Abstract

Conservative (non-operative) treatment of Achilles tendon ruptures is a common alternative to operative treatment. Following rupture, ankle immobilization in plantarflexion is thought to aid healing by restoring tendon end-to-end apposition. However, early activity may improve limb function, challenging the role of immobilization position on tendon healing, as it may affect loading across the injury site. This study investigated the effects of ankle immobilization angle in a rat model of Achilles tendon rupture. We hypothesized that manipulating the ankle from full plantarflexion into a more dorsiflexed position during the immobilization period would result in superior hindlimb function and tendon properties, but that prolonged casting in dorsiflexion would result in inferior outcomes. After Achilles tendon transection, animals were randomized into eight immobilization groups ranging from full plantarflexion (160°) to mid-point (90°) to full dorsiflexion (20°), with or without angle manipulation. Tendon properties and ankle function were influenced by ankle immobilization position and time. Tendon lengthening occurred after 1 week at 20° compared to more plantarflexed angles, and was associated with loss of propulsion force. Dorsiflexing the ankle during immobilization from 160° to 90° produced a stiffer, more aligned tendon, but did not lead to functional changes compared to immobilization at 160°. Although more dorsiflexed immobilization can enhance tissue properties and function of healing Achilles tendon following rupture, full dorsiflexion creates significant tendon elongation regardless of application time. This study suggests that the use of moderate plantarflexion and earlier return to activity can provide improved clinical outcomes.

Keywords: Animal model, immobilization, gait analysis, orthopaedics, biomechanics

INTRODUCTION

Operative treatment of Achilles tendon ruptures has been increasing in the United States.1 Surgical treatment has been thought to provide better outcomes compared to non-operative treatment by achieving secure tendon end approximation and reduced rates of tendon re-rupture.2,3 However, surgical repair is also associated with increased direct and indirect costs of care,4 and there are known risks of this surgical procedure, including deep infections, scarring, and sural nerve sensory disturbances.5 Additionally, the affected patient population is increasing in average age and BMI,6 potentially placing them at higher risk of these and other surgical complications.7 Recent non-operative treatment protocols have demonstrated a re-rupture risk similar to that of operative repair,1,8 but the essential healing environment needed to restore tendon structure and function has yet to be defined.9

Historically, non-operative treatment of Achilles tendon ruptures consisted of flexion of the knee, plantarflexion of the ankle, and no weight bearing on the injured limb.10 These measures minimize load transmission to healing tissue and minimize gap formation between ruptured tendon ends.11 Recently, the notion of a weight-bearing restriction has been challenged by studies in which the use of weight-bearing casts in non-operative treatment of Achilles rupture were shown to produce outcomes equivalent to those with non-weight-bearing casts.12,13 Early weight-bearing after Achilles injury has also been associated with decreased ankle stiffness compared to non-weight bearing protocols,14 which could lead to improvements in gait and function.

Early muscle activation and ankle range of motion (ROM) are also thought to improve non-operative treatment by preventing ankle stiffness and aiding muscle recovery.13,14 Muscle performance after completing treatment for an Achilles rupture, as measured by single-leg heel rise, is correlated with positive patient-reported outcomes and activity levels.15 Therefore, a successful non-operative healing strategy may ideally include active recovery and motion while simultaneously preventing tendon gap formation and subsequent lengthening. The clinical practice guidelines by the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) recommend that rehabilitation involve incremental increases in ankle dorsiflexion (decreases in ankle plantarflexion, and hence decreases in immobilization angle measured between the lower leg and foot) alongside gradually increased weight bearing over a 6 to 8 week period of immobilization.16 Minimal plantarflexion (less than 10° from neutral) results in substantially decreased gastrocnemius-soleus contractile activity and decreased tendon stress17, both of which may hinder active recovery during later stages of healing. However, despite these implications, the effects of ankle position on Achilles tendon healing following acute rupture have yet to be systematically characterized.

Early rehabilitation strategies have been tested in our rat model of Achilles tendon rupture, which also support the use of nonsurgical treatment and early return to activity.18–20 The objective of this study was to use this well-described rat model18,21 to investigate the effects of ankle flexion and immobilization duration, assessing ankle joint function and Achilles tendon mechanical, structural, and histological properties six weeks post-injury. We hypothesized that (1) while some dorsiflexion may improve early tendon healing properties, excessive ankle dorsiflexion at the time of immobilization would result in inferior tendon properties and function compared to a fully plantarflexed immobilization, (2) manipulation to increase ankle dorsiflexion position during a longer immobilization period would improve recovery of tendon properties and ankle function, and (3) the effects of a specific immobilization angle on tendon properties and function would depend on how long the ankle was immobilized at that angle prior to active rehabilitation.

