Abstract

Mutations in GUCY2D, the gene encoding retinal guanylate cyclase-1 (retGC1), are the leading cause of autosomal dominant cone–rod dystrophy (CORD6). Significant progress toward clinical application of gene replacement therapy for Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA) due to recessive mutations in GUCY2D (LCA1) has been made, but a different approach is needed to treat CORD6 where gain of function mutations cause dysfunction and dystrophy. The CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing system efficiently disrupts genes at desired loci, enabling complete gene knockout or homology directed repair. Here, adeno-associated virus (AAV)-delivered CRISPR/Cas9 was used specifically to edit/disrupt this gene's early coding sequence in mouse and macaque photoreceptors in vivo, thereby knocking out retGC1 expression and demonstrably altering retinal function and structure. Neither preexisting nor induced Cas9-specific T-cell responses resulted in ocular inflammation in macaques, nor did it limit GUCY2D editing. The results show, for the first time, the ability to perform somatic gene editing in primates using AAV-CRISPR/Cas9 and demonstrate the viability this approach for treating inherited retinal diseases in general and CORD6 in particular.

Keywords: CRISPR/Cas9, GUCY2D, cone rod dystrophy, retina, gene editing, AAV

Introduction

Mutations in GUCY2D are a leading cause of a rare, autosomal dominant cone–rod dystrophy (CORD6; OMIM #601777), accounting for ∼35% of cases.1,2 CORD6 patients present with a loss of visual acuity, abnormal color vision, photophobia, visual field loss, and macular atrophy within the first decade. In severe cases, rod degeneration and loss of peripheral visual field follow loss of cones. Electroretinography reveals cone dysfunction with variable levels of rod involvement.3,4 There are no therapies currently available for treating CORD6.

GUCY2D (or Gucy2e in mice) encodes retGC1, a protein expressed in photoreceptor (PR) outer segments.5,6 Upon light stimulation, cGMP hydrolysis by cGMP phosphodiesterase (PDE6) leads to closure of cGMP-gated channels, a reduction in intracellular Ca2+, and hyperpolarization of PRs. This reduction in Ca2+ levels is sensed by guanylate cyclase activating protein-1 (GCAP1),7 which responds by activating retGC1 in its Ca2+-free form. RetGC1 then produces cGMP within PR outer segments, thereby speeding up the recovery phase of phototransduction. This increase in cGMP reopens cGMP-gated channels, leading to increased intracellular Ca2+ and the subsequent feedback deactivation of retGC1 via Ca2+-liganded GCAP1. Thus, the physiological link between GC1, GCAP1, and intracellular Ca2+ affects the polarization state of the PR.8,9 Recessive mutations in GUCY2D lead to Leber congenital amaurosis type I (LCA1), one of if not the most common form of LCA.10 LCA1-causing mutations can be found throughout the gene,11 and result in the absence of functional retGC1. Dominantly inherited CORD6-causing mutations on the other hand are clustered at or adjacent to residue R838 in the dimerization domain of retGC1.12,13 They increase the cyclase's affinity for Ca2+-free GCAP1 and therefore require higher concentrations of Ca2+ for its suppression.14–16 PR cell death in CORD6 is due to overproduction of cGMP by the mutant cyclase and increased intracellular Ca2+ levels.17 While the precise mechanism by which apoptosis occurs has yet to be established, it is likely that increased Ca2+ levels overload the Ca2+ uptake capacity of mitochondria, promoting caspase activation and ultimately PR apoptosis.18

Significant progress has been made toward clinical application of gene replacement for LCA1, with a Phase I/II clinical trial anticipated in the near future.19–22 However, a different approach is needed to treat an autosomal dominant disease such as CORD6, where disruption of the mutant GUCY2D allele responsible for dysfunction must be achieved while maintaining expression of normal retGC1. Given the demonstrated ability to deliver therapeutic GUCY2D cDNA to PRs via AAV, an attractive treatment approach for CORD6 is to ablate expression of both endogenous alleles and complement back with a “hardened” wtGUCY2D, which is resistant to gene editing. The clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/Cas9 gene editing system has emerged as a precision tool for targeted gene knockout.23,24 The system utilizes a guide RNA (gRNA) that directs the Cas9 endonuclease to specific sites in the genome proximal to a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM),25 causing a double-strand break (DSB). Host cell machinery efficiently repairs the DNA damage via non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and, during this process, introduces insertions or deletions (indels) at the target site. Gene disruption can thus be achieved if the target site is within the coding sequence and indels lead to frameshifts or disruption of a region of the gene product critical for function.

Therapeutic gene editing in vivo is being actively investigated, with proof of concept demonstrated for metabolic, neuromuscular, and retinal disease.26–31 The retina is a particularly attractive target for CRISPR/Cas9-based therapies for several reasons. First, efficient vectors for retinal gene delivery such as adeno-associated virus (AAV) have been identified and confirmed to be safe and efficacious in clinical trials.32 Second, transgene expression can be restricted to the retinal cell or tissue of interest. This is due both to the self-contained nature of the eye, which limits biodistribution of intraocularly delivered vectors, and the availability of tissue-specific promoters that can restrict transgene expression (i.e., Cas9) to the target cell.33–37 Some progress has already been made to establish feasibility of using CRISPR/Cas9 to treat inherited retinal disease.29,30,38,39 To date, however, CRISPR/Cas9 has not been shown capable of targeting and disrupting a disease-causing gene in primate PRs. Here, evidence is shown for selective and efficient somatic knock out of the gene coding for retinal guanylate cyclase 1 (Gucy2e/GUCY2D) in the mouse and macaque using AAV-delivered CRISPR/Cas9 reagents. The results demonstrate the feasibility of performing gene editing in primate PRs, and establish a framework for the development of AAV-CRISPR/Cas9-based treatments for inherited retinal diseases in general and CORD6 in particular.

Methods

gRNA design

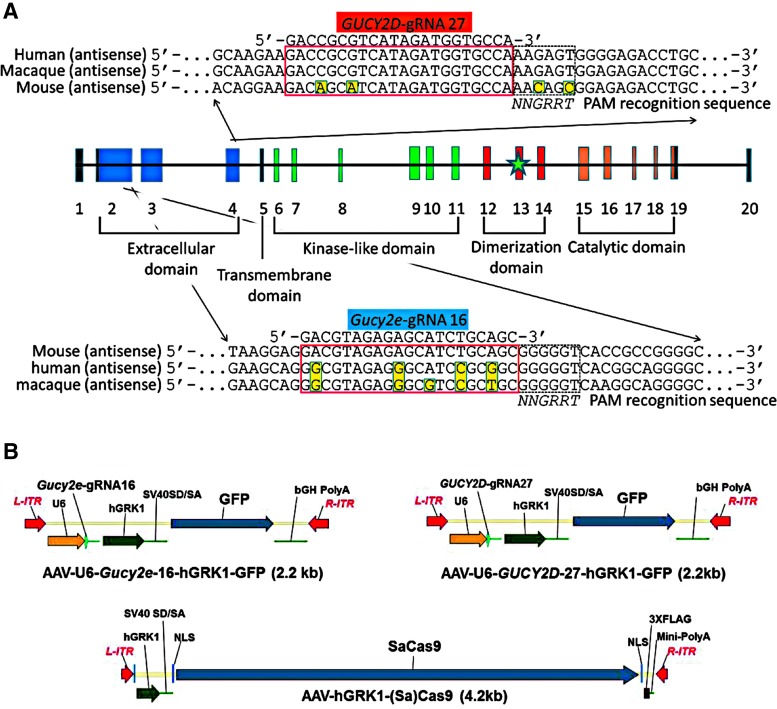

gRNAs were designed to target the early coding sequence in either Gucy2e or GUCY2D, with the goal of ablating expression of retGC1 protein (Fig. 1A). Guide design for Staphylococcus aureus gRNAs was carried out using Godot, a custom gRNA design software based on the public tool Cas-OFFinder.40 GUCY2D guides were selected to target both the macaque and human GUCY2D gene. Godot scores guides after calculating their genome-wide off-target propensity. Genome builds used were MacFas5 for macaque, hg38 for human, and mm10 for mouse. Guides were prioritized based on orthogonality in the target species genome, with strong preference given for gRNAs starting with a 5′ G and a PAM sequence of NNGRRT.

Figure 1.

Staphylococcus aureus (Sa)Cas9 guide RNAs (gRNAs) targeting macaque (Macaca fascicularis)/human GUCY2D and mouse Gucy2e loci were selected to target early coding sequence within the extracellular domain of the genes. Protospacer and protospacer adjacent motif recognition sequences are shown in an alignment of the corresponding mouse, human, and macaque sequence. Green star represents location of R838S mutation (A). AAV vector plasmids containing Gucy2e gRNA16, GUCY2D gRNA27, and SaCa9 are shown (B).

gRNA efficacy testing

The activity of gRNAs was tested by transfecting a plasmid encoding SaCas9, driven by the CMV promoter, and linear DNA expressing gRNAs, driven by U6 promoter, into cells. NIH 3T3 cells (ATCC) were used to test mouse gRNAs, and HEK293 cells (ATCC) were used to test macaque/human gRNAs. NIH 3T3 cells and HEK293 cells were maintained in Gibco Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) + Glutamax supplemented with 1% penicillin streptomycin and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). HEK293 cells were transfected with 750 ng Cas9 plasmid and 250 ng linear gRNA-expressing DNA using TransIT-293 Transfection Reagent (Mirus Bio). NIH 3T3 cells were transfected by Lonza nucleofection with 750 ng Cas9 plasmid and 250 ng linear gRNA-expressing DNA in SG nucleofection solution, using pulse code EN-158. Cells were harvested 3 days post transfection, and genomic DNA was isolated using the Agencourt DNAdvance kit (Beckman Coulter) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Editing rates were determined by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplifying the region surrounding the gRNA target sites and performing a standard T7 Endonuclease I assay (New England Biolabs), which was analyzed on a QIAxcel analyzer (Qiagen).

