Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

Dermatophytic infections are the common fungal infections aggravated by hot and humid climate. Terbinafine and itraconazole are commonly used oral antifungal agents for the same. However, resistance to these drugs is being seen increasingly when used in the conventional doses and duration. Therefore, this study was designed to compare the efficacy of terbinafine and itraconazole in increased dosages and duration in the treatment of tinea corporis and tinea cruris.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

In this randomized comparative study, patients of tinea cruris and tinea corporis were randomly divided into two groups of 160 each and were given oral terbinafine (Group I) and oral itraconazole (Group II) for 4 weeks. The scores and percentage change in scores of pruritus, scaling, and erythema were evaluated at 2 and 4 weeks.

RESULTS:

At the end of week 4, mycological cure was seen in 91.8% after 4 weeks in the itraconazole group as compared to 74.3% of patients in the terbinafine group. There was a significant improvement in percentage change in pruritus, scaling, and erythema in both the groups from 0 to 4 weeks. On comparing groups, the percentage change was significantly different in scaling from 0 to 2 weeks (5.4 vs. −4.8) and 2–4 weeks (16.7 vs. 29.6) between Group I and Group II, respectively. Clinical global improvement was better with itraconazole. Mild adverse effects such as gastrointestinal upset, headache, and taste disturbances were observed which were comparable in both the groups.

CONCLUSIONS:

Itraconazole and terbinafine seem to be equally effective and safe in the treatment of tinea cruris and tinea corporis.

Keywords: Efficacy, itraconazole, terbinafine, tinea corporis, tinea cruris

Introduction

Dermatophytic infections are the most common fungal infections affecting 20%–25% population globally.[1] The hot and humid climate in India favors dermatophytosis.[2] Terbinafine is considered to be a first-line drug for the treatment of tinea corporis and tinea cruris due to its favorable mycological and pharmacokinetic profile.[3] It acts by inhibiting the enzyme squalene epoxidase, thereby inhibiting ergosterol synthesis.[4] In the past, the drug was consistently effective against dermatophytosis with cure rates of >90% achieved at doses of 250 mg once a day for 2 weeks.[3,4]

Recently, there has been an increase in the incidence of terbinafine resistance with increasing numbers of clinical failures and relapses.[5,6] One of the principal mechanisms of antifungal resistance is a decrease in effective drug concentration.[7] Terbinafine was reported to be efficacious and safe in dermatophytosis with fewer failure rates at higher doses of 500 mg/day.[8]

Itraconazole is another antifungal drug which acts by inhibiting cytochrome P450-dependent enzyme, hence interfering with demethylation of lanosterol to ergosterol. It has shown good results in the treatment of dermatophytosis at doses of 100 mg once a day for 2 weeks and with 200 mg once a day for 7 days.[9,10] Because of frequent relapses at short intervals, some physicians have used it in doses of 200 mg once a day for prolonged periods.[11,12]

It has been observed recently that there has been widespread resistance to various antifungal agents used in conventional dose with an increase in relapse rates prompting a need to find an effective first-line antifungal drug and appropriate dosage and duration schedule to achieve maximum results with fewer relapses. Hence, the present study was conducted to compare the efficacy of oral terbinafine versus itraconazole in the treatment of tinea corporis and tinea cruris.

Materials and Methods

The study was performed in patients of both genders aged 18 years and above with clinical diagnosis of tinea corporis and tinea cruris confirmed by potassium hydroxide (KOH) test. We excluded pregnant and lactating women and patients with preexisting renal, hepatic diseases, cardiac failure, or history of hypersensitivity to the study medications from our study. Patients receiving treatment with systemic immunosuppressive drugs during the study or in the past 2 weeks before enrolling in the study were also excluded from the study. The patients were randomly allocated to receive a daily dose of terbinafine 500 mg daily for 4 weeks (Group I) or 200 mg of itraconazole for 4 weeks daily (Group II).

Mycological and clinical assessments

Patients were followed up after 2 weeks and 4 weeks of the study period. At each visit, clinical response was noted including pruritus, erythema, and scaling. These were rated as clinical score 0–3, 0 – absent, 1 – mild, 2 – moderate, and 3 – severe.

