Abstract

Background

Guidelines recommend empirical vancomycin or linezolid for patients with suspected pneumonia at risk for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Unneeded vancomycin or linezolid use may unnecessarily alter host flora and expose patients to toxicity. We therefore sought to determine if rapid testing for MRSA in BAL can safely decrease use of vancomycin or linezolid for suspected MRSA pneumonia.

Methods

Operating characteristics of the assay were initially validated against culture on residual BAL. A prospective, unblinded, randomized clinical trial to assess the effect of antibiotic management made on the basis of rapid diagnostic testing (RDT) compared with usual care was subsequently conducted, with primary outcome of duration of vancomycin or linezolid administration. Secondary end points focused on safety.

Results

Sensitivity of RPCR was 95.7%, with a negative likelihood ratio of 0.04 for MRSA. The clinical trial randomized 45 patients: 22 to antibiotic management made on the basis of RDT and 23 to usual care. Duration of vancomycin or linezolid administration was significantly reduced in the intervention group (32 h [interquartile range, 22-48] vs 72 h [interquartile range, 50-113], P < .001). Proportions with complications and length of stay trended lower in the intervention group. Hospital mortality was 13.6% in the intervention group and 39.1% for usual care (95% CI of difference, –3.3 to 50.3, P = .06). Standardized mortality ratio was 0.48 for the intervention group and 1.18 for usual care.

Conclusions

A highly sensitive BAL RDT for MRSA significantly reduced use of vancomycin and linezolid in ventilated patients with suspected pneumonia. Management made on the basis of RDT had no adverse effects, with a trend to lower hospital mortality.

Trial Registry

ClinicalTrials.gov; No. NCT02660554; URL: www.clinicaltrials.gov.

Key Words: antibiotic stewardship, diagnostic testing, methicillin-resistance, polymerase chain reaction, Staphylococcus aureus

Abbreviations: APACHE, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; ATS, American Thoracic Society; CFU, colony-forming unit; IDSA, Infectious Diseases Society of America; IQR, interquartile range; MICU, medical ICU; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; MSSA, methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus; NLR, negative likelihood ratio; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; RCT, randomized, controlled trial; RPCR, rapid polymerase chain reaction

Staphylococcus aureus is a serious cause of community-acquired and nosocomial pneumonia.1, 2 American Thoracic Society (ATS)/Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and international guidelines for nosocomial pneumonia recommend empiric administration of vancomycin or linezolid for patients with suspected pneumonia and risk factors for methicillin-resistant S aureus (MRSA) pneumonia.3, 4, 5 Unfortunately, clinical risk factors for MRSA pneumonia do not reliably discriminate between MRSA and other bacterial causes of pneumonia.6, 7, 8, 9 Although the incidence of culture-positive MRSA pneumonia has clearly not increased and may even have decreased in recent years,10, 11, 12 empiric use of antibiotics specifically for suspected MRSA pneumonia has increased substantially since the introduction of the ATS/IDSA guidelines in 2005.10, 13, 14, 15, 16 Indiscriminate use of broad-spectrum antibiotics accelerates the problem of increasing antibiotic resistance, in addition to unnecessarily exposing patients to associated adverse side effects of these drugs.17, 18, 19 Even short courses of anti-MRSA agents may alter host flora and have toxicity, particularly vancomycin.19

Rapid, nonculture-based methods to identify drug-resistant pathogens and guide antibiotic choices in patients with suspected pneumonia are critical to improve antibiotic stewardship. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is one technology that can rapidly determine presence of S aureus and identify methicillin resistance by detection of the mecA gene. Rapid automated PCR (RPCR) assays are used clinically for detection of S aureus in skin and soft tissue and nasopharyngeal samples. Use of RPCR in BAL has been shown to detect both MRSA and methicillin-sensitive S aureus (MSSA) with a high negative predictive value.20, 21, 22 Retrospective analyses from two academic medical centers estimated that vancomycin and linezolid utilization in mechanically ventilated patients with pneumonia could be decreased significantly by using RPCR on BAL23, 24; however, retrospective analyses cannot accurately predict actual clinical response to diagnostic testing results, particularly if safety is a concern.

We therefore designed a pilot prospective randomized clinical trial (RCT) of antibiotic management on the basis of RPCR results to safely decrease anti-MRSA antibiotic use compared with usual therapy in mechanically ventilated patients in the medical ICU (MICU) with suspected MRSA pneumonia.

Methods

To safely perform the RCT, establishing the operating characteristics for off-label use of the commercially available RPCR assay (MRSA/SA SSTI kit on the Cepheid GeneXpert platform) on BAL was the critical first step.

RPCR Assay Validation

We collected consecutive residual BAL samples from intubated patients with suspected pneumonia at a single tertiary care academic medical center from June 2015 to April 2016; all samples were obtained as part of usual clinical care. Because of low frequency of S aureus pneumonia in the prospective specimen collection, we enriched the collection by additional RPCR testing on subsequent MRSA culture-positive BAL samples to further evaluate sensitivity and specificity. Details of BAL collection and RPCR performance are included in e-Appendix 1. The RPCR assay validation phase of the study was approved by the institutional review board of Northwestern University with a waiver of consent.

