Abstract

Background

Scabies is an intensely itchy parasitic infection of the skin caused by the Sarcoptes scabiei mite. It is a common public health problem with an estimated global prevalence of 300 million cases. Serious adverse effects have been reported for some drugs used to treat scabies.

Objectives

To evaluate topical and systemic drugs for treating scabies.

Search methods

In June 2010, we searched the Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group Specialized Register, CENTRAL (The Cochrane Library 2010, Issue 2), MEDLINE, EMBASE, LILACS, and INDMED. In August 2010, we also searched the grey literature and sources for registered trials. We also checked the reference lists of retrieved studies.

Selection criteria

Randomized controlled trials of drug treatments for scabies.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently assessed trial quality and extracted data. Results were presented as risk ratios with 95% confidence intervals and data combined where appropriate.

Main results

Twenty‐two small trials involving 2676 people were included. One trial was placebo controlled, 18 compared two or more drug treatments, three compared treatment regimens, and one compared different drug vehicles.

Fewer treatment failures occurred by day seven with oral ivermectin compared with placebo in one small trial (55 participants). Topical permethrin appeared more effective than oral ivermectin (140 participants, 2 trials), topical crotamiton (194 participants, 2 trials), and topical lindane (753 participants, 5 trials). Permethrin also appeared more effective in reducing itch persistence than either crotamiton (94 participants, 1 trial) or lindane (490 participants, 2 trials). No difference was detected between permethrin (a synthetic pyrethroid) and a natural pyrethrin‐based topical treatment (40 participants, 1 trial), and between permethrin and benzyl benzoate (53 participants, 1 trial), however both these trials were small.

No significant difference was detected in the number of treatment failures between crotamiton and lindane (100 participants, 1 trial), lindane and sulfur (68 participants, 1 trial), benzyl benzoate and sulfur (158 participants, 1 trial), and benzyl benzoate and natural synergized pyrethrins (240 participants, 1 trial); all were topical treatments. No trials of malathion were identified.

No serious adverse events were reported. A number of trials reported skin reactions in participants randomized to topical treatments. There were occasional reports of headache, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, vomiting, and hypotension.

Authors' conclusions

Topical permethrin appears to be the most effective treatment for scabies. Ivermectin appears to be an effective oral treatment. More research is needed on the effectiveness of malathion, particularly when compared to permethrin, and on the management of scabies in an institutional setting and at a community level.

23 April 2019

No update planned

Review superseded

This review includes an evaluation of crotamiton, lindane, sulfur, and benzyl benzoate. However, these are not active areas of research and are not widely used for treatment. A new assessment of ivermectin and permethrin alone is justified and thus this Cochrane Review has been superseded by Rosumeck 2018 https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012994

Plain language summary

Interventions for treating scabies

Scabies is a parasitic infection of the skin. It occurs throughout the world, but is particularly problematic in areas of poor sanitation, overcrowding, and social disruption, and is endemic in many resource‐poor countries. The global prevalence of scabies is estimated at 300 million cases, but the level of infection varies between countries and communities. The female mite burrows into the skin to lay eggs which then hatch out and multiply. The infection can spread from person to person via direct skin contact, including sexual contact. It causes intense itching with eruptions on the skin. Various drugs have been developed to treat scabies, and herbal and traditional medicines are also used. The review of trials attempted to cover all these. The authors identified 22 small trials involving 2676 people, with 19 of the trials taking place in resource‐poor countries. Permethrin appeared to be the most effective topical treatment for scabies, and ivermectin appeared to be an effective oral treatment. However, ivermectin is unlicensed for this indication in many countries. Adverse events such as rash, vomiting, and abdominal pain were reported, but the trials were too small to properly assess serious but rare potential adverse effects. No trials of herbal or traditional medicines were identified for inclusion.

Background

What is scabies?

Scabies is an intensely itchy parasitic infection of the skin that is caused by the Sarcoptes scabiei mite. It occurs throughout the world, but is particularly problematic in areas of poor sanitation, overcrowding, and social disruption. The global prevalence of scabies is estimated at 300 million cases (Alexander 1984), with large variations between countries. In the UK, no up‐to‐date robust prevalence data exist, but general practitioners recorded approximately 1200 new cases per year in the 1990s (Downs 1999). In resource‐rich communities, scabies tends to occur in cyclical epidemics, particularly within institutional‐living situations such as nursing homes (Scheinfeld 2004) or the army (Mimouni 1998; Mimouni 2003). There is some seasonal variation with incidence being greater in the winter than the summer, perhaps related to the tendency for more indoor overcrowding in colder weather (Downs 1999). In resource‐poor communities, the occurrence pattern is quite different with the disease being endemic in many areas (Chosidow 2000). For example, the prevalence of scabies among the remote Aboriginal communities of Northern Australia is around 50% in children and 25% in adults (Wong 2002). The prevalence of infection in a community is potentially influenced by changes in social attitudes, population movements, wars, misdiagnosis, inadequate treatment, and changes in the immune status of the population. Scabies infestation represents a considerable burden of ill health in many communities, and although the disease is rarely life threatening, it causes widespread debilitation and misery (Green 1989).

The life cycle of S.scabiei begins with the pregnant female laying two to three eggs a day in burrows several millimetres to several centimetres in length in the stratum corneum (outermost layer) of the skin. After about 50 to 72 hours, larvae emerge and make new burrows. They mature, mate, and repeat this 10‐ to 17‐day cycle. Mites usually live for 30 to 60 days (Green 1989).

Humans are the main reservoir for S.scabiei var. hominis (variety of the mite named to reflect the main host species). Scabies is usually spread person to person via direct skin contact, including sexual contact, though transfer via inanimate objects such as clothing or furnishings is also possible (Hay 2004). The mite can burrow beneath the skin within 2.5 minutes, though around 20 minutes is more usual (Alexander 1984). The level of infectiousness of an individual depends in part on the number of mites harboured, which can vary from just a single mite to millions (Chosidow 2000). Humans can also be transiently infected by the genetically distinct animal varieties of S. scabiei (eg var. canis), though cross infectivity is low (Fain 1978; Walton 2004).

Clinical infection with the scabies mite causes discomfort and often intense itching of the skin, particularly at night, with irritating papular or vesicular eruptions. While infestation with the scabies mite is not life threatening, the severe, persistent itch debilitates and depresses people (Green 1989). The classical sites of infestation are between the fingers, the wrists, axillary areas, female breasts (particularly the skin of the nipples), peri‐umbilical area, penis, scrotum, and buttocks. Infants are usually affected on the face, scalp, palms, and soles. Much of the itching associated with scabies is as a result of the host immune reaction, and symptoms can take several weeks to appear after initial infection in a person exposed to scabies for the first time. Symptoms appear after a much shorter interval (one to two days) after reinfestation (Arlian 1989).

A more severe or 'crusted' presentation of infestation is associated with extreme incapacity and with disorders of the immune system, such as HIV infection. Clinically this atypical form of scabies presents with a hyperkeratotic dermatosis resembling psoriasis. Lymphadenopathy and eosinophilia can be present, but itching may be unexpectedly mild. Patients with crusted scabies may harbour millions of mites and are highly infectious (Meinking 1995a). The dermatological distribution of mites in such patients is often atypical (eg including the head), and treatment in hospital is often advised (Chosidow 2000).

Complications are few although secondary bacterial infection of the skin lesions by group A Streptococcus pyogenes or Staphylococcus aureus, or both, can occur following repeated scratching, particularly in warmer climates (Meinking 1995a). Secondary infection with group A Streptococcus can lead to acute glomerulonephritis, outbreaks of which have been associated with scabies (Green 1989).

Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention

Diagnosis on clinical grounds is usually made on a history of itching (particularly if contacts are also affected) and the finding of lesions in the classical sites. The diagnosis can in most cases be confirmed by microscopically identifying a mite, egg, or mite faeces in a skin scraping, or by extracting a mite from a burrow (Chosidow 2000).

Various treatments are available for scabies. These include sulfur compounds, which have been used for centuries; benzyl benzoate (first used in 1931); crotamiton (used since the late 1970s); hexachlorocyclohexane, which is also known as gamma benzene hexachloride or the commercial purified form lindane ('lindane' is used in this review) (available since 1948); malathion (used since the mid 1970s); permethrin (first licensed in 1985 by the US Food and Drug Administration); and oral ivermectin (first used in humans in the 1980s). A number of herbal remedies have also been proposed (Oladimeji 2000; Alebiosu 2003; Oladimeji 2005).

Serious adverse effects have been associated with the use of some antiscabietic treatments. Convulsions and aplastic anaemia have been reported with the use of lindane (Rauch 1990; Elgart 1996), and an increased risk of death amongst elderly patients has been reported with the use of ivermectin (Barkwell 1997).

Evidence of cure ideally requires follow up for about one month. This allows time for lesions to heal and for any eggs and mites to reach maturity if treatment fails (ie beyond the longest incubation interval). Patients should be warned that itching may persist for one to two weeks after treatment, even if the mite is successfully eradicated (Buffet 2003). Because of this delay in symptom relief it may sometimes be difficult to distinguish reinfestation from primary treatment failure.

Contacts of cases are usually advised to treat themselves at the same time as the case in order to reduce the risk of reinfestation (Orkin 1976). Prevention is based on principles common to most infectious diseases, that is, limitation of contact with the mite.

Using data from randomized controlled trials, this review examines the existing evidence of effectiveness of treatments for scabies.

Objectives

To evaluate topical and systemic drugs for treating scabies.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomized controlled trials.

Types of participants

Children or adults with a clinical or parasitological diagnosis of scabies.

Types of interventions

Intervention

Drug treatment (systemic or local).

Herbal or traditional medicine treatment.

Any combination of above.

Treatment of contacts in addition to cases.

Control

Placebo or no intervention.

A different drug intervention, drug intervention vehicle, intervention regimen, or combination of interventions.

Different or no treatment of contacts.

Types of outcome measures

Primary

Treatment failure in a clinically diagnosed case.

Treatment failure in a parasitologically confirmed case.

Treatment failure is defined in both the above cases as the persistence of original lesions, the appearance of new lesions, or confirmation of a live mite.

Secondary

Persistence of patient‐reported itch.

Adverse events

Serious adverse event that leads to death, is life threatening, results in persistent or significant disability or incapacity, or requires hospitalization.

Adverse event that requires discontinuation of treatment.

Other adverse event.

Search methods for identification of studies

We attempted to identify all relevant trials regardless of language or publication status (published, unpublished, in press, and in progress).

Databases

We searched the following databases using the search terms and strategy described in Appendix 1: Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group Specialized Register (June 2010); Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library 2010, Issue 2); MEDLINE (1966 to June 2010); EMBASE (1974 to June 2010); LILACS (1982 to June 2010); and INDMED (June 2010).

