Abstract

Background

Health workers recommend bathing, sponging, and other physical methods to treat fever in children and to avoid febrile convulsions. We know little about the most effective methods or how these methods compare with commonly used drugs.

Objectives

To evaluate the benefits and harms of physical cooling methods used for managing fever in children.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group's trials register (October 2005), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library Issue 3, 2005), MEDLINE (1966 to October 2005), EMBASE (1988 to October 2005), LILACS (October 2005), CINAHL (1982 to October 2005), Science Citation Index (1981 to October 2005), and reference lists of articles. We also contacted researchers in the field.

Selection criteria

Randomized and quasi‐randomized controlled trials comparing physical methods with a drug placebo or no treatment in children with fever of presumed infectious origin. We included studies where children in both groups were given an antipyretic drug.

Data collection and analysis

Two reviewers independently assessed trial methodological quality. One reviewer extracted data and the other checked the data for accuracy. Results were expressed as risk ratio with 95% confidence intervals for binary outcomes, and mean difference for continuous data.

Main results

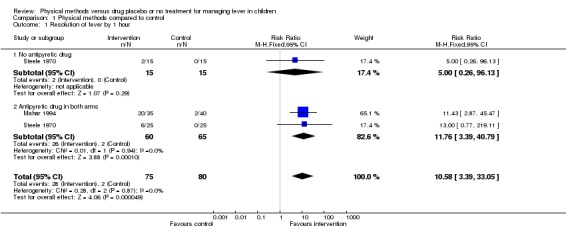

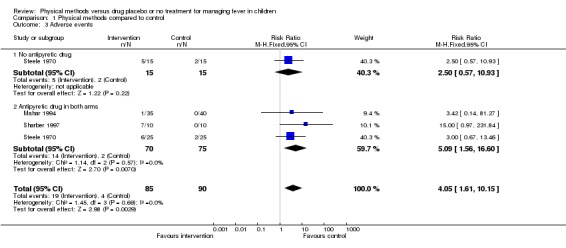

Seven trials, involving 467 participants, met the inclusion criteria. One small trial (n = 30), comparing physical methods with drug placebo, did not demonstrate a difference in the proportion of children without fever by one hour after treatment in a comparison between physical methods alone and drug placebo. In two studies, where all children received an antipyretic drug, physical methods resulted in a higher proportion of children without fever at one hour (n = 125; risk ratio 11.76; 95% confidence interval 3.39 to 40.79). In a third study (n = 130), which only reported mean change in temperature, no difference was detected. Mild adverse events (shivering and goose pimples) were more common in the physical methods group (3 trials; risk ratio 5.09; 95% confidence interval 1.56 to 16.60).

Authors' conclusions

A few small studies demonstrate that tepid sponging helps to reduce fever in children.

Keywords: Adolescent; Child; Child, Preschool; Humans; Infant; Acetaminophen; Acetaminophen/therapeutic use; Analgesics, Non‐Narcotic; Analgesics, Non‐Narcotic/therapeutic use; Baths; Baths/adverse effects; Baths/methods; Cryotherapy; Cryotherapy/adverse effects; Cryotherapy/methods; Fever; Fever/therapy; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Physical methods for treating fever in children

Plain language summary pending.

Background

Physical cooling of people with fever

Fever is a common response of the body to infection (Kluger 1992). Fever makes people feel unwell and can result in serious complications such as convulsions (Behrmann 2000). Febrile convulsions are the most common type of convulsions in childhood and are known to affect about two to five per cent of all children (Verity 1985). About 30 per cent of those who have had an episode of febrile convulsions will also have additional convulsions (Stuijvenberg 1999).

Physical methods for cooling are often recommended for treating fever (Axelrod 2000). The methods most commonly used include tepid sponging, bathing, fanning, and cooling blankets (Caruso 1992; Axelrod 2000). Rubbing alcohol on the skin, cool enemas, and ice packs have also been used for cooling the body during fever, but there are indications that these methods may cause severe adverse effects (Senz 1958; Steele 1970). In exceptional cases, doctors may submerge people with extremely high body temperature in cold water to cool them quickly. This is said to be effective in reducing the temperature of people with heat stroke or extremely high body temperature (hyperthermia), conditions under which antipyretic drugs are deemed unsuitable (Weiner 1980; Axelrod 2000).

Physical methods allow the body to lose heat through conduction, convection, or evaporation. Conduction occurs when heat is exchanged between two objects in contact with one another. Convection occurs when warm air in contact with an object moves away and is replaced by cooler air in a continuous cycle (Ganong 1989). When water evaporates from an object surface heat is lost and the object cools. People who are sponged to treat fever lose heat by all three mechanisms.

Potential benefits and harms of physical and pharmacological methods of cooling

Although the pathophysiology that results in fever are obviously harmful, some experts suggest that fever may have the beneficial effect of enhancing host resistance to infection (Kramer 1991; Roberts 1991; Kluger 1992). Some argue that interventions specifically targeted at resolution of fever may interfere with the beneficial role of fever during illness and consequently adversely affect the outcome of the illness.

