Abstract

Including children in protective custody (e.g., foster care) in legal decisions positively impacts their perceptions of the legal system, with giving youth a voice being particularly important. Studies have primarily focused on including young people in legal processes; however, for adolescents in protective custody, decisions about living arrangements, education, and long-term planning are made outside the courtroom, with ramifications for young people and their perceptions of both legal and child protection systems. This study looks at such decision making using existing data from 151 adolescents who were ages 16–20 and had been in child welfare protective custody for at least 12 months. During in-person interviews we assessed their desired amount of involvement in a recent decision and their perceptions of their actual involvement. Youth named other individuals involved in decision-making. Data were coded and analysed to identify discrepancies in young people’s perceptions of desired and actual levels of involvement. Results indicate that while the majority of adolescents (96%) are participating in decision-making, they generally desire more involvement in decisions made (64%). Only 7% of youth reported that their level of personal involvement and the involvement of others matched what they desired. The most common individuals identified in a decision made were child protection workers, legal professionals, and caregivers or family members. These findings enhance the existing literature by highlighting the unique issues related to giving young people in protective custody a voice, and provide an empirical foundation for guiding policies around who to involve in every-day decisions made for young people preparing for emancipation from protective custody.

Keywords: child welfare, child protection, emancipation, adolescent, decision-making

Approximately 430,000 children in the United States (US) are in the custody of child protective services (CPS; US Department of Health and Human Services, 2016). In the US, children in CPS custody are temporarily removed from the homes of their families of origin and placed with licensed foster caregivers (i.e., foster care), unlicensed relatives or family friends who agree to care for the child (i.e., kinship care), or in group homes, residential treatment centres, or independent living programs (Barth et al., 2008; Berrick, 1998). The primary reasons for removal from families of origin are neglect (i.e., failing to provide for basic needs such as food, clothing, or supervision) and abuse (i.e., intentional physical, emotional/psychological, or sexual harm toward the child; Conn et al., 2013).

Once children are in CPS custody, services are typically provided to the child and family of origin with the goal of remediating the familial challenges that contributed to the abuse or neglect so that the child can be reunified with his or her family of origin (Fisher, Chamberlain, & Leve, 2009). When remediation does not occur in a timely manner (generally within 24 months) efforts to reunify children with their parents generally halt and the parental rights of the family of origin can be terminated, making the child available for adoption (Allen & Bissell, 2004). The combination of families of origin not successfully reunifying within the necessary timeframe and adolescents not being available or sought out by the majority of adoptive families contributes to more than 20,000 adolescents emancipating (i.e., aging out) of CPS custody at or near their 18th birthdays (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2016). Extensive research has demonstrated that these young people experience worse health and psychosocial outcomes than their peers, including increased rates of re-victimization, homelessness, criminal offending, and incarceration (Courtney et al., 2011).

Research has previously demonstrated that giving individuals a voice and involving them in legal decisions promotes their perceptions of fairness in the legal system (Hinds, 2007; Penner, Viljoen, Douglas, & Roesch, 2014). This is important, because believing the legal system is fair is associated with increased intent to obey the law (Cohn, Trinkner, Rebellon, Van Gundy, & Cole, 2012; Trinkner & Cohn, 2014) and with decreased recidivism among those who have previously broken the law (Hinds, 2007; Mulvey et al., 2004; Penner et al., 2014). Said differently, when individuals involved with the legal system are given a voice, it enhances their belief that the legal system is fair and improves their likelihood of obeying laws in the future. While this literature has primarily focused on adults, a subset of studies specifically targeting children and adolescents has replicated these findings (Block, Oran, Oran, Baumrind, & Goodman, 2010; Cashmore & Bussey, 1994; Quas, Wallin, Horwitz, Davis, & Lyon, 2009; Weisz, Wingrove, Beal, & Faith-Slaker, 2011). Several of these studies, including studies involving children in CPS custody, have illustrated the critical role of voice in promoting youths’ beliefs that the legal and child protection systems are fair regardless of the outcome decided by those systems (i.e., procedural justice), and that those systems and the professionals serving in them are trustworthy and should be obeyed (i.e., legitimacy; Cashmore, 2002; Weisz et al., 2011).

