Abstract

Background and purpose — Outpatient arthroplasty has gained popularity in recent years; however, safety concerns still remain regarding complications and readmissions. In a prospective 2-center study we investigated early readmissions with overnight stay and complications following outpatient total hip (THA) and total knee arthroplasty (TKA) compared with a matched patient cohort with at least 1 postoperative night in hospital.

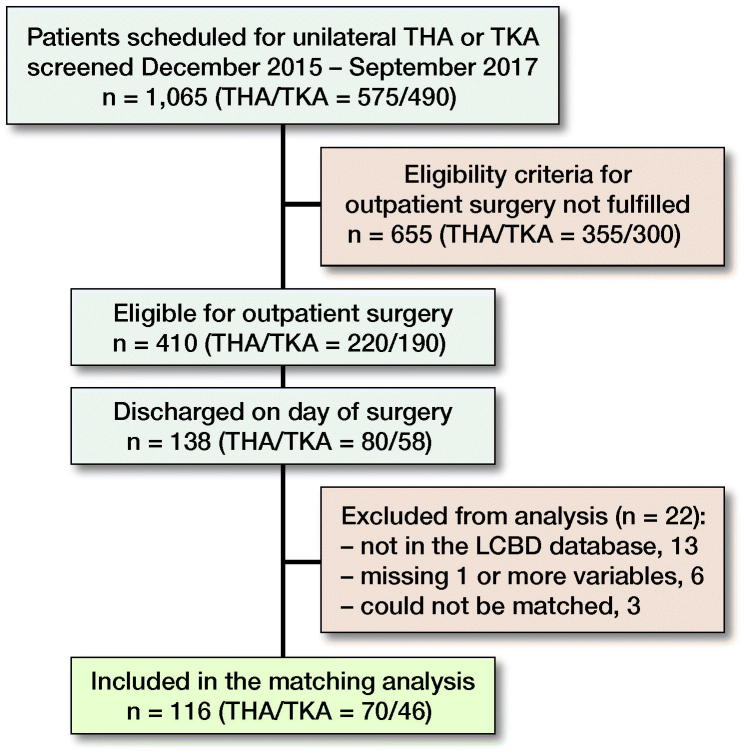

Patients and methods — All consecutive and unselected patients scheduled for THA or TKA at 2 participating hospitals were screened for potential day of surgery (DOS) discharge. Patients who fulfilled the DOS discharge criteria were discharged home. Patients discharged on DOS were matched on preoperative characteristics using propensity scores to patients operated at the same 2 departments prior to the beginning of this study with at least 1 overnight stay. All readmissions within 90 days were identified.

Results — It was possible to match 116 of 138 outpatients with 339 inpatient controls. Median LOS in the control cohort was 2 days (1–9). 7 (6%) outpatients and 13 (4%) inpatient controls were readmitted within 90 days. Readmissions occurred between postoperative day 2–48 and day 4–58 in the outpatient and control cohorts, respectively. Importantly, we found no readmissions within the first 48 hours and no readmissions were related to the DOS discharge.

Interpretation — Readmission rates in patients discharged on DOS may be similar to matched patients with at least 1 overnight stay. With the selection criteria used, there may be no safety signal associated with same-day discharge.

Outpatient arthroplasty has gained popularity in recent years as the fast-track concept has evolved with optimized logistics and perioperative treatment leading to reduced length of stay in hospital (LOS) worldwide (Kehlet 2013, Berend et al. 2018a). The popularity of outpatient arthroplasty is further fueled by increased focus on value-based treatments and cost-effectiveness, as outpatient procedures have been shown to have favorable financial benefits compared with in-hospital procedures (Lovald et al. 2014, Husted et al. 2018). Also, studies have shown that outpatient arthroplasty is feasible both for total hip arthroplasty (THA) and total knee arthroplasty (TKA), even in an unselected patient population (Goyal et al. 2016, Gromov et al. 2017). However, same-day discharge is reserved for a few selected patients and less then 1% of hip and knee arthroplasties in the United States are being performed as outpatient procedures (Basques et al. 2017, Courtney et al. 2017). While the majority of the studies have shown outpatient arthroplasty to be safe in a carefully selected patient population (Goyal et al. 2016, Courtney et al. 2017, Nelson et al. 2017), safety concerns still remain regarding complications and readmissions (Lovecchio et al. 2016, Courtney et al. 2018). Therefore, more studies are needed to investigate early complications following outpatient THA and TKA in a well-defined patient population with complete follow-up.