Most physical cooling methods are cheap and readily available. Tepid sponging and bathing are widely used by caregivers and doctors to treat children with fever. People believe that these methods are effective and safe (Al‐Eissa 2001; Crocetti 2001). However, opinions vary among experts about the actual benefits and harms of physical methods. The common adverse effects of physical methods include shivering, crying, and discomfort

Sponging with cold water may cause peripheral cooling, but the constriction of the blood vessels can actually cause heat conservation (Mackowiak 1998). The axillary temperature will fall and the rectal temperature will rise. Tepid sponging has also been reported to cause chills, shivering, constriction of the skin blood vessels, and to conserve heat within the body (Mackowiak 1998; Lenhardt 1999). One of the reasons given for treating fever is to minimize the increased breakdown of the body's energy store, which commonly occurs with fever. However, physical cooling methods have been found to potentially increase the breakdown of body energy and induces shivering (Mackowiak 1998). Loss of consciousness in people sponged with alcohol is a rare adverse event that has been associated with this method of treating fever (Moss 1970; Arditi 1987).

Adverse events of pharmacological cooling methods are less well known. One trial suggests that treatment with antipyretic drugs could increase mortality in severe infections, prolong viral shedding, and impair antibody response to viral infection (Shann 1995).

Effectiveness of physical and pharmacological methods of cooling

It is unclear whether physical methods are beneficial, especially when compared with commonly used antipyretic drugs (Choonara 1992). In fact, some researchers have reported that physical methods are less effective than antipyretic drugs at reducing body temperature during fever, and also cause more discomfort (Styrt 1990; Agbolosu 1997). However, most caregivers and many clinicians still believe that treatment of fever will relieve symptoms and prevent harmful effects such as febrile convulsions (Stuijvenberg 1999).

Given that physical methods are widely recommended for treating children with fever, we sought to examine reliable research evidence around various physical methods for treating fever in children, and to compare these methods with commonly used antipyretic drugs. This review excludes children with a prior history of febrile convulsions, as this is dealt with elsewhere (Offringa 2003).

Objectives

To evaluate the benefits and harms of physical cooling methods used for managing fever in children.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomized and quasi‐randomized controlled trials.

Types of participants

Children aged 1 month to 15 years with fever of presumed infectious origin. Fever is defined as temperature of 37.5 °C or more (axillary), or 38.0 °C or more (core body temperature).

We included trials of general paediatric populations, and excluded studies that specifically targeted children at risk of febrile convulsions, that is, with a history of a recent febrile convulsion.

Types of interventions

Intervention

Physical methods (sponging, bathing, or fanning).

Control

Drug placebo or no treatment.

We have stratified the studies into those where no antipyretic drugs are given and those where all participants receive antipyretic drugs.

Types of outcome measures

Primary

Time to becoming afebrile, as defined by the authors.

Secondary

Resolution of fever by the first, second, and sixth hour of starting treatment.

Rate of temperature fall between 30 minutes and 6 hours of treatment (expressed in °C per hour).

Resolution of associated symptoms (discomfort, shivering, chills, anorexia, vomiting, irritability, headache, muscle pain) resolved within six hours of starting treatment.

Febrile convulsions.

Adverse events.

Caregivers dissatisfaction with treatment regimen.

Search methods for identification of studies

We have attempted to identify all relevant studies regardless of language or publication status (published, unpublished, in press, and in progress).

We selected the following topic search terms for searching all the trial registers and databases: fever; pyrexia; child; sponging; bathing; fanning; physical; cooling; and antipyretic.

We searched the Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group's trials register for relevant trials up to October 2005. Full details of the Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group's methods and the journals handsearched are published in The Cochrane Library in the section on Collaborative Review Groups.

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), published on The Cochrane Library (Issue 3, 2005).

We searched the following electronic databases in combination with the search strategy developed by The Cochrane Collaboration (Clarke 2003); MEDLINE (1966 to October 2005); EMBASE (1980 to October 2005); LILACS (www.bireme.br; accessed October 2005); CINAHL (1982 to October 2005); and Science Citation Index (1981 to October 2005).

We also checked the reference lists of other reviews and all the trials identified by the above methods.

We also contacted researchers in paediatric infectious diseases to check the completeness of the search strategy and supply information on any unpublished and ongoing trials not yet identified by the reviewers.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

We independently applied the inclusion criteria for this review to the potentially relevant trials identified by the search strategy. Where there was any doubt, we consulted a third person within the Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group. We included only those trials that met all inclusion criteria.

Data extraction and management

One reviewer extracted data using a standard form and the second reviewer checked the data for accuracy. We wrote to the trial authors for additional data or clarification of analyses and outcomes where required.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

One reviewer (Martin Meremikwu) assessed the risk of bias methodological quality) of included trials and the second reviewer (Angela Oyo‐Ita) checked this. We applied the following criteria in assessing the methodological quality.

1. Generation of allocation sequence

Considered adequate if random allocation of participants was by a computer‐generated list or table of random numbers. We considered studies that used alternate allocation or other quasi‐randomization methods to be prone to increased risk of bias; we only included them if the baseline characteristics of the intervention and control groups were comparable.

2. Allocation concealment

Considered adequate if allocation to treatment or control groups were concealed in envelopes that were serially numbered, sealed, and opaque; otherwise, we considered the allocation concealment to be inadequate.

3. Inclusion of all randomized participants in analysis

Considered adequate if at least 90% of all randomized participants were included in the analysis of outcomes.

Where there were doubts about methodological quality we reached a consensus through debate. We considered the methodological quality to be unclear if the study authors failed to categorically state what was done regarding each criterion.

Data synthesis

We entered data into Review Manager 4.1. We calculated the risk ratio with 95% confidence intervals for binary data and mean difference for continuous data. We assessed heterogeneity using the chi‐squared test at the 5% level of statistical significance and by visually examining the forest plot. If we observed heterogeneity, but still considered it appropriate to combine trials, we used a random effects model. We planned to do a subgroup analysis of febrile convulsion for children aged six months to six years since the risk of febrile convulsion is known to be particularly high in this age group (Behrmann 2000).

