Abstract

Background: Although the fragmentation of end-of-life care has been well documented, previous research has not examined racial and ethnic differences in transitions in care and hospice use at the end of life.

Design and Subjects: Retrospective cohort study among 649,477 Medicare beneficiaries who died between July 2011 and December 2011.

Measurements: Sankey diagrams and heatmaps to visualize the health care transitions across race/ethnic groups. Among hospice enrollees, we examined racial/ethnic differences in hospice use patterns, including length of hospice enrollment and disenrollment rate.

Results: The mean number of care transitions within the last six months of life was 2.9 transitions (standard deviation [SD] = 2.7) for whites, 3.4 transitions (SD = 3.2) for African Americans, 2.8 transitions (SD = 3.0) for Hispanics, and 2.4 transitions (SD = 2.7) for Asian Americans. After adjusting for age and sex, having at least four transitions was significantly more common for African Americans (39.2%; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 38.8–39.6%) compared with whites (32.5%, 95% CI: 32.3–32.6%), and less common among Hispanics (31.2%, 95% CI: 30.4–32.0%), and Asian Americans (26.5%, 95% CI: 25.5–27.5%). Having no care transition was significantly more common for Asian Americans (33.0%, 95% CI: 32.0–34.1%) and Hispanics (28.8%, 95% CI: 28.0–29.6%), compared with African Americans (19.2%, 95% CI: 18.9–19.5%) and whites (18.9%, 95% CI: 18.8–19.0%). Among hospice users, whites, African Americans, and Hispanics had similar length of hospice enrollment, which was significantly longer than that of Asian Americans. Nonwhite patients were significantly more likely than white patients to experience hospice disenrollment.

Conclusions: Racial/ethnic differences in patterns of end-of-life care are marked. Future studies to understand why such patterns exist are warranted.

Keywords: care transition, end-of-life care, hospice use pattern, racial difference, Sankey diagram

Introduction

The fragmentation in end-of-life care has been well documented.1–5 More than 80% of the Medicare decedents in 2011 had at least one care transition at the last six months of life,5 and ∼10% of Medicare decedents in 2015 had care transition during last three days of life.1 Such transitions can be burdensome and associated with wasteful resource use if poorly managed. Indeed, surveys of bereaved family members revealed that care transitions in the last three days of life were associated with unmet needs and poor rating of care quality.6

Although previous research has reported racial/ethnic differences in end-of-life care, such as minority groups were less likely to receive hospice care and more likely to receive aggressive end-of-life care,7–14 little is known about end-of-life care transitions across racial/ethnic groups. Only two studies to our knowledge provided limited evidence regarding this issue4,5: One study found nonwhite hospice enrollees were more likely to have care transitions than white hospice enrollees.4 Extending to both hospice and nonhospice users, the other study showed that, in comparison with whites, African Americans were significantly more likely to have multiple end-of-life care transitions, but Hispanics were less likely to do so.5 The focus of these two studies, however, was not race/ethnicity, which was only considered as a confounding factor. That is, these studies did not report each racial/ethnic group the number of end-of-life care transitions, nor the sequence of transition. Furthermore, although multiple care transitions did not equate with more aggressive end-of-life care, the findings that Hispanics are more likely to receive aggressive end-of-life care, but less likely to have multiple care transitions, seemed counterintuitive, indicating nuanced differences between care transitions and other end-of-life intensity measures. Thus, the end-of-life care transition patterns across racial/ethnic groups remain largely unknown.

Accordingly, we sought to characterize racial/ethnic differences in patterns of health care transition in the last six months of life among decedents in the United States. Analyzing the Medicare claims data from fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries, we created Sankey diagrams and heatmaps to illustrate the sequences and timing of health care transitions by racial/ethnic groups. For each racial/ethnic group, we also estimated the proportions of decedents who died in the hospital, who had repeated hospitalization, and who were enrolled in hospice. Because more than 50% of hospice users had potentially concerning hospice use patterns,15–17 we further examined racial differences in hospice disenrollment, very short hospice enrollment (enrollment ≤7 days), and very long hospice enrollment (enrollment ≥180 days) among hospice users. Findings from this study can provide a more complete picture of racial/ethnic differences in end-of-life care. Illustrating the end-of-life care transition patterns across racial/ethnic groups could not only advance our knowledge but also help identify areas where interventions may improve access to high-quality end-of-life care that meets the preferences of individuals and families across racial and ethnic groups.

