Abstract

Background and purpose — Femoral neck preserving hip replacement has been suggested to improve clinical results and facilitate late revision. We compared the 2-year outcome and radiostereometric pattern of femoral head migration between the Collum Femoris Preserving (CFP) stem and the Corail stem.

Patients and methods — 83 patients were randomized to either a CFP stem or a Corail stem. All patients received the same cup. At 2 years clinical outcomes were assessed using validated scoring systems and plain radiographs. 2-year migration was determined using radiostereometric analysis.

Results — At 2 years the clinical outcomes (Oxford Hip Score, Harris Hip Score, SF-36, EQ5D-VAS, satisfaction VAS, and pain VAS) were similar between the 2 groups. The radiographic measurements showed that the femoral neck was resected around 1 cm more proximally with use of CFP stems (p < 0.001). The proximal–distal and medial–lateral migration of the femoral head center was similar. The Corail stem showed increased posterior displacement after 1 year, but no difference was found between the absolute translations in the anterior–posterior direction (p = 0.2). 2 CFP stems were revised due to loosening within the first 2 years. None of the Corail stems was revised.

Interpretation — In the 2-year perspective clinical outcomes suggested no obvious advantages with use of the CFP stem. The magnitude of the early stem migration was similar, but the pattern of migration differed. The early revisions in the CFP are a cause of concern.

The stems used most frequently in primary hip replacement surgery have a length of about 13–15 cm. Removal of such a stem, if uncemented and ingrown, might become difficult should any late infection or instability problems occur.

The concept of femoral neck preserving hip replacement with the use of a short stem was introduced for young and active patients, who, partly due to their longer life expectancy, may require multiple revisions, which would be facilitated due to the higher femoral neck osteotomy. The more proximal physiological load distribution can be expected to decrease proximal bone resorption, which could facilitate fixation of a revision stem. Preservation of the femoral neck will also imply that the native anteversion of the femur is easier to preserve during the operation, which could result in improved function and overall clinical results.

The Collum Femoris Preserving (CFP) stem was introduced by Pipino and Calderale in the 1980s and has been evaluated in multiple studies. So far the clinical documentation of the CFP stem indicates a stable fixation and good 2–9-year results (Röhrl et al. 2006, Briem et al. 2011, Nowak et al. 2011, Kress et al. 2012, Lazarinis et al. 2013, Hutt et al. 2014, Li et al. 2014, You et al. 2015). To our knowledge there are no published randomized studies comparing the CFP with a well-documented standard stem.

We speculated that a more conservative resection of the femoral neck could lead to better clinical outcomes. Therefore, we compared the neck-preserving CFP stem with the conventional Corail stem in a randomized controlled trial. Our primary aim was to compare the clinical outcomes at 2 years, using Oxford Hip Score between the 2 groups. Second, we used radiostereometric analysis (RSA) to compare fixation between the 2 stem designs.

