Abstract

Background

The World Health Organization recommends uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria is treated using Artemisinin‐based Combination Therapy (ACT). This review aims to assist the decision making of malaria control programmes by providing an overview of the relative benefits and harms of the available options.

Objectives

To compare the effects of ACTs with other available ACT and non‐ACT combinations for treating uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group Specialized Register; the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL); MEDLINE; EMBASE; LILACS, and the metaRegister of Controlled Trials (mRCT) to March 2009.

Selection criteria

Randomized head to head trials of ACTs in uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria.

This review is limited to: dihydroartemisinin‐piperaquine; artesunate plus mefloquine; artemether‐lumefantrine (six doses); artesunate plus amodiaquine; artesunate plus sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine and amodiaquine plus sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently assessed trials for eligibility and risk of bias, and extracted data. We analysed primary outcomes in line with the WHO 'Protocol for assessing and monitoring antimalarial drug efficacy' and compared drugs using risk ratios (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). Secondary outcomes were effects on P. vivax, gametocytes, haemoglobin, and adverse events.

Main results

Fifty studies met the inclusion criteria. All five ACTs achieved PCR adjusted failure rates of < 10%, in line with WHO recommendations, at most study sites.

Dihydroartemisinin‐piperaquine performed well compared to the ACTs in current use (PCR adjusted treatment failure versus artesunate plus mefloquine in Asia; RR 0.39, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.79; three trials, 1062 participants; versus artemether‐lumefantrine in Africa; RR 0.39, 95% CI 0.24 to 0.64; three trials, 1136 participants).

ACTs were superior to amodiaquine plus sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine in East Africa (PCR adjusted treatment failure versus artemether‐lumefantrine; RR 0.12, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.24; two trials, 618 participants; versus AS+AQ; RR 0.44, 95% CI 0.22 to 0.89; three trials, 1515 participants).

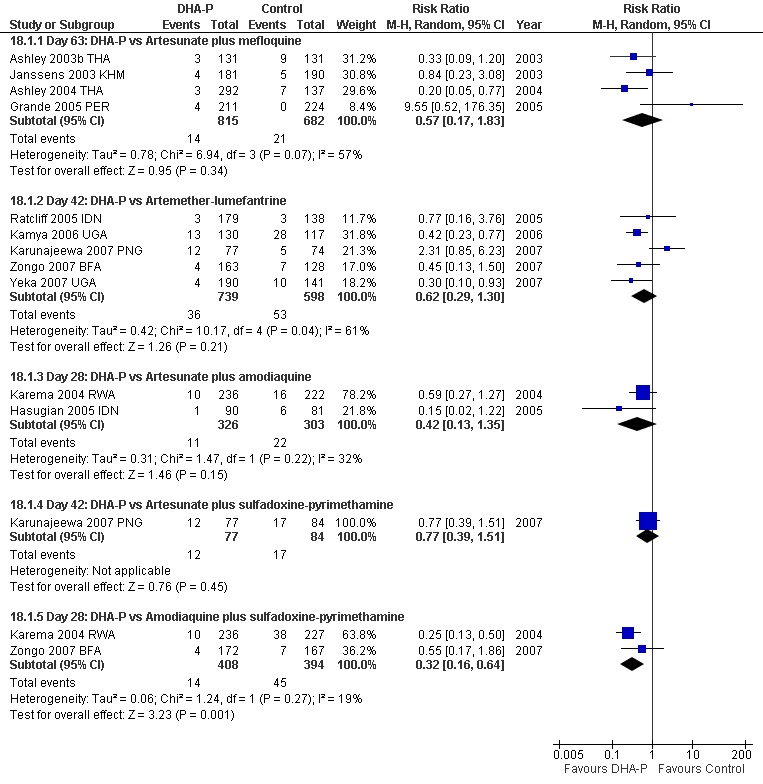

Dihydroartemisinin‐piperaquine (RR 0.32, 95% CI 0.24 to 0.43; four trials, 1442 participants) and artesunate plus mefloquine (RR 0.30, 95% CI 0.21 to 0.41; four trials, 1003 participants) were more effective than artemether‐lumefantrine at reducing the incidence of P.vivax over 42 days follow up.

Authors' conclusions

Dihydroartemisinin‐piperaquine is another effective first‐line treatment for P. falciparum malaria.

The performance of the non‐ACT (amodiaquine plus sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine) falls below WHO recommendations for first‐line therapy in parts of Africa.

In areas where primaquine is not being used for radical cure of P. vivax, ACTs with long half‐lives may provide some benefit.

23 April 2019

No update planned

Review superseded

Please refer to the Cochrane Special Collection: Sinclair 2014 https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.SC000007/full

Plain language summary

Artemisinin‐based combination treatments for uncomplicated malaria

Malaria is a major cause of illness and death in many of the world's poorest countries. It is spread from person to person by the bite of mosquitoes infected with a microorganism called Plasmodium. The Plasmodium species P. falciparum is the most common cause of malaria worldwide and causes the majority of deaths. Uncomplicated malaria is the mild form of the disease which, if left untreated, can progress rapidly to become life threatening. The drugs traditionally used to treat uncomplicated malaria have become ineffective in many parts of the world due to the development of drug resistance.

The World Health Organization now recommends Artemisinin‐based Combination Therapy (ACTs) for treating uncomplicated malaria. The ACTs combine an artemisinin‐derivative (a relatively new group of drugs which are very effective) with another longer‐lasting drug to try and reduce the risk of further resistance developing.

This review summarizes the relative benefits and harms of the four ACTs in common use, one relatively new ACT (dihydroartemisinin plus piperaquine), and one combination which does not contain an artemisinin derivative but remains in use in some African countries (amodiaquine plus sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine).

All five ACTs were shown to be highly effective at treating P. falciparum in most places where they have been studied. However, there were several trials where ACTs had high levels of treatment failure, which emphasises the need to continue to monitor their performance.

The new ACT, dihydroartemisinin plus piperaquine, was shown to be at least as effective as the ACTs currently in widespread use in Asia and Africa, and represents another option for malaria treatment.

ACTs were shown to be more effective than amodiaquine plus sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine in countries from East Africa which probably represents high levels of resistance, to both drugs in this combination, in this region.

The second most common form of malaria, P. vivax, can also be treated with ACTs but requires additional treatment to cure the patient completely. This is because the P. vivax parasite can lie dormant in the liver for months or years before becoming active again. ACTs where the partner drug has a long duration of action may help to delay these relapses.

The ACTs seem to be relatively safe with few serious side effects. Minor side effects are more common but can be difficult to distinguish from the symptoms of malaria itself. Fifty trials were included in this review but did not include the most vulnerable populations; pregnant women and young infants (age < six months).

Background

Malaria is a disease of global public health importance. Its social and economic burden is a major obstacle to human development in many of the world's poorest countries. In heavily affected countries, malaria alone accounts for as much as 40% of public health expenditure, 30% to 50% of hospital admissions, and up to 60% of outpatient visits (WHO 2007). It has an annual incidence of approximately 250 million episodes and is the cause of more than a million deaths, most of them in infants, young children, and pregnant women (WHO 2008b).

Malaria is transmitted from person to person by the bite of mosquitoes infected with the protozoan parasite Plasmodium. Four Plasmodium species are capable of causing malaria in humans: P. falciparum, P. vivax, P. malariae, and P. ovale. Of these P. falciparum is responsible for over 90% of cases and almost all of the malaria deaths worldwide (WHO 2008b). P. vivax is also common and often presents as a co‐infection with P. falciparum in a single illness (Mayxay 2004). Uncomplicated malaria is the mild form of the disease which presents as a febrile illness with headache, tiredness, muscle pains, abdominal pains, rigors (severe shivering), and nausea and vomiting. If left untreated P. falciparum malaria can rapidly develop into severe malaria with anaemia (low haemoglobin in the blood), hypoglycaemia (low blood sugar), renal failure (kidney failure), pulmonary oedema (fluid in the lungs), convulsions (fitting), coma, and eventually death (WHO 2006). A clinical diagnosis of malaria can be confirmed by detection of the malaria parasite in the patient's blood. This has traditionally been done by light microscopy but increasingly rapid diagnostic tests are being used.

Resistance of P. falciparum to the traditional antimalarial drugs (such as chloroquine, sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine, amodiaquine, and mefloquine) is a growing problem and is thought to have contributed to increased malaria mortality in recent years (WHO 2006). Chloroquine resistance has now been documented in all regions except Central America and the Caribbean. There is high‐level resistance to sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine throughout South East Asia and increasingly in Africa. Mefloquine resistance is common in the border areas of Cambodia, Myanmar, and Thailand, but uncommon elsewhere. Resistance of P. vivax to sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine is also increasing, and chloroquine resistance has been reported in some parts of Asia and Oceania (WHO 2006).

Artemisinin‐based antimalarials

Artemisinin and its derivatives (such as artesunate, artemether, and dihydroartemisinin) are antimalarial drugs with a unique structure and mode of action. The first published report of clinical trials appeared in the Chinese Medical Journal in 1979 (Qinghaosu 1979). Until recently there had been no reported resistance to the artemisinin derivatives; however the possibility of emerging resistance, on the Thai‐Cambodian border, is currently being investigated (WHO 2008a).

Artemisinin derivatives have been shown to produce faster relief of clinical symptoms and faster clearance of parasites from the blood than other antimalarial drugs (McIntosh 1999; Adjuik 2004; WHO 2006). When used as monotherapy, the short half‐life of the artemisinin derivatives (and rapid elimination from the blood) means that patients must take the drug for at least seven days (Meshnick 1996; Adjuik 2004). Failure to complete the course, due to the rapid improvement in clinical symptoms, can lead to high levels of treatment failure even in the absence of drug resistance. Artemisinin derivatives are therefore usually given with another longer‐acting drug, with a different mode of action, in a combination known as artemisinin‐based combination therapy or ACT. These combinations can then be taken for shorter durations than artemisinin alone (White 1999; WHO 2006).

The artemisinin derivatives also reduce the development of gametocytes (the sexual form of the malaria parasite that is capable of infecting mosquitoes) and consequently the carriage of gametocytes in the peripheral blood (Price 1996; Targett 2001). This reduction in infectivity has the potential to reduce the post‐treatment transmission of malaria (particularly in areas of low or seasonal transmission), which may have significant public health benefits (WHO 2006).

Artemisinin and its derivatives are generally reported as being safe and well tolerated, and the safety profile of ACTs may be largely determined by the partner drug (WHO 2006; Nosten 2007). Studies of artemisinin derivatives in animals have reported significant neurotoxicity (brain damage), but this has not been seen in human studies (Price 1999). Animal studies have also shown adverse effects on the early development of the fetus, but the artemisinin derivatives have not been fully evaluated during early pregnancy in humans (Nosten 2007). Other reported adverse events include gastrointestinal (GI) disturbance (stomach upset), dizziness, tinnitus (ringing in the ears), neutropenia (low levels of white blood cells), elevated liver enzymes (a marker for liver damage), and electrocardiographic (ECG) abnormalities (changes in cardiac conduction). Most studies however, have found no evidence of ECG changes, and only non‐significant changes in liver enzymes (WHO 2006; Nosten 2007). The incidence of type 1 hypersensitivity (allergic) reactions is reported to be approximately 1 in 3000 patients (Nosten 2007).

Assessing antimalarial efficacy

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that first‐line antimalarials should have a treatment failure rate of less than 10%, and failure rates higher than this should trigger a change in treatment policy (WHO 2006). Treatment failure can be classified as:

Early treatment failure:

the development of danger signs or severe malaria on days one, two, three in the presence of parasitaemia;

parasitaemia on day two higher than on day 0;

parasitaemia and axillary temperature > 37.5 °C on day three;

parasitaemia on day three > 20% of count on day 0.

or late treatment failure:

development of danger signs, or severe malaria, after day three with parasitaemia;

presence of P. falciparum parasitaemia and axillary temperature > 37.5 °C on or after day four;

presence of P. falciparum parasitaemia after day seven.

The late reappearance of P. falciparum parasites in the blood can be due to failure of the drug to completely clear the original parasite (a recrudescence) or due to a new infection, which is especially common in areas of high transmission. A molecular genotyping technique called polymerase chain reaction (PCR) can be used in clinical trials to distinguish between recrudescence and new infection, giving a clearer picture of the efficacy of the drug and its post‐treatment prophylactic effect (White 2002; Cattamanchi 2003).

The WHO recommends a minimum follow‐up period of 28 days for antimalarial efficacy trials, but longer periods of follow up may be required for antimalarials with long elimination half‐lives (White 2002; WHO 2003). This is because treatment failure due to true recrudescence of malaria parasites may be delayed until the drug concentration falls below the minimum concentration required to inhibit parasite multiplication, which may be beyond 28 days. The WHO recommends 42 days follow up for trials involving lumefantrine and 63 days for trials of mefloquine (WHO 2003).

P. vivax malaria

P. vivax differs from P. falciparum in generally producing a milder illness and in having a liver stage known as a hypnozoite. These hypnozoites can lie dormant in the liver following an acute infection and cause spontaneous relapses at later dates.

As P. vivax often co‐exists with P. falciparum in a single illness, it is important to assess the effect of ACTs on the P. vivax parasite (Mayxay 2004; WHO 2006). ACTs have been shown to clear P. vivax from the peripheral blood, but they do not have a substantial effect on the liver stage of the parasite (Pukrittayakamee 2000). Although ACTs cannot provide a radical cure for P. vivax, their ability to delay the eventual relapse of P. vivax and provide a prolonged malaria free period may produce significant public health benefits.

It is important to note that when P. vivax parasitaemia occurs following initial treatment, PCR is unable to distinguish a recrudescence of the original infection (due to failure to clear the parasite from the peripheral blood) from a spontaneous relapse (due to failure to clear the liver stage) (WHO 2006).

Choice of combination treatment

The WHO now recommends that P. falciparum malaria is always treated using a combination of two drugs that act at different biochemical sites within the parasite (WHO 2006). If a parasite mutation producing resistance arises spontaneously during treatment, the parasite should then be killed by the partner drug, thereby reducing or delaying the development of resistance to the artemisinin derivatives, and increasing the useful lifetime of the individual drugs (White 1996; White 1999; WHO 2006). This policy emerged at the time when ACTs were primarily being considered, but other possibilities such as amodiaquine combined with sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine (non‐ACTs) are also available.

The decision of which ACT to adopt into national malaria control programmes has been based on a combination of research and expert opinion. Systematic reviews can contribute to this decision by providing evidence on the:

relative effects on cure between combinations;

absolute cure levels achieved by a drug in a particular region;

safety and risk of adverse effects of the combination;

impact on gametocytes;

impact on haemoglobin levels; and

relative effects on P. vivax.

Other information that is also important to decision‐making include:

the appropriateness of the partner drug within a locality, based on informed judgements related to regional and national overviews of drug resistance and the intensity of malaria transmission;

the simplicity of the treatment regimen (co‐formulated products are generally preferred as they reduce the availability and use of monotherapy, which may in turn reduce the development of resistance);

the cost (since the ACT is likely to represent a large percentage of the annual health expenditure in highly endemic countries); and

other concerns such as fetal toxicity and teratogenicity.

To contribute to informed decision‐making, we have examined the comparative effects of ACTs for which co‐formulated products are currently available or shortly to be made available. We have included trials that have used co‐packaged or loose preparations of these same ACTs to provide information on relative effects of the different treatment options. While recent Cochrane Reviews have synthesized the evidence around individual ACT comparisons (Bukirwa 2005; Omari 2005; Bukirwa 2006; Omari 2006), this review broadens the inclusion criteria and pools the data into a single Cochrane Review. A comprehensive list of the available drugs and the treatment comparisons that have been assessed is shown in Appendix 1. The data are presented in answer to four questions:

How does dihydroartemisinin‐piperaquine (DHA‐P) perform?

How does artesunate‐mefloquine (AS+MQ) perform?

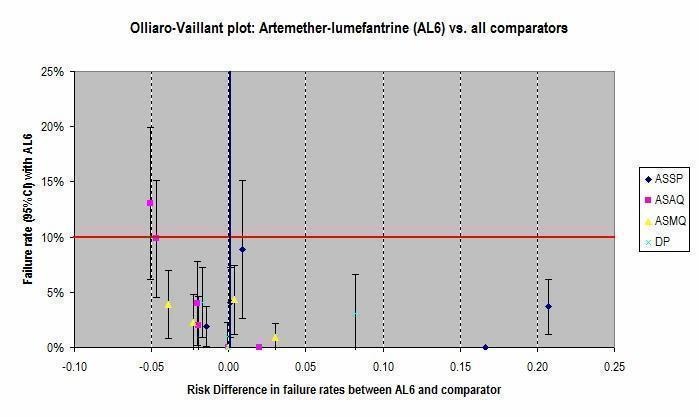

How does artemether‐lumefantrine (AL6) perform?

How does artesunate plus amodiaquine (AS+AQ) perform?