Methods

Study design and sample

We conducted a retrospective analysis of all fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries aged 66 years or older who died between July 1, 2011 and December 31, 2011. We limited our sample to Medicare Parts A and B beneficiaries. The study was exempt from full review by the Institutional Review Board of Yale University.

Measurement

Outcomes

The primary outcomes of interest were the number of health care transitions, hospice enrollment within the last six months of life, and in-hospital death. Using data from Medicare claim files of inpatient, skilled nursing facility, and hospice services, we created a per-person chronological history of health care settings within the last six months of life on a daily basis. Consistent with previous research,5 we included five health care settings, with a hierarchy of intensity from hospital, to skilled nursing facility, to inpatient hospice, to home hospice, and to home. A transition was considered present when consecutive days of care were given in different health care settings. We measured end-of-life care intensity, including hospice use within the last six months to indicate less aggressive care, and repeated hospitalization during the last month and in-hospital death to indicate more aggressive care. We also created three binary measures to indicate very short hospice enrollment (enrollment ≤7 days), very long hospice enrollment (enrollment ≥180 days), and hospice disenrollment within the last six months of life. We used hospice claims in 2011 to calculate the duration of hospice enrollment at the end-of-life period, acknowledging that we underestimated the duration of hospice enrollment because hospice use before 2011 was not included.

Key independent variables

The decedent's race/ethnicity was categorized as white, black, Hispanic, or Asian American, based on the records of the Master Beneficiary Summary File. Beneficiaries whose race was unknown, other, or North American Native were excluded.

Covariates

Covariates included patient age (categorized as 66–69, 70–74, 75–79, 80–84, and ≥85 years) and gender. We also ascertained chronic conditions, including seven binary measures (yes vs no) for heart disease, Alzheimer's disease or dementia, kidney disease, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or asthma, depression, stroke, and cancer (breast, colorectal, prostate, lung, and endometrial). Linking between decedents' zip code information and the Area Resource File, we identified patient metropolitan residence (metropolitan, micropolitan, and other), and U.S. Census-based estimates of income and education at the zip code level (categorical variables by quintile).

Statistical analysis

We used standard descriptive statistics to summarize patient characteristics stratified by race/ethnicity, using means for continuous variables and frequencies for categorical variables. Based on the health care setting for each person on each day in the last six months of life, we calculated the percentage of decedents who spent time in various health care settings, and we depicted variations in transitions by race/ethnicity. We summarized the sequences of transition using Sankey diagrams for each race/ethnicity group.18 Sankey diagrams, in which the width of each flow is shown proportionally to the flow quantity, have been used in science and engineering for decades. To describe the transitions over time within the last six months of life, we also created heatmaps, used in several disciplines (including gene expression profiling) for reporting microarray data,19 in which health care settings were represented as colors indicating level of care intensity, from hospital (dark black) to home (light gray). The x-axis captures time over the last six months of life. On the y-axis, each row represents one decedent, where decedents were ordered randomly.

We calculated differences in age-and-sex-adjusted proportions of decedents who had no health care transition, who had more than four transitions, who had hospice enrollment within the last six months, and who had in-hospital death for each race/ethnicity group. We also determined differences in age-and-sex-adjusted duration of hospice enrollment for each minority group relative to white beneficiaries. Among hospice users, we estimated age-and-sex-adjusted differences in potentially concerning hospice use patterns (i.e., very short enrollment, very long enrollment, or disenrollment) between whites and each minority group with the number of decedents who used hospice in each race/ethnicity group as the denominator. Bootstrap resampling was used to estimated standard errors of the age-and-sex-adjusted outcomes.20 We used C++ to generate the transition data and heatmaps. The Sankey diagrams were created using web-based SankeyMATIC.21 All statistical analyses were completed using SAS, version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), and a two-tailed p < .05 was used to define statistical significance.

Results

Our sample consisted of 573,236 non-Hispanic white patients, 55,837 African American patients, 11,198 Hispanic patients, and 9206 Asian American patients. Compared with white patients, Hispanic patients tended to be older and African American patients tended to be younger (Table 1). Nonwhite patients were significantly more likely to reside in metropolitan areas and areas with lower education level than white patients. Preexisting chronic conditions differed across racial/ethnic groups. For instance, 24.5% of both whites and African Americans had a chronic condition of cancer, compared with ∼18% of Hispanics and Asian Americans.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Decedents by Race

| Non-Hispanic White | African American | Hispanic | Asian | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 573,236 | n = 55,837 | p* | n = 11,198 | p* | n = 9206 | p* | |

| Health care transition (mean, SD) | 2.9 (2.7) | 3.4 (3.2) | <0.001 | 2.8 (3.0) | <0.001 | 2.4 (2.7) | <0.001 |