The RPCR assay was assessed against quantitative culture using a calibrated loop method; the lowest level of detection of MRSA on culture was 102 colony forming units (CFUs)/mL. A positive culture clinically was defined as MRSA growth >104 CFU/mL and possibly positive as 103 CFU/mL. We computed sensitivity, specificity, positive likelihood ratio, and negative likelihood ratio (NLR) by standard equations. Positive predictive value and negative predictive value could not be accurately calculated because of the additional, nonconsecutive samples used to enrich the sample.

RCT

We prospectively enrolled mechanically ventilated patients in the MICU empirically treated with anti-MRSA antibiotics for suspected pneumonia with BAL samples obtained from May 2016 to January 2017. An active antibiotic stewardship program focused on reduction of anti-MRSA therapy was already in place and continued throughout the study. Primary inclusion criterion was commitment by the primary attending intensivist to continue anti-MRSA treatment at least until cultures results were available. Exclusion criteria included neutropenic fever, chronic airway infection such as cystic fibrosis, suspicion for extrapulmonary MRSA infection, patient/surrogate refusal, treating physician refusal to narrow antibiotics on the basis of RPCR, or > 48 hours of anti-MRSA therapy before enrollment. All patients with suspected MRSA pneumonia, including community-acquired pneumonia, were included. Various risk factors for MRSA in the different categories of pneumonia are listed in e-Appendix 1.8, 25 Institutional review board approval was obtained before starting enrollment and consent from all patients or surrogates was obtained before any RPCR testing.

Patients were randomized 1:1 to anti-MRSA antibiotic management on the basis of RPCR test results or to continue with usual care. Fifty envelopes with an even number of each allocation were thoroughly shuffled after sealing and then numbered before any enrollment by one of the investigators (B. D. L.). Randomization was subsequently performed by opening sequentially numbered sealed envelopes.

The study was open label. In the experimental group, RPCR results were paged to a primary team physician immediately after test completion because the result was not displayed in the electronic medical record system. Mean time from arrival in the microbiology laboratory to results of RPCR testing was 68 min. Vancomycin or linezolid was discontinued as soon as negative RPCR test results were available in experimental group.

Primary outcome was duration of anti-MRSA agent administration for the initial suspected MRSA pneumonia episode. On the basis of prior data, the prevalence of MRSA pneumonia is approximately 5.5% in our MICU. With a conservative estimate that all subjects would receive three doses of vancomycin or linezolid before randomization, and that up to 94% of anti-MRSA therapy could be discontinued at 72 h on the basis of negative cultures in the usual care arm, we calculated that RPCR could reduce antibiotic exposure by 33.6%. On the basis of these estimates, power analysis suggested that 22 subjects in each group were needed to detect a clinically relevant difference in antibiotic days between the intervention and control groups, with 80% power (β = 0.20) and two-sided α = 0.05.

Secondary end points focused on safety within 28 days following randomization and included need for additional anti-MRSA treatment within 28 days, acute renal failure (defined as > 0.5 g/dL increase in serum creatinine from baseline), thrombocytopenia (new decrease in platelet count to < 100,000/mL), differences in serial acute physiologic score component of the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) IV score and Sequential Organ Failure Assessment scores for the 14 days subsequent to randomization, new hospital-acquired infections, hospital length of stay, and in-hospital mortality.26, 27 Anti-MRSA agent administration duration was defined as the length of time vancomycin and/or linezolid was given plus one additional dosing interval. Dosing intervals were independently determined by the on-staff MICU pharmacist on the basis of the patient’s renal function at the time of medication administration. The additional dosing interval was included in duration of treatment to best capture how long each patient was receiving therapeutic anti-MRSA therapy, given variable dosing intervals for vancomycin. Total 28-day anti-MRSA treatment was defined as the cumulative time of receiving any vancomycin or linezolid received during the 28-day study period.

All analyses were performed using SPSS (version 22.0.0.0, IBM Corp.). Categorical data were compared using Pearson χ2 test, and continuous data by Mann-Whitney U test. Median values with interquartile ranges (IQR) are presented for antibiotic duration because data were not normally distributed, as assessed by Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests. Severity of illness scores were compared to assess inter- and intragroup variability for each day of collection using generalized estimating equations.

Results

RPCR Assay Validation Phase

A total of 247 BAL samples were collected and tested using RPCR. Eight samples (3.2%) initially had an indeterminate result. On repeat, all yielded an unequivocal result.

