Abstract

Background

Anti–tumour necrosis factor (TNF) agents are effective in treating people with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), but are associated with (dose‐dependent) adverse effects and high costs. To prevent overtreatment, several trials have assessed the effectiveness of down‐titration compared with continuation of the standard dose. This is an update of a Cochrane Review published in 2014.

Objectives

To evaluate the benefits and harms of down‐titration (dose reduction, discontinuation, or disease activity‐guided dose tapering) of anti‐TNF agents on disease activity, functioning, costs, safety, and radiographic damage compared with usual care in people with RA and low disease activity.

Search methods

We searched MEDLINE, Embase, Web of Science and CENTRAL (29 March 2018) and four trial registries (11 April 2018) together with reference checking, citation searching, and contact with study authors to identify additional studies. We screened conference proceedings (American College of Rheumatology and European League Against Rheumatism 2005‐2017).

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and controlled clinical trials (CCTs) comparing down‐titration (dose reduction, discontinuation, disease activity–guided dose tapering) of anti‐TNF agents (adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, etanercept, golimumab, infliximab) to usual care/no down‐titration in people with RA and low disease activity.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard Cochrane methodology.

Main results

One previously included trial was excluded retrospectively in this update because it was not an RCT/CCT. We included eight additional trials, for a total of 14 studies (13 RCTs and one CCT, 3315 participants in total) reporting anti‐TNF down‐titration. Six studies (1148 participants) reported anti‐TNF dose reduction compared with anti‐TNF continuation. Eight studies (2111 participants) reported anti‐TNF discontinuation compared with anti‐TNF continuation (three studies assessed both anti‐TNF discontinuation and dose reduction), and three studies assessed disease activity–guided anti‐TNF dose tapering (365 participants). These studies included data on all anti‐TNF agents, but primarily adalimumab and etanercept. Thirteen studies were available in full text, one was available as abstract. We assessed the included studies generally at low to moderate risk of bias; our main concerns were bias due to open‐label treatment and unblinded outcome assessment. Clinical heterogeneity between the trials was high. The included studies were performed at clinical centres around the world and included people with early as well as established RA, the majority of whom were female with mean ages between 47 and 60. Study durations ranged from 6 months to 3.5 years.

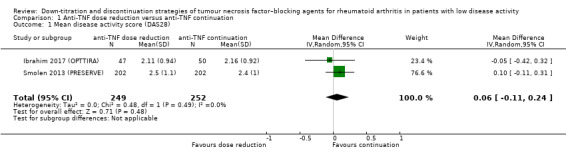

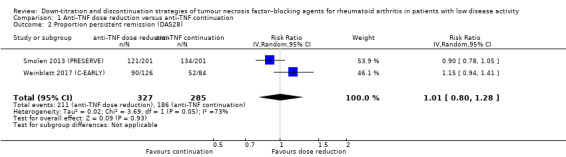

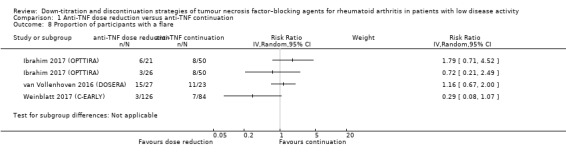

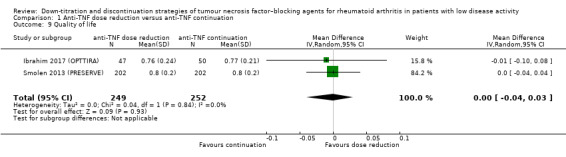

We found that anti‐TNF dose reduction leads to little or no difference in mean disease activity score (DAS28) after 26 to 52 weeks (high‐certainty evidence, mean difference (MD) 0.06, 95% confidence interval (CI) −0.11 to 0.24, absolute risk difference (ARD) 1%) compared with continuation. Also, anti‐TNF dose reduction does not result in an important deterioration in function after 26 to 52 weeks (Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index (HAQ‐DI)) (high‐certainty evidence, MD 0.09, 95% CI 0.00 to 0.19, ARD 3%). Next to this, anti‐TNF dose reduction may slightly reduce the proportion of participants switched to another biologic (low‐certainty evidence), but probably slightly increases the proportion of participants with minimal radiographic progression after 52 weeks (moderate‐certainty evidence, risk ratio (RR) 1.22, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.95, ARD 2% higher). Anti‐TNF dose reduction may cause little or no difference in serious adverse events, withdrawals due to adverse events and proportion of participants with persistent remission (low‐certainty evidence).

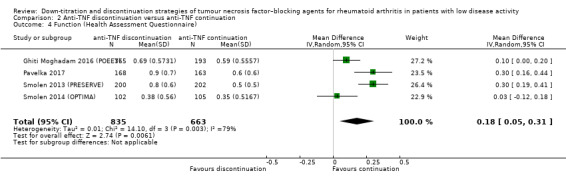

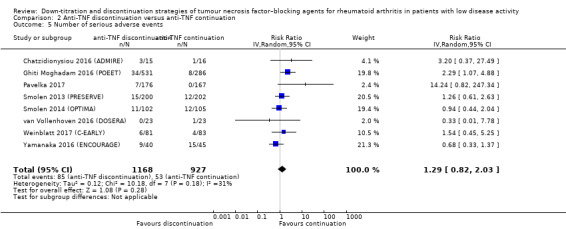

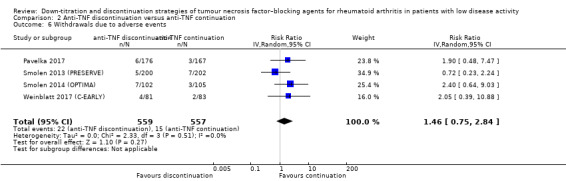

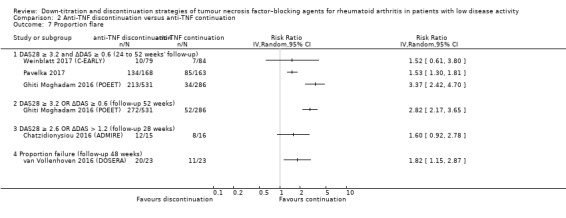

Results show that anti‐TNF discontinuation probably slightly increases the mean disease activity score (DAS28) after 28 to 52 weeks (moderate‐certainty evidence, MD 0.96, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.25, ARD 14%), and that the RR of persistent remission lies between 0.16 and 0.77 (low‐certainty evidence). Anti‐TNF discontinuation increases the proportion participants with minimal radiographic progression after 52 weeks (high‐certainty evidence, RR 1.69, 95% CI 1.10 to 2.59, ARD 7%) and may lead to a slight deterioration in function (HAQ‐DI) (low‐certainty evidence). It is uncertain whether anti‐TNF discontinuation influences the number of serious adverse events (due to very low‐certainty evidence) and the number of withdrawals due to adverse events after 28 to 52 weeks probably increases slightly (moderate‐certainty evidence, RR 1.46, 95% CI 0.75 to 2.84, ARD 1% higher).

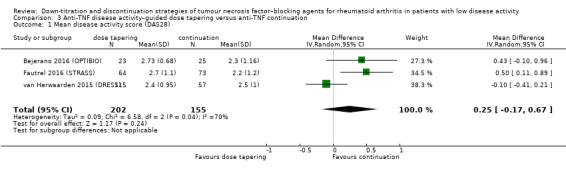

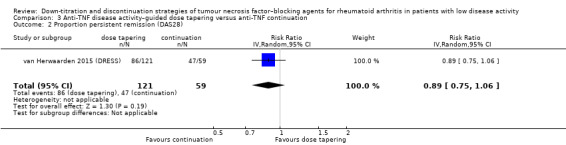

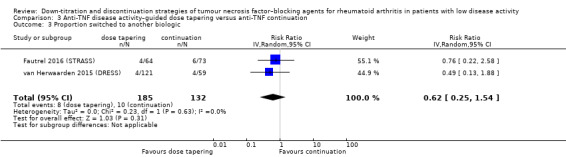

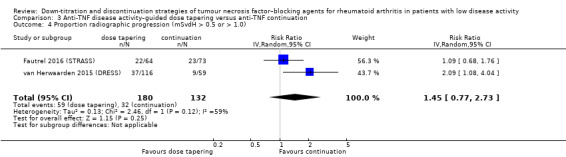

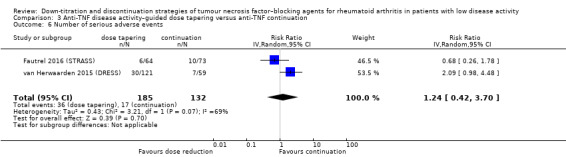

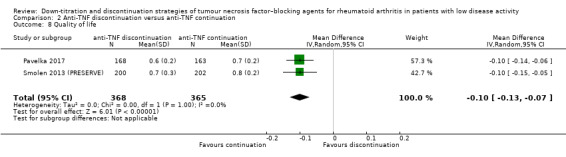

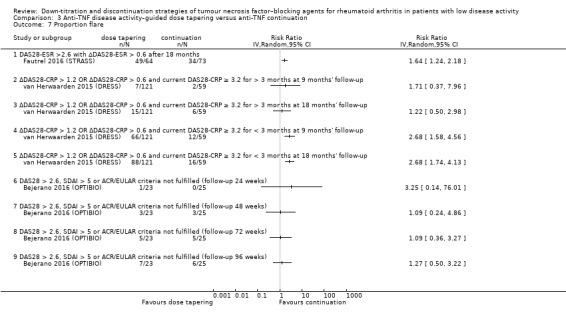

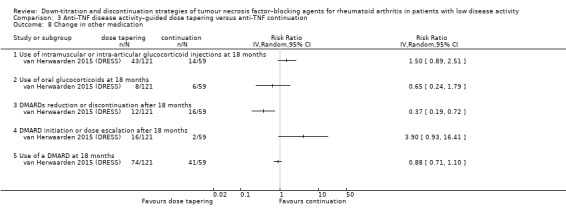

Anti‐TNF disease activity–guided dose tapering may result in little or no difference in mean disease activity score (DAS28) after 72 to 78 weeks (low‐certainty evidence). Furthermore, anti‐TNF disease activity–guided dose tapering results in little or no difference in the proportion of participants with persistent remission after 18 months (high‐certainty evidence, RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.06, ARD −9%) and may result in little or no difference in switching to another biologic (low‐certainty evidence). Anti‐TNF disease activity–guided dose tapering may slightly increase proportion of participants with minimal radiographic progression (low‐certainty evidence) and probably leads to a slight deterioration of function after 18 months (moderate‐certainty evidence, MD 0.2 higher, 0.02 lower to 0.42 higher, ARD 7% higher), It is uncertain whether anti‐TNF disease activity‐guided dose tapering influences the number of serious adverse events due to very low‐certainty evidence.

