Abstract

Background

Although China is undergoing rapid economic development, it is facing an ageing population. No data exists on malnutrition risks of older adults in an affluent Chinese society. The aim of this study is to examine these risks and identify their associated factors among home-living older Chinese adults in Hong Kong.

Methods

This is a cross-sectional study, to which home-living subjects aged 60 or above were recruited, between May and September 2017, from a non-governmental community organisation located in three different districts of Hong Kong. Nutritional status was assessed by the Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA), and its associated factors examined included socio-demographic characteristics, lifestyle, health status and diet. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed to identify factors associated with malnutrition risks (MNA < 24).

Results

Six hundred thirteen subjects (mean age: 78.5 ± 7.4; 54.0% females) completed the survey. Nearly 30% (n = 179) were at risk of malnutrition. By multivariable logistic regression, subjects (1) whose vision was only fair or unclear, (2) with poor usual appetite and (3) with main meal skipping behaviour had significantly higher malnutrition risk (all p < 0.05).

Conclusions

In this affluent Chinese society, the malnutrition risk in older adults is close to the global average, which is a matter for much concern. Interventions are therefore warranted that target vulnerable groups with poor vision, appetite, and meal skipping behaviour.

Trial registration

Not applicable.

Keywords: Malnutrition, Mini nutritional assessment, Community-dwelling older adults, Well-developed society, Chinese

Background

Malnourished older people have poorer functional status [1–3], longer hospital stays [4–7], and increased readmissions [4], morbidity [5] and mortality [4–7]. Early nutritional screening with community interventions would help to identify older adults at risk of malnutrition and improve their nutritional status in a timely manner [8].

Previous literature has identified various risk factors of malnutrition in the community of older adults. Certain socio-demographic characteristics are associated with that risk: older age [9–17], female sex [9, 10, 15, 16, 18, 19], unmarried [16, 20], low education level [10, 12, 16, 18, 19, 21], unemployment [19], low income [18, 21], living alone [12, 19], lifestyle choices including smoking [22] and less physical activity [21], health status including comorbidity [11], the use of dentures [23], chewing difficulty [20, 24, 25] and poor appetite [25, 26]. Although other factors such as alcohol intake [14, 22] and financial support [15, 18, 19] have been investigated, the findings are inconsistent. The relationship between visual or hearing impairment, which is common in older people, and malnutrition are less studied. As for dietary factors, older adults with decreased food intake and fewer meals [13], difficulty in food preparation [27, 28], and less consumption of fruit and vegetables [17, 20, 29, 30], meat [17, 29], milk [30] and other fluids [29] are more prone to malnutrition. However, the relationship between adherence to local dietary guidelines, or dietary behaviour such as meal skipping and food preferences and malnutrition, have been less investigated.

Because of the one-child policy [31], China is facing the problem of an ageing population, with about 30% projected to be older people aged above 60 by 2050 [32]. Among 1.4 billion Chinese, one-fifth of the world’s population, only a few studies exist studying malnutrition [11, 33]. Using Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA), Han et al. found about 44% of the community Chinese older adults either at risk, or already suffering from malnutrition [11], while Ji et al. identified about 76% of those aged 90 and over were at risk of malnutrition [33]. However, these previous studies were conducted in developing cities. The more affluent cities in China with gross domestic over US$300 billion, such as Hong Kong and other Tier 1 cities, share many similarities with developed countries, such as a smaller family structure and physical inactivity, which may worsen the malnutrition problem. With rapid economic growth in China, a study from an affluent Chinese society is needed to serve as a model for the rapidly developing and ageing future society in mainland China. The aim of this study is therefore to examine the malnutrition risk and identify its associated factors in home-living older Chinese adults in Hong Kong.

Methods

Study design and population

This is a cross-sectional survey of the home-living old-age population in Hong Kong. Subjects were recruited through a large registered charitable non-governmental organisation (NGO), in three districts covering nearly one-seventh of the population in Hong Kong. The eligible criteria were (1) aged 60 or above [34], (2) living at home and (3) able to communicate in Chinese. Those with diseases including cognitive impairment were also invited so that the result from this study was representative to the home-living older population where comorbidity is a common issue [35]. By convenience sampling, eligible subjects were contacted by NGO staff by phone for recruitment. Face-to-face interviews were conducted in various community centres or the subjects’ homes by trained NGO social workers and university nursing students from May to September 2017.

Ethics

This study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was obtained from the Survey and Behavioural Research Ethics Committee of the Chinese University of Hong Kong. During the recruitment, eligible subjects were contacted by the NGO staff to ensure confidentiality. They received an information sheet with the details of the study, their rights regarding participation and withdrawal at any stage. They were informed that the survey would be completed anonymously. Those who were interested in participating were requested to sign the consent form. Approval for the use of certain instruments in the study was obtained before data collection.

Measurement

The survey comprised five sections: nutritional status, socio-demographic characteristics, lifestyle choices, health status and dietary factors.

Nutritional status

The MNA was used to assess the global nutritional staus [36], as recommended by the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) [37]. It is an 18-item instrument covering in four sections: anthropometric assessment (weight, height, arm and calf circumference and weight loss), general assessment (lifestyle, medication, stress, mobility, neuro-psychological problems and skin lesion), dietary assessment (number of meals, food and fluid intake, and mode of feeding) and subjective assessment (perceived health and nutritional status) [36]. A booklet with detailed procedures for anthropometric measurement according to the MNA user guide [38] was provided to aid the measurement of the subjects by the interviewers. The MNA score ranges from 0 to 30, with 24–30 points representing normal nutritional status, 17–23.5 representing a risk of malnutrition, and less than 17 points representing malnourishment [36]. The MNA shows good diagnostic ability, with sensitivity of 0.96, specificity of 0.98 and positive predictive value of 0.97, compared with clinical status determined by physician using anthropometric, clinical, biological and dietary parameters [36, 39]. The reliability α was 0.798 in a community-dwelling older Chinese population [11].

Socio-demographic characteristics

Data on socio-demographics characteristics were collected: age, sex, marital status, educational level, employment status, monthly household income, receipt of comprehensive social security assistance (CSSA), a financial assistance scheme provided by the Hong Kong government [40], and information on living alone. Lifestyle characteristics, including smoking and drinking status and level of physical activity, were assessed by using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire Short Form (IPAQ-SF), a seven-item instrument measuring the time spent on variously intense forms of physical activity [41]. The Chinese IPAQ-SF was validated in the Hong Kong Chinese population, with an intra-class correlation coefficient of 0.79 and agreement limits of 94% compared with a physical activity log and an MTI accelerometer [42].