MRSA grew in culture in 23 samples (Table 1). RPCR detected MRSA in 26 of 247 BAL samples. RPCR correlated with positive MRSA cultures in 22 of 26 (84.1%) samples: 4 (1.6%) false positives and 1 (0.4%) false negative compared with culture. The one false-negative MRSA RPCR was a BAL with only 100 CFU/mL growth of MRSA, which was below our clinical threshold for a positive BAL and not treated clinically. All four patients with false-positive RPCR for MRSA grew MSSA with a high bacterial load from BAL or tracheostomy site during their hospital admission. Results of the RPCR for MSSA are in Table 2, with additional information in e-Appendix 1.

Table 1.

RPCR Test Operating Characteristics for MRSA

| MRSA | Growth in Culture |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Total | |

| PCR positive | |||

| Yes | 22 | 4 | 26 |

| No | 1 | 220 | 221 |

| Total | 23 | 224 | 247 |

MRSA = methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; PCR = polymerase chain reaction; RPCR = rapid polymerase chain reaction.

Table 2.

RPCR Test Operating Characteristics for MSSA

| MSSA | Growth in Culture |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Total | |

| PCR positive | |||

| Yes | 24 | 20 | 44 |

| No | 1 | 173 | 174 |

| Total | 25 | 193 | 218 |

MSSA = methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus. See Table 1 legend for expansion of other abbreviations.

Sensitivity and specificity of RPCR are 95.7% and 98.2%, respectively, for the identification of MRSA above the clinical diagnostic threshold. Positive likelihood ratio and NLR were 53.5 and 0.04 for MRSA. The NLR result was considered safe for a clinical trial of anti-MRSA antibiotic discontinuation on the basis of the RPCR results.

RCT

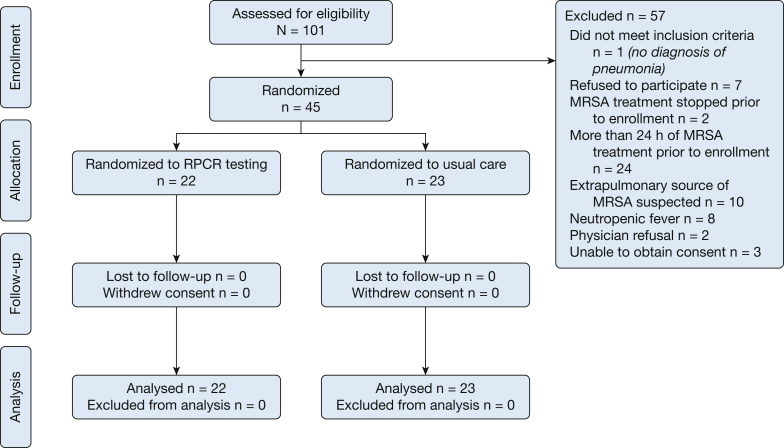

A total of 45 patients were randomized: 22 to antibiotic management on the basis of RPCR result and 23 to continued usual care (Fig 1). The primary attending refused study enrollment for two patients, whereas 10 patients were excluded because of a suspected extrapulmonary MRSA infection requiring ongoing anti-MRSA treatment regardless of RPCR results. All patients were treated according to protocol and no crossover between groups occurred during the 28-day observation period. Patient demographics were similar, including APACHE IV predicted mortality (Table 3).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of subjects enrolled in randomized clinical trial. MRSA = methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; RPCR = rapid polymerase chain reaction.

Table 3.

Baseline Patient Characteristics in RCT

| Characteristic | RPCR Group (n = 22) | Usual Care Group (n = 23) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR) | 64 (55-70) | 65 (56-80) | .30 |

| Men | 6 (27.3) | 11 (47.8) | .16 |

| Race/ethnicity | .96 | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 12 (54.5) | 12 (52.2) | |

| African-American | 6 (27.3) | 8 (34.8) | |

| Hispanic | 1 (4.5) | 1 (4.3) | |

| Other | 1 (4.5) | 1 (4.3) | |

| Unknown | 2 (9.1) | 1 (4.3) | |

| APACHE IV predicted morality, % (IQR) | 28.4 (16.4-44.6) | 33.2 (9.3-53.1) | .75 |