Grey literature

In August 2010, we searched the following sources for published and unpublished trials using the term 'scabies': British Library Index of Conference Proceedings (catalogue.bl.uk/); British Library for Development Studies (blds.ids.ac.uk/); BRIDGE (www.bridge.ids.ac.uk/); Social Care Online (www.scie‐socialcareonline.org.uk/); EconLit; ERIC; Institute for Development Studies (www.ids.ac.uk/ids/particip/information/readrm.html); IIED (www.iied.org/). We searched Science.gov (www.science.gov/) using the terms 'scabies' AND ('trial' OR 'study').

Registered trials

In August 2010, we searched the following sources for registered trials using the term 'scabies': Current Controlled Trials (www.controlled‐trials.com/); Thompson CenterWatch Clinical Trials Listing Service (www.centerwatch.com/); US National Institutes of Health ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov/); TrialsCentral (www.trialscentral.org/); and the UK Department of Health National Research Register (www.nihr.ac.uk/).

Reference lists

We checked the reference lists of all retrieved trials.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

All identified trials were entered into a trials register. MS and PJ independently applied the inclusion criteria to the potentially relevant trials. If a trial's eligibility was unclear, we attempted to contact the trial authors for further information. MS reassessed all included and excluded trials cited in the previous review version (Walker 2000). Where the review authors disagreed, the Co‐ordinating Editor of the Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group was consulted, and a consensus reached among the three parties; this process was also used for assessing the risk of bias in trials, and extracting data. The trial reports were scrutinized to ensure that multiple publications from the same trial were included only once. We listed the reasons for excluding studies in the 'Characteristics of excluded studies'.

Data extraction and management

We independently extracted data from the newly included trials. Where important data were missing, we attempted to contact the trial authors for further information. MS entered the data into Review Manager 5.0. We extracted the number of patients randomized and the number analysed for each group for each trial. For each dichotomous outcome, we recorded the number of participants experiencing the event in each arm of the trial.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Both authors independently assessed the quality of the newly included trials. We assessed the generation of allocation sequence and allocation concealment as adequate, inadequate, or unclear (Juni 2001). We assessed the inclusion of randomized participants in the analysis to be adequate if greater than 80%. We recorded who was blinded (eg participants or investigators) rather than using potentially ambiguous terms such as double blind or single blind. MS reassessed the included trials from the previous review version (Walker 2000).

Data synthesis

MS analysed the data using Review Manager 5.0. Analyses were stratified by comparison. We undertook an available case analysis, that is, participants were analysed in the group to which they were randomized regardless of treatment received, but only where an outcome was recorded (Higgins 2005).

Results were presented as risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) around these estimates. RRs less than one were taken to demonstrate a favourable outcome of the intervention of interest, and these are presented to the left of the line of no effect.

For those comparisons in which there were data from more than one trial we assessed heterogeneity by visually inspecting forest plots, calculating an I2 statistic, and carrying out a chi square test for heterogeneity. If heterogeneity was detected we undertook a subgroup analysis, grouping trials according to drug regimen and follow up time (1 week vs 2 weeks vs 3 weeks vs 4 weeks) in order to explore causes of heterogeneity. If heterogeneity was not detected we pooled results from trials in a fixed‐effect meta‐analysis.

Results

Description of studies

Trial selection

Of the 79 trials identified and included in our trials register, 57 were excluded (see 'Characteristics of excluded studies') and 22 met the inclusion criteria (see 'Characteristics of included studies'). All trials were identified from published literature. One ongoing study, Naeyaert ongoing has also been identified.

Trial location

Nineteen of the 22 included studies were conducted in resource‐poor countries, although one, Schultz 1990, was a large multicentre trial involving eight centres (four sexually transmitted disease clinics, two dermatology clinics, and two family practice clinics), with one of the family practice centres in Mexico and the others in the USA. Of the other three trials, one was carried out in the USA (Hansen 1986) and two in Italy (Amerio 2003; Biele 2006).

Participants

Three trials included only adults (Chouela 1999; Amerio 2003; Biele 2006), six included only children (Maggi 1986; Schenone 1986; Taplin 1990; Avila‐Romay 1991; Brooks 2002; Singalavanija 2003); and the other 13 included both adults and children. The total number of participants randomized in the 22 trials was 2676; all had a clinical diagnosis of scabies, with a subset of 903 identified as having their diagnosis confirmed parasitologically.

Interventions

The effectiveness of the following drugs was tested: topical benzyl benzoate; crotamiton; decamethrin; lindane; permethrin; synergized natural pyrethrins; sulfur; and oral ivermectin. Eighteen trials compared one drug with at least one other drug, one trial compared ivermectin against placebo, three trials compared different drug treatment regimens, and one trial compared two different vehicles for the same drug. No randomized controlled trials investigating malathion were identified.

Clinicians and drug companies recommended treatment of family members and close contacts at the same time as cases, to improve cure rates and reduce reinfection (Taplin 1986). None of the trials tested this hypothesis. Close and family contacts in both intervention and control groups were treated, however, in all but six trials (Hansen 1986; Maggi 1986; Amer 1992; Macotela‐Ruiz 1993; Amerio 2003; Biele 2006).

Five trials stipulated that a bath or shower should be taken before treatment (Gulati 1978; Schenone 1986; Taplin 1990; Avila‐Romay 1991; Bachewar 2009); and ten trials stipulated that participants should change and wash their linen after treatment (Avila‐Romay 1991; Glaziou 1993; Chouela 1999; Usha 2000; Madan 2001; Nnoruka 2001; Brooks 2002; Singalavanija 2003; Zargari 2006; Ly 2009).

Dosing and regimen

Benzyl benzoate

The strength of the topical benzyl benzoate solution varied with three trials using 10% (Glaziou 1993; Brooks 2002; Biele 2006), one trial using 12.5% (Ly 2009) and three trials using 25% (Gulati 1978; Nnoruka 2001; Bachewar 2009). The treatment regimen was different in each trial: it was applied once and left overnight in Brooks 2002; applied twice, 12 hours apart in Glaziou 1993; applied twice and left overnight on two consecutive nights in Bachewar 2009; applied three times, 12 hours apart in Gulati 1978; applied on five consecutive days in Biele 2006; and a single application was left for 72 hours in Nnoruka 2001. Ly 2009 included two benzyl benzoate intervention groups, one in which the drug was applied once and left for 24 hours, and another in which the drug was applied twice, 24 hours apart, left in each case for 24 hours.

Crotamiton

A 10% topical preparation was used in two trials (Taplin 1990; Amer 1992). It was applied overnight on two consecutive nights in Amer 1992, and was applied once overnight in Taplin 1990.

Decamethrin

Schenone 1986 compared 0.02% decamethrin lotion applied daily for two days repeated on two more days a week later with 0.02% decamethrin lotion applied daily for four consecutive days.

Lindane

Each lindane trial used a 1% topical preparation, except for Singalavanija 2003, which used a 0.3% preparation. The number of applications ranged from one (Hansen 1986; Maggi 1986; Taplin 1986; Schultz 1990; Chouela 1999) to two (Amer 1992; Zargari 2006) to seven (Singalavanija 2003). Maggi 1986 compared a single application of lindane left on for four days, washed off and then repeated after a week with a single one‐hour application of lindane, repeated after a week.

Permethrin

A 5% topical preparation was used in each permethrin trial. The number of applications ranged from one (Schultz 1990; Taplin 1990; Usha 2000; Bachewar 2009) to two (Amer 1992; Zargari 2006) to two consecutive overnight applications repeated after 14 days (Amerio 2003).

Synergized natural pyrethrins

A 0.16% topical preparation of natural pyrethrins synergized with pyperonil butoxide was used in Amerio 2003, applied on two successive nights and repeated 14 days later. In Biele 2006, a 0.165% preparation was applied on three consecutive days.

Sulfur

Two of the three sulfur trials used a 10% topical preparation (Avila‐Romay 1991; Singalavanija 2003). In the third trial, Gulati 1978, the strength of the preparation was not stated. Avila‐Romay 1991 compared sulfur in cold cream with sulfur in pork fat; both medications were applied nightly for three nights and then once three nights later. Singalavanija 2003 applied the sulfur on seven consecutive nights. Gulati 1978 applied sulfur once in the morning, once in the evening, and once again the next morning; treatment was repeated after 10 days if lesions persisted.

Ivermectin

The oral dose of ivermectin varied from a 100 µg/kg bodyweight (Glaziou 1993) to 200 µg/kg bodyweight (Macotela‐Ruiz 1993; Usha 2000; Madan 2001; Nnoruka 2001; Brooks 2002; Bachewar 2009). The Chouela 1999 and Ly 2009 trials used an ivermectin dose between 150 µg/kg and 200 µg/kg bodyweight. Each trial gave a single dose.

Length of follow up

Follow up ranged from seven days to one month. In 11 trials it was possible to extract outcome data at 28 to 31 days after treatment (Hansen 1986; Taplin 1986; Schultz 1990; Taplin 1990; Amer 1992; Glaziou 1993; Madan 2001; Nnoruka 2001; Amerio 2003; Singalavanija 2003; Biele 2006). Follow up was at 21 days in two trials (Schenone 1986; Brooks 2002); 14 to 15 days in six trials (Gulati 1978; Maggi 1986; Chouela 1999; Usha 2000; Zargari 2006; Ly 2009); and seven to 10 days in the remaining three trials (Avila‐Romay 1991; Macotela‐Ruiz 1993; Bachewar 2009).

Outcome measures

The review's primary outcome measure (treatment failure) was reported in 21 of the 22 trials. Six of these 21 trials reported treatment failure in both clinically diagnosed cases and in microscopically confirmed cases (Schultz 1990; Taplin 1990; Amer 1992; Amerio 2003; Singalavanija 2003; Biele 2006); the other 13 trials reported treatment failure in clinically diagnosed cases who may or may not have been confirmed microscopically. Seven trials reported the secondary outcome measure (itch persistence) in addition to treatment failure (Hansen 1986; Schultz 1990; Taplin 1990; Brooks 2002; Amerio 2003; Singalavanija 2003; Biele 2006). Itch persistence alone was reported by Maggi 1986. Adverse events were reported as an outcome in all trials except Gulati 1978 and Maggi 1986. The seven trials that reported on itch varied in their methods to assess this outcome:

Hansen 1986: did not report on the method used.

Maggi 1986: participants reported on itch using a three‐point scale ("absent", "moderate", and "intense") before and after treatment; numbers in each category were reported.

Schultz 1990: participants reported the presence or absence of itch before and after treatment; numbers in each category were reported.

Taplin 1990: participants were reported as either having presence or absence of itch; no further details of assessment were given.

Brooks 2002: participants described itch severity on a visual analogue scale before and after treatment; mean scores were reported along with the number of participants with absence of night‐time itch.