METHODS

Development and Validation of Immobilization Technique and Splint Fabrication

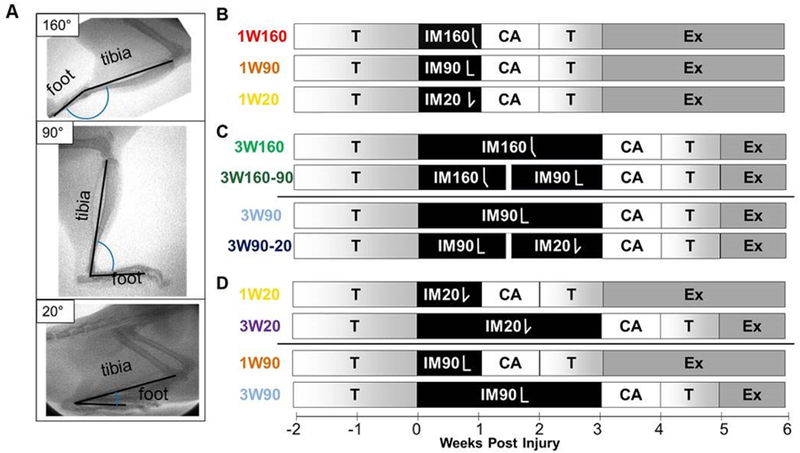

Fresh-frozen cadaveric male Sprague-Dawley rats were thawed and used for evaluation of casting. Using fluoroscopy, right ankles underwent evaluation of total ROM, and normal resting position, as measured by the angle subtended by the mechanical axis of the tibia and the midfoot. Three positions of immobilization (IM) were selected that span the full ROM of the ankle joint: fully plantarflexed (160° tibiopedal angle), sitting position (20° tibiopedal angle), and mid-point (90° tibiopedal angle) (Fig. 1A). Custom-designed 3-D printed acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS) splints were made for each corresponding ankle position (MakerBot Industries, LLC; Brooklyn, NY). These splints were padded with Webril (Hanna Pharmaceutical; Wilmington, DE), and secured to the skin with silk tape stirrups (3M; St. Paul, MN), and Webril padded CoFlex (Andover Healthcare; Salisbury, MA) straps. This construct was then overwrapped with an additional layer of Webril and CoFlex from the knee to the toes before being coated with poly(methyl-methacrylate) (PMMA) (Patterson Dental; St. Paul, MN) to resist chewing damage.18–20

Figure 1. Study Design.

(A)Ankle immobilization angle was confirmed with fluoroscopy. Following exercise training (T), animals had their central right plantaris removed and right Achilles tendon bluntly transected. After surgery, animals were immediately placed in one of three casts: full plantarflexion (160° tibiopedal angle, IM160), mid-point (90° tibiopedal angle, IM90), and anatomic sitting position (20° tibiopedal angle, IM20). Within each angle, animals were assigned to either one week of immobilization (1W) or three weeks of immobilization (3W). Two groups assigned to 3W underwent manipulation on the 11th day of their 3 week immobilization period (160° to 90°, IM160–90; 90° to 20°, 90–20). After cast removal, animals were allowed cage activity (CA) for one week, followed by one week of treadmill training (T), followed by treadmill running (exercise, Ex) daily until sacrifice. All animals were sacrificed six weeks post-injury (n=16/group). Comparisons were made to compare (B) the effects of increased dorsiflexion during immobilization for 1 week to the standard plantarflexed position (1W160 vs. [1W90 or 1W20]), data shown in Figures 2 and 3; (C) the effects of manipulation of ankle angle during immobilization starting from 160 degrees (3W160 vs 3W160–90) or 90 degrees (3W90 vs 3W90–20), data shown in Figures 4 and 5; and (D) the effects of dorsiflexion immobilization duration at 90 degrees (1W90 vs 3W90) or 20 degrees (1W20 vs 3W20), data shown in Figures 6 and 7.