Authors' conclusions

We found that fixed‐dose reduction of anti‐TNF, after at least three to 12 months of low disease activity, is comparable to continuation of the standard dose regarding disease activity and function, and may be comparable with regards to the proportion of participants with persistent remission. Discontinuation (also without disease activity–guided adaptation) of anti‐TNF is probably inferior to continuation of treatment with respect to disease activity, the proportion of participants with persistent remission, function, and minimal radiographic damage. Disease activity–guided dose tapering of anti‐TNF is comparable to continuation of treatment with respect to the proportion of participants with persistent remission and may be comparable regarding disease activity.

Caveats of this review are that available data are mainly limited to etanercept and adalimumab, the heterogeneity between studies, and the use of superiority instead of non‐inferiority designs.

Future research should focus on the anti‐TNF agents infliximab and golimumab; assessment of disease activity, function, and radiographic outcomes after longer follow‐up; and assessment of long‐term safety, cost‐effectiveness, and predictors for successful down‐titration. Also, use of a validated flare criterion, non‐inferiority designs, and disease activity–guided tapering instead of fixed‐dose reduction or discontinuation would allow researchers to better interpret study findings and generalise to clinical practice.

Plain language summary

Lowering the dose of or stopping anti‐tumour necrosis factor drugs in people with rheumatoid arthritis who are doing well (low disease activity)

We conducted an updated review of studies in which treatment with anti‐tumour necrosis factor (anti‐TNF) drugs (adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, etanercept, golimumab, and infliximab) was lowered or stopped in people with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) who use anti‐TNF drugs and are doing well (low disease activity). Our systematic search up to March 2018 identified 14 studies (3315 participants). The included studies were performed at clinical centres around the world and included people with early as well as established RA, the majority of whom were female with mean ages varying between 47 and 60. Study durations ranged from 6 months to 3.5 years.

What is rheumatoid arthritis? What is stopping or lowering the dose of anti‐TNF drugs?

When you have RA, your immune system, which normally fights infection, attacks the lining of your joints. This makes your joints swollen, stiff, and painful. There is no cure for RA, so treatments aim to relieve pain and stiffness, improve ability to move, and prevent damage to the joints.

Anti‐TNF agents are biological drugs for RA. They lessen complaints by reducing inflammation in the joints, and they reduce radiographic joint damage. Reducing or stopping anti‐TNF treatment when disease activity is low might reduce dose‐dependent side effects (mainly infections) and costs.

Key results

Data were available for all anti‐TNF agents, but mostly for adalimumab and etanercept.

Disease activity

‐ People who lowered the dose of anti‐TNF showed little or no increase in disease activity compared with people who continued anti‐TNF (high‐certainty evidence).

‐ People who stopped anti‐TNF had a 0.96 unit increase in disease activity on a scale from 0.9 to 8 compared with people who continued anti‐TNF (absolute difference 14%, moderate‐certainty evidence).

‐ People who gradually lowered the dose of anti‐TNF showed little or no increase in disease activity compared with people who continued anti‐TNF (low‐certainty evidence).

Persistent remission

‐ There was little or no difference in the number of people who had persistent remission between those who lowered the dose of anti‐TNF compared with continuation of anti‐TNF (low‐certainty evidence).

‐ Data on how stopping anti‐TNF affects persistent remission were not pooled because results were not similar across studies (low‐certainty evidence). The absolute difference varied between 15% and 68% fewer people that remained in remission when stopping anti‐TNF compared to continuation of anti‐TNF.

‐ There was little or no difference in the number of people who had persistent remission between those who gradually lowered the dose of anti‐TNF compared with continuation of anti‐TNF (high‐certainty evidence).

X‐ray progression

‐ 24 more people per 1000 had a greater than 0.5 point progression of joint damage after a year when lowering the dose of anti‐TNF (scale 0 to 448) (absolute difference 2%, moderate‐certainty evidence).

‐ 73 more people per 1000 who stopped anti‐TNF had a greater than 0.5 point progression of joint damage after a year than people who continued anti‐TNF (absolute difference 7%, high‐certainty evidence).

‐ 110 more people per 1000 had greater than 0.5 or greater than 1.0 point progression of joint damage after 1.5 years when gradually lowering the dose of anti‐TNF (low‐certainty evidence).

Function

‐ People who lowered the dose of anti‐TNF had a 0.09 unit worsening of function (scale 0 to 3) compared with people who continued anti‐TNF (absolute difference 3%, high‐certainty evidence).

‐ People stopping anti‐TNF had a 0.18 unit worsening of function compared with people who continued anti‐TNF (absolute difference 6%, low‐certainty evidence).

‐ People gradually lowering the dose of anti‐TNF had a 0.2 unit worsening in function compared with people who continued anti‐TNF (absolute difference 7%, moderate‐certainty evidence).

Side effects

‐ There was little or no difference in number of serious adverse events in people lowering the dose of anti‐TNF compared to continuation anti‐TNF (low‐certainty evidence).

‐ It is uncertain whether gradually lowering the dose of or stopping anti‐TNF influences the number of serious adverse events (very low‐certainty evidence).

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Anti‐TNF dose reduction versus anti‐TNF continuation.

| Anti‐TNF dose reduction compared to anti‐TNF continuation for rheumatoid arthritis in patients with low disease activity | |||||||

| Patient or population: people with rheumatoid arthritis with low disease activity using a standard dose of anti‐TNF agents Setting: clinical research centres Intervention: anti‐TNF dose reduction Comparison: anti‐TNF continuation | |||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | What happens | |

| Risk with anti‐TNF continuation | Risk with anti‐TNF dose reduction | ||||||

| Disease activity score Assessed with: DAS28 Scale from 0.9 to 8; higher scores indicate worse disease activity Follow‐up: range 26 weeks to 52 weeks | The mean disease activity score was 2.34 | MD 0.06 higher (0.11 lower to 0.24 higher) | ‐ | 501 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | Absolute risk difference: 1% higher (95% CI 2% lower to 3% higher) Relative percentage change: 2% higher (95% CI 5% lower to 10% higher) |

Anti‐TNF dose reduction results in little or no difference in disease activity score (DAS28). |

| Proportion of participants with persistent remission Assessed with: DAS28 < 2.6 (remission) Follow‐up: 52 weeks | 653 per 1000 | 659 per 1000 (522 to 835) | RR 1.01 (0.80 to 1.28) | 612 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 | Absolute risk difference: 1% higher (95% CI 13% lower to 18% higher) Relative percentage change: 1% higher (95% CI 20% lower to 28% higher) NNTB: not applicable (not statistically significant) |

Anti‐TNF dose reduction may result in little or no difference in the proportion of participants with persistent remission (DAS28 < 2.6). |

|

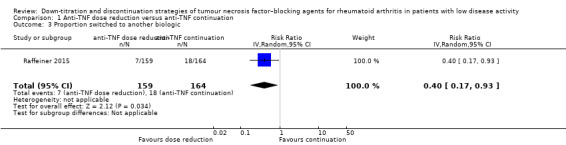

Proportion of participants switched to another biologic Mean follow‐up of 3.5 ± 1.5 years |

110 per 1000 | 44 per 1000 (19 to 102) | RR 0.40 (0.17 to 0.93) | 323 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 2 | Absolute risk difference: 7% lower (95% CI 9% lower to 1% lower) Relative percentage change: 60% (95% CI 83% lower to 7% lower) NNTB: 15 (95% CI 12 to 100) |

Anti‐TNF dose reduction may slightly reduce the proportion of participants switched to another biologic. |

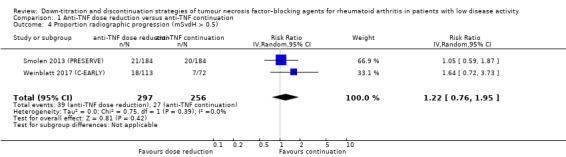

| Proportion of participants with minimal radiographic progression Assessed with: mSvdH score > 0.5 Follow‐up: 52 weeks | 105 per 1000 | 129 per 1000 (80 to 206) | RR 1.22 (0.76 to 1.95) | 553 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 3 | Absolute risk difference: 2% higher (95% CI 3% lower to 10% higher) Relative percentage change: 22% higher (95% CI 34% lower to 95% higher) NNTH: not applicable (not statistically significant) |

Anti‐TNF dose reduction probably slightly increases the proportion of participants with minimal radiographic progression (mSvdH > 0.5) . |

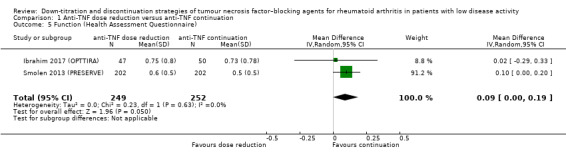

| Function Assessed with: Health Assessment Questionnaire Scale from 0 to 3; higher scores indicate worse function Follow‐up: range 26 weeks to 52 weeks | The mean function was 0.52 | MD 0.09 higher (0 to 0.19 higher) | ‐ | 501 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | Absolute risk difference: 3% higher (95% CI 0% higher to 6% higher) Relative percentage change: 15% higher (95% CI 0% higher to 31% higher) |

Anti‐TNF dose reduction does not result in an important deterioration in function. |

|

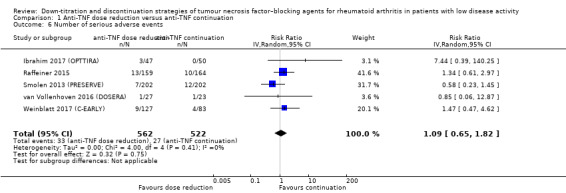

Number of serious adverse events Follow‐up: range 26 weeks to 52 weeks (mean follow‐up for Raffeiner 2015 3.5 ± 1.5 years) |

