Abstract

Background:

Targeting low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) for lung cancer screening to those at highest risk for lung cancer mortality has been suggested to improve screening efficiency.

Objective:

Quantify the value of risk-targeted selection for lung cancer screening compared to National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) eligibility criteria.

Design:

Cost-effectiveness analysis using multi-state prediction model

Data Source:

NLST

Target Population:

Current and former smokers eligible for lung cancer screening

Time Horizon:

Lifetime

Perspective:

Healthcare sector

Intervention:

Risk-targeted versus NLST-based screening.

Outcome Measures:

Incremental 7-year mortality, life-expectancy, quality adjusted life years (QALY), costs and cost-effectiveness of screening with LDCT versus chest X-ray at each decile of lung cancer mortality risk.

Results of Base-Case Analysis:

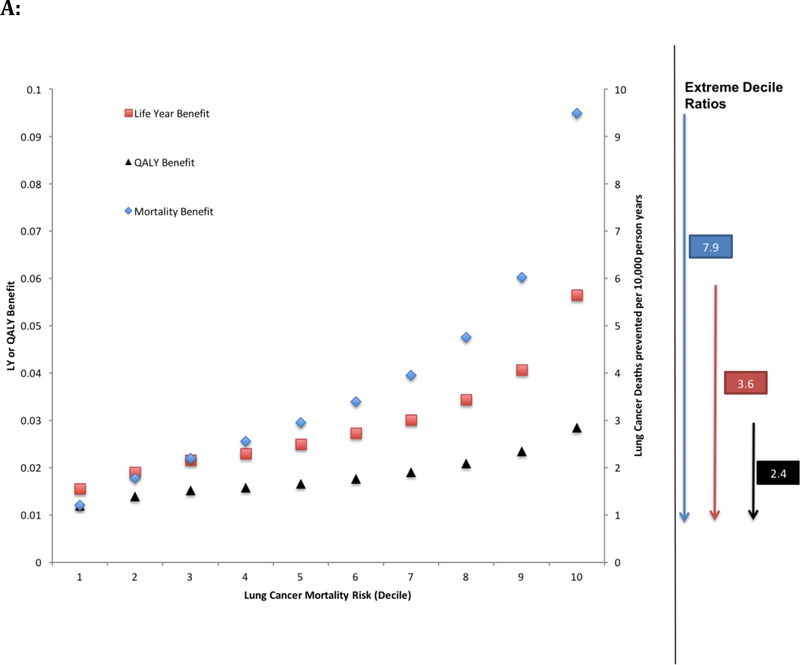

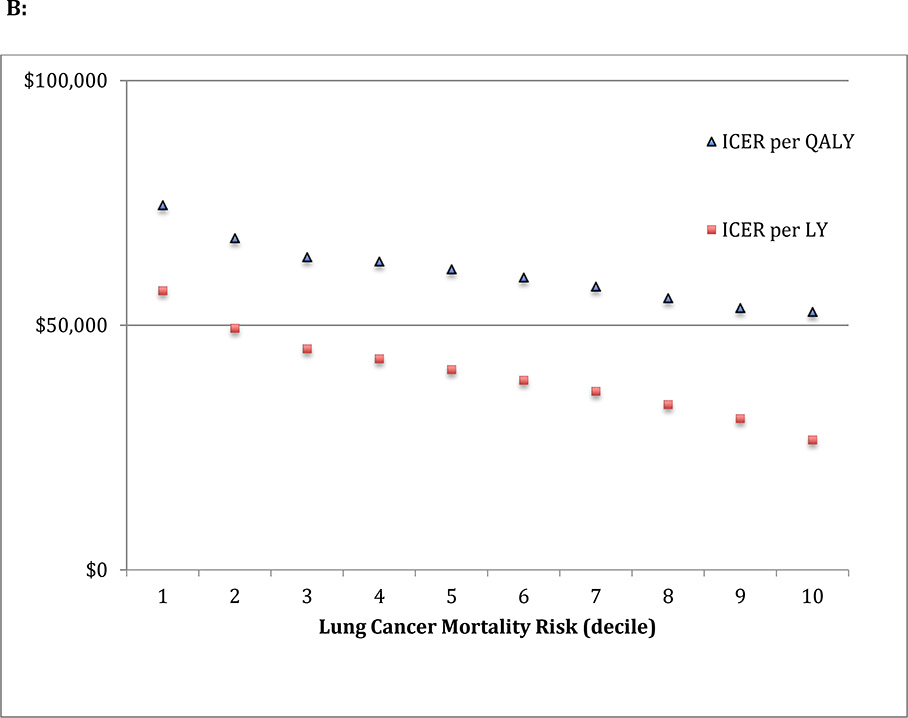

Higher lung cancer mortality risk participants were older with greater comorbidities and higher screening-related costs. The incremental lung cancer mortality benefits over the first 7 years ranged from 1.2 to 9.5 lung cancer deaths prevented per 10,000 person-years, for the lowest and highest risk deciles respectively (extreme decile ratio=7.9). The gradient of benefits across risk groups was attenuated in terms of life years (extreme decile ratio=3.6) and quality adjusted life years (extreme decile ratio=2.4). The incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) were similar across risk deciles ($75,000/QALY (lowest risk decile) to $53,000/QALY (highest risk decile)). Payers willing to pay $100,000/QALY would pay for LDCT screening for all decile groups.

Results of Sensitivity Analysis:

Alternative assumptions did not substantially alter our findings

Limitation:

Our model did not account for all correlated differences between lung cancer mortality risk and quality of life.

Conclusion:

While risk-targeting can improve screening efficiency in terms of early lung cancer mortality per person screened, the gains in efficiency are attenuated and modest in terms of life years, QALYs and cost-effectiveness.

Background

The National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) demonstrated a 20% reduction in lung cancer deaths when screening with low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) versus chest X-ray(1). NLST participants were between the ages of 55 and 74, with at least 30 pack-year smoking history and former smokers had no more than 15 years of smoking abstinence(1). Most subsequent guidelines, including the US preventative services task force (USPSTF), have largely adopted the NLST eligibility criteria when recommending who should receive lung cancer screening(2–4).

A retrospective analysis of the NLST showed that 60% of participants at highest predicted risk of lung cancer death accounted for 88% of all screening prevented lung cancer mortality(5). Other influential studies have also suggested that utilizing multiple risk factors to select the participants at the highest predicted risk of either developing or dying from lung cancer would greatly improve the efficiency and yield of lung cancer screening(6–10). A generalized limitation of these studies is that the benefits of screening with LDCT is measured in terms of reduced lung cancer mortality over the short term, generally the first 5 to 7 years per patient screened, and do not account for differences in long term survival or costs in higher versus lower risk patients.

In this analysis, we applied a novel multi-state model to calculate each NLST participant’s predicted lifetime benefits and costs of screening with LDCT versus chest X-ray. We use these estimates to examine the value of applying an individualized risk-targeted approach to participant selection for screening over the broader NLST inclusion criteria at common willingness to pay thresholds.

