Abstract

This study examined the short-term efficacy of Media Aware, a classroom based media literacy education (MLE) program for improving adolescents’ sexual health outcomes. In a randomized control trial, schools were randomly assigned to the intervention (N=5 schools) or health promotion control (N=4 schools) group. Students completed questionnaires at pretest (N=880 students) and immediate posttest (N=926 students). The Media Aware program had a significant favorable impact on adolescent outcomes related to sexual health, including increased self-efficacy and intentions to use contraception, if they were to engage in sexual activity; enhanced positive attitudes, self-efficacy, and intentions to communicate about sexual health; decreased acceptance of dating violence and strict gender roles; and increased sexual health knowledge. Program effects were also found for media-related outcomes, including enhanced media deconstruction skills and increased media skepticism. Media deconstruction skills mediated the program’s impact on students’ intentions to communicate with a medical professional about sexual health issues. This study provides support for the use of MLE with adolescents to promote sexual health.

Keywords: adolescents, media literacy education, sexual health, dating violence, health communication

Introduction

During adolescence many young people begin to explore romantic and sexual relationships. Twenty percent of ninth grade students report having had sex, and this number increases to almost sixty percent (57%) at twelfth grade (Kann et al., 2018). Many teens engage in behaviors that put them at risk for negative outcomes, including unintended pregnancies and sexually transmitted infections (STIs). For example, nearly half (46%) of sexually active high school students reported that they or their partner did not use a condom at last intercourse and 14% reported using no form of contraception (Kann et al., 2018). These behaviors are concerning considering the fact that half of the 20 million new STI cases each year are among people between the ages of 15 and 24 (Satterwhite et al., 2013), and the U.S. has one of the highest teen birth rates among comparable countries (United Nations Department of Economic & Social Affairs, 2014).

Adolescent Sexual Health Promotion

Most school districts in the U.S, have policies stating that sexual health be taught in middle and high school (CDC SHPPS, 2016), and research has demonstrated that comprehensive sexual health education can be effective in reducing adolescent sexual risk behaviors (Goesling, Colman, Trenholm, Terzian, & Moore, 2014).The Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980) and the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) (Ajzen, 1991) have been used as theoretical frameworks for the development of programs that promote adolescent sexual health (Kirby, Laris, & Rolleri, 2007). TRA and TPB are similar in that they posit that personal attitudes, normative beliefs, and behavioral control regarding a particular behavior predict intentions to engage in that behavior and subsequent behaviors. These constructs have been found to predict sexual health behaviors including abstinence (for review see Buhi & Goodson, 2007) and condom use (Albarracin et al, 2001). Evidence-based sexual health education programs can positively impact adolescent sexual health (Kirby et al., 2007); however, few of these interventions address an important influence on adolescent sexual health, namely, media.

Media Exposure and Adolescent Sexual Health

Teens spend about nine hours per day using entertainment media (Rideout, 2015), and adolescents cite media as sources for sexual information (Bleakley, Hennessy, Fishbein, & Jordan, 2009). Media messages containing sexual content are pervasive, and often contain inaccurate, incomplete, and unhealthy information about sex and relationships (Pardun, L’Engle, & Brown, 2005). For example, TV programs frequently depict sexual situations but rarely mention any of the responsibilities or risks that accompany having sex (Eyal, Kunkel, Biely, & Finnerty, 2007). In addition, popular music lyrics with sexual themes are frequently degrading (Primack, Gold, Schwarz, & Dalton, 2008), and representations of females in media messages are often stereotypical or sexualized (Collins, 2011).

Previous research has found associations between adolescents’ media consumption and beliefs about sex, including permissive attitudes about uncommitted sexual activity, expectations about sex, and perceived peer sexual behavior (see Ward, Reed, Trinh, & Foust, 2014). Furthermore, there is evidence that adolescents’ exposure to sexual media predicts sexual behavior (Brown et al., 2006; R. L. Collins et al., 2004; Martino et al., 2006) and teen pregnancy, even after accounting for the influence of several covariates (Chandra et al., 2008). Studies have also reported that media exposure plays a role in adolescent’s reinforcement of strict gender-role stereotypes (Ward, 2002), and exposure to media content that combines sex and violence is related to the acceptance of dating violence (i.e., date rape) among middle school-aged males (Kaestle, Halpern, & Brown, 2007).

Media Literacy Education as a Protective Factor

Media literacy has been defined as the ability to access, analyze, evaluate, and produce media in a variety of forms (Aufderheide, 1993). Media literacy education (MLE) enhances critical thinking about media messages in an attempt to disrupt the influence that inaccurate messages may have on youth. There is substantial evidence that MLE can be an effective intervention for changing outcomes related to youth risk behaviors (see Jeong, Cho, & Hwang, 2012), and recent research has explored the effectiveness of MLE as an avenue for teaching sexual health with promising results (Scull, Kupersmidt, Malik, & Keefe (2018); Scull, Malik, & Kupersmidt (2014); Pinkleton, Austin, Chen, & Cohen, 2012). A preliminary feasibility study of a teacher-led comprehensive sexual health MLE program for middle school students, (Media Aware), used a pre-post (no control group) design and found that the program resulted in decreased perceived realism and increased skepticism of media messages, as well as increased media deconstruction skills (Scull, Malik, & Kupersmidt (2014)). After the program, students were more likely to intend to use condoms and talk to their partners, parents, or medical professionals prior to sex.

The Media Interpretation Processing Model

Several MLE programs have used the Message Interpretation Processing Model (MIP: Austin & Johnson, 1997b) as a theoretical framework for understanding the processing of media messages and their effects on health behaviors. The MIP model proposes that logical (i.e., perceived realism of and perceived similarity to media messages) and affective (i.e., perceived desirability of media messages) constructs directly influence the degree of identification with a media message, which, in turn, influences the valence of expectancies regarding the behavior portrayed in the message, and, ultimately, behavioral choices. The model suggests that decreased perceived media realism, similarity, and desirability can act as protective mechanisms that lessen the impact of media influence on unhealthy behaviors. Media message processing variables from the MIP model have been found to predict adolescent sexual intentions (Scull, Malik, & Kupersmidt, 2017), and specifically, perceived realism of sexually-themed media messages has been found to moderate the relationship between adolescents’ exposure to sexual media and permissive attitudes toward casual sex (Taylor, 2005). In addition, other critical thinking constructs related to media messages have been shown to predict risk behaviors among youth. (Scull, Kupersmidt, & Erausquin, 2014; Scull, Kupersmidt, Parker, Elmore, & Benson, 2010).

The Current Study

The present study builds upon the findings from the preliminary study of Media Aware (Scull, Malik, & Kupersmidt (2014)), and evaluates its efficacy using a RCT with a health promotion control group (Morrison-Beedy at al., 2013, Jemmott et al., 2010; Jemmott et al., 1992). Media Aware is a teacher-led comprehensive sexual health and MLE program designed for middle school with the aim of improving sexual health outcomes by reaching students prior to the onset of sexual activity. It is hypothesized that, compared to students in the health promotion control condition, students in the Media Aware intervention condition would significantly improve in sexual health outcomes including reporting increased favorable attitudes, normative beliefs, and self-efficacy regarding contraception use and sexual health communication; decreased favorable attitudes and normative beliefs about teen sex, increased self-efficacy to refuse sex, and decreased intentions to have sex; and, decreased acceptance of strict gender roles and dating violence. It is also hypothesized that the program will result in changes in media-related outcomes including increased media skepticism, enhanced media deconstructions skills, and decreased perceived realism of and similarity to media messages. Media-related variables were explored as potential mediators of the program’s impact on health-related outcomes.

