Abstract

Objectives

The aim was to compare adherence to antipsychotics (APs), healthcare resource utilization (HRU), and costs before and after once-every-3-months paliperidone palmitate (PP3M) initiation in patients with schizophrenia.

Methods

Medicaid data (Iowa, Kansas, and Missouri; 1/2014–3/2017) were used to identify adults with at least one PP3M claim, ≥ 12 months of pre-index enrollment, and at least two schizophrenia diagnoses. Adequate treatment with once-monthly paliperidone palmitate (PP1M) was required pre-PP3M transition. Generalized estimating equations were used to assess linear trends in adherence to APs, HRU, and costs over the four quarters pre-PP3M transition, and to compare monthly HRU and costs 6 months pre- and 12 months post-PP3M transition as well as adherence to APs 12 months pre- and post-PP3M transition.

Results

Among 324 patients initiated on PP3M, the mean age was 41.4 years and 36.1% were females. Over the four quarters pre-PP3M transition, the monthly number of emergency room visits, medical costs, and inpatient costs decreased, while pharmacy costs and adherence to APs increased. For patients with ≥ 12 months of follow-up (n = 151), adherence to APs (66.2 vs. 70.2%, p = 0.3758), total (US$3371 vs. US$3456; p = 0.7000), pharmacy (US$1805 vs. US$1870; p = 0.2960), and medical costs (US$1565 vs. US$1586; p = 0.9040) remained similar pre- and post-PP3M transition, while mean monthly number of 1-day mental institute visits (1.71 vs. 1.51; p < 0.01) and associated costs (US$260 vs. US$232, p = 0.01) decreased.

Conclusions

Adherence to APs, HRU, and costs were similar pre- and post-PP3M transition, suggesting that PP3M has no impact on monthly costs for patients adequately treated with PP1M, with the added flexibility of once-every-3-months dosing.

Key Points for Decision Makers

| Over the four quarters before once-every-3-months paliperidone palmitate (PP3M) transition, adherence to antipsychotics significantly improved and the increase in pharmacy costs was offset by decreasing medical costs, driven by a decrease in inpatient costs. |

| Adherence to antipsychotics, monthly healthcare resource utilization, and monthly Medicaid spending remained similar before and after PP3M transition. |

| These findings suggest that for patients adequately treated with once-monthly paliperidone palmitate, the transition to PP3M has no impact on monthly healthcare costs, with the added flexibility of once-every-3-months dosing. |

Introduction

Schizophrenia is a severe chronic mental disorder characterized by distortions of reality and disturbances of thoughts, perceptions, and emotional and social responsiveness [1]. In the US adult population, the 12-month prevalence of schizophrenia is 1.1% [1]. The educational and occupational performance of patients with schizophrenia is affected, resulting in one of the highest global disease burdens [2]. In 2002, the US societal economic burden of schizophrenia was reported to be US$62.7 billion [3], becoming US$155.7 billion in 2013 [4]. Unemployment and productivity loss due to caregiving were the leading components of the incurred cost of the disease [4].

Schizophrenia can be treated effectively with lifelong use of antipsychotic (AP) medications. However, for treatment to be effective, commitment to regularly taking the prescribed medication(s) is mandatory. Adherence and persistence to APs have previously been reported to be poor as a result of patients’ lack of thorough understanding of their disease, impaired thinking, memory difficulties, and substance abuse [5–8]. Compared to oral atypical antipsychotics (OAAs), long-acting injectable (LAI) therapies can address treatment non-adherence since they can only be administered by healthcare providers. Once-monthly paliperidone palmitate (PP1M) is an LAI that was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2009. PP1M prescribing guidelines [9] recommend to first initiate patients with schizophrenia with a dose of 234 mg on the first day of treatment and 156 mg 1 week later. Patients should then receive monthly maintenance doses; the recommended dose is 117 mg, but some patients may be administered other doses (39 mg, 78 mg, 156 mg, and 234 mg are available). The maintenance dose may be adjusted monthly. PP1M was shown to improve adherence and delay treatment failure compared to OAAs in a recent clinical trial [10]. Similarly, PP1M was shown to improve adherence and reduce economic burden compared to OAAs in the real world [6, 8, 11–15].

Longer injection intervals are expected to improve adherence to medication and therefore quality of life by reducing relapses and the number and duration of re-hospitalizations [16–18]. Following 4 months of adequate treatment with PP1M with the same dosage strength for the last two PP1M injections, patients can be transitioned to once-every-3-months paliperidone palmitate (PP3M), the only LAI with a quarterly dosing schedule. [19] Prescription guidelines for PP3M recommend the following dose conversion from the last dose of PP1M to the first dose of PP3M (PP1M dose → PP3M dose): 78 mg → 273 mg, 117 mg → 410 mg, 156 mg → 546 mg, or 234 mg → 819 mg. Prior to FDA approval in 2015, the safety and efficacy of PP3M were demonstrated in two double-blind, randomized clinical trials [20, 21]. While patients’ characteristics and treatment patterns during the period prior to PP3M initiation have been assessed [22], there is a need to assess the impact of transitioning to PP3M on treatment adherence, healthcare resource utilization (HRU), and costs. This study aims to evaluate the variation of these outcomes as the transition approaches and to compare them before and after PP3M initiation in a real-world setting.

Methods

Data Source

This study used Medicaid data from three states (Iowa, Kansas, and Missouri) from January 1, 2014 through March 31, 2017. The database includes information on enrollment eligibility, physician visits, hospitalizations, long-term care services, prescription drugs, and other services reimbursed by Medicaid. Medical claims contain diagnosis and procedure information. Prescription drug claims contain information on the name, dosage, formulation, and days of supply of the medication. In addition, the database contains information on Medicaid payments made under both the fee-for-service and managed care systems, patient out-of-pocket costs and Medicare copayments and deductibles. All available cost data reflect the Medicaid payers’ perspective prior to any discounts or rebates paid by manufacturers.

All data were de-identified and in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA).