Health status

Health status was assessed by comorbidity using the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), and other conditions common in older adults such as visual or hearing abilities, use of dentures, difficulty in chewing food and appetite. The presence of any disease was reported by participant who had the condition diagnosed by their physicians. CCI classifies comorbid conditions, with a weighed score of 1,2,3 or 6 assigned to each condition associated with a death risk [43]. The total score of CCI was calculated by the summation of weighed scores of each presented condition of the individual. It was validated in Chinese older adults, with the area under the receiver operating the characteristic curve (AUC) of CCI in predicting one-year mortality of 0.68 [44]. For other common geriatric conditions, they were directly reported or rated in a 3-point scale by subjects to reflect their overall impact to the living of subjects. The question on usual appetite was modified from Council on Nutrition appetite questionnaire [45].

Dietary factors

As for dietary factors, the usual consumption of five major food groups (grains, vegetables, fruit, meat and milk) were assessed using culturally specific food frequency list adopted from the Hong Kong Department of Health [46]. Locally standard sizes of bowls, cups and food models were used for clear illustration of the serving size in the interviews. Adherence to the dietary guidelines was determined by comparing the servings of each food group with the recommendations of the Healthy Eating Food Pyramid for the Elderly, developed by the Department of Health [47]. Details of self-cooked food and dietary supplement consumption were obtained in the interviews. Dietary behaviour included favourite food groups, main meal skipping behaviour, and the preferred temperature of food and drink.

Statistical analysis

Data was presented as means (SD) for continuous variables and frequency (%) for categorical variables. The nutritional status of the participants was dichotomised to (1) normal and (2) at risk or malnourished based on MNA. Socio-demographic and lifestyle characteristics, health status and dietary factors were presented and compared between participants with normal nutritional status (MNA ≥ 24) and at risk or malnourished (MNA < 24) by independent t-test for continuous variables and chi-square test for categorical variables. Binary logistic regression was used to perform univariate analysis of socio-demographic and lifestyle characteristics, health status and dietary factors associated with at-risk or malnourished nutritional status. Those factors with a p-value < 0.25 in the univariate analyses were selected as candidate independent variables for backward multivariable logistic regression to identify factors independently associated with at-risk or malnourished status. The results of the final multivariable logistic regression model for the nutritional status outcome were presented by the odds ratios (OR) and their associated 95% confidence intervals (CI) of the significant factors identified. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS 24.0 (IBM Crop, Armonk, NY). All statistical tests were two-sided with the level of significance set at 0.05.

Results

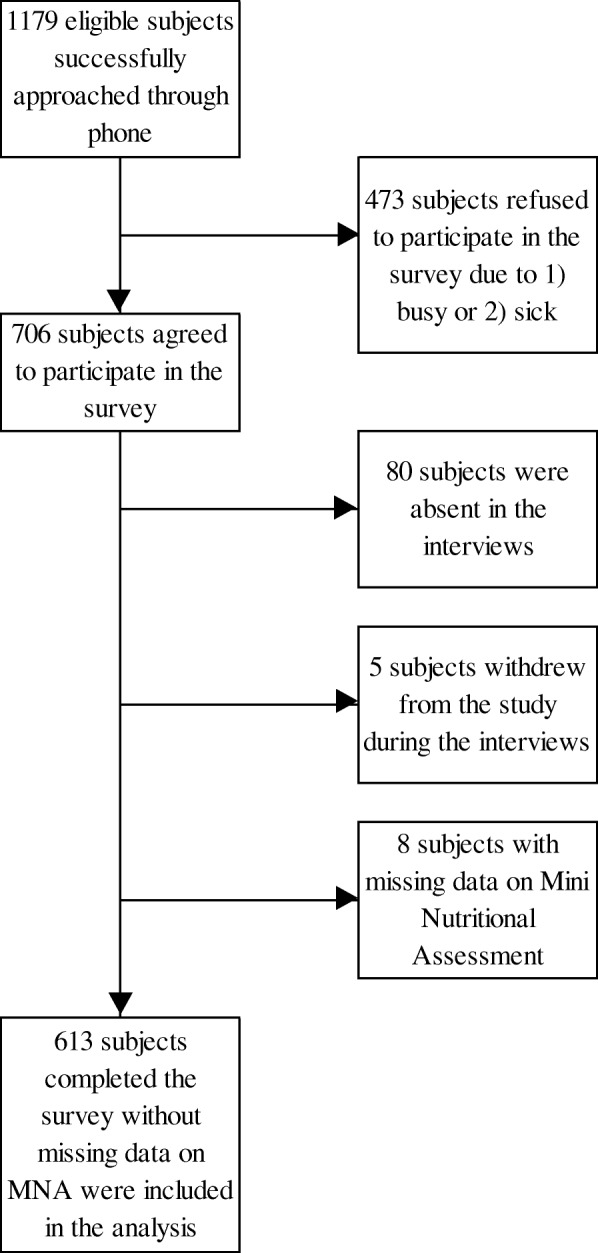

A total of 613 subjects completed the survey without missing data on MNA were included in the study (response rate = 52.0%) (Fig. 1). With 54.0% females, the sample collected matched the sex distribution of the Hong Kong older population [48]. The mean age of the subjects was 78.5 ± 7.4, ranging from 60 to 106 (Table 1). The majority had only primary or lower educational attainment (72.8%), were receiving CSSA (59.5%) and living alone (63.3%). About half of the subjects (49.5%) had at least one chronic condition, with total CCI score greater than zero. A considerable proportion reported visual (56.0%) or hearing impairment (41.4%), and more than half reported the use of dentures (63.9%). A large proportion did not adhere to dietary guidelines on the vegetable (82.9%), fruit (72.9%), meat (93.3%) and milk (80.4%) groups, with at least 80% below the recommendations. The majority cooked food for themselves (78.5%) and did not take dietary supplements (63.0%).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the study. MNA: Mini Nutritional Assessment

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics, lifestyle characteristics, health status and dietary factors of the participants (n = 613)

| Mean (SD) / n (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (n = 613) | Normal nutritional status (MNA ≥ 24) (n = 434) |