Experimental animals

To avoid confusion about nomenclature across species, genes and their encoded proteins are described herein. Retinal guanylate cyclase-1 (retGC1) and retinal guanylate cyclase-2 (retGC2) are encoded in mice by Gucy2e and Gucy2f, respectively. Gucy2f is located on the X chromosome. In macaques, retGC1 is encoded by GUCY2D. C57Bl/6J (wild type [WT]) and Gucy2e knockout (GC1−/−) mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories.41 Gucy2e/Gucy2f double knockout (GCdko) mice were generously provided by Dr. Wolfgang Baehr (University of Utah).9 To generate a line containing a single allele of Gucy2e and a full knockout of Gucy2f (GC1+/−:GC2−/−),first GCdko mice were crossed with WT mice to create experimental GC1+/−:GC2− males and GC1+/−:GC2+/− double-heterozygote females. To generate experimental females (GC1+/−:GC2−/−), experimental males were back-crossed with GCdko females. Experimental females and males were crossed to produce GC1+/+:GC2−/(−) breeders. These breeders were used to produce 100% experimental offspring when bred with GCdko. Genotyping primers to identify the presence/absence of Gucy2e (retGC1) included “GC1F4” (forward primer in WT intron 4), “GC1R4” (reverse primer in WT intron 5), and “NeoF4” (forward primer in neo cassette), as previously published.41 For Gucy2f (retGC2), “Pla2” (forward primer in neomycin cassette), “GC2mt-R2” (reverse primer), “GCtowt1” (WT), and “GCtoda6” (WT) were used, as previously described.9

All mice were bred and maintained at the University of Florida Health Science Center Animal Care Services Facility under a 12 h/12 h light/dark cycle. Food and water were available ad libitum. All experiments were approved by the University of Florida's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and were conducted in accordance with the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research and with National Institutes of Health regulations.

Three adult male macaques (Macaca fascicularis) were used in this study (SA65E, 7 years 10 months; GR114QB, 6 years 1 month; and JR40D, 6 years 9 months). All procedures performed on the macaques were approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at the University of Alabama at Birmingham and performed in accordance with the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology Statement for the use of animals in ophthalmic and vision research.

Construction of AAV vectors

Vector plasmids containing flanking AAV2 inverted terminal repeats (ITRs) were constructed to include the human RNA polymerase III U6 promoter (U6) followed gRNA sequences, then the 292 bp human rhodopsin kinase promoter (hGRK1) and SV40 splice donor splice acceptor sites (SV40SD/SA), followed green fluorescent protein (GFP) and finally bovine growth hormone poly-adenylation signal (bGH-polyA) or hGRK1, SV40SD/SA, followed by S. aureus Cas9 (Cas9)42,43 containing dual nuclear localization signals (NLS) and a carboxy-terminus triple FLAG tag (3XFLAG) and a synthetic mini poly-adenylation signal (Mini-PolyA).43 Plasmids pMC12 (pTR-U6-mGucy2e-gRNA16-hGRK1-GFP), pKJS115 (pTR-U6-nhpGUCY2D-gRNA27-hGRK1-GFP), and pAF251 (pTR-hGRK1-Cas9) were manufactured to large scale and purified by solid phase, anion exchange chromatography using a commercially available kit (Qiagen). Subsequently, vector plasmids along with AAV5 helper plasmid (pXYZ5), containing AAV2 rep, AAV5 cap, and required adenovirus helper genes, were co-transfected into HEK293 cells according to previously published methods.44 Cells were harvested 72 h post transfection. Virus was purified by iodixanol discontinuous density gradient ultracentrifugation followed by ion exchange chromatography and buffer exchanged into a Balanced Salt Solution (BSS) supplemented with 0.014% Tween 20. The virus was titered for vector genomes (vg) by dot-blot and evaluated by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis to confirm the high level purity of capsid proteins VP1, VP2, and VP3 (data not shown). Each undiluted vector preparation was tested for the presence of endotoxin, with all registering at <5 Eu/mL. Additionally, AAV5-Gucy2e-gRNA16-hGRK1-GFP and AAV5-GUCY2D-gRNA27-hGRK1-GFP vector particles were also visualized by electron microscopy to confirm the presence of mostly “full” particles (Supplementary Fig. S1). Vectors were diluted with BSS-Tween to the desired concentration for experiments.

Subretinal injections

One microliter of was delivered to the subretinal space of WT or GC1+/−:GC2−/− mice under a Leica M80 Stereomicroscope according to previously published methods.45 To compare promoters driving Cas9, single vectors were injected into WT mice at either high (3 × 1012 vg/mL) or low (3 × 1011 vg/mL) concentrations. To evaluate gene editing in WT or GC1+/−:GC2−/− mouse strains, two vectors were co-delivered, each at 3 × 1012 vg/mL, for a total concentration of 6 × 1012 vg/mL. A subset of GC1+/−:GC2−/− mice received higher doses, with vectors co-delivered at 3 × 1013 vg/mL, for a total concentration of 6 × 1013 vg/mL. A summary of mouse injections is provided in Table 1. Injection blebs were imaged immediately following injection, and further analysis was carried out only on animals that received comparable successful injections (≥60% retinal detachment and minimal complications). It is well established that for AAV5, the area of vector transduction corresponds to at least the area of retinal detachment.36

Table 1.

A comprehensive summary of mouse experiments

| Mouse strain | Dosing regimen | Outcome measures | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment age | Eye | Treatment | Vector [ ] (vg/mL) | Vector dose (vg/eye) | Fundoscopy | OCT | ERG | FACS | Cryo-IHC | Western blotting | RT-PCR | |

| WT | 2 months | OD (n = 9) | AAV5-hGRK1-Cas9 | 3 × 1012 | 3 × 109 | 6 weeks p.i. | 6 weeks p.i. | n/a | 7 weeks p.i. | n/a | 7 weeks p.i. | 7 weeks p.i. |

| WT | 2 months | OD (n = 9) | AAV5-hGRK1-Cas9 | 3 × 1011 | 3 × 108 | |||||||

| WT | 2 months | OD (n = 10) | AAV5-EFS-Cas9 | 3 × 1012 | 3 × 109 | |||||||

| WT | 2 months | OD (n = 10) | AAV5-EFS-Cas9 | 3 × 1011 | 3 × 108 | |||||||

| WT | 2 months | OD (n = 10) | AAV5-dCMV-Cas9 | 3 × 1012 | 3 × 109 | |||||||

| WT | 2 months | OD (n = 10) | AAV5-dCMV-Cas9 | 3 × 1011 | 3 × 108 | |||||||

| WT | 3 months | OD (n = 28) | AAV5-hGRK1-Cas9 + AAV5-GUCY2D gRNA-hGRK1-GFP | 3 × 1012 each, 6 × 1012 total | 3 × 109 each, 6 × 109 total | 4 weeks p.i. (n = 4) 6 weeks p.i. (n = 28) |

4 weeks p.i. (n = 10) 6 weeks p.i. (n = 28) |

6 weeks p.i. (n = 28) | 7 weeks p.i. (n = 9) | 7 weeks p.i. (n = 5) | 7 weeks p.i. (n = 4) | 7 weeks p.i. (n = 3) |

| OS (n = 28) | AAV5-hGRK1-Cas9 + AAV5-Gucy2e gRNA-hGRK1-GFP | 3 × 1012 each, 6 × 1012 total | 3 × 109 each, 6 × 109 total | 4 weeks p.i. (n = 4) 6 weeks p.i. (n = 28) |

4 weeks p.i. (n = 10) 6 weeks p.i. (n = 28) |

6 weeks p.i. (n = 28) | 7 weeks p.i. (n = 11) | 7 weeks p.i. (n = 5) | 7 weeks p.i. (n = 4) | 7 weeks p.i. (n = 3) | ||

| WT | 2 months | Both (n = 10) | BSS/Tween alone | n/a | n/a | n/a | 6 weeks p.i. (n = 6) | 6 weeks p.i (n = 6) | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| GC1+/–:GC2−/− | 1–2 months | OD (n = 18) | AAV5-hGRK1-Cas9 + AAV5-Gucy2e gRNA-hGRK1-GFP | 3 × 1012 each, 6 × 1012 total | 3 × 109 each, 6 × 109 total | 6 weeks p.i. (n = 18) 10 weeks p.i. (n = 10) 20 weeks p.i. (n = 10) |

6 weeks p.i. (n = 10) 10 weeks p.i. (n = 10) 20 weeks p.i (n = 10) |

6 weeks p.i. (n = 10) 10 weeks p.i. (n = 10) 20 weeks p.i (n = 10) |

n/a | 6 weeks p.i. (n = 1) | 24 weeks p.i. (n = 3) | n/a |

| OS (n = 18) | AAV5-hGRK1-Cas9 + AAV5-GUCY2D gRNA-hGRK1-GFP | 3 × 1012 each, 6 × 1012 total | 3 × 109 each, 6 × 109 total | 6 weeks p.i. (n = 18) 10 weeks p.i. (n = 10) 20 weeks p.i. (n = 10) |