Study Design and Patient Selection

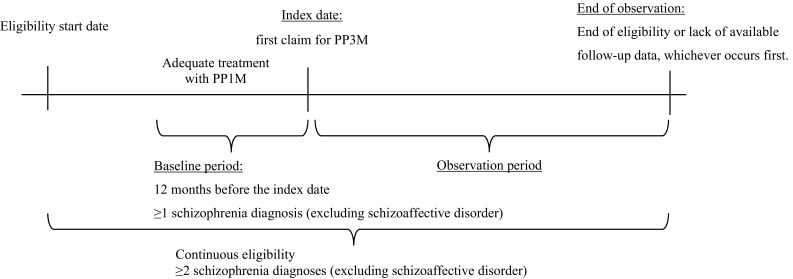

A retrospective cohort observational study design was used. The date of the first claim for PP3M was defined as the index date. The 12-month period preceding the index was defined as the baseline period. The observation (follow-up) period spanned from the index date up until the end of eligibility, death, or lack of available follow-up data, whichever occurred first (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Study design scheme. PP1M once-monthly paliperidone palmitate, PP3M once-every-3-months paliperidone palmitate

Patients were included in the study if they had at least one claim for PP3M, had at least 12 months of continuous insurance eligibility before the index date, had at least two claims with a diagnosis for schizophrenia (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) codes: 295.XX [excluding 295.7]; International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) codes: F20.XX, F21) with at least one of them in the 12-month baseline period, and were at least 18 years of age at the index date. Per the prescribing guidelines for PP3M, patients were also required to have adequate treatment with PP1M prior to PP3M initiation, with no gap of > 45 days in PP1M coverage 4 months prior to PP3M initiation, same dose strength for the last two PP1M claims prior to PP3M initiation, and appropriate dosage conversion between the last PP1M and the first PP3M claims (78 mg → 273 mg, 117 mg → 410 mg, 156 mg → 546 mg, or 234 mg → 819 mg), as per prescribing guidelines. For the comparison of adherence, HRU, and costs before and after PP3M, patients were additionally required to have at least 12 months of continuous insurance eligibility following PP3M initiation.

Outcome Measures

Demographic and clinical characteristics were assessed during the baseline period for all patients with at least 12 months of eligibility prior to the index date and with at least one diagnosis of schizophrenia who transitioned to PP3M, for those who were adequately transitioned from PP1M to PP3M, as well as for adequately transitioned patients who had at least 12 months of follow-up. Baseline characteristics included age, gender, race, state, region, insurance eligibility (capitated and dual coverage), Quan-Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score, number of unique mental health diagnoses, type of schizophrenia disorder, HRU, costs, and adherence to APs. Adherence to APs during the 12-month baseline period, during each of the four baseline quarters, as well as during the first 12 months of follow-up was measured using the proportion of days covered (PDC), defined as the sum of non-overlapping days of supply (i.e., the number of days a prescription is supposed to last) of any AP medication divided by the length of the period over which the sum was calculated (i.e., 12 months for the entire baseline period and the first 12 months of follow-up, and 3 months for the four baseline quarters):

Starting at the index date, PP3M treatment patterns were assessed and included duration of continuous PP3M therapy (defined as having a gap of no more than 45 days between the end of supply and a new claim for PP3M), number of PP3M claims, number of days between PP3M claims, dose strength of each PP3M claim, persistence to PP3M treatment (measured as the proportion of patients with a subsequent dose of PP3M after the previous dose among those with at least 4 months of observation period), and adherence to PP3M treatment. Adherence to PP3M was measured by the medication possession ratio (MPR) and PDC. The MPR was defined as the sum of days of supply for each PP3M dispensing divided by the entire exposure to PP3M:

where exposure to PP3M was defined as the number of days between the date of the first drug fill and that of the last drug refill, plus the number of days of supply of the last refill. The PDC for PP3M was calculated as the sum of non-overlapping days of supply of PP3M during the first 12 months of follow-up divided by 12 months.

Monthly all-cause HRU was assessed during each of the four quarters pre-index as well as during the 6 months pre-index and the first 12 months of follow-up. HRU was reported per patient per month for each of the following categories: outpatient visits, emergency room visits, inpatient visits, long-term care admissions, mental institute admissions, 1-day mental institute visits, home care, and other services (defined as services that did not fall under any of the aforementioned categories). Monthly all-cause pharmacy and medical costs were also assessed during each of the four quarters pre-index as well as during the 6 months pre-index and the first 12 months of follow-up. In addition to the above categories, monthly total medical costs (defined as the sum of outpatient, emergency room, inpatient, long-term care, mental institute visits, 1-day mental institute visits, home care, and other services costs) and monthly total healthcare costs (defined as the sum of pharmacy and medical costs) were calculated.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to report baseline characteristics and PP3M treatment patterns. Means, standard deviations (SDs) and medians were used for continuous variables; frequencies and percentages were used for categorical variables.

To account for within-individual correlation, generalized estimating equation (GEE) models were used to assess trends in adherence to APs, HRU, and costs over the four baseline quarters prior to the transition to PP3M. The model specifies that a relationship between the expectation of the outcome E[Y] and the indicator of the quarter (Xquarter = 1, 2, 3, or 4) is written as follows:

where g is a given link function and β0 and β1 are the regression coefficients. The coefficient β1 represents the trend in variation of the outcome over the quarters. Since patients were their own control, no other covariates were included in the models.

For the proportion of patients adherent to APs (i.e., PDC ≥ 0.80; binary outcome), the GEE was conducted using a binomial distribution with logit link so that the obtained β1 estimate represents the average relative odds (i.e., odds ratio [OR]) of adherence across quarters. For HRU (count outcomes) and costs (continuous outcomes), GEEs were conducted using a Poisson distribution with log link so that the obtained β1 estimate represents the average HRU rate ratio (RR) across quarters, and a normal distribution with identity link so that the obtained β1 estimate represents the average mean monthly cost difference across quarters, respectively, along with a non-parametric bootstrap procedure (500 replications) to provide 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and p values for trends.