52 per 1000 | 56 per 1000 (34 to 94) | RR 1.09 (0.65 to 1.82) | 1084 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 3 4 | Absolute risk difference: 0% (95% CI 2% lower to 4% higher) Relative percentage change: 9% higher (95% CI 35% lower to 82% higher) NNTH: not applicable (not statistically significant) |

Anti‐TNF dose reduction may cause little or no difference in the number of serious adverse events.. |

|

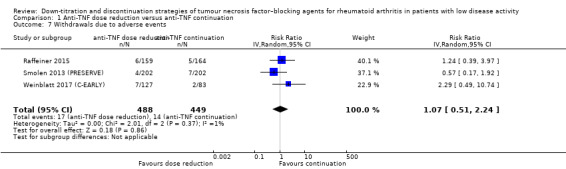

Withdrawals due to adverse events Follow‐up: 52 weeks (mean follow‐up for Raffeiner 2015 3.5 ± 1.5 years) |

31 per 1000 | 33 per 1000 (16 to 70) | RR 1.07 (0.51 to 2.24) | 937 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 3 4 | Absolute risk difference: 0% (95% CI 2% lower to 4% higher) Relative percentage change: 7% higher (95% CI 49% lower to 124% higher) NNTH: not applicable (not statistically significant) |

Anti‐TNF dose reduction may cause little or no difference in the number of withdrawals due to adverse events . |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; DAS28: disease activity score in 28 joints; MD: mean difference; mSvdH: modified Sharp van der Heijde; NNTB: number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome; NNTH: number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome; RCT: randomised controlled trial: RR: risk ratio; TNF: tumour necrosis factor | |||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | |||||||

1Downgraded two levels due to heterogeneity (I2=73%) 2Downgraded two levels due to concerns about study risk of bias (high risk of selection bias, performance bias, detection bias and other bias). 3Downgraded one level due to imprecision (insufficient sample size/low number of events). 4Downgraded one level due to concerns about study risk of bias (mainly due to high risk of attrition bias in Smolen 2013 (PRESERVE) and high risk of bias on several domains in Raffeiner 2015).

Summary of findings 2. Anti‐TNF discontinuation versus anti‐TNF continuation.

| Anti‐TNF discontinuation compared to anti‐TNF continuation for rheumatoid arthritis in patients with low disease activity | |||||||

| Patient or population: people with rheumatoid arthritis with low disease activity using a standard dose of anti‐TNF agents Setting: clinical research centres Intervention: anti‐TNF discontinuation Comparison: anti‐TNF continuation | |||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | What happens | |

| Risk with anti‐TNF continuation | Risk with anti‐TNF discontinuation | ||||||

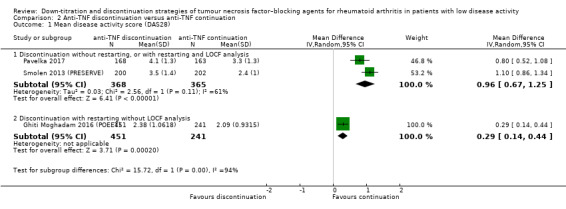

| Disease activity score ‐ assessed with: DAS28 Scale from: 0.9 to 8; higher scores indicate worse disease activity follow up: range 28 weeks to 52 weeks |

Discontinuation without restarting, or with restarting and LOCF analysis Mean disease activity score was 2.82 |

MD 0.96 higher (0.67 higher to 1.25 higher) | ‐ | 733 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | Absolute risk difference: 14% higher (95% CI 9% higher to 18% higher) Relative percentage change: 25% (95% CI 18% higher to 33% higher) |

Anti‐TNF discontinuation probably increases the disease activity score slightly |

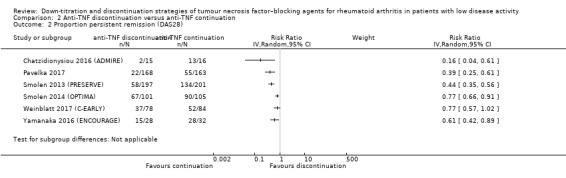

| Proportion of participants with persistent remission Assessed with: DAS28 < 2.6 (remission) Follow‐up: range 28 weeks to 52 weeks | RR values range from 0.16 to 0.77. Absolute risk differences range from 15% lower to 68% lower. | 1188 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 2 | Data not pooled due to heterogeneity. | Anti‐TNF discontinuation may reduce the proportion of participants with persistent remission | ||

| Proportion participants that switched to another biologic due to loss of response ‐ not measured | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No studies were found that evaluated the proportion of participants that switched to another biologic due to persistent loss of response. | |

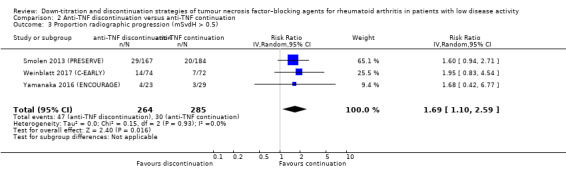

| Proportion participants with minimal radiographic progression Assessed with: mSvdH > 0.5 Follow‐up: mean 52 weeks | 105 per 1000 | 178 per 1000 (116 to 273) | RR 1.69 (1.10 to 2.59) | 549 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | Absolute risk difference: 7% higher (95% CI 1% higher to 17% higher) Relative percentage change: 69% higher (95% CI 10% higher to 159% higher) NNTH: 15 (95% CI 6 to 100) |

Anti‐TNF discontinuation increases the proportion participants with minimal radiographic progression > 0.5 mSvdH point. |

| Function Assessed with: Health Assessment Questionnaire Scale from 0 to 3; higher scores indicate worse functioning Follow‐up: range 28 weeks to 52 weeks | The mean function was 0.52 | MD 0.18 higher (0.05 higher to 0.31 higher) | ‐ | 1498 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 2 | Absolute risk difference: 6% higher (95% CI 2% higher to 17% higher) Relative percentage change: 26% higher (95% CI 7% higher to 44% higher) |

Anti‐TNF discontinuation may lead to a slight deterioration in function. |

|

Number of serious adverse events Follow‐up: range 28 weeks to 52 weeks |

57 per 1000 | 74 per 1000 (47 to 116) | RR 1.29 (0.82 to 2.03) | 2095 (8 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 3 4 | Absolute risk difference: 2% higher (95% CI 1% lower to 6% higher) Relative percentage change: 29% higher (95% CI 18% lower to 103% higher) NNTH: not applicable (not statistically significant) |

It is uncertain whether anti‐TNF discontinuation influences the number of serious adverse events because the certainty of the evidence is very low and because of imprecision. |

|

Withdrawals due to adverse events Follow‐up: range 28 weeks to 52 weeks |

27 per 1000 | 39 per 1000 (20 to 76) | RR 1.46 (0.75 to 2.84) | 1116 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 3 | Absolute risk difference: 1% higher (95% CI 1% lower to 5% higher) Relative percentage change: 46% (95% CI 25% lower to 184% higher) NNTH: not applicable (not statistically significant) |

Anti‐TNF discontinuation probably slightly increases the number of withdrawals due to adverse events. |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; DAS28: disease activity score in 28 joints; LOCF: last observation carried forward; MD: mean difference; mSvdH: modified Sharp van der Heijde; NNTH: number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome; RCT: randomised controlled trial: RR: risk ratio; TNF: tumour necrosis factor | |||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | |||||||

1Downgraded one level due to heterogeneity (I2=61% for disease activity score and I2=31% for number of serious adverse events). 2Downgraded two levels due to heterogeneity (I2=80% for proportion of participants with remission and I2=79% for function). 3Downgraded one level due to imprecision (low number of events). 4Downgraded one level due to concerns about study risk of bias (high risk of selection bias, detection bias, attrition bias and other bias).

Summary of findings 3. Anti‐TNF disease activity–guided dose tapering versus anti‐TNF continuation.

| Anti‐TNF disease activity–guided dose tapering compared to anti‐TNF continuation for rheumatoid arthritis in patients with low disease activity | |||||||

| Patient or population: people with rheumatoid arthritis with low disease activity using a standard dose of anti‐TNF agents Setting: clinical research centres Intervention: anti‐TNF disease activity–guided dose tapering Comparison: anti‐TNF continuation | |||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | What happens | |

| Risk with anti‐TNF continuation | Risk with anti‐TNF disease activity–guided dose tapering | ||||||

| Disease activity score Assessed with: DAS28 Scale from 0.9 to 8; higher scores indicate worse disease activity Follow‐up: range 72 weeks to 78 weeks | The mean disease activity score was 2.34 | MD 0.25 higher (0.17 lower to 0.67 higher) | ‐ | 357 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 | Absolute risk difference: 4% higher (95% CI 2% lower to 9% higher) Relative percentage change: 10% higher (95% CI 7% lower to 26% higher) |

Anti‐TNF disease activity–guided dose tapering may result in little or no difference in disease activity score. |

| Proportion of participants with persistent remission Assessed with: DAS28 < 2.6 (remission) Follow‐up: 18 months | 797 per 1000 | 709 per 1000 (597 to 844) | RR 0.89 (0.75 to 1.06) | 180 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | Absolute risk difference: 9% lower (95% CI 20% lower to 5% higher) Relative percentage change: 10% higher (95% CI 7% lower to 26% higher) NNTH: not applicable (not statistically significant) |

Anti‐TNF disease activity–guided dose tapering results in little or no difference in the proportion of participants with persistent remission. |

| Proportion of participants switched to another biologic due to loss of response Follow‐up: 18 months | 76 per 1000 | 47 per 1000 (19 to 117) | RR 0.62 (0.25 to 1.54) | 317 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 2 | Absolute risk difference: 3% lower (95% CI 6% lower to 4% higher) Relative percentage change: 38% higher (95% CI 75% lower to 54% higher) NNTH: not applicable (not statistically significant) |

