Abstract

Impaired insulin secretion from pancreatic islets is a hallmark of type 2 diabetes (T2D). Altered chromatin structure may contribute to the disease. We therefore studied the impact of T2D on open chromatin in human pancreatic islets. We used assay for transposase-accessible chromatin using sequencing (ATAC-seq) to profile open chromatin in islets from T2D and non-diabetic donors. We identified 57,105 and 53,284 ATAC-seq peaks representing open chromatin regions in islets of non-diabetic and diabetic donors, respectively. The majority of ATAC-seq peaks mapped near transcription start sites. Additionally, peaks were enriched in enhancer regions and in regions where islet-specific transcription factors (TFs), e.g. FOXA2, MAFB, NKX2.2, NKX6.1 and PDX1, bind. Islet ATAC-seq peaks overlap with 13 SNPs associated with T2D (e.g. rs7903146, rs2237897, rs757209, rs11708067 and rs878521 near TCF7L2, KCNQ1, HNF1B, ADCY5 and GCK, respectively) and with additional 67 SNPs in LD with known T2D SNPs (e.g. SNPs annotated to GIPR, KCNJ11, GLIS3, IGF2BP2, FTO and PPARG). There was enrichment of open chromatin regions near highly expressed genes in human islets. Moreover, 1,078 open chromatin peaks, annotated to 898 genes, differed in prevalence between diabetic and non-diabetic islet donors. Some of these peaks are annotated to candidate genes for T2D and islet dysfunction (e.g. HHEX, HMGA2, GLIS3, MTNR1B and PARK2) and some overlap with SNPs associated with T2D (e.g. rs3821943 near WFS1 and rs508419 near ANK1). Enhancer regions and motifs specific to key TFs including BACH2, FOXO1, FOXA2, NEUROD1, MAFA and PDX1 were enriched in differential islet ATAC-seq peaks of T2D versus non-diabetic donors. Our study provides new understanding into how T2D alters the chromatin landscape, and thereby accessibility for TFs and gene expression, in human pancreatic islets.

Subject terms: Type 2 diabetes, Genetics research

Introduction

Genetic, epigenetic and environmental factors contribute to development of type 2 diabetes (T2D)1,2. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) support islet dysfunction to be a key defect in T2D3. A large proportion of T2D-associated SNPs are located at regulatory regions and enhancer elements which control gene transcription4. Both the transcriptome and methylome are altered in T2D islets5–7. However, additional studies are needed to fully dissect the molecular mechanisms contributing to islet dysfunction. Importantly, a map of the open chromatin has not been generated in pancreatic islets of numerous subjects with T2D.

Transcription factors (TFs) bind to DNA in a sequence-specific manner by removing or moving the nucleosomes to form open chromatin8. These open chromatin or nucleosome free regions are sensitive to nuclease enzymes. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)-seq and DNase-seq studies from ENCODE show that open chromatin regions include all classes of cis-regulatory elements (cis-REs) e.g. promoters, enhancers and insulators9,10. Studies performed in human islet cells revealed that T2D-associated loci reside at open chromatin regions and enhancers11–15. However, these studies were mainly performed in islets/cells of non-diabetic donors and knowledge of how T2D alters the open chromatin structure in islets is needed.

To map the open chromatin landscape in relation to T2D, we performed assay for transposase-accessible chromatin using sequencing (ATAC-seq) in human pancreatic islets from T2D and non-diabetic donors. ATAC-seq is a sensitive recently developed method with ability to map open chromatin in a small number of cells16. We further integrated our human islet ATAC-seq data with RNA-seq and published islet ChIP-seq data of histone modifications and TFs.

Methods

Islets

Human islets of 9 non-diabetic donors and 6 donors diagnosed with T2D were obtained from the Nordic Network of Islet Transplantation, Uppsala University, Sweden. Donor characteristics are presented in Table 1. Donor or his/her relatives had given their written consent to donate organs for biomedical research upon admission into the intensive care unit. The work was approved by ethics committees at Uppsala and Lund Universities. Islets were isolated and cultured as described6. All islet preparations used in this study had a purity above 80%. Fresh islets were picked with pipette under stereo microscope and snap frozen in aliquots (~30 islets) (n = 5 donors) or immediately used for ATAC-seq (n = 5 donors). Frozen islets were obtained from our biobank and were thawed on ice (n = 5 donors). This information is presented in Supplemental Table 1 and there are T2D donors in all three categories. 1 μl of islet pellet (corresponding to ~30 islets) was used for each ATAC-seq experiment.

Table 1.

Characteristics for donors of pancreatic islets included in the ATAC-seq analysis.

| Non-diabetic donors (n = 9) | T2D donors (n = 6) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (M/F) | 6/3 | 2/4 | |

| Age (years) | 61.4 ± 14.5 | 61.8 ± 7.0 | 0.58 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.4 ± 3.3 | 30.3 ± 2.3 | 0.049 |

| HbA1c (mmol/mol) | 35.3 ± 3.6* | 49.2 ± 8.8** | 0.002 |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.37 ± 0.3* | 6.66 ± 0.8** | 0.002 |

Data presented as mean +/− SD. Data analyzed by Mann-Whitney U-test *Data available for seven donors. **Data available for five donors.

ATAC-seq

ATAC-seq was performed as previously described16 in our human islets (see Supplemental material and methods).

Analysis of ATAC-seq data

See Supplemental material and methods.

Annotation of ATAC-seq peaks

The ATAC-seq peaks were annotated to genomic elements such as transcription start sites (TSS), transcription termination sites (TTS), exons and introns using GENCODE version19 for GRCh37. Each peak was annotated in relation to all these elements and may thereby have multiple gene annotations.

Islet RNA-seq

See Supplemental material and methods.

TF motif analyses of ATAC-seq peaks

We performed two different TF analyses of the ATAC-seq data; (i) looking at overlap between islet ATAC-seq data and binding of specific TFs in human islets using ChIP-seq data generated by Pasquali et al.11 and (ii) looking at overlap between islet ATAC-seq data and putative TF binding motifs. TF binding motif analysis of ATAC-seq data was performed using HOMER v4.7.217. Only known motifs from HOMER’s motif database were considered. We studied motifs enriched in ATAC-seq peaks of non-diabetic donors, and motifs enriched in T2D peaks relative non-diabetics. The latter analysis was performed by findMotifsGenome.pl with the peak set for non-diabetics as background.

Overlapping ATAC-seq peaks with public ChIP-seq datasets

See Supplemental material and methods.

Lift-over of published datasets

UCSC lift-over online tool (https://genome.ucsc.edu/cgi-bin/hgLiftOver) was used to convert the original assemblies of published datasets into GRCh37/hg19 using BED files or chromosome coordinates.

Functional experiments in beta-cell line

INS-1 832/13 rat beta-cells were used in functional experiments as described6. The siRNAs used for knockdown were s144488 (siGabra2) and s132130 (siSlc16a7) and a custom negative control siRNA (5′-GAGACCCUAUCCGUGAUUAUU-3′) (siNC). Knockdown was verified with qPCR and TaqMan assays for Gabra2 (Rn01413643_m1) and Slc16a7 (Rn00568872_m1). Assays for Hprt1 (Rn01527840_m1) and Ppia (Rn00690933_m1) were used as endogenous controls and knockdown was calculated with the geometric mean method. Insulin secretion was analyzed as previously described18, except that insulin was determined with an ELISA (Mercodia, Uppsala, Sweden). All siRNA and TaqMan assays were ordered from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA.