Methods

Program Description

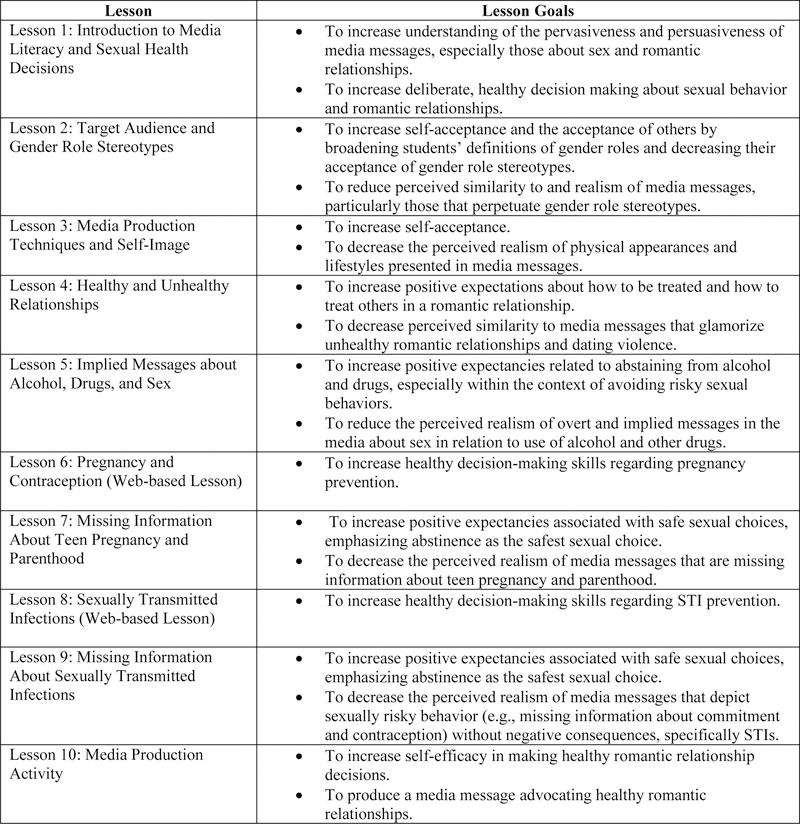

Media Aware includes ten lessons and covers a wide range of sexual and relationship health topics (Figure 1). Program development was informed by the theoretical frameworks of both the TRA/TPB and the MIP model; through changing the way that media messages are processed and by providing medically-accurate health information and skill development, the program was designed to impact key constructs outlined in the model related to healthy sexual decision-making.

Figure 1:

Media Aware Scope, Sequence, and Goals

Participants

A cluster randomized trial was used to evaluate the short-term efficacy of Media Aware. The evaluation took place in one large school district (with nine middle schools agreeing to participate) located in the Southeastern U.S. Seventh and eighth grade health teachers scheduled to teach health in the participating schools during the study timeframe (n=20) were invited, and all agreed to participate in the study. Schools were stratified based on three criteria prior to randomization: 1) percent of students eligible for free/reduced lunch; 2) reading and math scores; and, 3) traditional vs. International Baccalaureate (IBO) schools. Schools were randomly assigned to either the intervention (n=5 schools; n=11 teachers) or health promotion control (n=4 schools; n=9 teachers) group. The majority of teachers taught multiple classes of health during the same quarter. Therefore, a total of 54 health classes participated in the study, within which a total of 1,490 students were eligible.

