Abstract

Background

Intermittent preventive treatment is recommended for pregnant women living in malaria endemic countries due to benefits for both mother and baby. However, the impact may not be the same in HIV‐positive pregnant women, as HIV infection impairs a woman's immunity.

Objectives

To compare intermittent preventive treatment regimens for malaria in HIV‐positive pregnant women living in malaria‐endemic areas.

Search methods

In June 2011, we searched the Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group Specialized Register, CENTRAL, MEDLINE; EMBASE; LILACS, the metaRegister of Controlled Trials (mRCT), reference lists and conference abstracts. We also contacted researchers and organizations for information on relevant trials.

Selection criteria

Randomized controlled trials comparing different intermittent preventive treatment regimens for preventing malaria in HIV‐positive pregnant women in malaria‐endemic areas.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors extracted data and assessed risk bias. Dichotomous variables were combined using risk ratios (RR) and mean differences (MD) for continuous outcomes, both with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Main results

Two randomized trials were included, enrolling 722 HIV‐positive pregnant women from Malawi and Zambia. Both compared monthly regimens of sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine (SP) to the standard 2‐dose regimen given in the second and third trimesters.

In women in their first or second pregnancy, monthly SP may reduce both maternal parasitaemia (two trials, 463 participants, RR 0.25, 95% CI 0.14 to 0.43, low quality evidence), and placental parasitaemia at delivery (two trials, 459 participants, RR 0.38, 95% CI 0.21 to 0.70, low quality evidence). Monthly SP may have a small effect on the prevalence of maternal anaemia at delivery (two trials, 447 participants, RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.72 to 1.20, low quality evidence), and the number of babies born with low birth weight (two trials, 469 participants, RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.52 to 1.23, low quality evidence), but larger trials are necessary to reliably prove or exclude clinically important benefits on these outcomes. There is currently insufficient evidence to make conclusions regarding an effect on neonatal mortality (one study, 253 participants, very low quality evidence).

In women in their third or higher pregnancy, there is insufficient evidence to make any conclusions on the benefits of monthly SP compared to the two dose regimen (one trial, 166 participants, very low quality evidence).

There were no trials that assessed other treatment regimens for intermittent preventive treatment in HIV‐positive pregnant women.

Authors' conclusions

Three or more doses of SP may have some advantages over the standard two doses in HIV‐positive pregnant women, but larger trials would be necessary to confirm an effect on patient important outcomes. However, since SP cannot be administered concurrently with co‐trimoxazole ‐ a drug often recommended for infection prophylaxis in HIV‐positive pregnant women, new drugs and research is needed to address needs of HIV‐positive pregnant women.

16 April 2019

Update pending

Studies awaiting assessment

The CIDG is currently examining a new search conducted in April 2019 for potentially relevant studies. These studies have not yet been incorporated into this Cochrane Review.

Plain language summary

Drugs to prevent malaria in HIV‐positive pregnant women.

Intermittent preventive treatment is the administration of a complete curative dose of an antimalarial medicine at predefined intervals during pregnancy (from the second trimester) regardless of whether or not the pregnant woman has malaria parasites. Intermittent preventive treatment for pregnant women, as is delivered at routine ante‐natal care visits, is a World Health Organization (WHO) recommended policy and has been adopted in the majority of African malaria endemic countries. Since HIV increases the severity of malaria in pregnant women, it is important to evaluate the various drugs and doses needed to prevent malaria in HIV‐positive pregnant women.

This review only identified two trials which compared the impact of using three or more doses of sulphadoxine‐pyrimethamine to using only two doses. Using three or more doses was more effective at preventing the presence of malaria parasites in the placenta and in the peripheral blood of the pregnant woman than using the standard two doses only. Also, children born to HIV‐positive pregnant women who used three or more doses of sulphadoxine‐pyrimethamine weighed more than those born to mothers who used only the standard two doses.

Although more frequent doses of this drug are effective in preventing malaria, HIV‐positive pregnant women with low CD4 count can not use the drug since the current policy requires that they use co‐trimoxazole (Bactrim®) to prevent opportunistic infections. There is need, therefore, to investigate alternative drugs and regimens in preventing malaria in HIV‐positive pregnant women.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Malaria is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality. An estimated 350 and 500 million clinical episodes of malaria occur each year, resulting in over one million deaths. Around 60% of the clinical cases and over 90% of the deaths occur in sub‐Saharan Africa (Korenromp 2005). In addition to acute disease and deaths, malaria also contributes significantly to maternal anaemia during pregnancy and adverse birth outcomes such as spontaneous abortion, stillbirth, premature delivery, and low birthweight. Each year, 25 to 30 million pregnancies in the sub‐Saharan region are at high risk of these adverse consequences of malaria (Chico 2008), with the first pregnancy and, to a lesser extent, the second being at highest risk (Cot 2003).

Sub‐Saharan Africa is also home to an estimated 22.5 million adults and children living with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), with an estimated 1.3 million HIV‐associated deaths in 2009 alone (UNAIDS 2010). Most (55%) of those infected are women of reproductive age (Dabis 2002), and HIV/AIDS is now an ever‐increasing cause of maternal mortality. Although both malaria and HIV/AIDS have distinct risk factors for transmission, the two diseases are associated with poverty and share similar determinants of vulnerability to infection. Many of these determinants are present in sub‐Saharan Africa. Malaria and HIV/AIDS therefore overlap geographically and target the same vulnerable populations in this region. Interaction of HIV and malaria Because of the high prevalence of malaria and HIV infection in the region, co‐infection and interaction between the two diseases are very common (Abu‐Raddad 2006; Froebel 2004; Korenromp 2005a; Kublin 2005). Evidence shows that HIV increases the risk of malaria infection (French 2001), high‐density parasitaemia and clinical malaria (Whitworth 2000), severe malaria (Chalwe 2009) and malaria‐related mortality (Malamba 2007). Reports also suggest that antimalarial treatment failure may be more common in HIV‐infected adults with low CD4‐cell counts compared to those not infected with HIV (Van Geertruyden 2006). Acute malaria episodes are also associated with increased HIV plasma viral load (Kublin 2005), although with no indication that the level of viral load is permanently modified. In pregnant women, HIV infection has also been shown to impair the ability of pregnant women to control infection withPlasmodium falciparum. HIV‐positive pregnant women are more likely to have detectable parasitaemia, higher malaria parasite densities, and develop clinical or placental malaria and malarial anaemia than HIV‐negative pregnant women ( ter Kuile 2004; Perrault 2009). Although previous data suggested that placental malaria could increase the risk of HIV transmission from mother to child (Brahmbhatt 2003), more recent data shows that this may not be the case (Msamanga 2009).Therefore the interaction between the two diseases makes the prevention of malaria in HIV‐positive pregnant women a public health priority.

Description of the intervention

To prevent malaria in pregnancy, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that all women living in sub‐Saharan Africa promptly treat malaria using effective antimalarials, receive intermittent preventive treatment during pregnancy (IPTp) and use long lasting insecticide‐treated nets (LLINs) every night (WHO 2004). IPTp is given once during the second and third trimester of the pregnancy. Chloroquine and sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine (SP) are the safest and most readily available and affordable drugs for the prevention of malaria in pregnancy in most African countries (Garner 2006). However, the efficacy of these drugs is decreasing in many African countries due to drug resistance. Malaria treatment and prevention may not be the same in HIV‐positive pregnant women as is the case with HIV‐negative pregnant women. In western Kenya, the usual IPTp schedule of two doses of SP was suboptimal among HIV‐positive women in their first and second pregnancies. Since then more studies comparing three or more SP doses to the two‐dose policy have been commissioned and carried out in HIV‐positive pregnant women. Also, because of the deteriorating efficacy of SP, other drugs such as amodiaquine (Tagbor 2006) and drug combination regimens (including artemisinin derivatives) are being evaluated to assess their impact in preventing or treating malaria in pregnancy. However, the overall impact of these drugs or drug regimens will have to be assessed for HIV‐positive pregnant women.

Why it is important to do this review

HIV testing is the first step in accessing tailor‐made care for HIV‐positive pregnant women and their unborn babies. Unfortunately, in developing countries only few pregnant women have access to prevention of mother‐to‐child transmission services (WHO 2010a). Nonetheless, gradual but important progress to increase access to HIV‐related care for pregnant women is being made in sub‐Saharan countries (WHO 2010a). For example, most countries have HIV national policies that not only include treatment care and support but also a prevention of mother‐to‐child transmission component. For HIV‐positive pregnant women, this package of care includes access to antiretroviral treatment, co‐trimoxazole prophylaxis, nutritional counselling, and support. Increasing linkages between prevention of mother‐to‐child transmission programmes with other programmes, such as malaria control, has also led to preferential targeting of HIV‐positive pregnant women with insecticide‐treated nets.

The aim of this systematic review is to assess the impact of IPTp in HIV‐positive pregnant women in the context of the currently available health care packages.

Objectives

To compare IPTp regimens for malaria in HIV‐positive pregnant women.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomized controlled trials.