Study Design

Approval for this study was obtained from the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. 128 male Sprague-Dawley rats at approximately 16 weeks of age (400–450g; n=140; Charles River Laboratories; Malvern, PA) were divided into eight groups (n=16/group). Animals were housed in a conventional facility with 12 hour light/dark cycles and were fed standard chow and provided water ad libitum. Each treatment group (n=16/group) began with 2 weeks of treadmill training (up to 60min at 10m/min on a flat treadmill, 5 days per week). Animals were anesthetized (isoflurane) and underwent surgery using sterile techniques, including blunt transection of the right Achilles tendon midsubstance, resection of the central portion of the plantaris tendon to prevent internal splinting, and skin closure with 4–0 Vicryl in a figure-of-eight fashion. Pain control consisted of a single pre-operative dose of buprenorphine (0.05 mg/kg) followed post-operatively by a single dose of buprenorphine sustained release, (1.0mg/kg). After surgery, animals were immediately placed in casts set at one of three possible angles: full plantarflexion (160° tibiopedal angle, n=48 including 32 from our previous study19), full dorsiflexion in the anatomic sitting position (20° tibiopedal angle, n=32), or mid-point (90° tibiopedal angle, n=48). Within each angle grouping, animals were additionally assigned to either one week of immobilization (1W) or three weeks of immobilization (3W). Two groups assigned to 3W underwent manipulation on the 11th day of their 3 week immobilization period (160° to 90°, i.e. “160–90”; 90° to 20°, i.e. “90–20”) to simulate current clinical treatment of increasing dorsiflexion during a period of immobilization.17 The study design is outlined in Figure 1B–D, with study groups arranged by hypothesis (note that some groups are used to test more than one hypothesis). Data to address each hypothesis are grouped in 2 figures per hypothesis (Figures 2 and 3 to address hypothesis 1, Figures 4 and 5 to address hypothesis 2, Figures 6 and 7 to address hypothesis 3). Development of immobilization techniques on rat carcasses included validation of immobilization angles with fluoroscopy (Fig. 1A). The 1W160 and 3W160 groups used in this study were taken from our previously published work.19 Consistency and uniformity in splinting techniques across the study was ensured through rigorous training procedures and detailed documented protocols. Throughout the time of immobilization, limbs were evaluated for swelling or irritation, and animals were inspected daily to confirm that casts remained in place and that limb circulation was maintained. Casts were replaced at a minimum of every seven days to inspect underlying skin with the animal under anesthesia using an oscillating cast saw (HEBU Medical; Germany) for removal. After the assigned period of immobilization, casts were removed and animals were permitted cage activity for one week before a gradual progression back to 60 minutes of treadmill activity per day over the following week (10, 20, 30, 45, and 60 minutes respectively over 5 days of re-training), followed by 60 minutes of running at 10m/min on a flat treadmill, 5 days per week until the time of sacrifice. All animals were euthanized at 6 weeks post-injury.

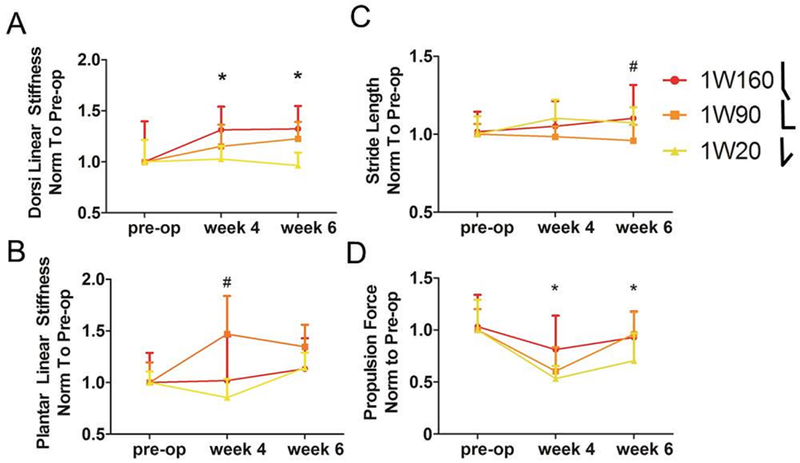

Figure 2. Immobilization in Dorsiflexion Decreases Joint Function.

Torque-angle data from passive ankle testing was fit with a bilinear curve to calculate joint stiffness in the toe and linear regions. Differences in ankle function after immobilization for one week at 90° and 20° compared to 160° include (A) decreased post-operative linear region stiffness in dorsiflexion after dorsiflexed (1W20) immobilization and (B) decreased linear region stiffness in plantarflexion after plantarflexed (1W160) immobilization. Quantitative ambulatory assessment also identified increases in (C) stride length 6 weeks after surgery, and in (D) propulsion force 4 weeks after surgery in animals placed in plantarflexed (1W160) immobilization. 1W160, one week of immobilization at 160°, red; 1W90, one week of immobilization at 90°, orange; 1W20, one week of immobilization at 20°, yellow. All values were normalized to measurements taken one day prior to surgery (pre-op). Data is represented as mean+SD. *p<0.025 for 1W160 and 1W20; # p<0.025 for 1W160 and 1W90.