| Pneumonia type | .65 | ||

| Community-acquired pneumonia | 5 (22.7) | 5 (21.7) | |

| Health-care–associated pneumonia | 9 (40.9) | 9 (39.1) | |

| Hospital-acquired pneumonia | 2 (9.1) | 5 (21.7) | |

| Ventilator-associated pneumonia | 6 (27.3) | 4 (17.4) | |

| Hospitalization in previous 90 d | 7 (31.8) | 6 (26.1) | .67 |

| Antibiotics in previous 90 d | 5 (22.7) | 5 (21.7) | 1.00 |

| Hemodialysis | 3 (13.6) | 2 (8.7) | .67 |

| MRSA colonization by nasal swab | 3 (13.6) | 0 (0.0) | .07 |

| Congestive heart failure | 7 (31.8) | 5 (21.7) | .45 |

| Gastric acid suppression | 6 (27.3) | 6 (26.1) | .93 |

| Immunosuppressiona | 5 (22.7) | 9 (39.1) | .24 |

| Nonambulatory before admission | 3 (13.6) | 0 (0.0) | .11 |

| Gastric feeding tube on admission | 2 (9.1) | 1 (4.3) | .61 |

| Obstructive lung disease | 9 (40.9) | 5 (21.7) | .21 |

| Solid tumor | 6 (27.3) | 3 (13.0) | .23 |

| Tracheostomy | 5 (22.7) | 2 (8.7) | .24 |

| Prior stroke/TIA | 7 (31.8) | 4 (17.4) | .26 |

| Cirrhosis | 3 (13.6) | 0 (0.0) | .11 |

| Resident of skilled nursing facility | 5 (22.7) | 1 (4.3) | .10 |

| BAL % neutrophils, median (IQR) | 87 (76-95) | 76 (41-91) | .06 |

| BAL amylase, units/L, median (IQR) | 128 (23-1,854) | 67 (16-165) | .16 |

Data are presented as No. (%) unless otherwise indicated. APACHE = Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; RCT = randomized controlled trial; TIA = transient ischemic attack. See Table 1 legend for expansion of other abbreviations.

BAL microbiology results are presented in Table 4. In the RPCR group, three cultures were positive for MSSA and one for MRSA, although the latter only at a level of 200 CFU/mL, again meeting our clinical criteria for a negative culture. No false-negative RPCR results were found; therefore, no patient in the intervention group continued anti-MRSA treatment. In the control group, six cultures grew MSSA (one culture < 103 CFU/mL) and none grew MRSA.

Table 4.

Microbiological Results of BAL Specimens

| Microbiology Results | RPCR Group (n = 22) | Usual Care Group (n = 23) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gram stain resultsa | |||

| Gram-positive cocci | 9 (40.9) | 12 (52.2) | .45 |

| Gram-positive bacilli | 5 (22.7) | 4 (17.4) | .72 |

| Gram-negative bacilli | 9 (40.9) | 7 (30.4) | .46 |

| Negative Gram stain | 6 (27.3) | 9 (39.1) | .40 |

| Other | 1 (4.5) | 3 (13.0) | .61 |

| Respiratory culture resultsb | |||

| MRSA | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | … |

| MSSA | 3 (13.6) | 5 (21.7) | .70 |

| Streptococcus species | 4 (18.2) | 1 (4.3) | .19 |

| Coagulase-negative staphylococci | 2 (9.1) | 1 (4.3) | .61 |

| Enterococcus species | 1 (4.5) | 0 (0.0) | .49 |

| Enterobacteriaceae | 9 (40.9) | 6 (26.1) | .29 |

| Hemophilus species | 0 (0.0) | 2 (8.7) | .49 |

| Pseudomonas species | 4 (18.2) | 2 (8.7) | .41 |

| Acinetobacter species | 1 (4.5) | 1 (4.3) | 1.00 |

| Polymicrobial | 10 (45.5) | 8 (34.8) | .47 |

| Otherc | 5 (22.7) | 4 (17.4) | .72 |

| Negative | 4 (18.2) | 7 (30.4) | .34 |

Data are presented as No. (%) unless otherwise indicated. See Table 1 and 2 legends for expansion of abbreviations.

Values > 100% because of multiple organisms present on Gram stain and/or final culture.

Organisms shown were isolated from BAL quantitative cultures at concentrations ≥ 103 CFU/mL.

Other includes non-Cryptococcus yeast (n = 4), Neisseria species (n = 3), Corynebacterium species (n = 3), Achromobacter species (n = 1), Moraxella catarrhalis (n = 1), and Stomatococcus species (n = 1).

Duration of anti-MRSA antibiotic administration for the initial suspected MRSA pneumonia episode was significantly shorter for the intervention group (32 h [IQR 22-48] vs 72 h [IQR 50-113], P < .001), the primary end point. Significantly fewer hours of anti-MRSA antibiotic administration in the 28 days after enrollment was also found (46 [24-73] vs 122 [66-219], P < .001).

Adverse events rates in the RPCR group resulting from acute renal failure, thrombocytopenia, or new infection were similar to the usual care group (Table 5). Development of any adverse event during the 28-day follow-up period did not differ between groups (RPCR group 59.1% vs usual care 73.9%, P = .35). Patients in the RPCR group had no increase in duration of mechanical ventilation, ICU length of stay (RPCR group 132 [54-209] vs 158 [44-464], P = .19) or hospital length of stay (15 days [IQR 10-24] vs 29 days [IQR 12-44] days, P = .07) compared with control patients.

Table 5.