Types of participants

HIV‐positive pregnant women living in regions in which there is stable transmission of P. falciparum.

Types of interventions

Intervention

Sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine: three or more doses (25 mg/kg sulphadoxine and 1.25 mg/kg pyrimethamine) during the second and third trimester.

Other antimalarial drug(s): regimen specific to this population.

Control

Sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine (as above): two doses.

Other antimalarial drug(s): standard regimen.

Types of outcome measures

Primary

Maternal anaemia: measured as maternal haemoglobin levels < 11 g/dL at delivery.

Low birthweight: measured as birthweight < 2.5 kg in singleton.

Secondary

Maternal and neonatal mortality.

Placental malaria: measured by the presence of malaria in the placenta.

Peripheral parasitaemia: measured by the presence of malaria parasites on thick and thin malaria smears.

Birthweight.

Maternal haemoglobin levels.

Maternal viral load: measured as number of HIV‐RNA copies/mL.

Adverse events

Serious adverse events (fatal, life threatening, or those that require hospitalization).

Adverse events leading to discontinuation of intervention.

Other adverse events.

Search methods for identification of studies

We attempted to identify all relevant trials regardless of language or publication status (published, unpublished, in press, and in progress).

Databases

On 28 June 2011, we searched the following databases using the search terms and strategy in Table 6: Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group Specialized Register; Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), published in The Cochrane Library; MEDLINE; EMBASE; and LILACS. We also searched the metaRegister of Controlled Trials (mRCT) using the terms: malaria, HIV, and pregnan*.

1. Detailed search strategies.

| Search set | CIDG SR^ | CENTRAL | MEDLINE^^ | EMBASE^^ | LILACS^^ |

| 1 | malaria | malaria | malaria | malaria | malaria |

| 2 | prevent* | prevent* | prevent* | prevent* | prevent* |

| 3 | prophyla* | prophyla* | prophyla* | prophyla* | prophyla* |

| 4 | chemoprophyla* | chemoprophyla* | chemoprophyla* | chemoprophyla* | chemoprophyla* |

| 5 | intermittent presumptive treatment | intermittent presumptive treatment | intermittent presumptive treatment | intermittent presumptive treatment | intermittent presumptive treatment |

| 6 | intermittent presumptive therapy | intermittent presumptive therapy | intermittent presumptive therapy | intermittent presumptive therapy | intermittent presumptive therapy |

| 7 | intermittent preventive treatment | intermittent preventive treatment | intermittent preventive treatment | intermittent preventive treatment | intermittent preventive treatment |

| 8 | intermittent preventive therapy | intermittent preventive therapy | intermittent preventive therapy | intermittent preventive therapy | intermittent preventive therapy |

| 9 | 2‐8/or | 2‐8/or | 2‐8/or | 2‐8/or | 2‐8/or |

| 10 | 1 and 9 | 1 and 9 | 1 and 9 | 1 and 9 | 1 and 9 |

| 11 | HIV | HIV INFECTIONS | HIV INFECTIONS | HUMAN‐IMMUNODEFICIENCY‐VIRUS‐INFECTION | HIV |

| 12 | AIDS | 10 and 11 | 10 and 11 | ACQUIRED‐IMMUNE‐DEFICIENCY‐SYNDROME | AIDS |

| 13 | 7 or 8 | pregnan* | pregnan* | HUMAN‐IMMUNODEFICIENCY‐VIRUS‐INFECTED‐PATIENT | 11 or 12 |

| 14 | 10 and 13 | 12 and 13 | 12 and 13 | 11 or 12 or 13 | 10 and 13 |

| 15 | pregnan* | ‐ | ‐ | 10 and 14 | pregnan* |

| 16 | 14 and 15 | ‐ | ‐ | pregnan* | 14 and 15 |

| 17 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 15 and 16 | ‐ |

| ^Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group Specialized Register | ^^Search terms used in combination with the search strategy for retrieving trials developed by The Cochrane Collaboration (Lefebvre 2011); upper case: MeSH or EMTREE heading; lower case: free text term |

Conference proceedings

We searched the following conference proceedings for trial information: The Multilateral Initiative on Malaria Pan‐African Conference (Yaoundé 2005, Nairobi 2009); American Society for Tropical Medicine and Hygiene Conference (yearly from 2000 to 2009); and International AIDS Conference (Barcelona, 2002; Bangkok 2004, Toronto 2006, Mexico city 2008 and Vienna 2010); 8th International Conference on Drug Therapy in HIV Infection, Glasgow 2006; 3rd International Aids Society Pathogenesis and Treatment Conference, Rio de Janeiro 2005.

Researchers

We contacted researchers working in malaria and competent authorities in HIV/malaria to ask about relevant ongoing studies or unpublished work.

Organizations

We contacted the following organization for information on ongoing studies: World Health Organization; Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases; Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (June 2010); and European and Developing Countries Clinical Trials Partnership (June 2010).

Reference lists

We checked the reference lists of all identified trials and relevant narrative reviews for other potentially relevant trials.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

The eligibility of the studies were judged independently by two review authors by going through all the abstracts identified in the above searches. For each potentially relevant abstract, a full study report was found and the inclusion criteria applied independently by the review authors using a standard eligibility form. Where disagreements arose, the review authors reached a consensus through discussion. Excluded studies were listed and the reasons for exclusion stated.

Data extraction and management

The review authors independently extracted data from the trial reports using a pre‐tested data extraction form. For dichotomous variables, the review authors extracted data on the total number of participants randomized, number that experienced these outcomes, and the number analysed. For continuous outcomes, data on the total number of participants analysed, arithmetic means, standard deviation (SD), and the number of participants randomized were extracted. Where only standard error (SE) was reported, standard deviation was calculated using the following formula: SD = SE x square root of N.

Data was double‐entered into Review Manager 5.0 for analysis.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The risk of bias was independently assessed by the review authors using six factors: generation of allocation sequence, allocation concealment, blinding, intention‐to‐ treat analysis (incomplete outcome data), selective reporting and presence of other biases. Generatation of the allocation sequence and allocation concealment a judgement of yes, no or unclear to was given to represent a low, high or unclear risk of bias. Blinding was assessed based on which parties (study participant, care provider, or assessor) were blinded to the treatment and control arms of the study. We also assessed whether issues around incomplete outcome data were addressed (intention‐to‐treat analysis), whether there was selective reporting of the results and the presence of other biases in the trials. We intended to explore the presence of reporting biases using funnel plots but were unable to do so due to the nature of the data. Disagreements between the review authors were resolved through discussions.

Dealing with missing data

The impact of missing data on the study results was explored with a sensitivity analysis comparing the results from the analyses of study completers (complete cases) with those from best‐ and worst‐case scenarios.

Data synthesis

Meta‐analyis was conducted in Review Manager 5.0. Occurrence of the specified outcomes was compared between participants that received monthly IPTp using SP and those that received a standard 2‐dose SP. Risk ratios (RR) and mean differences were calculated for dichotomous and continuous variables respectively. For continuous data, where arithmetic means, SDs,or SEs are reported, we compared the means within trials to calculate a mean difference. All results were presented with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Heterogeneity amongst the trials was assessed by visually inspecting the forest plots and using the Chi2 test (with P value < 0.1 representing heterogeneity), and the I2 statistic (I2> 50% considered as substantial heterogeneity).

For dichotomous measures, three analyses were undertaken:

Complete case: participants with missing outcomes were excluded (as report by trial authors), data on only those whose results are known, using as denominator the total number of patients who completed the trial.

Best‐case scenario: all participants in monthly SP with missing were assumed to had good outcomes and all participants in 2–dose SP with missing outcomes were assumed to had poor outcomes

Worst‐case scenario: all participants in monthly‐SP with missing were assumed to had poor outcomes and all participants in 2‐dose SP with missing outcomes were assumed to had good outcomes.

For continuous outcomes, we used complete case analysis.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

As part of the primary analysis, subgroup analysis was conducted based on the number of pregnancies.

Results

Description of studies

Study selection

Two trials were identified as fulfilling the inclusion criteria, one published (Filler 2006) and the other identified through conference abstracts (Hamer 2007); details of these trials are shown in the "Characteristics of included studies" section. One more trial (Parise 1998) was excluded and the details of exclusion are included in the "Characteristics of excluded studies" table.

Trial location

Filler 2006 was conducted in rural Malawi and Hamer 2007 was conducted in an urban locale of Zambia. In both countries, transmission of P. falciparum is considered stable. However, in both countries there is an high level of resistance of P. falciparum to SP (Malenga 2009; Bijl 2000; Mulenga 2006), with both Zambia and Malawi changing to artemisinin combination therapy for malaria treatment in 2002 and 2007, respectively.