Amerio 2003 and Biele 2006: participants reported on itch using a five‐point scale (from 0 = "no itch" to 4 = "severe itch") before and after treatment; mean scores were reported along with the number of participants with complete relief from itching.

Singalavanija 2003: participants were divided into those who reported a decrease or absence of itch, and those who reported no improvement.

Sources of support

Seven trials stated that funding or support had been provided by drug companies (Taplin 1986; Schultz 1990; Taplin 1990; Glaziou 1993; Usha 2000; Amerio 2003; Zargari 2006).

Background prevalence

Fifteen trial reports did not state the background prevalence of scabies. In the four trials where prevalence was stated, it ranged from 9% in India (Gulati 1978) to 14% among children in a boarding school in Chile (Schenone 1986) to 36% in French Polynesia (Glaziou 1993) to 67% in Panama (Taplin 1990).

Risk of bias in included studies

See Table 16 for a summary assessment and the 'Characteristics of included studies' for details.

1. Quality assessment.

| Trial | Allocation sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Blinding | Inclusiona |

| Amer 1992 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Adequate |

| Amerio 2003 | Adequate | Adequate | Investigators | Adequate |

| Avila‐Romay 1991 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Adequate |

| Bachewar 2009 | Adequate | Unclear | None | Inadequate |

| Biele 2006 | Adequate | Unclear | Investigators | Adequate |

| Brooks 2002 | Adequate | Unclear | Investigators | Inadequate |

| Chouela 1999 | Unclear | Unclear | Described as "double blind"; participants blinded | Adequate |

| Glaziou 1993 | Unclear | Unclear | Outcomes assessor | Adequate |

| Gulati 1978 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Adequate |

| Hansen 1986 | Unclear | Unclear | "Single blind", unclear who was blinded | Adequate |

| Ly 2009 | Adequate | Unclear | None | Adequate |

| Macotela‐Ruiz 1993 | Unclear | Unclear | Participant and outcomes assessor | Adequate |

| Madan 2001 | Unclear | Unclear | Outcomes assessor | Inadequate |

| Maggi 1986 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Adequate |

| Nnoruka 2001 | Adequate | Unclear | Unclear | Adequate |

| Schenone 1986 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Adequate |

| Schultz 1990 | Unclear | Adequate | Outcomes assessor | Adequate |

| Singalavanija 2003 | Adequate | Unclear | Unclear | Inadequate |

| Taplin 1986 | Unclear | Adequate | Investigators | Adequate |

| Taplin 1990 | Unclear | Adequate | Investigators | Adequate |

| Usha 2000 | Adequate | Adequate | None | Adequate |

| Zargari 2006 | Unclear | Adequate | Investigators and participants | Adequate |

aInclusion of randomized participants in analysis.

Generation of allocation sequence

Eight trials described an adequate method of generating a random allocation sequence: by computer in Usha 2000, Brooks 2002, Amerio 2003, Biele 2006 and Bachewar 2009; and by random‐number table in Nnoruka 2001, Singalavanija 2003 and Ly 2009. The method was unclear in the other trials.

Allocation concealment

Six trials reported adequate allocation concealment: by phone call to third party‐based procedure in Amerio 2003; by use of identical coded medication containers in Taplin 1986, Schultz 1990, Taplin 1990, and Zargari 2006; and the author of Usha 2000 confirmed that the allocation was by a third party, not the investigator. The remaining trials had methods of concealment that were either unclear or not reported.

Blinding

Twelve trials reported blinding. In two of these trials both the investigators or outcome assessors and the participants were described as blinded (Macotela‐Ruiz 1993; Zargari 2006), and in eight trials the investigators or outcome assessors alone were described as blinded (Taplin 1986; Schultz 1990; Taplin 1990; Glaziou 1993; Madan 2001; Brooks 2002; Amerio 2003; Biele 2006). Chouela 1999 described the participants as blinded but also reported the trial as "double blind". Hansen 1986 described the trial as "single blind", but it is unclear who was blinded.

Inclusion of randomized participants in the analysis

Ten trials included all randomized participants in the analysis with no mention of losses to follow up. The completeness of follow up was greater than 80% (ie adequate) in eight trials (Hansen 1986; Taplin 1986; Schultz 1990; Taplin 1990; Macotela‐Ruiz 1993; Chouela 1999; Zargari 2006; Ly 2009). The remaining four trials reported completeness of follow up less than 80% (Brooks 2002 − 27% lost to follow up, Madan 2001 − 25% lost to follow up, Singalavanija 2003 − 32% lost to follow up; Bachewar 2009 ‐ 22% lost to follow up).

Effects of interventions

1. Ivermectin

Only one trial assessed the effectiveness against placebo, while eight trials compared it with another drug.

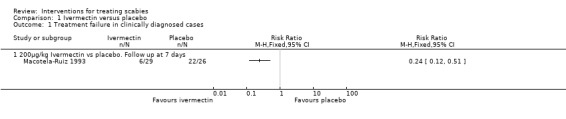

1.1. Versus placebo (55 participants, 1 trial)

Macotela‐Ruiz 1993 compared 200 µg/kg bodyweight oral ivermectin with placebo.

Treatment failure in clinically diagnosed cases

Macotela‐Ruiz 1993 reported fewer treatment failures in the ivermectin group at seven days (RR 0.24, 95% CI 0.12 to 0.51; 55 participants, Analysis 1.1). Figure 1.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Ivermectin versus placebo, Outcome 1 Treatment failure in clinically diagnosed cases.

1.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Ivermectin versus placebo, outcome: 1.1 Treatment failure in clinically diagnosed cases.

Adverse events.

None were reported.

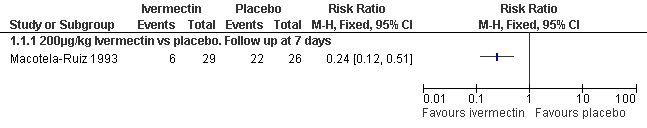

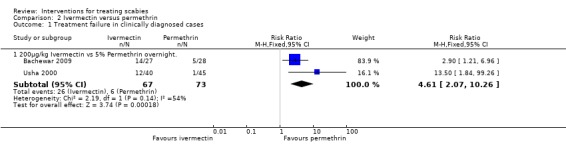

1.2. Versus permethrin (153 participants, 2 trials)

Usha 2000 and Bachewar 2009 both compared 200 µg/kg bodyweight oral ivermectin with 5% topical permethrin cream.

Treatment failure in clinically diagnosed cases

Usha 2000 reported more treatment failures in the ivermectin group at two weeks (RR 13.50, 95% CI 1.84 to 99.26; 85 participants), as did Bachewar 2009 at one week follow up (RR 2.90, 95% CI 1.21 to 6.96; 55 participants, Analysis 2.1). Significant heterogeneity was not detected and the trials' combined estimate showed more treatment failures with ivermectin (RR 4.61, 95% CI 2.07 to 10.26, fixed‐effect model; 140 participants). Figure 2.

2.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Ivermectin versus permethrin, outcome: 2.1 Treatment failure in clinically diagnosed cases.

Adverse events

Three of 43 participants in the ivermectin group in the Usha 2000 trial reported aggravation of symptoms. No adverse events were reported in Bachewar 2009 (see Table 17).

2. Adverse events.

| Comparison | Trial | Adverse event | Intervention | n/Na | Intervention | n/Na |

| Ivermectin vs placebo | Macotela‐Ruiz 1993 | None recorded | Ivermectin | — | Placebo | — |

| Ivermectin vs permethrin | Usha 2000 | Aggravation of symptoms | Ivermectin | 3/43 | Permethrin | 0/45 |

| Bachewar 2009 | None recorded | Ivermectin | — | Permethrin | — | |

| Ivermectin vs lindane | Chouela 1999 | Headache | Ivermectin | 1/26 | Lindane | 6/27 |

| Headache | Ivermectin | 1/26 | Lindane | 0/27 | ||

| Hypotension | Ivermectin | 1/26 | Lindane | 0/27 | ||

| Abdominal pain | Ivermectin | 1/26 | Lindane | 0/27 | ||

| Vomiting | Ivermectin | 1/26 | Lindane | 0/27 | ||

| Madan 2001 | Severe headache | Ivermectin | 1/100 | Lindane | 0/100 | |

| Ivermectin vs benzyl benzoate | Glaziou 1993 | Mild increase in pruritus | Ivermectin | 0/23 | Benzyl benzoate | 5/21 |

| Nnoruka 2001 | Pruritus and irritation | Ivermectin | 0/29 | Benzyl benzoate | 7/29 | |

| Brooks 2002 | Pustular rash | Ivermectin | 3/43 | Benzyl benzoate | 0/37 | |

| Cellulitis | Ivermectin | 1/43 | Benzyl benzoate | 0/37 | ||

| Burning or stinging | Ivermectin | 0/43 | Benzyl benzoate | 6/37 | ||

| Dermatitis | Ivermectin | 0/43 | Benzyl benzoate | 6/37 | ||

| Bachewar 2009 | None recorded | Ivermectin | — | Benzyl benzoate | — | |

| Ly 2009 | Abdominal pain | Ivermectin | 5/65 | Benzyl benzoate | 0/116 | |

| Mild diarrhoea | Ivermectin | 2/65 | Benzyl benzoate | 0/116 | ||

| Irritant dermatitis | Ivermectin | 0/65 | Benzyl benzoate | 30/116 | ||

| Permethrin vs crotamiton | Taplin 1990 | Worsening of symptoms | Permethrin | 0/48 | Crotamiton | 10/48 |

| Amer 1992 | None recorded | Permethrin | — | Crotamiton | — | |

| Permethrin vs lindane | Hansen 1986 | Mild burning, stinging, or itching | Permethrin | 5/49 | Lindane | 5/50 |

| Taplin 1986 | None recorded | Permethrin | — | Lindane | — | |

| Schultz 1990 | Burning/stinging | Permethrin | 23/234 | Lindane | 12/233 | |

| Pruritus | Permethrin | 15/234 | Lindane | 17/233 | ||

| Erythema | Permethrin | 5/234 | Lindane | 3/233 | ||

| Tingling | Permethrin | 4/234 | Lindane | 5/233 | ||

| Rash | Permethrin | 2/234 | Lindane | 2/233 | ||

| Diarrhoea | Permethrin | 1/234 | Lindane | 1/233 | ||

| Persistent excoriation | Permethrin | 1/234 | Lindane | 0/233 | ||

| Contact dermatitis | Permethrin | 0/234 | Lindane | 1/233 | ||

| Phemphigus | Permethrin | 0/234 | Lindane | 1/233 | ||

| Papular rash | Permethrin | 0/234 | Lindane | 1/233 | ||

| Amer 1992 | None recorded | Permethrin | — | Lindane | — | |

| Zargari 2006 | Skin irritation | Permethrin | 2/59 | Lindane | 1/58 | |

| Permethrin versus benzyl benzoate | Bachewar 2009 | None recorded | Permethrin | — | Benzyl benzoate | — |

