Abstract

Background

The mean age of patients with chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in the USA has been increasing. Despite the increasing proportion of HCV-infected elderly patients, this group is under-represented in clinical trials of HCV treatment.

Aim

We aimed to describe the real-world effectiveness of direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) among elderly patients.

Patients and methods

We retrospectively identified 17 487 HCV-infected patients who were started on treatment with sofosbuvir, ledipasvir/sofosbuvir, or paritaprevir/ombitasvir/ritonavir/dasabuvir-based regimens in the Veterans Affairs Healthcare System between 1 January 2014 and 30 June 2015. We ascertained sustained virologic response (SVR) rates in patients aged below 55, 55–59, 60–64, 65–69, 70–74, and 75 years or older and performed multivariable logistic regression to determine whether age predicted SVR.

Results

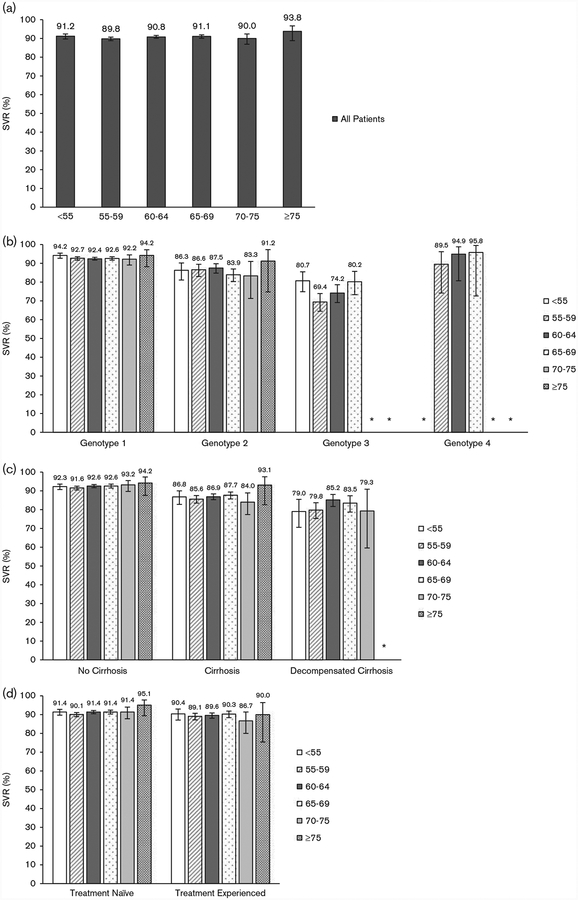

Overall unadjusted SVR rates were 91.2% [95% confidence interval (CI): 89.7–92.4], 89.8% (95% CI: 88.8–90.7), 90.8% (95% CI: 90.1–91.6), 91.1% (95% CI: 90.1–91.9), 90.0% (95% CI: 86.9–92.4), and 93.8% (95% CI: 88.8–96.7) in patients aged below 55, 55–59, 60–64, 65–69, 70–74, and 75 years or older. Unadjusted SVR rates were similar in all age groups after stratifying by genotype, treatment regimen, stage of liver disease, and treatment experience. In multivariate models, age was not predictive of SVR after adjusting for confounders.

Conclusion

DAAs produce high rates of SVR in all age groups, including patients in our oldest age category (≥75 years). Advanced age in and of itself should not be considered a barrier to initiating DAA treatment.

Keywords: age, elderly, ledipasvir, paritaprevir/ombitasvir/ritonavir/dasabuvir, sofosbuvir

Introduction

Most individuals with chronic hepatitis C (HCV) infection in the USA were born between 1945 and 1965 and infected between 1970 and 1990 [1,2] when the incidence of new HCV infections peaked at an estimated 380 000 per year [3]. Members of this ‘baby-boomer’ birth cohort are currently aged 50–70 years and have been infected for 25–45 years. This birth cohort is driving an increase in the average age of HCV-infected patients in the USA [4]. They are also contributing to an increase in the prevalence of cirrhosis and the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) as patients move through the clinical phases of HCV-related liver disease [5].

In anticipation of the aging of the HCV-infected population, it is imperative to understand how elderly patients respond to antiviral therapy as they will soon constitute the majority of patients receiving treatment. Interferon-based treatments were poorly tolerated in most patients, especially in the elderly, because of significant adverse effects. Furthermore, studies of the association between advanced age and likelihood of sustained virologic response (SVR) with interferon-based regimens yielded mixed results. Whereas some studies found that older patients had lower unadjusted SVRs compared with younger patients and more frequent treatment discontinuation or dose reductions [6,7], others found no difference [8,9]. Studies that specifically assessed whether advanced age was an independent predictor of SVR also produced mixed results, with some studies demonstrating an association between age and failure to achieve SVR [6] and others showing that age was not predictive of SVR after adjusting for confounders [8].

The introduction of sofosbuvir (SOF) in December 2013 and of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir (LDV/SOF) and paritaprevir/ritonavir/ombitasvir and dasabuvir (PrOD) in October and December 2014, respectively, made highly effective, well-tolerated, interferon-free antiviral regimens available for most patients. We previously reported that these regimens produce high rates of SVR in real-world practice in veterans with chronic HCV in the USA [10]. Here, we compare the rates of SVR in patients of different age groups treated with SOF-based, LDV/SOF-based, and PrOD-based regimens in the Veterans Affairs (VA) National Healthcare System.

