Rice DARX1 is a GDSL esterase that trims acetyl groups from excess acetylated arabinosyl substituents of arabinoxylan and modulates xylan conformation and secondary wall architecture.

Abstract

Acetylation, a prevalent modification of cell-wall polymers, is a tightly controlled regulatory process that orchestrates plant growth and environmental adaptation. However, due to limited characterization of the enzymes involved, it is unclear how plants establish and dynamically regulate the acetylation pattern in response to growth requirements. In this study, we identified a rice (Oryza sativa) GDSL esterase that deacetylates the side chain of the major rice hemicellulose, arabinoxylan. Acetyl esterases involved in arabinoxylan modification were screened using enzymatic assays combined with mass spectrometry analysis. One candidate, DEACETYLASE ON ARABINOSYL SIDECHAIN OF XYLAN1 (DARX1), is specific for arabinosyl residues. Disruption of DARX1 via Tos17 insertion and CRISPR/Cas9 approaches resulted in the accumulation of acetates on the xylan arabinosyl side chains. Recombinant DARX1 abolished the excess acetyl groups on arabinoxylan-derived oligosaccharides of the darx1 mutants in vitro. Moreover, DARX1 is localized to the Golgi apparatus. Two-dimensional 13C-13C correlation spectroscopy and atomic force microscopy further revealed that the abnormal acetylation pattern observed in darx1 interrupts arabinoxylan conformation and cellulose microfibril orientation, resulting in compromised secondary wall patterning and reduced mechanical strength. This study provides insight into the mechanism controlling the acetylation pattern on arabinoxylan side chains and suggests a strategy to breed robust elite crops.

INTRODUCTION

Plant cells are encased in structurally diverse polymers, which are assembled into a dynamic network, forming the plant cell walls. The cell wall represents a complex structure that plays many fundamental roles in plants, including determining plant growth and development and providing structural integrity and mechanical support for the plant body (Bacic et al., 1988; Carpita and Gibeaut, 1993; Somerville et al., 2004). Land plants harbor more than 40 types of cells with varied morphologies and functions (Farrokhi et al., 2006). The cell-wall compositions and organizations in these cell types are different and can change dynamically (Burton et al., 2010; Loqué et al., 2015), posing challenges to understanding the functions of cell-wall constituents. Heterogeneity in cell-wall chemistry and structure also suggests that plants have evolved regulatory mechanisms to control cell-wall composition and organization in response to internal and environmental stimuli.

Cell-wall polysaccharides are composed of at least 14 sugars that are organized into linear polymers with or without substituents through more than four linkages. Three kinds of modifications are incorporated in some of these sugars and substantially modify the physicochemical properties. Pectin esterification affects cell-wall plasticity and mechanical strength (Bosch and Hepler, 2005), while feruloylation on arabinoxylan side chains offers a way of bridging xylan and lignin (de O Buanafina, 2009). Compared with the level and position of these two modifications, which are constrained to a few epitopes, O-acetyl groups are widespread in most cell-wall polymers (Kiefer et al., 1989; Ishii, 1991). At least eight of 14 cell-wall–composing monosaccharides have acetylated forms; some monosaccharides can be substituted with two O-acetyl groups, such as the galactosyl residue on xyloglucan branches, the xylosyl residue on xylan backbone, and the galacturonosyl residue on pectic polymers (Gille and Pauly, 2012). In plants and bacteria, the acetylation pattern, which comprises acetate quantity and distribution along the cell-wall polymers, varies across developmental stages and species (Janbon et al., 2001; Teleman et al., 2002; Gille et al., 2011; Yuan et al., 2016). Compromised acetylation patterns often result in abnormalities in either plant growth or stress resistance (Xin and Browse, 1998; Vogel et al., 2004; Zhu et al., 2014; Gao et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2017). Disrupting the characteristic acetylation profile on the Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) xylan backbone causes xylan misfolding and interferes with the interactions with cellulose (Busse-Wicher et al., 2014; Grantham et al., 2017). Excess acetylation of the rice (Oryza sativa) xylan backbone alters secondary wall patterning and plant development (Zhang et al., 2017). These data suggest that control of the cell-wall acetylation pattern offers a precise mechanism to manipulate cell-wall properties and organization, thereby modulating cell-wall biological functions.

Despite the prevalence of acetyl modifications on cell-wall polymers, the underlying mechanism for cell-wall acetylation control has remained mysterious until recent years. Mutant screens and biochemical studies have revealed that three groups of proteins, including TRICHROME BIREFRINGENCE-LIKE proteins, REDUCED WALL ACETYLATION proteins, and ALTERED XYLOGLUCAN9 are involved in acetylation of cell-wall polymers (Gille et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2011; Manabe et al., 2011; Xiong et al., 2013; Schultink et al., 2015). Furthermore, plant deacetylases, such as a CARBOHYDRATE ESTERASE13 member and a GDSL esterase/lipase protein (GELP) family member, have been demonstrated to trim acetyl groups from polysaccharides (Gou et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2017). These findings open a door to unravel the mechanism for precise regulation of cell-wall acetylation.

After nonacetylated cellulose, arabinoxylan is the second most abundant polysaccharide in the plant cell wall and is a central polymer that is substituted with the majority of acetyl esters (Wende and Fry, 1997; Chiniquy et al., 2012; Rennie and Scheller, 2014; Smith et al., 2017). The acetate patterns on the xylan backbone and arabinosyl substituents affect the physicochemical properties of arabinoxylan and determine how xylan interacts with other cell-wall polymers (Grantham et al., 2017). However, in contrast with the heavily acetylated backbone, arabinosyl side chains have been rarely reported to bear acetyl groups, and enzymes that catalyze acetylation and deacetylation of arabinosyl side chains have not been identified (Grantham et al., 2017).

Here, we report a previously uncharacterized GELP member in rice that functions as an arabinosyl deacetylase and catalyzes the removal of acetyl residues from xylan arabinosyl side chains. Mutations in this gene alter the acetylation pattern on xylan side chains and affect arabinoxylan conformation and cellulose microfibril organization. Our study reveals a mechanism that regulates the acetylation pattern on arabinoxylan side chains. Manipulating this mechanism may improve the mechanical strength of plants and thus have applications in crop breeding.

RESULTS

Identification of Deacetylases Governing the Acetylation Pattern on Rice Arabinoxylan

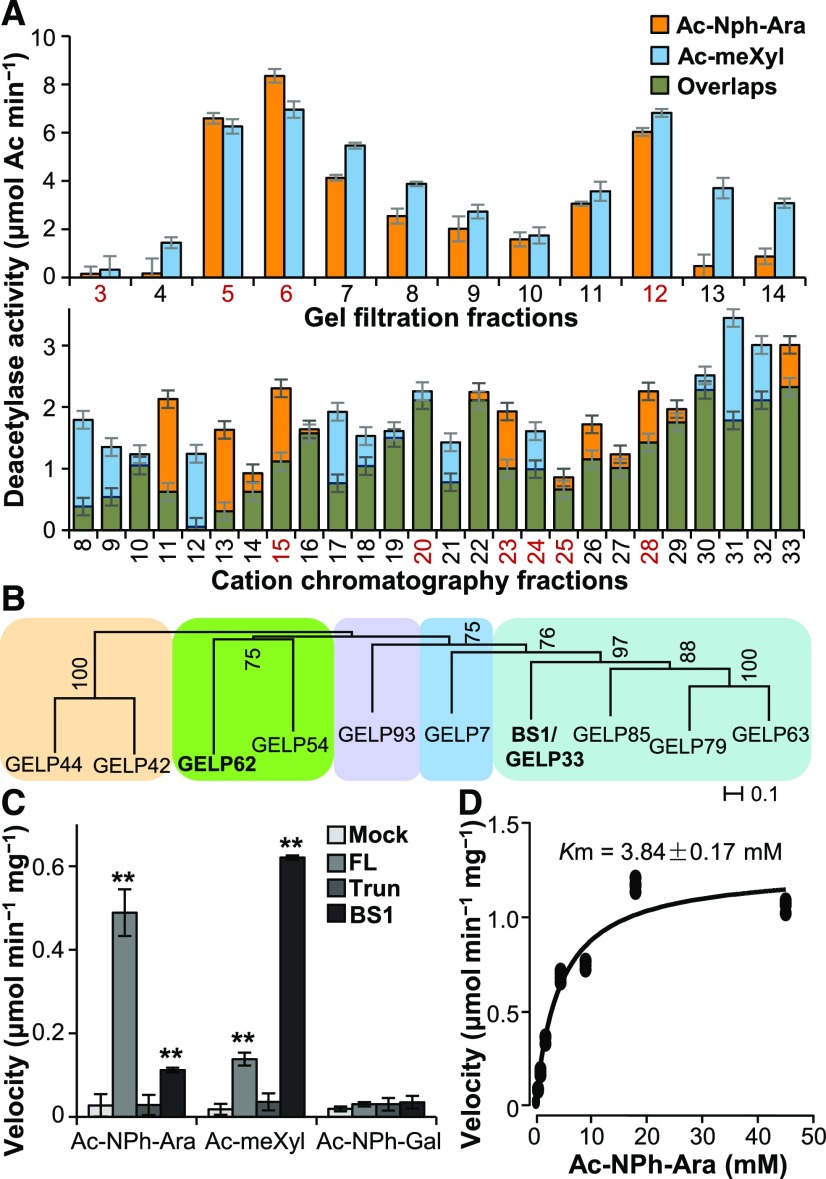

To determine how the acetylation pattern of arabinoxylan is modulated in rice, we enzymatically screened for glycosyl acetyl esterases that remove acetyl groups from xylosyl and arabinosyl residues, which are the two major sugars in arabinoxylan, using microsomes extracted from the internodes of rice plants. Two fully acetylated glycosides, namely 2,3,4-O-acetyl methyl xyloside (Ac-meXyl) and 2,3,5-O-acetyl p-nitrophenyl α-l-arabinofuranoside (Ac-NPh-Ara), were used as the substrates. After examining the acetylesterase activities in the microsomes (Supplemental Figure 1A), we fractionated the solubilized microsomes using a Superdex 200 size-exclusion column or cation and anion exchange columns. By subjecting the collected fractions to enzymatic assays, we detected deacetylase activities on either xyloside or arabinoside substrates in some fractions (Figure 1A; Supplemental Figure 1B), suggesting that these fractions may harbor deacetylases. Fractions containing BRITTLE LEAF SHEATH1 (BS1), a previously reported xylan deacetylase (Zhang et al., 2017), exhibited xylosyl deacetylase activity (Figure 1A; Supplemental Figure 1C), confirming the veracity of this experimental approach.