| Age in years (mean, SD) | 82.8 (8.6) | 80.5 (9.0) | <0.001 | 83.0 (8.1) | 0.006 | 82.9 (8.3) | 0.404 |

| Female (%) | <0.001 | 0.456 | <0.001 | ||||

| No | 45.2 | 43.3 | 44.9 | 48.1 | |||

| Yes | 54.8 | 56.7 | 55.1 | 51.9 | |||

| Metro (%) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Nonmetro | 10.2 | 6.7 | 2.9 | 0.8 | |||

| Micropolitan | 14.6 | 9.7 | 6.1 | 3.6 | |||

| Metropolitan | 75.2 | 83.6 | 90.9 | 95.5 | |||

| Income (%) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| <$33,000 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 1.5 | 0.1 | |||

| $33,000–$39,999 | 19.7 | 27.8 | 19.4 | 4.1 | |||

| $40,000–$49,999 | 37.7 | 32.4 | 34.2 | 15.7 | |||

| $50,000–$62,999 | 26.6 | 25.9 | 33.3 | 42.7 | |||

| ≥$63,000 | 14.9 | 10.8 | 11.5 | 37.5 | |||

| High school education (%) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| <60 | 0.1 | 0.04 | 1.4 | 0 | |||

| 60–69 | 1.9 | 3.1 | 11.8 | 0.8 | |||

| 70–79 | 14.7 | 24.8 | 40.5 | 27.0 | |||

| 80–89 | 62.1 | 63.7 | 41.2 | 57.8 | |||

| ≥90 | 21.2 | 8.4 | 5.1 | 14.4 | |||

| Chronic condition (%) | |||||||

| Heart disease | 75.7 | 74.4 | <0.001 | 77.4 | <0.001 | 72.3 | <0.001 |

| Dementia | 41.1 | 46.0 | <0.001 | 49.3 | <0.001 | 39.7 | 0.005 |

| Kidney disease | 40.4 | 52.4 | <0.001 | 44.7 | <0.001 | 43.8 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 42.3 | 58.2 | <0.001 | 63.6 | <0.001 | 56.1 | <0.001 |

| Lung disease | 48.8 | 43.3 | <0.001 | 49.9 | 0.021 | 43.9 | <0.001 |

| Depression | 43.0 | 34.4 | <0.001 | 47.0 | <0.001 | 27.9 | <0.001 |

| Stroke | 29.1 | 33.6 | <0.001 | 32.7 | <0.001 | 28.0 | 0.021 |

| Cancer | 24.5 | 24.5 | 0.806 | 17.4 | <0.001 | 17.9 | <0.001 |

SD, standard deviation.

Comparisons between non-Hispanic whites and the minority groups.