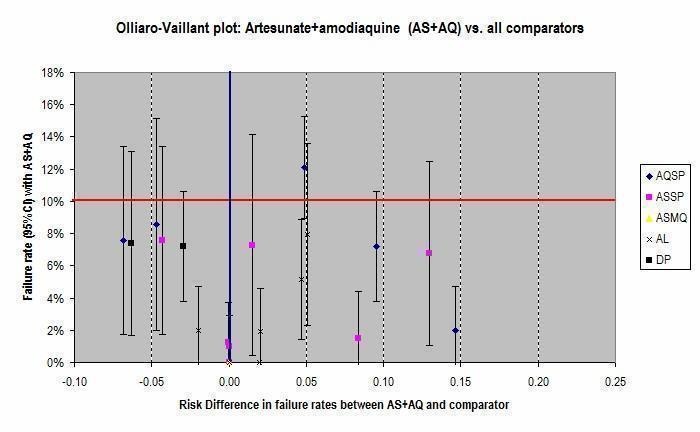

The comparison drugs were any of the above plus artesunate plus sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine (AS+SP) and amodiaquine plus sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine (AQ+SP).

Objectives

To compare the effects of ACTs with other available ACT and non‐ACT combinations for treating uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria.

A secondary objective was to explore the effects of the combinations on P. vivax infection.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomized controlled trials. Quasi‐randomized studies were excluded.

Types of participants

Adults and children (including pregnant women and infants) with symptomatic, microscopically confirmed, uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria.

Trials that included participants with P. vivax co‐infection and mono‐infection were also eligible.

Types of interventions

Intervention

Three‐day course of an ACT (fixed dosed, co‐blistered, or individually packaged (loose)).

Control

Three‐day course of an alternative ACT or non‐artemisinin combination treatment (amodiaquine plus sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine).

The specific ACTs included are: dihydroartemisinin‐piperaquine; artesunate plus mefloquine; artemether‐lumefantrine (six doses); artesunate plus amodiaquine and artesunate plus sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine (Appendix 1).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Total failure at days 28, 42, and 63; PCR‐adjusted and PCR‐unadjusted.

Secondary outcomes

P. vivax parasitaemia at day 28, 42, or 63 (all participants).

P. vivax parasitaemia at day 28, 42, or 63 (only participants with P. vivax at baseline).

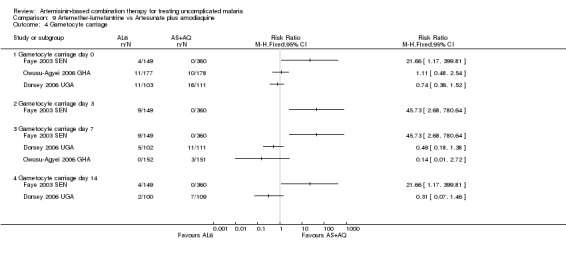

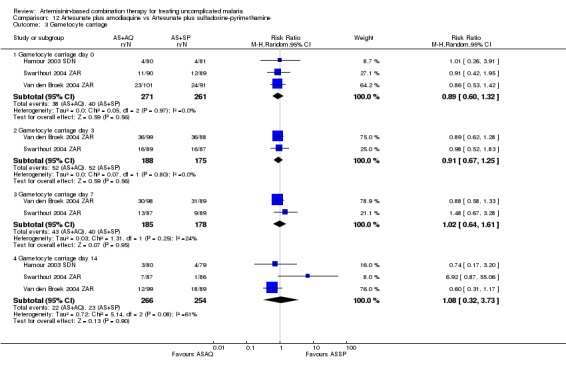

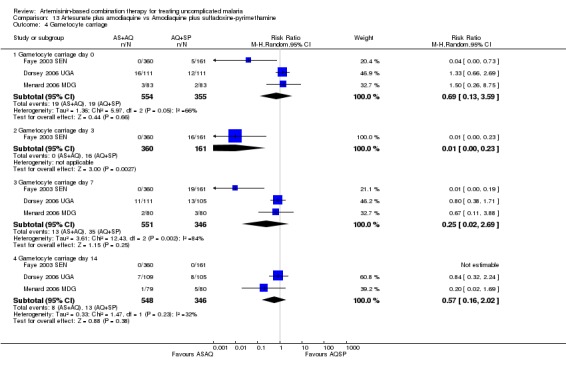

Gametocyte carriage at day 7 or 14 (preference for day 14 in data analysis).

Gametocyte development (negative at baseline, and positive at follow up).

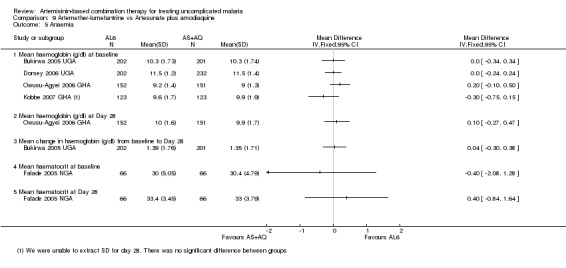

Change in haemoglobin from baseline (minimum 28 day follow up).

Adverse events

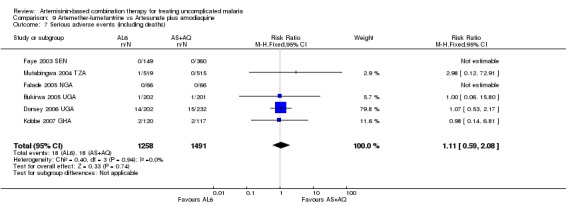

Deaths occurring during follow up.

Serious adverse events (life threatening, causing admission to hospital, or discontinuation of treatment).

Haematological and biochemical adverse effects (e.g. neutropenia, liver toxicity).

Early vomiting.

Other adverse events.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases using the search terms detailed in Appendix 2: Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group Specialized Register (March 2009); Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) published in The Cochrane Library (2009, issue 1); MEDLINE (1966 to March 2009); EMBASE (1974 to March 2009); and LILACS (1982 to March 2009). We also searched the metaRegister of Controlled Trials (mRCT) using 'malaria' and 'arte* OR dihydroarte*' as search terms (March 2009).

Searching other resources

We contacted individual researchers working in the field, organizations including the World Health Organization, and pharmaceutical companies (Atlantic, Guilin, Holleykin, HolleyPharm, Mepha, Novartis, Parke‐Davis, Pfizer, Sanofi‐Aventis, Roche) for information on unpublished trials (August 2008).

We also checked the reference lists of all trials identified by the methods described above.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

David Sinclair (DS) and Babalwa Zani (BZ) reviewed the results of the literature search and obtained full‐text copies of all potentially relevant trials. DS scrutinized each trial report for evidence of multiple publications from the same data set. DS and BZ then independently assessed each trial for inclusion in this review using an eligibility form based on the inclusion criteria. We resolved any disagreements through discussion or, where necessary, by consultation with Paul Garner (PG). If clarification was necessary we attempted to contact the trial authors for further information. We have listed the trials that were deemed ineligible and the reasons for their exclusion in the 'Characteristics of excluded studies' table.

Data extraction and management

DS and BZ independently extracted data using a pre‐tested data extraction form. We extracted data on trial characteristics including methods, participants, interventions, and outcomes as well as data on dose and drug ratios of the combinations.

We extracted the number randomized and the number analysed in each treatment group for each outcome. We calculated and reported the loss to follow up in each group.

For dichotomous outcomes, we recorded the number of participants experiencing the event and the number of participants in each treatment group. For continuous outcomes, we extracted the arithmetic means and standard deviations for each treatment group together with the numbers of participants in each group. If the data were reported using geometric means, we recorded this information and extracted standard deviations on the log scale. If medians were extracted we also extracted ranges.

Primary outcome

The primary analysis drew on the WHO's protocol for assessing and monitoring antimalarial drug efficacy (WHO 2003). This protocol has been used to guide most efficacy trials since its publication in 2003, even though it was designed to assess the level of antimalarial resistance in the study area rather than for comparative trials. As a consequence a high number of randomized participants are excluded from the final efficacy outcome as losses to follow up or voluntary or involuntary withdrawals. For this reason we conducted a sensitivity analysis which aimed to restore the integrity of the randomization process (as is usual in trial analysis) and test the robustness of the results to this methodology. (For a summary of the methodology and sensitivity analysis see Appendix 3)

PCR‐unadjusted total failure

PCR‐unadjusted total failure (P. falciparum) was calculated as the sum of early treatment failures and late treatment failures (without PCR adjustment). The denominator excludes participants for whom an outcome was not available (e.g. those who were lost to follow up, withdrew consent, took other antimalarials, or failed to complete treatment) and those participants who were found not to fulfil the inclusion criteria after randomization.

PCR‐adjusted total failure

PCR‐adjusted total failure (P. falciparum) was calculated as the sum of early treatment failures, and late treatment failures due to PCR‐confirmed recrudescence. Participants with indeterminate PCR results, missing PCR results, or PCR‐confirmed new infections were treated as involuntary withdrawals and excluded from the calculation. Late treatment failures that occurred between days 4 and 14 were assumed to be recrudescences of the original parasite without the need for PCR genotyping (unless genotyped in the trial). The denominator excludes participants for whom an outcome was not available (e.g. those who were lost to follow up, withdrew consent, took other antimalarials, or failed to complete treatment) and those participants who were found not to fulfil the inclusion criteria after randomization.

These primary outcomes relate solely to failure due to P. falciparum. For both PCR‐unadjusted and PCR‐adjusted total failure, participants who experienced P. vivax during follow up were retained in the calculation if they were treated with chloroquine and continued in follow up. As long as they did not go on to develop P. falciparum parasitaemia they were classified as treatment successes. We excluded from the calculation those participants who experienced P. vivax and were removed from the trial's follow up at the time of P. vivax parasitaemia.

It was not always possible to guarantee that individual trials used the standard WHO definitions. We have accepted the trial authors' data unless we had specific reason to reclassify an individual participant or reject the data. Where this has been done we have stated clearly the reasons for doing so.

Secondary outcomes and adverse events

In a secondary analysis we examined the effects of ACTs on P. vivax. We have reported the incidence of P. vivax parasitaemia during follow up at days 28, 42, and 63. Where possible, we have stratified this analysis into participants who had P. vivax co‐infection at baseline and those negative for P. vivax at baseline.

Extracting data on gametocyte carriage was difficult due to the variety of ways that these data are presented in individual papers. In order to try to present useful data we contacted the lead author of all trials that reported on gametocytes for additional information which fitted our specified outcomes.

Haematological outcomes were also presented in a multitude of ways which prevented meta‐analysis. We have therefore presented these data as a narrative summary with forest plots where possible.

Other secondary outcomes have been presented using forest plots, tables, or narrative summaries as appropriate.

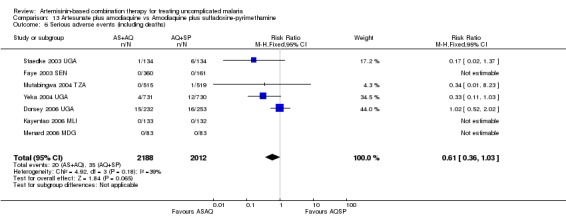

We extracted the number of serious adverse events and deaths and have presented these data in a forest plot. We have only included those trials that specifically report serious adverse events.

Data on early vomiting were extracted as a measure of tolerability of these combinations, and are presented as a forest plot. Other adverse events are presented in tables with a narrative summary.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

DS and BZ independently assessed the risk of bias for each trial using 'The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing the risk of bias' (Higgins 2008). Differences of opinion were discussed with PG. We followed the guidance to assess whether adequate steps had been taken to reduce the risk of bias across six domains: sequence generation; allocation concealment; blinding (of participants, personnel, and outcome assessors); incomplete outcome data; selective outcome reporting; and other sources of bias. We have categorized these judgments as 'yes' (low risk of bias), 'no' (high risk of bias), or 'unclear'. Where our judgement is unclear we attempted to contact the trial authors for clarification.

This information was used to guide the interpretation of the data that are presented.

Measures of treatment effect

We analysed the data using Review Manager 5. Dichotomous data are presented and combined using risk ratios. For continuous data summarized by arithmetic means and standard deviations, data have been combined using mean differences. Risk ratios and mean differences are accompanied by 95% confidence intervals. Medians and ranges are only reported in tables.

Dealing with missing data

If data from the trial reports were insufficient, unclear, or missing, we attempted to contact the trial authors for additional information. If we judged the missing data to render the result uninterpretable we excluded the data from the meta‐analysis and clearly stated the reason. The potential effects of missing data have been explored through a series of sensitivity analyses (Appendix 3).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed for heterogeneity amongst trials by inspecting the forest plots, applying the Chi² test with a 10% level of statistical significance, and also using the I² statistic with a value of 50% used to denote moderate levels of heterogeneity.

Data synthesis

The included trials have been given identity codes which include the first author, the year the study was conducted (not the year it was published) and the three‐letter international country code. Studies in forest plots are also listed in chronological order (by the final date of enrolment). We hope this will aid with interpretation of the review and forest plots.

Treatments have been compared directly using pair‐wise comparisons. For outcomes that are measured at different time points we have stratified the analysis by the time point. The primary outcome analysis is also stratified by geographical region as a crude marker for differences in transmission and resistance patterns.

Meta‐analysis has been performed within geographic regions where appropriate after assessment and investigation of heterogeneity. A random‐effects model was used where the Chi² test P value was less than 0.1 or the I² statistic was greater than 50%.

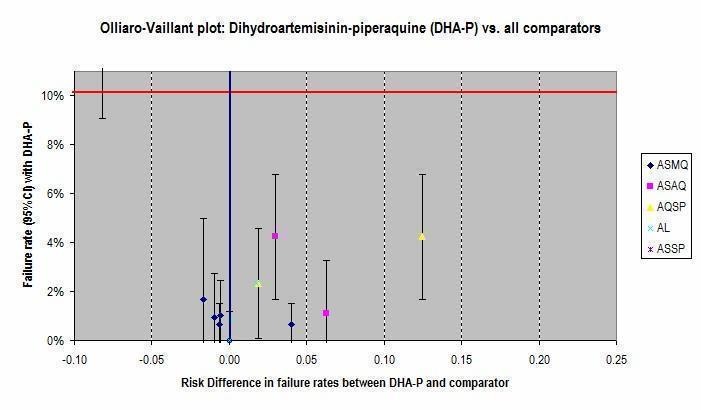

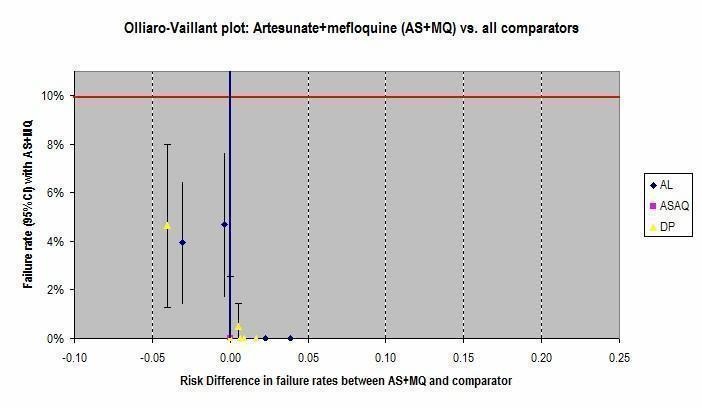

In addition, Olliaro‐Vaillant plots have been used to simultaneously display the absolute and relative benefits of individual ACTs at day 28.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We investigated potential sources of heterogeneity through the following subgroup analyses: geographical region, intensity of malaria transmission (low to moderate versus high malaria transmission), known parasite resistance, allocation concealment, participant age, and drug dose (comparing regimens where there are significant variations in drug dose).

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted a series of sensitivity analyses to investigate the robustness of the methodology used in the primary analysis. Our aim was to restore the integrity of the randomization process by adding excluded groups back into the analysis in a stepwise fashion (see Appendix 3 for details). Where these analyses altered the direction or significance of the measure of effect the revised results are presented and discussed.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The search was conducted on 12 August 2008 and repeated on 26 March 2009. In total 517 trials were identified. Full text copies were obtained for 85 trials. Fifty trials are included in this review and 35 were excluded. A further four trials (Bousema 2004 KEN; Koram 2003 GHA; Martensson 2003 TZA; Van den Broek 2004 ZAR) were excluded from the primary analysis due to baseline differences between groups which had the potential to severely bias the result. These trials were retained for their data on adverse events.

Included studies

Forty‐six of the fifty included trials were conducted between 2003 and 2009.

Thirty‐one trials were conducted in Africa, 17 in Asia, one in South America (DHA‐P versus AS+MQ) and one in Oceania (DHA‐P versus AL6 versus AS+SP). There is obvious regional variability in which drugs are being studied. Trials from Asia mainly involve AS+MQ, AL6 and DHA‐P (plus one trial from Indonesia with AS+AQ). Only two studies from Africa have evaluated AS+MQ.

Pregnant and lactating women were excluded from all trials. The study population in Asian trials is older, with exclusion of children aged less than one year. African studies concentrated more on children and included those as young as six months.

Three trials (Hasugian 2005 IDN; Karunajeewa 2007 PNG; Ratcliff 2005 IDN) included participants with P. vivax mono‐infection at baseline. For our primary analysis we obtained data from the authors for only those participants who had P. falciparum or mixed infection (falciparum andvivax) at baseline.

One trial (Dorsey 2006 UGA) had an unusual study design where participants were followed up for more than one episode of malaria. For our primary analysis we obtained data from the authors for first episodes of malaria only.