Participants

Filler 2006 included 266 HIV‐positive pregnant women in their first or second pregnancies whilst Hamer 2007 included 456 HIV‐positive pregnant women regardless of their gravida status. HIV testing was performed using rapid diagnostic tests in parallel: Filler 2006 used Uni‐Gold (Trinity Biotech) and Determine (Abbott Laboratories); and Hamer 2007 used Determine (Abbott Laboratories) and Capillus (Cambridge Biotech Ltd). Filler 2006 further evaluated discordant results using Hema Strip HIV (Saliva Diagnostic Systems) and Hamer 2007 used Bionor assay (Skien, Norway). A HemoCue machine was used to measure haemoglobin.

Intervention

Both studies compared the impact of monthly SP, with directly observed treatment doses at enrolment and then monthly until delivery to the standard WHO recommendation of 2‐doses of SP, with directly observed treatment doses at enrolment and the other dose in the third trimester. There were no trials that looked at other treatment regimens for IPTp.

Outcomes

Placental malaria was the primary outcome in both studies. Both studies collected information on maternal anaemia, peripheral parasitaemia, placental parasitaemia, maternal haemoglobin, birth weight, low birth weight (LBW), premature births, severe adverse drug reaction and uncomplicated malaria. Placental parasitaemia was defined as the presence of asexual‐stage parasites in thick smears using maternal‐side placental blood. Parasitaemia (in peripheral or cord blood) was defined as the presence of asexual‐stage parasites in thick smears. Newborns weighing <2.5 kg were classified as low birth weight. Women with haemoglobin levels of <11 g/dL were considered anaemic and severe ADRs were defined as erythema multiforme, Stevens‐Johnson syndrome, or toxic epidermal necrolysis. Hamer 2007 included histological evidence of placental malaria documented through examination of placental biopsies. See Table 7 for a summary of outcomes.

2. Trial outcomes.

| Outcome | Trial1 ‐ Filler 2006 | Trial 2 ‐ Hamer 2007 |

| Uncomplicated malaria | x | x |

| Placental malaria (based on histology) | x | |

| Placental parasitaemia | x | x |

| Peripheral parasitaemia | x | x |

| Cord blood parasitaemia | x | x |

| Low birth weight | x | x |

| Birth weight | x | x |

| Maternal anaemia ( in 3rd trimester or at delivery) | x | x |

| Maternal haemoglobin (in 3rd trimester or at delivery) | x | x |

| Pre‐term delivery | x | x |

| Neonatal death | x | |

| Adverse Drug Reactions | x | x |

Results of the search

During the search, 19 published studies were identified. Three potentially eligible studies were identified, of which two met the inclusion criteria and one was excluded.

All the included studies are published in English and were conducted in malaria endemic sub‐Saharan African countries. Not all patients reported in the included studies contributed to this review: one study included HIV‐positive and HIV‐negative pregnant women. Only the HIV‐positive pregnant women were included in the review.

Risk of bias in included studies

Filler 2006 randomly assigned trial participants to the intervention or control arm through permuted blocks of random length. However, it is unclear how allocation concealment was achieved. Neither study participants nor the investigators were blinded to group assignment. Only the laboratory workers, who assessed the primary outcome of placental parasitaemia, were blinded to the women's HIV status and treatment arm. The investigators state that an intention to treat analysis was performed; however, data presented in the trial report were based on the number of participants whose data were available. This trial was stopped at the interim analysis due to significant differences between the two treatment regimens.

For Hamer 2007, trial participants were randomized in blocks of 20 to either the treatment or control arm. Participants were then assigned sequential ID numbers during enrolment corresponding to a sealed package of study drugs. The randomization codes were retained by the study statistician and stored in a locked cabinet at Boston University. The code was broken when data collection was complete and preliminary blinded analyses had been performed. Study subjects, the investigators and the assessors were blinded to the trial arm allocation. Intention to treat analysis was not performed.

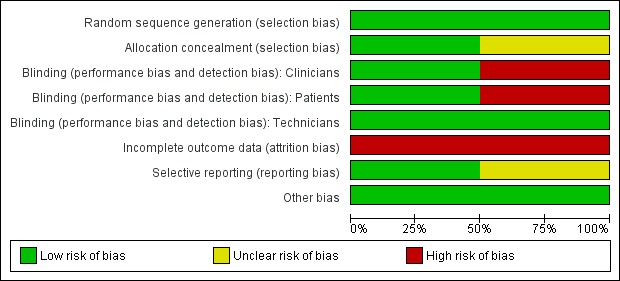

See Figure 1 for a summary of the assessment of risk bias.

1.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Effects of interventions

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Primigravidae and secundigravidae.

| Monthly SP during pregnancy compared to two‐doses for HIV +ve women in their first or second pregnancy | ||||||

| Patient or population: HIV‐positive pregnant women living Settings: Malaria endemic areas Intervention: Monthly sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine (SP) compared to standard 2‐dose SP | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Standard regimen (2 doses) | Monthly regimen (3 or more doses) | |||||

| Maternal parasitaemia (at delivery) | 22 per 100 | 5 per 100 (3 to 10) | RR 0.25 (0.14 to 0.43) | 463 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | |

| Placental parasitaemia (at delivery) | 14 per 100 | 5 per 100 (3 to 10) | RR 0.38 (0.21 to 0.7) | 459 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | |

| Maternal anaemia (Hb < 11 g/dL at delivery) | 66 per 100 | 61 per 100 (47 to 79) | RR 0.93 (0.72 to 1.2) | 447 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | |

| Low birth weight (< 2.5 kg) | 20 per 100 | 16 per 100 (11 to 25) | RR 0.8 (0.52 to 1.23) | 469 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ low1,2 | |

| Neonatal mortality | 8 per 100 | 2 per 100 (1 to 8) | RR 0.29 (0.08 to 1.05) | 253 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,3 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (eg the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Downgraded by 1 under risk of bias: Both studies had a high proportion of missing outcomes which sensitivity analysis indicates could induce clinically relevant bias. 2 Downgraded by 1 for imprecision: Larger trials would be necessary to have full confidence in this result. 3 Downgraded by 2 for imprecision: The number of neonatal deaths was very low, and the single trial underpowered to detect an effect on mortality. In addition, one study which did not separate women into primigravidae, secundigravidae and multigravidae found a trend towards higher neonatal mortality with monthly SP.

Summary of findings 2. Multigravidae (greater than 2 pregnancies).

| Multigravidae (greater than 2 pregnancies) | ||||||

| Patient or population: HIV‐positive pregnant women Settings: Malaria endemic areas Intervention: Monthly sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine (SP) compared to standard 2‐dose SP | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Standard regimen (2 doses) |

Monthly regimen (3 or more doses) |

|||||

| Maternal parasitaemia (at delivery) | 1 per 100 | 1 per 100 (0 to 19) | RR 0.94 (0.06 to 14.75) | 159 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | |

| Placental parasitaemia (at delivery) | 1 per 100 | 3 per 100 (0 to 27) | RR 1.87 (0.17 to 20.23) | 153 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | |

| Maternal anaemia (Hb < 11 g/dL at delivery) | 44 per 100 | 43 per 100 (31 to 62) | RR 0.98 (0.69 to 1.4) | 157 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | |

| Low birth weight (< 2.5 kg) | 9 per 100 | 13 per 100 (5 to 32) | RR 1.41 (0.57 to 3.51) | 155 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | |

| Neonatal mortality | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3,4 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (eg the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Downgraded by 1 under risk of bias: Both studies had a high proportion of missing outcomes which sensitivity analysis indicates could induce clinically relevant bias. 2 Downgraded by 1 for imprecision: This single trial is too small to have any confidence in this result. 3 Downgraded by 1 for indirectness: This trial was conducted in a low malaria transmission setting and maternal and placental parasitaemia were rare in both groups. 4 This trial did not report neonatal mortality separately for mutigravid women.

Monthly SP compared to a standard 2‐dose regimen

The two included trials only compared monthly SP to the recommended 2‐dose SP in the second and third trimesters. There were no trials that assessed other treatment regimens for IPTp in this population. The following results are therefore based on comparison of monthly SP to 2‐dose SP in HIV‐positive pregnant women.

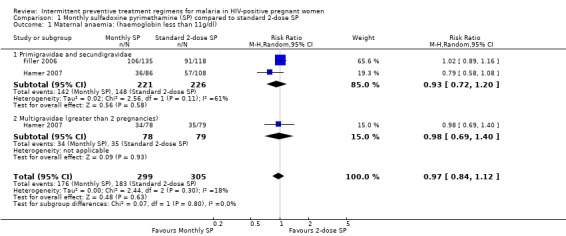

Maternal anaemia

The results from the two RCTs show that there was no statistically significant differences between monthly and 2‐dose SP treatment groups in rates of maternal anaemia (RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.84 to 1.12, 604 participants, two trials) with evidence of no statistically significant heterogeneity (I2 = 18%, Chi2 = 2.44, P = 0.30) (see Analysis 1.1). There were no differences in rates of maternal anaemia in both subgroups (primi‐ / secundigravidae and multigravidae).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Monthly sulfadoxine pyrimethamine (SP) compared to standard 2‐dose SP, Outcome 1 Maternal anaemia: (haemoglobin less than 11g/dl).

