Summary

Sensory functions of the vagus nerve are critical for conscious perceptions and for monitoring visceral functions in the cardio-pulmonary and gastrointestinal systems. Here, we present a comprehensive identification, classification, and validation of the neuron types in the neural crest (jugular) and placode (nodose) derived vagal ganglia by single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) transcriptomic analysis. Our results reveal major differences between neurons derived from different embryonic origins. Jugular neurons exhibit fundamental similarities to the somatosensory spinal neurons, including major types, such as C-low threshold mechanoreceptors (C-LTMRs), A-LTMRs, Aδ-nociceptors, and cold-, and mechano-heat C-nociceptors. In contrast, the nodose ganglion contains 18 distinct types dedicated to surveying the physiological state of the internal body. Our results reveal a vast diversity of vagal neuron types, including many previously unanticipated types, as well as proposed types that are consistent with chemoreceptors, nutrient detectors, baroreceptors, and stretch and volume mechanoreceptors of the respiratory, gastrointestinal, and cardiovascular systems.

Keywords: single cell RNA-sequencing, vagus nerve, sensory neurons, viscerosensory, somatosensory, transcriptome, jugular ganglion, nodose ganglion, mechanoreceptor, nociceptor

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

A comprehensive molecular identification of neuronal types in vagal ganglion complex

-

•

Prdm12+ jugular ganglion neurons share features with spinal somatosensory neurons

-

•

Phox2b+ viscerosensory nodose neurons are molecularly versatile and highly specialized

-

•

Nodose neuron types are consistent with chemo-, baro-, stretch-, tension-, and volume-sensors

Visceral sensory neurons are necessary for the control of organ functions, but knowledge on the complexity of neuron types involved is missing. Kupari et al. molecularly identify jugular and nodose ganglion neurons and find a large diversity of neuron types that are consistent with the numerous sensory functions of the vagus nerve.

Introduction

Sensory signaling through the vagus nerve has a critical role in the maintenance of bodily homeostasis in diverse functions relating to digestion, satiety, respiration, blood pressure, and heart rate control (Mazzone and Undem, 2016, Waise et al., 2018, Wehrwein and Joyner, 2013). Its profound role is illustrated by abnormalities that can lead to far-reaching consequences, including gastroesophageal reflux disease, heart failure, failure of respiratory control, gastroparesis, vasovagal syncope, and chronic pain. The vagal sensory neurons form the jugular and nodose ganglia residing in the same nerve sheath. This highly diverse ganglion complex contains both general somatic and visceral sensory neurons innervating targets ranging from the skin at parts of the head and throat to most of the visceral organs. Although activation of jugular neurons leads to somatic sensation, nodose neurons are, instead, mostly connected to reflex circuits controlling organ function and body homeostasis through activation of the autonomic nervous system.

With such diverse functions, vagal neurons are equipped to sense and respond to a variety of stimuli, including stretch, pressure, noxious, temperature, chemical, and inflammatory mediators. In the airways, they regulate the depth and rate of breathing, secretions, and bronchomotor tone through a number of neurons with different characteristics, including rapidly and slowly adapting mechanoreceptors, Aδ-mechanoreceptors, and C-fibers (Lee and Yu, 2014). In the gastrointestinal system, they provide both mechanosensory monitoring of gut distension and chemosensory monitoring, detecting the intra-intestinal chemical environment and controlling gastric motility and feeding behavior (Brookes et al., 2013, Pavlov and Tracey, 2012, Pavlov and Tracey, 2017).

In the somatosensory dorsal root ganglia (DRGs), various molecularly different neuronal types exist with predictable and unique response profiles. Neuron types classified by these features directly reflect both ontogeny and function, with a taxonomy containing four principal clades: cold, mechano-heat, A-low threshold mechanoreceptors (A-LTMRs), and mechano-heat-itch and C-low threshold mechanoreceptors (C-LTMRs), in which each clade branches into several neuron types with unique response properties (Emery and Ernfors, 2018). This heterogeneity among neuron types is what provides the cellular basis for discrimination among somatic sensory modalities and forms the basis for the ability to perceive, explore, and interpret the surrounding world. Recent results suggest that the vagal sensory ganglia, similar to DRGs, rely on the existence of specialized neuron types. For example, two lung-innervating vagal sensory neuron populations, with powerful and opposite effects on breathing dynamics, have been discovered (Chang et al., 2015). Furthermore, specialized neurons detecting nutrients and stretching in the gut exist (Williams et al., 2016). In addition to conventional functions attributed to vagal afferents, neuropsychological functions, such as reward processing, were recently shown to be initiated by gut-innervating, nodose ganglion neurons (Han et al., 2018). Despite its importance, our understanding of the vagal sensory system remains fragmented and poorly defined, not least because of the scarcity of molecular-level knowledge about the different neuronal subtypes and the lack of tools to target the specific populations (Udit and Gautron, 2013). Sensory innervation of respiratory, gastrointestinal, and cardiovascular systems has been studied for more than 60 years, and a variety of features have been recorded; however, it has been difficult to reconcile findings and, therefore, little consensus has emerged about the sensory neuron types involved. A comprehensive and systematic effort to unravel the molecular basis of the visceral sensory system would enable deep mechanistic insights. Considering the vast importance of the vagal sensory system and the lack of a molecular understanding of its constituent cell types, we have transcriptionally profiled the principal cell types of the vagal sensory system using single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq). Categorizing the neural pathways arising from visceral afferents enables insights into how organ homeostasis is maintained and could explain aberrations in this system that cause disease.

Results

Vagus Nerve Ganglia Are Assembled from Numerous Specialized Neuron Types

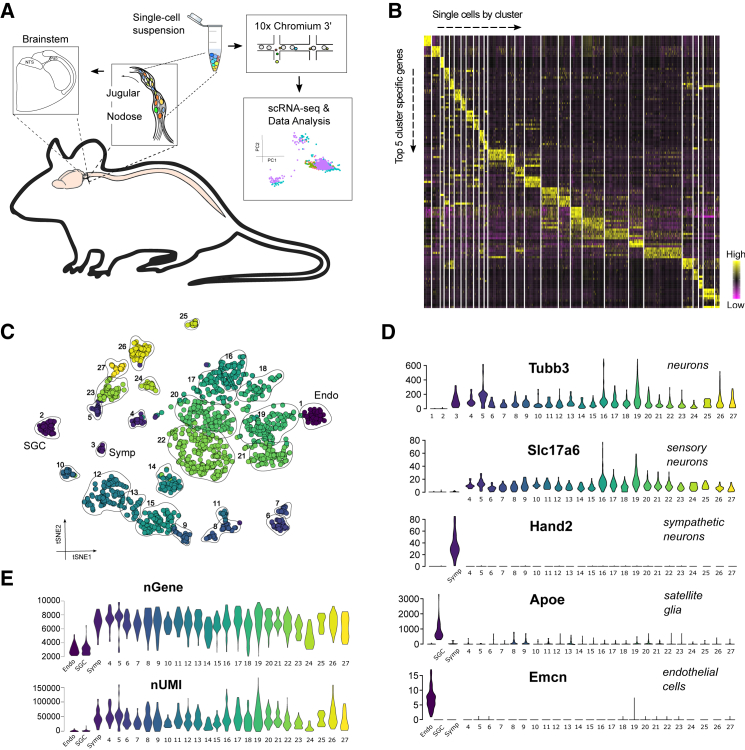

We performed four biological replicates of scRNA-seq on acutely dissociated, vagal ganglionic cell suspensions using the 10x Genomics Chromium (Zheng et al., 2017) platform (Figure 1A). The first two replicates originated from wild-type, and the remaining two from Vglut2CreTomato, mice. The Vglut2CreTomato mice were used to further increase the yield of neuronal over non-neuronal cells by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (Figure S1A). In all, we sequenced 1,896 cells (for sequencing metrics, see Table S1). Low-quality cells and possible doublet cells were removed in quality control (QC) steps; after which, 1,825 cells passed the requirements (Figure S1B; Method Details). After feature selection, removal of confounding sources of variation, and principal-component analysis (PCA), the cells were clustered by the Seurat Louvain-based algorithm. The first round of analysis produced 34 clusters, and after merging of highly similar groups (Method Details; Figures S1C and S1D; Table S2), 27 clearly distinctive cell types remained (Figure 1B). When visualized with the t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (tSNE) method, the cells were seen to be organized into individual clouds, agreeing with their unique qualities (Figure 1C). We investigated the cellular heterogeneity by examining markers that defined groups of similar clusters (Figure 1D); 25 of the 27 clusters expressed neuronal markers (e.g., Tubb3, Snap25, and Uchl1), indicating that most cell types were neurons. All but one of the neuronal clusters expressed Vglut2 (Slc17a6), a marker for peripheral sensory neurons. The Vglut2− neuron population displayed a clear profile of sympathetic neurons (expressing Hand2, Tbx20, and Ecel1) and likely originated from the superior cervical ganglion. The two non-neuronal clusters were identified as blood vessel-derived endothelial cells (expressing Emcn, Ecscr, and Cdh5) and as satellite glial cells (SGC) that cover the somata of all peripheral neurons (expressing Apoe, Fabp7, and Dbi). The 10 most abundantly expressed SGC markers, which together represented nearly 12% of the RNA molecules in the satellite cells, contributed less than 0.2% of the RNA in neurons, indicating that the influence of glial RNA is negligible in the single-cell neuron preparations (Figure S1E; Table S3; Method Details). All neuron clusters included cells from each biological replicate, demonstrating that the transcriptional profiles were robust and reproducible over the experiments and mouse strains (Figure S1F; Table S4). As expected, the non-sensory cells were only derived from wild-type mice (Figure S1F). A clear distinction was made between the neuronal and non-neuronal cells at the levels of detected genes and unique transcripts (unique molecular identifiers [UMIs]), reflecting the clear difference in soma size between these cell types (Figure 1E). For neurons, we detected an average of 6,705 genes per cell. Taken together, the diversity of the 1,704 sequenced sensory neurons defined 24 major neuronal clusters, suggesting a highly heterogeneous cellular composition in the vagal ganglionic complex. Browsing summary information on individual gene level is available at https://ernforsgroup.shinyapps.io/vagalsensoryneurons/.