6 weeks p.i. (n = 10) 10 weeks p.i. (n = 10) 20 weeks p.i (n = 10) |

6 weeks p.i. (n = 10) 10 weeks p.i. (n = 10) 20 weeks p.i (n = 10) |

n/a | 6 weeks p.i. (n = 1) | 24 weeks p.i. (n = 4) | n/a | ||

| GC1+/–:GC2−/− | 1 month | OD (n = 14) | AAV5-hGRK1-Cas9 + AAV5-Gucy2e gRNA-hGRK1-GFP | 3 × 1012 each, 6 × 1012 total | 3 × 109 each, 6 × 109 total | 6 weeks p.i. (n = 14) | 6 weeks p.i. (n = 14) | 6 weeks p.i. (n = 14) | 8 weeks p.i. (n = 10) | n/a | n/a | 8 weeks p.i. (n = 10) |

| OS (n = 14) | AAV5-hGRK1-Cas9 + AAV5-GUCY2D gRNA-hGRK1-GFP | 3 × 1012 each, 6 × 1012 total | 3 × 109 each, 6 × 109 total | 6 weeks p.i. (n = 14) | 6 weeks p.i. (n = 14) | 6 weeks p.i. (n = 14) | 8 weeks p.i. (n = 10) | n/a | n/a | 8 weeks p.i. (n = 10) | ||

| GC1+/–:GC2−/− | 1 month | OD (n = 12) | AAV5-hGRK1-Cas9 + AAV5-Gucy2e gRNA-hGRK1-GFP | 3 × 1013 each, 6 × 1013 total | 3 × 1010 each, 6 × 1010 total | 4 weeks p.i. (n = 12) | 7 weeks p.i. (n = 8) 20 weeks p.i. (n = 3) |

7 weeks p.i. (n = 10) 20 weeks p.i. (n = 6) |

8 weeks p.i. (n = 2) | 8 weeks (n = 2) | n/a | n/a |

| OS (n = 12) | AAV5-GUCY2D gRNA-hGRK1-GFP | 3 × 1013 each, 6 × 1013 total | 3 × 1010 each, 6 × 1010 total | 4 weeks p.i. (n = 12) | 7 weeks p.i. (n = 7) 20 weeks p.i. (n = 5) |

7 weeks p.i. (n = 10) 20 weeks p.i. (n = 6) |

8 weeks p.i. (n = 2) | 8 weeks (n = 2) | n/a | n/a | ||

| GC1+/–:GC2−/− | 1 month | Both (n = 10) | BSS/Tween alone | n/a | n/a | n/a | 6 weeks p.i. (n = 5) 20 weeks p.i. (n = 5) |

6 weeks p.i. (n = 5) 20 weeks p.i. (n = 5) |

n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

OCT, optical coherence tomography; ERG, electroretinogram; FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting; IHC, immunohistochemistry; RT-PCR, reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction; p.i., post injection; WT, wild type; BSS, Balanced Salt Solution; GFP, green fluorescent protein.

Subretinal injections in macaque eyes were performed according to previously published methods with minor modifications.36 Three macaques received subretinal injections of AAV5-U6-GUCY2D-gRNA27-hGRK1-GFP + AAV5-hGRK1-Cas9 (right eyes) and AAV5-Gucy2e-gRNA16-hGRK1-GFP + AAV5-hGRK1-Cas9 (left eyes), except for one animal whose left eye was injected with AAV5-hGRK1-GFP and used for other purposes. Three distinct subretinal blebs were created in each eye to accommodate multiple outcome measures, including cryo-immunohistochemistry (IHC), Western blot, and indel analysis (Table 2). Blebs were directed to the macula (M), inferior nasal (IN), and inferior temporal (IT) retina in each eye. The ability to create multiple, distinct blebs surgically was previously demonstrated in nonhuman primates (NHPs) for a similar purpose.46 Subjects received dexamethasone (0.25 mg/kg intramuscularly [i.m.]) the day before and on the day of surgery. An Accurus 800CS surgical system with Xenon light source, Total Plus 25 gauge Vitrectomy Pak (Alcon, Inc.) and Zeiss VISU 200 ophthalmic surgical microscope equipped with digital video (Endure Medical) were used for the surgery. A standard 25-gauge three-port pars plana vitrectomy was performed, with an inferior infusion cannula maintaining a pressure of 20–30 mmHg with BSS Plus (Alcon, Inc.). Subsequently, the superior-temporal sclerotomy was enlarged with a 20-gauge MVR blade for the injection cannula. A 39-gauge injection cannula with 20-gauge shaft (Synergetics) was used to deliver the vector into the subretinal space of subjects SA65E and GR114QB. A 39-gauge injection cannula (Katalyst) attached to a 1 mL disposable barrel injector (DV1600 Katalyst Injector System) was used to deliver the vector into the subretinal space of subject JR40D.

Table 2.

A comprehensive summary of macaque experiment

| Animal | Dosing regimen | Bleb location | Bleb volume | Vector [ ] (vg/mL) | Vector dose (vg/eye) | Bleb location | Bleb volume | Vector [ ] (vg/mL) | Vector dose (vg/eye) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OD | OS | OD | OS | |||||||

| SA65E | AAV5-hGRK1-Cas9 + AAV5-GUCY2D gRNA-hGRK1-GFP | AAV5-hGRK1-GFP | IN | 100 μL | 6 × 10e12 | 6 × 10e11 | IN | 80 μL | 3 × 10e12 | 2.4 × 10e11 |

| IT | 80 μL | 6 × 10e12 | 4.8 × 10e11 | IT | 40 μL | 3 × 10e12 | 1.2 × 10e11 | |||

| Macula | 50 μL | 6 × 10e12 | 3 × 10e11 | Macula | 180 μL | 3 × 10e12 | 5.4 × 10e11 | |||

| GR114QB | AAV5-hGRK1-Cas9 + AAV5-GUCY2D gRNA-hGRK1-GFP | AAV5-hGRK1-Cas9 + AAV5-Gucy2e gRNA-hGRK1-GFP | IN | 60 μL | 6 × 10e12 | 3.6 × 10e11 | IN | 100 μL | 6 × 10e12 | 6 × 10e11 |

| IT | 80 μL | 6 × 10e12 | 4.8 × 10e11 | IT | 100 μL | 6 × 10e12 | 6 × 10e11 | |||

| Macula | 110 μL | 6 × 10e12 | 6.6 × 10e11 | Macula | 120 μL | 6 × 10e12 | 7.2 × 10e11 | |||

| JR40D | AAV5-hGRK1-Cas9 + AAV5-GUCY2D gRNA-hGRK1-GFP | AAV5-hGRK1-Cas9 + AAV5-Gucy2e gRNA-hGRK1-GFP | IN | 50 μL | 6 × 10e12 | 3 × 10e11 | IN | 80 μL | 6 × 10e12 | 4.8 × 10e11 |

| IT | 100 μL | 6 × 10e12 | 6 × 10e11 | IT | 60 μL | 6 × 10e12 | 3.6 × 10e11 | |||

| Macula | 50 μL | 6 × 10e12 | 3 × 10e11 | Macula | 100 μL | 6 × 10e12 | 6 × 10e11 | |||

IN, inferior nasal; IT, inferior temporal.

All blebs in subject SA65E were created without incident. In subject GR114QB, a small air bubble was inadvertently delivered to the IT bleb of the OD eye, but no subsequent damage was observed. All other blebs in this subject were created without incident. Slight retinal damage occurred in the IN and IT blebs of subject JR40D's OS eye. All other blebs in this subject were created without incident. Following subretinal injections, sclerotomy sites and conjunctiva were sutured closed using 9.0 Vicryl, and subconjunctival cefazolin and dexamethasone were administered. To prevent corneal drying during surgical recovery, triple antibiotic ophthalmic ointment was applied to both eyes. Upon recovery, the subject received subcutaneous sustained release buprenorphine (0.2 mg/kg) and meloxicam (0.6 mg/kg) and cefazolin (25 mg/kg i.m.). In all but one eye, recovery was uneventful; the corneas of the treated eyes remained clear, with only mild conjunctival redness, which resolved within a day after surgery. The OS eye of subject JR40D showed slight vitreal haziness 4 days postoperatively. The animal was treated with dexamethasone (0.25 mg/kg i.m.) for 1 day followed by a 4-day taper, and upon exam, the eye appeared normal 8 days postoperatively.

In-life imaging

Mice were sedated, and expression of GFP was documented using a Micron III funduscope (Phoenix Research Laboratories) with a green fluorescent filter. GFP expression was similarly documented at 4, 6, 10, or 20 weeks post subretinal injection in all mice that received AAV5-GUCY2D-gRNA27-hGRK1-GFP or AAV5-Gucy2e-gRNA16-hGRK1-GFP vectors. Exposure settings were identical for all mice. Averaging of GFP pixel intensity was performed across select cohorts by loading images in sequence and using the average intensity Z-projection in ImageJ.

Outer nuclear layer (ONL) thickness in WT and GC1+/−:GC2−/− mice was quantified by optical coherence tomography (OCT; Bioptigen, Inc.) between 4 and 20 weeks post injection according to previously published methods.47 Briefly, after sedation and dilation, three lateral images (nasal to temporal) were collected, starting 3 mm above the meridian crossing through the center of the optic nerve head (ONH), at the ONH meridian, and 3 mm below the ONH meridian. A corresponding box centered on the ONH with eight measurement points separated by 3 mm from each other was created. ONL thickness in mice injected with AAV-hGRK1-Cas9 plus either AAV5-Gucy2e-gRNA16-hGRK1-GFP or control AAV5-GUCY2D-gRNA27-hGRK1-GFP vector were compared. Statistical significance was determined by a paired t-test, with p-values of <0.05 considered significant.

All macaques were sedated, situated, and imaged using a Spectralis™ HRA + OCT (Heidelberg Engineering, Inc.) scanning laser ophthalmoscope, as previously described. Images were obtained with either the 30- or 55-degree objective using infrared (820 nm) and autofluorescence (488 nm) modes without OCT, and the 30-degree objective was used for OCT scans. Volume OCT scans were obtained in the macular region of all treated eyes. Supplementary Table S1 details the timing of the imaging sessions.

