To the Editor:

Atopic dermatitis ([AD], synonymous with eczema or atopic eczema) is a common and burdensome condition occurring in patients of all ages. Most research has focused on pediatric disease because symptoms often present early in life, and little is known about disease course past childhood.1 We report on the results of a longitudinal cohort study using the Pediatric Eczema Elective Registry (PEER), which follows individuals for up to 10 years during the transition to early adulthood. Our objectives were to define patterns of AD disease control by age and to examine whether patient characteristics are predictive of these patterns.

We studied 6720 patients with mild-to-moderate AD who had used pimecrolimus for >6 weeks. They were enrolled by physicians from across the United States and subsequently followed via biannual mail surveys. The primary outcome used to define patterns of disease control was complete control without treatment (yes/no) for each 6-month period. This was derived from 2 repeating questions about disease control and treatment use.

Latent class analysis was used to identify patterns of disease control. We included age at survey as a predictor of the outcome, and we controlled for age at cohort enrollment. As predictors of the latent class, we included all the covariates available at baseline hypothesized a priori to explain variation in persistence: sex, race, baseline family income, history of atopy, and age at disease onset.

After performing the latent class analysis, we compared the proportion of individuals in each subgroup with filaggrin and filaggrin-2 null mutations. These were not used as predictors in the model because they were only available for a subset of the population who sent biosamples. In addition, we compared history of treatment use, history of allergies, and history of smoke exposure at baseline between the subgroups from the model. Additional details regarding the methods are available in this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org.

A total of 65,237 surveys (mean, 10.4) were returned by 6,270 racially diverse participants ages 2 to 26 years, comprising 33,074 person-years of follow-up (Table I). The primary outcome, complete control without treatment, was reported on 9% of all surveys.

TABLE I.

Demographic characteristics of cohort and results of latent class analysis

| Class 1 |

Class 2 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| overall |

Resolving |

Persistently active |

||

| N=6270 |

n=702 |

n=3905 |

||

| Patient characteristics included in the model | n(%) | % | % | OR (95% CI)* |

| Female sex | 6270 (53) | 43 | 55 | 1.63 (1.35–1.95) |

| Income <$50,000/y | 4639 (75) | 57 | 78 | 1.69 (1.37–2.08) |

| Non white race | 6269 (65) | 47 | 73 | 2.38 (1.94–2.91) |

| History of atopy | 4682 (75) | 72 | 75 | 1.36 (1.10–1.67) |

| Age at eczema onset (y), mean ± SD | n = 6239, 2.3 ± 3.0 | 2.9 ± 2.5 | 2.0 ± 2.9 | 0.91 (0.88–0.93) |

|

Additional patient characteristics compared by model classification |

P value † | |||

| Genetics | ||||

| Any filaggrin null mutation | 829 (17) | 18 | 16 | .596 |

| Any filaggrin-2 null mutation | 337 (45) | 36 | 46 | .294 |

| Mean proportion of visits with frequent treatment use before age 8 | ||||

| Topical calcineurin inhibitor | 4010 (80) | 57 | 85 | .000 |

| Topical steroids | 4000 (54) | 37 | 56 | .000 |

| Any prescription med for eczema | 4010 (91) | 69 | 96 | .000 |

| History of allergies at enrollment | ||||

| Animals | 6262 (22) | 18 | 23 | .003 |

| Foods | 6265 (24) | 18 | 25 | .000 |

| Meds | 6264 (12) | 13 | 11 | .135 |

| Smoker in the home at enrollment | ||||

| Yes | 6213 (16) | 11 | 15 | .001 |

OR, Odds ratio.

Odds of membership in the “persistently active” class from the 2-class model that included age at survey and age at enrollment as predictors of outcome and all of the listed patient characteristics as predictors of class.

Pearson chi-square or t-test.

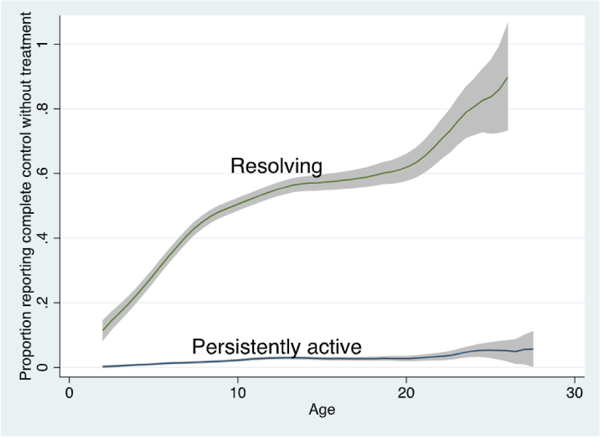

Latent class analysis suggested there were 2 subgroups with clinically distinct patterns of disease control: a group more likely to report periods of complete control without treatment as they aged (termed “resolving”) and a group more likely to report “persistently active” disease past childhood (Fig 1).