| Permethrin vs synergized natural pyrethrins | Amerio 2003 | Secondary skin infection | Permethrin | 10/20 | Synergized pyrethrins | 2/20 |

| Crotamiton vs lindane | Amer 1992 | None recorded | Lindane | — | Crotamiton | — |

| Lindane vs sulfur | Singalavanija 2003 | Foul odour | Lindane | 3/50 | Sulfur | 10/50 |

| Burning | Lindane | 6/50 | Sulfur | 2/50 | ||

| Erythema | Lindane | 5/50 | Sulfur | 2/50 | ||

| Benzyl benzoate vs sulfur | Gulati 1978 | None recorded | Benzyl benzoate | — | Sulfur | — |

| Benzyl benzoate vs synergized natural pyrethrins | Biele 2006 | Skin irritation and burning sensations | Benzyl benzoate | 22/120 | Synergized pyrethrins | 3/120 |

| Lindane: short vs long application | Maggi 1986 | None recorded | Lindane (short course) | — | Lindane (long course) | — |

| Decamethrin: 2‐day + 2‐day vs 4‐day application | Schenone 1986 | Moderate skin hotness | Decamethrin (both regimens) | 15/127 | ||

| Sulfur: pork fat vehicle vs cold cream vehicle | Avila‐Romay 1991 | Pruritus | Sulfur/salicylic acid in pork fat | 32/53 | Sulfur in cold cream | 18/58 |

| Xerosis | Sulfur/salicylic acid in pork fat | 18/53 | Sulfur in cold cream | 14/58 | ||

| Burning sensations | Sulfur/salicylic acid in pork fat | 9/53 | Sulfur in cold cream | 6/58 | ||

| Keratosis pilaris | Sulfur/salicylic acid in pork fat | 8/53 | Sulfur in cold cream | 0/58 | ||

| Erythema | Sulfur/salicylic acid in pork fat | 1/53 | Sulfur in cold cream | 6/58 | ||

| Keratosis follicularis | 0/53 | Sulfur in cold cream | 1/58 | |||

aNo. participants reporting event/total no. participants.

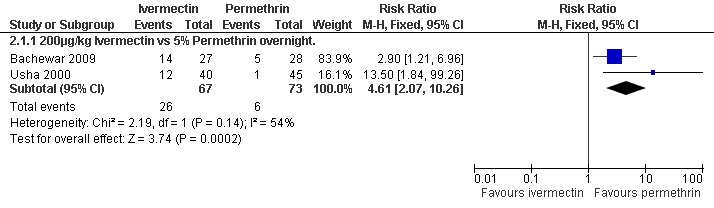

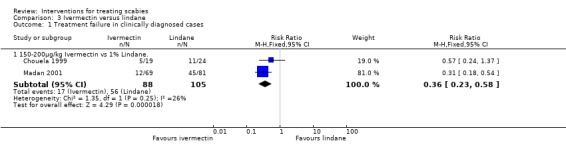

1.3. Versus lindane (253 participants, 2 trials)

Chouela 1999 compared 150 µg/kg bodyweight oral ivermectin with 1% topical lindane, while Madan 2001 compared 200 µg/kg ivermectin with 1% lindane.

Treatment failure in clinically diagnosed cases

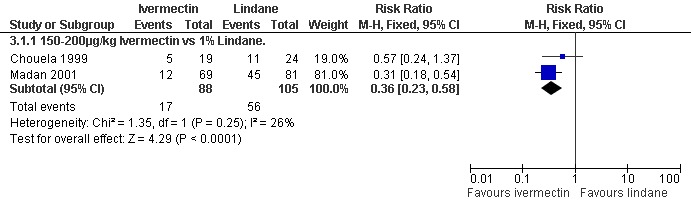

Chouela 1999 found no significant difference between the groups at 15 days (43 participants), while at four weeks Madan 2001 found that treatment failures were reduced in the ivermectin group (RR 0.31, 95% CI 0.18 to 0.54; 150 participants, Analysis 3.1). Heterogeneity was not detected and the trials' combined estimate showed a benefit of ivermectin over lindane (RR 0.36, 95% CI 0.23 to 0.58, fixed‐effect model; 193 participants). Figure 3.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Ivermectin versus lindane, Outcome 1 Treatment failure in clinically diagnosed cases.

3.

Forest plot of comparison: 3 Ivermectin versus lindane, outcome: 3.1 Treatment failure in clinically diagnosed cases.

Adverse events

See Table 17. Chouela 1999 reported adverse events in 4/26 participants in the ivermectin group (headache, hypotension, abdominal pain, and vomiting) and in 6/37 participants in the lindane group (headache). Madan 2001 reported an adverse event in 1/100 participants in the ivermectin group (severe headache); there were none in the lindane group.

1.4. Versus benzyl benzoate (462 participants, 5 trials)

Brooks 2002 compared 200 µg/kg bodyweight oral ivermectin with 10% topical benzyl benzoate. Glaziou 1993 compared 100 µg/kg bodyweight ivermectin with 10% benzyl benzoate. Nnoruka 2001 and Bachewar 2009 compared 200 µg/kg bodyweight ivermectin with 25% benzyl benzoate. Ly 2009 compared 150 to 200 µg/kg bodyweight ivermectin with 12.5% benzyl benzoate.

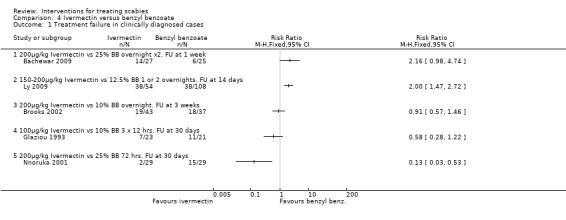

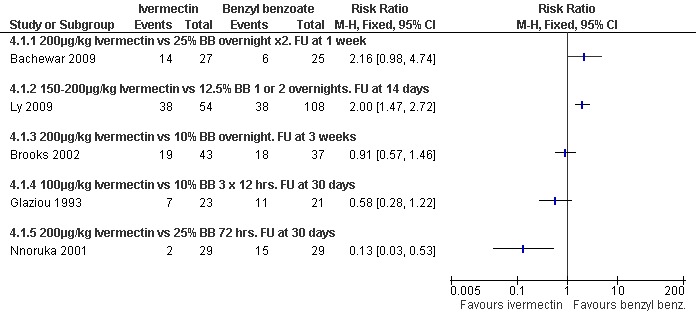

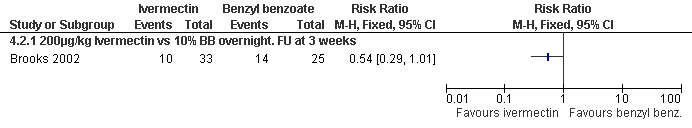

Treatment failure in clinically diagnosed cases

See Analysis 4.1. No significant difference between the two groups was found in Bachewar 2009 at one week follow up (52 participants). After 14 days Ly 2009 found a significant difference in favour of benzyl benzoate compared with ivermectin (RR 2.00, 95% CI 1.47 to 2.72; 162 participants). No significant difference between the two groups was found in Brooks 2002 at three weeks (80 participants) or by Glaziou 1993 at 30 days (44 participants). At 30 days Nnoruka 2001 found a significant difference in favour of ivermectin (RR 0.13, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.53; 58 participants). Heterogenity was detected between the trials (Chi2 = 27.97, df = 4, P < 0.0001; I2 = 86%; see Figure 4 for forest plot). The differences in drug regimen and length of follow up that exist between the five trials may explain this heterogeneity.

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Ivermectin versus benzyl benzoate, Outcome 1 Treatment failure in clinically diagnosed cases.

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 4 Ivermectin versus benzyl benzoate, outcome: 4.1 Treatment failure in clinically diagnosed cases.

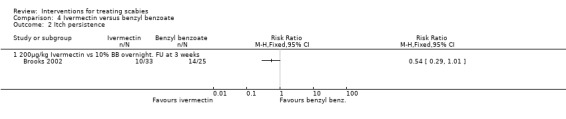

Itch persistence

See Analysis 4.2. Brooks 2002 found no significant difference in the number of participants who reported night‐time itch at three weeks (58 participants). Figure 5.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Ivermectin versus benzyl benzoate, Outcome 2 Itch persistence.

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 4 Ivermectin versus benzyl benzoate, outcome: 4.2 Itch persistence.

Adverse events

See Table 17. Brooks 2002 reported adverse events in 4/43 participants in the ivermectin group (pustular rash, cellulitis) and in 12/37 participants in the benzyl benzoate group (burning or stinging, dermatitis). Glaziou 1993 and Nnoruka 2001 reported adverse events only in the benzyl benzoate group: 5/21 participants (mild increase in pruritus) in Glaziou 1993; and 7/29 participants (pruritus and irritation) in Nnoruka 2001. Ly 2009 reported adverse events in 7/65 participants in the ivermectin group (abdominal pain, diarrhoea) and in 30/116 participants in the benzyl benzoate groups. Bachewar 2009 reported no adverse events.

2. Permethrin

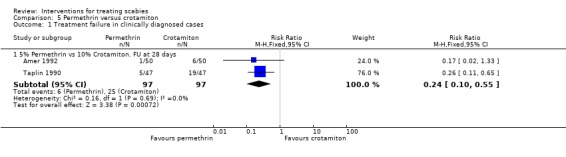

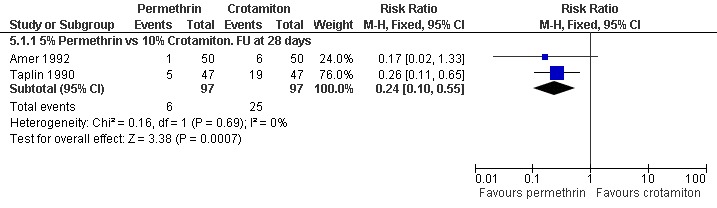

2.1. Versus crotamiton (196 participants, 2 trials)

Two trials compared 5% permethrin with 10% crotamiton (Taplin 1990; Amer 1992). In Taplin 1990 the drugs were applied for 8 to 10 hours, whereas in Amer 1992 the drugs were applied overnight on two consecutive days.