Methods

Model Overview

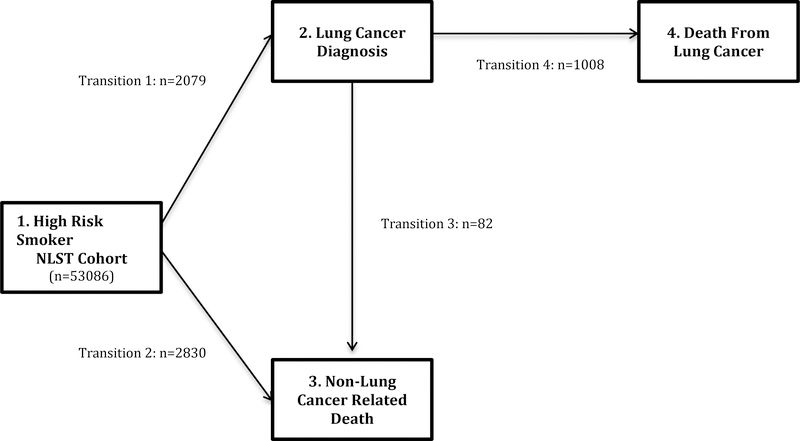

Using data from the NLST(1), we derived a multi-state regression model(11,12) to predict health state transitions as a function of an individual participant’s baseline characteristics and the lung cancer screening technology used (chest X-ray or LDCT). The rationale for using a multi-state model is described in the Appendix. This technique jointly estimates the baseline hazards and the effects of risk factors on four transitions between the four health states shown in Figure 1: 1-alive without cancer, 2-alive with lung cancer, 3-dead due to other causes or 4-dead due to lung cancer. The resulting equation provided individualized predictions, under each screening condition, of the probability of being in each of the four states at any given point in time. These predictions were used to risk stratify the population and also to predict individualized lung cancer mortality benefits of LDCT screening at 7-years. Extrapolations of the baseline hazards were used to project the probability of being in each of the 4 states beyond 7-years, in order to estimate individualized lifetime health benefits. Individualized costs were estimated using utilization data from the NLST and linear regression prediction models, plus assumptions to estimate lifetime medical costs. For the purposes of presentation, we stratified participants into deciles (10% cohorts) based on their 7-year risk of lung cancer mortality when screened with chest X-ray. Finally, we calculated the incremental net monetary benefit (iNMB) for each participant to summarize the value of a risk-stratified screening strategy compared to the NLST inclusion criteria at common willingness to pay (WTP) thresholds of $50,000/QALY and $100,000/QALY(13,14).

Figure 1: Structure of the multi-state model.

All patients enter the multi-state model as high risk smokers defined by the entry criteria for the National Lung Screening Trial (NLST). The multi-state model consists of 4 health states with 4 possible transitions. The figure describes the number of illness-death multi-state transitions over the trial period.

Model derivation and validation

The NLST enrolled 53,454 participants and randomly assigned them to undergo three consecutive annual screenings from randomization (years 0, 1 and 2) with either LDCT (26,722) or the control screening method of chest X-ray (26,732). The trial had a median follow up period of 6.5 years. Our multi-state regression model included 8 baseline variables for each NLST participant (age, sex, race, family history in a first degree relative, body mass index (BMI), smoking exposure (pack-years), years since smoking cessation and self-reported history of emphysema). We selected these variables based on a previously published model(5). We excluded 368 NLST participants with missing data for any of these variables. Since the transition from smoker to lung cancer did not satisfy the proportional hazard assumption, as the difference in lung cancer diagnoses between screening conditions occurred mostly within the first year post randomization, participants were stratified on initial screening assignment. The proportional hazards assumption was also checked for all other included variables over each of the 4 transitions by examining the correlation of the Schoenfeld residuals with time. Proportionality in the 7-year follow-up data was generally not rejected, nor was there any evidence of a consistent non-significant trend for diminishing or strengthening predictor effects over time.

To evaluate model performance, we constructed calibration plots under each screening condition for the observed proportions of outcome events against the predicted risks for individuals grouped by quintiles (20% cohorts) of risk. We used the concordance statistic (c-statistic) to assess model discrimination. All analyses were performed using R version 3.3.2 and SAS 9.3 (SAS institute, Cary NC).

Benefits

We estimated benefits for each participant as the incremental model-projected health outcomes following LDCT screening compared to chest X-ray screening. We used the multi-state model to project potential outcomes for each subject through year-7 post-randomization. We extrapolated subsequent survival conditional on survival to year-7 using a Weibull distribution (Appendix Figure 1). Health outcomes included life expectancy and quality-adjusted life expectancy under each screening condition for each individual. We computed the expected quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) as the sum of each health state’s contribution. Each state’s contribution was equal to the product of the expected years lived in that state and the state’s utility weight. The utility weights used were: 1.0 (equivalent to 1-year of perfect health) for the initial state of being alive without lung cancer, 0.77 for alive with lung cancer (the average utility for metastatic and non-metastatic lung cancer reported in a meta-analysis(15)) and 0.0 (equivalent to death).

Costs

Components of costs included the costs of initial screening, medical care utilization including diagnosis and management following a positive screening result and age-stratified background medical costs (Appendix Table 1 and 2)(14). We estimated initial screening costs and costs associated with a positive screening as the product of utilization data and unit prices (using 2016 Medicare reimbursement(16)). Utilization estimates came directly from the NLST, which recorded for each participant diagnostic and procedure codes pertinent to the screening, diagnosis and treatment of lung cancer. We focused on codes likely to have the greatest impact on incremental costs i.e. codes with frequency differences of 10 or more across the two arms of the trial. Our analysis included 35 diagnostic procedures, 13 treatment codes and 5 complication codes, in addition to costs for screening (Appendix Table 1).

These empirically derived incremental costs were used in a generalized linear regression equation, based on 9 characteristics (the 8 variables included in the risk model plus treatment arm (LDCT versus chest X-ray), to predict each individual patient’s expected incremental costs (expected cost with LDCT minus expected cost with chest x-ray).

Analysis

Cost-effectiveness analyses assessed the comparative value of screening with LDCT versus chest X-ray for each participant using incremental cost effectiveness ratios (ICER). We calculated the ICER for each patient as the predicted incremental cost of screening with LDCT compared to X-ray divided by the predicted incremental benefits of LDCT. All analyses were performed from the healthcare sector perspective and all future life-years and costs were discounted at 3%(17).

We calculated the iNMB of a risk targeted screening strategy compared to the best strategy applied to all participants enrolled in the NLST. The iNMB provides a useful summary of both the health and the economic gains of an intervention by expressing them on the same scale, converting net health benefits into monetary terms (multiplying incremental QALYs by the WTP threshold(18)). Here, in addition to determining the “conversion rate” for a QALY, the WTP threshold also determines the lung cancer mortality risk threshold at which the more expensive screening technology (LDCT) is deemed cost effective. Risk targeting improves cost-effectiveness by switching those patients above or below this risk threshold to (or from) LDCT for whom the switch accrues a positive iNMB (i.e. for whom the switch is cost-effective at a given WTP threshold). We used the commonly applied WTP thresholds of $50,000 or $100,000 per QALY(13). The per-patient iNMB is the aggregate gain across all switched individuals divided by the number of individuals screened.

Sensitivity Analyses

We assessed the influence of alternative assumptions on the model-projected cost-effectiveness: 1-LDCT provides continually accruing lung cancer mortality gains by extrapolating the reduced hazard of lung cancer mortality throughout the patient’s lifetime (Appendix Figure 1); 2-removal of age-specific background medical costs; and 3. assign utility weights of 0.57 or 1.0 following a diagnosis of lung cancer (base case=0.77)(15).

