Abstract

Carbon availability is a major regulatory factor in plant growth and development. Cytokinins, plant hormones that play important roles in various aspects of growth and development, have been implicated in the carbon-dependent regulation of plant growth; however, the details of their involvement remain to be elucidated. Here, we report that sugar-induced cytokinin biosynthesis plays a role in growth enhancement under elevated CO2 in Arabidopsis thaliana. Growing Arabidopsis seedlings under elevated CO2 resulted in an accumulation of cytokinin precursors that preceded growth enhancement. In roots, elevated CO2 induced two genes involved in de novo cytokinin biosynthesis: an adenosine phosphate-isopentenyltransferase gene, AtIPT3, and a cytochrome P450 monooxygenase gene, CYP735A2. The expression of these genes was inhibited by a photosynthesis inhibitor, DCMU, under elevated CO2, and was enhanced by sugar supplements, indicating that photosynthetically generated sugars are responsible for the induction. Consistently, cytokinin precursor accumulation was enhanced by sugar supplements. Cytokinin biosynthetic mutants were impaired in growth enhancement under elevated CO2, demonstrating the involvement of de novo cytokinin biosynthesis for a robust growth response. We propose that plants employ a system to regulate growth in response to elevated CO2 in which photosynthetically generated sugars induce de novo cytokinin biosynthesis for growth regulation.

Subject terms: Cytokinin, Plant physiology

Introduction

Being sessile, plants integrate environmental and internal cues and regulate physiological and morphological processes accordingly to optimize growth and development. Because multicellular higher plants consist of organs with different functions, for example photosynthesizing leaves and roots that absorb water and inorganic nutrients, the responses must be coordinated at the whole plant level. Local as well as long-distance signalling between cells and organs via signalling molecules such as sugars and plant hormones are vital for this coordination1–6

Cytokinins (CKs) are a class of plant hormones that play a central role in the regulation of numerous aspects of plant growth and development acting as local and long-distance signals7–11. Naturally occurring CKs are mostly N6-prenylated adenine derivatives; N6-(∆2-isopentenyl)adenine (iP), trans-zeatin (tZ) and their conjugates (iP-type and tZ-type CKs, respectively) are the major forms in Arabidopsis thaliana10–12. CK activity is controlled at diverse levels, including CK quantity and modification. CK quantity is regulated mostly at the levels of de novo biosynthesis and degradation catalysed by adenosine phosphate-isopentenyltransferase (IPT) and CK oxidase/dehydrogenase (CKX), respectively13–16. Side-chain modification to form tZ-type CKs by cytochrome P450 monooxygenase CYP735A specifies CK activity toward shoot growth17,18. Recently, CK translocation via the vascular system was reported to also be important19–21. Shoot-to-root translocation of CK via phloem is critical for root vascular patterning, whereas root-to-shoot translocation via xylem mediated by ABCG14 regulates shoot growth and development. Regulation of CK activity is relevant to various plant developmental processes and environmental responses such as shoot apical meristem activity, branching, stress and nutritional responses22–28.

Because plants are autotrophs that rely on photosynthesis to gain most of their building materials and energy, carbon availability is a major factor defining plant growth and development29–32. To maximize fitness, long-distance communication is required for plants to balance the growth of photosynthesizing leaves and that of carbon consuming roots in response to carbon availability6,33. In various plant species, elevated CO2 (i.e. high carbon availability) generally results in growth acceleration of both shoots and roots, although the root-to-shoot mass ratios are variable depending on species and environmental conditions25,26,29,34–37. CKs have been implicated in growth acceleration because cell division and cell differentiation in the meristem are influenced by CKs and are often accompanied by CK accumulation26,38. In addition, an increase in tZ-type CKs was detected in the xylem sap of cotton and tobacco plants grown under elevated CO2, implying that tZ-type CKs have a role as root-to-shoot signals under elevated CO2 conditions25,39. However, how CKs accumulate and whether the accumulation and root-to-shoot translocation of CK is relevant to growth acceleration under elevated CO2 (i.e. high carbon availability) remains to be determined.

In this study, we revealed that enhancement of de novo biosynthesis is responsible for CK accumulation under elevated CO2 and that the enhancement is triggered by sugars derived from photosynthesis. Detailed growth analyses of mutants defective in cytokinin de novo biosynthesis (ipt3 ipt5 ipt7 and cyp735a1 cyp735a2) revealed that accumulation of tZ-type cytokinins through de novo biosynthesis plays a role in a robust growth response to elevated CO2 by both shoots and roots. Altogether, these results suggest that the de novo tZ-type CK biosynthesis triggered by photosynthetically generated sugars contributes to growth enhancement under elevated CO2 in Arabidopsis.

Results

Elevated CO2 increases cytokinin precursor concentrations in shoots and roots

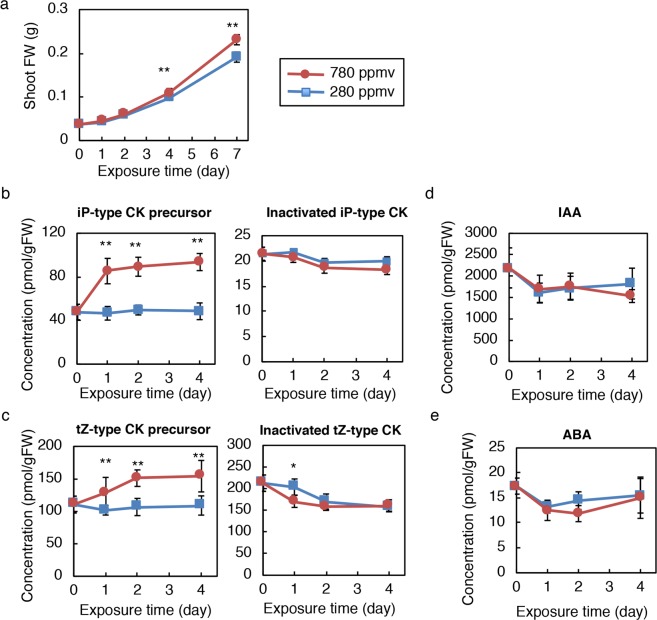

To examine the effects of elevated CO2 on growth and CK levels, plants were grown under low [280 parts per million by volume (ppmv)] and high CO2 (780 ppmv) on soil. Two hundred and eighty ppmv is the pre-industrial atmospheric concentration and 780 ppmv is a value close to the median of values predicted at the end of this century40. When wild-type Arabidopsis Col-0 were germinated and grown under low or high CO2 with a 12 h light/12 h dark photoperiod for four weeks, high CO2-grown plants deposited more biomass and developed more leaf area and rosette leaves than low CO2-grown plants did, as described previously (Supplementary Fig. S132,41,42). Using the same growth conditions, we analysed changes in the CK concentration following exposure to high CO2. Sixteen-day-old Col-0 plants grown in low CO2 were transferred to low or high CO2, and CK concentrations in the whole shoot were followed for four days. Under these conditions, significant differences in shoot fresh weight between high and low CO2-treated plants became evident from day 4 onward (Fig. 1a). The levels of iP-type CK precursors (iPR and iPRPs) and tZ-type CK precursors (tZR and tZRPs) in high CO2-treated shoots increased after one day and stayed high until day 4 compared with those of low CO2-treated plants (Fig. 1b,c). On the other hand, concentrations of other CK metabolites including inactivated iP-type CKs (iP7G and iP9G), and tZ-type CKs (tZ7G, tZ9G, tZOG, tZROG, and tZRPsOG) did not change consistently during the period of observation (Fig. 1b,c; Supplementary Table S1). Furthermore, the high CO2-treatment did not significantly affect the levels of other plant hormones, including a gibberellin precursor (GA24), IAA, and ABA (Fig. 1d,e; Supplementary Table S1). These results showed that iP-type and tZ-type CK precursors accumulate in the shoot prior to growth enhancement at high CO2 under our experimental conditions.

Figure 1.

Effects of high CO2 on growth and hormone concentrations in soil-grown plants. Shoot fresh weight (a), concentrations of iP-type cytokinin (CK) precursors and inactivated iP-type CKs (b), concentrations of tZ-type CK precursors and inactivated tZ-type CKs (c), IAA concentration (d), and ABA concentration (e) of Col-0 shoots incubated at 280 ppmv or 780 ppmv CO2 for the indicated periods. Error bars represent standard deviations (a, n = 10; b–e, n = 8). Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences between 280 ppmv CO2- and 780 ppmv CO2-treated samples at the same exposure time (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; Student’s t-test). FW, fresh weight; tZ, trans-zeatin; iP, N6-(∆2-isopentenyl)adenine; iP-type CK precursor, sum of iPR and iPRPs; inactivated iP-type CK, sum of iP7G and iP9G; tZ-type CK precursor, sum of tZR and tZRPs; inactivated tZ-type CK, sum of tZ7G, tZZ9G, tZOG, tZROG, and tZRPsOG. The concentrations of all quantified hormones are shown in Supplementary Table S1.

