Abstract

Purpose

Longitudinally visualizing relative blood flow speeds within choroidal neovascularization (CNV) may provide valuable information regarding the evolution of CNV and the response to vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) inhibitors.

Design

Retrospective, longitudinal case series conducted at the New England Eye Center.

Participants

Patients with either treatment-naïve or previously treated CNV secondary to neovascular age-related macular degeneration.

Methods

Optical coherence tomography angiography (OCTA) was performed using a 400-kHz, 1050-nm swept-source oCt system with a 5-repeat B-scan protocol. Variable interscan time analysis (VISTA) was used to compute relative flow speeds from pairs of B-scans having 1.5- and 3.0-ms separations; VISTA signals then were mapped to a color space for display.

Main Outcome Measures

Quantitative outcomes included OCTA-based area and volume measurements of CNV at initial and follow-up visits. Qualitative outcomes included VISTA OCTA analysis of relative blood flow speeds, along with analysis of contraction, expansion, densification, and rarefication of CNV.

Results

Seven eyes of 6 patients (4 women and 2 men) with neovascular age-related macular degeneration were evaluated. Two eyes were treatment naïve at the initial visit. Choroidal neovascularization in all eyes at each visit showed relatively higher flow speeds in the trunk, central, and larger vessels and lower flow speed in the small vessels, which generally were located at the periphery of the CNV complex. Overall, the CNV appeared to expand overtime despite retention of good visual acuity in all patients. In the treatment-naïve patients, slower-flow-speed vessels contracted with treatment, whereas the larger vessels with higher flow speed remained constant.

Conclusions

Variable interscan time analysis OCTA allows for longitudinal observations of relative blood flow speeds in CNV treated with anti-VEGF intravitreal injections. A common finding in this study is that the main trunk and larger vessels seem to have relatively faster blood flow speeds compared with the lesions’ peripheral vasculature. Moreover, an overall growth of chronically treated CNV was seen despite retention of good visual acuity. The VISTA framework may prove useful for developing clinical end points, as well as for studying hemodynamics, disease pathogenesis, and treatment response.

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is a leading cause of vision loss for people 50 years of age or older in the developed world.1,2 Neovascular AMD (nAMD) is a late stage of AMD characterized by the growth of abnormal blood vessels above or below the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE).1,3–5 The longitudinal changes occurring in the morphologic features of the neovascularization with treatment remain incompletely understood.1,6,7 Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) plays a role in regulating the growth and exudation of neovascularization, and intravitreal anti-VEGF injections are effective to treat these lesions. However, the exact pathophysiologic response of the neovascularization after anti-VEGF injection is a continuing area of research.7,11–14

Optical coherence tomography angiography (OCTA) is a noninvasive imaging method that has allowed further insight into the structural anatomic features of neovascularization15–18 and its response to anti-VEGF treatment.8,19–22 The underlying principle of OCTA is to use the intrinsic flow contrast provided by moving blood cells to differentiate blood flow from surrounding static tissue. Optical coherence tomography angiography works by acquiring repeated OCT B-scans from the same tissue location and then processing the data to extract the time-varying components, which correspond to blood flow. In a standard OCTA display, bright (white) pixels represent motion, corresponding to the presence of flowing blood cells, and dark (black) pixels indicate the absence of flowing blood cells. Artifacts in OCTA from motion and projection may complicate this basic relationship.23 When OCTA volumes are resliced and viewed along en face planes, the resulting display shows a map of the retinal and choroidal vasculature. Compared with traditional dye-based angiography, OCTA has the advantage of being noninvasive and depth resolved, the latter of which allows the different vascular plexuses to be visualized independently.

Visualization of retinal microvasculature obtained with OCTA continues to improve our understanding of neovascularization in AMD. In an OCTA study, Spaide8 proposed that, as a result of anti-VEGF injection for neovascularization, newly sprouted vessels are pruned, resulting in increased vascular resistance in the remaining vessels and higher flow in the main vascular trunk. Although current OCTA systems provide insight into the presence, absence, and structure of the neovascular lesions, they provide limited information about blood flow speeds within the vessels. Our research group from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and New England Eye Center (NEEC) recently developed a general hardware–software framework, termed variable interscan time analysis (VISTA), capable of computing relative blood flow speeds from time-series OCTA data.24,25 Variable interscan time analysis works by acquiring more than 2 repeated OCT B-scans at each retinal location and then computationally forming OCTA images of different interscan times using subsets of these repeated scans.24 The key concept is that OCTA images at different interscan times capture different flow information.26–29 Optical coherence tomography angiography signals in these images with different interscan times then can be compared in a variety of ways to derive information about the relative blood flow speeds in the vasculature. For example, a recent publication by Ploner et al25 demonstrated a ratio-based VISTA scheme that mapped these relative flow speeds into a color-coded map for easy visualization.

In the current study, VISTA OCTA was used to evaluate choroidal neovascularization (CNV) secondary to nAMD longitudinally and to follow the progression of vessel maturation after anti-VEGF treatment. The aim of this analysis was to gain a better understanding of the structural and hemodynamic changes that occur in CNV with anti-VEGF therapy.

Methods

Participants

This retrospective longitudinal study was conducted at the NEEC of Tufts Medical Center (Boston, Massachusetts). The study was approved by the Tufts Medical Center Institutional Review Board. Participants underwent a complete ophthalmic examination by a trained retina specialist (either NKW, CRB, JSD, or AJW) at the NEEC. Select patients with a new diagnosis of CNV secondary to nAMD, or a known history of CNV secondary to nAMD, were imaged on a prototype swept-source (SS) OCT device after written informed consent was obtained. This research adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and complied with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996.

Swept-Source OCT and Swept-Source OCT Angiography

Optical coherence tomography and OCTA were performed using an ultrahigh-speed SS-OCT research prototype device developed at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and deployed at the NEEC. This OCT system has been described previously in detail.30 Briefly, the prototype SS-OCT device uses a vertical cavity surface-emitting laser with a 400-kHz A-scan rate. Compared with commercial spectral-domain OCT devices, which use a 840-nm center wavelength, the vertical cavity surface-emitting laser light source has a 1050-nm center wavelength, which enables better penetration through opaque media and deeper penetration through the RPE and choroid.31 Recent studies also have found that longer-wavelength SS-OCT and OCTA better visualizes and detects CNV compared with shorter-wavelength spectral-domain OCT and OCTA systems.32–34 The full-width-at-half-maximum axial and transverse optical resolutions in tissue were approximately 8 to 9 pm and 20 μm, respectively.

Optical coherence tomography angiography imaging was performed over both 3 × 3- and 6 × 6-mm fields of view, centered on the fovea. For each acquisition, 5 repeated B-scans were obtained at 500 uniformly spaced locations. Each B-scan consisted of 500 A-scans. For each B-scan, the acquisition time, accounting for the mirror scanning duty cycle, was approximately 1.5 ms; the total volume acquisition time was approximately 3.9 seconds. The volumetric scan pattern yields isotropic transverse sampling of the retina at 12- and 6-pm intervals for the 6 × 6- and 3 × 3-mm field sizes, respectively. To compensate for patient motion and to improve image quality, 2 orthogonally scanned volumes were acquired from each eye and subsequently were registered and merged using a previously published algorithm.35,36 To assess repeatability of the VISTA OCTA images, 3 × 3- and 6 × 6-mm VISTA OCTA images, acquired one after the other, were compared (Fig 1).

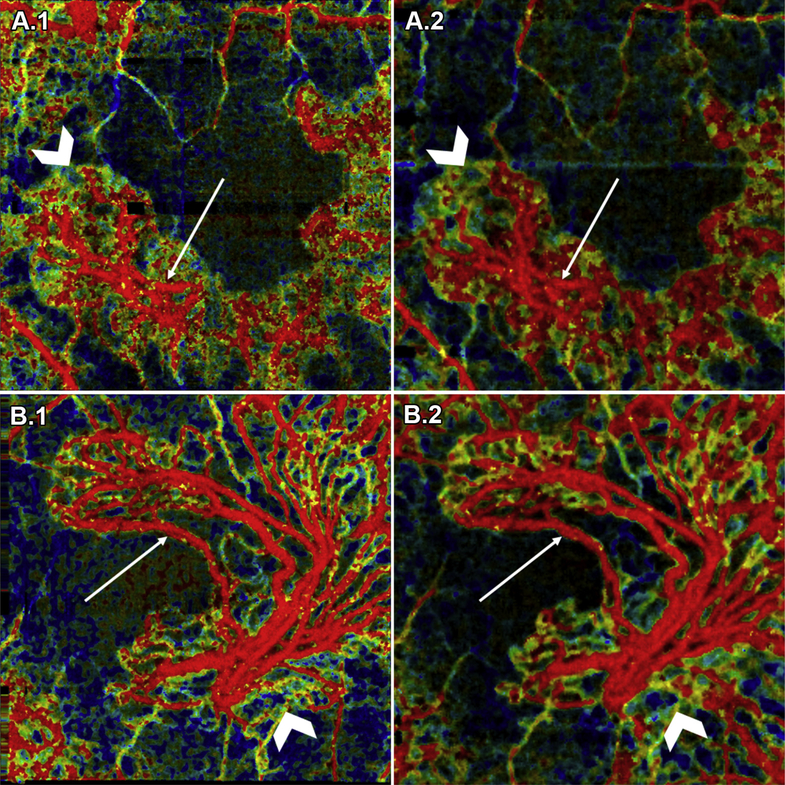

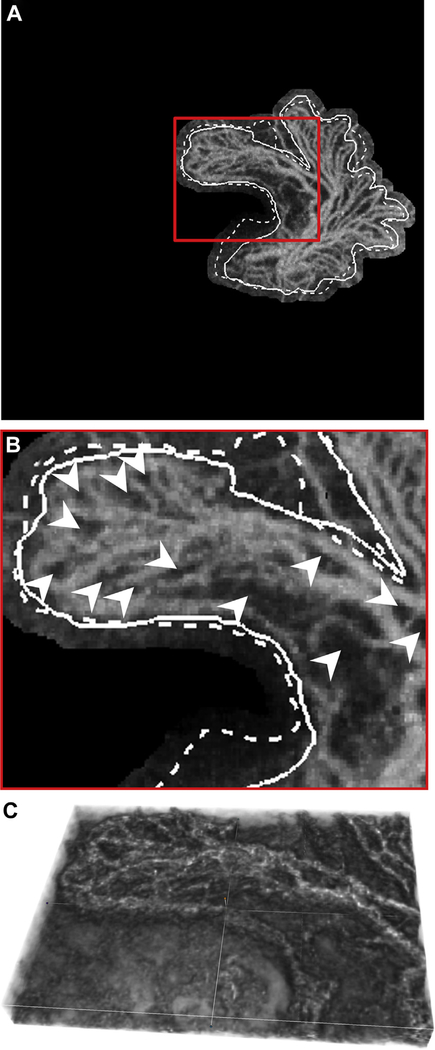

Figure 1.