Considering the role of voice among adolescents in CPS custody is important for several reasons. First, this population has the greatest duration of contact with CPS over their childhoods, leading to non-parental adults making decisions that impact children long-term. Adolescents are significantly more likely to spend five or more years in CPS custody compared to their younger counterparts (Chapin Hall, 2017). Second, adolescents have previously reported a lack of involvement in the decisions made about their lives. Multiple studies have illustrated how little opportunity adolescents in CPS custody have to share their perspectives about their cases (Cashmore, 2002; Weisz et al., 2011). One important caveat to the existing literatures on procedural justice for youth in CPS custody is that studies have almost exclusively focused on decisions made in formal legal contexts. This primarily occurs in the presence of a judge or magistrate, who has the final authority to make determinations about high-impact case outcomes including reunification and emancipation from CPS custody. In these formal settings it is easier to objectively determine if the youth had the opportunity to share his or her voice: the youth needs to be present, to have the opportunity to speak before the court, and to have legal representation advocating and consulting on his or her behalf. However, the majority of decisions made about the lives of adolescents in CPS custody are not made in a courtroom. Rather, decisions about placement changes and residences, school, vocational training, extracurricular activities, and health are more often made during monthly team meetings with CPS caseworkers, or within the context of another activity (e.g., during meetings with medical or educational specialists). US law states that youth in CPS custody should have a voice and be represented in both formal and informal decision-making contexts (American Bar Association, 2017); however, studies to date have focused primarily on youth involvement in legal decisions (Cashmore, 2002; Cashmore & Bussey, 1994; Quas et al., 2009; Weisz et al., 2011). Adolescent voice and decision-making in informal contexts have been a focus of research and policy changes in child welfare internationally, and particularly in Europe (e.g., Hallett & Prout, 2003; Pösö, Skivenes, & Hestbæk, 2014), with findings indicating that young people involved in social welfare systems often use their voice as part of help-seeking behaviour, while simultaneously perceiving the inclusion of adult voice into their social problems as making the situation worse (Hallett, Murray, & Punch, 2003). In contrast, the role of adolescent voice in decision-making in informal settings in the US has not been well-studied. For example, in her review of studies examining youth’s perspectives around placement changes for children in protective custody, Unrau (2007) identified nine papers that included the foster child as a data source. Of those, three peer-reviewed studies based in the US involved interviews with foster children (Chapman, Wall, & Barth, 2004; Herrenkohl, Herrenkohl, & Egolf, 2003; Johnson, Yoken, & Voss, 1995), but only one (Johnson, Yoken, & Voss, 1995) solicited adolescents’ perspectives of their involvement in decision-making. In that case, children reported little to no involvement in decisions to change placements.

While adolescent voice and shared decision-making have not been a focus in child welfare, research from other settings and contexts provide some insight into the mechanisms at play. For example, research within healthcare has examined shared decision-making among healthcare providers, parents, and adolescents, both within the context of a healthcare encounter (i.e., formal setting; Brinkman et al., 2012; Knopf, Hornung, Slap, DeVellis, & Britto, 2008; Lipstein, Muething, Dodds, & Britto, 2013) and outside the clinic (i.e., informal settings; Miller & Drotar, 2003). That literature generally suggests that adolescents are highly variable in their desired level of autonomy and how ready they perceive themselves to be responsible for decision-making (Coyne & Harder, 2011). The balance between wanting to protect children and simultaneously support their independence can be challenging, particularly when stakes are high. In this context, studies have demonstrated discrepancies between parents and adolescents in their perceptions of the adolescents’ autonomy in medical decisions (Miller & Drotar, 2003), preferences for shared decision making (Knopf et al., 2008), and influences on treatment decisions (Lipstein, Dodds, Lovell, Denson, & Britto, 2016). Similar incongruence has been found between adolescent patients and their health care providers (Britto et al., 2007; Cervesi, Battistutta, Martelossi, Ronfani, & Ventura, 2013).

Outside of healthcare, research in fields such as psychology and marketing have examined parent-child interactions and decision-making in less formal settings, including decisions around product purchases (e.g., Palan & Wilkes, 1997), health behaviours (e.g., Wong, Zimmerman, & Parker, 2010), and interpersonal interactions (e.g., Zimmer-Gembeck, Madsen, & Hanisch, 2011). Across these domains, researchers have consistently found that when adults have supportive, warm, and nurturing relationships with adolescents and are less controlling, adolescents provide more voice in decision-making. This continuum is well-represented by Wong et al’s typology of youth participation and empowerment (TYPE) pyramid (2010). The pyramid is made up of five typologies: vessel, where the adult has total control and youth voice is not represented; symbolic, where youth have a voice but adults remain in control, pluralistic, where youth and adults share control; independent, where youth have voice and adults have limited control, and autonomous, where youth have voice and total control. Across these literatures, emphasis on a pluralistic approach, where youth have a voice and share control with adults in decision-making, is commonly desired for optimal adolescent wellbeing.

The current study was developed to describe adolescents’ perceptions of their voice in a recent “day to day” decision made about their lives and their desired level of voice in decision-making. Integrating multiple approaches from disciplines outside of child welfare, we sought to describe the level of adolescents’ voice in shared decision-making and desired level of voice. Further, we examined the extent to which other adults are involved in decisions made with adolescents, from the perspectives of youth preparing for emancipation from child welfare. Drawing from the framework of the TYPE pyramid, inconsistencies in level of voice and desired level of voice were classified as a proxy for amount of influence and control youth had, such that adolescent voice would be considered optimal when both their involvement and the involvement of others were congruent with youth’s desired levels of voice.

Methods

Participants

This analysis is based on a longitudinal study of 151 young people ages 16–22 (Mean age = 17.63 years, SD = 1.40) who were in the legal custody of child welfare in a single urban county in Ohio. Young people were eligible to participate if they were between the ages of 16 and 22 years old, had been in protective custody for 12 months or longer, spoke English, were able to provide consent (legally able to give permission to participate; in the US context, consent applies to youth ages 18 and older) or assent (legally able to express agreement to participate when consent is already provided; in the US context, assent applies to youth ages 16–17) to participate, and who lived within a one-hour driving distance of where the study took place.