Patients and methods

Study design and population

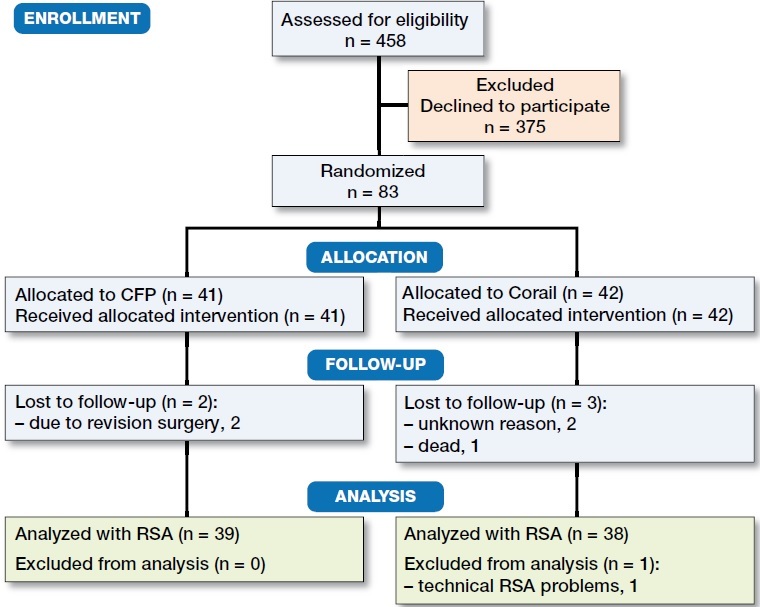

We conducted a randomized controlled trial at the Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Mölndal. We included patients with a painful hip and radiological evidence of osteoarthritis who were eligible for hip arthroplasty. Other inclusion criteria were hip anatomy suitable for both designs according to preoperative planning and age between 35 and 75 years. Exclusion criteria were previous treatment with cortisone and low expected activity rate due to other diseases such as generalized joint disease. 458 patients visiting our outpatient clinic between May 2012 and May 2014 fulfilled the primary inclusion criteria. Of these, 83 patients (83 hips) with radiographic appearance of the proximal femur judged suitable for uncemented fixation accepted to participate. Patients were randomly assigned to either a CFP or Corail stem with the use of envelopes. 41 hips received a CFP and 42 a Corail stem (Figure 1). All hips were operated with a Delta-TT cup (Lima, Italy). The CFP stem (LINK, Germany) is available in 6 sizes with 2 different curvatures, 2 CCD angles (117 or 126 degrees) and with or without a calcium phosphate coating. In our study only coated stems were used. The Corail stem (DePuy Synthes, USA) is a conventional, uncemented, hydroxyapatite-coated collarless straight stem. It is available in 11 sizes. Since 2009 it has been the most frequently used uncemented stem in Sweden for primary THR.

Figure 1.

Consort flow diagram

The mean age of the 83 patients (53 men) at operation was 58 years (35–73). 76 patients had primary osteoarthritis, 5 secondary osteoarthritis due to dysplasia, 1 idiopathic femoral head necrosis, and 1 femoral head necrosis after trauma. 14 different surgeons performed the operations. They were all performed or supervised by a surgeon with long experience of uncemented THR. All patients were operated using a direct lateral approach with the patient in the lateral decubitus position. Full weight-bearing was encouraged directly postoperatively.

2 patients were lost to follow-up. 1 patient died before the 2nd year follow-up due to brain metastases. 2 patients in the CFP group underwent stem revision due to loosening between the 1 and 2 years’ follow up. The cup shell was left in place in both cases. All other patients were followed for at least 2 years.

Clinical outcome measures

The Oxford Hip Score and Harris Hip Score were conducted preoperatively and after 12 and 24 months of follow-up. The University of Los Angeles California activity scale (UCLA) was assessed preoperatively, after 3 months, and after 12 and 24 months. Quality of life was determined by the SF-36 (containing a physical health component summery score [SF-36 p] and a mental health component summery score [SF-36 m]), EQ-5D-VAS, a visual analogue scale (VAS) for pain, and postoperatively satisfaction with the outcome of surgery. These scores were determined preoperatively, and after 3, 12, and 24 months. The EQ-5D was scored according to the UK tariffs. The UCLA questionnaire was scored using the English scoring tool.

Radiography

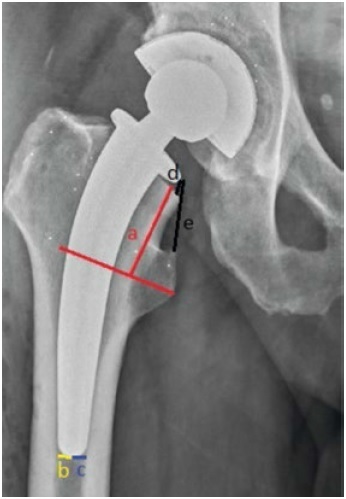

Postoperatively and after 12 and 24 months, standard pelvic, anteroposterior (AP), and lateral radiographs were obtained. We determined the length of the remaining femoral neck, the neck resorption ratio, and the position of the tip of the stem in the femoral canal. The remaining neck was measured from the middle of the lesser trochanter to the proximal calcar. Neck resorption and the position of the tip were expressed in ratios (Figure 2). Radiolucent lines around the stem were determined according to Gruen. Radiographs were examined by 2 of the authors (LK and GP), with an agreement of 0.74 (Cohen’s kappa).