The comparisons of adherence to APs (i.e., proportion of patients with PDC ≥ 0.80) between the 12 months before and after initiation of PP3M as well as the comparisons of HRU and costs between the 6-month period before the initiation of PP3M and the 12-month period after were based on ORs, RRs, and mean monthly cost differences, all obtained from GEE with the same settings as above, except that an indicator of before versus after PP3M initiation variable (Xafter = 0 or 1) was the explanatory variable:

where β1 is the OR, RR, or mean difference, depending on the link function used. Since patients were their own control, no other covariates were included in the models.

For HRU and cost outcomes, since it is possible that the distribution assumptions (i.e., Poisson for HRU and normal for costs) may not represent the true distribution of the outcomes, non-parametric bootstrap procedures with 500 replications were conducted to provide 95% CIs and p values for RRs and mean monthly cost differences.

All cost outcomes were inflated to 2017 US dollars using the medical care component of the Consumer Price Index [23]. Two-tailed p values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute; Cary, North Carolina).

Results

Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

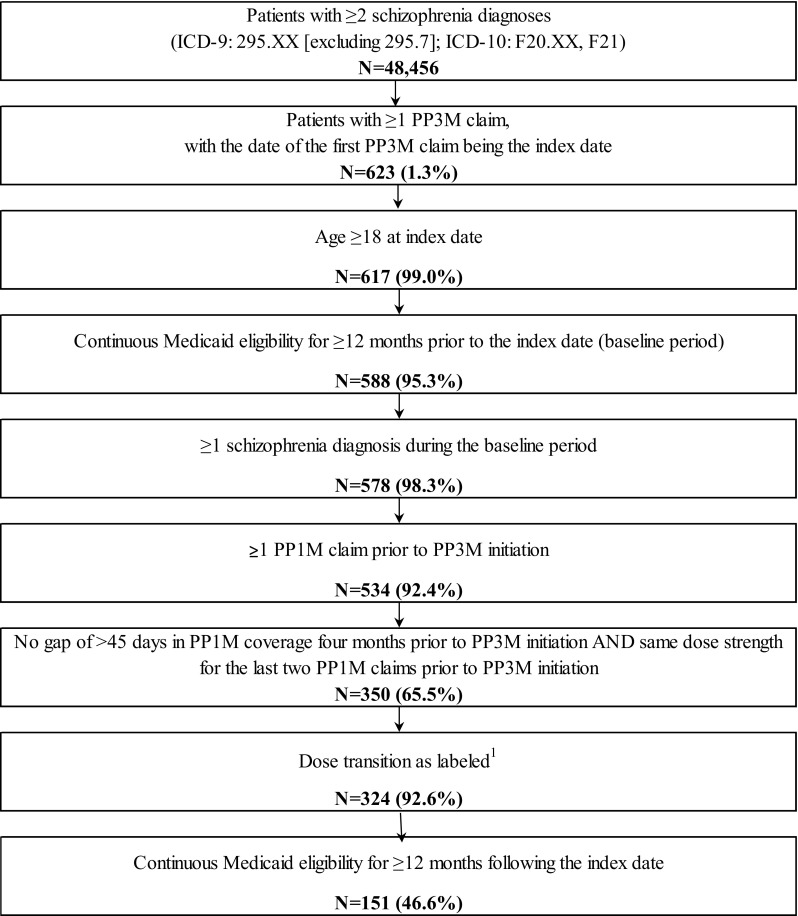

Among 48,456 patients with schizophrenia, 578 patients (1.2%) with ≥ 12 months of eligibility prior to the index date and at least one diagnosis of schizophrenia during this 12-month period were transitioned to PP3M, 324 (52.0%) were adequately treated with PP1M for ≥ 4 months prior to the transition to PP3M, and 151 (46.6%) had ≥ 12 months of continuous Medicaid eligibility following PP3M initiation (Fig. 2). Among the 324 patients adequately transitioning from PP1M to PP3M, mean (SD) age was 41.4 (11.9) years, 117 (36.1%) were females and 205 (63.3%) were white (Table 1). The majority of the sample population, that is 287 patients (88.6%), were from the state of Missouri, and 177 patients (54.6%) were from urban areas (Table 1). A total of 101 patients (31.2%) had capitated coverage, while 67 (20.7%) had dual Medicaid and Medicare coverage. The mean (SD) Quan-CCI score was 0.6 (1.0), and the mean (SD) number of unique mental health diagnoses was 4.3 (3.5) (Table 1). Similar characteristics were observed in all patients transitioning to PP3M (n = 578) and in the subset of patients with ≥ 12 months of continuous insurance eligibility following adequate transition to PP3M (n = 151), except for race and insurance eligibility (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Sample selection flowchart. Data source: Medicaid database: Iowa (2014Q1–2017Q1), Kansas (2014Q1–2017Q1), and Missouri (2014Q1–2017Q1). 1 Correspondence between the dose strength (mg) of the last PP1M claim and the first PP3M claim: 78 mg → 273 mg, 117 mg → 410 mg, 156 mg → 546 mg or 234 mg → 819 mg. ICD-9 International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, ICD-10 International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, PP1M once-monthly paliperidone palmitate, PP3M once-every-3-months paliperidone palmitate

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics evaluated during the 12-month baseline period

| Patients transitioning to PP3M (N = 578) | Patients adequately transitioning from PP1M to PP3M (N = 324) |