Patients and methods

Data source, study population, and antiviral regimens

Data were obtained from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse [11]. We identified 24 089 HCV antiviral regimens initiated between 1 January 2014 and 30 June 2015 and completed before 1 October 2015 at VA facilities nationally. We excluded 6193 regimens no longer recommended in the VA at the time of the study, such as SOF + simeprevir ± ribavirin (n = 3669), SOF + pegylated interferon ± RBV for genotype 1 HCV (n = 1766), SOF + RBV for genotype 1 HCV (418), or other regimens (n = 340). We excluded 409 duplicate regimens. This left 17 487 patients/regimens in our study. All regimens included SOF, LDV/SOF, or PrOD. Data collection was extended to 10 April 2016 to allow for completion of regimens and ascertainment of SVR.

Sustained virologic response

SVR was defined as a viral load below the lower limit of quantification at least 12 weeks after the end of treatment [12]. When SVR at 12 weeks or more was not available, SVR was defined by viral load testing between 4 and 12 weeks after treatment completion. SVR at 4 weeks was shown to have 98% concordance with SVR at 12 weeks (positive predictive value, 98%; negative predictive value, 100%) in SOF-treated patients [13].

Baseline characteristics

Our data extended to 1 October1999 to ascertain baseline characteristics, which reflect information in medical records before the initiation of antiviral treatment. We extracted baseline characteristics listed in Table 1 based on ICD-9 codes previously validated in VA medical records [5,15–24] (Supplemental Table 1, Supplemental digital content 1, http://links.lww.com/EJGH/A176). We identified relevant laboratory tests and recorded the value closest to the treatment starting date within the preceding 6 months. We also calculated the FIB-4 score [14] [FIB-4 = (age × aspartate transaminase)/(platelets × alanine transaminase1/2)], which correlates with hepatic fibrosis.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients who received antiviral therapy by age category (n = 17 487)

| < 55 (N = 1903) | 55–59 (N = 4441) | 60–64 (N = 6291) | 65–69 (N = 4106) | 70–74 (N = 507) | ≥ 75 (N = 174) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (%) | 91.6 | 95.8 | 97.5 | 99.1 | 99.2 | 97.1 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| White, non-Hispanic (%) | 64.4 | 53.6 | 50.1 | 50.2 | 45.8 | 49.4 |

| Black, non-Hispanic (%) | 18.7 | 29.1 | 30.6 | 30.3 | 33.9 | 28.7 |

| Hispanic (%) | 5.5 | 5.7 | 5.2 | 4.5 | 6.5 | 5.2 |

| Asian, Pacific Islander, American Indian, Alaska Native (%) | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 2.3 |

| Declined to answer, missing (%) | 9.6 | 9.7 | 12.6 | 13.7 | 12.3 | 14.4 |

| Treatment experienced (%) | 23.2 | 29.5 | 30.6 | 29.6 | 30.3 | 24.7 |

| Genotype (%) | ||||||

| 1 | 71.2 | 79.0 | 81.4 | 82.6 | 82.4 | 73.0 |

| 2 | 14.0 | 10.6 | 12.3 | 12.4 | 12.9 | 21.8 |

| 3 | 13.8 | 9.5 | 5.7 | 4.4 | 3.5 | 4.6 |

| 4 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 1.2 | 0.6 |

| Regimen (%) | ||||||

| LDV/SOF | 46.5 | 47.2 | 46.4 | 47.8 | 49.3 | 43.1 |

| LDV/SOF + RBV | 14.4 | 17.6 | 18.9 | 18.0 | 16.4 | 16.1 |

| PrOD (%) | 3.3 | 3.7 | 4.6 | 5.6 | 4.9 | 3.5 |

| PrOD + RBV (%) | 12.4 | 13.9 | 14.2 | 13.3 | 13.9 | 12.1 |

| SOF+RBV (%) | 22.1 | 16.4 | 15.2 | 14.9 | 15.5 | 25.3 |

| PEG + SOF + RBV (%) | 1.4 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 |

| HCV RNA viral load > 6 million IU/ml (%) | 19.0 | 19.5 | 18.7 | 17.7 | 16.2 | 15.5 |

| SVR data missing (%) | 13.3 | 10.0 | 8.4 | 7.8 | 8.2 | 6.9 |

| HIV co-infection (%) | 6.0 | 4.3 | 3.7 | 3.6 | 4.1 | 1.7 |

| Cirrhosis (%) | 20.3 | 29.7 | 31.0 | 32.3 | 35.8 | 36.2 |

| Decompensated cirrhosis (%) | 7.4 | 9.0 | 8.7 | 7.6 | 6.9 | 6.3 |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma (%) | 0.6 | 2.3 | 2.9 | 3.7 | 5.5 | 2.9 |