The characteristics of the included studies are given in the 'Characteristics of included studies' table.

Excluded studies

The reasons for exclusion are given in the 'Characteristics of excluded studies' table.

The four additional studies excluded from the primary analysis had different inclusion criteria for different arms of the trial. Children aged less than one year were excluded from the AL6 treatment arm and reassigned to either AS+AQ or AS+SP. In these studies this led to significant baseline differences in age and weight, factors known to be associated with the outcomes. We explored the effects of including these trials in the largest meta‐analysis (AL6 versus AS+AQ, Analysis 9.9; Analysis 9.10). Inclusion of the trials with this bias shifted the results from no difference detected to favouring AL6. In the light of this we decided to exclude all trials that had systematically reallocated patients after randomization.

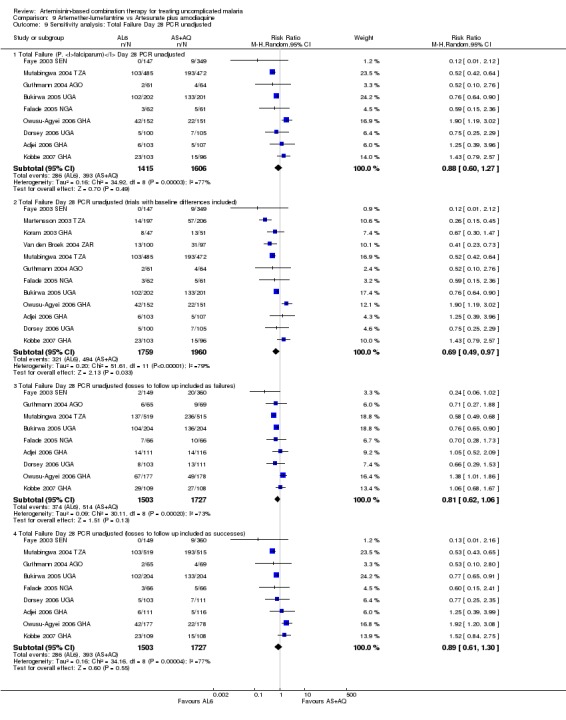

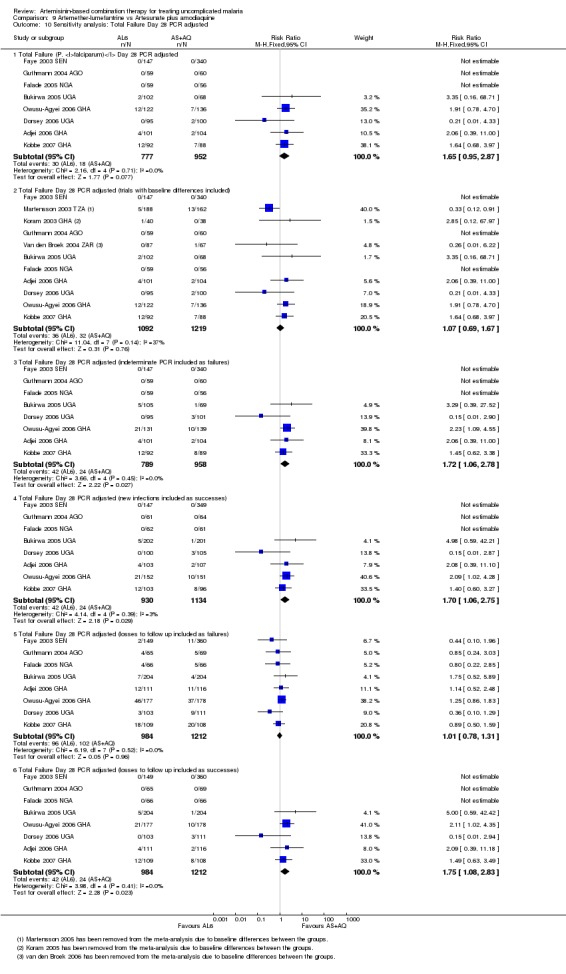

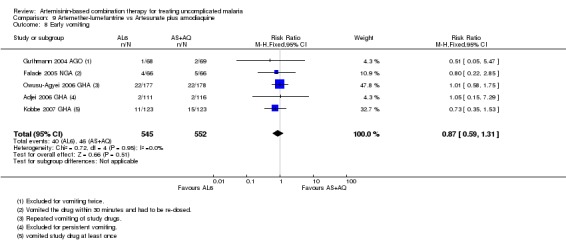

9.9. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Artemether‐lumefantrine vs Artesunate plus amodiaquine, Outcome 9 Sensitivity analysis: Total Failure Day 28 PCR unadjusted.

9.10. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Artemether‐lumefantrine vs Artesunate plus amodiaquine, Outcome 10 Sensitivity analysis: Total Failure Day 28 PCR adjusted.

Risk of bias in included studies

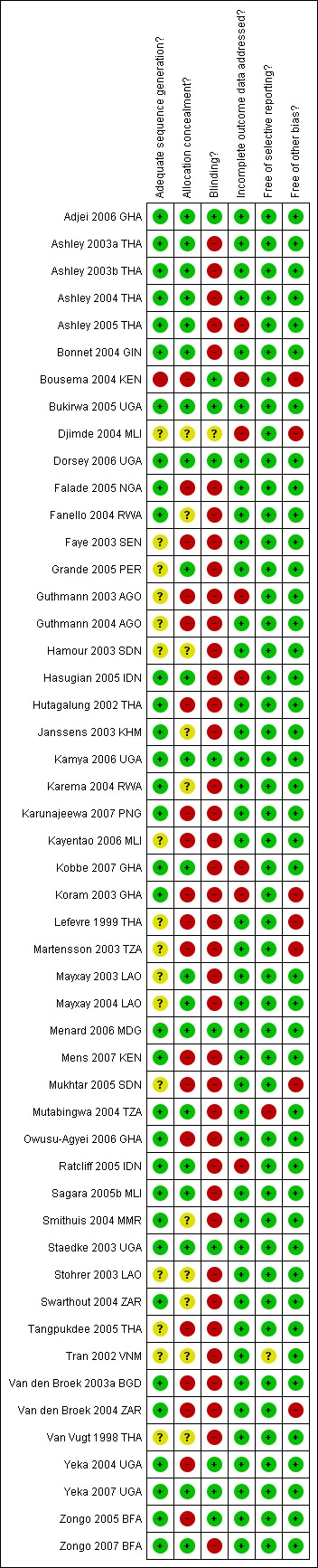

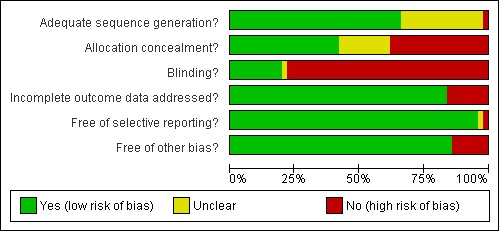

For a summary of the 'Risk of bias' assessments please see Figure 1 and Figure 2.

1.

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

2.

Methodological quality graph: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Allocation

Generation of the randomized sequence was judged to be at low risk of bias for 33 trials, high risk of bias for 1 trial, and 16 trials were unclear regarding randomization methods.

Allocation concealment was judged to be at low risk of bias in 21 studies, high risk of bias in 19 studies and unclear in 10 studies. Descriptions which included the following details were accepted as adequate for concealment: opaque sealed envelopes; sealed sequentially numbered envelopes; or third party allocation. For primary outcomes we conducted a sensitivity analysis including only the trials with adequate allocation concealment.

Blinding

Of the included trials only 10 were judged to be at low risk of bias due to adequate blinding. Blinding or quality control of laboratory staff was conducted in 34 studies. Although this may be reassuring with regard to parasitological outcomes, secondary outcomes and particularly adverse event reporting will remain at high risk of bias.

Incomplete outcome data

We have reported the proportion of participants in each treatment arm for whom an outcome was not available and conducted sensitivity analyses to test the possible effect of these losses. Eight trials were judged to be at high risk of bias due to either moderate drop‐out (> 15%), differential drop‐out between groups that had the potential to alter the result, or participants missing from the primary analysis who could not be accounted for.

Selective reporting

Due to the varying half‐lives of drugs, the choice of which day to measure outcomes can influence the comparative effects of the drugs. If a drug with a long half‐life (DHA‐P or AS+MQ) is compared to a drug with a short half‐life (AS+AQ or AS+SP), day 28 outcomes may underestimate PCR adjusted failure with the long half‐life drug. At later time points (day 42 and 63) drugs with long half‐lives are likely to appear superior in preventing new infections (PCR unadjusted failure) which represents a prophylactic effect. We have kept this in mind when interpreting the data but did not judge the trials to be at high risk of bias.

Other potential sources of bias

Pharmaceutical companies provided financial support or study drugs in 15 trials. Further involvement of the pharmaceutical company in trial design or reporting is only described in one study (Djimde 2004 MLI).

Effects of interventions

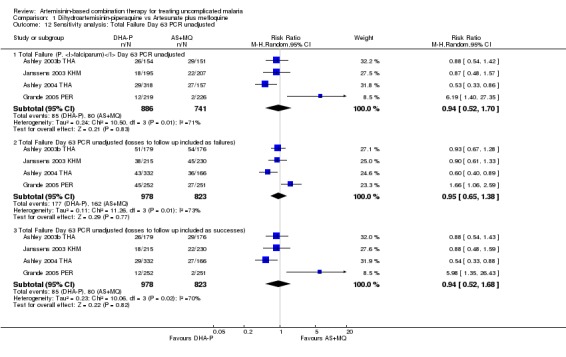

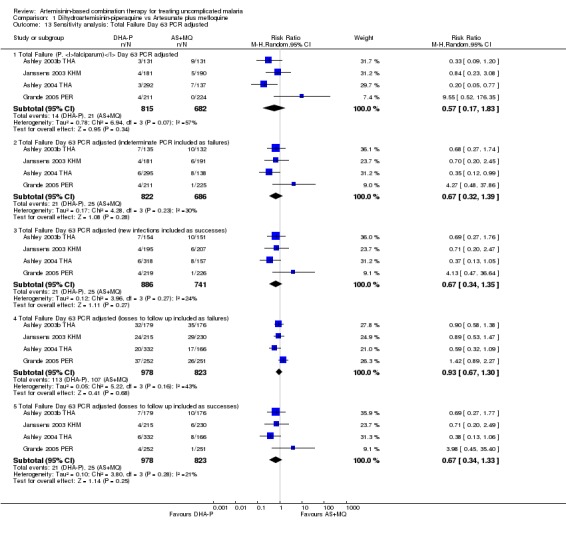

In April 2009 we conducted the sensitivity analysis as described in Table 3 to test the robustness of our methodology. In general these analyses did not substantially change the direction, magnitude, or confidence intervals of the estimate of effect. Examples are shown in Analysis 1.12 and Analysis 1.13. Only sensitivity analyses of interest remain linked in this review.

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Dihydroartemisinin‐piperaquine vs Artesunate plus mefloquine, Outcome 12 Sensitivity analysis: Total Failure Day 63 PCR unadjusted.

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Dihydroartemisinin‐piperaquine vs Artesunate plus mefloquine, Outcome 13 Sensitivity analysis: Total Failure Day 63 PCR adjusted.

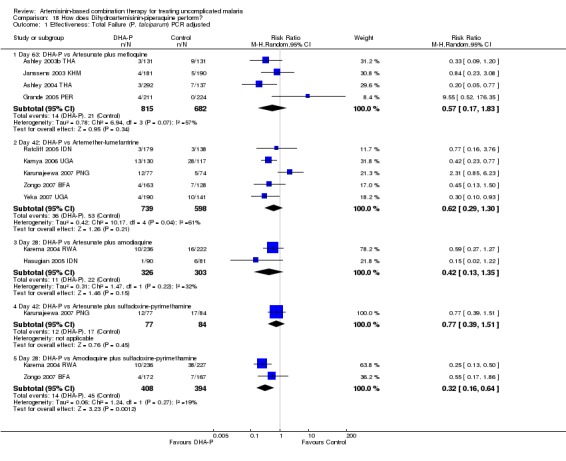

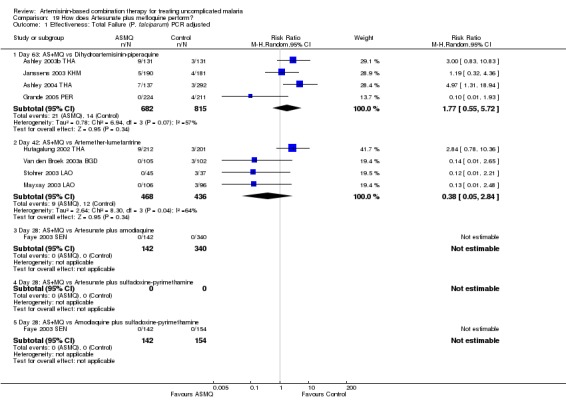

Question 1. How does dihydroartemisinin‐piperaquine (DHA‐P) perform?

Dosing concerns

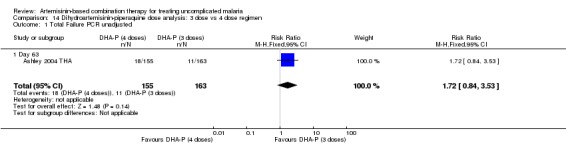

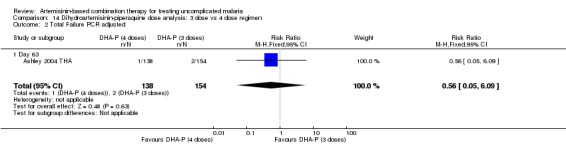

Two dosing regimens have been commonly used in clinical trials of DHA‐P. These two regimens give the same total dose, but divided into three or four doses, given over three days. One trial (Ashley 2004 THA) directly compared the three‐dose regimen with the four‐dose regimen and found no difference at any time point (one trial, 318 participants, Analysis 14.1, Analysis 14.2).

14.1. Analysis.

Comparison 14 Dihydroartemisinin‐piperaquine dose analysis: 3 dose vs 4 dose regimen, Outcome 1 Total Failure PCR unadjusted.

14.2. Analysis.

Comparison 14 Dihydroartemisinin‐piperaquine dose analysis: 3 dose vs 4 dose regimen, Outcome 2 Total Failure PCR adjusted.

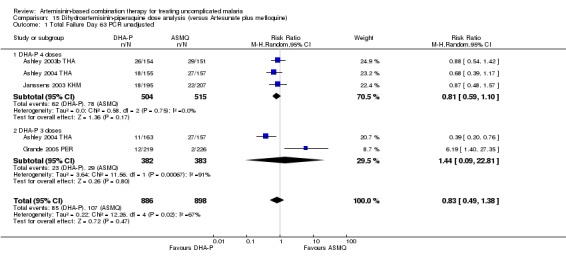

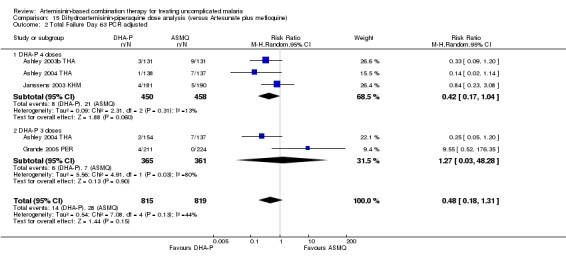

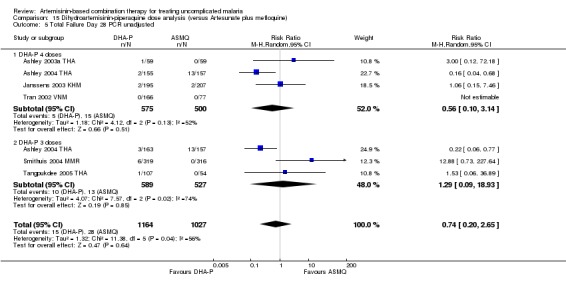

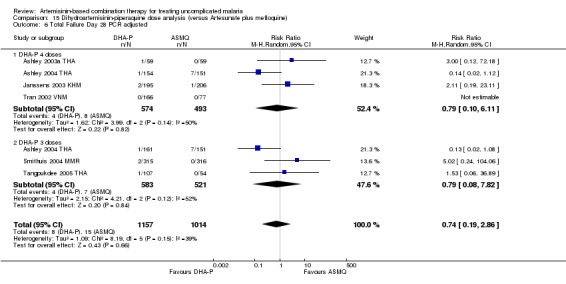

In comparisons comparing DHA‐P to AS+MQ, four trials used the three‐dose regimen, three trials used the four‐dose regimen and one trial used both. Stratifying the analysis by dosing regimen did not reveal any significant differences in efficacy between the two regimens (Analysis 15.1; Analysis 15.2; Analysis 15.3; Analysis 15.4; Analysis 15.5; Analysis 15.6).

15.1. Analysis.

Comparison 15 Dihydroartemisinin‐piperaquine dose analysis (versus Artesunate plus mefloquine), Outcome 1 Total Failure Day 63 PCR unadjusted.

15.2. Analysis.

Comparison 15 Dihydroartemisinin‐piperaquine dose analysis (versus Artesunate plus mefloquine), Outcome 2 Total Failure Day 63 PCR adjusted.