Patients adequately transitioned from PP1M to PP3M with ≥ 12 months following PP3M initiation (N = 151) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD [median] | 43.0 ± 12.1 [42.5] | 41.4 ± 11.9 [40.2] | 42.7 ± 11.7 [42.2] |

| Female, n (%) | 203 (35.1) | 117 (36.1) | 53 (35.1) |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| White | 379 (65.6) | 205 (63.3) | 115 (76.2) |

| Black | 169 (29.2) | 97 (29.9) | 24 (15.9) |

| Hispanic | 3 (0.5) | 3 (0.9) | 3 (2.0) |

| Other | 17 (2.9) | 12 (3.7) | 6 (4.0) |

| Unknown | 10 (1.7) | 7 (2.2) | 3 (2.0) |

| State, n (%) | |||

| Missouri | 528 (91.3) | 287 (88.6) | 131 (86.8) |

| Iowa | 48 (8.3) | 36 (11.1) | 19 (12.6) |

| Kansas | 2 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.7) |

| Region characteristics, n (%) | |||

| Urban | 333 (57.6) | 177 (54.6) | 77 (51.0) |

| Suburban | 136 (23.5) | 83 (25.6) | 41 (27.2) |

| Rural | 109 (18.9) | 64 (19.8) | 33 (21.9) |

| Insurance eligibility, n (%) | |||

| Capitated or dual coverage | 353 (61.1) | 150 (46.3) | 69 (45.7) |

| Capitated | 177 (30.6) | 101 (31.2) | 45 (29.8) |

| Dual coverage | 246 (42.6) | 67 (20.7) | 37 (24.5) |

| Quan-CCI, mean ± SD [median] | 0.7 ± 1.1 [0.0] | 0.6 ± 1.0 [0.0] | 0.7 ± 1.0 [0.0] |

| Number of unique mental health diagnoses, mean ± SD [median] | 4.2 ± 3.7 [3.0] | 4.3 ± 3.5 [3.0] | 4.3 ± 3.4 [3.0] |

| Type of schizophrenia disordera, n (%) | |||

| Simple type schizophrenia (295.0) | 5 (0.9) | 2 (0.6) | 2 (1.3) |

| Disorganized type schizophrenia (295.1 or F20.1) | 16 (2.8) | 12 (3.7) | 8 (5.3) |

| Catatonic type schizophrenia (295.2 or F20.2) | 2 (0.3) | 2 (0.6) | 1 (0.7) |

| Paranoid type schizophrenia (295.3 or F20.0) | 270 (46.7) | 146 (45.1) | 73 (48.3) |

| Schizophreniform disorder (295.4 or F20.81) | 16 (2.8) | 8 (2.5) | 6 (4.0) |

| Latent schizophrenia (295.5 or F21) | 4 (0.7) | 2 (0.6) | 1 (0.7) |

| Schizophrenic disorder, residual type (295.6 or F20.5) | 16 (2.8) | 7 (2.2) | 3 (2.0) |

| Schizoaffective disorder (295.7 or F25.0 or F25.1) | 284 (49.1) | 171 (52.8) | 84 (55.6) |

| Undifferentiated schizophrenia (F20.3) | 19 (3.3) | 11 (3.4) | 6 (4.0) |

| Other specified types of schizophrenia (295.8 or F20.89) | 15 (2.6) | 6 (1.9) | 4 (2.6) |

| Unspecified schizophrenia (295.9 or F20.9) | 252 (43.6) | 140 (43.2) | 65 (43.0) |

| Quarter of index date, n (%) | |||

| May–June 2015 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| July–September 2015 | 52 (9.0) | 40 (12.3) | 37 (24.5) |

| October–December 2015 | 87 (15.1) | 64 (19.8) | 61 (40.4) |

| January–March 2016 | 143 (24.7) | 53 (16.4) | 51 (33.8) |

| April–June 2016 | 82 (14.2) | 60 (18.5) | 2 (1.3) |

| July–September 2016 | 56 (9.7) | 41 (12.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| October–December 2016 | 41 (7.1) | 32 (9.9) | 0 (0.0) |

| January–March 2017 | 117 (20.2) | 34 (10.5) | 0 (0.0) |

CCI Charlson Comorbidity Index, ICD-9 International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, ICD-10 International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, PP1M once-monthly paliperidone palmitate, PP3M once-every-3-months paliperidone palmitate, SD standard deviation

aTypes of schizophrenia disorder were identified based on the first 4 digits of the ICD-9/ICD-10 codes for schizophrenia diagnosis. Note that types of schizophrenia disorder are not mutually exclusive

Quarterly Adherence, Healthcare Resource Utilization (HRU), and Costs during the Baseline Period

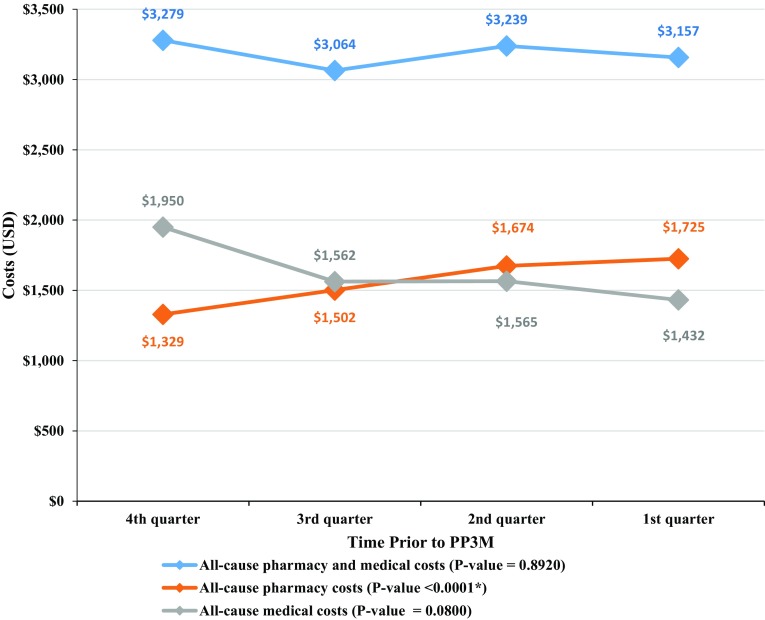

During the four quarters pre-transition to PP3M, the proportion of patients adherent to APs (i.e., PDC ≥ 0.80) significantly increased by 17.8 percentage points (from 66.8 to 84.6%, p < 0.0001). The changes in monthly all-cause pharmacy and medical costs are displayed in Fig. 3. Over the four quarters pre-transition to PP3M, a significant increase in pharmacy costs (from US$1329 to US$1725, p < 0.0001) was observed. This increase was offset by numerically decreasing medical costs (from US$1950 to US$1432, p = 0.0800), resulting in similar total healthcare costs (from US$3279 to US$3157, p = 0.8920). The decrease in medical costs was driven by a decrease in monthly inpatient costs, which were reduced by 50.5% compared to the fourth quarter prior to PP3M transition (from US$469 to US$232, p = 0.0240). The monthly number of emergency room visits decreased by 30.0% (from 0.10 to 0.07, p = 0.0360) from the fourth to the first quarter prior to PP3M transition.