Anti‐TNF disease activity–guided dose tapering may result in little or no difference in the proportion of participants that switch to another biologic. |

| Proportion of participants with minimal radiographic progression Assessed with: mSvdH score > 0.5 or > 1.0 Follow‐up: mean 18 months | 242 per 1000 | 352 per 1000 (187 to 662) | RR 1.45 (0.77 to 2.73) | 312 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 3 4 | Absolute risk difference: 11% higher (95% CI 6% lower to 42% higher) Relative percentage change: 45% higher (95% CI 23% lower to 173% higher) NNTH: not applicable (not statistically significant) |

Anti‐TNF disease activity–guided dose tapering may slightly increase the proportion of participants with minimal radiographic progression (mSvdH > 0.5 or > 1.0). |

| Function Assessed with: Health Assessment Questionnaire Scale from 0 to 3; higher scores indicate worse function Follow‐up: mean 18 months | The mean function was 0.4 | MD 0.2 higher (0.02 lower to 0.42 higher) | ‐ | 123 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 4 | Absolute risk difference: 7% higher (95% CI 1% lower to 14% higher) Relative percentage change: 33% higher (95% CI 3% lower to 70% higher) |

Anti‐TNF disease activity–guided dose tapering probably leads to a slight deterioration of function. |

|

Number of serious adverse events Follow‐up: 18 months |

129 per 1000 | 160 per 1000 (54 to 477) | RR 1.24 (0.42 to 3.70) | 317 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 | Absolute risk difference: 3% higher (95% CI 8% lower to 35% higher) Relative percentage change: 24% higher (95% CI 58% lower to 270% higher) NNTH: not applicable (not statistically significant) |

It is uncertain whether anti‐TNF disease activity‐guided dose tapering influences the number of serious adverse events because the certainty of the evidence is very low and because of imprecision. |

| Withdrawals due to adverse events ‐ not measured | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No studies were found that evaluated the number of withdrawals due to adverse events. | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; DAS28: disease activity score in 28 joints; MD: mean difference; mSvdH: modified Sharp van der Heijde; NNTH: number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome; RCT: randomised controlled trial: RR: risk ratio; TNF: tumour necrosis factor | |||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | |||||||

1Downgraded two levels due to heterogeneity (I2=70% for disease activity score and I2=69% for number of serious adverse events). 2Downgraded two levels due to imprecision (insufficient sample size/low number of events). 3Downgraded one level due to heterogeneity (I2=59%). 4Downgraded one level due to imprecision (insufficient sample size).

Background

Description of the condition

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic systemic autoimmune disease characterised by symmetrical joint inflammation that often leads to joint damage. Tumour necrosis factor–blocking (anti‐TNF) agents have proved effective as therapies for RA (Blumenauer 2002; Blumenauer 2003; Navarro‐Sarabia 2005; Ruiz Garcia 2014; Singh 2009; Singh 2010). They improve clinical symptoms and functioning and inhibit joint destruction, and have become an important part of treatment prescribed for RA.

Description of the intervention

Treatment of individuals with RA has been evolving from traditional step‐up regimens to more aggressive step‐down strategies. Pivotal to these changes are the early start of treatment (hit early), the use of combination therapy including steroids with rapid escalation to biologics (hit‐hard), and, most important, frequent assessment of disease activity and treatment modification based on assessment (tight control). Strategies incorporating these concepts lead to the swift achievement of low disease activity or remission in most patients, which prevents joint damage and improves function and quality of life (Schipper 2010). An important disadvantage of the hit‐hard approach compared with the traditional step‐up approach, however, is that the former method does not allow for individual titration of the minimal effective treatment. Indeed, the traditional step‐up approach largely prevents overtreatment, but high(er) disease activity at the beginning of the disease has to be accepted. To prevent overtreatment when high‐dose or multidrug strategies are used, treatment must be tapered down when low disease activity is reached up to the point that disease activity increases again or medication can be stopped. In this way, the minimal effective dose is found and overtreatment is prevented. Optimal dosing of biologics is especially important because of the risk of dose‐dependent adverse effects and the risk of low cost‐effectiveness due to high cost (den Broeder 2010; Ramiro 2017; Singh 2011). The concept of dose reduction has been incorporated into current guidelines for the treatment of RA (Singh 2016; Smolen 2017).

The intervention that is the subject of this review is therefore dose reduction of anti‐TNF agents (by adaptation of dose or dosing interval) or discontinuation or both in people with RA and low disease activity status.

How the intervention might work

Successful dose reduction or discontinuation of anti‐TNF agents can be expected for several reasons. First, amongst patients who seem to respond to treatment with anti‐TNF agents are those who show spontaneous improvement (regression to the mean) (den Broeder 2010; van Vollenhoven 2004); this phenomenon applies to 10% to 30% of all patients, as was shown by proportions of placebo group response (Doherty 2009; St Clair 2004). Second, often concomitant medication is given that might induce a response. Both mechanisms are supported by the fact that a proportion of patients who seem to do well while taking the drug have (neutralising) antibodies (less than 5% to 43%) (Bartelds 2007; Klareskog 2011; Wolbink 2006). Finally, a substantial proportion of patients might need a lower than standard dose for a clinical response (Fautrel 2015; Verhoef 2017). Anti‐TNF agents are registered at the dose that shows the best response for the most patients (top of group level dose‐response curve). However, individual patients might respond to a lower dose as well, which is reflected in response percentages of lower doses in these initial trials (Genovese 2002; Maini 1998; Weinblatt 2003).

Uncontrolled research has shown that down‐titration of anti‐TNF agents can be successful in a relevant proportion of patients. Most data are available for infliximab, adalimumab, and etanercept, and most are derived from discontinuation studies (Brocq 2009; den Broeder 2002; Kavanaugh 2012; Nawata 2008; Saleem 2010; Tanaka 2010; Tanaka 2012; van den Bemt 2008; van der Bijl 2007; van der Maas 2012).

Why it is important to do this review

Although the adverse effects of anti‐TNF agents reported in clinical trials were generally mild in severity, these drugs are associated with unintended effects including increased risk of infection and perhaps a dose‐dependent increased risk of malignancy and rare severe adverse events (Bongartz 2006). The introduction of anti‐TNF agents ‐ and other biological drugs ‐ has also led to an increase in cost because they are much more expensive than traditional disease‐modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) (van Vollenhoven 2009).

It was appropriate at this time to conduct an update of this Cochrane Review of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of anti‐TNF down‐titration as well as discontinuation studies, because several new RCTs on this topic are emerging, and additional information on the already included studies has been published.

Objectives

To evaluate the benefits and harms of down‐titration (dose reduction, discontinuation, or disease activity‐guided dose tapering) of anti‐TNF agents (adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, etanercept, golimumab, infliximab) on disease activity, functioning, costs, safety, and radiographic damage compared with usual care in people with RA and low disease activity.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We considered all randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and controlled clinical trials (CCTs) (including cluster randomised and cross‐over trials) according to the Cochrane definition comparing down‐titration of tumour necrosis factor–blocking (anti‐TNF) agents versus usual care/no down‐titration for inclusion. The minimal required follow‐up was six months. Both superiority and non‐inferiority trials were included.

Types of participants

People with RA (1987, Arnett 1988, or 2010, Aletaha 2010 RA criteria, or both) American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria) using anti‐TNF agents in a standard (or lower) dosing regimen (adalimumab 40 mg every other week, etanercept 50 mg every week or 25 mg twice a week, infliximab 3 mg/kg every eight weeks, golimumab 50 mg every month, certolizumab pegol 200 mg every other week) for longer than six months and with a low disease activity state (clinical judgement of rheumatologist or disease activity score in 28 joints (DAS28) < 3.2; DAS < 2.4; Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI) < 10; Simplified Disease Activity Index (SDAI) < 11 or DAS28 < 2.6; DAS < 1.6; CDAI < 2.8; SDAI < 3.3, Aletaha 2005; Fransen 2005, or 2011 ACR/European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) remission (Felson 2011)).

Types of interventions

Protocolised down‐titration or discontinuation of the anti‐TNF agent for optimal dose finding (not for other reasons, including reduction of side effects, availability, planned surgery, pregnancy). Non‐protocolised change in medication (DMARDs, non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), corticosteroids) was allowed. Comparison was usual care/no down‐titration/continuation of anti‐TNF.

Types of outcome measures

Major outcomes

Mean disease activity score; DAS28/DAS/CDAI/SDAI at six, 12, 18, and 24 months (Aletaha 2005; Prevoo 1995; Smolen 2003; van der Heijde 1990).

Proportion of participants with persistent remission (as specified above) after six, 12, 18, and 24 months.

Proportion of participants that switched to another biologic due to persistent loss of response, refractory to re‐instalment of the tapered anti‐TNF in the intervention group.

Proportion of participants with minimal radiographic progression, as measured by Larsen (Larsen 1973), Sharp (Sharp 1971), or modified Sharp‐van der Heijde score (mSvdH score) (van der Heijde 2000).

Function (as measured by Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ)/Arthritis Impact Measurement Scale (AIMS)).

Number of serious adverse events.

Withdrawals due to adverse events.

Minor outcomes

Proportion of participants with a flare (or loss of response) (defined as any composite disease activity index–based flare criteria) during follow‐up time.

Quality of life as measured by Short Form (SF) Health Survey‐12/36, Health Utilities Index (HUI), or EuroQoL Quality of Life Scale (EQ‐5D).

Costs (direct (e.g. medication, consultations, travel costs) and indirect (e.g. health‐related absenteeism)).

Decremental cost‐effectiveness ratio (difference in costs divided by difference in quality of life expressed as utility, thus the potential savings when accepting the loss of one quality‐adjusted life year (QALY)).

Time to flare.

Change in other medication (including DMARDs, NSAIDs, corticosteroids).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following electronic databases: MEDLINE (1946 to 29 March 2018), Embase (1974 to 29 March 2018), Web of Science (1945 to 2018) and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) 2018 issue 3. The specific search strategy for each of the databases is shown in the appendices (Appendix 1; Appendix 2; Appendix 3; Appendix 4). Our search was not limited by language, year of publication, or publication type. The search period for all databases extended from inception to September 2013 for the original review, and from 2013 to 29 March 2018 for the update.