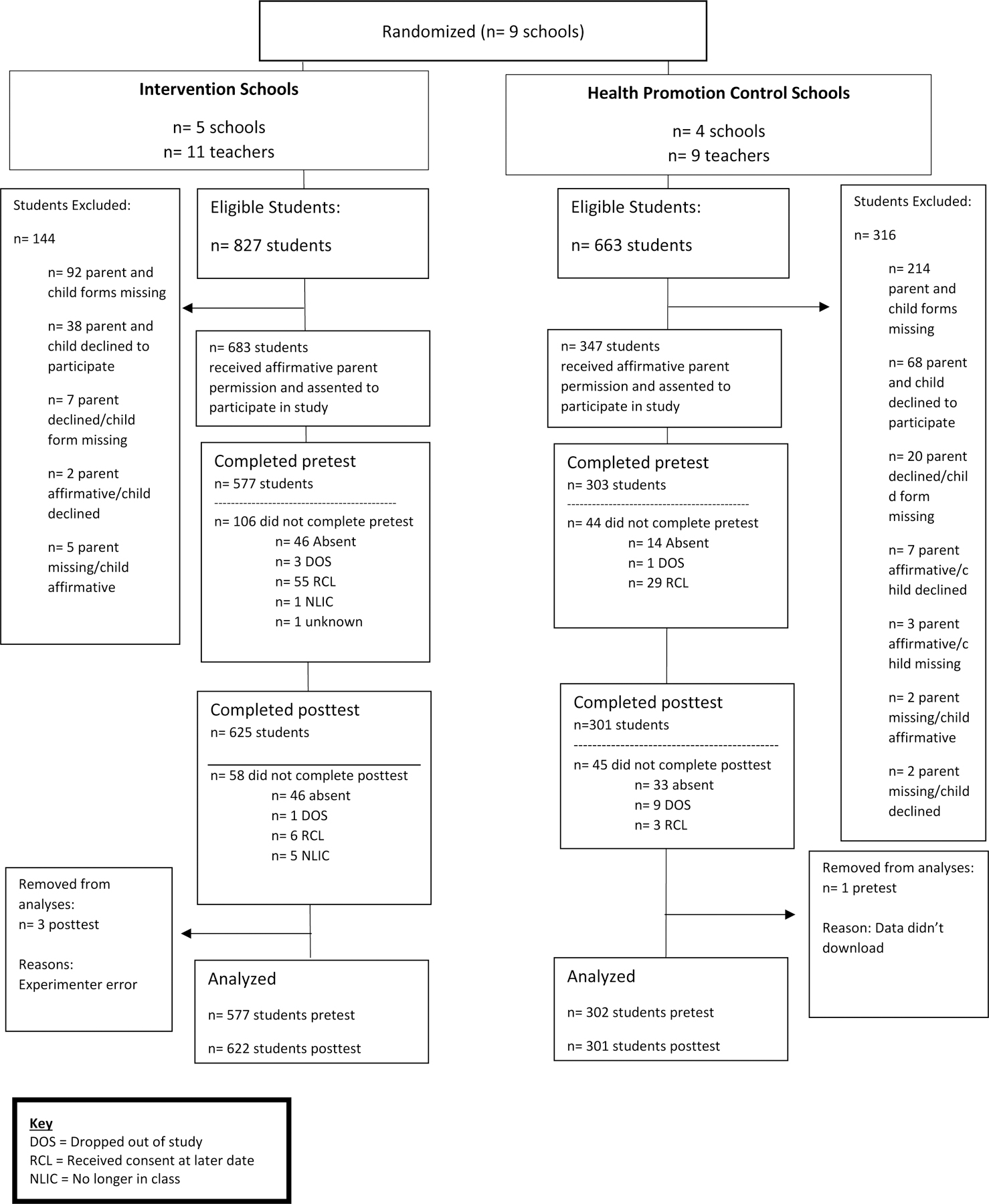

All students in participating classes were invited to take part and were provided with parental permission and student assent forms for study participation, as well as a district parental permission form for students to receive sexual health education. Affirmative parental permission and student assent forms for study participation (i.e., completion of questionnaires) were collected from 1030 students (69%) in the total sample (see Figure 2 for a CONSORT flow diagram). Different rates of consent were found between the intervention (83%) and health promotion control groups (52%). Therefore, preliminary analyses examined potential differences between groups on covariates and baseline levels of the key outcome variables using multilevel modeling. However, the rates of completion of the pretest (n=880) and posttest (n=926) were comparable for the intervention (85%; 92%) and the control (87%; 88%) groups. Data from four students were not analyzed due to a technical or human error. See Table 1 for demographic characteristics of the final sample.

Figure 2.

CONSORT Flow Diagram

Table 1.

Frequencies, Percentages, and Statistical Analyses of Participant Demographic and Background Characteristics by Condition

| Condition |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic Variable | Control | Intervention | p |

| Age (N=839) | 13.02 | 12.84 | ns |

| Gender (N=856) | ns | ||

| Male | 51.10% | 51.20% | |

| SES (N=842) | ns | ||

| Free/Reduced Lunch | 41.90% | 40.90% | |

| Ethnicity (N=846) | |||

| Hispanic/Latino | 17.63% | 16.26% | ns |

| Grade (N=851) | 0.001 | ||

| 7th | 57.30% | 39.00% | |

| 8th | 42.70% | 61.00% | |

| Race (N=801) | 0.01 | ||

| Black/African American | 13.03% | 7.85% | |

| White/Caucasian | 59.28% | 66.32% | |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 1.30% | 3.31% | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 2.28% | 3.31% | |

| Multiracial | 12.70% | 7.44% | |

| Other | 11.40% | 11.78% | |

Procedure

Prior to teaching Media Aware, intervention teachers completed a web-based teacher training program designed to familiarize them with adolescent sexual health and the Media Aware program and were provided with program materials including the teacher manual, a multi-media CD with classroom presentation, and student workbooks. As part of an evaluation of Media Aware teacher training, teachers in the control arm were provided with online access to medically-accurate information about teen sexual health. All teachers were asked to complete questionnaires before and after the training period (Scull, Kupersmidt, & Malik (in prep)).

Students who either did not have parent permission to receive sexual health education or who did not have active parent permission and/or did not assent to participate in the study were provided with an alternate activity by their teacher during the intervention and assessments. Administration of the web-based questionnaires, led by trained research staff, took approximately 45 minutes during class. Participating students received a small incentive after completing each questionnaire (e.g., a pen, earbuds). Students in the intervention classrooms received Media Aware between the pretest and posttest. Students in the health promotion control group received health promotion lessons (consisting of content determined by the school) between pretest and posttest but were asked not to teach sexual/relationship health or MLE.

To assess fidelity of implementation of Media Aware, intervention teachers completed a checklist for each lesson taught. Control teachers completed a form to describe lessons taught during the classes that occurred between the pre- and posttests. All teachers were observed teaching approximately 20% of classes during the study timeframe. Teachers were eligible for up to a $110 incentive for completing study activities outside of school time and allowed to keep the tablet device that was used for conducting the web-based observations of classroom instruction. Control teachers were also offered the opportunity to receive the program teacher training and program materials after completion of the research study. Schools received a $500 incentive.

Measures

The student questionnaires measured primary and secondary sexual health outcomes and media-related outcomes (see Table 2), as well as several demographic questions including: sex, race, ethnicity, age, grade in school, and SES (i.e., free/reduced lunch). The pattern of interscale correlations between outcome variables suggested that multicollinearity would not be a problem for the outcome analyses (see Table 3).

Table 2.

Scale information and psychometrics for primary sexual health, secondary sexual health, and secondary media-related outcome variables.

| Outcomes | Scales | # Items | Sample Item | α | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary | Intentions | |||||

| to have sexa* | 3 | How likely is it that you will have sexual intercourse in the next year? | 0.90 | 1.65 | .73 | |

| to use contraception/protectionb | 3 | If you were to decide to have sex, how likely would you be to use a condom? | 0.78 | 3.35 | .66 | |

| for sexual communication with partnerb | 3 | If you were to decide to have sex, how likely would you be to talk with a partner about pregnancy? | 0.90 | 3.32 | .67 | |

| for sexual communication with parentb | 1 | If you were to decide to have sex, how likely would you be to talk with your parent(s) or another trusted adult? | -- | |||

| for sexual communication with doctorb | 1 | If you were to decide to have sex, how likely would you be to talk with a doctor or another medical professional? | -- | |||

| Secondary | Attitudes | |||||

| about teen sexual activityc | 4 | I believe it is OK for teens to be sexually active. | 0.59 | 1.91 | .55 | |

| about contraception/protection usec | 3 | I believe a condom or dental dam should be used if a teen has oral sex. | 0.69 | 3.35 | .59 | |

| about sexual communication with partnerd | 3 | Before deciding to have sex, I believe teens should talk to their partner about pregnancy. | 0.82 | 3.20 | .70 | |

| about sexual communication with parente | 1 | Before deciding to have sex, I believe teens should talk with their parent(s) or another trusted adult. | -- | |||

| about sexual communication with doctore | 1 | Before deciding to have sex, I believe teens should talk with a doctor or another medical professional. | -- | |||

| Self-Efficacy | ||||||

| for refusing sexf | 4 | I can say no to someone who is pressuring me to have sex. | 0.86 | 3.36 | .60 | |

| for contraception/protection usef | 4 | I could use a condom correctly or explain to my partner how to use a condom correctly. | 0.86 | 2.53 | .81 | |

| about sexual communication with partnerd | 4 | I could talk to any potential partner to make him/her understand why we should use condoms or contraception. | 0.90 | 3.17 | .61 | |

| about sexual communication with parentg | 1 | I could talk to my parent(s) or another trusted adult if I had a question or was concerned about sex. | -- | |||

| about sexual communication with doctorg | 1 | I could talk to a doctor or another medical professional if I had a question or was concerned about sex. | -- | |||

| Norms | ||||||

| about teen sexual activityc* | 3 | Most of my friends believe it is OK for teens to be sexually active. | 0.78 | 2.68 | .45 | |

| about contraception/protection usec | 3 | Most of my friends believe condoms should always be used if a teen has sex. | 0.85 | 3.23 | .63 | |