Repeatability of variable interscan time analysis (VISTA) OCT angiography (OCTA): (A) choroidal neovascularization (CNV) in patient 6; (B) CNV in patient 5; (A.1, B.1) 3 × 3-mm VISTA OCTA image and (A.2, B.2) 6 × 6-mm VISTA OCTA image cropped to a 3 × 3-mm scan area. For each case, the different scan sizes were obtained approximately 2 minutes apart. White arrows point to vessels with high flow speed (red on VISTA OCTA images), and white chevrons point to vessels with slow flow speed (blue-green on VISTA OCTA images). Note the consistency in blood flow speeds between repeated acquisitions.

Choroidal Neovascularization OCT Angiography and Variable Interscan Time Analysis OCT Angiography Image Generation

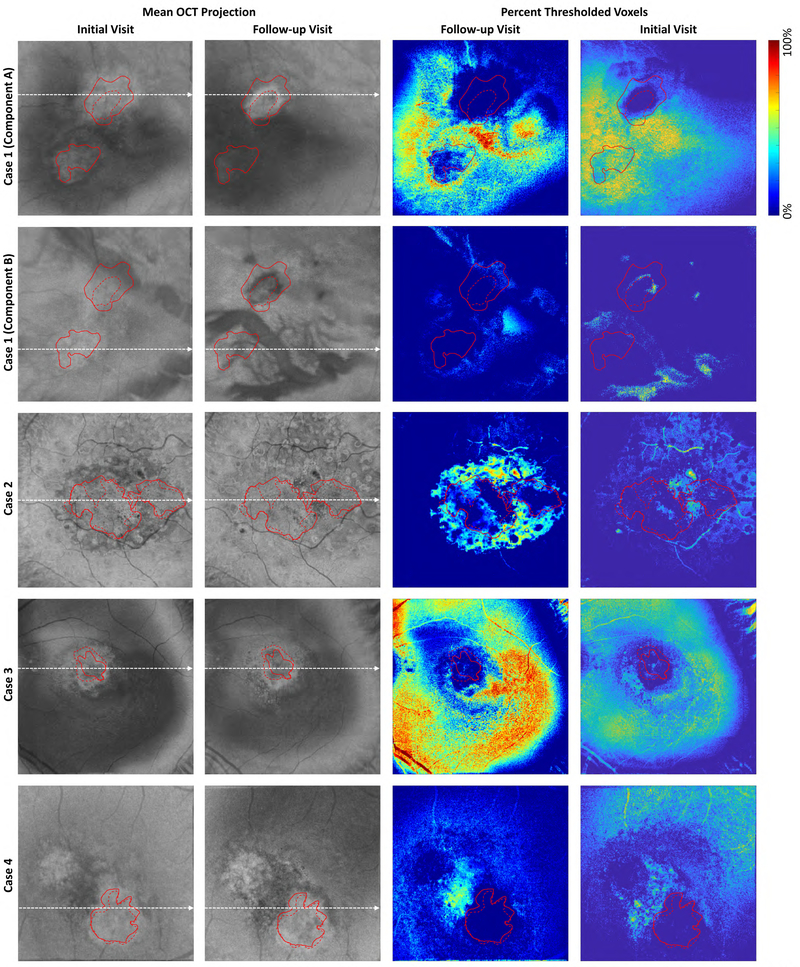

Volumetric OCTA data corresponding to 1.5- and 3.0-ms interscan times were formed using the VISTA framework and an amplitude-based decorrelation scheme.24,25 These data then were projected (using mean projection) through the depths spanned by the CNV to generate en face OCTA images corresponding to the 1.5- and 3.0-ms interscan times. Specifically, for each CNV, the axial (depth) position of the anterior-most aspect of the CNV and the axial (depth) position of the posterior-most aspect of the CNV were used as the boundaries for projection (Fig 2, available at www.ophthalmologyretina.org); note that because the volumes were not segmented, the projection bounds intersected different layers at locations away from the lesions. Because of this, for clarity of presentation, these areas away from the lesion boundaries were set to black in the displayed en face images.

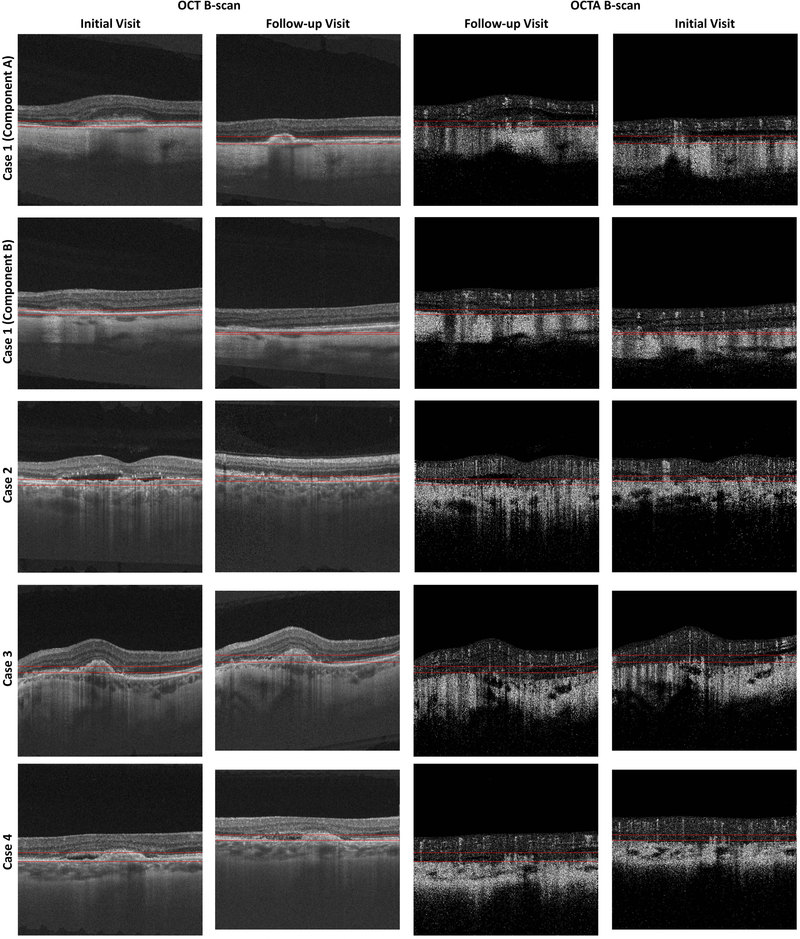

Figure 2A:

OCT and OCTA B-scans showing the projection boundaries for Cases 1–4. These projection boundaries were used to trace the lesion margins and form VISTA images. Columns 1 and 2 show OCT B-scans from the initial and follow-up visits, respectively. Columns 3 and 4 show OCTA B-scans from the initial and follow-up visits, respectively. The locations from which these B-scans were taken are indicated by the dashed white arrows in Figure 10A and Figure 10B. Note that because the scans from the following visits are not registered, the selected B-scans do not correspond to the exact same positions on the retina. The horizontal red lines indicate the boundaries between which the OCTA signal was projected when forming en face OCTA and en face VISTA images. Note that for Case 1 we used two different projection ranges, one for each component of the lesion. For all cases, except Case 7, the same projection boundaries were used to trace the lesion margins and to compute the VISTA signal; for the initial visit of Case 7 different projection boundaries were used for margin tracing and VISTA computation.

The projected en face OCTA images of the CNV then were mapped to a color-coded display using the published ratio-based ViSTa OCTA scheme.25 The methodology has been described previously by Choi et al24 and Ploner et al.25 In brief, this VISTA OCTA algorithm works by using the ratio of the 3.0-ms interscan time OCTA signal to the 1.5-ms interscan time OCTA signal as the input to the hue (color) channel of the display; this channel is related to the blood cell speed. The maximum of the 3.0-ms interscan time OCTA signal and the 1.5-ms interscan time OCTA signal are used as the input to the brightness channel of the signal; this channel is related to the blood cell flux.

Preprocessing for Longitudinal Analysis of OCT Angiography and Variable Interscan Time Analysis OCT Angiography Data

Longitudinal Image Registration. Contours from an initial visit and a follow-up visit were registered (i.e., spatially aligned) using a custom MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, MA) script: first, corresponding control points (i.e., fiducials) from the en face OCTA images of the 2 analyzed visits were selected manually (at least 3 control points were chosen). These registration points were chosen at bifurcations in the larger retinal vessels, rather than features on the lesion itself, under the assumption that bifurcations of larger vessels would be relatively stationary between visits, unlike the lesion’s vasculature, which may change significantly between visits. For most cases, the control points were selected on the same en face projections used to analyze the CNV vessels; this was possible because the retinal vessels are visible as projection artifacts (i.e., decorrelation tails). In cases in which the projected retinal vasculature did not provide adequate features for registration, we formed separate en face projections of the retinal vasculature for registration. These separate en face projections of the retinal vasculature are intrinsically coregistered to the en face CNV images and therefore can be used for registration. Second, a rigid transformation (i.e., a transformation made up of a rotation and a translation) of the contour was estimated using the iterative closest point algorithm. This transformation was used as described in the following section.

Longitudinal Comparison of Lesion Boundaries

To compare lesions at the initial imaging session spatially with lesions at a follow-up imaging session, a contour was drawn to demarcate the boundary of the lesion on the first visit, and using the transformation described in the preceding section, this contour was overlaid onto the OCTA data of the follow-up visit. Analogously, a contour was drawn to demarcate the boundary of the lesion on the follow-up visit, and using the inverse transformation, this contour was overlaid onto the OCTA data of the first visit. For display clarity, the contour of the initial visit was indicated with a solid line and the contour of the follow-up visit was indicated with a dashed line (e.g., Fig 3B, C, E and F).