15.3. Analysis.

Comparison 15 Dihydroartemisinin‐piperaquine dose analysis (versus Artesunate plus mefloquine), Outcome 3 Total Failure Day 42 PCR unadjusted.

15.4. Analysis.

Comparison 15 Dihydroartemisinin‐piperaquine dose analysis (versus Artesunate plus mefloquine), Outcome 4 Total Failure Day 42 PCR adjusted.

15.5. Analysis.

Comparison 15 Dihydroartemisinin‐piperaquine dose analysis (versus Artesunate plus mefloquine), Outcome 5 Total Failure Day 28 PCR unadjusted.

15.6. Analysis.

Comparison 15 Dihydroartemisinin‐piperaquine dose analysis (versus Artesunate plus mefloquine), Outcome 6 Total Failure Day 28 PCR adjusted.

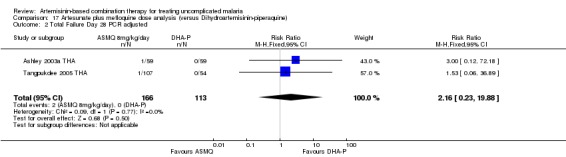

Comparison 1. DHA‐P versus artesunate plus mefloquine

We found nine trials which assessed this comparison (eight in Asia and one in South America). Allocation concealment was assessed as 'low risk of bias' in five trials (Ashley 2003a THA; Ashley 2003b THA; Ashley 2004 THA; Grande 2005 PER; Mayxay 2004 LAO). Laboratory staff (outcome assessors) were blinded to treatment allocation in three trials (Ashley 2003a THA; Ashley 2003b THA; Ashley 2005 THA), and no other blinding is described.

Total failure

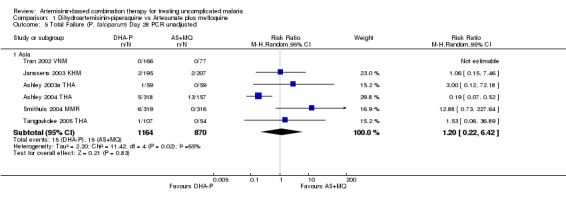

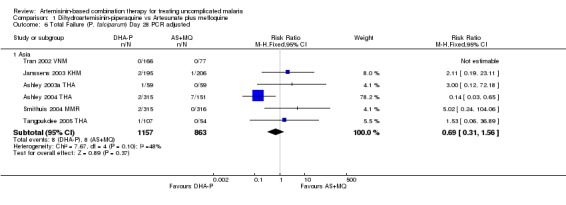

PCR adjusted treatment failure with DHA‐P was below 5% in all nine studies, and with AS+MQ in seven out of nine studies.

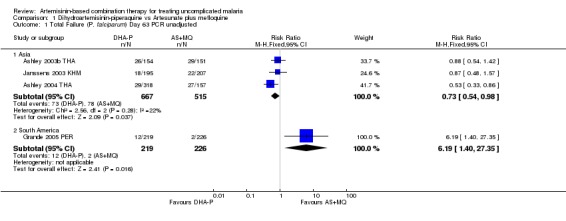

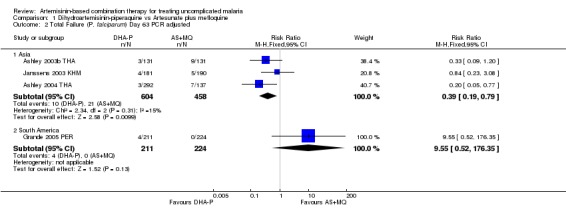

At day 63 comparative results were mixed. Trials from Asia favoured DHA‐P (Day 63, three trials, 1182 participants: PCR unadjusted RR 0.73, 95% CI 0.54 to 0.98, Analysis 1.1; PCR adjusted RR 0.39, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.79, Analysis 1.2) and the one trial from South America favoured AS+MQ (one trial, 445 participants: PCR unadjusted RR 6.19, 95% CI 1.40 to 27.35, Analysis 1.1; PCR adjusted no significant difference, Analysis 1.2). This difference may reflect the level of mefloquine resistance at the study sites. The performance of DHA‐P in the study in South America is similar to that in Asia, but the performance of AS+MQ was much improved with no PCR confirmed recrudescences.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Dihydroartemisinin‐piperaquine vs Artesunate plus mefloquine, Outcome 1 Total Failure (P. falciparum) Day 63 PCR unadjusted.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Dihydroartemisinin‐piperaquine vs Artesunate plus mefloquine, Outcome 2 Total Failure (P. falciparum) Day 63 PCR adjusted.

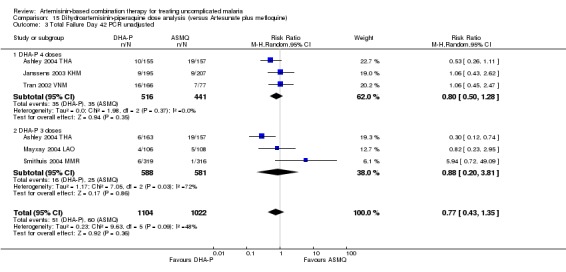

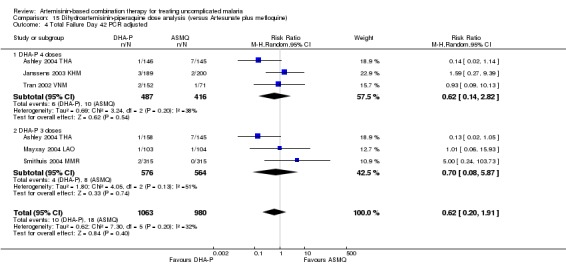

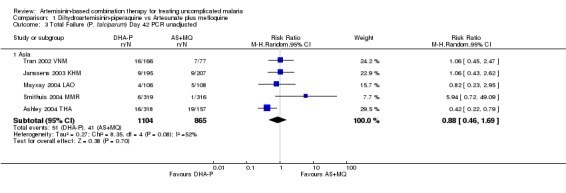

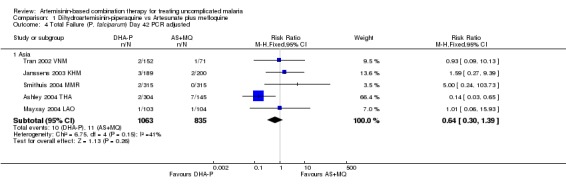

No significant differences were shown at other time points (Day 42, five trials, 1969 participants, Analysis 1.3, Analysis 1.4; Day 28, six trials, 2034 participants, Analysis 1.5, Analysis 1.6).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Dihydroartemisinin‐piperaquine vs Artesunate plus mefloquine, Outcome 3 Total Failure (P. falciparum) Day 42 PCR unadjusted.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Dihydroartemisinin‐piperaquine vs Artesunate plus mefloquine, Outcome 4 Total Failure (P. falciparum) Day 42 PCR adjusted.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Dihydroartemisinin‐piperaquine vs Artesunate plus mefloquine, Outcome 5 Total Failure (P. falciparum) Day 28 PCR unadjusted.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Dihydroartemisinin‐piperaquine vs Artesunate plus mefloquine, Outcome 6 Total Failure (P. falciparum) Day 28 PCR adjusted.

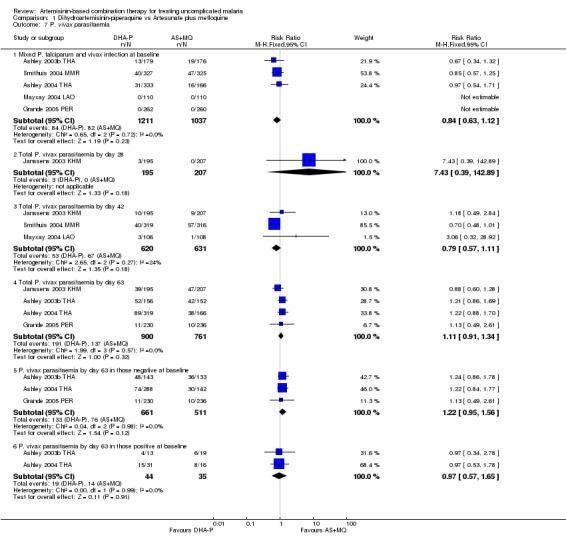

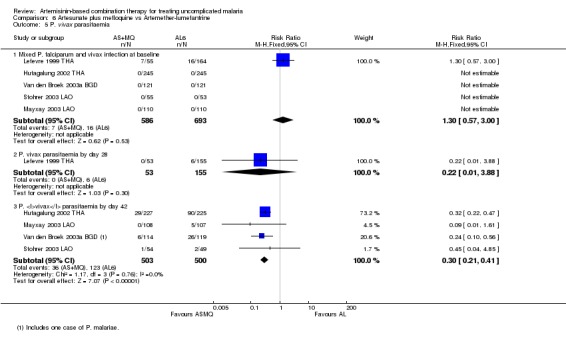

P. vivax

No significant difference was shown in the incidence of P. vivax parasitaemia at any time point (Day 63, four trials, 1661 participants; Day 42, three trials, 1251 participants; Day 28, one trial, 402 participants; Analysis 1.7). There were no significant differences in the incidence of P. vivax between groups with or without P. vivax at baseline.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Dihydroartemisinin‐piperaquine vs Artesunate plus mefloquine, Outcome 7 P. vivax parasitaemia.

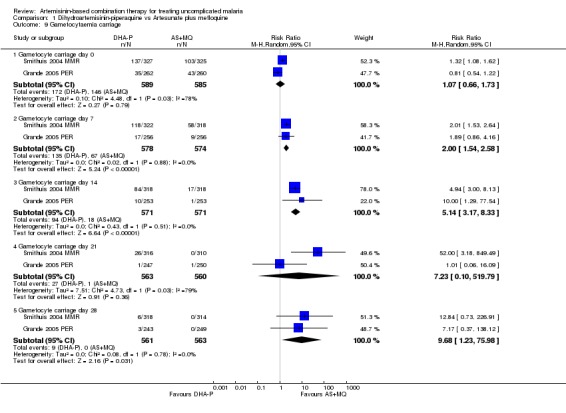

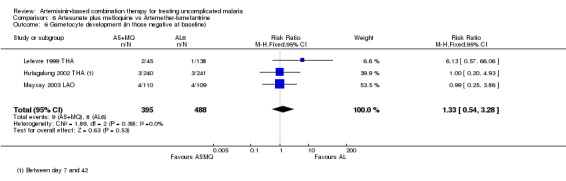

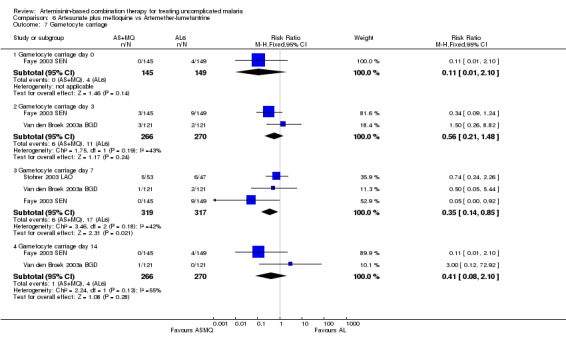

Gametocytes

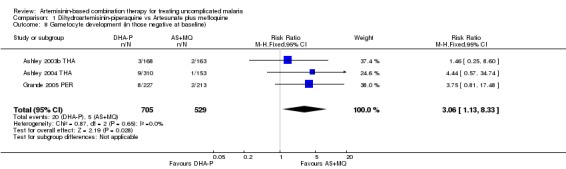

The number of participants who developed detectable gametocytes (after being negative at baseline) was low in both groups, but significantly lower with AS+MQ (three trials, 1234 participants: RR 3.06, 95% CI 1.13 to 8.33, Analysis 1.8). AS+MQ may also clear gametocytes quicker than DHA‐P but the analysis is confounded by differences in gametocyte carriage at baseline (two trials, 1174 participants, Analysis 1.9).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Dihydroartemisinin‐piperaquine vs Artesunate plus mefloquine, Outcome 8 Gametocyte development (in those negative at baseline).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Dihydroartemisinin‐piperaquine vs Artesunate plus mefloquine, Outcome 9 Gametocytaemia carriage.

Anaemia

Five trials report on haematological changes. Individual studies did not show significant differences between groups (see Appendix 5). Two trials (Ashley 2003b THA; Ashley 2004 THA) report a decrease in haematocrit over the first seven days followed by recovery in both groups (figures not reported).

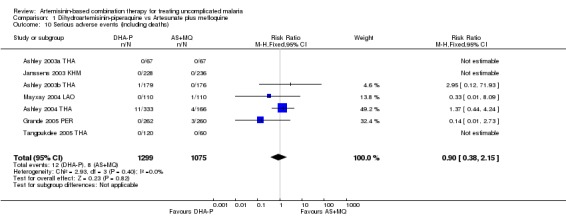

Adverse events

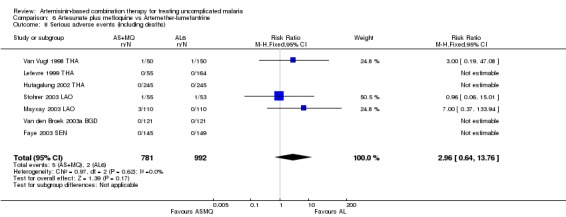

No difference has been shown in the frequency of serious adverse events (seven trials, 2374 participants, Analysis 1.10).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Dihydroartemisinin‐piperaquine vs Artesunate plus mefloquine, Outcome 10 Serious adverse events (including deaths).

There is some evidence that DHA‐P is better tolerated than AS+MQ. Cental nervous system (CNS) related adverse events (at least one of sleep disturbance, dizziness, or anxiety) were reported as more common with AS+MQ in five out of the nine trials. Five trials also report significantly more nausea and vomiting with AS+MQ and two trials report more palpitations and dyspnoea. Abdominal pain and diarrhoea were reported as significantly more common with DHA‐P in one trial each. For a summary of adverse event findings see Appendix 4.

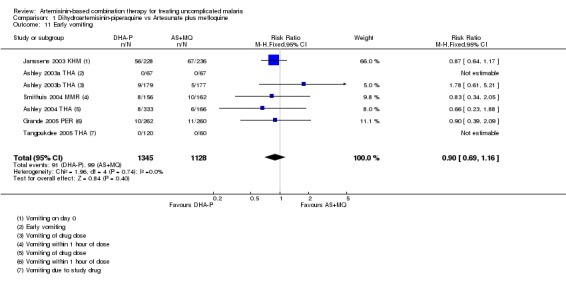

Early vomiting

Seven trials report some measure of early vomiting (vomiting related to drug administration) and no difference was shown in any trial (seven trials, 2473 participants, Analysis 1.11).

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Dihydroartemisinin‐piperaquine vs Artesunate plus mefloquine, Outcome 11 Early vomiting.

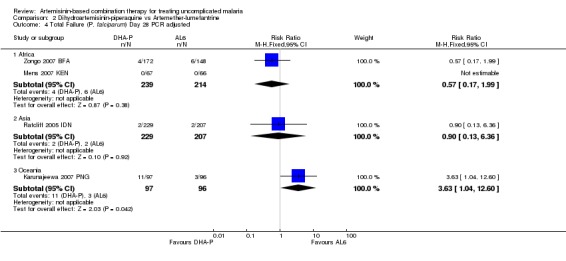

Comparison 2. DHA‐P versus artemether‐lumefantrine (six doses)

We found six trials (four in Africa, one in Asia and one in Oceania) which assessed this comparison. Allocation concealment was assessed as low risk of bias in four trials (Kamya 2006 UGA; Ratcliff 2005 IDN; Yeka 2007 UGA; Zongo 2007 BFA). Laboratory staff were blinded to treatment allocation in five out of six trials.

Total failure

PCR adjusted treatment failure with DHA‐P was below 5% in four out of six studies and with AL6 in two out of six studies. Of note, one trial from Africa (Kamya 2006 UGA) found PCR adjusted failure to be > 10% with both combinations.

In trials from Africa DHA‐P performed significantly better than AL6 at day 42 (three trials, 1136 participants: PCR unadjusted Heterogeneity: Chi² P < 0.0001, I² = 91%, Analysis 2.1; PCR adjusted RR 0.39, 95% CI 0.24 to 0.64, Analysis 2.2). Although there is substantial heterogeneity among PCR unadjusted results the direction of effect is consistently in favour of DHA‐P.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Dihydroartemisinin‐piperaquine vs Artemether‐lumefantrine, Outcome 1 Total Failure (P. falciparum) Day 42 PCR unadjusted.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Dihydroartemisinin‐piperaquine vs Artemether‐lumefantrine, Outcome 2 Total Failure (P. falciparum) Day 42 PCR adjusted.

In the one trial from Asia both drugs performed well with a non significant trend towards reduced re‐infections with DHA‐P (one trial, 356 participants, Analysis 2.1; Analysis 2.2; Analysis 2.3; Analysis 2.4).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Dihydroartemisinin‐piperaquine vs Artemether‐lumefantrine, Outcome 3 Total Failure (P. falciparum) Day 28 PCR unadjusted.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Dihydroartemisinin‐piperaquine vs Artemether‐lumefantrine, Outcome 4 Total Failure (P. falciparum) Day 28 PCR adjusted.