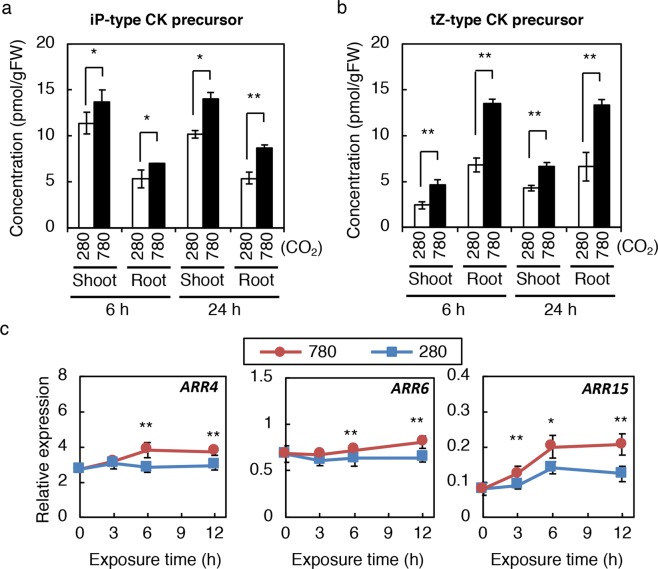

Next, we employed a growth system in which Col-0 seedlings were germinated and grown on half-strength MS (1/2 MS) agar plates placed vertically to allow the analysis of both shoots and roots. Twelve-day-old wild-type seedlings grown under continuous light in low CO2 were transferred to low or high CO2, and the CK concentrations in shoots and roots were measured after 6 h and 24 h. The basal level of tZ, tZRPs and tZ-N-conjugates in this measurement (Supplementary Table S2) was very different from that in soil-grown plants (Supplementary Table S1). This is possibly due to differences in growth conditions and plant ages, as a similar trend has been observed previously17. Accumulation of tZ, and iP-type and tZ-type precursors became evident in shoots and roots as early as 6 h after commencing the high CO2-treatment and continued until 24 h, whereas the levels of other CK metabolites did not consistently change (Fig. 2a,b; Supplementary Table S2).

Figure 2.

Cytokinin levels and activity in seedlings exposed to high CO2. (a,b) Cytokinin (CK) levels in shoots and roots of Col-0 seedlings exposed to low and high CO2. iP-type CK precursor levels (a) and tZ-type CK precursor levels (b) in shoots and roots are presented. (c) Expression levels of type-A ARR genes in Col-0 seedlings exposed to low and high CO2. Transcript levels of ARR4, ARR6, and ARR15 were analysed by quantitative RT-PCR. Expression levels were normalized using At4g34270 as an internal control. Twelve-day-old seedlings grown on 1/2 MS agar plates at 280 ppmv were exposed to 280 ppmv (280) or 780 ppmv (780) CO2 for the indicated periods. Error bars represent standard deviations of three biological replicates. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences between 280 ppmv CO2- and 780 ppmv CO2-treated samples at the same exposure time (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; Student’s t-test). FW, fresh weight; tZ, trans-zeatin; iP, N6-(∆2-isopentenyl)adenine. The concentrations of cytokinin molecular species are shown in Supplementary Table S2.

It is known that the accumulation of CK precursors generally results in increased CK activity7,43. To verify that CK signalling is activated in parallel with precursor accumulation, the expression of immediate-early CK responsive type-A ARR genes was analysed in whole seedlings treated as in Fig. 2a. As expected, ARR4, ARR6, and ARR15 were induced, with the timing of induction similar to that of CK precursor accumulation (Fig. 2c). Since recent studies on plant membrane binding and crystal structure analysis showed that precursors do not bind to Arabidopsis CK receptors44,45, one would expect that active CKs (iP and tZ) are accumulated in response to an increase in CK precursor levels. However, active CKs were not always increased significantly in our experiments (for example, Supplementary Tables S1, S2). This lack of significant change in active CK levels has been reported previously46,47 and we assume that it is because only a fraction of active CKs exists in a compartment where they can be perceived by CK receptors. Taken together, these results indicated that elevated CO2 resulted in increased CK activity, which is triggered by CK precursor accumulation in shoots and roots.

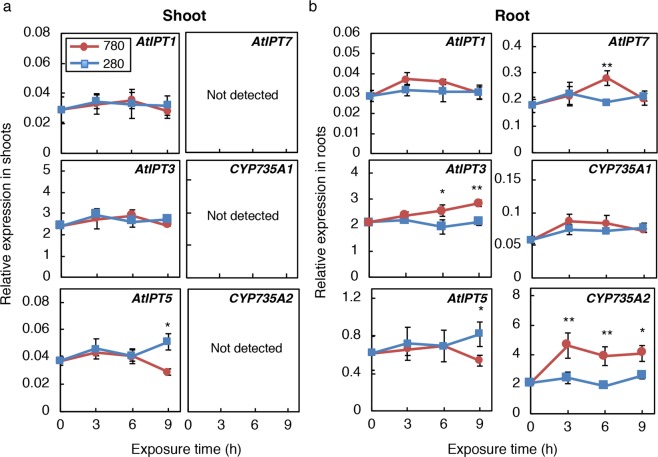

Cytokinin biosynthetic genes, AtIPT3 and CYP735A2, are up-regulated in roots under elevated CO2

Generally the accumulation of CK precursors reflects increased de novo biosynthesis7,43. The initial step of de novo CK biosynthesis is catalysed by IPT13,14, and the key step of tZ-type de novo CK biosynthesis requires CYP735A17,18. We examined the expression levels of seven IPT (AtIPT1, AtIPT3, AtIPT4, AtIPT5, AtIPT6, AtIPT7, AtIPT8) and two CYP735A (CYP735A1 and CYP735A2) genes in Arabidopsis shoots and roots of Col-0 seedlings incubated at low or high CO2 from 3 h, an earlier time point than when CK precursor accumulation was observed (up to 9 h). AtIPT4, AtIPT6, and AtIPT8 were not detected in shoots nor roots in our experimental conditions. In shoots, none of the genes examined were affected by high CO2 except for AtIPT5 that was down-regulated at 9 h (Fig. 3a). In roots, the transcript level of CYP735A2 increased after 3 h and stayed high till 9 h and that of AtIPT3 steadily accumulated after the onset of high CO2 treatment (Fig. 3b). On the other hand, the levels of the other transcripts remained unchanged or showed transient fluctuations (Fig. 3b). Down-regulation of AtIPT5 in both shoot and root might be caused by accumulated CK because AtIPT5 has been reported to be repressed by CK48. Since CK levels are determined by the balance between de novo biosynthesis and degradation, we also analysed the expression of genes encoding CK-degrading enzymes, CKX. Among seven CKXs in Arabidopsis, the expression of six genes was detected but none of these genes were down-regulated in shoots and roots under high CO2 treatment (Supplementary Fig. S2). Rather, the expression of CKX1, CKX4, CKX6, and CKX7 was transiently enhanced, possibly in response to CK accumulation (Supplementary Fig. S2). Similar CK precursor accumulation and induction of AtIPT3 and CYP735A2 were observed when seedlings were grown and treated under 12-h-light/12-h-dark cycles (Supplementary Fig. S3; Supplementary Table S3). These results suggested that the induction of AtIPT3 and CYP735A2 in roots plays a role in iP- and tZ-type CK precursor accumulation under elevated CO2.

Figure 3.

Expression of genes involved in cytokinin biosynthesis in shoots and roots upon exposure to high CO2. Transcript levels of AtIPT1, AtIPT3, AtIPT4, AtIPT5, AtIPT6, AtIPT7, AtIPT8, CYP735A1, and CYP735A2 were analysed in shoots (a) and roots (b) of Col-0 seedlings by quantitative RT-PCR. Expression levels of AtIPT4, AtIPT6, and AtIPT8 were below the detection limit in shoots and roots. Expression levels were normalized using At4g34270 as an internal control. Twelve-day-old seedlings grown on 1/2 MS agar plates at 280 ppmv were exposed to 280 ppmv (280) or 780 ppmv (780) CO2 for the indicated periods. Error bars represent standard deviations of three biological replicates. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences between 280 ppmv CO2- and 780 ppmv CO2-treated samples at the same exposure time (**p < 0.01; *p < 0.05; Student’s t-test).