Global clinical evaluation was done, and the response was noted accordingly as healed, marked improvement, considerable residual lesions (>50%), no change, or worse. KOH examination was done at the time of enrolling the patient and at the end of the 4th week. Liver function tests were done at the start of therapy and after 2 weeks of therapy. Monitoring of signs and symptoms for any adverse cardiac event was done at each visit, especially for high-risk patients (diabetics and hypertensives) on itraconazole. Patients were considered cured when there was an absence of scaling, erythema, and pruritus, and KOH was also negative. Postinflammatory pigmentary changes were not taken into consideration.

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee, and informed consent was taken from all patients before recruiting.

Statistical analysis

Association among dichotomous variables was tested with Fisher's exact test and continuous variables with a Student's test. Percentage change was compared using Mann–Whitney U-test and Wilcoxon test. All analysis was done SPSS version 21.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

Results

A total of 326 patients were randomly assigned treatment and included in the study. Because of deranged baseline liver function tests, 6 patients were excluded from the study. Hence, a total of 320 patients were enrolled in the final study. Half of the patients (160) were started on terbinafine 500 mg once a day, while the other half were given oral itraconazole 200 mg once a day.

Table 1 shows the demographic profile of patients as well as diagnosis in both the groups. The average age of the patients was 34.97 and 34.78 years, respectively, in Group I and Group II. Group I had 104 males (65%) and 56 females (35%), while Group II had 107 males (66.8%) and 53 females (33.2%). Majority of the patients were diagnosed with both tinea corporis and tinea cruris in the study groups – 129 patients (80.6%) in Group I and 135 patients (84.4%) in Group II.

Table 1.

Demographic profile and diagnosis in both the groups

| Parameters | Group 1 Terbinafine (n=160) |

Group 2 Itraconazole (n=160) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (mean±SD) | 34.97±14.123 | 34.78±13.039 |

| Gender, n (%) | ||

| Male | 103 (32.3) | 107 (33.5) |

| Female | 56 (17.6) | 53 (16.6) |

| Diagnosis | ||

| Tinea cruris | 11 (3.4) | 7 (2.2) |

| Tinea corporis | 10 (3.1) | 5 (1.6) |

| Tinea cruris et corporis | 129 (40.3) | 135 (42.2) |

| Tinea cruris et corporis with faciei | 10 (3.1) | 13 (4.1) |

No statistically significant difference in the above parameters. SD=Standard deviation

At the end of 4 weeks, there was a statistically significant improvement in erythema, scaling, and pruritus scores in Group I as well as in Group II [Table 2]. The significant improvement started from 0 to 2 weeks and then persisted from 2 to 4 weeks in both the groups. The absolute score of erythema, scaling, and pruritus was significantly different at baseline when both the groups were compared. Hence, we calculated the percentage change in the scores of all three parameters.

Table 2.

Clinical parameters in Group I (n=160) and Group II (n=160)

| Scores | Group 1 |

Group II |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| At baseline | After 2 weeks | After 4 weeks | At baseline | After 2 weeks | After 4 weeks | |

| Scaling | 1.21±0.47 | 1.05±0.55 | 0.55±0.93 | 0.90±0.49 | 1.04±0.44 | 0.16±0.48 |

| P | <0.05 | <0.001 | <0.05 | <0.001 | ||

| Pruritus | 2.14±0.60 | 1.49±0.74 | 0.78±1.22 | 1.77±0.66 | 1.18±0.62 | 0.24±0.78 |

| P | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Erythema | 1.55±0.61 | 1.08±0.73 | 0.58±1.03 | 1.18±0.63 | 0.66±0.66 | 0.19±0.65 |

| P | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

Values represent mean±SD. SD=Standard deviation

The percentage improvement in erythema, scaling, and pruritus scores was significantly more in both the groups from 0 to 4 weeks [Table 3]. The percentage change was significantly more in pruritus from 2 to 4 weeks only in Group I. In Group II, the percentage change in pruritus and scaling was significantly different from 0 to 2 weeks and 2–4 weeks. On comparing the groups, there was a significant improvement in scaling score from 0 to 2 weeks and from 2 to 4 weeks but not from 0 to 4 weeks. There was a significant improvement in pruritus from 2 to 4 weeks only. There was no statistically significant percentage change in erythema scores.

Table 3.

