Abstract

Although aquatic vertebrates and humans are increasingly exposed to water pollutants associated with unconventional oil and gas extraction (UOG), the long-term effects of these pollutants on immunity remains unclear. We have established the amphibian Xenopus laevis and the ranavirus Frog Virus 3 (FV3) as a reliable and sensitive model for evaluating the effects of waterborne pollutants. X. laevis tadpoles were exposed to a mixture of equimass amount of UOG chemicals with endocrine disrupting activity (0.1 and 1.0 μg/L) for 3 weeks, and then long-term effects on immune function at steady state and following viral (FV3) infection was assessed after metamorphosis. Notably, developmental exposure to the mixture of UOG chemicals at the tadpole stage affected metamorphic development and fitness by significantly decreasing body mass after metamorphosis completion. Furthermore, developmental exposure to UOGs resulted in perturbation of immune homeostasis in adult frogs, as indicated by significantly decreased number of splenic innate leukocytes, B and T lymphocytes; and a weakened antiviral immune response leading to increased viral load during infection by the ranavirus FV3. These findings suggest that mixture of UOG-associated waterborne endocrine disruptors at low but environmentally-relevant levels have the potential to induce long-lasting alterations of immune function and antiviral immunity in aquatic vertebrates and ultimately human populations.

Keywords: Water pollutants, ranavirus, antiviral immunity, immune toxicant

1. Introduction

Unconventional oil and gas extraction (UOG) has markedly increased production of oil and natural gas in the U.S. over the last 10 years ((Energy Information Administration, 2016; Kassotis et al., 2015a). The process consists of injecting at high pressures millions of gallons of water mixed with sand, and various chemical agents (including acids, friction reducers, and surfactants) into underground shale deposits at high pressures in order to collect trapped oil and natural gas (Carpenter, 2016; Kassotis et al., 2016b; Mrdjen and Lee, 2015). In addition to physical and chemical damage to ecosystems, there is growing concern about negative health impacts on human populations as well as aquatic wild life in regions where UOG is performed. Indeed, among the large number of chemicals associated with UOG (estimated to be over 750) at least 200 have been detected in wastewater, ground water, and surface water (Elsner and Hoelzer, 2016; Vengosh et al., 2014; Waxman et al., 2011; Webb et al., 2014). A number of these chemicals have been shown to be endocrine or developmental disruptors (Casey et al., 2016). Extensive study of water collected at UOG sites has identified certain chemicals that consistently present at concentration ranging from 0.01 to 2.0 mg/L (Gross et al., 2013; Wilkin and Digiulio, 2010). Among these, 23 showed significant agonistic or antagonistic activity in vitro for various hormone receptors, including androgen, estrogen, and thyroid, progesterone, and glucocorticoid; and are thus considered endocrine disruptor chemicals (EDCs) (Kassotis et al., 2015b; Kassotis et al., 2014). Because of their wide combined distribution across UOG sites, an equimass mixture of these 23 EDCs has been used to model health risks from exposure to water contaminated by UOG. The rationale is that while each EDC may be present at below an effective concentration, the additive combination of multiple EDCs can induce biological effects, especially when exposure occurs during the more sensitive early developmental period. Indeed, exposure of pregnant mice via drinking water with this mixture of 23 chemicals at relevant environmental concentrations induces multiple developmental defects in pups including sperm counts and increased testes, body, heart, and thymus weights (Kassotis et al., 2015b). Maternal exposure also induced elevated serum testosterone levels in male pups (Kassotis et al., 2015b) as well as pituitary hormones and mammary gland development in females (Kassotis et al., 2016a; Sapouckey et al., 2018).

Another less well appreciated biological system affected by EDCs is the immune system (Maqbool et al. 2016; Vandenberg et al. 2012(Boule and Lawrence, 2016; Kuo et al., 2012). The endocrine system, especially the neuroendocrine axis, is known to play an important role in the development and function of the vertebrate immune system including Xenopus (review in (Blom and Ottaviani, 2017; Kinney and Cohen, 2009; Quatrini et al., 2018)). This connection is underlined in metabolic disorders like type 2 diabetes for which EDCs such as bisphenol A and phthalates are considered as promoting factors that affect both endocrine and immune function (Bansal et al., 2018). Notably, early life exposure to several EDCs cause alterations in immune function persisting in adulthood (Boule and Lawrence, 2016). While little is still known about the effects of EDCs associated with UOG, developmental exposure of pregnant mice to similar low doses of the mixture 23 UOG chemicals was found to induce long-term perturbations of the immune system of adult offspring at steady state, and alteration of frequencies of different T cell subsets after immune challenge (Boule et al., 2018). In addition, this developmental exposure to UOG chemicals accentuated immunopathology of experimentally induced of autoimmune encephalitis. Since even modest perturbation of immune function may have decisive consequences on host resistance pathogens, immune alteration potentials of UOG chemical mixture merit further exploration.

We have developed a reliable, sensitive and cost-effective model system based on the amphibian Xenopus and the ranavirus FV3, which is an excellent complement to the mouse model to investigate the impact of early life exposure to waterborne mixtures of UOG toxicants on immunity later in life (Gantress et al., 2003; Jacques et al., 2017). Xenopus are ideally suited to define the long-term health effects of developmental exposure to waterborne pollutants. The Xenopus immune system is extensively characterized and remarkably conserved to that of human Xenopus (Robert and Ohta, 2009). Importantly, Xenopus are completely aquatic at all stages of development and unlike mammals, develop externally, free of maternal influences. Furthermore, metamorphosis parallels the perinatal period in humans (Fini et al., 2012). Ranavirus pathogens like FV3 (large DNA viruses of the family Iridoviridae) have become major viral pathogens, causing infectious diseases and targeting a wide range of aquatic vertebrate species such as amphibians, fish, and reptiles worldwide (Bandin and Dopazo, 2011; Chinchar, 2002; Chinchar et al., 2009; Greer et al., 2005; Jancovich et al., 2010). We have shown that similar to mammals, Xenopus adult frogs rely on efficient B and T cell responses activated by innate immune cells to control and clear FV3 infection (Chen and Robert, 2011; De Jesus Andino et al., 2012; Morales et al., 2010). This Xenopus/FV3 experimental platform has been useful to reveal that certain herbicides (atrazine) and insecticides (carbaryl) contaminating water at low but ecologically-relevant concentrations induce dramatic acute and long-term persisting defects of anti-FV3 immune responses (De Jesus Andino et al., 2017; Sifkarovski et al., 2014).

To investigate the potential of mixture of EDC water pollutants associated with UOG activity we took advantage of the Xenopus/FV3 system. We previously reported that the same mixture of 23 UOG chemicals can affect the immune system of the tadpoles of the amphibian Xenopus laevis (Robert et al., 2018). More specifically, a three week exposure of tadpoles to an equimass ranging from 1 to 0.1 μg/L of the 23 UOG chemicals significantly altered homeostatic expression of myeloid lineage genes. Furthermore, upon infection with the ranavirus FV3, the expression of innate immune response genes TNF-α, IL-iβ, and Type I IFN was reduced and the viral loads were increased (Robert et al., 2018). This is of relevance since aquatic animals such as amphibians are continuously exposed to water pollutants and therefore, are likely to become more susceptible to adverse health effects or physiological consequences such as alteration of immune defense mechanisms against ranavirus pathogens.

Here, we have further tested the hypothesis that developmental exposure of tadpoles to current environmental levels of a mixture of 23 UOG chemicals with demonstrable EDC activity result in long lasting developmental defects leading to altered immune homeostasis and antiviral immunity in adult frogs, thus increasing susceptibility to pathogens such as FV3.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

All outbred Xenopus laevis were from the X. laevis research resource for immunology at the University of Rochester (http://www.urmc.rochester.edu/mbi/resources/Xenopus/) following standard husbandry methodology regularly updated by the Xenopus community (see: http://www.xenbase.org/entry/). All animals were handled in accordance with stringent laboratory and University Committee on Animal Research regulations (Approval number 100577/2003–151).