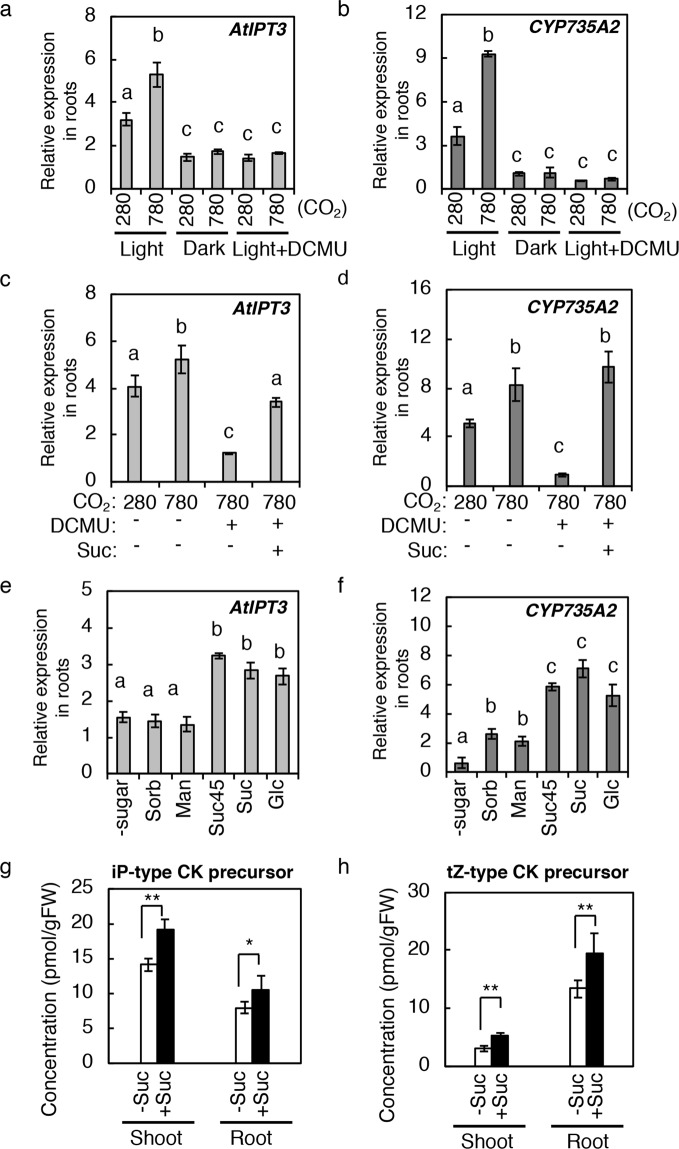

Photosynthetically generated sugars induce AtIPT3 and CYP735A2 in roots

Next, we tested the involvement of photosynthesis in the induction of AtIPT3 and CYP735A2 by incubating wild-type seedlings in the dark or by applying the photosynthesis inhibitor DCMU, which blocks electron flow from photosystem II. When seedlings were incubated in the dark or in the light with DCMU at 280 ppmv for 6 h, expression levels of AtIPT3 and CYP735A2 were reduced compared to the control (Fig. 4a,b). The induction of AtIPT3 and CYP735A2 in response to elevated CO2 was completely abolished by these treatments (Fig. 4a,b), indicating that photosynthetic activity is required for the maintenance and induction of AtIPT3 and CYP735A2 expression.

Figure 4.

Effects of photosynthesis and sugars on the expression of AtIPT3 and CYP735A2, and cytokinin levels. (a,b) Effects of dark and DCMU on AtIPT3 (a) and CYP735A2 (b) expression in Col-0 roots. Seedlings were exposed to 280 ppmv or 780 ppmv CO2 under light (Light), under light with 40 µM DCMU (Light + DCMU), or in the dark (Dark). (c,d) AtIPT3 (c) and CYP735A2 (d) expression in Col-0 seedlings treated with 40 µM DCMU in the presence (+) or absence (−) of 90 mM sucrose (Suc) and/or DCMU for six hours. (e,f) Effects of sugars on the expression of AtIPT3 (e) and CYP735A2 (f) in Col-0 roots. Seedlings were incubated on plates with 90 mM sorbitol (Sorb), mannitol (Man), sucrose (Suc), glucose (Glc), with 45 mM sucrose (Suc45), or without sugar (-sugar) for six hours at 280 ppmv CO2 in the dark. (g,h) Changes in cytokinin levels in seedlings treated with sucrose. iP-type CK precursor levels (g) and tZ-type CK precursor levels (h) in shoots and roots are presented. Twelve-day-old seedlings grown on 1/2 MS agar plates at 280 ppmv were treated with 45 mM sucrose (+Suc) or without sucrose (−Suc) at 280 ppmv for 24 h. The concentrations of cytokinin molecular species are shown in Supplementary Table S3. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences (*p < 0.05; Student’s t-test). Error bars represent standard deviations of four biological replicates. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences (*p < 0.05; Student’s t-test). Different lower-case letters indicate statistically significant differences as indicated by Tukey’s HSD test (p < 0.05). Expression levels were analysed by quantitative RT-PCR and normalized using At4g34270 as an internal control.

Elevated CO2-treatment reportedly increases endogenous sugar concentrations (e.g. fructose, glucose, and sucrose), whereas DCMU treatment reduces sugar levels31,37,49. To examine whether the DCMU-triggered attenuation of AtIPT3 and CYP735A2 induction were caused by lowered levels of sugars, we supplemented DCMU-treated seedlings with sucrose. Sucrose reversed the effect of DCMU on AtIPT3 and CYP735A2 expression (Fig. 4c,d). We also tested the effects of other sugars on AtIPT3 and CYP735A expression. Seedlings were transferred to agar plates containing metabolizable sugars (sucrose and glucose) or non-metabolizable sugars (sorbitol and mannitol) and were incubated at 280 ppmv CO2 in the dark. Metabolizable sugars were able to induce AtIPT3 and CYP735A expression (Fig. 4e,f). On the other hand, non-metabolizable sugars were ineffective in inducing AtIPT3 expression (Fig. 4e). CYP735A2 expression was induced by non-metabolizable sugars but to a much lower extent compared with metabolizable sugars (Fig. 4f). Since CYP735A2 seems to be moderately activated by osmotic stress50, the induction by non-metabolizable sugars is probably due to osmotic effects.

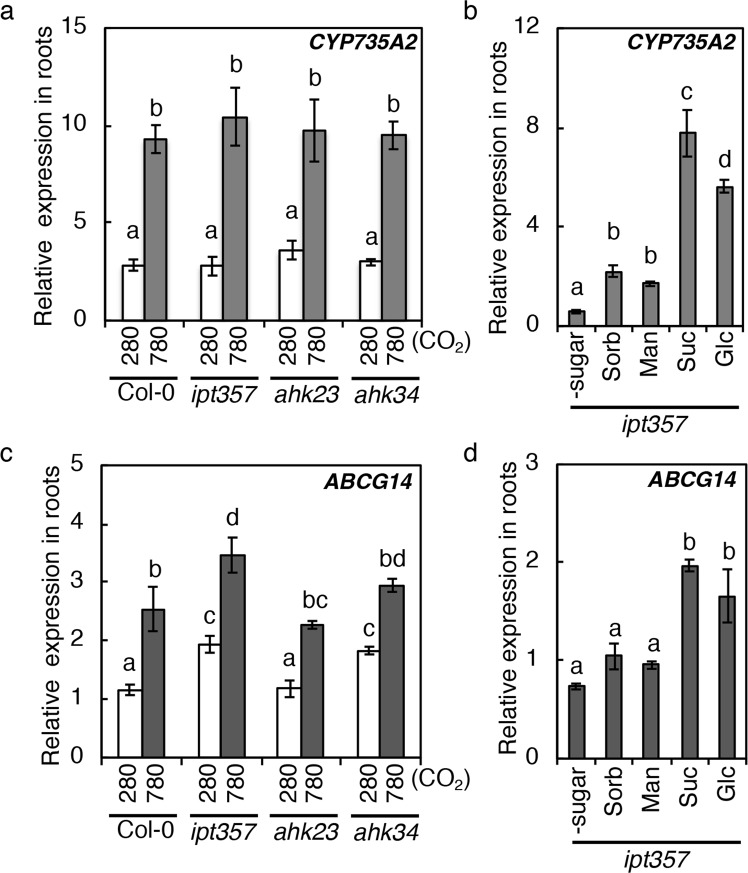

CYP735A2 is known to be a CK-inducible gene18,21. Thus we tested whether CYP735A2 induction by elevated CO2 and sugars is the result of accumulated CKs by employing ipt3 ipt5 ipt7 (ipt357) and the cytokinin receptor mutants ahk2 ahk3 and ahk3 ahk451–53 that are defective in CK biosynthesis and signalling, respectively. Elevated CO2 and sugars induced CYP735A2 expression in the mutants at a level comparable to Col-0 (Fig. 5a,b), indicating that sugars induce this gene independently of CK.

Figure 5.

Expression of CYP735A2 and ABCG14 in cytokinin biosynthetic and signaling mutants treated with high CO2 or sugars. (a,c) Wild-type (Col-0), ipt3 ipt5 ipt7 (ipt357), ahk2 ahk3 (ahk23) and ahk3 ahk4 (ahk34) seedlings grown on 1/2MS agar plates at 280 ppmv CO2 for 12 days were exposed to 280 ppmv or 780 ppmv for six hours and then roots were harvested. (b,d) ipt357 seedlings were transferred to new plates containing 90 mM of sorbitol (Sorb), mannitol (Man), sucrose (Suc) or glucose (Glc), or without any sugar (-sugar). Roots were harvested after six hours. Expression levels were analysed by quantitative real-time PCR and normalized using At4g34270 as an internal control. Error bars represent standard deviation of three biological replicates. Different lower-case letters indicate statistically significant differences as indicated by Tukey’s HSD test (p < 0.01).

These results suggested that AtIPT3 and CYP735A2 are induced in roots under elevated CO2 by sugars generated in shoots by photosynthesis. Consistent with this, sucrose treatment resulted in an accumulation of CK precursors in shoots and roots (Fig. 4g,h; Supplementary Table S4).