Results

Description of studies

We found 21 potentially relevant publications. Seven trials involving a total of 467 children met the inclusion criteria (Steele 1970; Hunter 1973; Newman 1985; Friedman 1990; Kinmonth 1992; Mahar 1994; Sharber 1997). We have documented the reasons for excluding the other 14 studies (see 'Characteristics of excluded studies').

Two trials compared tepid sponging, antipyretic drugs, and placebo (Steele 1970; Hunter 1973). Hunter 1973 stopped recruitment into the placebo arm and did not present results. Six trials compared sponging plus paracetamol with paracetamol alone (Steele 1970; Hunter 1973; Friedman 1990; Kinmonth 1992; Mahar 1994; Sharber 1997). Newman 1985 compared children who received an antipyretic drug (either paracetamol or aspirin) alone with an antipyretic drug combined with tepid sponging.

One trial used warm water (from 32.0 to 41.9 °C) for sponging (Kinmonth 1992), while the other six used tepid water (ranging from 29.0 to 33.3 °C). Steele 1970 also compared sponging with ice water or an equal mixture of 70% alcohol and water. The outcomes reported for the included trials were rate of temperature fall between 30 minutes and 6 hours of treatment (Mahar 1994); resolution of fever by the first hour (Steele 1970; Mahar 1994); resolution of fever by the second hour (Steele 1970); and the occurrence of any adverse events (Steele 1970; Mahar 1994; Sharber 1997).

Trial reports did not provide data on some of the outcomes specified in the review protocol, namely fever clearance time, febrile convulsions, and the attitude of caregivers.

Risk of bias in included studies

Two studies reported adequate methods for generating the random sequence. Sharber 1997 used shuffled cards and Friedman 1990 used a table of random numbers. Four studies did not specify how the allocation sequence was generated (Steele 1970; Hunter 1973; Mahar 1994). Four trials reported adequate allocation concealment (using sealed envelopes); the methods used were unclear in two studies (Hunter 1973; Friedman 1990); and the remaining study used alternate allocation (Newman 1985).

Hunter 1973 provided specific information on losses to follow up or withdrawals, while the other trials did not. However, this study had a number of other methodological problems, namely, the trialists stopped randomizing participants to the placebo arm because of failure to show significant response, they did not report the outcomes in this group, and they lost 35% of the sponging group to follow up. Newman 1985 reported that seven of 80 participants (8.8%) allocated to the intervention arm were withdrawn because "they began to shiver", and only 73 participants were analysed in this arm.

Effects of interventions

1. Physical methods compared to control (no concomitant antipyretic drug)

a. Resolution of fever by 1 and 2 hours

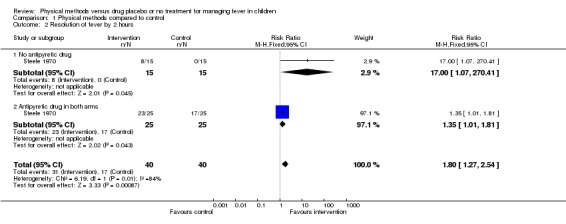

Steele 1970 reported the resolution of fever among a tepid sponging group (n = 15) compared with a drug placebo group (n = 15). At 1 hour there was no obvious difference in the number of participants whose fever resolved between the two groups (2/15 in the tepid sponging group compared with 0/15 in the placebo group). But, by the second hour, fever had resolved in 8 out of the 15 participants in the tepid sponging group, unlike in the placebo group (0/15) (risk ratio (RR) 17.00; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.07 to 270.42). The wide confidence interval reflects the small size of this trial.

b. Adverse events

The proportion with adverse events in the tepid sponging group (5/15) and placebo group (2/15) was not statistically significantly different (RR 2.50; 95% CI 0.57 to 10.93). Adverse events included vasomotor change, shivering, and gross signs of discomfort.

2. Physical methods compared to control (concomitant antipyretic drugs in both arms)

Three trials compared paracetamol plus tepid sponging to paracetamol alone (Steele 1970; Hunter 1973; Mahar 1994; Sharber 1997). They provided results for the following outcomes.

a. Resolution of fever by 1 and 2 hours

Two trials of 125 participants reported more children in the paracetamol plus sponging group than in the paracetamol alone group to have cleared fever by the end of the first hour (RR 11.76; 95% CI 3.39 to 40.79) (Steele 1970; Mahar 1994). Resolution of fever by the second hour was reported by one trial (Steele 1970). More participants in the paracetamol plus sponging group than in the paracetamol alone group were without fever by the second hour (RR 1.35; 95% CI 1.01 to 1.81).

b. Rate of fall in temperature

Mahar 1994 (n = 75) reported the rate of fall in temperature from 15 to 45 minutes after starting treatment. The average drop in temperature was greater in the group that had a physical method combined with paracetamol compared to the paracetamol alone group (0.23 °C per hour; 95% CI 0.08 to 0.38). Hunter 1973 reported little difference in temperature drop between the two groups: 1.6 °C per hour (n = 13) for the physical method plus paracetamol group compared with 1.8 °C per hour (n = 12) for the paracetamol alone group (Appendix 1).

c. Febrile convulsions

One participant in Hunter 1973 was withdrawn due to febrile convulsion (the study group to which this participant belonged was not stated). No other authors reported febrile convulsions in the intervention or control groups.