This prospective 2-center study investigated early readmissions requiring at least one night in hospital and types of complications following outpatient THA and TKA compared with a matched patient cohort treated within a standard fast-track setup requiring at least 1 night in hospital.

Patients and methods

All consecutive and unselected patients referred to the 2 participating departments and scheduled for unilateral THA or TKA were screened for participation in the study between December 2015 and September 2017. Outpatient surgery was defined as discharge to own home on day of surgery (DOS). Excluded were patients with ASA score > 2, patients with sleep apnea requiring treatment due to safety concerns if those patients were to be sent home with opioids, and patients operated as #3 in the operating room, as they were unlikely to be back on the ward in time to fulfill the functional discharge criteria on DOS. Finally, an adult had to be present at home for at least 24 hours following discharge in order for the patients to participate in outpatient surgery. Patients who fulfilled the DOS discharge criteria (Table 1, see Supplementary data) were discharged home. Detailed patient eligibility and fulfillment of discharge criteria for a part of this cohort has previously been published (Gromov et al. 2017). The prospective outpatient cohort thus consisted of patients discharged on DOS from the 2 departments during the study period.

Table 1.

Discharge criteria for discharge on DOS

| DOS discharge criteria |

| •< 500 ml intraoperative blood loss |

| •Back in ward before 15.00 hours |

| •Received instruction from physiotherapist and is safely mobilized |

| •No clinical symptoms of anemia |

| •Pain < 3 while resting, < 5 during mobilization |

| •Spontaneous micturition |

| •Postoperative radiographs performed and approved |

| •Relatives or friends with patient for initial 24 postoperative hours |

| •Motivated and accepts same-day discharge |

| •Can be discharged before 20.00 hours |

| •Fulfillment of functional discharge criteria (below) |

| Functional discharge criteria |

| •Able to get dressed independently |

| •Able to get in and out of bed |

| •Able to sit and rise from a chair/toilet |

| •Independent in personal care |

| •Mobilized with walker/crutches |

| •Able to walk > 70 m with walker/crutches |

The in-patient control cohort consisted of propensity score matched TKA (n = 134) and THA (n = 205 patients operated at the same 2 departments from January 2013 to November 2015 with at least 1 overnight stay—thus prior to introduction of outpatient THA and TKA surgery). All surgeries were performed in a standardized fast-track setup (Husted 2012) by surgeons specialized in THA and TKA surgery. The standard surgical protocol for both THA and TKA included spinal anesthesia, standardized fluid management, use of preoperative intravenous tranexamic acid (TXA), preoperative single-shot high-dose methylprednisolone, and absence of drains. Mechanical thromboprophylaxis and extended oral thromboprophylaxis were not used. All THAs were performed using a standard posterolateral approach. All TKAs were performed with a standard medial parapatellar approach without the use of tourniquet with application of local infiltration analgesia (LIA). Rivaroxaban was used as oral thromboprophylaxis starting 6 to 8 hours postoperatively and continuing daily until discharge if LOS < 5 days. Patients discharged on DOS received oral thromboprophylaxis for 2 days.

The patients were transferred from the postoperative recovery unit to the ward after a few hours, where immediate mobilization was attempted allowing full weight-bearing. Physiotherapy was started on the day of surgery and continued until discharge. After the patients were back in the ward, the nurse and the physiotherapist screened them for fulfillment of discharge criteria (discharge criteria for DOS discharge consisted of functional criteria that applied to all patients during the entire period as well as additional criteria for DOS discharge (Table 1, See supplementary data). All patients were discharged to their own homes. The treatment of all patients from 2013 and throughout the study was standardized at both departments and was the same for all patients—both patients participating in outpatient surgery and those not participating.

Both hospitals are reporting to the Lundbeck Foundation Centre for Fasttrack Hip and Knee Replacement Database (LCDB) (Jørgensen and Kehlet 2013b). All data on patient characteristics and comorbidities were thus prospectively recorded in the LCDB.