| about sexual communication with partnerf | 3 | Before deciding to have sex, most of my friends believe teens should talk with their partner about pregnancy. | 0.89 | 3.20 | .70 | |

| about sexual communication with parente | 1 | Before deciding to have sex, most of my friends believe teens should talk with their parent(s) or another trusted adult. | -- | |||

| about sexual communication with doctore | 1 | Before deciding to have sex, most of my friends believe teens should talk with a doctor or another medical professional. | -- | |||

| about dating violence acceptanceh* | 3 | It is OK for a person to hit their girlfriend/boyfriend if she/he did something to make them mad. | 0.63 | 1.44 | .49 | |

| about gender role acceptanceh* | 5 | Raising children is primarily a woman’s responsibility. | 0.62 | 1.87 | .56 | |

| Media-Related | ||||||

| Media Skepticismb | 3 | The media are dishonest about what might happen if people have sex. | 0.66 | 2.94 | .72 | |

| Perceived Realismb* | 3 | Teens in the media are as sexually experienced as average teens. | 0.80 | 2.10 | .70 | |

| Perceived Similarityi* | 4 | I am like the people in the media. | 0.77 | 2.12 | .60 |

Note: 4pt. Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree to 4 = Strongly Agree)

indicates that lower value is a more favorable outcome. For all other variables a higher value indicates a more favorable outcome.

adapted from L’Engle, Brown and Kenneavy (2005)

adapted from Scull, Malik, & Kupersmidt (2014)

adapted from Basen-Engquist et al. (SRBBS; 1999)

adapted from Soet, Dudley, and DiIorio (1999) self-efficacy scale

adapted from Halpern-Felsher et al. (2004) self-efficacy scale

adapted from Soet, Dudley, and DiIorio (1999)

adapted from Halpern-Felsher et al. (2004)

adapted from Foshee et al. (2005)

adapted from Kupersmidt, Scull, & Benson (2012)

adapted from Pinkleton et al. (2008)

Table 3.

Correlation table with primary and secondary outcome variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Attitudes about teen sex | — | ||||||||||||||||||

| 2. Attitudes about contraception | −.28*** | — | |||||||||||||||||

| 3. Attitudes about communication | −.33*** | .45*** | — | ||||||||||||||||

| 4. Norms about teen sex | −.22*** | .18*** | .25*** | — | |||||||||||||||

| 5. Norms about contraception | −.27*** | .55*** | .39*** | .42*** | — | ||||||||||||||

| 6. Norms about communication | −.24*** | .27*** | .59*** | .31*** | .47*** | — | |||||||||||||

| 7. Efficacy for refusing sex | −.43*** | .38*** | .51*** | .25*** | .40*** | .36*** | — | ||||||||||||

| 8. Efficacy for contraception use | −.21*** | .10* | .08* | .07 | .06 | .07 | .04 | — | |||||||||||

| 9. Efficacy for communication | −.19*** | .41*** | .54*** | .25*** | .44*** | .42*** | .46*** | .34*** | — | ||||||||||

| 10. Intentions to have sex | .58*** | −.13** | −.23*** | −.13*** | −.17*** | −.14*** | −.39*** | .29*** | −.07* | — | |||||||||

| 11. Intentions to use contraception | −.23*** | .43*** | .36*** | .12** | .43*** | .31*** | .36*** | .06 | .37*** | −.23*** | — | ||||||||

| 12. Intentions to communicate | −.25*** | .33*** | .57*** | .19*** | .38*** | .53*** | .42*** | .14*** | .55*** | −.16*** | .49*** | — | |||||||

| 13. Sexual health knowledge | −.04 | .19*** | .18*** | .05 | .15*** | .14*** | .16*** | .00 | .18*** | .01 | .23*** | .19*** | — | ||||||

| 14. Norms about gender roles | .27*** | −.22*** | −.24*** | −.03 | −.19*** | −.22*** | −.29*** | .07* | −.25*** | .20*** | −.24*** | −.32*** | −.19*** | — | |||||

| 15. Norms about dating violence | .17*** | −.15*** | −.23*** | −.01 | −.19*** | −.17*** | −.20*** | .05 | −.16*** | .15*** | −.16*** | −.16*** | −.12** | .30*** | — | ||||

| 16. Media skepticism | −.14*** | .22*** | .25*** | .05 | .12** | .11* | .17*** | .01 | .19*** | −.01 | .16*** | .18*** | .23*** | −.12** | −.07* | — | |||

| 17. Perceived similarity | .29*** | −.07 | −.14*** | −.01 | −.08* | −.05 | −.18*** | .09* | −.10* | .32*** | −.08* | −.10* | .03 | .16*** | .12** | .02 | — | ||

| 18. Perceived realism | .15*** | −.06 | −.10** | −.02 | −.09* | −.11* | −.11* | .09* | −.06 | .16*** | −.10* | −.08* | .07* | .08* | .07* | .02 | .19*** | — | |

| 19. Deconstruction skills | −.05 | .15*** | .20*** | .05 | .10* | .10* | .15*** | .03 | .17*** | −.04 | .14 | .14 | .27*** | −.17*** | −.15*** | .24*** | −..01 | .04 | — |

Note.

p<.05

p<.001

p<.0001.

Primary sexual health outcomes included intentions to engage in the following behaviors: have sex, use contraception/protection, communicate with a partner about sexual health, communicate with a parent or another trusted about sexual health, and communicate with a doctor about sexual health.

Secondary sexual health outcomes included scales to access attitudes, normative beliefs, and self-efficacy related to teen sexual activity and sexual refusal, contraception/protection use, and sexual health communication with partners, parents or another trusted adult, and a doctor or another medical professional. In addition, the acceptance of dating violence and gender role norms were measured. Sexual health knowledge was assessed through a series of six questions (3 multiple choice and 3 true/false).

Media-related outcomes included scales to assess media skepticism, perceived realism of sexually-themed media messages, and perceived similarity to media messages. Students also completed a performance measure of media deconstruction skills adapted from established procedures used in other studies (Kupersmidt, Scull, & Austin, 2010; Kupersmidt, Scull, & Benson, 2012; Scull, Malik, & Kupersmidt (2014)). Students qualitative responses to questions about an advertisement that used sexual themes to promote an alcohol product were coded by trained project staff members, who were blind to condition, with one coder coding all data and a second coder coding at least 20% of responses (κ = .82). The overall composite variable scores could potentially range from low of 0 to high of 13.

Consumer satisfaction was determined by teachers and students in the intervention group at posttest. The teacher measure used a10-pt. scale, and the student measure used a 4-pt. scale.

Statistical analyses

The series of intention-to-treat (ITT) analyses presented in the evaluation of the efficacy of Media Aware represent a sequence of a) assessment of pre-intervention differences between Media Aware schools and comparison schools on demographic variables and b) tests of the efficacy of Media Aware, examining differences in pre-post changes over time in key outcomes. The primary models were fit in SAS Proc MIXED under maximum likelihood estimation, assuming that outcome missingness was predictable by variables that were observed, but unrelated to values of outcomes that were missing (i.e., missing-at-random, Schafer & Graham, 2002).