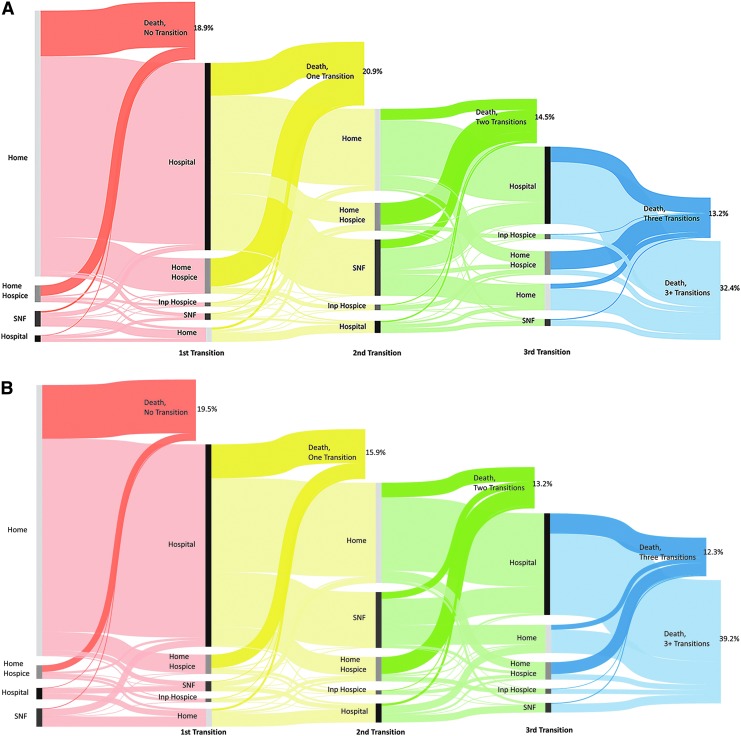

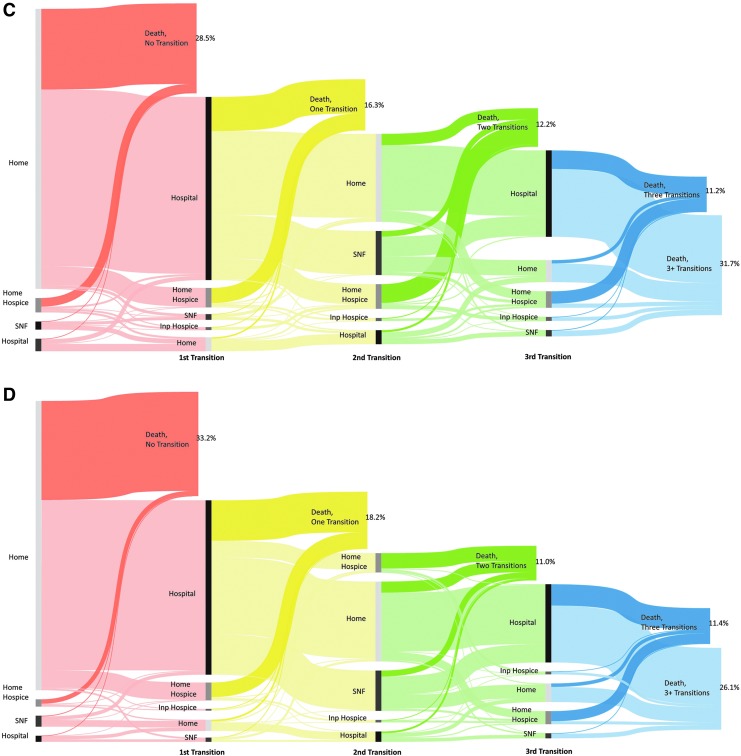

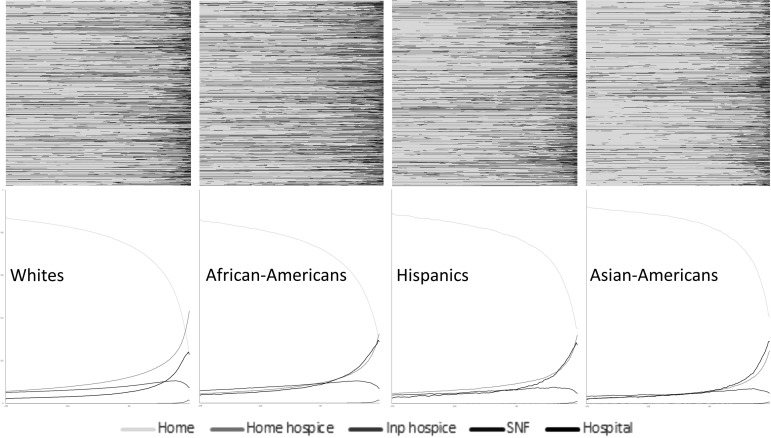

End-of-life care transition patterns differed substantially across racial/ethnic groups (Fig. 1). The number of end-of-life care transitions varied from 2.37 (standard deviation [SD] = 2.73) in Asian Americans, 2.75 (SD = 2.96) in Hispanics, 2.87 (SD = 2.74) in whites, to 3.35 (SD = 3.18) in African Americans. About 18.9% of white patients died without any transition; whereas 19.5% of African Americans, 28.5% of Hispanics, and 33.2% of Asian Americans died without any transition. Furthermore, 32.4% of white patients had four or more transitions, but the proportion of African Americans, Hispanics, and Asian Americans was 39.2%, 31.7%, and 26.1%, respectively. Transition heatmaps also demonstrated that African Americans were more likely to have end-of-life care transitions, followed by whites, and Hispanics and Asians were less likely to have end-of-life care transitions (Fig. 2). When we adjusted for age and sex, we found statistically significant differences between the four racial/ethnic groups regarding the proportion of decedents who did not have any transitions, ranging from whites (18.9%, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 18.8–19.0%), African Americans (19.2%, 95% CI: 18.9–19.5%), Hispanics (28.8%, 95% CI: 28.0–29.6%) to Asian Americans (33.0%, 95% CI: 32.0–34.1%; Fig. 3). African Americans were more likely to have ≥4 transitions (39.2%; 95% CI: 38.8–39.6%) compared with whites (32.5%, 95% CI: 32.3–32.6%), which is higher than Hispanics (31.2%, 95% CI: 30.4–32.0%) and Asian Americans (26.5%, 95% CI: 25.5–27.5%).