| Liver transplantation (%) | 0.8 | 1.6 | 2.7 | 2.7 | 2.9 | 4.0 |

| Diabetes (%) | 17.5 | 26.6 | 30.6 | 34.3 | 34.3 | 39.7 |

| Alcohol use disorder (%) | 54.0 | 49.3 | 43.7 | 37.5 | 32.3 | 14.9 |

| Substance use disorder (%) | 50.5 | 42.1 | 35.1 | 30.6 | 23.9 | 10.3 |

| Depression (%) | 53.5 | 48.4 | 47.8 | 44.7 | 37.4 | 31.6 |

| PTSD (%) | 28.7 | 16.1 | 24.4 | 42.1 | 24.9 | 8.6 |

| Anxiety/panic (%) | 43.8 | 35.1 | 33.5 | 30.9 | 26.0 | 22.4 |

| Schizophrenia (%) | 5.9 | 6.0 | 5.4 | 4.6 | 5.3 | 0.6 |

| Laboratory results | ||||||

| Anemiaa (%) | 9.1 | 11.9 | 14.4 | 18.1 | 24.9 | 28.2 |

| Platelet count < 100 k/μl (%) | 11.1 | 14.2 | 14.1 | 13.2 | 12.9 | 13.8 |

| Creatinine > 1.1 mg/dl (%) | 12.7 | 15.0 | 20.7 | 24.3 | 31.1 | 41.1 |

| Bilirubin > 1.1 g/dl (%) | 12.3 | 14.5 | 14.6 | 13.2 | 14.6 | 12.4 |

| Albumin <3.6 g/dl (%) | 14.2 | 20.6 | 21.4 | 21.1 | 22.1 | 23.0 |

| INR > 1.1 (%) | 16.7 | 22.0 | 21.5 | 23.7 | 25.8 | 29.8 |

| FIB-4 score > 3.25 (%)b | 25.6 | 33.2 | 37.0 | 39.0 | 46.7 | 56.8 |

ALT, alanine transaminase; AST, aspartate transaminase; HCV, hepatitis C virus; INR, international normalized ratio; LDV/SOF, ledipasvir/sofosbuvir; PrOD, paritaprevir/ritonavir/ombitasvir and dasabuvir; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; RBV, ribavirin; SOF, sofosbuvir; SVR, sustained virologic response.

Anemia is defined as a hemoglobin concentration < 13 g/dl in men or < 12 g/dl in women.

FIB-4 score = [age × AST]/[platelets × ALT1/2] [14].

Statistical analysis

We assessed SVR rates by age group, genotype, treatment regimen, and clinical subgroups. Multivariable logistic regression models were used to evaluate the association between age and SVR, adjusting for potential confounders (sex, race/ethnicity, history of alcohol use disorders, HCV genotype and subgenotype, HCV regimen, baseline HCV viral load, diabetes, treatment naive/experienced, cirrhosis, decompensated cirrhosis, HCC, liver transplantation, platelet count, and serum bilirubin and albumin levels). A significant proportion of patients (9%, N = 1603) had missing SVR data. To evaluate the impact of missing SVR, we compared baseline characteristics of patients with and without SVR data to determine whether there were significant differences that could bias our results. We also compared treatment durations of patients with and without SVR data to determine whether patients missing SVR were more likely to have early treatment discontinuation and thus lower likelihood of achieving SVR. Finally, we used multiple imputation to calculate missing SVR values using a logistic regression model with baseline characteristics shown in Table 1 and duration of treatment. Analyses were performed using Stata/MP, version 14.1 (64-bit) (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

Baseline characteristics

The mean age of the treatment recipients was 60.8 (± 6.5) years and the median age was 61 years. The age distribution was as follows: 10.9% patients younger than 55 years, 25.5% 55–59-year-old, 36.1% 60–64-year-old, 23.6% 65–69-year-old, 2.9% 70–74-year-old, and 1.0% patients aged 75 years or older. Genotype 1 HCV was slightly less prevalent in patients younger than 55 (71.2%) years and 75 (73.0%) years or older compared with patients in other age groups (Table 1). Genotype 2 was more common among patients 75 (21.8%) years or older, whereas genotype 3 was more common among patients younger than 55 (13.8%) years. The proportion of patients with cirrhosis increased with age, ranging from 20.3% of patients aged below 55 to 36.2% of patients aged 75 years or older. Likewise, the proportion with FIB-4 score more than 3.25 increased progressively from 25.6% in patients aged below 55 to 56.8% in patients aged 75 years or older. The proportion of patients with diabetes was greater in older age groups (Table 1). Older patients were less likely to have alcohol and substance use disorders, depression, or anxiety and more likely to have laboratory abnormalities including anemia, elevated creatinine, low albumin, and elevated international normalized ratio (Table 1). Older patients were also slightly less likely to have missing SVR data compared with younger patients.

Association between age and sustained virologic response within different genotypes and treatment regimens

The observed SVR rates among the 15 884 patients with available SVR data are shown in Table 2 and Fig. 1. Overall rates of SVR were similar across age bands, including patients younger than 55 (91.2%) years, between 55 and 59 (89.8%) years, 60 and 64 (90.8%) years, 65 and 69 (91.1%) years, 70 and 74 (90.0%) years, and 75 (93.8%) years or older (Fig. 1a and Table 2). There were no consistent age-related trends after stratifying by genotype and treatment regimen (Fig. 1b and Table 2). Among patients with genotype 1 infection, rates of SVR were similar in all age groups, including in patients younger than 55 (94.2%) years, between 55 and 59 (92.7%) years, 60 and 64 (92.4%) years, 65 and 69 (92.6%) years, 70 and 74 (92.2%) years, and 75 (94.2%) years or older. SVRs were lower in genotype 2-infected patients but similar between age groups with all confidence intervals (CIs) overlapping, ranging from 83.3% (95% CI: 71.3–91.0) in patients aged 70–74 to 91.2% (95% CI: 74.8–97.3) in patients aged 75 years or older (Fig. 1b and Table 2). Genotype 3-infected patients had the lowest SVR rates, ranging from 69.4% (95% CI: 64.5–73.9) in patients aged 55–59 to 80.7% (95% CI: 74.9–85.5) in patients younger than 55 (although 100% of patients ≥ 75 years with genotype 3 attained SVR, there were only six patients in this subgroup) (Fig. 1b and Table 2).