Multilevel models in general are geared toward partitioning variability across multiple levels of aggregation, such as individual-level repeated measures (which are clustered within individuals) where individuals are clustered within larger units. In this study, there are multiple levels of aggregation including classroom, teacher, and school levels, with each individual having their own estimated level of change for the outcome variable; variance component analyses across outcomes consistently showed that there was significant variability at the school level but not at the classroom level so, as a result, school-level random intercepts were modeled in all analyses. We can then incorporate predictors of changes in outcomes over time (most notably the intervention condition) to assess which factors were related to increases in positive outcomes, decreases in negative outcomes, or both—both within and between individuals.

Results

Media Aware versus Comparison: Covariate Differences

Differences between Media Aware and the health promotion control condition on covariates and baseline levels of the key outcomes were examined using multilevel modeling, where random intercepts were specified for the school-level; for unordered categorical covariates (e.g., race, ethnicity), random effects multinomial logit models were used. Of the demographic and baseline outcome variables examined for Media Aware/comparison baseline differences, only two were significantly different: a) differences in the distribution of race categories (p = .007), with a higher proportion of White participants in Media Aware (66%) than the comparison condition (59%) and b) differences in the distribution of grade levels (p<.001) where in Media Aware schools, 60% of students were in the 8th grade (compared to 42% for comparison schools) while the majority of students in comparison schools were in 7th grade (see Table 1). No baseline differences were observed among the outcome variables of interest. Thus, for all subsequent outcome analyses, race and grade level indicators were included as covariates.

Conventional Multilevel Models Analyses

A series of differences in change over time in outcomes across Media Aware and the comparison condition were examined. Significant differences (p<.05) in change in favor of Media Aware were observed for improving primary and secondary sexual health outcomes as well as media-related outcomes (see Table 4) compared to the control group. Moderation of intervention effects were examined by gender and all were non-significant.

Table 4.

Multilevel Modeling Parameter Estimates, Means, and Standard Deviations for Significant Intervention Findings

| Intervention M (SD) | Control M (SD) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Estimate | SE | t-value | p-value | d |

| Secondary sexual health outcomes | |||||||||

| Dating violence norms | 1.46 (.51) | 1.41 (.53) | 1.41 (.46) | 1.52 (.61) | −.16 | .06 | −2.65 | .008 | 0.17 |

| Gender role norms | 1.86 (.56) | 1.66 (.58) | 1.88 (.57) | 1.85 (.62) | −.17 | .07 | −2.58 | .009 | 0.17 |

| Sexual health knowledge | 5.50 (1.46) | 5.40 (1.10) | 5.51 (1.47) | 4.78 (1.28) | .58 | .14 | 4.18 | <.001 | 0.27 |

| Attitudes about communication with parents | 3.27 (.76) | 3.40 (.70) | 3.35 (.72) | 3.23 (.82) | .23 | .08 | 2.76 | .005 | 0.18 |

| Attitudes about communication with partner | 3.39 (.56) | 3.54 (.58) | 3.43 (.55) | 3.36 (.60) | .19 | .07 | 2.82 | .004 | 0.18 |

| Self-efficacy for contraceptive use | 2.53 (.82) | 3.03 (.63) | 2.54 (.81) | 2.64 (.83) | .42 | .09 | 4.64 | <.001 | 0.31 |

| Self-efficacy for communication with partner | 3.15 (.62) | 3.33 (.60) | 3.19 (.60) | 3.20 (.63) | .21 | .07 | 2.89 | .003 | 0.19 |

| Intentions for contraceptive use | 3.31 (.69) | 3.44 (.62) | 3.42 (.61) | 3.37 (.71) | .19 | .07 | 2.51 | .012 | 0.17 |

| Intentions to communicate with partner | 3.27 (.67) | 3.45 (.64) | 3.40 (.66) | 3.38 (.66) | .19 | .07 | 2.51 | .012 | 0.17 |

| Intentions to communicate with doctor | 3.29 (.75) | 3.50 (.64) | 3.34 (.73) | 3.30 (.77) | .30 | .10 | 3.00 | .002 | 0.20 |

| Media-related outcomes | |||||||||

| Deconstruction skills | 3.24 (1.65) | 4.78 (2.13) | 3.31 (1.53) | 3.66 (1.67) | 1.24 | .20 | 6.17 | <.0001 | 0.40 |

| Media skepticism | 2.90 (.73) | 3.08 (.78) | 3.00 (.68) | 3.01 (.71) | .17 | .09 | 2.03 | .042 | 0.13 |

Sexual Health Primary Outcomes.

Students in the Media Aware group had more intentions to use contraception, and increased intentions to communicate with a doctor or other medical professional and a romantic partner should they decide to have sex compared to the control group. No changes were seen for intentions to have sex and intentions to communicate with a parents/another trusted adult.

Sexual Health Secondary Outcomes.

Attitudes that were impacted by the program included more positive attitudes about communicating with a romantic partner, parents or another trusted adult. Attitudes about teen sexual activity was removed from the analyses due to low reliability in the measure (α = 0.59). Attitudes that were not found to change as a result of the program included attitudes about contraception use and communicating with a doctor/another medical professional.

Intervention students reported more self-efficacy for contraception use and communicating with a romantic partner at posttest compared with the control group. Self-efficacy that was not found to differ as a result of the program included self-efficacy for refusing sex and self-efficacy for communicating with parents, another trusted adult, or a doctor or another medical professional.

Norms that were impacted by the program included a reduction in the acceptance of dating violence norms and strict gender role norms. Norms that were not found to change as a result of the program included norms about teen sexual activity, contraception use, and communicating with a partner, parent, or doctor. Finally, intervention students had more sexual health knowledge at posttest compared to students in the control group.

Media-Related Outcomes.

Three self-reported measures and one performance-based measure were examined as media-related secondary outcomes. Participants’ media deconstructions skills and media skepticism increased as a result of the program. No changes were observed for perceived realism of sexually-themed media messages and perceived similarity to media messages.

Mediation Analyses

Mediation effects were tested using the Bias-Corrected Bootstrap (Williams & MacKinnon, 2008) facility in Mplus Model Indirect command to explore the significant media-related secondary outcomes (i.e., deconstruction skills and media skepticism) as potential mediators of the intervention effects on significant primary sexual health outcomes (i.e., intentions to use contraception, intentions to communicate with a medical professional, and intentions to communicate with a romantic partner). Analyses suggest that changes in deconstruction skills mediated the program’s impact on change in intentions to communicate with a doctor or other medical professional; Media Aware led to increases in media deconstruction (b = 1.241(.201), p<.001) and, in turn, increases in media deconstruction led to increases in intent to communicate with a doctor/medical professional (b = .440 (.107), p<.001). The mediation effect estimate was .546 (CI: .261, .886). However, the mediation analyses were conducted with data from one time point, and, therefore, the direction of causality cannot be guaranteed. Analyses did not reveal significant findings for any other mediation effects tested in these analyses.

Fidelity of Assigned Program Implementation

Health Promotion Control classrooms.