Statistics

Mann-Whitney U-tests were used for clinical data. Fisher’s exact tests were used to test if the number of ATAC-seq peaks were significantly associated with T2D and gene expression. Enrichments were analyzed by chi-square tests and a 5% overlap was considered by chance, i.e. 5% of the total number of peaks for each group. False discovery rate (FDR) analyses were used to correct for multiple testing.

Fisher’s exact test was used for an occupancy-based analysis (i.e. to identify islet ATAC-seq peaks that were found in significantly more non-diabetic compared to T2D donors or vice versa). The R Diffbind package and edgeR package19 were used for an affinity-based analysis (i.e. to identify islet ATAC-seq peaks where the mean number of mapped reads differ between the groups). Gender and sample treatment (frozen/non-frozen) were included as covariates in the design matrix. The whole ATAC-seq workflow was implemented in Snakemake20. qPCR and insulin secretion experiments performed in beta-cells were analyzed with the non-parametric Mann-Whitney test.

Ethics

Informed consent for organ donation for medical research was obtained from pancreatic donors or their relatives in accordance with the approval by the regional ethics committee in Lund, Sweden (Dnr 173/2007). This study was performed in agreement with the Helsinki Declaration.

Results

Mapping the open chromatin landscape in human islets

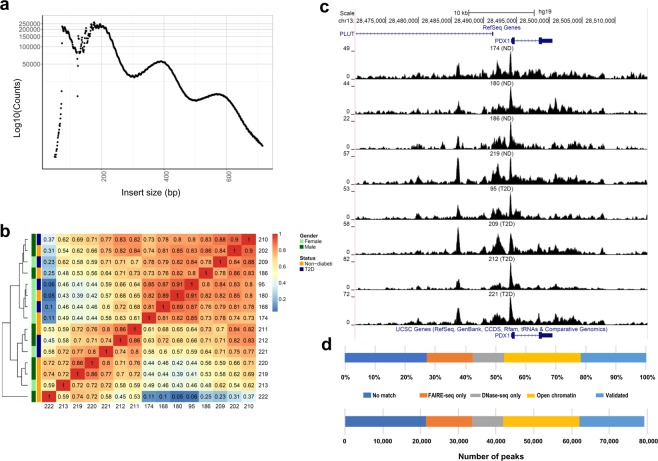

We performed ATAC-seq to map the open chromatin accessible regions in human islets of 15 donors (6 with and 9 without T2D). The characteristics of these donors are presented in Table 1. The ATAC-seq libraries were sequenced to an average of 101.3 million reads per islet sample. The quality of the ATAC-seq data was high for all islet samples with expected fragment distribution and clear nucleosome phasing (Fig. 1a and Supplemental Fig. 1a–d). Strand cross-correlation statistics analyzed by phantompeakqualtools support high quality ATAC-seq data (Supplemental Table 1). Figure 1b shows hierarchical clustering of Spearman correlations of the samples, as calculated by deepTools. Islet ATAC-seq data correlated between the donors (Fig. 1b).

Figure 1.

(a) Insert size distributions of islet ATAC-seq data showing clear nucleosome phasing. The first peak represents the open chromatin, peak 2 to 4 represent mono-, di- and tri-nucleosomal regions. (b) Hierarchical clustering of the Spearman correlation of the ATAC-seq data, as calculated by binning reads for consecutive bins of 10 kilobases including ATAC-seq data of all analyzed islet samples and excluding Y-chromosome data. (c) Representative sequencing tracks for the PDX1 locus show distinct ATAC-seq peaks at the promoter and the known enhancer in human islets. The ATAC-seq data have been normalized to take sequencing depth into account and the scale on the y-axis was chosen for optimal visualization of peaks for each sample. (d) Proportions of islet ATAC-seq peaks identified in at least three donors (79,255 open chromatin peaks) overlapping with ENCODE open chromatin data generated using FAIRE-seq and DNaseI-seq in human islets. ATAC-seq peaks overlap with the following number and categories of ENCODE peaks: 17,172 validated peaks, 20,178 open chromatin peaks, 8,288 DNaseOnly peaks and 12,063 FAIREonly peaks. 21,554 ATAC-seq peaks did not match with ENCODE peaks.

ATAC-seq peaks were only considered if they exist in at least three islet samples. Using this cut-off, 79,255 open chromatin peaks were identified when we combined ATAC-seq data from non-diabetic and diabetic islet donors (Supplemental Table 2). Using the same criteria but looking at non-diabetic and T2D donors separately, we identified 57,105 and 53,284 open chromatin regions in respective group (Supplemental Tables 3 and 4). Some sequencing ATAC-seq tracks annotated to PDX-1, a transcription factor regulating beta-cell development and insulin gene expression21, and FOXA2, a regulator of beta-cell development, are presented in Fig. 1c and Supplemental Fig. 2a,b.

We next compared our islet ATAC-seq data (79,255 open chromatin peaks) with ENCODE open chromatin data generated using FAIRE-seq and DNaseI-seq as well as with ATAC-seq data generated by Thurner et al. in human islets9,12,22. Approximately 73% of our ATAC-seq peaks overlap with ENCODE peaks (peaks identified by FAIRE-seq and DNaseI-seq in islets of non-diabetic donors, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSM1002652) further supporting the quality of our data (Fig. 1d). The overlap between our ATAC-seq peaks and ENCODE data is also presented in Supplemental Tables 2–4. Moreover, 79,193 of our ATAC-seq peaks (99.9%) overlapped with data generated by Thurner et al. (Supplemental Table 5).