2.2. Chemical mixture preparation

Twenty-three chemicals (≥97% purity, Sigma Aldrich) were selected based on prior demonstration of endocrine activity, via the estrogen, androgen, progesterone, glucocorticoid, and/or thyroid receptors (Kassotis et al., 2015b; Kassotis et al., 2014). Stock solutions (1 mg/ml) of chemicals were prepared in 100% ethanol (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), stored at −20°C, and used in experiments within 3 months of preparation. The chemicals were: 1,2,4-Trimethylbenzene; 2-(2-Methoxyethoxy)ethanol; 2-Ethylhexanol; 2-Methyl-4-isothiazolin-3-one; Acrylamide; Benzene; Bronopol; Cumene; Diethanolamine; Ethoxylated nonylphenol; Ethoxylated octylphenol; Ethylbenzene; Ethylene glycol; Ethylene glycol monobutyl ether; Naphthalen; N,n; Dimethylformamide; Phenol; Propylene glycol; Sodium tetraborate decahydrate (borax); Styrene Toluene; Triethylene glycol; Xylenes.

2.3. Animals exposure to water contaminants

Three-weeks old (stage 52, 1.5 cm long; (Nieuwkoop and Faber, 1967)) tadpoles were exposed for 3 weeks UOG mixture by diluting an equimass amount of 23 UOG-associated chemicals in the tadpole housing water (dechlorinated water at room temperature [22°C] and neutral pH 6.8–7.0) from a freshly prepared stock solution at a final concentration of 0.1 and 1.0 μg/mL of each constituent chemical as previously described (Kassotis et al., 2015b; Kassotis et al., 2014). Control tadpoles were kept in water spiked with the vehicle control (0.2% ethanol). Animals were then raised in clean water until 6 months of age. The doses were chosen based on estimates of environmentally relevant oral exposures, such that the two concentrations are similar to levels detected in surface and groundwater in UOG production regions (Cozzarelli et al., 2017; Crosby et al., 2018; DiGiulio and Jackson, 2016; Gross et al., 2013) as well they are lethal to tadpoles (Robert et al., 2018). Animals were raised in a room that is controlled for light cycle (12 hrs.light/12 hrs. obscurity) and temperature, and has filtered and dechlorinated water. Animals were maintained at a density of 20 tadpoles or 3–5 post-metamorphic froglets per 4 L container. Tadpoles were fed daily with food pellets (Purina Gel Tadpole Diet), adults were fed daily with adult type pellets (Zeigler’s Xenopus pellets). While the stability of all 23 chemicals in water is uncertain or unknown, to ensure consistency of exposure, minimize potential degradation and fluctuations in the concentration over time, water and chemicals for each treatment was changed weekly.

2.4. Frog virus 3 stocks and infection

Baby hamster kidney cells (BHK-21, ATCC No. CCL-10) were maintained in DMEM (Invitrogen) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen), streptomycin (100μg/mL), and penicillin (100 U/mL) with 5% CO2 at 37°C, then 30°C for infection. FV3 was grown using a single passage through BHK-21 cells and was subsequently purified by ultracentrifugation on a 30% sucrose cushion. Adult frogs were infected by i.p. injection of 1×106 PFU in 10 μL of amphibian PBS (APBS) using a glass Pasteur pipette whose small end had been pulled in a flame (De Jesus Andino et al., 2012). Uninfected control animals were mock-infected with an equivalent volume of APBS. Three and six days post-infection (dpi), animals were euthanized using 0.1% tricaine methanesulfonate (TMS) buffered with bicarbonate prior to dissection and extraction of nucleic acids from tissues (Fig. 1 A).

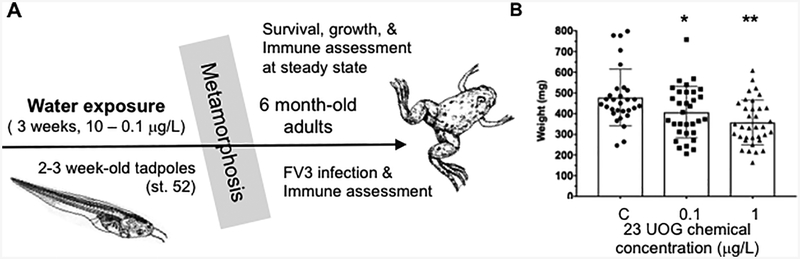

Figure 1.

(A) Schematic of developmental treatment strategy. After 3 weeks exposure to the UOG chemical mixture, tadpoles were raised in clean water until 6 month of age, past metamorphosis. (B) Individual and averages ±SD of whole body weights in mg at metamorphosis completion (developmental stage 66) for each treatment group. * P<0.05 significant differences relative to EtOH treated only controls using one-way ANOVA test and Tukey’s post-hoc test (GraphPad Prism 6).

2.5. Quantitative gene expression analyses

Total RNA was extracted from frog kidneys, livers and spleens using Trizol reagent, following the manufacturer’s protocol (Invitrogen). cDNA was synthetized with 0.5 μg of RNA in 20 μl using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), and 1μl of cDNA template was used in all RT-PCRs and 150 ng DNA for PCR. Minus RT controls were included for every reaction. A water-only control was included in each reaction. RNA was checked for purity via nanodrop and only samples that amplified the housekeeping gene Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) within 20 cycles were used for qPCR analysis. The qPCR analysis was performed using the ABI 7300 real-time PCR system with PerfeCT SYBR Green FastMix, ROX (Quanta) and ABI sequence detection system (SDS) software. GAPDH controls were used in conjunction with the delta∧delta CT method to analyze cDNA for gene expression. All primer sequences are listed in Table S1.

2.6. Viral load quantification by qPCR

FV3 viral loads were assessed by absolute qPCR by analysis of isolated DNA in comparison to a serially diluted standard curve. Briefly, an FV3 DNA Pol II PCR fragment was cloned into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega). This construct was amplified in bacteria, quantified and serially diluted to yield 1010-101 plasmid copies of the vDNA POL II. These dilutions were employed as a standard curve in subsequent absolute qPCR experiments to derive the viral genome transcript copy numbers, relative to this standard curve.

2.7. Flow cytometry

The XRRI provided X. laevis-specific monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), including anti-CD5 (1F8), anti-IgM (10A9); anti-NK cell (1F8), anti-class MHCII (AM20) and biotinylated anti-CD8 (AM22) as well as fluorophore-goat-anti-mouse Ab (BD Biosciences) and streptavidin-fluorophore (BioLegend). Splenocytes (2.5 × 105 cells/per treatment) were sequentially stained at 4°C with 100 μl of the different undiluted hybridoma supernatant, secondary goat Abs, biotinylated anti-CD8 mA and streptavidin according to detailed published protocol (Edholm, 2018). Dead cells were excluded with propidium iodide (BD Pharmingen). 10,000 events per sample, gated on live cells, were collected with Accuri C6 (BD Biosciences). Data was analyzed with FlowJo (TreeStar).

2.8. Statistical analysis

The Mann-Whitney U and ANOVA as well as non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis tests were used for statistical analysis of expression and viral load data. Analyses were performed using a Vassar Stat online resource (http://vassarstats.net/utest.html). Statistical analysis of survival data was performed using a Log-Rank Test (GraphPad Prism 6). A probability value of p<0.05 was used in all analyses to indicate significance. Error bars on all graphs represent the standard error of the mean (SEM).

3. Results

3.1. Effects o f UOG mixture on X. laevis metamorphic development.

Since anuran metamorphosis is under tight endocrine regulation, we first assessed whether developmental exposure to a mixture of UOG chemicals with EDC activity would affect its completion. Pre-metamorphic tadpoles (stage 52) were exposed for 3 weeks to different amount (1 and 0.1 μg/L) of UOG mixture, then transferred to clean water to grow until they metamorphose and reach adult stages (Fig. 1A). These two concentrations match those used in mouse to reflect environmentally relevant exposure (Boule et al., 2018) and are in the low range of the average concentration for which each of these chemicals has been found in ground water near UOG operations (i.e., 0.01 to 2.0 μg/L; (Gross et al., 2013; Wilkin and Digiulio, 2010)). We did not test higher concentrations (5 and 10 μg/L) because they were shown to induce marked mortality in tadpoles during the exposure (Robert et al., 2018).