Figure 1.

Cellular Heterogeneity in the Vagal Ganglion Complex

(A) Schematic illustration of the vagal sensory system and the workflow.

(B) Heatmap showing the five most-selective genes (by lowest padj) in each cluster. Clusters were hierarchically ordered in PCA space.

(C) tSNE visualization. Clusters were numbered according to (B). Clusters 4–27 are sensory neurons.

(D) Violin plots showing major cell type-specific marker expression across the clusters. Values on the y axis represent raw UMI counts.

(E) Violin plots showing the numbers of total genes and UMIs detected in each cluster.

Endo, endothelial cells; SGC, satellite glial cells; Symp, sympathetic neurons.

Jugular and Nodose Neurons Are Fundamentally Different

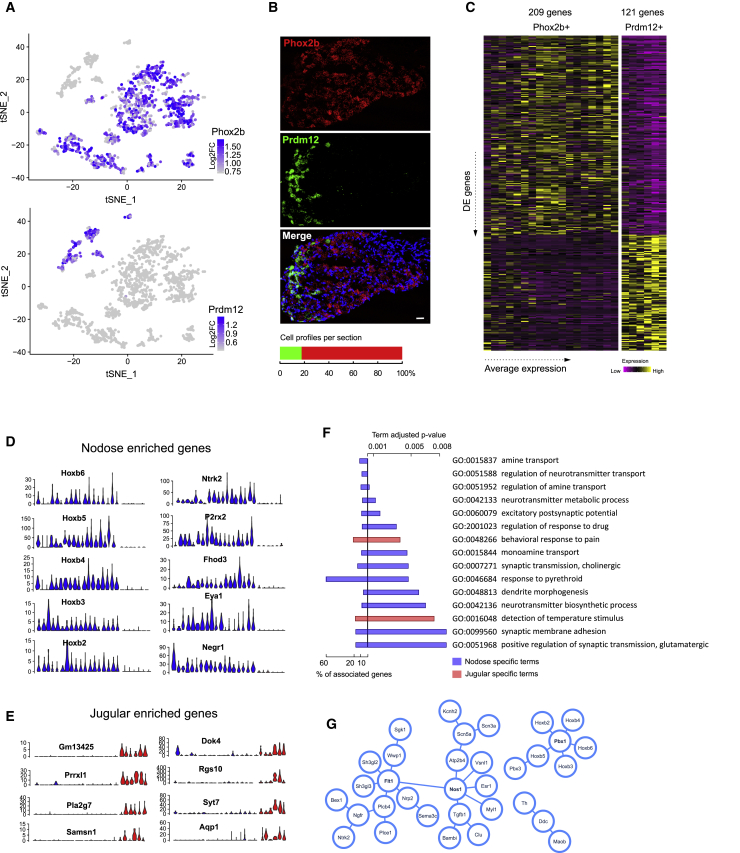

A single mouse vagal ganglion complex comprises a cellular mass in which the neural crest-derived jugular ganglion and the placode-derived nodose ganglia have merged during embryonic development (Nassenstein et al., 2010). We reasoned that Phox2b, a transcription factor expressed in placodal cranial sensory ganglia, could serve as a marker distinguishing neurons originating from the different embryonic tissues (Dauger et al., 2003, D’Autréaux et al., 2011). Indeed, we discovered that 18 of 24 neuron populations (1,459 of 1,707 neurons) expressed Phox2b, whereas the remaining clusters expressed another transcription factor, the histone-modifying Prdm12. We used RNAScope technology to further quantify the relative proportions of Phox2b- and Prdm12-expressing neurons in vivo. Of 469 counted neurons, 386 were Phox2b+, and 83 were Prdm12+ in a mutually exclusive pattern. Together with the sequencing data, this indicated that the vagal ganglion complex is built out of approximately 85% nodose and 15% jugular neurons (Figures 2A and 2B). We discovered 330 differentially expressed genes (Wilcoxon rank-sum test, log2-fold change (log2-FC) > |0.25|, adjusted p value [padj] < 1.5 × 10−5); of which, 209 were enriched in the Phox2b+, and 121 in the Prdm12+, clusters (Figure 2C; Table S5). The most selective nodose genes included the transcription factors Hoxb2 to Hoxb6 observed in at least 16 of 18 clusters (Figure 2D). In addition, the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF)-receptor TrkB (Ntrk2), the purinergic receptor P2rx2, and the phosphatase and transcriptional coactivator Eya1 were among the most-defining genes for nodose neurons. The two most-distinctive jugular genes were the paired homeodomain protein gene Prrxl1 and the predicted gene Gm13425, the latter residing inside the Prdm12 5′-UTR producing an antisense, long non-coding RNA transcript (Figure 2E). Selective Gene Ontology (GO) terms (Bonferroni-Holm adjusted p value < 0.005) included pain and temperature for the jugular neurons (Figure 2F; Table S6), underlining their somatosensory nature. However, terms associated with nodose neurons showed far more diversity with terms related to amine and monoamine transport, neurotransmitter transport and synthesis, and cholinergic and glutamatergic synaptic transmission. A STRING analysis (https://string-db.org/) for the nodose genes revealed that the Hoxb expression was accompanied by the pre-B-cell leukemia transcription factors Pbx1 and Pbx3 in most neurons (Figures 2G and S2). We also discovered a hub of interactions based around the gene Nos1, suggesting that nitric oxide functions as a neurotransmitter in many nodose neurons. Two more restricted protein-interaction clusters were found around the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (Flt1) and a set of genes that define a dopaminergic neuronal phenotype (Th, Ddc, and Maob).

Figure 2.

Major Molecular Differences between Jugular and Nodose Ganglion Neurons

(A) tSNE illustrating the two different neuron populations: Prdm12+ jugular neural crest- and Phox2b+ nodose placode-derived neurons.

(B) ISH images showing the mutually exclusive expression of Prdm12 and Phox2b. Scale bar is 20 μm. Stacked bar illustrates the proportions of jugular and nodose cell profiles per section (469 cells, n = 3 animals)

(C) Heatmap showing the 330 differentially expressed genes between the nodose and jugular clusters.

(D) Violin plots showing the expression of genes with highly selective enrichment in all or most nodose neurons.

(E) Violin plots showing the expression of genes with highly selective enrichment in all or most jugular neurons. Blue and red colors in (D and E) indicate nodose and jugular clusters, respectively; y axes in (D and E) indicate the number of raw UMIs detected.

(F) GO terms enriched in neurons derived from the different ganglia.

(G) STRING interaction map for nodose neurons.

Reiteration of DRG Neuron Types in the Jugular Ganglion

The jugular-neuron types were hierarchically clustered and named JG1–JG6 (Figure 3A). The first split divided the neurons into two groups of three clusters based on genes shared on the same, but lacking on the opposing, dendrogram branch (Figure 3A; Table S7). JG1–JG3 showed high expression for prostatic acid phosphatase (Acpp) and for the Na/K-ATPase modulator Fxyd2, whereas JG4–JG6 expressed another member of the Fxyd family (Fxyd7) and the citron rho-interacting kinase (Cit), among others. Further in the tree, JG2 and JG3 were most clearly separated from JG1 by their shared expression of Tmem233 and JG5 and JG6 from JG4 by their expression of Rasgfr1. The two most-abundant clusters were JG2 and JG4, each covering more than 25% of jugular neurons, whereas the others made up to 10%–12% per cluster (Figure 3B; Table S4). In a tSNE, the individual clusters clearly separated, yet JG1 could be seen more distant from the others (Figure 3C). All clusters were clearly defined by a specific gene-expression profile (Figure 3D; Tables S8 and S15). JG1 selectively expressed the T-type calcium channel Cav3.3 (Cacna1i), JG2 expressed the Mas-related G-protein coupled receptor member D (Mrgprd), and JG3 neurons expressed the oncostatin-M receptor (Osmr), whereas pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating peptide (PACAP; Adcyap1) was expressed at high levels in JG4, Vglut1 (Slc17a7) in JG5, and the menthol receptor Trpm8 in JG6. To validate the clusters in vivo, we used in situ hybridization (RNAScope), always combining two probes targeting separate clusters, along with a Prdm12 probe (Figures 3E, 3F, and S3). JG1 neurons were identified as Wfdc2+ and JG2 neurons as Mrgprd+. JG3 cells were Osmr+, JG4 neurons expressed Kit but were low for Nefh, JG5 neurons expressed high levels of Nefh, and JG6 were Foxp2+.

Figure 3.

Jugular Ganglion Comprises Neurons with General Somatosensory Neuron Features

(A) Dot plot showing selected genes that define splits in the major branches of the jugular ganglion dendrogram.

(B) Pie chart showing the proportional abundance of the jugular neuron types.

(C) tSNE visualization of the jugular clusters.

(D) Heatmap showing the top five most-specific genes for individual jugular clusters (by lowest padj).

(E) Single-cell bar plots showing the expression of genes used in the in vivo validation of the jugular-clustering data. Numbers on the right indicate the maximum number of UMIs detected.

(F) Images from the ISH validation identifying the existence of each jugular cluster in vivo. Scale bar indicates 10 μm.

