Abstract

Dysregulation of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling cascade has been associated with the pathology of neurodegenerative disorders, specifically Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Both in vivo models and post-mortem brain samples of individuals with AD have commonly shown hyperactivation of the pathway. In the present study, we examine how neuron subset-specific deletion of Pten (NS-Pten) in mice, which present with hyperactive mTOR activity, effects the hippocampal protein levels of key neuropathological hallmarks of AD. We found NS-Pten knockout (KO) mice to have elevated levels of amyloid-beta (Aβ), alpha-synuclein, neurofilament-L, and pGSK3α in the hippocampal synaptosome compared to NS-Pten wild type (WT) mice. In contrast, there was decreased expression of APP, tau, GSK3α, and GSK3β in NS-Pten KO hippocampi. Overall, there were significant alterations in levels of proteins associated with AD pathology in NS-Pten KO mice. This study provides novel insight into how altered mTOR signaling is linked to AD pathology, without the use of an in vivo AD model that already displays neuropathological hallmarks of the disease.

Keywords: mTOR, Pten, Alzheimer’s, amyloid beta, tau

Introduction

Cell signaling via the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway controls a multitude of cellular functions in the brain throughout the lifespan. The mTOR kinase is a master regulator of the survival, differentiation, and development of neurons, as well as regulates several metabolic and autophagic processes [1]. In the adult brain, mTOR signaling is critical for synaptic plasticity, learning, and memory formation [1]. Given these prominent regulatory roles, previous studies speculate that mTOR may be a promising target for attenuating pathologic neurodegeneration in the adult brain [2, 3]. Several neurodegenerative disorders, including Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Huntington’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease, exhibit dysregulated mTOR activity and have impaired mTOR-dependent functions [4].

Alzheimer’s disease is the leading cause of dementia in the elderly population, accounting for approximately 60–80% of all dementia cases worldwide [5]. This disease is characterized by intracellular plaques formed by the amyloid β-peptide (Aβ) and extracellular neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) comprised of hyperphosphorylated tau [6]. Evidence has shown Aβ accumulation to have a prominent role in AD pathology, initiating a deleterious cascade resulting in cognitive impairment. Among the host of growth factors, nutrients, and stress signals that traditionally stimulate mTOR signaling, Aβ has also been shown to activate this pathway [7].

In both in vivo models of AD and in post-mortem brain samples of individuals with the disease, numerous studies have demonstrated mTOR hyperactivation [8–10]. This hyperactivation has been found to be, in part, mediated by the accumulated Aβ in diseased neural tissue [11]. One critical regulator of Aβ clearance and degradation is the induction of autophagy, which is negatively controlled by mTOR activity. Thus, autophagic processes are often dysregulated in AD mouse models and in individuals with AD [12]. This concomitant enhancement of Aβ aggregation and decreased Aβ clearance seems to create a positive feedback loop, fostering net growth of plaques and mTOR hyperactivation. mTOR signaling also plays a role in tau aggregation and degradation, and pathway activity can increase the translation of tau protein [4, 10]. Considerable evidence has linked mTOR hyperactivation with AD-associated pathology, however, the exact mechanism linking Aβ plaques, NFTs, and cognitive decline in the brains of individuals with AD remains elusive.

Phosphatase and tensin homolog located on chromosome 10 (PTEN) functions to inhibit the mTOR pathway and may play a critical role in regulating AD pathology. This protein negatively regulates PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling by removing a phosphate group from phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate (PIP3), converting it to PIP2. PTEN has well established roles in neurodevelopment, as PTEN loss of function results in hyperconnectivity, excessive brain growth, and cognitive impairments [13]. There is also a growing body of evidence that PTEN contributes to a number of normal brain functions, including synaptic transmission, plasticity, neurogenesis, neurite outgrowth, and long-term depression [14]. Knafo et al., (2016) found that PTEN functions downstream of the action of Aβ, and that the PDZ-binding domain of PTEN is essential to the AD-associated synaptic dysfunction observed in the disease. Furthermore, they found that inhibiting PTEN rescued normal synaptic function and cognitive impairments both in vitro and in vivo models of AD [15].