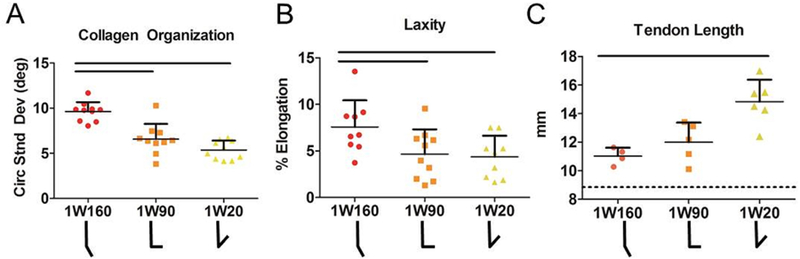

Figure 3. Immobilization in Dorsiflexion Increases Tendon Length.

High frequency ultrasound identified (A) decreased circular standard deviation indicating increased collagen alignment after more dorsiflexed immobilization for one week (1W90 and 1W20). Fatigue parameters were also improved for these groups including (B) laxity. Tendons immobilized in dorsiflexion (1W20) were (C) significantly longer than those immobilized in full plantarflexion (1W160). Dotted line in C shows average uninjured tendon length (8.9 mm). 1W160, one week of immobilization at 160°, red; 1W90, one week of immobilization at 90°, orange; 1W20, one week of immobilization at 20°, yellow. Data is represented as mean+SD. Significance (p<0.025) is indicated with solid black lines.

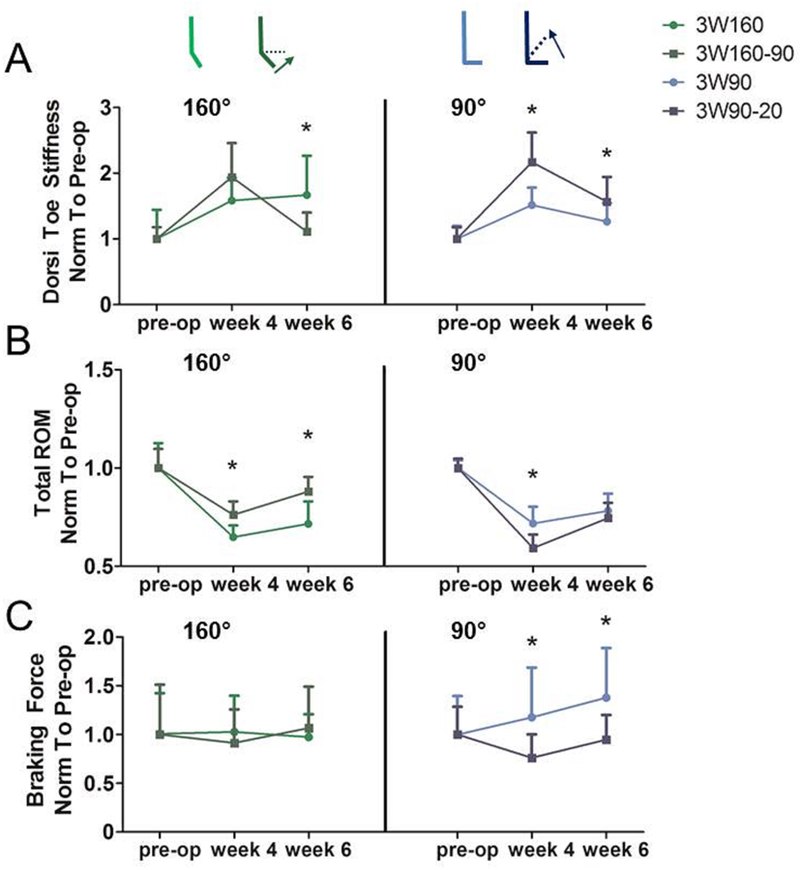

Figure 4. Manipulation of Ankle Angle From Plantarflexion to a More Dorsiflexed Position Improves Function Six Weeks After Injury.

Torque-angle data from passive ankle testing was fit with a bilinear curve to calculate joint stiffness in the toe and linear regions. Manipulating ankle angle through dorsiflexion during three weeks of immobilization (A, left) led to decreased toe region stiffness 6 weeks post-injury when the starting angle was 160°, but (A, right) increased toe region stiffness when the starting angle was 90°. Likewise, manipulating the ankle angle (B, left) resulted in increased total range of motion (ROM) when the starting angle was 160° but (B, right) decreased total range of motion when the starting angle was 90°. Quantitative ambulatory assessment (C, right light blue) also identified increases in braking force when ankles were immobilized at 90° for three weeks. 3W160, three weeks of immobilization at 160°, light green; 3W160–90, three weeks of immobilization starting at 160° and moving to 90° at 11 days post-injury, dark green; 3W90, three weeks of immobilization at 90°, light blue; 3W90–20, three weeks of immobilization starting at 90° and moving to 20° at 11 days post-injury, dark blue. All values were normalized to measurements taken one day prior to surgery (pre-op). Data is represented as mean+SD. *p<0.05.