To elucidate the transcriptomic relationships between jugular and spinal somatosensory neurons, we performed a cluster-by-cluster comparison between the jugular and established DRG cell types (Emery and Ernfors, 2018, Usoskin et al., 2015). For this, we used MetaNeighbor, a classifier-tool that measures similarity among cell types and can be used in identifying cells of similar type across different datasets (Crow et al., 2018). Using the latest DRG scRNA-seq dataset (Zeisel et al., 2018), we conflated the DRG cell types to 10 major classes: Th+ C-LTMR, Mrgprd+ C-non-peptidergic nociceptor (NP1), Mrgpra3+ C-nociceptor (NP2), Sst+ C-nociceptor (NP3), peptidergic C-nociceptor (PEP1), Aδ-nociceptor (PEP2), Aδ-LTMR (NF1), Aβ-LTMR (NF2/3), Aβ-Proprioceptor (NF4), and cold Trpm8+ neuron (TRPM8). With a set of highly variable genes derived from both datasets (Table S9), the unsupervised MetaNeighbor was able to classify jugular and DRG neurons with high performance (Figure 4A). JG1 was similar to C-LTMR (TH) population, JG2 to NP1, JG3 to NP3, JG4 to PEP1, and JG6 to the TRPM8 type. JG5 showed high similarity to all myelinated DRG neuron types (area under the receiver operating characteristic [AUROC] > 0.94). Similar results were obtained when comparing jugular neurons to another DRG neuron dataset (Li et al., 2016; see Figures S4A–S4E). The one-to-one relationships prompted us to examine the expression of the most cluster-specific jugular genes within the DRG neuron types. Top jugular genes showed a strong enrichment in the corresponding DRG clusters (Figure 4B) and, conversely, the expression of 30 top DRG markers within the jugular clusters (Figure 4C; Table S10), corroborating the MetaNeighbor analysis. Two jugular types (JG3 and JG5) required a deeper analysis because some jugular markers were expressed in more than one DRG neuron type. Most JG3 markers were consistent with NP3 DRG neurons; however, some defining features for NP2, such as Mrgpra3, were among the JG3 markers. Interestingly, NP3 and NP2 markers showed expression in mutually exclusive subsets of JG3 neurons (Sst and Il31ra for NP3; Mrgpra3 and Gfra1 for NP2, respectively), showing that this cluster is a mixture of two types of neurons (Figure 4D). Similarly, JG5 genes were expressed across the NF populations and the PEP2 population, but a closer evaluation revealed a mutually exclusive expression of NF2/3 (Aβ-LTMR–selective markers Gfra1, Slc17a7, and Ptgfr) and PEP2 (aδ-nociceptor selective markers [Ntrk1, Calca]), suggesting the existence of both these myelinated neuron types among the JG5 cluster (Figure 4E). The expression of Cntn1 and Cntnap1 and low Ncam1 levels in JG5 and JG6 neurons support that these are myelinated and possibly lightly myelinated neuron types, respectively (Figure S5).

Figure 4.

Jugular-DRG Comparison Reveals Shared Identities between Neuronal Types

(A) Heatmap showing the results from the unsupervised MetaNeighbor analysis between jugular and DRG clusters. Vertical names refer to DRG neuron types, and horizontal names refer to jugular neuron types. Numbers inside the cells indicate the mean AUROC score for the comparison.

(B) Heatmap showing the expression of top jugular markers in the DRG neuron types (10 genes by lowest padj); note that the DRG clusters represent the main branches of neuron types (see Emery and Ernfors, 2018).

(C) Heatmaps showing the expression of top DRG markers in the jugular clusters (30 genes by lowest padj value).

(D) Heatmap showing the segregation of NP2- and NP3-specific DRG cluster markers into separate subsets of JG3 neurons.

(E) Heatmap showing the segregation of Aβ-LTMR (NF2/3)- and Aδ-nociceptor (PEP2)-specific markers into separate subsets of JG5 neurons.

All Nodose Clusters Exist as In Vivo Cell Types

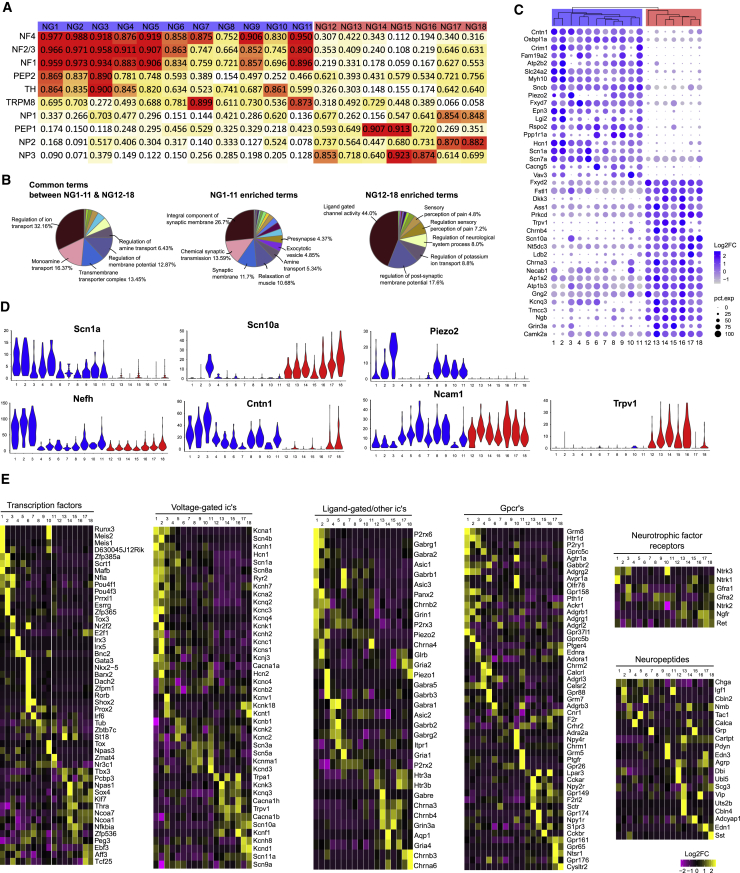

All nodose neuron-types showed unique gene-expression profiles and were named NG1–NG18, according to the hierarchical tree (Figure 5A; Tables S11 and S16). A major branch was positioned between NG11 and NG12, dividing the clusters into two subdivisions. In a tSNE, NG12–NG18 formed a larger cloud that was lined by a string of clusters derived from NG1–NG11, echoing the division seen in the dendrogram (Figure 5B). Regarding population size, NG1–NG11 clusters were mostly small, many of them consisting of only 2%–3% of the total number of cells, whereas NG12–NG18 clusters were more populous, with NG15 reaching to >17% of the total nodose neuron tally (Figure 5C; Table S4).

Figure 5.

Broad Diversity of Nodose Ganglion Neuron Types

(A) Heatmap showing the five most-specific genes for each of the 18 nodose neuron types (five genes by lowest padj).

(B) tSNE plot of the nodose clusters.

(C) Proportional abundance of the nodose neuron types.

(D) Single-cell bar plots showing the expression of genes used in the in vivo validation of the nodose clustering data. Numbers on the right indicate the maximum number of UMIs detected.

(E) Images from the ISH validation for in vivo existence of predicted nodose neuron types. Scale bars indicate 10 μm.

In (A) and (D), NG1–NG11 and NG12–NG18 are indicated by blue and red color, respectively.

We validated the clusters by in situ hybridization (ISH) using Phox2b as the base marker for 16 of 18 clusters and using additional highly cluster-specific markers or a combination defining only one cluster. For some clusters, we also used negative markers to rule out types other than the one under analysis (Figures 5D–5E; Data S1). Validation confirmed the in vivo existence of all predicted neuron types.

Molecular Diversity of the Nodose Viscerosensors

The hierarchical clustering and the structure of the tSNE alluded of a major division in the cell types, possibly separating the neurons into groups that convey different modalities of sensory information. We again used MetaNeighbor, this time comparing the nodose clusters against DRG neurons (see Table S12 for the genes used). We postulated that looking for similarities and dissimilarities against DRG neurons could give us insight to the functional roles of the nodose neurons. The results divided nodose clusters into two groups: one sharing more similarity with mechanosensory and the other with nociceptor neuron types. Agreeing with the hierarchical grouping of the nodose clusters, this split occurred between NG1–NG11 and NG12–NG18 (Figure 6A). Interestingly, we found many of the NG1–NG11 clusters were most similar to the proprioceptor DRG neurons (NF4), with clusters NG1 and NG2 receiving the highest scores. A comparison against a second DRG dataset (Li et al., 2016) was consistent with that analysis (Figure S4F). We then wanted to see whether these observations were supported by the gene expression profiles governing the split between the NG1–NG11 and NG12–NG18 clusters. The GO terms enriched in the two groups reiterated the division into more mechanosensor- versus nocisensor-like types (Figure 6B; Table S13). Here, 390 genes showed significant differential expression (Wilcoxon rank-sum test, Log2FC > |0.25|, padj < 1 × 10−6), with 178 enriched in NG1–NG11 and 212 in NG12–NG18 (Figure 6C; Table S14). Strikingly, a clear split was observed in the expression of two voltage-gated sodium channels, where Nav1.8 (Scn10a) was highly expressed by all NG12–NG18 neurons, whereas Nav1.1 (Scn1a) was expressed exclusively in NG1–NG11 (Figure 6D). Also, 7 of the 11 NG1–NG11 clusters expressed the mechanically sensitive channel Piezo2, suggesting a mechanosensory role for these types. In addition, 3 of the 11 clusters (NG1, NG2, and NG3) showed high expression of Nefh and Cntn1, but low Ncam1, implying a myelinated Aβ-fiber structure, whereas two others (NG9 and NG11) showed an intermediate, combined expression level of those genes, possibly corresponding with a thinly myelinated phenotype (Figure 6D). Along with Nav1.8, most NG12–NG18 neuron types also expressed the capsaicin receptor Trpv1—a clear indication of more nociceptor-like properties. We extended our characterization of the nodose cell types by examining the occurrence or absence of known markers previously used to identify nodose neuron types and also screened the clusters for transcription factors (TFs), ion channels, receptors, and neuropeptides, reasoning that the combined fingerprint could form a basis for defining the identity of the neuronal types (Figure 6E). By these analyses, we conclude that we have identified a diversity of neuron types that is consistent with A-LTMRs mechanoreceptors involved in volume detection, stretch sensors, baroreceptors, small fiber gastric tension and gastrointestinal hormone sensors, pulmonary nociceptors, and gastric nutrient detectors. The most salient features of the cell types are shown in Figure 7 and are described in the Discussion below (see also Figure S6).

Figure 6.

Unique Features Define Nodose Sensory Neuron Types

(A) Heatmap showing the results from the unsupervised MetaNeighbor analysis between nodose and DRG clusters. Numbers inside the cells indicate the mean AUROC score for the comparison. Vertical names refer to DRG neuron types, and horizontal names refer to nodose neuron types.