Procedures

CPS provided the research team with consent for 436 potentially eligible youth in their custody to be enrolled in the research, which was approved by the institutional review board. Researchers screened the medical records of these youth to eliminate those who did not meet inclusion criteria. The CPS caseworkers and court-appointed guardians ad litem (GALs) or special advocates (CASAs) of the youth were notified of the study via email and given an opportunity to opt-out of youth participating. If the caseworkers or GALs/CASAs did not opt out, youth were contacted via a mailed letter notifying them of their eligibility to participate in the study, and given an opportunity to opt-out of contact with the researchers. The majority of youth (n = 364) were considered to be potentially eligible after review of medical charts and contact with caseworkers and GALs. Over half (n = 204) of the youth were contacted and 154 provided initial verbal assent to participate. Researchers met participants in their homes or at other locations within the community such as libraries or restaurants. Eligible participants (n = 151) provided documented informed consent if aged 18 years or older or assent if aged 17 years or younger and completed study measures at those visits. Three participants who provided initial verbal assent were lost to enrollment due to changes in placement (n = 2) or incarceration (n = 1).

Measures

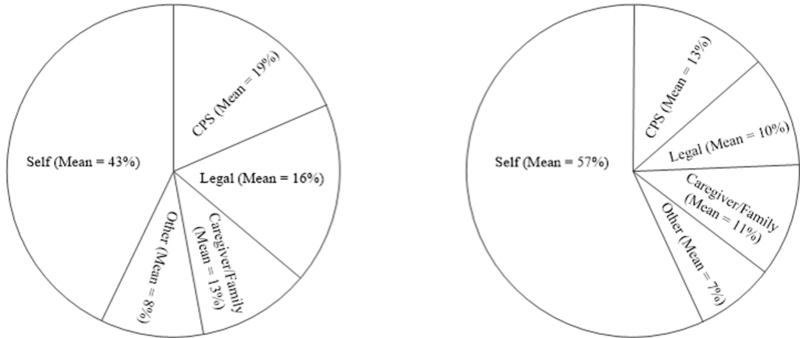

During in-person study visits, youth were asked to describe their perception of their own voice and the voice of others in a recent decision made about their case. This involved using pie charts and having the participant divide the circle based on their perceived voice and the voice of other parties (e.g. CPS caseworkers, caregivers, legal personnel, etc.) in the decision (see Figure 1). Participants were then asked to complete the same task, but instead of using perceived levels of voice, to use their desired levels of voice for each party making the decision. Youth were told they could exclude people from the decision entirely, or add new people that they wished to be involved. The percent of the circle between lines drawn for each party involved in the decision making was measured, and discrepancies in perceived vs. desired involvement were calculated for each party making the decision. Who youth named in the decision was also coded and categorized as self, legal personnel (e.g., Judge, lawyer, GAL, CASA), child welfare (e.g., caseworker, independent living worker, wraparound service provider), caregivers and relatives (e.g., foster parent, biological parent, grandparent), and others (e.g., peers, friends, significant others, employers, clinicians). Due to the lack of detail provided by some participants, we were not able to distinguish among types of caregivers (i.e., foster caregivers, families of origin) for many youth.

Figure 1.

Pie chart shared decision-making activity completed by participants, with average perceived (left) and desired (right) levels of voice reported.

Classification of voice was adapted from TYPE pyramid typologies as follows: Youth who reported no voice in decision-making were classified under “vessel,” regardless of desired level of voice. Youth who reported some voice (i.e., more than 0% and less than 100%), but desired an increased level of voice (i.e., voice was not as high as desired) were classified under “symbolic.” Youth who reported some voice and desired no change were classified as “pluralistic.” Youth who reported some voice and desired a decrease in level of voice (i.e., voice higher than desired) were classified as “independent.” Youth who reported that their voice was the only voice in the decision, regardless of desired level of involvement, were classified as “autonomous.”

Adolescent-reported covariates included gender, race and ethnicity, age at the time of data collection, and a sum of the number of maltreatment experiences (e.g., sexual abuse, physical abuse, excessive discipline) ranging from 0 to 9 adapted from the Childhood Trust Events Survey (Pearl, 2000). CPS provided each participant’s age of entry into protective custody, lifetime number of custody episodes, lifetime number of placement changes, and length of the current placement episode, which were also included as covariates in regression models.

Statistical Approach

Univariate and bivariate descriptive statistics were examined for all study measures. To understand relations among demographic characteristics with adolescent involvement and desired involvement in decision-making, multiple linear regression was conducted predicting adolescents’ level of voice and desired level of voice, using demographic characteristics. Similar models were estimated examining the voice of caregivers and relatives, CPS, legal, and other individuals or agencies in the decision. All analyses were conducted using STATA 14.0.

Results

Univariate statistics for all study items are provided in Table 1. Participants were predominantly African-American (70%) or White (23%), with slightly more females participating than males (54%).

Table 1.

