Abstract

CD4+ effector/memory T cells (Tem) represent a leading edge of the adaptive immune system responsible for protecting the body from infection, cancer, and other damaging processes. However, a subset of Tem cells with low expression of CD45Rb (RbLoTem) has been shown to suppress inflammation despite their effector surface phenotype and the lack of FoxP3 expression, the canonical transcription factor found in most regulatory T cells. In this report, we show that RbLoTem cells can suppress inflammation by influencing Treg behavior. Co-culturing activated RbLoTem and Tregs induced high expression of IL-10 in vitro, and conditioned media from RbLoTem cells induced IL-10 expression in FoxP3+ Tregs in vitro and in vivo, indicating that RbLoTem cells communicate with Tregs in a cell-contact independent fashion. Transcriptomic and multi-analyte Luminex data identified both IL-2 and IL-4 as potential mediators of RbLoTem-Treg communication, and antibody-mediated neutralization of either IL-4 or CD124 (IL-4Rα) prevented IL-10 induction in Tregs. Moreover, isolated Tregs cultured with recombinant IL-2 and IL-4 strongly induced IL-10 production. Using house dust mite (HDM)-induced airway inflammation as a model, we confirmed that the in vivo suppressive activity of RbLoTem cells was lost in IL-4-ablated RbLoTem cells. These data support a model in which RbLoTem cells communicate with Tregs using a combination of IL-2 and IL-4 to induce robust expression of IL-10 and suppression of inflammation.

Introduction

Regulatory T cells (Tregs) are critical for the maintenance of immune homeostasis. The most widely recognized and studied subset of Tregs express the transcription factor FoxP3 and can be induced peripherally or develop directly in the thymus [1–3]; however, FoxP3- type 1 regulatory cells (Tr1) are also well-characterized [4, 5]. Another CD4+ T cell subset known to have regulatory/suppressive properties are those lacking FoxP3 while expressing low concentrations of the activation marker CD45Rb (RbLo) at the cell surface. These RbLo T cells inhibit the induction of wasting disease in SCID mice [6], type 1 diabetes [7], a plant antigen-based model of asthma [8], and the formation of adhesions [9]. In agreement with these reports, we recently found that the polysaccharide antigen PSA from Bacteroides fragilis significantly decreased susceptibility to the development of pulmonary inflammation through activation and expansion of CD4+FoxP3-CD45RbLo effector-memory (CD62L-CD44+) T cells (RbLoTem)[10–12].

RbLoTem cells are known to depend upon IL-10 for their protective efficacy [13, 14]. Consistent with this, we found that the suppressive activity of RbLoTem cells required IL-10 in both humans in vitro [15] and mice in vivo [10, 12]. In an in vivo model in which all cells lacked IL-10, the RbLoTem cells failed to protect the animals from pulmonary inflammation [10]. However, reciprocal adoptive transfer experiments in which activated wild type (WT) or IL-10-deficient (IL-10-/-) RbLoTem cells were given to WT or IL-10-/- recipients, we discovered that IL-10 was dispensable in the RbLoTem cells but not in the recipient [12]. Moreover, adoptive transfer of IL-10-/- RbLoTem cells induced IL-10 expression in CD4+FoxP3+ Tregs in the lung [12], suggesting a model in which RbLoTem cells suppress inflammation by the selective induction of IL-10 in FoxP3+ Tregs in vivo through an unknown mechanism.

In this study, we report the discovery of a mechanism by which RbLoTem cells communicate with and drive suppressive activity of FoxP3+ Tregs to regulate inflammation. Consistent with our in vivo studies [12], co-cultured RbLoTem cells induced FoxP3+ Tregs to secrete high concentrations of IL-10 in vitro. Conditioned media from activated RbLoTem cells also induced IL-10 in FoxP3+ Tregs both in vivo and in vitro, demonstrating cell-contact independence in the communication pathway between these cells. Deep sequencing transcriptomics of activated RbLoTem cells versus CD45RbHi T naïve cells identified potential soluble mediators, and antibody-mediated neutralization experiments suggested that both IL-2 and IL-4 were necessary for IL-10 induction in Tregs. Supplementation of Treg media with recombinant IL-2 and IL-4 confirmed this in vitro, while the use of IL-4-deficient RbLoTem cells showed a lack of protective efficacy in a model of pulmonary inflammation when compared to WT cells. These results reveal an intrinsic IL-2 and IL-4-dependent T cell crosstalk network connecting the suppressive capacity of RbLoTem cells with canonical FoxP3+ Tregs, which could potentially be harnessed for the treatment of inflammation-mediated diseases.

Materials and methods

Mice

C57BL/6 (Stock #000664), IL-10-eGFP (B6.129S6-Il10tm1Flv/J, Stock #008379), IL-10-null (B6.129P2-Il10tm1Cgn/J, Stock #002251), FoxP3-RFP (C57BL/6-FoxP3tm1Flv/J), and IL-4-knockout (B6.129P2-Il4tm1Cgn/J) mice, all on the C57BL/6 background, were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). FoxP3-eGFP animals were a kind gift of Drs. Rudensky and Letterio. Mice were fed standard chow (Purina 5010) on a 12-hour light/dark cycle in a specific pathogen free facility. Enrichment and privacy provided in mating cages by ‘love shacks’ (Bio Serv 53352–400). Mouse studies, and all animal housing at Case Western Reserve University were approved by and performed according to the guidelines established by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of CWRU.

Primary splenic T cells

Primary splenocytes were isolated from freshly harvested spleens, and reduced to a single cell suspension by passing them through a sterile 100μM nylon mesh cell strainer (Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH). For splenic T cell enrichment, single cell suspensions were labeled with anti-mouse CD4 magnetic microbeads, or alternatively negatively selected to yield untouched CD4 cells, and positively selected for CD25 by a mouse regulatory T cell isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec, San Diego, CA), and separated with an AutoMACS Pro Separator (Miltenyi Biotec, San Diego, CA), per manufacturer’s instructions.

Pulmonary inflammation and adoptive transfer

HDM model

Mice were challenged with house dust mite antigen (HDM, D. Farinae, GREER, Lenoir, NC) by intranasal delivery of 20μg HDM/dose in PBS on days 0–4 and 7–11 and sacrificed on day 14 [16]. For adoptive transfer, 60,000 RbLoTem cells were harvested by FACS from FoxP3-eGFP reporter mice and i.v. injected on day 6. Animals were anesthetized with 3% isoflurane (Baxter) with an anesthesia system (VetEquip, Livermore, CA) for intranasal administration. Euthanasia, BALf recovery, and lung tissue preparation was performed as previously reported [10, 12]. BALf automated differentials were acquired by a HemaVet 950 Hematology Analyzer.

Flow cytometry and cell sorting

For splenic T cell sorting, magnetic bead-mediated positively selected CD4+ cells were stained with combinations of antibodies (0.5μg/mL per) to CD62L-PE (BioLegend, San Diego, CA) or CD62L-BB515 (BD Bioscience), CD44-APC (BioLegend, San Diego, CA), CD45Rb-APC/Cy7 (BioLegend, San Diego, CA), CD124 (1μg/mL, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), and CD25-BV421 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). For Tregs, FoxP3-RFP reporter signal was used for FACS. Cells were washed twice in MACS buffer (Miltenyi Biotec, San Diego, CA) before sterile cell sorting using a FACSAria (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) with the support of the Cytometry & Imaging Microscopy Core Facility of the Case Comprehensive Cancer Center. Analysis of all FACS data was performed using FlowJo v10 (Tree Star, Inc., Ashland, OR).

Cell culture

After flow sorting, cells were cultured in 96-well plates (Corning, Corning, NY) at 50,000 cells per type per well in advanced RPMI (Gibco/Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) supplemented with 5% Australian-produced heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 55μM β-mercaptoethanol, 100U/mL and 100μg/mL Penicillin/Streptomycin, and 0.2mM L-glutamine (Gibco/Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) at 5% CO2, 37°C. For activating conditions, wells were coated with αCD3ε (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) at 2.5μg/mL in PBS then incubated at 37°C for 4 hours followed by two washes with PBS before receiving cells. For fixation studies, indicated cell types were resuspended in 2% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 10 minutes on ice. Cells were washed twice in PBS before being co-cultured with live CD4+FoxP3+ cells. All co-culture experiments were performed at 1:1 cell ratios, except for the experiments in Fig 1C, which were performed by maintaining constant Tconv cell numbers (50k) and altering the number of Tregs relative to the 50k Tconv, as indicated.