In Oceania Karunajeewa 2007 PNG showed a reduction in PCR adjusted treatment failure at day 28 with AL6 but this effect was no longer significant at day 42 (one trial, 356 participants, Analysis 2.1; Analysis 2.2; Analysis 2.3; Analysis 2.4).

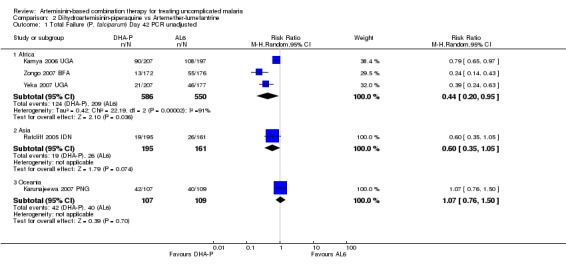

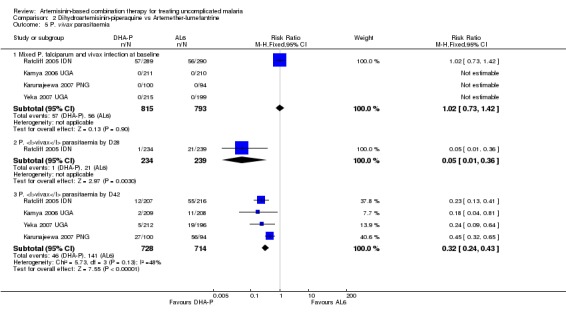

P. vivax

Participants treated with DHA‐P had significantly fewer episodes of P. vivax parasitaemia during 42 days follow up (four trials, 1442 participants: RR 0.32, 95% CI 0.24 to 0.43, Analysis 2.5). Of these four trials only one (Ratcliff 2005 IDN) included participants with P. vivax co‐infection at baseline.

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Dihydroartemisinin‐piperaquine vs Artemether‐lumefantrine, Outcome 5 P. vivax parasitaemia.

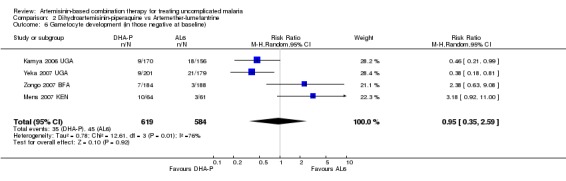

Gametocytes

Four trials reported the development of gametocytes in those negative at baseline and the results were highly heterogenous and could not be pooled (four trials, 1203 participants, heterogeneity: Chi² P = 0.006, I² = 76%, Analysis 2.6). This heterogeneity is consistent with the performance of the two drugs for total failure. In the two trials from Uganda (Kamya 2006 UGA and Yeka 2007 UGA) DHA‐P had significantly fewer treatment failures and was also significantly better at reducing gametocyte development. In trials with no difference for treatment failure (Zongo 2007 BFA and Mens 2007 KEN) there was also no difference in gametocyte development. Karunajeewa 2007 PNG and Ratcliff 2005 IDN report no differences in gametocyte carriage between groups but did not give figures.

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Dihydroartemisinin‐piperaquine vs Artemether‐lumefantrine, Outcome 6 Gametocyte development (in those negative at baseline).

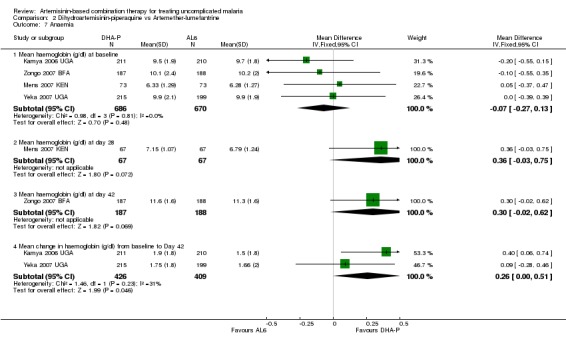

Anaemia

Four trials report changes in haemoglobin from baseline to the last day of follow up (day 28 or 42). There is a non significant trend towards a benefit with DHA‐P but this is unlikely to be of clinical significance (four trials, 1356 participants, Analysis 2.7). In addition Karunajeewa 2007 PNG reports that haemoglobin remained similar in all groups (no figures given).

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Dihydroartemisinin‐piperaquine vs Artemether‐lumefantrine, Outcome 7 Anaemia.

Adverse events

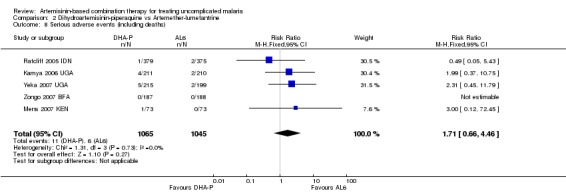

No significant difference has been shown in the frequency of serious adverse events (five trials, 2110 participants, Analysis 2.8).

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Dihydroartemisinin‐piperaquine vs Artemether‐lumefantrine, Outcome 8 Serious adverse events (including deaths).

Kamya 2006 UGA and Karunajeewa 2007 PNG report no differences between groups (two trials, 671 participants). Ratcliff 2005 IDN reports more diarrhoea (P = 0.003) with DHA‐P (774 participants). Mens 2007 KEN reports more weakness (P = 0.035) with AL6 (146 participants). Yeka 2007 UGA reports more abdominal pain (P = 0.05) with AL6 (414 participants). Zongo 2007 BFA reports more abdominal pain (P < 0.05) and headache (P < 0.05) with AL6 (375 participants). For a summary of adverse event findings see Appendix 4.

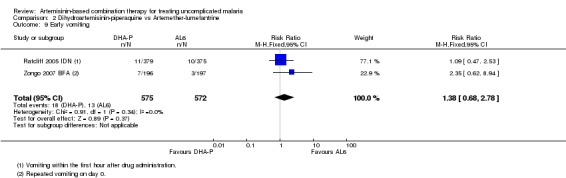

Early vomiting

No difference has been shown in the frequency of drug related vomiting (two trials,1147 participants, Analysis 2.9).

2.9. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Dihydroartemisinin‐piperaquine vs Artemether‐lumefantrine, Outcome 9 Early vomiting.

Comparison 3. DHA‐P versus artesunate plus amodiaquine

We found two trials (one in Africa and one in Asia) which assessed this comparison. Allocation concealment was assessed as low risk of bias in one trial (Hasugian 2005 IDN) and unclear in the other. In both trials laboratory staff were blinded to treatment allocation, but other staff and participants were unblinded.

Total failure

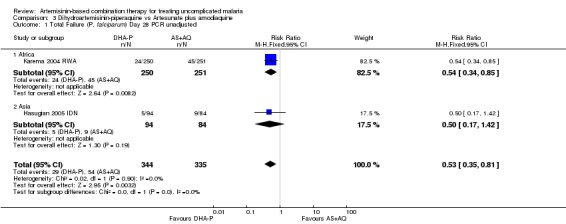

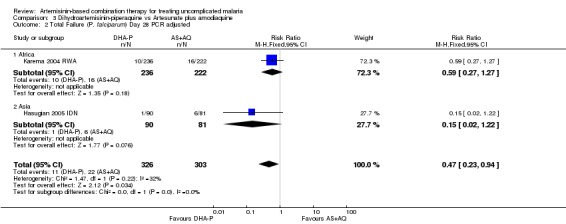

PCR adjusted treatment failure with DHA‐P was below 5% in both trials, and below 10% with AS+AQ.

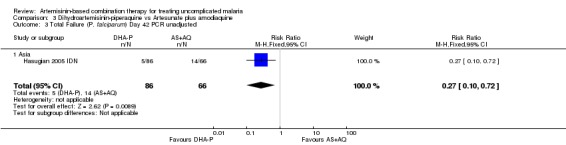

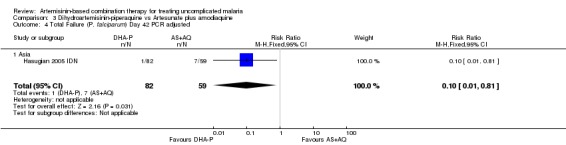

DHA‐P performed significantly better than AS+AQ at day 28 (two trials, 679 participants: PCR unadjusted RR 0.53, 95% CI 0.35 to 0.81, Analysis 3.1; PCR adjusted RR 0.47, 95% CI 0.23 to 0.94, Analysis 3.2). The one trial that reports outcomes at day 42 (Hasugian 2005 IDN) had high losses to follow up (> 20%) at this time point (Analysis 3.3; Analysis 3.4).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Dihydroartemisinin‐piperaquine vs Artesunate plus amodiaquine, Outcome 1 Total Failure (P. falciparum) Day 28 PCR unadjusted.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Dihydroartemisinin‐piperaquine vs Artesunate plus amodiaquine, Outcome 2 Total Failure (P. falciparum) Day 28 PCR adjusted.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Dihydroartemisinin‐piperaquine vs Artesunate plus amodiaquine, Outcome 3 Total Failure (P. falciparum) Day 42 PCR unadjusted.

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Dihydroartemisinin‐piperaquine vs Artesunate plus amodiaquine, Outcome 4 Total Failure (P. falciparum) Day 42 PCR adjusted.

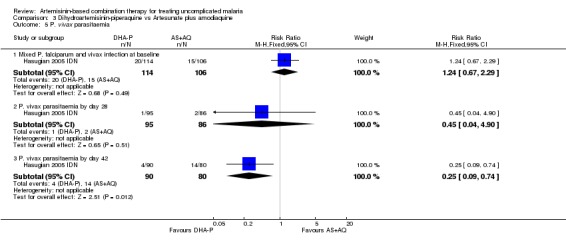

P. vivax

Hasugian 2005 IDN reports significantly fewer episodes of P. vivax parasitaemia with DHA‐P by day 42 (one trial, 170 participants: RR 0.25, 95% CI 0.09 to 0.74, Analysis 3.5).

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Dihydroartemisinin‐piperaquine vs Artesunate plus amodiaquine, Outcome 5 P. vivax parasitaemia.

Gametocytes

Both trials report no significant differences in gametocyte carriage during follow up (figures not reported).

Anaemia

Hasugian 2005 IDN found that the prevalence of anaemia at day seven (P = 0.02) and 28 (P = 0.006) was significantly higher with AS+AQ (authors own figures); in this trial recurrence of parasitaemia with both P. falciparum and P. vivax was higher in the AS+AQ group. Karema 2004 RWA found no significant difference in PCV between groups at days 0 or 14.

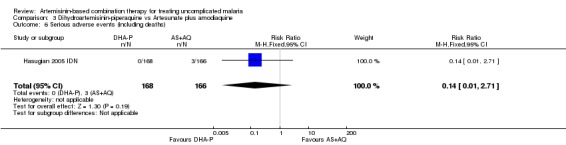

Adverse events

Hasugian 2005 IDN reports three serious adverse events with AS+AQ (two patients with recurrent vomiting on day three, one patient with bilateral cerebellar signs) (one trial, 334 participants, Analysis 3.6). Karema 2004 RWA does not comment on serious adverse events.

3.6. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Dihydroartemisinin‐piperaquine vs Artesunate plus amodiaquine, Outcome 6 Serious adverse events (including deaths).

Hasugian 2005 IDN reports more nausea (P = 0.004), vomiting (P = 0.02), and anorexia (P = 0.007) with AS+AQ (334 participants). Karema 2004 RWA reports more vomiting (P = 0.007), anorexia (P = 0.005) and fatigue (P = 0.001) with AS+AQ (504 participants). For a summary of adverse event findings see Appendix 4.

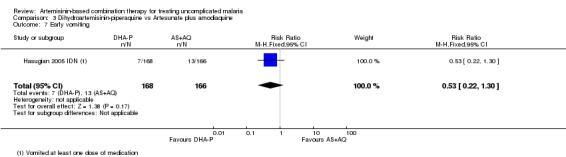

Early vomiting

Hasugian 2005 IDN found no significant difference in the number of participants who vomited at least one dose of medication (one trial, 334 participants, Analysis 3.7).

3.7. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Dihydroartemisinin‐piperaquine vs Artesunate plus amodiaquine, Outcome 7 Early vomiting.

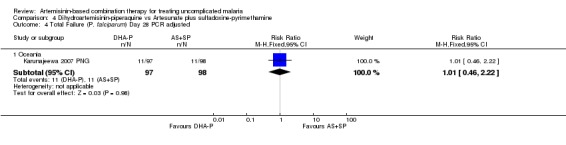

Comparison 4. DHA‐P versus artesunate plus sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine

We found one trial (from Oceania) which assessed this comparison. No attempt to conceal allocation was described. Laboratory staff were blinded to treatment allocation.

Total failure

At day 42 PCR adjusted treatment failure was > 10% in both groups.

There were no significant differences in treatment failure between the two arms (one trial, 215 participants, Analysis 4.1; Analysis 4.2; Analysis 4.3; Analysis 4.4)

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Dihydroartemisinin‐piperaquine vs Artesunate plus sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine, Outcome 1 Total Failure (P. falciparum) Day 42 PCR unadjusted.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Dihydroartemisinin‐piperaquine vs Artesunate plus sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine, Outcome 2 Total Failure (P. falciparum) Day 42 PCR adjusted.

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Dihydroartemisinin‐piperaquine vs Artesunate plus sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine, Outcome 3 Total Failure (P. falciparum) Day 28 PCR unadjusted.

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Dihydroartemisinin‐piperaquine vs Artesunate plus sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine, Outcome 4 Total Failure (P. falciparum) Day 28 PCR adjusted.

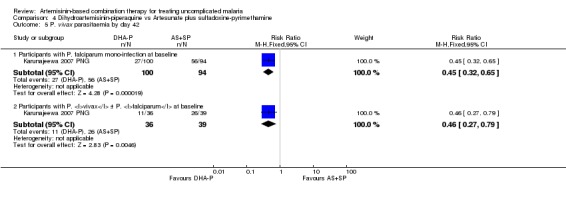

P. vivax

Compared to AS+SP, DHA‐P significantly reduced the incidence of P. vivax parasitaemia by day 42 in participants treated for P. falciparum mono‐infection at baseline (one trial, 194 participants: RR 0.45, 95% CI 0.32 to 0.65, Analysis 4.5), or P. vivax ± P. falciparum at baseline (one trial, 75 participants: RR 0.46, 95% CI 0.27 to 0.79, Analysis 4.5).

4.5. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Dihydroartemisinin‐piperaquine vs Artesunate plus sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine, Outcome 5 P. vivax parasitaemia by day 42.

Gametocytes

No significant differences in gametocyte carriage during follow up are reported (figures not reported).

Anaemia

Haemoglobin levels were reported to remain similar in both groups throughout follow up (figures not reported).

Adverse events

Monitoring for adverse events was undertaken but no differences between the groups were reported (see Appendix 4).

Early vomiting

Not reported.

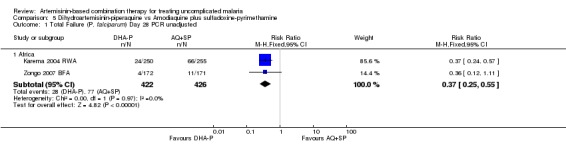

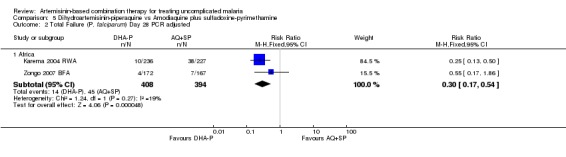

Comparison 5. DHA‐P versus amodiaquine plus sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine

We found two trials (both in Africa) which assessed this comparison. Allocation concealment was assessed as low risk of bias in one trial (Zongo 2007 BFA) and unclear in the other. Karema 2004 RWA blinded laboratory staff to treatment allocation. No other blinding is described.

Total failure

PCR adjusted treatment failure with DHA‐P was below 5% in both trials. In Rwanda, PCR adjusted treatment failure with AQ+SP was above 10%.

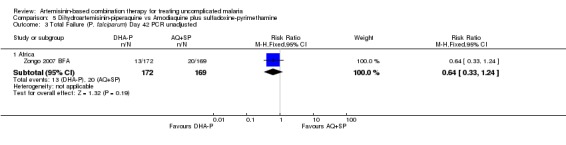

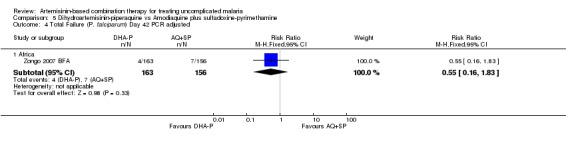

DHA‐P performed significantly better than AQ+SP at 28 days (two trials, 848 participants: PCR unadjusted RR 0.37, 95% CI 0.25 to 0.55, Analysis 5.1; PCR adjusted RR 0.30, 95% CI 0.17 to 0.54, Analysis 5.2). Zongo 2007 BFA did not show a difference at day 42 with both drugs performing well at this site (one trial, 341 participants, Analysis 5.3; Analysis 5.4).

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Dihydroartemisinin‐piperaquine vs Amodiaquine plus sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine, Outcome 1 Total Failure (P. falciparum) Day 28 PCR unadjusted.

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Dihydroartemisinin‐piperaquine vs Amodiaquine plus sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine, Outcome 2 Total Failure (P. falciparum) Day 28 PCR adjusted.