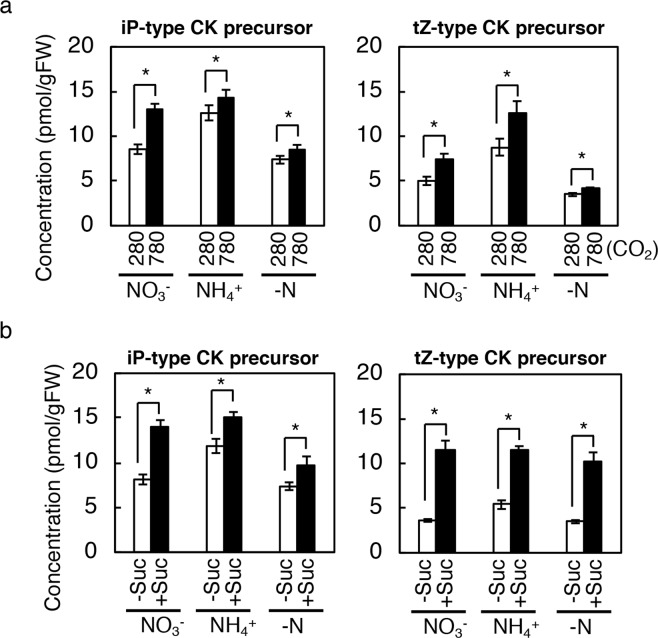

Photosynthetically generated sugars induce cytokinin precursor accumulation irrespective of the nitrate status

It is known that de novo CK biosynthesis is regulated by nitrate in Arabidopsis54. Since carbon availability is reported to influence nitrate transporter gene expression and nitrate uptake55,56, it is possible that carbon availability affects CK biosynthesis indirectly through nitrate-related pathways. To test this possibility, we measured CK levels in wild-type seedlings treated with high CO2 or sucrose, and with and without nitrate. Twelve-day-old seedlings were treated with high CO2 or sucrose on agar plates containing 10 mM KNO3, 10 mM NH4Cl, or no nitrogen source, and the CK concentrations in the whole seedling were measured after 24 h. The levels of CK precursors increased in all nitrogen conditions tested in response to high CO2 or sucrose treatment (Fig. 6; Supplementary Tables S5 and S6), suggesting that sugars induce CK precursor accumulation independent of nitrate-related pathways.

Figure 6.

Cytokinin levels in wild-type seedlings exposed to high CO2 or treated with sucrose under different nitrogen nutrient conditions. (a) Cytokinin (CK) levels in wild-type (Col-0) whole seedlings exposed to low or high CO2 under different nitrogen nutrient conditions. Seedlings were exposed to 280 ppmv (280) or 780 ppmv (780) CO2 for 24 h on modified 1/2 MS agar plates containing 10 mM KNO3 (NO3−) or 10 mM NH4Cl (NH4+), or without any nitrogen source (-N). The concentrations of cytokinin molecular species are shown in Supplementary Table S5. (b) Cytokinin levels in wild-type (Col-0) whole seedlings treated with (+Suc) or without (−Suc) 45 mM sucrose for 24 h on modified 1/2 MS agar plates containing 10 mM KNO3 (NO3−) or 10 mM NH4Cl (NH4+), or without any nitrogen source (-N). The concentrations of cytokinin molecular species are shown in Supplementary Table S6. Twelve-day-old seedlings grown at 280 ppmv were used. Error bars represent standard deviations of four biological replicates. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences (*p < 0.05; Student’s t-test). FW, fresh weight; tZ, trans-zeatin; iP, N6-(∆2-isopentenyl)adenine.

The ipt3 cyp735a2 mutant still accumulates cytokinin precursors in response to elevated CO2

Having shown the relevance of AtIPT3 and CYP735A2 in the elevated CO2-enhanced de novo CK biosynthesis, we investigated whether these processes contribute to growth enhancement under elevated CO2 by generating an ipt3 cyp735a2 double mutant. To this end, 12-day-old seedlings grown on agar plates were incubated at low or high CO2 for seven days. Fresh weight (FW) was measured before and after the treatment, and relative growth rate (RGR) was calculated. Growth differences of Col-0 between low CO2- and high CO2-incubated seedlings were clearly observed; the FW and RGR of both the shoot and the root were significantly increased by the high CO2 treatment (Supplementary Fig. S4a–c). However, no significant difference in the FW and RGR was observed between the double mutant and WT (Supplementary Fig. S4a–c). To understand this lack of growth phenotype, we analysed changes in iP- and tZ-type precursor CK levels in shoots and roots of the double mutant following exposure to high CO2. Under low CO2, the double mutant contained significantly reduced levels of iP-type CK precursors in shoots (Supplementary Fig. S4d; Supplementary Table S7). However, it accumulated both CK precursors in both organs in response to high CO2-treatment, though the levels of accumulation were generally lower compared with WT (Supplementary Fig. S4d,e; Supplementary Table S7), indicating that AtIPT3 and CYP735A2 are not the only factors mediating the elevated CO2-induced CK precursor accumulation. Together, these results suggest that the double mutant lacks a growth phenotype because it still is able to accumulate enough CKs for elevated CO2-triggered growth enhancement.

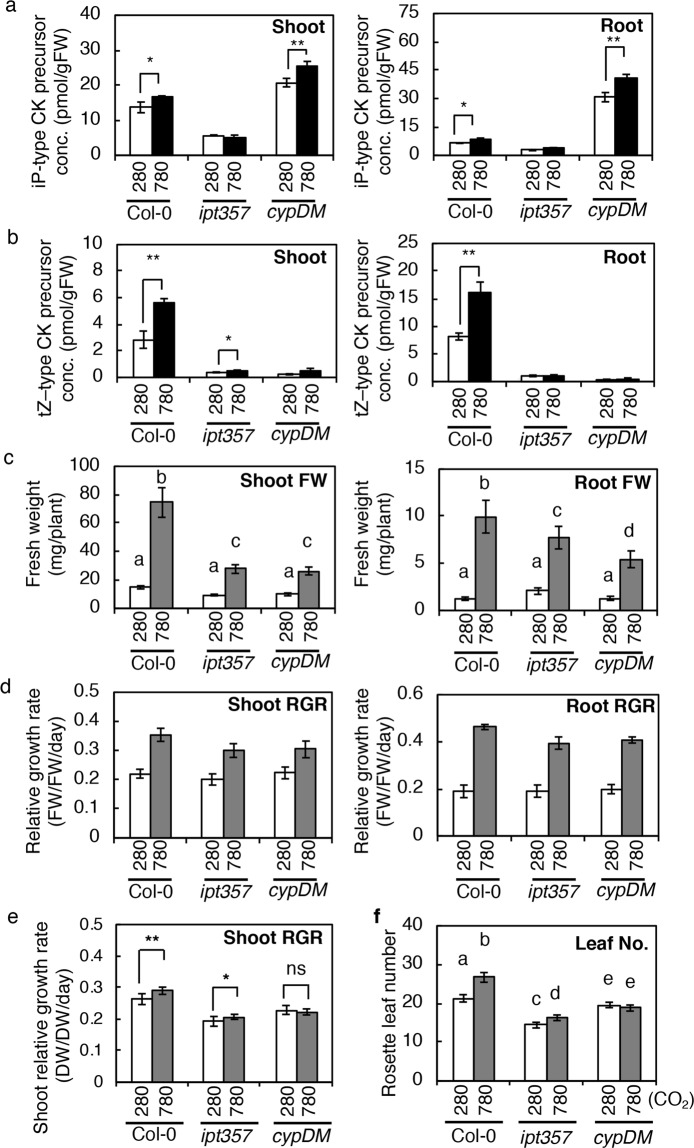

The ipt3 ipt5 ipt7 and cyp735a1 cyp735a2 mutants are impaired in elevated CO2-triggered growth enhancement

Since the ipt3 cyp735a2 double mutant still accumulated CKs in response to high CO2 (Supplementary Fig. S4d,e), we employed higher order CK-biosynthetic mutants, ipt357 and cyp735a1 cyp735a2 (cypDM). The ipt357 mutant lacks three major IPT genes57 and, thus, has a dramatically reduced ability to de novo synthesize both iP- and tZ-type CKs. The cypDM mutant lacks all CYP735A genes17 and, thus, is expected to accumulate iP-type CKs but not tZ-type CKs under elevated CO2. To verify that elevated CO2-induced de novo CK biosynthesis is attenuated in ipt357 and cypDM, the CK concentrations in shoots and roots were measured. Seedlings were grown and treated as in Fig. 2 (24 h high CO2 treatment). In the ipt357 mutant, the accumulation level of all CKs was relatively low compared with the wild type. The iP-type CK precursor concentrations were unaffected in shoots and roots, but the levels of tZ-type precursor CKs increased slightly in shoots with a high CO2 treatment (Fig. 7a,b; Supplementary Table S8). In the cypDM mutant, iP-type precursor CKs accumulated but tZ-type precursor CKs levels were consistently low in shoots and roots under elevated CO2 (Fig. 7a,b; Supplementary Table S8). These observations confirmed the inability of the mutants to accumulate CKs of the expected types under elevated CO2. These results showed that de novo CK biosynthesis, most likely mediated by IPT3, IPT5, IPT7, CYP735A1 and CYP735A2, plays an important role in CK accumulation in response to high CO2.

