Abstract

Background

Neurocysticercosis is an infection of the brain by the larval stage of the pork tapeworm. In endemic areas it is a common cause of epilepsy. Anthelmintics (albendazole or praziquantel) may be given to kill the parasites. However, there are potential adverse effects, and the parasites may eventually die without treatment.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness and safety of anthelmintics for people with neurocysticercosis.

Search methods

In May 2009 we searched the Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group Specialized Register, CENTRAL (The Cochrane Library 2009, Issue 2), MEDLINE, EMBASE, LILACS, and the mRCT.

Selection criteria

Randomized controlled trials comparing anthelmintics with placebo, no anthelmintic, or other anthelmintic regimen for people with neurocysticercosis.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently selected trials, extracted data, and assessed each trial's risk of bias. We calculated risk ratios (RR) for dichotomous variables, with 95% confidence intervals (CI). We pooled data from trials with similar interventions and outcomes.

Main results

For viable lesions in children, there were no trials. For viable lesions in adults, no difference was detected for albendazole compared with no treatment for recurrence of seizures (116 participants, one trial); but fewer participants with albendazole had lesions at follow up (RR 0.56, 95% CI 0.45 to 0.70; 192 participants, two trials).

For non‐viable lesions in children, seizures recurrence was less common with albendazole compared with no treatment (RR 0.49, 95% CI 0.32 to 0.75; 329 participants, four trials). There was no difference detected in the persistence of lesions at follow up (570 participants, six trials). For non‐viable lesions in adults, there were no trials.

In trials including viable, non‐viable or mixed lesions (in both children and adults), headaches were more common with albendazole alone (RR 9.49, 95% CI 1.40 to 64.45; 106 participants, two trials), but no difference was detected in one trial giving albendazole with corticosteroids (116 participants, one trial).

Authors' conclusions

In patients with viable lesions, evidence from trials of adults suggests albendazole may reduce the number of lesions. In trials of non‐viable lesions, seizure recurrence was substantially lower with albendazole, which is counter‐intuitive. It may be that steroids influence headache during treatment, but further research is needed to test this.

22 March 2019

Update pending

Authors currently updating

The update is due to be published in 2019.

Plain language summary

Treatment for illness caused by tapeworm larvae in the brain

If people eat eggs from the pork tapeworm (Taenia solium), these eggs can move from the gut and then lodge in different tissues of the body forming cysts. When these cysts form in the brain, this is called neurocysticercosis. Some people may have no symptoms if this happens, but others may suffer from seizures, headaches, or more rarely from confusion, loss of balance or brain swelling. More rarely still, someone may die.

The condition is mainly found where people live in close contact with pigs and where the sanitation is poor. It affects around 50 million people worldwide, and in some areas is the leading cause of adult‐onset epilepsy.

The number, size and location of the cysts help to guide treatment of neurocysticercosis, as do the patient’s symptoms; for example, giving anticonvulsants to someone with seizures. Two drugs, praziquantel and albendazole, can be used specifically in neurocysticercosis to help kill the parasite; these drugs are known as anthelmintics. Some cysts, called non‐viable lesions are generally in the process of degenerating and resolving spontaneously; many experts recommend not treating this type of cyst. However, treating viable lesions (ie those lesions that may or may not resolve spontaneously) with these drugs may help kill the parasite, although treatment remains controversial due to the potential side effects and the fact the parasite may die without treatment.

In this review of 21 relevant randomized controlled trials, most studies examined the effects of albendazole. In patients with viable lesions, there is only evidence available for adult patients; this suggests that albendazole may reduce the number of lesions. In patients with non‐viable lesions, there is only evidence available for children; this suggests that seizure recurrence was lower with albendazole, which goes against the opinions of some experts. There is insufficient evidence available to assess praziquantel.

Background

Neurocysticercosis is an infection of the central nervous system by the larval stage of the pork tapewormTaenia solium. If eggs (cysticerci) from the faeces of humans infected with the intestinal parasites are ingested, they can migrate from the gut to lodge in various tissues of the body, where they form cysts (cysticercosis). This review is confined to treating neurocysticercosis, where the cysts lodge in the brain.

The cysts naturally evolve, over a period of years, through stages beginning with viable larvae and ending with the death of the parasite and resorption or calcification of the cyst. Individuals may have one or more cysticerci in the brain. The following types of neurocysticercosis have been recognized, depending on where the cysts are lodged: parenchymal; intraventricular; racemose type found in the basal cisterns; and spinal. Symptoms may or may not occur, depending on the number, location, and stage of the cysts, as well as the infected person's immune response. Seizures are the most common symptom, present in most of the presenting cases, followed by headaches. Rarely, it causes confusion, lack of attention to people and surroundings, difficulty with balance, paralysis, swelling of the brain, and very rarely, death. Symptoms may be associated with the host's immune response or due to calcifications left once the cysts have been eliminated (Leite 2000).

The condition is found where people live in close contact with pigs and where sanitation is poor. It is common in much of South and Central America, China, the Indian subcontinent and South‐East Asia, and sub‐Saharan Africa. It affects around 50 million people worldwide (Kossoff 2005), with men and women equally affected, and has a peak of incidence at the ages of 30 to 40 years (Burneo 2005). In endemic areas, it is the leading cause of adult‐onset epilepsy and an important cause of seizures in children (Roman 2000). It has also been estimated to cause at least 50,000 deaths worldwide each year (Roman 2000). It is therefore a significant public health problem, with significant associated costs in health care and lost productivity.

The cysts in the brain can be visualized using CT or MRI scanning. Over the course of the infection, radiological images change from 'non‐enhancing' (after intravenous injection of a radiographic contrast), indicating a viable cyst with little host immune response, to 'ring‐enhancing' indicating a degenerating cyst with surrounding immune response, to calcification or total resolution (DeGiorgio 2004). Cysts may be located in the parenchyma (brain tissue) or within structures and spaces around the brain (extraparenchymal cysts). Infection burden varies widely; a recently published guideline classified infection burdens from mild (one to five cysts) to moderate (five to 99 cysts) to heavy (more than 100 cysts) (Garcia 2002).

Treatment options depend on the number, size, and location of the cysts, and on the symptoms. Initial symptomatic treatment includes anticonvulsant drugs for seizures and analgesics for headache. Some extraparenchymal cysts are treated with surgery, either to remove the cyst or to relieve intracranial pressure. Where serious inflammation of the brain is present (usually associated with degeneration of the cysts), corticosteroids may be prescribed.

Cysts may degenerate and resolve spontaneously. For this reason, specific anthelmintics are usually considered for people with viable cysts, as the treatment may help kill the parasites. When lesions are non‐viable, many experts do not recommend these drugs.

There are two anthelmintics used in neurocysticercosis: praziquantel, available since 1979, and albendazole, available since 1987. If anthelmintics are used, corticosteroids are often prescribed with them to prevent inflammation of the brain caused by the host immune response to the destroyed parasites.

Treatment with anthelmintics remains controversial, due to potential adverse events and the natural history of the parasite, which may eventually die without treatment. The original version of this Cochrane Review found no evidence that the potential benefits of treatment outweigh the potential harms (Salinas 1999). This review was undertaken as a substantive update of the original Cochrane Review to take trials published since 1999 into account. We have stratified patients by age (children and adult) and by whether patients have predominantly viable or non‐viable cysts, given the natural history and assumptions about when anthelmintics may or may not be effective.

Objectives

To assess the effects of anthelmintics for people with neurocysticercosis.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomized controlled trials.

Types of participants

People with symptomatic or asymptomatic neurocysticercosis defined by viable or non‐viable lesions in the brain, identified as 'non‐enhancing' or 'ring‐enhancing' on medical imaging..

Types of interventions

Intervention

Anthelmintics plus usual treatment.

Anthelmintics plus corticosteroids plus usual treatment.

Control

Usual treatment only.

Corticosteroids plus usual treatment.

Another anthelmintic plus usual treatment.

Another dose or duration of anthelmintic, plus usual treatment.

We included trials irrespective of the type of anthelmintic used, or the dosage and duration of treatment.

Types of outcome measures

Primary

Free of seizures for one year after treatment.

Recurrence of seizures at follow‐up.

Number of seizures during follow‐up period.

Seizure free at follow‐up following withdrawal of anticonvulsant drugs.

Secondary

Health status indicators

All‐cause death.

Hospital admission for any cause.

Any neurological symptoms or signs (includes headache, paralysis, visual disturbance).

Need for surgery.

Resumption of normal activities at follow up; or time to resumption of normal activities.

Resolution of symptoms.

Radiological changes at follow up

Persistence of lesions.

Reduction in number of lesions.

Reduction in ventricular size.

Adverse events

Any adverse events.

Adverse event requiring withdrawal of anthelmintic drugs.

Search methods for identification of studies

We attempted to identify all relevant trials regardless of language or publication status (published or unpublished, in press, or in progress).

Databases

We searched the following databases using the search terms and strategy described in Appendix 1: the Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group Specialized Register (May 2009); the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), published in The Cochrane Library (2009, Issue 2); MEDLINE (1966 to May 2009); EMBASE (1988 to May 2009); and LILACS (1982 to May 2009). We also searched the metaRegister of Controlled Trials (mRCT) using the term 'neurocysticercosis' May 2009).