Results

Multi-state Prediction Model and Study Population

Appendix Table 3 summarizes the multistate regression model; risk factors and their associated hazard ratios are shown for lung cancer incidence, lung cancer death and competing causes of death. Transition-specific discrimination measured by the c-statistic ranged from 0.61 (95% CI 0.59–0.63) for lung cancer to death to 0.70 (95% CI 0.68–0.72) for progression from the healthy state to a diagnosis of lung cancer. There was excellent agreement between model-predicted outcomes (including lung cancer diagnosis, lung cancer mortality and non-lung cancer mortality) and those observed within the trial period (Appendix Figure 2).

After stratifying the 53,086 NLST participants by their baseline risk of lung cancer mortality, the highest-risk versus lowest-risk quintile participants were on average 8-years older; more likely to be white; be male; have a positive family history of lung cancer; be a current smoker with a 30 pack-year or greater exposure and have an underlying diagnosis of emphysema (Table 1).

Table 1:

Baseline characteristics of patients according to quintiles of risk of death from lung cancer.

| Characteristics | Quintile 1 | Quintile 2 | Quintile 3 | Quintile 4 | Quintile 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=10617 | N=10617 | N=10617 | N=10617 | N=10618 | |

| Age - yr | |||||

| Mean +/− SD | 58.3 +/− 3.0 | 59.6 +/− 4.1 | 60.4 +/− 4.6 | 62.4 +/− 4.5 | 66.4 +/− 4.5 |

| Interquartile Range | 56–60 | 56–63 | 57–63 | 59–65 | 63–70 |

| Sex | |||||

| Male (%) | 5655 (53) | 5858 (55) | 6217 (59) | 6565 (62) | 7064 (67) |

| BMI | |||||

| Mean +/− SD | 30.2 +/− 5.4 | 29.1 +/− 4.9 | 27.6 +/− 4.7 | 26.8 +/− 4.4 | 25.8 +/− 4.4 |

| Interquartile Range | 26.4–33.1 | 25.8–31.8 | 24.4–30.0 | 23.7–29.2 | 23.0–28.1 |

| Race | |||||

| White (%) | 9183 (86) | 9555 (90) | 9643 (91) | 9627 (91) | 9731 (92) |

| Black (%) | 270 (2.5) | 424 (4.0) | 518 (4.9) | 603 (5.7) | 530 (4.9) |

| Hispanic (%) | 686 (6.5) | 153 (1.4) | 50 (0.5) | 27 (0.2) | 16 (0.1) |

| Other or unspecified (%) | 478 (4.5) | 485 (4.6) | 406 (3.8) | 360 (3.4) | 341 (3.2) |

| No. of first degree relatives | |||||

| 0 (%) | 8873 (84) | 8695 (82) | 8432 (79) | 8001 (75) | 7501 (71) |

| 1 (%) | 1580 (15) | 1700 (16) | 1892 (18) | 2208 (21) | 2462 (23) |

| ≥2 (%) | 164 (1.5) | 222 (2.1) | 293 (2.8) | 408 (3.8) | 655 (6.1) |

| Pack Years of Smoking | |||||

| Mean +/− SD | 45.3 +/− 14.3 | 48.6 +/− 17.0 | 52.4 +/− 18.5 | 59.4 +/− 21.7 | 74.1 +/− 32.2 |

| Interquartile Range | 34.5 – 52.5 | 37.0–58.0 | 39.6–61.5 | 43–72 | 50–90 |

| Year Since Smoking Cessation | |||||

| <1 or current (%) | 457 (4.3) | 4291 (40) | 6650 (63) | 7502 (71) | 8574 (81) |

| 1–4.9 (%) | 2082 (20) | 2686 (25) | 1846 (17) | 1594 (15) | 1338 (13) |

| ≥5 (%) | 8078 (76) | 3640 (34) | 2121 (20) | 1521 (14) | 706 (6.6) |

| Emphysema | |||||

| Yes (%) | 106 (1.0) | 256 (2.4) | 425 (4.0) | 886 (8.3) | 2412 (23) |

Health Benefit

The lung cancer mortality benefit from LDCT screening (compared to chest X-ray screening) increased with increasing baseline risk of death from lung cancer (Figure 2). For the lowest risk (decile 1), LDCT screening prevented 1.2 deaths from lung cancer per 10,000 person-years compared to 9.5 deaths from lung cancer per 10,000 person-years for patients at the highest risk (decile 10). Benefits also increased across increasing risk deciles when expressed as LYs gained (decile 1=0.015, decile 10=0.056) and QALYs gained (decile 1=0.011, decile 10=0.028)(Figure 2). Comparing the benefit gradient across risk groups, the extreme (highest to lowest) decile ratio was greatest in terms of lung cancer mortality benefits in the first seven years (ratio=7.9); the extreme decile ratio greatly attenuated when comparing LYs gained (ratio=3.6), with further attenuation when comparing QALYs gained (ratio=2.4)(Figure 2).

Figure 2: Mortality, Life Expectancy, Quality of Life benefits and ICER according to risk.

Participants were stratified by pre-screening risk of lung cancer mortality, decile 1 representing the lowest risk 10% of the screening cohort. A: Over the initial 7-year period of the study the difference in mortality benefits (number of prevented deaths per 10,000 person year follow up), life expectancy (LY) and quality of life (QALY) between screening with low dose CT versus chest X-ray was calculated. Particpants with the greatest pre-screening risk of lung cancer mortality had the greatest benefit in mortality when screened with LDCT (extreme decile ratio of 7.9), however the gradient of benefit was attenuated when accounting for life expectancy (extreme decile ratio of 3.6) and quality of life (extreme decile ratio of 2.4). B: The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) is calculated by the ratio of difference in costs and difference in incremental improvement in LY and QALY between screening with low dose CT versus chest X-ray. The ICER remains between $100,000/QALY and $50,000/QALY for all deciles of risk.

Costs and Incremental Cost-Effectiveness

Screening with LDCT increased lifetime costs by $1089 versus screening with chest X-ray, yielding an ICER for LDCT of $37,000/LY gained or $60,000/QALY gained in the overall NLST cohort.

When examined across risk-strata, incremental costs for LDCT increased with rising baseline lung cancer mortality risk (Appendix Figure 3). Among patients with the lowest lung cancer mortality risk, the incremental cost of LDCT largely reflected the difference in the cost of screening ($254 for LDCT and $42 for X-ray). In contrast, besides the higher costs associated with more lung cancer diagnoses, higher risk patients had more invasive testing following a positive screen, generating additional costs (Appendix Table 4). Among higher risk patients, the higher incremental costs ($1500 for decile 10 compared to $890 for decile 1) offset the higher incremental benefits to yield similar ICERs across risk deciles. For the lowest risk decile, the ICER was $75,000/QALY, compared to $53,000/QALY for the highest risk decile (Figure 2).

Because no participant generated an ICER above $100,000/QALY, screening all participants with LDCT was cost-effective at this threshold. Conversely, no participant generated an ICER below $50,000/QALY, so LDCT screening was not cost-effective for any participant at this lower threshold. At both thresholds using either the risk targeted approach or the NLST inclusion criteria screening strategy yield identical decisions, with no aggregate savings (i.e. iNMB=0).