Figure 7.

Cytokinin levels and growth of wild-type, ipt3 ipt5 ipt7 and cyp735a1 cyp735a2 seedlings exposed to high CO2. (a,b) The concentration of iP-type cytokinin (CK) precursors (a) and tZ-type CK precursors (b) in shoots and roots of wild-type (Col-0), ipt3 ipt5 ipt7 (ipt357) and cyp735a1 cyp735a2 (cypDM) plants exposed to 280 ppmv (280) or 780 ppmv (780) CO2 for 24 h. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences (**p < 0.01; *p < 0.05; Student’s t-test). The concentrations of cytokinin molecular species are shown in Supplementary Table S7. (c,d) Fresh-weight (c) and relative growth rate (RGR) (d) of 19-day-old wild type (Col-0), ipt3 ipt5 ipt7 (ipt357), and cyp735a1 cyp735a2 (cypDM) seedlings treated under 280 ppmv (280) or 780 ppmv (780) CO2 for seven days. (d) RGR was calculated using the fresh weight (FW) data obtained previously (Supplementary Fig. S5) and after (c) low or high CO2 treatment. (e,f) Shoot growth of soil-grown wild-type, ipt3 ipt5 ipt7 and cyp735a1 cyp735a2 plants under low or high CO2. (e) Relative growth rates (RGR) of shoots of Col-0, ipt357, and cypDM grown under 280 or 780 on soil. Dry weights of shoots shown in Supplementary Fig. 6b were used to calculate the RGR. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences (**p < 0.001; *p < 0.01; not significant (ns), p > 0.01; two-way ANOVA). (f) Rosette leaf number of Col-0, ipt357, and cypDM counted at 31 DAG. Error bars represent standard deviations (a, n = 3; b, n = 3; c, n = 9; f, n = 10) and standard error (d, n = 9; e, n = 9). Lower-case letters denote statistically significant classes (Tukey’s HSD test, p < 0.05).

We then investigated whether these mutants are impaired in growth enhancement under elevated CO2. Seedlings were grown and treated on agar plates as in Supplementary Fig. S4, and the FW was measured before and after treatment, and the RGRs were calculated. In Col-0, the FW and RGR of both the shoot and the root were dramatically increased in response to high CO2 (Fig. 7c,d; Supplementary Fig. S5). The ipt357 mutant also gained more FW both in shoots and roots in high CO2 compared with the low CO2 treatment, but the extent of the increase was smaller compared with that of Col-0 (Fig. 7c). RGR analysis revealed that shoots and roots of ipt357 grew faster in high CO2 than in low CO2 but at a lower rate compared with those of Col-0, whereas the RGR in low CO2 was similar among all genotypes in this growth system (Fig. 7d). Interestingly, the cypDM mutant displayed essentially the same growth response defects to elevated CO2 as the ipt357 mutant (Fig. 7c,d), showing that accumulation of tZ-type CKs is critical for the response.

We also analysed the growth response of soil-grown plants. The mutants were germinated and grown on soil together with Col-0 under low or high CO2, and shoot growth was analysed at 17 and 31 days after germination (DAG) by measuring dry weight (DW). Note that it was not possible to evaluate root growth in this system. Although Col-0 plants grown in high CO2 had significantly higher shoot biomass compared with those grown in low CO2 at the beginning of analysis (17 DAG), they gained more biomass by further growth in high CO2 (31 DAG, Supplementary Fig. S6). RGRs between 17 and 31 DAG were significantly higher in high CO2-grown Col-0 plants than in the mutants (Fig. 7e). The number of rosette leaves counted on 31 DAG also significantly increased (Fig. 7f). Although the cypDM mutant gained more biomass under high CO2 (Supplementary Fig. S6), no significant change in RGR in response to high CO2 treatment was observed (Fig. 7e). The RGR of the ipt357 mutant was slightly enhanced by high CO2 treatment (Fig. 7e). Rosette leaf numbers did not change in the cypDM mutant and were only marginally increased in the ipt357 mutant (5.4 more leaves in the wild type compared with 1.9 in ipt357) in response to high CO2 (Fig. 7f). These results show that the ipt357 and cypDM mutants are impaired in the acceleration of shoot growth and development under elevated CO2 during the growth period examined and that the cypDM mutant, which cannot accumulate tZ-type CKs, is severely compromised.

Together, these growth analyses suggest that CK accumulation, especially of the tZ-type, through de novo biosynthesis contributes to robust growth enhancement under elevated CO2.

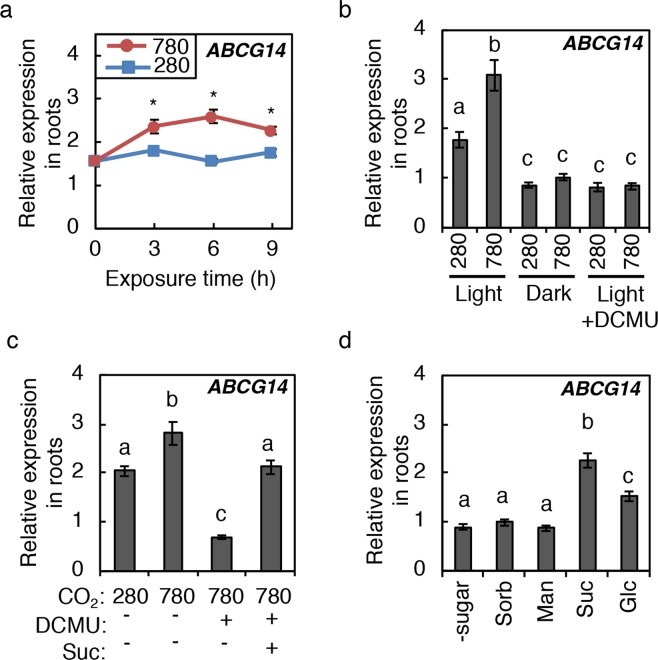

Photosynthetically generated sugars induce ABCG14 in roots

It has been reported that tZ-type CKs are translocated from root to shoot by the ABCG14 protein to act as shoot growth signals17,20,21,58. To get insight into whether root-to-shoot translocation of CKs is relevant to the observed CK accumulation in shoots, ABCG14 expression in roots was investigated (Fig. 8). Interestingly, ABCG14 expression responded to high CO2 and sugars in a similar manner to that of AtIPT3 and CYP735A2 (Fig. 8). Since ABCG14 has been reported to be CK-inducible21, we tested whether the CKs that accumulate in response to elevated CO2 and sugars are relevant to ABCG14 induction. The ipt357 and the cytokinin receptor mutants ahk2 ahk3 and ahk3 ahk451–53 were analysed as in Fig. 5a,b. ABCG14 induction in response to elevated CO2 and sugars was maintained in these mutants (Fig. 5c,d), indicating that sugars induce this gene independent of CK. Together, these results suggest that root-to-shoot translocation of CKs via ABCG14 might be involved in robust growth enhancement under elevated CO2 by mediating tZ-type CK accumulation in the shoot.

Figure 8.

Effects of high CO2, photosynthesis and sugars on the expression of ABCG14 in roots. (a) Expression levels of ABCG14 in roots of Col-0 seedlings exposed to 280 ppmv (280) or 780 ppmv (780) CO2 for the indicated periods. Treatment was conducted as in Fig. 3. (b) Effects of dark and DCMU on ABCG14 in Col-0 roots. Treatments were conducted as in Fig. 4. (c,d) Effects of sugars on ABCG14 in Col-0 roots. Treatments were conducted as in Fig. 4. Expression levels were analysed by quantitative RT-PCR and normalized using At4g34270 as an internal control. Error bars represent standard deviations of four biological replicates. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences (*p < 0.05; Student’s t-test). Different lower-case letters indicate statistically significant differences as indicated by Tukey’s HSD test (p < 0.05).

Discussion

The availability of macronutrients such as nitrogen7,43,48,59,60, phosphate9,61–63 and sulphate9,64 affects IPT expression as well as CK levels. Therefore, macronutrient availability has been proposed to regulate CK levels through de novo biosynthesis to control plant growth and development9,27,65. Our investigation has revealed another pathway in which photosynthesis-derived sugars regulate de novo CK biosynthesis to control plant growth and development.

Our study suggests that de novo CK biosynthesis is triggered by photosynthetically generated sugars (Figs 1–6). There are several other reports indicating that sugars induce the expression of genes involved in the de novo synthesis of CKs. Transcriptome analyses show that glucose66 and sucrose67,68 treatments up-regulate AtIPT3 and CYP735A2. However, how sugars are perceived (as signalling molecules, energy sources or building blocks) to induce the expression of these genes is still not understood. Thus, it is possible that sugars act indirectly through the signalling pathways of macronutrients because the metabolism of carbon and macronutrients are tightly intertwined. Although our data suggests that sugars induce CK precursor accumulation independent of nitrate-related pathways (Fig. 6), Kamada-Nobusada et al.7 reported a pathway in which the internal nitrogen status regulates CK biosynthesis. Since the internal nitrogen status can also be modulated by carbon availability, we cannot rule out the possibility that sugars affect CK biosynthesis through this pathway. Further studies on sugar and internal nitrogen sensing and signalling mechanisms are required to resolve this problem. In any case, we propose that sugars generated by photosynthesis in shoots directly or indirectly promotes de novo CK biosynthesis.