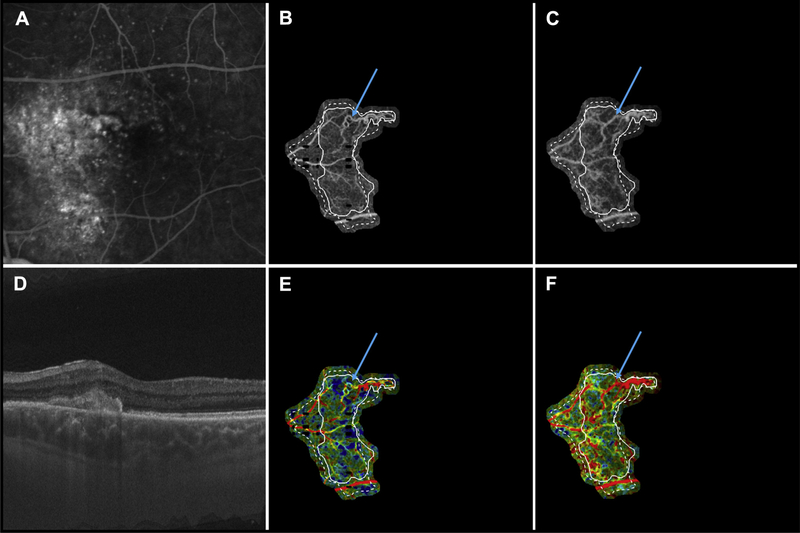

Figure 3.

Multimodal longitudinal imaging of chronic choroidal neovascularization (CNV) in patient 7. Images were obtained 21 months apart. A, Fluorescein angiography image cropped to same area as the OCT angiography (OCTA) image. B, Optical coherence tomography angiography image of CNV at the initial visit, when the patient’s visual acuity was 20/100. C, Optical coherence tomography angiography image of CNV at the follow-up visit, when the patient’s visual acuity was 20/25. D, Optical coherence tomography B-scan at the follow-up visit. E, Variable interscan time analysis (VISTA) OCTA image of CNV at the initial visit. F, Variable interscan time analysis OCTA of CNV at the follow-up visit. Solid lines correspond to the CNV boundary at the initial visit, and dashed lines correspond to the CNV boundary at the follow-up visit. Note the expansion of the CNV vasculature between the initial and follow-up visits. Note that the expansion of vasculature is accompanied by an increase in high flow-speed characteristics (red in the VISTA OCTA images). Blue arrows point to a region of a vessel that was tortuous, with slow flow speed (yellow in the VISTA OCTA images) in the initial visit, but has straightened and acquired high speed flow (red in the VISTA OCTA images) in the follow-up visit.

OCT Angiography and Variable Interscan Time Analysis OCT Angiography Lesion Analysis

Quantitative OCT Angiography Analysis of Choroidal Neovascularization Dimensions: 2-Dimensional and 3-Dimensional Measures (Longitudinal)

The area and volume of the CNV were analyzed quantitatively. Area was computed, in MATLAB, using the boundary contours from the initial and follow-up visits (described in the preceding section). The volume was determined by manually tracing the boundary of the CNV, 1 en face slice at a time (each slice corresponds to an en face section, approximately 4.5 μm in the axial dimension). The tracing was performed using SlicerOCT, a custom extension of the open-source program 3D Slicer (available at www.slicer.org).37,38 With knowledge of the field size and A-scan sampling density, measurement outputs in pixels were converted to physical units of square millimeters and cubed millimeters for area and volume, respectively.

Qualitative Variable Interscan Time Analysis OCT Angiography Analysis of Relationship between Choroidal Neovascularization Components and Blood Flow Speed (Cross-Sectional)

The OCTA VISTA signal was analyzed at each of the following 5 regions. Trunk vessel was defined as a vessel from which the CNV emanates visibly. Not all CNV have a clearly identifiable trunk vessel. Large vessel was defined as a vessel with diameter larger than, or equal to, half the width of a retinal artery leaving the optic disc (approximately 60 μm). Small vessel was defined as a vessel with diameter smaller than half the width of a retinal artery leaving the optic disc. Choroidal neovascularization center was defined as the center of gravity of the CNV (i.e., the balance point one would compute assuming each pixel belonging to the CNV has a mass of 1 unit). A CNV need not have a center that corresponds to lesion vasculature (see patient 7; Fig 4). Choroidal neovascularization periphery was defined as those parts of the lesion away from the CNV center, or at the margins of the lesion.

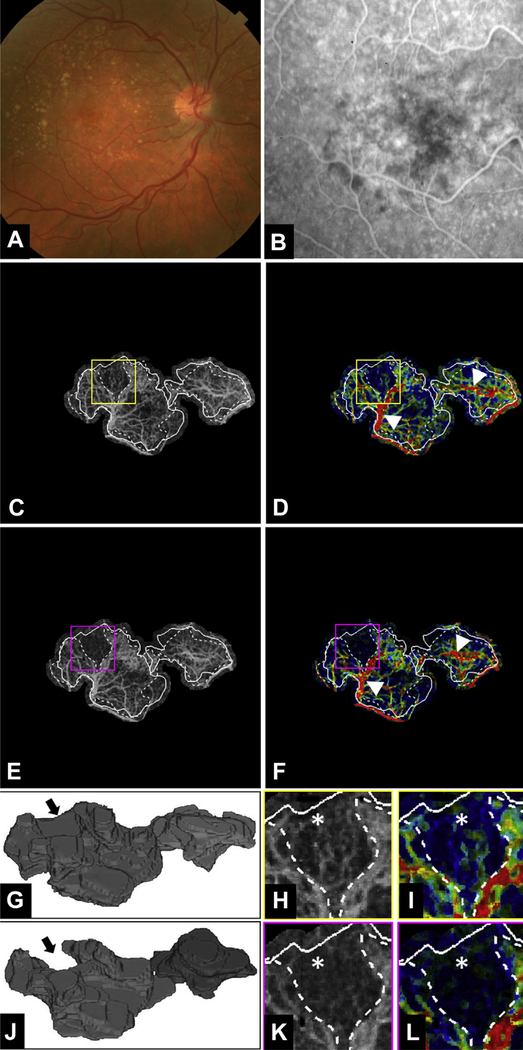

Figure 4.

Multimodal longitudinal imaging of choroidal neovascularization (CNV) in patient 2 before and 1 month after the first anti–vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) treatment. A, Color fundus photograph. B, Fluorescein angiography image cropped to same area as the OCT angiography (OCTA) image. C, D, Optical coherence tomography angiography and variable interscan time analysis (VISTA) OCTA images, respectively, of the CNV at the initial visit, before anti-VEGF injection. Yellow boxes are enlarged in (H) and (I) to demonstrate regional contraction of CNV vasculature. In each OCTA and VISTA OCTA image, solid lines correspond to the CNV boundary from the initial visit and dashed lines correspond to the CNV boundary from the follow-up visit. E, F, Optical coherence tomography angiography and VISTA OCTA images, respectively, of the CNV at the follow-up visit, 1 month after the first anti-VEGF injection. Magenta boxes are enlarged in (K) and (L). White arrowheads in (D) and (F) highlight trunk vessels and larger vessels that retain high-speed flow (red) after anti-VEGF treatment. G, J, Three-dimensional model of the CNV before and 1 month after the first anti-VEGF treatment. Black arrows indicate an area of vasculature that was present on initial imaging but not visible at the follow-up visit. H, I, Enlarged regions of the CNV from the initial and follow-up visits, respectively. White asterisks denote area of vasculature seen at the initial visit but not visible at the follow-up visit (K and L). Note that (I) the VISTA OCTA image from the initial visit shows slow flow speeds (blue) in the region (K and L) that has contracted in the follow-up visit. Note that in (G) and (J), the voxels are anisotropic, with the axial dimension being stretched by a factor of 10 so as to visualize better the 3-dimensional structure of the lesion.

Specifically, for each of the above categories, the regions or components of the CNV belonging to that category were noted (i.e., there could be one, more than one, or no region or component; e.g., in the case of CNV with multiple large vessels, each large vessel is considered to be a component). For each CNV component, the VISTA OCTA signal was graded as fast (orange-red), slow (blue-green), or mixed (either a mixture of fast and slow, or hues between green and orange) blood flow speeds. If all the components of a particular category (e.g., all large vessels) had fast or slow flows, that (overall or summary) category was noted as having fast or slow flows, respectively; if some components had fast flows and some had slow flows (e.g., some large vessels had fast flows and others had slow flows) or mixed speed flows, that category was noted as having mixed flows.

Qualitative OCT Angiography Analysis of Changes in Lesion Structure (Longitudinal)

Each initial visit and follow-up pair was analyzed by noting the presence or absence of each of the following 4 categorical changes: contraction of the lesion, as indicated by a certain region having an OCTA signal at the initial visit and no OCTA signal in the same region at the follow-up visit; expansion of the lesion, as indicated by a certain region having no OCTA signal at the initial visit and having an OCTA signal in the same region at the follow-up visit; densification of the lesion, as indicated by a certain region having denser vasculature at the follow-up visit as compared with the same region at the initial visit; and rarefication of the lesion, as indicated by a certain region having sparser vasculature at the follow-up visit as compared with the initial visit. We further subcategorized the following changes as corresponding to large vessels or small vessels (see preceding section).

Qualitative Variable Interscan Time Analysis OCT Angiography Analysis of Relationship between Changes in Lesion Structure and Blood Flow Speed Changes (Longitudinal)

For each of the qualitative changes in CNV structure, as described in the previous section, we characterized the vessels involved in the changes as corresponding predominantly to fast flow or slow flow. For this part of the analysis, for the sake of reducing the number of possible combinations, we did not use the mixed speed flow category.