Following 3 weeks exposure to 1.0 or 0.1 μg/L of UOG mixture, no significant increase mortality nor gross developmental abnormality (e.g., limb deformation, etc.) was observed over the whole experiment. In particular, there was no increase in mortality during metamorphosis compared to control animals exposed to 0.2% ethanol (Table 1). To refine our analysis, we determined the time in days for each animal treated at tadpole stage to complete metamorphosis, which is defined by the full loss of the tail. There was no statistically significant difference in the time to complete metamorphosis across the different treatment group (Table 1). However, developmental exposure to both 1.0 μg/L and 0.1 μg/L UOG mixture resulted in a statistically significant decrease whole body weight at the end of metamorphosis (Table 1; Fig. 1B). Collectively, these data strongly suggest that UOG chemicals, even at relatively low doses, have the potential to perturb amphibian metamorphic development.

Table 1:

Survival, body weight and median time to reach metamorphosis completion (stage 66) following UOG treatment.

| Treatment | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Measurements | Vehicle control |

0.1 μg/L | 1 μg/L |

| Number of animals | 30 | 33 | 35 |

| Number of dead animals after treatment |

4 (13%) |

4 (12%) |

5 (14%) |

| Median time (wks.) to reach stage 66 |

25 | 19 | 16 |

| Weight (mg) | 478±25 | 401±22 p>0.04 |

357±18 p>0.0002 |

P value determined between vehicle control and UOG-treated animals using one-way ANOVA test and Tukey’s post-hoc test (GraphPad Prism 6).

3.2. Effects o f developmental exposure to UOG chemicals on splenic leukocytes at steady state

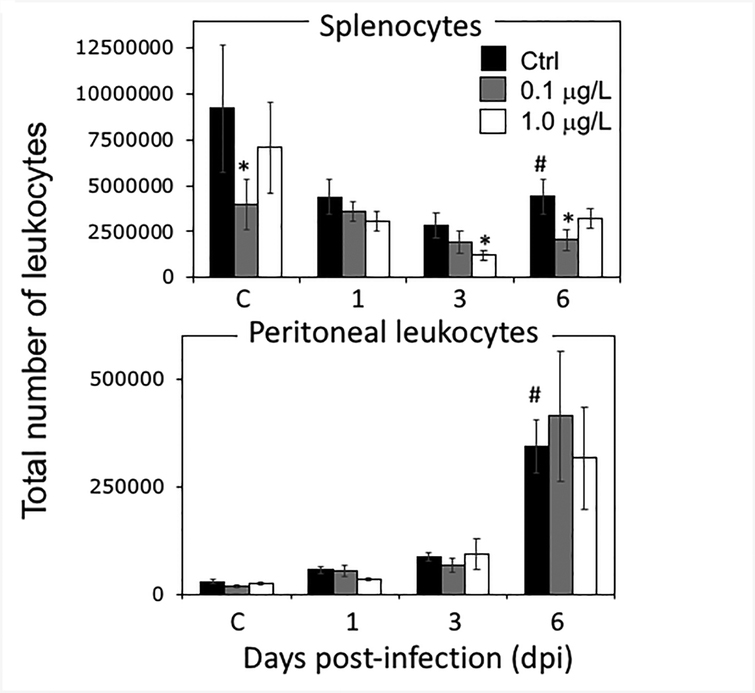

Since X. laevis do not have lymph nodes, the spleen is both the primary and main secondary immune organ. As such, we first examined the cellularity and composition of splenocytes in young adult frogs that were exposed to UOG mixture at tadpole stages and were sham-infected by i.p. injection of sterile APBS, which does not elicit detectable innate or adaptive immune responses compared to unmanipulated controls (De Jesus Andino et al., 2017; Morales et al., 2010; Morales and Robert, 2007). Consistent with a decreased whole-body weight, there was a decrease in the total number of cells recovered from the spleen in animals developmentally exposed to UOG chemicals, which was only statistically significant for the group treated with 0.1 μg/L of UOG chemicals (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Total number of leukocytes recovered from the spleen and peritoneal cavity from adult frogs that were exposed for three weeks at tadpole stages to 0.2 % ethanol (Ctrl; black) or 0.1 (gray) or 1 μg/L (white) of an equimass mixture of 23 UOG chemicals. After chemical exposure and metamorphosis completion, frogs were either i.p. injected with 1 ×106 pfu of FV3 or sham-infected with amphibian PBS (steady state), and then euthanized after 1, 3, or 6 days or sham-infected (C; steady state). Results are means ± SEM of 6 individuals per group from two different experiments (3 per experiment). * P <0.05 significant differences among treatment groups relative to the EtOH treated group; # P <0.05 determined between each corresponding mock-infected and FV3-infected treatment group. All the values were determined by one-way ANOVA test and Tukey’s post-hoc test (GraphPad Prism 6).

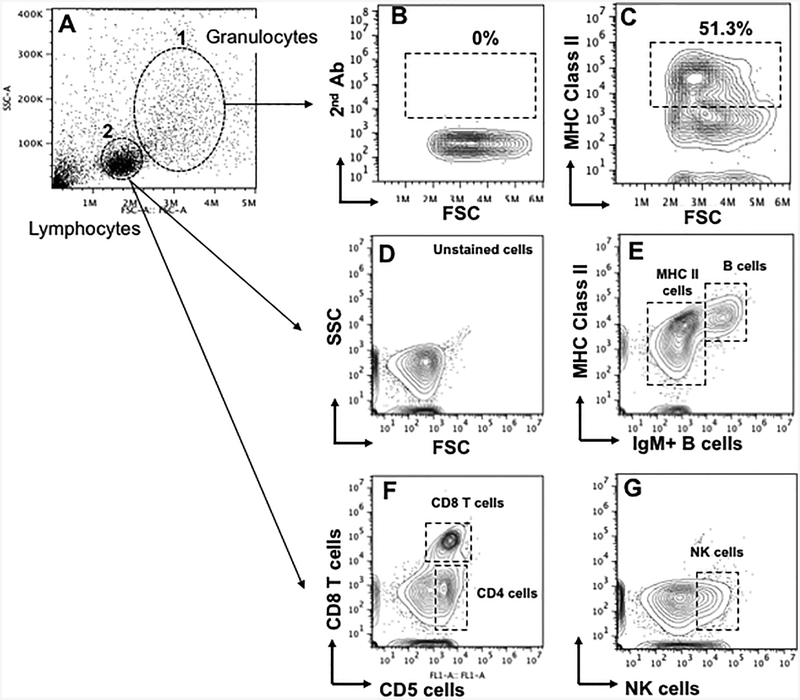

To determine whether particular leukocyte populations were affected, we conducted a flow cytometry analysis using availableX. laevis-specific monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) and the gating strategy depicted in Fig. 3. Cell of larger size and granularity corresponding to granulocytes were gated separately (Gate 1, Fig. 3). Although specific markers of innate immune cells of the myeloid lineage are lacking in Xenopus, we can obtain useful information be gating on non-lymphocyte events and MHC class II expression. This population was only minimally stained (1–5%) with T and B cell specific mAbs. Lymphocytes, forming a distinct population according to forward and side scatter, were gated out and further separated into total T cells with the anti-pan T cell marker CD5 recognized by 2B1 mAb, then further subdivided using the anti-CD8 mAb AM22 into CD8 (CD8+/CD5+) and putative CD4 or CD4-like (CD8neg/CD5+) cells as previously shown (Chida et al., 2011). B cells were detected from the lymphocyte gate with anti-Mu mAb 10A9 as IgM+ cells co-expressing the MHC class II marker recognized by the mAb AM20 (Flajnik et al., 1990). NK cells were also examined using the anti-NK cell marker 1F8 (Horton et al., 2000). As expected in adult frogs, all lymphocytes were positively stained with the anti-class II mAb. We used this gating strategy, to calculate the relative frequency and cell number of each of these populations.

Figure 3.

Flow cytometry gating strategy (Flowjo 7). (A) Representative FACS bit map from splenocytes of a single animal: Y-axis (SSC-A): side light scatter (cell granularity and density). X-axis (FSC-A): light scatter (cell size). Two major cell populations were gated: (1) Larger cells (M9, DCs, PMN). (2) Smaller lymphocytes (B and T cells). Splenocytes were stained with mAbs specific for (C) MHC class II; (E) IgM/class II; (F) CD5/CD8 to identify CD8 and CD4 T cells (CD5+/CD8neg; (G) NK cells mAb. A negative control (B) was included for each staining.