The present study will examine how neuron subset-specific deletion of the Pten gene (NS-Pten) in mice can result in alterations in the levels of proteins associated with AD. We will examine the expression of Aβ, tau, amyloid precursor protein (APP), alpha-synuclein, neurofilament-L, phospho-GSK3α (pGSK3α), GSK3α, and GSK3β. These findings enhance our understanding of how hyperactive mTOR signaling, without the presence of AD-pathology in an in vivo AD model, can be associated with protein alterations characteristic of Alzheimer’s disease pathology.

Methods

Animals

Subject mice included adult (8 weeks old) neuron subset-specific Pten (NS-Pten) conditional knockout (KO) (n = 9) and wild type (WT) (n = 9) mice, previously described as GFAP-Cre; PtenloxP/loxP mice [16, 17]. This conditional KO model exhibits Cre activity primarily in hippocampal granule neurons of the dentate gyrus which express NeuN, with activity rarely observed in glial cells immunopositive for S100β or GFAP [16]. NS-PtenloxP/+ heterozygote parents were bred over 10 generations on a FVB-based backcrossed strain to produce NS-Pten+/+ wild type (WT), NS-PtenloxP/+ heterozygous (HT), and NS-PtenloxP/loxP knockout (KO) mice. Only homozygous WT and KO mice were utilized in all experiments. All mice were generated and group housed at Baylor University in standard laboratory conditions (22°C, 12 h light/12 h dark diurnal cycles) with food and water provided ad libitum. All procedures were conducted in compliance with the Baylor University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and the National Institute of Health Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Western blotting analysis

Adult NS-Pten KO and WT mice were euthanized at approximately 8 weeks of age and brains were rapidly dissected, rinsed in 1X PBS on ice, and the hippocampus removed prior to being placed on dry ice and stored at −80°C. Whole hippocampus samples from the right hemisphere were homogenized in ice-cold homogenization buffer containing 0.32M sucrose, 1mM EDTA, 5mM HEPES, and a protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma, USA) and processed for western blotting as previously described [18]. Crude synaptosomes of all samples were run through 8–12% SDS-PAGE gels, followed by being transferred overnight to Hybond-P polyvinyl difluoride membranes (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ, USA). Membranes were incubated for 1 h at room temperature in a blocking solution consisting of 5% nonfat milk diluted in 1x Tris buffered saline (50mM Tris-HCl, pH = 7.4, 150mM NaCl) with 0.1% Tween (1X TTBS) and 1mM Na3VO4. The membranes were then incubated overnight at 4oC on a Hoeffer rocker II with the following primary antibodies in 5% milk in TTBS: alpha-synuclein, beta-amyloid, neurofilament-L, phospho-GSK3α, GSK3α, GSK3β, APP, and tau (see Supplemental Digital Content [Table S1] for antibody specifics). Following the incubation period, membranes were washed in 1X TTBS (3 × 5 min), and then incubated with horseradish peroxidase-labeled secondary antibodies in a milk solution (1:20,000) for 1 h. Secondary antibodies were anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) or anti-mouse IgG (Cell Signaling Technology, Boston, MA, USA). Following another set of washes in 1X TTBS (3 × 5 min), membranes were incubated in ECL Prime (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ, USA) for 5 min at room temperature and immunoreactive bands were imaged with a digital western blot imaging system (ProteinSimple, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The optical density of immunoreactive bands was measured using ProteinSimple AlphaView software. Measurements from all protein bands of interest were normalized to endogenous actin or mortalin levels for each tissue sample and all groups were normalized to the control group average per blot. All experimental data points represent a single tissue sample (n = 1).

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 7 software (San Diego, CA, USA) or SPSS 25.0 (IBM, USA). Independent samples t-tests were utilized for western blot analyses between NS-Pten KO and WT mice. In cases in which the homogeneity of variance assumption was violated, nonparametric Mann-Whitney U tests were conducted. For all analyses a value of p < 0.05 was considered significant. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) or the median ± interquartile range (IQR).

