM. 2019. Cellular entry and uncoating of naked and quasi-enveloped human hepatoviruses. eLife 8:e43983. doi: 10.7554/eLife.43983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kondratowicz AS, Lennemann NJ, Sinn PL, Davey RA, Hunt CL, Moller-Tank S, Meyerholz DK, Rennert P, Mullins RF, Brindley M, Sandersfeld LM, Quinn K, Weller M, McCray PB Jr, Chiorini J, Maury W. 2011. T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain 1 (TIM-1) is a receptor for Zaire Ebolavirus and Lake Victoria Marburgvirus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:8426–8431. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019030108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]