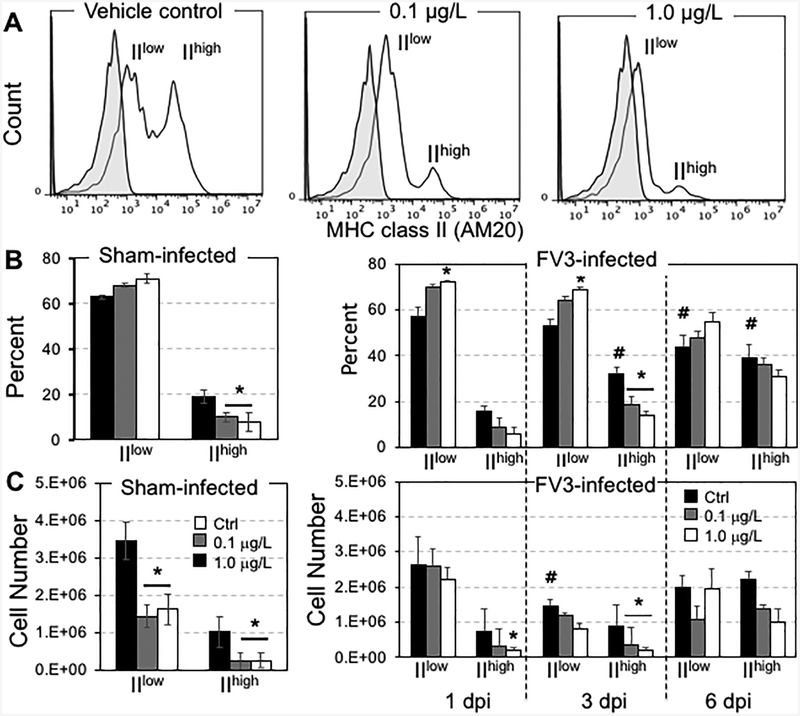

The splenic granulocyte populations of mock-treated animals segregated into two distinct MHC class IIlow and IIhigh subsets (Fig. 4A). Interestingly, the MHC class IIhigh subset was significantly ablated in animals developmentally exposed at either 0.1 or 1.0 μg/L dose to the UOG mixture, both in frequency and in cell number (sham-infected panel in Fig. 4B, C). The total number but not the frequency of MHC class IIlow cells was also diminished in treated groups.

Figure 4.

Effects of developmental exposure to an equimass mixture of 23 UOG chemicals on myeloid lineage cells at steady state (sham-infected) and during viral infection. (A) MHC class II surface expression by FACS on splenic granulocytes (gate 1) of frogs exposed to 0.2 % EtOH (Ctrl; black), 0.1 (gray) or 1.0 μg/L (white) of UOGs. (B) Frequencies (%) and (C) cell numbers of class IIhigh and class IIlow granulocytes from UOG exposed frogs either infected with 1 × 106 pfu of FV3 for 3 or 6 days, or sham-infected. These data are pools of 2 independent experiments (3 animals per group). * P <0.05 significant differences among treatment groups relative to the EtOH treated group; # P <0.05 significant differences determined between each corresponding mock-infected and FV3-infected treatment group. All the values were determined by one-way ANOVA test and Tukey’s post-hoc test (GraphPad Prism 6).

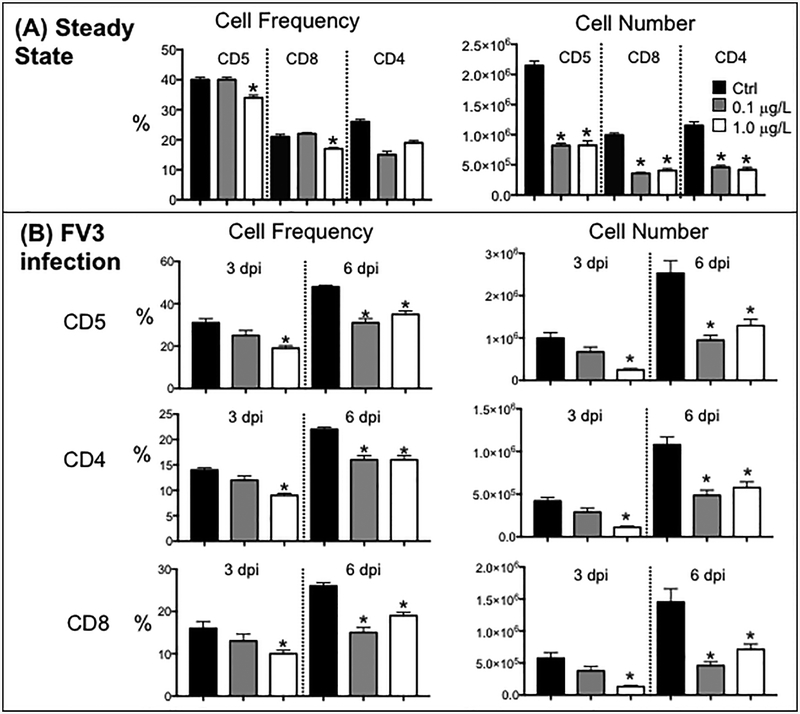

For splenic lymphocytes at steady state, in addition to a slight decreased frequency of B cells, CD5+ T cells and CD+8 T cells (mainly at the 1.0 μg/L dose), the relative numbers of all lymphocyte subsets, were considerably decreased in animals developmentally exposed to both doses of the UOG mixture (see Fig. 5A, 6A).

Figure 5.

Effects of developmental exposure to an equimass mixture of 23 UOG chemicals on T cells at steady state (sham-infected) (A) and during viral infection (B). Frequency (%) and relative number of splenic total (CD5+), CD8 (CD5+/CD8+/CD5) and CD4-like (CD5+/CD8neg) determined by flow cytometry (gate 2) in frogs exposed to 0.2 % ethanol (Ctrl; black) or 0.1(gray), and 1.0 μg/L (white) of UOGs. Xenopus-specific mAb used were: AM20 (class II); 2B1 (CD5); AM22 (CD8). After chemical exposure and metamorphosis, frogs were either i.p. injected with 1 × 106 pfu of FV3 or with amphibian PBS (Ctrl), and then euthanized after 3 and 6 d. Results are means ± SEM of 6 individuals per group from two different experiments (3 per experiment). * P <0.05 significant differences among treatment groups relative to the ethanol treated group; # P <0.05 significant differences for each infected group relative to uninfected controls. All the values were determined by one-way ANOVA test and Tukey’s post-hoc test (GraphPad Prism 6).

Figure 6.

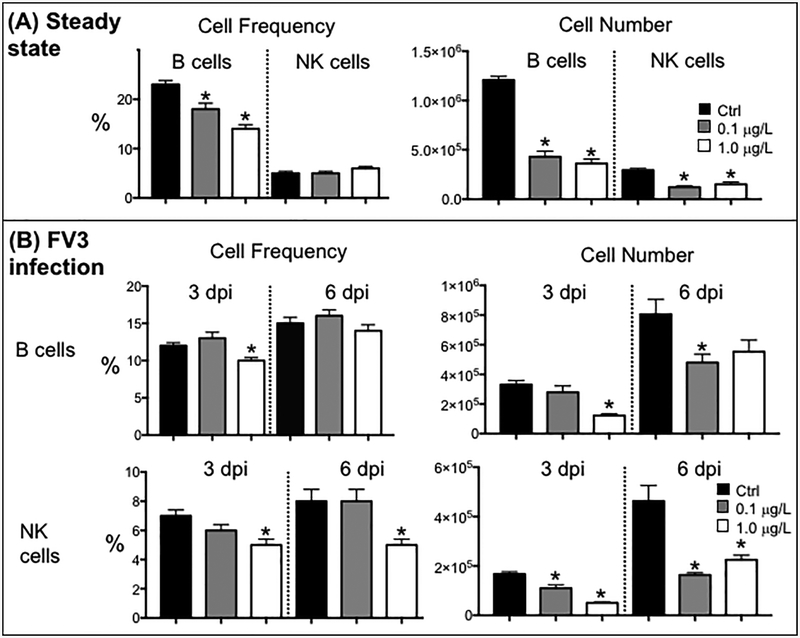

Effects of developmental exposure to an equimass mixture of 23 UOG chemicals on B and NK cells at steady state (sham-infected) (A) and during viral infection (B). Frequency and relative number of splenic IgM+ B cells and NK cells determined by flow cytometry (gate 2) in frogs developmentally exposed to 0.2 % ethanol (Ctrl; black) or 0.1 (gray) and 1.0 μg/L (white) of UOGs then either infected with FV3 for 3 or 6 days, or sham-infected. Xenopus-specific mAb used are: AM20 (class II); 10A9 (IgM); 1F8 (NK). These data are pools of 2 independent experiments (3 animals per group). * P <0.05 significant differences among treatment groups relative to the EtOH treated group; # P <0.05 significant differences for each infected group relative to uninfected controls. All the values were determined by one-way ANOVA test and Tukey’s post-hoc test (GraphPad Prism 6).