Reference lists

We also checked the reference lists of all trials and review articles identified by the above method.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two authors (KA and LR) independently screened all citations and abstracts, using an eligibility form to apply the selection criteria to identify relevant studies. Where there was uncertainty over the eligibility of a particular study, we obtained the full‐text article. We resolved any differences in opinion by discussion or, where necessary, by discussion with the third author (SR). We excluded studies that did not meet the criteria, and documented the reasons for exclusion in the table 'Characteristics of excluded studies'.

Data extraction and management

One author (KA) extracted data using a tailored data extraction form, and a second author (LR) checked this extracted data, after which any disagreements were resolved by discussion. We summarized data on study design, participant characteristics, interventions, and outcomes and entered these into Review Manager 5.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed the risk of bias of the included trials using a pro forma. In case of disagreement, we planned to consult a third person. We categorized the generation of the allocation sequence and allocation concealment as adequate, unclear, or inadequate as in Jüni 2001. We assessed whether the participants, care providers and investigators were blinded to which participants received which drug regimen. For all outcomes, we assessed that incomplete outcome data had been adequately addressed if 85% or more of the participants were included in the analysis, or if less than 85% were included but adequate steps were taken to ensure or demonstrate that this did not bias the results. We also examined the trial reports for any evidence of selective reporting of outcomes or any other issues that may bias the results. We reported the results of the assessment in a table.

Assessment of reporting biases

We planned to assess the probability of publication bias by examining the funnel plot for asymmetry, using one of the primary outcomes of seizure recurrence with the largest number of contributing trials. However, there were not enough trials reporting on the same primary outcomes to present a meaningful analysis.

Data synthesis

We analysed the data using Review Manager 5. We calculated risk ratio (RR) for dichotomous data and mean difference (MD) for continuous data. We measured precision using 95% confidence intervals (CI). Where more than one trial included similar participants and interventions, without significant clinical or methodological diversity or statistical heterogeneity, we undertook a meta‐analysis using a fixed‐effect model. Highly skewed data (where the standard deviation was greater than the mean) were presented in the text. Analyses were based on the number of available participants at each stage of follow up; there was no adjustment for loss to follow up.

We stratified the results by treatment comparison and type of lesion; viable (non‐enhancing) or non‐viable (enhancing).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We assessed heterogeneity between trials by examining the forest plot for overlapping confidence intervals, and using the I2 statistic for heterogeneity. We investigated potential sources of heterogeneity by performing subgroup analyses by co‐medications or treatments used and, where possible, length of follow up. We planned also to investigate potential sources of heterogeneity by performing subgroup analyses for participant age (adults or children), and number of lesions, but there were insufficient trials to enable this.

Sensitivity analysis

Where sufficient trial data were available, we undertook sensitivity analyses by excluding trials without adequate reported allocation concealment.

Results

Description of studies

Eligibility

We included 21 completed trials. (see 'Characteristics of included studies') We excluded nine studies (see reasons in 'Characteristics of excluded studies'). Three studies are classified as awaiting assessment because it was unclear from the reports whether or not they were randomized. We have emailed and written to the authors for more detailed information about the methods.The search also identified one ongoing trial that met the inclusion criteria (see 'Characteristics of ongoing studies').

In detail, the search strategy identified 48 potentially relevant reports of completed studies; of these, 35 initially seemed relevant, and we obtained the full texts. One was in Portuguese (Antoniuk 1991), the others in English. We obtained the help of a Portuguese reader to assess the relevant report for inclusion. Two reports were unclear as to whether the groups were randomly allocated: we attempted to contact the trial authors for clarification but were unsuccessful; these trials are reported as 'awaiting classification'. Following inspection of the reference lists of the included reports, we identified a further two relevant trials for inclusion (Padma 1994; Sotelo 1990), and another report that initially seemed relevant but did not meet the inclusion criteria (Medina 1993).

Trial location and setting

The included trials were conducted in Ecuador (five trials), Mexico (three trials), Peru (two trials), and India (11 trials). All were carried out within hospital settings, with treatment provided on an in‐patient basis.

Trial participants

Viable lesions

Six trials included 322 participants (151 males, 148 females, 23 sex not reported) with viable lesions, or a combination of viable and non‐viable lesions. Among these, four trials were conducted in adults (274 participants) and two trials included both children and adults (48 participants). Two trials did not specify the number of lesions, one trial included participants with up to three lesions, one trial with up to six lesions, and two trials with less than 20 lesions. All lesions in these studies were located in the parenchyma of the brain. None of the trials mentioned including or excluding people who were HIV positive.

Non‐viable lesions

Nine trials included 941 participants (44 males, 321 females and 176 sex not reported) with non‐viable lesions only. Among these, seven trials were conducted in children (763 participants) and two included both adults and children (178 participants). Six trials included only participants with single lesions, one trial included those with up to two lesions, one included those with up to three lesions, and one did not specify number of lesions. All lesions in these studies were located in the parenchyma of the brain. None of the trials mentioned including or excluding people who were HIV positive.

Mixed viable and non‐viable lesions

Seven trials included 676 participants (392 male, 280 female and four sex not reported) whose type of lesion was unspecified. Among these five trials were conducted in adults (469 participants) and two trials included both adults and children (207 participants). Five trials did not specify the number of lesions in each participant, while two trials included only participants with more than one lesion. Five trials included parenchymal lesions only, while one included only subarachnoid and intraventricular lesions and another included parenchymal, subarachnoid and intraventricular lesions. None of the trials mentioned including or excluding people who were HIV positive.

Interventions

Viable lesions

The comparisons included in the trials included:

Albendazole versus placebo or no drug (four trials) (Alarcon 1989; Garcia 1997; Alarcon 2001; Garcia 2004).

Albendazole versus praziquantel (two trials) (Sotelo 1990; Del Brutto 1999).

Albendazole: longer versus shorter duration of treatment (four trials) (Alarcon 1989; Sotelo 1990; Garcia 1997; Alarcon 2001).

Praziquantel: same daily dose given for different durations (one trial) (Sotelo 1990).

In addition to anthelmintics, three trials also used corticosteroids; two in all the comparison groups (Garcia 1997; Del Brutto 1999) and one in the treatment groups only (Garcia 2004). Most trials reported providing anticonvulsant drugs for all patients who were having seizures, whichever treatment group they were randomized to.

Non‐viable lesions

The comparisons included in the trials included:

Albendazole versus placebo or no drug (six trials) (Padma 1994; Baranwal 1998; Singhi 2000; Gogia 2003; Kalra 2003; De Souza 2009).

Albendazole plus praziquantel versus albendazole plus placebo (one trial) (Kaur 2009).

Albendazole: longer versus shorter duration of treatment (one trial) (Singhi 2003).

Albendazole with corticosteroids versus albendazole without corticosteroids (one trial) (Singhi 2004).

In addition to anthelmintics, five trials also used corticosteroids; three in the treatment and control groups (Baranwal 1998; Gogia 2003; Kaur 2009), one in the treatment groups only (Kalra 2003), and one in the control group and one of two intervention groups (Singhi 2004). Most trials reported providing anticonvulsant drugs for all patients who were having seizures, whichever treatment group they were randomized to.

Mixed viable and non‐viable lesions

The comparisons included in the trials included:

Albendazole versus placebo or no drug (five trials) (Sotelo 1988; Padma 1995; Garcia 1997; Das 2007; Carpio 2008).

Praziquantel versus placebo or no drug (one trial) (Sotelo 1988).

Albendazole versus praziquantel (one trial) (Sotelo 1988).

Albendazole: longer versus shorter duration of treatment (two trials) (Cruz 1995; Garcia 1997).

Albendazole: different doses given over a one‐day period (one trial) (Gongora‐Rivera 2006).

In addition to anthelmintics, five trials also used corticosteroids; three in the treatment and control groups (Garcia 1997; Gongora‐Rivera 2006; Carpio 2008), one in the treatment groups only (Das 2007), and one in the control group only (Sotelo 1988). Most trials reported providing anticonvulsant drugs for all patients who were having seizures, whichever treatment group they were randomized to.

One ongoing study is comparing albendazole plus corticosteroid with placebo (Gilman 2007).

Outcomes

Viable lesions

Three of the included trials reported outcomes relating to the presence or severity of seizures at follow up. A further trial reported on the presence or severity of any symptoms. All the trials reported on radiologically visible changes to the numbers or sizes of lesions.

Non‐viable lesions

Seven of the included trials reported outcomes relating to the presence or severity of seizures at follow up. All the trials reported on radiologically visible changes to the numbers or sizes of lesions.

Mixed viable and non‐viable lesions

Three of the included trials reported outcomes relating to the presence or severity of seizures at follow up. A further two reported on the presence or severity of any symptoms. All the included trials reported on radiologically visible changes to the numbers or sizes of lesions.

There were no trials reporting on freedom from seizures for one year, resumption of normal activities, reduction in ventricular size, or adverse events requiring withdrawal of anthelmintic drugs.