Sensitivity Analyses

When extrapolating ongoing benefits of screening with LDCT beyond year-7, the overall ICER for LDCT decreases; LDCT becomes the preferred screening strategy at the $50,000/QALY threshold. A risk-stratified approach yields the same screening decision, generating no savings above the NLST inclusion criteria at both WTP thresholds (Table 2). Removal of background costs or removal of disutility (utility weight=1.0) for LDCT screening also improved the overall cost-effectiveness of LDCT (to $43,000/QALY and $37,000/QALY respectively), making it the preferred screening strategy at the $50,000/QALY threshold. Risk-stratification identified some low risk participants who were not cost–effective to screen with LDCT under these scenarios at the lower WTP threshold (22% in the former and 15% in the latter case). Nevertheless, the per patient iNMB were relatively modest, indicating that the savings from avoiding LDCT in these low risk patients were similar in value to the QALYs lost (Table 2). At the $100,000/QALY threshold, LDCT remained cost-effective in these scenarios. When assigning a utility of 0.57 following a diagnosis of lung cancer, screening with LDCT was more cost effective in the low risk patients compared to the high risk patients, but was not cost effective for any participant at either WTP thresholds. The iNMB for risk targeting remains low for all two- and three-way sensitivity analyses (Appendix Table 5).

Table 2:

Sensitivity Analyses

| Average ICER/QALY | Lowest Risk Decile ICER | Highest Risk Decile ICER | % Screened with LDCT at $50,000 threshold | iNMB per patient at $50,000 per QALY Threshold | % Screened with LDCT at $100,000 threshold | iNMB per patient at $100,000 per QALY Threshold | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base Case | $60,000 | $75,000 | $53,000 | 0% | $0 | 100% | $0 |

| Sustained mortality benefits of LDCT post year 7 | $24,000 | $28,000 | $22,000 | 100% | $0 | 100% | $0 |

| Removal of Background Costs | $43,000 | $62,000 | $31,000 | 78% | $20 | 100% | $0 |

| Utility Weight of 1.0 following lung cancer diagnosis | $37,000 | $57,000 | $27,000 | 85% | $12 | 100% | $0 |

| Utility Weight of 0.57 following lung cancer diagnosis | $125,000 | $102,000 | $365,000 | 0% | $0 | 0% | $0 |

iNMB= incremental net monetary benefit

Discussion:

Consistent with prior findings(5–7), we demonstrated that participants at the highest baseline risk of death from lung cancer gained the greatest benefit in terms of LDCT-prevented lung cancer deaths in the first 7 years following screening initiation; 80% of lives saved can be obtained by targeting the highest risk 60%. However, higher risk participants were older with greater smoking exposure and more likely to have a pre-existing diagnosis of COPD, the gradient of benefit across risk strata was greatly attenuated when expressed as life-years and QALYs over a lifetime time horizon. Additionally, participants who were at higher risk of lung cancer also generated higher lung cancer screening costs owing to more invasive testing following a positive screen. Thus, the cost-effectiveness of screening lower risk patients meeting NLST criteria was similar to screening higher risk participants. An individualized risk-targeted approach to participant selection for screening proved no more cost-effective than the broader NLST inclusion criteria at common WTP thresholds of $50,000 and $100,000 per QALY gained.

When testing our model assumptions, in most scenarios, the cost-effectiveness of NLST-based screening and individualized (risk-based) screening strategies yielded the same decisions, either screen all with LDCT or screen all with chest X-ray, depending on the WTP threshold. Even in sensitivity analyses in which LDCT screening was cost-effective for some high-risk participants and not for low-risk participants, individualizing decisions did not yield substantial benefits, because the trade-offs involved exchanging costs and QALYs that were near-equivalent in value. Under the sensitivity analysis applying lower utility weights after a diagnosis of lung cancer reduced the health benefits of cancer detection, high-risk participants actually were less cost effective to screen than low-risk participants.

When making their screening recommendations, both the USPSTF(2) and the American Cancer Society(3) have largely adopted the inclusion criteria of the NLST to determine screening eligibility. Several analyses using a variety of pre-screening risk-prediction models have argued that individual risk-based selection of participants would substantially improve efficiency compared to the broader screening approach applying the NLST or the USPSTF criteria(5–8). Katki et al. demonstrated that applying a risk-prediction model similar to the one examined in our study to preferentially screen the highest-risk participants could lead to a 20% increase in the number of lung cancer deaths prevented over a 5-year period without any increase in the number of patients screened(6). These authors assumed that the short-term benefits seen in terms of LDCT-prevented lung cancer deaths translate into long-term survival benefits. However, our analysis demonstrates that each older, higher risk person with greater co-morbidities surviving lung cancer because of screening accrues fewer additional life-years compared to each younger, healthier, lower risk survivor. Additionally, because a lung cancer diagnosis has a substantial impact on the quality of life among survivors, the absolute magnitude of the benefit gradient between higher and lower risk participants is smaller when expressed as QALYs. Our analysis did not account for reductions in quality of life due to the greater burden of non-lung-cancer disease in higher risk participants (such as COPD and non-pulmonary tobacco-related comorbidities); if included, we anticipate further attenuation of the gradient of benefit of screening high risk participants compared to low risk participants.

Although the overall estimate of the ICER from our study of $60,000/QALY is lower than the $81,000/QALY seen in a prior economic analysis by Black et al.(19), their analysis compared LDCT with no screening. When adjusting their estimates for the incremental cost of screening with chest X-ray their ICERs are almost identical to ours. When Black et al. attempted to apply a validated lung cancer risk model(5) to their trial-based empirical economic evaluation, their results were too unstable to produce reliable cost effectiveness estimates in the risk strata, due to the low and imprecisely estimated mortality rates in 5 risk subgroups and two treatment arms. Our multi-state model was designed to address this instability(20,21).

Currently, implementation of lung cancer screening requires a clinician to identify a high-risk smoker, counsel the patient on the harms and benefits of screening in addition to smoking cessation counseling to maximize screening benefits(22). Implementation of screening has been shown to be limited(23), with concerns raised that using risk models to determine screening eligibility may further complicate and impede screening implementation(24,25). Our analysis suggests that the gains from such risk-based eligibility are likely to be small when extrapolated over the longer term, assuming perfect implementation of the two competing strategies.

Proposed as a general approach to examine heterogeneity of effects for better treatment targeting(26,27), risk-stratification has been demonstrated to increase the absolute risk difference of the primary outcome in many trials across a wide variety of conditions (higher risk patients generally obtain more absolute benefit)(5–6,28–30). Our analysis provides a caution that this strategy may have limitations when benefits beyond the primary outcome of the study are evaluated, especially across a lifetime time horizon(31). When risk factors for the primary outcome (in this case lung cancer mortality) impact mortality from other causes, the attenuation of the gradient of benefit seen across risk will likely occur. Risk-modeling provides an important strategy for examining heterogeneity of treatment effects to optimize treatment decisions(28); our analysis suggests this approach will not always substantially improve cost-effectiveness, even when absolute treatment benefits appear to be heterogeneous within the trial, so the specifics of each analysis will matter greatly.