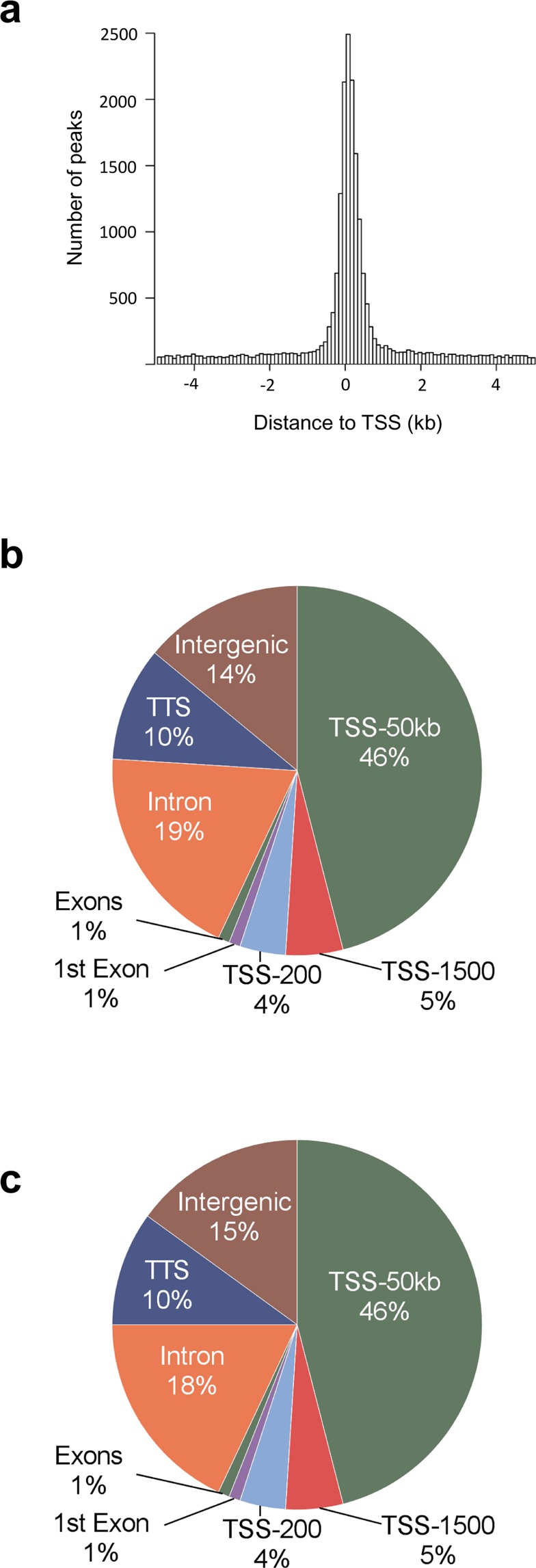

We further examined the genomic distribution of ATAC-seq open chromatin peaks. As anticipated, a large proportion of ATAC-peaks are located close to TSS (Fig. 2a). Moreover, accessible regions of chromatin show a similar genomic distribution in islets from diabetic and non-diabetic donors (Fig. 2b,c).

Figure 2.

(a) Histogram showing the distance from the nearest transcription start site (TSS) for all islet ATAC-seq peaks. (b-c) Proportions of islet ATAC-seq peaks annotated to different genomic regions in (b) non-diabetic donors and (c) donors with type 2 diabetes. Here, TSS-50 kb represents 1,501–50,000 bp upstream of the TSS, TSS-1500 represents 201–1,500 bp upstream of the TSS, TSS-200 represents 1–200 bp upstream of the TSS, and TTS represents 1–10,000 bp downstream of the transcript termination site.

We next tested if genetic variants associated with T2D as well as SNPs in linkage disequilibrium (LD) with these overlap with our islet ATAC-seq peaks (Supplemental Table 2). We used 128 SNPs associated with T2D in Scott et al.23 and 2,207 SNPs in LD with these based on r2 = 0.8–1, 1000 genomes, phase 3 and hg19 (http://raggr.usc.edu/). SNPs with a minor allele frequency less than 0.01 were excluded. We found 13 SNPs from Scott et al. and 67 LD SNPs which were located within our islet ATAC-seq peaks (Supplemental Table 6). Interestingly, these include SNPs linked to well-studied candidate genes for T2D such as rs7903146, rs2237897, rs757209, rs11708067 and rs878521 which are linked to TCF7L2, KCNQ1, HNF1B, ADCY5 and GCK, respectively. Also the 67 SNPs in LD with known T2D SNPs are linked to key diabetes genes such as GIPR, KCNJ11, GLIS3, IGF2BP2, FTO, THADA, IRS1 and PPARG.

Enrichment of histone modifications and enhancer elements at open chromatin regions in human islets

Post-translational modifications of histones can be used to classify cis-REs such as promoters and enhancers. To further classify the islet ATAC-seq peaks, we intersected them with ChIP-seq data of histone modifications in human islets from the Roadmap Epigenomics Consortium24. Histone marks associated with active chromatin (H3K4me1, H3K4me3, and H3K27ac) were enriched at islet ATAC-seq peaks of non-diabetic donors (q < 0.001) (Fig. 3a). In contrast, only a small fraction of histone marks associated with heterochromatin (H3K27me3 and H3K9me3) overlap with ATAC-seq peaks (Fig. 3a). A similar overlap between histone modifications and ATAC-seq peaks was observed in islets from T2D donors (Supplemental Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

(a) Bar graph of overlapping islet ATAC-seq peaks in non-diabetic donors and different histone modifications. Based on chi-square tests and false discovery rate (FDR) analysis (q < 0.001, P < 9 × 10−153) more islet ATAC-seq peaks than expected overlapped with H3K4me1, H3K4me3, and H3K27ac and less peaks than expected overlapped with H3K27me3, H3K9me3 and H3K36me3. (b) Representative sequencing tracks for the SLC2A2 locus show ATAC-seq peaks that overlap with H3K4me1 and H3K27ac in human islets. The ATAC-seq data have been normalized to take sequencing depth into account and the scale on the y-axis was chosen for optimal visualization of peaks for each sample.

We also studied enrichment of histone modifications at islet open chromatin regions annotated to different genomic regions i.e. TSS, exons, introns, TTS and intergenic regions (Fig. 3a and Supplemental Fig. 3). For example, the mark associated with active promoters, H3K4me3, is enriched at the open chromatin regions (ATAC-seq peaks) annotated to TSS-200 and TSS-1500 regions (q < 0.001), whereas, the heterochromatin mark H3K27me3 only overlaps with ~1.5% of ATAC-seq peaks in these regions. Other modifications associated with active genes (H3K4me1 and H3K27ac) are also enriched at open chromatin regions annotated to TSS-200 and TSS-1500 regions (q < 0.001).

H3K4me1 and H3K27ac are known to be enriched at enhancer regions. Moreover, the presence of both H3K27ac and H3K4me1 indicates active enhancers while H3K4me1 alone associates with inactive enhancers25,26. Open chromatin regions annotated to intron and intergenic regions may also represent enhancers. We found that histone marks associated with enhancer regions are enriched at ATAC-seq peaks annotated to intron and intergenic regions in islets (q < 0.001) (Fig. 3a and Supplemental Fig. 3). We further used this approach to classify active enhancers in the open chromatin regions of islets and identified ~5,000 ATAC-seq peaks at introns and ~2,000 peaks at intergenic regions that overlap with both H3K4me1 and H3K27ac, which is more than expected by chance (q < 0.001) (Fig. 3a, Supplemental Fig. 3 and Supplemental Tables 3–4). Interestingly, some ATAC-seq peaks overlapping with both these marks are annotated to genes that have islet specific function and/or have been associated with diabetes by GWAS e.g., TCF7L2, SLC2A2, FOXO1 and HNF1B27. Sequencing tracks annotated to SLC2A2 that overlap with both H3K4me1 and H3K27ac are presented in Fig. 3b and Supplemental Fig. 4.

Furthermore, the FANTOM5 project has identified (permissive) functional enhancer candidates across different human cell types and tissues by using cap analysis of gene expression data (CAGE-tag)28. We used FANTOM5 data to further classify the islet open chromatin peaks and found 6,475 ATAC-seq peaks that are located at permissive enhancer regions. These 6,475 FANTOM5 enhancer / open chromatin regions overlap with 2,109 regions also covered by H3K4me1-H3K27ac marks (Supplemental Table 7). Numerous genes annotated to these putative enhancer regions e.g. CACNA1D, GLIS3, GRB10, HDAC9, HNF1B, INSIG2, PAX6, PDK4, SLC2A2 and TXNIP are known to be involved in T2D and islet function27,29–32.