Teachers were instructed to teach health lessons for the period of time between the student pre- and posttest but asked to refrain from teaching MLE or sexual health programming, if possible. A variety of health subjects were taught by the control group teachers (e.g., bullying, nutrition/BMI). However, two teachers reported covering interpersonal communication and healthy/unhealthy relationships during the study period.

Media Aware classrooms.

Teachers assigned to the intervention group completed a fidelity checklist that contained a list of the topics and subtopics covered in each lesson. They recorded how much of the subtopic they taught on a scale ranging from a low of 0 (Not at All) to a high of 3 (Thoroughly). These scores were summed and divided by the maximum possible score and then multiplied by 100 to create a total fidelity percentage. All 10 lessons were taught by all teachers. Specifically, teachers reported teaching an average of 87% of program subtopics within each lesson, 95% CI [83%, 91%], range 66–99%. Twenty percent of the lessons were observed by at least one researcher. Observers and teachers agreed 97% of the time as to whether a subtopic was taught to some degree versus not covered at all.

Consumer Satisfaction Analyses

Teacher report.

Intervention teachers (n=9) believed that media literacy is an important life skill for the 21st century (M = 9.46; SD = .88); the program could be effectively used for healthful living goals (M = 8.69; SD = 2.72); students found the activities in the program to be meaningful and engaging (M = 8.69; SD = 1.03); and they would use the program in the future with another class of students (M = 9.23; SD = .83). Teachers reported that compared to their knowledge of traditional sexual education curricula, Media Aware provided an easier avenue for introducing topics on relationships and sexual health (M = 8.00; SD = 1.42).

Student report.

Students in the intervention group (n=574) thought that the lessons were interesting (M = 2.49; SD = .84); thought they learned a lot from the lessons (M = 2.94; SD = .80); were glad that they learned the lessons (M = 2.97; SD = .80); and reported they would recommend the lessons to a friend (M = 2.57; SD = .89).

Discussion

The results of this study revealed the important effects of Media Aware on adolescent sexual health outcomes, including intentions and efficacy for contraceptive use. Among sexually active teens, the average age of initiation of oral and vaginal sex is 15 years old, and of anal sex is 16 years old (Halpern & Haydon, 2012). Therefore, the middle school years are a critical time to educate students about contraception prior to sexual initiation. Interestingly, the program did not impact students’ attitudes or normative beliefs about contraception use. It is possible that students in this age group, even if they know very little about contraception, believe that contraception is something teens should use, and do use, if they are having sex. However, the program did impact self-efficacy to use contraception and intentions to do so. These constructs require more advanced knowledge and internalized beliefs about one’s own contraception use. Therefore, while the program did not impact their attitudes about teen contraception use in general or beliefs about other teens’ contraceptive use, the program may have impacted students’ ability to internalize information about contraception and apply it to their decision-making process when they think about their own future sexual activity. Media Aware also resulted in increased sexual health knowledge related to contraception, pregnancy, and STIs, serving as a manipulation check that the lesson content was learned and retained.

The program also improved outcomes related to sexual health communication. Specifically, receiving the program resulted in more positive attitudes toward sexual communication with a partner and a parent; more self-efficacy to communicate with a partner before sexual activity occurs; and greater intentions for communication about sexual health with a partner and a medical professional prior to sexual activity. Although discussing sex is often perceived as taboo in our society, sexual communication is a protective factor against risky sexual behavior. Adolescents who are able to communicate about sexual topics with their partners are more likely to engage in safer sex (Noar, Carlyle, & Cole, 2006), be older when they engage in their first intercourse (Guzman et al., 2003), and use condoms consistently once they initiate intercourse (Bryan, Fisher, & Fisher, 2002; Widman, Welsh, McNulty, & Little, 2006). As predicted within the theoretical framework of the TRA/TPB, the program impacted attitudes, self-efficacy, and intentions to communicate with a partner about sexual health before sexual activity, but did not impact normative beliefs. Since most middle school students are not sexually active and may not have engaged in any conversations about sexual health with a partner yet, their normative beliefs about this type of communication may not be changed easily. Adolescents who have more frequent discussions with their parents about sex are less likely to be sexually active (DiIorio, Kelley, & Hockenberry-Eaton, 1999; Leland & Barth, 1993), and speaking with a medical professional prior to sexual activity provides adolescents with the opportunity to obtain medically-accurate information. Surprisingly, while the program increased students’ intentions to communicate with a medical professional prior to sexual activity, it did not impact other constructs outlined in the TRA/TPB. It is possible that another process underlies the program’s impact on intentions to communicate with a medical professional, which should be explored in future research. For example, the program may have led students’ to more accurately consider their personal risk of contracting a STI or being involved in an unwanted pregnancy, if they were to have unprotected sex and subsequently increase intent to speak to a medical professional.

Media deconstruction skills mediated the program’s impact on intentions to communicate with a medical professional prior to sexual activity. The finding of the mediating role of enhanced critical thinking skills in changing health decision making is consistent with recent findings on the effectiveness of MLE as an approach to adolescent substance abuse prevention. Specifically, media deconstruction skills were found to mediate another MLE program’s impact on middle school students’ intentions to use alcohol and tobacco in the future (Kupersmidt et al., 2012). Since important sexual health information is often either inaccurate in or omitted from media messages, it is possible that enhanced critical thinking skills about media messages resulted in increased awareness of important information that is missing in media messages and a self-awareness of lacking important sexual health information before having sex. This heightened awareness of the need for accurate information may result in participants’ increased intentions to speak with a medical professional to answer their questions. Intentions to communicate with a romantic partner may not have been mediated by media deconstruction skills because a romantic partner may not be seen as a resource for providing sexual health information. Similarly, because contraception is often missing from media messages, it is understandable that media deconstruction skills would not mediate the intervention effect on intentions for contraception use. In other words, participants may deconstruct media messages and acknowledge that information about contraception is missing, but it may not motivate them to use contraception in their own lives.

Somewhat surprisingly, media skepticism did not mediate any of the intervention effects on primary sexual health outcomes. It is likely that media skepticism is related to the rejection of sexually-themed media messages that promote unhealthy behaviors. Perhaps increased skepticism reduced intentions to engage in those unhealthy behaviors. However, the intentions explored in these analyses were healthy sexual behaviors (communication and contraception use). Therefore, media skepticism may not promote intentions to engage in healthy behaviors that are more often absent from media messages but, rather, encourages the rejection of unhealthy behaviors which are more often seen in messaging. This is a direction to be explored in future research efforts.

Media Aware is a comprehensive sexual health promotion program in that it includes a broad range of related topics such as gender role stereotypes, healthy and unhealthy romantic relationships, and dating violence, in addition to content about abstinence, pregnancy, STIs, and contraception. Therefore, a secondary focus of the program was redressing unhealthy normative beliefs about dating violence and gender roles. Media Aware students reported that dating violence was less acceptable and held less strict gender role beliefs. However, due to less than ideal reliability of these measures (see Table 2), these findings should be interpreted with caution. Previous research has shown that acceptance of dating violence norms among adolescents is related to dating violence perpetration and victimization (Taylor, Sullivan, & Farrell, 2015). Furthermore, the negative impact of holding strict gender role norms on sexual health has been well-documented for both males and females (Kirby & Lepore, 2007). Previous research evaluating a program designed primarily to decrease dating violence among adolescents has found that both dating violence norms and gender role norms mediated program effects on dating violence behaviors (Foshee et al., 2005). Media Aware reduced normative beliefs about these two important, yet often neglected, components of adolescent sexual health.