Figure 1.

Identification of Arabinoxylan Deacetylates.

(A) Deacetylase activity analysis of the protein fractions separated on a gel filtration Superdex 200 column (upper) and a cation-exchange chromatography HiTrap SP column (lower). The proteins present in the fractions numbered in red were separated by SDS-PAGE and digested with trypsin. The tryptic fragments were subjected to LC–MS analysis. Error bars = mean ± SD of three replicates of assays with independent proteins. **P < 0.01 by Welch’s unpaired t-test.

(B) Phylogenetic analysis of the GELPs identified by LC–MS. Bootstrap percentages are shown at the nodes. Color blocks sequentially label the IVd, Ix, Id, Ia, and Ib clades of the GELP family from left to right (Volokita et al., 2011; Chepyshko et al., 2012). “Ix” indicates the unclustered members of subfamily I.

(C) Quantification of deacetylase activities on acetylated sugars. One microgram of purified recombinant FL- and Trun-GELP62 (FL and Trun) and BS1 was incubated with 5 mM of Ac-meXyl, Ac-NPh-Ara, or Ac-NPh-Gal substrate. “Mock” represents the negative controls in the absence of recombinant proteins. Error bars = mean ± SD of three replicates of assays with independent proteins. **P < 0.01 by Welch’s unpaired t-test.

(D) Determination of the Km value of FL-GELP62 for the Ac-NPh-Ara substrate using a Michaelis–Menten plot. The Km value represents the mean of three replicates of assays with independent proteins.

To identify candidate deacetylases, we subjected the fractions that exhibited relatively high activities on Ac-NPh-Ara and Ac-meXyl substrates to liquid chromatography-coupled mass spectrometry (LC–MS) analysis. The fractions from gel filtration and cation-exchange analyses (numbered in red in Figure 1A) were separated by SDS-PAGE. Proteins ranging from 15 to 130 kD were collected and digested with trypsin for LC–MS analysis. We identified 10 GELP proteins as possible candidates that may catalyze arabinoxylan deacetylation (Supplemental Table 1).

Phylogenetic analysis clustered these 10 GELP proteins into five clades. Among these candidates, GELP62 is highly and ubiquitously expressed in rice (Supplemental Figures 1D and 1E) and belongs to a different clade than BS1 (Figure 1B; Supplemental Data Set), suggesting that GELP62 may have distinct enzymatic specificity from BS1.

To test this hypothesis, we subjected GELP62 to an in vitro verification of deacetylase activity. According to the annotations in the Michigan State University Rice Genome Annotation Release 7 (LOC_Os05g06720.1) and the Rice Annotation Project Database (Os05g0159300), the hypothetical nucleotide sequence encoding GELP62 is 636 bp. As GELP62 is predicted to lack the conserved GDS motif (Supplemental Figure 2A), it is classified as the truncated (Trun) version. To determine the full coding sequence, we performed an RNA sequencing analysis and mapped the reads obtained from the wild-type plants onto the GELP62 genomic region. The transcripts included an exon upstream of a 9-kb intron (Supplemental Figures 2B and 2C). Hence, the full-length (FL) version of GELP62 is likely 1,371 bp in length (LOC_Os05g06720.4) and encodes a 456-amino acid protein containing all four conserved domains of GELP proteins (Supplemental Figure 2A).

We then heterologously expressed FL- and Trun-GELP62 in Pichia pastoris and incubated the purified recombinant proteins (Supplemental Figure 1F) with Ac-meXyl, Ac-NPh-Ara, and a negative control, fully acetylated p-nitrophenyl galactoside (Ac-NPh-Gal). In contrast with BS1, which was most active on Ac-meXyl, FL-GELP62 exhibited major activity on Ac-NPh-Ara, whereas the Trun version was not active (Figure 1C). Taken together with the observation that the predicted FL-GELP62 three-dimensional structure contains a classic SGNH catalytic triad (Supplemental Figure 2D), the FL-GELP62 is functional. Furthermore, the esterase activity of FL-GELP62 displayed saturable kinetics with a Km value of 3.84 mM (Figure 1D), which is comparable to that of BS1 (Zhang et al., 2017). Hence, we designated GELP62 as a putative DEACETYLASE ON THE ARABINOSYL SIDECHAIN OF XYLAN1 (DARX1).

Lesions in DARX1 Cause Excess Acetyl Modification on the Arabinosyl Side chain of Xylan

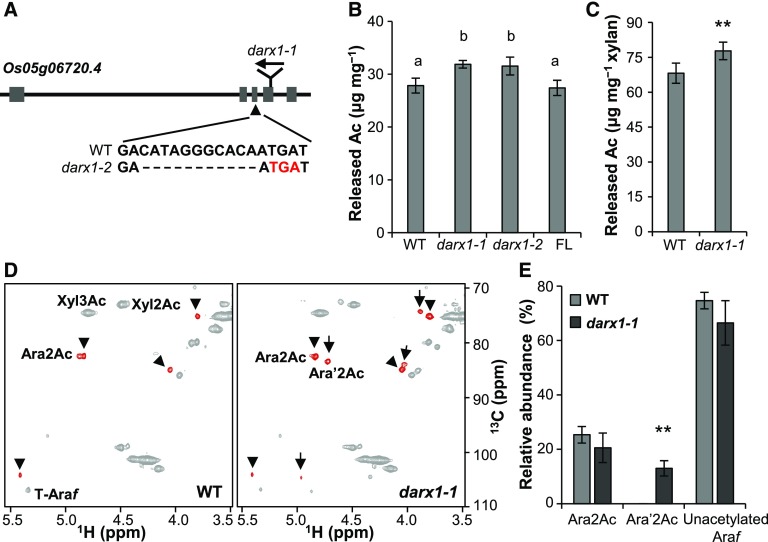

To obtain genetic evidence for DARX1 function, a Tos17 insertional mutant (darx1-1) was isolated (Figure 2A; Supplemental Figures 3A and 3B). The insertion causes undetectable levels of DARX1 transcript as revealed by RNA gel blotting analysis (Supplemental Figure 3D). Additionally, immunoblotting analysis of total membrane proteins extracted from plants with a DARX1 polyclonal antibody revealed a single band in the wild-type plants and no bands in the mutant plants (Supplemental Figure 3E). This result demonstrated the specificity of the DARX1 antibody and indicated that darx1-1 is a null mutant. Next, we generated another allele by CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing. darx1-2, which harbors an 11-bp deletion that introduces a premature translational stop codon, is expected to produce a truncated DARX1 protein (Figure 2A; Supplemental Figures 3A and 3B). Total acetate content analysis revealed that both mutants have increased amounts of wall-bound acetyl esters (Figure 2B); amounts were restored to wild-type levels by expressing FL DARX1 in the darx1-1 mutant (Figure 2B; Supplemental Figures 3A and 3C).

Figure 2.

Isolation and Characterization of the darx1/gelp62 Mutants.

(A) Schematic of DARX1 gene structure and the mutation sites of the indicated mutants. The boxes and lines in the diagram indicate exons and introns, respectively. The arrow indicates the insertion of the Tos17 transposon. The arrowhead indicates a deletion mutation in darx1-2 that results in a premature translational stop codon (red letters).

(B) The acetyl ester content in the cell-wall residues of mature internodes. Error bars = mean ± SD (for three b biological replicates of pooled internodes). The letters “a” and “b” indicate statistically significant differences according to the variance analysis and Tukey’s test (P < 0.05). WT, wild type; FL, full-length DARX1.

(C) Measurement of the acetyl ester level in the acetyl–xylan extracted from the wild-type and darx1-1 mature internodes. Error bar = mean ± sd (for three biological replicates of pooled internodes). **P < 0.01 by Welch’s unpaired t test. WT, wild type.

(D) Representative HSQC spectra of acetyl–xylan of wild-type and darx1-1 plants. Signals of acetylated arabinosyl residues are in red. Arrowheads and arrows indicate Ara2Ac and Ara′2Ac, respectively. The chemical shifts of Ara2Ac, O-2 acetylated arabinosyl residues and Ara′2Ac, O-2 acetylated arabinosyl residues on the O-2 acetylated xylosyl backbone, are described in Supplemental Table 2. WT, wild type.

(E) Quantification of arabinosyl residues in the wild-type and mutant acetyl–xylan based on examinations of HSQC spectra. The data are expressed as the abundance relative to the total Ara signals. Error bars = mean ± sd (for three biological replicates of pooled internodes). **P < 0.01 by Welch’s unpaired t test. WT, wild type.

To determine which polymer is the source of excessive acetate esters, we separated the wall residues of mature internodes into pectin-containing and pectin-free fractions. The acetate content analysis revealed that excess acetates were derived from the pectin-free fraction, which contains a large amount of arabinoxylan (Supplemental Figure 4A). Examination of acetate content in the dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)-extracted acetyl–xylan confirmed that the excess acetates were derived from arabinoxylan (Figure 2C; Supplemental Figure 4B).