Table 2.

Sustained virologic response rates by age group among clinically relevant subgroups

| % (95% CI) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients (N = 15 884) | < 55 (N = 1651) | 55–59 (N = 3997) | 60–64 (N = 5766) | 65–69 (N = 3788) | 70–74 (N = 469) | ≥ 75 (N = 162) | |

| All patients | 90.7 (90.2–91.1) | 91.2 (89.7–92.4) | 89.8 (88.8–90.7) | 90.8 (90.1–91.6) | 91.1 (90.1–91.9) | 90.0 (86.9–92.4) | 93.8 (88.8–96.7) |

| Genotype/regimen | |||||||

| 1 | 92.7 (92.3–93.2) | 94.2 (92.7–95.4) | 92.7 (91.7–93.5) | 92.4 (91.7–93.2) | 92.6 (91.7–93.5) | 92.2 (89.1 −94.5) | 94.2 (88.2–97.2) |

| LDV/SOF | 92.8 (92.2–93.4) | 94.4 (92.5–95.8) | 92.9 (91.7–94.0) | 92.2 (91.2–93.2) | 92.8 (91.5–93.9) | 93.4 (89.4–96.0) | 92.9 (83.7–97.1) |

| LDV/SOF+ RBV | 92.0 (90.9–93.0) | 94.8 (90.2–97.3) | 91.7 (89.2–93.6) | 92.2 (90.4–93.7) | 91.8 (89.3–93.7) | 85.7 (75.1 −92.3) | 96.0 (73.7–99.5) |

| PrOD | 94.9 (93.0–96.3) | 98.1 (86.8–99.7) | 93.3 (88.0–96.4) | 94.3 (90.7–96.5) | 95.3 (91.4–97.4) | 100 | 100a |

| PrOD + RBV | 92.5 (91.3–93.5) | 92.0 (87.3–95.1) | 92.6 (90.0–94.5) | 92.9 (90.9–94.5) | 91.9 (89.2–94.0) | 92.3 (82.5–96.8) | 95.0a (67.7–99.4) |

| 2 | |||||||

| SOF+RBV | 86.2 (84.6–87.7) | 86.3 (81.1−90.2) | 86.6 (83.0–89.5) | 87.5 (84.8–89.8) | 83.9 (80.3–87.0) | 83.3 (71.3–91.0) | 91.2 (74.8–97.3) |

| 3 | 74.8 (72.2–77.3) | 80.7 (74.9–85.5) | 69.4 (64.5–73.9) | 74.2 (69.1 −78.6) | 80.2 (73.3–85.7) | 72.2a (45.3–89.1) | 100a |

| LDV/SOF+ RBV | 77.9 (73.2–82.0) | 81.8 (70.3–89.5) | 73.0 (63.3–80.9) | 75.9 (67.0–83.0) | 84.7 (72.8–92.0) | 80.0a (11.1 −99.2) | 100a |

| SOF + PEG + RBV | 87.0 (80.0–91.8) | 100 | 91.1 (77.9–96.8) | 78.7 (64.2–88.4) | 78.6 (46.0–94.0) | - | - |

| SOF+RBV | 70.6 (66.9–74.1) | 76.4 (68.1−83.0) | 63.6 (57.2–69.6) | 71.7 (64.3–78.1) | 77.5 (67.5–85.1) | 69.2a (36.5–89.8) | 100a |

| 4 | |||||||

| LDV/SOF or PrOD ± RBV | 89.6 (82.8–93.9) | 76.5 (48.2–91.9) | 89.5 (74.2–96.2) | 94.9 (80.7–98.8) | 95.8 (72.6–99.5) | 66.7a (14.9–95.8) | 100a |

| No cirrhosis | 92.3 (91.8–92.8) | 92.3 (90.7–93.6) | 91.6 (90.5–92.5) | 92.6 (91.7–93.4) | 92.6 (91.5–93.6) | 93.2 (89.7–95.5) | 94.2 (87.6–97.4) |

| Cirrhosis | 86.8 (85.8–87.7) | 86.8 (82.8–90.0) | 85.6 (83.5–87.5) | 86.9 (85.3–88.4) | 87.7 (85.7–89.4) | 84.0 (77.4–88.9) | 93.1 (82.6–97.5) |

| Decompensated cirrhosis | 82.6 (80.5–84.6) | 79.0 (70.6–85.5) | 79.8 (75.3–83.7) | 85.2 (81.7–88.1) | 83.5 (78.7–87.4) | 79.3 (59.6–90.9) | 81.8a (42.0–96.5) |

| HCC | 74.4 (70.0–78.3) | 63.6a (28.8–88.3) | 73.3 (63.1–81.6) | 75.9 (68.7–81.9) | 74.8 (66.6–81.6) | 62.5 (40.6–80.2) | 100a |

| HIV | 92.1 (89.8–93.9) | 91.5 (84.3–95.6) | 91.7 (86.6–94.9) | 93.8 (89.6–96.4) | 90.5 (84.2–94.4) | 89.5a (62.9–97.7) | 100a |

| Liver transplantation | 94.5 (91.6–96.4) | 100a | 94.1 (85.0–97.8) | 95.5 (90.8–97.8) | 91.3 (83.9–95.4) | 100a | 100a |

| Treatment naive | 91.1 (90.6–91.6) | 91.4 (89.7–92.8) | 90.1 (88.9–91.1) | 91.4 (90.5–92.2) | 91.4 (90.3–92.4) | 91.4 (87.8–94.0) | 95.1 (89.4–97.8) |

| Treatment experienced | 89.7 (88.7–90.5) | 90.4 (87.1 −93.0) | 89.1 (87.2–90.7) | 89.6 (88.1 −90.9) | 90.3 (88.4–91.9) | 86.7 (80.0–91.4) | 90.0 (75.4–96.4) |

CI, confidence interval; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; LDV/SOF, ledipasvir/sofosbuvir; PrOD, paritaprevir/ritonavir/ombitasvir and dasabuvir; RBV, ribavirin; SOF, sofosbuvir.