Fig. 3.

Monthly healthcare costs per patient evaluated during the four quarters prior to PP3M transition. P values were obtained using a non-parametric bootstrap procedure with 500 replicates. *p value < 0.05. PP3M once-every-3-months paliperidone palmitate, USD US dollars

PP3M Treatment Patterns

Patterns of treatment with PP3M are described in Table 2. Patients were observed on average (SD) for 11.1 (5.7) months following transition to PP3M, with 151 (46.6%) of patients having ≥ 12 months of observation. The mean (SD) time between the last PP1M dose and the first PP3M dose was 26.6 (12.2) days. A total of 176 patients (54.3%) started treatment on the highest recommended dose (819 mg) and 102 patients (31.5%) started on the second highest dose (546 mg). More than 95% of patients remained on the same dose for subsequent injections. Among patients with ≥ 12 months of follow-up (n = 151), 91 (60.3%) had a PDC of ≥ 0.80. Among patients with at least two PP3M claims (n = 247), 223 (90.3%) had an MPR of ≥ 0.80.

Table 2.

PP3M treatment patterns

| Patients adequately transitioning from PP1M to PP3M (N = 324) |

|

|---|---|

| Observation period, months, mean ± SD [median] | 11.1 ± 5.7 [11.5] |

| Patients with ≥ 6 months of observation period, n (%) | 248 (76.5) |

| Patients with ≥ 12 months of observation period, n (%) | 151 (46.6) |

| Duration of continuous PP3M therapya, days, mean ± SD [median] | 243.8 ± 162.3 [197.5] |

| Number of PP3M claims, mean ± SD [median] | 3.2 ± 2.0 [3.0] |

| Distribution of the number of PP3M claims, n (%) | |

| 1 | 77 (23.8) |

| 2 | 71 (21.9) |

| 3 | 51 (15.7) |

| 4 or more | 125 (38.6) |

| Dosing patterns | |

| First dose | |

| Patients with a first dose, n (%) | 324 (100.0) |

| Days since last PP1M dose, mean ± SD [median] | 26.6 ± 12.2 [28.0] |

| Dose strength (mg), n (%) | |

| 273 | 2 (0.6) |

| 410 | 44 (13.6) |

| 546 | 102 (31.5) |

| 819 | 176 (54.3) |

| Second dose | |

| Patients with ≥ 4 months of follow-up after first dose, n (%) | 275 (84.9) |

| Patients with a second dose, n (%) | 240 (87.3) |

| Days since last PP3M dose, mean ± SD [median] | 102.2 ± 46.3 [90.0] |

| Dose strength (mg), n (%) | |

| 273 | 1 (0.4) |

| 410 | 28 (11.7) |

| 546 | 82 (34.2) |

| 819 | 129 (53.8) |

| Third dose | |

| Patients with ≥ 4 months of follow-up after second dose, n (%) | 201 (62.0) |

| Patients with a third dose, n (%) | 169 (84.1) |

| Days since last PP3M dose, mean ± SD [median] | 90.6 ± 22.0 [85.0] |

| Dose strength (mg), n (%) | |

| 273 | 1 (0.6) |

| 410 | 18 (10.7) |

| 546 | 57 (33.7) |

| 819 | 93 (55.0) |

| Subsequent doses | |

| Patients with ≥ 4 months of follow-up after third dose, n (%) | 138 (42.6) |

| Patients with a subsequent dose, n (%) | 125 (90.6) |

| Days between subsequent dosesb, mean ± SD [median] | 94. 1 ± 31.7 [86.3] |

| Adherence to PP3M | |

| Patients with ≥ 2 PP3M claims, n (%) | 247 (76.2) |

| MPRc, mean ± SD [median] | 0.94 ± 0.14 [1.00] |

| MPRc ≥ 0.80, n (%) | 223 (90.3) |

| Patients with ≥ 12 months of observation period, n (%) | 151 (46.6) |

| PDC at 12 monthsd, mean ± SD [median] | 0.79 ± 0.24 [0.92] |

| PDC ≥ 0.80, n (%) | 91 (60.3) |

MPR medication possession ratio, PDC proportion of days covered, PP1M once-monthly paliperidone palmitate, PP3M once-every-3-months paliperidone palmitate, SD standard deviation

aContinuous PP3M therapy was defined as having a gap of no more than 45 days between the end of supply of a PP3M claim and the start of a new PP3M claim, starting from the index date

bAmong patients with more than three PP3M claims and at least 4 months of follow-up between claims

cMPR was calculated among patients with at least two claims of PP3M

dPDC was calculated as the sum of the number of unique days during which the patient had PP3M, divided by a fixed time interval

Comparison of Adherence, HRU, and Costs Before and After Transitioning to PP3M

Among patients with ≥ 12 months of observation post-PP3M transition (n = 151), the proportion of patients adherent to APs numerically increased from 66.2% in the 12-month baseline period to 70.2% in the first 12 months following PP3M transition (OR = 1.20, p = 0.3758), although the increase was not significant.

Among the same sample of patients, total monthly healthcare costs remained similar during the 6 months pre- and the 12 months post-PP3M transition (US$3371 vs. US$3456, p = 0.7000; Fig. 4a). Similarly, no significant differences were observed in monthly medical costs (US$1565 vs. US$1586, p = 0.9040) and pharmacy costs (US$1805 vs. US$1870, p = 0.2960; Fig. 4a).