d. Other adverse events

Data from three trials reported more adverse events (shivering and goose pimples) in the sponging group than in the paracetamol alone group (RR 5.09; 95%; CI 1.56 to 16.60) (Steele 1970; Mahar 1994; Sharber 1997). Mahar 1994 also showed that crying was more frequent among the tepid sponged children (135/245 observations) than among those not sponged (25/280 observations) (RR 6.17; 95% CI 4.18 to 9.12). Seven (9%) of 80 participants initially randomized to the sponging plus antipyretic arm were withdrawn from one trial because of shivering (Newman 1985). No severe adverse events were reported during the trials.

e. Other outcomes

The outcomes beyond what was anticipated in the review protocol are reported in Appendix 1. Hunter 1973 reported the number of children with a fall in temperature of 1.5 °C by 1 hour and 2 hours. The proportion of children with a fall in temperature of 1.5 °C by 1 hour were 2/13 and 2/12 in the physical method plus paracetamol and paracetamol groups respectively (RR 0.9; 95% CI 0.15 to 5.56). The proportion with a fall of 1.5 °C by 2 hours was 11/13 in the physical method plus paracetamol, and 10/12 in the paracetamol group (RR 1.10; 95% CI 0.13 to 9.34).

Friedman 1990 reported the mean temperatures at 60 minutes for paracetamol plus sponging (n = 28) and paracetamol alone (n = 26) groups to be 101.5 °F (38.61 °C) and 102.2 °F (39.00 °C) respectively. Kinmonth 1992 showed that mean time below 37.2 °C was 164 minutes for the paracetamol plus warm sponging group (n = 13) and 129 minutes for the paracetamol group (n = 13). In both cases the mean differences could not be determined since the authors did not provide the standard deviation. Kinmonth 1992 also reported that median acceptability score by parents was 1 (happy) for the paracetamol plus warm sponging group and 2 (very happy) for the paracetamol group.

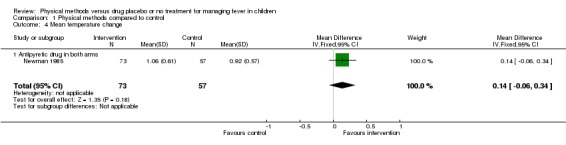

Newman 1985 reported no statistically significant difference in the mean fall in temperature at one hour after commencing treatment in children that received antipyretic drugs alone (n = 73) and those that received both tepid sponging and antipyretic drugs (n = 57) (mean difference0.14 °C; 95% CI ‐0.06 to 0.34).

3. Iced water compared to tepid sponging (concomitant antipyretic drugs in both arms)

Steele 1970 compared iced water sponging plus paracetamol with tepid sponging plus paracetamol.

a. Resolution of fever by 1 and 2 hours

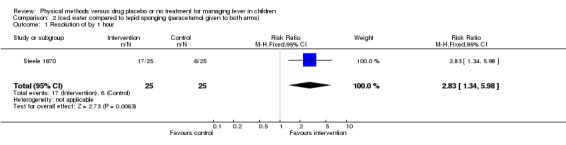

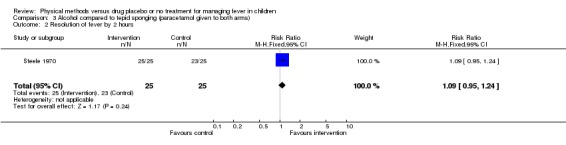

The number with participants whose fever resolved by the first hour was higher in the iced water group (17/25) than the tepid sponged group (6/26) (RR 2.83; 95% CI 1.34 to 5.98). Both groups were afebrile by the second hour (iced water 25/25; tepid sponging 23/25).

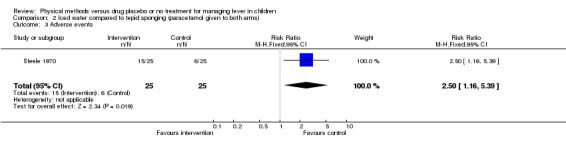

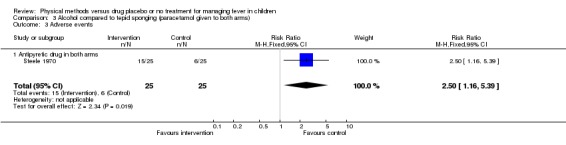

b. Adverse events

The proportion of participants with adverse events was statistically significantly higher in the iced water group (15/25) than the tepid sponging group (6/25) (RR 2.50; 95% CI 1.16 to 5.39).

4. Alcohol compared to tepid sponging (concomitant antipyretic drugs in both arms)

Steele 1970 compared alcohol sponging plus paracetamol with tepid sponging plus paracetamol.

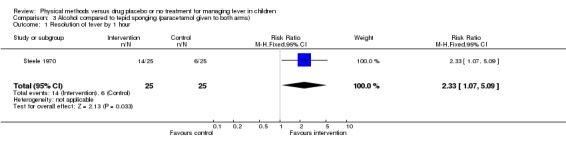

a. Resolution of fever at 1 and 2 hours

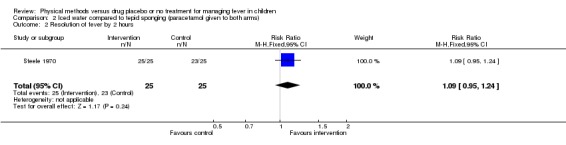

The number of participants whose fever resolved fever by the first hour was higher in the alcohol group (14/25) than the tepid sponging group (6/25) (RR 2.33; 95% CI 1.07 to 5.09). The number whose fever resolved by the second hour did not differ significantly between the alcohol (25/25) and tepid sponging (23/25) groups (RR 1.09; 95% CI 0.97 to 1.22).

b. Adverse events

The proportion of participants with adverse events was higher in the alcohol group (15/25) than in the tepid sponging group (6/25) (RR 2.50; 95% CI 1.16 to 5.39).