At risk or malnourished (MNA < 24) (n = 179) |

p-value | |

| Socio-demographic characteristics | ||||

| Age (years) * [range: 60–106] | 78.5 (7.4) | 78.5 (7.0) | 78.6 (8.1) | 0.838 |

| Sexa | ||||

| Male | 282 (46.0) | 203 (46.8) | 79 (44.1) | 0.551 |

| Female | 331 (54.0) | 231 (53.2) | 100 (55.9) | |

| Educational level | ||||

| No formal education | 188 (30.7) | 127 (29.3) | 61 (34.1) | 0.382 |

| Primary school | 258 (42.1) | 183 (42.2) | 75 (41.9) | |

| Secondary school or above | 167 (27.2) | 124 (28.6) | 43 (24.0) | |

| Employment status | ||||

| Retired | 580 (94.9) | 412 (94.9) | 168 (94.9) | 0.825 |

| Unemployed | 18 (2.9) | 12 (2.8) | 6 (3.4) | |

| Have part-time/full-time job | 13 (2.1) | 10 (2.3) | 3 (1.7) | |

| Monthly household income (HK$) | ||||

| < 6000 | 497 (81.1) | 352 (81.1) | 145 (81.0) | 0.992 |

| ≥ 6000 | 64 (10.4) | 45 (10.4) | 19 (10.6) | |

| Unsure | 49 (8.0) | 35 (8.1) | 14 (7.8) | |

| Number of missing | 3 (0.5) | 2 (0.5) | 1 (0.6) | |

| Received CSSA | ||||

| No | 247 (40.3) | 186 (42.9) | 61 (34.1) | 0.042 |

| Yes | 365 (59.5) | 247 (56.9) | 118 (65.9) | |

| Number of missing | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0) | |

| Marital Status | ||||

| Single/divorced/separated/widowed | 328 (53.5) | 226 (52.1) | 102 (57.0) | 0.268 |

| Married/cohabited | 285 (46.5) | 208 (47.9) | 77 (43.0) | |

| Living alone | ||||

| No | 225 (36.7) | 157 (36.2) | 68 (38.0) | 0.672 |

| Yes | 388 (63.3) | 277 (63.8) | 111 (62.0) | |

| Lifestyle characteristics | ||||

| Smoking status | ||||

| Non-smoker | 451 (73.6) | 319 (73.5) | 132 (73.7) | 0.055 |

| Ex-smoker | 96 (15.7) | 75 (17.3) | 21 (11.7) | |

| Current smoker | 66 (10.8) | 40 (9.2) | 26 (14.5) | |

| Drinking status | ||||

| Non-drinker | 488 (79.6) | 343 (79.0) | 145 (81.0) | 0.721 |

| Ex-drinker | 68 (11.1) | 51 (11.8) | 17 (9.5) | |

| Current drinker | 57 (9.3) | 40 (9.2) | 17 (9.5) | |

| Level of physical activity (IPAQ-SF) | ||||

| Low | 82 (13.4) | 47 (10.8) | 35 (19.6) | 0.005 |

| Moderate | 339 (55.3) | 239 (55.1) | 100 (55.9) | |

| High | 180 (29.4) | 139 (32.0) | 41 (22.9) | |

| Number of missing | 12 (2.0) | 9 (2.1) | 3 (1.7) | |

| Health status | ||||

| Total CCI scoreb | ||||

| 0 | 302 (49.3) | 221 (50.9) | 81 (45.3) | 0.059 |

| 1 | 184 (30.0) | 134 (30.9) | 50 (27.9) | |

| 2 | 58 (9.5) | 34 (7.8) | 24 (13.4) | |

| ≥ 3 | 61 (10.0) | 38 (8.8) | 23 (12.8) | |

| Number of missing | 8 (1.3) | 7 (1.6) | 1 (0.6) | |

| Hearing ability | ||||

| Clear | 359 (58.6) | 273 (62.9) | 86 (48.0) | < 0.001 |

| Fair | 170 (27.7) | 116 (26.7) | 54 (30.2) | |

| Unclear | 84 (13.7) | 45 (10.4) | 39 (21.8) | |

| Visual ability | ||||

| Clear | 270 (44.0) | 218 (50.2) | 52 (29.1) | < 0.001 |

| Fair | 198 (32.3) | 135 (31.1) | 63 (35.2) | |

| Unclear | 145 (23.7) | 81 (18.7) | 64 (35.8) | |

| Use of denture | ||||

| No | 219 (35.7) | 160 (36.9) | 59 (33.0) | 0.373 |

| Yes | 392 (63.9) | 273 (62.9) | 119 (66.5) | |

| Number of missing | 2 (0.3) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.6) | |

| Difficulty in chewing food | ||||

| No | 374 (61.0) | 276 (63.6) | 98 (54.7) | 0.038 |

| Yes | 238 (38.8) | 157 (36.2) | 81 (45.3) | |

| Number of missing | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0) | |

| Usual appetite | ||||

| Good | 338 (55.1) | 278 (64.1) | 60 (33.5) | < 0.001 |

| Normal | 241 (39.3) | 148 (34.1) | 93 (52.0) | |

| Bad | 34 (5.5) | 8 (1.8) | 26 (14.5) | |

| Dietary factors | ||||

| Below recommendation of the dietary guidelinesc: | ||||

| Grains (3 to 5 bowls per day) | 199 (32.5) | 127 (29.3) | 72 (40.2) | 0.008 |

| Vegetables (at least 3 servings per day) | 508 (82.9) | 351 (80.9) | 157 (87.7) | 0.041 |

| Fruits (at least 2 servings per day) | 447 (72.9) | 303 (69.8) | 144 (80.4) | 0.007 |