Limitations

Our findings regarding the similar cost-effectiveness of screening NLST-high-risk and NLST-low-risk participants depend on certain model assumptions. Our model relies on the conventional assumption of a constant relative effect across risk groups; while this appears empirically justified(5), we acknowledge that the NLST was under-powered to precisely estimate screening effectiveness in every subgroup, particularly those at low risk. While our prediction model has not been externally validated, any decrease in model performance is likely to further attenuate the gradient between the highest and lowest risk participants, further degrading the usefulness of risk-targeting. Additionally, our model did not account for different tumor types, grades and stage. While it has been empirically shown that the effectiveness (in terms of relative risk reduction of lung cancer mortality) appears not to differ between risk strata(5), and we estimated risk-specific costs, we could not account for risk-correlated differences in tumor type, grade and stage that may differentially affect quality of life for the lung cancer diagnosis. We also did not account for the impact of non-cancer-related illness on utility weights, which would make high-risk patients relatively less favorable to screen compared to low risk patients. Nevertheless, aside from quality of life estimates, our model rigorously incorporated the relevant differences between higher and lower risk participants for each aspect of the analysis (i.e. short-term benefits, life expectancy and costs). The importance of congruent levels of granularity for these analyses has recently been emphasized(31).

There are also limitations to our overall estimate of cost-effectiveness. Our findings are based on data from the NLST, which compared LDCT to chest x-ray. The Prostate Lung Colorectal and Ovarian (PLCO) cancer screening trial has previously demonstrated that chest X-ray as a screening modality does not effectively reduce lung cancer mortality(32). Hence, our ICERs may be more favorable than they otherwise would have been if we had compared LDCT to no screening at all. Second, our ICER estimates do not extrapolate outside the NLST population and reflect the NLST screening protocol, which calls for three annual screens; whereas the current USPSTF recommendations broaden the inclusion criteria in terms of age and duration of annual screening(2). Finally, our estimates do not reflect quality of life gains from the diagnosis and treatment of incidental findings, such as emphysema and coronary artery calcification, the true costs and benefits of which have not yet been determined. Despite enrollment into the NLST starting in 2002, we believe that the findings continue to be generalizable, particularly given the strength of the exposure-response relationship between the heavy tobacco use required for enrollment and both lung cancer and cardio-pulmonary mortality(33).

Conclusion:

We confirmed prior work that demonstrate increased number of early lung cancer deaths can be averted per patient screened by applying more granular risk targeting than the overall inclusion criteria of the NLST. However, higher risk patients are more costly to screen and also have a lower life-expectancy should they survive lung cancer. Thus, applying such a risk model is unlikely to lead to substantial improvement in the cost-effectiveness of LDCT screening in terms of quality adjusted life years gained per unit cost.

Supplementary Material

Appendix Figure 1:

A: Cumulative Baseline Hazard of Extrapolated Multi-state Model

Healthy to cancer (Transition 1)

The transition from healthy smoker to cancer did not satisfy the proportional hazard assumptions. To model this transition the observed cumulative hazard by low dose CT (LDCT) and chest X-ray up to year 7 post randomization. A Weibull extrapolation, stratified by LDCT and chest X-ray was used beyond year 7 post randomization. When the cumulative hazard of a diagnosis of lung cancer by chest X-ray exceeded that of LDCT, a Weibull extrapolation based on screening with chest X-ray alone was used.

Healthy to other death (Transition 2)

The transition from healthy smoker to death from non-lung cancer related causes was modeled using the observed cumulative hazard up to year 7 post randomization, including a proportional CT vs. X-ray effect. A Weibull extrapolation, with a doubled shape parameter, based on the cumulative hazard of death from non-lung cancer related causes when screened with chest X-ray was used beyond year 7 post randomization.

Cancer to other death (Transition 3)

The transition from lung cancer to death from non-lung cancer related causes was modeled using the observed cumulative hazard up to year 7 post randomization, including a proportional CT vs. X-ray effect. A Weibull extrapolation based on the cumulative hazard of death from non-lung cancer related causes when screened with chest X-ray alone was used beyond year 7 post randomization.

Cancer to cancer death (Transition 4)

The transition from lung cancer to death from lung cancer was modeled using the observed cumulative hazard up to year 7 post randomization, including a proportional CT vs. X-ray effect. A Weibull extrapolation based on the cumulative hazard of death from lung cancer related causes when screened with chest X-ray alone was used beyond year 7 post randomization.

B. Sensitivity Analysis for Transition 4

Our base case assumes that the lung cancer mortality benefits seen when screening with LDCT is only present over the median follow up of the trial i.e. 7 years. The subsequent Weibull extrapolation has the same hazard ratio of death from lung cancer as that in patient undergoing screening with chest X-ray. Our sensitivity analysis tested this assumption by extrapolating ongoing improved survival of screening with LDCT past year 7.

Appendix Figure 2: Calibration between observed and predicted values

Participants were stratified by their pre-screening risk of death from lung cancer (quintile 1= low risk and quintile 5 = high risk). The predicted and observed proportion of patients in each multistate transition in a given year was calculated for each patient. A: Represents a calibration plot of predicted and observed outcomes in patients screened with chest X-ray. B: Represents a calibration plot of observed and predicted outcomes for patients screened with low dose CT. C: Table represents the overall concordance index (c-index) for each transition in the multi-state model. Transition 1 was stratified by screening assignment. The prediction model was well calibrated and there was good internal validity between the observed and predicted transition probabilities.

Appendix Figure 3: Costs according to risk

Participants were stratified by pre-screening risk of lung cancer mortality, decile 1 representing the lowest risk 10% of the screening cohort. The average cost of screening, diagnosis and management per patient increases with baseline risk of lung cancer mortality.

Acknowledgement:

We would also like to thank Christine Lundquist, Tara Lavelle, David Kim and Robin Ruthazer (Institute for Clinical Research and Health Policy Studies, Tufts Medical Center, Boston, MA) for their contributions.

Funding Source: U.S. National Institute of Health (U01NS086294)

Role of the Funding Source

The work was funded by the US National Institute of Health (U01NS086294). The funding source had no role in the design or conduct of the study and no role in the decision to submit for publication.

IRB Approval: This study was approved for exemption by the Tufts Institutional Review Board.