Risk of bias in included studies

Details of the methods used in each trial are available in the table 'Characteristics of included studies'.

Generation of allocation sequence

Viable lesions

Two trials described an adequate method of generating a truly random allocation sequence. Four trials did not report how they generated group allocation sequences (assessed as 'unclear'), but all were described as 'randomized'.

Non‐viable lesions

Seven trials described an adequate method of generating a truly random allocation sequence. Two trials did not report how they generated group allocation sequences (assessed as 'unclear'), but all were described as 'randomized'.

Mixed viable and non‐viable lesions

Three trials described an adequate method of generating a truly random allocation sequence. Four trials did not report how they generated group allocation sequences (assessed as 'unclear'), but all were described as 'randomized'.

Allocation concealment

Viable lesions

One trial reported an adequate method of ensuring allocation concealment. Five trials did not report enough information to allow allocation concealment to be assessed.

Non‐viable lesions

Four trials reported an adequate method of ensuring allocation concealment. Five trials did not report enough information to allow allocation concealment to be assessed.

Mixed viable and non‐viable lesions

Two trials reported an adequate method of ensuring allocation concealment. Five trials did not report enough information to allow allocation concealment to be assessed.

Blinding

Viable lesions

Three trials reported blinding of participants, personnel and outcomes assessors for all main outcomes. It was unclear whether blinding was done for the other three trials.

Non‐viable lesions

Five trials reported blinding of participants, personnel and outcomes assessors for all main outcomes. It was unclear whether blinding was done for three trials. One trial did not use blinding.

Mixed viable and non‐viable lesions

Four trials reported blinding of participants, personnel and outcomes assessors for all main outcomes. It was unclear whether blinding was done for three trials.

Addressing incomplete outcomes data

Viable lesions

Five trials either included 85% or over of the participants in the analysis, or included fewer than 85% of participants, but showed that participants who were not included were similar to those included. One trial did not meet this criteria.

Non‐viable lesions

Six trials either included 85% or over of the participants in the analysis, or included fewer than 85% of participants, but showed that participants who were not included were similar to those included. Two trials did not meet this criteria, while in one trial this was unclear.

Mixed viable and non‐viable lesions

Seven trials either included 85% or over of the participants in the analysis, or included fewer than 85% of participants, but showed that participants who were not included were similar to those included.

Effects of interventions

1. Albendazole versus placebo or no drug

1.1. Recurrence of seizures

Viable lesions

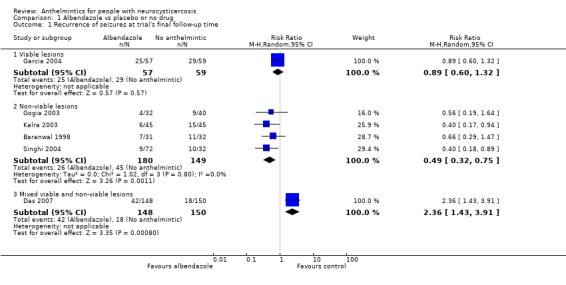

One small trial with adequate allocation concealment, including adults only, reported on recurrence of seizures by end of follow up, showing no significant effect of albendazole treatment (116 participants, Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Albendazole vs placebo or no drug, Outcome 1 Recurrence of seizures at trial's final follow‐up time.

Non‐viable lesions

Four trials reported data on this outcome that could be included within meta‐analysis. All four non‐viable lesions included only children with one or two lesions. Albendazole showed a significant benefit (relative risk 0.49, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.32 to 0.75; 329 participants, Analysis 1.1). One of the included trials (Gogia 2003) excluded seizures occurring during the first week of the trial, but is included in the analysis because its exclusion did not change the finding. In a sensitivity analysis, including only the three trials with adequate allocation concealment, this significant benefit remained (RR 0.53, 95% CI 0.31 to 0.88; 125 participants). One additional trial (103 participants, De Souza 2009) reported no significant differences in seizure recurrence between the albendazole and no anthelmintic groups, but did not present data.

Mixed viable and non‐viable lesions

One trial, with unclear allocation concealment, reported on this outcome, showing a harmful effect of albendazole (RR 2.36, 95% CI 1.43 to 3.91; 298 participants, one trial, Analysis 1.1). Another trial, with adequate allocation concealment, presented data on the number of participants who remained free of seizures at 12 months, using Kaplan‐Meier survival analysis, and found no significant difference between the albendazole and placebo groups (Carpio 2008).

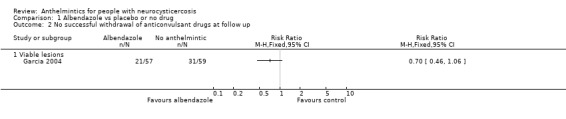

One trial reported on the successful withdrawal of anticonvulsants during a two‐year follow‐up period (Garcia 2004); there was no significant difference between the albendazole and control groups (116 participants, Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Albendazole vs placebo or no drug, Outcome 2 No successful withdrawal of anticonvulsant drugs at follow up.

1.2. Deaths and hospital admissions

Viable lesions

No trials reported on these outcomes.

Non‐viable lesions

No trials reported on these outcomes.

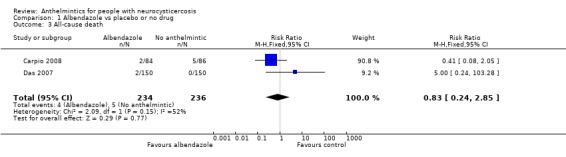

Mixed viable and non‐viable lesions

Two trials reported a total of nine deaths (Analysis 1.3). There was no significant difference between albendazole and treatment groups in the number of deaths overall (470 participants, two trials).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Albendazole vs placebo or no drug, Outcome 3 All‐cause death.

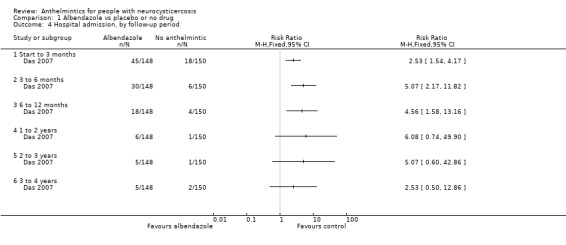

One trial (Das 2007) reported on hospital re‐admissions after treatment (Analysis 1.4). Participants treated with albendazole had a higher risk of hospital admission during the periods up to three months (RR 2.53, 95% CI 1.54 to 4.17; 298 participants), three to six months (RR 5.07, 95% CI 2.17 to 11.82), and six to 12 months (RR 4.56, 95% CI 1.58 to 13.16). There was no significant difference between the albendazole and control groups during periods one to two years, two to three years, or three to four years.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Albendazole vs placebo or no drug, Outcome 4 Hospital admission, by follow‐up period.

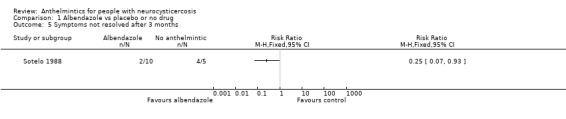

1.3. Resolution of symptoms

Viable lesions

In one very small trial, fewer participants receiving albendazole had no resolution of symptoms ('symptom' not defined by the trial authors) at three months than in the control group (RR 0.25, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.93; 15 participants, Analysis 1.5).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Albendazole vs placebo or no drug, Outcome 5 Symptoms not resolved after 3 months.

Non‐viable lesions

No trials in non‐viable lesions reported on these outcomes.

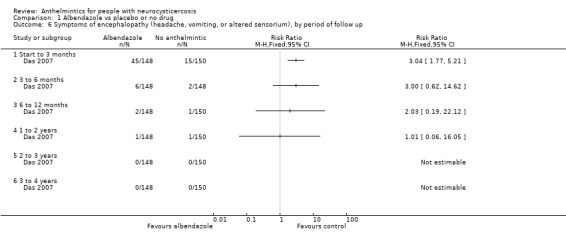

Mixed viable and non‐viable lesions

One trial reported on presence of symptoms of encephalopathy (headache, vomiting, and altered sensorium) during different time periods. The albendazole group had a higher risk of symptoms during the period up to three months (RR 3.04, 95% CI 1.77 to 5.21; 298 participants, Analysis 1.6), but there was no significant difference between the groups during other periods of time up to four years.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Albendazole vs placebo or no drug, Outcome 6 Symptoms of encephalopathy (headache, vomiting, or altered sensorium), by period of follow up.

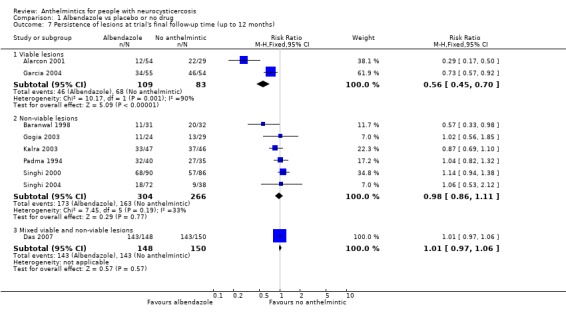

1.4. Persistence of radiological lesions

For the purposes of this review, persistence of lesions relates to the presence of cysts or lesions in any form, including calcified or nodular lesions.