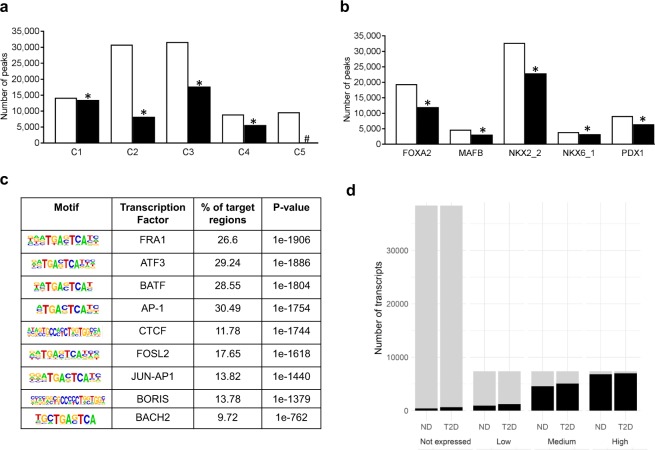

To further classify the open chromatin regions in human islets, we used data generated by Pasquali et al. where promoters, inactive enhancers, active enhancers, and CTCF bound sites were classified11. A large number of their classified promoters (C1 sites), active enhancers (C3 sites) and CTCF bound sites (C4 sites) are located at islet ATAC-seq open chromatin regions in non-diabetic donors (Fig. 4a and Supplemental Table 8). However, smaller proportions of inactive enhancers (C2 sites) and other sites (C5 sites) overlap with the islet ATAC-seq open chromatin regions. These data further show that open chromatin regions are mainly accessible to active and functional REs. It should further be noticed that genes of importance for islet function and diabetes such as PDX1, TCF7L2, FOXA2, FOXO1, NEUROD1 and BACH2 have C1, C3 or both these sites at their ATAC-seq open chromatin regions. Similar results were found in T2D donors, where also large proportions of C1, C3 and C4 sites overlap with the open chromatin regions, while smaller proportions of C2 and C5 sites overlap with ATAC-seq peaks (Supplemental Fig. 5a).

Figure 4.

(a) Bar graph of overlapping classified promoters (C1 sites), inactive enhancers (C2 sites), active enhancers (C3 sites), CTCF bound sites (C4 sites) and other sites (C5) and islet ATAC-seq peaks generated in non-diabetic donors. White bars (Peaks) represent classified promoter regions generated by Pasquali et al.11, black bars (Overlaps) represent ATAC-seq peaks that overlap with classified promoter regions. Based on chi-square tests there were significantly more ATAC-seq peaks than expected by chance overlapping with C1, C2, C3 and C4 (*p < 0.00001, q < 0.01) while significantly less than expected overlapping with C5 (#p < 0.00001, q < 0.01). (b) Bar graph of overlapping transcription factor binding sites and islet ATAC-seq peaks generated in non-diabetic donors. White bars (All sites) represent transcription factor binding sites classified by Pasquali et al.11, while black bars (Overlaps) represent ATAC-seq peaks that overlap with transcription factor binding sites. The binding of all these transcription factors was enriched in islet ATAC-seq peaks with p < 0.001 (*q < 0.018). The classified promoters and transcription factor binding sites were generated by Pasquali et al.11. (c) Enrichment of transcription factor recognition sequences in ATAC-seq peaks of non-diabetic donors based on HOMER17. (d) Islet ATAC-seq peaks are enriched close to high-expressed transcripts. Here, we identified non-expressed transcripts based on transcript per million <0.1 and then divided the expressed transcripts into three equally sized groups that we categorize into low-, medium- and high-expressed transcripts. Proportion of non-, low-, medium-, and high-expressed transcripts that are within 1500 bp of a peak summit. As seen, ATAC-seq peaks were annotated to the majority of high-expressed transcripts, while only a small proportion of non-expressed genes have open chromatin nearby. There was also a clear gradual increase in the proportion of genes with increasing expression level. All three groups of expressed genes were significantly enriched based on chi-square testing (q < 0.001). T2D represents type 2 diabetes and ND represents non-diabetic. Gray region represents genes >1500 bp away from an ATAC-seq peak and black regions represents genes ≤1500 bp away from an ATAC-seq peak.

Enrichment of transcription factor binding at open chromatin regions in human islets

We proceeded to relate the ATAC-seq open chromatin regions with genomic binding of islets-specific TFs using ChIP-seq data from Pasquali et al. where they mapped FOXA2, MAFB, PDX1, NKX6.1 and NKX2.2 binding in human islets11. The binding of all these TFs was enriched in islet ATAC-seq peaks (p < 0.001) (Fig. 4b and Supplemental Fig. 5b), supporting that most of these TFs are located at chromatin accessible regions. We then used HOMER to identify enriched putative TF motifs in the open chromatin regions of islets (Supplemental Table 9). The most significantly enriched motifs in the open chromatin regions of non-diabetic islet donors include those of FRA1, ATF3, BATF, AP-1, CTCF, FOSL2, AP-1, BORIS, and BACH2 (Fig. 4c). We also observed significant enrichment of motifs for islet specific TFs including MAFA, NEUROD1, PDX1 and NKX6.1 in the ATAC-seq peaks (Supplemental Table 9).

Expression levels in relation to open chromatin regions in human islets

To explore the relationship between open chromatin and gene expression levels, we used islet ATAC-seq and RNA-seq data generated in the same donors (5 T2D and 5 non-diabetic). A total of 60,517 GENCODE transcripts were categorized as either not expressed (38,428 transcripts, based on Transcript per Million (TPM) < 0.1) or as low- (7,363), medium- (7,363) and high-expressed (7,363) transcripts based on three equally sized groups of expressed transcripts (TPM > 0.1). While ATAC-seq peaks were annotated to the majority of high-expressed transcripts, only a small proportion of non-expressed genes have open chromatin nearby (Fig. 4d). There was also a clear gradual increase in the proportion of genes with annotated ATAC-seq peaks from the low- to medium- and high-expression genes. Notably, several genes with important function in islets such as PDX1, GCG, FOXA2 and NEUROD1 are in the high-expressed category (data not shown). These data support that the chromatin is more open in high-expressed than in non-expressed genes. We also generated a Venn diagram showing that ATAC-seq peaks were annotated to the majority of high-expressed transcripts, while only a small proportion of non-expressed genes have open chromatin nearby (Supplemental Fig. 6).

Differential methylated regions at open chromatin regions in human islets

DNA methylation may inhibit the binding of TFs to DNA in a cell specific manner. We recently identified ~25,000 differentially methylated regions (DMRs) in islets of T2D versus non-diabetic donors by using whole-genome bisulfite sequencing and these DMRs were enriched in binding sites for islet-specific TFs7. Here, we found that these T2D-associated DMRs are located at 7,412 open chromatin regions in human islets, including regions annotated to PDX1 and SLC20A2 (Supplemental Table 10).