Appendix A

Appendix Table 1:

Screening, Diagnosis, Treatment and Complication Costs

| NLST Dataset Code | Screening Procedure | Total Cost ($) |

|---|---|---|

| Study arm: 2 = CXR | Posteroanterior chest x-ray | 42.25 |

| Study arm: 1 = CT | Spiral CT | 254.57 |

| NLST Dataset Code | Diagnostic Procedure | Total Cost ($) |

| 1 | Biopsy - Endobronchial | 403.87 |

| 2 | Biopsy - Percutaneous liver | 369.86 |

| 9 | Biopsy - Open Surgical | 502.33 |

| 10 | Biopsy - Transbronchial | 403.87 |

| 11 | Radiograph - Bone | 64.81 |

| 13 | Radiograph - Chest | 27.93 |

| 14 | Clinical Evaluation | 78.05 |

| 15 | Radiograph - Comparison with historical images | 11.10 |

| 17 | CT - Abdomen and pelvis | 313.29 |

| 23 | CT - Chest, limited thin section of nodule | 277.13 |

| 25 | Cytology - Sputum | 16.47 |

| 29 | Lymphadenectomy/lymph node sampling | 475.48 |

| 31 | MRI - Bone | 386.87 |

| 32 | MRI - Brain | 159.45 |

| 33 | MRI - Chest | 487.18 |

| 39 | Pulmonary function tests/spirometry | 42.50 |

| 43 | Resection | 10687.00 |

| 46 | Thoracotomy | 10687.00 |

| 49 | Thoracoscopy | 321.16 |

| 50 | Biopsy - Thoracoscopic | 393.85 |

| 53 | Biopsy - Percutaneous transthoracic yielding histology | 458.30 |

| 54 | Bronchoscopy without biopsy or cytology | 182.60 |

| 55 | CT - Abdomen (or liver) | 264.24 |

| 56 | CT - Chest, plus nodule densitometry | 277.13 |

| 57 | CT - Diagnostic chest | 277.13 |

| 58 | Cytology - Bronchoscopic | 322.60 |

| 61 | Echocardiography | 199.25 |

| 62 | MRI - Abdomen (or liver) | 434.07 |

| 63 | Radionuclide scan - FDG-PET scan* | 1220.00 |

| 66 | Radionuclide scan - Ventilation/perfusion lung | 349.81 |

| 68 | Radionuclide scan - Fusion PET/CT scan | 1220.00 |

| 69 | CT - Chest, low dose spiral | 254.57 |

| 70 | CT - Chest limited thin section of entire lung | 277.13 |

| 71 | CT - Chest and abdomen | 463.31 |

| 72 | CT - Chest, abdomen, and pelvis | 691.03 |

| NLST Dataset Code | Treatment Procedure | Total Cost ($) |

| 101 | Radiation of Primary Chest Tumor and/or Regional Nodes | 3843.68 |

| 102 | Radiation of Hilar/Mediastinal Lymph Nodes | 3843.68 |

| 103 | Radiation of Prophylactic Brain | 3843.68 |

| 104 | Radiation of Therapeutic Brain | 3843.68 |

| 203 | Lobectomy | 10687.00 |

| 205 | Pneumonectomy | 10687.00 |

| 206 | Wedge Resection | 10687.00 |

| 208 | Lymphadenectomy/Lymph Node Sampling | 475.48 |

| 212 | Multiple Wedge Resections | 10687.00 |

| 214 | Thoracotomy | 10687.00 |

| 215 | Thoracoscopy (VATS) | 321.16 |

| 216 | Thoracoscopy (VATS) with conversion to Thoracotomy | 11008.16 |

| 300 | Systemic Chemotherapy | 15826.92 |

| NLST Dataset Code | Complication | Total Cost ($) |

| 1 | Acute respiratory failure | 9895.00 |

| 17 | Hospitalization post procedure | 4744.00 |

| 23 | Pneumothorax requiring tube placement | 14273.00 |

| 29 | Bronchial stump leak requiring tube thoracostomy or other drainage for >4 days | 29522.00 |

| 31 | Injury to vital organ or vessel | 9895.00 |

The estimation of costs were based on 2016 Medicare reimbursement values for International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnostic codes, Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) procedural codes, and Medical Severity Diagnosis Related Groups (MS-DRG) codes that were documented by the NLST investigators during the course of the trial. Our analysis focused on codes with greater than 10difference in frequency between chest X-ray and LDCT.

2016 National Medicare price listing was not available for PET scan, thus price listed is institution specific reimbursement for PET scan and similar in values to prior published US cost estimates for PET scan(17).

Appendix Table 2:

Background Costs

| Age Range | Average annual health expenditure |

|---|---|

| 0 – 24 years | $1828/year |

| 25 – 34 years | $2728/year |

| 45 – 54 years | $5039/year |

| 55 – 64 years | $7780/year |

| 65 – 74 years | $9814/year |

| 75 – 99 years | $12037/year |

Appendix Table 3:

Transitional Hazard Ratios for the Multistate Prediction Model.

| Transition 1: Smoker to Lung Cancer (n=53,086)* | Transition 2: Smoker to non-lung cancer death (n=53,086)* | Transition 3: Lung cancer to non-lung cancer death (n=2079)* | Transition 4: Lung Cancer to lung cancer death (n=2079)* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk Factor | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) |

| Age | 1.084 (1.075–1.092) | 1.086 (1.079–1.094) | 1.053 (1.009–1.099) | 1.008 (0.996–1.021) |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) † | ||||

| - Normal BMI | 0.923 (0.865–0.985) | 0.840 (0.809–0.873) | 0.888 (0.694–1.138) | 0.964 (0.902–1.030) |

| - Elevated BMI | 1.001 (1.000–1.002) | 1.003 (1.002–1.004) | 1.002 (0.998–1.006) | 1.001 (1.000–1.002) |

| Male Sex | 0.994 (0.908–1.08) | 1.787 (1.642–1.944) | 2.079 (1.259–3.432) | 1.296 (1.134–1.482) |

| Family History of Lung Cancer | 1.237 (1.145–1.337) | 1.010 (0.938–1.087) | 0.876 (0.577–1.330) | 0.963 (0.860–1.079) |

| Smoking Exposure (Per Pack Year) | 1.009 (1.008–1.011) | 1.006 (1.005–1.007) | 0.995 (0.986–1.004) | 1.002 (0.999–1.004) |

| Years since smoking cessation | 0.685 (0.648–0.725) | 0.739 (0.706–0.774) | 0.864 (0.649–1.151) | 0.809 (0.744–0.880) |

| Diagnosis of Emphysema | 1.576 (1.391–1.785) | 1.638 (1.470–1.825) | 0.779 (0.400–1.519) | 1.072 (0.903–1.272) |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| - White | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) |

| - Black | 1.278 (1.045–1.561) | 1.897 (1.640–2.194) | 0.909 (0.325–2.542) | 0.861 (0.641–1.156) |

| - Hispanic | 0.498 (0.309–0.803) | 1.025 (0.770–1.365) | 0.981 (0.134–7.162) | 0.601 (0.268–1.346) |

| - Other | 0.890 (0.702–1.128) | 1.074 (0.891–1.294) | 0.293 (0.040–2.123) | 1.028 (0.724–1.460) |

The proportional hazards assumption was met for all risk factors. For transition 1, smoking to lung cancer, further stratification was performed with separate hazard ratio (HR) based on screening with either low dose CT (LDCT) or chest x-ray.

The sample sizes correspond to the number of participants at risk of the health state transition over the trial period. The outcomes for each transition over the trial period were: Transition 1 - Smoker to Lung Cancer: N=2079; Transition 2- Smoker to non-lung cancer death: N=2830; Transition 3 - Lung cancer to non-lung cancer death: N=82; and Transition 4 - Lung Cancer to lung cancer death: N=1082.

Body Mass Index (BMI) was centered at 25 and the hazard ratios are for increase of 5.