These subgroups contained 20 patients or fewer.

Fig. 1.

(a) Sustained virologic responses (SVRs) in all patients by age group. (b) SVRs by genotype and age group. (c) SVRs by stage of liver disease and age group. (d) SVRs by prior treatment experience and age group. *Subgroups containing 20 patients or fewer are not depicted.

Association between age and sustained virologic response within subgroups defined by cirrhosis or receipt of prior treatment

Among noncirrhotic patients, SVR rates were more than 90% in all age groups with minimal variability between groups (Fig. 1c and Table 2). Compared with noncirrhotic individuals, patients with cirrhosis or with decompensated cirrhosis generally had lower SVRs but SVRs were similar between age groups (Fig. 1c and Table 2). HCV treatmentnaive patients had slightly higher rates of SVR than treatment-experienced patients, with no major differences in SVRs between age groups (Fig. 1d and Table 2).

Association between age and sustained virologic response in multivariable models

We used multivariable logistic regression models to determine whether age was an independent predictor of SVR. After adjustment for baseline characteristics, age was not significantly associated with the likelihood of achieving SVR either in the entire population or in genotype-specific analyses (Table 3).

Table 3.

The association between age and sustained virologic response in multivariable logistic regression models, presented for all patients and separately by genotypea

| All patients | Genotype 1 | Genotype 2 | Genotype 3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | AORb | P-value | AORb | P-value | AORb | P-value | AORb | P-value |

| < 55 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 55–59 | 0.88 | 0.2 | 0.87 | 0.3 | 1.37 | 0.2 | 0.58 | 0.01 |

| 60–64 | 0.95 | 0.6 | 0.84 | 0.2 | 1.61 | 0.05 | 0.73 | 0.2 |

| 65–69 | 0.95 | 0.6 | 0.86 | 0.3 | 1.20 | 0.5 | 1.12 | 0.7 |

| 70–74 | 0.91 | 0.6 | 0.86 | 0.5 | 1.41 | 0.4 | 0.81 | 0.7 |

| ≥ 75 | 1.62 | 0.2 | 1.22 | 0.7 | 3.04 | 0.09 | NA | |

Genotype 4-infected patients were not modeled separately as there were too few for robust multivariable models.

AOR, adjusted odds ratio, by multivariable logistic regression modeling including the following variables: age, sex, race/ethnicity, history of alcohol use disorders, HCV genotype and subgenotype, HCV regimen, baseline HCV viral load, diabetes, treatment naive/experienced, cirrhosis, decompensated cirrhosis, HCC, liver transplantation, platelet count, serum bilirubin and albumin levels.

Impact of missing sustained virologic response data

Of the 17 487 patients in the study, 1603 (9%) had missing SVR data. Missing SVR was progressively more prevalent in younger age groups, ranging from 6.9% in patients aged 75 years or older to 13.3% in patients aged below 55 years (Table 1). We did not find significant differences in predictors of SVR, such as race/ethnicity, age, genotype, cirrhosis, and decompensated cirrhosis, between patients with and those without SVR data (Supplemental Table 2, Supplemental digital content 2, http://links.lww.com/EJGH/A177). Rates of early treatment discontinuation (defined as < 8 weeks of treatment) were higher in patients with missing SVR compared with those with available SVR (25 vs. 4.4%). However, the majority (75%) of patients with missing SVR completed 8 or more weeks of treatment and the mean duration of treatment was 71 ± 38 days compared with 87 ± 31 days in patients with available SVR. Thus, most patients without SVR data did not drop out of treatment but had not yet undergone follow-up HCV viral load testing in the relatively short follow-up period of our study. Lastly, when multiple imputation was used to derive missing SVR values after including baseline characteristics as well as duration of treatment, results that included both imputed and observed SVRs were only slightly lower than observed SVRs. Imputed results also showed little or no difference in SVR between different age groups (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of observed sustained virologic response among patients with available sustained virologic response data (n = 15 884) and combined observed or imputed sustained virologic response among all patients who initiated antiviral treatment (n = 17 301)

| Observed SVR (N = 15 884) % (95% CI) | Observed SVR or imputed SVRa for patients missing SVR data (N = 17 301) % (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| All patients | 90.7 (90.2–91.1) | 90.0 (89.6–90.5) |