3.3. Effects o f developmental exposure to UOG chemicals on antiviral immune response in the spleen

To further investigate the potential impact of developmental exposure to UOG chemicals on the immune system, we assessed immune response during FV3 infection. Young adults that were exposed to 0.1 and 1.0 μg/L of UOG mixture at tadpole stages, were sham-infected or infected intraperitoneally with 1×106 pfu of FV3. Cellular immune gene and expression response were monitored at 3 and 6 days post-infection, which corresponds to early mainly innate and at the peak of adaptive immune response, respectively.

Since in Xenopus the spleen functions both as a primary and secondary lymphoid organ, we first monitored the changes in frequencies and relative numbers of the different cell types by flow cytometry. For the sham-treated 0.2% ethanol exposed control group, antiviral immune response was characterized by an increase frequency of class IIlow granulocytes at 3 and 6 dpi and a decrease number of class IIhigh cells at 3 dpi (FV3-infected right panel Fig. 4 B, C; statistical significance indicated by #). Interestingly, exposure to 0.1 μg/L and 1.0 μg/L dose of UOG chemicals resulted in a significant deficit in both frequency and numbers of class IIlow granulocytes at 3 dpi when compared to infected 0.2% ethanol exposed controls (Fig. 4B, C; statistical significance indicated by *). It is noteworthy that this defect occurred before the peak of the adaptive antiviral response in kidneys (Morales and Robert, 2007).

An efficient T cell response, especially CD8 cytotoxic T cells, is critical for viral clearance during a FV3 primary infection (Morales and Robert, 2007; Robert et al., 2005). Therefore, we examined in detail the changes in frequency and cells number of total (CD5+), CD8 and CD4-like T cells in the spleen in infected animals at 3 and 6 dpi (Fig. 5B). Notably, the basal deficit in frequency and numbers of the three different splenic T cell populations resulting from developmental exposure to both doses of the UOG mixture was accentuated during FV3 infection. The defect was already notable at 3 dpi for animals developmentally exposed at the higher 1.0 μg/L doses of UOG mixture. Whether this was due to a lower T cell expansion and/or recruitment in the spleen that functions as the main immune site, remains to be determined. Developmental exposure to UOG chemicals also impaired the kinetics of NK cell response in the spleen at 6 dpi compared to EtOH treated controls, whereas B cell alteration was most notable at 3 dpi and for the 1.0 μg/L group (Fig. 6B).

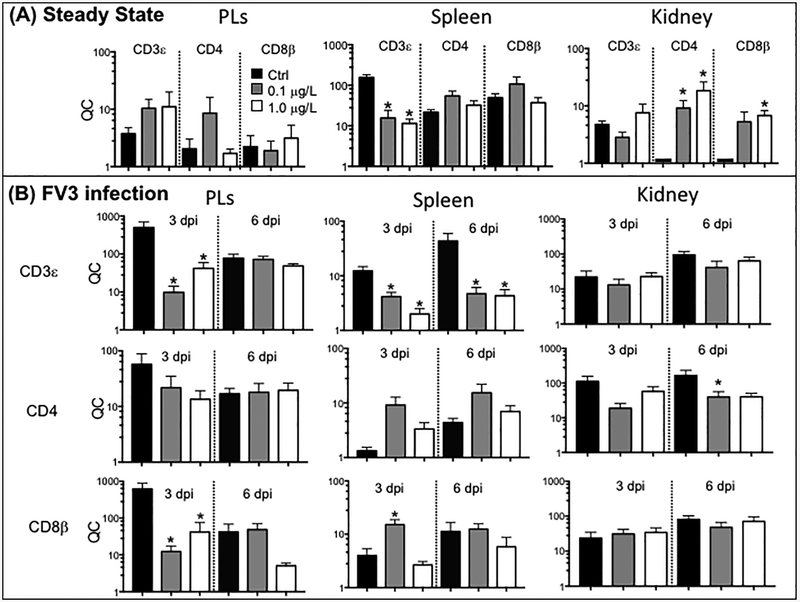

To further examine the T cell function at steady state (sham-infection) as well as the antiviral T cell response at the site of infection (peritoneal cavity) and at the main site of viral replication (kidney), we determined the relative expression of the key T cell co-receptors CD3ε, CD4 and CD8α (Fig. 7). Interestingly, the basal CD3ε gene expression in the sham-infected group was significantly reduced in the spleen, whereas abnormally high levels of CD4 and CD8β transcripts were detected in kidneys (Fig. 7A). Upon FV3 infection, the expression of the 3 genes markedly increased at 3 dpi in PLs, as well as in kidneys where they remained elevated at 6 dpi. In contrast, there was a drop (10× on average) in the expression of these three T cell genes in the spleen at 3 dpi and to a lesser extent at 6 dpi compared to uninfected controls (Fig. 7B). Notably, developmental exposure to both 0.1 and 1.0 μg/L of the UOG chemical mixture negatively affected the CD8β gene expression in PLs at 3 dpi. This was also reflected by a similar decrease in CD3ε gene expression, whereas CD4 transcript levels did not show significant alteration. In spleen, gene expression profiling revealed mainly a defect in CD3s expression. In kidneys, no further alteration of gene expression was detected during FV3 infection (Fig. 7B).

Figure 7.

Effects of developmental exposure to UOG chemicals on relative expression of T cell co-receptor CD3, CD4 and CD8 genes at steady state (sham-infected) (A) and during viral infection (B). Relative expression of CD3, CD4 and CD8 genes from the peritoneum, spleen and kidney tissues was determined for adult frogs developmentally exposed to either 0.2% ethanol (Ctrl; black), 0.1 (gray) or 1.0 μg/L (white) of the UOG mixture. After chemical exposure and metamorphosis completion, frogs were either sham-infected or i.p. infected with 1 × 106 pfu of FV3, for 3 and 6 days. Results are means ± SEM of 6 individuals per group from two different experiments (3 per experiment). Gene expression is represented as fold increase (RQ: relative quantification) relative to GAPDH endogenous control. Statistical significance was assessed by Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric test and Dunn’s multiple comparison test: (*) P<0.05 between control and treated groups.

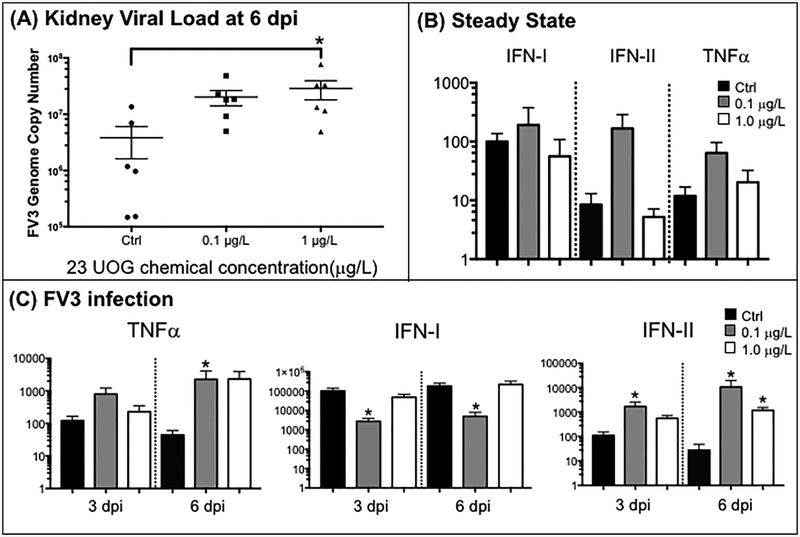

3.4. Effects o f developmental exposure to UOG chemicals on antiviral immune response in the kidneys

To obtain further evidence of the long-term impact of developmental exposure to the mixture of UOG chemicals on antiviral immune response, we monitored the expression of a selected set of genes relevant for innate and adaptive immunity in the kidneys. For a number of genes tested involved in innate immune response (e.g., IL-1β or IL-10), the differential expression at steady state and during FV3 infection was not significantly different among treatment groups (Fig. 8A; Table S2). However, the expression response of several genes important for antiviral response was perturbated. Notably, FV3-elicited type I IFN gene expression was significantly reduced at both 3 and 6 dpi in in the kidneys of adult frogs that had been developmentally exposed to the low dose (0.1 μg/mL) of the UOG chemical mixture (Fig. 8C). In contrast, there was an exacerbated gene expression of type II IFN or IFNγ at 3 and 6 dpi and of the pro-inflammatory TNFa at 6 dpi in frogs developmentally exposed to both doses of the UOG mixture (Fig. 8B).