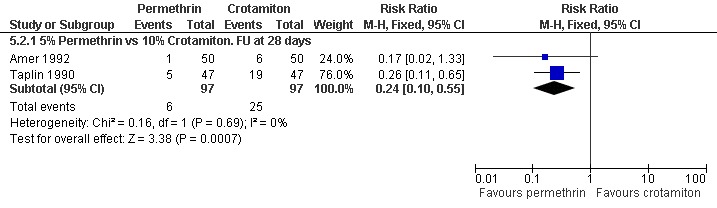

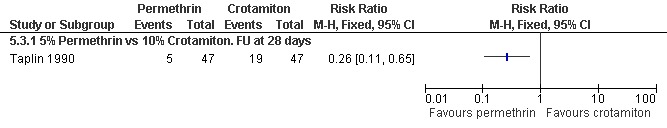

Treatment failure

See Analysis 5.1 and Analysis 5.2. Participants in both trials had their scabies clinically diagnosed and microscopically confirmed. The comparative treatment failure rates described for clinically diagnosed cases therefore apply equally to microscopically diagnosed cases in these trials. Taplin 1990 found that treatment failure was reduced in the permethrin group after 28 days (RR 0.26, 95% CI 0.11 to 0.65; 94 participants, Analysis 5.1.3). Amer 1992 found no significant difference in outcome between the groups after 28 days (100 participants). Heterogeneity was not detected and a combined estimate showed a benefit of permethrin over crotamiton (RR 0.24, 95% CI 0.10 to 0.55, fixed‐effect analysis; 194 participants). Figure 6 and Figure 7.

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Permethrin versus crotamiton, Outcome 1 Treatment failure in clinically diagnosed cases.

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Permethrin versus crotamiton, Outcome 2 Treatment failure in microscopically diagnosed cases.

6.

Forest plot of comparison: 5 Permethrin versus crotamiton, outcome: 5.1 Treatment failure in clinically diagnosed cases.

7.

Forest plot of comparison: 5 Permethrin versus crotamiton, outcome: 5.2 Treatment failure in microscopically diagnosed cases.

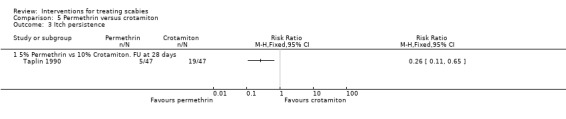

Itch persistence

See Analysis 5.3. Permethrin reduced the number of participants with itch persistence in Taplin 1990 (RR 0.26, 95% CI 0.11 to 0.65; 94 participants). Figure 8.

5.3. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Permethrin versus crotamiton, Outcome 3 Itch persistence.

8.

Forest plot of comparison: 5 Permethrin versus crotamiton, outcome: 5.3 Itch persistence.

Adverse events

See Table 17. Taplin 1990 reported no adverse events in the permethrin group, but did report adverse events in 10/47 participants in the crotamiton group (worsening of symptoms). Amer 1992 reported no adverse events.

2.2. Versus lindane (835 participants, 5 trials)

Five trials compared 5% topical permethrin with 1% topical lindane (Hansen 1986; Taplin 1986; Schultz 1990; Amer 1992; Zargari 2006).

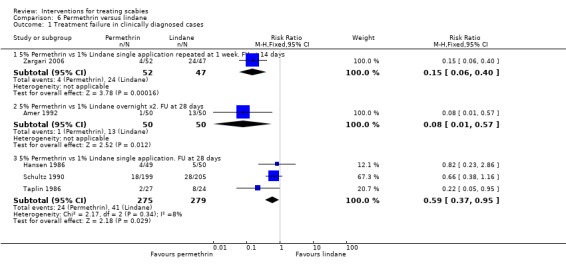

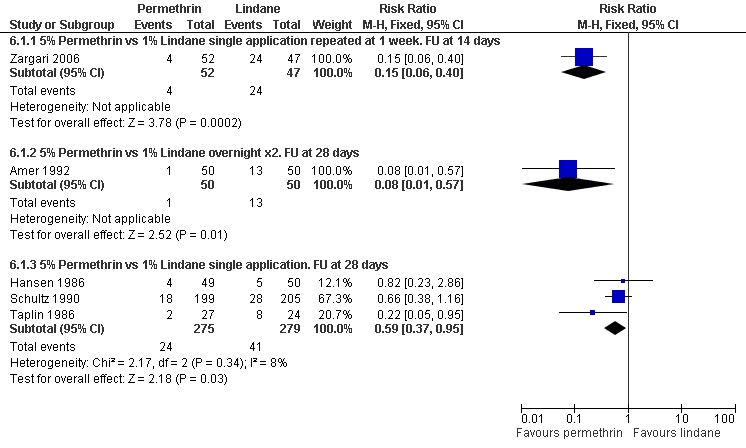

Treatment failure in clinically diagnosed cases

See Analysis 6.1. Zargari 2006 reported fewer treatment failures in the permethrin group after 14 days (RR 0.15, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.40; 99 participants). At 28 days Amer 1992 found two consecutive overnight applications of permethrin to be superior to two consecutive overnight applications of lindane (RR 0.08, 95% CI 0.01 to 0.57; 100 participants). Three trials compared a single application of permethrin with a single application of lindane, with follow up at 28 days (Hansen 1986, Schultz 1990 and Taplin 1986). No benefit was found for either treatment by Hansen 1986 (28 days, 99 participants) or Schultz 1990 (28 +/‐ 7 days, 404 participants), whereas Taplin 1986 found permethrin to be superior (RR 0.22, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.95; 51 participants).

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Permethrin versus lindane, Outcome 1 Treatment failure in clinically diagnosed cases.

Heterogenity was detected between the results of the five studies (Chi2 = 11.83, df = 4, P = 0.02; I2 = 66%; see Figure 9 for forest plot) so the trials were grouped by drug regimen and length of follow up in order to explore causes of heterogeneity. The pooled effect for the three trials sharing the same drug regimen (single application) and length of follow up (four weeks) showed a significant effect in favour of permethrin (RR 0.59, 95% CI 0.37 to 0.95, fixed‐effect model; 554 participants). Statistical heterogeneity was not detected in this group of three trials.

9.

Forest plot of comparison: 6 Permethrin versus lindane, outcome: 6.1 Treatment failure in clinically diagnosed cases.

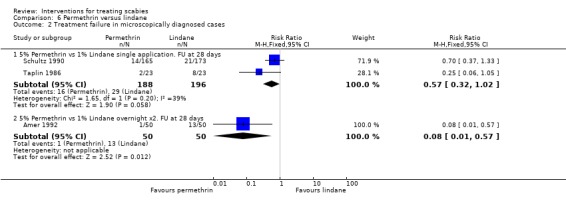

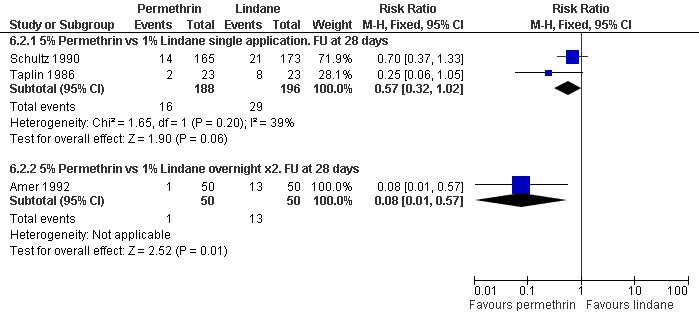

Treatment failure in microscopically confirmed cases

See Analysis 6.2. Two consecutive overnight applications of permethrin was found to be superior to two consecutive overnight applications of lindane after 28 days in Amer 1992 (RR 0.08, 95% CI 0.01 to 0.57; 100 participants). Taplin 1986 (46 participants) and Schultz 1990 (338 participants) both compared single applications of permethrin and lindane with follow up at 28 days. Neither trial showed a significant difference between the interventions. Figure 10.

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Permethrin versus lindane, Outcome 2 Treatment failure in microscopically diagnosed cases.

10.

Forest plot of comparison: 6 Permethrin versus lindane, outcome: 6.2 Treatment failure in microscopically diagnosed cases.

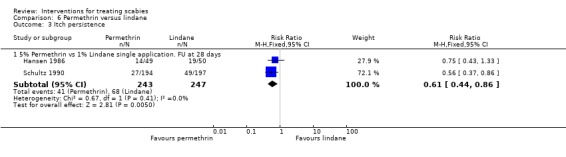

Itch persistence

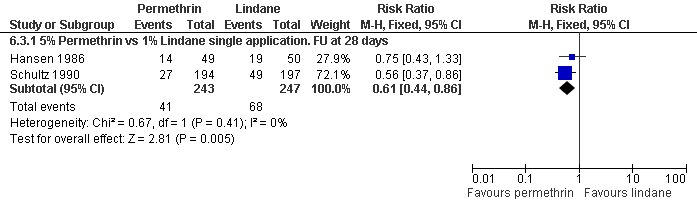

See Analysis 6.3. The two trials that reported on itch persistence found different effects: Hansen 1986 found no significant difference between the two interventions after 28 days (99 participants), whereas Schultz 1990 found permethrin to be superior after 28 +/‐ 7 days (RR 0.56, 95% CI 0.37 to 0.86; 391 participants). Heterogeneity was not detected and a combined estimate showed permethrin to be superior (RR 0.61, 95% CI 0.44 to 0.86, fixed effects model; 490 participants). Figure 11.

6.3. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Permethrin versus lindane, Outcome 3 Itch persistence.

11.

Forest plot of comparison: 6 Permethrin versus lindane, outcome: 6.3 Itch persistence.

Adverse events

See Table 17. Hansen 1986 recorded mild burning, stinging, or itching in both groups (5/49 participants in the permethrin group, 5/50 participants in the lindane group). Schultz 1990 reported adverse events in 51/234 participants in the permethrin group (burning/stinging, pruritus, erythema, tingling, rash, diarrhoea, persistent excoriation) and in 43/233 participants in the lindane group (burning/stinging, pruritus, tingling, erythema, rash, papular rash, diarrhoea, contact dermatitis, phemphigus). Zargari 2006 reported skin irritation in both groups (2/59 participants in the permethrin group, 1/58 participant in the lindane group). Amer 1992 and Taplin 1986 both reported no adverse events.

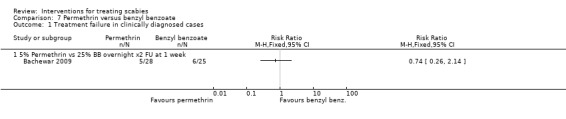

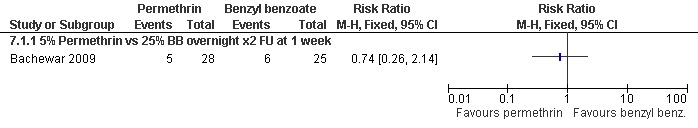

2.3 Versus benzyl benzoate (69 participants, 1 trial)

Treatment failure in clinically diagnosed cases

See Analysis 7.1. In Bachewar 2009 there was no significant difference in treatment failure between the two groups after one week (RR 0.74, 95% CI 0.26 to 2.14; 53 participants). Figure 12.