| Age groups | ||

| < 55 | 91.2 (89.7–92.4) | 90.3 (88.8–91.8) |

| 55–59 | 89.8 (88.8–90.7) | 89.3 (88.3–90.3) |

| 60–64 | 90.8 (90.1–91.6) | 90.2 (89.4–91.0) |

| 65–69 | 91.1 (90.1–91.9) | 90.5 (89.5–91.4) |

| 70–74 | 90.0 (86.9–92.4) | 89.5 (86.8–92.3) |

| ≥ 75 | 93.8 (88.8–96.7) | 92.9 (88.6–97.1) |

| Genotype 1 | ||

| < 55 | 94.2 (92.7–95.4) | 93.7 (92.2–95.1) |

| 55–59 | 92.7 (91.7–93.5) | 92.2 (91.3–93.1) |

| 60–64 | 92.4 (91.7–93.2) | 92.0 (91.3–92.8) |

| 65–69 | 92.6 (91.7–93.5) | 92.0 (91.1 −93.0) |

| 70–74 | 92.2 (89.1 −94.5) | 91.6 (88.9–94.4) |

| ≥ 75 | 94.2 (88.2–97.2) | 93.7 (89.2–98.2) |

| Genotype 2 | ||

| < 55 | 86.3 (81.1–90.2) | 84.2 (79.5–89.0) |

| 55–59 | 86.6 (83.0–89.5) | 85.7 (82.3–89.1) |

| 60–64 | 87.5 (84.8–89.8) | 86.1 (83.4–88.7) |

| 65–69 | 83.9 (80.3–87.0) | 83.7 (80.3–87.1) |

| 70–74 | 83.3 (71.3–91.0) | 83.0 (73.1 −92.9) |

| ≥ 75 | 91.2 (74.8–97.3) | 91.2 (81.2–100) |

| Genotype 3 | ||

| < 55 | 80.7 (74.9–85.5) | 80.0 (74.8–85.1) |

| 55–59 | 69.4 (64.5–73.9) | 68.9 (64.3–73.6) |

| 60–64 | 74.2 (69.1 −78.6) | 72.4 (67.4–77.4) |

| 65–69 | 80.2 (73.3–85.7) | 79.6 (73.5–85.6) |

| 70–74 | -b | -b |

| ≥ 75 | -b | -b |

| Genotype 4 | ||

| < 55 | -b | -b |

| 55–59 | 89.5 (74.2–96.2) | 86.3 (74.5–98.1) |

| 60–64 | 94.9 (80.7–98.8) | 92.6 (82.9–100) |

| 65–69 | 95.8 (72.6–99.5) | 91.9 (79.7–100) |

| 70–74 | -b | -b |

| ≥ 75 | -b | -b |

CI, confidence interval; SVR, sustained virologic response.

Imputed by multiple imputation using a logistic regression model that included duration of treatment together with 24 baseline patient characteristics shown in Table 1. The number of patients is slightly less than 17487 because of missing data in the characteristics used to impute SVR.

Subgroups with 20 patients or fewer were not assessed.

Discussion

Options for the treatment of chronic HCV have improved considerably with the advent of DAA regimens, which have high efficacy and excellent safety profiles. DAAs hold promise in the successful treatment of HCV in clinical subgroups that have traditionally been challenging to treat. Elderly patients represent a significant and rapidly increasing proportion of patients infected with chronic HCV. Our results demonstrate that SOF-based, LDV/SOFbased, and PrOD-based regimens result in high rates of SVR in patients of advanced age. Among difficult-to-treat subgroups, including patients with genotypes 2 and 3, cirrhosis, and decompensated cirrhosis, elderly patients had similar SVRs compared with younger patients. After adjusting for important factors associated with SVR in multivariate models, we found that age was not associated with SVR.

There are few studies examining the association between advanced age and SVR following DAA therapy. Elderly patients are often under-represented in existing clinical trials. In the ION-1, ION-2, and ION-3 trials, for example, although there was no upper limit of age for inclusion in the study, the number of patients aged 65 or older was too small to compare SVR between younger and older patients [25–27]. A recent post-hoc pooled analysis of the ION trials and a Japanese trial showed that genotype 1 patients 65 years or older attained SVR rates (98%) equivalent to those of patients younger than 65 years (97%) when treated with LDV/SOF ± ribavirin [28], which is consistent with our results. There were only 264 patients aged 65 years or older in these four trials combined and only 24 patients aged 75 years or older. Trials of PrOD for genotype 1 HCV and SOF-based regimens for genotypes 2 and 3 HCV examined age subgroups using cutoffs of 55 or 50 [29–33]. Therefore, the efficacy of DAAs among patients older than 60 or 65 years cannot be determined from these trials.

The mean age of HCV-infected patients in the USA is expected to continue to increase. As of 2016, patients in the HCV ‘baby-boomer’ birth cohort born during 1945–1965 were aged 51–71 years. As members of this cohort age, physicians, patients and third-party payers will increasingly be faced with antiviral treatment decisions in elderly patients. The effectiveness of treatment options is an important consideration when making these decisions.

Our study shows that DAAs produce high SVRs even in the oldest age cohort (≥75 years) and that advanced age is not an independent negative predictor of SVR. Thus, our results should reassure providers that DAA therapy in older individuals offers similar likelihood of HCV clearance as in younger individuals.

Many other factors besides the SVR rate warrant consideration when contemplating HCV treatment in elderly patients, including competing comorbidities, likelihood of progression of liver disease, and long-term benefits of HCV clearance. For example, elderly patients may have comorbidities with greater impact on morbidity and life expectancy than chronic HCV infection. In contrast, elderly patients may also have strong indications for HCV treatment due to the presence of more advanced liver disease. Indeed, our data show that elderly patients are more likely to have cirrhosis or an FIB-4 score of more than 3.25 compared with younger patients (Table 1), and prior studies suggest that older age is associated with increased risk for complications related to chronic HCV, including accelerated progression to cirrhosis, HCC, and mortality [9]. Therefore, elderly patients may derive substantial benefit from achieving SVR, especially if they lack other serious comorbidities.