Using the patients’ unique social security number (Central Office of Civil Registration), we obtained information on postoperative LOS and 90-day readmissions and mortality from the Danish National Patient Registry (Andersen et al. 1999). As reporting to the Danish National Patient Registry is mandatory for hospitals to receive reimbursement, complete follow-up is assured. All patients with LOS > 4 days had their medical records examined to determine the reason for prolonged LOS. All unplanned admissions with overnight stay following discharge within 90 days postoperatively were evaluated using discharge or patient records and included as readmissions if related to index surgery. Reasons and timing for readmission were recorded.

Statistics

The propensity score (PS) was calculated using a logistic regression model. Covariates entered in the model were: age, sex, BMI, hospital, procedure, living situation, use of walking aids, smoking, alcohol use > 2 units/day (1 unit = 12 g of alcohol), pharmacologically treated cardiovascular disease, pharmacologically treated pulmonary disease (PD), Type II diabetes (DM), use of anticoagulants, pharmacologically treated psychiatric disease, previous venous thromboembolism (VTE), previous stroke, family history with VTE, and hypertension. As no patients in the outpatient cohort had Type 1 diabetes or preoperative anemia, patients with these 2 comorbidities were excluded from the control cohort. A 3:1 greedy nearest neighbor matching algorithm was used, excluding both cases and controls outside the area of common support. In 3 cases (3%), only 1 acceptable match was found and in 3 cases (3%) only 2 acceptable matches were found. For evaluation of successful matching we calculated the standardized differences.

Comparison of the outpatient and historical cohorts was done using the Mantel–Haenszel common odds ratio for weighted related data with a p-value of < 0.05 considered significant. Confidence intervals (CI) were all calculated as 95% CI.

Ethics, registration, funding, and potential conflict of interest

Permission to store and review patient data without prior informed consent was obtained from the Danish Data protection Agency (RH-2017-132) and the Danish National Board of Health (3-3013-56/2/EMJO). LCBD is registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01515670) as an ongoing study registry on preoperative patient characteristics and postoperative morbidity. This study was supported by a research grant from Zimmer Biomet and the Lundbeck Foundation, which did not participate in the investigation, data analysis or data interpretation.Authors declare no conflict of interest related to this study.

Results

1,065 patients were screened for eligibility during the study period, 410 patients were eligible for outpatient surgery, and 138 patients were discharged on DOS. 13 patients were not registered in the LCBD, 6 patients were missing 1 or several variables for matching, and 3 patients could not be matched, leaving 116 patients in the outpatient cohort for matching analysis (Figure). The control cohort consisted of 339 patients matched on the available comorbidities. Median LOS in the control cohort was 2 days (1–9). 4 patients in the control cohort had a LOS > 4 days (Table 3, see Supplementary data). 7 (6%, CI 3–12) outpatients and 13 (4%, CI 2–6) inpatient controls were readmitted within 90 days (OR 1.6, CI 0.7–4), respectively (Tables 4 and 5, see Supplementary data). Suspicion of deep venous thrombosis was the most common reason for readmission in both groups: 29% and 38% in the outpatient and control cohort respectively. Readmissions occurred between postoperative day 2 and 48 and day 4 and 58 in the outpatient and control group respectively (Tables 4 and 5, see Supplementary data). Of the 22 patients discharged on DOS who were excluded from analysis, 1 was readmitted due to dislocation of the operated hip on postoperative day 72.

Patient inclusions and exclusions

Discussion

In this prospective 2-center cohort study with a matched control cohort, we found that 6% outpatients and 4% inpatient controls were readmitted within 90 days following THA and TKA. No patient was readmitted within 48 hours after surgery.

