Abstract

Genetic and epigenetic intra-tumoral heterogeneity cooperate to shape the evolutionary course of cancer1. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is a highly informative model for cancer evolution as it undergoes substantial genetic diversification and evolution with therapy2,3. The CLL epigenome is also an important disease-defining feature4,5, and growing CLL populations diversify through stochastic DNA methylation (DNAme) changes – epimutations6. However, previous studies based on bulk DNAme sequencing could not answer whether epimutations affect CLL populations homogenously. To measure epimutation rate at single-cell resolution, we applied multiplexed single-cell reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (MscRRBS) to healthy donors B cell and CLL patient samples. We observed that the common clonal CLL origin results in consistently elevated epimutation rate, with low cell-to-cell epimutation rate variability. In contrast, variable epimutation rates across normal B cells reflect diverse evolutionary ages across the B cell differentiation trajectory, consistent with epimutations serving as a molecular clock. Heritable epimutation information allowed high-resolution lineage reconstruction with single-cell data, applicable directly to patient samples. CLL lineage tree shape revealed earlier branching and longer branch lengths than normal B cells, reflecting rapid drift after the initial malignant transformation and a greater proliferative history. MscRRBS integrated with single-cell transcriptomes and genotyping confirmed that genetic subclones map to distinct clades inferred solely based on epimutation information. Lastly, to examine potential lineage biases during therapy, we profiled serial samples during ibrutinib-associated lymphocytosis, and identified clades of cells preferentially expelled from the lymph node with therapy, marked by distinct transcriptional profiles. The single-cell integration of genetic, epigenetic and transcriptional information thus charts CLL’s lineage history and its evolution with therapy.

Keywords: cancer, leukemia, DNA methylation, single cell, epigenetics, somatic evolution

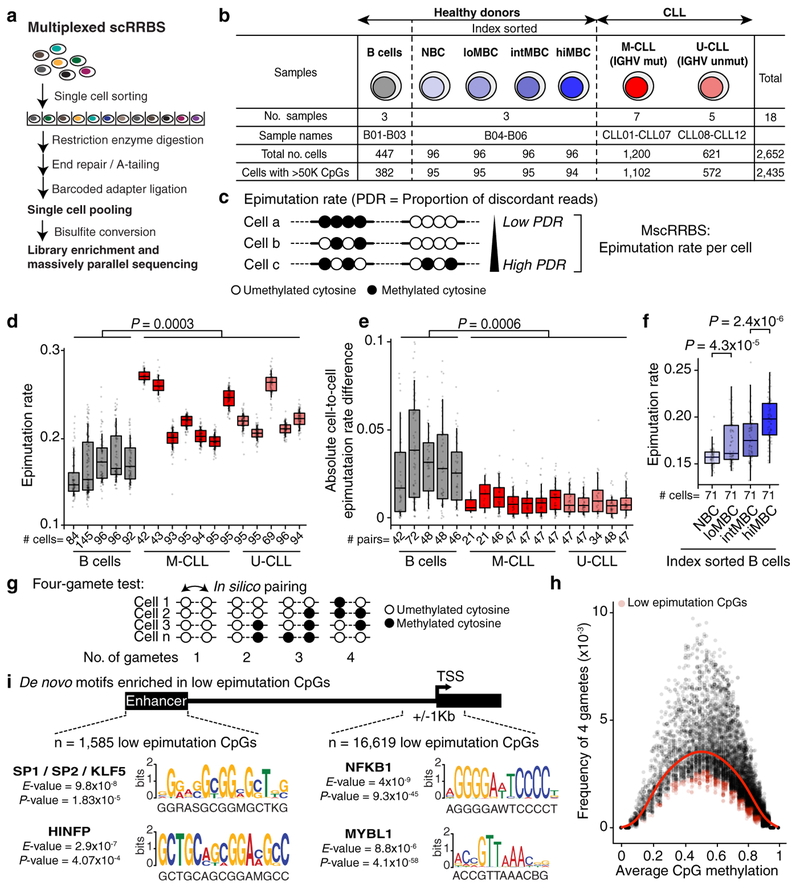

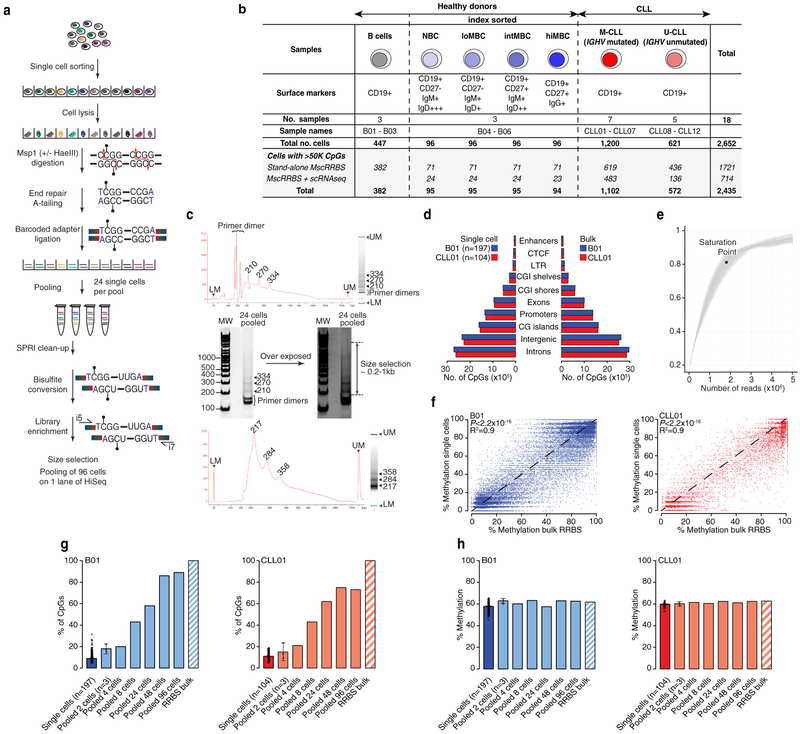

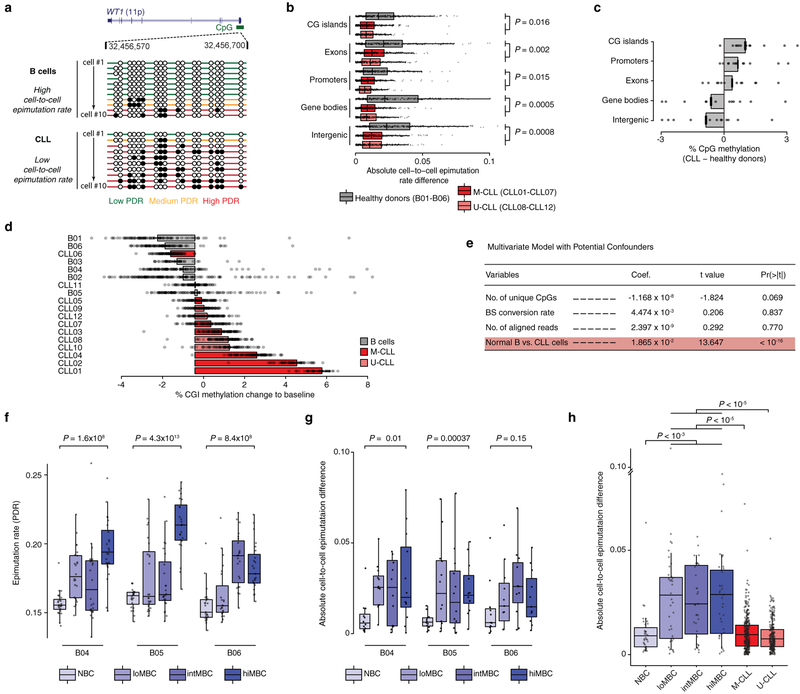

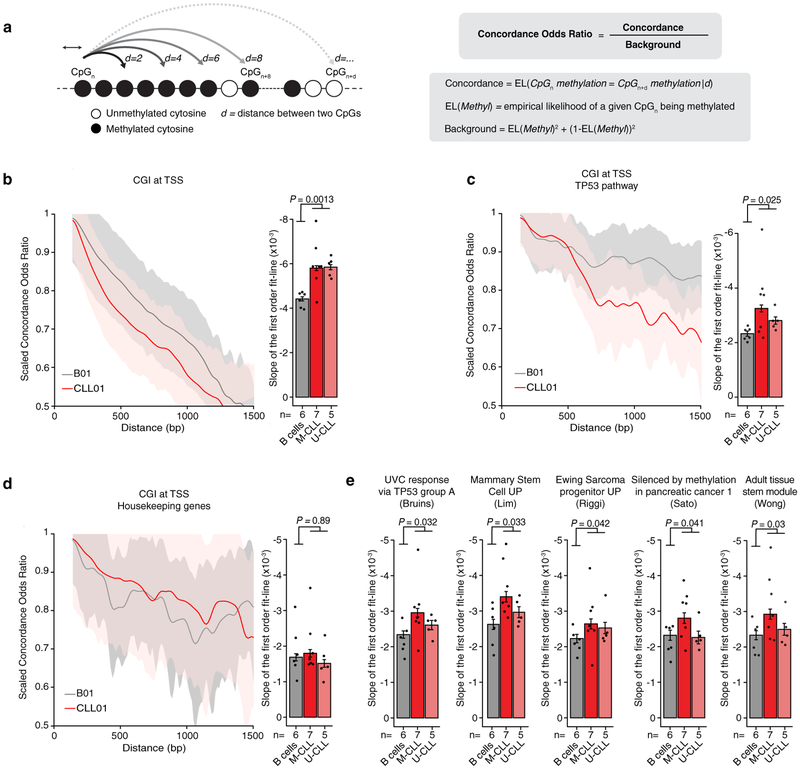

To measure intra-sample epimutation rate variability, we profiled single-cell DNAme of 831 normal B cells from six healthy donors, including B cells across the maturation spectrum, and 1,821 cells from 12 primary IGHV mutated and unmutated CLLs (M-CLL and U-CLL, respectively; Fig. 1a, b; Extended Data Fig. 1, 2; Supplementary Table 1–4). The average epimutation rate (measured through proportion of discordant reads [PDR]6; Fig. 1c) was higher in CLLs compared to normal B cells (Mann-Whitney U-test, P = 0.0003; Fig. 1d), in line with previous bulk DNAme sequencing6. Uniquely, the single-cell measurement showed that CLL epigenome exhibited consistently elevated epimutation rates (i.e., low cell-to-cell variation in epimutation rate), irrespective of their IGHV mutational status, compared to CD19+ B cells (Mann-Whitney U-test, P = 0.0006; Fig. 1e; Extended Data Fig. 3a). Lower epimutation rate variability in CLL compared to normal B cells was observed across all genomic regions, including regions hypermethylated (e.g., CpG islands [CGIs]) or hypomethylated (e.g., intergenic regions) in CLL (Extended Data Fig. 3b–e). The common origin of CLL cells from a single, transformed cell is thus reflected in minimal cell-to-cell epimutation rate variability. In contrast, normal B cells represent an admixture of cells with different replicative histories, with newly formed naïve intermixed with long-lived post-germinal center memory B cells, showing highly variable epimutation rates. Indeed, epimutation rates of index-sorted B cell subsets progressively increased during B cell maturation (Fig. 1f; Extended Data Fig. 3f, g). Notably, CLL epimutation rate showed lower cell-to-cell variation compared to even these well-defined B cell subsets, especially those from low- to high-maturity memory B cells, which more closely resemble CLL in their epigenetic profiles4 (Extended Data Fig. 3h). These results are consistent with epimutation rate correlating with the cell’s proliferative history, serving as an epigenetic molecular clock7–9.

Figure 1. Consistently elevated epimutation rate defines the CLL epigenome.