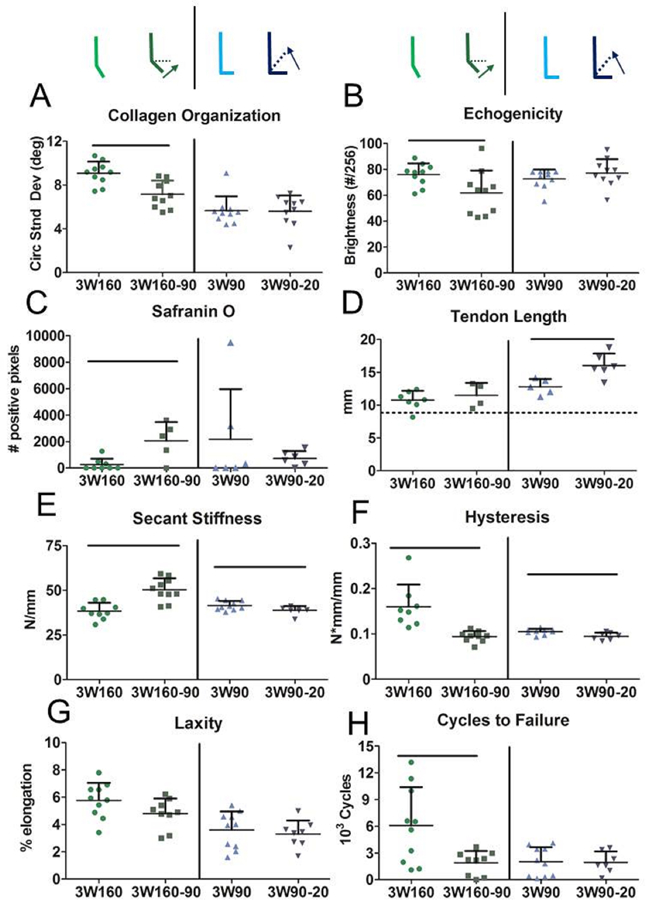

Figure 5. Manipulation of Ankle Angle From Plantarflexion to a More Dorsiflexed Position Improves Tendon Fatigue Properties Six Weeks After Injury.

High frequency ultrasound identified (A) decreased circular standard deviation indicating increased collagen alignment and (B) decreased echogenicity when immobilization consisted of manipulation of ankle angle from 160° to 90° over three weeks. This manipulation also (C) increased proteoglycan content as measured by positive Safranin O staining. Manipulation from 90° to 20° (D) significantly increased tendon length compared to constant mid-point immobilization. Manipulation (E) had angle-dependent effects on secant stiffness and (F) decreased hysteresis during cyclic fatigue testing but (G) did not impact tendon laxity. Manipulating ankle angle from 160° to 90° over three weeks (3W160–90) (H) decreased tendon cycles to failure compared to consistent immobilization at 160° (3W160). Dotted line in D shows average uninjured tendon length (8.9 mm). 3W160, three weeks of immobilization at 160°, light green; 3W160–90, three weeks of immobilization starting at 160° and moving to 90° at 11 days post-injury, dark green; 3W90, three weeks of immobilization at 90°, light blue; 3W90–20, three weeks of immobilization starting at 90° and moving to 20° at 11 days post-injury, dark blue. Data is represented as mean+SD. Significance (p<0.05) is indicated with solid black lines.

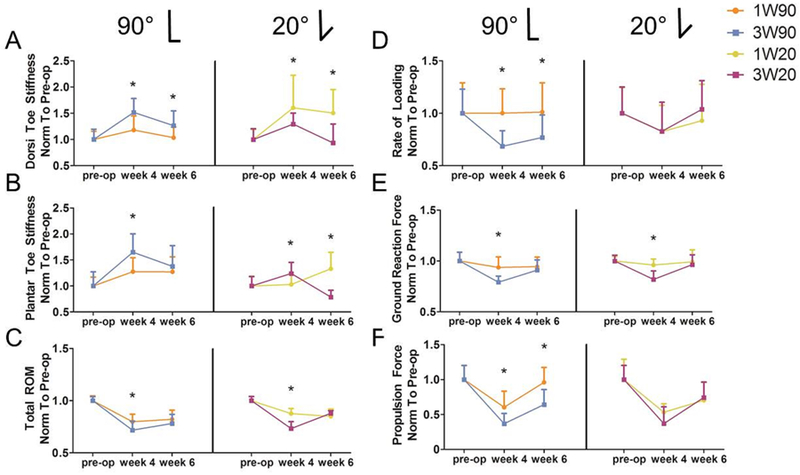

Figure 6. Earlier Return to Activity after Dorsiflexion Immobilization (90° or 20°) Improves Ankle Function Six Weeks After Injury.