Figure 2.

Method of measuring the remaining neck (a) and the position of tip of the stem. We measured the distance between the tip of the stem and the inner cortex and calculated the ratio between these distances. Ratio between lateral and medial distance is b/c.The neck resorption ratio (NRR) is calculated by dividing the distance between the medial tip of the collar and the medial apex of the remaining neck (d) by the length of a straight line traced from the medial tip of the collar to the apex of the lesser trochanter (e).

Radiostereometric analysis (RSA)

During surgery, 7–9 0.8 mm tantalum markers were placed in the proximal femoral bone. Translations of the femoral head represented migration of the stem. Uniplanar radiographs were exposed at a median of 2 days (0–5) after surgery, using 2 detectors with an angle of about 40° between the X-ray tubes and with use of cage 77 (RSA Biomedical, Umeå, Sweden). Follow-up investigations were performed 3, 6, 12, and 24 months after surgery. To determine the precision of the RSA measurements we conducted double examinations postoperatively of 76 hips and calculated the 99% prediction interval of the precision based on the presumption of zero motion between repeated exposures. The medial–lateral, proximal–distal, and anterior–posterior translation of the femoral head center could be measured with a precision of 0.18, 0.18, and 0.45 mm respectively. This tolerance interval corresponded to the 99% confidence interval of the error around a supposed mean 0 value of the error (no systematic bias between double examinations). The analysis of movement of the stem was performed using the UMRSA analysis software 6.0 (RSA Biomedical, Umeå, Sweden). The median values and ranges of the mean error of rigid body fitting and condition number are presented in Table 1. The center of the femoral head was used to measure translations of the stem; hence stem rotation could not be analyzed. RSA analysis of stem migration up to 2 years was performed on 39 CFP stems and 38 Corail stems due to insufficient number of stable bone markers in 1 patient.

Table 1.

Mean error of rigid body fitting and condition number

| CFP |

Corail |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| median | range | median | range | |

| Mean error of rigid | ||||

| body fitting (mm) | 0.2 | 0.04–0.4 | 0.2 | 0.04–0.3 |

| Condition number | 30 | 17–151 | 33 | 18–93 |

Statistics

Our primary outcome was the Oxford Hip Score. The secondary outcome was distal stem migration measured with RSA. A power analysis, assuming normally distributed data, performed before the study started, indicated that 30 patients in each group would give us the possibility to detect a difference of 4 points on the OHS between the groups with a power of 80%. A corresponding analysis of distal migration of the femoral head center indicated that we could detect a group difference of 0.4 mm based on a presumed standard deviation of 0.5 mm in each group. All outcomes were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics 23 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). Most of the clinical parameters recorded did not follow a normal distribution. Therefore we used the Mann–Whitney test to compare the clinical outcomes between the Corail and CFP group. Comparisons were done on preoperative data and results at 3 months and 2 years. Comparison of RSA data was performed at 2 years with use of a Mann–Whitney test. In addition, the results of repeated ANOVA test on 37 CFP and 35 Corail stems with complete RSA data on all 4 follow-up occasions are presented. P-values < 0.05 were regarded to represent a statistically significant difference.

Ethics, registration, funding, and potential conflicts of interests

The study followed the Helsinki declaration (Ethical approval 243-12, Regional ethical committee Gothenburg, Sweden). Informed consent was obtained from all patients. The study was registered in ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02983526) and followed the CONSORT Statement. Institutional support was received from LINK, Germany, LIMA, Italy, Ingabritt and Arne Lundbergs Research Foundation, and LUA/ALF, Sweden. No conflicts of interest were declared.

Results

Clinical outcomes

The characteristics of the groups were nearly similar at baseline (Table 2). No statistically or clinically important differences were found between the 2 groups after 3 months, except from estimation of general health, where patients were asked to value their general health at the moment of questioning in comparison with the last 12 months of their life. At 3 months, 35 of the patients with a Corail stem valued their health to be better compared with 26 in the CFP group (p = 0.04). This result in favor of the Corail stem had disappeared at the 2-year follow-up. At this time the clinical outcomes had improved compared with the preoperative measurements, being similar between the 2 groups (Table 3).