Previous studies with complete follow-up in a similar setup have reported 90 days readmission rates of between 9% and 15% (Husted et al. 2010, Jørgensen and Kehlet 2013b). As patients in our study were selected for outpatient surgery and thus healthier compared with the average patient population, lower readmission rates are expected. Readmission rates found in our study are higher compared with some readmission rates previously published following outpatient THA and TKA from the United States, as a recent review by Hoffmann et al. (2018) reported only 2% 90-day readmission rates with similar low readmission rates reported by several other studies (Goyal et al. 2016, Basques et al. 2017, Berend et al. 2018b). Contrary to this, other studies from the United States have reported similar or even higher readmission rates following outpatient THA and TKA compared with our study: Springer et al. (2017) and Richards et al. (2018) reported 30-day readmission rates of 8%, while Berger et al. (2005) reported a 6% readmission rate within 90 days. The discrepancy in readmission rates following outpatient arthroplasty highlights variation in patient cohorts, definitions of readmission, follow-up method, and definitions of outpatient surgery (Saleh et al. 2019). When comparing outcomes and safety aspects between studies describing outpatient surgery, it is important to be aware of the definition of outpatient surgery itself as some studies use < 24 hour stay as the definition, while others —like this study, define outpatient surgery as DOS discharge (Vehmeijer et al. 2018). It could be argued that we should have used all hospital contacts instead of only readmissions with overnight stay in hospital as a study outcome. However, while this is of economic and logistical interest when evaluating the potential benefits of DOS discharge, in our opinion increases in planned hospital visits or readmissions not requiring overnight stay in hospital are of less relevance when discussing potential safety issues. Our finding that suspicion of deep venous thrombosis, ruled out by ultrasound, was the main reason for readmission is in accordance with previous studies (Husted et al. 2010), and may explain the higher readmission rates in the current study compared with some other studies, as visits to the emergency department with an overnight stay for diagnostics may not always be considered a readmission (Saleh et al. 2019), and may be diagnosed in the primary sector depending on the local logistical setup. Further on, as per department policy, we encourage all patients to contact the department in case of problems, which leads to potential readmissions that also would have been treated in the primary sector in a different setup. Finally, discharge location plays a role when comparing readmission. All patients in our study were discharged to their own home without any additional care, which might explain increased readmission rates compared with studies where patients are discharged to nursing care facilities or similar.

Timing of readmission is of specific interest for outpatient arthroplasty. A main safety consideration following DOS discharge is potential serious complications that are better treated during hospital admission, and potentially fatal if occurring at the patient’s own home such as thromboembolic events and pulmonary embolism, myocardial infection, and stroke (Jørgensen and Kehlet 2016, Petersen et al. 2018). This was highlighted by Parvizi et al. (2001), who warned against early discharge from the hospital while pointing out that the majority of serious complications occurred in the early postoperative period within 4 days, while the patients are still in hospital. This has since been disputed, as studies have shown fast-track THA and TKA with a mean LOS of 1–2 days to be safe and with very low rates of thromboembolic events (Jørgensen and Kehlet 2013b, Petersen et al. 2018). A possible explanation for reduced complication rates in a fast-track setup is early mobilization, which reduces the risk for TE events even with short TE prophylaxis during hospital stay only (Jørgensen et al. 2013a). No complications in our study occurred within the first postoperative 48 hours, and the complications that did occur would most likely have resulted in readmissions even if the patients had a minimum of 1 overnight stay. We thus believe that the risk of serious complications in the early postoperative period is very low for patients with no or few systemic comorbidities that are deemed eligible for outpatient surgery. This is supported by Jørgensen and Kehlet. (2016), who showed that only 11% of all early (< 1 week) TE embolic events occurred in patients without pre-, peri-, or postoperative disposition, meaning that 89% of early TE events occurred in patients who would not be eligible for outpatient surgery.

2 readmissions in the outpatient cohort were due to periprosthetic fracture after a fall. It is possible to speculate that such a complication could potentially be avoided if the patients were kept in hospital longer for better mobilization and achievement of steady gait. However, fractures due to a fall occurred both during admission and after discharge in the control cohort, thus we do not believe that such complications can be prevented by a longer readmission, as they are related to patient characteristics rather that short LOS (Jørgensen and Kehlet 2013a).

2 readmissions in the outpatient cohort in our study were due to urinary retention on PO day 2 and 7. However, both patients had spontaneous urination prior to discharge (as required by discharge criteria); therefore those readmissions would most likely not be avoided even if the patients had a minimum of 1 overnight stay. Consequently, we believe that readmissions in the outpatient cohort were not related to the early DOS discharge.