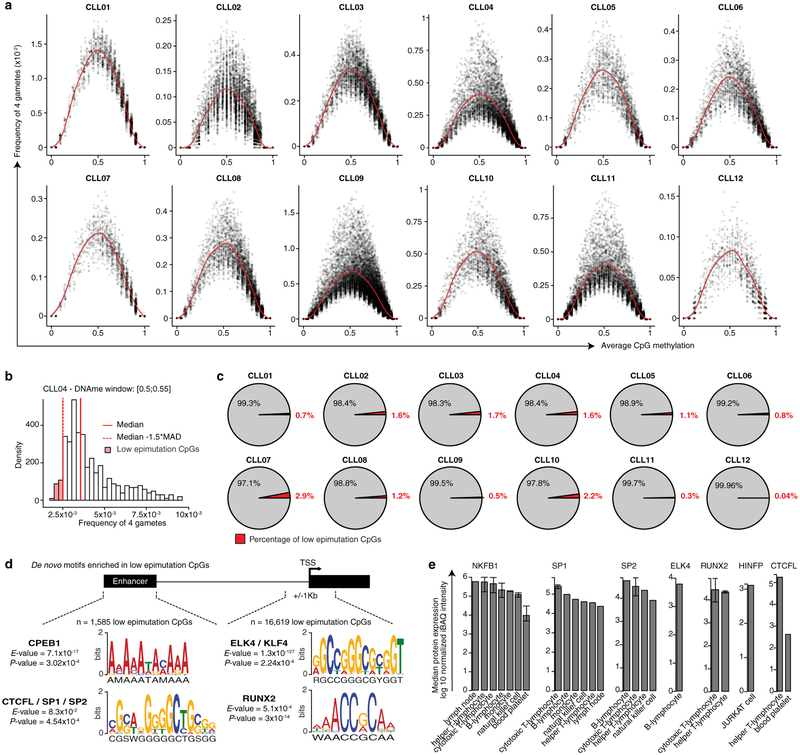

(a) Schematic of multiplexed single-cell RRBS (MscRRBS) protocol. See also Extended Data Fig. 1a. (b) Summary of healthy donors and CLL samples (naïve [NBC]; low-, intermediate-, high-maturity memory B cells [loMBC, intMBC, hiMBC]; IGHV mutated and unmutated CLL [M-CLL, U-CLL]). (c) Epimutations are measured as the proportion of discordant reads (PDR). (d) Single-cell epimutation rate across normal B (B01–02, B04–06) and CLL (CLL01–12) cells. Mann-Whitney U-test compared the median PDR values of healthy donor (n = 5) and CLL (n = 12) samples. (e) Cell-to-cell epimutation rate difference across normal B (B01–02, B04–06) and CLL (CLL01–12) cells. Mann-Whitney U-test compared the median absolute cell-to-cell PDR difference of healthy donor (n = 5) and CLL (n = 12) samples. (f) Single-cell epimutation rate across index-sorted normal B (B04–06) cells. Mann-Whitney U-tests. (g) Schematic of 4-gamete test procedure (see Methods). (h) Frequency of 4-gametes according to the level of average methylation of each CpG across CLL cells (CLL04 shown as a representative example, n = 29,114 low epimutation CpGs out of 1,835,994 total CpGs assessed; see also Extended Fig. 5a). Smooth local regression line is shown in red. Low epimutation CpGs are indicated in red. (i) Sequence logos of the DNA motifs significantly over-represented in low epimutation CpGs (+/−25bp) at promoters or enhancers, across CLL samples. For each motif, the E-value and the TOMTOM P-value are shown. See Methods for details on de novo motif enrichment analysis, and Extended Data Fig. 5d for additional motifs. Throughout figures, boxplots represent median, bottom and upper quartile; whiskers correspond to 1.5 x IQR.

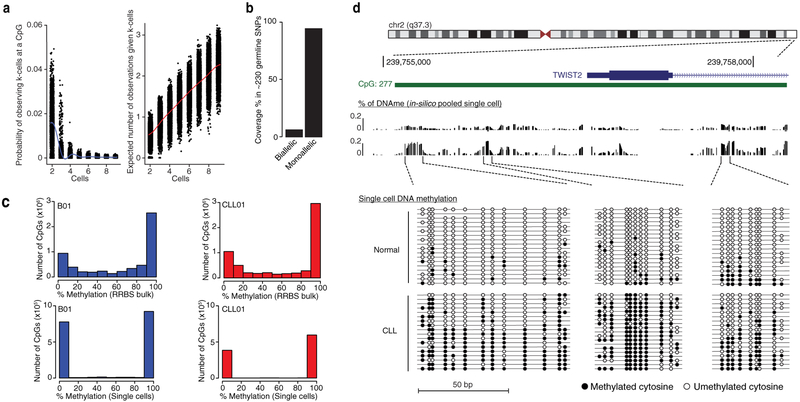

To extend the assessment of epimutation beyond DNAme concordance within single sequencing reads6,7, we measured the concordance odds ratio of DNAme between pairs of neighbouring CpGs as a function of their genomic distance (Extended Data Fig. 4a). We observed faster concordance decay in CLL at genomic regions with known regulatory roles, such as promoter CGIs, suggestive of an erosion of CGI spatial organization (Mann-Whitney U-test, P = 0.0013; Extended Data Fig. 4b). Faster concordance decay involved promoters of TP53 targets, genes differentially methylated across cancer, and genes associated with cell stemness (Extended Data Fig. 4c, e), previously reported to exhibit a high epimutation rate6, but not promoters of housekeeping genes (Extended Data Fig. 4d). Therefore, CLL epimutation also alters DNAme at larger scales10, in addition to local methylation disorder6.

While CLLs undergo stochastic diversification by epimutation, a minority of CpGs may maintain stable DNAme due to an active role in the leukemia’s regulatory code. To identify CpGs with low epimutation rate, we adapted the 4-gamete test11 to measure epimutation rate at single-CpG resolution (Fig. 1g; see Methods). As expected, the frequency of 4 gametes was positively correlated with PDR measurement of epimutation (Spearman’s rho = 0.32, P = 3.263 × 10−14). Across the 12 CLL patient samples, 166,720 CpGs exhibited a lower 4 gametes frequency than expected based on their DNAme level, representing 1.22%±0.42 (average±SEM) of assessable CpGs per sample (Fig. 1h; Extended Data Fig. 5a–c; Supplementary Table 5). Consistent with the key role of transcription factors (TFs) in DNAme patterning in CLL4, we identified gene promoter enrichment for binding motifs of TFs with established roles in CLL progression at sites surrounding low epimutation CpGs (±25bp), including NF-KB112 and MYBL113, a TF involved in c-Myc activation in lymphoid neoplasms14 (Fig. 1i, right; Extended Data Fig. 5d, e; Supplementary Table 6).

DNAme of enhancers can also impact transcriptional activity and cellular phenotypes in CLL14. Low epimutation enhancer CpGs (n = 1,585; Supplementary Table 7) were located in proximity to genes implicated in lymphoproliferation, including NOTCH1, NFATC1, and FOXC1, and genes involved in key CLL pathways (e.g., WNT and MAPK signaling pathways15; BH-FDR adjusted P < 0.2). Low epimutation enhancer CpGs were also enriched for binding sites of SP1, a component of CLL regulatory network16, and the transcriptional repressor HINFP involved in DNAme-mediated gene silencing17 (Fig. 1i, left; Extended Data Fig. 5d, e; Supplementary Table 8). This suggests that conserved CpG sites are protected from DNAme alterations by TF binding, through either direct exclusion of methylases or negative selection due to a disruption of the CLL regulatory code.

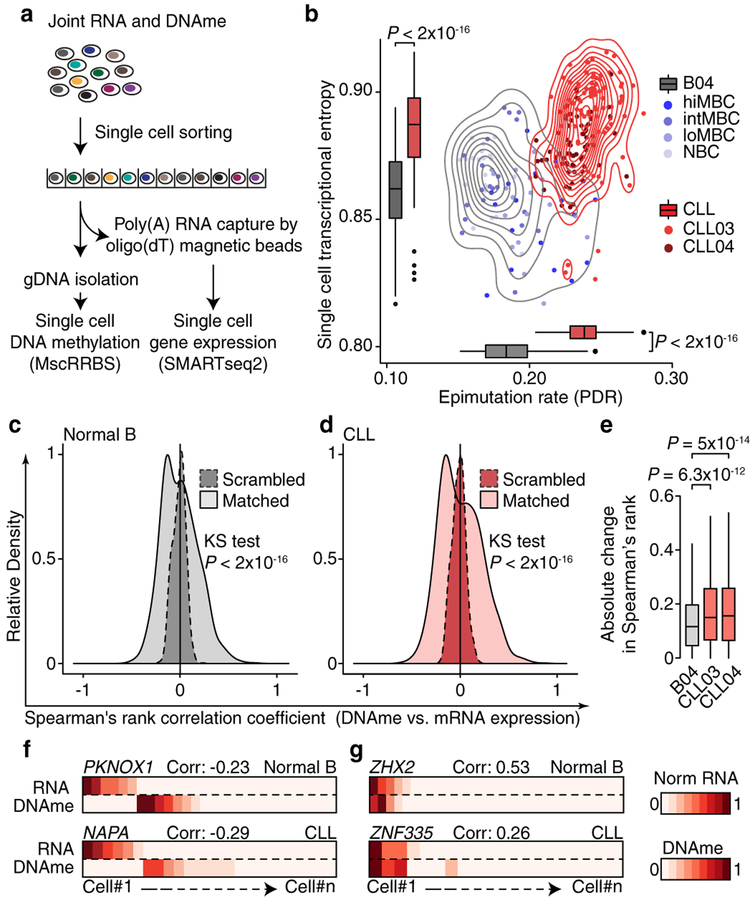

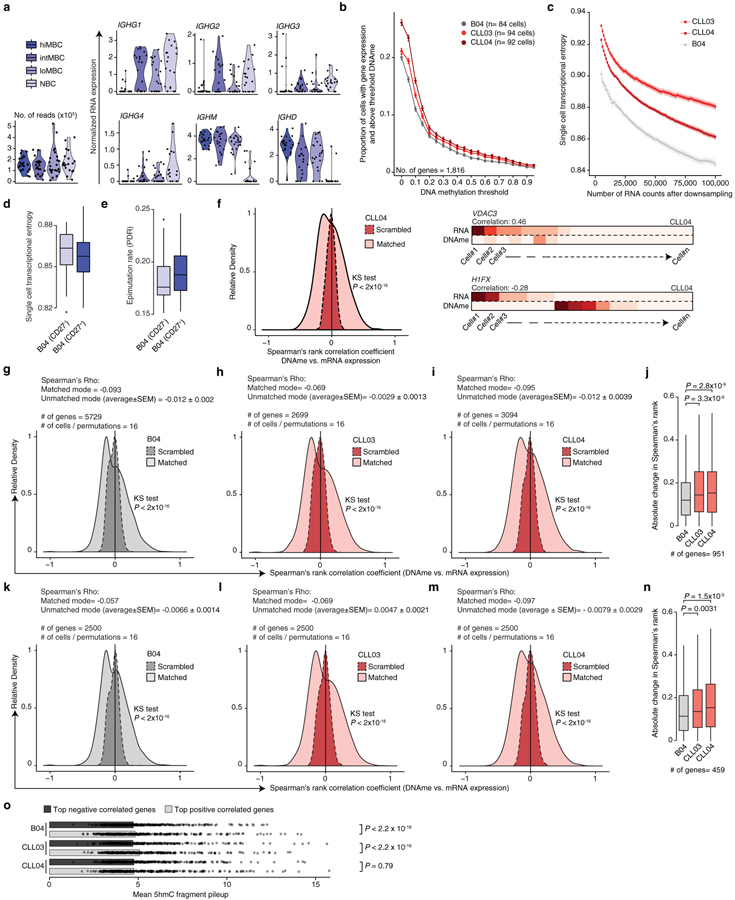

To examine the impact of epimutation on gene expression at the single-cell level, we integrated MscRRBS with whole transcriptome sequencing (Fig. 2a; Extended Data Fig. 6a). While the expected relationship between promoter DNAme and gene silencing was preserved in both CLL and normal B cells (Extended Data Fig. 6b), higher single-cell epimutation rate in CLL was associated with higher transcriptional entropy – a measure of gene expression heterogeneity within cells18 – compared to normal B samples, consistent with transcriptional dysregulation in CLL (Fig. 2b; Extended Data Fig. 6c–e). A negative correlation between promoter DNAme and gene expression was observed at single-cell level in both CLL and normal B cells (Fig. 2c, d, f; Extended Data Fig. 6f–n), but was more pronounced in CLL (Fig. 2e; Extended Data Fig. 6j, n) suggesting that, at least partly, the decreased epigenetic-transcriptional coordination observed in bulk CLL sequencing6 results from intra-leukemic epigenetic diversity. A subset of genes exhibited positive correlation between expression and promoter DNAme (Fig. 2g; Extended Data Fig. 6f, right), enriched in genes marked by cytosine hydroxymethylation, which is known to be positively correlated with gene expression19 (Extended Data Fig. 6o).