Under our experimental conditions, AtIPT3 was the only gene of the AtIPT family induced by elevated CO2 and sugars (Figs 3, 4). AtIPT3 expression is also regulated by various environmental signals to control CK levels; increases in nitrogen, phosphate, and sulphate availability induce AtIPT3 expression9,43,48,63, whereas drought and salt stress repress AtIPT3 expression69. Although it remains unclear – with the exception of nitrate – whether these signals regulate AtIPT3 expression directly70,71, the available evidence suggests that AtIPT3 functions to integrate and translate various signals in the root into de novo CK biosynthetic activity. We also found that CYP735A2 and ABCG14 are high CO2- and sugar-inducible (Figs 3, 4, 5, 8). Although CYP735A2 and ABCG14 are known to be CK-inducible genes18,21, we showed that sugars induce these genes independent of CK (Fig. 5). These results indicate that CYP735A2 and ABCG14 are controlled by two independent signals: shoot-derived signals (sugars) and root internal cues (root-synthesized CKs) in the response to elevated CO2. Thus, CYP735A2 and ABCG14 might act to integrate signals from shoots and roots and translate these signals into tZ-type CKs translocated from root to shoot. However, it remains to be determined whether ABCG14-mediated root-to-shoot translocation activity is regulated at the level of expression or by some other means.

In our expression analysis, AtIPT3 and CYP735A2 were the only genes induced under elevated CO2 among the de novo CK biosynthetic genes (Fig. 3). However, the ipt3 cyp735a2 double mutant still accumulated CKs, although at a lower level than WT (Supplementary Fig. S4d,e). The ipt357 and cypDM mutants were unable to accumulate iP-type and tZ-type CKs, respectively, in response to high CO2, suggesting that not only AtIPT3 and CYP735A2 but also AtIPT5, AtIPT7, and CYP735A1 are involved in the accumulation. Since these genes were not found to be regulated at the level of transcript accumulation, post-transcriptional regulation might be involved. Consistently, it has been reported that AtIPT3 farnesylation modulates this protein’s subcellular localization and enzymatic properties72. It should be noted that we cannot exclude that other genes involved in CK biosynthesis, modification, and/or degradation, and/or post-transcriptional regulation might be relevant to the accumulation of CKs.

In this study, the role of CKs in growth enhancement under elevated CO2 was evaluated by analysing the growth of ipt357, a mutant deficient in iP- and tZ-type CKs, and cypDM, a mutant deficient in tZ-type CKs. Both mutants displayed similar growth response defects (Fig. 7), indicating that tZ-type CKs are required for robust growth enhancement of shoots and roots under elevated CO2. A reduction in shoot growth acceleration in these mutants is consistent with previous reports that tZ-type CKs and their root-to-shoot translocation act to promote shoot growth17,20,21. However, a reduction in root growth acceleration cannot be explained by CK action because CKs generally act to repress root growth73,74. This result suggests that CK is not the major determinant of root growth rate. It is plausible that slowed root growth is a consequence of reduced photosynthesis (as sources of energy and building blocks) by smaller shoots, but it is also possible that complex crosstalk might exist between CK and sugars.

Here, we revealed that sugar-induced de novo biosynthesis of CKs plays a role in the robust growth enhancement under elevated CO2. This finding provides some insight into the mechanisms that plants employ to optimise growth in a fluctuating environment. Taking into account that AtIPT3, CYP735A2, and ABCG14 are induced in the root by photosynthetically generated sugars (Figs 3, 4, 5, 8), it is tempting to speculate that there is a systemic growth regulatory mechanism in which photosynthetically generated sugars induce de novo tZ-type CK biosynthesis in the root and root-to-shoot translocation of the CK via ABCG14 for growth regulation of the shoot.

Materials and Methods

Plant material and growth conditions

Arabidopsis thaliana ecotype Columbia (Col-0) was used as the wild type. The cytokinin biosynthetic triple mutants ipt3 ipt5 ipt757, the cytokinin receptor double mutants ahk2 ahk3 and ahk3 ank453, and the cyp735a1-2 cyp735a2-2 double mutant17 were characterized previously. The ipt3 cyp735a2-1 and ipt3 cyp735a2-2 double mutants were generated by crosses between the ipt3 ipt5 ipt7 and the cyp735a1-2 cyp735a2-1 mutant, and cyp735a1-2 cyp735a2-2 mutants. For studies on soil-grown plants, stratified seeds were sown directly on nutrient-rich soil (Supermix A, Sakata, Japan), and grown in a CO2-controlled growth chamber (LPH-0.5P-SH; Nippon Medical & Chemical Instrument) at 280 ppmv or 780 ppmv CO2 under 150 µmol m−2 s−1 fluorescent light (12 h light/12 h dark) at 22 °C. For studies on seedlings, plants were grown on half-strength MS (1/2 MS) agar plates (pH 5.8; 1% agar) placed vertically at 22 °C in the CO2-controlled growth chamber at 280 ppmv or 780 ppmv CO2 under continuous light (120 µmol m−2 s−1) unless otherwise noted. To avoid any chamber effects, we used two growth chambers simultaneously with different CO2 concentrations and repeated each experiment at least twice with different chamber and CO2 concentration combinations. Although the data presented are from one representative experiment, similar results were obtained from different chamber and CO2 concentration combinations.

Quantification of plant hormones

Cytokinin level was determined using an ultra-performance liquid chromatograph coupled with a tandem quadrupole mass spectrometer equipped with an electrospray interface as described previously75. IAA and ABA levels were determined using an ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC)-electrospray interface (ESI) and a quadrupole-orbitrap mass spectrometer (UHPLC/Q-Exactive; Thermo Scientific) as described previously76. In the results reported, the category iP-type CK precursors comprise iPR and iPRPs; inactivated iP-type CK comprise iP7G and iP9G; tZ-type CK precursors comprise tZR and tZRPs; and inactivated tZ-type CK comprise tZ7G, tZ9G, tZOG, tZROG, and tZRPsOG.

Gene expression analysis

Total RNA was extracted from root and shoot samples using the RNeasy Plant Mini kit (QIAGEN) in combination with the RNase-Free DNase set (QIAGEN). Total RNA was used for first strand cDNA synthesis by the SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System (Life Technologies) with oligo(dT)20 primers. Quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) was performed on a StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) with the KAPA SYBR Fast qPCR kit (KAPA Biosystems). At4g34270 was used as an internal control because this gene has been shown to be one of the most stably expressed genes in Arabidopsis77,78. Similar results were obtained using other internal control genes (At1g13320 and At2g28390) as described by Czechowski et al.78. Primer sets are listed in Supplementary Table S9.

DCMU and sugar treatment

For 3-(3,4-dichlorophenyl)-1,1-dimethylurea (DCMU) treatment, 8-day-old Col-0 seedlings grown on 1/2 MS agar plates (1% agar) placed vertically under continuous fluorescent light (120 µmol m−2 s−1) at 22 °C in a CO2-controlled growth chamber at 280 ppmv CO2 were sprayed with 40 µM DCMU or mock solution (0.05% ethanol) and exposed to 280 ppmv or 780 ppmv CO2 under 120 µmol m−2 s−1 light or in the dark. The DCMU stock solution was 40 mM in 50% ethanol. For DCMU and sucrose co-treatment, seedlings were treated with 40 µM DCMU or mock solution (0.05% ethanol) and then transferred to 1/2 MS agar plates (1% agar) containing 90 mM sucrose. For sugar treatment, seedlings were transferred to 1/2 MS agar plates (1% agar) containing 90 mM of sorbitol, mannitol, sucrose, glucose, or 45 mM sucrose.

High CO2 and sugar treatment under different nitrogen conditions

Wild-type seedlings were pre-grown for 11 days on modified 1/2 MS agar plates (1% agar) containing 10 mM KNO3, 10 mM NH4Cl or 5 mM NH4NO3 as the sole nitrogen source in the CO2-controlled growth chamber at 280 ppmv. Seedlings grown with 10 mM KNO3, 10 mM NH4Cl or 5 mM NH4NO3 were then transferred to new 1/2 MS agar plates (1% agar) containing 10 mM KNO3, 10 mM NH4Cl or no nitrogen source, respectively. After 24 h incubation at 280 ppmv, seedlings were subjected to high CO2 and sugar treatments under the same nitrogen conditions.

Growth analysis under low or high CO2

For growth analysis of soil-grown plants, stratified seeds were sown directly on nutrient-rich soil (Supermix A, Sakata, Japan), and grown in a CO2-controlled growth chamber at 280 ppmv or 780 ppmv CO2 under 150 µmol m−2 s−1 fluorescent light (12 h light/12 h dark) at 22 °C and 60% relative humidity. Shoots were harvested at 17 and 31 days after germination (DAG) and their dry weights were determined after drying them in an oven set at 80 °C for three days. Rosette leaf number was counted on 31 DAG.