Results

Patient Demographics

We performed VISTA OCTA on 7 eyes of 6 patients with CNV secondary to nAMD. Case descriptions are displayed in Table 1, organized by increasing length of follow-up. Four women and 2 men were included in our analysis; all were white. The treatmentnaïve patients (n = 2) were scanned at the initial visit and at 1-month follow-up. The chronic patients (n = 5) were followed up for an average of 17 months (range, 10–21 months). In terms of specific anti-VEGF treatment, patients 6 and 3 received aflibercept only, and patient 7 received bevacizumab only. Patient 5 received 3 bevacizumab treatments initially and then 40 aflibercept treatments, whereas patient 4 initially received 12 bevacizumab treatments and then 12 aflibercept treatments. All patients were treated with the treat-and-extend strategy, although this was at the discretion of the physician.

Table 1.

Case Descriptions

| Patient No. by Category | Patien Age (yrs) | No. of Anti—Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Treatments before Initial Visit | Time between First Treatment and Initial Visit (mos) | Visual Acuity at Initial Visit | No. of Anti—Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Treatments between Initial and Follow-up Visits | Visual Acuity at Follow-up Visit | Time between Visits (mos) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment naïve | |||||||

| 1 | 66 | 0 | N/A | 20/40 | 1 | 20/30 | 1 |

| 2 | 65 | 0 | N/A | 20/70 | 1 | 20/70 | 1 |

| Chronic | |||||||

| 3 | 75 | 17 | 33 | 20/30 | 5 | 20/40 | 10 |

| 4 | 63 | 15 | 30 | 20/20 | 9 | 20/40 | 18 |

| 5* | 83 | 25 | 29 | 20/30 | 17 | 20/30 | 18 |

| 6* | 83 | 6 | 25 | 20/30 | 2 | 20/30 | 19 |

| 7 | 56 | 2 | 3 | 20/100 | 4 | 20/25 | 21 |

| Mean (SD) | 70.1 (10.4) | 13.0 (9.1)† | 24 (12.1)† | 20/46 | 7.4 (5.9)† | 20/33 | 17.2 (4.2)† |

N/A = not applicable; SD = standard deviation.

Left eye and right eye, respectively, from the same patient.

Only from chronic cases.

Quantitative Analysis

The quantitative analysis of CNV dimensions is shown in Table 2. Both treatment-naïve patients showed a decrease in area and volume at the 1-month follow-up visit. Patient 2 is highlighted in Figure 4. For patient 1, component B was not present on OCTA at the follow-up visit (Fig 5). In contrast, 4 of the patients with chronic CNV showed growth in terms of both area and volume, whereas one patient (patient 4) showed decrease in both area and volume over the follow-up (Fig 6). Of the chronic CNV patients, patient 3 had the largest growth (more than 200% increase in, or tripling of, volume). Figure 7 demonstrates a chronic patient (patient 6) who showed an increased in volume.

Table 2.

Quantitative Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography Analysis of Choroidal Neovascularization Dimensions (Longitudinal)

| Initial Visit |

Follow-up Visit |

Change* |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient No. by Category | Area (mm2) | Volume (mm3) | Area (mm2) | Volume (mm3) | Area (mm2) | Volume (mm3) |

| Treatment naïve | ||||||

| 1 | ||||||

| Component A | 0.45 | 0.02 | 0.16 | 0.01 | −0.30 (−65.65%) | −0.01 (−43.73%) |

| Component B | 0.28 | 0.01 | 0 | 0 | −0.28 (N/A) | −0.01 (N/A) |

| Total | 0.74 | 0.03 | 0.16 | 0.01 | −0.58 (−78.91%) | −0.02 (−64.92%) |

| 2 | ||||||

| Component A | 3.13 | 0.10 | 2.63 | 0.09 | −0.5 (−16.02%) | −0.02 (−15.62%) |

| Component B | 1.42 | 0.04 | 1.08 | 0.04 | −0.34 (−23.77%) | +0.00 (+7.69%) |

| Total | 4.55 | 0.14 | 3.71 | 0.13 | −0.84 (−18.44%) | −0.01 (−9.38%) |

| Chronic | ||||||

| 3 | 0.52 | 0.02 | 0.96 | 0.07 | +0.44 (+84.72%) | +0.05 (+239.37%) |

| 4 | 2.00 | 0.12 | 1.76 | 0.08 | −0.23 (−11.61%) | −0.04 (−31.83%) |

| 5 | 4.49 | 0.39 | 4.92 | 0.40 | +0.43 (+9.68%) | +0.01 (+3.56%) |

| 6 | 5.88 | 0.42 | 8.45 | 0.60 | +2.57 (+43.62%) | +0.17 (+31.74%) |

| 7 | 2.29 | 0.07 | 3.17 | 0.09 | +0.87 (+38.00%) | +0.02 (+30.94%) |

N/A = not applicable.

+ = growth; − = shrinkage. Percentage changes were defined as 100% × (B – A)/A, where A is the value at the initial visit and B is the value at follow-up.

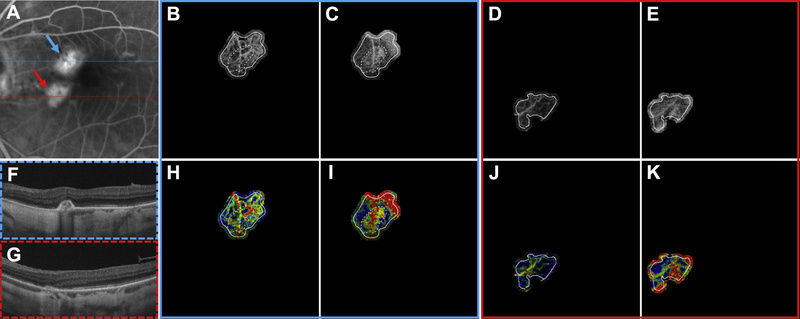

Figure 5.

Multimodal longitudinal imaging of treatment-naïve choroidal neovascularization (CNV) in patient 1 before and 1 month after the first anti–vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) treatment. A, Fluorescein angiography image cropped to same area as the OCT angiography (OCTA) image. The blue arrow corresponds to component A (B, C, H, and I). The red arrow corresponds to component B (D, E, J, and K). Blue and red dashed lines mark the location from which the OCT B-scans in (F) and (G) were extracted, respectively. Solid white lines correspond to the CNV boundary at the initial visit, and dashed white lines correspond to the CNV boundary at the follow-up visit. B, Optical coherence tomography angiography image of component A at the initial visit, when the patient’s visual acuity was 20/40. C, Optical coherence tomography angiography image of component A at the follow-up visit, when the patient’s visual acuity was 20/30. D, Optical coherence tomography angiography image of component B at the initial visit. E, Optical coherence tomography angiography image of component B at the follow-up visit. Note that component B was not appreciable at the follow-up visit, hence the lack of dashed white lines on the images of component B. F, G, Structural OCT B-scans of component A and component B, respectively, at the follow-up visit. H, Variable interscan time analysis (VISTA) OCTA of component A at the initial visit. I, Variable interscan time analysis OCTA of component A at the follow-up visit. Note the contraction of the CNV vasculature between the initial visit and follow-up visits. Additionally, note that the contraction of vasculature is accompanied by an increase in high flow-speed characteristics in the remaining vasculature (red in the VISTA OCTA images). J, Variable interscan time analysis OCTA of component B at the initial visit. Note that the entire component is composed of vessels with slow flow speed (blue on VISTA OCTA images). K, Variable interscan time analysis OCTA of component B at the follow-up visit. There was no appreciable vasculature of component B at the follow-up visit, and the vessels seen are a combination of projection artifacts and deeper choroidal vasculature.

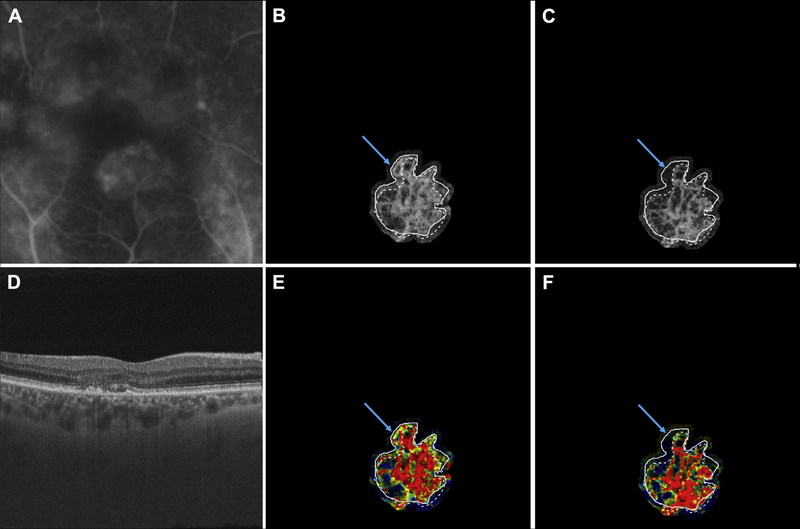

Figure 6.

Multimodal longitudinal imaging of chronic choroidal neovascularization (CNV) in patient 4. Images were obtained 18 months apart. A, Fluorescein angiography image cropped to same area as the OCT angiography (OCTA) image. B, Optical coherence tomography angiography image of CNV at the initial visit, when the patient’s visual acuity was 20/20. C, Optical coherence tomography angiography image of CNV at the follow-up visit, when the patient’s visual acuity was 20/40. D, Optical coherence tomography B-scan at the follow-up visit. E, Variable interscan time analysis (VISTA) OCTA of CNV at the initial visit. F, Variable interscan time analysis OCTA of CNV at the follow-up visit. Solid lines correspond to the CNV boundary contour at the initial visit and dashed lines correspond to the CNV boundary contour at the follow-up visit. Note the contraction of the CNV vasculature between the initial visit and follow-up visit (blue arrows). This CNV was the only chronic CNV to decrease in both area and volume between the initial and follow-up visits. Additionally, note that the vasculature that contracted between visits initially was mixed speed flow (yellow-green) and was located at the periphery of the CNV, whereas the more stable vasculature, in the central part of the CNV, retained high speed flow (red in the VISTA OCTA images).