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Permethrin versus benzyl benzoate, Outcome 1 Treatment failure in clinically diagnosed cases.

12.

Forest plot of comparison: 7 Permethrin versus benzyl benzoate, outcome: 7.1 Treatment failure in clinically diagnosed cases.

Adverse events

No adverse events were reported in Bachewar 2009.

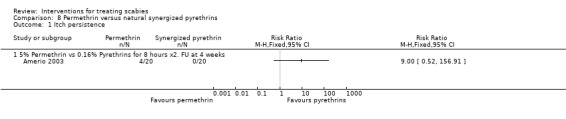

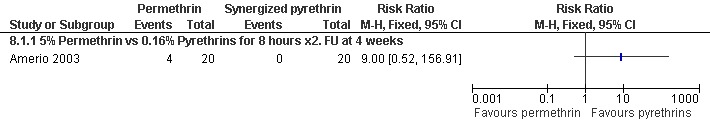

2.4. Versus synergized natural pyrethrins (40 participants, 1 trial)

Amerio 2003 compared 5% topical permethrin with topical 0.16% natural pyrethrins synergized with 1.65% pyperonil butoxide.

Treatment failure

All participants had their scabies both clinically diagnosed and microscopically confirmed. There were no treatment failures in either group after 28 days (40 participants).

Itch persistence

See Analysis 8.1.There was no significant difference in itch persistence between the two groups after 28 days (40 participants). Figure 13.

8.1. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Permethrin versus natural synergized pyrethrins, Outcome 1 Itch persistence.

13.

Forest plot of comparison: 8 Permethrin versus natural synergized pyrethrins, outcome: 8.1 Itch persistence.

Adverse events

See Table 17. Ten of the 20 participants in the permethrin group and two of the 20 participants in the synergized pyrethrin group were reported as having secondary skin infections requiring antibiotic treatment. It was not clear from the trial report whether this was considered an adverse event or rather a baseline characteristic.

3. Other drug comparisons

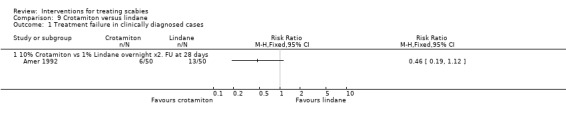

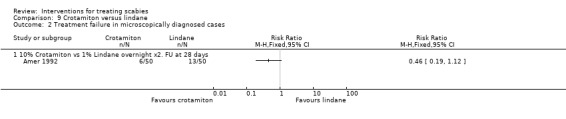

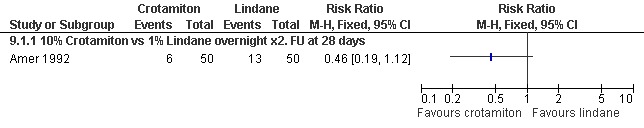

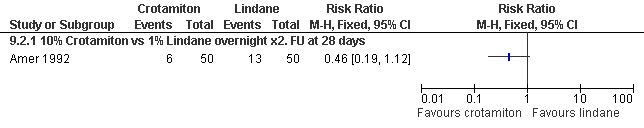

3.1. Crotamiton versus lindane (100 participants, 1 trial)

Amer 1992 compared 10% topical crotamiton with 1% topical lindane.

Treatment failure

See Analysis 9.1 and Analysis 9.2. All participants in Amer 1992 had their scabies both clinically diagnosed and microscopically confirmed. There was no significant difference in treatment failure between the two groups after 28 days (100 participants). Figure 14 and Figure 15.

9.1. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Crotamiton versus lindane, Outcome 1 Treatment failure in clinically diagnosed cases.

9.2. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Crotamiton versus lindane, Outcome 2 Treatment failure in microscopically diagnosed cases.

14.

Forest plot of comparison: 9 Crotamiton versus lindane, outcome: 9.1 Treatment failure in clinically diagnosed cases.

15.

Forest plot of comparison: 9 Crotamiton versus lindane, outcome: 9.2 Treatment failure in microscopically diagnosed cases.

Adverse events

None were reported.

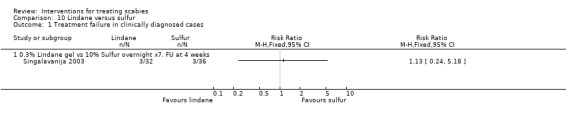

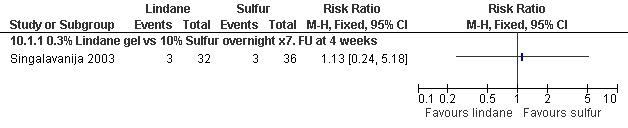

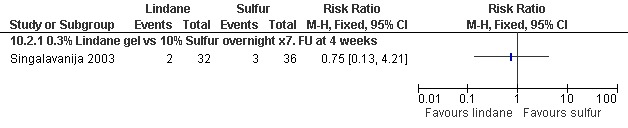

3.2. Lindane versus sulfur (100 participants, 1 trial)

Singalavanija 2003 compared 0.3% topical lindane with 10% topical sulfur.

Treatment failure in clinically diagnosed cases

See Analysis 10.1. There was no significant difference between the two groups after 28 days in Singalavanija 2003 (68 participants). Figure 16.

10.1. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Lindane versus sulfur, Outcome 1 Treatment failure in clinically diagnosed cases.

16.

Forest plot of comparison: 10 Lindane versus sulfur, outcome: 10.1 Treatment failure in clinically diagnosed cases.

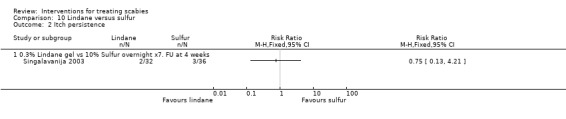

Itch persistence

See Analysis 10.2. There was no significant difference between the groups in the number of participants in whom itch persisted at 28 days (68 participants). Figure 17.

10.2. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Lindane versus sulfur, Outcome 2 Itch persistence.

17.

Forest plot of comparison: 10 Lindane versus sulfur, outcome: 10.2 Itch persistence.

Adverse events

See Table 17. The reported adverse events (foul odour, burning, erythema) occurred in the sulfur group (14/50 participants) and the lindane group (14/50 participants).

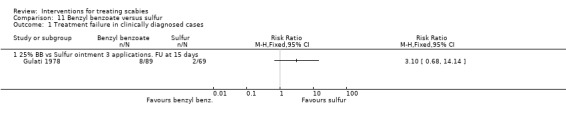

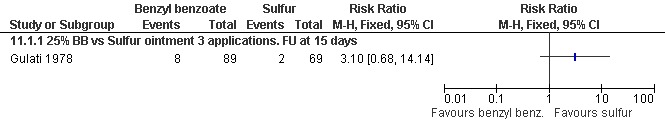

3.3. Benzyl benzoate versus sulfur (158 participants, 1 trial)

Gulati 1978 compared 25% topical benzyl benzoate with topical sulfur ointment.

Treatment failure in clinically diagnosed cases

See Analysis 11.1. There was no significant difference between the two groups after 15 days in Gulati 1978 (158 participants). Figure 18.

11.1. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Benzyl benzoate versus sulfur, Outcome 1 Treatment failure in clinically diagnosed cases.

18.

Forest plot of comparison: 11 Benzyl benzoate versus sulfur, outcome: 11.1 Treatment failure in clinically diagnosed cases.

Adverse events

None were reported.

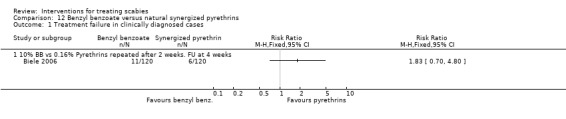

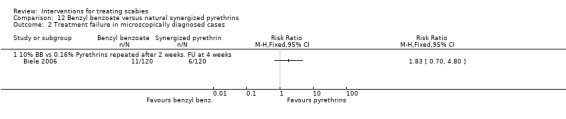

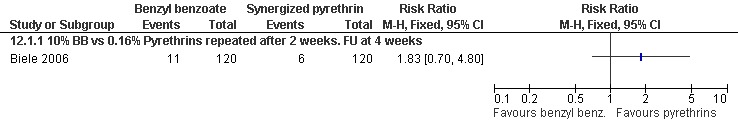

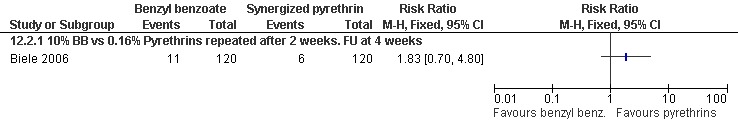

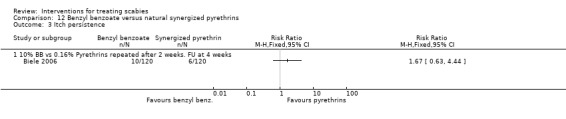

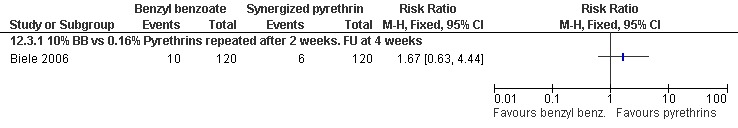

3.4. Benzyl benzoate versus synergized natural pyrethrins (240 participants, 1 trial)

Biele 2006 compared 10% topical benzyl benzoate with topical 0.165% natural pyrethrins synergized with 1.65% pyperonil butoxide.

Treatment failure

See Analysis 12.1 and Analysis 12.2. All participants had their scabies both clinically diagnosed and microscopically confirmed. There was no significant difference in treatment failure between the two groups after four weeks in Biele 2006 (240 participants). Figure 19 and Figure 20.

12.1. Analysis.

Comparison 12 Benzyl benzoate versus natural synergized pyrethrins, Outcome 1 Treatment failure in clinically diagnosed cases.

12.2. Analysis.

Comparison 12 Benzyl benzoate versus natural synergized pyrethrins, Outcome 2 Treatment failure in microscopically diagnosed cases.

19.

Forest plot of comparison: 12 Benzyl benzoate versus natural synergized pyrethrins, outcome: 12.1 Treatment failure in clinically diagnosed cases.

20.

Forest plot of comparison: 12 Benzyl benzoate versus natural synergized pyrethrins, outcome: 12.2 Treatment failure in microscopically diagnosed cases.

Itch persistence

See Analysis 12.3. There was no significant difference in itch persistence between the two groups after four weeks (240 participants). Figure 21.

12.3. Analysis.

Comparison 12 Benzyl benzoate versus natural synergized pyrethrins, Outcome 3 Itch persistence.

21.

Forest plot of comparison: 12 Benzyl benzoate versus natural synergized pyrethrins, outcome: 12.3 Itch persistence.