Discussion

This review included only seven small trials, all with methodological limitations. Although allocation concealment was adequate in three trials, the method used to generate the sequence of allocation was clear in only one of these. The largest trial used a less robust quasi‐randomization technique and resulted in a marked difference in the number of participants allocated to the two treatment arms (80 versus 57); this suggests that randomization failed and any conclusions must be drawn cautiously. Only two trials provided details regarding drop outs or withdrawals, which makes it impossible to rule out attrition bias. One trial had very high dropout rates and post‐randomization exclusions. Given these methodological limitations, the results should be interpreted with caution.

We found insufficient data to demonstrate or refute that physical methods alone are effective in normalizing temperature. However, tepid sponging with paracetamol achieves better antipyretic effects than the drug alone. The outcomes assessed by the available trials varied widely and so pooling of data from different reports was not possible. In addition, the data available are insufficient to explore the effects of water temperature on the cooling effect. None of the trials assessed cooling blankets or fanning.

Authors' conclusions

There is limited evidence from three small trials that sponging has an antipyretic effect. This was observed in children who had already been given paracetamol. The intervention also caused shivering and goose pimples.

Physical methods are widely used in treating fever in children, but only a few small trials have evaluated the effects. The small size of these trials makes it difficult to reach conclusions on the possible benefits and harms associated with this common practice. We suggest a study with the following three arms is required: a defined physical method, such as sponging; paracetamol alone; and paracetamol plus sponging. This study should be sufficiently powered to detect clinically important differences in the proportion afebrile by one hour. For example, 30% could be considered a clinically important difference. It would also be helpful to compare warm sponging with tepid sponging, with paracetamol in both arms, in a study with a randomized design. Outcome measures relevant to the caregivers should be explored in qualitative preliminary studies to identify sensible outcomes for a trial.

Acknowledgements

A grant from the Cochrane Child Health Field made this review possible.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Physical method combined with paracetamol compared to paracetamol

| Trial | Physical method | Outcome | Results | |

| Physical method + paracetamol | Paracetamol | |||

| Hunter 1973 | Tepid sponge | Number with a temperature fall of 1.5 °C by 1 hour | 2 (n = 13) | 2 (n = 12); risk ratio 0.92 (95% confidence interval 0.15 to 5.56) |

| Hunter 1973 | Tepid sponge | Number with a temperature fall of 1.5 °C by 2 hours | 11 (n = 13) | 10 (n = 12); risk ratio 1.02 (95% confidence interval 0.72 to 1.43) |

| Hunter 1973 | Tepid sponge | Mean rate of fall in temperature (0.5 to 2 hours) | 1.6 °C | 1.8 °C |

| Steele 1970 | Alcohol | Number with poor comfort score | 15 (n = 25) | 2 (n = 25) |

| Steele 1970 | Ice water | Number with poor comfort score | 15 (n = 25) | 2 (n = 25) |

| Friedman 1990 | Tepid sponge | Mean temperature at 30 minutes after initiation of therapy | 102.8 °F (standard deviation not provided) | 103.0 °F (standard deviation not provided) |

| Friedman 1990 | Tepid sponge | Mean temperature at 60 minutes after initiation of therapy | 101.5 °F | 102.2 °F |

| Kinmonth 1992 | Warm sponge | Mean time below 37.2 °C | 164.0 minutes | 129 minutes |

| Kinmonth 1992 | Warm sponge | Median acceptibility score (by parents at the end of 4 hour profile) | 2 = happy | 1 = very happy |

Data and analyses

Comparison 1.

Physical methods compared to control

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Resolution of fever by 1 hour | 2 | 155 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 10.58 [3.39, 33.05] |

| 1.1 No antipyretic drug | 1 | 30 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 5.0 [0.26, 96.13] |

| 1.2 Antipyretic drug in both arms | 2 | 125 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 11.76 [3.39, 40.79] |

| 2 Resolution of fever by 2 hours | 1 | 80 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.8 [1.27, 2.54] |

| 2.1 No antipyretic drug | 1 | 30 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 17.0 [1.07, 270.41] |

| 2.2 Antipyretic drug in both arms | 1 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.35 [1.01, 1.81] |

| 3 Adverse events | 3 | 175 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.05 [1.61, 10.15] |

| 3.1 No antipyretic drug | 1 | 30 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.5 [0.57, 10.93] |

| 3.2 Antipyretic drug in both arms | 3 | 145 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 5.09 [1.56, 16.60] |

| 4 Mean temperature change | 1 | 130 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.14 [‐0.06, 0.34] |

| 4.1 Antipyretic drug in both arms | 1 | 130 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.14 [‐0.06, 0.34] |

Analysis 1.1.

Comparison 1 Physical methods compared to control, Outcome 1 Resolution of fever by 1 hour.

Analysis 1.2.

Comparison 1 Physical methods compared to control, Outcome 2 Resolution of fever by 2 hours.

Analysis 1.3.