Figure 2. CLL higher epimutation rate is associated with higher transcriptional entropy consistent with transcriptional dysregulation.

(a) Schematic of the joint methylomics and transcriptomics method, applied to normal B cells (B04, n = 84) and CLL cells (CLL03, n = 94; CLL04, n = 92). (b) Single-cell transcriptome entropy19 and epimutation rate for normal B and CLL cells. Mann-Whitney U-test. See also Extended Data Fig. 6c. Distribution of Spearman’s rho of expression and promoter DNAme correlation (genes expressed >5 cells, DNAme >5 CpGs/promoter) across normal B cells (c; 3,239 genes), or CLL cells (d; CLL03, 2,699 genes). Spearman’s rho value distribution was compared to the distribution of values obtained through randomly permuted cell labels. Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. See also Extended Data Fig. 6g–n. (e) Absolute change in Spearman’s rho when comparing matched vs. permuted DNAme and RNA single-cell data in CLL and normal B cells, across 990 genes overlapping between the three samples. Wilcoxon Signed-Rank test. Representative genes with negative (f) or positive (g) single-cell expression-methylation correlation, with Spearman correlation. Scale bar represents promoter methylation and RNA read counts scaled by maximal value.

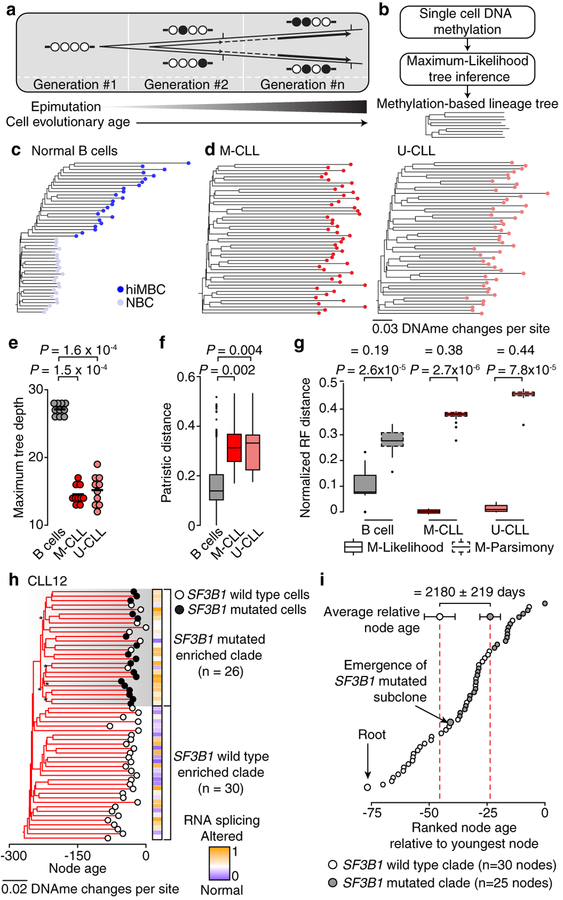

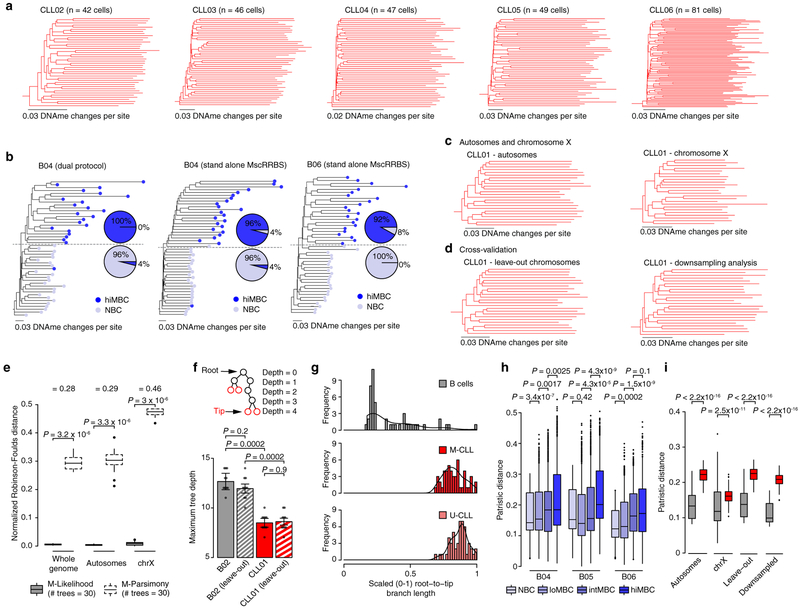

As epimutations may serve as a molecular clock9, we leveraged the heritable epimutation information to reconstruct methylation-based lineage relationships in CLL and normal B cells (Fig. 3a–d; Extended Data Fig. 7a–e; see Methods). CLL lineage trees exhibited early branching with lower maximum tree depth (Fig. 3e; Extended data Fig. 7f) and homogeneous root-to-tip branch lengths (Extended data Fig. 7g), consistent with rapid drift after the initial malignant transformation (“big bang” cancer evolutionary framework20). Moreover, the homogenous branch length is inconsistent with a significant cancer stem-cell contribution in CLL, in contrast to data that revealed highly divergent replicative histories in acute myeloid leukemia21, where cancer stem cells have been well-described. The greater CLL proliferative histories were reflected in increased epimutation accumulation resulting in higher patristic distances (i.e., sum of the lengths of branches that link two tips in a tree) compared with normal B cell trees (Fig. 3f; Extended data Fig. 7h, i). In contrast, normal B cell clades followed a pattern consistent with normal B cell differentiation by exhibiting late branching and deeper tree topology, with younger naïve CD27− B cells showing shorter branches compared with CD27+ memory terminally-differentiated B cells (Fig. 3c; Extended Data Fig. 7b). As expected, normal B cell lineage trees resulted in smaller increase in fidelity compared with parsimony trees (based on DNAme mismatches between cells; see Methods) than CLL trees, consistent with their non-clonal growth (Fig. 3g).

Figure 3. Lineage relationships inferred from single-cell DNA methylomes.

(a) Epimutation as a somatic cell molecular clock, where each division has a given likelihood of generating epimutations. (b) Schematic of methylation-based lineage tree inference (see Methods). (c and d) Representative (random cell subsampling) methylation-based lineage trees of index-sorted normal B (B05, NBC and hiMBC cells) and CLL (M-CLL [CLL07]; U-CLL [CLL10]) cells. See also Extended Data Fig. 7. (e) Maximum tree depth of lineage trees. Mann-Whitney U-test compared the maximum tree depths (one value per tree) between CLL (M-CLL [CLL07]; U-CLL [CLL10]) and normal B (B05) samples (n = 10 tree replicates; see Methods). Black lines represent averages. (f) Patristic distances between CLL and normal B cells. One representative tree of randomly sampled cells for each sample was used. Mann-Whitney U-test compared the medians of the patristic distances between healthy donor (n = 6) and CLL (M-CLL, n = 7; U-CLL, n = 5) samples. (g) Normalized Robinson-Foulds (normRF) distances between any two trees (n = 30 tree replicates; see Methods) of CLL (M-CLL [CLL07]; U-CLL [CLL10]) and normal B (B05) cells reconstructed by maximum-likelihood (ML) vs. maximum-parsimony (MP). Differences in median normRF between ML and MP are indicated on top. Mann-Whitney U-tests. (h) Methylation-based lineage tree of CLL12 with projection of SF3B1 mutation status. Asterisk indicates bootstrap values <50%. Tree was rooted by including five normal B cells as outgroup (not shown). (i) Ranked node ages relative to the youngest node in the tree in panel (h). Difference in average node ages between the SF3B1 wild type clade and SF3B1 mutated clade is shown. Node ages (estimated no. of divisions before present) are calculated by dividing node heights by a rate of 0.0005 changes per CpG site per division29 (see Methods). 21.8 divisions translate to 2,180 days at a 1% cell proliferation rate per day30. Error bars represent 95% confidence interval.

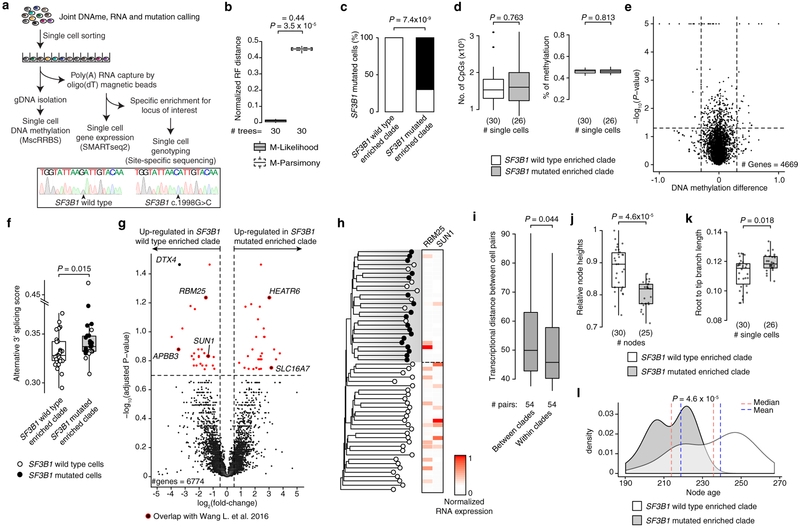

To validate tree topology inferred via epimutation, we integrated single-cell DNAme and whole transcriptome sequencing with targeted sequencing of known somatic mutations in the cDNA (Extended Data Fig. 8a). We sampled a CLL carrying a subclonal driver SF3B1 mutation (K666N; variant allele frequency of 0.23) and inferred its lineage tree from single-cell DNAme (Fig. 3h; Extended Data Fig. 8b). The SF3B1 mutated cells mapped accurately to a distinct clade inferred solely based on epimutation information (Fisher’s exact test, P = 7.4 × 10−9; Extended Data Fig. 8c, d). This accurate mapping was likely not due to distinct DNAme profiles of SF3B1 mutated cells, given the small number of differentially methylated regions (Extended Data Fig. 8e), but rather due to the ability of stochastic epimutation to trace lineage histories. Cells belonging to the SF3B1 mutated clade showed higher alternative 3’ splicing than their wild-type counterparts (Mann-Whitney U-test, P = 0.015; Extended Data Fig. 8f), consistent with the known SF3B1-mediated splicing defect22, and were marked by a distinct transcriptional profile (Extended Data Fig. 8g, h; Supplementary Table 9). We further observed decreased transcriptional similarity between cells as a function of their lineage distance, providing a direct measurement of the heritability of the transcriptional profile in a human sample (Mann-Whitney U-test, P = 0.044; Extended Data Fig. 8i). Notably, cells in the SF3B1 mutated clade showed lower node heights (i.e., sum of branch lengths of the longest downward path to a leaf from a given node; Extended Data Fig. 8j) and longer root-to-tip branch lengths compared with SF3B1 wild type clade (Extended Data Fig. 8k), consistent with SF3B1 mutation as a late subclonal event in CLL15. The molecular clock feature of epimutations further enabled timing of the subclonal divergence in the CLL’s evolutionary history, estimated to have occurred 2,180±219 days after the emergence of the parental clone (Fig. 3i; Extended Data Fig. 8l).