Torque-angle data from passive ankle testing was fit with a bilinear curve to calculate joint stiffness in the toe and linear regions. Dorsiflexion toe stiffness (A, left) was increased in tendons immobilized for three weeks at 90° (3W90) compared to only one week (1W90), but (A, right) was decreased in tendons immobilized for three weeks at 20° (3W20) compared to only one week (1W20). Similarly, plantarflexion toe stiffness (B, left) was increased in tendons immobilized for three weeks at 90° (3W90) compared to only one week (1W90), but (B, right) was decreased for in tendons immobilized for three weeks at 20° (3W20) compared to only one week (1W20). Animals immobilized for only one week (C) had increased total ROM 4 weeks post-injury compared to three week immobilization, regardless of immobilization angle. Quantitative ambulatory assessment identified negative effects of longer immobilization time, including (D) decreased rate of loading after three weeks at mid-point immobilization (3W90), (E) decreased ground reaction forces in both 3W groups compared to 1W, and (F) decreased propulsion force after three weeks at mid-point immobilization (3W90). 1W90, one week of immobilization at 90°, orange; 3W90, three weeks of immobilization at 90°, light blue; 1W20, one week of immobilization at 20°, yellow; 3W20, three weeks of immobilization at 20°, purple. All values are normalized to measurements taken one day prior to surgery (pre-op). Data is represented as mean+SD. *p<0.05.

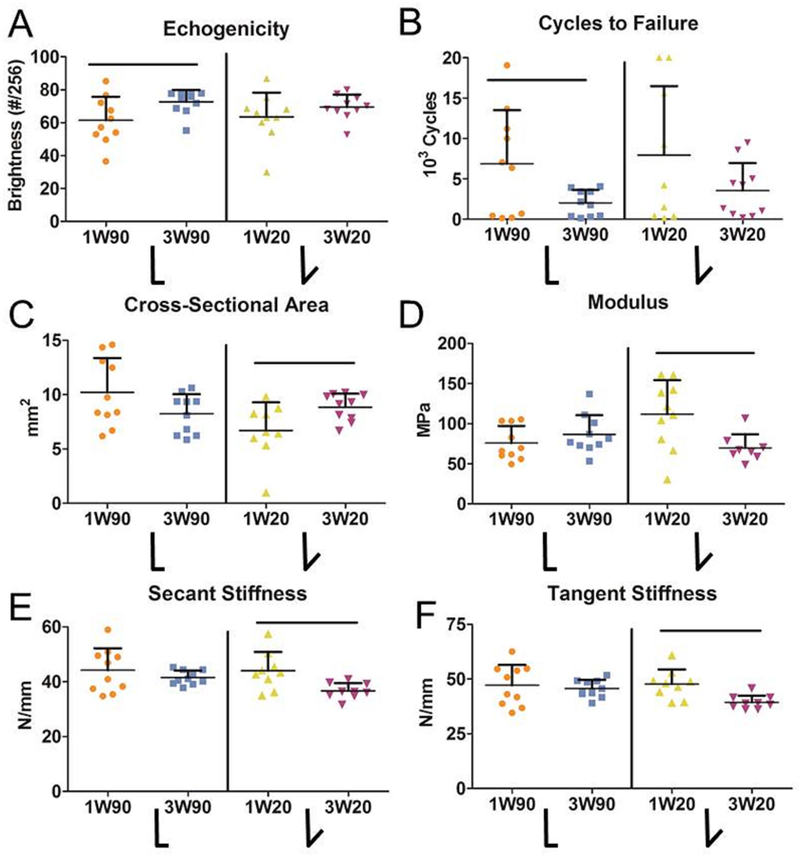

Figure 7. Earlier Return to Activity after Dorsiflexion Immobilization (90° or 20°) Improves Tendon Mechanical Properties Six Weeks After Injury.

High frequency ultrasound identified (A) increased echogenicity after three weeks of immobilization at 90° (3W90) compared to only one week at 90° (1W90). However, (B) tendons immobilized for three weeks at 90° (3W90) had decreased cycles to failure compared to only one week of immobilization (1W90). Three weeks of immobilization at 20° (3W20) had detrimental effects including (C) increased tendon cross-sectional area, (D) decreased modulus measured during the ramp to 35N, and (E) decreased secant stiffness and (F) tangent stiffness measured during cyclic fatigue testing. 1W90, one week of immobilization at 90°, orange; 3W90, three weeks of immobilization at 90°, light blue; 1W20, one week of immobilization at 20°, yellow; 3W20, three weeks of immobilization at 20°, purple. Data is represented as mean+SD. Significance (p<0.05) is indicated with solid black lines.