FIG 1.

Proportion of cohort reporting complete control without treatment by age and disease class. We plotted the proportion of individuals reporting complete control without treatment at each age for each of the 2 subgroups resulting from the latent class model using Epanechnikov kernel-weighted local polynomial smoothed plots with 95% CIs in gray. Note this graph represents actual data and not predicted probabilities from the models.

History of atopy, female sex, family income under $50,000/ year at enrollment, nonwhite race, and younger age at eczema onset were significant predictors of membership in the “persistently active” subgroup (Table I). Blacks made up nearly half of the cohort, and the results of sensitivity analyses using alternate categorizations of race (eg, black vs white) resulted in even higher odds of membership in the “persistently active” subgroup (odd ratio, 3.23, 95% Cl, 2.54–4.10) (see Table E2 in this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org). Income data was limited to self-reported family income at enrollment and was not adjusted for family size. To address this potential source of measurement error, we conducted a sensitivity analysis without income and found similar results (Table E2).

When comparing the classes produced by the model, we found no significant differences in the proportion of patients with filaggrin or filaggrin-2 null mutations. Patients classified into the “persistently active” class were significantly more likely to have reported frequent use of eczema medications at younger ages. Results are presented for treatment before age 8 years; additional comparisons varying the age cut point and found similar results (data not shown). Finally, we found that those in the “persistently active” group were significantly more likely to report a history of animal allergies, food allergies, or presence of a smoker in the home.

Using a latent class analysis, which is well suited to identify trajectories of heterogeneous patterns of discrete outcomes, we demonstrate the existence of subgroups of patients with clinically distinct disease courses and found that standard patient characteristics are highly predictive of persistently active disease. These are helpful for clinicians to consider when counseling patients and identifying who may benefit from more intensive follow-up and intervention. This article builds on a prior publication that found similar factors are associated with symptom-free periods at any age, but that publication did not address disease course or answer the crucial and more clinically relevant question of which children are most likely to have persistent disease.2

Our findings that female sex and history of allergies are associated with more persistent disease corroborate those from other studies with limited follow-up. 3–5 We also report a number of novel findings. Notably, we found that income and race were strongly associated with AD persistence. In multivariate models, the magnitude of association with income <$50,000/year and black race was larger than the association with history of atopy, previously thought to be among the strongest predictors of AD persistence.6 Our results differ from many studies that have found that higher income is associated with higher AD incidence or prevalence.7 We hypothesize that drivers of disease onset may be different from drivers of disease persistence; additional research is needed to test this hypothesis and to examine how changes in income or socioeconomic status over time relate to eczema disease control.

The strengths of our study include a large and diverse cohort with repeated measures of disease control and treatment use. The primary limitation relates to the generalizability of the findings. Because patients were required to use pimecrolimus for ≥6 weeks prior to enrollment, the PEER cohort is likely biased toward more persistent disease (because those who had early clearance would be less likely to have required pimecrolimus at later ages). Therefore the proportion of individuals in each disease class may not be representative of the general AD population. The goal of our study was not to describe how many individuals are likely to have each disease control pattern. Rather, our focus was to identify predictors of each subgroup, which are more likely to be generalizable to AD population seeking treatment. It is also possible that use of pimecrolimus, corticosteroids, or other topical treatments could alter the skin barrier and predispose to more persistent disease, but sensitivity analyses stratifying by history of treatment use during follow-up did not reveal any differences in our results.

An additional limitation, common to nearly all large longitudinal studies, is attrition; 35% of individuals were lost to follow-up. There was only a median of 0 missing surveys in sequence (interquartile range, 0–1), and although sensitivity analyses do not exclude the possibility of bias, they did not reveal any difference in the results when we included only individuals with longer-term or full follow-up (Table E2).

Our results highlight the importance of characterizing AD as a chronic condition and the necessity of longitudinal studies that permit the analysis of disease control over time. Future research should examine mechanisms for these differences.

Extended Data

TABLE E1.