Viable lesions

In trials including only adults with viable lesions, participants treated with albendazole compared with no anthelmintic had a lower risk of persistence of lesions at follow up (RR 0.56, 95% CI 0.45 to 0.70; 114 participants, two trials, Analysis 1.7)

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Albendazole vs placebo or no drug, Outcome 7 Persistence of lesions at trial's final follow‐up time (up to 12 months).

Non‐viable lesions

In trials including mainly children with non‐viable lesions (one trial also included adults), there was no difference between the albendazole and no anthelmintic groups in persistence of lesions at follow up (570 participants, six trials, Analysis 1.7). A trial in adults and children (103 participants, De Souza 2009) reported no significant difference in cyst disappearance between the albendazole and no anthelmintic groups but did not present the data.

Mixed viable and non‐viable lesions

In one trial including adults with both viable and non‐viable lesions, there was no difference between the albendazole and no anthelmintic groups in persistence of lesions at follow up (298 participants, Analysis 1.7).

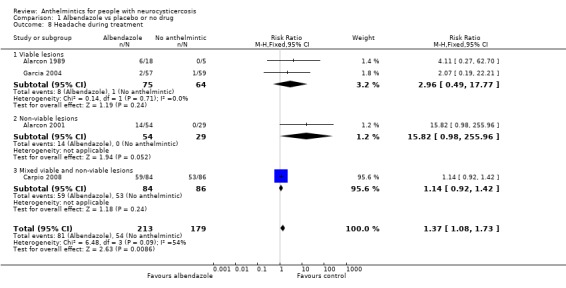

1.5. Adverse events during treatment

All types of lesion

There were no significant differences detected between the albendazole and no anthelmintic groups in the numbers of participants with headache during treatment in trials with viable lesions only (139 participants, two trials, Analysis 1.8), non‐viable lesions only (83 participants, one trial, Analysis 1.8), or mixed viable and non‐viable lesions (170 participants, one trial, Analysis 1.8). Overall, headache during treatment was more frequent in participants treated with albendazole than those not receiving anthelmintics (RR 1.37, 95% CI 1.08 to 1.73; 392 participants, four trials, Analysis 1.8).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Albendazole vs placebo or no drug, Outcome 8 Headache during treatment.

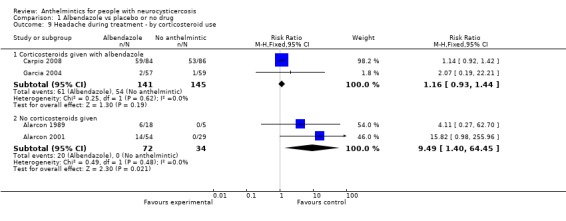

In a subgroup analysis by use of corticosteroids, there was a significant difference between the albendazole and no anthelmintic groups in headache during treatment when the albendazole group did not receive corticosteroids (RR 9.49, 95% CI 1.4 to 64.45; 106 participants, two trials, Analysis 1.9), but no significant difference in trials where participants in the albendazole group received corticosteroids.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Albendazole vs placebo or no drug, Outcome 9 Headache during treatment ‐ by corticosteroid use.

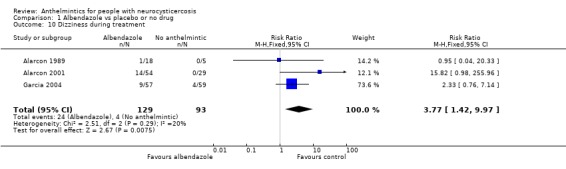

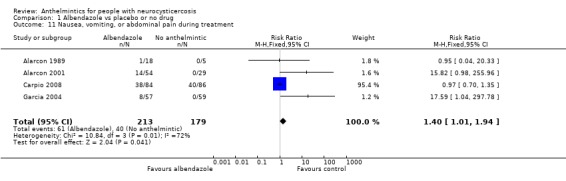

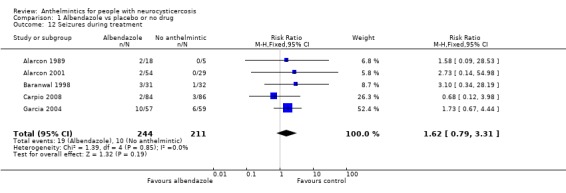

In analyses not separating trials by types of lesion, there was a greater risk of adverse events with albendazole for dizziness during treatment (Analysis 1.10), and nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain (Analysis 1.11). There was no significant difference between the albendazole and no anthelmintic groups in occurrence of seizures during treatment (455 participants, five trials, Analysis 1.12)

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Albendazole vs placebo or no drug, Outcome 10 Dizziness during treatment.

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Albendazole vs placebo or no drug, Outcome 11 Nausea, vomiting, or abdominal pain during treatment.

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Albendazole vs placebo or no drug, Outcome 12 Seizures during treatment.

2. Praziquantel versus placebo or no drug

One small trial made this comparison (15 participants, Sotelo 1988). The trial included participants with viable lesions, non‐viable lesions, or both. It did not report on recurrence of seizures, deaths or hospital admissions.

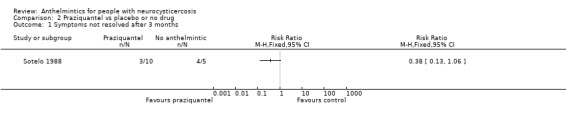

2.1. Resolution of symptoms

There was no significant difference between praziquantel and no anthelmintic for continuing presence of symptoms at three months (15 participants, Analysis 2.1).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Praziquantel vs placebo or no drug, Outcome 1 Symptoms not resolved after 3 months.

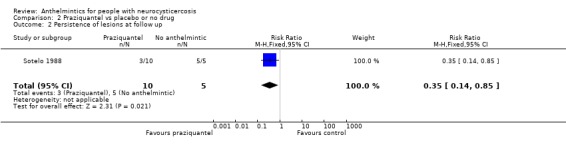

2.2. Radiological changes at follow up

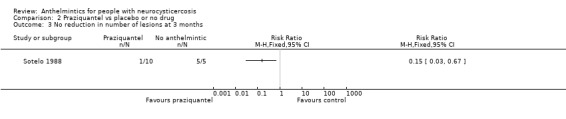

There was a significant difference between praziquantel and no anthelmintic in persistence of lesions at follow up (RR 0.15, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.67, 15 participants, Analysis 2.2). More participants treated with praziquantel than no anthelmintic had a reduction in the number of lesions at three months follow up (RR 0.15, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.67; 15 participants, Analysis 2.3).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Praziquantel vs placebo or no drug, Outcome 2 Persistence of lesions at follow up.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Praziquantel vs placebo or no drug, Outcome 3 No reduction in number of lesions at 3 months.

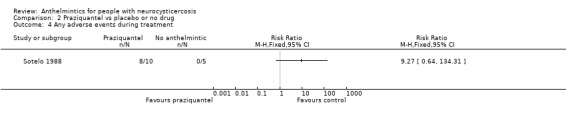

2.3. Adverse events during treatment

More participants treated with praziquantel compared with no anthelmintic reported any adverse event during treatment, although the difference was not significant (15 participants, Analysis 2.4).

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Praziquantel vs placebo or no drug, Outcome 4 Any adverse events during treatment.

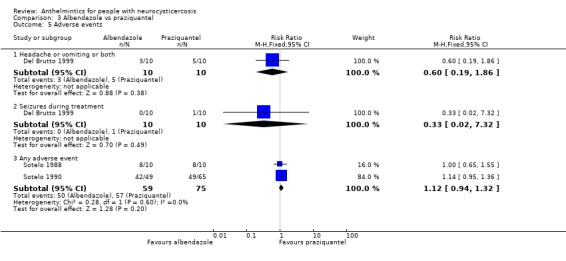

3. Albendazole versus praziquantel

Three trials reported on this comparison (Sotelo 1988; Sotelo 1990; Del Brutto 1999). All three trials included only participants with viable lesions.

3.1. Recurrence of seizures

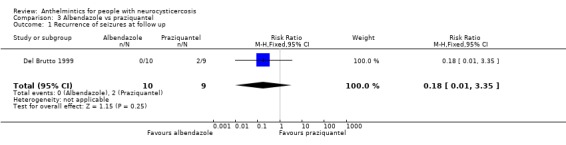

In one small trial, there was no significant difference in the risk of recurrence of seizures with albendazole treatment compared with praziquantel (19 participants, Analysis 3.1).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Albendazole vs praziquantel, Outcome 1 Recurrence of seizures at follow up.

3.2. Resolution of symptoms

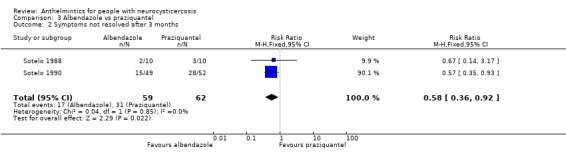

Fewer participants treated with albendazole compared with praziquantel still had symptoms of neurocysticercosis (types of symptoms not specified in the reports) three months after treatment (RR 0.58, 95% CI 0.36 to 0.92; 121 participants, two trials, Analysis 3.2).