Electroretinographic analyses of mice

Full-field electroretinograms (ERGs) were recorded using a UTAS Visual Diagnostic System equipped with Big Shot Ganzfeld (LKC Technologies) or a Diagnosys Celeris unit according to methods previously described, with minor modifications.21 Recordings were initially conducted at 6 weeks post injection, with certain cohorts subjected to repeated, longer-term measurements (Table 1). Following overnight dark adaptation, scotopic ERGs were elicited at intensities ranging from −20 to 0 db, with interstimulus intervals of 30 s and averaged from five measurements at each intensity. Mice were then light-adapted to a 30 cds/m2 white background for 7 min. Photopic responses were elicited, with intensities ranging from −3 to 10 dB. Fifty responses with interstimulus intervals of 0.4 s were recorded in the presence of a 20 cds/m2 white background and averaged at each intensity. The Celeris unit was programmed to have identical luminance levels at the respective dB stimuli from the LKC unit. For reference, −20 db = 0.025 cds/m2, 0 db = 2.5 cds/m2, and 10 db = 25 cds/m2. The b-wave amplitudes were defined as the difference between the a-wave troughs to the positive peaks of each waveform. At each time point, maximum scotopic and photopic b-wave amplitudes (those generated at 0 and 10 dB following light adaptation, respectively) from all treated, untreated, and control mice within each cohort were averaged as mean ± standard error. Values were imported into SigmaPlot for final graphical presentation.

Tissue preparation

At approximately 6 or 20 weeks post injection, mouse eyes were enucleated and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for ∼12 h. Eyecups were dissected and prepared for sectioning according to previously described methods.20

At 8 weeks post injection, macaques were euthanized, and their eyes enucleated/processed according to previously published methods, with some modification.36,48 Eyecups were immersed in oxygenated Ames media. Retinas from the OD and OS eyes were then dissected into multiple quadrants. For subject SA65E, the IN retina from the OD eye was flash frozen. The IT and macular retinas were dissociated, and GFP+ cells from these samples were isolated with fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), as before.46 For subject GR114QB, the IT retinas from both OD and OS eyes were dissociated, and GFP+ cells were isolated with FACS. The remaining regions of retina from both eyes were fixed in 4% PFA for 1 h at room temperature and then transferred to 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with sodium azide and stored at 4°C. For subject JR40D, the IT retinas from both OD and OS eyes were flash frozen. The IN and macular retinas were dissociated, and GFP+ cells were isolated with FACS. The fixed retina from subject GR114QB was blocked (5 mm in superior/inferior axis, 8 mm in nasal temporal axis) to isolate macular and IN blebs. Embedding of retina blocks consisted of immersion/equilibration in five different and successive solutions: 10% sucrose/phosphate buffer (PB); 20% sucrose/PB; 30% sucrose/PB; four parts 30% sucrose/PB to one part HistoPrep (Thermo Fisher Scientific); and two parts 30% sucrose/PB to one part HistoPrep. All incubations took place at room temperature for 30 min, except the 30% sucrose/PB, which took place overnight at 4°C. Once the final incubation was complete, the tissue was placed in two parts 30% sucrose to one part Histoprep, oriented, and frozen immediately by partial submersion in liquid nitrogen. Tissue was cut on a cryostat (Leica CM3050 S), with the cabinet and object temperatures set at – 25°C and −15°C, respectively. All sections were 10 μm thick.

IHC and microscopy

Retinal cryosections from mice treated with AAV-CRISPR/Cas9 were immunostained with antibodies raised against retGC1 (1:5,000), cone arrestin (1:100; generously provided by Dr. Clay Smith, University of Florida), or Cas9 (1:150; Abcam ab203943). Following an overnight incubation in primary antibodies at 37°C, immunoglobulin G (IgG) secondary antibodies Alexa Fluor-488, Alexa Fluor-594, or Alexa Fluor-647 were applied for 1 h at room temperature. Sections were counterstained with 4′,6′-diaminio-2-phenylindole (DAPI) for 5 min at room temperature.

Macular cryosections from both the OD and OS eyes and IN cryosections from the OD eye of GR114QB were stained. The IN retina from the OS eye was damaged/lost during the initial eye dissection and thus not processed for IHC. All sections were washed three times with 1 × PBS (15 min each). Samples were then incubated in 0.5% TritonX-100 for 1 h in the dark at room temperature and blocked in a mixture of 10% goat serum in 1× PBS for 1 h at room temperature. Slides containing serial retina samples were then incubated with antibodies raised against retGC1, cone arrestin, or rhodopsin (1:50; generously provided by Dr. Clay Smith, University of Florida) in a solution containing 1% macaque serum in 1× PBS for approximately 12 h at 4°C. Samples were then washed three times with 1× PBS (10 min each) and incubated for 1 h at room temperature with IgG secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes) tagged with Alexa-594 (to label retGC1) or Cy5 (to label cone arrestin or rhodopsin) fluorophores diluted 1:500 in a mixture of 1× PBS containing 3% macaque serum. Autofluorescence eliminator reagent (cat. no. 2160; EMD Millipore) was also applied. Samples were counterstained with DAPI for 5 min at room temperature. After a final rinse with 1× PBS, samples were mounted in an aqueous-based media (DAKO) and coverslipped. Confocal images of retinal sections were obtained with a laser scanning Leica TCS SP8 confocal microscope. Exposure/gain settings remained constant within each experiment.

FACS

Mice were euthanized, retinas were dissociated, and GFP+ PRs were collected, as previously described.49 Immediately following sacrifice, retinas were placed in papain for dissociation (Worthington Papain Dissociation System; cat. no. LK003150). After dissociation, cells were placed in 5% FBS and FACs sorted on a BD FACSAria II. A common template gate was used for all eyes to collect GFP+ PRs. Once collected, cells were pelleted and frozen for further RNA and DNA analysis.

Retinal samples from macaques were dissociated with papain (cat. no. 3150; Worthington) according to the manufacturer's protocol and sorted according to previously published methods, with minor modification.46 In brief, papain was preincubated in 5 mL of Earle's Balanced Salt Solution (EBSS) for 10 min at 37°C. After preincubation, 250 μL of DNase (dissolved in either 500 or 250 μL of EBSS) was added to a final concentration of ∼20 or 40 IU/mL papain and 0.005% DNase. Dissected retina samples were placed in 15 mL falcon tubes containing 700 μL papain/DNase and equilibrated with 95% O2:5% CO2. Retina blocks were dissociated by incubation with activated papain at 37°C for 45 min with constant agitation followed by trituration. Dissociated cells were spun down for 5 min at 2,000 g and re-suspended in 500 μL of re-suspension media (430 μL EBSS, 50 μL albumin-ovomucoid inhibitor, 25 μL DNase). To prepare the density gradient, 600 μL albumin-ovomucoid inhibitor was added to a 15 mL Falcon tube, and the cell suspension was layered on top. Following centrifugation for 6 min at 1,000 rpm, the cells were gently rinsed with 1 × PBS and then re-suspended with 1 × PBS/5% FBS. Sorting of GFP+ and unlabeled cells was performed on a BD FACS ARIA SORP equipped with BD FACS Diva software v8.0.1 and a 100 micron nozzle. The filters used to detect the GFP+ fraction were 505LP and 530/30BP (range 515–545 nm) off the Blue 488 nm laser. Sorted cells were then placed into 15 mL tubes and centrifuged at 2,500 g for 15 min. Supernatant was removed, and cells were re-suspended in 600 μL of RNA later. Samples were then split in half by placing 300 μL of each sample into 1.5 mL tubes.

Representative scatter plots to demonstrate gating conditions in either mouse or macaque sorting experiments are provided in Supplementary Fig. S2.

Nucleic acid isolation from mouse and macaque retinal tissue

Genomic DNA was isolated with the DNEasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen) according to manufacturer's instructions and quantified via Qubit fluorometric quantitation (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Total RNA was isolated with the mirVana miRNA Isolation Kit with phenol (Thermo Fisher Scientific), following the total RNA extraction protocol, according to the manufacturer's instructions, and DNAse was treated with the Turbo DNA-free DNA removal kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

RNA was reverse transcribed with the SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis SuperMix for qRT-PCR Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer's instructions, except that 1 μL of a 52.5 μM stock of a gene-specific primer for reverse transcribing the gRNA is included (5′-TCTCGCCAACAAGTTGACGAG-3′). The Cas9 mRNA and total genomic RNA are reverse transcribed via the random hexamers present in the master mix reagent. Quantitative PCR was performed in triplicate on a CFX384 Real Time PCR Detection System (BioRad) with Taqman Universal PCR Mastermix (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Housekeeping gene control was quantified with Thermo Fisher Mouse GAPDH Endogenous Control #4352932E. Primers targeted to SaCas9 and gRNAs are shown in Supplementary Table S2.

Sequencing to determine editing efficiency

To determine targeted gene editing efficiency, the region surrounding the gRNA cut site was PCR amplified from genomic DNA isolated from retinal tissue or sorted PRs with Phusion High Fidelity DNA Polymerase (New England Biolabs). PCR products were cloned into a plasmid backbone with the Zero-Blunt TOPO kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The TOPO ligation reaction was transformed into chemically competent Top10 cells, and individual colonies were isolated and sequenced by GENEWIZ, Inc. Sanger sequencing reads were aligned to reference sequence to quantify rates of targeted gene editing.

Editing of GUCY2D in macaques was measured via the UDiTaS™ sequencing method, as described in Giannoukos et al.50 The Macaca fascicularis (genome build MacFas5) was used as reference, and primer OLI6908 (5′-GTGACTGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGAT CTGGGCTTGACCGGCTGTGAAAGAATTGGTGT-3′) was used in the UDiTaS reactions. AAV integration events were measured by including AAV production plasmid sequence in an initial alignment step.*

Western blot

Flash-frozen mouse retinas and designated retinal blocks from macaques were processed according to previously described methods.44 The tissue was lysed by sonication (4 × 5 s) in 150 μL RIPA buffer with Halt Protease Inhibitor (cat. no. 1860932; Thermo Fisher Scientific). Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 14,000 g for 10 min at room temperature. The protein concentration of the supernatant was determined with bicinchoninic acid (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and equal amounts of protein were separated on 4–20% polyacrylamide gels (BioRad) and subsequently transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore). Protein from GC1+/−:GC2−/− mouse retinas specifically were separated on 4–12% Tris-glycine gels (Invitrogen). Blots were labeled with antibodies specific for saCas9 (ED009, 1:2,500; Blue Sky), β-actin (1:5,000; Abcam), retGC1 (1:20,000; generously provided by Dr. Alex Dizhoor, Salus University), GCAP1 (“UW101,” 1:20,000; generously provided by Dr. Wolfgang Baehr, University of Utah), and/or cone arrestin (1:100; generously provided by Dr. Clay Smith, University of Florida). Both retGC1 and GCAP1 expression in macaque retinas were normalized to cone arrestin.