FIG. 1.

Sequence of care transition in the last six months of life among Medicare decedents in the United States by race: (A) non-Hispanic whites; (B) African Americans; (C) Hispanics; and (D) Asian Americans. SNF, skilled nursing facility.

FIG. 2.

Transition heatmap in the last six months of life, for Medicare decedents by race. In the heatmaps, the x-axis captures time over the last six months of life, and the y-axis represents decedents' care transition pattern. Changes in colors indicated care transition; and the darker the heatmap, the more intensive the end-of-life care.

FIG. 3.

Estimated age-and-sex-adjusted proportion of decedents who had no transition and who had ≥4 transitions in the last six months of life by race.

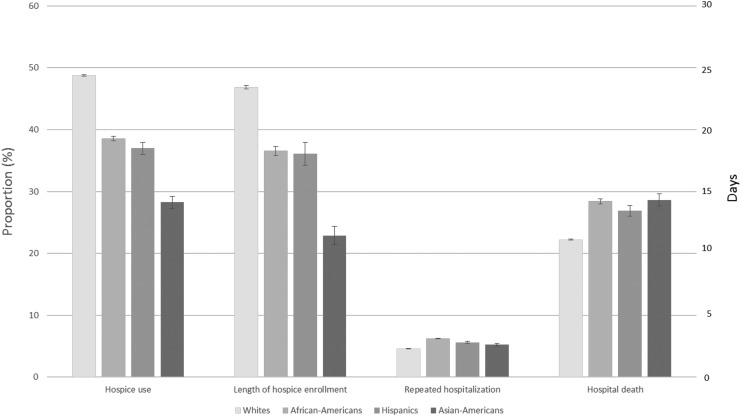

Nonwhite patients were less likely to use hospice and more likely to have repeated hospitalizations and die in a hospital (Appendix Fig. AF1). The age-and-sex-adjusted proportion of decedents with hospice use was 48.8% (95% CI: 48.6–48.2%) in whites, 38.6% (95% CI: 38.2–39.0%) in African Americans, 37.0% (95% CI: 36.0–38.0%) in Hispanics, and 28.2% (95% CI: 27.3–29.2%) in Asian Americans. The age-and-sex-adjusted length of hospice enrollment was 23.4 days (95% CI 23.3–23.6), 18.3 days (95% CI: 17.9–18.6), 18.0 days (95% CI: 17.1–19.0), and 11.4 days (95% CI: 10.7–12.2) among whites, African Americans, Hispanics, and Asian Americans, respectively. The age-and-sex-adjusted proportion of decedents with repeated hospitalization in the last month was 4.59% (95% CI: 4.58–4.61%) in whites, significantly lower than 6.23% (95% CI: 6.15–6.30%) in African Americans, 5.62% (95% CI: 5.48–5.76%) in Hispanics, and 5.25% (95% CI: 5.08–5.43%) in Asian Americans. Similarly, the age-and-sex-adjusted proportion of in-hospital death was 22.2% (95% CI: 22.1–22.4%) in whites, significantly lower than 28.4% (95% CI: 28.0–28.8%) in African Americans, 26.9% (95% CI: 26.0–27.8%) in Hispanics, and 28.6% (95% CI: 27.6–29.6%) in Asian Americans.