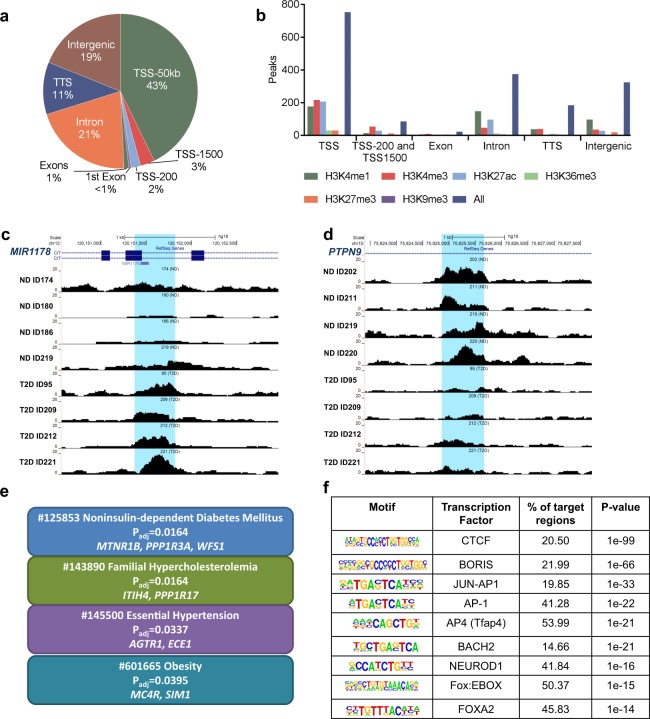

Open chromatin regions differ in islets from T2D versus non-diabetic donors

To identify T2D-associated changes in the open chromatin landscape, we used Fisher’s exact test to examine whether islet ATAC-seq peaks were more prevalent in T2D versus non-diabetic donors. Here, 1,078 open chromatin peaks were found to differ between T2D and non-diabetic islet donors (Supplemental Table 11). The majority (1,044) of these 1,078 peaks were enriched in T2D donors. The genomic distribution of these 1,078 peaks is presented in Fig. 5a and some of them are marked with histone modifications associated with open chromatin (Fig. 5b). Interestingly, several of these genes e.g. CLEC16A, ELAVL4 (also known as HuD), FOXO3, FST, GLIS3, MTNR1B, PARK2, WFS1 and ZMIZ1 have previously been associated with T2D by GWAS and/or found to affect islet function7,33–40. Sequencing tracks of ATAC-seq peaks that are more prevalent in either donors with T2D (e.g. MIR1178) or non-diabetics (e.g PTPN9) are presented in Fig. 5c,d and Supplemental Fig. 7a,b. Interestingly, MIR1178 is a suppressor of CHIP, also known as STUB1 (STIP1 homology and U-box containing protein 1), and loss of CHIP is associated with diabetes41,42.

Figure 5.

(a) Proportions of differential islet ATAC-seq peaks of type 2 diabetic versus non-diabetic donors annotated to different genomic regions. (b) Bar graph of differential islet ATAC-seq peaks of type 2 diabetic versus non-diabetic donors that overlap with histone modifications. (c-d) Sequencing tracks of ATAC-seq peaks that are more prevalent in donors with type 2 diabetes (annotated to MIR1178) (c) or non-diabetics (annotated to PTPN9) (d). The ATAC-seq data have been normalized to take sequencing depth into account. (e) Disease related pathways based on enrichment of genes annotated to differential islet ATAC-seq peaks of type 2 diabetic versus non-diabetic donors. The same pathways were significant when analyzing genes annotated to the 1,044 peaks enriched in T2D versus non-diabetic donors (Padj = 0.0159, Padj = 0.0175, Padj = 0.324 and Padj = 0.0425, respectively). Padj are adjusted by FDR. (f) Enrichment of transcription factor recognition sequences in differential islet ATAC-seq peaks of type 2 diabetic versus non-diabetic donors based on HOMER17.

We then used WebGestalt (http://www.webgestalt.org) and the functional database OMIM to identify disease-related pathways with enrichment of genes that had islet ATAC-seq peaks with a different prevalence in T2D versus non-diabetic donors. Interestingly, categories including Noninsulin-dependent Diabetes Mellitus, Familial Hypercholesterolemia, Essential Hypertension and Obesity were significantly enriched (Fig. 5e). Of note, Familial hypercholesterolemia, hypertension and obesity are linked to risk of T2D and/or islet function36,43,44. The same pathways were significant when only analyzing genes annotated to peaks that are enriched in T2D donors, while no pathway was significant when analyzing genes annotated to peaks that are enriched in non-diabetic donors.

We proceeded to examine if ATAC-seq peaks with a different prevalence in T2D islets are located in specific REs by using data from Pasquali et al.11. Among these 1,078 open chromatin peaks, 3.7% overlap with classified promoters (C1 sites), 19.4% with inactive enhancers (C2 sites), 22.4% with active enhancers (C3 sites) and 11.7% with CTCF bound sites (C4 sites) (Supplemental Table 12). Hence, the peaks with different prevalence in T2D islets are most common at classified enhancer regions (~42%).

To identify TF motifs significantly enriched at the 1,078 ATAC-seq peaks with different prevalence in T2D, we performed a motif search using HOMER. Intriguingly, motifs specific to key TFs in islets, including BORIS, BACH2, FOXO1, FOXA2, NEUROD1, MAFA and PDX1 as well as the motif for CTCF were significantly enriched in the ATAC-seq peaks with different prevalence in T2D islets (Supplemental Table 13). Some of the most significant motifs are presented in Fig. 5f. CTCF is an insulator transcription factor, which plays a key role in maintaining higher order chromatin structure by facilitating the interactions between the regulatory sequences. We further examined if the expression of any of the TFs presented in Fig. 5f exhibit differential expression in islets from donors with T2D. Interestingly, the expression of BACH2 was elevated in T2D versus control human islets (p < 0.036)5.

We then determined if the 128 SNPs associated with T2D23 and 2,207 SNPs in LD with these are located within the 1,078 islet ATAC-seq peaks with different prevalence in T2D islets. We found that rs3821943 and rs508419 annotated to WFS1 and ANK1, respectively, are located in ATAC-seq peaks with different prevalence in T2D islets (Supplemental Tables 6 and 11).

We next examined whether the genes annotated to ATAC-seq peaks with different prevalence in T2D islets also showed altered expression in T2D versus non-diabetic islets. Using the RNA-seq data from a previous study5, we identified 90 genes that have both differential gene expression and different open chromatin regions in T2D islets (Supplemental Table 14). These include genes with known function in islets and diabetes such as ATP6V1H, SOX6, SOCS1 and STX1145–48. ATAC-seq peaks annotated to SOX6 are presented in Supplemental Fig. 8a. Moreover, based on RNA-seq data from the donors included the present study, we found 54 genes that had both differential gene expression and open chromatin regions in T2D islets (Supplemental Table 15). The majority of these genes (~70%) had higher expression and more open chromatin in T2D islets.

We then used R Diffbind and edgeR packages19. These data are presented in a volcano plot in Supplemental Fig. 8b. We found 88 ATAC-seq peaks that were both differential in T2D islets and more prevalent in T2D versus non-diabetic donors based on Fisher’s exact test (Supplemental Table 16). These include MIR1178 (Fig. 5c), BACH1, GABRA2 and STX11 which are known to play a role in beta-cells, islets and diabetes41,42,49. Using gene ontology, we further found that the anion transmembrane transporter activity pathway (http://amigo.geneontology.org/amigo/term/GO:0008509) was significantly enriched among the genes annotated to the 88 differential ATAC-seq peaks (P = 8 × 10−6, q = 0.02, CTNS, SLC16A14, ANO6, ANO5, GABRA2 and SLC16A7 contributed to the enrichment).