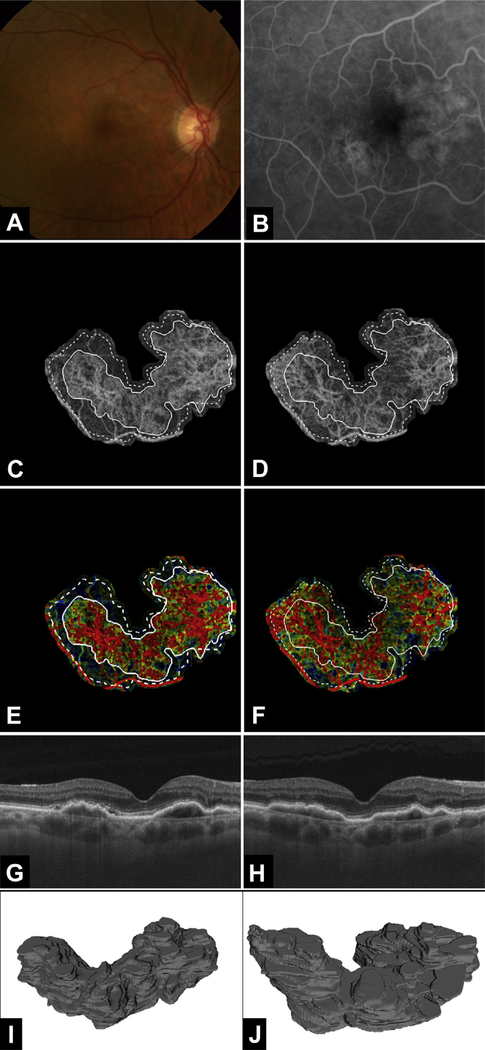

Figure 7.

Multimodal longitudinal imaging of chronic choroidal neovascularization (CNV) in patient 6. Images were obtained 19 months apart. A, Color fundus photograph. B, Fluorescein angiography image cropped to same area as the OCT angiography (OCTA) image. C, Optical coherence tomography angiography image of CNV at the initial visit, when the patient’s visual acuity was 20/30. D, Optical coherence tomography angiography image of CNV at the follow-up visit, when the patient’s visual acuity was 20/30. E, Variable interscan time analysis (VISTA) OCTA image of CNV at the initial visit. F, Variable interscan time analysis OCTA image of CNV at the follow-up visit. Solid lines correspond to the CNV boundary at the initial visit and dashed lines correspond to the CNV boundary at the follow-up visit. Note the expansion of the CNV vasculature between the initial visit and follow-up visit. Additionally, note that the expansion of vasculature is accompanied by an increase in high flow-speed characteristics (red in the VISTA OCTA images). G, H, Optical coherence tomography B-scans at the initial visit and follow-up visit, respectively. I, J, Three-dimensional model of CNV at (I) the initial visit and (J) the follow-up visit. Note the enlargement of the lesion from (I) to (J). Note that in (I) and (J), the voxels are anisotropic, with the axial dimension being stretched by a factor of 10 so as to visualize better the 3-dimensional structure of the lesion.

Qualitative Analysis

Table 3 shows the VISTA OCTA analysis of the relationship between different CNV components and their blood flow speeds. An entry of n/a corresponds to the case in which a given component was not visible on OCTA.

Table 3.

Qualitative Variable Interscan Time Analysis OCT Angiography Analysis of the Relationship between Choroidal Neovascularization Components and Blood Flow Speed (Cross-Sectional)

| Initial Visit |

Follow-up Visit |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient No. by Category | Trunk | Large Vessels | Small Vessels | Lesion Center | Lesion Periphery | Trunk | Large Vessels | Small Vessels | Lesion Center | Lesion Periphery |

| Treatment naïve | ||||||||||

| 1 | ||||||||||

| Component A | N/A | Mixed | N/A | Fast | Slow | N/A | Fast | N/A | Fast | Mixed |

| Component B | N/A | Slow | N/A | Slow | Slow | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 2 | ||||||||||

| Component A | Fast | Fast | Slow | Fast | Slow | Fast | Fast | Slow | Fast | Slow |

| Component B | Fast | Fast | Slow | Fast | Slow | Fast | Fast | Slow | Fast | Slow |

| Total (slow/mixed/fast) | 0/0/2 | 1/½ | 2/0/0 | 1/0/3 | 4/0/0 | 0/0/2 | 0/0/3 | 2/0/0 | 0/0/3 | 2/1/0 |

| Chronic | ||||||||||

| 3 | N/A | Mixed | Slow | Fast | Slow | N/A | Fast | Mixed | Fast | Slow |

| 4 | Fast | Fast | N/A | Fast | Mixed | Fast | Fast | N/A | Fast | Mixed |

| 5 | Fast | Fast | N/A | Fast | Fast | Fast | Fast | N/A | Fast | Fast |

| 6 | Fast | Fast | Mixed | Fast | Mixed | Fast | Fast | Mixed | Fast | Slow |

| 7 | N/A | Fast | Slow | N/A | Mixed | N/A | Fast | Mixed | N/A | Mixed |

| Total (slow/mixed/fast) | 0/0/3 | 0/¼ | 2/1/0 | 0/0/4 | 1/3/1 | 0/0/3 | 0/0/5 | 0/3/0 | 0/0/4 | 2/2/1 |

N/A = not applicable.

Tables 4 and 5 (both available at www.ophthalmologyretina.org) show the VISTA OCTA analysis of the relationship between changes in lesion structure and changes in blood flow speeds for the treatment-naïve patients and chronic patients, respectively. Contracting, expanding, densifying, and rarefying regions were analyzed in terms of their change, or lack thereof, from slow or no flow to fast flow, or from fast flow to slow or no flow.

Table 4.

Treatment Naïve: Qualitative VISTA-OCTA Analysis of Relationship Between Changes in Lesion Structure and Blood Flow Speed Changes (Longitudinal)

| slow/no flow → slow/no flow | slow/no flow → fast flow | fast flow → slow/no flow | fast flow → fast flow | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contracting Regions | Larger Vessels | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Smaller Vessels | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Expanding Regions | Larger Vessels | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Smaller Vessels | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| Densifying Regions | Larger Vessels | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Smaller Vessels | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| Rarefying Regions | Larger Vessels | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Smaller Vessels | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | |

Table 5.

Chronic: Qualitative VISTA-OCTA Analysis of Relationship Between Changes in Lesion Structure and Blood Flow Speed Changes (Longitudinal)

| slow/no flow → slow/no flow | slow/no flow → fast flow | fast flow → slow/no flow | fast flow → fast flow | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contracting Regions | Larger Vessels | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Smaller Vessels | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Expanding Regions | Larger Vessels | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Smaller Vessels | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| Total | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| Densifying Regions | Larger Vessels | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Smaller Vessels | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| Rarefying Regions | Larger Vessels | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Smaller Vessels | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | |

| Total | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | |

In the treatment-naïve patients (Table 4, available at www.ophthalmologyretina.org), there were 2 expanding regions within the CNV, and both of these retained fast flow between the initial and follow-up visits. The 2 densifying regions within the treatment-naïve CNV both displayed changes from slow or no flow to fast flow. Conversely, the 2 rarefying lesions within the treatmentnaïve CNV both displayed changes from fast flow to slow or no flow.

In the chronic CNV patients (Table 5, available at www.ophthalmologyretina.org), there was no consistent pattern of blood flow speeds in either the expanding, contracting, or rarefying regions. There were 2 densifying regions within the chronic CNV cases, and both went from slow or no flow to fast flow, similar to the densifying regions in the treatment-naïve patients.

Discussion

Optical coherence tomography angiography has given clinicians and researchers a new way to visualize CNV secondary to nAMD. Optical coherence tomography angiography allows for fast, noninvasive visualization of the retinal and choroidal vasculature that can be performed sequentially, at multiple follow-up visits, and without the risk of adverse side effects. In the present study, we longitudinally evaluated CNV with a prototype SS-OCT device and used the recently developed VISTA OCTA algorithm to study blood flow speeds within components of the imaged lesions. All of the CNV in our study showed high flow speed in the trunk vessels with VISTA OCTA. There is some debate as to whether these trunk vessels represent feeder or draining vessels.8,16,39 The VISTA OCTA observations from the current study revealed higher flow speeds in these large trunk vessels and slower flow speeds in the branches originating from the trunks.

Our study found that with anti-VEGF treatment of CNV the main trunk vessels matured in 4 of the 5 chronically treated CNV cases. Maturation of CNV can be defined as vessels that become larger and often more expansive and occupy a larger proportion of the lesion. This may be a result of reducing the number of vessels at the periphery of the CNV, which have relatively slower flow and are more susceptible to contraction in response to anti-VEGF therapy when compared with the more stable trunk and larger vessels.

Although the exact pathophysiologic characteristics of CNV are not fully understood, histopathologic analysis and, more recently, OCTA have provided insights into the natural history and evolution of chorioretinal neovascular lesions. Choroidal neovascularization is known to grow and mature through many biological processes, including angiogenesis and arteriogenesis. Angiogenesis, the formation of new blood vessels from preexisting vasculature, results in the CNV sprouting small, capillary-like vascular networks. Vascular endothelial growth factor, which is released from both the RPE and the vascular endothelial cells in response to an upregulation of proangiogenic cytokines, is necessary for the angiogenesis of CNV.40–42 In turn, this increase in VEGF leads to new vessel formation through a stepwise biological pathway.43 As the new vessels mature, platelet-derived growth factor acts to recruit pericytes and smooth muscle cells to surround the new vessels, helping to stabilize the bare endothelium.42 As soon as pericytes encompass the endothelium, these cells produce locally acting VEGF to continue the process. Moreover, a study by Sarks et al44 showed that leaky vessels are not covered by pericytes. Although VEGF is the principle agent in angiogenesis, platelet-derived growth factor is the driving factor in arteriogenesis, the process by which arterioles increase in diameter in response to increased shear stress on the wall of the vessel.45

It has been hypothesized that anti-VEGF therapies prevent and reverse angiogenesis, but do not affect arteriogenesis. Prior OCTA studies have shown the evolution of changes associated with both treatment-naïve20,21 and anti-VEGF-treated22,39 CNV. In a case study of a single treatment-naïve CNV patient, Huang et al21 prospectively imaged the CNV before and after treatment at various intervals from 1 day to 6 weeks after treatment. They found that the CNV showed a dramatic shutdown of blood flow within the first 2 weeks and that channels reopened by weeks 4 through 6.21 Muakkassa et al20 longitudinally evaluated a series of 6 treatment-naïve lesions and found shrinkage of peripheral vessels and fine vessels of the CNV with anti-VEGF treatment. Kuehle-wein et al22,39 showed that in mature, chronically treated CNV, although the small vessels at the periphery of the CNV shrink with treatment, the main feeder trunk vessels remain unchanged. In line with these previous works, in the present study we found that treated CNV showed minimal changes in the trunk and larger vessels, whereas the smaller vessels at the periphery of the CNV were more susceptible to contraction with anti-VEGF treatment.