(B) Pie charts showing the distribution of GO terms equally shared between, or enriched, in the two major branches of nodose neurons (NG1–NG11 and NG12–NG18). Enrichment was defined as >60% of the term genes significantly upregulated in the group in question.

(C) Dot plot showing the 20 most-specific genes for NG1–NG11 and NG12–NG18 (by lowest padj).

(D) Violin plots showing selected genes differentially expressed between the two major groups (NG1–NG11 versus NG12–NG18); y axis indicates detected, raw, UMI counts.

(E) Heatmaps showing the expression profiles of different categories of genes within the different nodose neuron types.

In (A), (C), and (D), NG1–NG11 and NG12–NG18 are indicated by blue and red color, respectively.

Figure 7.

Proposed Vagus Nerve Sensory Neuron Classification and Their Relation to Function

(A) Jugular ganglion neuron types and their functional relations based on shared neuronal identity with functionally characterized DRG neurons.

(B) NG1–NG11 nodose ganglion neuron types showing similarity to LTMRs. Predicted fiber type, selected relevant genes, and proposed functions are indicated.

(C) NG12–NG18 nodose ganglion neurons showing similarity to polymodal nociceptors. Predicted fiber type, selected relevant genes, and proposed functions are indicated. IGLEs, intraganglionic laminar endings.

Discussion

Although the peripheral anatomy as well as neurochemistry and physiological properties of vagal afferents have been studied, the lack of information on the constituent neuronal types that makes up the vagal ganglion complex and knowledge of appropriate gene markers that can be used to determine their function have limited our understanding of the principles that govern the visceral sensory system. In this study, we have identified the neuronal types that build the vagus nerve jugular and nodose ganglion complex. Our results allow for a number of functional predictions to be made, but importantly, also provide tools for direct experimental strategies to address their morphology, physiology, connectivity, and function.

We discovered fundamental differences between the somatosensory jugular and the visceral nodose ganglia. This was possible because we determined the transcriptome in individual neurons and could retrospectively assign neurons to the jugular or nodose ganglion. Previously, their co-existence in one complex precluded the discovery of many principal differences between these neuronal types (Peeters et al., 2006, Tränkner et al., 2014, Wang et al., 2017). One of these differences is the expression of the homeobox protein Phox2b in nodose ganglion neurons. In the absence of this transcription factor, visceral neuron features are lost and replaced by some somatic sensory features during development (D’Autréaux et al., 2011). In contrast, Prdm12 is expressed in all jugular sensory neurons but not nodose ganglion neurons, consistent with the Wang et al. (2017) finding of Prdm12 in jugular neurons, as well as the finding that Prdm12 is expressed in all mouse DRG nociceptive neurons (Usoskin et al., 2015, Zeisel et al., 2018) and is essential for human pain perception (Chen et al., 2015). We also identified an additional 330 genes that are differentially expressed between neurons of the two ganglion types. Our results show that, although jugular neurons largely correspond to somatosensory neurons of the DRGs, nodose neurons do not. This difference may partly relate to the principal distinction among molecular features necessary for the somatosensory versus the visceral sensory system but could also be a consequence of the distinct embryonic origin between neurons of these ganglia (D’Autréaux et al., 2011, Le Douarin, 1984). Thus, the fundamental differences between neurons of these ganglia might reflect different developmental strategies in generating sensory neurons from neural crest versus epibranchial placodes (Moody and LaMantia, 2015). Nevertheless, it is interesting to note that many terminal effector genes, such as ion channels, receptors, and neuropeptides, are shared between placode- and neural crest-derived neurons.

All jugular neuron types identified correspond to neuronal types existing in the DRG (Li et al., 2016, Usoskin et al., 2015, Zeisel et al., 2018). Therefore, the generation of somatosensory neurons during development results in similar neuron types, regardless of the position of the ganglia. Because much is known about the qualities of the different DRG neuron types, we can, with precision, tentatively assign functions to jugular neuron types (Figure 7A). JG1 cluster shows high similarity to the “TH/Vglut3” somatosensory cluster that represents C-LTMRs. In mouse DRGs, this population terminates in hair follicles as lanceolate endings (Li et al., 2011, Seal et al., 2009) and, in humans, is involved in pleasant tactile sensations (Björnsdotter et al., 2010, Löken et al., 2009, Olausson et al., 2010). JG2 closely resembles the Mrgprd+ “NP1” cluster, mechano-nociceptive neurons required for sensing punctate mechanical stimuli (Cavanaugh et al., 2009). Some JG3 neurons represent NP2 and others NP3 DRG types. The JG3 cluster likely did not split into two clusters because of the scarcity of these neurons in the jugular ganglion. NP2 DRG neurons are dedicated itch-transducing neurons (Han et al., 2013), whereas NP3 neurons are general chemosensitive, including also itch compounds. JG4 represents PEP1 in DRG—a polymodal, high-threshold, mechano-heat sensitive C-fiber contributing to inflammatory pain, sensation of noxious heat (Vandewauw et al., 2018), and low pH (Tominaga et al., 1998), consistent with heat and low pH activation of C-fibers in the airways (Gu and Lee, 2006, Hayes et al., 2012, Khosravi et al., 2014, Kollarik and Undem, 2002). JG5 is similar to essentially all myelinated DRG sensory neurons and is the only clearly myelinated jugular cluster. This cluster contains both Aβ-LTMR and Aδ-nociceptive neurons involved in touch sensation and sharp pain, respectively. Finally, JG6 neurons display high similarity to Trpm8+ and Foxp2+ DRG neurons involved in detecting noxious and innoxious cold sensations, consistent with previous results showing that cold sensitivity is mediated by Trpm8+ vagal neurons that may be involved in respiratory responses to cold (airway constriction and mucosal secretion) and these are exclusively jugular (Xing et al., 2008, Zhou et al., 2011). The expression of moderate Cntn1 and Cntnap1 levels and low Ncam1 levels in most of the JG6 neurons indicate little heterogeneity in the Trpm8+ population of neurons in terms of myelination and suggest that they might be lightly myelinated fibers. The finding of DRG types in the jugular ganglion is consistent with it supplying cutaneous innervation of the external ear. However, our results highlight that somatosensory visceral innervation by the jugular ganglion is conferred by the same complements of neurons as those involved in cutaneous sensation, consistent with many nociceptive neuron types in the DRG that seem to exist in two highly related versions, one innervating cutaneous and the other deep tissues (Emery and Ernfors 2018).

Principal differences between NG1–NG11 and NG12–NG18 involved, among others, several ion channel and related proteins (Fxyd7, Snc1a, Atp2b2, Hcn1, and Piezo2 in NG1–NG11 and Fxyd2, Fstl1, Scn10a, and TrpV1 in NG12–NG18). MetaNeighbor analysis suggested high similarity among several nodose and DRG cluster pairs; however, there was no clear one-to-one relationship between any two neuron types. Nevertheless, this analysis revealed that NG1–NG11 neurons displayed great similarity to LTMR DRG neurons, whereas NG12–NG18 neurons were most similar to nociceptive DRG neurons. By examining the molecular profiles in relation to functional studies, we can draw a number of conclusions regarding several nodose neuron types.

NG1–NG11 nodose neurons share Nav 1.1 (Scn1a), not present in NG12–NG18. In somatosensory neurons, Nav 1.1 is expressed exclusively in A-fiber LTMRs. The expression of high Nefh and Cntn1 and low Ncam1 levels confirm NG1–NG3 represent Aβ-fiber neuron types; the remaining likely representing unmyelinated or perhaps lightly myelinated δ-like fibers. Nodose ganglion is the main source of fast-conducting Aβ-LTMRs innervating the lower airways (Carr and Undem, 2003, McGovern et al., 2015, Nassenstein et al., 2010). These fibers express Slc17a7 (Vglut1) and ATP receptor P2ry1 but are negative for Trpv1 (Brouns et al., 2006, Chang et al., 2015). Mechanotransduction in these fibers relies on Piezo2 (Nonomura et al., 2017), and activating P2ry1+ neurons induces apnea. P2ry1+ neurons also innervate the heart and stomach, likely performing similar sensory functions (Chang et al., 2015). Only NG1 neurons express the combination of Slc17a7, Piezo2, and high P2ry1. Consistently, these neuron types are negative for Trpv1. Pulmonary Aβ-LTMRs are sub-categorized based on action potential adaptation as slowly adapting receptors (SARs) responding to both the dynamic and sustained component of inspiration and rapidly adapting receptors (RARs) responding primarily to the dynamic component (Knowlton and Larrabee, 1946, Mazzone and Undem, 2016). Molecular differences divide SAR and RAR properties of DRG neurons into two distinct types, and similarly, NG1 and NG2 might represent SAR and RAR nodose neurons. Another interesting link here is the finding that vagal afferent mechanoreceptors to smooth muscle, intramuscular arrays (IMAs), are morphologically similar to muscle spindle afferents and have been proposed to operate as functional analogs of the muscle spindle organs (Powley and Phillips, 2011). Although it is unclear whether IMAs are of an A-fiber type and, therefore, consistent with NG1 neurons, the NG1 neuron type still shares many molecular features with somatosensory limb proprioceptive A-fiber neurons, such as Pvalb, Runx3, Ntrk3, and Cacng2, and the expression of both Runx3 and Ntrk3 are both essential for the generation of muscle spindles and Golgi-tendon organ DRG neurons (Ernfors et al., 1994, Levanon et al., 2002), implicating them as pulmonary volume receptors.