To identify which arabinoxylan sites bound to the additional acetyl groups in the darx1 mutants, we subjected intact acetyl–xylans to nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) analyses. Heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC) analysis revealed that the xylan backbone was decorated with monoacetyl groups and that the relative abundance of acetyl groups attached to the xylan backbone at the O-2 (Xyl2Ac) or O-3 (Xyl3Ac) sites was not significantly altered in darx1 (Figure 2D; Supplemental Figures 4C and 4D). Interestingly, although the O-2 acetylated arabinosyl residues (Ara2Ac) with the characteristic signal of the acetyl modified carbon (4.83 ppm for 1H and 82.41 ppm for 13C) were comparable in the wild type and mutants, an additional acetylated arabinosyl residue with the characteristic signal (4.71 ppm for 1H and 83.36 ppm for 13C) was present in the mutants but not in the wild type (Figures 2D and 2E). We then implemented several approaches to characterize this extra residue.

Total correlation spectroscopy (TOCSY) analysis indicated that the hydrogen signals (H1 4.96 ppm, H3 3.88 ppm, H4 4.03 ppm, and H5 3.45 ppm) were associated with the characteristic hydrogen signals in this extra residue (Supplemental Table 2; Supplemental Figure 5A). Similarly, the associated carbons were assigned using two-dimensional (2D) heteronuclear multiple bond correlation (HMBC) and HSQC analysis (Figure 2D; Supplemental Figure 5C; Supplemental Table 2). Although this extra residue had adjacent chemical shifts similar to Ara2Ac on the carbon–hydrogens, it exhibited an ∼0.5-ppm downfield shift on H1 (on Carbon 1) compared with Ara2Ac (Figure 2D). This finding suggests that its attachment position on the xylosyl backbone is different from Ara2Ac and we thus designated it as Ara′2Ac.

Moreover, based on a nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscopy (NOESY) analysis, the interglycosidic NOE connection between H1 (4.96 ppm) of Ara′2Ac and H2 (4.61 ppm) of the O-2 acetylated xylosyl backbone indicated that an Ara′2Ac substitution was present on the O-2 acetylated xylosyl backbone. The connection between methyl hydrogen on acetyl groups and H2 (on Carbon 2) of Ara′2Ac suggested that the acetyl group of Ara′2Ac resided on the hydroxyl at Carbon 2 (Supplemental Figures 5B to 5D). These correlation spectroscopy analyses support that this extra sugar, Ara′2Ac, is likely to be an O-2 acetylated arabinosyl residue. Additionally, it is likely that Ara′2Ac is substituted on the Carbon 3 of an O-2 acetylated xylosyl residue (Supplemental Figure 5E).

To determine whether mutation of DARX1 alters the xylan side-chain profile, we analyzed the arabinoxylo–oligosaccharides generated by digesting the wild-type and mutant alkali-extracted arabinoxylan with a xylanaseof Glycosyl hydrolase family 11 (GH11) using a DNA sequencer-assisted saccharide analysis in high throughput. The similar oligosaccharide profiles of wild-type and darx1 extracts suggest that the DARX1 mutation does not significantly alter the pattern of arabinosyl substitution on xylan (Supplemental Figure 6).

Given that Ara′2Ac is the specific defect arising from DARX1 mutation, DARX1 is likely an arabinosyl deacetylase of arabinoxylan with regiospecificity.

DARX1 Removes Acetyl Esters from Acetylated Arabinoside and Arabinoxylo–Oligosaccharide

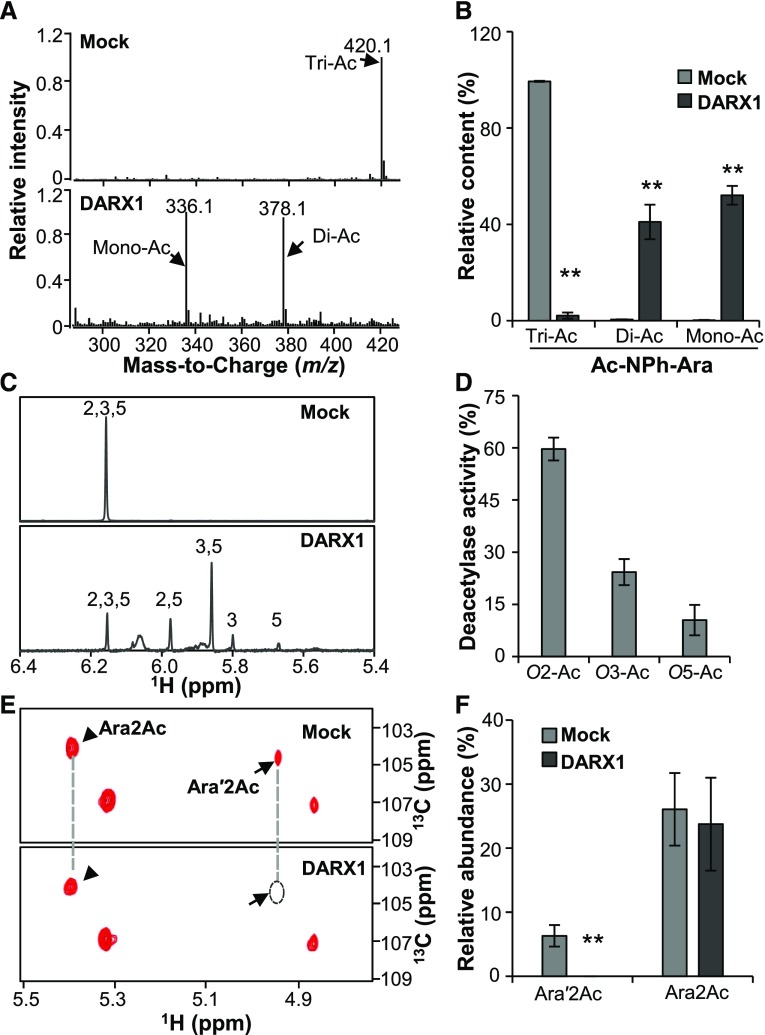

We next conducted a series of biochemical assays to elucidate the enzymatic activities of DARX1. First, we investigated how many acetyl esters can been removed by DARX1. Ac-NPh-Ara, which has three acetyl epitopes, was incubated with purified recombinant DARX1 and then subjected to LC–MS analysis. Diacetylated and monoacetylated NPh-Ara were detected in the reactions (Figures 3A and 3B), indicating that one or two acetyl epitopes could be removed by DARX1.

Figure 3.

DARX1 Catalyzes the Deacetylation of Acetylated Arabinoside and Arabinoxylo–Oligosaccharide.

(A) Representative LC-Quadrupole Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometer spectra of Ac-NPh-Ara after incubation with recombinant DARX1 proteins.

(B) Quantification of Di-Ac-NPh-Ara and Ac-NPh-Ara generated in the reactions shown in (A). Error bars = mean ± sd (n = 3 replicates of assays with independent proteins). **P < 0.01 by Welch’s unpaired t test.

(C) Anomeric region of proton NMR spectra of the Ac-NPh-Ara products generated by partial digestion with DARX1. Numbers on the signal peaks indicate the retained acetyl groups.

(D) Quantification of the acetyl groups released from the reactions in (C). O2-Ac, O3-Ac, and O5-Ac indicate the acetyl groups released from O-2, O-3, and O-5 postions of acetylated arabinoside, respectively. Error bars = mean ± sd (n = 3 replicates of assays with independent proteins). **P < 0.01 by Welch’s unpaired t test.

(E) Representative HSQC spectra of xylooligosaccharides after DARX1 treatment. Arrowheads and arrows indicate the signals of Ara2Ac and Ara′2Ac, respectively.

(F) Quantification of the acetyl groups released from the reactions shown in (E). The data are expressed as signal abundance relative to the total integral signals of Ara. “Mock” in this figure represents the negative controls in the absence of DARX1. Error bars = mean ± sd (n = 3 replicates of assays with independent proteins). **P < 0.01 by Welch’s unpaired t test.

To further determine the regiospecificity of DARX1, we shortened the reaction time to achieve partial digestion of Ac-NPh-Ara. 2,5-O-acetyl, 3,5-O-acetyl, 3-O-acetyl, and 5-O-acetyl arabinosides were recognized and quantified by proton NMR and TOCSY assays (Figure 3C; Supplemental Figure 7A). Compared with 25% and 12% of acetyl groups derived from the O-3 and O-5 sites of acetylated arabinosides, ∼60% were released from the O-2 position (Figure 3D). This finding suggests that DARX1 is an arabinoside deacetylase with a preference for O-2 acetyl groups.

Considering that the native substrate of DARX1 in plants would be arabinoxylan or oligosaccharides, we incubated recombinant DARX1 protein with a xylan oligosaccharide mixture produced by cleaving the acetyl–xylan of darx1 with a GH11 xylanase. The Ara′2Ac signals were completely abolished after incubation with DARX1, indicating that DARX1 can release acetyl groups from Ara′2Ac (Figures 3E and 3F; Supplemental Figure 7B). Such activity corroborates the wall defects observed in the darx1 mutants (Figure 2E; Supplemental Figure 5). Therefore, DARX1 is an arabinoxylan deacetylase with regiospecificity.

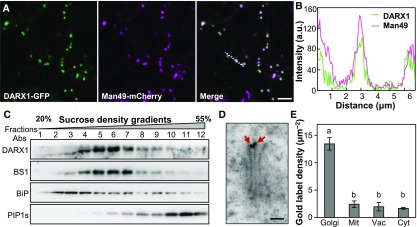

DARX1 Is Localized to the Golgi

Deacetylation occurs in the Golgi apparatus and apoplast. To determine the subcellular location of DARX1, we fused the FL coding sequence of DARX1 in-frame to the sequence encoding green fluorescent protein (GFP) at the 3ʹ end and then cotransfected tobacco leaves with this construct and one for the mCherry-tagged Man49 Golgi marker. The resulting overlaid signals suggested that DARX1 is a Golgi-localized protein (Figures 4A and 4B). To confirm this localization in planta, we examined the DARX1-resident profile by Suc density centrifugation using the DARX1-specific antibody (Supplemental Figure 3E). The distribution pattern of DARX1 was almost identical to that of BS1, which is a Golgi-localized deacetylase (Zhang et al., 2017). However, DARX1 distribution was distinct from that of the endoplasmic reticulum marker Binding immunoglobulin protein (BiP) and the plasma membrane-marker Plasma membrane intrinsic protein 1s (PIP1s; Figure 4C). Furthermore, immunogold labeling with DARX1-specific antibody verified its localization in Golgi stacks (Figures 4D and 4E). Therefore, DARX1 is a Golgi-targeted arabinosyl deacetylase.