Neutralizing antibody assays

ARPE-19 cells (ATCC) were used for detecting NAbs against AAV5 in macaque serum prior to purchase and 2 months after subretinal injections, as previously described.36 Serum samples from subjects SA65E, GR114QB, and JR40D and naïve serum were heat inactivated at 56°C for 35 min. A sample taken from an animal not utilized in this study that was shown previously to be strongly neutralized by AAV5 was used as a positive control. Self-complementary AAV5-smCBA-mCherry vector (multiplicity of infection of 10,000) was diluted in serum-free DMEM/F-12 (1:1) modified medium and incubated with serial 1:4 dilutions (from 1:10 to 1:2,560) of heat-inactivated serum samples in DMEM/F-12 (1:1) modified medium for 1 h at 37°C. Serum/vector mix was used to infect ARPE-19. Three days post infection, cells were imaged under a fluorescence microscope (EVOS, XL Core), dissociated, and counted/analyzed with a BD LSR II flow cytometer equipped with BD FACSDIVA v6.2 (BD Biosciences), as previously described.36 The NAb titer was reported as the highest serum dilution that inhibited scAAV5-smCBA-mCherry transduction (mCherry expression) by ≥50% relative to naïve serum control.

Enzyme-linked immunospot assay

The enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assay was carried out with the ImmunoSpot kit, as per the manufacturer's instruction (C.T.L.). Briefly, macaque peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were thawed, and the concentration was adjusted based on viable cell counts so that a sufficient number of cells (in the range of 100,000–800,000) could be plated per well. The plate was pre-coated with anti-human interferon (IFN)-γ/interleukin (IL)-2 antibodies, and individual SaCas9 peptide pools were added at a final concentration of 10 μg/mL for each peptide pool. Following the addition of PBMCs, the plate was incubated at 37°C and 10% CO2 for 48 h. The plate was then washed, and the captured cytokines were detected via cytokine-specific antibodies followed by chromogenic substrates to measure IFN-γ (red spots) and IL-2 (blue spots). The plate was dried, scanned, and counted on an ELISPOT S6 Universal analyzer along with the ImmunoSpot software (C.T.L.). Detection limits were established by the response definition criteria set for ELISPOT assays by Moodie et al.51

Statistical analysis

All central tendency was measured by the mean. All statistical significance was calculated with a two-sided t-test. Representative groups from each mouse line were used to create histograms of results from OCT and ERG measurements to visualize the normality of the data (data not shown). Error bars on the figures represent the standard error of the mean. Right versus left eye injections were previously tested as covariates for ERG and OCT analysis, and no significant difference was observed (data not shown).

Data availability statement

The data sets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Results

gRNA selection

Editing efficiencies of candidate gRNAs for murine Gucy2e or human GUCY2D were determined by transfecting DNA expressing gRNAs and Cas9 containing plasmid into 3T3 or HEK293 cells, respectively, and assaying for indels via the T7 endonuclease I assay (Supplementary Fig. S3). Gucy2e-gRNA (“guide 16”) resulted in an editing rate of 35%. While not the most efficient guide in mouse 3T3 cells, Gucy2e-gRNA 16 contains four mismatched nucleotides between the Gucy2e and GUCY2D sequence, making it a better control gRNA in editing experiments of macaques (i.e., will not result in editing of orthologue). GUCY2D-gRNA (“guide 27”) was the most efficient editing guide in in HEK293 cells, with an indel rate of 46% (Supplementary Fig. S3). This was further validated by editing in macaque T cells (data not shown). Based on mismatched nucleotides at the respective homologous locations, “guide 27” was also not predicted to target Gucy2e (Fig. 1A). Thus, orthologous guides served as negative controls in all downstream experiments. Species specificity of guides was experimentally confirmed in later in vivo experiments. Vectors used in vivo are depicted in Fig. 1B. Sequencing of WT (C57Bl6) mice and all macaques to be utilized in experiments confirmed no polymorphism occurred at respective gRNA locations (data not shown).

AAV5-hGRK1 capsid/promoter combination drives efficient Cas9 expression in PRs

The AAV5-hGRK1 capsid/promoter combination drives robust and exclusive transgene expression in rod and cone PRs following subretinal injection in mice and primates.36,52 Here, hGRK1 was compared to two commonly used, short, ubiquitous promoters—shortened Elongation Factor Alpha (EFs) and mini Cytomegalovirus Immediate Early (miCMV) in the context of AAV5—for their relative ability to drive Cas9 expression in mouse retina, with emphasis on PRs. Despite EFs and miCMV being ubiquitous promoters and hGRK1 restricting expression to PRs, quantitative PCR revealed the Cas9 transcript was highest in retinas treated with AAV5-hGRK1 (Supplementary Fig. S4A). Ruan et al. also showed that AAV5-hGRK1 drives efficient Cas9 expression in the mouse retina.30 Interestingly, Cas9 protein expression was undetectable in immunoblots of retinas treated with AAV5-hGRK1-Cas9 alone (i.e., no gRNA), suggesting Cas9 protein may be destabilized in the absence of gRNA (Supplementary Fig. S4B). Quantitative PCR also revealed expression of Gucy2e-gRNA16 in retinas of mice subretinally injected with AAV5-Gucy2e-gRNA16-hGRK1-GFP alone. gRNA expression correlated with success of subretinal injection, as evidenced by GFP expression in fundus images and the respective levels of gRNA as measured by quantitative PCR (Supplementary Fig. S5).

AAV-CRISPR/Cas9 efficiently edits Gucy2e in mouse PRs

To determine the efficiency of Gucy2e editing in PRs, AAV5-U6-Gucy2e-gRNA16-hGRK1-GFP and AAV5-hGRK1-Cas9 were subretinally co-injected into the left eyes of WT mice. Right eyes were co-injected with AAV5-hGRK1-Cas9 and control vector, AAV5-U6-GUCY2D-gRNA27-hGRK1-GFP (i.e., containing orthologous control gRNA; Fig. 1B). Fundoscopy at 4 and 6 weeks post injection confirmed GFP expression from gRNA-containing vectors (Supplementary Fig. S6). At 7 weeks post injection, mice were sacrificed, their retinas dissociated, and GFP+ PRs were collected via FACS. In GFP+ PRs from left eyes, 28.7% indels and 16.1% AAV vector insertions were observed at the cut site for a total editing rate of 44.8%. Sequencing of AAV insertions in some cases encompassed the entire insertion (i.e., sequencing reads extending into genomic regions on both sides of the cut site). In some cases, sequencing reactions were terminated. This is likely due to the secondary structure of the ITRs. No editing was observed in GFP–cells or in GFP+ or GFP– cells from right eyes injected with AAV-Cas9 + AAV-orthologous control gRNA. A summary of the sequencing results can be found in Supplementary Table S3.

Quantitative PCR of RNA isolated from sorted cells confirmed Cas9 mRNA and gRNA expression in GFP+ cells from both left and right eyes (Supplementary Fig. S7A). The respective levels of Gucy2e versus GUCY2D gRNA led to the titers of the respective vectors being reevaluated using quantitative PCR. Titers determined via this methodology indicated that Gucy2e gRNA-containing vector was approximately half that of the GUYC2D gRNA-containing vector (data not shown). Thus, 1.5 × 1012 vg/mL of Gucy2e gRNA-containing vector was used rather than 3 × 1012 vg/mL. GFP– cells did not express Cas9 or gRNA. Western blot revealed Cas9 expression in the retinas of both right and left eyes (Supplementary Fig. S7B), contrasting with previous results following injection of AAV-hGRK1-Cas9 alone (Supplementary Fig. S4) and further supporting that Cas9 protein is stabilized by the presence of gRNA.

AAV-CRISPR/Cas9-based editing of Gucy2e in PRs of GC1+/−:GC2−/− mice promotes loss of retinal function and structure as a consequence of reduced retGC1 expression

Mouse PRs express two retinal guanylate cyclases—retGC1 (Gucy2e) and rod-specific retGC2—coded for by Gucy2f. Despite efficient editing of Gucy2e in WT mouse PRs, no changes in retinal function were observed relative to controls at 6 weeks post injection (Supplementary Fig. S8A and B). To discriminate the phenotypic impact of Gucy2e editing on retinal function and structure better, GC1+/−:GC2−/− mice were generated. Retinal guanylate cyclase activity in the PRs of these mice is supported by a single Gucy2e allele. Ablation of Gucy2e in this mouse via CRISPR/Cas9 should lead to a reduction in rod and cone function and PR degeneration over time, as is observed in GCdko mice.9 Left eyes received AAV-Cas9 and AAV-Gucy2e gRNA vectors. Right eyes received AAV-Cas9 and AAV-orthologous gRNA control vectors. Mice were analyzed out to 20 weeks post injection.