Table 2.

Patient characteristics and preoperative clinical variables

| CFP (n = 41) |

Corail (n = 42) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | median (range) | n | median (range) | |

| Age | 41 | 61 (35–73) | 42 | 58 (43–73) |

| Harris Hip Scorea | 23 | 53 (22–74) | 22 | 52 (32–83) |

| Oxford Hip Score | 39 | 21 (8–45) | 41 | 20 (2–35) |

| SF-36 p | 37 | 26 (14–49) | 38 | 26 (13–52) |

| SF-36 m | 37 | 57 (24–71) | 38 | 50 (2–71) |

| EQ-5D | 38 | 0.5 (0–0.8) | 40 | 0.2 (–0.6 to 0.8) |

| EQ-VAS | 36 | 60 (10–95) | 40 | 60 (5–95) |

| Pain VAS | 38 | 70 (20–93) | 40 | 64 (5–85) |

| UCLA score | 38 | 4 (2–10) | 41 | 4 (2–10) |

| General healthb | 38 | 40 | ||

| better | 2 | 0 | ||

| the same | 14 | 12 | ||

| worse | 22 | 28 | ||

| missing answers | 3 | 2 | ||

High number of missing Harris Hip Score was caused by logistic problems (poor communication to study secretaries and failures to scan these forms).

Number of patients that valued their general health as better/the same/worse than the last 12 months and missing answers.

Table 3.

Clinical outcomes after 2 years

| CFP (n = 39) |

Corail (n = 39) |

p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | median (range) | n | median (range) | ||

| Harris Hip score | 35 | 100 (44–100) | 38 | 100 (48–100) | 0.7 |

| Oxford Hip score | 38 | 44 (19–48) | 38 | 45 (15–48) | 0.9 |

| SF-36 p | 38 | 48 (13–57) | 38 | 43 (18–63) | 0.9 |

| SF-36 m | 38 | 55 (17–66) | 38 | 54 (18–63) | 0.7 |

| EQ-5D | 38 | 0.8 (–0.2 to 1) | 38 | 0.8 (–0.4 to 1) | 0.2 |

| EQ-VAS | 38 | 85 (20–100) | 38 | 85 (20–100) | 0.8 |

| Pain VAS | 38 | 7 (0–73) | 39 | 2 (0–81) | 0.4 |

| Satisfaction VAS | 38 | 95 (9–100) | 39 | 97 (0–100) | 0.7 |

| UCLA-activity score | 38 | 6 (2–10 | 39 | 6 (2–10) | 0.6 |

| General healtha | 38 | 39 | 0.2 | ||

| better | 18 | 15 | |||

| the same | 15 | 14 | |||

| worse | 5 | 10 | |||

| missing answers | 1 | 0 | |||

General health, see Table 2

Radiographic outcomes

The postoperative radiographs showed a mean preservation of the proximal femur of 37 mm (SD 5.4) in patients with a CFP stem, compared with 28 mm (SD 5.4) in the Corail group (p < 0.001). At the 2-year follow-up 39 CFP and 39 Corail stems were radiographically analyzed. The mean neck resorption ratio at 2 years was 0.00 in the Corail group and 0.04 (SD 0.1) in the CFP group with 7 patients who showed neck resorption (p = 0.003) compared with none in the Corail group. The median lateral–medial ratio of the position of the tip of the stem after 2 years was 1 (0.4–2.0) in the CFP group and 0.7 (0.4–1.5) in the Corail group (p < 0.001), meaning that the tip of the Corail stems was placed more laterally. The median anterior–-posterior ratio was 1.1 (0.6–3.0) after 2 years in the CFP group and 1.3 (0.5–3.3) in the Corail group, meaning both of the stems were placed more posteriorly, without any statistically significant difference between them (p = 0.4). 9 Corail stems showed radiolucent lines on plain radiographs at 2-year follow-up, most of them less than 15% of the total stem circumference facing bone in Gruen regions 1, 7, 8, 9, 10, and 14. In 2 stems the radiolucent lines had an extension between 15% and 30%. 3 CFP stems showed radiolucency around the stem. In 1 stem it occupied 5% of the stem–bone interface, localized to Gruen region 1. In 2 hips the lines had an extension of 20% and 25% corresponding to regions 8, 9, 10, and 12. Median radiolucency in the CFP and Corail groups was 0% for both stem designs and on both the AP (p = 0.05) and lateral (p = 0.5) views.