Univariate statistics for all study variables

| Study Variable | M or % | SD | N |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived self voice | 0.43 | 0.27 | 150 |

| Desired self voice | 0.57 | 0.30 | 151 |

| Self discrepancy | 0.15 | 0.33 | 151 |

| Perceived CPS voice | 0.19 | 0.21 | 151 |

| Desired CPS voice | 0.13 | 0.18 | 151 |

| CPS discrepancy | −0.07 | 0.16 | 151 |

| Perceived legal voice | 0.16 | 0.23 | 151 |

| Desired legal voice | 0.10 | 0.18 | 151 |

| Legal discrepancy | −0.05 | 0.18 | 151 |

| Perceived caregiver/family voice | 0.13 | 0.20 | 151 |

| Desired caregiver/family voice | 0.11 | 0.18 | 151 |

| Caregiver/family discrepancy | −0.01 | 0.17 | 151 |

| Perceived other voice | 0.08 | 0.18 | 151 |

| Desired other voice | 0.07 | 0.18 | 151 |

| Other discrepancy | −0.01 | 0.16 | 151 |

| Female | 54% | -- | 151 |

| Racial/Ethnic Minority | 91% | -- | 151 |

| Age | 17.63 | 1.40 | 151 |

| Age of CPS custody | 14.30 | 2.94 | 151 |

| Length of time in CPS custody (months) | 47.76 | 38.43 | 151 |

| Lifetime custody episodes | One: 69% Two: 20% Three or more: 11% |

-- | 148 |

| Number of placements | 6.11 | 4.62 | 148 |

| Maltreatment history | 4.20 | 2.44 | 150 |

Adolescents’ Participation in Decision-Making

Adolescents reported that their voice accounted for an average of slightly less than half (43%) of the decision made, while other individuals involved in decision-making contributed for an average of slightly more than half (57%) of decisions made. A minority of youth (n = 6; 4%) reported no voice; 97 youth (64%) reported that their voice contributed to less than half of the decision-making, and 48 youth (32%) reported that their voice contributed to more than half of the decision-making. A subset of these youth (n = 11; 7%) reported that they were the only voice in the decision.

For the majority of decisions (57%), adolescents reported that a CPS worker was involved and accounted for an average of approximately one-fifth (19%) of the voice in decisions made. A slightly fewer number of decisions (43%) involved a representative of the legal system, which accounted for a slightly smaller proportion (16%) of the voice in decisions made when compared to CPS workers. Caregivers and parents were also routinely involved in decisions (37% of decisions) with a mean voice in the decision made that was slightly less than that of CPS workers or legal professionals (13%). Finally, others (e.g., friends, peers, clinicians, employers), were less routinely included in decision-making (21%). Others accounted for a very small proportion (8%) of the voice in decisions made.

Adolescents’ Desired Participation in Decision-Making

The majority of adolescents desired an increase in their voice, with a mean desired voice contribution level of around half (57%) of the decision; 83 youth (55%) desired their voice to contribute to less than half of the decision made. The mean difference in perceived vs. desired contribution averages was relatively small (15%), with 31 youth (20%) wanting a reduction in voice, 21 youth (14%) wanting the same amount of voice, and 99 youth (66%) wanting an increase in voice.

Across the board, adolescents expressed a desire for decreased involvement of other individuals in decision-making. Adolescents desired a slight decrease in CPS and legal system involvement (average of 6% decrease for each stakeholder). The desired contribution of caregivers, parents, and others was also negligibly lower than what adolescents reported for perceived involvement, with a mean desired contribution level decrease of 2% lower for caregivers and parents, and a desired decrease of 1% for others (i.e., friends, peers, clinicians, and employers). To summarize, second to themselves, young people desired CPS to be the second most involved voice in decision-making, closely followed by legal representatives and caregivers, and then the voice of other stakeholders.

Typologies of Decision-Making

Adolescents were classified into one of five typologies of adolescent decision-making from the TYPE pyramid (Wong et al., 2010). For 6 adolescents (4%), perceived adult control was high and youth had no voice. This reflected the vessel typology. Ninety-six adolescents (64%) reported having some voice, but not as much voice as desired. This reflected the symbolic typology. Ten adolescents (7%) reported having some voice and did not desire a change in their level of voice. This reflected the pluralistic typology. Twenty-eight adolescents (19%) desired less voice, but were not completely in control of decision-making. This reflected the independent typology. Finally, 11 adolescents (7%) reported that they were the only voice involved in decision-making, reflecting an autonomous typology. Bivariate analyses indicated that autonomous youth were significantly older (Mdifference = 1.38 years, t (149) = −3.25, p < .01) and were in protective custody for longer (Mdifference = 46.32 months, t (149) = −4.04, p < .01); no other significant differences in demographic or child welfare characteristics were detected among these groups.

Associations with Actual and Desired Involvement in Decision-making

Results from linear regression models predicting levels of perceived and desired involvement as reported by adolescents are provided in Table 2. No demographic characteristics or CPS experiences were associated with perceived voice, desired voice, or discrepancies in voice for foster youth. Likewise, no variables were associated with caregiver and family involvement in the decision, CPS involvement, or the involvement of other people. In contrast, a history of more child maltreatment experiences among foster youth was significantly associated with a higher degree of legal professional involvement in decision-making, as well as a desire for a higher degree of legal professional involvement. No other factors were significantly associated with legal professional involvement.

Table 2.