Figure 4.

DARX1 Is Localized to the Golgi Apparatus.

(A) Cotransfection of rice protoplasts to express GFP-fused DARX1 and mCherry-tagged Man49. Scale bar = 2 μm.

(B) Intensity plot of DARX1-GFP and Man49-mCherry across the dotted line shown in (A).

(C) Immunoblot analysis of the fractions obtained from wild-type seedlings by Suc density gradient centrifugation. Anti-BS1, anti-BiP, and anti-PIP1s antibodies were used to indicate the Golgi apparatus, endoplasmic reticulum, and plasma membrane, respectively. Abs, antibodies.

(D) Immuno-gold labeling of DARX1, showing DARX1 localized in the Golgi stacks. The red arrows indicate gold particles. Scale bar = 100 nm.

(E) Quantification of gold particles per area of the indicated organelles. Error bars = mean ± se. n = 50 images of ultrathin sections from three plants. Mit, mitochondria; Vac, vacuole; Cyt, cytoplasm. The letters “a” and “b” indicate significant differences according to variance analysis and Tukey’s test (P < 0.01).

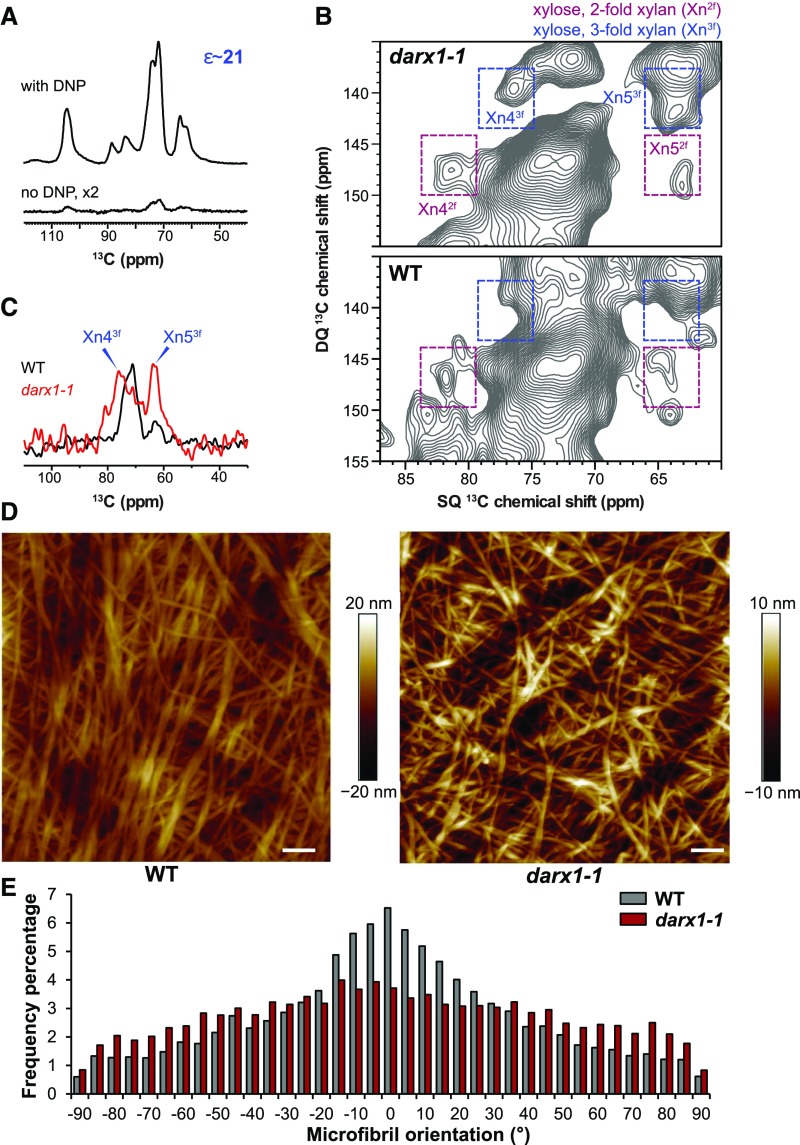

darx1 Has Compromised Cellulose-Xylan Interactions and Microfibril Orientation

Next, we investigated the effect of the aberrant acetylation profiles in the darx1 mutants on arabinoxylan conformation and cell-wall architecture. 2D 13C−13C correlation INADEQUATE spectroscopy analysis was applied to probe xylan conformation in the field-harvested mature internodes of wild-type and darx1 plants. The NMR sensitivity was boosted 20 to 21 times using the cutting-edge dynamic nuclear polarization (DNP) technique (Figure 5A), making it feasible to measure 2D correlation spectra without isotope enrichment. The wild-type sample was dominated by xylan in a flat-ribbon conformation (twofold helical screw) with negligible signals for the threefold conformer (Figure 5B). Based on previous reports, in which xylan that has a flat-ribbon conformation, twofold xylan was annotated as binding to cellulose microfibrils (Simmons et al., 2016; Grantham et al., 2017) and threefold xylan was interpreted as forming a hydrated matrix and contacting lignin nanodomains (Kang et al., 2019). The dominating twofold xylan signals in the wild-type internodes indicated extensive interactions between xylan and cellulose microfibrils. However, the two- and threefold signals were nearly equal in the darx1 internodes (Figure 5C). Considering the substantial upsurge of threefold xylan in the darx1 plants (Figure 5B), we concluded that mutation of DARX1 alters the conformation of xylan and thereby perturbs xylan–cellulose interactions.

Figure 5.

DARX1 Is Crucial for Xylan Binding to Cellulose.

(A) DNP enhances NMR sensitivity 21-fold in the wild-type sample.

(B) 2D 13C-13C correlation spectra measured on the unlabeled matured wild-type and darx1-1 internode slices in the natural isotope abundance (1%). The double-quantum (DQ) shift is the sum of the single-quantum (SQ) shifts of two bonded (J-coupled) 13C nuclei. The two- and threefold xylan signals are labeled in purple and blue, respectively. For example, Xn43f represents Carbon 4 of threefold xylan. WT, wild type.

(C) A cross section of threefold xylan 13C extracted at the 141-ppm double-quantum (DQ) shift from the 2D spectra in (B). WT, wild type.

(D) AFM of metaxylem cell walls, showing cellulose macrofibrils/microfibrils of wild-type and darx1-1 plants. Scale bars = 100 nm. WT, wild type.

(E) Distribution of macrofibril/microfibril orientation. The orientation of macrofibril/microfibril is represented as percentage frequency of the orientation of macrofibril/microfibril segments (snakes) identified using the software SOAX (n = 60,000 snakes from three images of three cells of three individual plants). WT, wild type.

To explore whether the reduced cellulose-xylan interactions affect cellulose microfibril deposition, we used atomic force microscopy (AFM) to examine the cellulose microfibrils in metaxylem cells of the wild-type and mutant mature internodes. In contrast with the wild-type cellulose microfibrils that were oriented in an orderly manner, the mutant plants displayed microfibrils that were randomly oriented (Figures 5D and 5E). Furthermore, fewer macrofibrils were aggregated in the darx1 mutants than in the wild type (Figure 5D), but the diameter of cellulose macrofibrils was not significantly changed (Supplemental Figure 8). Therefore, DARX1 is indispensable for cellulose microfibril orientation.

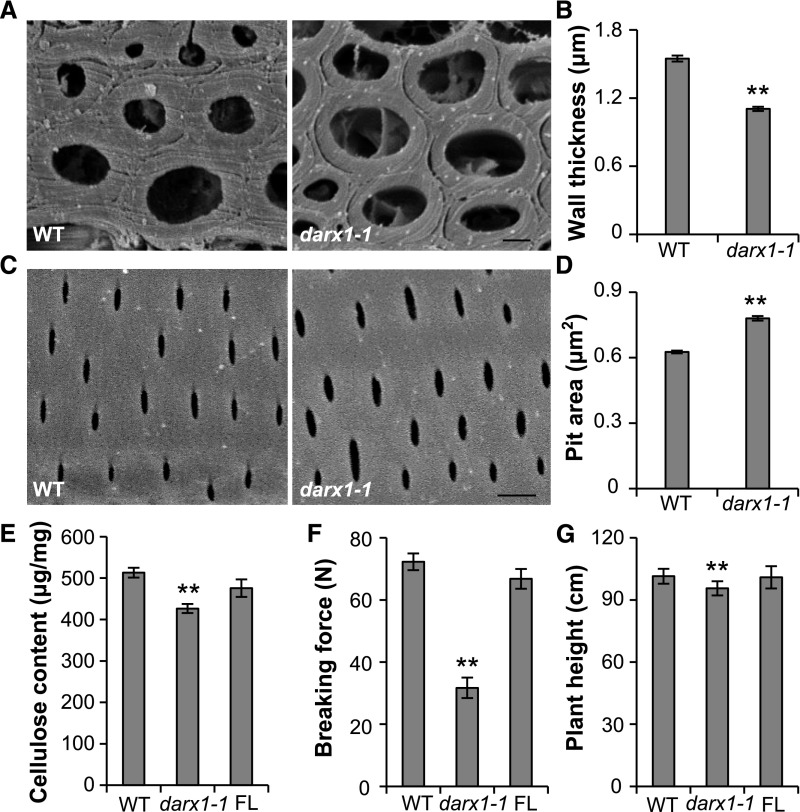

DARX1 Affects Secondary Wall Properties Resulting in Developmental Phenotypes

To determine the effect of the excess acetylation in the darx1 mutants on secondary cell-wall organization, we analyzed the sclerenchyma fiber and metaxylem cells that possess secondary cell walls by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The wall thickness of sclerenchyma fiber cells in the darx1 mutant was significantly reduced (Figures 6A and 6B), whereas the pit size in metaxylem was increased (Figures 6C and 6D). Furthermore, the content of cellulose, another major component of secondary cell walls, was decreased in the darx1 plants (Figure 6E). Hence, the darx1 mutants have disrupted secondary wall formation and patterning, which results in reduced mechanical strength manifesting through easily broken internodes (Figure 6F) and drooping leaves (Supplemental Figure 3A), and slightly decreased plant height (Figure 6G) in the darx1 plants. Moreover, the abnormal cellulose content and morphological phenotypes were fully rescued in plants expressing FL DARX1 (Figures 6E to 6G). These findings suggest the importance of DARX1 in secondary wall organization and plant growth.