For seedling growth analysis, surface sterilized seeds were sown on 1/2 MS agar plates (1% agar) containing 1% sucrose. After stratification, plates were placed vertically in a CO2-controlled growth chamber (120 µmol m−2 s−1 continuous fluorescent light, 22 °C) at 280 ppmv. Five-day-old seedlings were transferred to 1/2 MS agar plates (1% agar without sucrose) and grown vertically for another 7 days at 280 ppmv. Then, the 12-day-old seedlings were exposed to 280 ppmv or 780 ppmv CO2 for seven days. The shoots and roots were separated and their fresh weights were measured before (Supplementary Figs S4a; S5) and after exposure (Fig. 7c). Relative growth rate (RGR) was calculated from the dry and fresh weights as described elsewhere79.

To avoid any chamber effects, we used two growth chambers simultaneously with different CO2 concentrations and repeated each experiment at least twice with different chamber and CO2 concentration combinations. Although the data presented are from one representative experiment, similar results were obtained from different chamber and CO2 concentration combinations.

Statistical analysis

Data are given as means ± standard error (SE) or means ± standard deviation (SD) of one representative experiment. In order to examine whether hormone concentration, gene expression, or shoot growth were significantly different between treatments, Student’s t-test, two-way ANOVA, and Tukey’s honest significant difference (HSD) test were performed using KaleidaGraph ver. 4.1 software (Synergy Software).

Accession numbers

Sequence data for the genes described in this article can be found in The Arabidopsis Information Resource database (see http://www.arabidopsis.org) under the following accession numbers: CYP735A1 (At5g38450), CYP735A2 (At1g67110), AtIPT1 (At1g68460), AtIPT3 (At3g63110), AtIPT4 (At4g24650) AtIPT5 (At5g19040), AtIPT6 (Ay1g25410), AtIPT7 (At3g23630), AtIPT8 (At3g19160), CKX1 (At2g41510), AtCKX2 (At2g19500), CKX3 (At5g56970), CKX4 (At4g29740), CKX5 (At1g75450), CKX6 (At3g63440), CKX7 (At5g21482), ARR4 (At1g10470), ARR6 (At5g62920), ARR15 (At1g74890), ABCG14 (At1g31770).

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Prof. Tatsuo Kakimoto (Osaka Univ.) for providing the ipt3 ipt5 ipt7, ahk2 ahk3, and ahk3 ahk4 mutants. We thank Dr. Ko Noguchi (Tokyo Univ.) for advice concerning statistical analysis. Hormone analyses were supported by the Japan Advanced Plant Science Network. This work was, in part, supported by the Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas (No. 21114005, JP16H01477, JP17H06473, JP18H04793) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science & Technology of Japan.

Author Contributions

T.K. and H.S. conceived the research. T.K., Y.T. and M.K. conducted the experiments. T.K., Y.T. and M.K. and H.S. analysed and discussed the data. T.K. and H.S. wrote the manuscript.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Takatoshi Kiba, Email: kiba@agr.nagoya-u.ac.jp.

Hitoshi Sakakibara, Email: sakaki@agr.nagoya-u.ac.jp.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-44185-4.

References

- 1.Mason MG, Ross JJ, Babst BA, Wienclaw BN, Beveridge CA. Sugar demand, not auxin, is the initial regulator of apical dominance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:6092–6097. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1322045111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kiba T, Kudo T, Kojima M, Sakakibara H. Hormonal control of nitrogen acquisition: roles of auxin, abscisic acid, and cytokinin. J. Exp. Bot. 2011;62:1399–1409. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oka-Kira E, Kawaguchi M. Long-distance signaling to control root nodule number. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2006;9:496–502. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2006.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kircher S, Schopfer P. Photosynthetic sucrose acts as cotyledon-derived long-distance signal to control root growth during early seedling development in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:11217–11221. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203746109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Osugi A, Sakakibara H. Q&A: How do plants respond to cytokinins and what is their importance? BMC Biol. 2015;13:102. doi: 10.1186/s12915-015-0214-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ljung K, Nemhauser JL, Perata P. New mechanistic links between sugar and hormone signalling networks. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2015;25:130–137. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2015.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kamada-Nobusada T, Makita N, Kojima M, Sakakibara H. Nitrogen-dependent regulation of de novo cytokinin biosynthesis in rice: The role of glutamine metabolism as an additional signal. Plant Cell Physiol. 2013;54:1881–1893. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pct127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kudo T, Kiba T, Sakakibara H. Metabolism and long-distance translocation of cytokinins. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2010;52:53–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2010.00898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirose N, et al. Regulation of cytokinin biosynthesis, compartmentalization and translocation. J. Exp. Bot. 2008;59:75–83. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sakakibara H. Cytokinins: activity, biosynthesis, and translocation. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2006;57:431–449. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mok DW, Mok MC. Cytokinin metabolism and action. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 2001;52:89–118. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.52.1.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shaw, G. Chemistry of adenine cytokinins in Cytokinins:Chemistry, Activity, and Function (eds Mok, D. W. S. & Mok, M. C.) 15–34 (CRC Press, 1994).

- 13.Takei K, Sakakibara H, Sugiyama T. Identification of genes encoding adenylate isopentenyltransferase, a cytokinin biosynthesis enzyme, in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:26405–26410. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102130200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kakimoto T. Identification of plant cytokinin biosynthetic enzymes as dimethylallyl diphosphate: ATP/ADP isopentenyltransferases. Plant Cell Physiol. 2001;42:677–685. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pce112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmülling T, Werner T, Riefler M, Krupková E, Manns IBY. Structure and function of cytokinin oxidase/dehydrogenase genes of maize, rice, Arabidopsis and other species. J. Plant Res. 2003;116:241–252. doi: 10.1007/s10265-003-0096-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nishiyama R, et al. Analysis of cytokinin mutants and regulation of cytokinin metabolic genes reveals important regulatory roles of cytokinins in drought, salt and abscisic acid responses, and abscisic acid biosynthesis. Plant Cell. 2011;23:2169–2183. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.087395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kiba T, Takei K, Kojima M, Sakakibara H. Side-Chain Modification of Cytokinins Controls Shoot Growth in Arabidopsis. Dev. Cell. 2013;27:452–461. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takei K, Yamaya T, Sakakibara H. Arabidopsis CYP735A1 and CYP735A2 encode cytokinin hydroxylases that catalyze the biosynthesis of trans-zeatin. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:41866–41872. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406337200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bishopp A, et al. Phloem-transported cytokinin regulates polar auxin transport and maintains vascular pattern in the root meristem. Curr. Biol. 2011;21:927–932. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.04.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang K, et al. Arabidopsis ABCG14 protein controls the acropetal translocation of root-synthesized cytokinins. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:3274. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ko D, et al. Arabidopsis ABCG14 is essential for the root-to-shoot translocation of cytokinin. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:7150–7155. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1321519111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tanaka M, Takei K, Kojima M, Sakakibara H, Mori H. Auxin controls local cytokinin biosynthesis in the nodal stem in apical dominance. Plant J. 2006;45:1028–1036. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02656.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yanai O, et al. Arabidopsis KNOXI proteins activate cytokinin biosynthesis. Curr. Biol. 2005;15:1566–1571. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.07.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jasinski S, et al. KNOX action in Arabidopsis is mediated by coordinate regulation of cytokinin and gibberellin activities. Curr. Biol. 2005;15:1560–1565. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yong JW, Wong SC, Letham DS, Hocart CH, Farquhar GD. Effects of elevated [CO2] and nitrogen nutrition on cytokinins in the xylem sap and leaves of cotton. Plant Physiol. 2000;124:767–780. doi: 10.1104/pp.124.2.767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Teng N, et al. Elevated CO2 induces physiological, biochemical and structural changes in leaves of Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 2006;172:92–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sakakibara H. Nitrate-specific and cytokinin-mediated nitrogen signaling pathways in plants. J. Plant Res. 2003;116:253–257. doi: 10.1007/s10265-003-0097-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ha S, Vankova R, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Shinozaki K, Tran LS. Cytokinins: metabolism and function in plant adaptation to environmental stresses. Trends Plant Sci. 2012;17:172–179. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsutsumi K, Konno M, Miyazawa SI, Miyao M. Sites of Action of Elevated CO2 on leaf development in rice: discrimination between the effects of elevated CO2 and nitrogen deficiency. Plant Cell Physiol. 2014;55:258–268. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcu006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Terashima I, Yanagisawa S, Sakakibara H. Plant responses to CO2: background and perspectives. Plant Cell Physiol. 2014;55:237–240. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcu022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sato S, Yanagisawa S. Characterization of metabolic states of Arabidopsis thaliana under diverse carbon and nitrogen nutrient conditions via targeted metabolomic analysis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2014;55:306–319. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pct192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duan Z, et al. Photoassimilation, assimilate translocation and plasmodesmal biogenesis in the source leaves of Arabidopsis thaliana grown under an increased atmospheric CO2 concentration. Plant Cell Physiol. 2014;55:358–369. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcu004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ruan YL. Sucrose metabolism: gateway to Ddiverse carbon use and sugar signaling. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2014;65:33–67. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-050213-040251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taylor, G. et al. Spatial and temporal effects of free-air CO2 enrichment (POPFACE) on leaf growth, cell expansion, and cell production in a closed canopy of poplar. Plant Physiol. 131, 177–185 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Luomala EM, Laitinen K, Sutinen S, Kellomaki S, Vapaavuori E. Stomatal density, anatomy and nutrient concentrations of Scots pine needles are affected by elevated CO2 and temperature. Plant Cell Environ. 2005;28:733–749. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2005.01319.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Takatani N, et al. Effects of high CO2 on growth and metabolism of Arabidopsis seedlings during growth with a constantly limited supply of nitrogen. Plant Cell Physiol. 2014;55:281–292. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pct186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hachiya T, et al. High CO2 triggers preferential root growth of Arabidopsis thaliana via two distinct systems under low pH and low N stresses. Plant Cell Physiol. 2014;55:269–280. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcu001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li CR, Gan LJ, Xia K, Zhou X, Hew CS. Responses of carboxylating enzymes, sucrose metabolizing enzymes and plant hormones in a tropical epiphytic CAM orchid to CO2 enrichment. Plant Cell Environ. 2002;25:369–377. doi: 10.1046/j.0016-8025.2001.00818.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schaz U, Dull B, Reinbothe C, Beck E. Influence of root-bed size on the response of tobacco to elevated CO2 as mediated by cytokinins. Aob Plants. 2014;6:plu010. doi: 10.1093/aobpla/plu010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.IPCC, 2014. Climate change 2014: Synthesis report. Contribution of working groups I, II and III to the fifth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change [eds Core Writing Team, Pachauri, R. K. & Meyer, L. A.] (IPCC, 2014)