Results of 2 to 5 class models from latent class analysis

| 2-Class model | 3-Class model | 4-Class model | 5-Class model | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model fit statistics | ||||

| Log likelihood | –10,875 | –10,279 | –10,148 | –10,108 |

| Degrees of freedom | 11 | 19 | 27 | 35 |

| BIC | 21,869 | 20,764 | 20,589 | 20,595 |

| Distribution of individuals among subgroups | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) |

| Persistently active class | 3,905 (85) | 3,622 (79) | 3,344 (73) | 3,343 (73) |

| Intermediate class A | N/A | 592 (13) | 615 (13) | 629 (14) |

| Intermediate class B | N/A | N/A | 377 (8) | 276 (6) |

| Intermediate class C | N/A | N/A | N/A | 151 (3) |

| Resolving class | 702 (15) | 393 (9) | 271 (6) | 208 (5) |

| Odds of subgroup membership by patient factor | OR (95% Cl) | OR (95% Cl) | OR (95% Cl) | OR (95% Cl) |

| “Persistently active” vs “Resolving” class | ||||

| Female | 1.63 (1.35–1.95) | 1.73 (1.36 2.19) | 1.68 (1.24–2.27) | 1.91 (1.30 2.79) |

| Income <$50,000/y | 1.69 (1.37–2.08) | 1.68 (1.28 2.21) | 1.74 (1.23–2.45) | 1.55 (1.03–2.34) |

| History of atopy | 1.36 (1.10–1.67) | 1.55 (1.19 2.02) | 1.76 (1.27–2.46) | 2.07 ( 1.40–3.07) |

| Nonwhite race | 2.38 (1.94–2.91) | 2.94 (2.25 3.84) | 3.57 (2.54–5.01) | 4.24 (2.80–6.42) |

| Age of onset (y) | 0.91 (0.88 0.93) | 0.88 (0.85 0.91) | 0.79 (0.75–0.85) | 0.81 (0.75–0.88) |

| “Intermediate class A” vs “Resolving” class | ||||

| Female | 1.19 (0.88 1.62) | 1.47 (1.04–2.07) | 1.63 (1.08 2.46) | |

| Income <$50,000/y | 0.78 (0.55 1.10) | 0.97 (0.66–1.42) | 0.90 (0.57 1.43) | |

| History of atopy | 1.19 (0.85–1.66) | 1.28 (0.88–1.85) | 1.45 (0.93 2.24) | |

| Nonwhite race | 1.62 (1.14–2.28) | 1.67 (1.14–2.45) | 1.99 (1.26 3.14) | |

| Age of onset (y) | 0.97 (0.93 1.01) | 0.96 (0.91 1.01) | 0.98 (0.92 1.04) | |

| “Intermediate class B” vs “Resolving” class | ||||

| Female | 0.92 (0.61–1.39) | 1.24 (0.70–2.20) | ||

| Income <$50,000/y | 0.77 (0.48–1.22) | 0.84 (0.45 1.55) | ||

| History of atopy | 1.20 (0.77–1.89) | 1.21 (0.68 2.15) | ||

| Nonwhite race | 1.71 (1.08–2.71) | 2.18 (1.18–4.04) | ||

| Age of onset (y) | 0.97 (0.92–1.03) | 1.04 (0.97–1.11) | ||

| “Intermediate class C” vs “Resolving” class | ||||

| Female | 1.03 (0.57 1.85) | |||

| Income <$50,000/y | 0.45 (0.23–0.89) | |||

| History of atopy | 2.42 (1.18–4.98) | |||

| Nonwhite race | 1.73 (0.87 3.44) | |||

| Age of onset (y) | 1.00 (0.92–1.09) | |||

BIC, Bayesian information criterion; N/A, not applicable.

TABLE E2.

Results of sensitivity analyses for 2-class latent class analysis

| Sensitivity analyses exploring race categorization |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Class 1 “resolving”‘ | Class 2 “persistently active” | OR {95% Cl)* | |