Appendix Table 4:

Positive Screen Rate, Investigation Methods and Lung Cancer Diagnosis according to quintiles of risk

| Variable | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=5314 | % | n=5314 | % | n=5314 | % | n=5314 | % | n=5313 | % | |

| Positive Screen | 1462 | 28 | 1640 | 30.8 | 1721 | 32.3 | 1809 | 34 | 2155 | 41 |

| Lung Cancer | 56 | 1 | 106 | 2 | 148 | 2.8 | 238 | 4.5 | 407 | 7.7 |

| Method of investigation | % Positive Screen | % Positive Screen | % Positive Screen | % Positive Screen | % Positive Screen | |||||

| Clinical Evaluation or Plain radiographs | 1256 | 85.9 | 1441 | 87.9 | 1522 | 88.4 | 1611 | 89.1 | 1972 | 91.5 |

| CT | 1171 | 80.1 | 1336 | 81.5 | 1373 | 79.8 | 1440 | 79.6 | 1757 | 81.5 |

| MRI | 54 | 3.7 | 62 | 3.8 | 69 | 4.0 | 87 | 4.8 | 117 | 5.4 |

| PET-CT | 193 | 13.2 | 221 | 13.5 | 249 | 14.5 | 342 | 18.9 | 527 | 24.5 |

| Close Biopsy | 43 | 2.9 | 58 | 3.5 | 60 | 3.5 | 105 | 5.8 | 173 | 8.0 |

| Invasive Procedure | 111 | 7.6 | 146 | 8.9 | 168 | 9.8 | 249 | 13.8 | 384 | 17.8 |

21,269 participants included in our analysis underwent screening with Low dose CT (LDCT) in the National Lung Screening Trial (NLST). Each participant was stratified into quintiles (Q1 (lowest risk) to Q5 (highest risk)) based on their baseline 7-year risk of lung cancer mortality according to our multi-state model. Using empirically derived data from the NLST, participants at the highest risk quintile (Q5) were more likely to have a LDCT screen classified as ‘positive’ according to the NLST protocol. High-risk participants were more likely to receive a diagnosis of lung cancer (both screen and non-screening detected). High-risk participants were also more likely to have more invasive testing as a follow up for a positive screen.

Appendix Table 5:

Expanded Sensitivity analyses with combination of multiple parameters

| Removal of Background costs | Sustained mortality benefits of LDCT post year-7 | Utility weight following cancer diagnosis | Average ICER ($/QALY) | Lowest Risk Decile ICER | Highest Risk Decile ICER | % screened with LDCT at $50K per QALY threshold | iNMB per patient at $50K per QALY threshold | % screened with LDCT at $100K per QALY threshold | iNMB per patient at $100K per QALY threshold | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One-way sensitivity analyses | ||||||||||

| Base Case | No | No | 0.77 | $60,000 | $75,000 | $53,000 | 0% | $0 | 100% | $0 |

| Sustained mortality benefits of LDCT post year 7 | No | Yes | 0.77 | $24,000 | $28,000 | $22,000 | 100% | $0 | 100% | $0 |

| Removal of Background Costs | Yes | No | 0.77 | $43,000 | $62,000 | $31,000 | 78% | $20 | 100% | $0 |

| Utility weight 1.0 following lung cancer diagnosis | No | No | 1 | $37,000 | $57,000 | $27,000 | 85% | $12 | 100% | $0 |

| Utility weight 0.57 following lung cancer diagnosis | No | No | 0.57 | $125,000 | $102,000 | $365,000 | 0% | $0 | 0% | $0 |

| Two-way sensitivity analyses | ||||||||||

| Yes | Yes | 0.77 | $8,500 | $14,000 | $5,800 | 100% | $0 | 100% | $0 | |

| Yes | No | 1 | $27,000 | $47,000 | $16,000 | 3% | $0.51 | 100% | $0 | |

| Yes | No | 0.57 | $90,000 | $84,000 | $210,000 | 0% | $0 | 87% | $47 | |

| No | Yes | 1 | $17,000 | $21,000 | $16,000 | 100% | $0 | 100% | $0 | |

| No | Yes | 0.57 | $34,000 | $38,000 | $36,000 | 100% | $0 | 100% | $0 | |

| Three-way sensitivity analyses | ||||||||||

| Yes | Yes | 1 | $6,200 | $11,000 | $4,000 | 100% | $0 | 100% | $0 | |

| Yes | Yes | 0.57 | $12,000 | $19,000 | $9,300 | 100% | $0 | 100% | $0 |

iNMB= incremental net monetary benefit

References:

- 1.The National Lung Screening Trial Research Team*. Reduced Lung-Cancer Mortality with Low-Dose Computed Tomographic Screening. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(5):395–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moyer Virginia A. on behalf of the USPSTF. Screening for lung cancer: U.S. preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(5):330–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wender R, Fontham E, Barrera E, Colditz G, Church T, Ettinger D, et al. American Cancer Society lung cancer screening guidelines. CA Cancer J Clin [Internet]. 2013;63:106–17. Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.3322/caac.21172/full?dmmsmid=68240&dmmspid=19343146&dmmsuid=1810980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jaklitsch MT, Jacobson FL, Austin JHM, Field JK, Jett JR, Keshavjee S, et al. The American Association for Thoracic Surgery guidelines for lung cancer screening using low-dose computed tomography scans for lung cancer survivors and other high-risk groups. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg [Internet]. 2012;144(1):33–8. Available from: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.05.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kovalchik SA, Tammemagi M, Berg CD, Caporaso NE, Riley TL, Korch M, et al. Targeting of low-dose CT screening according to the risk of lung-cancer death. N Engl J Med [Internet]. 2013;369(3):245–54. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3783654&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Katki HA, Kovalchik SA, Berg CD, Cheung LC, Chaturvedi AK. Development and Validation of Risk Models to Select Ever-Smokers for CT Lung Cancer Screening. Jama [Internet]. 2016;20892(21):1–12. Available from: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?doi=10.1001/jama.2016.6255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tammemägi MC, Katki HA, Hocking WG, Church TR, Caporaso N, Kvale PA, et al. Selection Criteria for Lung-Cancer Screening. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(8):728–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.ten Haaf K, Jeon J, Tammemägi MC, Han SS, Kong CY, Plevritis SK, et al. Risk prediction models for selection of lung cancer screening candidates: A retrospective validation study. PLOS Med [Internet]. 2017;14(4):e1002277 Available from: http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van der Aalst CM, ten Haaf K, de Koning HJ. Lung cancer screening: latest developments and unanswered questions. Lancet Respir Med [Internet]. 2016;4(9):749–61. Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2213260016302004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanchez-Salcedo P, Wilson DO, De-Torres JP, Weissfeld JL, Berto J, Campo A, et al. Improving selection criteria for lung cancer screening: The potential role of emphysema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191(8):924–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Putter H, Fiocco M, Geskus RB. Tutorial in biostatistics: Competing risks and multi-state models. Stat Med. 2007;26(11):2389–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Wreede LC, Fiocco M, Putter H. The mstate package for estimation and prediction in non- and semi-parametric multi-state and competing risks models. Comput Methods Programs Biomed [Internet]. 2010;99(3):261–74. Available from: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2010.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neumann PJ, Cohen JT, Weinstein MC. Updating Cost-Effectiveness - The Curious Resilience of the $50,000-per-QALY Threshold. N Engl J Med [Internet]. 2014;371(9):796–7. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25162885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neumann PJ, Ganitas TG, Russell LB, Sanders GD, Siegel J. Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine - Second Edition Second Edi. Oxford; 2016. Appendix A. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sturza J A Review and Meta-Analysis of Utility Values for Lung Cancer. Med Decis Mak [Internet]. 2010;30(6):685–93. Available from: http://mdm.sagepub.com/cgi/doi/10.1177/0272989X10369004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers of Medicare and Medicaid Services. Physician Fee look-up tool. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/PFSLookup/.2016.