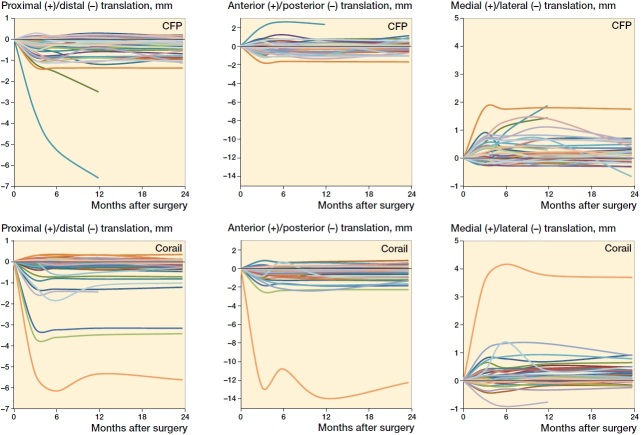

RSA results

After 2 years the median proximal–distal translation of the center of the femoral head was similar in both groups (Table 4). The femoral head center showed a mean medial translation in both groups during the first 2 years (Figure 3). The Corail stem showed an increased mean posterior displacement compared with the CFP stem (p = 0.02). However, if the direction of the movement was disregarded, the median absolute movement in the anterior–posterior direction was similar between groups (p = 0.2). This indicates that the center of the femoral head of the CFP stem moved both posteriorly and anteriorly, whereas there was mainly a tendency to posterior displacement in the Corail group. Further studies of all follow-up occasions (repeated measure ANOVA, 37 CFP and 35 Corail stems) showed no statistically significant differences between the groups, either when signed (p ≥ 0.08) or absolute (p ≥ 0.2) migration data were studied.

Table 4.

Median and mean translation (mm) of the center of the femoral head at 2 years

| Translations | CFP (n = 39) |

Corail (n = 38) |

p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| median | range | mean (95%CI) | median | range | mean (95%CI) | ||

| Medial (+) / lateral (–) | 0.1 | –0.6 to 2 | 0.2 (0.1 to 0.3) | 0.1 | –0.2 to 4 | 0.3 (0.1 to 0.5) | 0.7 |

| Proximal (+) / distal (–) | –0.2 | –1 to 0.2 | –0.3 (–0.4 to –0.2) | –0.1 | –6 to 0.3 | –0.5 (–0.9 to –0.1) | 0.7 |

| Anterior (+) / posterior (–) | –0.1 | –2 to 1 | –0.1 (–0.2 to 0.2) | –0.2 | –12 to 0.9 | –0.7 (–1 to 0) | 0.02 |

Figure 3.

Migration of all individual prosthesis along the 3 different axes (mm).

We also examined the number of stems that showed RSA migration above the individual 99% detection limit and in any of the 3 directions (medial–lateral, proximal–distal and/or anterior–posterior). Between the postoperative radiostereometric examination and the examination at 2 years movements above the detection limit were observed in 31 CFP stems and in 30 Corail stems. 9 CFP stems and 9 Corail stems showed detectable movement between the first and second year. Thus, 30 CFP and 29 Corail stems had stabilized within 1 year.

Revisions and complications

1 patient who received a Corail stem had an intraoperative fissure, which was treated with cerclage wires. 2 CFP stems were revised due to loosening at 15 and 21 months. All cultures sampled during the 2 revisions were negative and repeated tests of C-reactive protein were normal. 1 of these 2 patients died 23 months after the operation due to cancer. There were no dislocations or infections.