Results

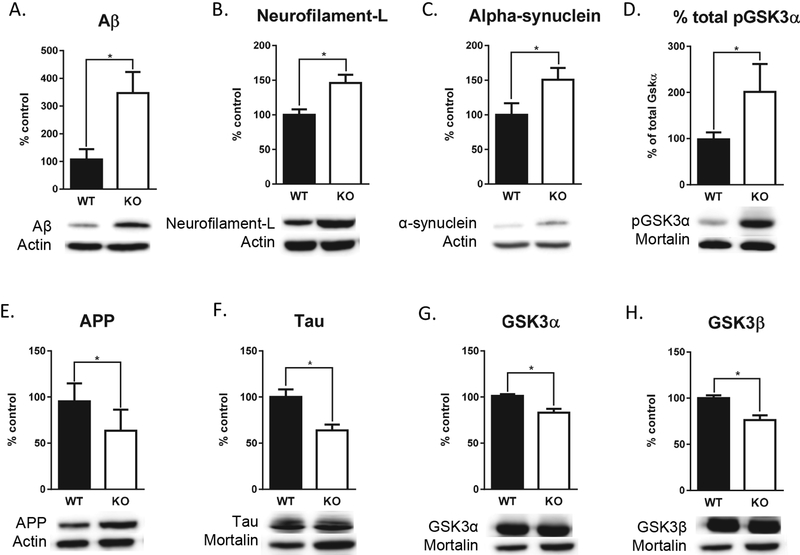

The present study examined the influence of neuron subset-specific deletion of Pten (NS-Pten) on proteins associated with Alzheimer’s disease pathology and found significant alterations in NS-Pten knockout (KO) mice hippocampal synaptosome protein levels compared to wild type (WT) mice. NS-Pten KO mice had significantly elevated Aβ U = 7, p < 0.01, neurofilament-L t(1,16) = 3.24, p < 0.01, alpha-synuclein t(1,16) = 2.12, p = 0.05, and % total pGSK3α U = 4, p = 0.001. In contrast, NS-Pten KO mice had significantly decreased amyloid precursor protein (APP) U = 15, p < 0.05, GSK3α U = 9, p < 0.01, GSK3β t(1,16) = 3.99, p = 0.001, and tau t(1,16) = 3.49, p =< 0.01 hippocampal protein levels compared to WT mice (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Deletion of Pten results in altered hippocampal synaptosome protein levels associated with Alzheimer’s disease pathology. NS-Pten KO mice (n = 9) had increased expression of Aβ (A), neurofilament-L (B), alpha-synuclein (C), % total pGSK3α (D), and APP (E) compared to NS-Pten WT mice (n = 9). In contrast, NS-Pten KO mice had significantly reduced expression of tau (F), GSK3α (G), and GSK3β (H). Data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) for neurofilament-L, alpha-synuclein, tau, and GSK3β and as the median ± interquartile range (IQR) for Aβ, % total pGSK3α, APP, and GSK3α, * p < .05.

Discussion

This study found significant alterations in proteins associated with Alzheimer’s disease pathology in NS-Pten knockout (KO) mice compared to NS-Pten wild type (WT) mice. Specifically, we found elevated levels of Aβ, alpha-synuclein, neurofilament-L, and pGSK3α protein expression in the hippocampal synaptosome of NS-Pten KO mice. We also detected decreased APP, tau, GSK3α, and GSK3β in NS-Pten KO hippocampi. PTEN functions to negatively regulate the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway, and therefore, deletion of this inhibitory protein results in enhanced mTOR signaling. These results corroborate other studies that have shown hyperactivation of the mTOR pathway to be associated with AD pathology. Furthermore, this study provides novel insight into how mTOR is associated with AD pathology without the presence of already developed hallmarks of the disease, such as Aβ accumulation and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs), as seen in many in vivo AD models.

Prior evidence suggests that Aβ is primarily responsible for the hyperactivation of mTOR observed in both the brains of individuals with AD and in AD rodent models [4, 11]. Specifically, Aβ is thought to interact with mTOR signaling through the inhibitory protein proline-rich Akt substrate of 40 kDa (PRAS40), a component of the mTORC1 complex [19]. Aβ directly phosphorylates PRAS40, thus removing its inhibitory effect on mTOR and upregulating pathway activity [11]. Interestingly, we found Aβ to be significantly elevated in the hippocampus of NS-Pten KO mice, suggesting Aβ could potentially be involved in a positive feedback loop contributing to further hyperactivation of the pathway beyond the effect of PTEN deletion.