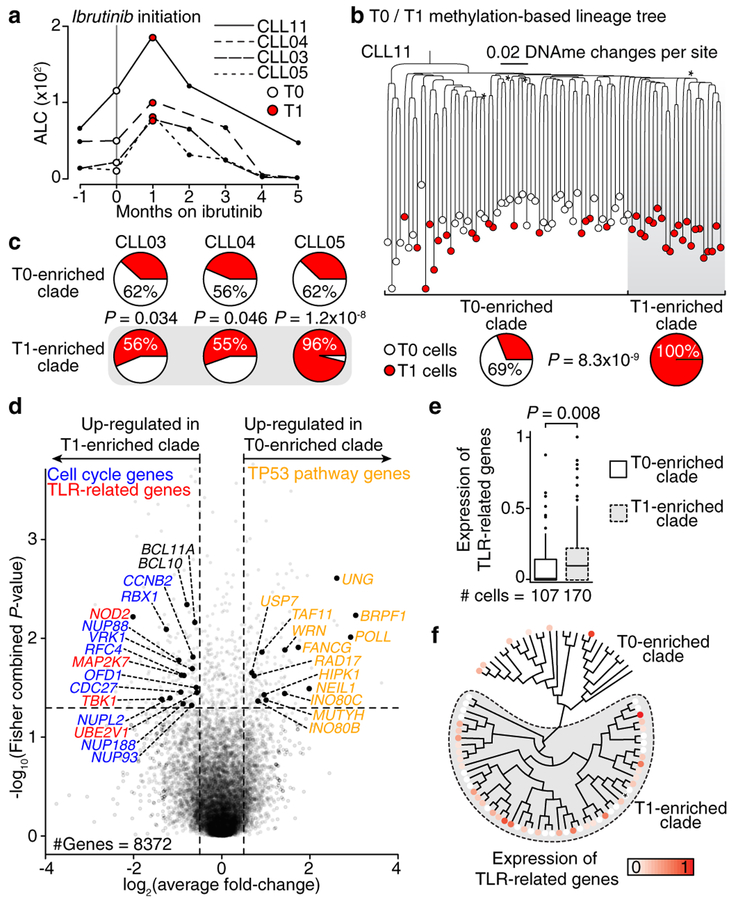

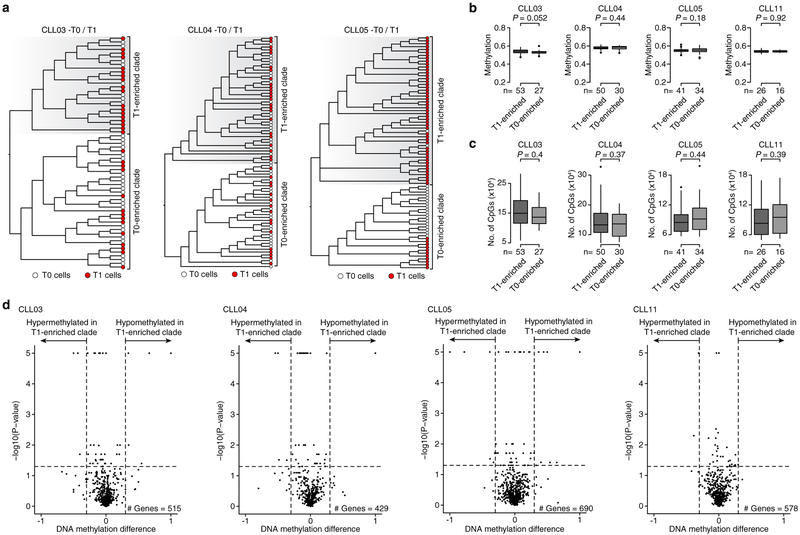

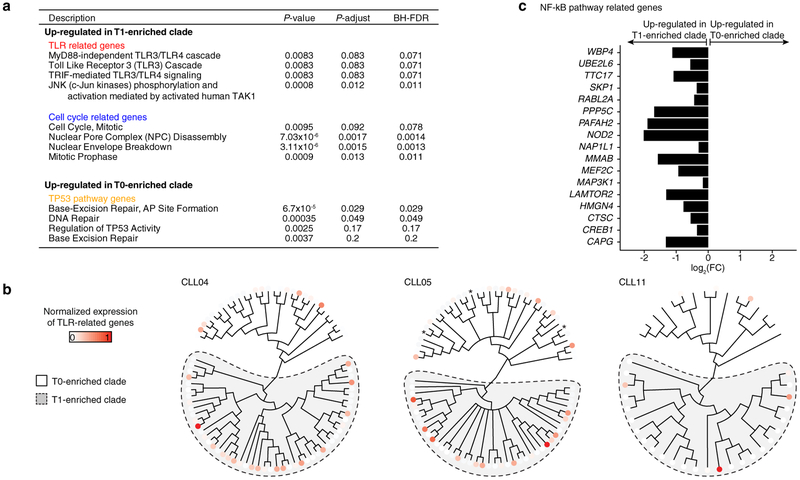

Next, we applied joint single-cell DNAme and whole transcriptome sequencing to study dynamic changes during therapy with ibrutinib – a targeted agent which abrogates B cell receptor (BCR) signaling. This therapy results in a transient rise in the peripheral blood leukemic cell burden due to forced migration of cells from the lymph node niche23. To examine potential lineage biases in ibrutinib-induced CLL migration, we profiled four CLLs, without subclonal genetic drivers, prior to (T0) and during ibrutinib-associated lymphocytosis (T1; Fig. 4a). Lineage trees integrating T0 and T1 cells identified major clades enriched for T1 cells in each of the CLLs (Fig. 4b, c; Extended Data Fig. 9a–c; see Methods), despite few DNAme differences between T1 enriched clades and other T1 cells (Extended Data Fig. 9d). These data suggest that different CLL lineages may be preferentially affected by ibrutinib and expelled from the lymph node upon treatment. Projection of transcriptomic data onto the lineage trees revealed that T1-enriched clade cells were marked by increased BCL11A expression – a proto-oncogene with expression restricted to the lymph node24, and increased BCL10 expression – an upstream regulator of NF-κB pathway in the BCR signaling cascade. Genes related to cell cycle and proliferation pathways (Fig. 4d; Extended Data Fig. 10a; Supplementary Table 10, 11) were also overexpressed in T1 enriched clades compared to other T1 cells. As the lymph node is the primary anatomical site of CLL proliferation25, these findings are consistent with the recent expulsion of cells of T1-enriched clades from the lymph node after treatment initiation. T1-enriched clades across patients were also found to have Toll-Like Receptor (TLR) pathway up-regulation (Fig. 4d–f; Extended Data Fig. 10b). The TLR pathway is known to interact with the ibrutinib-inhibited BCR signaling pathway, as has been shown in functional genomics screen for ibrutinib sensitivity26, and is specifically activated in CLL cells in the lymph node niche, triggering pro-survival NF-ĸB pathway activation27,28, which was also upregulated in T1-enriched clades (Extended Data Fig. 10c). As the abnormal activation of TLR pathway may disrupt lymph node trafficking, these results are consistent with clades enriched in ex-migrating cells, as well as suggest the potential for dual BCR and TLR inhibition, as described ex vivo27,28.

Figure 4. Joint single-cell methylomics and RNA-seq link lineage and transcriptional information in CLL evolution.

(a) Absolute lymphocyte counts for the first months on ibrutinib. Serial MscRRBS and joint MscRRBS-RNAseq was performed prior to (T0) and at one month after ibrutinib initiation (T1). (b) Top: representative lineage tree integrating pre-treatment (T0; white circles) and post-treatment (T1; red circles) cells of CLL11. Each sample is represented by 40/96 randomly sampled cells. Asterisk indicates bootstrap values <50%. Bottom: Percentage of T1 cells in each of the two clades inferred from the lineage tree. Fisher’s Exact test. (c) Same as panel (b, bottom) for CLL03, CLL04, and CLL05. Fisher’s Exact test. (d) Volcano plot of gene expression comparing T1 cells from T1 enriched clades and T1 cells from T0 enriched clades (CLL03–05, CLL11). P-values were combined across patient samples (n = 8,372 genes expressed >5 cells in ≥3 samples) using Fisher’s combined probability test. (e) Scaled average gene expression across Toll-like receptor (TLR) pathway genes from panel (d) for each T1 cell from T1 enriched clades and each T1 cell from T0 enriched clades (CLL03–05, CLL11). Mann-Whitney U-test. (f) Gene expression projections on lineage tree for TLR pathway genes from panel (d) for sample CLL03. Scale bar represents RNA read counts scaled by maximal value. Expression value projection is performed only for T1 cells, comparing T1 vs. T0 enriched clades. Asterisk indicates cell without RNA information.

Collectively, by leveraging the heritable information captured through epimutation, we retraced the evolutionary histories of CLL and charted its evolution with therapy, demonstrating how different lineages may be preferentially impacted by a therapeutic intervention, even in genetically homogenous cell populations. We foresee that future application of multi-modality single-cell sequencing will enable the annotation of intra-tumoral transcriptional disparities in response to therapy with precise lineage history information, as well as the integration of genetic, epigenetic and transcriptional information at the atomic unit of somatic evolution – the single cell.

Methods

Human subjects, sample collection and genotyping

The study was approved by the local ethics committee and by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) and conducted in accordance to the Declaration of Helsinki protocol. Blood samples were collected in EDTA blood collection tubes (BD Biosciences) from patients and healthy adult volunteers enrolled on clinical research protocols at the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center (DF/HCC) and NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center (NYP/WCMC), approved by the DF/HCC and NYP/WCMC Institutional Review Boards. We note that the IRB does not permit collection of demographic information of healthy donors. The diagnosis of CLL according to World Health Organization (WHO) criteria was confirmed in all cases by flow cytometry, or by lymph node or bone marrow biopsy. Informed consent on DF/HCC and WCMC IRB-approved protocols for genomic sequencing of patient samples was obtained prior to the initiation of sequencing studies. B cells from healthy donors and CLL patient samples were isolated from blood samples using Ficoll-Paque Plus (GE Healthcare) density gradient centrifugation and red blood cell lysis, followed by EasySep™ Human B Cell Enrichment Kit (STEMCELL Technologies, Vancouver, Canada) as per manufacturer recommendation. Immunoglobulin heavy-chain variable (IGHV) homology was determined31 (unmutated was defined as greater than or equal to 98% homology to the closest germline match). Cytogenetics were primarily evaluated by FISH analysis for the most common CLL abnormalities [del(13q), trisomy 12, del(11q), del(17p), del(6q), amp(2p)]; if FISH was unavailable, genomic data were used (Supplementary Table 12). Presence and location of recurrent somatic mutations were detected in the genes tested through Genoptix clinical grade CLL gene panel testing (Genoptix, Carlsbad, CA; Supplementary Table 13).

Multiplexed single-cell reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (MscRRBS) library construction

Single-cell methylome profiling was performed with multiplexed single-cell reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (MscRRBS), an adaption of a previous scRRBS protocol32,33 that allows to increase throughput through the addition of cell barcodes early in the scRRBS protocol. Specifically, single cell experiments were performed by sorting DAPI negative cells in 96-well plates in 3 μL of 0.1X CutSmart buffer (New England Biolabs) per well using a BD Influx sorter (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Normal B cells for sample B04, B05, and B06 were further index-sorted using the following sorting strategy: NBC (CD27−, IgM+, IgD+++), loMBC (CD27−, IgM+, IgD+), intMBC (CD27+, IgM+, IgD++) and hiMBC (CD27+, IgG+). The antibodies used were: FITC mouse anti-human IgD (clone IA6–2, BD Pharmingen), APC mouse anti-human IgG (clone G18–145, BD Biosciences), APC/Cy7 anti-human IgM (clone MHM-88, BioLegend) and PE/Cy7 anti-human CD27 antibody (clone O323, Bio Legend). Plates were then stored at −80°C until further processing. The day of the experiment, cells were lysed for 2 hours at 50°C in 1X CutSmart buffer supplemented with Proteinase K (0.2U, NEB) and Triton X-100 (0.3%, Sigma Aldrich) for a final volume of 5 μL. Proteinase K was heat-inactivated for 30 min at 75°C. DNA was incubated with 10 units of the restriction enzyme Msp1 (Fermentas) in 6.5 μL final volume reaction during 90 min at 37°C. Heat-inactivation was performed for 10 min at 70°C. Digested DNA was filled-in and A-tailed at the 3’ sticky ends in 8.5 μL final volume of 1X CutSmart with 2.5 units of Klenow fragment (Exo-, Fermentas). Reaction was supplemented with 1 mM dATP and 0.1 mM dCTP and 0.1 mM dGTP (NEB) and performed as follows in a thermocycler: 30°C for 25 min, 37°C for 25 min and heat-inactivation at 70°C for 10 min. Custom barcoded methylated adaptors (0.1 μM) were then ligated overnight at 16°C with the dA-tailed DNA fragments in the presence of 800 units of T4 DNA ligase (NEB) and 1 mM ATP (Roche) in a final volume of 11.5 μL of 1X CutSmart buffer. T4 DNA ligase heat-inactivation was performed at 70°C for 15 min the next day. Genomic DNA from 24 individual cells were pooled together according to their barcodes, giving, for a 96-well plate, 4 pools of 24 cells. Pooled genomic DNA was cleaned-up and concentrated using 1.8X SPRI beads (Agencourt AMPure XP - Beckman Coulter). Each pool was then sodium bisulfite converted (Fast Epitect Bisulfite, Qiagen) following manufacture recommendations. To ensure full bisulfite conversion, two cycles of conversion were performed. The double-stranded DNA was first denatured 10 min at 98°C and then incubated for 20 min at 60°C. 100 ng of dephosphorylated and sheared bacterial DNA was added as carrier to every pool prior to conversion. Converted DNA was then amplified using primers containing Illumina i7 and i5 index. Following Illumina pooling guidelines, a different i7 index was used for every 24-cell pool, allowing multiplexing of 96 cells for sequencing on one Illumina HiSeq lane. Library enrichment was done using KAPA HiFi Uracil+ master mix (Kapa Biosystems) and the following PCR condition was used: 98°C for 45 secs; 6 cycles of: 98°C for 20 secs, 58°C for 30 secs, 72°C for 1 min; followed by 12 cycles of: 98°C for 20 secs, 65°C for 30 secs, 72°C for 1 min. PCR was terminated by an incubation at 72°C for 5 min. Enriched libraries were cleaned-up and concentrated using 1.3X SPRI beads. DNA fragments between 200 bp and 1 Kb were size-selected and recovered after resolving on a 3% NuSieve 3:1 agarose gel. Libraries molarity concentration calculation was obtained by measuring concentration of double stranded DNA (Qubit) and quantifying the average library size (bp) using an Agilent Bioanalyzer. Every 24-cells pool was mixed with the others pool in an equimolar ratio. All cells from a 96-well plate were sequenced as paired-end on HiSeq 2500 with 10% PhiX spike-in. Negative controls (empty wells with no cell) were used to control for non-specific amplification of the libraries.