Comparison 1 Physical methods compared to control, Outcome 3 Adverse events.

Analysis 1.4.

Comparison 1 Physical methods compared to control, Outcome 4 Mean temperature change.

Comparison 2.

Iced water compared to tepid sponging (paracetamol given to both arms)

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Resolution of by 1 hour | 1 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.83 [1.34, 5.98] |

| 2 Resolution of fever by 2 hours | 1 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.09 [0.95, 1.24] |

| 3 Adverse events | 1 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.5 [1.16, 5.39] |

Analysis 2.1.

Comparison 2 Iced water compared to tepid sponging (paracetamol given to both arms), Outcome 1 Resolution of by 1 hour.

Analysis 2.2.

Comparison 2 Iced water compared to tepid sponging (paracetamol given to both arms), Outcome 2 Resolution of fever by 2 hours.

Analysis 2.3.

Comparison 2 Iced water compared to tepid sponging (paracetamol given to both arms), Outcome 3 Adverse events.

Comparison 3.

Alcohol compared to tepid sponging (paracetamol given to both arms)

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Resolution of fever by 1 hour | 1 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.33 [1.07, 5.09] |

| 2 Resolution of fever by 2 hours | 1 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.09 [0.95, 1.24] |

| 3 Adverse events | 1 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.5 [1.16, 5.39] |

| 3.1 Antipyretic drug in both arms | 1 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.5 [1.16, 5.39] |

Analysis 3.1.

Comparison 3 Alcohol compared to tepid sponging (paracetamol given to both arms), Outcome 1 Resolution of fever by 1 hour.

Analysis 3.2.

Comparison 3 Alcohol compared to tepid sponging (paracetamol given to both arms), Outcome 2 Resolution of fever by 2 hours.

Analysis 3.3.

Comparison 3 Alcohol compared to tepid sponging (paracetamol given to both arms), Outcome 3 Adverse events.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 18 February 2009 | Amended | Title changed from Physical methods for treating fever in children to Physical methods versus drug placebo or no treatment for managing fever in children, in order to reflect the content of the review. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 3, 2001 Review first published: Issue 2, 2003

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 5 October 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format with minor editing. |

| 7 October 2005 | New search has been performed | New studies sought but none found. |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | Generation of allocation sequence: table of random numbers. Allocation concealment: unclear. Blinding: not feasible. Length of follow up: 1 hour. |

|

| Participants | 73 children between 6 weeks and 4 years with rectal temperature 102 ° F or higher. Exclusion criteria: antipyretic within 4 hours; antibiotics within past 72 hours; history of febrile convulsion or allergy to acetaminophen. |

|

| Interventions | 1. Acetaminophen alone (n = 26). 2. Tepid sponging alone (n = 19). 3. Acetaminophen plus tepid sponging (n = 28). | |

| Outcomes | Mean temperature at 30 and 60 minutes after initiation of therapy. | |

| Notes | Study location: St. Louis, Missouri, USA. | |

| Methods | Generation of allocation sequence: randomized (method not stated) Allocation concealment: unclear Blinding: not feasible Length of follow up: 4 hours |

|

| Participants | 67 children between 6 months and 5 years with temperature greater than 39.5 °C (39 °C orally) Exclusion criteria: gastroenteritis or dehydration; antibiotics considered necessary |

|

| Interventions | 1. Placebo (n = 6) 2. Aspirin alone 5 to 12 mg/kg (n = 12) 3. Paracetamol alone 5 to 10 mg/kg (n = 12) 4. Paracetamol 5 to 12 mg/kg plus sponging (n = 13) 5. Tepid sponging alone (n = 14) | |

| Outcomes | Percentage of participants responding during treatment (defined as a fall in temperature of 1.5 °C) Rate of fall in temperature after treatment (did not provide standard deviation) |

|

| Notes | Study location: Melbourne, Australia 9 participants excluded for failing to achieve a response or complete 4 hour period of observation Placebo group withdrawn because 6 participants failed to show significant response 35% of tepid sponging group lost to follow up |

|

| Methods | Generation of allocation sequence: randomized (method not stated) Allocation concealment: unclear Blinding: parallel, open trial Length of follow up: 4 hours |

|

| Participants | 52 children 3 months to 5 years; axillary temperature 37.8 to 39.9 °C Exclusion criteria: received antipyretic 4 hours prior to study entry; temperature >40 °C; serious concomitant disease; history of febrile seizures; contraindication to paracetamol |

|

| Interventions | 1. Paracetamol alone (120 mg for children 1 year or less and 240 mg for those more than 1 year, as single dose) (n = 13) 2. Unwrapping alone (n = 13) 3. Sponging: with warm water (mean temperature 37.1 °C) (n = 13) 4. Paracetamol and warm sponging (n = 13) | |

| Outcomes | Mean change in temperature over time Acceptability of treatment to child and parents Mean time to temperature below 37.2 °C |

|

| Notes | Study location: Southampton, England, UK No loss to follow up or withdrawals recorded |

|

| Methods | Generation of allocation sequence: randomized using numbered envelopes Allocation concealment: adequate Blinding: parallel, open trial Length of follow up: 2 hours |

|

| Participants | 75 children aged 6 months to 5 years with a rectal temperature of 38.5 °C or more and a viral infection Exclusion criteria: received antipyretic 4 hours prior to study entry; requiring admission |