Discussion

Previous reports of the CFP stem showed good short- and mid-term results (Röhrl et al. 2006, Briem et al. 2011, Nowak et al. 2011, Kress et al. 2012, Lazarinis et al. 2013, Hutt et al. 2014, Li et al. 2014, You et al. 2015). Whether the CFP stem improves the outcome in terms of hip function and patient satisfaction compared with a conventional stem has not been studied previously. Despite a rather extensive clinical evaluation we were not able to demonstrate any benefits for the CFP stem in the 2-year perspective. Overall there are very few randomized studies of short stems. Tomaszewski et al. (2013) compared the clinical outcomes of patients operated with an ultra-short stem (Proxima) with a control group who received a classic design. He concluded that patients in the Proxima group had a better clinical status and a greater quality of life. In another study of the same short stem design Salemyr et al. (2015) did not find any difference in the clinical results after 2 years. Hube et al. (2004) conducted a randomized clinical trial in which they compared the Mayo short stem with the ABG stem in 93 patients. The follow-up was short, only 3 months, when they observed higher HHS scores with use of the Mayo stem.

Our study has several limitations. The follow-up is short, which means that late-occurring problems usually related to wear, loosening, and periprosthetic fractures cannot be accounted for. The 2 patients with early loosening are a cause of concern but still too few for any certain conclusions. In 1 of these cases a generalized malignant disease was subsequently diagnosed, which could have had influenced the healing potential of the bone immediately after the index operation when the malignancy was unknown. Another limitation is the participation of 11 surgeons, some of whom operated on only a few patients, even if this was done with an experienced colleague as assistant. Corail stems supplemented with tantalum markers or model-based RSA were not available to us, which restricted the radiostereometric evaluation to measurement of femoral head translations. This was the original way to measure stem translations (Mjöberg 1986). Even if lack of stem markers means that rotations not could be studied we think that the information obtained is sufficiently good to measure the most important parameter, namely subsidence (Kärrholm et al. 1994). Femoral head translations can only serve to assume the direction of any stem rotations. Distal and medial translation of the head center can be interpreted as varus tilt, and posterior translation as retroversion or posterior tilt of the stem. Because of different stem shape and neck length, the axis of rotation might vary depending on stem design, which will make it still more difficult to speculate in what way head translations mirror the direction and magnitude of rotation. Finally, some patients did not complete their clinical questionnaires resulting in 5% missing answers, with 1 patient having 10% missing answers. Strengths of our study are the randomized design, inclusion of comparatively many patients, a wide spectrum of clinical outcome parameters used, and measurements of stem migration with high resolution.

Previous studies of the CFP stem showed an improvement of the HHS to at least 82 points (You et al. 2015) but mostly to 90 or more (Röhrl et al. 2006, Briem et al. 2011, Nowak et al. 2011, Kress et al. 2012, Lazarinis et al. 2013, Hutt et al. 2014, Li et al. 2014). In our study the HHS in the CFP patients improved to a median of 93 at the 2-year follow-up. We do not think that the minor differences observed between the 2 groups studied at the 3 months’ follow-up had any clinical relevance.

Previous studies evaluating the CFP stem indicate a stable fixation and good short and intermediate term results on durability (Röhrl et al. 2006, Briem et al. 2011, Nowak et al. 2011, Kress et al. 2012, Lazarinis et al. 2013, Li et al. 2014, You et al. 2015). Hutt et al. (2014) reported a survivorship of 100% after a mean follow-up of 9 years. Survivorship of the CFP stem in our study was 95% after 2 years. As mentioned above, comorbidity might have contributed to 1 of our 2 revisions, perhaps causing inferior bone quality and/or compromised healing potential. Concerning the 2nd revision we think that this stem was slightly undersized. In the annual report of the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register 2015, the 5-year survival rate of the CFP stem was 97%, which was significantly lower than observed in the control group (99%; contemporary uncemented stems of standerd length) (SHAR 2015).

We found radiolucent lines in the proximal Gruen zones in several patients in both groups, which corresponds to previous observations (Röhrl et al. 2006, Nowak et al. 2011, You et al. 2015). The relative amount of neck resorption we observed after 2 years was higher than reported by Pipino and Molfetta (1993). In their study 1% of the 200 observed stems showed neck resorption after a follow-up of 1 to 6 years.