At 6 weeks post injection, Gucy2e-targeted eyes had decrements in retinal function relative to controls (Fig. 2A). Response amplitudes in control eyes did not significantly differ from eyes sham injected with vehicle alone. By 20 weeks post injection, responses in Gucy2e-targeted eyes were significantly lower than controls (Fig. 2A and B). Decrements were significant at all light intensities. Differences in retinal structure were also apparent at 20 weeks post injection, with Gucy2e-targeted retinas having significantly thinner ONL than those injected with Cas9 + orthologous gRNA control vectors or vehicle alone (Fig. 2A–C). The magnitude of this difference was greater when restricting the analysis to the superior temporal retina, the location where vector blebs are most consistently created during subretinal injections (Supplementary Fig. S9). Disruption of the Gucy2e locus led to an average 69% reduction of retGC1 expression relative to that seen in control eyes (samples 1–3 vs. samples 4–7; p < 0.05; Fig. 2D and E). Reduction of retGC1 was confirmed via IHC, and was particularly apparent in cones, the cell type with the highest endogenous retGC1 expression in WT mice5 (Fig. 3). Cones outside the injection bleb exhibited clear retGC1 in outer segments (Fig. 3A–D, yellow arrows), whereas cones within the bleb (those predicted to express Cas9 and Gucy2e-gRNA) often lacked retGC1 (Figure 3A, E, F, and G, white arrow). ONL thinning was also observed in the region restricted to the GFP+ injection bleb (Fig. 3A). In contrast, retGC1 expression was consistent within and outside the blebs of control eyes, with no observable changes in ONL (Fig. 3H). As in previous experiments with WT mice, Cas9 transcript was present in all injected eyes (Fig. 2F). Sequencing of DNA from recovered GFP+ PRs at 8 weeks post injection revealed a total editing rate of 32% (28% NHEJ and 4% AAV vector insertions). A summary of sequencing results can be found in Supplementary Table S4. In a separate experiment, GC1+/−:GC2−/− mice were injected with the same vectors at higher concentrations (3 × 1013 vg/mL each, total concentration of 6 × 1013 vg/mL). At 8 weeks post injection, indel analysis revealed editing rates of up to 81% at the target site.

Figure 2.

AAV-CRISPR/Cas9-based editing of Gucy2e in photoreceptors of GC1+/–:GC2−/− mice alters retinal function and structure as a consequence of reduced retGC1 expression. By 20 weeks post injection, photopic (cone-mediated) and scotopic (rod-mediated) function were significantly reduced (p = 0.012 and p = 0.013, respectively) in eyes injected with AAV-Cas9 + AAV-Gucy2e gRNA (n = 10) relative to those injected with AAV-Cas9 + AAV-orthologous gRNA control (n = 10) or vehicle alone (A and B). AAV-Cas9 + AAV-orthologous gRNA control-injected eyes did not differ from vehicle-injected controls (A). By 20 weeks post injection, significant loss of retinal structure was observed in Gucy2e-edited eyes relative to controls (C). Cas9 expression was detectable in all vector-treated eyes (D). retGC1 expression was reduced by ∼70% in Gucy2e-edited eyes relative to eyes injected with AAV-Cas9 + AAV-orthologous gRNA control (D and E). Transcript analysis revealed both Cas9 and gRNA expression in green fluorescent protein (GFP)+ sorted cells from treated eyes (n = 10 pooled for each group) (F). Mice in this cohort received two co-delivered vectors, each at 3 × 1012 vector genomes (vg)/mL, for a total concentration of 6 × 1012 vg/mL.

Figure 3.

Representative retinal cross-sections from GC1+/–:GC2−/− mice injected with either AAV-Cas9 + AAV-Gucy2e gRNA (A–G) or AAV-Cas9 + AAV-orthologous gRNA control (H). The low magnification image from the edited eye clearly shows a reduction of retGC1 expression and ONL thinning within the injection bleb (A). High magnification images taken outside the injection bleb of this eye (B–D) reveal clear retGC1 expression in cone outer segments, whereas retGC1 is absent from cone outer segments within the bleb where editing occurred (G). Sections were stained with antibodies raised against retGC1 (red) and cone arrestin (purple), and counterstained with DAPI (blue). Confocal images are focused on the edge of the subretinal injection bleb. Red and green schematics above the low magnification images reflect the levels of retGC1 and gRNA/GFP expression across each respective section. ONL, outer nuclear layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; GC1, ganglion cell layer. Scale bars in (A) and (H) = 25 μm; scale bars in (B) and (E) = 10 μm.

AAV-CRISPR/Cas9-based editing of GUCY2D in macaque retina results in reduced retGC1 expression and loss of retinal structure

The right eyes of three macaques were subretinally injected with AAV-Cas9 + AAV-GUCY2D gRNA targeted editing vectors, and the left eyes of two macaques were injected with AAV-Cas9 + AAV-orthologous gRNA control vectors (Table 2). GFP+ PRs and GFP– cells from all three macaques were sorted, and DNA was extracted. Using the UDiTaS sequencing method,50 up to 13% editing was observed in PRs sorted from macaque retina injected with GUCY2D gRNA27. As in mouse experiments, gene editing events were a mixture of indels and AAV vector insertions (GR114QB: 6.5% indels and 2.9% AAV vector insertions; JR40D: 9.1% indels and 3.5% AAV vector insertions; SA65E: 12.2% indels and 0.5% AAV vector insertions). Traditional Sanger sequencing revealed slightly higher editing rates in two out of three animals (12.5% in GR114QB, 6.8% in JR40D, and 20.2% in SA65E; Supplementary Table S5). GUCY2D editing was observed only in the GFP+ PRs and not in the GFP– cell population from GUCY2D-targeted right eyes or in GFP+ PRs collected from left eyes.

GFP expression from gRNA-containing vectors was detected in both GUCY2D-edited right (OD) eyes and left eye controls (OS; Fig. 4). OCT scans through the subretinal injection blebs of the GUCY2D-edited eye revealed some loss of ONL and external limiting membrane (ELM) reflectivity within (red arrows) but not outside (blue arrows) the injection region.53 In contrast, there were no gross structural changes in control eyes injected with Cas9 + orthologous gRNA control vectors. Both PRs and ELM were clearly present within the injection bleb of left eyes (red arrows).

Figure 4.

Post-injection fluorescent fundus images and corresponding pre-and post-injection OCT images in macaques. Representative images from OD and OS eyes of GR114QB are shown. Left panels: GFP fluorescence in right and left eyes was detected by 488 nm Spectralis imaging. Horizontal red/blue arrows denote the OCT line scan location, with red denoting the region injected subretinally and blue denoting the uninjected region of the OCT scan. Right panels: OCT images before and 2 months post injection. Vertical red (injected) and blue (uninjected) arrows delimit the region between the outer plexiform layer and the interdigitation zone. Higher power inserts of selected retinal regions show the loss in the right eye post surgically of the ELM and photoreceptors in the injected region. The ELM and photoreceptors are clearly present in the region of the subretinal “control” injection in the left eye. Ch, choroid; ELM, external limiting membrane; EZ, ellipsoid zone of the photoreceptors; IZ, interdigitation zone of cones in RPE; OCT, optical coherence tomography; OPL, outer plexiform layer; RPE, retinal pigment epithelium. Scale bars = 200 μm.

Retinal cross-sections from macular blocks of GR114QB's right and left eyes were immunostained, with the focus placed on the edge of the bleb, where both GFP+ and GFP– PRs (i.e., those predicted to express or not express gRNA, respectively) could be found. These are the same eyes for which fundus and OCT images are provided in Fig. 4. In GUCY2D-edited right eyes, retGC1 was reduced or absent from retina containing GFP+ PRs (Fig. 5A and B). Outer segments within the GFP+ bleb were also noticeably shortened, as indicated by rhodopsin staining in Fig. 5C and D. Outside the bleb, where presumably no GUCY2D-gRNA was expressed, retGC1 was present in the PR OS, which appeared morphologically normal (Fig. 5A and C). Despite a reduction in PR OS length in the GUCY2D-targeted eye, a change in ONL thickness was not observed. While OCT and IHC images were obtained from the central retinas of the same animal (GR114QB), they were not perfectly co-registered, which likely accounts for the discrepancy in ONL thickness. In left eyes injected with Cas9 + orthologous gRNA control vector, retGC1 was visible in PR outer segments (OS) both within and outside the bleb (Fig. 5E and F), and no substantial changes in PR OS or ONL thickness were observed (Fig. 5G and H).

Figure 5.

Representative retinal cross-sections from macaques injected with either AAV-Cas9 + AAV-GUCY2D gRNA (A–D) or AAV-Cas9 + AAV-orthologous gRNA control (E–H). Sections were stained with antibodies raised against retGC1 (red) and rhodopsin (purple), and counterstained with DAPI (blue). Confocal images are focused on the edge of the subretinal injection bleb. Red and green schematics above low magnification images reflect the expression of retGC1 and gRNA/GFP across each respective cross-section. Protein from retinal blocks of GUCY2D-edited and control eyes were probed for retGC1 and cone arrestin (I). retGC1 expression (normalized to cone arrestin) was reduced by ∼80% in GUCY2D-edited eyes (J). Scale bars in (A) and (H) = 25 μm; scale bars in (B) and (E) = 10 μm.

Macaque retinas from both GUCY2D-edited and control eyes were probed for the presence of retGC1 and its biochemical partner GCAP1 via Western blotting. Both were normalized to cone arrestin to control for input. Consistent with IHC, clear reductions in both retGC1 (∼80% reduced) and GCAP1 (∼70% reduced) were observed in GUCY2D-edited samples relative to controls (Fig. 5I and J).

Immunological responses to AAV CRISPR/Cas9 vectors

Serum from all macaques were evaluated for the presence of NAbs against AAV5 prior to and 2 months post injection. All three animals were either naïve or had low NAbs prior to subretinal injections. Two months after injection, all three animals exhibited strong neutralization (>1:2,560).