Although previous studies have used OCTA to evaluate the structure of CNV and have studied structural changes in lesions after treatment, to our knowledge, the present study is the first to analyze the blood flow speeds within the lesions explicitly. Using our recently developed VISTA OCTA algorithm, we observed faster blood flow in the trunk vessels, central vessels, and larger vessels and slower flow in the smaller vessels, generally located toward the periphery of the lesions. Spaide8 proposed that as CNV are treated with anti-VEGF injections, newly sprouted vessels are pruned, leading to increased vascular resistance in the CNV circuit. Over repeated anti-VEGF treatments, wall stress secondary to the increased flow in the main trunk of the CNV leads to recruitment of pericytes and growth of the abnormal vessels, or their so-called abnormalization, which means that they are less susceptible to treatment with anti-VEGF agents.8 The results from our study of blood flow speeds seem to lend support to this hypothesis, with an increase in the size and extent, as well as a straightening of the high flow speed vessels that could represent the abnormalized vessels proposed by Spaide8 (Figs 3 and 7).

In the current study, we found a consistent pattern of growth and evolution of CNV. Although both treatment-naïve lesions initially contracted, most of the chronic CNV showed increases in size and flow speeds, forming an expanding neovascular net underneath the retina or RPE over long-term follow-up. This growth occurred despite anti-VEGF therapy that may keep the leakage under control and yield excellent visual acuities (all 5 chronic patients had 20/40 or better visual acuity and 3 had 20/30 or better visual acuity). There was an increasing percentage of vessels with high speed flow as peripheral vessels were shut down by the anti-VEGF treatment. We theorize that the vessels that develop into high-flow and high-speed trunk vessels may be surrounded by pericytes that provide locally acting VEGF. At the same time, small peripheral vessels of the CNV may lack pericytes and therefore may be more susceptible to the decrease in VEGF available secondary to anti-VEGF injections.

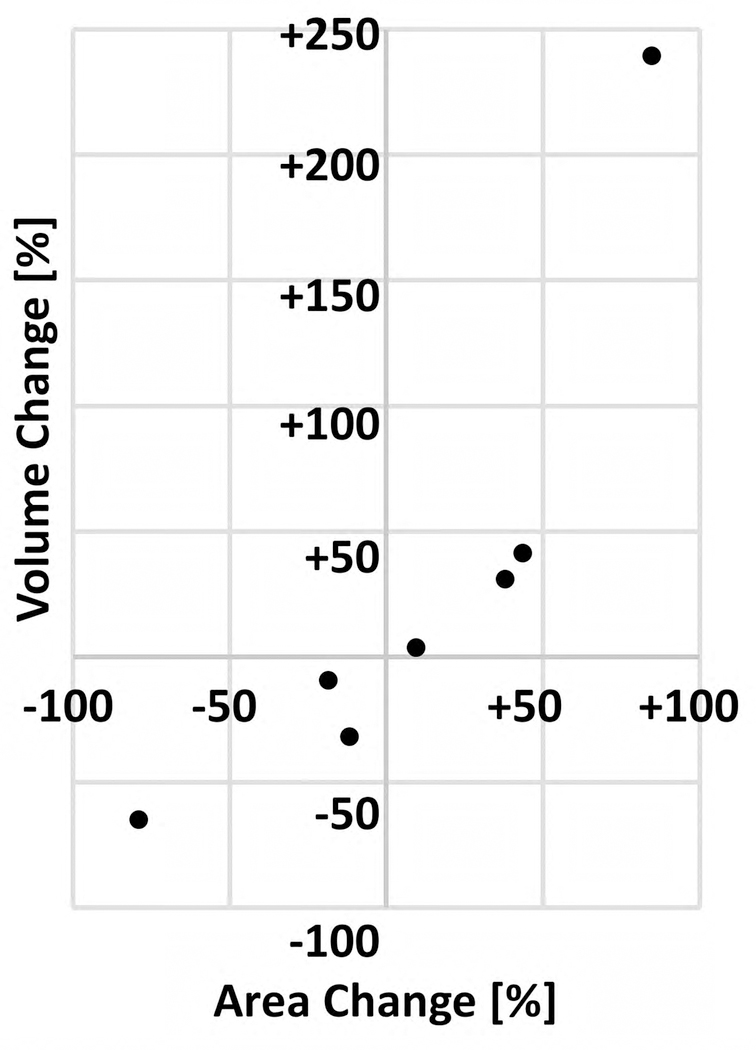

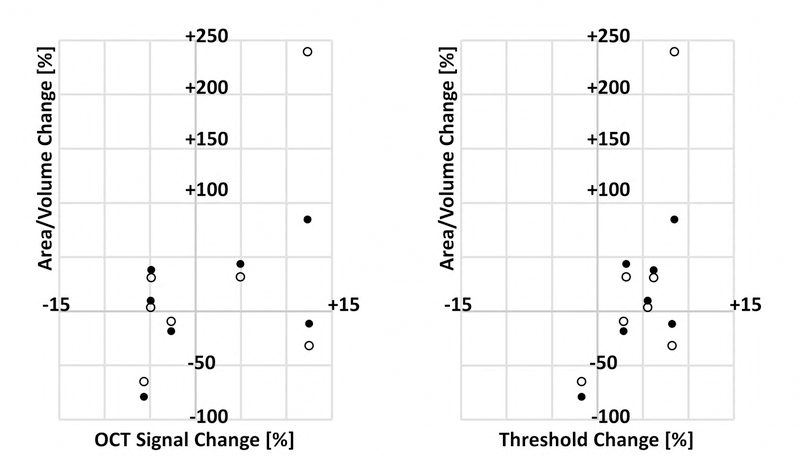

It is also worth commenting on our use of area and volume to measure dimensional changes in the CNV between visits. Compared with area measurements, which are used commonly,32,34,46 volumetric analysis is relatively rare,47–51 and to our knowledge, this study is the first to perform volumetric measurements of CNV. It is important to note that a change in the lesion volume need not be related directly to the change in lesion area (e.g., if a lesion grows solely in the axial direction, its volume will change but its area will not). However, in our study, the sign (i.e., + or −) of volume change was the same as that for area change in all 7 eyes (Fig 8, available at www.ophthalmologyretina.org). In theory, a volumetric measurement captures more information—namely, axial information—than does an area measurement. In practice, however, because of projection artifacts (Fig 9), this may not be the case. Specifically, the decorrelation tails of the CNV can lead to an overestimation of CNV volume measurement; furthermore, changes in the axial position of the lesion may create longer (if the lesion moves anteriorly) or shorter (if the lesion moves posteriorly) decorrelation tails, which may induce a position dependence in the volume measurement. Nevertheless, we believe that, with future advances in image processing and artifact suppression,52,53 volume measurements may prove to be superior over area measurements. A final note on our measurement techniques is merited: in this study, we used lesion boundary to refer to the minimal contour (in the case of area) or surface (in the case of volume) containing all the vasculature within the CNV. As shown in Figure 9, this definition, although convenient, is flawed if there are vascular-free regions within the lesion (e.g., between vessels), and a tracing of the CNV vessels themselves would produce more accurate measurements. However, because of limited resolution and the density and number of vessels comprising many of the lesions, individual vessel segmentation is extremely time consuming to perform by hand; automated techniques may prove to be useful in this regard.54,55

Figure 8:

Comparison of area and volume measurement techniques. Each dot corresponds to a single case, where the percent change is taken between the initial and follow-up visits. Percentage change was defined as 100% x (B-A)/A, where A is the value on the initial visit, and B is the value on the follow-up visit.

Figure 9.

Limitations of boundary-based and volumetric measurements. A, Choroidal neovascularization (CNV) in patient 5. B, Enlargement of the red box in (A). Although the solid line demarcates the boundary of the lesion, we can see that there are gaps between vessels inside the boundary (arrowheads); in this way, boundary-based measurements overestimate the lesion size. Dashed lines correspond to the CNV boundary contour at the follow-up visit. C, Volume rendering of the region shown in (B). Note how the decorrelation tails cause the vasculature to persist in the axial direction, which causes an overestimation of CNV volume, as well as a position dependence, as described in “Discussion.” Note that the voxels in (C) are isotropic (i.e., the axial and transverse pixel dimensions are the same).