Using the RSA techniques, we found similar absolute translations along any of the axes between the groups. However, we found a statistically significant difference between the mean anterior–posterior motion. We noticed that the center of the femoral head in the Corail group moved posteriorly in most cases, while the center of the femoral head in the CFP group moved both posteriorly and anteriorly. We assume that this translation is a result of the rotation of the stem into retro- or anteversion. The 2 other RSA studies performed on the CFP stem both showed retroversion of the stem using the mean translation and rotation (Röhrl et al. 2006, Lazarinis et al. 2013). The range of the data published by Lazarinis et al. (2013) (–0.26 to 0.55 mm) suggest that the CFP stem moved both into retro- and in anteversion. The increased retroversion observed by us in the Corail group could be an effect of a shorter remaining femoral neck and the shape differences of the 2 stems studied. So far we do not know whether these different patterns of anterior–posterior femoral head translations have any clinical relevance.

2 years after surgery, the mean proximal–distal translation of the femoral head was –0.3 mm in the CFP group. The previous RSA studies of the CFP stem measured smaller mean subsidence (–0.05 and –0.13 mm) (Röhrl et al. 2006, Lazarinis et al. 2013). In these studies subsidence was measured at the center of the stem, which means that the measured values will be less influenced by any varus angulation of the stem. In the study by Röhrl et al. (2006) patients were advised to only partially weight bear during the first 6 weeks, which also could have had an influence.

The migration of the Corail stem along the 3 different axes reported in our study is in line with an RSA study regarding the Corail stem (Campbell et al. 2011). Further follow-up and probably studies of more cases are necessary to determine the limit of acceptable subsidence of the CFP stem not to be associated with an increased risk of clinical loosening. It might be that the presence of continuous migration and especially subsidence past 1 year is a more negative prognostic sign than the magnitude of migration up to 6 months or 1 year, provided that the stem stabilizes within this time period. Von Schewelov et al. (2012) observed distal migration in the majority of cases with maximum values up to 21 mm of the Corail stem inserted in patients with femoral neck fracture. All stems were stabilized during the 2nd year of observation, which could support this theory. Similar observations and use of continuous subsidence as a prognostic bad sign are also supported by previous observations of various uncemented stems followed for short periods with RSA (Luites et al. 2006, Ström et al. 2007, Baad-Hansen et al. 2011). We also observed a continuous subsidence in our 2 revised cases, but still the knowledge in this field is too limited to allow for any certain conclusions. Long-term studies of larger patient populations will be necessary to map out in more detail the prognostic value of early RSA recordings of uncemented stems.

The CFP stem has been on the market for about 20 years and has been used all over the world. Extensive evaluation shows no difference in clinical results, but we found 2 fixation failures in the CFP group within the first 2 years. Therefore we think that the CFP stem should be used with caution. Careful preoperative planning might be still more important for these types of stems to select the correct size and shape and avoid under-sizing. Whether the use of CFP stem at index surgery gives an advantage during revision surgery is yet to be investigated.

Acknowledgments.

LJK: Collection of clinical data, RSA measurements, statistical analysis, writing manuscript. GP: Data collection, follow-up, study design, review of manuscript. MM: Follow up, review of manuscript. JK: Study design, review of manuscript, statistical and methodological aspects.

The authors would like to thank Bita Shareghi for her help on the RSA measurements.

Acta thanks Lene Bergendal Solberg and Marc J Nieuwenhuijse for help with peer review of this study.