MscRRBS read alignment

Each pool of 96 cells was first demultiplexed by Illumina i7 barcodes (Supplementary Table 1), resulting in four pools of 24 cells. Each pool of 24 cells was further demultiplexed by unique cell barcodes (Supplementary Table 2). Reads were assigned to a given cell if they matched 80% of the template adapters. Adapters and adapter reverse complements (6 bp) were trimmed from the raw sequence reads. After adapter removal, reads were trimmed from their 3’ end for read quality by applying a 4 bp sliding window and removing bases until the mean base quality of the window had a Phred quality score greater than 15. Read pairs with a read shorter than 36bp after trimming were discarded. We aligned trimmed reads in single-end mode to the hg19 human genome assembly using Bismark34 (v.0.14.5; parameters: -multicore 4 -X 1000 --un –ambiguous) running on bowtie2–2.2.8 aligner35. Bismark methylation extractor (--bedgraph --comprehensive) was used to determine the methylation state of each individual CpG. For downstream analyses, a site was considered methylated or unmethylated only if there was 90% agreement of the methylation state for all reads mapped to the site. Cells with coverage of at least 50,000 unique CpGs were retained for downstream analyses (n = 2,435 cells; 92% of the total; Fig. 1b; Extended Data Fig. 1b; Supplementary Table 4), with bisulfite conversion rates of 99.8%±0.09 (median±MAD) and an average of 276,165±3,765 (average±SEM) unique CpGs per cell (Supplementary Table 4). We note that the analysis for Extended Data Fig. 2c was performed prior to the implementation of this filtering procedure to confirm that single-cell methylation values predominately equal 0 or 1, consistent with the random sampling of a single allele.

Joint MscRRBS and single-cell RNA-seq library construction

Single cells were sorted by flow cytometry, as above-described, into 2.5 μL of RLT Plus buffer (Qiagen) supplemented with 1 U/μL of RNase Inhibitor (Lucigen). Sorted cells were immediately store at −80°C. Genomic DNA (gDNA) and mRNA have been separated manually as previously described36. Briefly, a modified oligo-dT primer (5′-biotin-triethyleneglycol-AAGCAGTGGTATCAACGCAGAGTACT30VN-3′, where V is either A, C or G, and N is any base; IDT) was conjugated to streptavidin-coupled magnetic beads (Dynabeads, Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. To capture polyadenylated mRNA, we added the conjugated beads (10 μl) directly to the cell lysate and incubated them for 20 min at room temperature with mixing to prevent the beads from settling. The mRNA was then collected to the side of the well using a magnet, and the supernatant, containing the gDNA, was transferred to a fresh plate. Single-cell complementary DNA was amplified from the tubes containing the captured mRNA according to the Smart-Seq2 protocol37. After amplification and purification using 0.8X SPRI beads, 0.5ng cDNA was used for Nextera Tagmentation and library construction. Library quality and quantity were assessed using Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 and Qubit, respectively. Genomic DNA present in the pooled supernatant and wash buffer from the mRNA isolation step was concentrated on 0.8X SPRI beads and eluted directly into the reaction mixtures for Msp1 (±HaeIII) (Fermentas) enzymatic reaction (10μL final reaction). MscRRBS protocol was then performed on the digested gDNA after the restriction enzyme digestion step. To obtain higher coverage single-cell DNA methylomes, we performed double digestion with HaeIII in addition to MspI on cells from CLL11 patient sample, increasing coverage to an average of 2,298,281±86,699 (average±SEM) reads per cell, and yielding 790,951±24,098 (average±SEM) unique CpGs per cell.

Single-cell RNA-seq read-alignment and differential gene expression quantification

The sequenced read fragments were mapped against the hg19 human genome assembly using the 2pass default mode of STAR38 (version 2.5.2a) with the annotation of GENCODE39 (version 19). The number of read counts overlapping with annotated genes were quantified applying the ‘GeneCounts’ option in the STAR alignment. The single-cell transcriptomes recovered an average of 552,201±19,808 (average±SEM) reads per cell and 4,211±69 (average±SEM) genes per cell, comparable to previous stand-alone single-cell whole-transcriptome data in CLL6.

Comparison of transcriptional distances as a function of lineage distance between cell pairs was performed by first normalizing the read counts by scaling for the total number of counts per cell. We then performed principal component analysis on the log of the normalized counts and used the first three components to compute the Euclidean distance between each pair of cells (Extended Data Fig. 8i).

Differential expression analyses (Extended Data Fig. 8g and Fig. 4d) were performed using a negative binomial model with observational weights to account for zero inflation40. Specifically, we used ZINB-WaVE41 (v. 1.0.0) to estimate a set of observational weights and edgeR (v. 3.20.1) to test for differential expression using a weighted F statistic approach, as previously described42.

In Extended Data Fig. 8g, we defined differentially expressed genes by adjusting nominal P-values using a Benjamini-Hochberg FDR procedure (cut-off of adjusted P-value < 0.2), with an additional criterion of an absolute log2(fold-change) value > 0.5. In Fig. 4d, while the differentially expressed genes were examined individually for each patient (CLL03, CLL04, CLL05, and CLL11; Supplementary Table 10); they were also examined in combination across the four patients by combining the nominal P-values for the differentially expressed genes via Fisher’s combined probability test and averaging the log2(fold-change) (Supplementary Table 11). We used Fisher’s combined P-values < 0.05 and absolute log2(fold-change) > 0.5 to nominate candidate genes for subsequent gene-set enrichment analysis (see “Gene set enrichment analysis section” below). The gene set analysis was then followed by a Benjamini-Hochberg FDR adjustment, correcting the nominal P-values for multiple hypotheses testing (cut-off of adjusted P-value < 0.2). Gene expression projections of transcriptomic data onto the lineage trees for differentially expressed genes belonging to Toll-like receptor (TLR) pathways in Fig. 4f and Extended Data Fig. 10b was performed by averaging gene expression across genes for each cell. Average gene expression was subsequently scaled by the maximum expression value to bring values into a 0–1 range.

Genome annotations definitions

Promoters were defined as 1 Kb upstream and 1 Kb downstream of hg19 RefGene gene transcription start sites (TSSs), unless stated otherwise. The set of CpG Islands (CGIs) were defined using biologically-verified CGIs43. Enhancer regions were defined using FANTOM5 human robust enhancer set44. To verify the suitability of FANTOM5 human robust enhancer set in the context of CLL, we produced genome-wide maps of H3K27ac through bulk chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) of two IGHV mutated and two IGHV unmutated CLL patient samples. We observed a large overlap (72%) between FANTOM5 human robust enhancers and the CLL H3K27ac ChIP-seq peaks. In addition, 85% of the low epimutation CpGs at enhancers overlapped with CLL H3K27ac ChIP-seq peaks (1,360 out of 1,585). In Extended Data Fig. 1d, CTCF binding sites were annotated based on published CTCF binding ChIP-seq experiments generated by the ENCODE Consortium from the GM12878 lymphoblastoid cell line45. We curated a list of CTCF binding sites based on sites that were detected in at least 75% of these samples. The location of long terminal repeats (LTRs) was identified based on the RepBase database46 for hg19.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) analysis

Antibody used for ChIP included anti-H3K27ac (2 mg for 25 mg of chromatin; ab4729 Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom). A minimum of 2 million purified human CLL cells were used. Briefly, cells were fixed in a 1% methanol-free formaldehyde solution and then resuspended in sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) lysis buffer. Lysates were sonicated in an E220 focused-ultrasonicator (Covaris, Woburn, MA) to a desired fragment size distribution of 100–500 base pairs. ChIP assays were processed on a SX-8G IP-STAR Compact Automated System (Diagenode, Denville, NJ) using a direct ChIP protocol47. Briefly, immunoprecipitation reactions were performed with the above-indicated antibodies, each on approximately 500,000 cells, and incubated overnight at 4°C. The immune complex was collected with protein A/G agarose or magnetic beads and washed sequentially in the low salt wash buffer (20mM Tris pH8, 150mM NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 2mM EDTA), the high salt wash buffer (20mM Tris pH8, 500mM NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 2mM EDTA), the LiCl wash buffer (10mM Tris pH8, 250mM LiCl, 1% NP-40, 1% Sodium Deoxycholate, 1mM EDTA) and TE. Chromatin was eluted with elution buffer (1% SDS, 0.1 M NaHCO3), and then reverse cross-linked with 0.2M NaCl at 65°C for 4 hr. DNA fragments were purified using Agencourt AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA). Barcoded immunoprecipitated DNA and input DNA were prepared using the NEBNext ChIP-seq Library Prep Master Mix Set for Illumina (#E6240, New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) and TruSeq Adaptors (Illumina) according to the manufacturer’s protocol on a SX-8G IP-STAR Compact Automated System (Diagenode). Phusion High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (New England Biolabs) and TruSeq PCR Primers (Illumina, San Diego, CA) were used to amplify the libraries, which were then purified to remove adaptor dimers using AMPure XP beads and multiplexed on the HiSeq 2000 (Illumina, San Diego, CA). ChIP-seq data were processed according to the ENCODE Histone ChIP-seq Data Standards and Processing Pipeline (https://www.encodeproject.org/chip-seq/histone/). Raw reads were mapped to the human genome hg19 assembly using Burrows-Wheeler Aligner48 (BWA v0.7.17). Duplicate reads were removed using Picard (https://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/). Peaks were identified with MACS249 (v2.0.10) with a q-value threshold of 0.01. Peaks overlapping with Satellite repeat regions and Encode Blacklist were discarded.

Single-cell DNA methylation-gene expression correlation analysis

For each sample, we filtered out poor quality cells when the number of detected CpGs was below 50,000, the number of detected genes in the transcriptomes was below 2,000 or the fraction of mitochondrial or ribosomal gene counts was higher than 20% of the library size (total number of read counts). We randomly downsampled the vector of RNA read counts per cell such that the total number of read counts equated to the bottom quartile of the library size distribution for all cells in the sample (cells below this threshold were dropped). Mitochondrial genes, genes encoding ribosomal proteins, and genes with RNA-seq expression in less than 5 cells were then removed from the analysis. At single-cell resolution, a gene’s promoter methylation rate was represented by the proportion of methylated CpGs in the region 1 Kb upstream/downstream of the transcription start site. Genes with less than 5 CpG observations in the promoter region were excluded. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient between expression and promoter methylation rate was then calculated across available cells for each gene. The observed Spearman’s rho was validated by a non-parametric permutation test, in which we compared the correlation of promoter DNAme with gene expression against a null distribution obtained by randomly permuting cell labels for the methylation values (such that RNA and DNAme are no longer linked at the single-cell level) and then computing the Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (n = 26 permutations for normal B sample [B04] and n = 16 permutations for CLL samples [CLL03 and CLL04] were used to obtain comparable numbers of genes between samples; see Fig. 2c, d; Extended Data Fig. 6f). We note that the same result was obtained when equalizing number of permutations (n = 16) and/or number of genes (n = 2,500) between samples in the analysis (see Extended Data Fig. 6g–n).