The present study has several limitations. First, the number of studied eyes is small (n = 7), particularly when considering those that are treatment naïve (n = 2). The small cohort means that the results of this study may not generalize to larger cohorts. However, the goal of our study was to evaluate flow changes, and because the morphologic vascular changes in our patients were similar to those already reported in the literature in larger studies, we believe that the changes that we see are likely representative of what would be seen in a larger cohort. Second, we used a prototype SS-OCT device that was not equipped with eye tracking, leading some of the acquired volumes to have motion artifacts. However, this limitation was somewhat mitigated by registering 2 orthogonally acquired volumes, which, although producing some areas of gapped data (e.g., Figs 2A.1 and 3B, E), provides motion correction in both the axial and transverse directions, which is not possible using eye tracking alone. Third, the accuracy of the VISTA algorithm is dependent on the OCTA data quality, which in turn is dependent on the OCT data quality. Thus, poor focus, eye motion, and optical opacities all can reduce the accuracy of the VISTA images. These factors are particularly important when comparing data acquired at different time points: for example, if the OCT focus is suboptimal at one of the visits, the OCT, OCTA, and VISTA data all may be altered as a result, causing a portion of the data to be incorrect or uninterpretable. To mitigate the risk of such factors affecting our analysis, for all eyes we compared signal strengths and threshold levels (Figs 10 and 11 and Table 6, available at www.ophthalmologyretina.org). This analysis revealed no evidence that the changes in signal strengths between visits affected our analysis. Fourth, we have not yet formally evaluated the repeatability of VISTA; however, by comparing 3 × 3-mm scans with 6 × 6-mm scans of the same patient at the same visit, we informally provided some evidence of VISTA repeatability. Note that comparing 3 × 3-mm images with 6 × 6-mm images also assesses the sensitivity of VISTA to A-scan sampling density (because the number of A-scans per B-scan is held constant, 3 × 3-mm fields are sampled twice as densely as are 6 × 6-mm fields). Also note that most patients were scanned at least twice (and often multiple times) at the same visit, thereby providing repeatability and reproducibility data. These data will be published as part of a separate publication that looks at VISTA repeatability and reproducibility in healthy and diseased eyes. Fifth, as for any longitudinal data, the effect of different projection ranges also needs to be considered; incorrectly chosen projection ranges can create artifacts in the OCT, OCTA, and VISTA data that may masquerade as, or hide, true longitudinal changes. To reduce such potential errors, we inspected all data volumetrically in an orthoplane manner and carefully selected en face OCTA projections that best visualized the CNV. Sixth, inherent in OCTA is the risk of OCTA-related artifacts, including thresholding and projection artifacts that remove or add vasculature. The former is particularly important in cases with fluid leakage, because this fluid reduces the number of photons reaching the lesion, weakening the signal. Again, such errors were minimized by viewing structural (OCT) and angiographic (OCTA) data in a coregistered, volumetric manner, as well as analyzing signal strength and thresholding data (Figs 10 and 11 and Table 6, available at www.ophthalmologyretina.org). Viewing the OCT data alongside the OCTA data is particularly useful for reducing thresholding artifact-related errors. Finally, it is also important to note that the currently used VISTA OCTA algorithm provides information about relative blood flow speeds, as opposed to absolute blood flow speeds; that is, it can be used to make statements about whether the blood flow in a certain vessel is flowing faster or slower than that in another vessel, but it does not measure a physical flow speed. Quantitative, absolute measurements of flow speed clearly are desirable. It is our hope that in the future, the VISTA framework will be extended to allow for truly quantitative blood flow measurement.

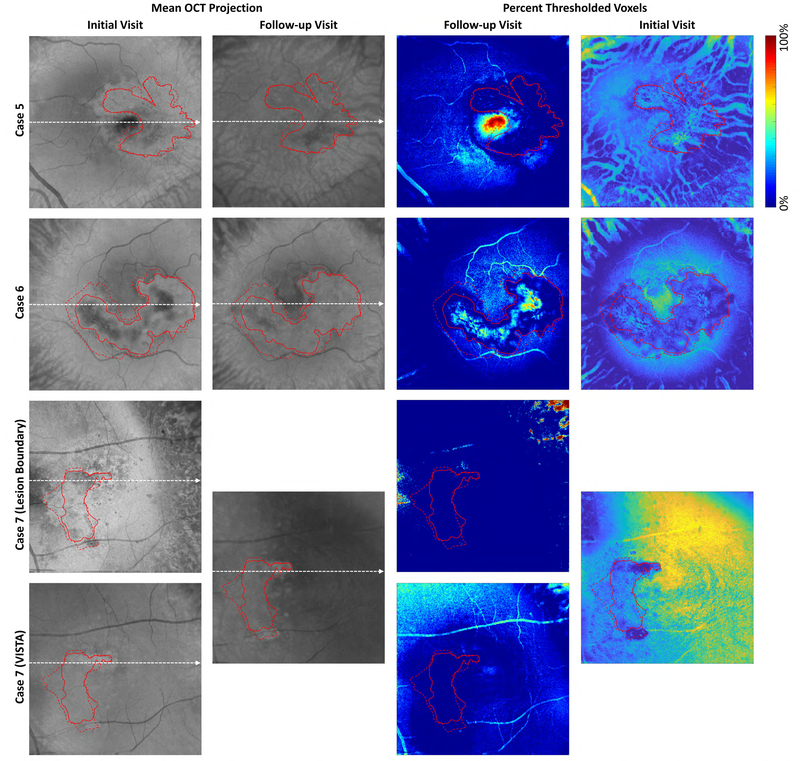

Figure 10A:

Analysis of signal strengths for Cases 1–4. Columns 1 and 2 show en face OCT images from the initial and follow-up visits, respectively. These en face images were formed by mean projection of the OCT volume through the boundaries shown in Figure 2. The dashed white lines indicate the positions from which the OCT and OCTA B-scans of Figure 2 were extracted. The images of Columns 3 and 4 show, for each en face position, the percentage of voxels between the projection boundaries that were below the threshold value (set as 6 standard deviations above the noise mean; see Table 6). Blue colors indicate stronger signals (a higher percentage of voxels were above the threshold), and red colors indicate weaker signals (a higher percentage of voxels were below the threshold). Note that for Case 1 we used two different projection ranges, one for each component of the lesion. For all cases, except Case 7, the same projection boundaries were used for both tracing the lesion margins and for VISTA computation; for the initial visit of Case 7, different projection bounds were used for margin tracing and VISTA computation. For all columns, solid red contours indicate the lesion boundaries on the initial visit, and dashed red contours indicate the lesion boundaries on the follow-up visit. Since the en face images were formed by projecting unsegmented volumes (Figure 2), the signals away from the lesion can correspond to projections through different layers, such as the choroid. Examining the boundaries of the lesions we can see that there is, in general, relatively high signal levels at the lesion margins, suggesting that our observed changes in lesion size are true, and not an artifact of low-signal related artifacts, such as thresholding.

Figure 11:

Scatter plots of lesion growth as a function of signal and threshold change between visits. For each plot, the percentage change in area (filled circle) and volume (empty circle) are plotted on the y-axis. The x-axis on the left panel corresponds to the percentage change in OCT signal strength (computed using the log-transformed OCT signal); the x-axis on the right panel corresponds to the percentage change in threshold value (set at 6 standard deviations above the noise mean). Percentage change was defined as 100% × (BA)/A, where A is the value on the initial visit, and B is the value on the follow-up visit. These values are summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

Signal Strength Analysis

| †OCT Signal Change [%] | †Threshold Level Change [%] | |

|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | −5.7 | −1.7 |

| Case 2 | −2.7 | 2.9 |

| Case 3 | 12.3 | 8.5 |

| Case 4 | 12.5 | 8.2 |

| Case 5 | −4.9 | 5.5 |

| Case 6 | 4.9 | 3.2 |

| Case 7 | −4.9 | 6.2 |

| *Absolute Mean (SD) | 6.8 (3.9) | 5.2 (2.7) |

Defined as 100% × (B-A)/A, where A is the value at the initial visit, and B is the value at follow-up

Where the mean is taken over the absolute values

In conclusion, using a VISTA OCTA algorithm, we have presented longitudinal observations of relative blood flow speeds in CNV treated with anti-VEGF intravitreal injections. A common finding in this study is that the main trunk and larger vessels appear to have relatively faster blood flow speeds compared with the lesions’ peripheral vasculature. The VISTA framework may prove useful for developing clinical end points, as well as for studying hemodynamics, disease pathogenesis, and treatment response.

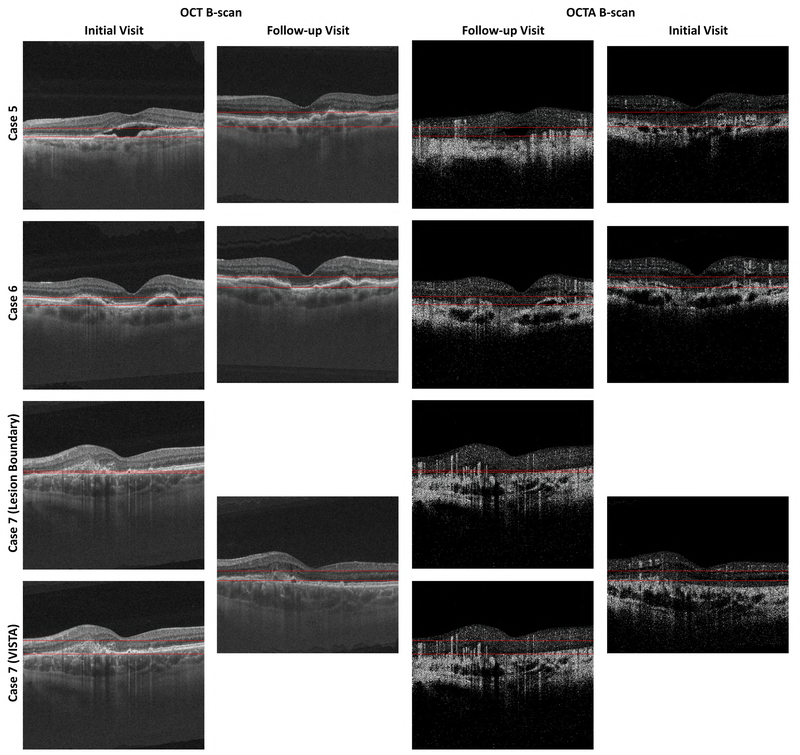

Figure 2B:

OCT and OCTA B-scans showing the projection boundaries for Cases 5–7. See caption of Figure 2A.

Figure 10B:

Analysis of signal strengths for Cases 5–7. See caption of Figure 10A.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Macular Vision Research Foundation, New York, New York; the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland (grant nos.: R01-EY011289-29A, R44-EY022864, and R01-CA075289-16); the Air Force Office of Scientific Research (grant nos.: AFOSR FA9550-15-1-0473 and FA9550-12-1-0499); Thorlabs matching funds to Praevium Research, Inc; Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc, New York, New York; the Massachusetts Lions Clubs, New Bedford, Massachusetts; and Samsung, Seoul, South Korea.

Human Subjects: Human subjects were included in this study. The study was approved by the Tufts Medical Center Institutional Review Board. Patients were imaged after informed, written consent was obtained. This research adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and complied with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- AMD

age-related macular degeneration

- CNV

choroidal neovascularization

- nAMD

neovascular age-related macular degeneration

- NEEC

New England Eye Center

- OCTA

optical coherence tomography angiography

- RPE

retinalpigment epithelium

- SS

swept-source

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- VISTA

variable interscan time analysis

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure(s):

The author(s) have made the following disclosure(s): E.M.M.: Intellectual property — Related to variable interscan time analysis technology S.B.P.: Intellectual property — Related to variable interscan time analysis technology

WJ.C.: Intellectual property — Related to variable interscan time analysis technology

P.J.R.: Consultant and financial support — Carl Zeiss Meditec

J.S.D.: Financial support — Carl Zeiss Meditec, Topcon, Optovue, Inc.