Regression models predicting actual desired, discrepancies in levels of voice.

| Actual | Desired | Discrepancies | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE |

| Gender | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.06 |

| Racial/Ethnic Minority | 0.14 | 0.08 | −0.02 | 0.09 | −0.15 | 0.10 |

| Age | 0.04 | 0.07 | −0.10 | 0.09 | −0.15 | 0.09 |

| Age of CPS custody | −0.02 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.09 |

| Length of time in CPS custody | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Lifetime custody episodes | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.04 |

| Number of placements | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Maltreatment history | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| F (8, 137) | 2.06** | -- | 0.72 | -- | 1.44 | -- |

| R2 | 0.11 | -- | 0.04 | -- | 0.08 | -- |

| CPS | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE |

| Gender | 0.02 | 0.04 | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.04 | 0.03 |

| Racial/Ethnic Minority | −0.12 | 0.06 | −0.07 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Age | −0.07 | 0.06 | −0.03 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.05 |

| Age of CPS custody | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.05 | −0.04 | 0.05 |

| Length of time in CPS custody | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Lifetime custody episodes | −0.03 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| Number of placements | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.00 |

| Maltreatment history | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| F (8, 137) | 1.59 | -- | 0.94 | -- | 0.73 | -- |

| R2 | 0.03 | -- | 0.05 | -- | 0.04 | -- |

| Legal | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE |

| Gender | −0.03 | 0.04 | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| Racial/Ethnic Minority | −0.01 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.05 |

| Age | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.05 |

| Age of CPS custody | −0.03 | 0.07 | −0.05 | 0.05 | −0.02 | 0.05 |

| Length of time in CPS custody | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Lifetime custody episodes | −0.03 | 0.03 | −0.03 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.02 |

| Number of placements | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.00 |

| Maltreatment history | 0.02** | 0.01 | 0.02** | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| F (8, 137) | 1.87* | -- | 2.70** | -- | 0.73 | -- |

| R2 | 0.06 | -- | 0.14 | -- | 0.04 | -- |

| Caregiver/Family | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE |

| Gender | −0.02 | 0.04 | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.03 |

| Racial/Ethnic Minority | −0.06 | 0.06 | −0.01 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Age | −0.03 | 0.06 | −0.02 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.05 |

| Age of CPS custody | −0.01 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.05 |

| Length of time in CPS custody | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Lifetime custody episodes | 0.00 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.02 |

| Number of placements | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| Maltreatment history | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| F (8, 137) | 1.36 | -- | 0.74 | -- | 0.73 | -- |

| R2 | 0.02 | -- | 0.04 | -- | 0.04 | -- |

| Other | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE |

| Gender | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.03 |

| Racial/Ethnic Minority | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.05 |

| Age | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.04 |

| Age of CPS custody | −0.01 | 0.05 | −0.03 | 0.05 | −0.02 | 0.05 |

| Length of time in CPS custody | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Lifetime custody episodes | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.02 |

| Number of placements | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Maltreatment history | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| F (8, 137) | 1.28 | -- | 0.54 | -- | 0.79 | -- |

| R2 | 0.07 | -- | 0.03 | -- | 0.04 | -- |

p < .01

p < .05

Discussion

This study sought to examine the associations among adolescents’ perceptions of voice in informal decision-making and their desired level of voice. Results indicated that adolescents desired an increase in voice, consistent with previous reports that adolescents make limited contributions to decisions about their cases, including placement, visitation, and permanency (Chapman et al., 2004; Scannapieco, Connell-Carrick, & Painter, 2007). Of note, our findings do suggest that the majority of adolescents are involved, to some degree, in decision-making in informal contexts, which is distinct from the literature examining voice and decision-making in formal legal contexts (e.g., Quas et al., 2009; Weisz et al., 2011). While more research is needed, this may indicate that context is important when examining youths’ perceptions of involvement in decisions.

Surprisingly, while adolescents desired an increase in their voice, the mean increase desired was fairly small (i.e., from 43% to 57%), indicating that for most adolescents, being part of a team making decisions was desirable. In other words, adolescents desired an increase in voice, but did not desire to be the only voice in decision-making about their lives. This is consistent with the notion of plurality (Wong et al., 2010) and is developmentally appropriate (Foxman, Tansuhaj, & Ekstrom, 1989; Kümpel Nørgaard, Bruns, Haudrup Christensen, & Romero Mikkelsen, 2007; Smetana, Campione‐Barr, & Daddis, 2004; Wray‐Lake, Crouter, & McHale, 2010). That adolescents want to have some voice, but for the most part did not want to be alone in decision-making, is consistent with previous study findings that adolescents in foster care desire to have significant relationships with adults who can assist them with transitions to adulthood (Day, Riebschleger, Dworsky, Damashek, & Fogarty, 2012). Current US policy emphasizes independence for adolescents in custody in order to prepare them for emancipation, which may contribute to adolescents in child welfare becoming autonomous in decision-making about their lives at younger ages than their peers (Berzin, Singer, & Hokanson, 2014; Day et al., 2012). Of note, complete autonomy in decision-making was not the desire expressed by the majority of participants in this study. However, some studies have found qualitative evidence that at least some young people in CPS custody desire autonomy and do not want input from other adults in their lives (Ahrens et al., 2011; Scannapieco et al., 2007). In the current study, this perspective was held by 7% of youth, and these young people were generally older and in protective custody for longer than their counterparts who desired more plurality in decision-making. However, in general demographic and child welfare characteristics were not predictive of either voice or desired level of voice for youth or for others involved in decisions. This suggests that the factors impacting a young person’s desire for plurality or autonomy may be dependent on mechanisms other than age or child welfare experience. Additional research examining the nuances driving these dynamics is needed.