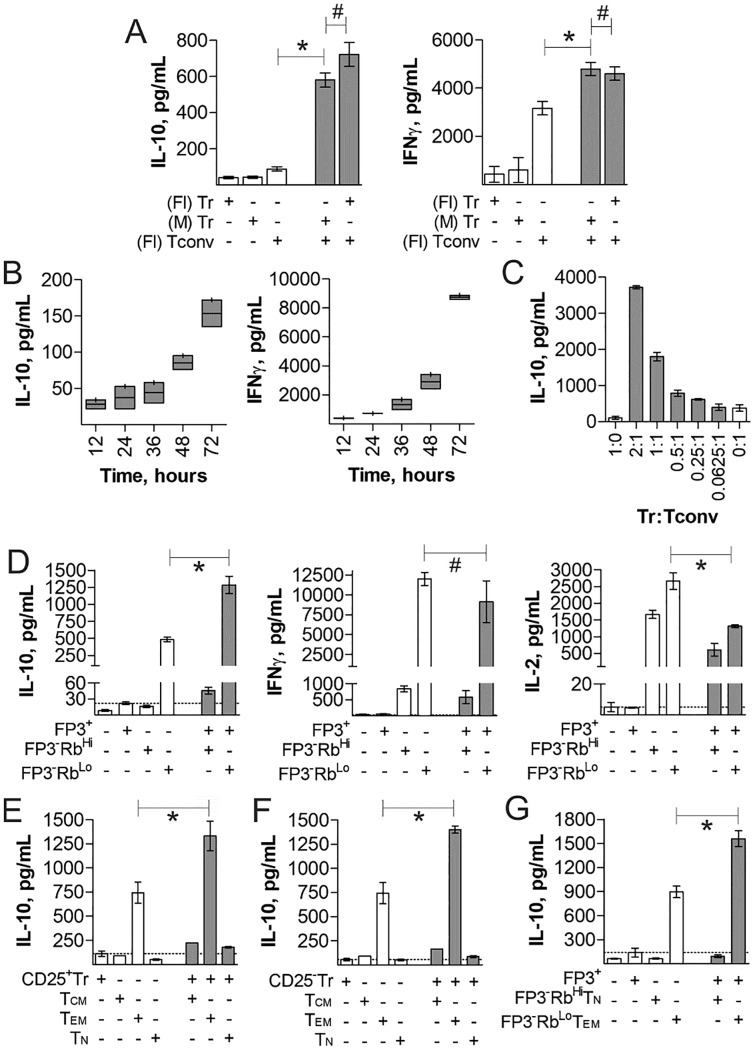

Fig 1. IL-10 production by Tregs is synergistically enhanced by CD4+FoxP3-CD45RbLoCD44+CD62L- T cells.

Tregs and various CD4+ T cell subsets were cultured in vitro with plate-bound anti-CD3ε antibody for 3 days, unless otherwise specified, to measure their cytokine responses by ELISA. (A) Comparison of mono- and co-cultures of magnetic bead purified (M) CD4+ Tconv and CD4+CD25+ Tr cells vs. flow sorted (Fl) CD4+CD25+ Tr cells. (B) Time course of cytokine production from co-cultures of flow-sorted Tconv and CD25+ Tregs. (C) Co-cultures of flow-sorted 50k Tconv and varied Tregs at indicated ratios. (D) 1:1 Cultures of flow sorted CD4+FoxP3+ Tregs and CD4+FoxP3-CD45RbHi/Lo cells, showing IL-10, IFNγ, and IL-2 production by ELISA. (E) 1:1 cultures of CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Tregs and CD4+CD25-FoxP3-CD62L+CD44+ (Tcm), CD4+CD25-FoxP3-CD62L-CD44+ (Tem), and CD4+CD25-FoxP3-CD62L+CD44- (Tn) cells. (F) 1:1 cultures of CD4+CD25-FoxP3+ Tregs and Tcm, Tem, or Tn cells. (G) 1:1 cultures of CD4+FoxP3+ Tregs and CD4+FoxP3-CD45RbLoCD62L-CD44+ (RbLoTem) or CD4+FoxP3- CD45RbHiCD62L+CD44- (RbHiTn) cells. * = p<0.05; # = p>0.05. P value calculated from Student’s T-Test. Error bars show mean with SEM. For A-B and D-F, n = 3 experiments. For C, n = 6 experiments. For G, n = 4 experiments.

ELISA, blocking, supplementation and Luminex

Cytokine levels were analyzed by standard sandwich ELISA performed as per manufacturer’s instructions (BioLegend, San Diego, CA), modified to utilize europium-conjugated streptavidin (Perkin-Elmer), and detected with a Victor V3 plate reader (Perkin Elmer, San Jose, CA). Blocking experiments utilized antibodies to IFNγ (10μg/mL, BioLegend, San Diego, CA), IL-21 (10μg/mL, eBioscience, San Diego, CA), IL-22 (10μg/mL, eBioscience), CSF2 (10μg/mL, eBioscience), IL-9 (1μg/mL, eBioscience), IL-13 (2μg/mL, eBioscience), IL-4 (1μg/mL, eBioscience), IL-24 (2μg/mL, eBioscience), IL-3 (1μg/mL, eBioscience), Neuropilin-1 (1μg/mL, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), CD124 (1μg/mL, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), and corresponding isotype controls IgG1 and IgG2a (BioLegend, San Diego, CA). For CD124 blocking experiments, indicated cell types were incubated with 1μg/mL αCD124 at 4°C for 15 minutes, washed twice with PBS, then combined into co-culture. Supplementation assays were performed with recombinant mouse IL-2 and IL-4 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) at the indicated concentrations. For Luminex assays, media from indicated cultured populations were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and sent to Eve Technologies (Calgary, Ontario, Canada) for mouse 32-plex and TGFβ 3-plex analysis.

RNAseq and analysis

For RNA quantitation, CD4+FoxP3+ (Treg), CD4+FoxP3-CD45RbHiCD62HiCD44Lo (RbHiTn), CD4+FoxP3-CD45RbLoCD62LLoCD44Hi (RbLoTem) cells were flow sorted as above, pelleted and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. RNA extraction and RNAseq was performed at Ambry Genetics. Initial processing of the data was performed by using the trimmomatic [17] program to trim the poor quality reads, and fastQC to investigate read quality. TopHat [18] was used to align the reads to the “mm10” genome guided by the Gencode vm4 [19] annotations. To count the number of reads aligning to each feature in Gencode vm4, we used htseq-count [20]. RPKM values were calculated in R, and the differential expression analysis between “Hi” and “Lo” samples was performed using the negative binomial test implemented in DEseq2 [21].

Histology and microscopy

Tissues were blocked, sectioned, and stained with H&E by the Case Western Reserve University Tissue Procurement and Histology Core Facility, and at AML Laboratories, Inc. (Jacksonville, FL). Unstained sections were stained with rat-anti-EpCAM-AF488 (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) or rat-anti-EpCAM-AF594 (BioLegend, San Diego, CA) at 6μg/mL, and rabbit-anti-myeloperoxidase (1:100, Abcam, Cambridge, MA) then either anti-rabbit-APC (Thermo/Fisher, Waltham, MA) or anti-rabbit-AF488 (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) at 1:1000. Confocal analysis and imaging was performed on a Leica SP5 confocal microscope; H&E images were acquired with a Leica DM IL LED.

Clinical scoring

Scoring of H&E-stained lung tissues was performed by Dr. Cobb in a blinded fashion based on the rubric shown in Table 1, with a maximum score of 9 characterized by severe airway epithelial hyperplasia and large numbers of infiltrating cells disseminated throughout the tissue.

Table 1. Lung inflammation clinical score rubric.

| Parameter | Score | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Hyperplasia | 0 | None |

| 1 | Not more than 2 bronchi with mild to moderate epithelial hyperplasia | |

| 2 | Many bronchi with moderate hyperplasia | |

| 3 | Most bronchi with moderate to severe hyperplasia | |

| Infiltration | 0 | None |

| 1 | Small numbers of infiltrating immune cells (undifferentiated) | |

| 2 | Moderate numbers of infiltrating immune cells | |

| 3 | High numbers of infiltrating immune cells | |

| Localization | 0 | Infiltrating cells limited to one or two bronchi |

| 1 | Infiltrating cells seen around a plurality of bronchi | |

| 2 | Infiltrating cells seen around all bronchi and some dissemination in the alveolar space | |

| 3 | Infiltrating cells throughout the tissue |

H&E stained lung sections were scored for epithelial cell hyperplasia, infiltration of immune cells, and localization of immune cells on a zero to 3 scale for each parameter. Final clinical scores were the sum of each parameter for each tissue.