5.3. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Dihydroartemisinin‐piperaquine vs Amodiaquine plus sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine, Outcome 3 Total Failure (P. falciparum) Day 42 PCR unadjusted.

5.4. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Dihydroartemisinin‐piperaquine vs Amodiaquine plus sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine, Outcome 4 Total Failure (P. falciparum) Day 42 PCR adjusted.

P. vivax

Not reported.

Gametocytes

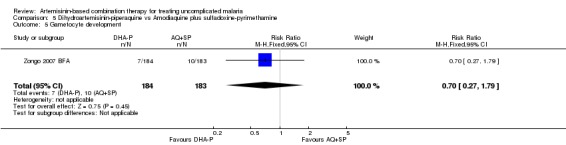

Zongo 2007 BFA found no difference in the development of gametocytaemia in participants who did not have detectable gametocytes at baseline (one trial, 367 participants, Analysis 5.5). Karema 2004 RWA reported no significant difference in gametocyte carriage during follow up but figures were not reported (one trial, 510 participants).

5.5. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Dihydroartemisinin‐piperaquine vs Amodiaquine plus sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine, Outcome 5 Gametocyte development.

Anaemia

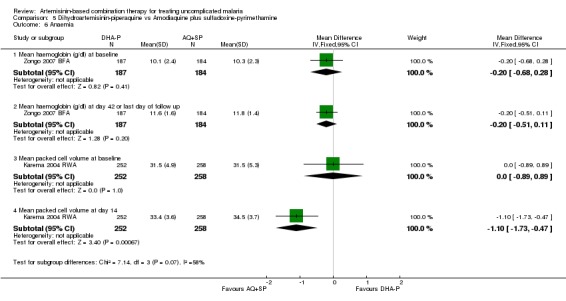

Zongo 2007 BFA found no significant difference in haemoglobin at baseline or at day 42 (1 trial, 371 participants, Analysis 5.6). Karema 2004 RWA found that the packed cell volume (PCV) increased from baseline to day 14 in both groups, but at day 14 it was significantly lower with DHA‐P (one trial, 510 participants: MD ‐1.10, 95% CI ‐1.73 to ‐0.47, Analysis 5.6). This difference is unlikely to be of clinical significance.

5.6. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Dihydroartemisinin‐piperaquine vs Amodiaquine plus sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine, Outcome 6 Anaemia.

Adverse events

Zongo 2007 BFA reports that there were no serious adverse events (one trial, 371 participants). Karema 2004 RWA does not comment on serious adverse events.

Zongo 2007 BFA reports more abdominal pain (P < 0.05) and pruritis (P < 0.05) with AQ+SP (371 participants). Karema 2004 RWA reports more vomiting (P = 0.007), anorexia (P = 0.005), and fatigue (P = 0.001) with AQ+SP (510 participants). For a summary of adverse event findings see Appendix 4.

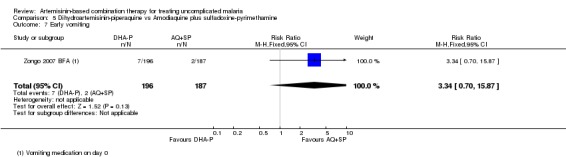

Early vomiting

Zongo 2007 BFA reports on vomiting medication on day 0 (as an exclusion criteria not an outcome) and there was no difference between groups (one trial, 383 participants, Analysis 5.7).

5.7. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Dihydroartemisinin‐piperaquine vs Amodiaquine plus sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine, Outcome 7 Early vomiting.

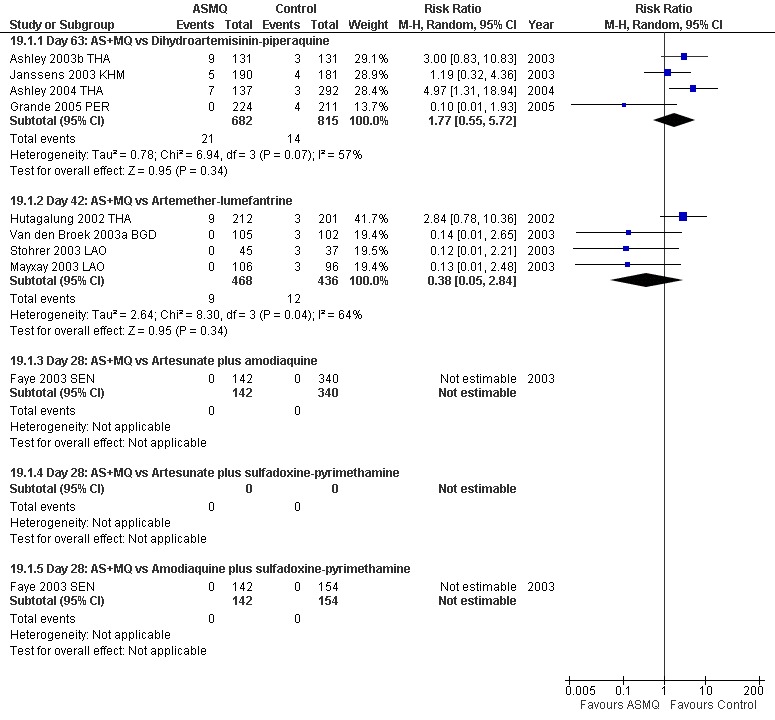

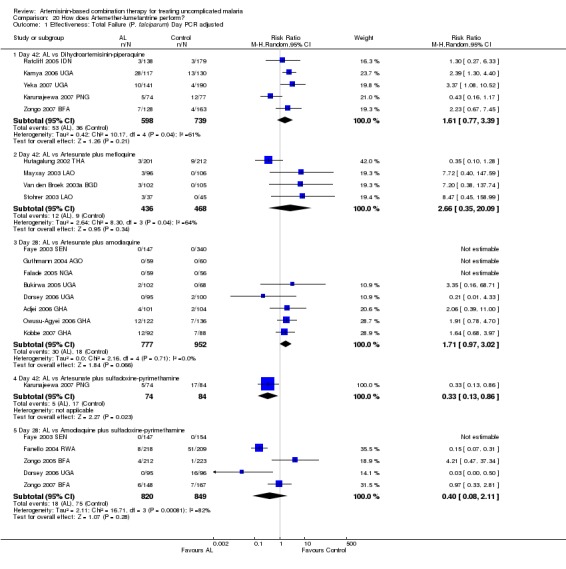

Question 2. How does artesunate mefloquine (AS+MQ) perform?

Dosing concerns

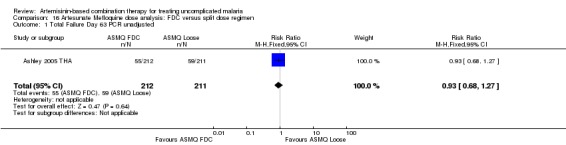

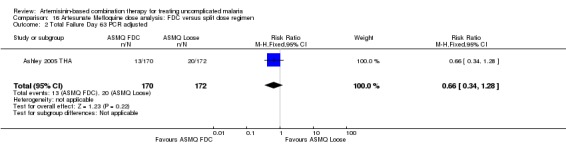

AS+MQ has traditionally been administered using 15 mg/kg mefloquine on day one and 10 mg/kg on day two. A new fixed‐dose combination of AS+MQ is now available where mefloquine is given as a once daily dose of 8 mg/kg. One trial (Ashley 2005 THA) has directly compared these two regimens and found no significant difference (one trial, 423 participants, Analysis 16.1; Analysis 16.2). In addition five trials used loose tablets to deliver a once daily dose of mefloquine of 8 mg/kg in combination with artesunate. In all of these trials the proportion of treatment failures with the new regimen was below 10% and in three trials below 5% (Analysis 17.1; Analysis 17.2)

16.1. Analysis.

Comparison 16 Artesunate Mefloquine dose analysis: FDC versus split dose regimen, Outcome 1 Total Failure Day 63 PCR unadjusted.

16.2. Analysis.

Comparison 16 Artesunate Mefloquine dose analysis: FDC versus split dose regimen, Outcome 2 Total Failure Day 63 PCR adjusted.

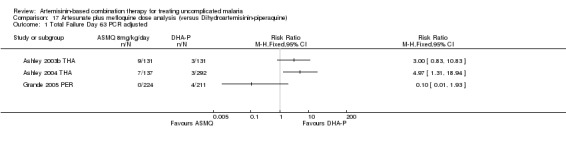

17.1. Analysis.

Comparison 17 Artesunate plus mefloquine dose analysis (versus Dihydroartemisinin‐piperaquine), Outcome 1 Total Failure Day 63 PCR adjusted.

17.2. Analysis.

Comparison 17 Artesunate plus mefloquine dose analysis (versus Dihydroartemisinin‐piperaquine), Outcome 2 Total Failure Day 28 PCR adjusted.

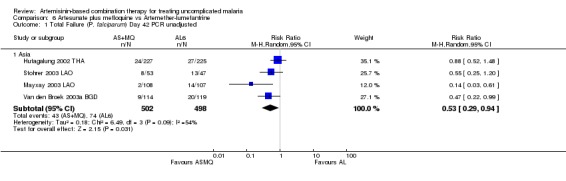

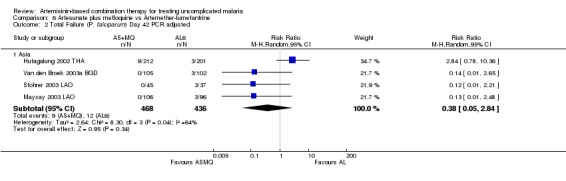

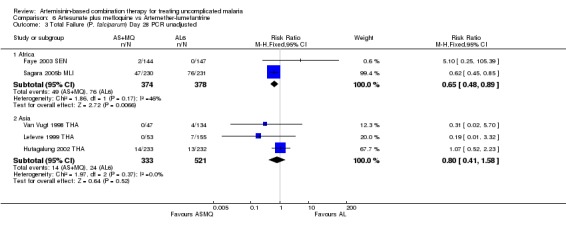

Comparison 6. AS+MQ versus artemether‐lumefantrine (six doses)

We found eight trials (six in Asia and two in Africa) which assessed this comparison. Allocation concealment was assessed as low risk of bias in two trials (Mayxay 2003 LAO; Sagara 2005b MLI). Only one trial blinded microscopists to treatment allocation.

Total failure

In all eight trials both combinations performed well with PCR adjusted treatment failures below 5%.

In Asia, AS+MQ reduced overall treatment failure by day 42 compared to AL6 (four trials, 1000 participants: PCR unadjusted RR 0.53, 95% CI 0.29 to 0.94, Analysis 6.1). For PCR adjusted treatment failure there was substantial heterogeneity (four trials, 904 participants: heterogeneity Chi² P = 0.04, I² = 64%, Analysis 6.2), which related to one trial (Hutagalung 2002 THA). This trial was unusual in that P. vivax was very common during follow up and significantly more common following treatment with AL6. P. vivax was treated with chloroquine and participants continued in follow up. Therefore significantly more participants in the AL6 group received additional antimalarials which may have affected the result. Sensitivity analysis removing this trial shifts the result significantly in favour of AS+MQ.

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Artesunate plus mefloquine vs Artemether‐lumefantrine, Outcome 1 Total Failure (P. falciparum) Day 42 PCR unadjusted.

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Artesunate plus mefloquine vs Artemether‐lumefantrine, Outcome 2 Total Failure (P. falciparum) Day 42 PCR adjusted.

There were no significant differences in PCR adjusted treatment failure at day 28 (five trials, 1479 participants, Analysis 6.4). One trial from Africa (Sagara 2005b MLI) did find a significant reduction in re‐infections with AS+MQ but this was not repeated elsewhere (Analysis 6.3).

6.4. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Artesunate plus mefloquine vs Artemether‐lumefantrine, Outcome 4 Total Failure (P. falciparum) Day 28 PCR adjusted.

6.3. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Artesunate plus mefloquine vs Artemether‐lumefantrine, Outcome 3 Total Failure (P. falciparum) Day 28 PCR unadjusted.

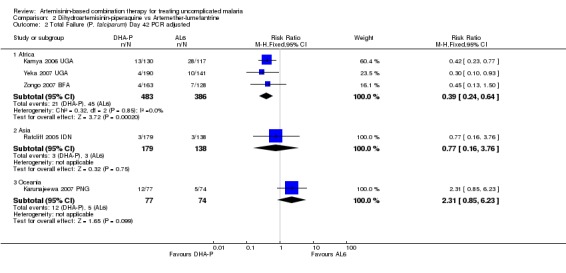

P. vivax

AS+MQ performed significantly better than AL6 at reducing the incidence of P. vivax during 42 days of follow up (four trials, 1003 participants: RR 0.30, 95% CI 0.21 to 0.41, Analysis 6.5).

6.5. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Artesunate plus mefloquine vs Artemether‐lumefantrine, Outcome 5 P. vivax parasitaemia.

Gametocytes

There is no evidence of an advantage with either drug at reducing gametocytaemia. There was no significant difference in gametocyte development in those negative at baseline (three trials, 883 participants, Analysis 6.6). Gametocyte carriage was generally low in the three trials which report it, with a statistically significant reduction in gametocyte carriage with AS+MQ on day seven, but not day three or 14 (three trials, 636 participants: Gametocyte carriage day seven RR 0.35, 95% CI 0.14 to 0.85, Analysis 6.7). Sagara 2005b MLI reports no differences between groups (no figures given).

6.6. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Artesunate plus mefloquine vs Artemether‐lumefantrine, Outcome 6 Gametocyte development (in those negative at baseline).

6.7. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Artesunate plus mefloquine vs Artemether‐lumefantrine, Outcome 7 Gametocyte carriage.

Anaemia

Six trials report some measure of haematological recovery. Hutagalung 2002 THA found a greater decrease in haematocrit at day seven with AS+MQ (9.3% AS+MQ versus 6.7% AL6, P = 0.02; authors own figures). None of the remaining five trials report a significant difference (see Appendix 5).

Adverse events

No difference has been shown in the frequency of serious adverse events (seven trials, 1773 participants, Analysis 6.8).

6.8. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Artesunate plus mefloquine vs Artemether‐lumefantrine, Outcome 8 Serious adverse events (including deaths).

Three trials report significantly more CNS symptoms with AS+MQ (dizziness, headache, confusion, or sleep disturbance) and one reports more with AL6. Gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms (nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, or anorexia) were significantly more common with AS+MQ in four trials. For a summary of adverse events see Appendix 4.

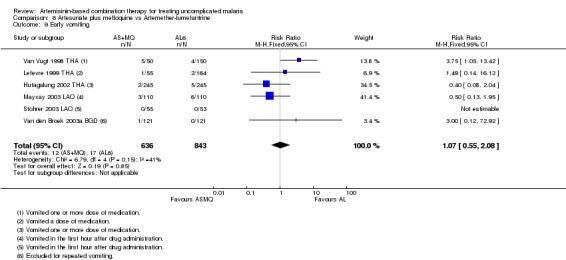

Early vomiting

No difference has been shown in the frequency of early vomiting (six trials, 1479 participants, Analysis 6.9).

6.9. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Artesunate plus mefloquine vs Artemether‐lumefantrine, Outcome 9 Early vomiting.

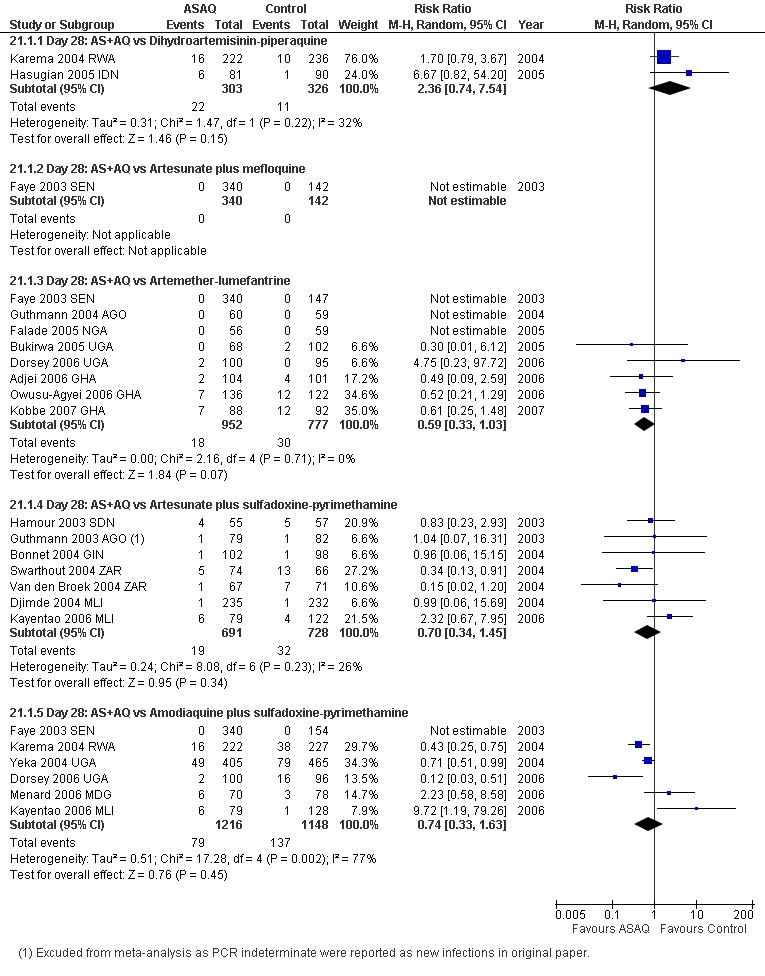

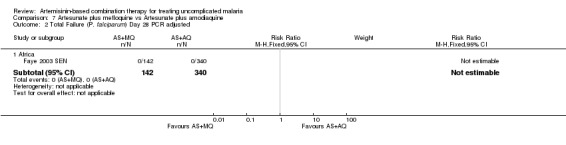

Comparison 7. AS+MQ versus artesunate plus amodiaquine

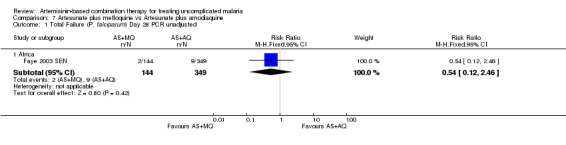

We only found one trial in Africa (Faye 2003 SEN) which assessed this comparison. Allocation concealment and blinding were not described.

