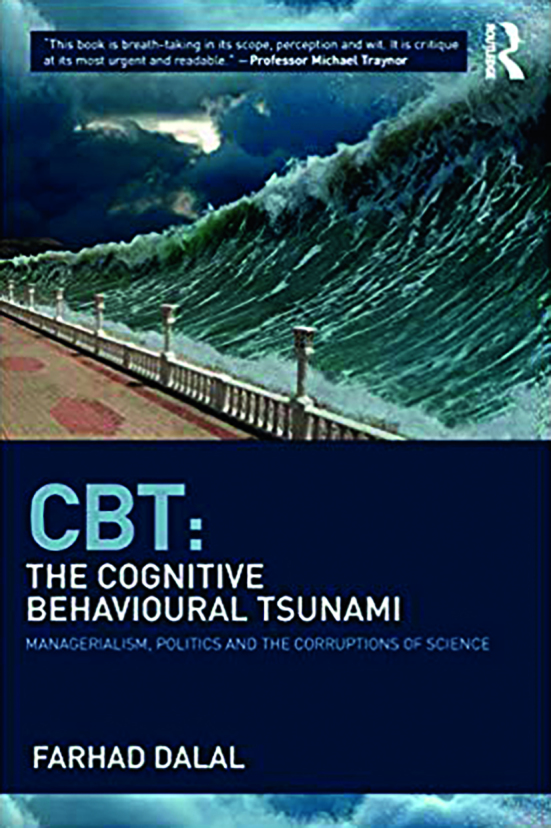

The basic theme of this stimulating and thought-provoking book is a critique of CBT, in particular the way it has become the default option (when available) for anyone in England presenting to their GP with any form of mental distress. However, the analysis is much more wide-ranging and I found the overview in the first few chapters fascinating. This covers a range of disciplines — including philosophy, psychology, psychiatry, psychoanalysis, economics, and current health service management policies — nothing is spared. Interesting examples include: reflections on how the psychiatric diagnostic manual the DSM came about, initially via chaotic committee meetings; the development of CBT as a psychological therapy with outcomes which could be measured numerically and therefore deemed ‘scientific’; and the move to market economics in health, with economists like Milton Friedman asserting that a model maximising profits was most efficient, not only for business but also applicable to social institutions.

The author threads these arguments together to give a coherent argument of how CBT came to ascendancy because of an emphasis on a hyper-rational and cognitivist perspective of human behaviour in the context of a highly managed healthcare environment. He is particularly critical of arguments given by Richard Layard (an eminent professor of economics) and David M Clark (emeritus professor and leading CBT proponent) when suggesting that increased provision of CBT would lead to a happier population with reduced unemployment rates. He sees this as simplistic at best, and potentially part of a neoliberal agenda to control the workforce and not look out for the vulnerable and needy, given that those with more complex mental health problems may well not respond to CBT.

Later chapters focus on a more personal critique of how CBT was developed and how, in the author’s view, it does not address the underlying reasons why people may become anxious, depressed, or distressed, and is merely addressing the presenting symptoms. He suggests the questionnaires used to assess patients’ progress are superficial and open to being ‘gamed’ by stressed and stretched Increasing Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) practitioners tasked with reaching treatment targets, as well as questioning the evidence from many of the randomised controlled trials.

The author concedes that CBT can be helpful in particular cases, but questions its widespread implementation to the exclusion of other therapies.

I think this book is definitely worth reading by anyone interested in how common mental health problems are currently viewed and treated in the UK; my main reservation is that the author does not offer any suggestions for alternative approaches which might benefit the many people presenting to their GP with distress, be it specific or more existential in nature: maybe that will come in another book.