Figure 6.

DARX1 Is Required for Mechanical Strength and Plant Height.

(A) Representative graphs of SEM of sclerenchyma cells from wild-type and darx1-1 plants. Scale bar = 2 μm. WT, wild type.

(B) Quantification of wall thickness examined in (A). Error bars = means ± se (n = 75 and 94 cells from five wild-type and darx1-1 plants, respectively). WT, wild type.

(C) The representative graphs of SEM of the wild-type and darx1-1 metaxylem with pitted patterns. Scale bar = 2 μm. WT, wild type.

(D) Quantification of pit size examined in (C). Error bars = mean ± se (n = 637 and 719 pits of at least six cells from five wild-type and darx1-1 plants, respectively). WT, wild type.

(E) Cellulose content of the wild-type and mutant plants. Error bars = mean ± sd (n = 3 biological replicates of pooled internodes). WT, wild type.

(F) Force required to break internodes of the wild-type and darx1-1 plants. Error bars = mean ± se of 20 plants. **P < 0.01 by Welch’s unpaired t test. WT, wild type.

(G) Plant height of wild-type and darx1-1 plants. Error bars = mean ± se of 20 plants. **P < 0.01 by Welch’s unpaired t test. WT, wild type.

DISCUSSION

Acetylation is a prevalent modification on cell-wall polymers. Due to its importance in glycan structure and function, acetylation patterns are tightly controlled by the antagonistic actions of acetyltransferases and deacetylases. Compared with tens of polysaccharide acetyltransferase candidates (Gille et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2011; Manabe et al., 2011; Xiong et al., 2013; Schultink et al., 2015; Pauly and Ramírez, 2018), few deacetylases were identified until the discovery of a xylan backbone deacetylase; this finding indicated the involvement of a large family of esterases in polysaccharide deacetylation (Zhang et al., 2017). Hence, deacetylases that regulate acetylation profiles during polysaccharide biosynthesis or turnover may have comparable substrate specificities and/or regiospecificities (Gou et al., 2012; Scheller, 2017; Zhang et al., 2017).

In this study, we identified 10 GDSL esterase candidates of unknown function using an enzymatic screen. Among these candidates, we showed that DARX1 possesses arabinosyl-deacetylation activity. We further demonstrated that DARX1 specifically releases acetyl groups from the acetylated arabinosyl substituents of xylooligosaccharides, in agreement with the altered acetate patterns in darx1 mutants. Because such enzyme activity has not previously been reported in plants, bacteria or fungi, DARX1 is the first known arabinosyl deacetylase that acts on arabinoxylan.

Ara is a central monosaccharide present in arabinoxylan, pectic rhamnogalacturonan I and rhamnogalacturonan II, arabinogalactan proteins, and xyloglucan. Arabinofuranose with α-(1,2) or α-(1,3)-linkage to xylan is a characteristic side chain found on monocot arabinoxylan (Wende and Fry, 1997; Burton et al., 2010; Chiniquy et al., 2012). Similar to glucuronic acids substituted at the O-2 position of Xyl residues of glucuronoxylan, the side-chain level and pattern affect the physicochemical properties and conformations of xylans (Grantham et al., 2017). However, acetates on arabinosyl residues have rarely been reported (Ishii, 1991), and the corresponding acetyltransferases and deacetylases have not been identified. It remains unclear whether the acetylated arabinosyl residue exists in plants and what functions it would mediate. A recent study revealed that excess acetylation of the xylan backbone results in a substantial amount of acetylated arabinosyl substituents (Zhang et al., 2017); this finding brought this epitope to our attention. Here, we identified DARX1 as a deacetylase that removes acetyl groups from the arabinosyl residues of xylan. Lesions in deacetylases, such as BS1 and DARX1, provide opportunities to investigate the acetylated polysaccharide intermediates that are not retained in wild-type plants. Based on our findings and recent progress in the field of acetyltransferase biology (Gille and Pauly, 2012; Xiong et al., 2013; Zhu et al., 2014; Yuan et al., 2016; Zhong et al., 2017), we propose that polysaccharide acetylation may occur at more glycosyl residues and would be catalyzed by more regiospecific acetyltransferases and deacetylases than we initially expected. The acetyl groups on the polysaccharide backbone and side chains are likely catalyzed by a series of acetyltransferases and deacetylases in multiple steps. Our study therefore highlights a complex and precise mechanism for acetylation profile control.

The complexity of polysaccharide acetylation is driven by subcellular compartmentalization of the enzymes. Acetylation occurs in the Golgi apparatus, the hub for cell-wall polymer biosynthesis (Gille and Pauly, 2012; Zhang et al., 2017), and in the apoplast, where cell-wall remodeling takes place (Gou et al., 2012). Based on the behavior of the two Golgi-localized deacetylases DARX1 and BS1 (Zhang et al., 2017), the newly synthesized polysaccharides are probably excessively acetylated; this feature might be essential for maintaining the glycan intermediates in a soluble or other unknown status within the Golgi stacks. After processing many enzymatic reactions, the cell-wall polymers could be acetylated and deacetylated until secretion. Moreover, deacetylation likely occurs also in the postbiosynthesis stages. For example, deacetylase candidates were identified in secretome analyses (Chen et al., 2009; Cho et al., 2009); an apoplastic carbohydrate esterase was found to catalyze pectin deacetylation (Gou et al., 2012). Hence, the acetylation pattern is tightly controlled at multiple levels during cell-wall biogenesis.

The precise regulation of acetylation confers the acetylation-relevant proteins with regulatory roles in the control of the glycan properties and biological functions of the cell wall (Xin and Browse, 1998; Vogel et al., 2004; Zhu et al., 2014; Gao et al., 2017). Due to its interaction with cellulose and lignin, xylan is indispensable for secondary cell-wall organization and function (Gille and Pauly, 2012). The acetate pattern on the xylan backbone determines the folding of this polymer and its binding to cellulose (Grantham et al., 2017). However, the influence of acetylated side chains on xylan conformation remains unclear. In this study, excess acetylation on the xylan arabinosyl side chain alters the ratio of the two- and threefold conformers, which interrupts the interactions with cellulose microfibrils based on the solid-NMR analysis. Interestingly, the abnormal xylan conformation in darx1 disrupts cellulose microfibril orientation, much like how changes in xyloglucan binding compromise cellulose microfibril orientation (Xiao et al., 2016). The possibility that the reduced cellulose content of darx1 affects xylan conformation cannot be excluded, as the cellulose synthesis deficiency alters xylan conformation in Arabidopsis (Simmons et al., 2016). AFM revealed that the organization of rice secondary wall cellulose microfibrils is similar to that in maize (Zea mays; Ding et al., 2012). Hence, abnormalities in xylan conformation and cellulose microfibril orientation in the mutant plants result in compromised secondary wall patterning in sclerenchyma fiber and metaxylem cells, leading to reduced mechanical strength and plant height. Our study offers a mechanistic view for the control of arabinoxylan acetylation and reveals the importance of acetylated xylan side chains on secondary cell-wall architecture. These findings may suggest a strategy for developing elite crops with improved mechanical strength.

METHODS

Plant Materials

All rice plants (Oryza sativa) used in this study are in the Nipponbare cv background and were sown in the experimental fields at the Institute of Genetics and Developmental Biology in Beijing (China) and in Lingshui (Hainan Province, China) in different growing seasons. Usually, ∼24 plants of each genotype were planted in the field with the same intervals for at least 2 y. While the plants matured, they were photographed and subjected to phenotypic analysis.

For generation of the darx1 mutant by CRISPR/Cas9 approach, a coding sequence (734 to 756 bp) was chosen as a target sequence and cloned into the binary plasmid (pYLCRISPR/Cas9 Pubi-MH) as described in Naito et al. (2015) and Ma et al. (2016) using the primers shown in Supplemental Table 3. The transgenic plants were generated by Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain EHA105 infection (Zhang et al., 2017) and genotyped. The Tos17 mutant was purchased from the Rice Genome Resource Center (National Institute of Agrobiological Sciences, Japan).

Fractionation of Rice Total Microsomes

Twenty grams of rice internodes were ground and homogenized in a buffer (25 mM of Tris-acetate, 250 mM of Suc, 1 × protease inhibitor, 10% glycerol, and 2 mM of EDTA, pH 7.5). After centrifuging at 10,000g for 15 min, the supernatants were further ultracentrifuged at 100,000g for 2 h at 4°C to collect total microsomes. The pellets were suspended in a buffer (150 mM of NaCl, 50 mM of Tris-HCl at pH 7.4, 1 mM of EDTA, 2% Triton X-100, and 1 × protease inhibitor). After centrifugation at 10,000g for 15 min at 4°C and filtration through 0.22-μm filters, the protein extracts were applied to a Superdex 200 10/300 GL Column (GE Healthcare) and eluted with Column Buffer (150 mM of NaCl, 50 mM of Tris, and 1 mM of EDTA at pH 7.4) at 0.5 mL/min. For ion chromatography, the solubilized membrane protein samples were loaded onto a HiTrap Q HP column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with Q Column Buffer (20 mM of Tris-HCl at pH 7.6) and a HiTrap SP HP Column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with SP Column Buffer (50 mM of sodium phosphate at pH 6.7; GE Healthcare). Through fractionating with a linear gradient of 0 to 1 M NaCl in the relevant column buffer using the Fast protein liquid chromatography System (ÄKTA pure; GE Healthcare), 100 μL of each eluent fraction was subjected to enzymatic assays and SDS-PAGE. To monitor the experiments, the fractions were blotted on membranes, and the membranes were probed with anti-BS1 antibody at a 1:500 dilution (Zhang et al., 2017).