Although teaching about sexual health can positively impact a plethora of outcomes, a concern of some individuals is that discussions about sex will have an iatrogenic effect of increasing adolescents’ likelihood of sexual activity. This perspective was not supported in this study as results revealed no increases in adolescents’ intentions to have sex in the future. In fact, the participating students reported low intentions to engage in sexual activity during adolescence or even prior to graduating from high school. This pattern of findings is consistent with other research that dispels the myth that comprehensive sex education contributes to early sexual activity (Kirby, 2007).

This study has two primary limitations. First, this study examined the immediate effects (i.e., pre-post) of Media Aware and was thus, unable to determine if it impacted adolescents’ behaviors related to sex and contraceptive use. Although behavioral intentions are a strong predictor of future sexual activity (Buhi & Goodson, 2007), future research is needed to explore changes in actual patterns of behavior over time. An important direction for future research is to conduct a longitudinal study to test whether participation in Media Aware results in a delay in the onset of sexual activity and an increase in contraceptive use when sexual activity begins. This design will allow for the examination of whether or not changes in the media-related outcomes found at immediate posttest are sustained over time. The second limitation of this study is that it only identified a mechanism of change for one sexual health outcome at the same time point (i.e., intent to communicate with a doctor). Future studies should address other possible mediating factors using at least three time points to determine causality. Ongoing practice and application of media analysis skills may serve to redress inaccurate normative beliefs, improve positive attitudes for health behaviors, and reduce the influence of media exposure on sexual risk behaviors through other variables that were not measured in this study.

Despite these limitations, the present study used a rigorous RCT design and found that Media Aware resulted in several favorable adolescent sexual health- and media-related outcomes and demonstrates that MLE can be an effective approach to sexual health education.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

We wish to thank the administrators, teachers, and students in the school study sites for their assistance with this project. Many thanks go to Kim Vuong, Margaret Gichane, and Jordan Price for their contributions to the research activities.

FUNDING: Research reported in this paper was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under award number R44HD061193 to the first author. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

CLINICAL TRIALS REGISTRY: http://ichgcp.net/clinical-trials-registry/NCT02359422

ABBREVIATIONS:

- MIP

Message Information Processing

- MLE

media literacy education

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES: The first three authors have a financial interest in the sale of the Media Aware program for research and prevention purposes to disclose. However, data collection for the study was completed by independent contractors, and statistical analyses were conducted by the fourth author, all without a financial interest in the program to disclose.

Contributor Information

Tracy Marie Scull, Innovation Research & Training, 5316 Highgate Dr., Suite 121, Durham, NC 27713, (919) 493-7700.

Janis Beth Kupersmidt, Innovation Research & Training, 5316 Highgate Dr., Suite 121, Durham, NC 27713, (919) 493-7700.

Christina V. Malik, Innovation Research & Training, 5316 Highgate Dr., Suite 121, Durham, NC 27713, (919) 493-7700.

Antonio A. Morgan-Lopez, RTI International, 3040 E. Cornwallis Road, Research Triangle Park, NC 27709.

References

- Ajzen I (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I, & Fishbein M (1980). Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Aufderheide P (1993). Media Literacy. A Report of the National Leadership Conference on Media Literacy Washington, DC: Aspen Institute, Communications and Society Program. [Google Scholar]

- Austin EW, & Johnson KK (1997b). Immediate and delayed effects of media literacy training on third graders’ decision making for alcohol. Health Communication, 9(4), 323–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scull TM, Kupersmidt JB, Malik CV, & Keefe EM (2018). Examining the efficacy of an mHealth media literacy education program for sexual health promotion in older adolescents attending community college. Journal of American College Health, 66(3), 165–177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scull TM, Malik CV, & Kupersmidt JB (2014). A media literacy education approach to teaching adolescents comprehensive sexual health education. Journal of Media Literacy Education, 6(1), 1–14 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scull TM, Kupersmidt JB & Malik CV (in prep) Media Aware teacher training evaluation.

- Basen-Engquist K, Masse LC, Coyle K, Kirby D, Parcel GS, Banspach S, & Nodora J (1999). Validity of scales measuring the psychosocial determinants of HIV/STD-related risk behavior in adolescents. Health education research, 14(1), 25–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleakley A, Hennessy M, Fishbein M, & Jordan A (2009). How sources of sexual information relate to adolescents’ beliefs about sex. American Journal of Health Behavior, 2009(33), 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JD, L’Engle KL, Pardun CJ, Guo G, Kenneavy K, & Jackson C (2006). Sexy media matter: Exposure to sexual content in music, movies, television and magazines predicts black and white adolescents’ sexual behavior. Pediatrics, 117(4), 1018–1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan A, Fisher JD, & Fisher WA (2002). Tests of the mediational role of preparatory safer sexual behavior in the context of the theory of planned behavior. Health Psychology, 21(1), 71–80. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.21.1.71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhi ER, & Goodson P (2007). Predictors of adolescent sexual behavior and intention: a theory-guided systematic review. J Adolesc Health, 40(1), 4–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.09.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016). School Health Policies and Practices Study (SHPPS) Retreived from https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/shpps/pdf/shpps-results_2016.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Chandra A, Martino SC, Collins RL, Elliott MN, Berry SH, Kanouse DE, & Miu A (2008). Does watching sex on television predict teen pregnancy? Findings from a national longitudinal survey of youth. Pediatrics, 122(5), 1047–1054. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL (2011). Content analysis of gender roles in media: where are we now and where should we go? Sex Roles, 64(3–4), 290–298. doi: 10.1007/s11199-010-9929-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Elliott MN, Berry SH, Kanouse DE, Kunkel D, Hunter SB, & Miu A (2004). Watching sex on television predicts adolescent initiation of sexual behavior. Pediatrics, 114(3), e280–289. doi: 10.1542/peds.2003-1065-L [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiIorio C, Kelley M, & Hockenberry-Eaton M (1999). Communication about sexual issues: Mothers, fathers, and friends. Journal of Adolescent Health, 24, 181–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyal K, Kunkel D, Biely EN, & Finnerty KL (2007). Sexual socialization messages on television programs most popular among teens. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 51(2), 316–336. doi: 10.1080/08838150701304969 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foshee VA, Bauman KE, Ennett ST, Suchindran C, Benefield T, & Linder GF (2005). Assessing the effects of the dating violence prevention program “Safe Dates” using random coefficient regression modeling. Prev Sci, 6(3), 245–258. doi: 10.1007/s11121-005-0007-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goesling B, Colman S, Trenholm C, Terzian M, & Moore K (2014). Programs to reduce teen pregnancy, sexually transmitted infections, and associated sexual risk behaviors: A systematic review. Journal of Adolescent Health, 54(5), 499–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzman BL, Schlehofer-Sutton MM, Villanueva CM, Dello Stritto ME, Casad BJ, & Feria A (2003). Let’s talk about sex: How comfortable discussions about sex impact teen sexual behavior. J Health Commun, 8(6), 583–598. doi: 10.1080/716100416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern CT, & Haydon AA (2012). Sexual timetables for oral-genital, vaginal, and anal intercourse: Sociodemographic comparisons in a nationally representative sample of adolescents. American Journal of Public Health, 102(6), 1221–1228. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2011.300394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemmott JB III, Jemmott LS, Fong GT, & Morales KH (2010). Effectiveness of an HIV/STD risk-reduction intervention for adolescents when implemented by community-based organizations: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Public Health, 100(4), 720–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemmott JB III, Jemmott LS, Spears H, Hewitt N, Cruz-Collins M. Self-efficacy, hedonistic expectancies, and condom-use intentions among inner-city Black adolescent women: a social cognitive approach to AIDS risk behavior. J Adolesc Health 1992;13(6):512–519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong SH, Cho H, & Hwang Y (2012). Media literacy interventions: A meta-analytic review. J Commun, 62(3), 454–472. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2012.01643.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaestle CE, Halpern CT, & Brown JD (2007). Music videos, pro wrestling, and acceptance of date rape among middle school males and females: An exploratory analysis. J Adolesc Health, 40(2), 185–187. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kann L, McManus T, Harris WA, Shanklin SL, Flint KH, Queen B, ... & Lim C (2018). Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance—United States, 2017. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 67(8), 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kann L, McManus T, Harris WA, Shanklin SL, Flint KH, Hawkins J, . . . Zaza S (2016). Sexual identity, sex of sexual contacts, and health-related behaviors among students in grades 9–12—United States and selected sites, 2015. MMWR. Surveillance Summaries, 65 Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/pdf/2015/ss6506_updated.pdf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby D (2007). Emerging Answers 2007: Research Findings on Programs to Reduce Teen Pregnancy and Sexually Transmitted Diseases Washington, DC: National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy. [Google Scholar]