| Meats (5 to 6 taels per day) | 572 (93.3) | 403 (92.9) | 169 (94.4) | 0.541 |

| Milk (1 to 2 glass per day) | 493 (80.4) | 352 (81.1) | 141 (78.8) | 0.473 |

| Usually cooking food myself | ||||

| No | 127 (20.7) | 84 (19.4) | 43 (24.0) | 0.202 |

| Yes | 481 (78.5) | 346 (79.7) | 135 (75.4) | |

| Number of missing | 5 (0.8) | 4 (0.9) | 1 (0.6) | |

| Dietary supplements consumption | ||||

| No | 386 (63.0) | 267 (61.5) | 119 (66.5) | 0.248 |

| Yes | 227 (37.0) | 167 (38.5) | 60 (33.5) | |

| Dietary behaviour | ||||

| Favour food group | ||||

| No preference | 54 (8.8) | 30 (6.9) | 24 (13.4) | 0.022 |

| Grains | 165 (26.9) | 108 (24.9) | 57 (31.8) | |

| Vegetables | 167 (27.2) | 128 (29.5) | 39 (21.8) | |

| Fruits | 70 (11.4) | 55 (12.7) | 15 (8.4) | |

| Meats | 146 (23.8) | 104 (24.0) | 42 (23.5) | |

| Others (milk or fat/salt/sugar) | 6 (1.0) | 4 (0.9) | 2 (1.1) | |

| Number of missing | 5 (0.8) | 5 (1.2) | 0 (0) | |

| Usual number of main meals skipped per day | ||||

| One or more | 106 (17.3) | 59 (13.6) | 47 (26.3) | < 0.001 |

| None | 507 (82.7) | 375 (86.4) | 132 (73.7) | |

| Preferred temperature of food and drink | ||||

| Warm | 365 (59.5) | 269 (62.0) | 96 (53.6) | 0.088 |

| Hot | 226 (36.9) | 148 (34.1) | 78 (43.6) | |

| Cold | 21 (3.4) | 16 (3.7) | 5 (2.8) | |

| Number of missing | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0) | |

CCI Charlson comorbidity index, CSSA comprehensive social security assistance, HK$ Hong Kong dollar, IPAQ-SF the international physical activity questionnaire – short form

Data marked with * are presented as mean (standard deviation), all others are presented as frequency (%)

aSex distribution of the Hong Kong population aged 60 or above: males, 643,258 (47.6%); females, 707,438 (52.4%) [48]

bTotal score of Charlson comorbidity index was calculated by the summation of weighed scores of each presented condition of the individual

cThe dietary guidelines were based on the serving size recommendation in the Healthy Eating Food Pyramid for Elderly, developed by Department of Health, Hong Kong [47]. The five major food groups include grains (e.g. rice, noodles, starchy vegetables, bread and oat meals), vegetables (e.g. leafy vegetables, melon, mushroom), fruits (e.g. apple, banana, dried fruits), meats (e.g. beef, fish, egg) and milk (e.g. cow milk, yogurt, cheese) [47]. One bowl equals to 250-300 ml, one serving of vegetable equals to half bowl of cooked vegetables, one serving of fruit equals to one medium-sized fruit, one tael of meats equals to meats with the size of a table tennis ball and one glass equals to 240 ml [47].

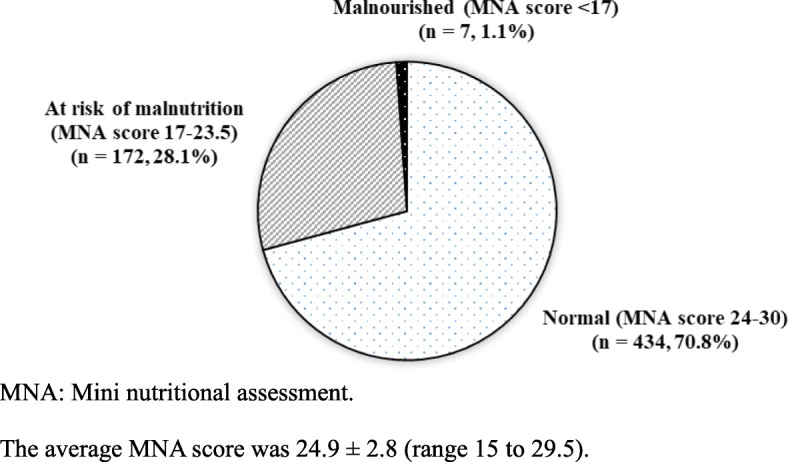

The nutritional status of the subjects is shown in Fig. 2. The mean MNA score was 24.9 ± 2.8 and ranged from 15 to 29.5. Nearly 30% of the subjects had MNA below 24, indicating they were either at risk of malnutrition (28.1%) or already malnourished (1.1%). Compared with subjects having normal nutrition status, those who were at risk or malnourished had significantly higher proportion receiving CSSA, poorer visual and hearing ability and usual appetite, more chewing difficulty and main meal skipping behaviour, and different food preference and were less active and below recommendation of the dietary guidelines of grains, vegetables and fruits (all p < 0.05) (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Nutritional status of the participants (n = 613). MNA: Mini nutritional assessment. The average MNA score was 24.9 ± 2.8 (range 15 to 29.5)s

The results of the univariate analyses of socio-demographic and lifestyle characteristics, health status and dietary factors associated with at risk or malnourished nutritional status are to be found in Table 2. A backward multivariable logistic regression analysis using those factors with p-values < 0.25 in the univariate analysis revealed that (1) visual ability, (2) usual appetite and (3) main meal skipping behaviour were significantly and independently associated with at-risk or malnourished status (Table 2). Compared with those with good visual ability, older adults with only fair ability had a higher odds of being at risk or malnourished (adjusted odds ratio (AOR): 1.71, 95% CI: 1.09–2.67, p = 0.020) and those with weak ability had an even higher odds (AOR: 2.71, 95% CI: 1.68–4.35, p < 0.001). Older adults with a good usual appetite had a decreased odds of being at risk or malnourished (AOR: 0.38, 95% CI: 0.26–0.56, p < 0.001), whereas those with little usual appetite had an increased odds (AOR: 4.52, 95% CI: 1.92–10.62, p < 0.001), when compared with those who reported a normal usual appetite. Older adults skipping one or more main meals per day had an increased odds of being at risk or malnourished (AOR: 2.03, 95% CI: 1.27–3.25, p = 0.003) compared with those without main meal skipping behaviour.

Table 2.