Searching other resources

We searched proceedings of conferences from 2005 to 2017 of the ACR and from 2005 to 2017 of the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) for abstracts of RCTs and CCTs. We searched reference lists of identified clinical trials and performed citation tracking of the included trials in the ISI Web of Knowledge citation index. We searched trial registries for completed and ongoing trials (Appendix 5). We contacted experts (first authors of included studies) to ask about additional trials.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

We selected studies based on the inclusion criteria outlined in the Criteria for considering studies for this review section. Two review authors (NvH and BJFvdB for the original review; LMV and BJFvdB for the update) independently screened titles and abstracts for inclusion, obtaining full articles if necessary. Any differences were resolved by discussion and consensus or by consultation with a third review author (AAdB) if needed. In case the same study population was described in more than one publication, all publications were used, but for the analysis, all were grouped, with the most informative publication as the primary reference and with other publications as secondary references. We recorded reasons for exclusion of studies.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (NvH and BJFvdB for the original review; LMV and BJFvdB for the update) independently abstracted data from each study using a data extraction form. Any differences were resolved by discussion and consensus or by consultation with a third review author (AAdB) if needed. We pilot‐tested the data extraction form on a selection of trials. If necessary, we contacted the authors of a given study to ask for missing data.

We extracted the following data.

General study information: first author, author affiliation, publication source, publication year, and source of funding.

Study characteristics: design, setting, participant selection, method of randomisation, allocation procedure, blinding, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and study duration.

Population characteristics: age, sex, diagnostic criteria, disease duration, DMARD comedication, previous DMARD use, previous anti‐TNF use, rheumatoid factor status, anti–cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP) status, disease activity state, total number of participants screened, total number of participants recruited, total number of participants randomly assigned, total number of participants followed, and numbers in each group.

Intervention characteristics: anti‐TNF agent, type of intervention (dose reduction/interval widening/discontinuation), treatment comparators.

Outcome measures as noted above.

Analysis: statistical technique used, intention‐to‐treat analyses and/or per‐protocol analyses used.

Results with number, mean and standard deviation.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (NvH and BJFvdB for the original review; LMV and BJFvdB for the update) assessed risk of bias in the included studies in accordance with the recommendations in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Appendix 6) (Higgins 2011).

We assessed the following 'Risk of bias' domains.

Random sequence generation.

Allocation concealment.

Blinding of participants and personnel.

Blinding of outcome assessment.

Incomplete outcome data.

Selective reporting.

Other sources of bias (baseline imbalance in possible prognostic variables: DMARD comedication, duration of anti‐TNF use, and disease duration).

We judged each of these domains as having low, high, or unclear risk of bias.

Measures of treatment effect

We analysed the results of the included studies using Review Manager 2014. Continuous data were expressed as mean differences (MDs) or standardised mean differences (SMDs). Dichotomous data were expressed as risk ratios (RRs). Rates were expressed as rate ratios (RaRs). We summarised data in meta‐analyses if the studies were sufficiently homogeneous, both clinically and statistically.

Unit of analysis issues

The participant was the unit of analysis. Post‐hoc, it was chosen to pool the data from the two dose reduction arms in the study by Ibrahim 2017 (OPTTIRA) for outcomes in which data from multiple studies could be pooled because this facilitated comparison with the 50% dose reduction applied in all other included dose reduction studies (mean dose reduction of 33% and 66% being 50%).

Dealing with missing data

We accepted missing clinical data in trials when they represented less than 20% of findings. We planned to perform a sensitivity analysis if more than 20% of the data from a given study were missing in order to explore the impact of including or excluding such studies. We attempted to obtain missing information on parameter variability by contacting the authors of the trial. In the event that study authors were not able or were unwilling to provide this information, it was estimated from ranges if provided or from comparable trials.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We evaluated heterogeneity first clinically by considering comparability across trials on the following variables: type of intervention (dose reduction/discontinuation/disease activity–guided dose tapering), type of anti‐TNF agent, duration of anti‐TNF use, baseline disease activity (low disease activity versus remission), disease duration, DMARD comedication, and presence of anti‐TNF rescue strategy. We examined forest plots and tested for heterogeneity using the Chi2 test with a P < 0.10 indicating significant heterogeneity. We used the I2 statistic to describe the percentage of variability in effect estimates that is due to heterogeneity rather than to chance (Higgins 2003). A value greater than 50% may indicate substantial heterogeneity (Higgins 2011). If we detected significant heterogeneity (I2 > 80%), we did not pool data but performed subgroup analyses in an attempt to explain the heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

Publication bias implies that studies that report favourable results are more likely to be published than those describing negative or inconclusive (non‐significant) results, leading to a bias in the overall published literature. To minimise the effect of selective reporting of results, we searched trial registries for completed but unpublished studies. We planned to use a funnel plot to assess potential publication bias. However, due to the small number of studies, the funnel plot was not informative. We also searched the trial registries for ongoing studies that are potentially interesting for a future update of this review (see Characteristics of ongoing studies for details), and for additional data on included studies.

We assessed reporting bias at the outcome level by using published protocols of the studies along with published results of the study to compare outcomes intended to be analysed with those actually analysed.

Data synthesis

When possible, we analysed data using an intention‐to‐treat model and, for non‐inferiority studies, by also using a per‐protocol model. Our reason for this was that intention‐to‐treat analyses can lead to false conclusions of non‐inferiority in non‐inferiority trials. We analysed outcomes of included studies using a random‐effects model.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned that if sufficient data were available we would perform subgroup analyses for the following candidate effect modifiers: type of intervention (dose reduction/discontinuation/disease activity–guided dose tapering), type of anti‐TNF agent, duration of anti‐TNF use, baseline disease activity (low disease activity versus remission), disease duration, DMARD comedication, and presence of anti‐TNF rescue strategy.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to perform the following sensitivity analyses when possible.

Effect of risk of bias of included studies.

Effect of imputation of missing data or statistical transformations.

'Summary of findings' tables

We completed three separate 'Summary of findings' tables included in Review Manager 2014 to improve the readability of the review. We examined seven outcomes in a table for each of the three subgroups of down‐titration: (1) dose reduction, (2) discontinuation, and (3) disease activity–guided dose tapering. The study population consisted of people with RA with low disease activity using a standard dose of anti‐TNF. The intervention provided was down‐titration (dose reduction, discontinuation, or disease activity–guided dose tapering). The intervention was compared with usual care (continuation or no formalised dose reduction of anti‐TNF). In addition to the absolute and relative magnitude of effect, the number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) and number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome (NNTH) were calculated by comparing the intervention group with the control group. We used GRADEpro 2015 to conduct an overall grading of the quality of evidence.

The GRADE approach specifies four levels of certainty (high, moderate, low, and very low). The highest certainty rating is given for randomised trial evidence. Randomised trial evidence can be downgraded to moderate, low, or very low depending on the presence of five factors.

Limitations in the design and implementation of available studies suggesting high likelihood of bias.

Indirectness of evidence.

Unexplained heterogeneity or inconsistency of results.

Imprecision of results.

High probability of publication bias.

Results

Description of studies

The results of the search are presented in Figure 1 and are described in detail in the following sections of the review.

1.

Flow chart of study selection.

Results of the search

The previous version of this review included seven studies. Database searches for this update (2013 to March 2018) resulted in 2352 records, and after de‐duplication 1565 search results. Reference checking, contact with experts, and performing additional searches in congress abstract databases and trial registers resulted in 42 additional records. After title and abstract screening of these 1607 records, 21 studies remained. After assessing these 21 studies for eligibility, we identified eight new studies for inclusion in the review. One of the previously included studies, Harigai 2012 (BRIGHT), was retrospectively excluded for this updated version of the review because we considered their method of allocation (at the discretion of the physician) as not random or quasi‐random, which is a prerequisite for the classification as RCT or CCT. Newly found studies that used allocation based on physician or patient preference were also not included in this updated version (Tanaka 2013 (HONOR); Tanaka 2014 (HOPEFUL‐2)). Finally, a total of 14 studies were included in this update of the systematic review, consisting of six old studies and eight new studies. All of the old studies were now available as full text. Of the eight new studies, one was published as abstract and seven as full text.

We contacted the authors of 11 studies to obtain missing data or to clarify methods/results. We received a response from authors of 10 studies.

The total number of participants in the studies included in this review was 3315. Most participants (2111) were included in the eight studies comparing anti‐TNF discontinuation versus anti‐TNF continuation. Six studies (1148 participants) compared anti‐TNF dose reduction versus continuation. Three studies (365 participants) compared disease activity–guided anti‐TNF dose tapering versus continuation. Eleven studies used a superiority design; two studies used a non‐inferiority design; and one study reported an equivalence design.

Included studies

Anti‐TNF dose reduction versus anti‐TNF continuation studies

Design

Six studies compared anti‐TNF fixed‐dose reduction versus anti‐TNF continuation (El Miedany 2016; Ibrahim 2017 (OPTTIRA); Raffeiner 2015; Smolen 2013 (PRESERVE); van Vollenhoven 2016 (DOSERA); Weinblatt 2017 (C‐EARLY)). Weinblatt 2017 (C‐EARLY), Smolen 2013 (PRESERVE), and van Vollenhoven 2016 (DOSERA) were randomised, blinded, placebo‐controlled, superiority studies that reported three arms (discontinuation, dose reduction, and continuation). The randomisation ratio was 1:1:1 for Smolen 2013 (PRESERVE) and van Vollenhoven 2016 (DOSERA); for Weinblatt 2017 (C‐EARLY) this was 2:3:2 (stop; dose reduction; continuation). El Miedany 2016, Raffeiner 2015, and Ibrahim 2017 (OPTTIRA) were open‐label superiority studies. The study by Raffeiner 2015 was reported as a prospective long‐term follow‐up study; randomisation was done in a consecutive manner (alternation) in a ratio 1:1, which we defined as quasi‐random, making the study a CCT. The randomisation ratio for Ibrahim 2017 (OPTTIRA) was 1:1:2, and for El Miedany 2016 it was 1:1:1:1:1 (only group 1 and group 5 were relevant for this review).