Adverse events

Twenty‐two of the 120 participants in the benzyl benzoate group and three of the 120 participants in the synergized natural pyrethrins group experienced skin irritation and burning sensations after drug application (see Table 17).

4. Length of treatment comparisons

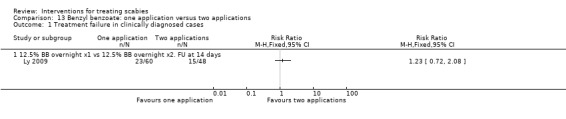

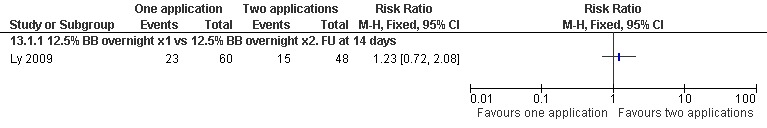

4.1. Benzyl benzoate: one overnight application versus two overnight applications (116 participants, 1 trial)

Treatment failure in clinically diagnosed cases.

There was no significant difference in treatment failure between the two groups after 14 days in Ly 2009 (108 participants, Analysis 13.1). Figure 22.

13.1. Analysis.

Comparison 13 Benzyl benzoate: one application versus two applications, Outcome 1 Treatment failure in clinically diagnosed cases.

22.

Forest plot of comparison: 13 Benzyl benzoate: one application versus two applications, outcome: 13.1 Treatment failure in clinically diagnosed cases.

Adverse events

Irritant dermatitis was reported in 30 out of 116 participants (see Table 17).

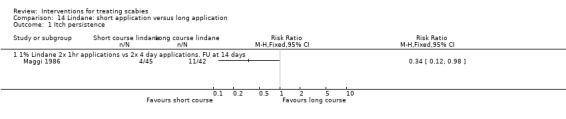

4.2. Lindane: short application versus long application (87 participants, 1 trial)

Treatment failure

Maggi 1986 did not assess this outcome measure.

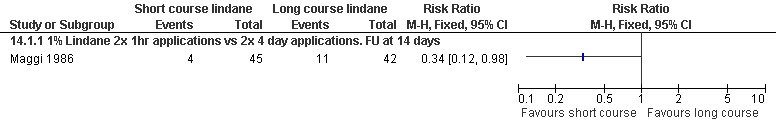

Itch persistence

A short application of lindane reduced itch persistence at 14 days (RR 0.34, 95% CI 0.12 to 0.98; 87 participants, Analysis 14.1). However, the trial authors did suggest that the pruritus experienced by the participants could have been due to a lindane‐associated contact dermatitis. Figure 23.

14.1. Analysis.

Comparison 14 Lindane: short application versus long application, Outcome 1 Itch persistence.

23.

Forest plot of comparison: 14 Lindane: short application versus long application, outcome: 14.1 Itch persistence.

Adverse events

None other than pruritus (see above) were reported.

4.3. Decamethrin: two‐day plus two‐day application versus four‐day application (127 participants, 1 trial)

Treatment failure in clinically diagnosed cases.

There were no treatment failures in either group in Schenone 1986 after 21 days: 0/53 treatment failures in the two‐plus‐two‐day group; and 0/74 treatment failures in the four‐day group. Five participants in each group received a second treatment at seven days due to the presence of active lesions. This second treatment consisted of two applications of 0.02% decamethrin on consecutive days.

Adverse events

Fifteen of 127 participants experienced "moderate skin hotness" after application of decamethrin (see Table 17).

5. Drug vehicle comparisons

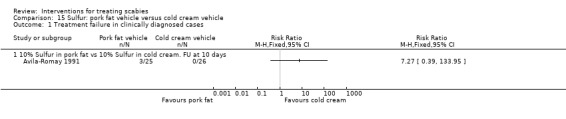

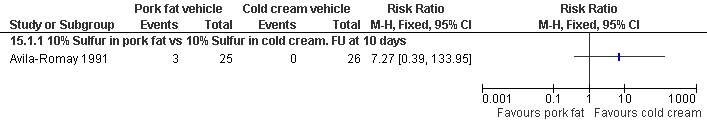

5.1. Sulfur: pork fat vehicle versus cold cream vehicle (51 participants, 1 trial)

Treatment failure in clinically diagnosed cases

See Analysis 15.1. There was no significant difference in the number of treatment failures between the two groups after 10 days in Avila‐Romay 1991 (51 participants). Figure 24.

15.1. Analysis.

Comparison 15 Sulfur: pork fat vehicle versus cold cream vehicle, Outcome 1 Treatment failure in clinically diagnosed cases.

24.

Forest plot of comparison: 15 Sulfur: pork fat vehicle versus cold cream vehicle, outcome: 15.1 Treatment failure in clinically diagnosed cases.

Adverse events

See Table 17. Pruritus, xerosis, burning sensation, and erythema were reported for cases and contacts in both groups. There were adverse events in 68/53 participants in the pork fat vehicle group, including keratosis pilaris. There were adverse events in 45/58 participants in the cold cream vehicle group, including keratosis follicularis.

Discussion

The review's objective was to evaluate the effectiveness of current treatments for scabies in order to inform practice and guide future research. The previous version of this review noted that clinicians faced considerable uncertainty when choosing the best treatment for scabies (Walker 2000). Ten years later the picture is a little clearer, but there are still considerable gaps in our knowledge.

Trial quality

All 22 included trials were designed to test the effectiveness of one or more treatments for scabies. Methodological quality varied between trials. Only two trials described both adequate randomization sequence generation and adequate allocation concealment, and the majority of the reports described neither adequately. The blinding was absent, or the degree of blinding was unclear in ten of the 22 identified trials, and losses to follow up were greater than 20% of the enrolled participants in four of the trials.

Effectiveness

The results of this review suggest that, of the topical treatments for scabies, permethrin is most effective. Permethrin has been tested against topical crotamiton, topical lindane, and oral ivermectin in randomized controlled trials, and it appears to be superior to all three in terms of minimizing treatment failure in participants with a clinical diagnosis of scabies. In the one trial that tested permethrin against topical benzyl benzoate no difference in cure rate was detected, however this trial was small (53 participants) and the data used in the review related only to one week follow up.

In the subgroup of participants with microscopically confirmed scabies, permethrin was again superior to crotamiton, but there is uncertainty as to whether permethrin is superior to lindane. Permethrin also appears to be better at relieving itch than either crotamiton or lindane (itch was not reported as a separate outcome in the ivermectin versus permethrin trial). Unfortunately no trials comparing permethrin with either topical sulfur or topical malathion were identified; permethrin's relative effectiveness against these treatments therefore remains unknown.

In some countries natural pyrethrin‐based topical treatments are available as an alternative to permethrin cream (Biele 2006). Pyrethrins are naturally occurring insecticidal compounds found in the Compositae family of plants (Wagner 2000), whereas permethrin is a synthetic pyrethroid analogue. Results from the two Italian trials included in this review suggest that pyrethrin is equivalent in effectiveness to both permethrin and benzyl benzoate.

Trials comparing crotamiton with lindane, lindane with sulfur, and sulfur with benzyl benzoate have all produced equivocal results, suggesting that there is no single most effective treatment out of these four topical options. In most countries the choice is in any case restricted, either due to lack of availability, or the lack of a licence for scabies.

Ivermectin is currently the only oral treatment for scabies that is in routine use. It appears to be more effective than both placebo and lindane, but less effective than permethrin. There was significant heterogeneity in the results of the five trials that compared ivermectin and benzyl benzoate, which may be explained by differences in drug regimen and length of follow up between the trials. After stratifying by drug regimen and length of follow up the relative effectiveness of ivermectin appeared to increase with increasing length of follow up. This may mean that ivermectin is slower in achieving cure than topical benzyl benzoate, however, this conclusion is rather speculative given these data.

An advantage of an oral antiscabietic treatment over a topical one is ease of use, particularly in hot humid climates, when engaging in mass treatment, or when treating children. However, ivermectin is not presently licensed for the treatment of scabies in most countries. Ivermectin's effectiveness, cost effectiveness, and safety in mass treatment in areas of high endemicity (preferably as a sustainable public health intervention) need to be further evaluated in larger trials of sufficient power.

Topical ivermectin has also been suggested to be effective after success in uncontrolled studies (Yeruham 1998; Victoria 2001). At present there is no commercially available topical ivermectin preparation available for the treatment of scabies, and randomized controlled trials are needed to evaluate this potential new treatment option.

There are still no published reports of randomized controlled trials that test the effectiveness of malathion against either placebo or another drug, despite over 30 years passing by since a non‐controlled study first suggested that the drug was effective (Hanna 1978). The 2010 British National Formulary recommends malathion as the treatment of choice if permethrin is inappropriate (BNF 2010), despite the lack of evidence from randomized controlled trials. Such a trial comparing malathion with permethrin is needed to test their relative effectiveness.

We found trials of the herbal remedies toto soap (Alebiosu 2003) and lippia oil (Oladimeji 2000; Oladimeji 2005), but these trials did not meet the review's inclusion criteria. Both treatments look promising, but randomized controlled trials making direct comparisons with the existing best treatments are needed to assess their true relative effectiveness.

Treatment regimen was assessed in two trials. Maggi 1986 found that a one‐hour application of lindane reduced itch compared with a much longer four‐day application; the authors suggested that the itch may, at least in part, have been due to a dermatitis caused by the lindane treatment itself. Schenone 1986 compared two different regimens using decamethrin, a pyrethroid insecticide in the same class as permethrin. All participants were cured in both groups. Decamethrin is not commercially available for the treatment of scabies and we found no trials that tested its effectiveness against other treatments. Decamethrin (as deltamethrin) is usually used as an agricultural insecticide and its safety as an antiscabietic medication has not been established (WHO 1990).

The formulation of a topically applied product may influence its efficacy. For example, a 1% permethrin formulation marketed for the treatment of head lice appears to be less effective than the conventional antiscabietic 5% preparation, according to case reports (Cox 2000). None of the trials included in this review directly compared different strength formulations of the same treatment.

One trial compared different vehicles for the same drug (Avila‐Romay 1991). Cold cream as a treatment vehicle for sulfur may be more effective than pork fat, with fewer adverse events. For resource‐poor countries this could be a cheap and safe option, which in some circumstances might also be more culturally acceptable.

This review did not seek to assess the relative cost effectiveness of the various treatments for scabies; however, large cost differences are apparent. In the UK, costs are: permethrin £5.51 per 30 g of cream, benzyl benzoate £0.50 per 100 mL, crotamiton £2.99 per 100 mL, and malathion £2.96 per 100 mL (BNF 2010). When lindane was marketed in the UK it was a fifth the cost of permethrin per treatment (BNF 1997).

We did not specifically attempt to assess the effectiveness of treatments for crusted scabies, and none of the included trials selected participants with this diagnosis. Caution should therefore be exercised in generalizing the results of this review to the treatment of patients with atypical severe scabies infection. This is an important area where more research is needed.