Single-cell transcriptional entropy analysis

Transcriptional entropy in Fig. 2b and Extended Data Fig. 6c–d was computed as previously described18. Briefly, for a given cell we divide each element of the downsampled vector of gene expression counts by the cell’s library size to obtain the corresponding proportion of overall expression attributable to each gene. These gene proportions were used to compute Shannon’s information entropy for each cell using the standard formula:

Where S is Shannon’s information entropy, and Pi is the proportion of overall expression attributable to gene i within that single cell. This value was subsequently scaled by the maximum obtainable entropy to bring each value into a 0–1 range. We note that the analyses in Fig. 2b and Extended Data Fig. 6d were performed with downsampling to create a balanced dataset by matching the total number of RNA read counts for all cells in each sample (n = 50,000 reads per cell).

Gene set enrichment analysis

Gene set enrichment analysis was limited to the Molecular Signature Database50 (MSigDB; http://www.broad.mit.edu/gsea/) CGP (expression signatures of genetic and chemical perturbations) and CP (canonical pathways derived from KEGG, Reactome, and BIOCARTA) curated gene set collections. In Fig. 4d, genes with a Fisher’s combined P-value < 0.05 and absolute log2(fold-change) > 0.5 were used for the subsequent gene-set enrichment analysis (n = 336). A hypergeometric test was used to measure the enrichment of these genes in each gene-set, followed by a Benjamini-Hochberg FDR procedure (cut-off of adjusted P-value < 0.2).

PDR (Proportion of Discordant Reads) analysis

Epimutation rates are quantified by assessing the concordance of adjacent CpGs within the same sequencing read (both methylated and unmethylated CpGs on a single sequencing read) and are measured with MscRRBS as the proportion of discordant reads per cell (single-cell PDR) as previously described6, with minor modifications. Briefly, at each CpG, PDR is equal to the number of discordant reads (reads containing both methylated and unmethylated sites) divided by the total number of reads. To calculate PDR for each individual cell, all reads with greater than 4 CpGs were evaluated for discordance, and the sum of discordant reads was divided by total number of reads with greater than 4 CpGs within that cell. To determine region-specific PDR, each cell’s reads were intersected with the genomic coordinates of the region of interest before PDR calculation. To compute cell-to-cell PDR differences, pairs of cells were randomly sampled without replacement and the absolute difference between the two cells was measured. This procedure was repeated until all pairs of cells within a sample were exhausted. We note that for analyses in Fig. 1d–e, we excluded 175 cells (6.5%) with a bisulfite conversion rate < 0.99, to remove incomplete conversion as a technical source of epimutation, from the total of 1,721 cells profiled with stand-alone MscRRBS (see Extended Data Fig. 1b). In addition, we also excluded cells from sample B03, as these are CD19+CD27− index-sorted B cells.

To exclude technical artifacts as a potential cause of lower PDR dispersion in CLL compared with normal B cells, a multivariable generalized linear model (GLM) regression analysis was performed, confirming that the observed low cell-to-cell epimutation rate variability was strongly associated with CLL vs. normal B cell status. Cell-to-cell PDR difference was used as dependent variable. Number of unique CpGs, bisulfite conversation rate, number of reads, and cell type status (CLL vs. normal B cells) were used as explanatory variables. P-values for the GLM coefficients (Student’s t-test) of less than 0.05 were considered significant (Extended Data Fig. 3e).

Concordance Odds Ratio (COR) analysis

We present a CpG auto-correlation metric called COR, referring to the Concordance Odds Ratio (COR). CpG observation (CpG_a) is considered concordant with another CpG observation (CpG_b) at genomic base pair (bp) distance, d, away if both CpG_a and CpG_b are methylated, or both are unmethylated, otherwise they are labeled as discordant. The COR at each base pair distance d is the quotient between the concordance empirical likelihood at d and the background concordance empirical likelihood. For a given distance d, all pairs of CpGs covered in a single cell i that are separated by d base pairs are obtained. The COR for distance d in a given single cell i is then computed by measuring the ratio of concordant pairs separated by distance d out of all pairs of CpGs that are at a distance d and dividing it by the expected background ratio of concordance determined by average methylation in the given genomic region of interest in cell i (e.g., CGI, see formula in Extended Data Fig. 4a). This provides a vector for cell i of COR values as a function of d, in the range 100bp (i.e., beyond the length of a single sequencing read) to 1000bp for the region of interest. Due to differences in length of the assessed genomic regions of interest, we corrected for the length of these genomic regions by dividing each genomic location into equal-sized bins and averaged the COR values within each bin. For visualization clarity, COR values were subsequently scaled to bring all values into the range [0,1]. We then fitted a linear curve to this vector of COR by d and computed the slope as a measure of concordance decay for each independent cell. All cells belonging to CLL01-CLL12 and B01-B06 samples profiled with MscRRBS were used in the analysis. Finally, P-values were computed for two-tailed Mann-Whitney U-test by comparing the average rate of decay in COR of healthy donor samples (n = 6) with the average rate of decay in COR of CLL samples (n = 12), to test whether CLL samples lose DNA methylation concordance at a different rate compared with healthy donor samples.

4-gamete analysis

We present a CpG epimutation metric based on the four-gamete test11. We will refer to this metric as four gamete (4G). This test relies on the fact that detecting four gametes defies the assumptions of the infinite site mutation model51 and therefore is likely to reflect a high epimutation rate. Moreover, this test allows to estimate epimutation rate at single CpG site resolution in CpG-sparse regions, such as enhancers, in contrast to methods that rely on capturing multiple CpGs on the same read6,7. For each sample (CLL01-CLL12 were used in the analysis), the number of gametes between two CpGs, CpG_a, and CpG_b, was determined by counting how many of the four possible combinations of methylation and unmethylation were observed across all cells in a given sample where both CpG_a and CpG_b were obtained. This process was repeated by pairing each individual CpG_a with all CpGs further than 100bp away (to exclude CpGs contained within a single sequencing read) and enumerated the number of gametes observed in each pair of sites in all cells. A binary mask was applied to the resulting counts to exclude the pairing of a site with itself. After all pairings, as a measure of CpG epimutation, we computed the frequency of observing four gametes at CpG_a by dividing the number of observed pairs with four gametes by the total number of pairings. As the direct implementation of such an algorithm has time complexity of O(m*n2), where m is the number of cells and n is the number of sites, the number of pairings analyzed for each CpG was randomly downsampled by a 100x factor to speed up the calculation. To validate this approach, five runs with random 100-fold downsampling were performed for the same dataset and the frequencies of observing four gametes were compared. The results were highly concordant (Pearson correlation coefficient r = 0.93), supporting the validity of this approach. Notably, by pairing individual CpGs to all other CpGs across the genome, 4G enabled the determination of epimutation rate even for CpGs that are not in close genomic proximity to other CpGs, which is required for methods such as PDR and epigenetic polymorphism for calculation of epimutation6,7. We note that the assumption of independence between CpGs in the 4-gamete test is likely valid here, as MscRRBS captures ~10% of the targeted methylome per single-cell due to the sparsity of the single-cell data. Therefore, the 4-gamete test is based on a nearly unique combination of CpGs/cells for each CpG pairing. Only CpG sites covered by at least 5 cells in each sample were used in the analysis (range [156,662–2,371,498] CpGs/sample). Within each sample (CLL01-CLL12), CpG sites with lower 4G rate than expected based on their methylation level (i.e., low epimutation CpGs) were defined as being 1.5*median absolute deviation (MAD) away from the median frequency of four gametes in each DNAme window size of 0.05 [from 0.1 to 0.9]. A total of 166,720 unique CpGs across all the 12 CLL patient samples (average of 1.22%±0.42 [average±SEM]; range [0.04–2.9%]) exhibited a lower frequency of four gametes than expected based on their DNAme level and were used for downstream analyses.

BEDTools52 v2.25.0 was used to calculate overlaps between low epimutation CpGs and gene promoters or FANTOM5 human enhancers44. De novo motif enrichment analyses were performed using MEME-ChIP53 against JASPAR CORE vertebrates and UniPROBE Mouse databases (-order 2, -meme-minw 6, -meme-maxw 15, -meme-nmotifs 5, -dreme-e 0.05, -meme-mod zoops). Specifically, we performed a discriminative motif discovery to find motifs within gene promoters or enhancers that were over-represented at sites surrounding low epimutation CpGs (±25bp around CpG) relative to a control set consisting of randomly selected CpGs (±25bp around CpG), matched for methylation values and cell coverage to the low epimutation CpGs. To further control for possible CpG content biases (e.g., as MspI cut site is CĈGG), a 2-order background model was used to normalize for biased distribution of trimer nucleotides in our sequences. Only motifs with an E-value ≤ 0.05 were reported, and each motif was then matched to its most similar motif in the TOMTOM database54 or literature if available. The E-value is an estimate of the expected number of motifs with the given log-likelihood ratio (or higher), and with the same width and site count, that one would find in a similarly sized set of random sequences53. We also report the TOMTOM P-value, defined as probability that a random motif of the same width as the target would have an optimal alignment with a match score as good or better than the target’s53.

Lineage tree inference and support values

Since epimutations mark cell divisions9, the heritable DNAme information captured through MscRRBS can inform the reconstruction of cellular lineages. Indeed, given that the maintenance methylation machinery has an error rate estimated to be four orders of magnitude higher than that observed for DNA replication55,56, the phylogenetic information content of single-cell DNAme data is higher than that of single-cell nucleotide variants. Moreover, while single-cell copy number variations (CNVs)57,58, IGH transcript sequences59, somatic microsatellite21 and mitochondrial DNA60,61 mutations allow for the reconstruction of cancer lineages, they may have limited resolution given the smaller number of events that can be detected with current single-cell sequencing approaches, limited applicability across cancer types, or have not been adapted for large scale multi-modality single-cell sequencing. Specifically, CNVs are not applicable to cancers, such as CLL, without significant copy number variations. We therefore generated methylation-based lineage trees by applying a tree searching maximum-likelihood (ML) algorithm based on binary methylation values. We used the MPI version of IQ-TREE62 v1.5.3, which exhibits improved performance compared to other ML fast phylogenetic programs in identifying trees of higher likelihood scores63. We selected a substitution model based on the binary alignment, inferred a maximum-likelihood tree, and computed bootstrap support values (1,000 bootstrap replicates). We opted for the new model selection procedure64 (-m TESTNEW), which additionally implements the FreeRate heterogeneity model inferring the site rates directly from the data (mixture of 4G and technical errors permitted in phylogeny reconstruction) instead of being drawn from a gamma distribution65. General time reversible model ‘GTR2’ consistently outperformed the other model tested (Jukes-Cantor type model) for our methylation binary data. IQ-TREE also incorporates an approach for calculating ultrafast bootstraps (UFBoot)66. We complemented UFBoot analysis with the Shimodaira–Hasegawa-like (SH-like) approximate likelihood ratio test (SH-aLRT) and the approximate Bayes test to further assess support for single branches. Briefly, we initialized different tree search runs per batch of cells, each with a different random starting seed. In each run, a maximum-parsimony tree is first constructed directly from the alignment (methylation state mismatches between cells). Then, parameters of the given binary substitution models are estimated based on the maximum-parsimony tree. The log-likelihoods of this initial maximum-parsimony tree are computed for the many different given models along with the Akaike information criterion (AIC), corrected Akaike information criterion (AICc), and the Bayesian information criterion (BIC). The model that minimizes the BIC score (the best-fit model) is then selected. The estimated model parameters are now used for initializing candidate tree set and further maximum-likelihood optimizations through an iterative, “hill-climbing” optimization technique. Maximum-likelihood tree search starts by generating 100 trees. From these 100 trees, all unique topologies are collected, and their approximate likelihoods computed. From the ranked list of maximum-likelihood values, the top 20 trees are selected and NNI are performed on each tree to obtain the locally optimal maximum-likelihood trees. The top five topologies with highest likelihood (the candidate tree set) are then retained for further maximum-likelihood optimizations. An important weakness of pure hill-climbing methods is that they can be easily trapped in local optima. The locally optimal trees in the candidate tree set are, thus, randomly perturbed to allow to escape from local optima. IQ-TREE keeps the best maximum-likelihood tree while it searches the tree parameter space and stops searching after going through a user-defined number of trees. We extended this number to 1,000 trees to better explore tree parameter space. The final optimized best maximum-likelihood tree is then printed in NEWICK format. Trees were visualized with FigTree v1.4.3 (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/).