Stretch-sensitive baroreceptor afferent neurons terminate in the walls of the aorta and carotid sinus and regulate blood pressure (Kirchheim, 1976, Wehrwein and Joyner, 2013). Activation of baroreceptors results in a decrease in heart rate, cardiac output, and vascular resistance, counteracting the initial increase in blood pressure. A conditional knockout of Piezo1 and Piezo2 in nodose-petrosal neurons abolishes the baroreflex and disrupts blood pressure and heart rate regulation in mice (Zeng et al., 2018). A-fiber baroreceptors are consistent with NG1–NG3 neurons, and, although it is not fully clear whether Piezo1 and Piezo2 work in different or the same neurons, it is noteworthy that NG3 represents a neuron type that expresses both Piezo1 and Piezo2, and that neuron type could, therefore, be an interesting candidate as a stretch-activated A-fiber baroreceptor neuron, in particular, because the only other Piezo1-expressing nodose neuron types are Gpr65+ neurons, and Gpr65-Cre traced vagal neurons appear to innervate mostly the gut (Williams et al., 2016). However, although a prediction can be made on the identity of the A-fiber baroreceptor, too little is known of C-fiber baroreceptors for them to be predicted.

NG4, NG5, and NG6 are likely chemosensitive with defining markers among other Calca (NG4), Avpr1a and Tac1, (NG5), and Agtr1a (NG6) but also express the peptide receptor Gpr139 (NG4, NG5) (Nøhr et al., 2017); the PGE2 receptor Ptger3 (NG4, NG5), which mediates neuronal excitation by PGE2 in ferret gastro-esophageal vagal afferents in vitro as well as of lung and airway (Lee and Pisarri, 2001, Page and Blackshaw, 1998); and the serotonin receptor Htr3a (NG6). It should be noted that channels other than Piezo1 and Piezo2 mediate mechanotransduction in somatosensory C-fibers; therefore, an absence of these channels in small-fiber nodose neurons cannot exclude mechanosensitivity, and hence, it cannot be excluded that these neurons are also mechanosensitive.

NG7–NG10 could be polymodal, unmyelinated fibers responding to both mechanical and chemical stimuli because these types express Piezo2 along with Htr3a as well as the long chain fatty acid receptor Ffar4 (NG8), melanocortin 4-receptor (Mc4r, NG9), and short chain fatty acid receptor Olfr78 (NG10) at lower levels. Thus, these neuron types represent putative mechano- and chemo-sensitive neurons with unknown functions. The high resemblance between NG10 and NG1 in terms of gene expression indicates that this neuron type could be functionally similar to NG1, although unmyelinated, consistent with that the closest DRG neuron type in MetaNeighbor analysis, which is C-LTMRs. NG11 is the only vagal neuron type expressing glutamate metabotropic receptor 5 (mGluR5, Grm5). Gastroesophageal low-intensity stretch mechanoreceptors trigger transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxation (TSLEs), which can cause gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD). Transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxations can be inhibited by an mGluR5 antagonist (Frisby et al., 2005, Jensen et al., 2005). Thus, small-fiber gastric tension mechanoreceptors are consistent with NG11.

Based on low levels of Cntnap1 and Cntn1 and high Ncam1, NG12–NG18 neurons are likely various types of unmyelinated or lightly myelinated chemoreceptors, including nutrient receptors and inflammatory mediator receptors. Consistently, all express the voltage-gated sodium channel Nav1.8 (Scn10a), but not Nav1.1 (Scn1a). Chemoreceptors are present throughout the lung, airways, and gastrointestinal tract. Intrapulmonary, nodose C-fibers express TrpV1 and GFRa1 (Lieu et al., 2011), largely corresponding to NG12–NG16 neurons. However, vagal afferents innervating the upper gastrointestinal tract also express Trpv1, although it is unclear whether these are jugular or nodose neurons (Zhang et al., 2004). Nevertheless, each cell type in the group containing NG12–NG18 neurons expresses unique features. Although NG12 expresses Trpv1, Trpa1, Lpar3, and Htr3a/Htr3b, NG13 and NG15 express Cckar as well as Npy2r. Vagal afferents sense cholecystokinin (CCK) released by enteroendocrine cells in the gut, which act as a satiety factor reducing meal size (Blackshaw and Grundy, 1990, Gibbs et al., 1973). This effect relies on Cckar expressed by nodose neurons (Hewson et al., 1988). Furthermore, peptide YY, produced in the gastrointestinal tract, acts through Npy2r on vagal afferents and participates in satiety signaling (Abbott et al., 2005, Koda et al., 2005). Therefore, NG13 and/or NG15 might be conveying satiety, although with partly different response profiles. Although both express Cckar, Cckar is very high in NG13. This neuron type is also predicted to respond to secretin through its receptor Sctr and to express the intracellular ion channel Trpc6, which is activated by diacylglycerol. In contrast, NG15 expresses Cckbr, which also is a receptor for gastrin. The NG13 and NG15 neuron types likely, at least partly, overlap with the genetically Glp1r-Cre-labeled neurons because most of these can be activated by CCK (Williams et al., 2016). These Glp1r-Cre-labeled neurons form the intraganglionic laminar endings (IGLEs) present in the esophagus, stomach, and proximal small intestine, involved in detecting both stretch and satiety signals from the gut. So, although receptors for some gut hormones and nutrients (Chambers et al., 2013) are present in specific nodose neuron types (for example, for serotonin, CCK, peptide YY, and fatty acids), others are not (for example, glucagon-like peptide 1 [Glp1r], ghrelin [Ghsr], and leptin [Lepr]), although we cannot exclude the possibility that the expression is below detection limits.

Npy2r is also expressed in NG14 and NG16. Npy2r+ nodose neurons are slowly conducting C-fibers, consistent with our prediction and with the finding that artificially activating these neurons results in rapid and shallow breathing (Chang et al., 2015). If Cckar-expressing neurons (NG13 and NG15) represent vagal IGLEs, as previously discussed, and these are different neuron types to pulmonary types, NG14 and/or NG16 could be speculated to include unmyelinated pulmonary afferents affecting the rate and tidal volume of breathing. Interestingly, NG12, NG14, and NG16 all express the general chemosensor channel Trpa1 and bioactive lipid receptors (Lpar3, Gpr174, and S1pr3), suggesting that these neuron types are especially tuned to sense harmful or inflammatory signaling.

NG17 and NG18 express Piezo1, Htr3a/b, Gpr65, and Ntsr1. These neurons also express Cysltr2, Gpr174, and S1pr3, consistent with previous reports of co-localization of Gpr65 with Cysltr2 and S1pr3 (Egerod et al., 2018). These are predicted unmyelinated or lightly myelinated nutrient detectors with polymodal properties, hence, being both chemosensors and mechanosensors because Piezo1, like Piezo2, is a low-threshold, mechanoactivated ion channel. Grp65+ neurons are activated by an Htr3a-selective agonist (Williams et al., 2016), consistent with expression of Htr3a in NG17 and NG18. Grp65+ neurons display extensive mucosal innervation of intestinal villi in the duodenal bulb immediately adjacent to the pyloric sphincter, with only sparse innervation of the rest of duodenum and small intestine and little innervation of lung (Chang et al., 2015). These neurons are sensitive to nutrients without any robust response to intestinal distension. Optogenetic activation of vagal Grp65-Cre neurons leads to a blockade of gastric contractions. These neuron types have, therefore, been proposed as sense nutrients that also control the pulsatile rhythm of food entry into the intestine (Williams et al., 2016).

In conclusion, jugular ganglion viscerosensory functions are carried out by neuron types molecularly similar to cutaneous somatosensation. For nodose ganglion, our results reveal an unanticipated cellular diversity underlying vagus nerve sensory functions. Based on predictions, we tentatively propose the following: pulmonary volume detecting Aβ-LTMRs (NG1), Aβ stretch activated LTMRs (NG2), A-fiber baroreceptor neurons (NG3), gastric tension mechanoreceptors (NG11), gastrointestinal IGLEs-hormone sensors (NG13 and/or NG15), unmyelinated pulmonary nociceptors (NG14 and/or NG16), and gastric nutrient detectors (NG17 and NG18). However, these predictions remain educated guesses until future experiments confirm or refute our functional assignments of the neuronal types. The function of the remaining neuron types cannot be estimated based on already published knowledge, although the expression patterns are consistent with the general conclusions that NG4, NG5, and NG6 could be chemosensors, NG7–NG10 could be polymodal mehano- and chemo-sensors, and finally, NG12 could be a nociceptor-like chemosensitive neuron type. However, by providing insights into the molecular composition of these neuron types and identification of unique markers to target them for functional studies, we believe that their morphology, targets of innervation, and functional role can now be determined. Thus, we think that our results provide the cellular framework for the vagal sensory system, which is essential for somatic sensation and for visceral control of the respiratory, gastrointestinal, and cardiovascular systems.

STAR★Methods

Key Resources Table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| TrypLE Express | Life Technologies | Cat#12605-010 |

| Papain | Worthington Biochemical | Cat#LK003172 |

| Collagenase/Dispase | Roche | Cat#11097113001 |

| Neurobasal-A | GIBCO | Cat#10888 |

| L-Glutamine | GIBCO | Cat#25030-123 |

| B27 | GIBCO | Cat#17504-044 |

| Penicillin/Steptamycin | Sigma | Cat#P4458 |

| Optiprep Density Solution | Sigma | Cat#D1556 |

| DNase I | Worthington Biochemical | Cat#LK003172 |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| RNAscope Fluorescent Multiplex Reagent Kit v2 | Advanced Cell Diagnostics | Cat#320850 |