To determine the potential T-cell responses to Cas9, PBMCs were isolated for subjects JR40D, GR114QB, and SA65E at pretreatment and 4 and 6 weeks post subretinal injection, and they were exposed to SaCas9 peptide antigens in the ELISPOT assay. INF-γ secreted from the activated T cells was captured in situ and quantified. A representative image of the ELISPOT plate is shown in Fig. 6. The control for this ELSIPOT assay was a macaque previously immunized with tetanus, which showed T-cell responses to viral antigens in Pepmix and Tetanus. For clarity, smaller peptides (9mer) are presented through MHC I to CD8 T cells and larger peptides (15mer) are presented through MHC II to CD4 T cells. Low levels of T-cell secreted IFN-γ following incubation with Cas9 peptide pools were detected in JR40D, GR114QB, and SA65E. These positive responses to pooled 15mer peptides are typical responses of memory CD4+ T cells. The lack of detection of IFN-γ responses to Cas9 9mer peptide pools indicates the absence of memory CD8+ T-cell reactivity (Fig. 6). Positive responses were detected in the pretreatment samples of JR40D and SA65E, suggesting preexisting immunity to SaCas9. GR114QB showed responses only in the post-treatment sample, suggesting a treatment-induced response. Low levels of INF-γ response to pools 1 and 2 were also detected at pretreatment in SA65E and post-vector treatment in both JR40D and GR114QB. Neither the preexisting nor the induced Cas9-specific T-cell responses resulted in ocular inflammation in these animals. Furthermore, on-target GUCY2D editing was detected in all three animals, irrespective of the status/level of Cas9-specific T-cell responses.

Figure 6.

Enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assay of T-cell responses to SaCas9. (A) A representative ELISPOT plate image. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells isolated from JR40D at specified time points were plated at 160,000–370,000 cells per well and mixed with individual SaCas9 peptide pool containing ∼36 peptides of either 9mers overlapping by four amino acids, or 15mers overlapping by 10 amino acids. The total peptides from six pools tile the entire SaCas9 protein sequences. The control NHP from CepheusBio was immunized with viral antigens in Pepmix and Tetanus. No T-cell antigens were added to the wells with cells alone. INF-γ-positive spots normalized to 1E6 peripheral blood mononuclear cells are presented in (B) for CD8 T-cell responses to SaCas9 9mer antigens, and (C) for CD4 T-cell responses to SaCas9 15mer antigens.

Discussion

Taken together, the results establish the feasibility of an AAV-CRISPR/Cas9-based strategy for the treatment of GUCY2D-associated cone–rod dystrophy (CORD6). It is shown that disruption of Gucy2e via editing of early coding sequence in a mouse containing a single Gucy2e allele leads to a loss of retinal function and structure resulting from reduced retGC1 expression in PRs. Editing of Gucy2e in GC1+/−:GC2−/− mice produced a phenotype that was expected of a mouse lacking all retinal guanylate cyclase function. Efficient (up to 81%) editing was observed at the cut site. While a fraction of the documented deletions did not alter the open reading frame of retGC1, nevertheless a significant decrease in retGC1 expression was observed. Editing was restricted to PRs by virtue of the capsid (AAV5) and PR-specific promoter (hGRK1) chosen to deliver and express Cas9, respectively. Notably, Cas9 protein was only detected on Western blotting in retinas treated with both AAV-Cas9 and AAV-gRNA vectors, but not AAV-Cas9 alone, suggesting that in PRs, Cas9 may be destabilized in the absence of a gRNA. Indel analysis revealed NHEJ-induced indels and, to a lesser extent, AAV vector insertions at the cut site. Confirming findings by Jarret et al., the majority of AAV genome insertions consisted of an ITR sequence.54 This is unsurprising given the recombinogenic properties of AAV ITRs55 and their interaction with NHEJ host-cell machinery.56 While there has been evidence suggesting AAV integration may be implicated in hepatocellular carcinomas, this is controversial.57,58 It was recently shown that recombinant AAV insertions, including AAV2 ITR sequences, resulting from systemic injections of recombinant AAV5 produced no genotoxic events in NHPs or patients.59 Nevertheless, characterization of insertion events at cut sites should be considered in safety studies supporting human clinical trials.

For the first time, the ability to perform somatic gene editing with AAV-CRISPR/Cas9 in primates is shown. A substantial reduction in retGC1 expression was observed by IHC and Western blotting. Yet, editing rates in GFP+ PRs from macaques were ∼10–20%. This may be a function of PRs that underwent successful editing being lost to degeneration prior to isolation by FACS, as ONL thinning was observed by OCT. Alternatively, GFP expression may be more efficient than Cas9 in PRs, despite both being driven by the same promoter. Future studies in macaques will examine this in more detail. No significant inflammation was observed in macaques subretinally injected with AAV-CRISPR/Cas9 vectors. Increases in NAbs were expected based on the number of subretinal blebs created in both eyes, and were similar to a previous study incorporating bilateral injection of multiple blebs.46 Neither the preexisting nor the induced Cas9-specific T-cell responses resulted in ocular inflammation in these animals, nor did it limit GUCY2D editing. In fact, the animal with the highest pre-dose T-cell response to Cas9 (SA65E) had the highest reported editing efficiency. This is a relevant finding in light of the prevalence of preexisting anti-SaCas9 antibodies in the human population.60

Targeted disruption of GUCY2D led to significant loss (∼70%) of retGC1 expression in macaque PRs, and thinning of ONL within the injection bleb. How does this compare to retinas of LCA1 patients with biallelic recessive mutations in GUCY2D? Early studies of donor retinas revealed retinal degeneration,61,62 but more recent, in-life analyses revealed preservation of retinal laminar architecture in the majority of LCA1 patients.22,63,64 PR degeneration in GUCY2D-edited macaques is unlikely related to the subretinal injection procedure, the vector dose, or Cas9 expression, since control eyes were similarly subjected to all three and did not exhibit degeneration. Differences in retinal structure between GUCY2D-edited macaques and the majority of LCA1 patients are more likely attributed to an abrupt loss of retGC1 versus congenital absence of this protein during development, respectively. In the context of future therapeutic approaches for CORD6, this result indicates that the chronology of gene editing/disruption and expression of vector delivered retGC1 may need to be carefully modulated.

Gene editing in somatic tissues of NHPs is an important step toward biomedical application of CRISPR/Cas9. Additional studies are required, however, before an AAV-CRISPR/Cas9-based treatment for CORD6 can be clinically applied. For example, T-cell responses to Cas9 should be analyzed in a larger number of macaques. While the animals analyzed here had relatively low responses, the sample size was limited to three. A detailed analysis of potential off-target editing events should also be performed.

In summary, the proof of principle results in mice and macaques suggest that AAV-CRISPR/Cas9-based “knockout + complementation in trans” may be an effective strategy for treating CORD6. Notably, this approach could be applied to all allelic forms of CORD6, and builds on 15 years of experience evaluating GUCY2D gene replacement for LCA1.19–21,65 Future studies will address whether PR structure and function are maintained in macaques following editing/disruption of GUCY2D in conjunction with complementation with “hardened” human GUCY2D (i.e., cDNA not recognized by GUCY2D gRNA27). Given that the majority of CORD6 patients carry mutations at a single residue (R838), an allele-targeted approach is also a worthy goal. These approaches would be best evaluated in a humanized knock-in model of CORD6, which would provide the ability to assess editing of mutant GUCY2D in its natural genomic context. Taken together, the results support further development of gene editing approaches to treat CORD6 and the broader application of AAV-CRISPR-Cas9 therapies to address inherited retinal disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

AAV vectors were manufactured at the Powell Gene Therapy Center Vector Core at the University of Florida. We thank Wei Li for performing AAV NAb assays. The following funding was received for this study: NIH/NEI R01 EY024280 to S.E.B., Sponsored Research Agreements from Editas Medicine to S.E.B. and P.D.G., NIH/NEI Core grant P30 EY003039 to U.A.B., NIH/NEI R01 EY025555 to P.D.G., and unrestricted grants from Research to Prevent Blindness to the Departments of Ophthalmology at University of Florida and the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Footnotes

The analysis software is available at https://github.com/editasmedicine/uditas

Author Disclosure

S.E.B. and P.D.G. received funding from Editas Medicine to support these studies. Their role in this project was to provide gRNAs, perform indel analysis on treated retinas, and evaluate T-cell responses in PBMCs isolated from macaques. S.G., S.H., S.S., H.J., and M.L.M. are employees and shareholders of Editas Medicine.