Data analyses

All data are represented by mean ± SEM from at least 3 independent experiments, with the exception of the RNAseq, which was performed in duplicate for each subset. Pulmonary inflammation data sets include a minimum of four, but more commonly six animals per group per experiment. Data and statistical measurements were generated with GraphPad Prism (v5.0). For comparisons between two groups, Student’s t-test was used; comparisons between multiple groups utilized analysis of variance.

Results

RbLoTem cells induce IL-10 in FoxP3+ Tregs

Our previous studies revealed that conventional CD4+ T cells activated by the polysaccharide PSA from the capsule of Bacteroides fragilis can influence FoxP3+ Tregs to produce IL-10 through an unknown pathway [10, 12]. Here, we investigated the ability of CD4+ T cells to influence Tregs and their production of IL-10 in the absence of PSA. CD4+CD25+ Tregs and CD4+CD25- Tconv cells were isolated from WT mice using either magnetic beads (M) or sterile flow sorting (Fl), and stimulated with anti-CD3ε antibody alone or in co-culture for different amounts of time. Despite having not been previously exposed to PSA, we found that when cultured together, Tregs and Tconv cells synergistically produced IL-10 at 72 hours, while IFNγ production was simply additive (Fig 1A and 1B). Moreover, variations of the ratio of Treg:Tconv demonstrates that the amount of IL-10 is proportional to the number of Tregs, not the number of Tconv cells (Fig 1C).

PSA exposure expands a CD4+FoxP3-CD45RbLo T cell population in both humans [15] and mice [10, 11], and this population was found to induce IL-10 production by lung-localized FoxP3+ Tregs [12]. We therefore isolated CD4+FoxP3-CD45RbLo (FoxP3-RbLo), CD4+FoxP3-CD45RbHi (FoxP3-RbHi), and CD4+FoxP3+ Tregs (FoxP3+) from PSA-naïve FoxP3-eGFP reporter mice and stimulated them as before with anti-CD3ε. We found that while the FoxP3-RbLo subset produced some IL-10 alone, the IL-10 concentration was increased over 2 fold in co-culture with FoxP3+ cells on day 3 (Fig 1D). IFNγ trended down but was not significant while IL-2 was significantly reduced in co-culture (Fig 1D). Importantly, the FoxP3-RbHi population, despite their ability to produce IL-2, did not induce significant IL-10 secretion in vitro.

To further clarify the identification of T cells responsible for communicating with FoxP3+ Tregs, CD4+FoxP3+ Tregs with or without CD25, CD4+ naïve (Tn; CD62L+CD44-), effector memory (Tem; CD62L-CD44+) and central memory (Tcm; CD62L+CD44+) T cells from FoxP3-eGFP mice were isolated and stimulated as before in various combinations. Tem cells were the only subset to produce IL-10 alone, and the only ones to synergistically induce IL-10 in co-culture with Tregs (Fig 1E and 1F), suggesting that the T cell subset responsible for the Treg IL-10 effect is antigen experienced and are most likely CD4+FoxP3-CD62L-CD44+CD45RbLo (RbLoTem) cells. The presence (Fig 1E) or absence (Fig 1F) of the IL-2Rα (CD25) on the Treg population (see S1 Fig for the gating strategy) did not have an impact on the synergistic interaction between these cells. Finally, we isolated RbLoTem and CD4+FoxP3-CD62L+CD44-CD45RbHi (RbHiTn) T cells (see S2 Fig for the gating strategy) and compared their ability to induce IL-10 synergy with FoxP3+ Tregs. Only the RbLoTem cells produced IL-10 alone and synergistically with FoxP3+ Tregs (Fig 1G). These findings align the identity of the cells capable of stimulating IL-10 production in Tregs with those which are selectively expanded by PSA [10–12]. More importantly, the data demonstrate that RbLoTem cell communication with Tregs is independent of PSA, and is therefore an intrinsic property of this regulatory T cell subset.

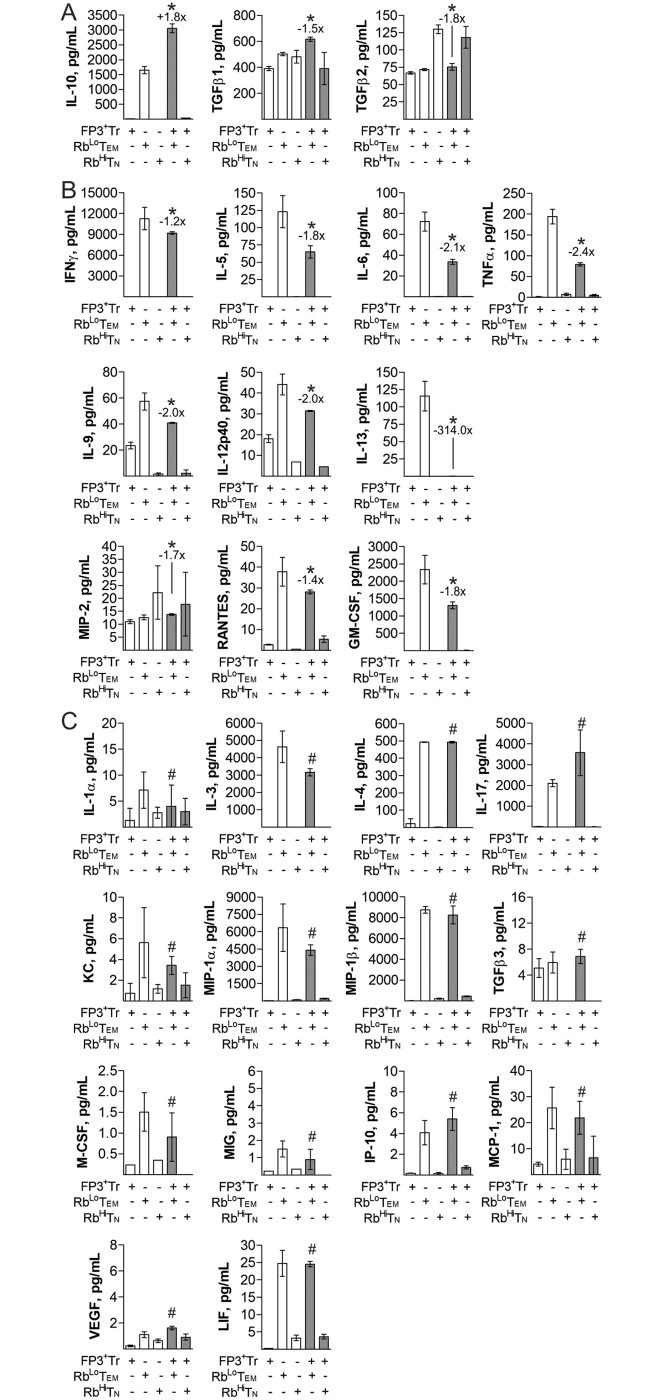

IL-10 synergy is unique among common cytokines

Although IL-10 is necessary for RbLoTem cell-mediated immune suppression [10, 12], we performed multiplex Luminex analysis in order to identify other important cytokines and chemokines. We found that IL-10 was the only cytokine tested that displayed synergistic increases when RbLoTem and FoxP3+ Tregs were in co-culture (Fig 2A). Two other cytokines closely aligned with immune regulation, TGFβ1 and TGFβ2, were significantly down-regulated in co-culture compared to the combined production of each cell population in isolation (Fig 2A). All other cytokines and chemokines fell into two categories–reduced in co-culture (Fig 2B) or unchanged in co-culture (Fig 2C). Notable molecules with robust decreases included IL-5, IL-6, IL-13, TNFα, and GM-CSF (Fig 2B), while a notable unchanged molecule was IL-4 (Fig 2C).

Fig 2. Cytokine synergy of RbLoTem and FoxP3+ Tregs is limited to IL-10.

RbLoTem and RbHiTn cells were stimulated alone or in co-culture as before for 3 days to determine cytokine and chemokine secretion in relation to the mRNA transcriptomes using multiple Luminex. Statistical comparisons were made based on differences between the sum of the FoxP3+ Treg and RbLoTem individual responses and the corresponding co-culture. Shown are immune regulation-associated proteins with significant change in co-culture (A), other cytokine and chemokines with statistically significant differences in co-culture (B), and molecules not significantly different in co-culture (C). * = p<0.05; # = p>0.05. P value calculated from Student’s T-Test. Error bars show mean with SEM. n = 3 experiments for all panels.