Factors associated with nutritional status (at risk or malnourished vs normal) (n = 613)

| Univariate analysis | Multivariable analysis | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORU | 95% CI | p | ORA | 95% CI | p | |||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||||

| Socio-demographic characteristics | ||||||||

| Received CSSA | ||||||||

| No (ref) | 1 | NS | ||||||

| Yes | 1.46 | 1.01 | 2.09 | 0.042 | ||||

| Lifestyle characteristics | ||||||||

| Smoking status | ||||||||

| Non-smoker (ref) | 1 | NS | ||||||

| Ex-smoker | 0.68 | 0.40 | 1.14 | 0.145 | ||||

| Current smoker | 1.57 | 0.92 | 2.68 | 0.097 | ||||

| Level of physical activity (IPAQ-SF) | ||||||||

| Low (ref) | 1 | NS | ||||||

| Moderate | 0.56 | 0.34 | 0.92 | 0.023 | ||||

| High | 0.40 | 0.23 | 0.69 | 0.001 | ||||

| Health status | ||||||||

| Total CCI score | ||||||||

| 0 (ref) | 1 | NS | ||||||

| 1 | 1.02 | 0.67 | 1.54 | 0.932 | ||||

| 2 | 1.93 | 1.08 | 3.44 | 0.027 | ||||

| ≥ 3 | 1.65 | 0.93 | 2.94 | 0.088 | ||||

| Hearing ability | ||||||||

| Clear (ref) | 1 | NS | ||||||

| Fair | 1.48 | 0.99 | 2.21 | 0.058 | ||||

| Unclear | 2.75 | 1.68 | 4.50 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Visual ability | ||||||||

| Clear (ref) | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Fair | 1.96 | 1.28 | 2.99 | 0.002 | 1.71 | 1.09 | 2.67 | 0.020 |

| Unclear | 3.31 | 2.12 | 5.17 | < 0.001 | 2.71 | 1.68 | 4.35 | < 0.001 |

| Difficulty in chewing food | ||||||||

| No (ref) | 1 | NS | ||||||

| Yes | 1.45 | 1.02 | 2.07 | 0.038 | ||||

| Usual appetite | ||||||||

| Normal (ref) | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Good | 0.34 | 0.24 | 0.50 | < 0.001 | 0.38 | 0.26 | 0.56 | < 0.001 |

| Bad | 5.17 | 2.25 | 11.91 | < 0.001 | 4.52 | 1.92 | 10.62 | < 0.001 |

| Dietary factors | ||||||||

| Below recommendation of the dietary guidelinesa: | ||||||||

| Grains (3 to 5 bowls per day) | ||||||||

| No (ref) | 1 | NS | ||||||

| Yes | 1.63 | 1.13 | 2.34 | 0.009 | ||||

| Vegetables (at least 3 servings per day) | ||||||||

| No (ref) | 1 | NS | ||||||

| Yes | 1.69 | 1.02 | 2.80 | 0.043 | ||||

| Fruits (at least 2 servings per day) | ||||||||

| No (ref) | 1 | NS | ||||||

| Yes | 1.78 | 1.17 | 2.71 | 0.008 | ||||

| Usually cooking food myself | ||||||||

| No (ref) | 1 | NS | ||||||

| Yes | 0.76 | 0.50 | 1.16 | 0.203 | ||||

| Dietary supplements consumption | ||||||||

| No (ref) | 1 | NS | ||||||

| Yes | 0.81 | 0.56 | 1.16 | 0.248 | ||||

| Dietary behaviour | ||||||||

| Favour food group | ||||||||

| No preference (ref) | 1 | NS | ||||||

| Grains | 0.66 | 0.35 | 1.23 | 0.192 | ||||

| Vegetables | 0.38 | 0.20 | 0.73 | 0.003 | ||||

| Fruits | 0.34 | 0.16 | 0.75 | 0.007 | ||||

| Meats | 0.50 | 0.27 | 0.96 | 0.038 | ||||

| Others (milk/fat/salt/sugar) | 0.63 | 0.11 | 3.71 | 0.605 | ||||

| Usual number of main meals skipped per day | ||||||||

| None (ref) | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| One or more | 2.26 | 1.47 | 3.48 | < 0.001 | 2.03 | 1.27 | 3.25 | 0.003 |

| Preferred temperature of food and drink | ||||||||

| Warm (ref) | 1 | NS | ||||||

| Hot | 1.48 | 1.03 | 2.12 | 0.034 | ||||

| Cold | 0.88 | 0.31 | 2.46 | 0.801 | ||||

CCI Charlson comorbidity index, IPAQ-SF the international physical activity questionnaire – short form, NE not entered into multivariable analysis, NS not statistically significant in multivariable analysis, ORA odds ratio adjusted for other significant factors obtained from backward stepwise logistic regression analysis using variables with p-value < 0.25 in univariate analysis as candidate variables, ORU univariate odds ratio, ref Reference group of the categorical variable

aThe dietary guidelines were based on the serving size recommendation in the Healthy Eating Food Pyramid for Elderly, developed by Department of Health, Hong Kong [47]. The five major food groups include grains (e.g. rice, noodles, starchy vegetables, bread and oat meals), vegetables (e.g. leafy vegetables, melon, mushroom), fruits (e.g. apple, banana, dried fruits), meats (e.g. beef, fish, egg) and milk (e.g. cow milk, yogurt, cheese) [46]. One bowl equals to 250-300 ml, one serving of vegetable equals to half bowl of cooked vegetables, one serving of fruit equals to one medium-sized fruit, one tael of meats equals to meats with the size of a table tennis ball and one glass equals to 240 ml [47]

Discussion

It has long been believed that malnutrition is an important health issue only in less developed economies where food insecurity and infectious disease prevail [49]. Given the social and economic transformation in China, overweight and obesity have become a research and service focus [50], while malnutrition in vulnerable groups such as older adults have usually been ignored. Our study is the only one to concentrate on malnutrition of older adults in an affluent Chinese community. The findings show that nearly 30% of the subjects were at risk of malnutrition, close to the global average, which revealed that 37.7% of the community older adults were at malnourished risk or already malnourished [51]. This suggests that malnutrition is not limited to developing regions [11, 33], and that more effort should also be put into examining its underlying causes in affluent regions.

By multivariable logistic regression, the high malnutrition risk was found to be associated with (1) fair and poor visual ability, (2) lack of appetite and (3) meal skipping behaviour. Our study found the poorer the visual ability, the higher the odds of being at risk or malnourished. This is consistent with a previous study’s finding that poor vision was associated with higher malnutrition risk among older assisted-living residents [52]. Since poor vision reduces the functional status of older people [53, 54], subjects with impaired sight may find it difficult to feed themselves and go shopping for supplies, causing reduced food intake and thus malnutrition. Previous literature found that older adults having low scores in both basic and instrumental daily living activity [12, 15, 25] had a higher malnutrition risk. Visual problems are common in Hong Kong [55], but the waiting time for new case booking at eye specialist out-patient clinic is extremely long, ranging from 47 to 153 weeks for a stable case [56]. Improvement in eye care services may pose a secondary effect to improve the nutritional status in the visually impaired population.