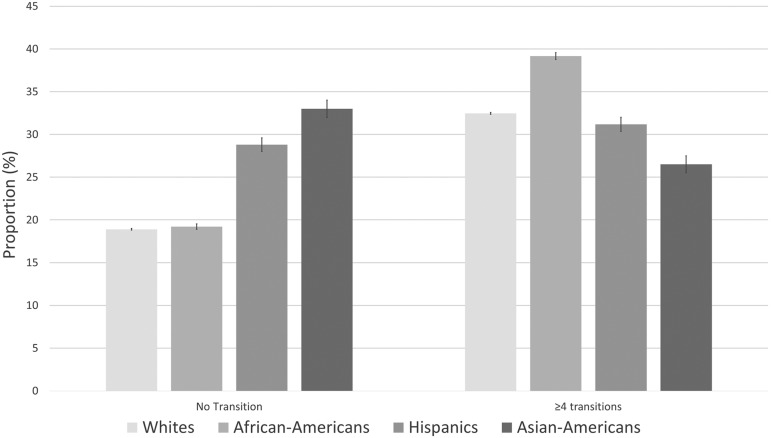

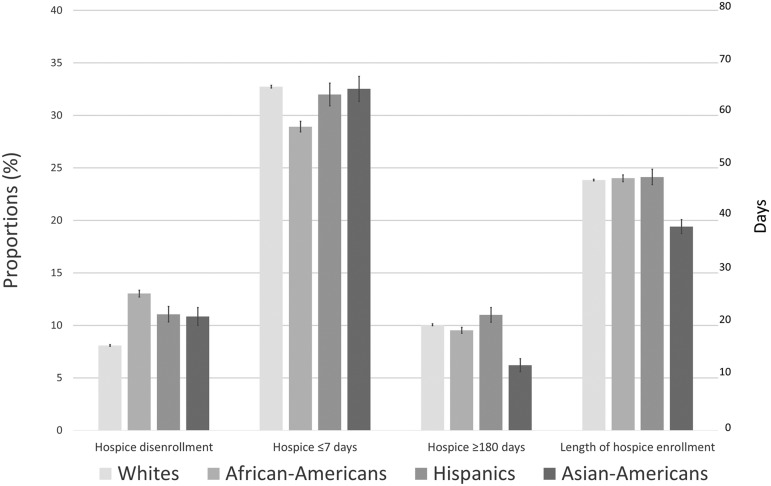

We also found differences in hospice use patterns (Fig. 4). Among hospice users, nonwhite patients were more likely to have hospice disenrollment. The age-and-sex-adjusted proportion was 8.1% (95% CI: 8.0–8.2%) in whites, compared with 13.0% (95% CI: 12.7–13.4%) in African Americans, 11.1% (95% CI: 10.3–11.8%) in Hispanics, and 10.9% (95% CI: 10.0–11.7%) in Asian Americans. African Americans were more likely to have very late hospice enrollment (28.9%, 95% CI: 28.4–29.4%), compared with whites (32.7%, 95% CI: 32.6–32.9%), Hispanics (32.0%, 95% CI: 30.9–33.1%), and Asian Americans (32.5%, 95% CI: 31.3–33.7%). Asian Americans were less likely to have very long hospice enrollment (6.2%, 95% CI: 5.6–6.8%), followed by African Americans (9.5%, 95% CI: 9.2–9.8%), than whites (10.1%, 95% CI: 10.0–10.1%) and Hispanics (11.0%, 95% CI: 10.3–11.7%). Overall, the age-and-sex-adjusted length of hospice enrollment among hospice users were quite similar among whites (47.7 days, 95% CI: 47.5–47.9), African Americans (48.0, 95% CI: 47.4–48.6), and Hispanics (48.3 days, 95% CI: 46.8–49.7), but Asian Americans tended to have shorter length of stay (38.8 days, 95% CI: 37.5–40.1).

FIG. 4.

Estimated age-and-sex-adjusted proportions of potentially concerning hospice use patterns and length of hospice stay by race.

Discussion

We found substantial racial differences in end-of-life care transitions in the last six months of life of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries. While African American patients in comparison with white patients were more likely to have multiple end-of-life care transitions, Hispanic and Asian American patients were less likely to do so, indicating differences in end-of-life care transitions across minority groups.

Building upon previous literature, this study sheds light on racial differences in end-of-life care patterns in important ways. First, end-of-life care transitions appeared to differ from the traditional measures of end-of-life care intensity. Researchers and organizations have used claims data to evaluate the intensity of end-of-life care.22,23 Consistent with previous literature,8,14 we demonstrated that nonwhite patients were more likely to have intensive end-of-life care than white patients. We further observed different racial/ethnic end-of-life care transition patterns. Hispanic and Asian American patients were less likely to have multiple transitions than white patients. The findings indicate that factors, such as socioeconomic status and cultural belief, which play an important role leading to racial/ethnic differences, may affect end-of-life care transitions differently from the way they influence end-of-life care intensity. To provide a comprehensive picture of end-of-life care patterns, studies may consider including care transitions as one of their end-of-life care intensity measures. For instance, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) is planning to include care transitions as one of the quality measures for the Hospice Quality Reporting Program.24

Second, using national data, we reported that ∼40% of African American decedents had four or more care transitions in the last six months of life. Such multiple transitions in care setting at the end of life have the potential for fragmentation of care and can be burdensome to African American decedents and their families. Even for individuals who have chosen hospice care, transitions in care at the end of life are greater for African American patients compared with white patients.4 Efforts to ensure care transitions aligned to their preferences among African Americans both within and outside the hospice setting are urgently needed. In contrast, even though Hispanic and Asian American decedents were more likely to die in a hospital than white patients, ∼30% of them did not have any care transition within the last six months of life. We speculated that many Hispanics and Asian Americans might underuse health care services; and thus, died without any care transitions. Some of them used hospital services very late and ended up dying in a hospital. Hence, efforts to educate and promote timely health services utilization and hospice referral for Hispanic and Asian American patients may need to be initiated in out-patient settings.