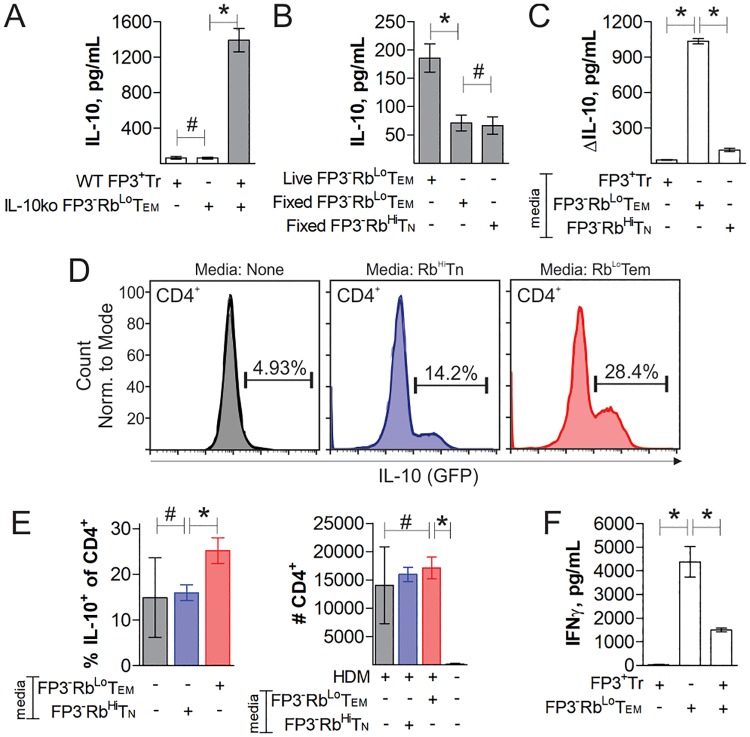

IL-10 synergy depends on a soluble mediator

Our data suggested that RbLoTem cells communicate with FoxP3+ Tregs to synergistically produce IL-10 (Figs 1 and 2). To confirm that the increase in IL-10 originated from FoxP3+ Tregs in these experiments, we cultured Tregs and RbLoTem cells alone or together as before, only using RbLoTem cells from IL-10-knockout (IL-10ko) mice. ELISA of IL-10 showed that FoxP3+ Tregs produce almost no IL-10 when cultured alone, but the inclusion of IL-10ko RbLoTem cells dramatically increased IL-10 concentration (Fig 3A). These data show that the RbLoTem cells induce FoxP3+ Tregs to produce IL-10.

Fig 3. T cell synergy is mediated by a soluble factor.

Cells were flow sorted, stimulated with anti-CD3ε antibody for 3 days, and treated as indicated. ELISA measurements of IL-10 concentration in culture supernatant from FoxP3+ Tregs co-cultured with IL-10-knockout RbLoTem (A), fixed RbLoTem or RbHiTn cells (B) or the change in IL-10 in the supernatant from cultured FoxP3+ Tregs supplemented with conditioned media from RbLoTem, RbHiTn or FoxP3+ Tregs stimulated previously for 3 days as before (C). Conditioned media from activated RbLoTem or RbHiTn cells were administered to HDM-challenged IL-10-GFP reporter mice intranasally and compared to resting and HDM-challenged mice without conditioned media. Mice were sacrificed and the BALf was analyzed by flow cytometry, showing percent IL-10+ among CD4+ cells in representative histograms (D) as well as replicates and the total CD4+ cell counts (E). ELISA measurements of IFNγ concentration in culture supernatants from FoxP3+ Tregs, WT RbLoTem, or both cells in co-culture with anti-CD3ε stimulation for 4 days (F). * = p<0.05; # = p>0.05. P value calculated from Student’s T-Test. Error bars show mean with SEM. For A-C, n = 3 to 6 experiments. For E-F, n = 3 experiments.

In order to determine the contact dependence of this communication, we measured FoxP3+ Treg IL-10 output in vitro after co-culturing with either paraformaldehyde-fixed RbLoTem or RbHiTn cells, or by supplementation of FoxP3+ Treg media with conditioned media from stimulated RbLoTem or RbHiTn cells. We found that fixation of the RbLoTem cells eliminated the synergy (Fig 3B), while RbLoTem-conditioned media was able to robustly induce IL-10 production in live FoxP3+ Tregs (Fig 3C). In addition, neutralizing antibody blockade of the Sema4-Neuropilin cell contact pathway reported to promote Treg activity [22] also did not reduce the synergistic production of IL-10 (S3 Fig). These data suggest that RbLoTem cells communicate with Tregs via a soluble mediator(s).

To confirm that conditioned media from RbLoTem cells also lead to IL-10 production in vivo, we induced pulmonary inflammation in IL-10-GFP reporter mice using lung house dust mite antigen (HDM) challenges and then intranasally administered conditioned media from either RbLoTem or RbHiTn cells, with untreated HDM mice and resting mice as controls. As seen in vitro (Fig 3C), we found that RbLoTem but not RbHiTn conditioned media significantly increased the percentage of IL-10-producing CD4+ T cells in the airway compared to untreated HDM-inflamed mice (Fig 3D and 3E). Although resting mice had too few CD4+ T cells for robust analysis of their IL-10 expression pattern, there was no difference in the total number of CD4+ T cells in all HDM-challenged mice (Fig 3E). Thus, a soluble mediator(s) produced by RbLoTem but not RbHiTn cells can induce IL-10 in FoxP3+ Tregs in vitro and in recipient lung CD4+ T cells in vivo.

Treg suppressive activity was measured in co-cultures of WT FoxP3+ Tregs and WT RbLoTem cells for 4 days with anti-CD3ε antibody stimulation. The presence of FoxP3+ Tregs significantly reduced the activation state of the RbLoTem cells, as measured by IFNγ ELISA, supporting the conclusion that the Tregs are active and suppressive (Fig 3F).

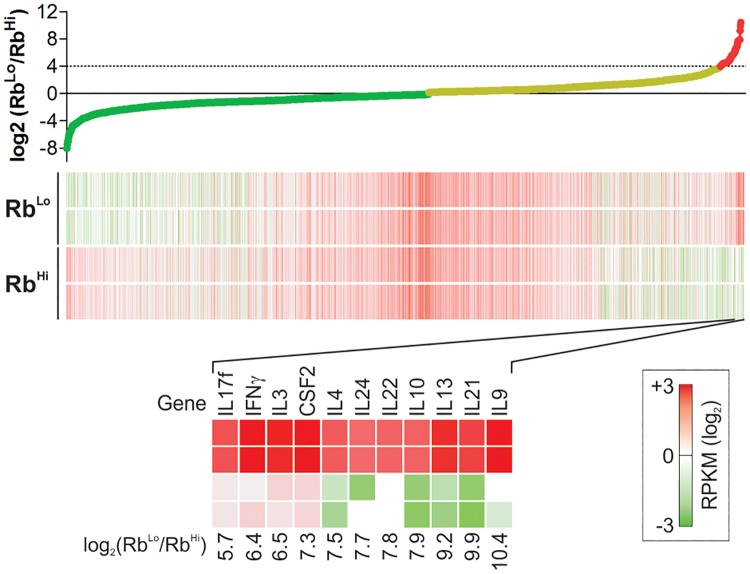

The RbLoTem transcriptome

In order to identify the mediator(s), we compared the transcriptomes of anti-CD3ε activated RbLoTem and RbHiTn cells by mRNA deep sequencing (RNAseq). We arranged the change in copy number by the ratio of RbLoTem to RbHiTn RPKM values because we predicted that the mediator must be significantly up-regulated in the RbLoTem population relative to the RbHiTn population. Lead candidates were robustly transcribed (RPKM > 2), at least 16-fold greater in RbLoTem over RbHiTn cells, and known to be secreted (i.e., non-membrane proteins; not found in the nucleus or cytoplasm). This analysis revealed a list of highly up-regulated genes which might account for the activity of these cells, including IFNγ, IL-4, IL-22 and others (Fig 4).

Fig 4. RbLoTem and RbHiTn transcriptomes reveal potential crosstalk mediators.