Outcomes in RCT

| Outcome | RPCR Group (n = 22) | Usual Care (n = 23) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial anti-MRSA treatment, ha,b | 32 (22-48) | 72 (50-113) | <.001 |

| 28-d total anti-MRSA treatment, ha | 46 (24-73) | 122 (66-219) | <.001 |

| Duration of mechanical ventilation, ha | 132 (54-209) | 158 (44-464) | .44 |

| ICU length of stay, da | 6 (5-14) | 8 (6-26) | .19 |

| Hospital length of stay, da | 15 (10-24) | 29 (12-44) | .07 |

| Any adverse event, No. (%) | 13 (59.1) | 17 (73.9) | .29 |

| Acute renal failure | 4 (18.2) | 5 (21.7) | 1.00 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 5 (22.7) | 6 (26.1) | .79 |

| Nosocomial infection | 8 (36.4) | 12 (52.2) | .29 |

| In-hospital mortality | 3 (13.6) | 9 (39.1) | .05 |

Severity of illness scores decreased significantly in both groups: acute physiologic score improved an average of 1.4 points (P = .006) for each additional study day after randomization. Sequential Organ Failure Assessment scores improved by 0.14 points in both groups for each day of the 14-day period (P = .05) but did not differ significantly between study groups (P = .13).

Hospital mortality in the RPCR group was 13.6% compared with 39.1% for usual care (95% CI of difference, –3.3% to 50.3%; P = 0.06). Although APACHE IV-predicted mortality on ICU admission was numerically lower for patients enrolled in the RPCR group (28.4% vs 33.2%, P = .75), the standardized mortality ratio (observed/predicted) was 0.48 for the RPCR group and 1.18 for the usual care group.

Discussion

Our RCT demonstrated that rapid diagnostic testing use on BAL fluid for critically ill patients with suspected MRSA pneumonia safely decreased anti-MRSA antibiotic use. Of interest, RPCR use for the initial suspected pneumonia episode had a carryover effect, leading to even greater differences in vancomycin/linezolid use for the entire subsequent 28-day study period. Although not a predefined coprimary end point as has been suggested for studies of antibiotic stewardship,28 all predefined safety parameters showed trends toward better outcomes in the RPCR group. Overall results suggest that early discontinuation of anti-MRSA antibiotics was not only safe but potentially beneficial.

A trend toward mortality benefit in the RPCR arm is consistent with association between fewer antibiotics and lower mortality found in prior studies of antibiotic treatment made on the basis of more accurate diagnosis.29, 30, 31 A major hurdle for RCTs similar to this is the primary intensivist’s acceptance of the safety of antibiotic discontinuation on the basis of a diagnostic test.32 When clinicians resist altering antibiotics because of results of more accurate tests in other RCTs, no change in outcome was found33, 34, 35; therefore, validation of the specific assay in our own patient population and emphasis on safety by multiple assessments as a secondary end points was critical. As a result, only two patients were excluded from the RCT because of primary physician discomfort with the potential to discontinue anti-MRSA treatment made on the basis of RPCR testing.

As part of the protocol, we confirmed that the primary clinicians were committed to continuing anti-MRSA coverage at least until BAL culture results were available. We performed this study in the setting of an active unit-based antibiotic stewardship program focused on decreasing vancomycin and linezolid use. The effectiveness of this program is demonstrated by the relatively short median 72-h duration in the control patient population; therefore, even greater differences in anti-MRSA treatment may result from adoption of this rapid assay in ICUs without this baseline stewardship emphasis.

Determining the need for anti-MRSA coverage in ventilated patients is difficult. Many ICU patients have multiple comorbidities, leading to frequent contact with the health-care system and resultant increased likelihood of drug-resistant pneumonia. Although published clinical prediction models help refine empiric antibiotic prescription, the overlap in clinical characteristics does not discriminate between MRSA and other MDR pathogens sufficiently to avoid anti-MRSA antibiotic overuse.8, 9, 36, 37 Most empirical anti-MRSA therapy is therefore made on the basis of guideline recommendations. Recommendations of both ATS/IDSA and International guidelines for management of hospital-acquired pneumonia/ventilator-associated pneumonia would encourage empirical anti-MRSA until culture results were available for all these patients on the basis of characteristics of our specific ICU.4, 5

In addition to high pretest probability of MRSA pneumonia on the basis of clinical risk factors for MRSA, gram-positive cocci seen on a Gram stain of BAL would suggest a higher risk of MRSA.29 A negative RPCR result in nine patients (40.2%) with gram-positive cocci on Gram stain allowed safe vancomycin/linezolid discontinuation.

Nasopharyngeal colonization with MRSA is a risk factor for subsequent MRSA pneumonia, and detection by culture or PCR has been suggested as an alternative screen for the need for anti-MRSA treatment.38, 39 No RCT has yet addressed this strategy; therefore, the safety of avoiding anti-MRSA treatment in all patients who have a negative nasal culture or PCR is unclear. Operating characteristics in clinical practice are also not well defined, and variation in the sampling technique is well known for nasal swabs. The IDSA/ATS guidelines reviewed but did not recommend this strategy.4 In addition, nasal colonization is not mandated or practiced in all ICUs, the prevalence in some ICUs is 20% to 30%, with fewer than one-half developing MRSA pneumonia, and sensitivity decreases with time in the hospital.38, 39 Our RCT was too small to address this issue, with only three cases (6.7%) of MRSA nasal colonization in the entire study group; none had MRSA by either RPCR or BAL culture.