The impact of DAA therapy on long-term outcomes requires further investigation and should be considered when making treatment decisions. Our results suggest that antiviral treatment should not, however, be withheld on the basis of age in isolation. This is important to highlight because older age has been shown to be independently associated with a lower likelihood of receiving HCV treatment [8,9,20]. Current guidelines do not specify an age limit for consideration of HCV treatment [34]. We agree with continuing this approach and advocate that clinicians carefully consider patients of all age groups for HCV treatment.

An important limitation to our study is that 9% of patients (N =1603) had missing SVR, potentially causing overestimation of SVRs. However, we think bias was unlikely. First, baseline characteristics of patients with and without SVR data were similar, implying that their response to treatment should also be similar. Although more patients without SVR data had early discontinuation, the majority (75%) of patients lacking SVR data completed at least 8 weeks of treatment and had a mean treatment duration of 71 days (Supplemental Table 2, Supplemental digital content 2, http://links.lww.com/EJGH/A177). When multiple imputation was used to derive missing SVRs – incorporating both baseline characteristics and duration of treatment – there was little difference between imputed and observed results (Table 4). Additionally, it was less common for elderly patients to be missing SVR; thus, even if SVR rates were slightly overestimated on account of missing data, they would be less overestimated in older patients than in younger patients. Another limitation is that we did not examine the characteristics of elderly patients with HCV who were not offered treatment in the VA population, and therefore it is possible that the older patients in our study were highly selected.

The strengths of our study include a large sample size of patients aged 60 or older and the use of a national healthcare sample. Our study population also included large numbers of patients in many important clinical subgroups. Although comparing SVRs between each of these subgroups was not the aim of our study, it does allow for some important observations. We have shown, for example, that patients with genotypes 2, 3, and 4 have lower SVR rates compared with genotype 1 patients in all age groups with LDV/SOF-based, SOF-based, and PrOD based regimens. In addition, our study population included a large proportion of patients with alcohol and substance use disorders, as well as patients with psychiatric disease (Table 1), suggesting that patients with these comorbid conditions can be successfully treated with DAAs.

Conclusion

We demonstrate that DAA-based HCV regimens produce high SVRs in patients of advanced age. Clinicians should consider many factors when advising elderly patients on HCV treatment, including comorbid conditions, likelihood of liver disease progression, and potential benefits of HCV eradication. Further research is needed to examine the impact of DAA therapy on long-term HCV-related outcomes especially in elderly patients. Advanced age in and of itself, however, should not be considered a barrier to antiviral treatment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The study was funded by a Merit Review grants (I01CX000320 and I01CX001156), Clinical Science Research and Development, Office of Research and Development, Veterans Affairs (G.N.I.).

All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

George Ioannou is the guarantor of this paper. George Ioannou: Study concept and design, acquisition of data, statistical analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript, obtained funding; Feng Su: Study concept and design, interpretation of data, drafting of manuscript and critical revision of the manuscript; Lauren Beste: Critical revision of the manuscript; Pamela Green: Analysis of data; Kristin Berry: Study design and statistical analysis of data.

Footnotes

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s website (www.eurojgh.com).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Smith BD, Morgan RL, Beckett GA, Falck-Ytter Y, Holtzman D, Teo CG, et al. Centers for Disease C, Prevention. Recommendations for the identification of chronic hepatitis C virus infection among persons born during 1945–1965. MMWR Recomm Rep 2012; 61 (RR-4):1–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rein DB, Smith BD, Wittenborn JS, Lesesne SB, Wagner LD, Roblin DW, et al. The cost-effectiveness of birth-cohort screening for hepatitis C antibody in U.S. primary care settings. Ann Intern Med 2012; 156:263–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Armstrong GL, Alter MJ, McQuillan GM, Margolis HS. The past incidence of hepatitis C virus infection: implications for the future burden of chronic liver disease in the United States. Hepatology 2000; 31:777–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis GL, Alter MJ, El-Serag H, Poynard T, Jennings LW. Aging of hepatitis C virus (HCV)-infected persons in the United States: a multiple cohort model of HCV prevalence and disease progression. Gastroenterology 2010; 138:513–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beste LA, Leipertz SL, Green PK, Dominitz JA, Ross D, Ioannou GN. Trends in burden of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma by underlying liver disease in US veterans, 2001–2013. Gastroenterology 2015; 149:1471.e5–1482.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roeder C, Jordan S, Schulze Zur Wiesch J, Pfeiffer-Vornkahl H, Hueppe D, Mauss S, et al. Age-related differences in response to peginterferon alfa-2a/ribavirin in patients with chronic hepatitis C infection. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20:10984–10993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sato I, Shimbo T, Kawasaki Y, Mizokami M, Masaki N. Efficacy and safety of interferon treatment in elderly patients with chronic hepatitis C in Japan: a retrospective study using the Japanese Interferon Database. Hepatol Res 2015; 45:829–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsui JI, Currie S, Shen H, Bini EJ, Brau N, Wright TL. Treatment eligibility and outcomes in elderly patients with chronic hepatitis C: results from the VA HCV-001 Study. Dig Dis Sci 2008; 53:809–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.El-Serag HB, Kramer J, Duan Z, Kanwal F. Epidemiology and outcomes of hepatitis C infection in elderly US veterans. J Viral Hepat 2016; 23:687–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ioannou GN, Beste LA, Chang MF, Green PK, Lowy E, Tsui JI, et al. Effectiveness of sofosbuvir, ledipasvir/sofosbuvir, or paritaprevir/ritonavir/ombitasvir and dasabuvir regimens for treatment of patients with hepatitis C in the Veterans Affairs National Health Care System. Gastroenterology 2016; 151:457.e5–471.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.US Department of Veterans Affairs. Veterans affairs informatics and computing infrastructure. Available at: http://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/for_researchers/vinci/cdw.cfm [Accessed 10 February 2016].