Total failure

In the 28 days of this trial, treatment failure was very low in both groups. It is therefore not possible to draw conclusions on the benefits of either drug. There were no significant differences in PCR unadjusted failure (one trial, 493 participants, Analysis 7.1) and no episodes of PCR confirmed recrudescence.

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Artesunate plus mefloquine vs Artesunate plus amodiaquine, Outcome 1 Total Failure (P. falciparum) Day 28 PCR unadjusted.

P. vivax

Not reported.

Gametocytes

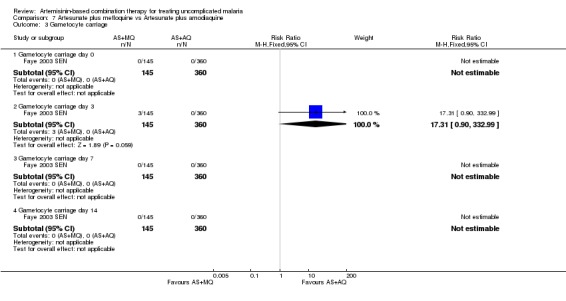

Gametocyte carriage was very low in both groups. Gametocytes were only detectable in three participants in the AS+MQ group on day three. At baseline, day seven and day 14 gametocytes were undetectable in all participants.

Anaemia

Twenty‐five percent of participants had haemoglobin measured on days 0 and 14 and no significant differences are reported.

Adverse events

In this trial there were no serious adverse events (one trial, 505 participants) and no differences between groups reported (see Appendix 4).

Early vomiting

Not reported.

Comparison n/a. AS+MQ versus artesunate plus sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine

We did not find any trials which assessed this comparison.

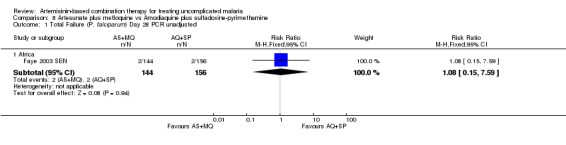

Comparison 8. AS+MQ versus amodiaquine plus sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine

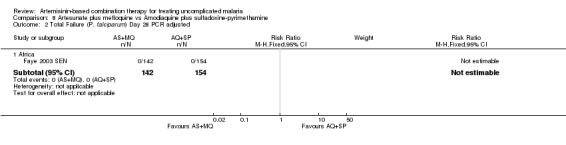

We only found one trial in Africa (Faye 2003 SEN) which assessed this comparison. Allocation concealment and blinding were not described.

Total failure

In the 28 days of this trial, treatment failure was very low in both groups. It is therefore not possible to draw conclusions on the benefits of either drug. There were no differences in PCR unadjusted failure (one trial, 300 participants, Analysis 8.1) and there were no episodes of PCR confirmed recrudescence.

8.1. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Artesunate plus mefloquine vs Amodiaquine plus sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine, Outcome 1 Total Failure (P. falciparum) Day 28 PCR unadjusted.

P. vivax

Not reported.

Gametocytes

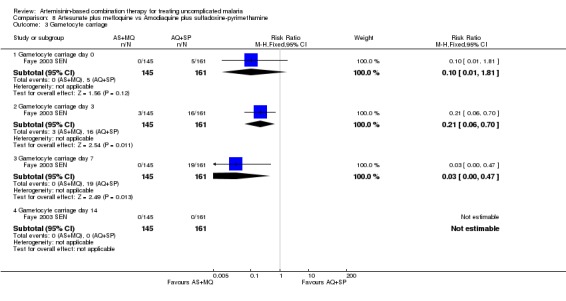

Detectable gametocytaemia was significantly less common with AS+MQ at days three and seven (Gametocyte carriage day three: RR 0.21, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.70; Gametocyte carriage day seven: RR 0.03, 95% CI 0.00 to 0.47, Analysis 8.3). At day 14 gametocytes were undetectable in all participants.

8.3. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Artesunate plus mefloquine vs Amodiaquine plus sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine, Outcome 3 Gametocyte carriage.

Anaemia

Twenty five percent of participants had haemoglobin measured on days 0 and 14 and no significant differences were reported.

Adverse events

In this trial there were no serious adverse events in either group (one trial, 306 participants) and no differences between groups reported (see Appendix 4).

Early vomiting

Not reported.

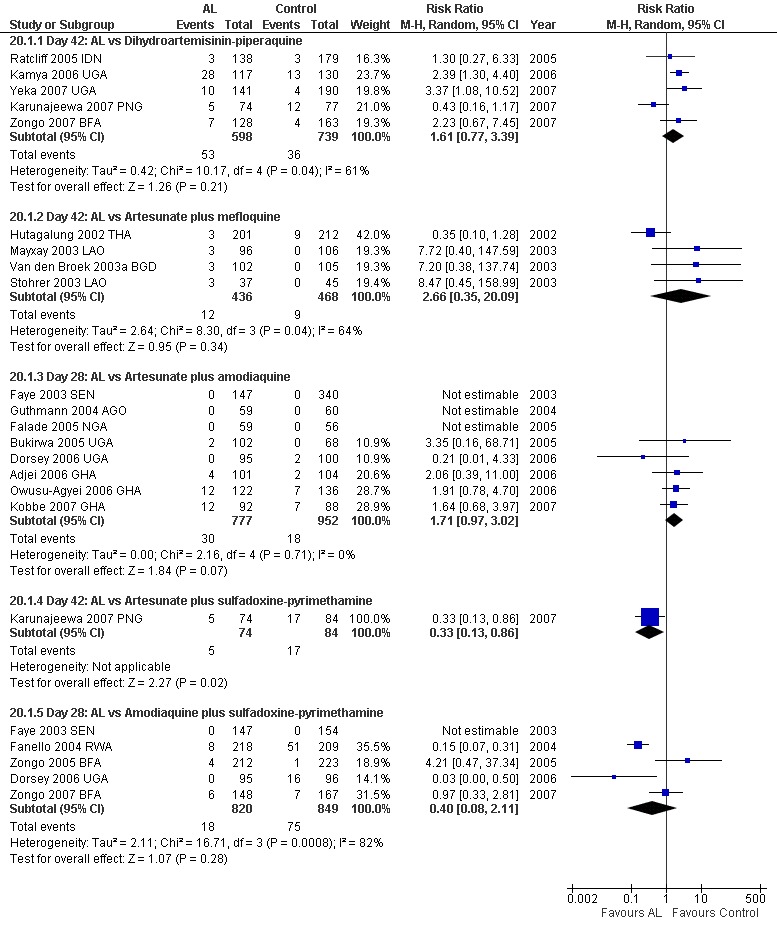

Question 3. How does artemether‐lumefantrine (6 doses) perform?

Dosing concerns

The six‐dose regimen of AL6 has been shown to be superior to the four‐dose regimen (Vugt 1999; Omari 2006). In this review we have only included the six‐dose regimen.

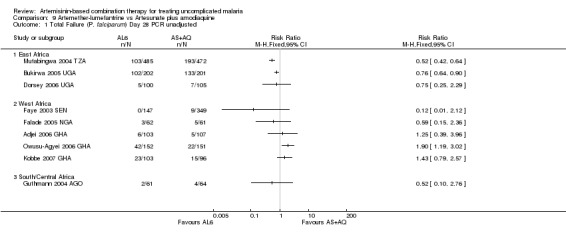

Comparison 9. AL6 versus artesunate plus amodiaquine

We found twelve trials (all in Africa) which assessed this comparison. Three of these trials were excluded after sensitivity analysis due to baseline differences which had the potential to bias the result in favour of AL6 (Analysis 9.9; Analysis 9.10). Of the remaining nine trials allocation concealment was assessed as low risk of bias in five trials (Adjei 2006 GHA; Bukirwa 2005 UGA; Dorsey 2006 UGA; Kobbe 2007 GHA; Mutabingwa 2004 TZA) and laboratory staff were blinded to treatment allocation in four trials.

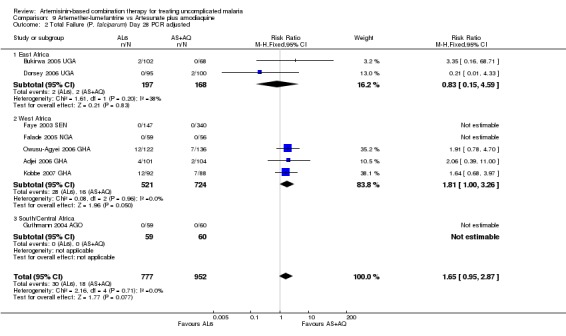

Total failure

PCR adjusted treatment failure was below 5% for both AL6 and AS+AQ in six out of eight trials. In two more recent trials (both from Ghana), PCR adjusted treatment failure for both arms was above 5% and for AL6 above 10% (Analysis 9.2).

9.2. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Artemether‐lumefantrine vs Artesunate plus amodiaquine, Outcome 2 Total Failure (P. falciparum) Day 28 PCR adjusted.

No difference has been shown in PCR adjusted total failure at day 28, either within individual trials or after pooling (eight trials, 1729 participants, Analysis 9.2). There is substantial heterogeneity in PCR unadjusted failure (nine trials, 3021 participants: heterogeneity Chi² P < 0.0001, I² = 76%, Analysis 9.1). Subgroup analysis seems to suggest regional differences, with studies from East Africa showing benefit with AL6 and recent studies from West Africa favouring AS+AQ (Analysis 9.1). However, substantial heterogeneity remains, and further subgroup analysis by trial characteristics and transmission intensity did not expand the interpretation of this heterogeneity.

9.1. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Artemether‐lumefantrine vs Artesunate plus amodiaquine, Outcome 1 Total Failure (P. falciparum) Day 28 PCR unadjusted.

P. vivax

One trial (Dorsey 2006 UGA) reported on P. vivax but there were too few patients to draw a conclusion (AL6: 8/202 at baseline and 3/202 during follow up, AS+AQ: No vivax at any time point).

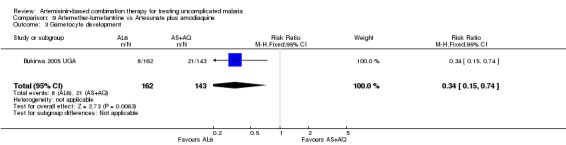

Gametocytes

Bukirwa 2006 found that AL6 significantly reduced the development of gametocytaemia in patients who did not have detectable gametocytes at baseline (one trial, 305 participants: RR 0.34, 95% CI 0.15 to 0.74, Analysis 9.3). Three trials reporting gametocyte carriage over 14 days of follow up do not show a clear advantage with either combination (three trials, 1078 participants, Analysis 9.4).

9.3. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Artemether‐lumefantrine vs Artesunate plus amodiaquine, Outcome 3 Gametocyte development.

9.4. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Artemether‐lumefantrine vs Artesunate plus amodiaquine, Outcome 4 Gametocyte carriage.

Anaemia

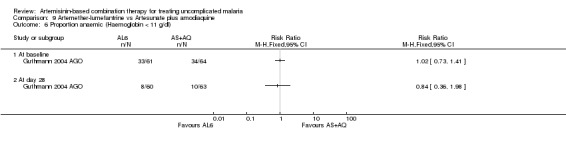

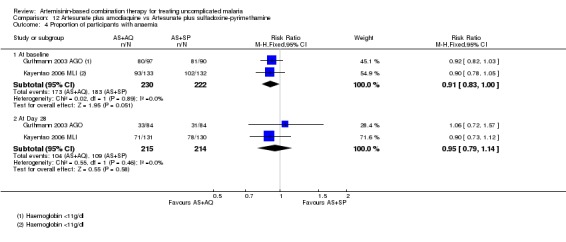

Four studies reported some measure of haematological recovery from baseline to day 28 and did not show a difference between the two combinations (four trials, 2356 participants, Analysis 9.5). Guthmann 2004 AGO reported the proportion of participants who were anaemic (Hb < 11 g/dl) at day 0 and 28 and did not show a difference (one trial, 123 participants, Analysis 9.6). Three trials (Dorsey 2006 UGA; Faye 2003 SEN; Mutabingwa 2004 TZA) also reported measures of anaemia at day 14 and did not show a difference.

9.5. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Artemether‐lumefantrine vs Artesunate plus amodiaquine, Outcome 5 Anaemia.

9.6. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Artemether‐lumefantrine vs Artesunate plus amodiaquine, Outcome 6 Proportion anaemic (Haemoglobin < 11 g/dl).

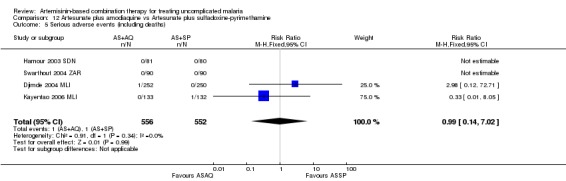

Adverse events

No difference has been shown in the frequency of serious adverse events (six trials, 2749 participants, Analysis 9.7).

9.7. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Artemether‐lumefantrine vs Artesunate plus amodiaquine, Outcome 7 Serious adverse events (including deaths).

No important differences in adverse events were reported between groups. For a summary of adverse events see Appendix 4.

Early vomiting

No difference has been shown in the frequency of early vomiting (five trials, 1097 participants, Analysis 9.8).

9.8. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Artemether‐lumefantrine vs Artesunate plus amodiaquine, Outcome 8 Early vomiting.

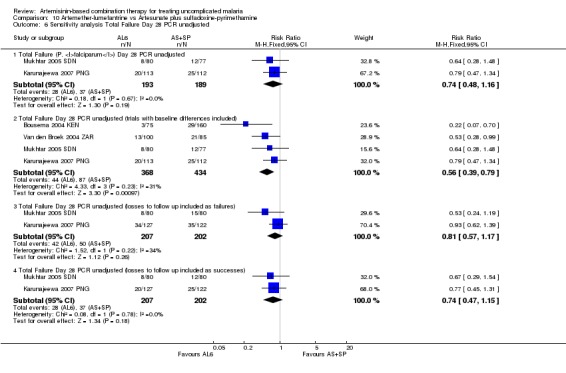

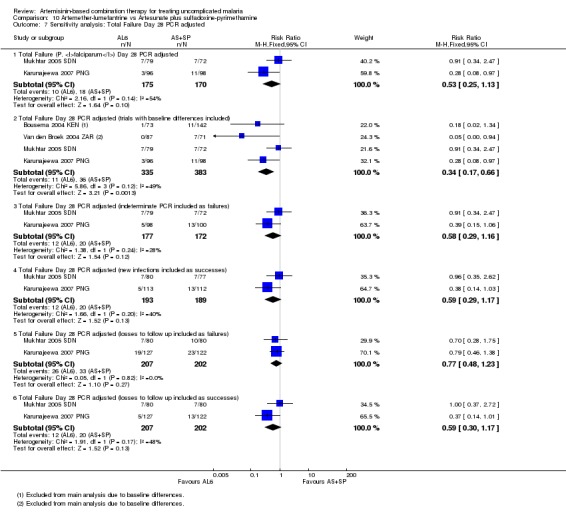

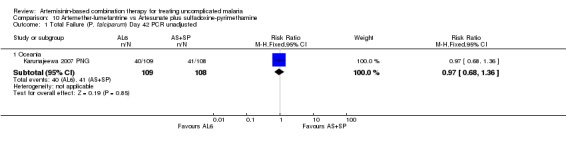

Comparison 10. AL6 versus artesunate plus sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine

We found four trials (three from Africa and one from Oceania) which assessed this comparison. Two of these trials were excluded from the primary analysis due to baseline differences between the groups (Analysis 10.6; Analysis 10.7). Allocation concealment was judged to be at high risk of bias in the two remaining trials. Laboratory staff were blinded to treatment allocation in one trial.

10.6. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Artemether‐lumefantrine vs Artesunate plus sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine, Outcome 6 Sensitivity analysis Total Failure Day 28 PCR unadjusted.

10.7. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Artemether‐lumefantrine vs Artesunate plus sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine, Outcome 7 Sensitivity analysis: Total Failure Day 28 PCR adjusted.