Figure 8.

Effects of developmental exposure to UOG chemicals on viral load (A) as well as relative expression of TNFα, Type I and II IFN genes in kidneys at steady state (sham-infected) (B) and during viral infection (C). (A) FV3 genome copy numbers in kidneys of infected adult frogs at 6 dpi that were developmentally exposed to either 0.2% ethanol (Ctrl; black), 0.1 (gray) or 1.0 μg/L (white) UOG mixture. For each group, the viral genome copy number of each individual determined by absolute qPCR is depicted by different symbol as well as a horizontal barre indicating the average ±SD. Statistical significance: ** P<0.005 (Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric test and Dunn’s multiple comparison test). (B, C) The relative expression of TNFa, Type I and II IFN genes in kidney was determined for adult frogs developmentally exposed to either 0.2% ethanol (Ctrl), 0.1 or 1.0 μg/L of the UOG mixture and either sham-infected or i.p. infected with 1 × 106 pfu of FV3 for 3 and 6 days. Results are means ± SEM of 6 individuals per group from two different experiments (3 per experiment). Gene expression is represented as fold increase (RQ: relative quantification) relative to GAPDH endogenous control. Statistical significance assessed by Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric test and Dunn’s multiple comparison test: (*) P<0.05 between control and treated groups.

Finally, we assessed whether the alterations of immune response resulting from developmental exposure to the UOG chemical mixture had any consequence in controlling FV3 replication by determining the viral loads. In kidneys, the main site of FV3 replication, viral loads were significantly increased at 6 dpi in frogs developmentally exposed to the high dose (1 μg/L) of the UOG chemical mixture compared to EtOH exposed controls (Fig 8B). The lower viral genome copy numbers in other tissues including the spleen were not significantly different among the different groups (Table S2).

4. Discussion

In this study we show that the Xenopus model system we have developed with FV3 as viral pathogen is reliable and very sensitive for assessing the long-term negative impacts on immune function resulting from exposure during early life to water EDC pollutants associated with UOG activity. Our data provide strong evidence that at concentrations well below or at the level found in water where UOG activity occurs (Energy Information Administration, 2016; Kassotis et al., 2016c), a mixture of UOG chemicals can induce alterations of the immune system that persists for a long time after exposure. Thus, early life exposure leads to change in adulthood that include weakened host resistance to viral pathogens. These results are relevant and raise concern for aquatic vertebrates near UOG sites or downstream from UOG waste water spills. However, owing to the conservation of the immune system across all jawed vertebrates these findings also clearly pertain to human health.

Given that each of these 23 UOG chemicals has been selected because of their EDC activity in vitro, it is not really surprising that exposure to a mixture of these chemicals can perturb the overall amphibian development. Indeed, effects on metamorphic development have been reported following exposure to EDCs in Xenopus (Fini et al., 2012). Given the multiple sources of variability (geography, half-life, concentrations of the various chemicals, time of release, etc.), a defined equimass mixture of these 23 chemicals has been used as a titratable, more controllable and reliable source of contaminants than raw contaminated water from UOG sites. Using this defined UOG mixture, we found that animals exposed to 1 μg/L and even 0.1 μg/L of the mixture, despite being raised in clean water for months, exhibited persisting developmental alterations characterized by a significant weight loss at the end of metamorphosis. A low weight just after metamorphosis is likely to negatively impact their overall fitness. Even more striking, was the reduction in the number of immune cells of the spleen of adult frogs that were exposed to the UOG mixture at postembryonic stages. Although this decrease was only statistically significant at 0.1 μg/L, the trend was similar at 1 μg/L and affected most cell types of splenic immune cells including myeloid and lymphoid lineage cells. To which extend this lack of strict dose dependent effects of developmental exposure to the UOG mixture is real or just due to high individual variations is unclear. It is to note, however, that non-linear responses are a commonly known attribute of EDCs (Vandenberg et al., 2012). To which extent this immune cell deficit is related to the overall weight loss of animals developmentally exposed to UOG chemicals is unknown. It is also currently unclear whether this decrease in splenic leukocytes/lymphocytes results from a differentiation defect since the spleen is a major lymphoid organ and/or an alteration of immune cell trafficking in the whole organism. Our data are consistent with both possibilities, because we see a decrease in steady state immune cells as well as decreases in responding lymphocytes that are activated in response to the virus. Nevertheless, developmental exposure to the UOG chemical mixtures induced other persisting immune specific alterations at steady state.

Notably, the fraction of innate immune cells expressing high amount of MHC class II molecules at the cell surface was markedly depleted in developmentally treated frogs. In mammals, MHC class II is typically expressed by professional immune cells such as dendritic cells (DCs), monocytes and macrophages. Moreover, the level of MHC class II at the cell surface rapidly increase upon activation by inflammatory stimuli (reviewed in (Holling et al., 2004; Unanue et al., 2016)). As such, the level of MHC class II can serve as a marker of cell activation. In X. laevis, cells of the myeloid lineage including monocytes, macrophages and neutrophils also express surface MHC class II (Du Pasquier and Flajnik, 1990; Edholm, 2018; Rollins-Smith and Blair, 1990). Although little is still little known about DCs in Xenopus, a subset of splenic immune cells named XL cells has recently been characterized that exhibit dual DC and follicular Dendritic (FDCs) characteristics, and that expresses high level of MHC class II (Neely et al., 2018). Furthermore, indirect evidence suggests that as in mammals, there is increased MHC class II surface expression on activated splenic leukocytes (macrophage and putative DCs) during an immune response (Morales et al., 2010). Thus, the marked decline in the innate cell population expressing a high level of MHC class II may indicate some impairment in leukocyte activation. The persistence of lower frequency and number of MHC class IIhigh leukocytes in the spleen following viral infection further supports this possibility. A less effective activation of these innate cell effectors may have negative impact not only on antiviral innate immune response (e.g., production of inflammatory cytokines) but also on the adaptive immune response by reducing antigen presentation and co-stimulation, which ultimately would delay or decrease B and T lymphocyte activation.

Consistent with this, our data indicate that developmental exposure to UOG chemicals resulted in multiple T cell functional deficits. The lower frequency and number of T cells at 6 dpi in the spleen strongly suggests a defect in T cell expansion, which would be consistent with a poor T cell activation by APCs. Lymphocyte expansion in the spleen during FV3 infection is also well documented (Morales and Robert, 2007). While the role of CD4 T cells in antiviral immunity is currently unknown, CD8 T cells that are crucial for viral clearance during a primary infection with FV3 (Morales and Robert, 2007; Robert et al., 2005). Besides an impaired activation in the spleen, our data also suggest an alteration in T cell recruitment at the site of infection. This is based on the relative levels of CD3, CD4 and CD8β receptor transcripts used as proxy to detect total, CD4 and CD8 T cells. The change of expression of these genes in the spleen is overall consistent with the flow cytometry indicating a poor T cell activation and/or expansion, which provide some validity for the approach. Notably, our qPCR data suggest that there was delay in infiltration of CD8 T cells at 3 dpi in UOG-treated compared to sham-exposed controls. In kidneys, where viral replication is the most prominent, although little difference was observed with regards to T cell occurrence, altered expression of several cytokine encoding genes was observed. Interestingly, IFNγ gene expression response to FV3 infection appeared to be exacerbated in animals developmentally exposed to both doses of UOG chemicals. This again suggests some deregulation of the T cell response. Owing to the demonstrated importance of CD8 T cell as well as innate-like T cells in anti-FV3 response, it will be useful in future experiments to determine the expression of classical MHC class I and MHC class I-like (Edholm et al., 2013).