Our findings on the relationship between poor appetite and high malnutrition risk are consistent with a Netherlands prospective cohort study [26], indicating that one does lead to the other. Poor appetite is associated with lower intake of energy and protein [57], which contributes to malnutrition. A qualitative study on home-living older adults’ views on food reported that the quality of food, including taste and fashion, was of importance [58]. The taste and smell of food can be enhanced using flavourings and seasonings to stimulate appetite [59, 60]. Old-fashioned food and increased food variety might be considered in meal planning for older people [58, 59]. In the affluent Chinese community, the reduced appetite may be caused by depression, especially when the prevalence of depression was high (12.5%) among Hong Kong older adults [61]. This indicated the need to cover multiple dimensions of geriatric problems for nutritional intervention.

In our study, subjects with meal skipping behaviour had a higher malnutrition risk, matching the findings of other studies [10, 13]. Skipping meals may imply insufficient food intake, leading to malnutrition [13]. There are several possible reasons leading to the skipping of meals. First, living alone or being alone in the daytime is widespread in developed regions with smaller family structure [62], increasing the chances of skipping meals as older people prefer not to eat alone [63, 64]. Second, older adults may skip meals because of financial constraints. A comparative study suggest that a pleasant eating environment increases older people’s energy intake at each meal [65]. Canteens for the older adults selling nutritionally balanced meals at low cost may provide a place for them to interact with one another, developing the social support that reduces loneliness and malnutrition risk [66, 67].

The strengths of our study include the use of MNA, which is a well-validated and frequently used nutrition screening tool specifically intended for older adults [36, 51], and the use of materials such as booklets with detailed procedures of anthropometric measurements, and standard sizes of bowls, cups and food models to ensure high reliability during data collection. The limitations of the study include the cross-sectional design, which cannot identify the cause-and-effect relationship between malnutrition and its associated factors, and convenience sampling, which may introduce bias. Furthermore, the local dietary guideline did not consider gender-specific food intake, which may lead to overestimation of insufficient food intake in female requiring relatively less intake than male. However, other gender-specific guidelines such as the Eatwell Guide from UK [68] were not adopted due to cultural and ethnic issues, as Caucasian has larger body size and thus higher nutrition requirement than Chinese. Although a substantial number of comorbid subjects with various diseases were included in the study, some potential subjects declined to participate because of illness, which may have led to lower comorbidity in our sample. As comorbidity is positively associated with malnutrition [11], the implication is that the malnutrition risk reported in our study may be an underestimate.

Conclusions

To conclude, this study found that a significant proportion of the home-living older adults were at risk of malnutrition in an affluent Chinese community, which causes much concern and deserves attention, revealing a need to examine the impacts of disparity between rich and poor on nutrition in older adults. The results of the multivariable logistic regression analysis found that, fair or poor visual ability, lack of appetite and meal skipping behaviour are associated with high malnutrition risk. Eye care services improvement is vital to reduce the problem of visual impairment and thus malnutrition. The sensory perception of flavour, wide variety and traditional types of food can improve the appetite of older adults. Older people’s canteens can be developed to allow interaction among older adults to enhance social support, while providing nutritionally balanced meals at low cost.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Neighbourhood Advice-Action Council for their support of this study. We thank Ms. Hau Yee Or, Mr. Chi Tat Ngai and Ms. Wing Tung Chan for the coordination of the study, NGO staff for recruitment, NGO social workers and university nursing students for data collection and entry, and the subjects themselves for participating.

Funding

This study received financial support from the Neighbourhood Advice-Action Council.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analysed during this study are not publicly available due to participants’ confidentiality and privacy issues.

Abbreviations

- AOR

Adjusted odds ratio

- AUC

Area under the receiver operating the characteristic curve

- CCI

Charlson Comorbidity Index

- CI

Confidence interval

- CSSA

Comprehensive social security assistance

- ESPEN

European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism

- HK$

Hong Kong dollar

- IPAQ-SF

International Physical Activity Questionnaire Short Form

- MNA

Mini Nutritional Assessment

- NE

Not entered into multivariable analysis

- NGO

Non-governmental organisation

- NS

Not statistically significant in multivariable analysis

- OR

Odds ratios

- ORA

Odds ratio adjusted for other significant factors obtained from backward stepwise logistic regression analysis using variables with p-value < 0.25 in univariate analysis as candidate variables

- ORU

Univariate odds ratio

- ref.

Reference group of the categorical variable

- SD

Standard deviation

- UK

United Kingdom

Authors’ contributions

MMHW contributed to the study conception and design, coordination, data analysis and data interpretation, and drafted the manuscript, WKWS to the study conception and design, coordination and data interpretation, KCC to the study design, data analysis and data interpretation, RC to the study conception and design, coordination and data interpretation, HYLC and JWHS to the study conception and design and data interpretation, BH to the study conception and design, coordination and data interpretation, FL and TYL to the study coordination, and SYC to study conception and design. All authors were involved in critical revision of the manuscript and approved the final version.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Survey and Behavioural Research Ethics Committee of the Chinese University of Hong Kong. During the recruitment, eligible subjects were contacted by the NGO staff to ensure confidentiality. They received an information sheet with the details of the study, their rights regarding participation and withdrawal at any stage. They were informed that the survey would be completed anonymously. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects who were interested in participating. Approval for the use of certain instruments in the study was obtained before data collection.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Martin M. H. Wong, Email: martinwong@cuhk.edu.hk

Winnie K. W. So, Phone: 852-3943-1072, Email: winnieso@cuhk.edu.hk

Kai Chow Choi, Email: kchoi@cuhk.edu.hk.

Regina Cheung, Email: reginacheung@naac.org.hk.

Helen Y. L. Chan, Email: helencyl@cuhk.edu.hk

Janet W. H. Sit, Email: janet.sit@cuhk.edu.hk

Brenda Ho, Email: tcdcu@naac.org.hk.

Francis Li, Email: francisli@naac.org.hk.

Tin Yan Lee, Email: leety@naac.org.hk.

Sek Ying Chair, Email: sychair@cuhk.edu.hk.