References

- Baad-Hansen T, Kold S, Olsen N, Christensen F, Soballe K. Excessive distal migration of fiber-mesh coated femoral stems. Acta Orthop 2011; 82(3): 308–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briem D, Schneider M, Bogner N, Botha N, Gebauer M, Gehrke T, Schwantes B. Mid-term results of 155 patients treated with a Collum Femoris Preserving (CFP) short stem prosthesis. Int Orthop 2011; 35(5): 655–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell D, Mercer G, Nilsson K G, Wells V, Field J R, Callary S A. Early migration characteristics of a hydroxyapatite-coated femoral stem: an RSA study. Int Orthop 2011; 35(4): 483–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hube R, Zaage M, Hein W, Reichel H. [Early functional results with the Mayo hip, a short stem system with metaphyseal–intertrochanteric fixation]. Der Orthopade 2004; 33(11): 1249–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutt J, Harb Z, Gill I, Kashif F, Miller J, Dodd M. Ten year results of the Collum Femoris Preserving total hip replacement: a prospective cohort study of seventy five patients. Int Orthop 2014; 38(5): 917–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kärrholm J, Borssen B, Lowenhielm G, Snorrason F. Does early micromotion of femoral stem prostheses matter? 4-7-year stereoradiographic follow-up of 84 cemented prostheses. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1994; 76(6): 912–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kress A M, Schmidt R, Nowak T E, Nowak M, Haeberle L, Forst R, Mueller L A. Stress-related femoral cortical and cancellous bone density loss after Collum Femoris Preserving uncemented total hip arthroplasty: a prospective 7-year follow-up with quantitative computed tomography. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2012; 132(8): 1111–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarinis S, Mattsson P, Milbrink J, Mallmin H, Hailer N P. A prospective cohort study on the short Collum Femoris-Preserving (CFP) stem using RSA and DXA: primary stability but no prevention of proximal bone loss in 27 patients followed for 2 years. Acta Orthop 2013; 84(1): 32–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Hu Y, Xie J. Analysis of the complications of the Collum Femoris Preserving (CFP) prostheses. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc 2014; 48(6): 623–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luites J W, Spruit M, Hellemondt G G, Horstmann W G, Valstar E R. Failure of the uncoated titanium ProxiLock femoral hip prosthesis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2006; 448: 79–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mjöberg B. Loosening of the cemented hip prosthesis” the importance of heat injury. Acta Orthop 1986; (Suppl 221): 1–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak M, Nowak T E, Schmidt R, Forst R, Kress A M, Mueller L A. Prospective study of a cementless total hip arthroplasty with a Collum Femoris Preserving stem and a trabeculae oriented pressfit cup: minimun 6-year follow-up. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2011; 131(4): 549–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pipino F, Molfetta L. Femoral neck preservation in total hip replacement. Ital J Orthop Traumatol 1993; 19(1): 5–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Röhrl S M, Li M G, Pedersen E, Ullmark G, Nivbrant B. Migration pattern of a short femoral neck preserving stem. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2006; 448:73–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salemyr M, Muren O, Ahl T, Boden H, Eisler T, Stark A, Skoldenberg O. Lower periprosthetic bone loss and good fixation of an ultra-short stem compared to a conventional stem in uncemented total hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop 2015; 86(6): 659–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHAR Swedish Hip Artroplasty Register annual report 2015, page 56 ISBN 978-91-980507-9-0. https://shpr.registercentrum.se/shar-in-english/annual-reports-from-the-swedish-hip-arthroplasty-register/p/rkeyyeElz

- Ström H, Nilsson O, Milbrink J, Mallmin H, Larsson S. The effect of early weight bearing on migration pattern of the uncemented CLS stem in total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2007; 22(8): 1122–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomaszewski W, Kotela I, Kawik L, Bednarenko M, Lorkowski J, Kotela A. Quality of life of patients in the evaluation of outcomes of short stem hip arthroplasty for hip osteoarthritis. Orthop Traumatol Rehabil 2013; 15(5): 439–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Schewelov T, Ahlborg H, Sanzen L, Besjakov J, Carlsson A. Fixation of the fully hydroxyapatite-coated Corail stem implanted due to femoral neck fracture: 38 patients followed for 2 years with RSA and DEXA. Acta Orthop 2012; 83(2): 153–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You R J, Zheng W Z, Chen K, Lv H S, Huang D F, Xiao Y Z, Yang D Y, Su Z Q. Long-term effectiveness of total hip replacement with the Collum Femoris Preserving prosthesis. Cell Biochem Biophys 2015; 72(1): 43–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]