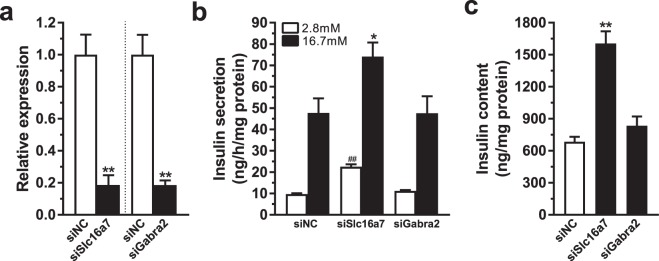

We finally asked if genes annotated to ATAC-seq peaks with different prevalence (based on both Fisher’s exact test and R Diffbind) and with differential expression in T2D versus non-diabetic islets have a functional role in beta-cells. Two genes, SLC16A7 and GABRA2, were selected for functional follow-up experiments based on these criteria (Supplemental Tables 14 and 15) together with a potential role in beta-cell function50,51. Of note, both GABRA2 and SLC16A7 contributed to the enrichment of the Anion transmembrane transporter activity pathway which was significantly enriched among the genes annotated to the 88 differential ATAC-seq peaks. While SLC16A7 showed increased expression and enrichment of ATAC-seq peaks, GABRA2 had decreased expression and less ATAC-seq peaks in T2D islets. First, Slc16a7 and Gabra2 were silenced in rat clonal beta-cells (Fig. 6a) and we then measured insulin secretion at basal (2.8 mM) and stimulatory (16.7 mM) glucose levels. Silencing of Slc16a7 resulted in increased glucose-stimulated and basal insulin secretion as well as increased insulin content (Fig. 6b,c), which fits with the fact that non-diabetic people have lower expression levels and fewer ATAC-seq peaks of this gene. On the other hand, silencing of Gabra2 only had a nominal effect on basal insulin secretion.

Figure 6.

(a) Knockdown of Slc16a7 and Gabra2 as quantified by qPCR (**p < 0.01). (b) Knockdown of Slc16a7 increased both basal (2.8 mM) and glucose-stimulated (16.7 mM) insulin secretion, while knockdown of Gabra2 has no significant effect (##p < 0.01 vs siNC 2.8 mM, *p < 0.05 vs siNC 16.7 mM). (c) Insulin content is increased in cells deficient for Slc16a7 while there is no significant difference after knockdown of Gabra2 (**p < 0.01).

Discussion

This study used ATAC-seq to establish T2D-associated changes in the open chromatin landscape of human islets. Interestingly, we found 1,078 differential ATAC-seq peaks in T2D versus control islets. T2D is driven by interactions between genetic and environmental factors. A major breakthrough in genetic research on T2D came with GWAS where ~100 loci were identified2. GWAS placed the pancreatic islets in the center of attention as many of the loci were associated with impaired insulin secretion3. Although large efforts have been made to understand how these SNPs may cause disease further studies are needed. Interestingly, several risk genes identified by GWAS such as HHEX, HMGA2, GLIS3, MTNR1B and WFS135,36,38,52 had differential ATAC-seq peaks in T2D islets annotated to them. It is possible that T2D-associated SNPs change the chromatin structure and thereby gene regulation. In support for this, we have previously shown that SNPs linked to HHEX, HMGA2 and WFS1 associate with epigenetic changes, e.g. differential DNA methylation, in human islets6,38. Here, we found T2D-associated differences in ATAC-seq peaks annotated to genes which also show differential DNA methylation patterns in islets from T2D versus non-diabetic donors e.g. SOX66,7 (Supplemental Fig. 8c). Additionally, several of the genes annotated to differential ATAC-seq peaks have previously been shown to affect insulin secretion. For example, MTNR1B expression is increased and insulin secretion decreased in islets from G-allele carriers which increases T2D risk. MTNR1B deficient mice secreted more insulin and MTNR1B overexpression affect insulin secretion in beta-cells35. Moreover, beta-cell mass and insulin secretion were reduced in rats where exon 5 of Wfs1 was deleted53. Also, GLIS3 controlled beta-cell proliferation in response to high-fat feeding and Glis3 deficiency leads to diabetes54. The potential causal consequences of differences in ATAC-seq peaks between donors with T2D and controls should be examined further and some caution should be considered regarding the gene annotations of these peaks. Here, we performed functional follow-up experiments of two identified genes with both differential ATAC-seq peaks and expression in islets from donors with T2D versus non-diabetic controls. We found that knockdown of Slc16a7, which exhibits fewer ATAC-seq peaks and lower expression in islets from non-diabetic donors, increased both insulin secretion and content in beta-cells. This supports a role for the identified chromatin differences in the secretory insufficiency that is characteristic of T2D. We cannot exclude that altered levels of Gabra2 affect other phenotypes than impaired insulin secretion, characterizing islets from donors with T2D.

Insufficient insulin secretion is a hallmark of T2D. Altered expression of insulin and numerous other genes seems to contribute to islet-dysfunction5,55. Gene expression is regulated by TFs that bind to DNA in open chromatin regions in a sequence-specific manner9,10,56. Given this, we studied TF binding and putative TF binding motifs in open chromatin regions of T2D and non-diabetic islets. As may be expected, ATAC-seq peaks were enriched in regions occupied by islet-specific TFs such as FOXA2, MAFB, NKX2.2, NKX6.1 and PDX1. These TFs are important for islet development and function as well as for proper insulin expression21. For example, PDX1 regulates development of beta-cells and insulin expression in mature beta-cells. While expression of PDX1 seems to be regulated by epigenetic mechanisms in T2D islets6,7,57, its function may be controlled by the chromatin structure and PDX1’s ability to bind to its target genes. Putative TF binding motifs were also enriched in the islet ATAC-seq peaks. Interestingly, the FRA1 motif was the most significantly enriched among islet ATAC-seq peaks. Our result is in line with data from a recent study where the motif for FRA1 was enriched in ATAC-seq peaks in alpha- and beta-cells14. FRA1 is involved in MAPK signaling and oxidative stress pathways. However, there is limited knowledge of its role in islets and future studies evaluating its binding and function would be interesting. The motif for CTCF was also significantly enriched in our islet ATAC-seq peaks as well as in the peaks that differed between T2D and non-diabetic islet donors. Varshney et al. previously did a reconstruction of the CTCF motif using ATAC-seq TF footprint allelic bias data of two islet donors15 and Ackerman et al. found this motif to be enriched in ATAC-seq peaks from sorted alpha-cells14. Moreover, alpha- and beta-cell-specific peaks e.g. ARX, GCG, DPP4 and SLC27A6 presented by Ackerman et al. were also identified in our islet ATAC-seq data14.

Epigenetic modifications are closely linked to chromatin structure. We have studied epigenetic alterations in T2D versus control islets by genome-wide DNA methylation analyses6,7. Here, we integrated ATAC-seq peaks with the methylome and found that T2D-associated DMRs are located at 7,412 open chromatin regions in human islets. Earlier, we found DMRs in and decreased expression of PARK2 in T2D versus control islets7. PARK2 regulates mitochondrial function in beta-cells and its silencing impaired insulin secretion. Here, we fund differential ATAC-seq peaks annotated to PARK2 in T2D islets, further supporting its role in diabetes. Given the importance of posttranslational modifications of histones, we related islet ATAC-seq peaks to histone marks associated with enhancers, active promoters and inactive genes. While histone marks of active enhancers and promoters were enriched, histone marks of inactive genes were underrepresented in open chromatin regions. These results were further supported by CAGE data and data generated by Pasquali et al.11,28 and are in line with muscle ATAC-seq data58.

There are advantages with ATAC-seq compared with earlier methods. It requires smaller number of cells and has higher sensitivity and resolution. Indeed, we only used ~30 islets per donor9,12. It should be noted that the number of islets used for ATAC-seq was optimized and 25–30 islets per donor gave the best result. Importantly, our data seem technically sound since a large proportion of our ATAC-seq open chromatin peaks overlapped with ENCODE validated peaks. Of note, islets contain several cell types. However, our previous data support that there are no differences in islet cell composition between T2D and non-diabetic donors6. Moreover, in the present study, we found no differences in expression of islet cell specific genes in T2D versus control donors further supporting no differences in islet cell composition in our cohort (Supplemental Fig. 9).