Percentage change in clinical parameters in both the groups

| Parameters | Mean±SD (%) |

P values between groups | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 (n=160) | Group 2 (n=160) | ||

| Pruritus | |||

| Baseline to 2 weeks | 21.7±30.4 | 19.8±24.8 | 0.637 |

| 2 weeks to 4 weeks | 24.0±31.3 | 31.3±23.3* | 0.028 |

| Baseline to 4 weeks | 45.6±44.5*,# | 51.0±29.4*,# | 0.861 |

| Scaling | |||

| Baseline to 2 weeks | 5.4±23.3 | −4.8±21.4 | <0.001 |

| 2 weeks to 4 weeks | 16.7±28.0* | 29.6±19.1* | <0.001 |

| Baseline to 4 weeks | 22.1±35.0*,# | 24.8±21.2*,# | 0.698 |

| Erythema | |||

| Baseline to 2 weeks | 15.4±31.0 | 17.3±27.5 | 0.449 |

| 2 weeks to 4 weeks | 16.9±22.7 | 15.6±18.3 | 0.386 |

| Baseline to 4 weeks | 32.3±38.6*,# | 32.9±25.9*,# | 0.372 |

Within-group comparison *P<0.05 as compared to baseline to 2 weeks, #P<0.05 as compared to 2-4 weeks. SD=Standard deviation

Mycological cure was achieved in 147 (91.8%) in Group II and 119 (74.3%) in Group I at the end of 4 weeks. Mild adverse effects such as gastrointestinal upset, headache, and taste disturbances were observed; however, none were severe enough to warrant the discontinuation of treatment. There was no significant difference in adverse effects between both the groups.

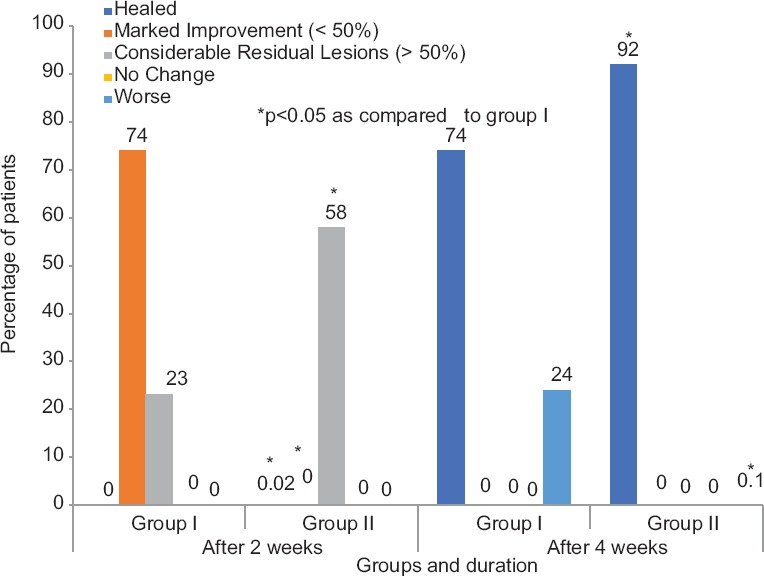

At the end of 4 weeks, the global clinical response was significantly better in the itraconazole group as compared to the terbinafine group. The clinical global evaluation staging shows [Figure 1] more patients in the healed category in Group II as compared to Group I (46% vs. 37%). Only a few patients worsened in itraconazole group (Group I) as compared to the terbinafine group (Group II) (4.1% vs. 12.2%). Tolerability and compliance to the drug were similar in both the groups.

Figure 1.

Global clinical evaluation between Group I (n= 160) and Group II (n= 160)

Discussion

Widespread resistance to conventional doses of antifungals with increasing clinical failure rates warrants the search for an effective first-line antifungal drug that brings about rapid clinical and mycological cure in tinea corporis and tinea cruris.

Terbinafine resistance when given in the standard doses (250 mg once a day for 2 weeks) is being increasingly seen with partial or no response to treatment.[5] Antifungal resistance is due to a decrease in effective drug concentration because of extensive accumulation of terbinafine in the skin and adipose tissue.[13] Hence, higher concentration of terbinafine 500 mg/day has seen found to be more effective.[8,14,15]

Itraconazole is a triazole antifungal drug which is also increasingly being used as a first-line drug for tinea corporis and tinea cruris, but it is being given for longer periods as compared to before.[11,12]

The most common side effects with terbinafine are gastric upset, headache, altered taste, altered liver function tests and rash; rarely, it can cause blood dyscrasias and hepatitis.[6] Itraconazole can cause gastric upset, headache, taste alteration, and jaundice, and rarely, it can cause hypokalemia, torsades de pointes, and heart failure.[12] However, in our study, minor side effects such as nausea, bloating sensation, headache, and taste disturbances were seen.