|

| Interventions | 1. Paracetamol alone 10 to 15 mg/kg (n = 40) 2. Paracetamol and sponging (n = 35). Sponging was with tepid water of 29 to 30 °C until temperature </= 38.5 °C, ambient temperature 29.4 °C, humidity 78.9% | |

| Outcomes | Mean rate of temperature fall Proportion of children in each group whose temperature had not fallen to <38.5 °C at each observation time Time to maximum rate of fall in temperature Recurrence of fever Adverse events |

|

| Notes | Study location: Bangkok, Thailand No losses to follow up or withdrawals recorded All the children were naked and placed in a room ventilated by fixed wall fans |

|

| Methods | Generation of allocation sequence: quasi‐randomized, using odd or even admission number Allocation concealment: inadequate Blinding: not feasible 8.8% exclusion post‐randomization |

|

| Participants | 137 children aged 0.25 to 2.0 years, rectal temperature 39 °C or higher. Participants were admitted even if they had recently taken aspirin or paracetamol | |

| Interventions | 1. Paracetamol or aspirin alone (mixed group) (n = 57) 2. Paracetamol or aspirin plus tepid sponging (n = 80; 7 withdrawn) Children who had no antipyretic within 4 hours or had none at all received paracetamol or acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin) at doses of 5 to 10 mg/kg |

|

| Outcomes | Mean temperature changes | |

| Notes | Study location: Toronto, Canada | |

| Methods | Generation of allocation sequence: randomized using numbered envelopes Allocation concealment: adequate Blinding: parallel, open trial Length of follow up: 2 hours |

|

| Participants | 20 children aged 5 to 68 months with a rectal temperature of 38.9 °C or more with viral and bacterial infections Exclusion criteria: received antipyretic 4 hours prior to study entry; illness requring immediate antibiotics; hyperthermia; communication barrier |

|

| Interventions | 1. Paracetamol alone (15 mg/kg as single dose) (n = 10) 2. Paracetamol and sponging with tepid water (n = 10) Mean temperature of water of 33 °C for 15 minutes Ambient temperature 25.81 °C. Humidity 38.4% |

|

| Outcomes | Mean temperature over time Assessment of discomfort Adverse events |

|

| Notes | Study location: Tucson, Arizona, USA No losses to follow up or withdrawals recorded |

|

| Methods | Generation of allocation sequence: randomized (method not specified but used serially numbered envelopes) Allocation concealment: adequate Blinding: parallel, placebo‐controlled trial Length of follow up: 2 hours |

|

| Participants | 130 children aged 6 months to 5 years, rectal temperature 39.4 °C or more, lasting more than 3 days, of viral and bacterial origin Exclusion criteria: received antipyretic 4 hours before study entry |

|

| Interventions | 1. Placebo (n = 15) 2. Tepid water sponging plus placebo (n = 15) 3. Paracetamol alone (n = 25) 4. Tepid sponging plus paracetamol (n = 25) 5. Iced water plus paracetamol (n = 25) 6. Alcohol in water plus paracetamol (n = 25) Paracetamol dose: 80 mg (6 to 18 months), 160 mg (18 to 30 months), 240 mg (30 to 48 months) and 320 mg (48 to 60 months) |

|

| Outcomes | Percentage with temperature </= 38.3 °C at 1 and 2 hours; percentage with comfort rated as good, fair, or poor | |

| Notes | Study location: Honolulu, Hawaii No losses to follow up or withdrawals recorded |

|

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Agbolosu 1997 | Physical method not compared with placebo or no intervention. |

| Aksoylar 1997 | Physical method not compared with placebo or no intervention. |

| Brandts 1997 | Physical method not compared with placebo or no intervention. |

| Caruso 1992 | Adult participants included. |

| Eskerud 1991 | Not a randomized controlled trial. |

| Fruthaler 1964 | Not a randomized controlled trial. |

| Kramer 1991 | Physical method not compared with placebo or no intervention. |

| Lell 2001 | Physical method not compared with placebo or no intervention. |

| Lenhardt 1999 | Participants were adults. |

| Mackintosh 1970 | Drug combined with anticonvulsant (phenobarbitone). |

| Purssell 2000 | A review (not a systematic review) and not a randomized contolled trial. |

| Senz 1958 | Not a randomized controlled trial. |

| Steele 1972 | Does not include a physical method arm. |

| Stuijvenberg 1999 | Not a randomized controlled trial. |

Contributions of authors

Both reviewers developed the protocol, performed the literature search, and extracted data. Martin Meremikwu analysed the data and drafted the full review.

Sources of support

Internal sources

University of Calabar, Calabar, Nigeria.

External sources

Cochrane Child Health Field, Canada.

Department for International Development (DFID), UK.

Declarations of interest

We certify that we have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with a direct financial interest in the subject matter of the review (eg employment, consultancy, stock ownership, honoraria, expert testimony).

Notes

The protocol for this review is 'Drugs and other methods for managing fever in children'.