| Race modeled as any black vs any white (including Hispanic and mixed) |

|||

| No. in each subgroup | n=629 | n=3628 | |

| Female sex | 45 | 55 | 1.51 (1.25–1.84) |

| Income <$50,000/y | 58 | 78 | 1.52 (1.22–1.89) |

| History of atopy | 74 | 75 | 1.19 (0.95–1.48) |

| Any black | 35 | 65 | 2.83 (2.27–3.53) |

| Age at eczema onset (y), mean | 2.9 | 2.0 | 0.90 (0.87–0.92) |

| Race modeled as black only vs white only | |||

| No. in each subgroup | n = 573 | n = 3268 | |

| Female sex | 44 | 55 | 1.53 (1.25–1.88) |

| Income <$50,000/y | 56 | 78 | 1.44 (1.14–1.83) |

| History of atopy | 76 | 76 | 1.11 (0.88–1.41) |

| Black only | 34 | 67 | 3.23 (2.54–4.10) |

| Age at eczema onset (y), mean | 2.9 | 2.0 | 0.90 (0.87–0.93) |

| Sensitivity analyses exploring missing and limited variables | |||

| Modeled without income variable (because only available at enrollment, not adjusted for family size, and 26% had preferred not to answer) | |||

| No. in each subgroup | n = 1015 | n = 5215 | |

| Female sex | 45 | 55 | 1.47 (1.25–1.71) |

| History of atopy | 40 | 70 | 1.26 (1.05–1.51) |

| Nonwhite race | 74 | 75 | 3.50 (2.99–4.09) |

| Age at eczema onset (y), mean | 3.1 | 2.1 | 0.90 (0.88–0.92) |

| Including only those not lost to follow-up (ie, survey within the last 18 mo) |

|||

| No. in each subgroup | n = 562 | n = 2413 | |

| Female sex | 44 | 55 | 1.55 (1.26–1.90) |

| Income <$50,000/y | 55 | 76 | 1.75 (1.39–2.21) |

| History of atopy | 45 | 71 | 1.31 (1.04–1.65) |

| Nonwhite race | 72 | 76 | 2.27 (1.8 2.85) |

| Age at eczema onset (y), mean | 2.8 | 2.0 | 0.90 (0.87–0.93) |

| Including only those with follow-up over 5 y | |||

| No. in each subgroup | n = 522 | n = 2130 | |

| Female sex | 43 | 55 | 1.62 (1.32–2.01) |

| Income <$50,000/y | 49 | 70 | 1.79 (1.42–2.26) |

| History of atopy | 41 | 67 | 1.41 (1.12–1.78) |

| Nonwhite race | 71 | 76 | 2.29 (1.82–2.89) |

| Age at eczema onset (y), mean | 2.7 | 1.9 | 0.91 (0.88–0.94) |

Values are percentages unless otherwise indicated.

Odds of membership in the “persistently active” class from a 2-class model that included age at survey and age at enrollment as predictors of outcome and all of the listed patient characteristics as predictors of class.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Luke Keele (PhD, Associate Professor, Georgetown University) for his uncompensated input regarding the statistical analysis.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UCSF-CTSI Grant Number KL2 TROOQ143) and by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (ROl AR056755 and K24 AR064310). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. The PEER study was funded by Valeant Pharmaceuticals International through a grant to the Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania and D.J.M. Valeant had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Disclosure of potential conflict of interest: J. Gelfand has received grants from Regeneron and Sanofi and personal fees from Sanofi; also has consulted or received grants from a variety of companies that conduct work in psoriasis (he does not think it is relevant to this work so they are not listed). K. Abuabara and C. McCulloch have received a grant from the National Institutes of Health for this work.

The rest of the authors declare that they have no relevant conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Weidinger S, Novak N. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet 2016;387:1109–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Margolis JS, Abuabara K, Bilker W, Hoffstad O, Margolis DJ. Persistence of mild to moderate atopic dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol 2014;150:593–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ballardini N, Kull I, Soderhall C, Lilja G, Wickman M, Wahlgren CF. Eczema severity in preadolescent children and its relation to sex, filaggrin mutations, asthma, rhinitis, aggravating factors and topical treatment: a report from the BAMSE birth cohort. Br J Dermatol 2013;168:588–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garmhausen D, Hagemann T, Bieber T, Dimitriou I, Fimmers R, Diepgen T, et al. Characterization of different courses of atopic dermatitis in adolescent and adult patients. Allergy 2013;68:498–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Illi S, von Mutius E, Lau S, Nickel R, Gruber C, Niggemann B, et al. , for the Multicenter Allergy Study Group. The natural course of atopic dermatitis from birth to age 7 years and the association with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2004; 113:925–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Apfelbacher CJ, Diepgen TL, Schmitt J. Determinants of eczema: population-based cross-sectional study in Germany. Allergy 2011;66:206–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Uphoff E, Cabieses B, Pinart M, Valdes M, Anto JM, Wright J. A systematic review of socioeconomic position in relation to asthma and allergic diseases. Eur Respir J 2015;46:364–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]