- 12.Zeuzem S, Heathcote EJ, Shiffman ML, Wright TL, Bain VG, Sherman M, et al. Twelve weeks of follow-up is sufficient for the determination of sustained virologic response in patients treated with interferon alpha for chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol 2003; 39:106–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoshida EM, Sulkowski MS, Gane EJ, Herring RW Jr, Ratziu V, Ding X, et al. Concordance of sustained virological response 4, 12, and 24 weeks post-treatment with sofosbuvir-containing regimens for hepatitis C virus. Hepatology 2015; 61:41–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vallet-Pichard A, Mallet V, Nalpas B, Verkarre V, Nalpas A, DhalluinVenier V, et al. FIB-4: an inexpensive and accurate marker of fibrosis in HCV infection. comparison with liver biopsy and fibrotest. Hepatology 2007; 46:32–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kramer JR, Davila JA, Miller ED, Richardson P, Giordano TP, ElSerag HB. The validity of viral hepatitis and chronic liver disease diagnoses in Veterans Affairs administrative databases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2008; 27:274–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kramer JR, Giordano TP, Souchek J, Richardson P, Hwang LY, ElSerag HB. The effect of HIV coinfection on the risk of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in U.S. veterans with hepatitis C. Am J Gastroenterol 2005; 100:56–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ioannou GN, Splan MF, Weiss NS, McDonald GB, Beretta L, Lee SP. Incidence and predictors of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007; 5:938–945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davila JA, Henderson L, Kramer JR, Kanwal F, Richardson PA, Duan Z, El-Serag HB. Utilization of surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma among hepatitis C virus-infected veterans in the United States. Ann Intern Med 2011; 154:85–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ioannou GN, Bryson CL, Weiss NS, Miller R, Scott JD, Boyko EJ. The prevalence of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Hepatology 2013; 57: 249–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kramer JR, Kanwal F, Richardson P, Giordano TP, Petersen LA, ElSerag HB. Importance of patient, provider, and facility predictors of hepatitis C virus treatment in veterans: a national study. Am J Gastroenterol 2011; 106:483–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beste LA, Ioannou GN, Larson MS, Chapko M, Dominitz JA. Predictors of early treatment discontinuation among patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C and implications for viral eradication. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010; 8:972–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Backus LI, Boothroyd DB, Phillips BR, Mole LA. Predictors of response of US veterans to treatment for the hepatitis C virus. Hepatology 2007; 46:37–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kanwal F, Hoang T, Kramer JR, Asch SM, Goetz MB, Zeringue A, et al. Increasing prevalence of HCC and cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Gastroenterology 2011; 140:1182.e1–1188. e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller DR, Safford MM, Pogach LM. Who has diabetes? Best estimates of diabetes prevalence in the Department of Veterans Affairs based on computerized patient data. Diabetes Care 2004; 27 (Suppl 2):B10–B21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Afdhal N, Zeuzem S, Kwo P, Chojkier M, Gitlin N, Puoti M, et al. Investigators ION. Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir for untreated HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:1889–1898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Afdhal N, Reddy KR, Nelson DR, Lawitz E, Gordon SC, Schiff E, et al. Investigators ION. Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir for previously treated HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:1483–1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kowdley KV, Gordon SC, Reddy KR, Rossaro L, Bernstein DE, Lawitz E, et al. Investigators ION. Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir for 8 or 12 weeks for chronic HCV without cirrhosis. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:1879–1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saab S, Park SH, Mizokami M, Omata M, Mangia A, Eggleton E, et al. Safety and efficacy of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir for the treatment of genotype 1 hepatitis C in subjects aged 65 years or older. Hepatology 2016; 63:1112–1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lawitz E, Mangia A, Wyles D, Rodriguez-Torres M, Hassanein T, Gordon SC, et al. Sofosbuvir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C infection. N Engl J Med 2013; 368:1878–1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feld JJ, Kowdley KV, Coakley E, Sigal S, Nelson DR, Crawford D, et al. Treatment of HCV with ABT-450/r-ombitasvir and dasabuvir with ribavirin. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:1594–1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zeuzem S, Jacobson IM, Baykal T, Marinho RT, Poordad F, Bourliere M, et al. Retreatment of HCV with ABT-450/r-ombitasvir and dasabuvir with ribavirin. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:1604–1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zeuzem S, Dusheiko GM, Salupere R, Mangia A, Flisiak R, Hyland RH, et al. Sofosbuvir and ribavirin in HCV genotypes 2 and 3. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:1993–2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jacobson IM, Gordon SC, Kowdley KV, Yoshida EM, Rodriguez-Torres M, Sulkowski MS, et al. Sofosbuvir for hepatitis C genotype 2 or 3 in patients without treatment options. N Engl J Med 2013; 368:1867–1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.AASLD/IDSA HCV Guidance Panel. Hepatitis C guidance: AASLD-IDSA recommendations for testing, managing, and treating adults infected with hepatitis C virus. Hepatology 2015; 62:932–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.