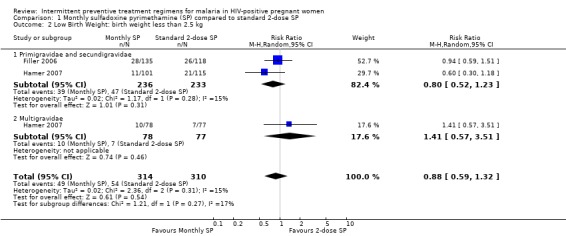

Low birth weight

There was no statistically significant difference between the two treatment groups in rates of low birth weight (RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.59 to 1.32, 624 participants, two trials) with evidence of no statistically significant heterogeneity (I2 = 15%, Chi2 = 2.36, P = 0.31) (see Analysis 1.2). There were no differences in rates of low birth weight among the two subgroups.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Monthly sulfadoxine pyrimethamine (SP) compared to standard 2‐dose SP, Outcome 2 Low Birth Weight: birth weight less than 2.5 kg.

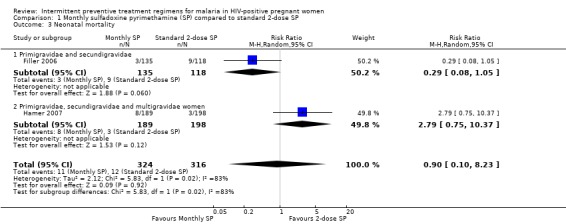

Neonatal mortality

Both trials reported neonatal mortality as an outcome. However, results for Hamer 2007 were not stratified by gravidity. Hamer 2007 reported that children born to mothers on monthly SP were 2.79 (95% CI 0.75 to 10.37, 640 participants, two trials) times more likely to die during the neonatal period than children from mothers on 2‐dose SP (see Analysis 1.3), although the difference was not statistically different. Filler 2006 on the other hand, showed fewer neonatal death in the monthly SP group than the 2‐dose SP group, even though the difference was not statistically different (RR 0.29; 95% CI 0.08 to 1.05).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Monthly sulfadoxine pyrimethamine (SP) compared to standard 2‐dose SP, Outcome 3 Neonatal mortality.

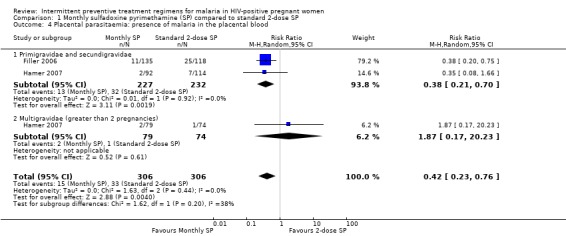

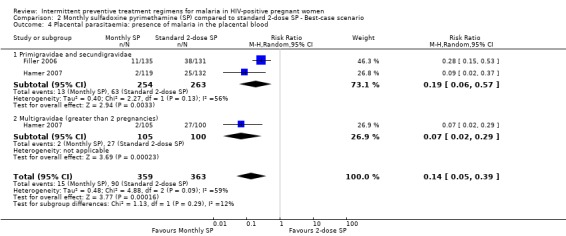

Placental parasitaemia

There was a 58% reduction in risk of placental parasitaemia in women on monthly SP compared to those on 2‐dose SP (RR 0.42; 95% CI 0.23 to 0.76, 612 participants, two trials) with evidence of no statistically significant heterogeneity (I2 = 0%, Chi2 = 1.63, P = 0.44) (see Analysis 1.4). On subgroup analysis, this reduction in risk of placental parasitaemia was only significant among primigravidae and secundigravida (RR 0.38, 95% CI 0.21 to 0.70) and not in multigravidas (RR 1.87, 95% CI 0.17 to 20.23).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Monthly sulfadoxine pyrimethamine (SP) compared to standard 2‐dose SP, Outcome 4 Placental parasitaemia: presence of malaria in the placental blood.

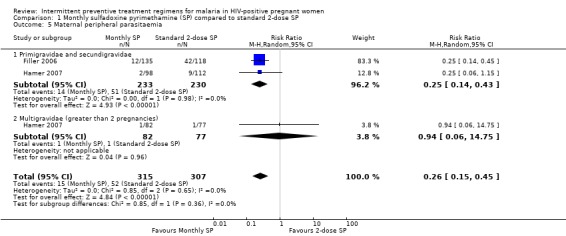

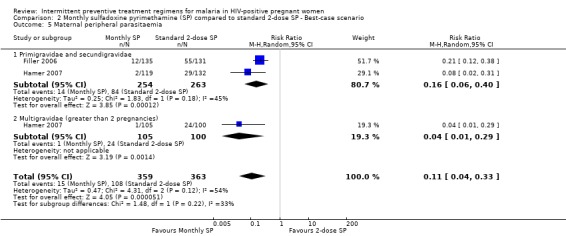

Peripheral parasitaemia

The proportion of women on monthly SP who had peripheral parasitaemia was significantly lower than those on 2‐dose SP (RR 0.26; 95% CI 0.15 to 0.45, 622 participants, two trials) with evidence of no statistical significant heterogeneity (I2 = 0%, Chi2 = 0.85, P = 0.65) (see Analysis 1.5). On subgroup analysis, this reduction in risk of peripheral parasitaemia was only significant among primigravidae and secundigravida (RR 0.25, 95% CI 0.14 to 0.43) and not in multigravidas (RR 0.94; 95% CI 0.06 to 14.75).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Monthly sulfadoxine pyrimethamine (SP) compared to standard 2‐dose SP, Outcome 5 Maternal peripheral parasitaemia.

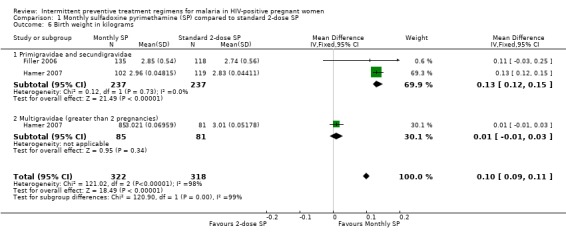

Birth weight

Babies born to women on monthly SP had a higher mean birth weight (weighted mean difference (WMD) 100g; 95% CI 90 g to 110 g, 640 participants, two trials) than babies born to mothers on 2‐dose SP with evidence of substantial statistical significant heterogeneity (I2 = 98%, Chi2 = 121.02, P < 0.00001) (see Analysis 1.6). On subgroup analysis, this means birth weight was only was only significant higher among primigravidae and secundigravida (WMD 130 g; 95% CI 120 g to 150 g) and not in multigravidas (WMD 10 g; 95% CI ‐10 g to 30 g).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Monthly sulfadoxine pyrimethamine (SP) compared to standard 2‐dose SP, Outcome 6 Birth weight in kilograms.

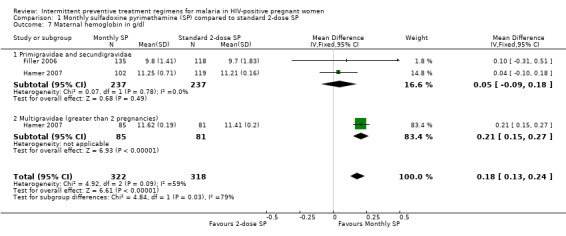

Maternal haemoglobin

Women treated with monthly SP had significant higher haemoglobin level than those treated with treated 2 dose SP (WMD 0.18 g/dL, 95% CI 0.13 g/dL to 0.24 g/dL, 640 participants, two trials) with evidence of statistically significant moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 59%, Chi2 = 4.92, P = 0.09) (see Analysis 1.7). On subgroup analysis, this was only significant among multigravidae.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Monthly sulfadoxine pyrimethamine (SP) compared to standard 2‐dose SP, Outcome 7 Maternal hemoglobin in g/dl.

Maternal viral load

None of the studies assessed the impact of monthly SP on HIV parameters. Hence, maternal viral load was not measured in both trials.

Adverse Drug Reactions (ADR)

Both trials reported on adverse events experienced by the mothers and neonates. Filler 2006 did not report any severe cutaneous ADRs and in no case was SP withheld because of ADR concerns. Less than 1% of the women reported ADRs such as rash, nausea, vomiting, fever and <0.4% of the newborns had neonatal jaundice. However, according to the authors, the differences in the proportion of women and neonates with ADRs in the standard 2‐dose and monthly SP arms were not statistically different (data not provided by the trial). There was one neonatal death of a newborn with jaundice, born to an HIV‐positive mother in the standard 2‐dose SP. However, this death was attributed to prematurity (30 weeks of gestation) and a low birth weight of < 1 kg.

Hamer 2007 reports that one mother who received monthly SP died of presumed Stevens‐Johnson syndrome. However, the trial authors report that the rates for serious and mild adverse events reported by mothers were low and did not differ between the study groups. There was only one case of neonatal jaundice in the monthly SP group and none in the 2‐dose SP group. See Table 8 for details of ADRs across the trials.