The majority of adolescents in this study reported CPS worker involvement in decisions, consistent with CPS practices in the US. While adolescents desired a decrease in CPS involvement in decision-making, on average, the decrease did not eliminate CPS involvement entirely. Again, this is somewhat distinct from the existing narrative of adolescents emancipating from CPS custody in the US, where adolescents have reported wanting to be free of CPS involvement (Strolin-Goltzman, Kollar, & Trinkle, 2010). One source of the discrepancy between these findings and the previous literature could be the measurement approach, which may be more nuanced with respect to involvement. These results should be further probed and replicated to better understand youth desires for CPS worker involvement and the implications of involvement on outcomes, as worker involvement was unrelated to any of the outcomes examined here. Additionally, the quality and length of the relationships between CPS workers and adolescents was not assessed – previous research has demonstrated that adolescents have less trust and reliance on CPS workers when they change frequently (Strolin-Goltzman et al., 2010), an important avenue for future research.

Many adolescents also reported legal professional involvement in their case, and a desire for legal professionals to reduce their level of involvement in decision-making. Similar to CPS workers, adolescents desired to decrease but not to eliminate legal professional contributions. Of note, adolescents who reported more history of abusive experiences also reported greater legal professional involvement in decision-making and a desire for increased involvement; thus, it may be that legal involvement is perceived differently by adolescents with a complex abuse history. For example, children with more complex maltreatment histories often also experience repeated entry into protective custody, longer lengths of time in custody, and more placement changes, all of which would increase exposure to the legal community (Kisiel, Fehrenbach, Small, & Lyons, 2009). Youth with these experiences may perceive legal professionals to be more helpful. Alternatively, these findings could reflect the desires of young people to have stronger relationships with non-parental adults (Ahrens et al., 2011; Nesmith & Christophersen, 2014); however, this does not explain why young people would seek legal professionals and not other professionals’ involvement. Qualitative research that explores this dynamic will be essential to explain these findings.

The bulk of research on significant adult relationships for adolescents emancipating from CPS custody indicates that having appropriate adult contact and support, which includes having trusted adults involved in decision-making, improves adolescent outcomes (Greeson, Thompson, & Arnett, 2014). Ideally, these decision-making interactions would support adolescents and trusted adults in a way that both parties have influence and voice, but that adolescents would have the opportunity to express how much control they wanted, consistent with a plurality typology of decision-making (Wong et al., 2010). These study findings indicated that only 7% of adolescents fell into this category; while adolescents are often included in decisions (96%), the majority of adolescents (63%) are given less voice than they desire. This distinction is important, specifically as it relates to adolescents emancipating from CPS custody. Encouraging professionals working with adolescents to include the voice of young people in decision-making (e.g., Barford & Wattam, 1991), often presented as being “youth-centred” or “youth-driven” in models of decision-making and service delivery (Crowe, 2007), likely is most beneficial when professionals support adolescents in deciding who participates in the decision, rather than having adolescents make decision more autonomously (Powers et al., 2012). Additional studies are essential; soliciting adolescent perspectives about decision-making in a way similar to the pie chart method used here would be beneficial for communicating with team-members about who adolescents want involved in the decisions made about their lives and could guide discussions about what reduced contributions would look like in a way that makes “youth driven” more concrete and measureable. Of note, this process may need to be adhered to across multiple decisions made, as youth may desire different levels of involvement in different decision contexts. This study lays the foundation for future research that addresses how to implement this approach in practice.

These findings should be interpreted within the context of several limitations. First, study data about adolescent voice in decision-making were collected at a single point in time, and adolescents were not directed to discuss one particular decision. While the findings here are based on adolescents’ reports of a variety of different decisions made about their topics, which makes the application of these findings generalizable to multiple decision contexts, it limits conclusions about the individuals included in the decision or the contribution of any one individual within a particular decision-making context. For example, if a young person was reflecting on a decision about a permanency arrangement, involvement of the CPS worker and legal personnel would be appropriate and necessary; however, this would not necessarily be required for a decision about employment. No data about the context of the specific decision an adolescent was reporting on were collected and therefore this information is not available to explore in this paper. Second, this paper relied solely on quantitative methods and reports of adolescents in custody. Qualitative research exploring these dynamics and probing the findings in this study are essential to expand this work. Third, the sample was limited to adolescents preparing for emancipation from CPS custody, and research on a broader sample of youth in CPS custody may reveal different results. Finally, the reports of adolescent voice in decision-making are subjective from the young person’s point of view. Studies examining the perspectives of young people and objective raters may provide insight into the dynamics of supporting adolescents’ and their voice in decisions made, in a way that cannot be understood by examining youth perspectives outside of a better-described context. Additional work in this area, particularly with a focus on how to enhance youth voice, would benefit the field.