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Albendazole vs praziquantel, Outcome 2 Symptoms not resolved after 3 months.

3.3. Persistence of radiological lesions at follow up

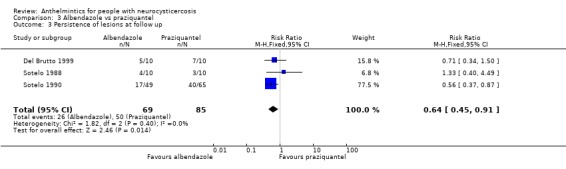

There was a significant benefit of albendazole over praziquantel in the number of participants with persistence of lesions at follow up at three to six months (RR 0.64, 95% CI 0.45 to 0.91; 154 participants, three trials, Analysis 3.3).

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Albendazole vs praziquantel, Outcome 3 Persistence of lesions at follow up.

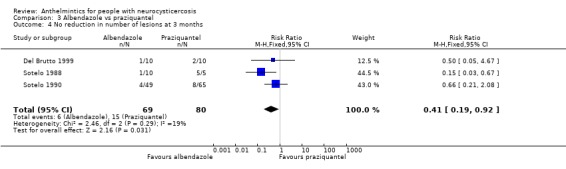

Significantly fewer participants in the albendazole group had more lesions, or the same number of lesions, at follow up than before treatment (RR 0.41, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.92; 149 participants, three trials, Analysis 3.4).

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Albendazole vs praziquantel, Outcome 4 No reduction in number of lesions at 3 months.

3.4. Adverse events during treatment

There were no significant differences between albendazole and praziquantel in the number of adverse events during treatment (Analysis 3.5).

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Albendazole vs praziquantel, Outcome 5 Adverse events.

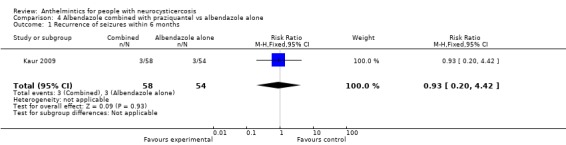

4. Albendazole combined with praziquantel versus albendazole alone

One trial, including only children with single non‐viable lesions, reported on this comparison.

4.1. Recurrence of seizures

There was no significant difference between the groups in recurrence of seizures at six months (112 participants, Analysis 4.1).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Albendazole combined with praziquantel vs albendazole alone, Outcome 1 Recurrence of seizures within 6 months.

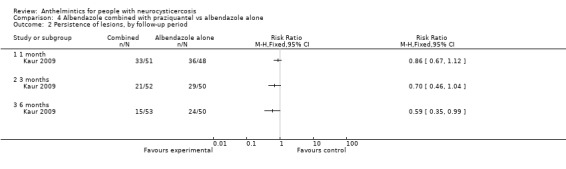

4.2 Persistence of radiological lesions

Albendazole combined with praziquantel was associated with lower risk of persistence of lesions at six months compared with albendazole alone (RR 0.59, 95% CI 0.35 to 0.99; 103 participants, Analysis 4.2). At one month and three months there was no significant difference between the groups, but there was a trend towards benefit of albendazole combined with praziquantel.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Albendazole combined with praziquantel vs albendazole alone, Outcome 2 Persistence of lesions, by follow‐up period.

4.3 Adverse events

Three children receiving albendazole combined with praziquantel and two children receiving albendazole alone developed headache on day three to four of treatment lasting for one or two days. None reported any gastrointestinal symptoms. There were no signs of raised intracranial pressure and none of the children required withdrawal of drugs.

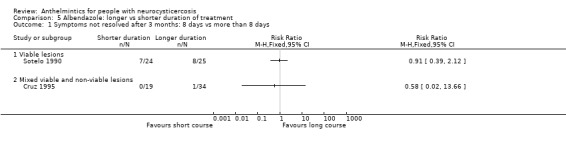

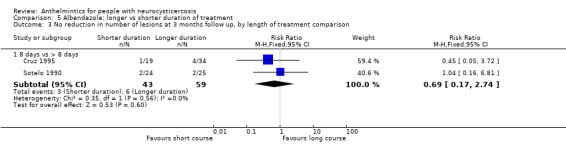

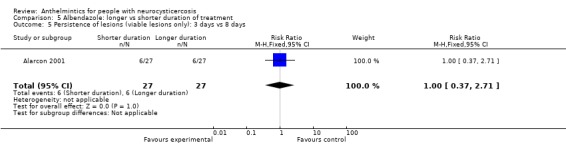

5. Albendazole: longer versus shorter duration of treatment

Six trials reported on this comparison (Alarcon 1989; Sotelo 1990; Cruz 1995; Garcia 1997; Alarcon 2001; Singhi 2003). This included three trials where participants had only viable lesions (Alarcon 1989; Sotelo 1990; Alarcon 2001), one trial including non‐viable lesions only (Singhi 2003), and two trials where participants had viable, non‐viable or both types of lesion (Cruz 1995; Garcia 1997).

5.1. Recurrence of seizures and resolution of symptoms

Viable lesions

One trial (Alarcon 2001) assessed the mean number of seizures at 12 months after treatment. The results were highly skewed, but there was no apparent difference between groups treated for eight days and groups treated for three days (54 participants, 0.3 (+/‐ 0.5) compared with 0.5 (+/‐1.0)).

One trial assessed the resolution of symptoms (not clearly defined in the trial report) three months after treatment. There was no difference between groups treated for up to eight days and more than eight days in the number of participants whose symptoms had not resolved (49 participants, Analysis 5.1).

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Albendazole: longer vs shorter duration of treatment, Outcome 1 Symptoms not resolved after 3 months: 8 days vs more than 8 days.

Non‐viable lesions

No trials made this comparison.

Mixed viable and non‐viable lesions

One trial assessed the resolution of symptoms (not clearly defined in the trial report) three months after treatment. There was no difference between groups treated for up to eight days and more than eight days in the number of participants whose symptoms had not resolved (53 participants, Analysis 5.1).

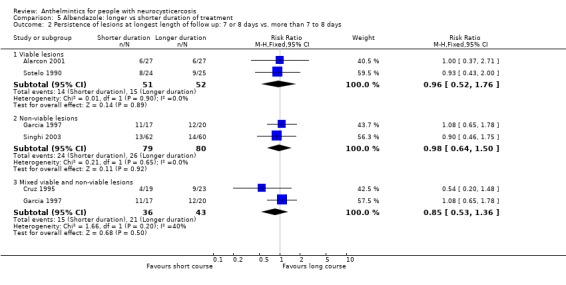

5.2. Persistence of radiological lesions

Viable lesions

There was no significant difference in persistence of lesions at final follow up between groups receiving albendazole for seven or eight days and longer than seven or eight days (103 participants, two trials, Analysis 5.2). There was also no significant difference between groups given albendazole for three days or eight days (54 participants, one trial).

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Albendazole: longer vs shorter duration of treatment, Outcome 2 Persistence of lesions at longest length of follow up: 7 or 8 days vs. more than 7 to 8 days.

Non‐viable lesions

There was no significant difference in persistence of lesions at final follow up between groups receiving albendazole for seven or eight days and longer than seven or eight days (159 participants, two trials, Analysis 5.2).

Mixed viable and non‐viable lesions

There was no significant difference in persistence of lesions at final follow up between groups receiving albendazole for seven or eight days and longer than seven or eight days (79 participants, two trials, Analysis 5.2).

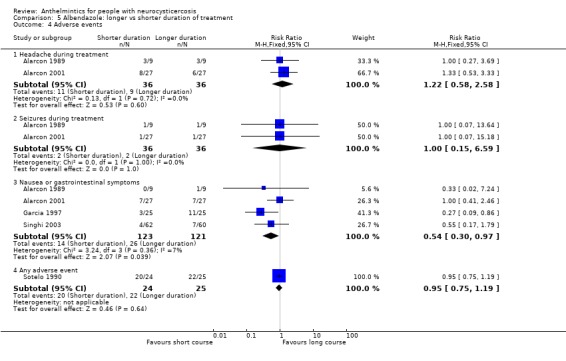

5.3. Adverse events

All types of lesion

In analyses not separating trials by type of lesion, participants receiving shorter treatment durations reported fewer cases of nausea or other gastrointestinal symptoms than those receiving longer treatments (RR 0.54, 95% CI 0.30 to 0.97; 244 participants, four trials, Analysis 5.4).

5.4. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Albendazole: longer vs shorter duration of treatment, Outcome 4 Adverse events.

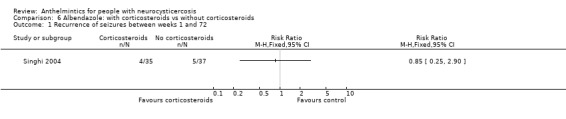

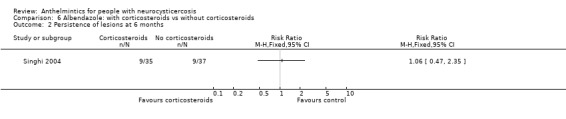

6. Albendazole: with corticosteroids versus without corticosteroids

One trial, including participants with non‐viable lesions only (Singhi 2004), made this comparison.