Because African American, Hispanic, and Asian American patients were less likely to use hospice services than white patients, we expected that nonwhite patients would have a shorter duration of hospice enrollment than white patients. Surprisingly, among hospice users, there was no significant difference in the duration of hospice enrollment among whites, African Americans, and Hispanics. These findings are encouraging, indicating that when African American and Hispanic patients elected to hospice enrollment, they did not delay receiving it. The results also imply that African American and Hispanic patients were referred to hospice at points in their disease trajectory similar to those in white patients. However, Asian American patients had a shorter hospice duration. In other words, Asian American patients are not only less likely to use hospice but also enroll with hospice closer to death. Because death is commonly a taboo topic in Asian cultures,25 Asian American patients may tend to avoid discussing end-of-life care. Consequently, it might be difficult to convince Asian American patients to timely receive hospice services.

Although the proportion of decedents using hospice has increased dramatically since the last two decades, there have been concerns about improper hospice use patterns.15,17 Literature has shown that ∼50% of hospice use were concerning,17 yet, evidence on racial differences in hospice use patterns is limited. We found that nonwhite patients were more likely to have hospice disenrollment than white patients. Researchers recently found that African American hospice enrollees were more likely than white enrollees to disenroll from hospice, and hospice provider-level effects could not totally explain the differences between white and African American enrollees.26 Furthermore, compared with white hospice enrollees, Hispanic enrollees were more likely to have hospice enrollment ≥180 days, but African American enrollees were less likely to have hospice enrollment ≤7 days. Further studies examining the relationship between timing of hospice enrollment and care transition patterns across racial/ethnic groups could help understand whether hospice use can reduce end-of-life care transitions.

Our findings should be interpreted in light of several limitations. Patient race/ethnicity was derived from Medicare records, which are subject to reporting errors, especially for the classification of Hispanics and Asian Americans.27 We also lacked information regarding beneficiary's first language. Multiple transitions may be due to poor communication between providers and patients/family members when English is not the preferred language; and improving quality of end-of-life discussions between language-discordant clinicians and patients is important.28 Second, our sample population is limited to fee-for-service Medicare decedents who died in 2011. Our results therefore may not be generalizable to younger population, those in Health Maintenance Organization plans, and those who died recently. Third, we used a decedent cohort to study racial differences in end-of-life care. This design may be subject to bias because care received by confirmed decedents may not be comparable to care received by individuals who are predicted by care providers to be at the end of life.29 Fourth, we measured a subset of care transitions at the end of life. We did not include transitions within the hospital from regular bed to intensive care unit and from settings outside the hospital to the emergency room, which are both often considered in intensity of care measures. Therefore, our results underestimate the number of transitions at the end of life. We also did not have data on beneficiary and family preferences. Some of the care transitions are desirable, such as transitions from hospital to home hospice or inpatient hospice; whereas transitions back and forth between hospital and home may be indicative of disruptive care. Future research is greatly needed to identify and monitor care transitions that are burdensome and deviate from individual preferences.

In conclusion, we found substantial variation in racial differences in end-of-life care transitions and hospice use patterns. African American patients appeared to incur the highest number of transitions, indicating room for improvement in reducing end-of-life health care transitions. Hispanic and Asian American patients were likely to die without receiving any services or to die in hospital, suggesting that they might use hospital services at the very end of life. Efforts to promote seamless care transitions can improve quality of end-of-life care across all racial/ethnic groups.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grant 1R01CA116398-01A2 from the National Cancer Institute (Drs. Aldridge and Bradley); the John D. Thompson Foundation (Dr. Cherlin); grant 1R01NR013499-01A1 from the National Institute of Nursing Research (Dr. Aldridge); and grant 1K01HS023900-01 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (Dr. Wang).

APPENDIX FIG. A1.

Estimated age-and-sex-adjusted end-of-life care intensity among decedents by race.

Author Disclosure Statement

None of the coauthors have conflicts of interest.

None of the funders had any role in the conduct of the study; in the collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or in the preparation, review, or approval of the article.