Lineage tree structures were validated through cross-validation by restricting phylogeny reconstruction to only autosomes or chromosome X, holding-out chromosomes (three at a time), or downsampling the number of CpGs per cell to equal numbers, confirming the robustness of the lineage tree inference (Extended data Fig. 7). The inferred lineage trees were also found to be >3-fold more robust than maximum-parsimony-based reconstruction trees (Extended Data Fig. 7e), confirming that the lineage tree structure adds new information to the simple comparison of the DNAme profiles. Indeed, the haploid X chromosome in male patient samples showed an even greater robustness when compared with maximum-parsimony trees, likely due to the removal of the confounding random sampling of the two alleles in autosomes.

Methylation-based lineage trees integrating pre-treatment (T0) and post-treatment (T1) cells for CLL03, CLL04, CLL05, and CLL11 patient samples from joint MscRRBS and single-cell RNA-seq were reconstructed by maximum-likelihood, followed by ultra-fast bootstrapping branch support analysis with 1,000 replicates (Fig. 4b; Extended Data Fig. 9a). T1 enriched clades were defined based on clades occurring after the first major split in the lineage tree. Differential expression was compared between T1 cells that map to the T1 enriched clades and T1 cells that map to the T0 enriched clades. We further matched the cells belonging to the T1-enriched clade identified from these T0-T1 lineage trees, by integrating the two groups of T1 cells into a maximum-likelihood tree search and computing bootstrapping branch support analysis with 1,000 replicates, as described above. In Extended Data Fig. 8e and Extended Data Fig. 9d, we defined genes with an absolute weighted average DNAme difference > 0.3 and a two-sided non-parametric permutation test P-value < 0.05 as differentially methylated.

Maximum tree depths – defined as number of nodes along the longest path from the root node down to the farthest leaf – of lineage trees of CLL and normal B cells were computed by initializing ten independent tree search replicates per batch of randomly sampled 50 cells, each with a different random starting seed. Patristic distances – defined as the sum of the lengths of the branches that link two tips in a given tree – between CLL and normal B cells were computed by analyzing one representative methylation-based lineage tree of randomly sampled cells for each sample. To compare between inferred lineage trees, we computed the pairwise Robinson-Foulds (RF) distance – a measure of tree structure similarity between two given trees67 – between them. Specifically, thirty independent tree search replicates per batch of randomly sampled 50 cells were initialized, each with a different random starting seed. To compute the RF distances, pairs of trees were then randomly sampled without replacement and the RF distance between the two trees computed. The RF distances were normalized by the total number of internal edges in respective pairs of trees (normalized RF distance). Node ages – estimated no. of divisions before present – were calculated by dividing node height (defined as the length of the longest downward path to a leaf from a given node) values by a rate of 0.0005 changes per CpG site per division29.

Statistical methods

Statistical analysis was performed with Python 2.7.13 and R version 3.4.2. Categorical variables were compared using the Fisher’s Exact test. Continuous variables were compared using the Mann-Whitney U-test, Welch’s t-test, Wilcoxon Signed Rank test, non-parametric permutation test or Kolmogorov–Smirnov test as appropriate. P-values were adjusted for multiple comparisons by Bonferroni FWER or Benjamini-Hochberg FDR adjustment procedure, as appropriate. All P-values are two-sided and considered significant at the 0.05 level unless otherwise noted.

Data Availability

MscRRBS and single-cell Smart-seq2 datasets have been deposited to the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) under accession number GSE109085. ChIP-seq datasets have been deposited to the NCBI GEO under accession number GSE119103. Additional supplementary data is available upon request.

Supplementary Material

Extended Data

Extended Data Figure 1. MscRRBS is an accurate and reproducible method for single-cell DNAme analysis.

(a) Detailed schematic of multiplexed single-cell RRBS (MscRRBS) protocol. (b) Extended summary table of healthy donors and CLL patient samples used in this study. (c) Representative size distribution of the MscRRBS libraries assessed by Agilent Bioanalyzer before and after primer dimers removal. The DNA fragment size in MscRRBS libraries is typically 200–1000 bp, with some visible peaks corresponding to the MspI fragments for repeat elements, and primer dimer contaminants (~170 bp). (d) Number of CpGs observed in MscRRBS libraries across relevant genomic regions comparing MscRRBS (left) and bulk RRBS (right) assays for normal B (B01) and CLL (CLL01) cells. The enrichment in exons, promoters and CpG islands (CGIs) observed in MscRRBS libraries corresponded to ~40% of the total sequenced CpGs, akin to bulk RRBS assays. (e) Downsampling analysis showing that ~1.7 million paired-end reads per cell provided ~85% of unique CpGs with further sequencing resulting in a marginal increase in coverage. (f) Correlation of average CpG methylation across in silico merged single cells and bulk RRBS obtained from matched samples for normal B (B01, n = 40,257 CpGs) and CLL (CLL01, n = 9,578 CpGs) cells. P-values are indicated for two-sided Pearson’s correlation test. (g) Pooling individual single cells together rapidly increases the number of CpGs recovered, approaching bulk RRBS coverage with >48 cells. The percentage of CpG sites detected in single cell data (blue and red for normal B cells and CLL cells, respectively), the in vitro pooled single-cell datasets (light blue and light red, respectively) and matched bulk RRBS libraries (striped bars) is shown. Error bars represent 95% confidence interval. (h) Same as panel (g) for average CpG DNA methylation. Single, pooled cells and bulk RRBS showed a similar CpG methylation percentage, suggesting measured genome-wide DNAme profiles of individual cells accurately recapitulate bulk methylation profiles in the same cell type.

Extended Data Figure 2. Single-cell DNA methylation coverage analysis.

(a) The ~10% sampling of the MscRRBS DNA methylome leads to intersection decrease of individual CpGs across cells. Left: expected number of times of observing a given CpG across all k cells, (matching k indicated in the x-axis value). Right: expected number of measured CpGs given k-cells. (b) Biallelic coverage within a given single cell was detected in only 4.6±2% of ~230 germline SNPs available for analysis, suggesting that the observed single-cell CpG data largely represents only one of the two alleles of the near-diploid CLL genome. (c) Histograms of the distribution of CpG methylation values for single normal B (blue) and CLL (red) cells and matched bulk RRBS libraries showing highly-digitized pattern of DNAme in single cells (i.e., CpG sites either methylated or unmethylated) in contrast to bulk RRBS which shows intermediate DNAme values. (d) Representative analysis for three non-contiguous genomic windows around the promoter region of Twist2, previously shown to be implicated in CLL pathogenesis68. Shown from top to bottom are the annotation of the Twist2 promoter locus with CGI sites indicated (green); the estimated methylation rate of in-silico pooled single cells for healthy donors and CLL; and the CpG methylation patterns (black circles: methylated; white circles: unmethylated) of single cells. Note the higher level of DNAme percentage in CLL compared with healthy donor cells at these selected regions.

Extended Data Figure 3. CLL epigenomes show elevated epimutation rate across all genomic regions, with low cell-to-cell variability in epimutation rates.

(a) Representative analysis of the WT1 locus. CpG island is indicated in green, along with the CpG methylation patterns (black circles: methylated; white circles: unmethylated) in single cells. We note that CLL cells exhibit lower cell-to-cell variation in epimutation rate compared with normal B cells. (b) Comparison of cell-to-cell epimutation rate difference per genomic region between CLL (M-CLL [CLL01-CLL07], n = 309 pairs; U-CLL [CLL08-CLL12], n = 218 pairs) and normal B (B01-B06, n = 333 pairs) cells. P-values were computed for two-sided Mann-Whitney U-test by comparing the median cell-to-cell PDR differences of healthy donor samples (n = 5) with the median cell-to-cell PDR differences of CLL samples (n = 12) for each genomic region, followed by a Bonferroni adjustment procedure. (c) Difference in average CpG methylation per genomic region between CLL (n = 12) and normal B (n = 6) samples (CLL01-CLL12 [M-CLL, n = 619 cells; U-CLL, n = 436 cells] and B01-B06 [n = 666 cells]). (d) Percentage of CpG methylation change at CpG islands (CGI) when comparing DNAme level of individual cells in each sample to baseline (defined as the average DNAme level across all samples) for CLL and normal B cells (CLL01-CLL12 [M-CLL, n = 619 cells; U-CLL, n = 436 cells] and B01-B06 [n = 666 cells]). (e) Multivariable linear regression model that account for potential technical confounders (bisulfite conversion rate, number of aligned reads, number of covered CpGs). CLL01-CLL12 (M-CLL, n = 619 cells; U-CLL, n = 436 cells) and B01-B06 (n = 666 cells) samples were used in the analysis. (f) Single-cell epimutation rate across index-sorted normal B cells (B04, n = 96 cells; B05, n = 96 cells; B06 = 92 cells). P-values are indicated for two-sided Mann-Whitney U-tests. (g) Same as panel (f) for cell-to-cell epimutation difference (B04, n = 48 pairs; B05, n = 48 pairs; B06 = 46 pairs). P-values are indicated for two-sided Mann-Whitney U-tests. (h) Direct comparison of cell-to-cell epimutation difference between CLL (M-CLL [CLL01-CLL07], n = 309 pairs; U-CLL [CLL08-CLL12], n = 218 pairs) and index-sorted B cells (B04-B06; NBC, n = 35 pairs; loMBC, n = 35 pairs; intMBC, n = 35 pairs; hiMBC, n = 35 pairs). P-values are indicated for two-sided Mann-Whitney U-tests. Throughout the figure, boxplots represent median and bottom and upper quartile; lower and upper whiskers correspond to 1.5 x IQR. Error bars represent 95% confidence interval.

Extended Data Figure 4. Long-range DNA methylation concordance decay.

(a) Concordance odds ratio (COR) of DNA methylation state between any two neighbouring CpGs as function of their genomic distance (see Methods for details). (b) Left: Scaled COR (0–1) for CpG islands at transcription start sites (CGI at TSS; B01 and CLL01 samples are shown as a representative example). Right: average rate of decay (slope of the first order fit line) in COR for normal B (n = 6) and CLL (n = 12) samples for CGI at TSS (B01-B06 [n = 666 cells; n = 48,065,000 CpGs] and CLL01-CLL12 [M-CLL, n = 619 cells, n = 38,968,846 CpGs; U-CLL, n = 436 cells, n = 37,464,310 CpGs]). P-value was computed for two-sided Mann-Whitney U-test by comparing the average rate of decay in COR of healthy donor samples (n = 6) with the average rate of decay in COR of CLL samples (n = 12). (c) Same as panel (b) for CGI at TSS of genes belonging to the TP53 gene set69. Normal B cells, n = 666 cells, n = 6,308,174 CpGs; M-CLL, n = 619 cells, n = 5,113,493 CpGs; U-CLL, n = 436 cells, n = 4,982,039 CpGs. P-value was computed for two-sided Mann-Whitney U-test by comparing the average rate of decay in COR of healthy donor samples (n = 6) with the average rate of decay in COR of CLL samples (n = 12). (d) Same as panel (b) for CGI at TSS of housekeeping genes70. Normal B cells, n = 666 cells, n = 2,087,432 CpGs; M-CLL, n = 619 cells, n = 1,686,295 CpGs; U-CLL, n = 436 cells, n = 1,620,802 CpGs. P-value was computed for two-sided Mann-Whitney U-test by comparing the average rate of decay in COR of healthy donor samples (n = 6) with the average rate of decay in COR of CLL samples (n = 12). (e) Average rate of decay in COR for normal B (n = 6) and CLL (n = 12) samples for CGI at TSS of genes belonging to gene sets previously reported to be affected by high epimutation rate6. Normal B cells, n = 666 cells, n = 48,065,000 CpGs; M-CLL, n = 619 cells, n = 38,968,846 CpGs; U-CLL, n = 436 cells, n = 37,464,310 CpGs. P-value was computed for two-sided Mann-Whitney U-test by comparing the average rate of decay in COR of healthy donor samples (n = 6) with the average rate of decay in COR of CLL samples (n = 12). Throughout the figure, error bars represent 95% confidence interval.