Additionally, since the current study included data from 15 donors, the differences in islet ATAC-seq peaks identified between donors with T2D and controls should be replicated in future studies. The donors with T2D have a higher BMI than the controls and it is possible that this affects our results. Subsequently, it will be of interest to only study the effect of BMI on the chromatin structure in human islets. Also since whole islets contain several different cell types, and these cell types may be in different proportions in different donors, future studies should perform ATAC-seq in sorted islet cells from donors with T2D and controls. To maximize our statistical power regarding analysis of RNA-seq data, we used both published expression data from a larger number of islet donors including 12 with T2D and 66 controls5 as well as RNA-seq data from the donors with available ATAC-seq data.

Together, we provide the first map of open chromatin regions in islets from numerous T2D donors. Dissection of open chromatin regions revealed enrichment for islet-specific TF binding motifs and enhancer regions. Numerous SNPs associated with T2D reside within islet ATAC-seq peaks. T2D candidate genes showed differential ATAC-seq peaks in diabetic versus non-diabetic islets. Our study improves current understanding of the link between altered chromatin structure and disease.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank the Nordic Network for Clinical Islet Transplantation (JDRF award 31-2008-413), the tissue isolation teams and Human Tissue Laboratory within EXODIAB/Lund University Diabetes Centre. Sequencing was performed by the National Genomics Infrastructure, Science for Life Laboratory, Stockholm, Sweden. We also would like to thank WABI for the bioinformatics support. This work was supported by grants from the Novo Nordisk foundation, Swedish Research Council, Region Skåne (ALF), ERC-Co Grant (PAINTBOX, No 725840), Albert Påhlsson Foundation, Kungliga Fysiografiska Sällskapet’s Nilson-Ehle donations, Thuring’s Foundation, the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research for IRC15-0067 and Åke Wiberg’s foundation. RA and PU were supported by a grant from the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation to the Wallenberg Advanced Bioinformatics Infrastructure and Bioinformatics Long-term Support.

Author Contributions

M.B. designed and conducted the study, performed lab work, collected, analyzed and interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript. R.A., P.U., T.R., K.B., C.D. and P.V. analyzed and interpreted data and reviewed and edited the manuscript. C.L. designed and conducted the study, interpreted data, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. M.B. and C.L. are guarantors of this work and, as such, had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data Availability

Datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are available in the GEO repository, accession number GSE50398 and GSE129383, or are available upon request.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

1/29/2020

An amendment to this paper has been published and can be accessed via a link at the top of the paper.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-44076-8.

References

- 1.Bacos K, et al. Blood-based biomarkers of age-associated epigenetic changes in human islets associate with insulin secretion and diabetes. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11089. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Franks PW, McCarthy MI. Exposing the exposures responsible for type 2 diabetes and obesity. Science. 2016;354:69–73. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf5094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosengren AH, et al. Reduced insulin exocytosis in human pancreatic beta-cells with gene variants linked to type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2012;61:1726–1733. doi: 10.2337/db11-1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gaulton KJ, et al. Genetic fine mapping and genomic annotation defines causal mechanisms at type 2 diabetes susceptibility loci. Nat Genet. 2015;47:1415–1425. doi: 10.1038/ng.3437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fadista J, et al. Global genomic and transcriptomic analysis of human pancreatic islets reveals novel genes influencing glucose metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:13924–13929. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1402665111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dayeh T, et al. Genome-wide DNA methylation analysis of human pancreatic islets from type 2 diabetic and non-diabetic donors identifies candidate genes that influence insulin secretion. PLoS genetics. 2014;10:e1004160. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Volkov P, et al. Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing of Human Pancreatic Islets Reveals Novel Differentially Methylated Regions in Type 2 Diabetes Pathogenesis. Diabetes. 2017;66:1074–1085. doi: 10.2337/db16-0996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henikoff S. Nucleosome destabilization in the epigenetic regulation of gene expression. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:15–26. doi: 10.1038/nrg2206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Consortium EP. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature. 2012;489:57–74. doi: 10.1038/nature11247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thurman RE, et al. The accessible chromatin landscape of the human genome. Nature. 2012;489:75–82. doi: 10.1038/nature11232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pasquali L, et al. Pancreatic islet enhancer clusters enriched in type 2 diabetes risk-associated variants. Nat Genet. 2014;46:136–143. doi: 10.1038/ng.2870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gaulton KJ, et al. A map of open chromatin in human pancreatic islets. Nat Genet. 2010;42:255–259. doi: 10.1038/ng.530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stitzel ML, et al. Global epigenomic analysis of primary human pancreatic islets provides insights into type 2 diabetes susceptibility loci. Cell Metab. 2010;12:443–455. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ackermann AM, Wang Z, Schug J, Naji A, Kaestner KH. Integration of ATAC-seq and RNA-seq identifies human alpha cell and beta cell signature genes. Mol Metab. 2016;5:233–244. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2016.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Varshney A, et al. Genetic regulatory signatures underlying islet gene expression and type 2 diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:2301–2306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1621192114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buenrostro JD, Giresi PG, Zaba LC, Chang HY, Greenleaf WJ. Transposition of native chromatin for fast and sensitive epigenomic profiling of open chromatin, DNA-binding proteins and nucleosome position. Nat Methods. 2013;10:1213–1218. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heinz S, et al. Simple combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and B cell identities. Mol Cell. 2010;38:576–589. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hall E, et al. Sex differences in the genome-wide DNA methylation pattern and impact on gene expression, microRNA levels and insulin secretion in human pancreatic islets. Genome Biol. 2014;15:522. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0522-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:139–140. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koster J, Rahmann S. Snakemake–a scalable bioinformatics workflow engine. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:2520–2522. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaneto H, et al. PDX-1 and MafA play a crucial role in pancreatic beta-cell differentiation and maintenance of mature beta-cell function. Endocr J. 2008;55:235–252. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.K07E-041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thurner, M. et al. Integration of human pancreatic islet genomic data refines regulatory mechanisms at Type 2 Diabetes susceptibility loci. Elife 7, 10.7554/eLife.31977 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Scott RA, et al. An Expanded Genome-Wide Association Study of Type 2 Diabetes in Europeans. Diabetes. 2017;66:2888–2902. doi: 10.2337/db16-1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kundaje Anshul, Meuleman Wouter, Ernst Jason, Bilenky Misha, Yen Angela, Heravi-Moussavi Alireza, Kheradpour Pouya, Zhang Zhizhuo, Wang Jianrong, Ziller Michael J., Amin Viren, Whitaker John W., Schultz Matthew D., Ward Lucas D., Sarkar Abhishek, Quon Gerald, Sandstrom Richard S., Eaton Matthew L., Wu Yi-Chieh, Pfenning Andreas R., Wang Xinchen, Claussnitzer Melina, Liu Yaping, Coarfa Cristian, Harris R. Alan, Shoresh Noam, Epstein Charles B., Gjoneska Elizabeta, Leung Danny, Xie Wei, Hawkins R. David, Lister Ryan, Hong Chibo, Gascard Philippe, Mungall Andrew J., Moore Richard, Chuah Eric, Tam Angela, Canfield Theresa K., Hansen R. Scott, Kaul Rajinder, Sabo Peter J., Bansal Mukul S., Carles Annaick, Dixon Jesse R., Farh Kai-How, Feizi Soheil, Karlic Rosa, Kim Ah-Ram, Kulkarni Ashwinikumar, Li Daofeng, Lowdon Rebecca, Elliott GiNell, Mercer Tim R., Neph Shane J., Onuchic Vitor, Polak Paz, Rajagopal Nisha, Ray Pradipta, Sallari Richard C., Siebenthall Kyle T., Sinnott-Armstrong Nicholas A., Stevens Michael, Thurman Robert E., Wu Jie, Zhang Bo, Zhou Xin, Beaudet Arthur E., Boyer Laurie A., De Jager Philip L., Farnham Peggy J., Fisher Susan J., Haussler David, Jones Steven J. M., Li Wei, Marra Marco A., McManus Michael T., Sunyaev Shamil, Thomson James A., Tlsty Thea D., Tsai Li-Huei, Wang Wei, Waterland Robert A., Zhang Michael Q., Chadwick Lisa H., Bernstein Bradley E., Costello Joseph F., Ecker Joseph R., Hirst Martin, Meissner Alexander, Milosavljevic Aleksandar, Ren Bing, Stamatoyannopoulos John A., Wang Ting, Kellis Manolis. Integrative analysis of 111 reference human epigenomes. Nature. 2015;518(7539):317–330. doi: 10.1038/nature14248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Creyghton MP, et al. Histone H3K27ac separates active from poised enhancers and predicts developmental state. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:21931–21936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016071107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heintzman ND, et al. Histone modifications at human enhancers reflect global cell-type-specific gene expression. Nature. 2009;459:108–112. doi: 10.1038/nature07829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Groop L, Pociot F. Genetics of diabetes–are we missing the genes or the disease? Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2014;382:726–739. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Andersson R, et al. An atlas of active enhancers across human cell types and tissues. Nature. 2014;507:455–461. doi: 10.1038/nature12787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dayeh T, et al. DNA methylation of loci within ABCG1 and PHOSPHO1 in blood DNA is associated with future type 2 diabetes risk. Epigenetics. 2016;11:482–488. doi: 10.1080/15592294.2016.1178418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reinbothe TM, et al. The human L-type calcium channel Cav1.3 regulates insulin release and polymorphisms in CACNA1D associate with type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2013;56:340–349. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2758-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mitchell RK, et al. The transcription factor Pax6 is required for pancreatic beta cell identity, glucose-regulated ATP synthesis, and Ca(2+) dynamics in adult mice. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:8892–8906. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.784629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Malmgren S, et al. Coordinate changes in histone modifications, mRNA levels, and metabolite profiles in clonal INS-1 832/13 beta-cells accompany functional adaptations to lipotoxicity. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:11973–11987. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.422527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee EK, et al. RNA-binding protein HuD controls insulin translation. Mol Cell. 2012;45:826–835. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Soleimanpour SA, et al. Diabetes Susceptibility Genes Pdx1 and Clec16a Function in a Pathway Regulating Mitophagy in beta-Cells. Diabetes. 2015;64:3475–3484. doi: 10.2337/db15-0376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tuomi T, et al. Increased Melatonin Signaling Is a Risk Factor for Type 2 Diabetes. Cell Metab. 2016;23:1067–1077. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hall E, et al. Effects of palmitate on genome-wide mRNA expression and DNA methylation patterns in human pancreatic islets. BMC medicine. 2014;12:103. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-12-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim-Muller JY, et al. Metabolic inflexibility impairs insulin secretion and results in MODY-like diabetes in triple FoxO-deficient mice. Cell Metab. 2014;20:593–602. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dayeh TA, et al. Identification of CpG-SNPs associated with type 2 diabetes and differential DNA methylation in human pancreatic islets. Diabetologia. 2013;56:1036–1046. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2815-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhao C, et al. Overcoming Insulin Insufficiency by Forced Follistatin Expression in beta-cells of db/db Mice. Mol Ther. 2015;23:866–874. doi: 10.1038/mt.2015.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thomsen SK, et al. Systematic Functional Characterization of Candidate Causal Genes for Type 2 Diabetes Risk Variants. Diabetes. 2016;65:3805–3811. doi: 10.2337/db16-0361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cao Z, et al. MiR-1178 promotes the proliferation, G1/S transition, migration and invasion of pancreatic cancer cells by targeting CHIP. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0116934. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McDonough, H. et al. Loss of CHIP Expression Perturbs Glucose Homeostasis and Leads to Type II Diabetes through Defects in Microtubule Polymerization and Glucose Transporter Localization. bioRxiv, 1–32 (2017).