References

- 1.Schrader E, Baumgartel C, Gueldenzoph H, Stehle P, Uter W, Sieber CC, et al. Nutritional status according to mini nutritional assessment is related to functional status in geriatric patients-independent of health status. J Nutr Health Aging. 2014;18(3):257–263. doi: 10.1007/s12603-013-0394-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oliveira MRM, Fogaca KCP, Leandro-Merhi VA. Nutritional status and functional capacity of hospitalized elderly. Nutr J. 2009;8:54. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-8-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abd-Al-Atty MF, Abou-Hashem RM, Abd Elaziz KM. Functional capacity of recently hospitalized elderly in relation to nutritional status. Eur Geriatr Med. 2012;3(6):356–359. doi: 10.1016/j.eurger.2012.08.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lim SL, Ong KC, Chan YH, Loke WC, Ferguson M, Daniels L. Malnutrition and its impact on cost of hospitalization, length of stay, readmission and 3-year mortality. Clin Nutr. 2012;31(3):345–350. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Correia MITD, Waitzberg DL. The impact of malnutrition on morbidity, mortality, length of hospital stay and costs evaluated through a multivariate model analysis. Clin Nutr. 2003;22(3):235–239. doi: 10.1016/S0261-5614(02)00215-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Nes MC, Herrmann FR, Gold G, Michel JP, Rizzoli R. Does the mini nutritional assessment predict hospitalization outcomes in older people? Age Ageing. 2001;30(3):221–226. doi: 10.1093/ageing/30.3.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Charlton K, Nichols C, Bowden S, Milosavljevic M, Lambert K, Barone L, et al. Poor nutritional status of older subacute patients predicts clinical outcomes and mortality at 18 months of follow-up. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2012;66(11):1224–1228. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2012.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamirudin AH, Charlton K, Walton K. Outcomes related to nutrition screening in community living older adults: a systematic literature review. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2016;62:9–25. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2015.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cuervo M, Garcia A, Ansorena D, Sanchez-Villegas A, Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Astiasaran I, et al. Nutritional assessment interpretation on 22 007 Spanish community-dwelling elders through the mini nutritional assessment test. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12(1):82–90. doi: 10.1017/S136898000800195X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kabir ZN, Ferdous T, Cederholm T, Khanam MA, Streatfied K, Wahlin A. Mini nutritional assessment of rural elderly people in Bangladesh: the impact of demographic, socio-economic and health factors. Public Health Nutr. 2006;9(8):968–974. doi: 10.1017/PHN2006990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Han YH, Li SJ, Zheng YL. Predictors of nutritional status among community-dwelling older adults in Wuhan, China. Public Health Nutr. 2006;12(8):1189–1196. doi: 10.1017/S1368980008003686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rodriguez-Tadeo A, Wall-Medrano A, Gaytan-Vidana ME, Campos A, Ornelas-Contreras M, Novelo-Huerta HI. Malnutrition risk factors among the elderly from the us-Mexico border: the “one thousand” study. J Nutr Health Aging. 2012;16(5):426–431. doi: 10.1007/s12603-011-0349-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vedantam A, Subramanian V, Rao NV, John KR. Malnutrition in free-living elderly in rural South India: prevalence and risk factors. Public Health Nutr. 2010;13(9):1328–1332. doi: 10.1017/S1368980009991674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Damayanthi HDWT, Moy FM, Khatijah LA, Dharmaratne SD. Malnutrition and associated factors among community-dwelling elderly in Sri Lanka. Ann Glob Health. 2017;83(1):77. doi: 10.1016/j.aogh.2017.03.169. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agarwalla R, Saikia AM, Baruah R. Assessment of the nutritional status of the elderly and its correlates. J Fam Community Med. 2015;22(1):39–43. doi: 10.4103/2230-8229.149588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghimire S, Baral BK, Callahan K. Nutritional assessment of community-dwelling older adults in rural Nepal. PLoS One. 2017;12(2):e0172052. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Margetts BM, Thompson RL, Elia M, Jackson AA. Prevalence of risk of undernutrition is associated with poor health status in older people in the UK. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2003;57(1):69–74. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferdous T, Kabir ZN, Wahlin Å, Streatfield K, Cederholm T. The multidimensional background of malnutrition among rural older individuals in Bangladesh–a challenge for the millennium development goal. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12(12):2270–2278. doi: 10.1017/S1368980009005096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aliabadi M, Kimiagar M, Ghayour-Mobarhan M, Shakeri MT, Nematy M, Ilaty AA, et al. Prevalence of malnutrition in free living elderly people in Iran: a cross-sectional study. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2008;17(2):285–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morais C, Oliveira B, Afonso C, Lumbers M, Raats M, MDV A. Nutritional risk of European elderly. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2013;67(11):1215–1219. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2013.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Timpini A, Facchi E, Cossi S, Ghisla MK, Romanelli G, Marengoni A. Self-reported socio-economic status, social, physical and leisure activities and risk for malnutrition in late life: a cross-sectional population-based study. J Nutr Health Aging. 2011;15(3):233–238. doi: 10.1007/s12603-010-0286-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Bokhorst-de van der Schueren MAE, Lonterman-Monasch S, de Vries OJ, Danner SA, MHH K, Muller M. Prevalence and determinants for malnutrition in geriatric outpatients. Clin Nutr. 2013;32(6):1007–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2013.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cousson PY, Bessadet M, Nicolas E, Veyrune JL, Lesourd B, Lassauzay C. Nutritional status, dietary intake and oral quality of life in elderly complete denture wearers. Gerodontology. 2012;29(2):e685–e692. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-2358.2011.00545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Soini H, Routasalo P, Lagstrom H. Characteristics of the mini-nutritional assessment in elderly home-care patients. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2004;58(1):64–70. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saletti A, Johansson L, Yifter-Lindgren E, Wissing U, Osterberg K, Cederholm T. Nutritional status and a 3-year follow-up in elderly receiving support at home. Gerontology. 2005;51(3):192–198. doi: 10.1159/000083993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schilp J, Wijnhoven HA, Deeg DJ, Visser M. Early determinants for the development of undernutrition in an older general population: longitudinal aging study Amsterdam. Br J Nutr. 2011;106(5):708–717. doi: 10.1017/S0007114511000717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Donini LM, Scardella P, Piombo L, Neri B, Asprino R, Proietti AR, et al. Malnutrition in elderly: social and economic determinants. J Nutr Health Aging. 2013;17(1):9–15. doi: 10.1007/s12603-012-0374-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iizaka S, Tadaka E, Sanada H. Comprehensive assessment of nutritional status and associated factors in the healthy, community-dwelling elderly. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2008;8(1):24–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0594.2008.00443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ribeiro RSV, da Rosa MI, Bozzetti MC. Malnutrition and associated variables in an elderly population of Criciuma, SC. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2011;57(1):56–61. doi: 10.1590/S0104-42302011000100017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Visvanathan R, Ahmad Z. Good oral health, adequate nutrient consumption and family support are associated with a reduced risk of being underweight amongst older Malaysian residents of publicly funded shelter homes. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2006;15(3):400–5. [PubMed]