RbLoTem and RbHiTn cells were stimulated alone as before for 3 days, and RNA was isolated for deep sequencing and whole transcriptome analysis. Genes were arranged according to the log2 of the RbLoTem to RbHiTn ratio of expression, using the calculated RPKM values. Candidates were narrowed by excluding all membrane proteins, proteins known to exist only in the nucleus or cytoplasm, and those showing at least 16-fold increase in RbLoTem cells compared to RbHiTn cells. n = 2 per cell type.

Neutralization of IL-4 eliminates IL-10 synergy

In order to identify the molecules mediating T cell synergy, we performed antibody neutralization experiments during co-culture of FoxP3+ Treg and RbLoTem cells based on the transcriptomic data (Fig 4). We found that neutralization of IL-4 eliminated the synergistic production of IL-10 (Fig 5A). In repeat experiments comparing neutralization of IL-4 to neutralization of IL-4Rα (CD124), which inhibits both type I and type II IL-4 receptor complexes, we found a corresponding elimination of IL-10 synergy (Fig 5B). To identify which cell the IL-4 was impacting, we neutralized CD124 on only the RbLoTem cells by pre-incubation with the antibody, washing away unbounded antibody, then co-culturing the CD124-blocked RbLoTem cells with fresh FoxP3+ Tregs. We found no difference in IL-10 synergy (Fig 5C). However, the inverse experiment in which the FoxP3+ Tregs were pre-blocked with anti-CD124 revealed robust inhibition of synergy (Fig 5D). Moreover, we tested the impact of IL-4 neutralization in FoxP3+ Treg mono-cultures using conditioned media from RbLoTem cells. Once again, we found that blockade of IL-4 eliminated the IL-10 response (Fig 5E).

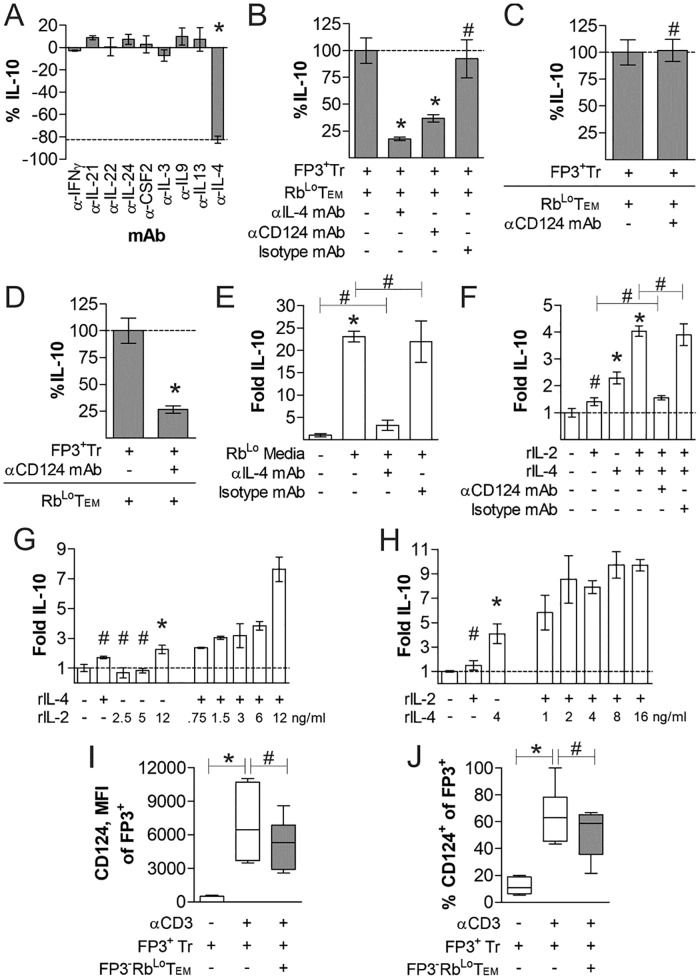

Fig 5. IL-4 and FoxP3+ Treg IL-4Rα (CD124) mediates Treg IL-10 production.

FoxP3+ Tregs and RbLoTem were stimulated in co-culture as before for 3 days with the addition of cytokine (A) or receptor (B) neutralizing antibodies to identify the mediator of IL-10 synergy. (C) To determine whether IL-4 was acting on RbLoTem cells or FoxP3+ Tregs, (C) RbLoTem cells were incubated with CD124 neutralizing antibody, washed, then co-cultured with fresh FoxP3+ Tregs as before (C); and then compared to pre-incubating FoxP3+ Tregs with CD124 antibody followed by co-culture with RbLoTem cells (D). FoxP3+ Tregs were stimulated as before in monoculture supplemented with either conditioned media from stimulated RbLoTem cells (E) or various concentrations, denoted in ng/mL, of recombinant IL-2 or IL-4 (F-H) with and without neutralizing IL-4 or CD124 antibodies (E-H). (I-J) FoxP3+ Tregs were cultured with and without αCD3ε stimulation, as well as with and without RbLoTem cells. At day 3, cells were harvested and stained for CD124 expression, and analyzed by geometric mean fluorescence intensity (I) and the percent CD124 positive among FoxP3+ Tregs (J). * = p<0.05; # = p>0.05. P value calculated from Student’s T-Test, with comparisons to control unless specified. Error bars show mean with SEM. For A-H, n = 3 to 6 experiments. For I-J, n = 6 experiments.

In order to determine whether IL-4 was necessary and/or sufficient to induce IL-10 in Tregs, we cultured FoxP3+ Tregs with fresh media supplemented with recombinant IL-4 (rIL-4) and IL-2 (rIL-2) together and independently. Although our data already demonstrated that IL-2 was not the primary driver of IL-10 production (Fig 1D & 1F), IL-2 was used because IL-2 concentrations robustly decrease in co-culture (Fig 1D), suggesting that it may play the well-documented pro-survival role for Tregs [23]. We found that rIL-4 induced IL-10 in mono-cultured FoxP3+ Tregs, but that the addition of IL-2 greatly enhanced this response despite the failure of IL-2 to robustly induce IL-10 in the absence of IL-4 (Fig 5F). This effect was dependent upon CD124, since neutralizing antibody completely reversed the impact of rIL-4 supplementation (Fig 5F). Cytokine titration experiments with isolated FoxP3+ Tregs and varied concentrations of rIL-2 (Fig 5G) and rIL-4 (Fig 5H) further demonstrated the dose-response nature of IL-10 production downstream of exposure to these cytokines. We also found that the expression of CD124 in FoxP3+ Tregs was dependent upon prior stimulation with αCD3ε antibody, and this expression was not impacted by the presence of RbLoTem cells (Fig 5I and 5J).