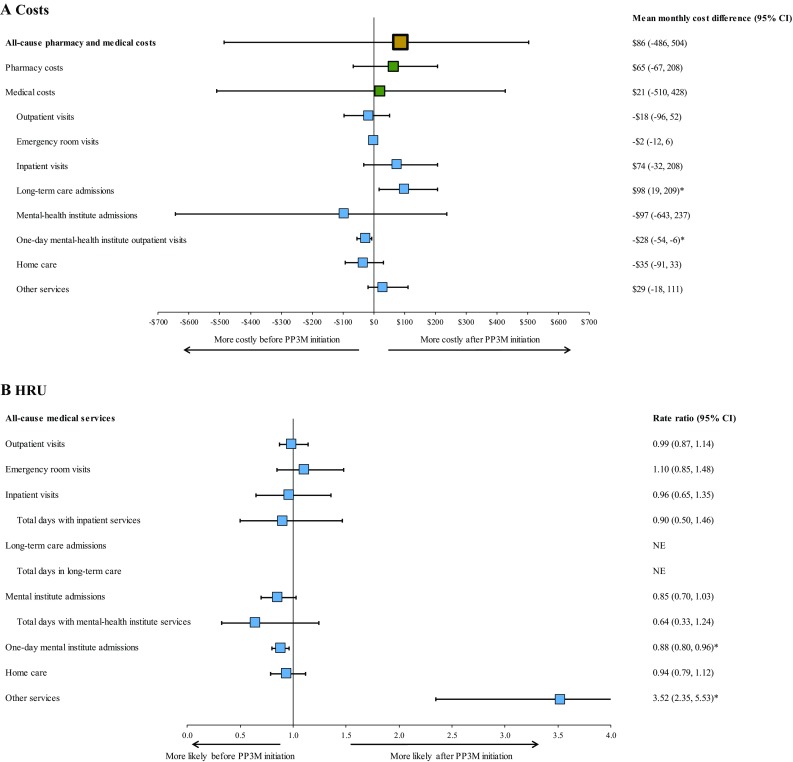

Fig. 4.

Comparison of monthly HRU and costs 6 months before and 12 months after transition to PP3M. P values were obtained using a non-parametric bootstrap procedure with 500 replicates. *p value < 0.05. CI confidence interval, HRU healthcare resource utilization, NE not evaluable, PP3M once-every-3-months paliperidone palmitate

Likewise, the mean monthly number of outpatient visits (1.18 vs. 1.16, p = 0.9000), emergency room visits (0.09 vs. 0.09, p = 0.4400), inpatient visits (0.08 vs. 0.07, p = 0.7760), mental institute admissions (0.47 vs. 0.40, p = 0.1080), and days with home care services (1.74 vs. 1.63, p = 0.4760) did not change significantly. However, the mean monthly number of 1-day mental-health institute visits decreased by 12% during the 12 months post-PP3M transition compared to the 6 months pre-transition (1.71 vs. 1.51, p = 0.0080). This resulted in a decrease of US$28 in monthly 1-day mental-health institute visit costs (US$260 vs. US$232, p = 0.0120) over the same period (Fig. 4a). Conversely, the mean monthly number of days with other services increased during the 12 months post-PP3M transition compared to the 6 months pre-transition (0.06 vs. 0.21, p < 0.0001; Fig. 4b). This increase was mostly driven by an increase in the mean monthly number of days with services received in an independent laboratory (0.003 vs. 0.10, p < 0.0001) and monthly number of visits to Federally Qualified Health Centers (0.007 vs. 0.05, p < 0.0001). While a significant increase in long-term care admission costs was observed following PP3M transition (US$1 vs. US$99, p = 0.0280), the number of events was not sufficient to assess the increase in the number of admissions.

Discussion

Among 324 patients adequately transitioning from PP1M to PP3M, results showed that adherence to APs significantly improved over the four quarters preceding the transition to PP3M. The increase in pharmacy costs over the four quarters pre-PP3M transition was offset by decreasing medical costs, driven by a decrease in inpatient costs. A decrease in the monthly number of emergency room visits was also observed over the four quarters preceding the transition to PP3M. Adherence to APs, HRU, and costs remained generally similar pre- and post-PP3M initiation.

A majority of patients in the current study were from the state of Missouri, while only two patients were from the state of Kansas. This is likely due to the fact that APs are not on the Medicaid preferred drug list (PDL) for mental health and substance abuse in the state of Kansas [24, 25] and patients’ access to them requires a prior authorization, while PP3M appears on the PDLs of Iowa [26] and Missouri [27].

A recent study by Joshi et al. [22] assessed patients who transitioned from PP1M to PP3M and examined patients’ baseline characteristics and treatment patterns over a period of 1 year before the transition to PP3M. Patients in this study had similar characteristics as the patients in our sample (e.g., 33.9% were females). They showed similar results in baseline quarters preceding PP3M initiation, with an increase in the proportion of patients with a PDC of ≥ 0.80 from 71.3% at the fourth quarter to 82.3% at the first quarter prior to PP3M initiation (compared to an increase from 66.8 to 84.6% in our study). Similar to the findings of the current study, Joshi et al. [22] demonstrated in their study a decrease in the monthly number of emergency room visits in quarters preceding PP3M transition (from 0.08 to 0.06 per month). This finding and findings from the current study are consistent with the requirement from the prescribing guidelines that patients be adequately treated with PP1M prior to the transition to PP3M. In phase 3 trials, low symptom severity, consistent with low utilization of emergency room and inpatient services, was part of the requirements to be considered adequately treated [20, 21]. Adherence to PP3M was also similar to the current study, as 95.6% of patients had an MPR of ≥ 0.80, and 81.7% of patients had a 6-month PDC of ≥ 0.80.