The low number of patients discharged on DOS is the main limitation of this study, thus making it difficult to draw definite conclusions on safety aspects for outpatient surgery. Our eligibility criteria were very broad, thus eligible patients who were not discharged on the DOS most likely differed from the patients who were discharged on DOS in a variety of parameters. To account for those potential differences we used the propensity score matching to match outpatients to a similar patient group (Table 2) from a retrospective cohort. As mentioned above, serious complications that are better handled if occurring in hospital compared with patients’ own homes are the main safety concerns of outpatient surgery. However, such complications (pulmonary embolism, myocardial infection, and stroke) are extremely rare (< 0.1%) even in an unselected THA and TKA population (Jørgensen and Kehlet 2016, Petersen et al. 2018), and presumably even more rare in a healthier selected population of patients deemed eligible for outpatient surgery (Jørgensen and Kehlet 2016). Thus, very large cohorts of patients discharged on DOS are required to make definite statements on safety aspects of outpatient surgery and an RCT on safety aspects of outpatient surgery would not be possible. Therefore we believe that continuous monitoring of complications following outpatient surgery in prospective cohort studies may be the optimal approach.

Table 2.

Preoperative characteristics of the total cohort of outpatients and the matched cohorts of outpatients and non-outpatients. Frequency (%) unless otherwise specified

| Characteristic | PS-matched outpatients n = 116 | PS-matched non-outpatients n = 339 | STDa | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 61 | (11) | 62 | (10.4) | 0.09 |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 28 | (5) | 28 | (5) | 0.01 |

| Hospital | 0.2 | ||||

| A | 76 | (66) | 219 | (65) | |

| B | 40 | (35) | 120 | (35) | |

| Procedure | 0.0 | ||||

| THA | 70 | (60) | 205 | (61) | |

| TKA | 46 | (40) | 134 | (40) | |

| Sex | 0.05 | ||||

| Female | 47 | (41) | 147 | (43) | |

| Male | 69 | (60) | 192 | (57) | |

| Social situation | 0.02 | ||||

| Living with others | 102 | (88) | 300 | (89) | |

| Living alone | 14 | (12) | 39 | (12) | |

| Use of walking aid | 0.0 | ||||

| Yes | 7 | (6) | 20 | (94) | |

| No | 109 | (94) | 319 | (6) | |

| Smoking | 0.06 | ||||

| Yes | 23 | (20) | 78 | (23) | |

| No | 93 | (80) | 261 | (77) | |

| Alcohol > 2 units daily | 0.02 | ||||

| Yes | 16 | (14) | 44 | (13) | |

| No | 100 | (87) | 295 | (87) | |

| Preoperative anemia | |||||

| Yes | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| No | 116 | (100) | 339 | (100) | |

| Pharmacologically treated psychiatric disorder | 0.01 | ||||

| Yes | 8 | (7) | 22 | (94) | |

| No | 108 | (93) | 317 | (7) | |

| Pharmacologically treated pulmonary disease | 0.05 | ||||

| Yes | 12 | (10) | 29 | (9) | |

| No | 104 | (90) | 310 | (91) | |

| Pharmacologically treated cardiac disease | 0.01 | ||||

| Yes | 8 | (7) | 22 | (7) | |

| No | 108 | (93) | 317 | (93) | |

| Type-2 diabetes | 0.06 | ||||

| Yes | 1 | (1) | 1 | (0) | |

| No | 115 | (99) | 338 | (100) | |

| Any anticoagulants | 0.03 | ||||

| Yes | 6 | (5) | 21 | (6) | |

| No | 110 | (95) | 318 | (94) | |

| Previous venous thromboembolic event | 0.03 | ||||

| Yes | 5 | (4) | 12 | (4) | |

| No | 111 | (96) | 327 | (97) | |

| Previous stroke | 0.03 | ||||

| Yes | 9 | (8) | 30 | (9) | |

| No | 107 | (92) | 309 | (91) | |

| Family with venous thromboembolic event | 0.03 | ||||

| Yes | 8 | (7) | 20 | (6) | |

| No | 108 | (93) | 319 | (94) | |

| Hypertension | 0.03 | ||||

| Yes | 36 | (31) | 111 | (33) | |

| No | 80 | (69) | 228 | (67) | |

STD: standardized difference; a STD of > 0.1 was chosen as indicative of imbalance.

PS: propensity score. SD: standard deviation. BMI: body mass index. THA: total hip arthroplasty TKA: total knee arthroplasty.