6.1 Recurrence of seizures

There was no significant difference between in recurrence of seizures during weeks one to 72 after treatment (72 participants, Analysis 6.1).

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Albendazole: with corticosteroids vs without corticosteroids, Outcome 1 Recurrence of seizures between weeks 1 and 72.

6.2 Radiological resolution of lesions

There was no significant difference between albendazole alone and albendazole with corticosteroids in the persistence of lesions at six months after treatment (72 participants, Analysis 6.2).

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Albendazole: with corticosteroids vs without corticosteroids, Outcome 2 Persistence of lesions at 6 months.

6.3 Adverse events

This trial did not report on adverse events.

Discussion

Summary of main results

The results of trials comparing anthelmintic treatment with no anthelmintic are mixed and therefore difficult to interpret. Most trials assessed albendazole, which has largely taken over from praziquantel. We found only one small trial comparing praziquantel with no active treatment from which we could not come to any meaningful conclusions on its efficacy. Reduction in seizures with albendazole did not appear to correlate with radiological clearance of lesions. Findings for the three major outcomes categories of this review are described below.

Seizure recurrence

For seizure recurrence, most trials tended towards a benefit of albendazole, and this benefit was significant in the case of children with a single, non‐viable lesion. This finding runs counter to most expert opinion which is of a view that treatment is unlikely to be beneficial for cases with non‐viable lesions only. There was no significant benefit shown for people with viable lesions only, which seems counter‐intuitive, but only one small trial reported on this outcome, hence a larger study is needed to ascertain the efficacy of albendazole in this group. One trial, including participants with both viable and non‐viable lesions (Das 2007), showed a harmful effect of albendazole. This trial, which combined albendazole with steroids, also showed increased encephalopathy and admission to hospital with albendazole, and two deaths from encephalopathy.

Radiological clearance of lesions

For radiological clearance of lesions during the first 12 months, trials including people with viable lesions only showed a significant benefit of albendazole, while trials including only people with non‐viable lesions, or a mixture of viable and non‐viable lesions, showed no significant effect of albendazole. The majority of trials on viable lesions involved adults only, while those on non‐viable lesions involved only children; the observed differences between trial results may also have been affected by the ages of the participants.

Our analysis showed no significant effect of duration of treatment on persistence of lesions at follow up. Assuming that presence of symptoms is associated with presence of lesions (Murthy 2006), these results suggest that a shorter duration of treatment is as effective as a longer course. Shorter courses were also associated with fewer cases of nausea or other gastrointestinal symptoms during treatment. One trial assessed albendazole in combination with praziquantel compared with albendazole alone; the findings suggested that the combination of two anthelmintics was better in the short term.

Adverse events

Participants treated with either albendazole or praziquantel experienced significantly more adverse events during treatment than those receiving no active treatment. Albendazole was associated with headache, dizziness, and nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain. There is some indirect (weak) evidence that corticosteroids used in conjunction with albendazole may protect against headache during treatment, as in trials using corticosteroids there was no significant difference between albendazole and no active treatment in this outcome.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

We identified 21 relevant published trials. Most were published since the last update of this Cochrane Review (Salinas 1999). We also identified one relevant ongoing trial. All the trials were small; the largest enrolled 300 participants and the smallest enrolled 18. All trials, published and ongoing, were based in Central and South America and South‐East Asia; there were no trials from Africa or China, where the disease is also endemic.

The trial participants varied, including children and adults and people with different numbers and types of lesions, although trials in children tended to include only non‐viable lesions, while trials in adults mostly included only viable lesions. Together the trials included very few people with large numbers of lesions, or with lesions other than parenchymal cysts or lesions.

Treatment comparisons of the included trials were wide ranging, enabling analysis by type of drug (albendazole or praziquantel) and duration of treatment. We were also able to indirectly compare the frequencies of adverse events during treatment when anthelmintics were administered with or without corticosteroids.

Two comparisons reported by the included trials are not presented in the analysis because their comparisons did not fit into its structure. Gongora‐Rivera 2006 compared only different doses of albendazole given for just one day; this was not presented as we had no other trials using albendazole for just one day, and hence no evidence that it was better than placebo. Sotelo 1990 compared praziquantel given for different durations; this comparison was not presented because we found no evidence that praziquantel was effective in treating neurocysticercosis.

Just over half of the included trials reported on the presence or severity of seizures, which are probably the most important outcomes to most patients. Three other trials reported on symptom severity or presence of symptoms, of which seizures would be the most common, and one trial reported separately on symptoms other than seizures. All the trials assessed and reported on the radiological presence or changes in the neurocysticerci, which may not be directly correlated with the presence or severity of seizures or other symptoms. Radiological outcomes are easy to assess, specific to neurocysticercosis, and perhaps clinically useful, as there is evidence that anti‐epileptic drugs can usually be withdrawn following radiological clearance of lesions, and this may be a criteria for withdrawing anti‐epileptic drugs in some patients and practices (Murthy 2006). However, in this review, children with a single non‐viable lesion, and treated with albendazole compared with no anthelmintic, had a lowered risk of recurrence of seizures despite no difference in the radiological persistence of lesions.

Quality of the evidence

The risk of bias varied between trials, with the trials published most recently tending to be assessed as better for all indicators. Six trials reported an adequate method of allocation concealment; one trial including viable lesions only, four including non‐viable lesions only, and two including both viable and non‐viable lesions.

Potential biases in the review process

All of the included trials were small. In addition, unexplained heterogeneity was introduced by one relatively large, but poorly reported trial (Das 2007) with results mostly running in the opposite direction to those reported in other trials.

Agreements and disagreement with other studies and reviews

Our results slightly vary from other recent meta‐analyses assessing albendazole compared with placebo or usual care, but the conclusions reached are similar.

A meta‐analysis in children (four trials, 400 participants) with neurocysticercosis revealed a higher remission of seizures in those treated with albendazole compared to controls (RR 1.26, 95% CI 1.09 to 1.46). This agrees with our findings in children with non‐viable lesions only. The authors also reviewed 10 observational studies and found conflicting results (Mazumdar 2007).

Del Brutto and colleagues (Del Brutto 2006) reported a meta‐analysis of 11 randomized trials of patients with neurocysticercosis located in or adjacent to the cerebral parenchyma. Anthelmintic drug therapy was associated with complete resolution of viable lesions (44% versus 19%; P = 0.025) at follow up. Trials on non‐viable lesions showed a trend toward lesion resolution favouring anthelmintic drugs (72% versus 63%; P = 0.38), but this was not significant. In patients with non‐viable lesions, risk for seizure recurrence was lower after anthelmintic treatment (14% versus 37%; P < 0.001). The single trial evaluating the frequency of seizures in patients with non‐viable lesions showed a 67% reduction in the rate of generalized seizures with treatment (P = 0.006).

As far as we know, there have been no other meta‐analyses undertaken to compare different durations of treatment.

Ongoing trials are still using regimens of 10 days albendazole (Gilman 2007) despite evidence that shorter treatment durations may be as effective. These findings have implications relating to cost and patient choice and adherence in what may be an expensive disease to treat; a recent study in India reported that the total costs per patient of treating seizures associated with a single cysticerci in the brain may be equivalent to around half the per capita Gross National Product of the country (Murthy 2007).

Current consensus guidelines for the treatment of neurocysticercosis (Garcia 2002; Nogales‐Gaete 2006) do not give any definitive advice on anthelmintic treatment for patients with five or fewer, or more than 100, viable lesions, or fewer than 100 non‐viable lesions. This review presents evidence that albendazole treatment may reduce the recurrence of seizures in children with a single non‐viable lesion, and reduce the persistence of lesions in neuroimaging in persons with small numbers of viable lesions. We did not find enough evidence to draw any conclusions on the safety and effectiveness of treatment for heavy parenchymal infection or extra‐parenchymal (subarachnoid or ventricular) neurocysticercosis. There is also no current consensus on the use of corticosteroids when anthelmintics are used in cases of five or fewer viable cysts, or fewer than 100 non‐viable lesions. This review presents evidence that corticosteroids may reduce the incidence of adverse events during treatment, even in people with only non‐viable lesions or with small numbers of viable lesions.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

For children with parenchymal neurocysticercosis, and with small numbers of non‐viable neurocysticercosis lesions in the brain, albendazole treatment at the standard dose may reduce the risk of recurrence of seizures in the medium term (six to 18 months). However, it is still unclear whether and how different groups benefit from albendazole treatment. There is some evidence that parasite clearance may be speeded up in patients with viable lesions, but no evidence that this has any impact on seizure recurrence. Short courses of seven days or less are as effective as longer courses, although there is not enough evidence to say what the optimum duration of treatment is. Adverse events during treatment, including headache, dizziness, and gastrointestinal symptoms, are common. There is some indirect evidence that they may be reduced by giving corticosteroids with the albendazole and prescribing albendazole for the minimum effective duration, but this needs to be evaluated through randomized comparisons.