The duration of the included studies was 6 months in Ibrahim 2017 (OPTTIRA); 40 weeks in van Vollenhoven 2016 (DOSERA); 52 weeks in Smolen 2013 (PRESERVE), El Miedany 2016, and Weinblatt 2017 (C‐EARLY); and a mean follow‐up of 3.5 ± 1.5 years in Raffeiner 2015. The study by Smolen 2013 (PRESERVE) had a total follow‐up of 88 weeks, however 52 weeks of follow‐up were provided after randomisation for dose reduction or continuation of etanercept. The total follow‐up for van Vollenhoven 2016 (DOSERA) was 48 weeks, and 40 weeks of follow‐up were provided after randomisation for dose reduction or continuation of etanercept. The study by Weinblatt 2017 (C‐EARLY) describes period 2 of the C‐EARLY study with a duration of 52 weeks, which was a re‐randomisation of participants from the first period, which also lasted 52 weeks.

Sample size

The sample size for this comparison varied from 50 participants in the study by van Vollenhoven 2016 (DOSERA) (73 participants in total study due to multiple intervention arms) to 404 participants in Smolen 2013 (PRESERVE) (604 participants in total study due to multiple intervention arms).

Setting

Ibrahim 2017 (OPTTIRA) reported that participants were screened at 20 centres in the United Kingdom. The study by Raffeiner 2015 was reported as a single‐centre study in Italy. Smolen 2013 (PRESERVE) was reported to have been conducted in 80 centres in Europe, Latin America, Asia, and Australia. The study by van Vollenhoven 2016 (DOSERA) was performed in 16 rheumatology units in Sweden (5), Denmark (2), Finland (2), Norway (3), Hungary (3), and Iceland (1). Weinblatt 2017 (C‐EARLY) reported that it recruited participants at 103 centres in in Europe, Australia, North America, and Latin America. El Miedany 2016 did not report a specific setting.

Participants

El Miedany 2016 did not provide information on participant characteristics. Most participants were female in the studies by van Vollenhoven 2016 (DOSERA), Smolen 2013 (PRESERVE), Weinblatt 2017 (C‐EARLY), and Raffeiner 2015. Mean age was approximately 47 years in Smolen 2013 (PRESERVE); 49 years in Weinblatt 2017 (C‐EARLY); 56 years in Raffeiner 2015; and 57 years in van Vollenhoven 2016 (DOSERA) and Ibrahim 2017 (OPTTIRA). Disease duration ranged from around 2.6 months in Weinblatt 2017 (C‐EARLY) (median disease duration at baseline of C‐EARLY period 1) to 14 years in Raffeiner 2015 and van Vollenhoven 2016 (DOSERA). Duration of anti‐TNF agents had to be > 3 months in Ibrahim 2017 (OPTTIRA); ≥ 6 months in El Miedany 2016; ≥ 12 months in Raffeiner 2015; and ≥ 14 months in van Vollenhoven 2016 (DOSERA). Smolen 2013 (PRESERVE) started the anti‐TNF agent at study start 36 weeks before randomisation for dose reduction or discontinuation. In the study by Weinblatt 2017 (C‐EARLY), all participants had started certolizumab pegol treatment one year earlier (period 1 of C‐EARLY). El Miedany 2016 and Ibrahim 2017 (OPTTIRA) did not report previous use of DMARDs. Participants in Raffeiner 2015 and Smolen 2013 (PRESERVE) were biologic disease‐modifying antirheumatic drug (bDMARD) naive before the study. Raffeiner 2015 reported a mean (standard deviation (SD)) of 2.4 (1.1) previously used DMARDs in the dose reduction group and 2.4 (1.3) in the continuation group. Participants in Weinblatt 2017 (C‐EARLY) were bDMARD and conventional synthetic disease‐modifying antirheumatic drug (csDMARD) naive. van Vollenhoven 2016 (DOSERA) described that 66% of the participants had used a DMARD other than methotrexate (MTX) before the study.

In all included studies, participants had to have low disease activity, Ibrahim 2017 (OPTTIRA); Smolen 2013 (PRESERVE); van Vollenhoven 2016 (DOSERA); Weinblatt 2017 (C‐EARLY), or remission, El Miedany 2016; Raffeiner 2015. Duration of low disease activity/remission had to be > 3 months in Ibrahim 2017 (OPTTIRA); ≥ 6 months in El Miedany 2016; ≥ 12 months in Raffeiner 2015; or ≥ 11 months in van Vollenhoven 2016 (DOSERA). Participants in the study by Smolen 2013 (PRESERVE) had to have a mean DAS28 ≤ 3.2 in the 24‐week period before randomisation and a DAS28 ≤ 3.2 at the moment of randomisation. In the study by Weinblatt 2017 (C‐EARLY), participants needed to have a DAS28 ≤ 3.2 12 weeks before randomisation and at the moment of randomisation. All included studies used a DAS28‐based criterion to define low disease activity or remission.

Intervention and comedication

Raffeiner 2015 reported etanercept dose reduction by comparing etanercept 25 mg twice a week versus etanercept 25 mg once a week. Smolen 2013 (PRESERVE) and van Vollenhoven 2016 (DOSERA) reported etanercept dose reduction (25 mg/week) compared with etanercept continuation (50 mg/week). Ibrahim 2017 (OPTTIRA) reported 33% and 66% dose reduction of adalimumab and etanercept versus 100%. El Miedany 2016 reported 50% dose reduction of bDMARDs versus continuation. Weinblatt 2017 (C‐EARLY) reported 50% dose reduction of certrolizumab pegol (200 mg/4 weeks) versus continuation (200 mg/2 weeks). Participants were required to use MTX comedication (dose ranged from 7.5 to 25 mg/week) in Smolen 2013 (PRESERVE) and van Vollenhoven 2016 (DOSERA). In Raffeiner 2015, steroids, NSAIDs, and DMARDs were continued at the same dosages. No intra‐articular steroids were permitted during the study period. Smolen 2013 (PRESERVE) allowed up to three intra‐articular corticosteroid injections during the study. In the study by van Vollenhoven 2016 (DOSERA), participants continued MTX and other medications at the same dose. Participants in Weinblatt 2017 (C‐EARLY) used MTX in the maximum tolerated ("optimised") dose throughout the study. Use of intra‐articular, intramuscular, or intravenous corticosteroids at any dose was prohibited. The maximum allowed dose of oral corticosteroids during the study was ≥ 10 mg/day prednisone or equivalent, and no changes in dose were allowed during the study period. In the study of El Miedany 2016, participants in the relevant study arms used a stable dose of a csDMARD during the trial. No intramuscular or local steroid joint injections were allowed. In five studies (El Miedany 2016; Ibrahim 2017 (OPTTIRA); Raffeiner 2015; van Vollenhoven 2016 (DOSERA); Weinblatt 2017 (C‐EARLY)), participants could return to their initial dose of anti‐TNF after disease flare. In Smolen 2013 (PRESERVE), no attempt was made to recapture low disease activity by reintroducing etanercept in participants whose condition had deteriorated after etanercept withdrawal.

Outcomes

All studies reported a primary outcome measure. Three studies reported proportion of participants with low disease activity or remission as the primary outcome. Raffeiner 2015 and El Miedany 2016 used DAS28 ≤ 2.6, and Smolen 2013 (PRESERVE) used DAS28 ≤ 3.2. The primary outcome in the study by van Vollenhoven 2016 (DOSERA) was proportion of non‐failures for etanercept 50 mg/week versus placebo. The primary outcome for Ibrahim 2017 (OPTTIRA) was reported to be time to flare. Weinblatt 2017 (C‐EARLY) reported maintenance of low disease activity (disease activity score in 28 joints using erythrocyte sedimentation rate (DAS28‐ESR) of ≤ 3.2) for all 5 consecutive study visits to week 52 without flares as the primary outcome measure. Secondary outcomes reported in the included studies were very different. None of the included studies provided data on costs or change in comedication. All studies were analysed with a (modified) intention‐to‐treat approach.

Anti‐TNF discontinuation versus anti‐TNF continuation studies

Design

Eight of the included studies reported anti‐TNF discontinuation compared with anti‐TNF continuation (Chatzidionysiou 2016 (ADMIRE); Ghiti Moghadam 2016 (POEET); Pavelka 2017; Smolen 2013 (PRESERVE); Smolen 2014 (OPTIMA); van Vollenhoven 2016 (DOSERA); Weinblatt 2017 (C‐EARLY); Yamanaka 2016 (ENCOURAGE)). All included studies were randomised controlled superiority studies comparing anti‐TNF discontinuation versus continuation. Smolen 2014 (OPTIMA), Smolen 2013 (PRESERVE), van Vollenhoven 2016 (DOSERA), Pavelka 2017, and Weinblatt 2017 (C‐EARLY) were blinded placebo‐controlled studies. The other studies were open‐label studies (Chatzidionysiou 2016 (ADMIRE); Ghiti Moghadam 2016 (POEET); Yamanaka 2016 (ENCOURAGE)). Chatzidionysiou 2016 (ADMIRE) was reported to be a pilot study. Smolen 2013 (PRESERVE), van Vollenhoven 2016 (DOSERA), and Weinblatt 2017 (C‐EARLY) reported three arms (both discontinuation and dose reduction compared with continuation).

Smolen 2013 (PRESERVE) and van Vollenhoven 2016 (DOSERA) reported a 1:1:1 randomisation ratio, and Weinblatt 2017 (C‐EARLY) a randomisation ratio of 2:3:2. Chatzidionysiou 2016 (ADMIRE), Pavelka 2017, Smolen 2014 (OPTIMA), and Yamanaka 2016 (ENCOURAGE) reported a 1:1 randomisation ratio. Ghiti Moghadam 2016 (POEET) randomised in a ratio of 2:1 (discontinuation versus continuation). Smolen 2013 (PRESERVE), Smolen 2014 (OPTIMA), Pavelka 2017, and van Vollenhoven 2016 (DOSERA) reported a "run‐in" period in which anti‐TNF treatment was given open‐label, before randomisation was provided for anti‐TNF continuation, discontinuation, or dose reduction in a double‐blind phase.