In addition to the accumulation of Aβ, the mTOR pathway and specifically, PTEN activity, has been linked to tau pathology in AD [8]. Under normal physiological conditions, tau functions as a microtubule-associated protein to promote the assembly of microtubule binding in neurons [20]. However, when hyperphosphorylated, it dissociates from cytoskeletal elements and accumulates contributing to NFT development [20]. Hyperactivation of the mTOR pathway, whether independently or directly related to Aβ accumulation, has been linked to major features of tau pathology, including tau translation, degradation, aggregation, hyperphosphorylation and development of NFTs [3]. Furthermore, mTOR activity can increase the translation of tau mRNA via p70S6K activation, and p70S6K can co-localize with hyperphosphorylated tau, thus promoting tau accumulation in AD [2, 21]. In contrast to this evidence, the present study found decreased tau protein levels in the hippocampal synaptosomes of NS-Pten KO mice compared to controls, suggesting mTOR activity can both promote and protect against tau deposition in the brains of those with AD.

The relationship between PTEN, mTOR signaling, and glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3) is thought to play a pivotal role in the regulation of tau phosphorylation and hyperphosphorylation. PTEN’s inhibitory activity on Akt via PDK1 results in increased GSK3 activation, in which GSK3 can phosphorylate tau at multiple sites in vivo and in vitro promoting development of tau pathology [20, 22]. Thus, it could be predicted that deletion of PTEN leads to downregulation of GSK3, and subsequent reduced tau hyperphosphorylation, coinciding with our findings in the NS-Pten KO mouse. However, we found there to be increased phospho-GSK3β, but downregulated GSK3α and GSK3β, which could explain some of the unexpected findings in tau levels. Increased levels of phospho-Akt substrates, such as phospho-GSK3, have been observed in temporal cortex neurons in humans with AD, which does corroborate our findings of elevated phospho-GSK3α in the NS-Pten KO mice [23]. It is important to note that our study examined proteins in the hippocampal synaptosomal subcellular compartment, while other studies have used total homogenate preparations of tissue from post-mortem AD brains or transfected primary neuronal cultures which could account for discrepancies between studies [21, 22].

The significant impact in which neuronal deletion of Pten had on components of AD pathology supports prior evidence suggesting that mTOR inhibitors could be a potential avenue for treatment of the disease. Studies have shown that the mTOR inhibitor, rapamycin, can prevent memory deficits and reduce Aβ and tau pathology in in vivo AD models [24, 25]. These findings could be attributed to a multitude of mechanisms, most likely by anti-aging effects such as enhancing autophagy function and decreasing protein translation [8, 9, 24, 25]. However, dramatically reducing mTOR activity could also negatively affect cognition, as normal mTOR activity is critical for learning and memory formation [5]. It is essential to continue investigating alternative mechanisms of modulating mTOR, fine tuning the pathway for optimal cellular regulation and cognitive function. In summary, these results highlight the critical role that the mTOR pathway plays in regulating Aβ and tau pathology, as well as other proteins associated with Alzheimer’s disease.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Digital Content: Table S1. Antibody specifics for western blotting.

Pten Hip. AD paper – Table S1.ppt

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the Baylor University Molecular Biosciences Core for the use of equipment for this study. CDR, GDS, and TSJ collected the data; SLH, SON, and JNL analyzed the data; and SLH and JNL wrote the manuscript.

Source of Funding: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) [Grant Number: NS088776]