In vivo Functional Evaluation

Ankle Range of Motion and Stiffness:

Passive ankle joint range of motion (ROM) and stiffness were quantified using a custom torque cell and orientation device22 on anesthetized animals (n=16/group) with LabView software (National Instruments; Austin, TX) pre-injury (pre-op), 4 weeks (4W), and 6 weeks post-injury (6W, immediately prior to euthanasia). A total of two trials, consisting of three plantarflexion/dorsiflexion cycles each, were measured on each testing day. Functional ankle joint properties (toe and linear ankle stiffness; ankle ROM) for both dorsiflexion and plantarflexion were evaluated using custom MATLAB software in a blinded fashion (Mathworks; Natick, MA). The total ROM was calculated by adding the average of the three maximum values for both dorsiflexion and plantarflexion. The zero angle was defined identically to the convention in humans (90° tibiopedal angle). A bilinear fit was applied to the torque-angle data to calculate both toe and linear regions of joint stiffness for both dorsiflexion and plantarflexion, with the two movements distinguished by the angle of zero torque.22 Data was normalized to the average pre-op value for each group.

Quantitative Ambulatory Assessment:

Ground reaction forces and spatiotemporal patterns of the injured hindlimb were quantified using an instrumented walkway, consisting of two 6 degrees-of-freedom load/torque cells and a dorsal view camera to provide non-invasive in-vivo measures of limb function as previously described.23 Each animal was acclimated to the walkway on four separate days prior to collecting formal measurements. Data was collected prior to injury (pre-op), as well as 4 weeks (4W) and 6 weeks (6W, immediately prior to euthanasia) post-injury. All data were analyzed in a blinded fashion using custom MATLAB software to calculate the ground reaction forces (lateral, braking, propulsion, vertical) and spatiotemporal (step width, stride length, velocity) parameters of the injured limb. All animals were weighed at the time of each ambulatory assessment, and ground reaction forces were normalized to percent animal body-weight (%BW) at time of measurement. Data were then normalized to the average pre-op value for each group.

Tendon Specimen Preparation

Six weeks post-injury (keeping time post-injury consistent, but with varying immobilization time and subsequent return to activity time), animals were euthanized and tendons from all groups were randomized and prepared by a single blinded dissector for high-frequency ultrasound and mechanical testing (n=10/group). The Achilles tendon-foot complex was carefully removed en bloc, and the tendon was fine dissected under a stereomicroscope (Leica Microsystems, Inc.; Buffalo Grove, IL) to remove any remaining muscle, non-tendinous connective tissue, and any residual plantaris tendon. Cross sectional areas of tendons were then measured using a custom laser-based device.24,25 Groups taken from our previous publication did not have residual plantaris tendon dissected.19 India ink (Chartpak, Inc.; Leeds, MA) was used to place stain dots on the Achilles tendon for optical tracking during mechanical testing. The calcaneus-foot complex was embedded in PMMA and the free end of the tendon was sandwiched between two pieces of sandpaper using superglue (Loctite; Westlake, OH) to create a tendon gauge length of 12mm. These samples underwent high-frequency ultrasound followed by mechanical testing (described below).

High-Frequency Ultrasound (HFUS) and Evaluation

Using samples prepared as described above, tendons were placed in a custom fixture with the tendon at 90° to the foot in a 1x phosphate-buffered saline bath. Tendons were loaded at 1N while a series of sagittal B-mode HFUS images were acquired at 0.5mm increments using a 40MHz scanner (MS550D; VisualSonics, CA). Using MATLAB, the average gray scale brightness in an image [range: 0–255] was evaluated for the tendon injury region of the four centermost sagittal HFUS images for each tendon. This value was reported as mean echogenicity. Regions that had shadowing due to calcification were not included in the analysis. Custom MATLAB software was also used to analyze the fascicle/fiber organization of the within the ex vivo images. A series of linear kernels were applied at various angles (from 0–180° in 10° increments) to create a stack of images for each angle.26 The resulting intensity vs. angle data was fit with a power-law function in order to determine phase angle and magnitude at each grid point. The distribution of phase angles across all grid points was quantified by the circular standard deviation (CSD) of these angles.26 Mean alignment across four of the centermost sagittal HFUS images (spaced at 0.5mm) was evaluated for the injury region using MATLAB.