- 31.Peng X. China's demographic history and future challenges. Science. 2011;333(6042):581–587. doi: 10.1126/science.1209396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.The United Nations . World population ageing, 1950-2050. New York: United Nations; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ji LX, Meng HD, Dong BR. Factors associated with poor nutritional status among the oldest-old. Clin Nutr. 2012;31(6):922–926. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.World Health Organization . World report on ageing and health 2015. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karlamangla A, Tinetti M, Guralnik J, Studenski S, Wetle T, Reuben D. Comorbidity in older adults: nosology of impairment, diseases, and condition. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62(3):296–300. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.3.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guigoz Y, Vellas B, Garry PJ. Assessing the nutritional status of the elderly: the mini nutritional assessment as part of the geriatric evaluation. Nutr Rev. 1996;54(1):S59–S65. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1996.tb03793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kondrup J, Allison SP, Elia M, Vellas B, Plauth M. ESPEN guidelines for nutrition screening 2002. Clin Nutr. 2003;22(4):415–421. doi: 10.1016/S0261-5614(03)00098-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nestle Nutrition Institute . A guide to completing the mini nutritional assessment - Short form. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vellas B, Guigoz Y, Garry PJ, Nourhashemi F, Bennahum D, Lauque S. The mini nutritional assessment (MNA) and its use in grading the nutritional state of elderly patients. Nutrition. 1999;15(2):116–122. doi: 10.1016/S0899-9007(98)00171-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Social Welfare Department, HKSAR . Comprehensive Social Security Assistance (CSSA) Scheme 2017. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjostrom M, Bauman AE, Booth ML, Ainsworth BE. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35(8):1381–1395. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Macfarlane DJ, Lee CC, Ho EY, Chan KL, Chan DT. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of IPAQ (short, last 7 days) J Sci Med Sport. 2007;10(1):45–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chan TC, Luk JK, Chu LW, Chan FH. Validation study of Charlson comorbidity index in predicting mortality in Chinese older adults. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2014;14(2):452–457. doi: 10.1111/ggi.12129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wilson MMG, Thomas DR, Rubenstein LZ, Chibnall JT, Anderson S, Baxi A, et al. Appetite assessment: simple appetite questionnaire predicts weight loss in community-dwelling adults and nursing home residents. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82(5):1074–1081. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/82.5.1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Department of Health, HKSAR . Food Groups at a Glance. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Department of Health, HKSAR . Health Eating Food Pyramid for Elderly. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Census and Statistics Department, HKSAR . 2011 Population Census Main Report Volume I. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Muller O, Krawinkel M. Malnutrition and health in developing countries. CMAJ. 2005;173(3):279–286. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu Y. Overweight and obesity in China: the once lean giant has a weight problem that is increasing rapidly. BMJ. 2006;333(7564):362. doi: 10.1136/bmj.333.7564.362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kaiser MJ, Bauer JM, Ramsch C, Uter W, Guigoz Y, Cederholm T, et al. Frequency of malnutrition in older adults: a multinational perspective using the mini nutritional assessment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(9):1734–1738. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Muurinen SM, Soini HH, Suominen MH, Saarela RKT, Savikko NM, Pitkala KH. Vision impairment and nutritional status among older assisted living residents. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2014;58(3):384–387. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee P, Smith JP, Kington R. The relationship of self-rated vision and hearing to functional status and well-being among seniors 70 years and older. Am J Ophthalmol. 1999;127(4):447–452. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9394(98)00418-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sloan FA, Ostermann J, Brown DS, Lee PP. Effects of changes in self-reported vision on cognitive, affective, and functional status and living arrangements among the elderly. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140(4):618–627. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Michon JJ, Lau J, Chan WS, Ellwein LB. Prevalence of visual impairment, blindness, and cataract surgery in the Hong Kong elderly. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86(2):133–139. doi: 10.1136/bjo.86.2.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hospital Authority . Waiting time for new case booking at eye special out-patient clinic 2018. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Payette H, Graydonald K, Cyr R, Boutier V. Predictors of dietary-intake in a functionally dependent elderly population in the community. Am J Public Health. 1995;85(5):677–683. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.85.5.677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Edfors E, Westergren A. Home-living elderly people's views on food and meals. J Aging Res. 2012. 10.1155/2012/761291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Sorensen LB, Moller P, Flint A, Martens M, Raben A. Effect of sensory perception of foods on appetite and food intake: a review of studies on humans. Int J Obes. 2003;27(10):1152–1166. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schiffman SS, Warwick ZS. Flavor enhancement of foods for the elderly can reverse anorexia. Neurobiol Aging. 1988;9(1):24–26. doi: 10.1016/S0197-4580(88)80009-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chi I, Yip PS, Chiu HF, Chou KL, Chan KS, Kwan CW, et al. Prevalence of depression and its correlates in Hong Kong's Chinese older adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13(5):409–416. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.5.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yeung WJJ, Cheung AKL. Living alone: one-person households in Asia. Demogr Res. 2015;32:1099–1112. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2015.32.40. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Davis MA, Murphy SP, Neuhaus JM. Living arrangements and eating behaviors of older adults in the United States. J Gerontol. 1988;43(3):S96–S98. doi: 10.1093/geronj/43.3.S96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tani Y, Kondo N, Takagi D, Saito M, Hikichi H, Ojima T, et al. Combined effects of eating alone and living alone on unhealthy dietary behaviors, obesity and underweight in older Japanese adults: results of the JAGES. Appetite. 2015;95:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2015.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gibbons MRD, Henry CJK. Does eating environment have an effect on food intake in the elderly? J Nutr Health Aging. 2005;9(1):25–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Romero-Ortuno R, Casey AM, Cunningham CU, Squires S, Predergast D, Kenny RA, et al. Psychosocial and functional correlates of nutrition among community-dwelling older adults in Ireland. J Nutr Health Aging. 2011;15(7):527–531. doi: 10.1007/s12603-010-0278-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Masi CM, Chen HY, Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. A meta-analysis of interventions to reduce loneliness. Personal Soc Psychol Rev. 2011;15(3):219–266. doi: 10.1177/1088868310377394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.National Health Service . The Eatwell Guide. 2016. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analysed during this study are not publicly available due to participants’ confidentiality and privacy issues.