Despite these limitations, these findings, which reflect that young people desire to have more voice in decision-making, but do not desire to be the only voice in decisions made, highlight an important area for future research. Additionally, this study found that young people desire to involve CPS, legal, caregivers, and others in decisions made, reflecting the variety of important people in their lives. Young people need strategies that ensure that they have the supportive adults in their lives represented when decisions are made, the tool used for data collection in this study is one such example. With a way to effectively communicate desired involvement of self and others in decision-making, youth are able to set parameters about how much voice they and others have, which may be important for preparing young people as they approach adulthood.

Acknowledgments:

This work was supported by the CareSource Foundation under a 2014 Signature Grant Award; the National Institutes of Health National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences under Award Number 5UL1TR001425–03, and the National Institutes of Health National Institute on Drug Abuse under Award Number K01 DA041620–01. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Ahrens KR, DuBois DL, Garrison M, Spencer R, Richardson LP, & Lozano P (2011). Qualitative exploration of relationships with important non-parental adults in the lives of youth in foster care. Children and Youth Services Review, 33(6), 1012–1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen M, & Bissell M (2004). Safety and stability for foster children: the policy context. Future Child, 14(1), 48–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Bar Association. (2017). Fostering Justice. [Google Scholar]

- Barford R, & Wattam C (1991). Children’s participation in decision-making. Practice, 5(2), 93–102. [Google Scholar]

- Barth RP, Green R, Webb MB, Wall A, Gibbons C, & Craig C (2008). Characteristics of out-of-home caregiving environments provided under child welfare services. Child Welfare, 87(3), 5–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrick JD (1998). When children cannot remain home: foster family care and kinship care. Future Child, 8(1), 72–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berzin SC, Singer E, & Hokanson K (2014). Emerging Versus Emancipating: The Transition to Adulthood for Youth in Foster Care. Journal of Adolescent Research. doi: 10.1177/0743558414528977 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Block SD, Oran H, Oran D, Baumrind N, & Goodman GS (2010). Abused and neglected children in court: Knowledge and attitudes. Child abuse & neglect, 34(9), 659–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkman WB, Sherman SN, Zmitrovich AR, Visscher MO, Crosby LE, Phelan KJ, & Donovan EF (2012). In their own words: adolescent views on ADHD and their evolving role managing medication. Academic pediatrics, 12(1), 53–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britto MT, Slap GB, DeVellis RF, Hornung RW, Atherton HD, Knopf JM, & DeFriese GH (2007). Specialists understanding of the health care preferences of chronically ill adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 40(4), 334–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cashmore J (2002). Promoting the participation of children and young people in care. Child abuse & neglect, 26(8), 837–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cashmore J, & Bussey K (1994). Perceptions of children and lawyers in care and protection proceedings. International Journal of Law, Policy and the Family, 8(3), 319–336. [Google Scholar]

- Cervesi C, Battistutta S, Martelossi S, Ronfani L, & Ventura A (2013). Health priorities in adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease: physicians’ versus patients’ perspectives. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, 57(1), 39–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapin Hall. (2017). Center for State Child Welfare Data. Retrieved from https://fcda.chapinhall.org/

- Chapman MV, Wall A, & Barth RP (2004). Children’s voices: the perceptions of children in foster care. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 74(3), 293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn ES, Trinkner RJ, Rebellon CJ, Van Gundy KT, & Cole LM (2012). Legal attitudes and legitimacy: Extending the integrated legal socialization model. Victims & Offenders, 7(4), 385–406. [Google Scholar]

- Conn AM, Szilagyi MA, Franke TM, Albertin CS, Blumkin AK, & Szilagyi PG (2013). Trends in child protection and out-of-home care. Pediatrics, 132(4), 712–719. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-0969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtney ME, Dworsky AL, Brown A, Cary C, Love K, & Vorhies V (2011). Midwest evaluation of the adult functioning of former foster youth: Outcomes at age 26. [Google Scholar]

- Coyne I, & Harder M (2011). Children’s participation in decision-making: Balancing protection with shared decision-making using a situational perspective. Journal of Child Health Care, 15(4), 312–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowe KM (2007). Using youth expertise at all levels: The essential resource for effective child welfare practice. New Directions for Student Leadership, 2007(113), 139–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day A, Riebschleger J, Dworsky A, Damashek A, & Fogarty K (2012). Maximizing educational opportunities for youth aging out of foster care by engaging youth voices in a partnership for social change. Children and Youth Services Review, 34(5), 1007–1014. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher PA, Chamberlain P, & Leve LD (2009). Improving the lives of foster children through evidenced-based interventions. Vulnerable Child Youth Stud, 4(2), 122–127. doi: 10.1080/17450120902887368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foxman ER, Tansuhaj PS, & Ekstrom KM (1989). Family members’ perceptions of adolescents’ influence in family decision making. Journal of Consumer Research, 15(4), 482–491. [Google Scholar]