3. Reported Adverse Drug Reactions (ADRs).

| Trial | ADRs: Mother | ADRs: Infant |

| Filler 2006 | 1. Less than 1% reported ADRs. 2. In no case was SP withheld because of ADR concerns. 3. No significant difference in proportion of women with ADRs in the 2‐dose and monthly SP arms. 4. No severe ADRs reported | 1. Neonatal jaundice observed in 0.4% of newborns. 2. One neonatal death with jaundice probably due to prematurity |

| Hamer 2007 | 1. Rates of ADRs were very low in both groups. 2. Rates did not differ between groups (RR 1.13 for ADRs in the monthly SP group relative to 2‐dose, 95% CI 0.56‐2.18). 3. One mother on monthly SP died from Stevens‐Johnson syndrome | 1. Rates of ADRs very low. 2. Rates similar across the treatment arms (RR 1.49 for ADRs in the monthly group relative to 2‐dose SP, 95% CI 0.79‐2.8) |

Sensitivity analyses

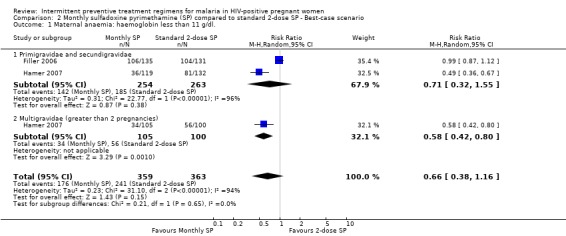

Maternal anaemia

The rates of maternal anaemia were sensitive to the allocation of withdrawals or post‐randomization exclusions. Best‐case scenarios produced larger effect size, but the 95% CI includes no effect (RR 0.66, 95% CI 0.38 to 1.16) (see Analysis 2.1). The worst case scenario produced statistically significant opposite result, such that women treated with monthly‐SP were more likely to have had maternal anaemia compared to those women treated with 2‐dose SP (RR 1.32, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.66) (see Analysis 3.1).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Monthly sulfadoxine pyrimethamine (SP) compared to standard 2‐dose SP ‐ Best‐case scenario, Outcome 1 Maternal anaemia: haemoglobin less than 11 g/dl..

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Monthly sulfadoxine pyrimethamine (SP) compared to standard 2‐dose SP ‐ worst‐case scenario, Outcome 1 Maternal anaemia: haemoglobin less than 11g/dl..

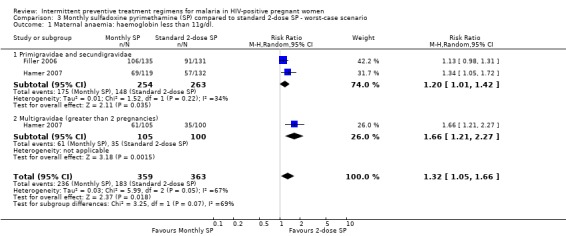

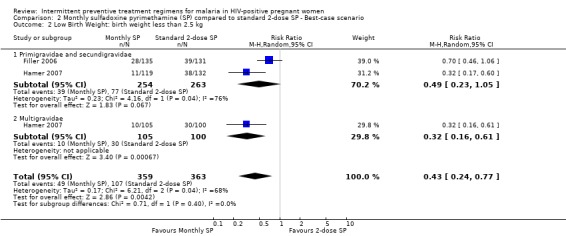

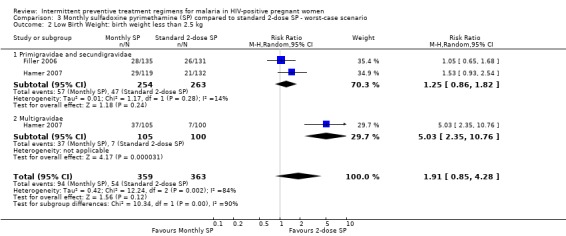

Low birth weight

The rates of low birth weight were sensitive to the allocation of withdrawals or post‐randomization exclusions, because there were considerable differences in the pooled estimates. Best‐case scenario showed that monthly‐SP was more effective than 2‐dose SP in preventing low birth weight (RR 0.43, 95% CI 0.24 to 0.77) (see Analysis 2.2). While worst‐case scenarios showed no difference between the two treatment groups (RR 1.91, 95% CI 0.85 to 4.38) (see Analysis 3.2).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Monthly sulfadoxine pyrimethamine (SP) compared to standard 2‐dose SP ‐ Best‐case scenario, Outcome 2 Low Birth Weight: birth weight less than 2.5 kg.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Monthly sulfadoxine pyrimethamine (SP) compared to standard 2‐dose SP ‐ worst‐case scenario, Outcome 2 Low Birth Weight: birth weight less than 2.5 kg.

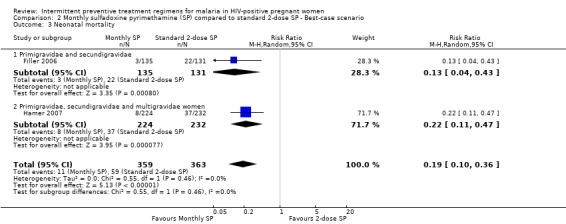

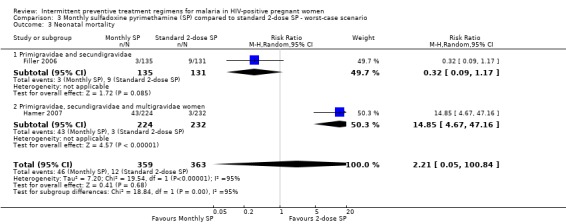

Neonatal mortality

The results of neonatal mortality were sensitivity to the allocation of withdrawals (see Analysis 2.3; Analysis 3.3).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Monthly sulfadoxine pyrimethamine (SP) compared to standard 2‐dose SP ‐ Best‐case scenario, Outcome 3 Neonatal mortality.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Monthly sulfadoxine pyrimethamine (SP) compared to standard 2‐dose SP ‐ worst‐case scenario, Outcome 3 Neonatal mortality.

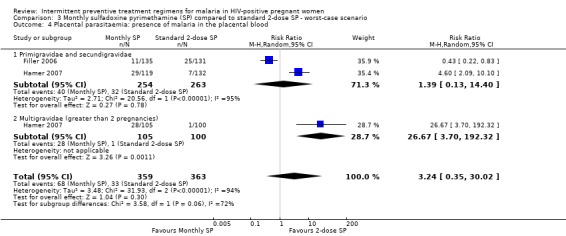

Placental parasitaemia

Best‐case scenario produced similar (but larger effect size) result to that of pooled result from complete case (RR 0.14, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.39) (see Analysis 2.4). Worst‐case scenario showed no statistically significant difference between the two treatment groups (RR 3.24, 95% CI 0.35 to 30.02) (see Analysis 3.4).

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Monthly sulfadoxine pyrimethamine (SP) compared to standard 2‐dose SP ‐ Best‐case scenario, Outcome 4 Placental parasitaemia: presence of malaria in the placental blood.

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Monthly sulfadoxine pyrimethamine (SP) compared to standard 2‐dose SP ‐ worst‐case scenario, Outcome 4 Placental parasitaemia: presence of malaria in the placental blood.

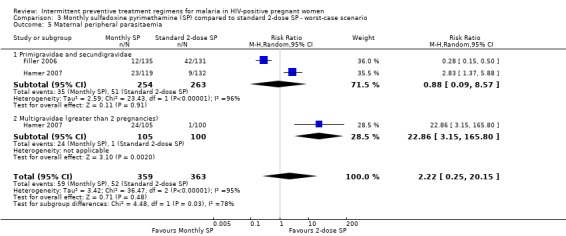

Peripheral parasitaemia

While result of best‐case scenario (RR 0.14, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.33) was similar to that of complete case (see Analysis 2.5), worst scenario produced no statistically significant difference in rates of peripheral parasitaemia (RR 2.22, 95% CI 0.25 to 20.15) (see Analysis 3.5).

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Monthly sulfadoxine pyrimethamine (SP) compared to standard 2‐dose SP ‐ Best‐case scenario, Outcome 5 Maternal peripheral parasitaemia.

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Monthly sulfadoxine pyrimethamine (SP) compared to standard 2‐dose SP ‐ worst‐case scenario, Outcome 5 Maternal peripheral parasitaemia.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Two randomized trials were included, enrolling 722 HIV‐positive pregnant women from Malawi and Zambia. Both compared monthly regimens of SP to the standard 2‐dose regimen given in the second and third trimesters.

In women in their first or second pregnancy, monthly SP may reduce both maternal parasitaemia (low quality evidence), and placental parasitaemia at delivery (low quality evidence). Monthly SP may have a small effect on the prevalence of maternal anaemia at delivery (low quality evidence), and the number of babies born with low birth weight (low quality evidence), but larger trials are necessary to reliably prove or exclude a clinically important benefit on these outcomes. There is currently insufficient evidence to make conclusions regarding an effect on neonatal mortality (very low quality evidence).