The high sensitivity and negative predictive value we observed is consistent with prior studies of similar PCR technology in lower respiratory tract samples.20, 21, 22, 23, 24 Leone et al22 reported technical failures in up to 10% using the Cepheid Nasal Complete assay. In the assay validation portion of our study, only 3.2% of the MRSA/SA SSTI assays initially yielded indeterminate results, but an unambiguous result was achieved when run a second time. Other PCR-based or rapid diagnostic testing technologies with similar operating characteristics, particularly the > 95% negative predictive value, are likely to also allow antibiotic discontinuation to a similar degree.

Because RPCR uses a far smaller volume of BAL fluid (0.05 mL) compared with quantitative cultures, a false-negative result may occur from sampling error or because the number of copies of bacterial DNA were below the diagnostic threshold of the specific RPCR test. The single false-negative MRSA RPCR result occurred in a patient in whom the positive culture did not meet the BAL quantitative culture threshold for pneumonia and who was not treated for MRSA pneumonia.29

Of interest, the four false-positive RPCRs for MRSA in the assay validation phase of the study were in patients with MSSA respiratory tract infections, including pneumonias with a high bacterial load. Oxacillin-susceptible mecA-positive S aureus isolates have been reported previously.40, 41 In vitro treatment suggests that some are truly resistant to beta-lactams when exposed.40, 42 An alternative explanation for a false-positive assay is that RPCR may detect a methicillin-resistant subpopulation in the much larger MSSA infection, similar to that seen in other infections.43

Limitations

Important limitations exist for these studies. For the assay validation phase of the study, we collected BAL samples in a cohort of critically ill adults at a single center with a relatively low prevalence of culture-positive staphylococcal pneumonia. Although RPCR has an excellent negative odds ratio, the negative predictive value will vary on the basis of prevalence of MRSA at individual institutions. We also validated only on large-volume BAL specimens and the operating characteristics may vary for tracheal aspirates, expectorated sputum, protected specimen brush, or mini-BAL samples.

Our RCT was small; however, the number enrolled was decided by a power analysis performed before study initiation. The appropriateness of the assumptions in that power analysis was confirmed by a statistically and clinically significant difference in duration of anti-MRSA treatment between study groups; however, the small size limits the confidence in other findings, particularly the mortality difference. Conversely, the consistent beneficial trends in all safety analyses give reassurance regarding the overall safety of early antibiotic discontinuation.

A small possibility exists that a false-negative RPCR test could lead to premature discontinuation of anti-MRSA agents before culture results availability. Because no culture-positive patient in our RCT had a false-negative RPCR result, we are unable to evaluate adverse clinical effects of inappropriate early discontinuation of anti-MRSA agents before formal BAL specimen culture results. Patients were not stratified by number of clinical risk factors for MRSA pneumonia in the RCT, potentially leading to differential risk between the two groups. Table 3 demonstrates that no significant differences between the groups were found and that, numerically, all risk factors for MRSA except immunosuppression were more common in the RPCR group. In addition, our primary focus was on MRSA, and we did not evaluate whether RPCR could be used to safely de-escalate to MSSA coverage alone. Finally, the results from this pilot study in a single institution may not apply to other ICUs with a different prevalence of MRSA pneumonia and/or different antibiotic stewardship patterns; results should be validated in a different cohort.

Conclusions

Use of a rapid PCR-based diagnostic test for MRSA with high sensitivity and excellent NLR resulted in significant reductions in use of anti-MRSA agents in mechanically ventilated patients with suspected MRSA pneumonia. Use of the RPCR was found to have a carryover effect of decreasing anti-MRSA use even for subsequent suspected infections within 28 days. Stopping or avoiding anti-MRSA antibiotic use on the basis of RPCR results not only had no adverse effects, but was actually associated with trends in lower adverse events, hospital length of stay, and in-hospital mortality. Early safe discontinuation of anti-MRSA antibiotics on the basis of rapid diagnostic testing can play an important role in antibiotic stewardship.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: R. G. W. takes responsibility for the content of the manuscript, including data and analysis. R. D. S., C. Q., and R. G. W. undertook conception and design. J. R. P., R. D. S., C. I. P., B. D. L., H. K. D., M. M., C. Q., and R. G. W. acquired data. J. R. P., B. D. L., and R. G. W. performed analysis and interpretation. J. R. P. and B. D. L. undertook the initial draft. R. D. S., C. I. P., H. K. D., M. M., C. Q., and R. G. W. reviewed and revised for important intellectual content.