The algorithm used in the current study and in Joshi et al. [22] to define adequate treatment with PP1M prior to transition to PP3M has been developed to mimic the PP3M clinical trial protocol [20, 21]. However, treating healthcare providers may have clinical reasons for not conforming with the guidelines in certain circumstances where individualized patient care is required. Hence, observed findings may differ from the prescribing guidelines in the real-world practice of psychiatry. It is also possible that some of the initial claims for PP1M were not captured in the data (e.g., samples). Nevertheless, findings are consistent across both studies, as > 50% of patients transitioned from PP1M to PP3M as per prescribing guidelines [22].

Schizophrenia therapy with OAAs has been compared to LAI therapy (including PP1M) in several studies looking at different populations of patients as well as different outcomes such as treatment adherence, HRU, and costs. LAI therapy has been shown to improve adherence rate (i.e., PDC ≥ 0.80) in patients with schizophrenia by more than 8 percentage points compared to OAA therapy (p < 0.001), while reducing the likelihood of discontinuation, with patients on OAAs having a 20% higher chance of discontinuation than those on LAIs (p < 0.001) [28]. Within the population of patients who had recently been diagnosed with schizophrenia, the improvement in adherence rate to PP1M was more than 7 percentage points higher compared to OAA therapy (p < 0.0001) [6]. PP1M treatment was also shown in previous studies to be associated with lower medical costs, offsetting higher pharmacy costs and resulting in similar total healthcare costs, compared to OAAs [11–13, 15]. Likewise, PP1M was found to be associated with a significant reduction in all-cause institutional costs, risk of hospital readmission, and number of emergency room visits compared to OAAs following index hospital discharge [14].

In the current study, adherence to APs, HRU, and costs remained similar pre- and post-PP3M transition, suggesting that PP3M has no impact on monthly healthcare costs for patients adequately treated with PP1M. Particularly, pharmacy costs remained similar pre- and post-PP3M initiation, which is expected since PP3M unit price is three times the price of PP1M. As an example, the current wholesale acquisition cost of PP1M 234 mg is US$2501.69, while the current wholesale acquisition for PP3M 819 mg is US$7505.07 [29]. The choice of the 6-month period pre-PP3M initiation as a comparator to the 12-month period post-PP3M initiation was driven by the fact that HRU and costs during this period were most likely evaluated during a period of stable use of PP1M. If the 12-month period pre-initiation had been chosen instead, HRU and costs may have been captured during a period where patients were not yet initiated and stabilized on PP1M.

Although the literature available on the comparison of PP1M versus OAAs and the findings of the current study could suggest that conclusions related to adherence, HRU, and costs could hold if the authors were to compare OAAs and PP3M, there is a need for a direct comparison of OAAs and PP3M to confirm this statement.

The findings of the current study could be of particular interest to insurance payers and policy makers, since results show that the transition to PP3M does not increase healthcare costs. It is also useful to clinicians, since the transition to PP3M does not impact adherence or HRU, while having the benefit of a more flexible dosing schedule. This could potentially lead to an increased quality of life for these patients. The current study is subject to limitations inherent to the use of claims databases. The Medicaid data used in this study covered only three states and may not be representative of the US population, including other states or patients not covered by Medicaid. Moreover, the definition of adherence based on information in claims data does not necessarily reflect actual medication use by patients; therefore, results in this study may have overestimated adherence. Similar to other claims data, the data used in this study may be subject to billing inaccuracies and missing data. Furthermore, costs were based on the Medicaid payers’ perspectives and reflected amounts paid by state Medicaid programs; therefore, out-of-pocket and direct non-medical costs from the patient’s perspective were not available. In addition, these amounts do not take into account discounts or rebates; therefore, pharmacy costs may have been overestimated. Finally, the pre-post study design used to compare adherence, HRU, and costs before and after PP3M initiation imposes a lack of external validation on the study findings as each individual is his/her own control. In this type of design, time-dependent factors that may not be observable in administrative claims data could have impacted the results, but could not be taken into account.

Conclusions

In this Medicaid population of patients with schizophrenia, adherence to APs, HRU, and spending remained similar before and after PP3M initiation. These findings suggest that PP3M has no impact on monthly healthcare costs for patients adequately treated with PP1M, with the added flexibility of once-every-3-months dosing.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the conception and design of the study, the analysis and interpretation of the data, the drafting of the paper, and revising it critically for intellectual content. All authors provided their final approval of the version to be published. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work presented in this manuscript.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

PL, BE, MHL, DP, and HR are employees of Analysis Group, Inc., a consulting company that has received research grants from Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, to conduct this study. KJ, AEK, and NT are employees of Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC.

Data availability

Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used pursuant to a data use agreement. The data are available through requests made directly to individual states, subject to the state’s requirements for data access.

References

- 1.National Institute of Mental Health. Schizophrenia. 2016. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/schizophrenia/index.shtml. Accessed 11 June 2018.

- 2.Chong HY, Teoh SL, Wu DB-C, Kotirum S, Chiou C-F, Chaiyakunapruk N. Global economic burden of schizophrenia: a systematic review. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;12:357–373. doi: 10.2147/ndt.s96649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu EQ, Birnbaum HG, Shi L, Ball DE, Kessler RC, Moulis M, et al. The economic burden of schizophrenia in the United States in 2002. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(9):1122–1129. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v66n0906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cloutier M, Aigbogun MS, Guerin A, Nitulescu R, Ramanakumar AV, Kamat SA, et al. The economic burden of schizophrenia in the United States in 2013. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(6):764–771. doi: 10.4088/jcp.15m10278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, Swartz MS, Rosenheck RA, Perkins DO, et al. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. N Engl J Med. 2005;2005(353):1209–1223. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pilon D, Muser E, Lefebvre P, Kamstra R, Emond B, Joshi K. Adherence, healthcare resource utilization and Medicaid spending associated with once-monthly paliperidone palmitate versus oral atypical antipsychotic treatment among adults recently diagnosed with schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):207. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1358-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Birnbaum M, Sharif Z. Medication adherence in schizophrenia: patient perspectives and the clinical utility of paliperidone ER. Patient Prefer Adher. 2008;2:233. doi: 10.2147/ppa.s3346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marcus SC, Zummo J, Pettit AR, Stoddard J, Doshi JA. Antipsychotic adherence and rehospitalization in schizophrenia patients receiving oral versus long-acting injectable antipsychotics following hospital discharge. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2015;21(9):754–769. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2015.21.9.754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Janssen Pharmaceuticals IT, NJ. INVEGA SUSTENNA® (paliperidone palmitate): US prescribing information. https://www.invegasustenna.com/important-product-information. Accessed 11 June 2018.