- Greeson JKP, Thompson AE, & Arnett JJ (2014). doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199795574.013.18 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hallett C, Murray C, & Punch S (2003). Negotiating pathways to welfare In Hallett C, & Prout A (Ed.), Hearing the voices of children: Social policy for a new century. London, England: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hallett C, & Prout A (2003). Hearing the voices of children: Social policy for a new century. London, England: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Herrenkohl EC, Herrenkohl RC, & Egolf BP (2003). The psychosocial consequences of living environment instability on maltreated children. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 73(4), 367–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinds L (2007). Building police—Youth relationships: The importance of procedural justice. Youth justice, 7(3), 195–209. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson PR, Yoken C, & Voss R (1995). Family foster care placement: The child’s perspective. Child Welfare, 74(5), 959. [Google Scholar]

- Kisiel C, Fehrenbach T, Small L, & Lyons JS (2009). Assessment of complex trauma exposure, responses, and service needs among children and adolescents in child welfare. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 2(3), 143–160. [Google Scholar]

- Knopf JM, Hornung RW, Slap GB, DeVellis RF, & Britto MT (2008). Views of treatment decision making from adolescents with chronic illnesses and their parents: a pilot study. Health Expectations, 11(4), 343–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kümpel Nørgaard M, Bruns K, Haudrup Christensen P, & Romero Mikkelsen M (2007). Children’s influence on and participation in the family decision process during food buying. Young Consumers, 8(3), 197–216. [Google Scholar]

- Lipstein EA, Dodds CM, Lovell DJ, Denson LA, & Britto MT (2016). Making decisions about chronic disease treatment: a comparison of parents and their adolescent children. Health Expectations, 19(3), 716–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipstein EA, Muething KA, Dodds CM, & Britto MT (2013). “I’m the one taking it”: adolescent participation in chronic disease treatment decisions. Journal of Adolescent Health, 53(2), 253–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller VA, & Drotar D (2003). Discrepancies between mother and adolescent perceptions of diabetes-related decision-making autonomy and their relationship to diabetes-related conflict and adherence to treatment. Journal of pediatric psychology, 28(4), 265–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulvey EP, Steinberg L, Fagan J, Cauffman E, Piquero AR, Chassin L, . . . Hecker T (2004). Theory and research on desistance from antisocial activity among serious adolescent offenders. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 2(3), 213–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesmith A, & Christophersen K (2014). Smoothing the transition to adulthood: Creating ongoing supportive relationships among foster youth. Children and Youth Services Review, 37, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Palan KM, & Wilkes RE (1997). Adolescent-parent interaction in family decision making. Journal of Consumer Research, 24(2), 159–169. [Google Scholar]

- Pearl E (2000). Childhood Trust Events Survey: Child and Caregiver Versions. Trauma Treatment Training Center, Cincinnati, Ohio. [Google Scholar]

- Penner EK, Viljoen JL, Douglas KS, & Roesch R (2014). Procedural justice versus risk factors for offending: Predicting recidivism in youth. Law and Human Behavior, 38(3), 225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pösö T, Skivenes M, & Hestbæk A-D (2014). Child protection systems within the Danish, Finnish and Norwegian welfare states—time for a child centric approach? European Journal of Social Work, 17(4), 475–490. [Google Scholar]

- Powers LE, Geenen S, Powers J, Pommier-Satya S, Turner A, Dalton LD, . . . Swank P (2012). My Life: Effects of a longitudinal, randomized study of self-determination enhancement on the transition outcomes of youth in foster care and special education. Children and Youth Services Review, 34(11), 2179–2187. [Google Scholar]

- Quas JA, Wallin AR, Horwitz B, Davis E, & Lyon TD (2009). Maltreated children’s understanding of and emotional reactions to dependency court involvement. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 27(1), 97–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scannapieco M, Connell-Carrick K, & Painter K (2007). In their own words: Challenges facing youth aging out of foster care. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 24(5), 423–435. [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG, Campione‐Barr N, & Daddis C (2004). Longitudinal development of family decision making: Defining healthy behavioral autonomy for middle‐class African American adolescents. Child development, 75(5), 1418–1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strolin-Goltzman J, Kollar S, & Trinkle J (2010). Listening to the voices of children in foster care: youths speak out about child welfare workforce turnover and selection. Soc Work, 55(1), 47–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinkner R, & Cohn ES (2014). Putting the “social” back in legal socialization: Procedural justice, legitimacy, and cynicism in legal and nonlegal authorities. Law and Human Behavior, 38(6), 602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unrau YA (2007). Research on placement moves: Seeking the perspective of foster children. Children and Youth Services Review, 29(1), 122–137. [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Health and Human Services. (2016). AFCARS Report #23 – Preliminary estimates FY 2014 as of July 2015.

- Weisz V, Wingrove T, Beal SJ, & Faith-Slaker A (2011). Children’s participation in foster care hearings. Child abuse & neglect, 35(4), 267–272. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2010.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong NT, Zimmerman MA, & Parker EA (2010). A typology of youth participation and empowerment for child and adolescent health promotion. American Journal of Community Psychology, 46(1–2), 100–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wray‐Lake L, Crouter AC, & McHale SM (2010). Developmental patterns in decision‐making autonomy across middle childhood and adolescence: European American parents’ perspectives. Child development, 81(2), 636–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer-Gembeck MJ, Madsen SD, & Hanisch M (2011). Connecting the intrapersonal to the interpersonal: Autonomy, voice, parents, and romantic relationships in emerging adulthood. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 8(5), 509–525. [Google Scholar]