RbLoTem cells require IL-4 to protect mice from pulmonary inflammation

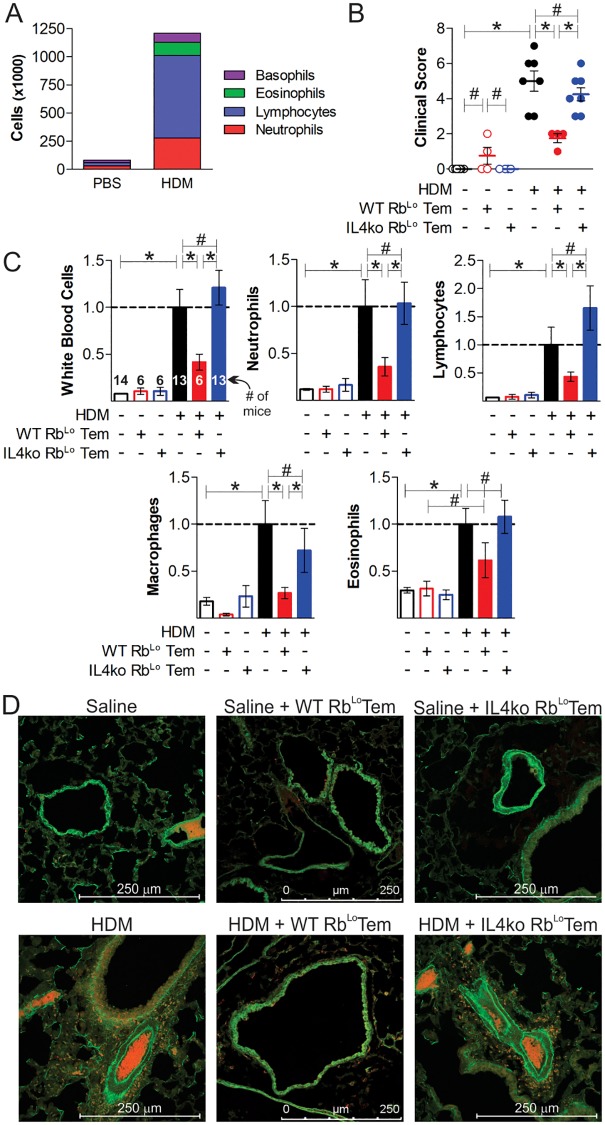

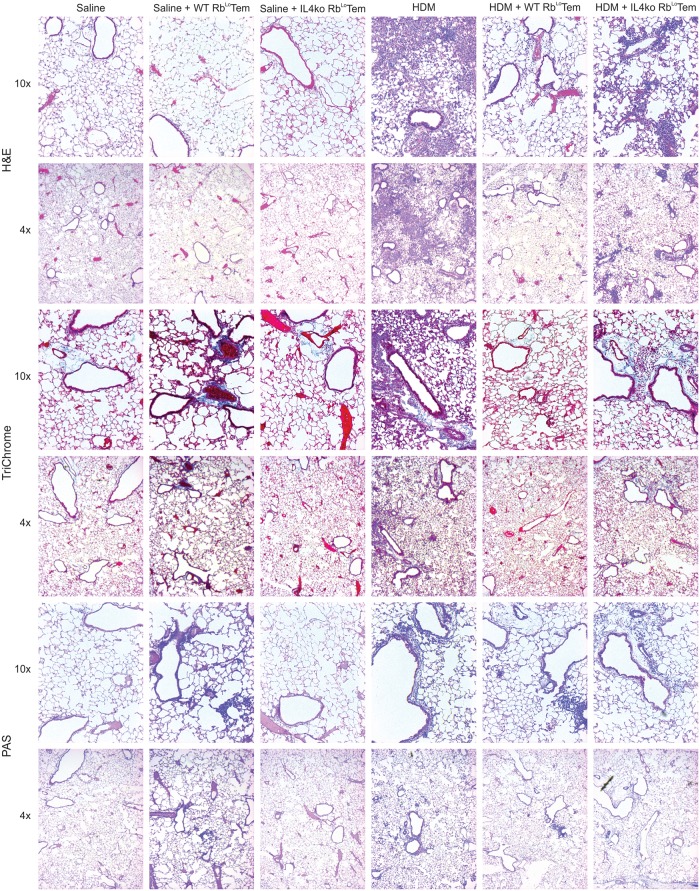

The in vitro experiments implicate RbLoTem cells as a key population of T cells capable of inducing IL-10 release by FoxP3+ Tregs, while transcriptomic and antibody-mediated neutralization experiments implicated a dependence upon IL-4 to promote this response. In order to test the RbLoTem protective activity and their dependence on IL-4 in vivo, we performed an adoptive transfer experiment into a house dust mite (HDM)-induced acute asthma model. RbLoTem cells were isolated as before (S2 Fig) from either WT or IL-4 knockout (IL-4ko) mice, stimulated in vitro for 48 hours with anti-CD3ε antibody, then transferred via the tail vein into recipient WT mice on day 7 of HDM challenges. Robust immune suppression, as measured by the total number of airway-infiltrating leukocytes (Fig 6A), overall clinical score (Fig 6B; Table 1), neutrophils, lymphocytes, macrophages and eosinophils (Fig 6C) recovered in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALf), was achieved with a single transfer of 60,000 WT cells. Moreover, tissue pathology measured by confocal microscopy for activated leukocytes (Fig 6D) and hematoxylin and eosin staining (H&E; Fig 7) was returned to baseline in mice receiving WT RbLoTem cells, while TriChrome and periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining revealed a reversal of collagen deposition (i.e. tissue remodeling) and mucus production, respectively (Fig 7). Importantly, this potent ability to reverse lung inflammation was lost when the RbLoTem cells lacked IL-4 (Figs 6 and 7), confirming the central role for IL-4 in RbLoTem-mediated immune suppression.

Fig 6. RbLoTem cells reverse lung inflammation in an IL-4-dependent fashion.

Mice were given 60,000 of anti-CD3ε-stimulated WT or IL-4ko RbLoTem cells on day 7 of acute HDM-induced asthma to test their ability to reverse inflammatory pathology. The total number of infiltrating cells (A), the clinical score (see Table 1) (B), normalized cellular differentials from BALf harvests (C), and tissue pathology (D) by immunofluorescence staining for EpCAM (green) and MPO (red) from representative sections of pulmonary tissue are shown. * = p<0.05; # = p>0.05. P value calculated from an unpaired Student’s T-Test. Error bars show mean with SEM. n = 6 to 14 individual mice total per group, across two asthma trials, as indicated on the White Blood Cell counts in panel C.

Fig 7. Lung inflammation, remodeling and mucus production is reversed by RbLoTem cells in an IL-4-dependent fashion.

Representative lung sections from n = 6 mice at 4x and 10x magnification from the mice described in Fig 6 were stained with H&E (top), TriChrome (middle) and PAS (bottom) to assess cellular infiltration, tissue remodeling/collagen deposition and mucus production respectively in HDM-challenged mice receiving 60,000 activated WT or IL-4ko RbLoTem cells.

Discussion

In this study, we discovered a novel pathway of immune suppression mediated by the RbLoTem subset of regulatory T cells. We found that FoxP3-CD4+CD62L-CD44+CD45RbLo effector/memory T cells (RbLoTem) coordinate a regulatory circuit in which they communicate with FoxP3+ Tregs to synergistically enhance IL-10 production, leading to the suppression of IFNγ and other cytokines in vitro and pulmonary inflammation in vivo. We also discovered that this pathway is mediated by a combination of IL-2 and IL-4 secreted by RbLoTem cells, leading to ligation of IL-4Rα (CD124) on αCD3ε-activated FoxP3+ Tregs and subsequent IL-10 production. The discovery of a novel T-effector cell-driven regulatory pathway and its underlying mechanism could have a major impact on how we understand the resolution of inflammation, the maintenance of homeostasis throughout the body, Treg behavior, and possibly how to control a variety of inflammatory diseases.

The interplay between T cell subsets to favor a particular response is not a novel concept. A recent example is the interaction between neuropilin-1 (Nrp1) and semaphorin-4a (Sema4a)[22]. Association of surface Sema4a on Tconv cells with Nrp1 on Tregs increased Treg survival and function in vitro and was found to be required for the in vivo suppression of inflammatory bowel disease. Here, we found that the direct cell-to-cell contact via the Sema4a-Nrp1 axis does not account for the suppressive influence of RbLoTem cells on Tregs, as neutralization of Nrp1 with an antibody had no impact on in vitro IL-10 synergy. Instead, our data strongly support a contact-independent mechanism which relies upon soluble mediators, IL-2 and IL-4.

Since the establishment of the TH1/TH2 paradigm [24–26], it has been widely recognized that TH1 responses oppose TH2 responses, and vice versa, and that this is driven by key TH1 or TH2-associated cytokines. IL-4 has long been characterized as a central inducer of TH2 cell development [27], a characteristic cytokine made by TH2 cells [24–26], and a critical factor leading to the suppression of TH1 cell differentiation [27–29]. TH2 responses were originally described as including IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, and IL-10 [24–26]. As sophistication in the laboratory setting increased, IL-6 and IL-10 were removed from this general list, but it is pertinent to recall that IL-4 has been well documented to induce IL-10 production in T cells [30]. In fact, IL-4 was linked to anti-inflammatory activity as far back as 1989 [31]. A more recent human trial demonstrated that subcutaneous injection of psoriatic lesions with human IL-4 significantly reduced clinical scores [32], while IL-4 expression from a viral vector was able to prevent chondrocyte death and reduce cartilage erosion in a murine model of collagen-induced arthritis [33]. In EAE, gene delivery of IL-4 into mice selectively recruited FoxP3+CD25+ Tregs which eliminated the disease pathology [34]. IL-4 has also been implicated in the regulatory mechanisms required for the anti-inflammatory effects of intravenous immunoglobulin [35], and is known to be a robust driver of the wound healing phenotype of many macrophages, which includes IL-10 and TGFβ release [36, 37]. Indeed, IL-4 was previously shown to increase the suppressive capacity of CD25+ Tregs in vitro, although IL-10 was not assessed at the time [38]. Although it is unclear why IL-4 was not depleted in our experiments (Fig 2) like IL-2 (Fig 1), it may be explained by differences in the relative rates of cytokine release by RbLoTem cells and consumption by Tregs, these findings not only show that IL-4 is a highly pleiotropic cytokine with a robust history of immune suppression, but they also strongly support the notion that RbLoTem cells could use IL-4 as a key driver of IL-10 and immune suppression under at least some inflammatory conditions.