In summary, we found comparable readmission rates in patients discharged on DOS and matched patients with at least 1 overnight stay within a fast-track setup. Most importantly, we did not find any readmissions within the first 48 hours and found no readmissions to be related to the DOS discharge.

Supplementary data

Tables 1, 3, 4, and 5 are available as supplementary data in the online version of this article, http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1080/17453674.2019.1577049

Table 3.

Reason for LOS (length of stay) > 4 days for matched patients in the control cohort

| Patient no. | Reason for LOS > 4 days |

|---|---|

| 1 | No specific reason identified |

| 2 | Chest pain on postop day 1 All tests normal |

| 3 | Subtrochanteric fracture on postop day 2 |

| 4 | Paralytic ileus on postop day 3 conservatively treated |

Table 4.

Readmission within 90 days following surgery for outpatient patients (n = 116)

| Complication type | Specific complication (n = 7) | Postoperative day no. for readmission | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infection (n = 1) | Periprosthetic infection | Treated with debridement and irrigation | 48 |

| Thromboembolism (n = 2) | Clinical suspicion of DVT | Ruled out by ultrasound | 6, 9 |

| Fracture (n = 2) | Periprosthetic fracture due to fall | Revised with revision THA | 6 |

| Periprosthetic fracture without trauma | ORIF with cables | 25 | |

| Urologic (n = 2) | Post renal kidney failure due to urinary retention | Treated with urinary catheter and fluids | 2 |

| Urinary retention | Treated with urinary catheter | 7 |

Table 5.

Readmission within 90 days following surgery for matched patients (n = 339)

| Complication type | Specific complication (n = 13) | Postoperative day no. for readmission | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infection (n = 3) | Periprosthetic infections (2) | Treated with debridement and irrigation | 14, 58 |

| Suspicion of superficial wound infection (1) | Treated with antibiotics | 17 | |

| Thromboembolism (n = 6) | Clinical suspicion of DVT (5) | Ruled out by ultrasound | 4, 7, 8, 14, 26 |

| Clinical suspicion of DVT, confirmed by ultrasound (1) | Treated with anticoagulants | 5 | |

| Cardiac (n = 1) | Dyspnea, all tests normal. Hemoglobin measured at 9.4 g/dl | Treated with oral iron | 9 |

| Gastrointestinal (n = 1) | Abdominal pain due to Ogilvie syndrome | 7 | |

| Fracture (n = 1) | Fall and contralateral femoral neck fracture | 51 | |

| Pulmonary (n = 1) | Acute COPD exacerbation | 47 |

COPD = Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

KG, HH, and HK planned the study. KG, PKA, PR, AT, and HH were responsible for the logistical setup and collected the data. CCJ, PBP, and HK analyzed the data. KG wrote the first draft of the paper. All authors revised the paper.

Acta thanks Maziar Mohaddes and Stephan Vehmeijer for help with peer review of this study.