Protein Mass Spectrometry Analysis

The fractions with obvious arabinosyl and xylosyl deacetylase activity were separated by SDS-PAGE. The proteins ranging from 15 to 130 kD were collected and subjected to an in-gel digestion with trypsin. After extraction with 60% acetonitrile, the resultant peptides were separated on a reverse-phase C18 column and detected with a Linear Ion Trap Mass Spectrometer (Thermo Finnigan). The generated mass spectrum data were analyzed with Proteome Discoverer (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Bioinformatics

A phylogenetic tree of the GELP members was built using neighbor-joining with a protein alignment (Supplemental Data Set) generated by Clustal W in the MEGA6 software (Tamura et al., 2013). One-thousand bootstrap replicates were used to calculate the support for the nodes in the tree. The clades were defined according to the genome-wide GELP family analysis (Volokita et al., 2011; Chepyshko et al., 2012) and shown in different color blocks. The expression profile of DARX1 in various rice tissues was obtained from the online database RiceXPro (http://ricexpro.dna.affrc.go.jp/). DARX1 and BS1 were aligned using Clustal W (Tamura et al., 2013). The three-dimensional model of DARX1 was generated using a hierarchical approach on the Iterative Threading Assembly Refinement server through homology modeling with default settings. The DARX1 catalytic center was visualized using the software CHIMERA (Pettersen et al., 2004).

Expression of DARX1 in Pichia

To express DARX1 protein in Pichia pastoris, the FL coding sequence without the region encoding the transmembrane domain (50 to 456 amino acids) and a Trun version (245 to 456 amino acids) were amplified and inserted in-frame into the pPICZα vector and transformed into Pichia strain SMD1168 by electroporation. Supernatants of the induction culture were supplemented with ammonium sulfate to a concentration of 1 M and loaded onto a HiTrap phenyl FF (HS) Column equilibrated with the Column Buffer (1 M of ammonia sulfate and 50 mM of Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.0) using ÄKTA Pure (GE Healthcare). The trapped recombinant DARX1 proteins were eluted with a diminishing and linear gradient of 1−0 M ammonium sulfate buffer. The purified proteins were desalted with a HiTrap Desalt Column (GE Healthcare) and stored in aliquots.

Enzyme Activity Assays

To analyze the glycosyl acetyl esterase activity, the full acetylated galactoside and arabinoside were prepared as described in Mastihubová et al. (2006). In brief, 2,3,4,6-O-acetyl p-nitrophenyl β-d-galactoside (Ac-NPh-Gal) and 2,3,5-O-acetyl p-nitrophenyl α-l-arabinofuranoside (Ac-NPh-Ara) were generated by acetylating p-nitrophenyl β-d-galactoside and p-nitrophenyl α-l-arabinofuranoside using acetic anhydride, respectively. Another substrate, 2,3,4-O-acetyl methyl β-d-xylopyranoside (Ac-meXyl), was purchased from Carbosynth. After purification, 5 mM of each substrate was incubated with 1 µg of the purified recombinant proteins or 100 μL of the above-fractionated microsomes in the reaction buffer (50 mM of Tris-HCl, pH 7.0) at 37°C for 2 h, respectively. The released acetates were examined using an Acetate Kinase Format Kit (Megazyme) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The kinetics of FL-DARX1 on Ac-NPh-Ara were determined by quantification of the quantities of acetic acids released from a gradient of substrate amounts.

To ascertain the reaction products of Ac-NPh-Ara after incubation with DARX1, the reaction products were loaded onto a 6530 Accurate-Mass Quadrupole Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometer (Agilent Technologies) equipped with an electrospray ionization source. The data were acquired using positive electrospray ionization mode with capillary voltage 3500 V and fragmentor voltage 175 V in mass range of 50 to 600 m/z and analyzed using the MassHunter Qualitative Software package (version B.07.00; Agilent Technologies). To determine the regiospecificity of DARX1, 1 μg of the purified recombinant DARX1 was incubated with 5 mM Ac-NPh-Ara in buffer (50 mM of ammonium acetate, pH 6.0) at 37°C for 3 h. After filtration with a 10-kD Ultra-Filtration Column (Omega), the products were determined by proton and TOCSY NMR spectroscopy.

To determine the DARX1 activity on native substrates, acetyl–xylan extracted from darx1-1 was digested with xylanase M6 (Megazyme) to generate the xylooligosaccharide mixture. Approximately 50 μg of the purified DARX1 recombinant proteins was incubated with xylooligosaccharides (1 mg mL−1) in the buffer (50 mM of Tris, pH 7.0) at 37°C for 16 h. After boiling for 15 min to inactivate the enzymes, the products were examined by HSQC NMR spectroscopy. NMR spectra were acquired at 298 K with a gradient 5-mm 1H/13C/15N triple resonance cold probe as described in Zhang et al. (2017). The assays in the absence of the purified DARX1 were used as negative controls. At least three independent experiments were conducted in all these enzymatic assays.

Transcriptome and RNA Gel Blotting

For the genome-wide gene expression analysis, the young internodes were collected from Nipponbare for mRNA isolation. Library construction and sequencing were performed by Berry Genomics. The clean pair-ended reads were aligned to the Rice Genome version 7 (http://rice.plantbiology.msu.edu/) using the software TopHat2 (https://ccb.jhu.edu/software/tophat/index.shtml). For RNA gel blotting, 20 μg of total RNA was separated by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and transferred onto a positively charged nylon membrane. A specific probe (913 to 1,212 bp) was amplified using primers shown in Supplemental Table 3 and labeled with [32P]-dCTP (PerkinElmer) to detect DARX1 transcripts.

Cell-Wall Compositional Analysis

Alcohol-insoluble cell-wall residues (AIR) were prepared by pooling the mature second internodes of ∼20 mutant and wild-type plants and subject to composition analyses (Zhang et al., 2017). The crystalline cellulose content was analyzed by hydrolyzing the remains of trifluoroacetic acid treatment with Updegraff reagent (acetic acid/nitric acid/water, 8:1:2 v/v) at 100°C for 30 min and quantified by the anthrone method. To determine the content of acetyl esters, 1 mg of destarched AIRs were saponified by incubating with 100 μL of 1 M sodium hydroxide for 1 h at 28°C and then neutralized with 100 μL of 1 M hydrogen chloride. The released acetic acids were immediately quantified according to the instruction of Acetate Kinase Format Kit.

To extract pectin from cell-wall residues, ∼6 mg destarched AIR was incubated with 2 U of endopolygalacturonase M2 (Megazyme) and 0.04 U of pectin methyl esterase (Sigma-Aldrich) in 50 mM of ammonium formate, pH 4.5 at 37°C overnight. The pectin-rich supernatants were collected by centrifugation at 3220g for 10 min and the remnants were considered as pectin-free samples. To isolate the acetyl–xylan, ∼400 mg of destarched AIR was treated with 1% ammonium oxalate to remove pectin. After incubation in 11% peracetic acid solution at 85°C for 30 min, the pellets were extracted twice in DMSO at 70°C overnight. The acetyl–xylan was pelleted with 5 volumes of ethanol/methanol/water solution (7:2:1, pH 3.0) at 4°C for 3 d. After lyophilization, 1 mg of acetyl–xylan was subjected to the acetate content analysis.

To examine the arabinosyl substitution pattern in arabinoxylan, the alkali-extracted xylans from wild-type and darx1 plants were digested with xylanase (Zhang et al., 2017) and then subjected to DNA sequencer-assisted saccharide analysis in high throughput as described in Li et al. (2013), but with minor modifications. Briefly, xylans were extracted from AIR residues with 4 M of NaOH and precipitated with 5 volumes of ethanol/methanol/water solution (7:2:1, pH 3.0). After lyophilization, 1 mg of xylan preparation was digested with 16 U xylanase M6 (Megazyme) in 200 μL of sodium acetate buffer (pH 6.0) for 16 h. The digestion containing ∼10 nmol oligosaccharides was dried and labeled with 1 mM of 9-aminopyrene-1,4,6-trisulfonic acid and 5 mM of NaCNBH3 at 37°C for 6 h. The labeled oligosaccharides were diluted to ∼1 pmol and detected by a model no. 3730xl 96-Sample DNA Sequencer (ABI). A xylooligosaccharide ladder (Xyl to xylohexaose; Megazyme) was used as the molecular-size standard. The abundance of each oligosaccharide was quantified using peak analyzer in the software Origin 9 (OriginLab). All experiments described in this section were performed at least three times.

NMR Analyses

The solution-state NMR spectroscopy analyses were performed on a model no. DD2 600-MHz NMR spectrometer (Agilent). The proton and 2D-NMR spectra were acquired at 298 K with a gradient 5-mm 1H/13C/15N triple resonance cold probe as described in Zhang et al. (2017). For HSQC analysis, 20 mg of the isolated acetyl–xylans from wild type and mutant AIR was dissolved in 0.6 mL of deuterated DMSO-d6 (99.9%; Sigma-Aldrich). The standard pulse sequence “gHSQCAD” was used to determine the one-bond 13C-1H correlation in samples. The 1H-13C HSQC spectra were collected using a spectrum width of 10 ppm in F2 (1H) dimension and 200 ppm in F1 (13C) dimension. The 2,048 × 512 (F2 × F1) complex data points were collected with receiver gain set to 30; 64 scans per FID were accumulated with an interscan delay (“d1”) of 1 s. For TOCSY analysis, the experiments were conducted using the standard pulse sequence with a 100-ms spin lock period. HMBC spectra were recorded using the standard gHMBCAD pulse sequence at 298 K temperature. NOESY spectra were recorded at mixing times of 200 ms using the standard NOESY pulse sequence. These spectra were calibrated using the DMSO solvent peak (dC 39.5 ppm and dH 2.49 ppm). All NMR data analysis was conducted with the software MestReNova 10.0.2. The NMR analyses were performed with three biological replicates of the pooled internodes.