In terms of asthma, the role of IL-4 is not entirely clear. In early descriptions of asthma one hundred years ago, asthma was divided into “intrinsic” or non-atopic and “extrinsic” atopic disease [39]. However, in the 1980s, the notion that asthma was nearly always atopic came into prominence [40], which lead to the use of asthma as an exemplar TH2-mediated atopic disease characterized by TH2 cytokines like IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13, eosinophilia and increased IgE production [24–26]. More recent large-cohort studies, such as those conducted by the Severe Asthma Research Program (SARP), have reinvigorated the division of asthma into specific endotypes based on a variety of clinical characteristics. Of these endotypes, it is now widely recognized that atopic asthma is not the only endotype, and that non-atopic asthma accounts for up to 51% of all asthma cases in the US [41].

Consistent with the interpretation that IL-4 is not a central driver of asthma, a number of clinical trials designed to selectively inhibit IL-4 in asthma patients have failed. The trials for a neutralizing anti-IL-4 antibody (Pasolizumab), a soluble IL-4 decoy receptor (Altrakincept), and even a mutant form of IL-4 with a proposed dominant negative impact on IL-4 function (Pitrakinra) all were halted due to a lack of meeting clinical benchmarks of efficacy. In contrast, efforts simultaneously targeting both IL-4 and IL-13 through IL-4Rα blockade have been more successful (Dupliumab), and primarily in eosinophilic asthma [42]. Since IL-13 uses the type II IL-4 receptor, which is comprised of IL-4Rα (CD124) and IL-13Rα (CD213a), the efficacy of Dupliumab supports the notion that IL-13 may be the more important cytokine in terms of asthma pathology. It is also becoming clear that the non-atopic neutrophilic endotypes are more likely driven by a Th17-dominated response, and these patients are much more likely to have greater disease severity and corticosteroid-resistance. Our results using a model of neutrophilic asthma (Fig 6A) fit with the well-known phenomenon that IL-4 opposes Th1 and Th17 responses, and induces IL-10 release in T cells [28, 29].

In summary, our work has revealed a novel T cell-to-T cell regulatory pathway in which IL-2 and IL-4 from RbLoTem cells trigger the release of IL-10 in activated FoxP3+ Tregs, and that this response can reverse the pathologies associated with HDM-induced neutrophilic lung inflammation in mice. This model fits well into the greater IL-4 literature, implicates a number of additional therapeutic targets within the IL-4Rα pathway which could be explored as clinical therapies, and highlights the myriad of ways in which T cell-mediated responses can be regulated.

Supporting information

Experimental design for the gating strategy utilized to capture CD4+FoxP3+CD25+ and CD4+FoxP3+CD25- cells from magnetically sorted splenocytes from FoxP3-RFP reporter mice.

(TIF)

Experimental design schematic detailing the staining and gating strategy used to isolate CD4+FoxP3+, CD4+FoxP3-CD45RbLoCD44+CD62L-, and CD4+FoxP3-CD45RbLoCD44+CD62L- cells from CD4+ magnetically sorted splenocytes.

(TIF)

ELISA measurements of IL-10 in mono- and co-culture supernatants after 72h from FoxP3+ Tregs or CD4+CD45RbLo and CD4+CD45RbHi cells from IL-10n animals. Cells were grown with or without stimulus from plate-bound αCD3ε and supplementation with a blocking αNeuropilin1 antibody. Error bars show mean with SEM.

(TIF)

Acknowledgments

We thank Janice C. Jun and Doug M. Oswald for technical support during dissections, and Jenifer Mikulan for histological technical support. We are also grateful for the technical support of the Cytometry and Imaging Microscopy Core Facility of the Case Comprehensive Cancer Center, and Alex Huang, MD, PhD for non-confocal histological imaging.

Abbreviations

- BALf

bronchoalveolar lavage fluid

- MHCII

class II major histocompatibility complex

- EAE

experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis

- FoxP3+

CD4+FoxP3+ Treg

- FoxP3-RbHi

CD4+FoxP3-CD45RbHi T cell

- FoxP3-RbLo

CD4+FoxP3-CD45RbLo T cell

- GM-CSF

granulocyte/macrophage colony stimulating factor

- HDM

house dust mite

- IFNγ

interferon gamma

- iTregs

inducible Tregs

- IL

interleukin

- IL-10n

IL-10 null

- IL-4ko

IL-4-knockout

- IBD

inflammatory bowel disease

- MPO

myeloperoxidase

- OVA

ovalbumin

- PSA

Bacteroides fragilis polysaccharide A

- RPKM

reads per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads

- Treg

regulatory T cells

- Tconv

T conventional (CD25-CD4+)

- Tcm

T central memory (FoxP3-CD62L+CD44+CD4+)

- Tem

T effector/memory (FoxP3-CD62L-CD44+CD4+)

- Tn

T naive (FoxP3-CD62L+CD44-CD4+)

- RbLoTem

CD45Rb-low T effector/memory (FoxP3-CD62L-CD44+CD45RbLoCD4+)

- TH2

type II helper T cell

- WT

wild type

Data Availability

Raw and processed data files for all RNA deep sequencing have been deposited in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus under accession number GSE89241. All other relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