- Kirby D, & Lepore G (2007). Sexual Risk & Protective Factors Scotts Valley, CA: ETR. [Google Scholar]

- Kirby DB, Laris BA, & Rolleri LA (2007). Sex and HIV education programs: Their impact on sexual behaviors of young people throughout the world. J Adolesc Health, 40(3), 206–217. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.11.143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupersmidt JB, Scull TM, & Austin EW (2010). Media literacy education for elementary school substance use prevention: Study of Media Eetective. Pediatrics, 126(3), 525–531. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupersmidt JB, Scull TM, & Benson JW (2012). Improving media message interpretation processing skills to promote healthy decision making about substance use: The effects of the middle school Media Ready curriculum. J Health Commun, 17(5), 546–563. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2011.635769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leland NL, & Barth RP (1993). Characteristics of adolescents who have attempted to avoid hiv and who have communicated with parents about sex. Journal of Adolescent Research, 8(1), 58–76. doi: 10.1177/074355489381005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martino SC, Collins RL, Elliott MN, Strachman A, Kanouse DE, & Berry SH (2006). Exposure to degrading versus nondegrading music lyrics and sexual behavior among youth. Pediatrics, 118(2), e430–441. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison-Beedy D, Jones SH, Xia Y, Tu X, Crean HF, & Carey MP (2013). Reducing sexual risk behavior in adolescent girls: results from a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Adolescent Health, 52(3), 314–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noar SM, Carlyle K, & Cole C (2006). Why communication is crucial: Meta-analysis of the relationship between safer sexual communication and condom use. J Health Commun, 11(4), 365–390. doi: 10.1080/10810730600671862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardun CJ, L’Engle KL, & Brown JD (2005). Linking exposure to outcomes: early adolescents’ consumption of sexual content in six media. Mass Communication & Society, 8(2), 75–91. doi: 10.1207/s15327825mcs0802_1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pinkleton BE, Austin EW, Chen YC, & Cohen M (2012). The role of media literacy in shaping adolescents’ understanding of and responses to sexual portrayals in mass media. J Health Commun, 17(4), 460–476. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2011.635770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Primack BA, Gold MA, Schwarz EB, & Dalton MA (2008). Degrading and non-degrading sex in popular music: A content analysis. Public Health Reports, 123, 593–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rideout VJ (2015). The common sense census: Media use by tweens and teens. Common Sense Media Incorporated [Google Scholar]

- Satterwhite CL, Torrone E, Meites E, Dunne EF, Mahajan R, Ocfemia MC, . . . Weinstock H (2013). Sexually transmitted infections among US women and men: prevalence and incidence estimates, 2008. Sex Transm Dis, 40(3), 187–193. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318286bb53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL, & Graham JW (2002). Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods, 7(2), 147–177. doi: 10.1037//1082-989x.7.2.147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scull TM, Kupersmidt JB, & Erausquin JT (2014). The impact of media-related cognitions on children’s substance use outcomes in the context of parental and peer substance use. J Youth Adolesc, 43(5), 717–728. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-0012-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scull TM, Kupersmidt JB, Parker AE, Elmore KC, & Benson JW (2010). Adolescents’ media-related cognitions and substance use in the context of parental and peer influences. J Youth Adolesc, 39(9), 981–998. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9455-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scull TM, Malik CV, & Kupersmidt JB (2017). Understanding the unique role of media message processing in predicting adolescent sexual behavior intentions in the United States. Journal of Children and Media DOI: 10.1080/17482798.2017.1403937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soet JE, Dudley WN, & Dilorio C (1999). The effects of ethnicity and perceived power on women’s sexual behavior. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 23(4), 707–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor KA, Sullivan TN, & Farrell AD (2015). Longitudinal relationships between individual and class norms supporting dating violence and perpetration of dating violence. J Youth Adolesc, 44(3), 745–760. doi: 10.1007/s10964-014-0195-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor LD (2005). Effects of visual and verbal sexual television content and perceived realism on attitudes and beliefs. J Sex Res, 42(2), 130–137. doi: 10.1080/00224490509552266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Department of Economic & Social Affairs. (2014). Demographic Yearbook New York: United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- Ward LM (2002). Does television exposure affect emerging adults’ attitudes and assumptions about sexual relationships? Correlational and experimental confirmation. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 31(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Ward LM, Reed L, Trinh SL, & Foust M (2014). Sexuality and entertainment media. In Tolman DL & Diamond LM (Eds.), APA Handbook of Sexuality and Psychology: Vol. 2. Contextual Approaches (Vol. 2, pp. 373–423). [Google Scholar]

- Widman L, Welsh DP, McNulty JK, & Little KC (2006). Sexual communication and contraceptive use in adolescent dating couples. J Adolesc Health, 39(6), 893–899. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams J, & MacKinnon DP (2008). Resampling and distribution of the product methods for testing indirect effects in complex models. Structural equation modeling : a multidisciplinary journal, 15(1), 23–51. doi: 10.1080/10705510701758166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]