Solid-state magic-angle spinning (MAS) NMR experiments were performed on a 600-MHz/395-GHz MAS-DNP spectrometer (Bruker; Dubroca et al., 2018) as described in Takahashi et al. (2012) and Kang et al. (2019). Briefly, ∼60 mg slices from two intact and unlabeled internodes of wild-type and darx1-1 plants were placed into 150 μL of AMUPol solution in D2O. The samples were dried under vacuum for 10 h and combined with 5 μL of D2O to provide moisture. They were then subjected to DNP measurements under 10-kHz MAS frequency after being packed into 3.2-mm thin-wall ZrO2 rotors. The microwave irradiation power was ∼12 W. A 3.2-mm MAS probe was used, and the typical radiofrequency field strengths were 100 kHz for 1H decoupling, 62.5 kHz for 1H and 13C cross polarization, and 40 kHz for 13C dipolar recoupling using the SPC5 sequence. The temperature was ∼104 K when the microwave was on and ∼98 K when the microwave was off. The DNP buildup time was 3.4 s and 2.2 s for the wild-type and darx1-1 samples, respectively. The recycle delays were 1.3 times of the DNP buildup time for each sample. The sensitivity enhancement factors (εon/off) were 21 and 20 for the wild-type and darx1-1 samples, respectively. The 2D 13C-13C INADEQUATE spectra were recorded for 17∼37 h with the spectral width of 60 ppm for the indirect dimension (double-quantum chemical shift) and 331 ppm for the direct dimension. The 13C chemical shift was externally referenced to the adamantane CH2 signal (38.48 ppm) on the Tetramethylsilane scale. All spectra were analyzed using the software Topspin (version 3.2 or 3.5; Bruker).

Subcellular Localization

The full coding sequence for DARX1 was cloned and in-frame–fused with that for GFP in the pCAMBIA1300 vector. The resulting construct was cotransformed into tobacco leaves with a construct for expression of the Golgi marker Man49-mCherry. The fluorescence signals were recorded with a confocal laser scanning microscope (Axio Imager Z2; Zeiss). To analyze the DARX1-resident profile in vivo, anti-DARX1 polyclonal antibodies were produced in mice. Briefly, the polypeptide encompassing amino acids 305 to 338 of DARX1 was fused with a carrier protein glutathione S-transferase and expressed in Escherichia coli. The column-purified recombinant protein was used as an antigen in mice. The generated serum harboring DARX1 polyclonal antibodies was used for immunoblotting and immunolabeling. One-week–old wild-type seedlings were homogenized in a buffer (250 mM of sorbitol, 50 mM of Tris-acetate at pH 7.5, 1 mM of EGTA at pH 7.5, 2 mM of dithiothreitol, 1 × protease inhibitor, 2% (w/v) polyvinylpyrrolidone, and 4 mM of EDTA). After centrifugation at 12,000g for 10 min, the supernatant was further ultracentrifuged at 100,000g for 1 h at 4°C. The pellet was suspended and fractionated in 20% to 55% Suc gradient solution. The fractionations were separated by SDS–PAGE and probed with the anti-DARX1 antibody at a 1:500 dilution and organelle marker antibodies against BS1 (using a Golgi marker from Agrisera; Zhang et al., 2017), BiP (AS09 481, an endoplasmic reticulum marker; Agrisera) and PIP1s (AS09 505, a plasma membrane marker; Agrisera) at a 1:1,000 dilution, respectively.

For immunogold labeling, 3-d-old root tips of wild-type plants were cryofixed by high-pressure freezing (HPM100; Leica) and freeze-substituted with 2% uranyl acetate in acetone at −90°C for 48 h using AFS2 (Leica). The samples were embedded in Lowicryl HM20 Resin (Electron Microscopy Sciences). The 80-nm–thick sections were cut with a microtome (EM UC6; Leica) and incubated with anti-DARX1 antibody at 1:300 dilution. Secondary antibody, 15 nm of colloidal gold-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Abcam), was applied to the sections at 1:20 dilution. The images were acquired using a transmission electron microscope (model no. HT7700; Hitachi) equipped with a charge-coupled device camera (model no. 832; Gatan).

Scanning Electron Microscopy Analysis

At least five mature second internodes from different plants were collected from wild-type and darx1-1 plants and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich). The samples were prepared by longitudinally cutting along the metaxylem of internodes under stereoscope and by cross sectioning the internodes. After critical-point drying and spraying with gold particles, the secondary wall patterns in metaxylem and secondary wall thickness of sclerenchyma fiber cells were observed with a scanning electron microscope (model no. S-3000N; Hitachi). The software CellProfiler 2.1 (Broad Institute) was used to calculate pit areas in metaxylem cells.

Examination of the Breaking Force

The mature second internodes of at least 20 plants of wild type and darx1-1 were cut into segments of equal length and immediately used for measurement. The crushing force to break the internodes was measured with a digital force tester (model no. 5848 Microtester; Instron).

AFM

To probe microfibrils in cell walls, the mature second rice internodes were sliced and treated in 11% peracetic acid solution at 85°C for 3 h to remove lignin. After rinsing, the samples were imaged by a MultiMode Scanning Probe Microscope (MM-SPM; Bruker) with an advanced NanoScope V Controller (Veeco) operating in air (Xu et al., 2018). All images were scanned in 1-μm scale at 512 × 512 pixels using the ScanAsyst-Air probe (Bruker). The images were flattened to remove bow or tilt and exported in the TIFF format using the software Nanoscope Analysis (version 1.8; Bruker). At least five different metaxylem cells from one plant were scanned, and at least three different plants were used. Three representative images of three cells of three individual plants were selected for quantification. To quantify macrofibril/microfibril orientation, AFM images were analyzed using the software ImageJ (National Institutes of Health) with the plugin shape index map and then converted to “mask.” The macrofibrils/microfibrils were automatically detected by the software SOAX (3.6.1; https://omictools.com/soax-tool) as “snakes” (segments) using a snake point spacing of 1 pixel and a minimum snake length of 20 pixels. Microfibril orientation was evaluated by calculating the orientation of 60,000 snakes after snake cuts at junctions. The data are shown as frequency percentage in a histogram.

Accession Numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in the GenBank/EMBL data libraries under accession numbers XM_015782069.2 for the identified DARX1.

Supplemental Data

Supplemental Figure 1. Screening arabinoxylan deacetylases in rice.

Supplemental Figure 2. Determining the coding sequence of DARX1.

Supplemental Figure 3. Genetic verification of DARX1.

Supplemental Figure 4. darx1 Arabinoxylan has altered acetylation pattern.

Supplemental Figure 5. NMR correlation spectrum analyses of acetyl–xylan in darx1.

Supplemental Figure 6. Arabinosyl substitution pattern is unchanged in darx1.

Supplemental Figure 7. Enzymatic activity assays of DARX1.

Supplemental Figure 8. Quantification of macrofibril diameter in situ by AFM.

Supplemental Table 1. Detected GELP proteins in LC–MS analyses.

Supplemental Table 2. Chemical shifts (ppm) assignment for arabinosyl residues identified by 2D-NMR analyses.

Supplemental Table 3. Primers used in this study.

Supplemental Data Set. Text file of the alignment used for the phylogenetic analysis shown in Figure 1B.

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Yaoguang Liu for kindly providing the gRNA expression cassettes and the binary CRISPR/Cas9 vectors, Dr. Xue-Hui Liu and Shanshan Zang for help with the solution-state NMR analyses, and Dr. Junli Xu and Prof. Suojiang Zhang for assistance with the AFM analysis. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grants 31530051, 31571247, and 91735303), the Youth Innovation Promotion Association, Chinese Academy of Sciences (2016094), the U.S. National Science Foundation (grant NSF/OIA-1833040), and the State Key Laboratory of Plant Genomics. The DNP work was performed at the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory, which was supported by the U.S. National Science Foundation (grants NSF/DMR-1644779 and NSF/CHE-1229170), the State of Florida, and the U.S. National Institutes of Health (grant NIH-S10-OD018519).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Y.Z., B.Z., and L.Z. designed experiments; B.Z. and L.Z. analyzed the data; L.Z. and C.G. performed biochemical and cell-wall composition analyses; T.W. and F.M.V. performed DNP analysis; L.Z. and S.C. conducted AFM analysis; L.T. and D.Z. performed protein localization experiments; S.W. conducted RNA gel blotting; Z.X. and X.L. performed plant transformation and filed experiments; Y.Z. and B.Z. wrote the article; Y.Z. supervised the project.