Unchanged

References

References to studies included in this review

- Friedman AD, Barton LL. Efficacy of sponging versus acetaminophen for reduction of fever. Pediatric Emergency Care 1990;6(1):6‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter J. Study of antipyretic therapy in current use. Archives of Diseases in Childhood 1973;48:313‐5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinmonth A, Fulton Y, Campbell MJ. Management of feverish children at home. BMJ 1992;305:1134‐6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahar AF, Allen SJ, Milligan P, Suthumnirund S, Chotpitayasunondh T, Sabchareon A, et al. Tepid sponging to reduce temperature in febrile children in a tropical climate. Clinical Pediatrics 1994;4:227‐31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman J. Evaluation of sponging to reduce body temperature in febrile children. Canadian Medical Association Journal 1985;132:641‐2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharber J. The efficacy of tepid sponge bathing to reduce fever in young children. American Journal of Emergency Medicine 1997;15(2):188‐92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele RW, Tanaka PT, Lara RP, Bass JW. Evaluation of sponging and of oral antipyretic therapy to reduce fever. Journal of Pediatrics 1970;77(5):824‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

- Agbolosu NB, Cuevas LE, Milligan P, Broadhead RL, Brewster D, Graham SM. Efficacy of tepid sponging versus paracetamol in reducing temperature in febrile children. Annals of Tropical Paediatrics 1997;17:283‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aksoylar S, Aksit S, Caglayan S, Yaprak I, Bakiler R, Cetin F. Evaluation of sponging and antipyretic medication to reduce body temperature in febrile children. Acta Paediatrica Japonica 1997;39:215‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandts CH, Ndjave M, Graninger W, Kremsner PG. Effects of paracetamol on parasite clearance time in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Lancet 1997;350:704‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caruso CC, Hadley BJ, Shukla R, Frame P, Khoury J. Cooling effects and comfort of four cooling blanket temperatures in humans with fever. Nursing Research 1992;41(2):68‐72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eskerud JR, Hoftvedt BO, Laerum E. Fever: management and self‐medication. Results from a Norwegian population study. Family Practice 1991;8(2):148‐53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fruthaler GJ, Tilden T. Management of hyperpyrexia in children. Postgraduate Medicine 1964;35(6):643‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer MS, Naimark LE, Roberts‐Brauer R, McDougall A, Leduc DG. Risk and benefits of paracetamol antipyresis in young children with fever of presumed viral origin. Lancet 1991;337:591‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lell B, Sovric M, Schmid D, Luckner D, Herbich K, Long YH, et al. Effects of antipyretic drugs in children with malaria. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2001;32:838‐41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenhardt R, Negishi C, Sessler DI, Vuong K, Bastanmehr H, Kim J, et al. The effect of physical treatment on induced fever in humans. American Journal of Medicine 1999;106:550‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackintosh TF. Studies on prophylactic treatment of febrile convulsions in children: is it feasible to inhibit attacks by giving drugs at the first sign of fever or infexction?. Clinical Pediatrics 1970;9(5):283‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purssell E. Physical treatment of fever. Archives of Disease in Childhood 2000;82:238‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senz EH, Goldfarb DL. Coma in a child following use of isopropyl alcohol in sponging. Journal of Pediatrics 1958;53:322‐3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele RW, Young FSH, Bass JW, Shirkey HC. Oral antipyretic therapy. American Journal of Diseases of Children 1972;123:204‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuijvenberg M, Vos S, Tjiang GCH, Steyerberg EW, Derksen‐Lubsen G, Moll HA. Parents' fear regarding fever and febrile seizures. Acta Paediatrica 1999;88:618‐22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

- Al‐Eissa YA, Al‐Zaben AA, Al‐Wakeel AS, Al‐Alola SA, Al‐Shaalan MA, Al‐Amir AA, et al. Physician's perception of fever in children. Facts and myths. Saudi Medical Journal 2001;22(2):124‐8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arditi M, Killner MS. Coma following the use of rubbing alcohol for fever control. American Journal of Diseases of Children 1987;141:237‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axelrod P. External cooling in the management of fever. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2000;31 Suppl 5:224‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrmann MD, Kliegman RM, Jenson HB. Nelson textbook of paediatrics. 16th Edition. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Choonara I, Nunn AJ, Barker C. Drugs for childhood fever (Letter). Lancet 1992;339:69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke M, Oxman AD, editors. Optimal search strategy. Cochrane Reviewers' Handbook 4.1.6 [updated January 2003]; Appendix 5c. In: The Cochrane Library [database on disk and CDROM]. The Cochrane Collaboration. Oxford: Update Software; 2003, issue 2.

- Crocetti M, Moghbeli N, Serwint J. Fever phobia revisited: have parental misconceptions about fever changed in 20 years. Pediatrics 2001;107(6):1241‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganong WF. Review of medical physiology. 14th Edition. Englewood Cliffs (New Jersey): Prentice‐Hall, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Kluger MJ. Drugs for childhood fever (Letter). Lancet 1992;339:70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackowiak PA, Plaisance KI. Benefits and risk of antipyretic therapy. Annals New York Academy of Sciences 1998;856:214‐23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss MH. Alcohol‐induced hypoglycaemia and coma caused by alcohol sponging. Pediatrics 1970;46:445‐7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Offringa M, Newton R. Prophylactic drug management for febrile convulsions in children (Protocol for a Cochrane review). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2003, Issue 2. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts NJ Jr. Impact of temperature elevation on immunologic defenses. Reviews of Infectious Diseases 1991;13:462‐72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shann F. Antipyretics in severe sepsis (Comment). Lancet 1995;345(8946):338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Styrt B, Sugarman B. Antipyresis and fever. Archives of Diseases in Medicine 1990;150:1589‐97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verity CM, Butler NR, Golding J. Febrile convulsions in a national cohort followed up from birth. 1. Prevalence and recurrence in the first five years of life. British Medical Journal 1985;323:1111‐4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner JS, Khogali M. A physiological body‐cooling unit for treatment or heat stroke. Lancet 1980;1(8167):507‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]