The results of our study suggest that itraconazole is a better drug than terbinafine in efficacy and mycological cure. This is similar to an earlier study in patients of tinea cruris who also found itraconazole to have higher cure rates as compared to terbinafine.[9] Although studies on toenail onychomycosis have found terbinafine to be more effective than itraconazole,[16] we found the reverse to be true for tinea corporis and tinea cruris. Both the drugs have a similar pharmacokinetic profile. The treatment costs per patient with terbinafine are lower than those with itraconazole for the same duration of therapy. However, when taken into account the response rates and total duration of therapy required to have complete cure, itraconazole fares slightly better over terbinafine, thereby mitigating the cost difference. Safety profile was similar in both the groups.

Conclusion

Itraconazole has higher clinical and mycological cure rates as compared to terbinafine. Although the cost of terbinafine is lower, the failure rate is higher and the duration of treatment required is longer. Therefore, itraconazole seems to be superior to terbinafine in the treatment of tinea corporis and tinea cruris.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The authors wish to thank Ms. Himani Khattar, Biostatistician, Christian Medical College, Ludhiana, in helping with analysis.

References

- 1.Havlickova B, Czaika VA, Friedrich M. Epidemiological trends in skin mycoses worldwide. Mycoses. 2008;51(Suppl 4):2–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2008.01606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh S, Beena PM. Comparative study of different microscopic techniques and culture media for the isolation of dermatophytes. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2003;21:21–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Newland JG, Abdel-Rahman SM. Update on terbinafine with a focus on dermatophytoses. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2009;2:49–63. doi: 10.2147/ccid.s3690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McClellan KJ, Wiseman LR, Markham A. Terbinafine. An update of its use in superficial mycoses. Drugs. 1999;58:179–202. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199958010-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Osborne CS, Leitner I, Favre B, Ryder NS. Amino acid substitution in Trichophyton rubrum squalene epoxidase associated with resistance to terbinafine. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:2840–4. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.7.2840-2844.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Majid I, Sheikh G, Kanth F, Hakak R. Relapse after oral terbinafine therapy in dermatophytosis: A Clinical and mycological study. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:529–33. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.190120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sanglard D. Emerging threats in antifungal-resistant fungal pathogens. Front Med (Lausanne) 2016;3:11. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2016.00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Babu PR, Pravin AJ, Deshmukh G, Dhoot D, Samant A, Kotak B, et al. Efficacy and safety of terbinafine 500 mg once daily in patients with dermatophytosis. Indian J Dermatol. 2017;62:395–9. doi: 10.4103/ijd.IJD_191_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shakya NB, Jha MS, Dangol A, Shakya S, Shah A. Efficacy of itraconazole versus terbinafine for the treatment of tinea cruris. Med J Shree Birendra Hosp. 2012;11:24–6. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chow KW, Ting HC, Yap YP, Yee KC, Purushotaman A, Subramanian S, et al. Short treatment schedules of itraconazole in dermatophytosis. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:446–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.1998.00497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ardeshna KP, Rohatgi S, Jerajani HR. Successful treatment of recurrent dermatophytosis with isotretinoin and itraconazole. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2016;82:579–82. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.183632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donckar PD, Pande S, Richarz U, Gerodia N. Itraconazole: What clinicians should know Indian. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;3:4–10. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hosseini-Yeganeh M, McLachlan AJ. Physiologically based pharmacokinetic model for terbinafine in rats and humans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:2219–28. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.7.2219-2228.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cole GW, Stricklin G. A comparison of a new oral antifungal, terbinafine, with griseofulvin as therapy for tinea corporis. Arch Dermatol. 1989;125:1537–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hay RJ, Logan RA, Moore MK, Midgely G, Clayton YM. A comparative study of terbinafine versus griseofulvin in 'dry-type' dermatophyte infections. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:243–6. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(91)70035-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sigurgeirsson B, Olafsson JH, Steinsson JB, Paul C, Billstein S, Evans EG, et al. Long-term effectiveness of treatment with terbinafine vs. itraconazole in onychomycosis: A 5-year blinded prospective follow-up study. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:353–7. doi: 10.1001/archderm.138.3.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]