References

- 1. Teno JM, Gozalo P, Trivedi AN, et al. : Site of death, place of care, and health care transitions among US Medicare beneficiaries, 2000–2015. JAMA 2018;320:264–271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gerardi D: Team disputes at end-of-life: Toward an ethic of collaboration. Perm J 2006;10:43–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. NIH State-of-the-Science Conference Statement on improving end-of-life care. NIH Consens State Sci Statements 2004;21:1–26 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wang SY, Aldridge MD, Gross CP, et al. : Transitions between healthcare settings of hospice enrollees at the end of life. J Am Geriatr Soc 2016;64:314–322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wang SY, Aldridge MD, Gross CP, et al. : End-of-life care transition patterns of medicare beneficiaries. J Am Geriatr Soc 2017;65:1406–1413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Makaroun LK, Teno JM, Freedman VA, et al. : Late transitions and bereaved family member perceptions of quality of end-of-life care. J Am Geriatr Soc 2018;66:1730–1736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission: In: Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. Chapter 11. Hospice. Washington, DC: MEDPAC, 2011, p. 259 http://medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/Mar11_EntireReport.pdf (Last accessed February8, 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 8. Smith AK, Earle CC, McCarthy EP: Racial and ethnic differences in end-of-life care in fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries with advanced cancer. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009;57:153–158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hanchate A, Kronman AC, Young-Xu Y, et al. : Racial and ethnic differences in end-of-life costs: Why do minorities cost more than whites? Arch Intern Med 2009;169:493–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Givens JL, Tjia J, Zhou C, et al. : Racial and ethnic differences in hospice use among patients with heart failure. Arch Intern Med 2010;170:427–432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Unroe KT, Greiner MA, Johnson KS, et al. : Racial differences in hospice use and patterns of care after enrollment in hospice among Medicare beneficiaries with heart failure. Am Heart J 2012;163:987–993.e983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cohen LL: Racial/ethnic disparities in hospice care: A systematic review. J Palliat Med 2008;11:763–768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Barnato AE, Chang CC, Saynina O, Garber AM: Influence of race on inpatient treatment intensity at the end of life. J Gen Intern Med 2007;22:338–345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wang SY, Hsu SH, Huang S, et al. : Regional practice patterns and racial/ethnic differences in intensity of end-of-life care. Health Serv Res 2018;53:4291–4309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Aldridge MD, Canavan M, Cherlin E, Bradley EH: Has hospice use changed? 2000–2010 utilization patterns. Med Care 2015;53:95–101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Aldridge MD, Schlesinger M, Barry CL, et al. : National hospice survey results: For-profit status, community engagement, and service. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:500–506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wang SY, Aldridge MD, Gross CP, et al. : Geographic variation of hospice use patterns at the end of life. J Palliat Med 2015;18:771–780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schmidt M: The Sankey diagram in energy and material flow management. JI Ind Ecol 2008;12:82–94 [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bergkvist A, Rusnakova V, Sindelka R, et al. : Gene expression profiling—Clusters of possibilities. Methods 2010;50:323–335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Efron B, Tibshirani RJ: An Introduction to the Bootstrap. New York, NY: Chapman & Hall, 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 21. SankeyMATIC: A Sankey Diagram Builder for Everyone. http://sankeymatic.com (Last accessed October15, 2015)

- 22. National Quality Forum: National Voluntary Consensus Standards for Palliative Care and End-of-Life Care. https://www.qualityforum.org/Projects/Palliative_Care_and_End-of-Life_Care.aspx (Last accessed March17, 2018)

- 23. Earle CC, Park ER, Lai B, et al. : Identifying potential indicators of the quality of end-of-life cancer care from administrative data. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:1133–1138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services: Draft Measure Specifications: Transitions from Hospice Care, Followed by Death or Acute Care. 2018. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/MMS/Downloads/Development-of-Draft-HQRP-Transitions-Measure-Specifications.pdf (Last assessed July23, 2018)

- 25. Tung WC: Hospice care in Chinese culture: A challenge to home care professionals. Home Health Care Manag Pract 23:67–68 [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rizzuto J, Aldridge MD: Racial disparities in hospice outcomes: A race or hospice-level effect? J Am Geriatr Soc 2018;66:407–413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Waldo DR: Accuracy and bias of race/ethnicity codes in the Medicare enrollment database. Health Care Financ Rev 2004;26:61–72 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Norris WM, Wenrich MD, Nielsen EL, et al. : Communication about end-of-life care between language-discordant patients and clinicians: Insights from medical interpreters. J Palliat Med 2005;8:1016–1024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bach PB, Schrag D, Begg CB: Resurrecting treatment histories of dead patients: A study design that should be laid to rest. JAMA 2004;292:2765–2770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]