There is not enough evidence available to assess the effects of praziquantel treatment in any group, or albendazole treatment in people with moderate or heavy infections or extra‐parenchymal cysts. It is not known whether people who are HIV positive will respond to treatment in the same way, as it is assumed that most participants in the included studies were HIV negative.

Implications for research.

Further good quality, randomized controlled trials are needed to assess the effectiveness of albendazole treatment in different groups of patients, including adults and children, and people with different stages and numbers of lesions (less than five, five to 100 and more than 100). Some trials should include participants with heavy parenchymal infections, and those with any kind of extra‐parenchymal infection. At least one trial should also include participants who are HIV positive, as HIV infection is common in Africa where neurocysticercosis is also common. Trials should carefully assess, record, and analyse the outcomes likely to be of most interest to the patient, including adverse events during treatment, recurrence of seizures, and successful withdrawal of anti‐epileptic drugs.

Once it is clear which groups might benefit from albendazole treatment, trials should assess the optimal dosage and duration of albendazole treatment for different groups of people with different forms of neurocysticercosis. These should compare treatment of seven days duration with shorter durations, including treatment for as few as three days.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 15 February 2010 | Amended | corrected search dates in abstract |

| 1 September 2009 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | This review replaces an earlier Cochrane Review 'Drugs for treating neurocysticercosis (tapeworm infection of the brain)' (Salinas 1999), which was withdrawn from The Cochrane Library in 2005 due to the availability of new trial evidence. A new team of authors worked on this review. The criteria for inclusion of trials has changed. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 4, 2006 Review first published: Issue 2, 1996

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 5 May 2009 | New search has been performed | Search updated; see 'Search methods for identification of studies'. |

Acknowledgements

This review replaces the Salinas 1999 Cochrane Review. The authors are grateful to Rodrigo Salinas and colleagues for having the opportunity to update this review by drafting a new protocol for the update. The authors would like to acknowledge that much of this protocol is based upon the Salinas 1999 Cochrane Review.

This document is an output from a project funded by the UK Department for International Development (DFID) for the benefit of developing countries. The views expressed are not necessarily those of DFID.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search methods: detailed search strategies

| Search set | CIDG SRa | CENTRAL | MEDLINEb | EMBASEb | LILACSb |

| 1 | Taenia solium | NEUROCYSTICERCOSIS | Taenia solium | Taenia solium | Taenia solium |

| 2 | cysticercosis | Taenia solium | cysticercosis | neurocysticercosis | neurocysticercosis |

| 3 | neurocysticercosis | 1 or 2 | neurocysticercosis | BRAIN CYSTICERCOSIS | 1 or 2 |

| 4 | — | — | 1 or 2 or 3 | 1 or 2 or 3 | albendazole |

| 5 | — | — | albendazole | albendazole | praziquantel |

| 6 | — | — | praziquantel | praziquantel | metrifonate |

| 7 | — | — | pyquiton | metrifonate | 4 or 5 or 6 |

| 8 | — | — | metrifonate | 5 or 6 or 7 | 3 and 7 |

| 9 | — | — | 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 | 3 and 8 | — |

| 10 | — | — | 4 and 9 | Limit 9 to human | — |

| 11 | — | — | Limit 10 to human | — | — |

aCochrane Infectious Diseases Group Specialized Register. bSearch terms used in combination with the search strategy for retrieving trials developed by The Cochrane Collaboration (Lefebvre 2008); upper case: MeSH or EMTREE heading; lower case: free text term.

Appendix 2. Trial description: lesion type

| Lesion type | No. trials | Trial |

| Viable, non‐enhancing, or without surrounding oedema, or, if mixed, at least one viable lesion per participant | 7 | Alarcon 1989; Sotelo 1990; Garcia 1997; Del Brutto 1999; Alarcon 2001; Garcia 2004 |

| Non‐viable, enhancing or with surrounding oedema | 9 | Padma 1994; Baranwal 1998; Singhi 2000; Gogia 2003; Kalra 2003; Singhi 2003; Singhi 2004; De Souza 2009; Kaur 2009 |

| Any stage of lesion(s) or types of lesion not described | 7 | Sotelo 1988; Cruz 1995; Padma 1995; Garcia 1997; Gongora‐Rivera 2006; Carpio 2008; Das 2007 |

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Albendazole vs placebo or no drug.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Recurrence of seizures at trial's final follow‐up time | 6 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Viable lesions | 1 | 116 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.89 [0.60, 1.32] |

| 1.2 Non‐viable lesions | 4 | 329 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.49 [0.32, 0.75] |

| 1.3 Mixed viable and non‐viable lesions | 1 | 298 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.36 [1.43, 3.91] |

| 2 No successful withdrawal of anticonvulsant drugs at follow up | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2.1 Viable lesions | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3 All‐cause death | 2 | 470 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.83 [0.24, 2.85] |

| 4 Hospital admission, by follow‐up period | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 4.1 Start to 3 months | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4.2 3 to 6 months | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4.3 6 to 12 months | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4.4 1 to 2 years | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4.5 2 to 3 years | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4.6 3 to 4 years | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5 Symptoms not resolved after 3 months | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 6 Symptoms of encephalopathy (headache, vomiting, or altered sensorium), by period of follow up | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 6.1 Start to 3 months | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 6.2 3 to 6 months | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 6.3 6 to 12 months | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 6.4 1 to 2 years | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 6.5 2 to 3 years | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 6.6 3 to 4 years | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 7 Persistence of lesions at trial's final follow‐up time (up to 12 months) | 9 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 7.1 Viable lesions | 2 | 192 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.56 [0.45, 0.70] |

| 7.2 Non‐viable lesions | 6 | 570 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.86, 1.11] |

| 7.3 Mixed viable and non‐viable lesions | 1 | 298 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.97, 1.06] |

| 8 Headache during treatment | 4 | 392 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.37 [1.08, 1.73] |

| 8.1 Viable lesions | 2 | 139 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.96 [0.49, 17.77] |

| 8.2 Non‐viable lesions | 1 | 83 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 15.82 [0.98, 255.96] |

| 8.3 Mixed viable and non‐viable lesions | 1 | 170 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.14 [0.92, 1.42] |

| 9 Headache during treatment ‐ by corticosteroid use | 4 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 9.1 Corticosteroids given with albendazole | 2 | 286 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.16 [0.93, 1.44] |

| 9.2 No corticosteroids given | 2 | 106 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 9.49 [1.40, 64.45] |

| 10 Dizziness during treatment | 3 | 222 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.77 [1.42, 9.97] |

| 11 Nausea, vomiting, or abdominal pain during treatment | 4 | 392 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.40 [1.01, 1.94] |

| 12 Seizures during treatment | 5 | 455 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.62 [0.79, 3.31] |

Comparison 2. Praziquantel vs placebo or no drug.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Symptoms not resolved after 3 months | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2 Persistence of lesions at follow up | 1 | 15 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.35 [0.14, 0.85] |

| 3 No reduction in number of lesions at 3 months | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 4 Any adverse events during treatment | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

Comparison 3. Albendazole vs praziquantel.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Recurrence of seizures at follow up | 1 | 19 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.18 [0.01, 3.35] |

| 2 Symptoms not resolved after 3 months | 2 | 121 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.58 [0.36, 0.92] |

| 3 Persistence of lesions at follow up | 3 | 154 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.64 [0.45, 0.91] |

| 4 No reduction in number of lesions at 3 months | 3 | 149 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.41 [0.19, 0.92] |

| 5 Adverse events | 3 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 5.1 Headache or vomiting or both | 1 | 20 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.6 [0.19, 1.86] |

| 5.2 Seizures during treatment | 1 | 20 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.33 [0.02, 7.32] |

| 5.3 Any adverse event | 2 | 134 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.12 [0.94, 1.32] |

Comparison 4. Albendazole combined with praziquantel vs albendazole alone.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Recurrence of seizures within 6 months | 1 | 112 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.20, 4.42] |

| 2 Persistence of lesions, by follow‐up period | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2.1 1 month | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.2 3 months | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.3 6 months | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

Comparison 5. Albendazole: longer vs shorter duration of treatment.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Symptoms not resolved after 3 months: 8 days vs more than 8 days | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.1 Viable lesions | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.2 Mixed viable and non‐viable lesions | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2 Persistence of lesions at longest length of follow up: 7 or 8 days vs. more than 7 to 8 days | 5 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 Viable lesions | 2 | 103 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.52, 1.76] |

| 2.2 Non‐viable lesions | 2 | 159 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.64, 1.50] |

| 2.3 Mixed viable and non‐viable lesions | 2 | 79 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.85 [0.53, 1.36] |

| 3 No reduction in number of lesions at 3 months follow up, by length of treatment comparison | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 8 days vs > 8 days | 2 | 102 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.69 [0.17, 2.74] |

| 4 Adverse events | 5 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 4.1 Headache during treatment | 2 | 72 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.22 [0.58, 2.58] |

| 4.2 Seizures during treatment | 2 | 72 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.15, 6.59] |

| 4.3 Nausea or gastrointestinal symptoms | 4 | 244 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.54 [0.30, 0.97] |

| 4.4 Any adverse event | 1 | 49 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.95 [0.75, 1.19] |

| 5 Persistence of lesions (viable lesions only): 3 days vs 8 days | 1 | 54 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.37, 2.71] |

5.3. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Albendazole: longer vs shorter duration of treatment, Outcome 3 No reduction in number of lesions at 3 months follow up, by length of treatment comparison.