The duration of the included studies was 48 weeks for van Vollenhoven 2016 (DOSERA) (40 weeks double‐blind period); 52 weeks for Chatzidionysiou 2016 (ADMIRE), Ghiti Moghadam 2016 (POEET), and Pavelka 2017 (28 weeks double‐blind period). Weinblatt 2017 (C‐EARLY) reported a total follow‐up of 104 weeks, in which the second 52‐week double blind period was of interest for this review. Smolen 2014 (OPTIMA) and Smolen 2013 (PRESERVE) reported a total follow‐up of 78 weeks and 88 weeks, respectively; however, both described 52‐week follow‐up after randomisation for discontinuation or continuation of the anti‐TNF agent. Yamanaka 2016 (ENCOURAGE) described a period of one year in which participants were treated with open‐label etanercept and MTX before they were randomised to open‐label continuation or discontinuation.

Sample size

The sample size varied from 31 participants in Chatzidionysiou 2016 (ADMIRE) to 817 in Ghiti Moghadam 2016 (POEET).

Setting

All eight studies were reported as multicentre studies. Chatzidionysiou 2016 (ADMIRE) was performed in several hospitals in Sweden, and Ghiti Moghadam 2016 (POEET) in 47 rheumatology centres throughout the Netherlands. Smolen 2013 (PRESERVE) reported that the study was conducted in 80 centres in Europe, Latin America, Asia, and Australia. van Vollenhoven 2016 (DOSERA) recruited participants at 16 rheumatology units in Sweden (5), Denmark (2), Finland (2), Norway (3), Hungary (3), and Iceland (1). Pavelka 2017 was conducted at 61 centres in 19 countries in Africa, Asia, Central and Eastern Europe, Latin America, and the Middle East. Smolen 2014 (OPTIMA) reported 161 sites around the world. Weinblatt 2017 (C‐EARLY) was conducted at 103 participating sites in Europe, Australia, North America, and Latin America. Yamanaka 2016 (ENCOURAGE) was a co‐operation of rheumatology institutes/departments in Japan and Korea.

Participants

Six studies reported a minimum age of 18 years for inclusion (Chatzidionysiou 2016 (ADMIRE); Pavelka 2017; Smolen 2013 (PRESERVE); Smolen 2014 (OPTIMA); van Vollenhoven 2016 (DOSERA); Weinblatt 2017 (C‐EARLY)). Ghiti Moghadam 2016 (POEET) was reported to include people 18 years of age or older. Smolen 2013 (PRESERVE) reported an upper age limit (70 years) for inclusion. Yamanaka 2016 (ENCOURAGE) did not report any age criteria. The mean age of participants varied from around 47 in Pavelka 2017 and Smolen 2013 (PRESERVE) to early 60s in Chatzidionysiou 2016 (ADMIRE) and Ghiti Moghadam 2016 (POEET). Most participants in the included studies were female. Mean disease duration ranged from seven to 14 years, except in Smolen 2014 (OPTIMA), in which the mean disease duration was only 3.9 months; Weinblatt 2017 (C‐EARLY), in which median disease duration was around 2.7 months (measured one year before randomisation); and Yamanaka 2016 (ENCOURAGE), in which mean disease duration was two years. Duration of the anti‐TNF agent had to be ≥ 6 months in Chatzidionysiou 2016 (ADMIRE); ≥ 1 year in Ghiti Moghadam 2016 (POEET); and ≥ 14 months in van Vollenhoven 2016 (DOSERA). Pavelka 2017, Smolen 2014 (OPTIMA), Smolen 2013 (PRESERVE), and Yamanaka 2016 (ENCOURAGE) started the anti‐TNF agent at study start, 24 weeks, 26 weeks, 36 weeks, and 1 year, respectively before randomisation for dose reduction or discontinuation. In the study by Weinblatt 2017 (C‐EARLY), participants were treated with certolizumab pegol (blinded) one year before randomisation for dose reduction or discontinuation. Participants in Smolen 2013 (PRESERVE), Smolen 2014 (OPTIMA), and Weinblatt 2017 (C‐EARLY) were bDMARD naive before study start. Smolen 2014 (OPTIMA) reported that 8.8% of participants in the discontinuation group and 9.5% in the continuation group had used ≥ 1 DMARD. Chatzidionysiou 2016 (ADMIRE) reported a median of 1 (interquartile range (IQR) 0 to 1) number of previous bDMARDs and 2 (IQR 1 to 3) previous csDMARDs. In the study by Ghiti Moghadam 2016 (POEET), 13.4% of participants in the discontinuation group and 15% in the continuation group had previously used a bDMARD. In Pavelka 2017, 34% of participants in the discontinuation group had previously used a csDMARD versus 38% in the continuation group. van Vollenhoven 2016 (DOSERA) reported that 66% of all participants had used a DMARD other than MTX before study start. Yamanaka 2016 (ENCOURAGE) did not report on prior DMARD use.

Participants in all included studies had to have low disease activity, Ghiti Moghadam 2016 (POEET); Pavelka 2017; Smolen 2013 (PRESERVE); Smolen 2014 (OPTIMA); van Vollenhoven 2016 (DOSERA); Weinblatt 2017 (C‐EARLY), or remission, Chatzidionysiou 2016 (ADMIRE); Yamanaka 2016 (ENCOURAGE). The duration of low disease activity had to be 4 weeks in Smolen 2014 (OPTIMA); ≥ 3 months in Chatzidionysiou 2016 (ADMIRE); ≥ 6 months in Ghiti Moghadam 2016 (POEET); or ≥ 11 months in van Vollenhoven 2016 (DOSERA). Participants in the study by Smolen 2013 (PRESERVE) had to have a mean DAS28 ≤ 3.2 in the 24‐week period before randomisation and a DAS28 ≤ 3.2 at the moment of randomisation. In the study by Weinblatt 2017 (C‐EARLY), participants needed to have a DAS28 ≤ 3.2 12 weeks before randomisation and at the moment of randomisation. In Yamanaka 2016 (ENCOURAGE), participants had to have a DAS < 2.6 at 6 and 12 months after study start. Pavelka 2017 reported that participants had to have low disease activity after period 1 (24 weeks after study start). All included studies used a DAS28‐based criterion to define low disease activity or remission.

Intervention and comedication

Smolen 2013 (PRESERVE), van Vollenhoven 2016 (DOSERA), Yamanaka 2016 (ENCOURAGE), and Pavelka 2017 reported etanercept discontinuation compared with etanercept continuation. The studies by Chatzidionysiou 2016 (ADMIRE) and Smolen 2014 (OPTIMA) reported adalimumab discontinuation compared with adalimumab continuation. Ghiti Moghadam 2016 (POEET) reported discontinuation of all anti‐TNF agents versus anti‐TNF continuation. Weinblatt 2017 (C‐EARLY) reported discontinuation of certolizumab pegol compared to continuation of the standard dose.

Participants in most included studies were required to use MTX comedication (dose ranged from 6 to 25 mg/week). Ghiti Moghadam 2016 (POEET) included participants using any csDMARD comedication. Participants included in Smolen 2014 (OPTIMA) were MTX naive at the start of the study (26 weeks before randomisation for discontinuation or continuation of adalimumab). Seven studies stated that participants could restart the anti‐TNF after disease flare (Chatzidionysiou 2016 (ADMIRE); Ghiti Moghadam 2016 (POEET); Pavelka 2017; Smolen 2014 (OPTIMA); van Vollenhoven 2016 (DOSERA); Weinblatt 2017 (C‐EARLY); Yamanaka 2016 (ENCOURAGE)). The study by Smolen 2013 (PRESERVE) allowed up to three intra‐articular corticosteroid injections during the study; however, no attempt was made to recapture low disease activity by reintroducing etanercept in participants whose condition had deteriorated after etanercept withdrawal.

Outcomes

All studies reported a primary outcome measure; for most studies this was proportion of participants with low disease activity or remission. All studies used DAS28‐based criteria, but different definitions were employed. Chatzidionysiou 2016 (ADMIRE) and Yamanaka 2016 (ENCOURAGE) used DAS28 remission (< 2.6). Smolen 2013 (PRESERVE) and Pavelka 2017 used DAS28 low disease activity (≤ 3.2 for Smolen 2013 (PRESERVE) and < 3.2 for Pavelka 2017). Weinblatt 2017 (C‐EARLY) reported maintenance of low disease activity (DAS28‐ESR of ≤ 3.2) for all 5 consecutive study visits to week 52 without flares as the primary outcome measure. Ghiti Moghadam 2016 (POEET) reported proportion of participants with a flare (DAS28 ≥ 3.2 plus an increase > 0.6) as the primary outcome. The primary outcome in the study by van Vollenhoven 2016 (DOSERA) was proportion of non‐failure. The primary outcome in Smolen 2014 (OPTIMA) was the proportion of participants with both low disease activity and radiographic non‐progression; however, this concerned a comparison of study groups that was not of interest for this review (adalimumab continuation versus methotrexate monotherapy). Secondary outcomes reported in the included studies concerned many different domains, including participant‐reported outcomes (function, quality of life), radiographic outcomes, number of flares, relapse‐free survival, and safety outcomes. None of the included studies provided data on costs or change in comedication. All studies were analysed with a (modified) intention‐to‐treat approach.

Disease activity–guided dose tapering until stop versus anti‐TNF continuation studies

Design

Three studies compared disease activity–guided anti‐TNF dose tapering with anti‐TNF continuation (Bejerano 2016 (OPTIBIO) (abstract only); Fautrel 2016 (STRASS); van Herwaarden 2015 (DRESS)). All studies were open‐label RCTs. van Herwaarden 2015 (DRESS) and Bejerano 2016 (OPTIBIO) were reported to be non‐inferiority studies. Fautrel 2016 (STRASS) reported an equivalence design. Randomisation ratio was 2:1 (dose tapering versus continuation) in van Herwaarden 2015 (DRESS) and 1:1 in Fautrel 2016 (STRASS) and Bejerano 2016 (OPTIBIO). Study duration was 1 year for Bejerano 2016 (OPTIBIO) and 18 months for van Herwaarden 2015 (DRESS) and Fautrel 2016 (STRASS).

Sample size

The sample size varied from 48 in Bejerano 2016 (OPTIBIO) (66 in the total study, which also included other biologics besides anti‐TNF) to 180 in van Herwaarden 2015 (DRESS). The projected sample size for the study by Fautrel 2016 (STRASS) was 250 participants; however, only 137 participants were included. The abstract on Bejerano 2016 (OPTIBIO) reported preliminary data.