- 43.Xu H, et al. Familial Hypercholesterolemia and Type 2 Diabetes in the Old Order Amish. Diabetes. 2017;66:2054–2058. doi: 10.2337/db17-0173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Satoh M, et al. Hypertension promotes islet morphological changes with vascular injury on pre-diabetic status in SHRsp rats. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2014;36:159–164. doi: 10.3109/10641963.2013.804539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lu H, Yang Y, Allister EM, Wijesekara N, Wheeler MB. The identification of potential factors associated with the development of type 2 diabetes: a quantitative proteomics approach. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2008;7:1434–1451. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700478-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zaitseva II, et al. Suppressor of cytokine signaling-1 inhibits caspase activation and protects from cytokine-induced beta cell death. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:3787–3795. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0151-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sintov E, et al. Inhibition of ZEB1 expression induces redifferentiation of adult human beta cells expanded in vitro. Sci Rep. 2015;5:13024. doi: 10.1038/srep13024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Andersson SA, et al. Reduced insulin secretion correlates with decreased expression of exocytotic genes in pancreatic islets from patients with type 2 diabetes. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2012;364:36–45. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2012.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kondo K, et al. Bach1 deficiency protects pancreatic beta-cells from oxidative stress injury. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2013;305:E641–648. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00120.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Halestrap AP. The SLC16 gene family - structure, role and regulation in health and disease. Mol Aspects Med. 2013;34:337–349. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Korol SV, et al. Functional Characterization of Native, High-Affinity GABAA Receptors in Human Pancreatic beta Cells. EBioMedicine. 2018;30:273–282. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rönn T, et al. A common variant in MTNR1B, encoding melatonin receptor 1B, is associated with type 2 diabetes and fasting plasma glucose in Han Chinese individuals. Diabetologia. 2009;52:830–833. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1297-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Plaas M, et al. Wfs1- deficient rats develop primary symptoms of Wolfram syndrome: insulin-dependent diabetes, optic nerve atrophy and medullary degeneration. Sci Rep. 2017;7:10220. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-09392-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang Y, Chang BH, Chan L. Sustained expression of the transcription factor GLIS3 is required for normal beta cell function in adults. EMBO Mol Med. 2013;5:92–104. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201201398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yang BT, et al. Insulin promoter DNA methylation correlates negatively with insulin gene expression and positively with HbA(1c) levels in human pancreatic islets. Diabetologia. 2011;54:360–367. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-1967-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.MacNeil LT, et al. Transcription Factor Activity Mapping of a Tissue-Specific in vivo Gene Regulatory Network. Cell Syst. 2015;1:152–162. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2015.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yang BT, et al. Increased DNA Methylation and Decreased Expression of PDX-1 in Pancreatic Islets from Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Mol Endocrinol. 2012 doi: 10.1210/me.2012-1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Scott LJ, et al. The genetic regulatory signature of type 2 diabetes in human skeletal muscle. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11764. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are available in the GEO repository, accession number GSE50398 and GSE129383, or are available upon request.