In addition to T cells, developmental exposure to UOG chemicals had also lasting negative effects on NK and B cell responses in the spleen. Owing to the lack of information about their development and function, it is unclear whether the lower frequency and number of NK cells during FV3 infection in animal developmentally exposed to 1 μg/L of UOG chemicals is due to an impairment of their differentiation or their recruitment in the spleen. Concerning B cells, their significant lower frequency and number at 3 dpi suggests a reduced B cell response to FV3 in UOG treated animals, which could be related to an ineffective activation as discussed for T cells. It will be interesting in future experiments to assess the isotypes, magnitude and affinity of antibodies produced during primary and secondary FV3 infection. While there is a B cell response during primary FV3 infections, the thymus-dependent switch from IgM to IgY antibody and the production of high titer of neutralizing IgY in the serum occurs mainly during a secondary FV3 infection (Maniero et al., 2006).

Aquatic vertebrates and human populations are exposed to an increasing number of EDC water pollutants, whose potential long-term harmful effects on immune function are unclear and understudied. The relative sensitivity of Xenopus to waterborne contaminants compared to mice and human is a complex issue since for some chemicals (e.g. TCDD; (Lavine et al., 2005)), Xenopus is less sensitive than mouse, whereas Xenopus is more sensitive than mammals and fish for other chemicals (e.g., phenols; (Lavine et al., 2005)), In addition, amphibians can adapt and become more resistant to a certain pollutants (Hua et al., 2015; Lavine et al., 2005). Nevertheless, while more work will be needed to define the molecular and cellular pathways targeted by mixtures of EDCs derived from UOG activity, our results provide unequivocal evidence of the long term negative impacts on immune function and immune defenses to pathogens that short perinatal exposure to these water pollutants can induce.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Effects of unconventional oil and gas mixture of chemicals (UOG) in Xenopus are presented

Developmental exposure to 23 UG chemicals (UOG-mix) affects adult frog immunity in adult frogs

UOG-mix alters immune adult frog homeostasis

UOG-mix applied to tadpoles weakens frog antiviral immunity after metamorphosis

Acknowledgements

We thank Tina Martin for animal husbandry.

Funding information

We thank Tina Martin for animal husbandry. This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases at the National Institutes of Health (grant number: R24-AI-059830), the National Science Foundation (grant number: IOS-1754274) and a Pilot Project Grant from the Rochester Environmental Health Sciences Center (P30-ES01247). C. M. is supported by the Toxicology Program (T32-ES07026).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bandin I, Dopazo CP, 2011. Host range, host specificity and hypothesized host shift events among viruses of lower vertebrates. Vet Res 42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bansal A, Henao-Mejia J, Simmons RA, 2018. Immune System: An Emerging Player in Mediating Effects of Endocrine Disruptors on Metabolic Health. Endocrinology 159, 32–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blom JMC, Ottaviani E, 2017. Immune-Neuroendocrine Interactions: Evolution, Ecology, and Susceptibility to Illness. Medical science monitor basic research 23, 362–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boule LA, Chapman T, Hillman S, Balise V, O’Dell C, Robert J, Georas S, Nagel S, Lawrence P, 2018. Developmental exposure to a mixture of 23 chemicals associated with unconventional oil and gas operations alters the immune system of mice. Tox Sci In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boule LA, Lawrence BP, 2016. Influence of early life environmental exposures on immune function across the lifespan, in: Esser C (Ed.), Environmental Influences on the Immune System. Springer, pp. 21–54. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter DO, 2016. Hydraulic fracturing for natural gas: impact on health and environment. Reviews on environmental health 31, 47–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey JA, Savitz DA, Rasmussen SG, Ogburn EL, Pollak J, Mercer DG, Schwartz BS, 2016. Unconventional Natural Gas Development and Birth Outcomes in Pennsylvania, USA. Epidemiology 27, 163–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G, Robert J, 2011. Antiviral immunity in amphibians. Viruses 3, 2065–2086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chida AS, Goyos A, Robert J, 2011. Phylogenetic and developmental study of CD4, CD8 alpha and beta T cell co-receptor homologs in two amphibian species, Xenopus tropicalis and Xenopus laevis. Dev Comp Immunol 35, 366–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinchar VG, 2002. Ranaviruses (family Iridoviridae): emerging cold-blooded killers. Archives of virology 147, 447–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinchar VG, Hyatt A, Miyazaki T, Williams T, 2009. Family Iridoviridae: Poor Viral Relations No Longer. Curr Top Microbiol 328, 123–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cozzarelli IM, Skalak KJ, Kent DB, Engle MA, Benthem A, Mumford AC, Haase K, Farag A, Harper D, Nagel SC, Iwanowicz LR, Orem WH, Akob DM, Jaeschke JB, Galloway J, Kohler M, Stoliker DL, Jolly GD, 2017. Environmental signatures and effects of an oil and gas wastewater spill in the Williston Basin, North Dakota. The Science of the total environment 579, 1781–1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosby LM, Tatu CA, Varonka M, Charles KM, Orem WH, 2018. Toxicological and chemical studies of wastewater from hydraulic fracture and conventional shale gas wells. Environ Toxicol Chem 37, 2098–2111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jesus Andino F, Chen G, Li Z, Grayfer L, Robert J, 2012. Susceptibility of Xenopus laevis tadpoles to infection by the ranavirus Frog-Virus 3 correlates with a reduced and delayed innate immune response in comparison with adult frogs. Virology 432, 435–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jesus Andino F, Chen G, Li Z, Grayfer L, Robert J, 2012. Susceptibility of Xenopus laevis tadpoles to infection by the ranavirus Frog-Virus 3 correlates with a reduced and delayed innate immune response in comparison with adult frogs. Virology 432, 435–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jesus Andino F, Lawrence BP, Robert J, 2017. Long term effects of carbaryl exposure on antiviral immune responses in Xenopus laevis. Chemosphere 170, 169–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiGiulio DC, Jackson RB, 2016. Impact to Underground Sources of Drinking Water and Domestic Wells from Production Well Stimulation and Completion Practices in the Pavillion, Wyoming, Field. Environ Sci Technol 50, 4524–4536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Pasquier L, Flajnik MF, 1990. Expression of MHC class II antigens during Xenopus development. Dev Immunol 1, 85–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edholm ES, 2018. Flow Cytometric Analysis of Xenopus Immune Cells. Cold Spring Harbor protocols 2018 , pdb.prot097600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edholm ES, Albertorio Saez LM, Gill AL, Gill SR, Grayfer L, Haynes N, Myers JR, Robert J, 2013. Nonclassical MHC class I-dependent invariant T cells are evolutionarily conserved and prominent from early development in amphibians. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110, 14342–14347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsner M, Hoelzer K, 2016. Quantitative Survey and Structural Classification of Hydraulic Fracturing Chemicals Reported in Unconventional Gas Production. Environ Sci Technol 50, 3290–3314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Energy Information Administration, U.S., 2016. Dry Shale Gas Production. [Google Scholar]