| RNAscope® Probe- Mm-Trpa1 | Advanced Cell Diagnostics | Cat#400211 |

| RNAscope® Probe- Mm-Tmem233 | Cat#519851 | |

| RNAscope® Probe- Mm-Uts2b | Cat#468331 | |

| RNAscope® Probe- Mm-Gata3 | Cat#403321 | |

| RNAscope® Probe- Mm-Slc17a7 | Cat#416631 | |

| RNAscope® Probe- Mm-Itm2a | Cat#549381 | |

| RNAscope® Probe- Mm-Mrgprd | Cat#417921 | |

| RNAscope® Probe- Mm-Wfdc2 | Cat#440031 | |

| RNAscope® Probe- Mm-Osmr | Cat#427081 | |

| RNAscope® Probe- Mm-Gpr65-C2 | Cat#431431-C2 | |

| RNAscope® Probe- Mm-Piezo-C2 | Cat#400191-C2 | |

| RNAscope® Probe- Mm-Vip-C2 | Cat#415961-C2 | |

| RNAscope® Probe- Mm-Car8-C2 | Cat#514171-C2 | |

| RNAscope® Probe- Mm-Rbp4-C2 | Cat#508501-C2 | |

| RNAscope® Probe- Mm-Gabra1-C2 | Cat#435351-C2 | |

| RNAscope® Probe- Mm-Kcnq3-C2 | Cat#444261-C2 | |

| RNAscope® Probe- Mm-Kcna1-O1-C2 | Cat#481921-C2 | |

| RNAscope® Probe- Mm-Aqp1-C2 | Cat#504741-C2 | |

| RNAscope® Probe- Mm-Prdm12-C2 | Cat#524371-C2 | |

| RNAscope® Probe- Mm-Phox2b-C3 | Cat#407861-C3 | |

| RNAscope® Probe- Mm-Igf1-C3 | Cat#443901-C3 | |

| RNAscope® Probe- Mm-Foxp2-C3 | Cat#433211-C3 | |

| RNAscope® Probe- Mm-Kit-C3 | Cat#314151-C3 | |

| RNAscope® Probe- Mm-Nefh-C3 | Cat#495131-C3 | |

| RNAscope® Probe- Mm-Meis2 | Cat#436371 | |

| Deposited Data | ||

| Raw and processed data | This paper | GEO: GSE124312 |

| DRG scRNA-seq data | Zeisel et al., 2018 | http://loom.linnarssonlab.org/clone/Mousebrain.org.level6/L6_Peripheral_sensory_neurons.loom |

| DRG scRNA-seq data | Li et al., 2016 | GEO: GSE63576 |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| Mouse: C57BL/6JRj | JANVIER LABS | C57BL/6JRj |

| Mouse: Slc17a6tm2(cre)Lowl | The Jackson Laboratory | Stock no: 016963 |

| Mouse: B6.Cg-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm14(CAG-tdTomato)Hze/J | The Jackson Laboratory | Stock no: 007914 |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| Cell Ranger | 10x Genomics | https://github.com/10XGenomics/cellranger |

| Seurat v2.3.4 | Butler et al., 2018 | https://satijalab.org/seurat/ |

| R v3.5.1 | https://www.r-project.org | https://cran.r-project.org/ |

| MetaNeighbor | Crow et al., 2018 | https://github.com/maggiecrow/MetaNeighbor |

| Cytoscape v3.5.1 | Shannon et al., 2003 | https://cytoscape.org/ |

| RStudio v1.1 | rstudio.com | https://www.rstudio.com/products/rstudio/download/ |

| Cluego v2.5.1 | Bindea et al., 2009 | http://apps.cytoscape.org/apps/cluego |

| Python 3 | https://www.python.org/ | https://www.python.org/ |

| Fiji (ImageJ version 1.52i) | https://imagej.net/Welcome | https://imagej.net/Fiji/Downloads |

| Other | ||

| Zeiss LSM800 | Zeiss | NA |

| BD Influx | Bd Biosciences | NA |

Contact for Reagent and Resource Sharing

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Patrik Ernfors (patrik.ernfors@ki.se).

Experimental Model and Subject Details

Animals

Wild-type (C57BL/6JRj from Janvier Labs) and VGlut2-CretdTomato mice of both sexes were used in the studies. The VGlut2-CretdTomato animals were created by crossing a VGlut2-ires-Cre knock-in mouse strain (Slc17a6tm2(cre)Lowl) with a Rosa26tdTomato (Ai14) reporter mouse strain (B6.Cg-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm14(CAG-tdTomato)Hze/J); all used mice were heterozygous for both Cre and tdTomato. Age of the animals ranged from 5 up to 15 weeks of age (see paragraphs below). All experiments were done under the approval of the local ethics committee (Stockholms djurförsöksetiska nämnd) following the Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council, The Swedish Animal Welfare Act (Djurskyddslagen: SFS 1988:534), The Swedish Animal Welfare Ordinance (Djurskyddsförordningen: SFS 1988:539) and the provisions regarding the use of animals for scientific purposes: DFS 2004:15 and SJVFS 2012:26.

Method Details

Preparation of single-cell suspensions

16 wild-type mice (8M/8F; age 5 weeks), and 14 VGlut2-CretdTomato mice, (M/F; age 4.5-5 weeks) were used to prepare four batches of single-cell suspensions from the vagal ganglia. The vagal ganglia represent a ganglia merged from jugular, nodose and possibly also petrose ganglion during development. Petrosal-nodosal neurons are referred to as nodosal neurons. Per experimental day, up to 8 mice were sacrificed in the morning (around 9 a.m.) by carbon dioxide inhalation followed by decapitation. The brain was removed and the remaining part of the head was kept in freshly oxygenated cutting solution (CS; for composition see Zeisel et al., 2015) on ice until preparation of the ganglia (max. 60 min later). After the ganglia were removed the dissociation protocol was started without delay and the procedure followed a previously published protocol (Häring et al., 2018) with minor alterations. Briefly, the isolated ganglia were transferred into a 3cm plastic dish with 2.5ml of pre heated (37°C) digestion solution. The digestion solution consisted of 400μl TrypLE Express (Life Technologies; cat#12605-010), 1800μl Papain solution (Worthington Biochemical; cat#LK003178; 25U/ml in CS), 100μl DNase I (Worthington Biochemical; cat#LK003172; 1mM in CS) and 200μl Collagenase/Dispase (Roche; 20mg/ml in CS). Every 20 min tissue was triturated using glass Pasteur pipettes (pretreated with 0.5% BSA solution) with decreasing diameter. After of approximately 90 min the dissociation was complete and single cells became visible at the bottom of the plastic dish. The solution was filtered using a 40μm cell strainer (FALCON) and collected in a 15ml plastic tube containing 3ml CS and centrifuged at 100 g for 4min at 4°C. The supernatant was removed and the pellet resuspended in 0.5ml aSCF and 0.5ml complete Neurobasal medium (Neurobasal-A supplemented with L-Glutamine, B27 (all GIBCO) and Penicillin/Steptamycin (Sigma)). The cell suspension was carefully transferred with a Pasteur pipette and layered on top of an Optiprep gradient: 100μl Optiprep Density Solution (Sigma) in 450μl aCSF and 450μl complete Neurobasal; The gradient was centrifuged at 70 g for 10min at 4°C, the supernatant removed until only 100μl remained and 10μl DNaseI added to avoid cell aggregation.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting

The cell suspensions derived from VGlut2-CretdTomato animals were sorted on the BD Influx system using the BD FACS Sortware. A nozzle diameter of 140um and sheath pressure of 4.30 PSI were used with enrichment sort objective. The gating strategy, a high fluorescence intensity (85/29 [561]-tdTomato high FSC value) produced a single cloud of TdTomato+ events. A total of around 50,000 events per sorting session yielded ∼2000 TdTomato+ sorted cells. The full sorted cell populations were loaded to the 10x Chromium chip without delay.

10x Chromium Single Cell 3′ and sequencing

The capturing of single cells was performed on the Chromium Single-cell 3′ v2. For the two wild-type samples, a target of 3000 cells per run was set; however, the capture rate was below this in both samples. For the FACS samples the whole suspension was loaded for capturing. The following cDNA synthesis with PCR and library preparation were done according to the manufacturers guidelines. Sequencing was done using Illumina HiSeq 2500 Rapid Run. The Cell Ranger pipeline (version 2.0.0 or 2.1.1) together with the mouse transcriptome mm10 were used to align the reads and to generate the gene-cell matrices.

In situ hybridization and confocal microscopy

Freshly collected of ganglia were quickly frozen in OCT over dry ice and stored at −80C° until sectioning on a cryostat. The sectioning was done at 10μm thickness to five series each containing every fifth section of the ganglia. The slides were dried at RT and then kept at −80°C to preserve high RNA integrity. The in vivo confirmation of the sequencing results was achieved by applying RNAScope version 2.0 (Advanced Cell Diagnostics Inc.) using specific gene combinations. For the quantification of Phox2b+ and Prdm12+ neurons, only cell profiles containing a clear visible nucleus were counted (469 neurons, n = 3 animals). The probes were designed as well as provided by Advanced Cell Diagnostics and the stainings were performed using the RNAscope Fluorescent Multiplex Reagent Kit (cat#320850). A Zeiss LSM800 confocal microscope was used to capture the images. All image data was processed using Fiji (ImageJ version 1.52i).

Quantification and Statistical Analysis

Single-cell RNA-seq data analysis

The R-package Seurat (version 2.3.4) was used for the bulk of the single-cell data analysis. The four independent biological replicates generated a total of 1896 sequenced cells with an average of approximately 254000 reads, 6690 genes and 45000 UMIs detected per cell (see Table S1 for sample specific information). All genes expressed in less than three cells were removed and the filtered gene-barcode matrices from the individual runs were conflated together. The cell-gene matrix was further filtered for mitochondrial-DNA derived gene-expression (25% was set as the high cut-off) and the number of genes detected per cell (> 2000 as low and < 10000 as high cut-off) removing 71 cells. For feature selection, the function FindVariableGenes was used (x.low.cutoff = 0.012, x.high.cutoff = 3, y.cutoff = 0.5) yielding 2568 genes. The data was scaled to remove the effects of different UMI counts, different batches, and the percentage of mitochondrial-DNA derived gene-expression after which PCA was run using the variable genes. As the heuristic method of plotting the standard deviations of the PCs did not result in a clear cut-off, the PCs were explored further using the function JackStraw. Because this method still produced over 70 significant (p < 0.05) principal components, we chose to set the threshold at a higher level (p < 1x10−10). The PCs were visually checked from heatmaps and the remaining 50 were used for the clustering. Clustering was done using the shared nearest neighbor (SNN) modularity optimization based clustering algorithm implemented in Seurat. In order to avoid possible overclustering, we chose an approach were the cells were first clustered to the highest level of separation followed by merging of transcriptionally highly similar clusters. The primary clustering step (FindClusters; reduction.type = “pca,” dims.use = 1:50, resolution = 6, algorithm = 1 #Louvain) produced a total of 34 clusters. A t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (tSNE) was used for visual interrogation (RunTSne; tsne.method = “Rtsne,” dims.use = 1:50, perplexity = 30) and a dendrogram was built based of the PCs used for the clustering (BuildClusterTree, genes.use = NULL, pcs.use = 1:50). To control for the effective dissociation of associated SGCs, we evaluated the contribution of SGC derived RNA in the neuronal clusters. The 10 most highly expressed SGC marker genes representing nearly 12% of all RNA in the SGCs contributed on average less than 0.2% to the RNA in neurons (see Figure S1F and Table S3). Because several highly similar clusters remained after the first clustering, we used the unsupervised classifier of MetaNeighbor (see below) to classify cell-types between the remaining 34 clusters. Clusters-pairs with the highest mean AUROC scores were manually compared and the ones that lacked a transcriptome profile that could be clearly validated in-vivo were merged to produce the final 27 clusters. After the primary analysis, the non-neuronal and sympathetic clusters were removed and the remaining clusters were split into jugular and nodose subsets. The clustering dendrograms for each subset were built using the variable genes for each individual subset. The dataset from Li et al. (2016) was clustered using a similar approach and the corresponding clusters were identified and named using marker genes identified in the paper.