The authors declare no financial competing interests. This work was supported from grants from: The National Institutes of Health (R01-GM082916, R01-GM115234), the American Asthma Foundation (#10-0187), and the Hartwell Foundation to BC, the National Institutes of Health (F32-AI114109, T32-AI007024) to MJ, and the National Institutes of Health (T32-AI089474) to JJ, JZ, and CA. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Shevach EM. Foxp3(+) T Regulatory Cells: Still Many Unanswered Questions-A Perspective After 20 Years of Study. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1048 Epub 2018/06/06. 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01048 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sakaguchi S, Vignali DA, Rudensky AY, Niec RE, Waldmann H. The plasticity and stability of regulatory T cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13(6):461–7. Epub 2013/05/18. 10.1038/nri3464 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rudensky AY. Regulatory T cells and Foxp3. Immunol Rev. 2011;241(1):260–8. Epub 2011/04/15. 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01018.x . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Battaglia M, Gregori S, Bacchetta R, Roncarolo MG. Tr1 cells: From discovery to their clinical application. Seminars in Immunology. 2006;18(2):120–7. 10.1016/j.smim.2006.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roncarolo MG, Gregori S, Battaglia M, Bacchetta R, Fleischhauer K, Levings MK. Interleukin-10-secreting type 1 regulatory T cells in rodents and humans. Immunol Rev. 2006;212:28–50. Epub 2006/08/15. 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00420.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morrissey PJ, Charrier K. Induction of wasting disease in SCID mice by the transfer of normal CD4+/CD45RBhi T cells and the regulation of this autoreactivity by CD4+/CD45RBlo T cells. Res Immunol. 1994;145(5):357–62. Epub 1994/06/01. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shimada A, Charlton B, Rohane P, Taylor-Edwards C, Fathman CG. Immune regulation in type 1 diabetes. J Autoimmun. 1996;9(2):263–9. Epub 1996/04/01. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smart V, Foster PS, Rothenberg ME, Higgins TJ, Hogan SP. A plant-based allergy vaccine suppresses experimental asthma via an IFN-gamma and CD4+CD45RBlow T cell-dependent mechanism. J Immunol. 2003;171(4):2116–26. Epub 2003/08/07. 10.4049/jimmunol.171.4.2116 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ruiz-Perez B, Chung DR, Sharpe AH, Yagita H, Kalka-Moll WM, Sayegh MH, et al. Modulation of surgical fibrosis by microbial zwitterionic polysaccharides. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(46):16753–8. Epub 2005/11/09. 10.1073/pnas.0505688102 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson JL, Jones MB, Cobb BA. Bacterial capsular polysaccharide prevents the onset of asthma through T-cell activation. Glycobiology. 2015;25(4):368–75. 10.1093/glycob/cwu117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson JL, Jones MB, Cobb BA. Polysaccharide A from the capsule of Bacteroides fragilis induces clonal CD4+ T cell expansion. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(8):5007–14. Epub 2014/12/30. 10.1074/jbc.M114.621771 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson JL, Jones MB, Cobb BA. Polysaccharide-experienced effector T cells induce IL-10 in FoxP3+ regulatory T cells to prevent pulmonary inflammation. Glycobiology. 2018;28(1):50–8. Epub 2017/11/01. 10.1093/glycob/cwx093 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kamanaka M, Huber S, Zenewicz LA, Gagliani N, Rathinam C, O’Connor W Jr., et al. Memory/effector (CD45RB(lo)) CD4 T cells are controlled directly by IL-10 and cause IL-22-dependent intestinal pathology. J Exp Med. 2011;208(5):1027–40. Epub 2011/04/27. 10.1084/jem.20102149 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Asseman C, Mauze S, Leach MW, Coffman RL, Powrie F. An essential role for interleukin 10 in the function of regulatory T cells that inhibit intestinal inflammation. J Exp Med. 1999;190(7):995–1004. Epub 1999/10/06. 10.1084/jem.190.7.995 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kreisman LS, Cobb BA. Glycoantigens induce human peripheral Tr1 cell differentiation with gut-homing specialization. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(11):8810–8. Epub 2011/01/14. 10.1074/jbc.M110.206011 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson JR, Wiley RE, Fattouh R, Swirski FK, Gajewska BU, Coyle AJ, et al. Continuous exposure to house dust mite elicits chronic airway inflammation and structural remodeling. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169(3):378–85. Epub 2003/11/05. 10.1164/rccm.200308-1094OC . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(15):2114–20. Epub 2014/04/04. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim D, Pertea G, Trapnell C, Pimentel H, Kelley R, Salzberg SL. TopHat2: accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biol. 2013;14(4):R36 Epub 2013/04/27. 10.1186/gb-2013-14-4-r36 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frankish A, Uszczynska B, Ritchie GR, Gonzalez JM, Pervouchine D, Petryszak R, et al. Comparison of GENCODE and RefSeq gene annotation and the impact of reference geneset on variant effect prediction. BMC Genomics. 2015;16 Suppl 8:S2 Epub 2015/06/26. 10.1186/1471-2164-16-S8-S2 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anders S, Pyl PT, Huber W. HTSeq-a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2015;31(2):166–9. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15(12):550 Epub 2014/12/18. 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Delgoffe GM, Woo SR, Turnis ME, Gravano DM, Guy C, Overacre AE, et al. Stability and function of regulatory T cells is maintained by a neuropilin-1-semaphorin-4a axis. Nature. 2013;501(7466):252–+. 10.1038/nature12428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arenas-Ramirez N, Woytschak J, Boyman O. Interleukin-2: Biology, Design and Application. Trends Immunol. 2015;36(12):763–77. Epub 2015/11/18. 10.1016/j.it.2015.10.003 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mosmann TR. Regulation of immune responses by T cells with different cytokine secretion phenotypes: role of a new cytokine, cytokine synthesis inhibitory factor (IL10). Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol. 1991;94(1–4):110–5. Epub 1991/01/01. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mosmann TR, Cherwinski H, Bond MW, Giedlin MA, Coffman RL. Two types of murine helper T cell clone. I. Definition according to profiles of lymphokine activities and secreted proteins. J Immunol. 1986;136(7):2348–57. Epub 1986/04/01. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mosmann TR, Coffman RL. TH1 and TH2 cells: different patterns of lymphokine secretion lead to different functional properties. Annu Rev Immunol. 1989;7:145–73. Epub 1989/01/01. 10.1146/annurev.iy.07.040189.001045 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Akdis M, Burgler S, Crameri R, Eiwegger T, Fujita H, Gomez E, et al. Interleukins, from 1 to 37, and interferon-gamma: receptors, functions, and roles in diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127(3):701–21 e1–70. Epub 2011/03/08. 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.11.050 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Janeway CA, Travers P, Walport M, Shlomchik M. Immunobiology: The Immune System in Health & Disease. 6th edition ed. Hamden, CT: Garland Publishing; 2005. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mak TW, Saunders ME, Jett BD. Primer to the Immune Response. 2 ed: Newnes; 2013 12/23/2013.

- 30.Chang HD, Helbig C, Tykocinski L, Kreher S, Koeck J, Niesner U, et al. Expression of IL-10 in Th memory lymphocytes is conditional on IL-12 or IL-4, unless the IL-10 gene is imprinted by GATA-3. European Journal of Immunology. 2007;37(3):807–17. 10.1002/eji.200636385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hart PH, Vitti GF, Burgess DR, Whitty GA, Piccoli DS, Hamilton JA. Potential antiinflammatory effects of interleukin 4: suppression of human monocyte tumor necrosis factor alpha, interleukin 1, and prostaglandin E2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86(10):3803–7. Epub 1989/05/01. 10.1073/pnas.86.10.3803 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ghoreschi K, Thomas P, Breit S, Dugas M, Mailhammer R, van Eden W, et al. Interleukin-4 therapy of psoriasis induces Th2 responses and improves human autoimmune disease. Nat Med. 2003;9(1):40–6. Epub 2002/12/04. 10.1038/nm804 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lubberts E, Joosten LA, van Den Bersselaar L, Helsen MM, Bakker AC, van Meurs JB, et al. Adenoviral vector-mediated overexpression of IL-4 in the knee joint of mice with collagen-induced arthritis prevents cartilage destruction. J Immunol. 1999;163(8):4546–56. Epub 1999/10/08. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Butti E, Bergami A, Recchia A, Brambilla E, Del Carro U, Amadio S, et al. IL4 gene delivery to the CNS recruits regulatory T cells and induces clinical recovery in mouse models of multiple sclerosis. Gene Ther. 2008;15(7):504–15. Epub 2008/02/02. 10.1038/gt.2008.10 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anthony RM, Kobayashi T, Wermeling F, Ravetch JV. Intravenous gammaglobulin suppresses inflammation through a novel T(H)2 pathway. Nature. 2011;475(7354):110–U33. 10.1038/nature10134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gordon S. Alternative activation of macrophages. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3(1):23–35. Epub 2003/01/04. 10.1038/nri978 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ponomarev ED, Maresz K, Tan Y, Dittel BN. CNS-Derived interleukin-4 is essential for the regulation of autoimmune inflammation and induces a state of alternative activation in microglial cells. Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27(40):10714–21. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1922-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maerten P, Shen C, Bullens DM, Van Assche G, Van Gool S, Geboes K, et al. Effects of interleukin 4 on CD25+CD4+ regulatory T cell function. J Autoimmun. 2005;25(2):112–20. Epub 2005/07/30. 10.1016/j.jaut.2005.04.001 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rackemann FM. A clinical study of 150 cases of bronchial asthma. Boston Medical and Surgical Journal. 1918;178:770–2. 10.1056/Nejm191806061782302 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Adkinson NF Jr. Is asthma always an allergic disease? Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 1992;103:218–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moore WC, Meyers DA, Wenzel SE, Teague WG, Li HS, Li XN, et al. Identification of Asthma Phenotypes Using Cluster Analysis in the Severe Asthma Research Program. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2010;181(4):315–23. 10.1164/rccm.200906-0896OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Iftikhar IH, Schimmel M, Bender W, Swenson C, Amrol D. Comparative Efficacy of Anti IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13 Drugs for Treatment of Eosinophilic Asthma: A Network Meta-analysis. Lung. 2018;196(5):517–30. Epub 2018/09/01. 10.1007/s00408-018-0151-5 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Experimental design for the gating strategy utilized to capture CD4+FoxP3+CD25+ and CD4+FoxP3+CD25- cells from magnetically sorted splenocytes from FoxP3-RFP reporter mice.

(TIF)

Experimental design schematic detailing the staining and gating strategy used to isolate CD4+FoxP3+, CD4+FoxP3-CD45RbLoCD44+CD62L-, and CD4+FoxP3-CD45RbLoCD44+CD62L- cells from CD4+ magnetically sorted splenocytes.

(TIF)

ELISA measurements of IL-10 in mono- and co-culture supernatants after 72h from FoxP3+ Tregs or CD4+CD45RbLo and CD4+CD45RbHi cells from IL-10n animals. Cells were grown with or without stimulus from plate-bound αCD3ε and supplementation with a blocking αNeuropilin1 antibody. Error bars show mean with SEM.

(TIF)

Data Availability Statement

Raw and processed data files for all RNA deep sequencing have been deposited in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus under accession number GSE89241. All other relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.