Caution should also be exercised in generalizing these results, which were obtained from trials that recruited individual participants (mostly in the outpatient setting), to the management of outbreaks in institutions. Given the burden of disease caused by scabies within institutions, such as long‐term healthcare facilities, the inclusion of such patients in randomized controlled trials of effectiveness would be beneficial.

Mass treatment of a community in order to eradicate scabies has been tested in two studies (Dunne 1991; Bockarie 2000), both of which used oral ivermectin. Unfortunately neither of these studies met the review's inclusion criteria (Bockarie 2000 was an uncontrolled trial, and Dunne 1991 recruited participants on the basis of a diagnosis of onchocerciasis). Further research is needed to test the effectiveness, safety, and practicality of this approach to the management of scabies, particularly in areas of high prevalence.

Safety

Serious adverse events leading to death or permanent disability were not reported in any of the included or excluded trials. This review did not seek to systematically review the literature on the safety of antiscabietic treatments, but a number of notable reports of serious adverse events that have been published elsewhere are discussed below.

Convulsions and aplastic anaemia have both been reported with the use of lindane (Rauch 1990; Elgart 1996); in some cases this being thought to be due to the application of the drug to non‐intact skin. Lindane was withdrawn by the manufacturer from the UK market in 1996, but this was for commercial and not toxicological reasons. In 1995, the US Food and Drug Administration designated lindane as a second‐line treatment due to its potential toxicity; only to be used in those who have failed to respond to, or who are intolerant of, other antiscabietic treatments (WHO 2003).

Ivermectin has been very widely used in the treatment of onchocerciasis (predominantly in adults) and even with repeated doses serious adverse effects have been rare (DeSole 1989; Pacque 1990). However, an increased risk of death among a group of elderly patients with scabies in a long‐term care facility has been reported (Barkwell 1997). Whether this was due to ivermectin or to interactions with other scabicides, including lindane and permethrin, or other treatments such as psychoactive drugs was not clear and there was considerable discussion of the validity of this report (Bredal 1997; Coyne 1997; Diazgranados 1997; Reintjes 1997).

Rare adverse reactions have been reported with the use of both permethrin (dystonia, Coleman 2005) and natural pyrethrin (fatal asthma, Wagner 2000).

The relative purity of the active ingredients of certain topical treatments and their isomeric ratios may also affect drug toxicity. In particular, very little is known about the effects of exposure to different isomeric grades of permethrin. Clinical grade material is 25:75 cis isomer:trans isomer and agricultural grade is 40:60. The cis isomer has 10 times the acute toxicity and there could be dangers in people in resource‐poor countries using agricultural‐grade permethrin for treating human infestations (personal communication from Ian Burgess, Medical Entomology Centre, Cambridge). Similar problems have been reported with the inappropriate use of agricultural grade malathion for treating human infestations (Petros 1990).

A search of the WHO Adverse Drug Reaction Database in 1998 for a previous version of this review found reports of serious adverse drug reactions for convulsions (benzyl benzoate 4, crotamiton 1, lindane 38, malathion 2, permethrin 6) and death (benzyl benzoate 0, crotamiton 1, lindane 1, malathion 0, permethrin 5) (Walker 2000). A search for this update of the review of the UK Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency database of suspected drug reactions found reports for convulsions (benzyl benzoate 1, crotamiton 0, lindane 3, malathion 0, permethrin 0, sulfur 0, ivermectin 1) and death (benzyl benzoate 0, crotamiton 0, lindane 1, malathion 0, permethrin 1 (intra uterine death), sulfur 0, ivermectin 3) (MHRA 2006). Extreme caution must be shown in interpreting these reports, as they are clearly influenced by the extent to which the products are used and by the quality of the reporting. Neither can a causal link be assumed for any of the reported events.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

On the basis of the available evidence from randomized controlled trials, topical permethrin appears to be the most effective treatment for scabies. Ivermectin appears to be an effective oral treatment, but in many countries it is not licensed for this indication.

Implications for research.

Trials are needed to evaluate the relative effectiveness of malathion against permethrin, and the relative effectiveness of herbal treatments against existing treatments. The effectiveness of topical ivermectin also needs to be explored. The most appropriate treatment for the severe crusted form of scabies has not yet been established in randomized controlled trials.

Researchers should ensure that toxicity and safety outcomes are systematically collected in future trials as well as being notified through routine monitoring of adverse events in clinical practice.

Approaches to the control of outbreaks in institutions and public health programmes to control scabies in populations with high prevalence require evaluation.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 11 August 2010 | New search has been performed | Two new trials Bachewar 2009 and Ly 2009 added. Trials now stratified according to drug regimen and length of follow up if heterogeneity detected. Removal of meta‐analyses where heterogeneity detected. Minor changes to conclusion regarding effectiveness of ivermectin compared with benzyl benzoate. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 1996 Review first published: Issue 4, 1997

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 18 August 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format with minor editing. |

| 30 April 2007 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | 2007, Issue 3: A substantive update with new authors. We included nine new trials and excluded two studies (Dunne 1991 and Macotela‐Ruiz 1996) included in Walker 2000 after re‐evaluation, as noted in the 'Characteristics of excluded studies'. The review has been rewritten and reformatted throughout, and the conclusions of the review have been updated to reflect the new trial evidence. We used more precise definitions in the 'Types of interventions' and separated the 'Types of outcome measures' into primary, secondary, and adverse events. Treatment failure in those clinically diagnosed and treatment failure in those microscopically confirmed are considered as separate outcome measures, while parasitological cure is no longer an outcome measure. We reformatted the search strategy section, but did not attempt to systematically search literature for adverse events. For data analysis, we used relative risks rather than odds ratios, and used a random‐effects model for meta‐analysis if significant heterogeneity was present. We used available‐case analyses rather than intention‐to‐treat analyses using imputed data. |

| 1 February 2006 | New search has been performed | New studies found and included or excluded. |

| 1 January 2000 | New search has been performed | 2000, Issue 3: Revised, synopsis added, and updated with new studies (Walker 2000). |

| 1 January 1999 | New search has been performed | 1999, Issue 3: Revised and updated with new studies (Walker 1999b). |

| 1 January 1999 | New search has been performed | Revised with new title 'Interventions for treating scabies' (Walker 1999a). |

Acknowledgements

We are heavily indebted to Dr Godfrey Walker who, with Paul Johnstone, co‐authored the previous version (Walker 2000). The editorial base for the Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group is funded by the UK Department for International Development (DFID) for the benefit of low‐ and middle‐income countries.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search methods: detailed search strategies

| Search set | CIDG SRa | CENTRAL | MEDLINE/EMBASEb | LILACSb | INDMED |

| 1 | scabies | scabies | scabies | scabies | scabies |

| 2 | — | Sarcoptes scabiei | SCABIES | treatment | Sarcoptes scabiei |

| 3 | — | 1 or 2 | 1 or 2 | 1 and 2 | 1 or 2 |

| 4 | — | — | treatment | — | — |

| 5 | — | — | benzyl benzoate | — | — |

| 6 | — | — | crotamiton | — | — |

| 7 | — | — | lindane | — | — |

| 8 | — | — | malathion | — | — |

| 9 | — | — | permethrin | — | — |

| 10 | — | — | ivermectin | — | — |

| 11 | — | — | sulphur | — | — |

| 12 | — | — | hexachlorocyclohexane | — | — |

| 13 | — | — | gamma benzene hexachloride | — | — |

| 14 | — | — | 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 | — | — |

| 15 | — | — | 3 and 14 | — | — |

| 16 | — | — | Limit 15 to human | — | — |

aCochrane Infectious Diseases Group Specialized Register. bSearch terms used in combination with the search strategy for retrieving trials developed by The Cochrane Collaboration (Higgins 2006); upper case: MeSH or EMTREE heading; lower case: free text term.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Ivermectin versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Treatment failure in clinically diagnosed cases | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.1 200μg/kg Ivermectin vs placebo. Follow up at 7 days | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

Comparison 2. Ivermectin versus permethrin.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Treatment failure in clinically diagnosed cases | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 200μg/kg Ivermectin vs 5% Permethrin overnight. | 2 | 140 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.61 [2.07, 10.26] |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Ivermectin versus permethrin, Outcome 1 Treatment failure in clinically diagnosed cases.

Comparison 3. Ivermectin versus lindane.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Treatment failure in clinically diagnosed cases | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 150‐200μg/kg Ivermectin vs 1% Lindane. | 2 | 193 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.36 [0.23, 0.58] |

Comparison 4. Ivermectin versus benzyl benzoate.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Treatment failure in clinically diagnosed cases | 5 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.1 200μg/kg Ivermectin vs 25% BB overnight x2. FU at 1 week | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.2 150‐200μg/kg Ivermectin vs 12.5% BB 1 or 2 overnights. FU at 14 days | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.3 200μg/kg Ivermectin vs 10% BB overnight. FU at 3 weeks | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.4 100μg/kg Ivermectin vs 10% BB 3 x 12 hrs. FU at 30 days | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.5 200μg/kg Ivermectin vs 25% BB 72 hrs. FU at 30 days | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2 Itch persistence | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2.1 200μg/kg Ivermectin vs 10% BB overnight. FU at 3 weeks | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

Comparison 5. Permethrin versus crotamiton.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Treatment failure in clinically diagnosed cases | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 5% Permethrin vs 10% Crotamiton. FU at 28 days | 2 | 194 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.24 [0.10, 0.55] |

| 2 Treatment failure in microscopically diagnosed cases | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 5% Permethrin vs 10% Crotamiton. FU at 28 days | 2 | 194 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.24 [0.10, 0.55] |

| 3 Itch persistence | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3.1 5% Permethrin vs 10% Crotamiton. FU at 28 days | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

Comparison 6. Permethrin versus lindane.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Treatment failure in clinically diagnosed cases | 5 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 5% Permethrin vs 1% Lindane single application repeated at 1 week. FU at 14 days | 1 | 99 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.15 [0.06, 0.40] |

| 1.2 5% Permethrin vs 1% Lindane overnight x2. FU at 28 days | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.08 [0.01, 0.57] |

| 1.3 5% Permethrin vs 1% Lindane single application. FU at 28 days | 3 | 554 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.59 [0.37, 0.95] |

| 2 Treatment failure in microscopically diagnosed cases | 3 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 5% Permethrin vs 1% Lindane single application. FU at 28 days | 2 | 384 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.57 [0.32, 1.02] |

| 2.2 5% Permethrin vs 1% Lindane overnight x2. FU at 28 days | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.08 [0.01, 0.57] |

| 3 Itch persistence | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 5% Permethrin vs 1% Lindane single application. FU at 28 days | 2 | 490 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.61 [0.44, 0.86] |