5.5. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Albendazole: longer vs shorter duration of treatment, Outcome 5 Persistence of lesions (viable lesions only): 3 days vs 8 days.

Comparison 6. Albendazole: with corticosteroids vs without corticosteroids.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Recurrence of seizures between weeks 1 and 72 | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2 Persistence of lesions at 6 months | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Alarcon 1989.

| Methods | Randomized controlled trial Duration: dates not supplied. Participants followed up for 4 months |

|

| Participants | Number: 23 enrolled; numbers of males and females not presented Inclusion criteria: adults and children aged > 13 years, with 1 to 3 parenchymal cysts > 10 mm without perilesional oedema, good general health and stable neurological disease Exclusion criteria: parenchymal cysts with ring enhancement and oedema surrounding the lesions, pregnant women Type of lesion: viable |

|

| Interventions | Group 1. Albendazole: 15 mg/kg bodyweight for 3 days Group 2. Albendazole: 15 mg/kg bodyweight for 30 days Group 3. No albendazole | |

| Outcomes | Included in the review: number of cysts and total diameter of cysts at baseline and 1 day, 30 days, and 3 months after treatment finishes. Adverse events | |

| Notes | Location: Ecuador Source of funding: not stated |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | Quote: "randomly allocated" Decision: probably done, but unclear |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not described. Placebos were not used and different groups received follow‐up scans at different times Decision: unclear, probably not done |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | 23 randomized and follow‐up data available for all (100%) |

| Free of selective reporting? | Low risk | No evidence of selective reporting; outcomes reported individually for all participants |

| Free of other bias? | Low risk | No evidence of other bias |

Alarcon 2001.

| Methods | Randomized controlled trial Duration: participants recruited between January 1989 and December 1996, and followed up for 12 months |

|

| Participants | Number: 95 enrolled, data available for 83 (36 male, 47 female) Inclusion criteria: adults with neurological signs and symptoms and 1 to 6 non‐enhancing parenchymal cysts without perilesional oedema Exclusion criteria: ring or nodular cysts, oedema surrounding the lesions, subarachnoid or intraventricular cysts, hydrocephalus, previous treatment with albendazole or praziquantel, pregnant women, intracranial hypertension Type of lesion: viable |

|

| Interventions | Group 1. Albendazole: 15 mg per kg bodyweight for 3 days Group 2. Albendazole: 15 mg per kg bodyweight for 8 days Group 3. No albendazole | |

| Outcomes | Included in the review: number of cysts at baseline, 3 months, and 6 months; persistence of cysts at 3 months and 12 months; number of seizures per year at baseline and 12 months; adverse events associated with treatment | |

| Notes | Location: Ecuador Source of funding: not stated |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | Method not described, but trial described as 'randomized' Decision: unclear, but probably done |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Not described Decision: unclear |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "Evaluation of the number of cysts on CT at baseline and at follow‐up was performed by a single neuroradiologist blinded to the treatment allocation" |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | 95 participants randomized; 8 excluded before starting treatment, 4 lost to follow up (87% included in the analysis) |

| Free of selective reporting? | Low risk | No evidence of selective reporting |

| Free of other bias? | Low risk | No evidence of other bias |

Baranwal 1998.

| Methods | Randomized controlled trial Duration: dates not supplied. Participants followed up for 24 months. |

|

| Participants | Number: 63 enrolled, 57 included in analysis (33 male, 24 female) Inclusion criteria: children aged 2 years to 12 years with a single small enhancing lesion in brain parenchyma plus seizures for less than 3 months Exclusion criteria: neurologic deficit or suspected tuberculosis Type of lesion: non‐viable |

|

| Interventions | Group 1. Albendazole: 15 mg per kg bodyweight for 28 days, plus 1 to 2 mg prednisolone per day for 5 days Group 2. Placebo, plus 1 to 2 mg prednisolone per day for 5 days | |

| Outcomes | Included in the review: recurrence of seizures at 3 months after treatment; persistence of lesion at 1 month and 3 months; recurrence of seizures 8 months after tapering anticonvulsants after 18 to 24 months seizure‐free following treatment Not included in the review: calcification of lesion at 3 months; lesion diameter at baseline and 1 month |

|

| Notes | Location: India Source of funding: not stated |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | Quote: "...numbered in a random sequence using a random number table" Decision: done |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Quote: "Envelopes containing albendazole or placebo capsules for the full course of therapy were prepared in advance and numbered in a random sequence" Decision: done |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "All persons involved in the study i.e. patient, clinical investigator and neuroradiologist were blind to the random allocation. Results were decoded after completion of 6 months of study to identify the groups" Decision: done |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | 63 randomized, 6 lost to follow up (90% included in the analysis) |

| Free of selective reporting? | Low risk | No evidence of selective reporting |

| Free of other bias? | Low risk | No evidence of other bias |

Carpio 2008.

| Methods | Randomized controlled trial Duration: dates not supplied. Participants followed up for 12 months Inclusion of randomized participants in the analysis: 161/178 = 90% (in addition, 7 died) |

|

| Participants | Number: 178 enrolled, 97 male, 77 female; 4 with missing data on sex Inclusion criteria: any age or gender with new onset symptoms associated with neurocysticercosis within 2 months prior to recruitment, and neurocysticercosis cysts an axial CT or MRI imaging of the brain. Could include 1 or more active parenchymal cysts, degenerative or transitional parenchymal cysts, or cysts with a extra‐parenchymal location. Exclusion criteria: having only calcified cysts, pregnancy, papilloedema, active tuberculosis, syphilis, ocular cysticercosis, active gastric ulcers or any progressive or life‐threatening disorder Type of lesion: viable or non‐viable cysts, or a combination of the two |

|

| Interventions | Group 1: For participants weighing more than 50 kg, 400 mg of albendazole every 12 hours for 8 days. For participants weighing less than 50 kg, including children, 15 mg per kg bodyweight per day for 8 days. Participants weighing over 50 kg also received 75 mg prednisolone daily for 8 days, then 50 mg per day for 1 week, then 25 mg per day for 1 week. Participants weighing less than 50 kg received 1.5 mg per kg bodyweight prednisone for 8 days, then 1 mg per kg for 1 week, then 0.5 mg for 1 week. Group 2: Placebo with an identical appearance to albendazole, plus prednisolone as for Group 1 |

|

| Outcomes | Included in the review: freedom from seizures for 12 months following treatment; mean time seizure‐free following treatment; freedom from cysts 1 month, 6 months and 12 months following treatment; reduction in the number of cysts 1 month, 6 months and 12 months following treatment; deaths due to cysticercosis; all‐cause deaths; adverse events during treatment, and during the first month following treatment | |

| Notes | Location: Ecuador Source of funding: NINDS grant R01‐NS39403. Glaxo/SKB and Acromax Co supplied the active drug and placebo |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | Quote: "Patients were allocated to treatment group according to a stratified block randomisation schedule. Two strata were considered: centre (sex centres) and location of the cyst (parenchymal versus extraparenchymal). Permuted blocks of size 4 and 6 were used to balance the treatment allocation within each stratum" Decision: done |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Quote: "The randomisation lists were kept in electronic form on a computer accessible only to the statistician" Decision: done |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Low risk | Quotes: "All other research staff were blinded to the treatment arm"... "double‐blind, placebo controlled trial" Decision: done |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | Of 178 participants, 161 (90%) were followed up and included in the analysis. In addition, 7 died. |

| Free of selective reporting? | Low risk | No evidence of selective reporting |

| Free of other bias? | Low risk | No evidence of other bias |

Cruz 1995.

| Methods | Randomized controlled trial Duration: dates not specified. Participants followed up for 4 months. |

|

| Participants | Number: 61 enrolled, 53 included in the analysis (33 male, 20 female) Inclusion criteria: adults with cystic or encephalitic forms of cerebral cysticercosis ‐ any developmental stage of the parasite, localization parenchymous, subarachnoid, or ventricular Exclusion criteria: patients in a coma or generally poor condition Type of lesion: mixed viable, non‐viable, and both viable and non‐viable |

|

| Interventions | Group 1. Albendazole: 800 mg per day for 8 days Group 2. Albendazole: 800 mg per day for 15 days Group 3. Albendazole: 800 mg per day for 30 days | |

| Outcomes | Included in the review: persistence of cysts at 3 months; number of cysts at baseline and 3 months; symptom change at 3 months; adverse events | |

| Notes | Location: Ecuador Source of funding: partially funded by SmithKline Beecham Pharmaceuticals |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | Quote: "...were randomised to one of 3 different treatment groups" Decision: unclear, probably done |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Not described Decision: unclear |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not described. Participants were treated for different durations, without the use of placebos. Decision: unclear, probably not done |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | Of 61 participants randomized, 53 completed 3 months follow up (87%) |

| Free of selective reporting? | Low risk | No evidence of selected reporting |