References

- Bacic A., Harris P., Stone B. (1988). Structure and function of plant cell walls. In The Biochemistry of Plants, Priess J., ed (New York, London, San Francisco: Academic Press; ), pp. 297–371. [Google Scholar]

- Bosch M., Hepler P.K. (2005). Pectin methylesterases and pectin dynamics in pollen tubes. Plant Cell 17: 3219–3226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton R.A., Gidley M.J., Fincher G.B. (2010). Heterogeneity in the chemistry, structure and function of plant cell walls. Nat. Chem. Biol. 6: 724–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busse-Wicher M., Gomes T.C., Tryfona T., Nikolovski N., Stott K., Grantham N.J., Bolam D.N., Skaf M.S., Dupree P. (2014). The pattern of xylan acetylation suggests xylan may interact with cellulose microfibrils as a twofold helical screw in the secondary plant cell wall of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 79: 492–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpita N.C., Gibeaut D.M. (1993). Structural models of primary cell walls in flowering plants: Consistency of molecular structure with the physical properties of the walls during growth. Plant J. 3: 1–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X.Y., Kim S.T., Cho W.K., Rim Y., Kim S., Kim S.W., Kang K.Y., Park Z.Y., Kim J.Y. (2009). Proteomics of weakly bound cell wall proteins in rice calli. J. Plant Physiol. 166: 675–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chepyshko H., Lai C.P., Huang L.M., Liu J.H., Shaw J.F. (2012). Multifunctionality and diversity of GDSL esterase/lipase gene family in rice (Oryza sativa L. japonica) genome: New insights from bioinformatics analysis. BMC Genomics 13: 309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiniquy D., et al. (2012). XAX1 from glycosyltransferase family 61 mediates xylosyltransfer to rice xylan. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109: 17117–17122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho W.K., Chen X.Y., Chu H., Rim Y., Kim S., Kim S.T., Kim S.W., Park Z.Y., Kim J.Y. (2009). Proteomic analysis of the secretome of rice calli. Physiol. Plant. 135: 331–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de O Buanafina M.M. (2009). Feruloylation in grasses: Current and future perspectives. Mol. Plant 2: 861–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding S.Y., Liu Y.S., Zeng Y., Himmel M.E., Baker J.O., Bayer E.A. (2012). How does plant cell wall nanoscale architecture correlate with enzymatic digestibility? Science 338: 1055–1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubroca T., et al. (2018). A quasi-optical and corrugated waveguide microwave transmission system for simultaneous dynamic nuclear polarization NMR on two separate 14.1 T spectrometers. J. Magn. Reson. 289: 35–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrokhi N., Burton R.A., Brownfield L., Hrmova M., Wilson S.M., Bacic A., Fincher G.B. (2006). Plant cell wall biosynthesis: Genetic, biochemical and functional genomics approaches to the identification of key genes. Plant Biotechnol. J. 4: 145–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y., He C., Zhang D., Liu X., Xu Z., Tian Y., Liu X.H., Zang S., Pauly M., Zhou Y., Zhang B. (2017). Two trichome birefringence-like proteins mediate xylan acetylation, which is essential for leaf blight resistance in rice. Plant Physiol. 173: 470–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gille S., Pauly M. (2012). O-acetylation of plant cell wall polysaccharides. Front. Plant Sci. 3: 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gille S., de Souza A., Xiong G., Benz M., Cheng K., Schultink A., Reca I.B., Pauly M. (2011). O-acetylation of Arabidopsis hemicellulose xyloglucan requires AXY4 or AXY4L, proteins with a TBL and DUF231 domain. Plant Cell 23: 4041–4053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gou J.Y., Miller L.M., Hou G., Yu X.H., Chen X.Y., Liu C.J. (2012). Acetylesterase-mediated deacetylation of pectin impairs cell elongation, pollen germination, and plant reproduction. Plant Cell 24: 50–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grantham N.J., Wurman-Rodrich J., Terrett O.M., Lyczakowski J.J., Stott K., Iuga D., Simmons T.J., Durand-Tardif M., Brown S.P., Dupree R., Busse-Wicher M., Dupree P. (2017). An even pattern of xylan substitution is critical for interaction with cellulose in plant cell walls. Nat. Plants 3: 859–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii T. (1991). Acetylation at O-2 of arabinofuranose residues in feruloylated arabinoxylan from bamboo shoot cell-walls. Phytochemistry 30: 2317–2320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janbon G., Himmelreich U., Moyrand F., Improvisi L., Dromer F. (2001). Cas1p is a membrane protein necessary for the O-acetylation of the Cryptococcus neoformans capsular polysaccharide. Mol. Microbiol. 42: 453–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang X., Kirui A., Dickwella Widanage M.C., Mentink-Vigier F., Cosgrove D.J., Wang T. (2019). Lignin-polysaccharide interactions in plant secondary cell walls revealed by solid-state NMR. Nat. Commun. 10: 347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiefer L., York W., Darvill A., Albersheim P. (1989). Xyloglucan isolated from suspension-cultured sycamore cell-walls is O-acetylated. Phytochemistry 28: 2105–2107. [Google Scholar]

- Lee C., Teng Q., Zhong R., Ye Z.H. (2011). The four Arabidopsis reduced wall acetylation genes are expressed in secondary wall-containing cells and required for the acetylation of xylan. Plant Cell Physiol. 52: 1289–1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Jackson P., Rubtsov D.V., Faria-Blanc N., Mortimer J.C., Turner S.R., Krogh K.B., Johansen K.S., Dupree P. (2013). Development and application of a high throughput carbohydrate profiling technique for analyzing plant cell wall polysaccharides and carbohydrate active enzymes. Biotechnol. Biofuels 6: 94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loqué D., Scheller H.V., Pauly M. (2015). Engineering of plant cell walls for enhanced biofuel production. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 25: 151–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X., Zhu Q., Chen Y., Liu Y.G. (2016). CRISPR/Cas9 platforms for genome editing in plants: Developments and applications. Mol. Plant 9: 961–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manabe Y., et al. (2011). Loss-of-function mutation of REDUCED WALL ACETYLATION2 in Arabidopsis leads to reduced cell wall acetylation and increased resistance to Botrytis cinerea. Plant Physiol. 155: 1068–1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastihubová M., Szemesová J., Biely P. (2006). The acetates of p-nitrophenyl α-L-arabinofuranoside—Regioselective preparation by action of lipases. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 14: 1805–1810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naito Y., Hino K., Bono H., Ui-Tei K. (2015). CRISPRdirect: Software for designing CRISPR/Cas guide RNA with reduced off-target sites. Bioinformatics 31: 1120–1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauly M., Ramírez V. (2018). New insights into wall polysaccharide O-acetylation. Front. Plant Sci. 9: 1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersen E.F., Goddard T.D., Huang C.C., Couch G.S., Greenblatt D.M., Meng E.C., Ferrin T.E. (2004). UCSF Chimera—A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25: 1605–1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rennie E.A., Scheller H.V. (2014). Xylan biosynthesis. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 26: 100–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheller H.V. (2017). Plant cell wall: Never too much acetate. Nat. Plants 3: 17024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultink A., Naylor D., Dama M., Pauly M. (2015). The role of the plant-specific ALTERED XYLOGLUCAN9 protein in Arabidopsis cell wall polysaccharide O-acetylation. Plant Physiol. 167: 1271–1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons T.J., Mortimer J.C., Bernardinelli O.D., Pöppler A.C., Brown S.P., deAzevedo E.R., Dupree R., Dupree P. (2016). Folding of xylan onto cellulose fibrils in plant cell walls revealed by solid-state NMR. Nat. Commun. 7: 13902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith P.J., Wang H.T., York W.S., Peña M.J., Urbanowicz B.R. (2017). Designer biomass for next-generation biorefineries: Leveraging recent insights into xylan structure and biosynthesis. Biotechnol. Biofuels 10: 286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somerville C., Bauer S., Brininstool G., Facette M., Hamann T., Milne J., Osborne E., Paredez A., Persson S., Raab T., Vorwerk S., Youngs H. (2004). Toward a systems approach to understanding plant cell walls. Science 306: 2206–2211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi H., Lee D., Dubois L., Bardet M., Hediger S., De Paëpe G. (2012). Rapid natural-abundance 2D 13C-13C correlation spectroscopy using dynamic nuclear polarization enhanced solid-state NMR and matrix-free sample preparation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 51: 11766–11769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K., Stecher G., Peterson D., Filipski A., Kumar S. (2013). MEGA6: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30: 2725–2729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teleman A., Tenkanen M., Jacobs A., Dahlman O. (2002). Characterization of O-acetyl-(4-O-methylglucurono)xylan isolated from birch and beech. Carbohydr. Res. 337: 373–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel J.P., Raab T.K., Somerville C.R., Somerville S.C. (2004). Mutations in PMR5 result in powdery mildew resistance and altered cell wall composition. Plant J. 40: 968–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volokita M., Rosilio-Brami T., Rivkin N., Zik M. (2011). Combining comparative sequence and genomic data to ascertain phylogenetic relationships and explore the evolution of the large GDSL-lipase family in land plants. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28: 551–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wende G., Fry S.C. (1997). O-feruloylated, O-acetylated oligosaccharides as side-chains of grass xylans. Phytochemistry 44: 1011–1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao C., Zhang T., Zheng Y., Cosgrove D.J., Anderson C.T. (2016). Xyloglucan deficiency disrupts microtubule stability and cellulose biosynthesis in Arabidopsis, altering cell growth and morphogenesis. Plant Physiol. 170: 234–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xin Z., Browse J. (1998). Eskimo1 mutants of Arabidopsis are constitutively freezing-tolerant. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95: 7799–7804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong G., Cheng K., Pauly M. (2013). Xylan o-acetylation impacts xylem development and enzymatic recalcitrance as indicated by the Arabidopsis mutant tbl29. Mol. Plant 6: 1373–1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J., Zhang B., Lu X., Zhou Y., Fang J., Li Y., Zhang S. (2018). Nanoscale observation of microfibril swelling and dissolution in ionic liquids. ACS Sustain. Chem.& Eng. 6: 909–917. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Y., Teng Q., Zhong R., Ye Z.-H. (2016). Roles of Arabidopsis TBL34 and TBL35 in xylan acetylation and plant growth. Plant Sci. 243: 120–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B., Zhang L., Li F., Zhang D., Liu X., Wang H., Xu Z., Chu C., Zhou Y. (2017). Control of secondary cell wall patterning involves xylan deacetylation by a GDSL esterase. Nat. Plants 3: 17017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong R., Cui D., Ye Z.H. (2017). Regiospecific acetylation of xylan is mediated by a group of DUF231-containing O-acetyltransferases. Plant Cell Physiol. 58: 2126–2138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X.F., Sun Y., Zhang B.C., Mansoori N., Wan J.X., Liu Y., Wang Z.W., Shi Y.Z., Zhou Y.H., Zheng S.J. (2014). TRICHOME BIREFRINGENCE-LIKE27 affects aluminum sensitivity by modulating the O-acetylation of xyloglucan and aluminum-binding capacity in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 166: 181–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]