We used Wilcoxon rank sum test to identify cluster and node specific marker genes (Log2FC > |0.25| and padj < 0.1) as this method has been shown to perform well in in scRNA-seq experiments (Soneson and Robinson, 2018). GO analyses were done using Cytoscape v3.5.1 (Shannon et al., 2003) and the plug-in ClueGO v2.5.1 (Bindea et al., 2009) with default settings. STRING analysis (https://string-db.org/) was done taking into account only interactions with at least high confidence (> 0.7) and three or more proteins in the network. DRG cluster data was accessed via Loom (loom.linnarssonlab.org). Raw count matrices from L6 Peripheral sensory neuron loom files were converted to csv files using Python3 loompy, loaded to the R environment, and converted to a Seurat object. The DRG data from Li et al. (2016) was obtained from GEO. For all the unsupervised MetaNeighbor analyses, we combined the count matrices by getting a merged unique matrix of the intersecting genes between the two datasets/cell clusters to be compared. Highly variable genes were calculated from the combined matrixes, which allowed us to recover gene sets representative of all the cell clusters used in the comparison. The unsupervised MetaNeighbor was run according the developer’s instructions (https://github.com/maggiecrow/MetaNeighbor#unsupervised).

Data and Software Availability

The raw and processed datasets reported in this study have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) under the accession number GEO: GSE124312.

Additional Resources

We have developed an interactive application to enable the mining of the analyzed expression data. This application is available at https://ernforsgroup.shinyapps.io/vagalsensoryneurons/.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the Science for Life Laboratory and the National Genomics Infrastructure for providing excellent support. This work was supported by the Swedish Medical Research Council, Knut and Alice Wallenbergs Foundation (Wallenberg Scholar and Wallenberg project grant), SFO grant (StratNeuro), Wellcome Trust (Pain Consortium), European Research Council advanced grant (PainCells 740491), and Karolinska Institutet (to P.E.); European Union Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme/European Research Council Consolidator (grant EPIScOPE 681893), and Swedish Brain Foundation (FO2017-0075 to G.C.-B.); E.A. is funded by the European Union, Horizon 2020, Marie Sklodowska Curie Actions, and grant SOLO (794689); and J.K. is supported by the Sigrid Jusélius Foundation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: J.K. and P.E.; Computational Analysis: J.K. and E.A.; Design of RNAScope Experiments: J.K. and M.H.; RNAScope Experiments: J.K.; Single-Cell Suspensions: M.H. and J.K; Writing – Review & Editing: J.K. and P.E., with input from all authors; and Supervision and Funding: P.E. and G.C-B.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: May 21, 2019

Footnotes

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2019.04.096.

Supplemental Information

References

- Abbott C.R., Monteiro M., Small C.J., Sajedi A., Smith K.L., Parkinson J.R.C., Ghatei M.A., Bloom S.R. The inhibitory effects of peripheral administration of peptide YY3–36 and glucagon-like peptide-1 on food intake are attenuated by ablation of the vagal-brainstem-hypothalamic pathway. Brain Res. 2005;1044:127–131. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Abbott, C.R., Monteiro, M., Small, C.J., Sajedi, A., Smith, K.L., Parkinson, J.R.C., Ghatei, M.A., and Bloom, S.R. (2005). The inhibitory effects of peripheral administration of peptide YY3-36 and glucagon-like peptide-1 on food intake are attenuated by ablation of the vagal-brainstem-hypothalamic pathway. Brain Res. 1044, 127-131. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bindea G., Mlecnik B., Hackl H., Charoentong P., Tosolini M., Kirilovsky A., Fridman W.-H., Pagès F., Trajanoski Z., Galon J. ClueGO: a Cytoscape plug-in to decipher functionally grouped gene ontology and pathway annotation networks. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1091–1093. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Bindea, G., Mlecnik, B., Hackl, H., Charoentong, P., Tosolini, M., Kirilovsky, A., Fridman, W.-H., Pages, F., Trajanoski, Z., and Galon, J. (2009). ClueGO: a Cytoscape plug-in to decipher functionally grouped gene ontology and pathway annotation networks. Bioinformatics 25, 1091-1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Björnsdotter M., Morrison I., Olausson H. Feeling good: on the role of C fiber mediated touch in interoception. Exp. Brain Res. 2010;207:149–155. doi: 10.1007/s00221-010-2408-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Bjornsdotter, M., Morrison, I., and Olausson, H. (2010). Feeling good: on the role of C fiber mediated touch in interoception. Exp. Brain Res. 207, 149-155. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Blackshaw L.A., Grundy D. Effects of cholecystokinin (CCK-8) on two classes of gastroduodenal vagal afferent fibre. J. Auton. Nerv. Syst. 1990;31:191–201. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(90)90185-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Blackshaw, L.A., and Grundy, D. (1990). Effects of cholecystokinin (CCK-8) on two classes of gastroduodenal vagal afferent fibre. J. Auton. Nerv. Syst. 31, 191-201. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Brookes S.J.H., Spencer N.J., Costa M., Zagorodnyuk V.P. Extrinsic primary afferent signalling in the gut. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013;10:286–296. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Brookes, S.J.H., Spencer, N.J., Costa, M., and Zagorodnyuk, V.P. (2013). Extrinsic primary afferent signalling in the gut. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 10, 286-296. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Brouns I., Pintelon I., De Proost I., Alewaters R., Timmermans J.-P., Adriaensen D. Neurochemical characterisation of sensory receptors in airway smooth muscle: comparison with pulmonary neuroepithelial bodies. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2006;125:351–367. doi: 10.1007/s00418-005-0078-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Brouns, I., Pintelon, I., De Proost, I., Alewaters, R., Timmermans, J.-P., and Adriaensen, D. (2006). Neurochemical characterisation of sensory receptors in airway smooth muscle: comparison with pulmonary neuroepithelial bodies. Histochem. Cell Biol. 125, 351-367. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Butler A., Hoffman P., Smibert P., Papalexi E., Satija R. Integrating single-cell transcriptomic data across different conditions, technologies, and species. Nature Biotechnology. 2018;36:411–420. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Butler, A., Hoffman, P., Smibert, P., Papalexi, E., and Satija, R. (2018). Integrating single-cell transcriptomic data across different conditions, technologies, and species. Nature Biotechnology 36, 411-420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Carr M.J., Undem B.J. Bronchopulmonary afferent nerves. Respirology. 2003;8:291–301. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1843.2003.00473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Carr, M.J., and Undem, B.J. (2003). Bronchopulmonary afferent nerves. Respirology 8, 291-301. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Cavanaugh D.J., Lee H., Lo L., Shields S.D., Zylka M.J., Basbaum A.I., Anderson D.J. Distinct subsets of unmyelinated primary sensory fibers mediate behavioral responses to noxious thermal and mechanical stimuli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:9075–9080. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901507106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Cavanaugh, D.J., Lee, H., Lo, L., Shields, S.D., Zylka, M.J., Basbaum, A.I., and Anderson, D.J. (2009). Distinct subsets of unmyelinated primary sensory fibers mediate behavioral responses to noxious thermal and mechanical stimuli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 9075-9080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chambers A.P., Sandoval D.A., Seeley R.J. Integration of satiety signals by the central nervous system. Curr. Biol. 2013;23:R379–R388. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Chambers, A.P., Sandoval, D.A., and Seeley, R.J. (2013). Integration of satiety signals by the central nervous system. Curr. Biol. 23, R379-R388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chang R.B., Strochlic D.E., Williams E.K., Umans B.D., Liberles S.D. Vagal sensory neuron subtypes that differentially control breathing. Cell. 2015;161:622–633. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Chang, R.B., Strochlic, D.E., Williams, E.K., Umans, B.D., and Liberles, S.D. (2015). Vagal sensory neuron subtypes that differentially control breathing. Cell 161, 622-633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chen Y.-C., Auer-Grumbach M., Matsukawa S., Zitzelsberger M., Themistocleous A.C., Strom T.M., Samara C., Moore A.W., Cho L.T.-Y., Young G.T. Transcriptional regulator PRDM12 is essential for human pain perception. Nat. Genet. 2015;47:803–808. doi: 10.1038/ng.3308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Chen, Y.-C., Auer-Grumbach, M., Matsukawa, S., Zitzelsberger, M., Themistocleous, A.C., Strom, T.M., Samara, C., Moore, A.W., Cho, L.T.-Y., Young, G.T., et al. (2015). Transcriptional regulator PRDM12 is essential for human pain perception. Nat. Genet. 47, 803-808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Crow M., Paul A., Ballouz S., Huang Z.J., Gillis J. Characterizing the replicability of cell types defined by single cell RNA-sequencing data using MetaNeighbor. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:884. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03282-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Crow, M., Paul, A., Ballouz, S., Huang, Z.J., and Gillis, J. (2018). Characterizing the replicability of cell types defined by single cell RNA-sequencing data using MetaNeighbor. Nat. Commun. 9, 884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- D’Autréaux F., Coppola E., Hirsch M.-R., Birchmeier C., Brunet J.-F. Homeoprotein Phox2b commands a somatic-to-visceral switch in cranial sensory pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:20018–20023. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110416108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; D’Autreaux, F., Coppola, E., Hirsch, M.-R., Birchmeier, C., and Brunet, J.-F. (2011). Homeoprotein Phox2b commands a somatic-to-visceral switch in cranial sensory pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 20018-20023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Dauger S., Pattyn A., Lofaso F., Gaultier C., Goridis C., Gallego J., Brunet J.-F. Phox2b controls the development of peripheral chemoreceptors and afferent visceral pathways. Development. 2003;130:6635–6642. doi: 10.1242/dev.00866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Dauger, S., Pattyn, A., Lofaso, F., Gaultier, C., Goridis, C., Gallego, J., and Brunet, J.-F. (2003). Phox2b controls the development of peripheral chemoreceptors and afferent visceral pathways. Development 130, 6635-6642. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Egerod K.L., Petersen N., Timshel P.N., Rekling J.C., Wang Y., Liu Q., Schwartz T.W., Gautron L. Profiling of G protein-coupled receptors in vagal afferents reveals novel gut-to-brain sensing mechanisms. Mol. Metab. 2018;12:62–75. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2018.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Egerod, K.L., Petersen, N., Timshel, P.N., Rekling, J.C., Wang, Y., Liu, Q., Schwartz, T.W., and Gautron, L. (2018). Profiling of G protein-coupled receptors in vagal afferents reveals novel gut-to-brain sensing mechanisms. Mol. Metab. 12, 62-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Emery E.C., Ernfors P. Dorsal root ganglion neuron types and their functional specialization. In: Wood J.N., editor. The Oxford Handbook of the Neurobiology of Pain. Oxford University Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]; Emery, E.C., and Ernfors, P. (2018). Dorsal root ganglion neuron types and their functional specialization. In The Oxford Handbook of the Neurobiology of Pain, J.N. Wood, ed. (Oxford University Press).