Extended Data Figure 5. Epimutations at single CpG resolution.

(a) Frequency of 4-gametes according to the level of average methylation of each individual CpG site in each CLL sample (CLL01-CLL12; randomly sampled CpGs shown out of the total CpGs assessed in each CLL sample; range [156,662–2,371,498] CpGs/sample covered in >5 cells in each sample). Smooth local regression line (LOESS) is shown in red. (b) Low epimutation (loEpi) CpGs are defined as being 1.5*median absolute deviation (MAD) away from the median frequency of 4-gametes in each DNAme window of 0.05 [0.1–0.9] for a given sample. Shown is a representative example of this procedure for DNAme window of [0.5–0.55] in CLL04 patient sample. (c) Percentage of loEpi CpGs (average of 1.22%±0.42 [average±SEM]; range [0.04–2.9%]) out of the total CpGs assessed in each CLL sample. CLL01, n = 14,711 loEpi CpGs; CLL02, n = 2,573 loEpi CpGs; CLL013, n = 25,270 loEpi CpGs; CLL04, n = 29,114 loEpi CpGs; CLL05, n = 16,603 loEpi CpGs; CLL06, n = 11,413 loEpi CpGs; CLL07, n = 19,330 loEpi CpGs; CLL08, n = 19,916 loEpi CpGs; CLL09, n = 11,440 loEpi CpGs; CLL10, n = 18,614 loEpi CpGs; CLL11, n = 7,067 loEpi CpGs; CLL12, n = 308 loEpi CpGs. (d) Additional sequence logos of the DNA motifs determined to be significantly over-represented in low epimutation CpGs (+/− 25bp around CpGs at promoters [TSS +/− 1 Kb] or at enhancers) across all CLL samples. For each motif, the E-value and the TOMTOM P-value are shown. See Methods for details on the de novo motif enrichment analysis and the statistical tests used. (e) Median protein expression (log10 normalized iBAQ intensity) of transcription factors for which motifs were enriched in regions with low epimutation CpGs, confirming that the identified TFs are expressed at the protein level in B-lymphocytes and/or hematopoietic compartments. Error bars represent 95% confidence interval. All available human proteome data from lymphoid/hematopoietic lineages are displayed71.

Extended Data Figure 6. Methylation-transcription relationships at the single-cell level.

(a) Number of reads (left) and expression of Immunoglobulin Heavy Chain (IGH) genes (right) in index-sorted B cells validating our index-sorting strategy (CD27−IgM+IgD+++IgG− [NBC, n = 24 cells], CD27−IgM+IgD+IgG− [loMBC, n = 24 cells], CD27+IgM+IgD++IgG− [intMBC, n = 24 cells], and CD27+IgG+ [hiMBC, n = 23 cells]). Violin plots represent kernel density estimation showing the distribution shape of the data. (b) Proportion of cells with gene expression (read count > 0) and exhibiting above-threshold DNAme. Full circles (and whiskers) represent the mean (±SEM) proportion across all genes with sufficient RNA (expression seen in > 5 cells) and DNAme (> 5 CpGs per promoter) information across the three samples (n = 1,816 genes). (c) Mean (±SEM) across cells of transcriptional entropy (see Methods) showing higher transcriptome entropy in CLL (CLL03, n = 94; CLL04, n = 92) compared with normal B cells (B04, n = 84) across various downsampling regimes (range [5,000–100,000]; step-size of 1,000). (d and e) Single-cell transcriptional entropy (d) and epimutation rate (e) between normal CD27− B (NBC and loMBC) and CD27+ B (intMBC and hiMBC) cells. (f) Left: distribution of the Spearman’s rho between expression and promoter DNAme rate (n = 3,094 genes with sufficient RNA [expression seen in > 5 cells] and DNAme [> 5 CpGs per promoter] information) in CLL04. The observed spearman’s rho values were compared to values obtained by randomly permuting cell labels for the methylation values (see Methods). P-value is indicated for two-sided Kolmogorov–Smirnov (KS) test. Right: heatmaps of spearman’s rank-order correlation for representative genes with positive or negative single-cell expression-methylation correlation. Scale bar represents promoter methylation and RNA read counts scaled by maximal value. (g) Same as panel (f) for individual normal B cells (n = 5,729 genes; n = 16 permutations; see Methods for details). (h) Same as panel (g) for CLL03 (n = 2,699 genes; n = 16 permutations). (i) Same as panel (g) for CLL04 (n = 3,094 genes; n = 16 permutations). (j) Absolute change in Spearman’s rho when comparing matched vs. scrambled DNAme and RNA single-cell data in CLL (CLL03 and CLL04) and normal B (B04) cells. From the pool of genes used in panel (g-i), only overlapping genes (n = 951) across the three samples were used in the comparison. P-values are indicated for two-sided Wilcoxon Signed Rank test. (k) Same as panel (f) for individual normal B cells (n = 2,500 most variable genes with sufficient RNA [expression seen in > 5 cells] and DNAme [> 5 CpGs per promoter] information; n = 16 permutations; see Methods for details). (l) Same as panel (k) for CLL03. (m) Same as panel (k) for CLL04. (n) Absolute change in Spearman’s rho when comparing matched vs. scrambled DNAme and RNA single-cell data in CLL (CLL03 and CLL04) and normal B (B04) cells. From the pool of genes used in panel (k-m), only overlapping genes (n = 459) across the three samples were used in the comparison. P-values are indicated for two-sided Wilcoxon Signed Rank test. (o) Mean (±SEM) hydroxymethylation (5-hmC) level at genes with positive correlation between expression and promoter DNA methylation (top correlated 10% of genes) compared with negatively correlated genes (top anti-correlated 10% of genes) in both normal B (B04; n = 336 and 330 genes, respectively) and CLL (CLL03 [n = 290 and 278 genes, respectively]; CLL04 [n = 320 and 314 genes, respectively]) cells. Error bars represent 95% confidence interval. P-values are shown for two-sided Welch’s t-test. Published 5-hmC data were used for the analysis20. Throughout the figure, boxplots represent median and bottom and upper quartile; lower and upper whiskers correspond to 1.5 x IQR.

Extended Data Figure 7. Methylation-based lineage trees provide a native lineage tracing system.

(a) Additional representative (random cell subsampling) methylation-based lineage trees of CLL cells. (b) Same as panel (a) for index-sorted normal B cells, showing that naïve CD27− B cells (NBC; CD27−IgM+IgD+++IgG−) precede CD27+ memory terminally-differentiated B cells (hiMBC; CD27+IgG+) in the lineage tree. (c) Representative (cell subsampling) methylation-based lineage trees of CLL cells reconstructed using only autosomes or chromosome X. Tree topologies are similar to when using whole genome information (see Fig. 3d and panel (a)), showing rapid drift after the initial malignant transformation. (d) Same as panel (c) for lineage trees of CLL cells obtained by holding-out chromosomes (hold-out three chromosomes at a time before phylogeny reconstruction; e.g., excluding chromosomes 1–3, left), or downsampling the number of CpGs per cell to equal numbers (120K CpGs per cell; right). (e) Normalized Robinson-Foulds (normRF) distances between any two trees (n = 30 tree replicates; see Methods) of CLL01 reconstructed by maximum-likelihood (ML) vs. maximum-parsimony (MP). Differences in median normRF between ML and MP are indicated on the top, with P-values for two-sided Mann-Whitney U-test. (f) Average maximum tree depth of lineage trees (n = 10 tree replicates; see Methods) of CLL (CLL01) and normal B (B02) cells when using whole genome information compared to lineage trees obtained by holding-out chromosomes (hold-out three chromosomes at a time before phylogeny reconstruction). P-values were computed for Welch’s t-test by comparing the maximum tree depths (one value per tree) between CLL and normal B samples. Error bars represent 95% confidence interval. (g) Distribution of root-to-tip branch lengths (i.e., the length from the root to each tip in the lineage tree) between CLL and normal B cells (M-CLL [CLL07], U-CLL [CLL10], B05 shown as representative examples). (h) Patristic distances between index-sorted B cells from B04, B05 and B06 healthy donor samples (NBC, n = 24 cells for each sample; loMBC, n = 24 cells for each sample; intMBC, n = 24 cells for each sample; hiMBC, n = 23 cells for each sample). P-values were computed for two-sided Mann-Whitney U-test. (i) Patristic distances between CLL (CLL01) and normal B (B02) cells obtained from lineage trees reconstructed by using only autosomes, chromosome X, holding-out chromosomes (hold-out three chromosomes at a time before phylogeny reconstruction), or downsampling the number of CpGs per cell to equal numbers (120K CpGs per cell), respectively. P-values are indicated for two-sided Mann-Whitney U-test. Throughout the figure, boxplots represent median and bottom and upper quartile; lower and upper whiskers correspond to 1.5 x IQR.

Extended Data Figure 8. MscRRBS integration with single-cell transcriptomes and genotyping.

(a) Schematic of the joint MscRRBS, transcriptome, and genotyping capture protocol. (b) Normalized Robinson-Foulds (normRF) distances between any two trees (n = 30 tree replicates; see Methods) of CLL12 (n = 56 cells; see Fig. 3h) reconstructed by maximum-likelihood (ML) vs. maximum-parsimony (MP). Differences in median normRF between ML and MP are indicated on the top, with P-values for two-sided Mann-Whitney U-test. (c) Proportion of SF3B1 wild type (white) and SF3B1 mutated cells (black) in each clade identified from the lineage tree shown in Fig. 3h. P-value is indicated for two-sided Fisher’s Exact test. (d) Comparison of number of unique CpGs (left) and CpG methylation level (right) between the SF3B1 wild-type enriched clade cells and the SF3B1 mutated enriched clade of cells identified from the lineage tree in Fig. 3h. P-values are indicated for two-sided Mann-Whitney U-test. (e) Volcano plot of differentially methylated gene promoters (absolute weighted average DNAme difference > 0.3 and two-sided non-parametric permutation test P-values < 0.05) between the SF3B1 wild type and SF3B1 mutated cells from lineage tree shown in Fig. 3h. (f) Single-cell alternative 3’ splicing score (fraction of reads that map downstream to the 3’ end [up to 100 bp] of the exons vs. within the exons) for cells belonging to SF3B1 wild type (n = 30) and SF3B1 mutated (n = 26) clades identified from the lineage tree shown in Fig. 3h. P-value is indicated for two-sided Mann-Whitney U-test. (g) Volcano plot of differentially expressed genes between the SF3B1 wild type enriched clade and SF3B1 mutated enriched clade. Genes (n = 57) with absolute log2(fold-change) > 0.5 and Benjamini-Hochberg FDR adjusted weighted F test P-values < 0.2 are shown in red. Genes that were previously reported to be affected by SF3B1 mutation22 are also labelled. (h) Gene expression projections on lineage trees for two representative genes identified in panel (g). (i) Comparison of transcriptional distances (measured as Euclidean distances of the first three principal components after PCA) as a function of lineage distance between cell pairs from the lineage tree shown in Fig. 3h. P-value is indicated for two-sided Mann-Whitney U-test. (j) Cells belonging to SF3B1-mutated enriched clade show significantly lower relative node heights (i.e., height of internal tree nodes relative to the root node; see Methods) compared with SF3B1 wild type enriched clade, consistent with SF3B1 mutation being a later subclonal event in CLL15. P-value is indicated for two-sided Mann-Whitney U-test. (k) Same as panel (j) for root-to-tip branch lengths (i.e., the length from the root to each tip in the lineage tree). (l) Distribution of node ages (estimated no. of divisions before present; see Methods) between the SF3B1 wild type enriched clade (white, n = 30 nodes) and SF3B1 mutated enriched clade (grey, n = 25 nodes). P-value is indicated for two-sided Mann-Whitney U-test. Throughout the figure, boxplots represent median and bottom and upper quartile; lower and upper whiskers correspond to 1.5 x IQR.

Extended Data Figure 9. Joint single-cell methylomics and RNAseq link epigenetic and transcriptional information in CLL evolution with therapy.