In women in their third or higher pregnancy, there is insufficient evidence to make any conclusions on the benefits of monthly SP compared to the two dose regimen (very low quality evidence).

There were no trials that assessed other treatment regimens for intermittent preventive treatment in HIV‐positive pregnant women.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The review identified only two trials related to IPTp regimens for malaria in HIV‐positive pregnant women. One study was conducted in the urban setting whilst the other was done in the rural area and all the studies involved the use of three or more doses of SP during the second and third trimester of pregnancy compared to use of only two doses of SP. No studies of other antimalarial drugs for IPTp in HIV‐positive pregnant women were identified.

Findings reported by Filler 2006 shows that the use of three or more doses was more beneficial in the rural setting than it was in the urban setting (Hamer 2007). The low transmission in the urban area coupled with expansion of LLINs and indoor residual spraying (IRS) (Hamer 2007) might have led to lower prevalence of some of the end points which in turn meant that the study lacked power to detect the changes.

Both trials did not report any significant differences in ADRs between those that received three or more doses compared to those that only received two doses. Whilst this is encouraging, the trials did not address the safety of concurrent administration of SP and co‐trimoxazole in HIV‐positive patients since the WHO now recommends daily prophylaxis with co‐trimoxazole for symptomatic HIV‐positive pregnant women or HIV‐positive pregnant women with low CD4 count (cell count of < 350 cells/mm3) (WHO 2010). Because concurrent use of SP and co‐trimoxazole may increase the incidence of severe ADRs, co‐trimoxazole only is recommended for prevention of malaria in HIV‐positive pregnant women who are eligible for co‐trimoxazole prophylaxis.

Quality of the evidence

The quality of the evidence was assessed using the GRADE methodology and the basis for the judgements is presented in two 'Summary of findings' tables (Table 1; Table 2). Low and very low quality evidence reflect increasing uncertainty in the result and a greater need for further research.

The two studies report the available case analysis. As imputation of missing data in order to perform a full intention‐to‐treat analysis is controversial, we considered the possible effects of the missing participants through sensitivity analyses. The 'Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reveiws of Interventions' suggests that “a sensible decision in most cases is to include data for only those participants whose results are known, and discuss the potential impact of the missing data” (Higgins 2011). Our best‐case and worst‐case imputation for intention‐to‐treat analyses showed a high sensitivity to post‐randomization exclusions. We found evidence that missing data had substantial influence on the pooled results, as there were large differences between complete cases, best‐case and worst‐case scenarios for every outcome.

Potential biases in the review process

We were able to identify all relevant studies and obtain all relevant data. It is unlikely that the methods used in the review could have introduced bias.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

To the best of our no knowledge, there are no other reviews to compare with this Cochrane Review.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Three or more doses of SP may have some advantages over the standard two doses in HIV‐positive pregnant women, but larger trials would be necessary to confirm an effect on patient important outcomes. However, since SP cannot be administered concurrently with co‐trimoxazole ‐ a drug often recommended for infection prophylaxis in HIV‐positive pregnant women ‐ new drugs and research is needed to address needs of HIV‐positive pregnant women.

Implications for research.

Apart from SP, this review did not find any other regimens to prevent malaria in HIV‐positive pregnant women. Since SP can not be administered concurrently with co‐trimoxazole, its important that the safety and efficacy of other antimalarials be studied in HIV‐positive pregnant women, especially now that resistance to SP is high in many malaria endemic countries. It is also important to study the efficacy of using co‐trimoxazole in preventing malaria in HIV‐postive pregnant women. Recent data from Malawi suggests that daily co‐trimoxazole is more effective at reducing malaria infections and anaemia compared with IPTp using SP in HIV‐positive pregnant women (Kapito‐Tembo 2011). However, there is need to collaborate these findings in other settings through more robust methodologies.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 18 July 2012 | Amended | The GRADE assessments were adjusted in the summary of findings tables and the conclusions were modified in accordance with this. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 3, 2007 Review first published: Issue 10, 2011

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 5 October 2010 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

Acknowledgements

Don P. Mathanga was awarded a Reviews for Africa Programme Fellowship (www.mrc.ac.za/cochrane/rap.htm), funded by a grant from the Nuffield Commonwealth Programme, through The Nuffield Foundation. The editorial base for the Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group is funded by the UK Department for International Development (DFID) for the benefit of low‐ and middle‐income countries.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Monthly sulfadoxine pyrimethamine (SP) compared to standard 2‐dose SP.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Maternal anaemia: (haemoglobin less than 11g/dl) | 2 | 604 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.84, 1.12] |

| 1.1 Primigravidae and secundigravidae | 2 | 447 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.72, 1.20] |

| 1.2 Multigravidae (greater than 2 pregnancies) | 1 | 157 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.69, 1.40] |

| 2 Low Birth Weight: birth weight less than 2.5 kg | 2 | 624 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.88 [0.59, 1.32] |

| 2.1 Primigravidae and secundigravidae | 2 | 469 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.80 [0.52, 1.23] |

| 2.2 Multigravidae | 1 | 155 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.41 [0.57, 3.51] |

| 3 Neonatal mortality | 2 | 640 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.90 [0.10, 8.23] |

| 3.1 Primigravidae and secundigravidae | 1 | 253 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.29 [0.08, 1.05] |

| 3.2 Primigravidae, secundigravidae and multigravidae women | 1 | 387 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.79 [0.75, 10.37] |

| 4 Placental parasitaemia: presence of malaria in the placental blood | 2 | 612 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.42 [0.23, 0.76] |

| 4.1 Primigravidae and secundigravidae | 2 | 459 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.38 [0.21, 0.70] |

| 4.2 Multigravidae (greater than 2 pregnancies) | 1 | 153 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.87 [0.17, 20.23] |

| 5 Maternal peripheral parasitaemia | 2 | 622 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.26 [0.15, 0.45] |

| 5.1 Primigravidae and secundigravidae | 2 | 463 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.25 [0.14, 0.43] |

| 5.2 Multigravidae (greater than 2 pregnancies) | 1 | 159 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.94 [0.06, 14.75] |

| 6 Birth weight in kilograms | 2 | 640 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.10 [0.09, 0.11] |

| 6.1 Primigravidae and secundigravidae | 2 | 474 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.13 [0.12, 0.15] |

| 6.2 Multigravidae (greater than 2 pregnancies) | 1 | 166 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.01 [‐0.01, 0.03] |

| 7 Maternal hemoglobin in g/dl | 2 | 640 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.18 [0.13, 0.24] |

| 7.1 Primigravidae and secundigravidae | 2 | 474 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.05 [‐0.09, 0.18] |

| 7.2 Multigravidae (greater than 2 pregnancies) | 1 | 166 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.21 [0.15, 0.27] |

Comparison 2. Monthly sulfadoxine pyrimethamine (SP) compared to standard 2‐dose SP ‐ Best‐case scenario.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Maternal anaemia: haemoglobin less than 11 g/dl. | 2 | 722 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.66 [0.38, 1.16] |

| 1.1 Primigravidae and secundigravidae | 2 | 517 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.71 [0.32, 1.55] |

| 1.2 Multigravidae (greater than 2 pregnancies) | 1 | 205 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.58 [0.42, 0.80] |

| 2 Low Birth Weight: birth weight less than 2.5 kg | 2 | 722 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.43 [0.24, 0.77] |

| 2.1 Primigravidae and secundigravidae | 2 | 517 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.49 [0.23, 1.05] |

| 2.2 Multigravidae | 1 | 205 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.32 [0.16, 0.61] |

| 3 Neonatal mortality | 2 | 722 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.19 [0.10, 0.36] |

| 3.1 Primigravidae and secundigravidae | 1 | 266 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.13 [0.04, 0.43] |

| 3.2 Primigravidae, secundigravidae and multigravidae women | 1 | 456 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.22 [0.11, 0.47] |

| 4 Placental parasitaemia: presence of malaria in the placental blood | 2 | 722 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.14 [0.05, 0.39] |

| 4.1 Primigravidae and secundigravidae | 2 | 517 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.19 [0.06, 0.57] |

| 4.2 Multigravidae (greater than 2 pregnancies) | 1 | 205 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.07 [0.02, 0.29] |

| 5 Maternal peripheral parasitaemia | 2 | 722 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.11 [0.04, 0.33] |

| 5.1 Primigravidae and secundigravidae | 2 | 517 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.16 [0.06, 0.40] |

| 5.2 Multigravidae (greater than 2 pregnancies) | 1 | 205 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.04 [0.01, 0.29] |