Footnotes

Statement of Conflicts of Interest: None Declared

References

- [1].Swiech L, Perycz M, Malik A, Jaworski J, Role of mTOR in physiology and pathology of the nervous system, Biochim Biophys Acta 1784 (2008) 116–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Crino PB, The mTOR signalling cascade: Paving new roads to cure neurological disease, Nat Rev Neurol 12 (2016) 379–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Perluigi M, Di Domenico F, Butterfield DA, mTOR signaling in aging and neurodegeneration: At the crossroad between metabolism dysfunction and impairment of autophagy, Neurobiol Dis 84 (2015) 39–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Kaur A, Sharma S, Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) as a potential therapeutic target in various diseases, 25 (2017) 293–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Oddo S, The role of mTOR signaling in Alzheimer disease, Front Biosci (Schol Ed) 4 (2012) 941–952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Hane FT, Lee BY, Leonenko Z, Recent progress in Alzheimer’s disease research, part 1: Pathology, J Alzheimers Dis 57 (2017) 1–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Wullschleger S, Loewith R, Hall MN, TOR signaling in growth and metabolism, Cell 124 (2006) 471–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Caccamo A, De Pinto V, Messina A, Branca C, Oddo S, Genetic reduction of mammalian target of rapamycin ameliorates Alzheimer’s disease-like cognitive and pathological deficits by restoring hippocampal gene expression signature, J. Neurosci 34 (2014) 7988–7998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Caccamo A, Majumder S, Richardson A, Strong R, Oddo S, Molecular interplay between mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), amyloid-beta, and Tau: Effects on cognitive impairments, J Biol Chem 285 (2010) 13107–13120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Li X, Alafuzoff I, Soininen H, Winblad B, Pei JJ, Levels of mTOR and its downstream targets 4E-BP1, eEF2, and eEF2 kinase in relationships with tau in Alzheimer’s disease brain, Febs j 272 (2005) 4211–4220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Caccamo A, Maldonado MA, Majumder S, Medina DX, Holbein W, Magri A, et al. , Naturally secreted amyloid-beta increases mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) activity via a PRAS40-mediated mechanism, J Biol Chem 286 (2011) 8924–8932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Zhao H, Wang ZC, Wang KF, Chen XY, Abeta peptide secretion is reduced by Radix Polygalae-induced autophagy via activation of the AMPK/mTOR pathway, Mol Med Rep 12 (2015) 2771–2776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Zhou J, Parada LF, PTEN signaling in autism spectrum disorders, Curr Opin Neurobiol 22 (2012) 873–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Knafo S, Esteban JA, PTEN: Local and global modulation of neuronal function in health and disease, Trends Neurosci 40 (2017) 83–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Knafo S, Sanchez-Puelles C, Palomer E, Delgado I, Draffin JE, Mingo J, et al. , PTEN recruitment controls synaptic and cognitive function in Alzheimer’s models, Nat. Neurosci 19 (2016) 443–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kwon CH, Zhu X, Zhang J, Knoop LL, Tharp R, Smeyne RJ, et al. , Pten regulates neuronal soma size: A mouse model of Lhermitte-Duclos disease, Nature Genet 29 (2001) 404–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Backman SA, Stambolic V, Suzuki A, Haight J, Elia A, Pretorius J, et al. , Deletion of Pten in mouse brain causes seizures, ataxia and defects in soma size resembling Lhermitte-Duclos disease, Nature Genet 29 (2001) 396–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Lugo JN, Barnwell LF, Ren Y, Lee WL, Johnston LD, Kim R, et al. , Altered phosphorylation and localization of the A-type channel, Kv4.2 in status epilepticus, J Neurochem. 106 (2008) 1929–1940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Sengupta S, Peterson TR, Sabatini DM, Regulation of the mTOR complex 1 pathway by nutrients, growth factors, and stress, Mol Cell 40 (2010) 310–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Zhang X, Li F, Bulloj A, Zhang YW, Tong G, Zhang Z, et al. , Tumor-suppressor PTEN affects tau phosphorylation, aggregation, and binding to microtubules, Faseb j 20 (2006) 1272–1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].An WL, Cowburn RF, Li L, Braak H, Alafuzoff I, Iqbal K, et al. , Up-regulation of phosphorylated/activated p70 S6 kinase and its relationship to neurofibrillary pathology in Alzheimer’s disease, Am J Pathol 163 (2003) 591–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Lovestone S, Reynolds CH, Latimer D, Davis DR, Anderton BH, Gallo JM, et al. , Alzheimer’s disease-like phosphorylation of the microtubule-associated protein tau by glycogen synthase kinase-3 in transfected mammalian cells, Curr Biol 4 (1994) 1077–1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Griffin RJ, Moloney A, Kelliher M, Johnston JA, Ravid R, Dockery P, et al. , Activation of Akt/PKB, increased phosphorylation of Akt substrates and loss and altered distribution of Akt and PTEN are features of Alzheimer’s disease pathology, J Neurochem 93 (2005) 105–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Siman R, Cocca R, Dong Y, The mTOR inhibitor rapamycin mitigates perforant pathway neurodegeneration and synapse loss in a mouse model of early-stage Alzheimer-type tauopathy, PLoS One 10 (2015) e0142340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Spilman P, Podlutskaya N, Hart MJ, Debnath J, Gorostiza O, Bredesen D, et al. , Inhibition of mTOR by rapamycin abolishes cognitive deficits and reduces amyloid-β Levels in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease, PLoS One 5 (2010) e9979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Digital Content: Table S1. Antibody specifics for western blotting.

Pten Hip. AD paper – Table S1.ppt