J.G.F.: Equity owner — Optovue, Inc; intellectual property — related to variable interscan time analysis technology; royalties — intellectual property owned by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and licensed to Carl Zeiss Meditec, Inc, and Optovue, Inc.

N.K.W.: Consultant — Optovue, Inc; financial support — Carl Zeiss Meditec, Topcon

References

- 1.Wong TY, Chakravarthy U, Klein R, et al. The natural history and prognosis of neovascular age-related macular degeneration: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:116–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bressler NM. Age-related macular degeneration is the leading cause of blindness. JAMA. 2004;291:1900–1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bird A, Bressler N, Bressler S, et al. An international classification and grading system for age-related maculopathy and age-related macular degeneration. Surv Ophthalmol. 1995;39:367–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dansingani KK, Freund KB. Optical coherence tomography angiography reveals mature, tangled vascular networks in eyes with neovascular age-related macular degeneration showing resistance to geographic atrophy. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2015;46:907–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuehlewein L, Dansingani KK, Talisa E, et al. Optical coherence tomography angiography of type 3 neovascularization secondary to age-related macular degeneration. Retina. 2015;35:2229–2235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abdelfattah NS, Zhang H, Boyer DS, et al. Drusen volume as a predictor of disease progression in patients with late age-related macular degeneration in the fellow eye: large OCT drusen volume predicts late AMD. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57:1839–1846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spaide RF. Rationale for combination therapies for choroidal neovascularization. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;141:149–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spaide RF. Optical coherence tomography angiography signs of vascular abnormalization with antiangiogenic therapy for choroidal neovascularization. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;160:6–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Group ES. Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapy for subfoveal choroidal neovascularization secondary to age-related macular degeneration: phase II study results. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:979–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferrara N, Damico L, Shams N, et al. Development of rani- bizumab, an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor antigen binding fragment, as therapy for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Retina. 2006;26:859–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown DM, Regillo CD. Anti-VEGF agents in the treatment of neovascular age-related macular degeneration: applying clinical trial results to the treatment of everyday patients. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;144:627–637.e622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heier JS, Brown DM, Chong V, et al. Intravitreal aflibercept (VEGF trap-eye) in wet age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:2537–2548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmidt-Erfurth U, Kaiser PK, Korobelnik JF, et al. Intravitreal aflibercept injection for neovascular age-related macular degeneration: ninety-six-week results of the VIEW studies. Ophthalmology. 2014;121:193–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahmadieh H, Taei R, Riazi-Esfahani M, et al. Intravitreal bevacizumab versus combined intravitreal bevacizumab and triamcinolone for neovascular age-related macular degeneration: six-month results of a randomized clinical trial. Retina. 2011;31:1819–1826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bonini Filho MA, de Carlo TE, Ferrara D, et al. Association of choroidal neovascularization and central serous chorioretinopathy with optical coherence tomography angiography. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015;133:899–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coscas GJ, Lupidi M, Coscas F, et al. Optical coherence tomography angiography versus traditional multimodal imaging in assessing the activity of exudative age-related macular degeneration: a new diagnostic challenge. Retina. 2015;35:2219–2228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Carlo TE, Bonini Filho MA, Chin AT, et al. Spectral-domain optical coherence tomography angiography of choroidal neovascularization. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:1228–1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moult E, Choi W, Waheed NK, et al. Ultrahigh-speed swept-source OCT angiography in exudative AMD. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2014;45:496–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coscas G, Lupidi M, Coscas F, et al. Optical coherence tomography angiography during follow-up: qualitative and quantitative analysis of mixed type I and II choroidal neovascularization after vascular endothelial growth factor trap therapy. Ophthalmic Res. 2015;54:57–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muakkassa NW, Chin AT, de Carlo T, et al. Characterizing the effect of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapy on treatment-naïve choroidal neovascularization using optical coherence tomography angiography. Retina. 2015;35:2252–2259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang D, Jia Y, Rispoli M, et al. Optical coherence tomography angiography of time course of choroidal neovascularization in response to anti-angiogenic treatment. Retina. 2015;35:2260–2264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuehlewein L, Sadda SR, Sarraf D. OCT angiography and sequential quantitative analysis of type 2 neovascularization after ranibizumab therapy. Eye. 2015;29:932–935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spaide RF, Fujimoto JG, Waheed NK. Image artifacts in optical coherence tomography angiography. Retina. 2015;35:2163–2180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choi W, Moult EM, Waheed NK, et al. Ultrahigh-speed, swept-source optical coherence tomography angiography in nonexudative age-related macular degeneration with geographic atrophy. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:2532–2544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ploner SB, Moult EM, Choi W, et al. Toward quantitative optical coherence tomography angiography: visualizing blood flow speeds in ocular pathology using variable interscan time analysis. Retina. 2016;36(Suppl 1):S118–S126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tokayer J, Jia Y, Dhalla AH, Huang D. Blood flow velocity quantification using split-spectrum amplitude-decorrelation angiography with optical coherence tomography. Biomed Optics Exp. 2013;4:1909–1924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Choi WJ, Qin W, Chen C-L, et al. Characterizing relationship between optical microangiography signals and capillary flow using microfluidic channels. Biomed Optics Exp. 2016;7:2709–2728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jaillon F, Makita S, Yasuno Y. Variable velocity range imaging of the choroid with dual-beam optical coherence angiography. Optics Exp. 2012;20:385–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Braaf B, Vermeer KA, Vienola KV, de Boer JF. Angiography of the retina and the choroid with phase-resolved OCT using interval-optimized backstitched B-scans. Optics Exp. 2012;20: 20516–20534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Choi W, Potsaid B, Jayaraman V, et al. Phase-sensitive swept-source optical coherence tomography imaging of the human retina with a vertical cavity surface-emitting laser light source. Opt Lett. 2013;38:338–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Unterhuber A, Povazay B, Hermann B, et al. In vivo retinal optical coherence tomography at 1040 nm—enhanced penetration into the choroid. Optics Exp. 2005;13:3252–3258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Novais EA, Adhi M, Moult EM, et al. Choroidal neovascularization analyzed on ultra-high speed swept source optical coherence tomography angiography compared to spectral domain optical coherence tomography angiography. Am J Ophthalmol. 2016;164:80–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Told R, Ginner L, Hecht A, et al. Comparative study between a spectral domain and a high-speed single-beam swept source OCTA system for identifying choroidal neovascularization in AMD. Sci Rep. 2016;6:38132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miller AR, Roisman L, Zhang Q, et al. Comparison between spectral-domain and swept-source optical coherence tomography angiographic imaging of choroidal neovascularization: imaging of CNV with SS-OCTA and SD-OCTA. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2017;58:1499–1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kraus MF, Potsaid B, Mayer MA, et al. Motion correction in optical coherence tomography volumes on a per A-scan basis using orthogonal scan patterns. Biomed Optics Exp. 2012;3:1182–1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kraus MF, Liu JJ, Schottenhamml J, et al. Quantitative 3D-OCT motion correction with tilt and illumination correction, robust similarity measure and regularization. Biomed Optics Exp. 2014;5:2591–2613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fedorov A, Beichel R, Kalpathy-Cramer J, et al. 3D Slicer as an image computing platform for the quantitative imaging network. Magn Resonance Imaging. 2012;30:1323–1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Husvogt L, Moult EM, Lee B, et al. SlicerOCT: a 3-D visualization platform for orthoplane viewing of OCT (A) datasets. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57:5974–5974.27820953 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kuehlewein L, Bansal M, Lenis TL, et al. Optical coherence tomography angiography of type 1 neovascularization in age-related macular degeneration. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;160: 739–748.e732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Adamis A, Shima D, Yeo K-T, et al. Synthesis and secretion of vascular permeability factor/vascular endothelial growth factor by human retinal pigment epithelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;193:631–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shima D, Adamis A, Ferrara N, et al. Hypoxic induction of endothelial cell growth factors in retinal cells: identification and characterization of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) as the mitogen. Mol Med. 1995;1:182–193. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carmeliet P Mechanisms of angiogenesis and arteriogenesis. Nature Med. 2000;6:389–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Penn J,Madan A, Caldwell RB, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor in eye disease. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2008;27:331–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sarks J, Sarks S, Killingsworth M. Morphology of early choroidal neovascularisation in age-related macular degeneration: correlation with activity. Eye (Lond). 1997;11:515–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heil M, Eitenmuller I, Schmitz-Rixen T, Schaper W. Arte-riogenesis versus angiogenesis: similarities and differences. J Cell Mol Med. 2006;10:45–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cole ED, Ferrara D, Novais EA, et al. Clinical trial endpoints for optical coherence tomography angiography in neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Retina. 2016;36:S83–S92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spaide RF. Volume-rendered optical coherence tomography of diabetic retinopathy pilot study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;160: 1200–1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Spaide RF, Suzuki M, Yannuzzi LA, et al. Volume-rendered angiographic and structural optical coherence tomography angiography of macular telangiectasia type 2. Retina. 2017;37: 424–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Spaide RF. Volume-rendered optical coherence tomography of retinal vein occlusion pilot study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2016;165: 133–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Spaide RF. Volume-rendered angiographic and structural optical coherence tomography. Retina. 2015;35:2181–2187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Spaide RF, Klancnik JM, Cooney MJ, et al. Volume-rendering optical coherence tomography angiography of macular telangiectasia type 2. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:2261–2269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang M, Hwang TS, Campbell JP, et al. Projection-resolved optical coherence tomographic angiography. Biomed Optics Exp. 2016;7:816–828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang A, Zhang Q, Wang RK. Minimizing projection artifacts for accurate presentation of choroidal neovascularization in OCT micro-angiography. Biomed Optics Exp. 2015;6:4130–4143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gao SS, Liu L, Bailey ST, et al. Quantification of choroidal neovascularization vessel length using optical coherence tomography angiography. J Biomed Opt. 2016;21:076010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu L, Gao SS, Bailey ST, et al. Automated choroidal neovascularization detection algorithm for optical coherence tomography angiography. Biomed OpticsExp. 2015;6:3564–3576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]