- 17.Sanders GD, Neumann PJ, Basu A, Brock DW, Feeny D, Krahn M, et al. Recommendations for Conduct, Methodological Practices, and Reporting of Cost-effectiveness Analyses. Jama [Internet]. 2016;316(10):1093 Available from: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?doi=10.1001/jama.2016.12195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim JJ, Campos NG, Sy S, Burger EA, Cuzick J, Castle PE, et al. Inefficiencies and high-value improvements in U.S. cervical cancer screening practice: A cost-effectiveness analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(8):589–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Black WC, Gareen IF, Soneji SS, Sicks JD, Keeler EB, Aberle DR, et al. Cost-effectiveness of CT screening in the National Lung Screening Trial. N Engl J Med [Internet]. 2014;371(19):1793–802. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25372087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williams C, Lewsey JD, Mackay DF, Briggs AH. Estimation of Survival Probabilities for Use in Cost-Effectiveness Analyses: A Comparison of a Multi-State Modeling Survival Analysis Approach with Partitioned Survival and Markov Decision-Analytic Modeling. Med Decis Mak [Internet]. 2016;0272989X16670617. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27698003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Williams C, Lewsey JD, Briggs AH, Mackay DF. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis in R Using a Multi-state Modeling Survival Analysis Framework : A Tutorial. Med Decis Mak. 2016;1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goffin JR, Flanagan WM, Miller AB, Fitzgerald NR, Memon S, Wolfson MC, et al. Cost-effectiveness of Lung Cancer Screening in Canada. JAMA Oncol [Internet]. 2015;1(6):807 Available from: http://oncology.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?doi=10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.2472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kinsinger LS, Anderson C, Kim J, Larson M, Chan SH, King HA, et al. Implementation of Lung Cancer Screening in the Veterans Health Administration. 2017;27705. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Guessous I, Cornuz J. Why and how would we implement a lung cancer screening program? Public Health Rev [Internet]. 2015;36(1):1–12. Available from: 10.1186/s40985-015-0010-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goulart BH, Ramsey SD. Moving beyond the national lung screening trial: discussing strategies for implementation of lung cancer screening programs. Oncologist. 2013;18(8):941–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hayward RA, Kent DM, Vijan S, Hofer TP. Multivariable risk prediction can greatly enhance the statistical power of clinical trial subgroup analysis. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2006;6:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kent DM, Hayward R a. Limitations of applying summary results of clinical trials to individual patients. Jama. 2007;298:1209–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kent DM, Rothwell PM, Ioannidis JP a, Altman DG, Hayward R a. Assessing and reporting heterogeneity in treatment effects in clinical trials: a proposal. Trials [Internet]. 2010;11:85 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2928211/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rothwell PM, Warlow CP. Prediction of benefit from carotid endarterectomy in individual patients: A risk-modelling study. Lancet. 1999;353(9170):2105–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kent DM, Nelson J, Dahabreh IJ, Rothwell PM, Altman DG, Hayward RA. Risk and treatment effect heterogeneity: re-analysis of individual participant data from 32 large clinical trials. Int J Epidemiol [Internet]. 2016;(July):dyw118 Available from: http://ije.oxfordjournals.org/lookup/doi/10.1093/ije/dyw118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Klaveren D, Wong JB, Kent DM, Steyerberg EW. Biases in Individualized Cost-Effectiveness Analysis. Med Decis Mak [Internet]. 2017;0272989X1769699. Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0272989X17696994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oken MM, Hocking WG, Kvale P a., Andriole GL, Buys SS, Church TR, et al. Screening by Chest Radiograph and Lung Cancer Mortality. JAMA J Am Med Assoc [Internet]. 2011;306(17):1865–73. Available from: http://jama.ama-assn.org/content/early/2011/10/20/jama.2011.1591.abstract [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pope CA, Burnett RT, Turner MC, Cohen A, Krewski D, Jerrett M, et al. Lung cancer and cardiovascular disease mortality associated with ambient air pollution and cigarette smoke: Shape of the exposure-response relationships. Environ Health Perspect. 2011;119(11):1616–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix Figure 1:

A: Cumulative Baseline Hazard of Extrapolated Multi-state Model

Healthy to cancer (Transition 1)

The transition from healthy smoker to cancer did not satisfy the proportional hazard assumptions. To model this transition the observed cumulative hazard by low dose CT (LDCT) and chest X-ray up to year 7 post randomization. A Weibull extrapolation, stratified by LDCT and chest X-ray was used beyond year 7 post randomization. When the cumulative hazard of a diagnosis of lung cancer by chest X-ray exceeded that of LDCT, a Weibull extrapolation based on screening with chest X-ray alone was used.

Healthy to other death (Transition 2)

The transition from healthy smoker to death from non-lung cancer related causes was modeled using the observed cumulative hazard up to year 7 post randomization, including a proportional CT vs. X-ray effect. A Weibull extrapolation, with a doubled shape parameter, based on the cumulative hazard of death from non-lung cancer related causes when screened with chest X-ray was used beyond year 7 post randomization.

Cancer to other death (Transition 3)

The transition from lung cancer to death from non-lung cancer related causes was modeled using the observed cumulative hazard up to year 7 post randomization, including a proportional CT vs. X-ray effect. A Weibull extrapolation based on the cumulative hazard of death from non-lung cancer related causes when screened with chest X-ray alone was used beyond year 7 post randomization.

Cancer to cancer death (Transition 4)

The transition from lung cancer to death from lung cancer was modeled using the observed cumulative hazard up to year 7 post randomization, including a proportional CT vs. X-ray effect. A Weibull extrapolation based on the cumulative hazard of death from lung cancer related causes when screened with chest X-ray alone was used beyond year 7 post randomization.

B. Sensitivity Analysis for Transition 4

Our base case assumes that the lung cancer mortality benefits seen when screening with LDCT is only present over the median follow up of the trial i.e. 7 years. The subsequent Weibull extrapolation has the same hazard ratio of death from lung cancer as that in patient undergoing screening with chest X-ray. Our sensitivity analysis tested this assumption by extrapolating ongoing improved survival of screening with LDCT past year 7.

Appendix Figure 2: Calibration between observed and predicted values

Participants were stratified by their pre-screening risk of death from lung cancer (quintile 1= low risk and quintile 5 = high risk). The predicted and observed proportion of patients in each multistate transition in a given year was calculated for each patient. A: Represents a calibration plot of predicted and observed outcomes in patients screened with chest X-ray. B: Represents a calibration plot of observed and predicted outcomes for patients screened with low dose CT. C: Table represents the overall concordance index (c-index) for each transition in the multi-state model. Transition 1 was stratified by screening assignment. The prediction model was well calibrated and there was good internal validity between the observed and predicted transition probabilities.

Appendix Figure 3: Costs according to risk

Participants were stratified by pre-screening risk of lung cancer mortality, decile 1 representing the lowest risk 10% of the screening cohort. The average cost of screening, diagnosis and management per patient increases with baseline risk of lung cancer mortality.