- Ernfors P., Lee K.F., Kucera J., Jaenisch R. Lack of neurotrophin-3 leads to deficiencies in the peripheral nervous system and loss of limb proprioceptive afferents. Cell. 1994;77:503–512. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90213-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Ernfors, P., Lee, K.F., Kucera, J., and Jaenisch, R. (1994). Lack of neurotrophin-3 leads to deficiencies in the peripheral nervous system and loss of limb proprioceptive afferents. Cell 77, 503-512. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Frisby C.L., Mattsson J.P., Jensen J.M., Lehmann A., Dent J., Blackshaw L.A. Inhibition of transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxation and gastroesophageal reflux by metabotropic glutamate receptor ligands. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:995–1004. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.06.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Frisby, C.L., Mattsson, J.P., Jensen, J.M., Lehmann, A., Dent, J., and Blackshaw, L.A. (2005). Inhibition of transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxation and gastroesophageal reflux by metabotropic glutamate receptor ligands. Gastroenterology 129, 995-1004. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gibbs J., Young R.C., Smith G.P. Cholecystokinin elicits satiety in rats with open gastric fistulas. Nature. 1973;245:323–325. doi: 10.1038/245323a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Gibbs, J., Young, R.C., and Smith, G.P. (1973). Cholecystokinin elicits satiety in rats with open gastric fistulas. Nature 245, 323-325. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gu Q., Lee L.-Y. Characterization of acid signaling in rat vagal pulmonary sensory neurons. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2006;291:L58–L65. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00517.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Gu, Q., and Lee, L.-Y. (2006). Characterization of acid signaling in rat vagal pulmonary sensory neurons. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 291, L58-L65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Han L., Ma C., Liu Q., Weng H.-J., Cui Y., Tang Z., Kim Y., Nie H., Qu L., Patel K.N. A subpopulation of nociceptors specifically linked to itch. Nat. Neurosci. 2013;16:174–182. doi: 10.1038/nn.3289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Han, L., Ma, C., Liu, Q., Weng, H.-J., Cui, Y., Tang, Z., Kim, Y., Nie, H., Qu, L., Patel, K.N., et al. (2013). A subpopulation of nociceptors specifically linked to itch. Nat. Neurosci. 16, 174-182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Han W., Tellez L.A., Perkins M.H., Perez I.O., Qu T., Ferreira J., Ferreira T.L., Quinn D., Liu Z.-W., Gao X.-B. A Neural Circuit for Gut-Induced Reward. Cell. 2018;175:665–678.e23. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.08.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Han, W., Tellez, L.A., Perkins, M.H., Perez, I.O., Qu, T., Ferreira, J., Ferreira, T.L., Quinn, D., Liu, Z.-W., Gao, X.-B., et al. (2018). A Neural Circuit for Gut-Induced Reward. Cell 175, 665-678.e23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Häring M., Zeisel A., Hochgerner H., Rinwa P., Jakobsson J.E.T., Lönnerberg P., La Manno G., Sharma N., Borgius L., Kiehn O. Neuronal atlas of the dorsal horn defines its architecture and links sensory input to transcriptional cell types. Nat. Neurosci. 2018;21:869–880. doi: 10.1038/s41593-018-0141-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Haring, M., Zeisel, A., Hochgerner, H., Rinwa, P., Jakobsson, J.E.T., Lonnerberg, P., La Manno, G., Sharma, N., Borgius, L., Kiehn, O., et al. (2018). Neuronal atlas of the dorsal horn defines its architecture and links sensory input to transcriptional cell types. Nat. Neurosci. 21, 869-880. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hayes D., Jr., Collins P.B., Khosravi M., Lin R.-L., Lee L.-Y. Bronchoconstriction triggered by breathing hot humid air in patients with asthma: role of cholinergic reflex. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2012;185:1190–1196. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201201-0088OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Hayes, D., Jr., Collins, P.B., Khosravi, M., Lin, R.-L., and Lee, L.-Y. (2012). Bronchoconstriction triggered by breathing hot humid air in patients with asthma: role of cholinergic reflex. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 185, 1190-1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hewson G., Leighton G.E., Hill R.G., Hughes J. The cholecystokinin receptor antagonist L364,718 increases food intake in the rat by attenuation of the action of endogenous cholecystokinin. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1988;93:79–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1988.tb11407.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Hewson, G., Leighton, G.E., Hill, R.G., and Hughes, J. (1988). The cholecystokinin receptor antagonist L364,718 increases food intake in the rat by attenuation of the action of endogenous cholecystokinin. Br. J. Pharmacol. 93, 79-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Jensen J., Lehmann A., Uvebrant A., Carlsson A., Jerndal G., Nilsson K., Frisby C., Blackshaw L.A., Mattsson J.P. Transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxations in dogs are inhibited by a metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 antagonist. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2005;519:154–157. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Jensen, J., Lehmann, A., Uvebrant, A., Carlsson, A., Jerndal, G., Nilsson, K., Frisby, C., Blackshaw, L.A., and Mattsson, J.P. (2005). Transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxations in dogs are inhibited by a metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 antagonist. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 519, 154-157. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Khosravi M., Collins P.B., Lin R.-L., Hayes D., Jr., Smith J.A., Lee L.-Y. Breathing hot humid air induces airway irritation and cough in patients with allergic rhinitis. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2014;198:13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2014.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Khosravi, M., Collins, P.B., Lin, R.-L., Hayes, D., Jr., Smith, J.A., and Lee, L.-Y. (2014). Breathing hot humid air induces airway irritation and cough in patients with allergic rhinitis. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 198, 13-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kirchheim H.R. Systemic arterial baroreceptor reflexes. Physiol. Rev. 1976;56:100–177. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1976.56.1.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Kirchheim, H.R. (1976). Systemic arterial baroreceptor reflexes. Physiol. Rev. 56, 100-177. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Knowlton G.C., Larrabee M.G. A unitary analysis of pulmonary volume receptors. Am. J. Physiol. 1946;147:100–114. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1946.147.1.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Knowlton, G.C., and Larrabee, M.G. (1946). A unitary analysis of pulmonary volume receptors. Am. J. Physiol. 147, 100-114. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Koda S., Date Y., Murakami N., Shimbara T., Hanada T., Toshinai K., Niijima A., Furuya M., Inomata N., Osuye K., Nakazato M. The role of the vagal nerve in peripheral PYY3-36-induced feeding reduction in rats. Endocrinology. 2005;146:2369–2375. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Koda, S., Date, Y., Murakami, N., Shimbara, T., Hanada, T., Toshinai, K., Niijima, A., Furuya, M., Inomata, N., Osuye, K., and Nakazato, M. (2005). The role of the vagal nerve in peripheral PYY3-36-induced feeding reduction in rats. Endocrinology 146, 2369-2375. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kollarik M., Undem B.J. Mechanisms of acid-induced activation of airway afferent nerve fibres in guinea-pig. J. Physiol. 2002;543:591–600. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.022848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Kollarik, M., and Undem, B.J. (2002). Mechanisms of acid-induced activation of airway afferent nerve fibres in guinea-pig. J. Physiol. 543, 591-600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Le Douarin N.M. Ontogeny of the peripheral nervous system from the neural crest and the placodes. A developmental model studied on the basis of the quail-chick chimaera system. Harvey Lect. 1984;80:137–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Le Douarin, N.M. (1984). Ontogeny of the peripheral nervous system from the neural crest and the placodes. A developmental model studied on the basis of the quail-chick chimaera system. Harvey Lect. 80, 137-186. [PubMed]

- Lee L.Y., Pisarri T.E. Afferent properties and reflex functions of bronchopulmonary C-fibers. Respir. Physiol. 2001;125:47–65. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(00)00204-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Lee, L.Y., and Pisarri, T.E. (2001). Afferent properties and reflex functions of bronchopulmonary C-fibers. Respir. Physiol. 125, 47-65. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lee L.-Y., Yu J. Sensory nerves in lung and airways. Compr. Physiol. 2014;4:287–324. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c130020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Lee, L.-Y., and Yu, J. (2014). Sensory nerves in lung and airways. Compr. Physiol. 4, 287-324. [DOI] [PubMed]