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures: The authors have reported to CHEST the following: R. G. W. is a consultant for bioMerieux and his institution has received research grants from bioMerieux and Curetis. None declared (J. R. P., R. D. S., C. I. P., B. D. L., H. K. D., M. M., C. Q.).

Role of sponsor: The sponsor had no role in the design of the study, the collection and analysis of the data, or the preparation of the manuscript.

Additional information: The e-Appendix can be found in the Supplemental Materials section of the online article.

Footnotes

FUNDING/SUPPORT: This study was supported by a grant from the Dixon Young Investigator Award (R. D. S., R. G. W.) from the Northwestern Medical Foundation. R. D. S. and C. I. P. were supported by National Institutes of Health/National Heart, Lung, and Blood InstituteT32 HL076139 Training Program in Lung Sciences grant.

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Shorr A.F., Tabak Y.P., Gupta V., Johannes R.S., Liu L.Z., Kollef M.H. Morbidity and cost burden of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in early onset ventilator-associated pneumonia. Crit Care. 2006;10(3):R97. doi: 10.1186/cc4934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wunderink R.G., Niederman M.S., Kollef M.H. Linezolid in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus nosocomial pneumonia: a randomized, controlled study. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(5):621–629. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Thoracic Society, Infectious Diseases Society of America Guidelines for the management of adults with hospital-acquired, ventilator-associated, and healthcare-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(4):388–416. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200405-644ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kalil A.C., Metersky M.L., Klompas M. Management of adults with hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonia: 2016 Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Thoracic Society. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(5):e61–e111. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Torres A., Niederman M.S., Chastre J. International ERS/ESICM/ESCMID/ALAT guidelines for the management of hospital-acquired pneumonia and ventilator-associated pneumonia: guidelines for the management of hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP)/ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) of the European Respiratory Society (ERS), European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM), European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) and Asociacion Latinoamericana del Torax (ALAT) Eur Respir J. 2017;50(3) doi: 10.1183/13993003.00582-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chalmers J.D., Rother C., Salih W., Ewig S. Healthcare-associated pneumonia does not accurately identify potentially resistant pathogens: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58(3):330–339. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aliberti S., Cilloniz C., Chalmers J.D. Multidrug-resistant pathogens in hospitalised patients coming from the community with pneumonia: a European perspective. Thorax. 2013;68(11):997–999. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2013-203384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shindo Y., Ito R., Kobayashi D. Risk factors for drug-resistant pathogens in community-acquired and healthcare-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188(8):985–995. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201301-0079OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ekren P.K., Ranzani O.T., Ceccato A. Evaluation of the 2016 Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society Guideline criteria for risk of multidrug-resistant pathogens in patients with hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonia in the ICU. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197(6):826–830. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201708-1717LE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith S.B., Ruhnke G.W., Weiss C.H., Waterer G.W., Wunderink R.G. Trends in pathogens among patients hospitalized for pneumonia from 1993 to 2011. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(11):1837–1839. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.4344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klein E.Y., Mojica N., Jiang W. Trends in methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus hospitalizations in the United States, 2010-2014. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65(11):1921–1923. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Evans M.E., Kralovic S.M., Simbartl L.A., Jain R., Roselle G.A. Eight years of decreased methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus health care-associated infections associated with a Veterans Affairs prevention initiative. Am J Infect Control. 2017;45(1):13–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2016.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jain R., Kralovic S.M., Evans M.E. Veterans Affairs initiative to prevent methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(15):1419–1430. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1007474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moran G.J., Krishnadasan A., Gorwitz R.J. Prevalence of methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus as an etiology of community-acquired pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(8):1126–1133. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones B.E., Jones M.M., Huttner B. Trends in antibiotic use and nosocomial pathogens in hospitalized veterans with pneumonia at 128 medical centers, 2006-2010. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(9):1403–1410. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berger A., Edelsberg J., Oster G., Huang X., Weber D.J. Patterns of initial antibiotic therapy for community-acquired pneumonia in U.S. hospitals, 2000 to 2009. Am J Med Sci. 2014;347(5):347–356. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e318294833f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rossi F., Diaz L., Wollam A. Transferable vancomycin resistance in a community-associated MRSA lineage. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(16):1524–1531. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1303359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aljadhey H., Mahmoud M.A., Mayet A. Incidence of adverse drug events in an academic hospital: a prospective cohort study. Int J Qual Health Care. 2013;25(6):648–655. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzt075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luther M.K., Timbrook T.T., Caffrey A.R., Dosa D., Lodise T.P., LaPlante K.L. Vancomycin plus piperacillin-tazobactam and acute kidney injury in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2018;46(1):12–20. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cercenado E., Marin M., Burillo A., Martin-Rabadan P., Rivera M., Bouza E. Rapid detection of Staphylococcus aureus in lower respiratory tract secretions from patients with suspected ventilator-associated pneumonia: evaluation of the Cepheid Xpert MRSA/SA SSTI assay. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50(12):4095–4097. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02409-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oh A.C., Lee J.K., Lee H.N. Clinical utility of the Xpert MRSA assay for early detection of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Med Rep. 2013;7(1):11–15. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2012.1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leone M., Malavieille F., Papazian L. Routine use of Staphylococcus aureus rapid diagnostic test in patients with suspected ventilator-associated pneumonia. Crit Care. 2013;17(4):R170. doi: 10.1186/cc12849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dureau A.F., Duclos G., Antonini F. Rapid diagnostic test and use of antibiotic against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in adult intensive care unit. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2017;36(2):267–272. doi: 10.1007/s10096-016-2795-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trevino S.E., Pence M.A., Marschall J., Kollef M.H., Babcock H.M., Burnham C.D. Rapid MRSA PCR on respiratory specimens from ventilated patients with suspected pneumonia: a tool to facilitate antimicrobial stewardship. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2017;36(5):879–885. doi: 10.1007/s10096-016-2876-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wunderink R.G., Waterer G. Advances in the causes and management of community acquired pneumonia in adults. BMJ. 2017;358:j2471. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j2471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zimmerman J.E., Kramer A.A., McNair D.S., Malila F.M. Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) IV: hospital mortality assessment for today's critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(5):1297–1310. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000215112.84523.F0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vincent J.L., Moreno R., Takala J. The SOFA (Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. On behalf of the Working Group on Sepsis-Related Problems of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med. 1996;22(7):707–710. doi: 10.1007/BF01709751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gillespie D., Francis N.A., Carrol E.D., Thomas-Jones E., Butler C.C., Hood K. Use of co-primary outcomes for trials of antimicrobial stewardship interventions. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18(6):595–597. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30289-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fagon J.Y., Chastre J., Wolff M. Invasive and noninvasive strategies for management of suspected ventilator-associated pneumonia. A randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132(8):621–630. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-8-200004180-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singh N., Rogers P., Atwood C.W., Wagener M.M., Yu V.L. Short-course empiric antibiotic therapy for patients with pulmonary infiltrates in the intensive care unit. A proposed solution for indiscriminate antibiotic prescription. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162(2 Pt 1):505–511. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.2.9909095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Jong E., van Oers J.A., Beishuizen A. Efficacy and safety of procalcitonin guidance in reducing the duration of antibiotic treatment in critically ill patients: a randomised, controlled, open-label trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16(7):819–827. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)00053-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Broom A., Broom J., Kirby E. Cultures of resistance? A Bourdieusian analysis of doctors' antibiotic prescribing. Soc Sci Med. 2014;110:81–88. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.The Canadian Critical Care Trials Group A randomized trial of diagnostic techniques for ventilator-associated pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(25):2619–2630. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sanchez-Nieto J.M., Torres A., Garcia-Cordoba F. Impact of invasive and noninvasive quantitative culture sampling on outcome of ventilator-associated pneumonia: a pilot study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157(2):371–376. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.2.97-02039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ruiz M., Torres A., Ewig S. Noninvasive versus invasive microbial investigation in ventilator-associated pneumonia: evaluation of outcome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162(1):119–125. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.1.9907090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shorr A.F., Myers D.E., Huang D.B., Nathanson B.H., Emons M.F., Kollef M.H. A risk score for identifying methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in patients presenting to the hospital with pneumonia. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:268. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Webb B.J., Dascomb K., Stenehjem E., Dean N. Predicting risk of drug-resistant organisms in pneumonia: moving beyond the HCAP model. Respir Med. 2015;109(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2014.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sarikonda K.V., Micek S.T., Doherty J.A., Reichley R.M., Warren D., Kollef M.H. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus nasal colonization is a poor predictor of intensive care unit-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections requiring antibiotic treatment. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(10):1991–1995. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181eeda3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Giancola S.E., Nguyen A.T., Le B. Clinical utility of a nasal swab methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus polymerase chain reaction test in intensive and intermediate care unit patients with pneumonia. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2016;86(3):307–310. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2016.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Labrou M., Michail G., Ntokou E., Pittaras T.E., Pournaras S., Tsakris A. Activity of oxacillin versus that of vancomycin against oxacillin-susceptible mecA-positive Staphylococcus aureus clinical isolates evaluated by population analyses, time-kill assays, and a murine thigh infection model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56(6):3388–3391. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00103-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ikonomidis A., Michail G., Vasdeki A. In vitro and in vivo evaluations of oxacillin efficiency against mecA-positive oxacillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52(11):3905–3908. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00653-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Proulx M.K., Palace S.G., Gandra S. Reversion from methicillin susceptibility to methicillin resistance in staphylococcus aureus during treatment of bacteremia. J Infect Dis. 2016;213(6):1041–1048. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Band V.I., Crispell E.K., Napier B.A. Antibiotic failure mediated by a resistant subpopulation in Enterobacter cloacae. Nat Microbiol. 2016;1(6):16053. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.