- 41.Song X, Kristie DN, Reekie EG. Why does elevated CO2 affect time of flowering? An exploratory study using the photoperiodic flowering mutants of Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 2009;181:339–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aoyama S, et al. Ubiquitin ligase ATL31 functions in leaf senescence in response to the balance between atmospheric CO2 and nitrogen availability in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2014;55:293–305. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcu002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Takei K, et al. AtIPT3 is a key determinant of nitrate-dependent cytokinin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2004;45:1053–1062. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pch119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lomin SN, et al. Plant membrane assays with cytokinin receptors underpin the unique role of free cytokinin bases as biologically active ligands. J. Exp. Bot. 2015;66:1851–1863. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eru522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hothorn M, Dabi T, Chory J. Structural basis for cytokinin recognition by Arabidopsis thaliana histidine kinase 4. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2011;7:766–768. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tokunaga H, et al. Arabidopsis lonely guy (LOG) multiple mutants reveal a central role of the LOG-dependent pathway in cytokinin activation. Plant J. 2012;69:355–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ashikari M, et al. Cytokinin oxidase regulates rice grain production. Science. 2005;309:741–745. doi: 10.1126/science.1113373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miyawaki K, Matsumoto-Kitano M, Kakimoto T. Expression of cytokinin biosynthetic isopentenyltransferase genes in Arabidopsis: tissue specificity and regulation by auxin, cytokinin, and nitrate. Plant J. 2004;37:128–138. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Haydon MJ, Mielczarek O, Robertson FC, Hubbard KE, Webb AA. Photosynthetic entrainment of the Arabidopsis thaliana circadian clock. Nature. 2013;502:689–692. doi: 10.1038/nature12603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kilian J, et al. The AtGenExpress global stress expression data set: protocols, evaluation and model data analysis of UV-B light, drought and cold stress responses. Plant J. 2007;50:347–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Riefler M, Novak O, Strnad M, Schmülling T. Arabidopsis cytokinin receptor mutants reveal functions in shoot growth, leaf senescence, seed size, germination, root development, and cytokinin metabolism. Plant Cell. 2006;18:40–54. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.037796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nishimura C, et al. Histidine kinase homologs that act as cytokinin receptors possess overlapping functions in the regulation of shoot and root growth in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2004;16:1365–1377. doi: 10.1105/tpc.021477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Higuchi M, et al. In planta functions of the Arabidopsis cytokinin receptor family. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:8821–8826. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402887101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Maeda Y, et al. A NIGT1-centred transcriptional cascade regulates nitrate signalling and incorporates phosphorus starvation signals in Arabidopsis. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:1376. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03832-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lejay L, et al. Oxidative pentose phosphate pathway-dependent sugar sensing as a mechanism for regulation of root ion transporters by photosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 2008;146:2036–2053. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.114710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lejay L, et al. Regulation of root ion transporters by photosynthesis: Functional importance and relation with hexokinase. Plant Cell. 2003;15:2218–2232. doi: 10.1105/tpc.013516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Miyawaki K, et al. Roles of Arabidopsis ATP/ADP isopentenyltransferases and tRNA isopentenyltransferases in cytokinin biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:16598–16603. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603522103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Osugi A, et al. Systemic transport of trans-zeatin and its precursor have differing roles in Arabidopsis shoots. Nat. Plants. 2017;3:17112. doi: 10.1038/nplants.2017.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Takei K, Sakakibara H, Taniguchi M, Sugiyama T. Nitrogen-dependent accumulation of cytokinins in root and the translocation to leaf: Implication of cytokinin species that induces gene expression of maize response regulator. Plant Cell Physiol. 2001;42:85–93. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pce009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Walch-Liu P, Neumann G, Bangerth F, Engels C. Rapid effects of nitrogen form on leaf morphogenesis in tobacco. J. Exp. Bot. 2000;51:227–237. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/51.343.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Horgan JM, Wareing PF. Cytokinins and the growth responses of seedlings of Betula pendula Roth. and Acer pseudoplatanus L. to nitrogen and phosphorus deficiency. J. Exp. Bot. 1980;31:525–532. doi: 10.1093/jxb/31.2.525. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Salama AMSEA, Wareing PF. Effects of mineral nutrition on dndogenous cytokinins in plants of sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) J. Exp. Bot. 1979;30:971–981. doi: 10.1093/jxb/30.5.971. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Woo J, et al. The response and recovery of the Arabidopsis thaliana transcriptome to phosphate starvation. BMC Plant Biol. 2012;12:62. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-12-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ohkama N, et al. Regulation of sulfur-responsive gene expression by exogenously applied cytokinins in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2002;43:1493–1501. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcf183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lopez-Bucio J, Cruz-Ramirez A, Herrera-Estrella L. The role of nutrient availability in regulating root architecture. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2003;6:280–287. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5266(03)00035-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kushwah S, Laxmi A. The interaction between glucose and cytokinin signal transduction pathway in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Environ. 2014;37:235–253. doi: 10.1111/pce.12149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stokes ME, Chattopadhyay A, Wilkins O, Nambara E, Campbell MM. Interplay between sucrose and folate modulates auxin signaling in. Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2013;162:1552–1565. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.215095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gutierrez RA, et al. Qualitative network models and genome-wide expression data define carbon/nitrogen-responsive molecular machines in Arabidopsis. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R7. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-1-r7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nishiyama R, et al. Transcriptome analyses of a salt-tolerant cytokinin-deficient mutant reveal differential regulation of salt stress response by cytokinin deficiency. PLoS One. 2012;7:e32124. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wang R, Xing X, Wang Y, Tran A, Crawford NM. A genetic screen for nitrate regulatory mutants captures the nitrate transporter gene NRT1.1. Plant Physiol. 2009;151:472–478. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.140434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ho CH, Lin SH, Hu HC, Tsay YF. CHL1 functions as a nitrate sensor in plants. Cell. 2009;138:1184–1194. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Galichet A, Hoyerova K, Kaminek M, Gruissem W. Farnesylation directs AtIPT3 subcellular localization and modulates cytokinin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2008;146:1155–1164. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.107425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kuderova A, et al. Effects of conditional IPT-Dependent cytokinin overproduction on root architecture of Arabidopsis seedlings. Plant Cell Physiol. 2008;49:570–582. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcn029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kiba T, et al. The type-A response regulator, ARR15, acts as a negative regulator in the cytokinin-mediated signal transduction in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2003;44:868–874. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcg108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kojima M, et al. Highly sensitive and high-throughput analysis of plant hormones using MS-probe modification and liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry: an application for Hhmone profiling in Oryza sativa. Plant Cell Physiol. 2009;50:1201–1214. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcp057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shinozaki, Y. et al. Ethylene suppresses tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) fruit set through modification of gibberellin metabolism. Plant J. 83, 237–251 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 77.Dekkers BJ, et al. Identification of reference genes for RT-qPCR expression analysis in Arabidopsis and tomato seeds. Plant Cell Physiol. 2012;53:28–37. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcr113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Czechowski T, Stitt M, Altmann T, Udvardi MK, Scheible WR. Genome-wide identification and testing of superior reference genes for transcript normalization in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2005;139:5–17. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.063743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hoffmann WA, Poorter H. Avoiding bias in calculations of relative growth rate. Ann. Bot. 2002;90:37–42. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcf140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.