Comparison 3. Monthly sulfadoxine pyrimethamine (SP) compared to standard 2‐dose SP ‐ worst‐case scenario.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Maternal anaemia: haemoglobin less than 11g/dl. | 2 | 722 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.32 [1.05, 1.66] |

| 1.1 Primigravidae and secundigravidae | 2 | 517 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.20 [1.01, 1.42] |

| 1.2 Multigravidae (greater than 2 pregnancies) | 1 | 205 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.66 [1.21, 2.27] |

| 2 Low Birth Weight: birth weight less than 2.5 kg | 2 | 722 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.91 [0.85, 4.28] |

| 2.1 Primigravidae and secundigravidae | 2 | 517 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.25 [0.86, 1.82] |

| 2.2 Multigravidae | 1 | 205 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 5.03 [2.35, 10.76] |

| 3 Neonatal mortality | 2 | 722 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.21 [0.05, 100.84] |

| 3.1 Primigravidae and secundigravidae | 1 | 266 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.32 [0.09, 1.17] |

| 3.2 Primigravidae, secundigravidae and multigravidae women | 1 | 456 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 14.85 [4.67, 47.16] |

| 4 Placental parasitaemia: presence of malaria in the placental blood | 2 | 722 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 3.24 [0.35, 30.02] |

| 4.1 Primigravidae and secundigravidae | 2 | 517 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.39 [0.13, 14.40] |

| 4.2 Multigravidae (greater than 2 pregnancies) | 1 | 205 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 26.67 [3.70, 192.32] |

| 5 Maternal peripheral parasitaemia | 2 | 722 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.22 [0.25, 20.15] |

| 5.1 Primigravidae and secundigravidae | 2 | 517 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.88 [0.09, 8.57] |

| 5.2 Multigravidae (greater than 2 pregnancies) | 1 | 205 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 22.86 [3.15, 165.80] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Filler 2006.

| Methods | Design: RCT | |

| Participants | Number: 266 were enrolled Inclusion Criteria: HIV positive women in the first or second pregnancy Exclusion criteria: prior adverse reaction to sulfa‐containing drugs |

|

| Interventions | 1. Monthly intermittent preventive treatment using sulphadoxine‐pyrimethamine 2. Control: 2 doses of sulphadoxine‐pyrimethamine |

|

| Outcomes | 1. Maternal anaemia

2. Peripheral parasitaemia

3. Placental parasitaemia

4. Maternal haemoglobin at delivery

5. Neonatal death

6. Birth weight

7. ADR Not included in this review Uncomplicated malaria 3rd trimester anaemia |

|

| Notes | Location: Malawi Date: 2002‐5 Funding: WHO/ CDC |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Generation of allocation sequence: permuted blocks of random length. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No details of allocation concealment are given by the study. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Clinicians | High risk | No. "Neither study participants nor clinicians were blinded to group assignment". |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Patients | High risk | No. "Neither study participants nor clinicians were blinded to group assignment". |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Technicians | Low risk | Blinding was only done for the laboratory technicians assessing the outcome of placental malaria |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | The proportion of missing outcomes compared with observed event risk enough to induce clinically relevant bias in intervention effect estimate as demonstrated by the sensitivity analysis . |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | The method section does not set out clearly the outcomes which were to be measured. |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other biases suspected. |

Hamer 2007.

| Methods | Design: RCT | |

| Participants | Number: 456 were enrolled Inclusion Criteria: HIV positive women of any gravidity Exclusion criteria: prior adverse reaction to sulfa‐containing drugs and women aged <18 years |

|

| Interventions | 1. Monthly intermittent preventive treatment using sulphadoxine‐pyrimethamine 2. Control: 2 doses of sulphadoxine‐pyrimethamine, one in 2nd trimester and the other in 3rd trimester |

|

| Outcomes | 1. Placental malaria (by histology)

2. Placental parasitaemia

3. Peripheral parasitaemia

4. Placental malaria

5. Maternal anaemia at delivery

6. LBW

7. ADR Not included in this review 1. Gestational age 2. Uncomplicated malaria 3. Cord blood parasitaemia |

|

| Notes | Location: Zambia Date: 2003 ‐ 4 Funding: Cooperative Agreement No. S1954‐21/21 |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Generation of allocation sequence: randomization was done in blocks of 20 |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Allocation concealment: participants were assigned sequential ID numbers corresponding to a sealed package of trial drugs whilst randomization codes were retained in the USA |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Clinicians | Low risk | Investigators were blinded. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Patients | Low risk | Trial participants were blinded. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Technicians | Low risk | Laboratory/ pathologists were all blinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | Inclusion of randomized participants in the analysis: participants with data available were analyzed and not everyone randomised |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All outcomes are included in the results section. |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other biases suspected. |

RCT = Randomized Controlled Trial HIV = Human Immonodeficiency Virus ADR = Adverse Drug Reactions CDC = Centers for Disease Control WHO = World Health Organization LBW = Low Birth Weight

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Parise 1998 | Non‐randomized trial with treatment assigned based day of clinic visit |

Characteristics of ongoing studies [ordered by study ID]

Korukiiko.

| Trial name or title | "Influence of HIV infection on the effectiveness of malaria prevention during pregnancy, with emphasis on the effect of chloroquine on HIV viral load among pregnant women in Uganda" |

| Methods | |

| Participants | Expected enrolment: sample size not given Minimum age: 15 Inclusion criteria: HIV positive pregnant women 14‐24 weeks gestation Exclusion criteria: pregnant women with severe disease or at risk pregnancy |

| Interventions | 1: Intervention: sulphadoxine‐pyrimethamine plus chloroquine 2. Control: sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine |

| Outcomes | 1. Maternal parasitaemia; 2. Placental parasitaemia 3. Clinical malaria 4. Maternal and infant Hb 5. Birth weight 6. Congenital parasitaemia 7. Maternal HIV viral load |

| Starting date | Not clear |

| Contact information | Lucy N Korukiiko Uganda AIDS Commission

Kampala

P.O. Box 10779 lucymanzi@yahoo.co.uk |

| Notes | ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00132535 Data analysis on going. |

Macarthur.

| Trial name or title | "Efficacy of intermittent sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine and sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine + artesunate treatment in the prevention of malaria in pregnancy in an area with chloroquine‐resistant plasmodium falciparum" |

| Methods | |

| Participants | Expected enrolment: sample size not given Minimum age: 15 Inclusion criteria: HIV (?) pregnant women aged 15 years or older in their 1st or 2nd pregnancy Exclusion criteria: multigravida women, gestation age < 16 weeks or > 36 weeks, prior history of allergic reactions to sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine or artesunate |

| Interventions | 1. Intervention: sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine plus artesunate 2. Control: sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine |

| Outcomes | 1. Placental

parasitaemia 2. Adverse reactions. 3. Parasitemia at delivery 4. Maternal illness 5. Birth weight 6. Gestational age |

| Starting date | January 2003 |

| Contact information | John Macarthur Tel: 770‐488‐7755 ZAE5@CDC.GOV |

| Notes | ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00164255 Study finished and data analysis going on |

Manyando.

| Trial name or title | Establishing Effectiveness of Daily Co‐trimoxazole Prophylaxis For Prevention of Malaria in Pregnancy |

| Methods | Randomized study |

| Participants | Expected enrolment: sample size not given. Minimum age: All HIV pregnant women, no age limit given. Inclusion criteria: HIV positive and HIV negative pregnant women, Hb > 7 g/dl, gestational age between 16 and 28 weeks. Exclusion criteria: Severe anaemia (Hb<7 g/dl) and HIV women already on cotrimoxazole |

| Interventions |

|

| Outcomes | 1. Placental parasitaemia 2. Adverse reactions. 3. Parasitemia at delivery 4. Maternal illness 5. Birth weight 6. Gestational age |

| Starting date | April 2010 |

| Contact information | Christine Manyando, MD Tel: 260 212 621732 cmanyando@yahoo.com |

| Notes | NCT01053325 |

AIDS = Acquired Immunodeficiency syndrome Hb = haemoglobin HIV = Human Immunodeficiency Virus IPTp = Intermittent Preventive Treatment in pregnancy MTCT = mother‐to‐child HIV transmission

Contributions of authors

Both authors have contributed to the development of the protocol, selection of studies, and analysis and interpretation of the data.

Sources of support

Internal sources

Reviews for Africa Programme, South Africa.

South African Cochrane Centre, South Africa.

MPH Program, Department of Community Health, College of Medicine, Malawi.

Malaria Alert Center, Malawi.

External sources

Nuffield Commonwealth Foundation, UK.

Department for International Development (DFID), UK.

Declarations of interest

None known for both authors.

Unchanged

References

References to studies included in this review

Filler 2006 {published data only}

- Filler S, Kazembe P, Thigpen M, Macheso A, Parise M, Newman R, et al. Randomized trial of 2‐dose versus monthly sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine intermittent preventive treatment for malaria in HIV‐positive and HIV‐negative pregnant women in Malawi. Journal of Infectious Diseases 2006;194(3):286‐93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hamer 2007 {published data only}

- Hamer D, Mwanakasale V, MacLeod W, Chalwe V, Mukwamataba D, Champo D, et al. Two‐dose versus monthly intermittent preventive treatment of malaria with sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine in HIV‐seropositive pregnant Zambian women. Journal of Infectious Diseases 2007;196(11):1585‐94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Parise 1998 {published data only}

- Parise M, Ayisi J, Nahlen B, Schultz L, Roberts J, Misore A, et al. Efficacy of sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine for prevention of placental malaria in an area of Kenya with a high prevalence of malaria and human immunodeficiency virus infection. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 1998;59(5):813‐22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to ongoing studies

Korukiiko {unpublished data only}

- "Influence of HIV infection on the effectiveness of malaria prevention during pregnancy, with emphasis on the effect of chloroquine on HIV viral load among pregnant women in Uganda". Ongoing study Not clear.