- Fini JB, Riu A, Debrauwer L, Hillenweck A, Le Mevel S, Chevolleau S, Boulahtouf A, Palmier K, Balaguer P, Cravedi JP, Demeneix BA, Zalko D, 2012. Parallel biotransformation of tetrabromobisphenol A in Xenopus laevis and mammals: Xenopus as a model for endocrine perturbation studies. Toxicol Sci 125, 359–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flajnik MF, Ferrone S, Cohen N, Du Pasquier L, 1990. Evolution of the MHC: antigenicity and unusual tissue distribution of Xenopus (frog) class II molecules. Molecular immunology 27, 451–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gantress J, Maniero GD, Cohen N, Robert J, 2003. Development and characterization of a model system to study amphibian immune responses to iridoviruses. Virology 311, 254–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer AL, Berrill M, Wilson PJ, 2005. Five amphibian mortality events associated with ranavirus infection in south central Ontario, Canada. Diseases of aquatic organisms 67, 9–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross SA, Avens HJ, Banducci AM, Sahmel J, Panko JM, Tvermoes BE, 2013. Analysis of BTEX groundwater concentrations from surface spills associated with hydraulic fracturing operations. Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association (1995) 63, 424–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holling TM, Schooten E, van Den Elsen PJ, 2004. Function and regulation of MHC class II molecules in T-lymphocytes: of mice and men. Human immunology 65, 282–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton TL, Minter R, Stewart R, Ritchie P, Watson MD, Horton JD, 2000. Xenopus NK cells identified by novel monoclonal antibodies. European journal of immunology 30, 604–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua J, Jones DK, Mattes BM, Cothran RD, Relyea RA, Hoverman JT, 2015. The contribution of phenotypic plasticity to the evolution of insecticide tolerance in amphibian populations. Evolutionary applications 8, 586–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacques R, Edholm ES, Jazz S, Odalys TL, Francisco JA, 2017. Xenopus-FV3 host-pathogen interactions and immune evasion. Virology 511, 309–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jancovich JK, Bremont M, Touchman JW, Jacobs BL, 2010. Evidence for Multiple Recent Host Species Shifts among the Ranaviruses (Family Iridoviridae). J Virol 84, 2636–2647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassotis CD, Alvarez DA, Taylor JA, vom Saal FS, Nagel SC, Tillitt DE, 2015a. Characterization of Missouri surface waters near point sources of pollution reveals potential novel atmospheric route of exposure for bisphenol A and wastewater hormonal activity pattern. The Science of the total environment 524–525, 384–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassotis CD, Bromfield JJ, Klemp KC, Meng CX, Wolfe A, Zoeller RT, Balise VD, Isiguzo CJ, Tillitt DE, Nagel SC, 2016a. Adverse Reproductive and Developmental Health Outcomes Following Prenatal Exposure to a Hydraulic Fracturing Chemical Mixture in Female C57Bl/6 Mice. Endocrinology 157, 3469–3481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassotis CD, Iwanowicz LR, Akob DM, Cozzarelli IM, Mumford AC, Orem WH, Nagel SC, 2016b. Endocrine disrupting activities of surface water associated with a West Virginia oil and gas industry wastewater disposal site. The Science of the total environment 557–558, 901–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassotis CD, Klemp KC, Vu DC, Lin CH, Meng CX, Besch-Williford CL, Pinatti L, Zoeller RT, Drobnis EZ, Balise VD, Isiguzo CJ, Williams MA, Tillitt DE, Nagel SC, 2015b. Endocrine-Disrupting Activity of Hydraulic Fracturing Chemicals and Adverse Health Outcomes After Prenatal Exposure in Male Mice. Endocrinology 156, 4458–4473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassotis CD, Tillitt DE, Davis JW, Hormann AM, Nagel SC, 2014. Estrogen and androgen receptor activities of hydraulic fracturing chemicals and surface and ground water in a drilling-dense region. Endocrinology 155, 897–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassotis CD, Tillitt DE, Lin CH, McElroy JA, Nagel SC, 2016c. Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals and Oil and Natural Gas Operations: Potential Environmental Contamination and Recommendations to Assess Complex Environmental Mixtures. Environ Health Perspect 124, 256–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinney KS, Cohen N, 2009. Neural-immune system interactions in Xenopus. Frontiers in bioscience (Landmark edition) 14, 112–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo CH, Yang SN, Kuo PL, Hung CH, 2012. Immunomodulatory effects of environmental endocrine disrupting chemicals. The Kaohsiung journal of medical sciences 28, S37–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavine JA, Rowatt AJ, Klimova T, Whitington AJ, Dengler E, Beck C, Powell WH, 2005. Aryl hydrocarbon receptors in the frog Xenopus laevis: two AhR1 paralogs exhibit low affinity for 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD). Toxicol Sci 88, 60–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maniero GD, Morales H, Gantress J, Robert J, 2006. Generation of a long-lasting, protective, and neutralizing antibody response to the ranavirus FV3 by the frog Xenopus. Dev Comp Immunol 30, 649–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales HD, Abramowitz L, Gertz J, Sowa J, Vogel A, Robert J, 2010. Innate immune responses and permissiveness to ranavirus infection of peritoneal leukocytes in the frog Xenopus laevis. J Virol 84, 4912–4922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales HD, Robert J, 2007. Characterization of primary and memory CD8 T-cell responses against ranavirus (FV3) in Xenopus laevis. J Virol 81, 2240–2248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrdjen I, Lee J, 2015. High volume hydraulic fracturing operations: potential impacts on surface water and human health. International journal of environmental health research, 1–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neely HR, Guo J, Flowers EM, Criscitiello MF, Flajnik MF, 2018. “Double-duty” conventional dendritic cells in the amphibian Xenopus as the prototype for antigen presentation to B cells. European journal of immunology 48, 430–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwkoop P, Faber J, 1967. Normal table of Xenopus laevis (Daudin) : a systematical and chronological survey of the development from the fertilized egg till the end of metamorphosis, 2 ed, Amsterdam: North Holland. [Google Scholar]

- Quatrini L, Vivier E, Ugolini S, 2018. Neuroendocrine regulation of innate lymphoid cells. Immunol Rev 286, 120–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert J, McGuire CC, Kim F, Nagel SC, Price SJ, Lawrence BP, De Jesus Andino F, 2018. Water Contaminants Associated With Unconventional Oil and Gas Extraction Cause Immunotoxicity to Amphibian Tadpoles. Toxicol Sci 166, 39–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert J, Morales H, Buck W, Cohen N, Marr S, Gantress J, 2005. Adaptive immunity and histopathology in frog virus 3-infected Xenopus. Virology 332, 667–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert J, Ohta Y, 2009. Comparative and developmental study of the immune system in Xenopus. Developmental dynamics : an official publication of the American Association of Anatomists 238, 1249–1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollins-Smith LA, Blair P, 1990. Expression of class II major histocompatibility complex antigens on adult T cells in Xenopus is metamorphosis-dependent. Dev Immunol 1, 97–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapouckey SA, Kassotis CD, Nagel SC, Vandenberg LN, 2018. Prenatal Exposure to Unconventional Oil and Gas Operation Chemical Mixtures Altered Mammary Gland Development in Adult Female Mice. Endocrinology 159, 1277–1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sifkarovski J, Grayfer L, De Jesus Andino F, Lawrence BP, Robert J, 2014. Negative effects of low dose atrazine exposure on the development of effective immunity to FV3 in Xenopus laevis. Dev Comp Immunol 47, 52–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unanue ER, Turk V, Neefjes J, 2016. Variations in MHC Class II Antigen Processing and Presentation in Health and Disease. Annu Rev Immunol 34, 265–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenberg LN, Colborn T, Hayes TB, Heindel JJ, Jacobs DR Jr., Lee DH, Shioda T, Soto AM, vom Saal FS, Welshons WV, Zoeller RT, Myers JP, 2012. Hormones and endocrine-disrupting chemicals: low-dose effects and nonmonotonic dose responses. Endocrine reviews 33, 378–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vengosh A, Jackson RB, Warner N, Darrah TH, Kondash A, 2014. A critical review of the risks to water resources from unconventional shale gas development and hydraulic fracturing in the United States. Environ Sci Technol 48, 8334–8348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waxman HA, Markey EJ, DeGette D, 2011. Chemicals Used in Hydraulic Fracturing. US House of Representatives Council Committee on Energy and Commerce Minority Staff Report. [Google Scholar]

- Webb E, Bushkin-Bedient S, Cheng A, Kassotis CD, Balise V, Nagel SC, 2014. Developmental and reproductive effects of chemicals associated with unconventional oil and natural gas operations. Reviews on environmental health 29, 307–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkin RT, Digiulio DC, 2010. Geochemical impacts to groundwater from geologic carbon sequestration: controls on pH and inorganic carbon concentrations from reaction path and kinetic modeling. Environ Sci Technol 44, 4821–4827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.