- 10.Alphs L, Benson C, Cheshire-Kinney K, Lindenmayer J-P, Mao L, Rodriguez SC, et al. Real-world outcomes of paliperidone palmitate compared to daily oral antipsychotic therapy in schizophrenia: a randomized, open-label, review board-blinded 15-month study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(5):554–561. doi: 10.4088/JCP.14m09584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pesa JA, Doshi D, Wang L, Yuce H, Baser O. Health care resource utilization and costs of California Medicaid patients with schizophrenia treated with paliperidone palmitate once monthly or atypical oral antipsychotic treatment. Curr Med Res Opin. 2017;33(4):723–731. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2016.1278202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baser O, Xie L, Pesa J, Durkin M. Healthcare utilization and costs of veterans health administration patients with schizophrenia treated with paliperidone palmitate long-acting injection or oral atypical antipsychotics. J Med Econ. 2015;18(5):357–365. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2014.1001514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joshi K, Lafeuille M-H, Kamstra R, Tiggelaar S, Lefebvre P, Kim E, et al. Real-world adherence and economic outcomes associated with paliperidone palmitate versus oral atypical antipsychotics in schizophrenia patients with substance-related disorders using Medicaid benefits. J Comp Eff Res. 2017;7(2):121–133. doi: 10.2217/cer-2017-0043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lafeuille M-H, Grittner AM, Fortier J, Muser E, Fasteneau J, Duh MS, et al. Comparison of rehospitalization rates and associated costs among patients with schizophrenia receiving paliperidone palmitate or oral antipsychotics. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2015;72(5):378–389. doi: 10.2146/ajhp140219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xiao Y, Muser E, Lafeuille M-H, Pesa J, Fastenau J, Duh MS, et al. Impact of paliperidone palmitate versus oral atypical antipsychotics on healthcare outcomes in schizophrenia patients. J Comp Eff Res. 2015;4(6):579–592. doi: 10.2217/cer.15.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Viala A, Cornic F, Vacheron M-N. Treatment adherence with early prescription of long-acting injectable antipsychotics in recent-onset schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Res Treat. 2012;2012:368687. doi: 10.1155/2012/368687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Potkin SG, Weiden PJ, Loebel AD, Warrington LE, Watsky EJ, Siu CO. Remission in schizophrenia: 196-week, double-blind treatment with ziprasidone vs. haloperidol. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009;12(9):1233–1248. doi: 10.1017/S1461145709000352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alonso J, Croudace T, Brown J, Gasquet I, Knapp MR, Suárez D, et al. Health-related quality of life (HRQL) and continuous antipsychotic treatment: 3-year results from the Schizophrenia Health Outcomes (SOHO) study. Value Health. 2009;12(4):536–543. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2008.00495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Janssen Pharmaceuticals IT, NJ. INVEGA TRINZA® (paliperidone palmitate): US prescribing information. http://www.janssenlabels.com/package-insert/product-monograph/prescribing-information/INVEGA+TRINZA-pi.pdf. Accessed 11 June 2018.

- 20.Berwaerts J, Liu Y, Gopal S, Nuamah I, Xu H, Savitz A, et al. Efficacy and safety of the 3-month formulation of paliperidone palmitate vs placebo for relapse prevention of schizophrenia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(8):830–839. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Savitz Adam J., Xu Haiyan, Gopal Srihari, Nuamah Isaac, Ravenstijn Paulien, Janik Adam, Schotte Alain, Hough David, Fleischhacker Wolfgang W. Efficacy and Safety of Paliperidone Palmitate 3-Month Formulation for Patients with Schizophrenia: A Randomized, Multicenter, Double-Blind, Noninferiority Study. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;19(7):pyw018. doi: 10.1093/ijnp/pyw018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joshi K, Lafeuille M-H, Brown B, Wynant W, Emond B, Lefebvre P, et al. Baseline characteristics and treatment patterns of patients with schizophrenia initiated on once-every-three-months paliperidone palmitate in a real-world setting. Curr Med Res Opin. 2017;33(10):1763–1772. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2017.1359516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Statistics BoL. Consumer price index (CPI) databases.

- 24.Environment KDoHa. PREFERRED DRUG LIST. http://www.kdheks.gov/hcf/pharmacy/download/PDLList.pdf. Accessed 11 June 2018.

- 25.Legistlatures NCoS. Medicaid preferred drug lists (PDLs) for mental health and substance abuse. 2018. http://www.ncsl.org/documents/health/pdl-2-2012.pdf. Accessed 11 June 2018.

- 26.Program DoHSIM. Preferred drug list. 2018. http://www.iowamedicaidpdl.com/sites/default/files/ghs-files/current-pdl/2018-04-26/ia-web-pdl2018junefinal.pdf. Accessed 11 June 2018.

- 27.Services MDoS. Preferred drug list recommendations. 2018. https://dss.mo.gov/mhd/cs/pharmacy/pdf/pdl-recommendations.pdf. Accessed 11 June 2018.

- 28.Greene M, Yan T, Chang E, Hartry A, Touya M, Broder MS. Medication adherence and discontinuation of long-acting injectable versus oral antipsychotics in patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. J Med Econ. 2017;21:1–8. doi: 10.1080/13696998.2017.1379412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Health IW. Red book. http://truvenhealth.com/Products/Micromedex/Product-Suites/Clinical-Knowledge/REDBOOK. Accessed 11 June 2018.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used pursuant to a data use agreement. The data are available through requests made directly to individual states, subject to the state’s requirements for data access.