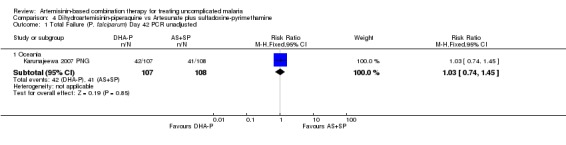

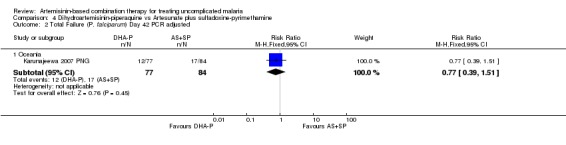

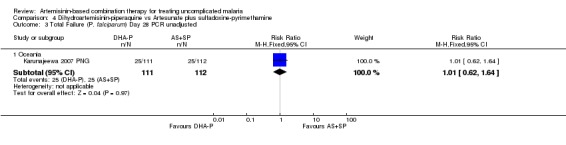

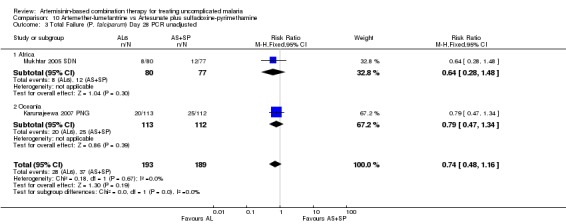

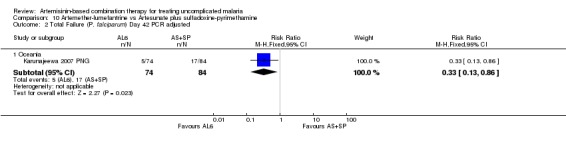

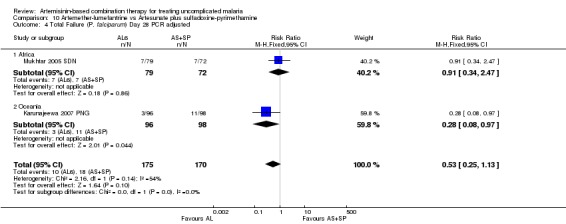

Total failure

In Oceania, Karunajeewa 2007 PNG found no difference in PCR unadjusted failure (one trial, 217 participants, Analysis 10.1; Analysis 10.3), but did show a significant reduction in PCR adjusted treatment failure with AL6 at both day 28 and day 42 (one trial, 217 participants: Day 42 RR 0.33, 95% CI 0.13 to 0.86, Analysis 10.2; Day 28 RR 0.28, 95% CI 0.08 to 0.97, Analysis 10.4). PCR adjusted treatment failure with AS+SP was > 20% at day 42.

10.1. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Artemether‐lumefantrine vs Artesunate plus sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine, Outcome 1 Total Failure (P. falciparum) Day 42 PCR unadjusted.

10.3. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Artemether‐lumefantrine vs Artesunate plus sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine, Outcome 3 Total Failure (P. falciparum) Day 28 PCR unadjusted.

10.2. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Artemether‐lumefantrine vs Artesunate plus sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine, Outcome 2 Total Failure (P. falciparum) Day 42 PCR adjusted.

10.4. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Artemether‐lumefantrine vs Artesunate plus sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine, Outcome 4 Total Failure (P. falciparum) Day 28 PCR adjusted.

In Africa, Mukhtar 2005 SDN found no difference between the two groups (one trial, 157 participants, Analysis 10.3, Analysis 10.4).

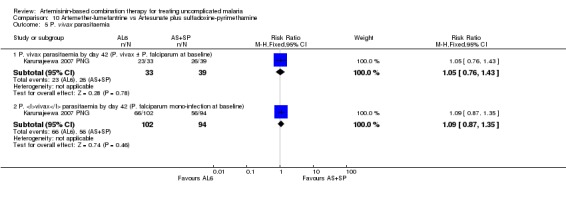

P. vivax

Karunajeewa 2007 PNG found no differences in the incidence of P. vivax parasitaemia by day 42 in participants treated for P. falciparum mono‐infection at baseline (one trial, 196 participants), or those treated for P. vivax at baseline (one trial, 72 participants, Analysis 10.5)

10.5. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Artemether‐lumefantrine vs Artesunate plus sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine, Outcome 5 P. vivax parasitaemia.

Gametocytes

Karunajeewa 2007 PNG reports no differences in gametocyte carriage between the two groups during follow up (figures not reported).

Anaemia

Karunajeewa 2007 PNG reports no differences in mean haemoglobin during follow up (figures not reported).

Adverse events

Two trials report on adverse events and no differences are noted between the two groups (Karunajeewa 2007 PNG; Van den Broek 2004 ZAR). For a summary of adverse events see Appendix 4.

Early vomiting

Not reported.

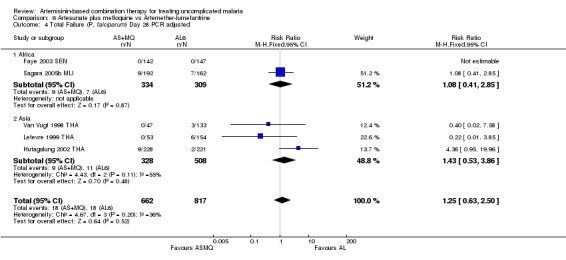

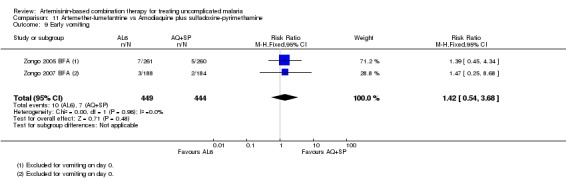

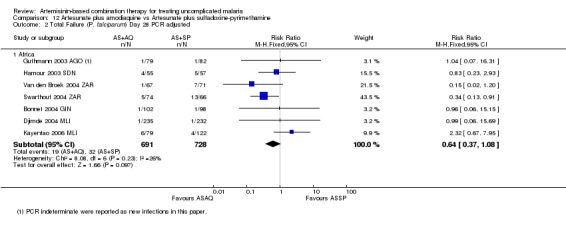

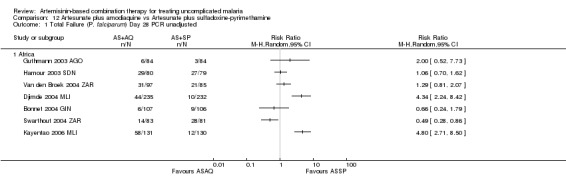

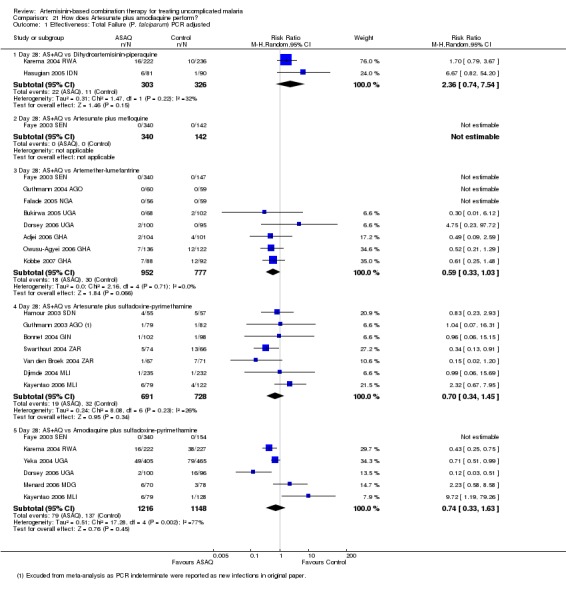

Comparison 11. AL6 versus amodiaquine plus sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine

We found seven trials (all in Africa) which assessed this comparison. One trial was excluded from the primary analysis due to baseline differences between groups. Of the remaining trials allocation concealment was assessed as low risk of bias in two trials (Dorsey 2006 UGA; Zongo 2007 BFA) and laboratory staff were blinded to treatment allocation in four trials.

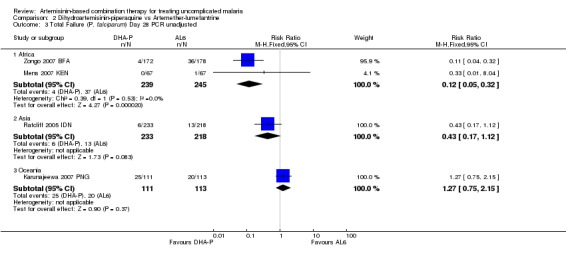

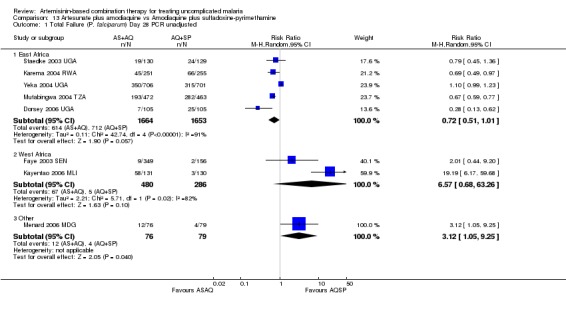

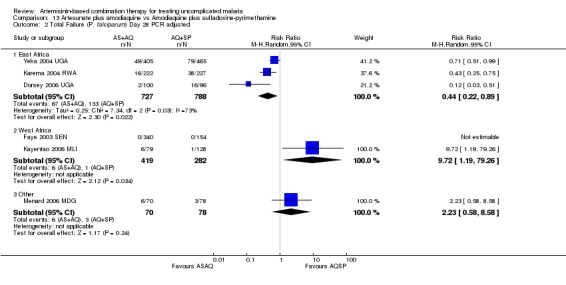

Total failure

PCR adjusted treatment failure with AL6 was below 5% in all six trials. The performance of AQ+SP was much more variable.

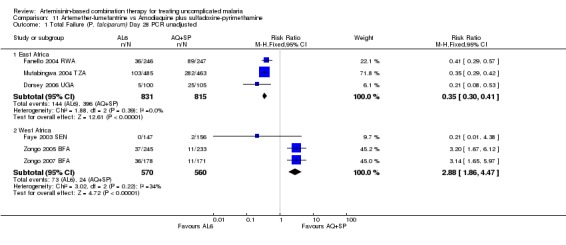

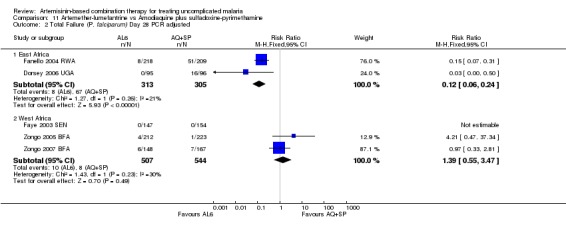

In East Africa, where treatment failure with AQ+SP was high, AL6 performed markedly better at day 28 (three trials, 1646 participants: PCR unadjusted RR 0.35, 95% CI 0.30 to 0.41, Analysis 11.1; PCR adjusted RR 0.12, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.24, Analysis 11.2).

11.1. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Artemether‐lumefantrine vs Amodiaquine plus sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine, Outcome 1 Total Failure (P. falciparum) Day 28 PCR unadjusted.

11.2. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Artemether‐lumefantrine vs Amodiaquine plus sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine, Outcome 2 Total Failure (P. falciparum) Day 28 PCR adjusted.

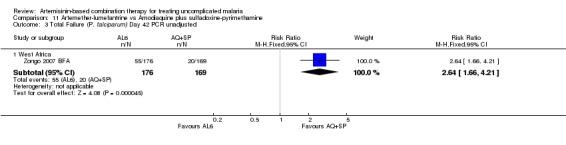

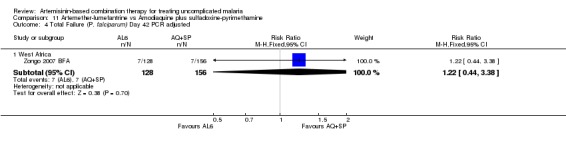

In contrast, in West Africa, where AQ+SP performed much better, there were fewer PCR unadjusted treatment failures with AQ+SP at both day 28 (three trials, 1130 participants: PCR unadjusted RR 2.88, 95% CI 1.86 to 4.47, Analysis 11.1) and day 42 (one trial, 345 participants: PCR unadjusted RR 2.64, 95% CI 1.66 to 4.21, Analysis 11.3). There were no significant differences between the two combinations after PCR adjustment (Analysis 11.2; Analysis 11.4).

11.3. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Artemether‐lumefantrine vs Amodiaquine plus sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine, Outcome 3 Total Failure (P. falciparum) Day 42 PCR unadjusted.

11.4. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Artemether‐lumefantrine vs Amodiaquine plus sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine, Outcome 4 Total Failure (P. falciparum) Day 42 PCR adjusted.

P. vivax

Only one trial (Dorsey 2006 UGA) reported on P. vivax and there were too few patients to draw a conclusion (AL6 8/202 at baseline and 3/202 during follow up, AQ+SP 4/253 at baseline and 0 during follow up).

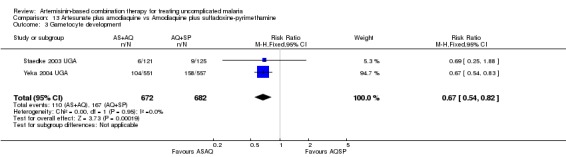

Gametocytes

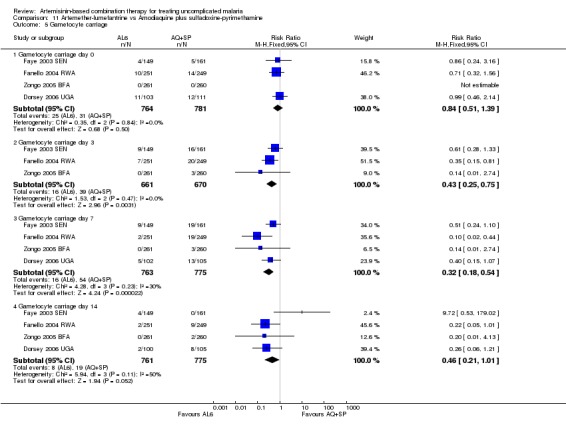

The prevalence of gametocyte carriage was significantly lower with AL6 at day three (three trials, 1331 participants: RR 0.43, 95% CI 0.25 to 0.75, Analysis 11.5) and day seven (four trials,1538 participants: RR 0.32, 95% CI 0.18 to 0.54, Analysis 11.5). Zongo 2007 BFA found no significant difference in the development of gametocytaemia in participants without detectable gametocytes at baseline (one trial, 371 participants, Analysis 11.6).

11.5. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Artemether‐lumefantrine vs Amodiaquine plus sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine, Outcome 5 Gametocyte carriage.

11.6. Analysis.

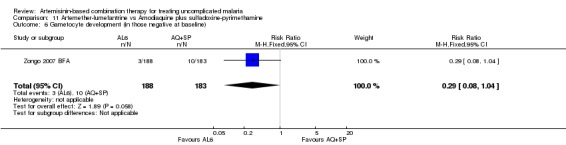

Comparison 11 Artemether‐lumefantrine vs Amodiaquine plus sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine, Outcome 6 Gametocyte development (in those negative at baseline).

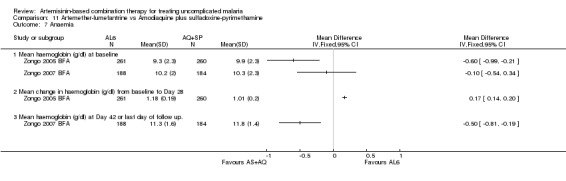

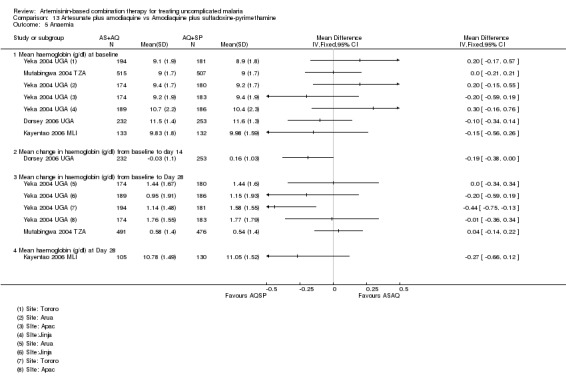

Anaemia

Zongo 2005 BFA reports change in haemoglobin from baseline to day 28; Zongo 2007 BFA reports mean haemoglobin at baseline and day 42. Neither of these trials showed a clinically significant difference (two trials, 893 participants, Analysis 11.7). Four other trials assessed haematological recovery at shorter time points and did not detect a difference (Dorsey 2006 UGA; Fanello 2004 RWA; Faye 2003 SEN; Mutabingwa 2004 TZA).

11.7. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Artemether‐lumefantrine vs Amodiaquine plus sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine, Outcome 7 Anaemia.

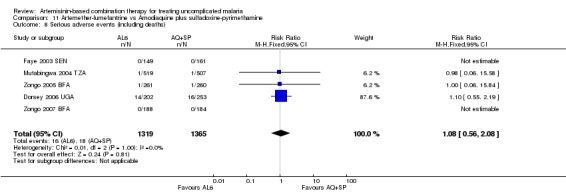

Adverse events