References

- Andersen T F, Madsen M, Jørgensen J, Mellemkjoer L, Olsen J H. The Danish National Hospital Register: a valuable source of data for modern health sciences. Dan Med Bull 1999; 46(3): 263–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basques B A, Tetreault M W, Della Valle C J. Same-day discharge compared with inpatient hospitalization following hip and knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg 2017; 99(23): 1969–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berend K R, Lombardi A V, Berend M E, Adams J B, Morris M J. The outpatient total hip arthroplasty. Bone Joint J 2018a; 100-B(1 Suppl. A): 31–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berend M E, Lackey W G, Carter J L. Outpatient-focused joint arthroplasty is the future: The Midwest Center for Joint Replacement experience. J Arthroplasty 2018b; 33(6): 1647–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger R A, Sanders S, Gerlinger T, Della Valle C, Jacobs J J, Rosenberg A G. Outpatient total knee arthroplasty with a minimally invasive technique. J Arthroplasty 2005; 20(7, Suppl. 3): 33–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtney P M, Boniello A J, Berger R A. Complications following outpatient total joint arthroplasty: an analysis of a national database. J Arthroplasty 2017; 32(5): 1426–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtney P M, Froimson M I, Meneghini R M, Lee G-C, Della Valle C J. Can total knee arthroplasty be performed safely as an outpatient in the Medicare population? J Arthroplasty 2018; 33(7): S28–S31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyal N, Chen A F, Padgett S E, Tan T L, Kheir M M, Hopper R H, Hamilton W G, Hozack W J. Otto Aufranc Award: A multicenter, randomized study of outpatient versus inpatient total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2016; 475(2): 364–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gromov K, Kjaersgaard-Andersen P, Revald P, Kehlet H, Husted H. Feasibility of outpatient total hip and knee arthroplasty in unselected patients: a prospective 2-center study. Acta Orthop 2017; 88(5): 516–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann J D, Kusnezov N A, Dunn J C, Zarkadis N J, Goodman G P, Berger R A. The shift to same-day outpatient joint arthroplasty: a systematic review. J Arthroplasty 2018; 33(4): 1265–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husted H. Fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty: clinical and organizational aspects. Acta Orthop 2012; 83(Suppl. 316): 1–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husted H, Otte K S, Kristensen B B, Orsnes T, Kehlet H. Readmissions after fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2010; 130(9): 1185–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husted H, Kristensen B B, Andreasen S E, Skovgaard Nielsen C, Troelsen A, Gromov K. Time-driven activity-based cost of outpatient total hip and knee arthroplasty in different set-ups. Acta Orthop 2018; 89(5) 515–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen C C, Kehlet H. Fall-related admissions after fast-track total hip and knee arthroplasty: cause of concern or consequence of success? Clin Interv Aging 2013a; 8: 1569–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen C C, Kehlet H, Lundbeck Foundation Centre for Fast-track Hip and Knee Replacement Collaborative Group . Role of patient characteristics for fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty. Br J Anaesth 2013b; 110(6): 972–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen C C, Kehlet H, Lundbeck Foundation Centre for Fast-track Hip and Knee replacement collaborative group . Early thromboembolic events ≤ 1week after fast-track total hip and knee arthroplasty. Thromb Res 2016; 138: 37–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen C C, Jacobsen M K, Soeballe K, Hansen T B, Husted H, Kjaersgaard-Andersen P, Hansen L T, Laursen MB, Kehlet H. Thromboprophylaxis only during hospitalisation in fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty, a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2013; 3(12): e003965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehlet H. Fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty. Lancet 2013; 381(9878): 1600–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovald S T, Ong K L, Malkani A L, Lau E C, Schmier J K, Kurtz S M, Manley M T. Complications, mortality, and costs for outpatient and short-stay total knee arthroplasty patients in comparison to standard-stay patients. J Arthroplasty 2014; 29(3): 510–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovecchio F, Alvi H, Sahota S, Beal M, Manning D. Is outpatient arthroplasty as safe as fast-track inpatient arthroplasty? A propensity score matched analysis. J Arthroplasty 2016; 31(9): 197–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson S J, Webb M L, Lukasiewicz A M, Varthi A G, Samuel A M, Grauer J N. Is outpatient total hip arthroplasty safe? J Arthroplasty 2017; 32(5): 1439–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parvizi J, Sullivan T A, Trousdale R T, Lewallen D G. Thirty-day mortality after total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2001; 83-A(8): 1157–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen P B, Kehlet H, Jørgensen C C, Lundbeck Foundation Centre for Fast-track Hip and Knee Replacement Collaborative Group . Myocardial infarction following fast-track total hip and knee arthroplasty; incidence, time course and risk factors: a prospective cohort study of 24,862 procedures. Acta Orthop 2018; 89(6): 603–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards M, Alyousif H, Kim J-K, Poitras S, Penning J, Beaulé P E. An evaluation of the safety and effectiveness of total hip arthroplasty as an outpatient procedure: a matched-cohort analysis. J Arthroplasty. 2018; 33(10): 3206–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleh A, Faour M, Sultan A A, Brigati D P, Molloy R M, Mont M A. Emergency department visits within thirty days of discharge after primary total hip arthroplasty: a hidden quality measure. J Arthroplasty 2019; 34(1): 20–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer B D, Odum S M, Vegari D N, Mokris J G, Beaver W B. Impact of inpatient versus outpatient total joint arthroplasty on 30-day hospital readmission rates and unplanned episodes of care. Orthop Clin North Am 2017; 48(1): 15–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vehmeijer S B W, Husted H, Kehlet H. Outpatient total hip and knee arthroplasty. Acta Orthop 2018; 89(2): 141–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.