Setting

van Herwaarden 2015 (DRESS) and Fautrel 2016 (STRASS) were reported to be multicentre studies. van Herwaarden 2015 (DRESS) included patients from two hospitals in the Netherlands, and Fautrel 2016 (STRASS) recruited participants at 22 rheumatology departments in France and one department in Monaco. Bejerano 2016 (OPTIBIO) was a monocentre study conducted in a hospital in Spain.

Participants

The abstract by Bejerano 2016 (OPTIBIO) provided no information on participant characteristics of anti‐TNF users only. The mean age of participants was 56 years in the study by Fautrel 2016 (STRASS) and 59 years in the study by van Herwaarden 2015 (DRESS). Most participants were female in Fautrel 2016 (STRASS) and van Herwaarden 2015 (DRESS). Mean disease duration at baseline was about 10 years for both Fautrel 2016 (STRASS) and van Herwaarden 2015 (DRESS). Participants in van Herwaarden 2015 (DRESS) had a median of 2 (IQR 1 to 3) previous DMARDs and 0 (IQR 0 to 1) previous anti‐TNF agents. Fautrel 2016 (STRASS) reported a mean (SD) of 2.7 (1.7) previous DMARDs, and 24% of participants had previously used a bDMARD.

The duration of anti‐TNF agents had to be ≥ 6 months in van Herwaarden 2015 (DRESS) and > 1 year in Fautrel 2016 (STRASS). Bejerano 2016 (OPTIBIO) reported no minimal duration of anti‐TNF use. Participants in Bejerano 2016 (OPTIBIO) had to have clinical remission (DAS < 2.6, SDAI < 5, or ACR/EULAR 2011 criteria) for ≥ 6 months. Participants in Fautrel 2016 (STRASS) needed to have a DAS28 ≤ 2.6 for ≥ 6 months with no structural damage progression. Participants in van Herwaarden 2015 (DRESS) had to have stable low disease activity (DAS28 < 3.2) at two subsequent visits.

Intervention and comedication

All three studies reported disease activity–guided dose tapering. Bejerano 2016 (OPTIBIO) included all anti‐TNF agents, while Fautrel 2016 (STRASS) and van Herwaarden 2015 (DRESS) included adalimumab and etanercept. Dose tapering in Fautrel 2016 (STRASS) was done by increasing the interval between two subcutaneous injections by 50% every three months up to a complete stop in the fourth step; if DAS28 remission (DAS28 ≤ 2.6) was not maintained, dose tapering was suspended or was reversed to the previous interval based on DAS28 level. The dose reduction strategy in van Herwaarden 2015 (DRESS) consisted of stepwise increases of the time interval between injections every three months until complete stop in the third step. In the instance of a flare (∆DAS28‐CRP score > 1.2, or ∆DAS28‐CRP > 0.6, and a current score of ≥ 3.2), the last effective interval was reinstated. The dose reduction strategy in Bejerano 2016 (OPTIBIO) consisted of a stepwise increase in interval every year with withdrawal as the third step. In case of flare (DAS28 > 2.6 or SDAI > 5 or ACR/EULAR criteria not fulfilled), participants returned to the standard dose. In all studies, the dose‐tapering intervention was compared with unchanged continuation of the anti‐TNF agents.

Outcomes

All studies reported a primary outcome measure that was based on the DAS28 score. Fautrel 2016 (STRASS) reported standardised difference of DAS28 slopes based on a linear mixed‐effects model as the primary outcome compared to an equivalence margin of ±30%. For van Herwaarden 2015 (DRESS), this was difference in proportions of participants with major flare (DAS28‐CRP‐based flare longer than three months) compared with a non‐inferiority margin of 20%. The primary outcome measure in Bejerano 2016 (OPTIBIO) was the proportion of participants that maintained clinical remission after one year. The abstract for this study did not report on secondary outcome measures. Several secondary measures were reported in Fautrel 2016 (STRASS) and van Herwaarden 2015 (DRESS), including function, radiographic progression, and adverse events. Fautrel 2016 (STRASS) and van Herwaarden 2015 (DRESS) primarily performed a per‐protocol analysis and additionally performed an intention‐to‐treat analysis. Bejerano 2016 (OPTIBIO) did not specify their analysis approach, which was therefore labelled as intention‐to‐treat.

Excluded studies

We excluded 29 articles from this review (15 for the original publication and 14 from the updated version). Fourteen articles (concerning 13 studies) reported anti‐TNF down‐titration without an anti‐TNF continuation control arm (Awan 2011; Bejarano 2010; Detert 2013 (HIT‐HARD); Emery 2013 (PRIZE); Heimans 2016 (IMPROVED); Klarenbeek 2011; Oba 2017 (RRRR study); Quinn 2005; Seddighzadeh 2014 (NORD‐STAR); Smolen 2012 (CERTAIN); van den Broek 2011; van der Kooij 2009; Villeneuve 2012; Wiland 2016 (PRIZE)). In four studies, allocation to anti‐TNF continuation or discontinuation was based on patient or physician preference (Harigai 2012 (BRIGHT); Rakieh 2013; Tanaka 2013 (HONOR); Tanaka 2014 (HOPEFUL‐2)), therefore these study were not classified as RCT or CCT. Tada 2012 (PRECEPT) reported low‐dose versus standard‐dose etanercept from study start. In the study by Haschka 2016 (RETRO), participants were randomised to dose reduction or discontinuation of all DMARDs, therefore the intervention was too broad for this review. The studies by Kobelt 2011 and Kobelt 2014 provided data from a Markov model. Aletaha 2010, Ichikawa 2007, and Keystone 2003 were overview articles. Ramírez‐Herráiz 2013 was a retrospective study; CADTH Report 2014 described a literature study; and Greenberg 2014 was a cohort study. In the study by Haraoui 2014, no doses below standard dose were investigated.

See Characteristics of excluded studies for more information.

Risk of bias in included studies

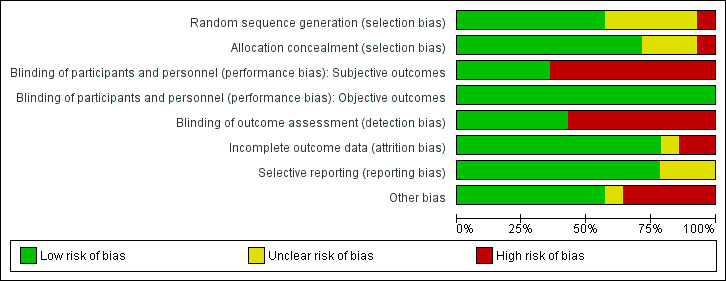

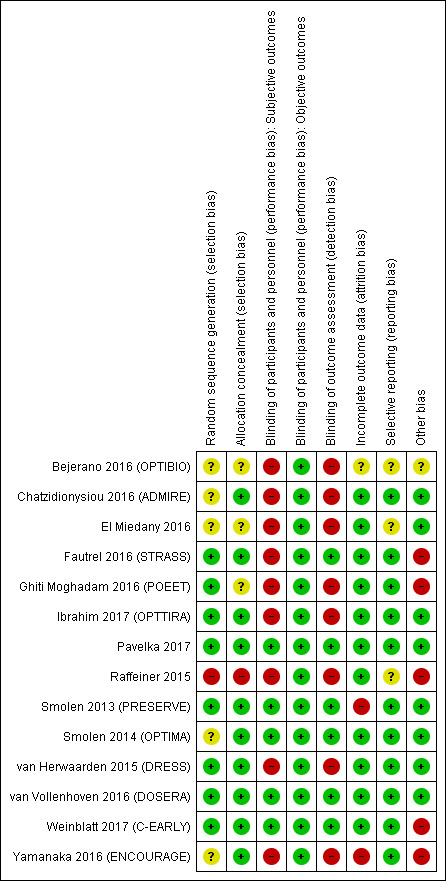

See Characteristics of included studies for 'Risk of bias' tables with information on all aspects of risk of bias. Graphic summaries of the risk of bias in included studies are shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Seven included studies described an adequate random sequence generation and allocation concealment procedure, resulting in an assessment of low risk of selection bias (Fautrel 2016 (STRASS); Ibrahim 2017 (OPTTIRA); Pavelka 2017; Smolen 2013 (PRESERVE); van Herwaarden 2015 (DRESS); van Vollenhoven 2016 (DOSERA); Weinblatt 2017 (C‐EARLY)). The precise method of random sequence generation was not described in three studies (Chatzidionysiou 2016 (ADMIRE); Smolen 2014 (OPTIMA); Yamanaka 2016 (ENCOURAGE)). Ghiti Moghadam 2016 (POEET) did not describe allocation concealment. The methods of randomisation and allocation concealment were not described in the abstract by Bejerano 2016 (OPTIBIO) and the study by El Miedany 2016. The study by Raffeiner 2015 described alternation as the method of randomisation, which resulted in a judgement of high risk of selection bias.

Blinding

Five studies were reported to be placebo controlled (Pavelka 2017; Smolen 2013 (PRESERVE); Smolen 2014 (OPTIMA); van Vollenhoven 2016 (DOSERA); Weinblatt 2017 (C‐EARLY)). The remaining nine studies were open‐label (Bejerano 2016 (OPTIBIO); Chatzidionysiou 2016 (ADMIRE); El Miedany 2016; Fautrel 2016 (STRASS); Ghiti Moghadam 2016 (POEET); Ibrahim 2017 (OPTTIRA); Raffeiner 2015; van Herwaarden 2015 (DRESS); Yamanaka 2016 (ENCOURAGE)); five of these described blinding of X‐ray reading (Fautrel 2016 (STRASS); Ibrahim 2017 (OPTTIRA); Raffeiner 2015; van Herwaarden 2015 (DRESS); Yamanaka 2016 (ENCOURAGE), and the study by Fautrel 2016 (STRASS) also reported blinded DAS28 measurements, which resulted in an assessment of low risk of detection bias.

Incomplete outcome data

We used three criteria for judging this item: intention‐to‐treat analyses, imputation of missing data, and attrition rate.