Macarthur {unpublished data only}

- "Efficacy of intermittent sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine and sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine + artesunate treatment in the prevention of malaria in pregnancy in an area with chloroquine‐resistant plasmodium falciparum". Ongoing study January 2003.

Manyando {unpublished data only}

- Establishing Effectiveness of Daily Co‐trimoxazole Prophylaxis For Prevention of Malaria in Pregnancy. Ongoing study April 2010.

Additional references

Abu‐Raddad 2006

- Abu‐Raddad LJ, Patnaik P, Kublin JG. Dual infection with HIV and malaria fuels the spread of both diseases in sub‐Saharan Africa. Science 2006;314(5805):1603‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bijl 2000

- Bijl HM, Kager J, Koetsier DW, Werf TS. Chloroquine‐ and sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine‐resistant Falciparum malaria in vivo ‐ a pilot study in rural Zambia. Tropical Medicine and International Health 2000;5(10):692‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Brahmbhatt 2003

- Brahmbhatt H, Kigozi G, Wabwire‐Mangen F, Serwadda D, Sewankambo N, Lutalo T, et al. The effects of placental malaria on mother‐to‐child HIV transmission in Rakai, Uganda. AIDS 2003;17(17):2539‐41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Chalwe 2009

- Chalwe V, geertruyden JP, Mukwamataba D, Menten J, Kamalamba J, Mulenga M, et al. Increased risk for severe malaria in HIV‐1‐infected adults, Zambia. Emerging Infectious Diseases 2009;15(5):749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Chico 2008

- Chico RM, Pittrof R, Greenwood B, Chandramohan D. Azithromycin‐chloroquine and the intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy. Malaria Journal 2008;7:255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cot 2003

- Cot M, Deloron P. Malaria prevention strategies. British Medical Bulletin 2003;67:137‐48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dabis 2002

- Dabis F, Ekpini ER. HIV‐1/AIDS and maternal and child health in Africa. Lancet 2002;359(9323):2097‐104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

French 2001

- French N, Nakiyingi J, Lugada E, Watera C, Whitworth JA, Gilks CF. Increasing rates of malarial fever with deteriorating immune status in HIV‐1‐infected Ugandan adults. AIDS 2001;15(7):899‐906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Froebel 2004

- Froebel K, Howard W, Schafer JR, Howie F, Whitworth J, Kaleebu P, et al. Activation by malaria antigens renders mononuclear cells susceptible to HIV infection and re‐activates replication of endogenous HIV in cells from HIV‐infected adults. Parasite Immunology 2004;26(5):213‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Garner 2006

- Garner P, Gülmezoglu AM. Drugs for preventing malaria in pregnant women. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2006, Issue 4. [Art. No.: CD000169. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000169.pub2.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2011

- Higgins JPT, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. [Chapter 16: Special topics in statistics]. In: Higgins JPT, Deeks JJ, Altman DG editor(s). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011). updated March 2011, 2011. [Google Scholar]

Kapito‐Tembo 2011

- Kapito‐Tembo A, Meshnick SR, Hensbroek MB, Phiri K, Fitzgerald M, Mwapasa V. Marked reduction in prevalence of malaria parasitemia and anemia in HIV‐infected pregnant women taking cotrimoxazole with or without sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine intermittent preventive therapy during pregnancy in Malawi. Journal of Infectious Diseases 2011;203(4):464‐72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Korenromp 2005

- Korenromp E, for the RBM Monitoring and Evaluation Reference Group & MERG Task Force on Malaria Morbidity. Malaria incidence estimates at country level for the year 2004 ‐ Proposed estimates and draft report. www.who.int/malaria/docs/incidence_estimations2.pdf 2005 (accessed on 22 Septermber 2006).

Korenromp 2005a

- Korenromp EL, Williams BG, Vlas SJ, Gouws E, Gilks CF, Ghys PD, et al. Malaria attributable to the HIV‐1 epidemic, sub‐Saharan Africa. Emerging infectious diseases 2005;11(9):1410‐9. [PUBMED: 16229771] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kublin 2005

- Kublin JG, Patnaik P, Jere CS, Miller WC, Hoffman IF, Chimbiya N, et al. Effects of plasmodium falciparum malaria on concentration of HIV‐1‐RNA in the blood of adults in rural Malawi: a prospective cohort study. Lancet 2005;365(9455):233‐40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lefebvre 2011

- Lefebvre C, Manheimer E, Glanville J. Chapter 6: Searching for studies.. In: Higgins JPT, Green S editor(s). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.0.1 (updated March 2011). The Cochrane Collaboration. Available from www.cochrane‐handbook.org, 2011. [Google Scholar]

Malamba 2007

- Malamba S, Hladik W, Reingold A, Banage F, McFarland W, Rutherford G, et al. The effect of HIV on morbidity and mortality in children with severe malarial anaemia. Malaria Journal 2007;6:143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Malenga 2009

- Malenga G, Wirima J, Kazembe P, Nyasulu Y, Mbvundula M, Nyirenda C, et al. Developing national treatment policy for falciparum malaria in Africa: Malawi experience. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 2009;103(Suppl 1):S15‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Msamanga 2009

- Msamanga GI, Taha TE, Young AM, Brown ER, Hoffman IF, Read JS, et al. Placental malaria and mother‐to‐child transmission of human immunodeficiency virus‐1. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 2009;80(4):508‐15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mulenga 2006

- Mulenga M, Geertruyden JP, Mwananyanda L, Chalwe V, Moerman F, Chilengi R, et al. Safety and efficacy of lumefantrine‐artemether (Coartem) for the treatment of uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Zambian adults. Malaria Journal 2006;5:73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Parise 1998

- Parise ME, Ayisi JG, Nahlen BL, Schultz LJ, Roberts JM, Misore A, et al. Efficacy of sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine for prevention of placental malaria in an area of Kenya with a high prevalence of malaria and human immunodeficiency virus infection. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 1998;59(5):813‐22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Perrault 2009

- Perrault SD, Hajek J, Zhong K, Owino SO, Sichangi M, Smith G, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus co‐infection increases placental parasite density and transplacental malaria transmission in Western Kenya. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 2009;80(1):119‐25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Review Manager 5.0 [Computer program]

- The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration. Review Manager (RevMan). Version 5.0 for Windows. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2008.

Steketee 1996

- Steketee RW, Wirima JJ, Bloland PB, Chilima B, Mermin JH, Chitsulo L, et al. Impairment of a pregnant woman's acquired ability to limit plasmodium falciparum by infection with human immunodeficiency virus type‐1. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 1996;55 Suppl 1:42‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Tagbor 2006

- Tagbor H, Bruce J, Browne E, Randal A, Greenwood B, Chandramohan D. Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of amodiaquine plus sulphadoxine‐pyrimethamine used alone or in combination for malaria treatment in pregnancy: a randomised trial. Lancet 2006;368(9544):1349‐56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

ter Kuile 2004

- ter Kuile FO, Parise ME, Verhoeff FH, Udhayakumar V, Newman RD, Eijk AM, et al. The burden of co‐infection with the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and malaria in pregnant women in sub‐saharan Africa. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 2004;71(Suppl 2):41‐5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

UNAIDS 2010

- United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Epidemic update. UNAIDS Report on the global AIDS epidemic 2010. UNAIDS, 2010:16‐61. [Google Scholar]

Van Geertruyden 2006

- Geertruyden JP, Mulenga M, Mwananyanda L, Chalwe V, Moerman F, Chilengi R, et al. HIV‐1 immune suppression and antimalarial treatment outcome in Zambian adults with uncomplicated malaria. Journal of Infectious Diseases 2006;194(7):917‐25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Whitworth 2000

- Whitworth J, Morgan D, Quigley M, Smith A, Mayanja B, Eotu H, et al. Effect of HIV‐1 and increasing immunosuppression on malaria parasitaemia and clinical episodes in adults in rural Uganda: a cohort study. Lancet 2000;356(9235):1051‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

WHO 2004

- World Health Organization, Regional Office for Africa. A strategic framework for malaria prevention and control during pregnancy in the African region [AFR/MAL/04/01]. Brazzaville: World Health Organization, 2004. [Google Scholar]

WHO 2010

- World Health Organization. Antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection in adults and adolescents: Recommendations for a public health approach. Antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection in adults and adolescents: Recommendations for a public health approach. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

WHO 2010a

- WHO/UNAIDS/UNICEF. Towards Universal Access: Scaling up priority HIV/AIDS interventions in the health sector. Geneva: WHO, 2010. [Google Scholar]