References

- 1. Payne AM, Morris AG, Downes SM, et al. Clustering and frequency of mutations in the retinal guanylate cyclase (GUCY2D) gene in patients with dominant cone–rod dystrophies. J Med Genet 2001;38:611–614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mukherjee R, Robson AG, Holder GE, et al. A detailed phenotypic description of autosomal dominant cone dystrophy due to a de novo mutation in the GUCY2D gene. Eye (Lond) 2014;28:481–487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gregory-Evans K, Kelsell RE, Gregory-Evans CY, et al. Autosomal dominant cone–rod retinal dystrophy (CORD6) from heterozygous mutation of GUCY2D, which encodes retinal guanylate cyclase. Ophthalmology 2000;107:55–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Moore AT. Cone and cone–rod dystrophies. J Med Genet 1992;29:289–290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dizhoor AM, Lowe DG, Olshevskaya EV, et al. The human photoreceptor membrane guanylyl cyclase, RetGC, is present in outer segments and is regulated by calcium and a soluble activator. Neuron 1994;12:1345–1352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Liu X, Seno K, Nishizawa Y, et al. Ultrastructural localization of retinal guanylate cyclase in human and monkey retinas. Exp Eye Res 1994;59:761–768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Olshevskaya EV, Peshenko IV, Savchenko AB, et al. Retinal guanylyl cyclase isozyme 1 is the preferential in vivo target for constitutively active GCAP1 mutants causing congenital degeneration of photoreceptors. J Neurosci 2012;32:7208–7217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Burns ME, Arshavsky VY. Beyond counting photons: trials and trends in vertebrate visual transduction. Neuron 2005;48:387–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Karan S, Frederick JM, Baehr W. Novel functions of photoreceptor guanylate cyclases revealed by targeted deletion. Mol Cell Biochem 2010;334:141–155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Perrault I, Rozet JM, Calvas P, et al. Retinal-specific guanylate cyclase gene mutations in Leber's congenital amaurosis. Nat Genet 1996;14:461–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Perrault I, Rozet JM, Gerber S, et al. Spectrum of retGC1 mutations in Leber's congenital amaurosis. Eur J Hum Genet 2000;8:578–582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kelsell RE, Gregory-Evans K, Payne AM, et al. Mutations in the retinal guanylate cyclase (RETGC-1) gene in dominant cone–rod dystrophy. Hum Mol Genet 1998;7:1179–1184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Perrault I, Rozet JM, Gerber S, et al. A retGC-1 mutation in autosomal dominant cone–rod dystrophy. Am J Hum Genet 1998;63:651–654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tucker CL, Woodcock SC, Kelsell RE, et al. Biochemical analysis of a dimerization domain mutation in RetGC-1 associated with dominant cone–rod dystrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1999;96:9039–9044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wilkie SE, Newbold RJ, Deery E, et al. Functional characterization of missense mutations at codon 838 in retinal guanylate cyclase correlates with disease severity in patients with autosomal dominant cone–rod dystrophy. Hum Mol Genet 2000;9:3065–3073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dizhoor AM, Olshevskaya EV, Peshenko IV. The R838S mutation in retinal guanylyl cyclase 1 (RetGC1) alters calcium sensitivity of cGMP synthesis in the retina and causes blindness in transgenic mice. J Biol Chem 2016;291:24504–24516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sato S, Peshenko IV, Olshevskaya EV, et al. GUCY2D cone–rod dystrophy-6 is a “phototransduction disease” triggered by abnormal calcium feedback on retinal membrane guanylyl cyclase 1. J Neurosci 2018;38:2990–3000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Green DR, Reed JC. Mitochondria and apoptosis. Science 1998;281:1309–1312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Boye SE, Boye SL, Pang J, et al. Functional and behavioral restoration of vision by gene therapy in the guanylate cyclase-1 (GC1) knockout mouse. PLoS One 2010;5:e11306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Boye SL, Conlon T, Erger K, et al. Long-term preservation of cone photoreceptors and restoration of cone function by gene therapy in the guanylate cyclase-1 knockout (GC1KO) mouse. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2011;52:7098–7108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Boye SL, Peshenko IV, Huang WC, et al. AAV-mediated gene therapy in the guanylate cyclase (RetGC1/RetGC2) double knockout mouse model of Leber congenital amaurosis. Hum Gene Ther 2013;24:189–202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jacobson SG, Cideciyan AV, Peshenko IV, et al. Determining consequences of retinal membrane guanylyl cyclase (RetGC1) deficiency in human Leber congenital amaurosis en route to therapy: residual cone-photoreceptor vision correlates with biochemical properties of the mutants. Hum Mol Genet 2013;22:168–183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hsu PD, Lander ES, Zhang F. Development and applications of CRISPR-Cas9 for genome engineering. Cell 2014;157:1262–1278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sander JD, Joung JK. CRISPR-Cas systems for editing, regulating and targeting genomes. Nat Biotechnol 2014;32:347–355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Doudna JA, Charpentier E. Genome editing. The new frontier of genome engineering with CRISPR-Cas9. Science 2014;346:1258096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yin H, Xue W, Chen S, et al. Genome editing with Cas9 in adult mice corrects a disease mutation and phenotype. Nat Biotechnol 2014;32:551–553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ousterout DG, Kabadi AM, Thakore PI, et al. Multiplex CRISPR/Cas9-based genome editing for correction of dystrophin mutations that cause Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nat Commun 2015;6:6244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tabebordbar M, Zhu K, Cheng JKW, et al. In vivo gene editing in dystrophic mouse muscle and muscle stem cells. Science 2016;351:407–411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yu W, Mookherjee S, Chaitankar V, et al. Nrl knockdown by AAV-delivered CRISPR/Cas9 prevents retinal degeneration in mice. Nat Commun 2017;8:14716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ruan GX, Barry E, Yu D, et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing as a therapeutic approach for Leber congenital amaurosis 10. Mol Ther 2017;25:331–341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Koo T, Park SW, Jo DH, et al. CRISPR-LbCpf1 prevents choroidal neovascularization in a mouse model of age-related macular degeneration. Nat Commun 2018;9:1855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Boye SE, Boye SL, Lewin AS, et al. A comprehensive review of retinal gene therapy. Mol Ther 2013;21:509–519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jacobson SG, Boye SL, Aleman TS, et al. Safety in nonhuman primates of ocular AAV2-RPE65, a candidate treatment for blindness in Leber congenital amaurosis. Hum Gene Ther 2006;17:845–858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Maclachlan TK, Lukason M, Collins M, et al. Preclinical safety evaluation of AAV2-sF. Mol Ther 2011;19:326–334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ye GJ, Budzynski E, Sonnentag P, et al. Cone-specific promoters for gene therapy of achromatopsia and other retinal diseases. Hum Gene Ther 2016;27:72–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Boye SE, Alexander JJ, Boye SL, et al. The human rhodopsin kinase promoter in an AAV5 vector confers rod- and cone-specific expression in the primate retina. Hum Gene Ther 2012;23:1101–1115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Beltran WA, Cideciyan AV, Boye SE, et al. Optimization of retinal gene therapy for X-linked retinitis pigmentosa due to RPGR mutations. Mol Ther 2017;25:1866–1880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bakondi B, Lv W, Lu B, et al. In vivo CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing corrects retinal dystrophy in the S334ter-3 rat model of autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. Mol Ther 2016;24:556–563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hung SS, Chrysostomou V, Li F, et al. AAV-mediated CRISPR/Cas gene editing of retinal cells in vivo. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2016;57:3470–3476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bae S, Park J, Kim JS. Cas-OFFinder: a fast and versatile algorithm that searches for potential off-target sites of Cas9 RNA-guided endonucleases. Bioinformatics 2014;30:1473–1475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Yang RB, Robinson SW, Xiong WH, et al. Disruption of a retinal guanylyl cyclase gene leads to cone-specific dystrophy and paradoxical rod behavior. J Neurosci 1999;19:5889–5897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Shen S, Sanchez ME, Blomenkamp K, et al. Amelioration of alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency diseases with genome editing in transgenic mice. Hum Gene Ther 2018;29:861–873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Friedland AE, Baral R, Singhal P, et al. Characterization of Staphylococcus aureus Cas9: a smaller Cas9 for all-in-one adeno-associated virus delivery and paired nickase applications. Genome Biol 2015;16:257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zolotukhin S. Production of recombinant adeno-associated virus vectors. Hum Gene Ther 2005;16:551–557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Timmers AM, Zhang H, Squitieri A, et al. Subretinal injections in rodent eyes: effects on electrophysiology and histology of rat retina. Mol Vis 2001;7:131–137 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Choudhury S, Strang CE, Alexander JJ, et al. Novel methodology for creating macaque retinas with sortable photoreceptors and ganglion cells. Front Neurosci 2016;10:551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Pang JJ, Dai X, Boye SE, et al. Long-term retinal function and structure rescue using capsid mutant AAV8 vector in the rd10 mouse, a model of recessive retinitis pigmentosa. Mol Ther 2011;19:234–242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Boye SE, Alexander JJ, Witherspoon CD, et al. Highly efficient delivery of adeno-associated viral vectors to the primate retina. Hum Gene Ther 2016;27:580–597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kay CN, Ryals RC, Aslanidi GV, et al. Targeting photoreceptors via intravitreal delivery using novel, capsid-mutated AAV vectors. PLoS One 2013;8:e62097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Giannoukos G, Ciulla DM, Marco E, et al. UDiTaS, a genome editing detection method for indels and genome rearrangements. BMC Genomics 2018;19:212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Moodie Z, Price L, Gouttefangeas C, et al. Response definition criteria for ELISPOT assays revisited. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2010;59:1489–1501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Khani SC, Pawlyk BS, Bulgakov OV, et al. AAV-mediated expression targeting of rod and cone photoreceptors with a human rhodopsin kinase promoter. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2007;48:3954–3961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Staurenghi G, Sadda S, Chakravarthy U, et al. Proposed lexicon for anatomic landmarks in normal posterior segment spectral-domain optical coherence tomography: the IN*OCT consensus. Ophthalmology 2014;121:1572–1578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Jarrett KE, Lee CM, Yeh YH, et al. Somatic genome editing with CRISPR/Cas9 generates and corrects a metabolic disease. Sci Rep 2017;7:44624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Inagaki K, Ma C, Storm TA, et al. The role of DNA-PKcs and artemis in opening viral DNA hairpin termini in various tissues in mice. J Virol 2007;81:11304–11321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Young SM, Jr, Samulski RJ. Adeno-associated virus (AAV) site-specific recombination does not require a Rep-dependent origin of replication within the AAV terminal repeat. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2001;98:13525–13530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Nault JC, Datta S, Imbeaud S, et al. Recurrent AAV2-related insertional mutagenesis in human hepatocellular carcinomas. Nat Genet 2015;47:1187–1193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Berns KI, Byrne BJ, Flotte TR, et al. Adeno-associated virus type 2 and hepatocellular carcinoma? Hum Gene Ther 2015;26:779–781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Gil-Farina I, Fronza R, Kaeppel C, et al. Recombinant AAV integration is not associated with hepatic genotoxicity in nonhuman primates and patients. Mol Ther 2016;24:1100–1105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Simhadri VL, McGill J, McMahon S, et al. Prevalence of pre-existing antibodies to CRISPR-associated nuclease Cas9 in the USA population. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 2018;10:105–112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Milam AH, Barakat MR, Gupta N, et al. Clinicopathologic effects of mutant GUCY2D in Leber congenital amaurosis. Ophthalmology 2003;110:549–558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Porto FB, Perrault I, Hicks D, et al. Prenatal human ocular degeneration occurs in Leber's congenital amaurosis (LCA1 and 2). Adv Exp Med Biol 2003;533:59–68 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Simonelli F, Ziviello C, Testa F, et al. Clinical and molecular genetics of Leber's congenital amaurosis: a multicenter study of Italian patients. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2007;48:4284–4290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]