Mechanical Testing

Fatigue testing of Achilles tendons (n=10/group) was performed as previous described.18 Briefly, foot-tendon complexes were mounted using custom aluminum fixtures to place the foot and Achilles tendon perpendicular to each other in order to approximate physiologic loading, maintaining a consistent gauge length for all specimens; all tested specimens contained the injury site. The fixtures were attached to a testing frame (Electropuls E3000, Instron; Norwood, MA) using a 250N load cell. Specimens remained submerged in a 37°C 1x PBS bath. The mechanical testing protocol consisted of: preloading (0.1N); preconditioning (0.5–1.5% strain at 0.25 Hz for 30 cycles); stress relaxation (6% strain) for 10min; a dynamic frequency sweep (0.125% strain amplitude, at 0.1, 1, 5, and 10Hz for 10 cycles each); a ramp at 2% strain/s to 35N (used to calculate quasistatic parameters); and fatigue testing (5–35N at 2 Hz; which corresponds to 10–70% of ultimate failure load) using a sinusoidal waveform until failure. During loading, force and displacement data were acquired using the WaveMatrix (Instron; Norwood, MA) data acquisition software and analyzed using custom MATLAB code. Images were acquired during testing to track optical strain (20 microns/pixel) during the initial ramp to peak load (2 images/sec) using a Basler a102F camera (Basler; Exton, PA) and Nikon AF Micro-NIKKOR 200mm lens positioned outside of the PBS bath, perpendicular to the tendon to include within the capture frame the potted calcaneus, the length of the tested tendon, and the tendon grip attached to the Instron actuator. Evaluated metrics include Achilles tendon percent relaxation, dynamic modulus, optical linear modulus, stiffness, hysteresis, laxity, secant and tangent stiffness, fatigue modulus, trilinear fits through the triphasic strain-cycle response to fatigue loading, and cycles to failure.18,22,27–29 Fatigue parameters were calculated at 5, 50, and 95% of fatigue life (defined by corresponding percentage of cycles to failures) to describe the three phases of fatigue behavior. Only 50% fatigue life parameters are compared in figures and manuscript text; 5 and 95% parameters are noted in Supplemental Tables. If samples remained intact at the end of the ramp to 35N, they were able to continue into the fatigue cycling portion of the test. If tendons did not withstand the initial ramp to begin fatigue testing, fatigue parameters were not calculated, as we were unable to collect fatigue data for these samples. All groups had n=8–10 that were able to undergo fatigue assessment. Tendons from previously published groups (1W160 and 3W160) had a larger cross-sectional area due to differences in dissection, and were therefore excluded from comparisons of area dependent metrics (noted as “no data” in Supplemental Tables).

Histology

Achilles tendons were harvested at the time of animal sacrifice (n=6/group), and were processed by standard paraffin procedures and previously described assessments.18–20,30 Cell density and nuclear shape on H&E stained images were independently graded using a scale of one to three for cellularity (1, low; 2, moderate; 3, high) and one to four for nuclei shape (1, spindle shaped; 2, mixed/spindle; 3, mixed/rounded; 4, rounded). Safranin O-positive staining area, as a marker of glycosaminoglycan (GAG) content, was assessed with ImageJ (NIH, v1.48) after images were cropped to remove the calcaneus and fibrocartilaginous tendon insertion.30 Tendon length was assessed from full length images of H&E-stained sections, and was defined as the distance from the calcaneal insertion of the Achilles tendon, traveling proximally through the midsubstance of tendon material to the most distal aspect of the dorsal myotendinous junction.18,19 Measurements from at least two sections per sample were averaged together for analysis of each parameter. Representative images and a representative length measurement are shown in Figure S–1.

Statistical Analysis

Using our previous rat Achilles mechanical data31, an a priori power analysis indicated that for 80% power, 10 tendons were needed per group for mechanical assays. All data was collected in a blinded fashion with the exception of functional assays which could not be blinded; all data, however, was analyzed in a blinded fashion. Comparisons were made to compare the effects of increased dorsiflexion during immobilization for 1 week to the standard plantarflexed position (1W160 vs. [1W90 or 1W20], Fig. 1A), the effects of manipulation of ankle angle during immobilization starting from 160 degrees (3W160 vs 3W160–90) or 90 degrees (3W90 vs 3W90–20) (Fig. 1B), and the effects of dorsiflexion immobilization duration at 90 degrees (1W90 vs 3W90) or 20 degrees (1W20 vs 3W20) (Fig. 1C). Data normality was evaluated with Shapiro–Wilk tests (SPSS, IBM SPSS, Inc., Version 20, Armon, NY). Normally distributed data were evaluated with one-way ANOVAs or two-tailed Student’s t-tests (HFUS, mechanical properties, tendon length, Safranin O quantification), with the exception of longitudinally-collected functional data which were assessed using two-way ANOVAs. ANOVAs resulting in significant relationships (α ≤ 0.05) were analyzed with post-hoc two-tailed Student’s t-tests with Bonferroni corrections for multiple comparisons. Non-normally distributed data sets (histological scoring metrics) were evaluated with non-parametric Mann-Whitney U tests.

RESULTS

All numeric data are detailed in Supplemental Tables 1-4. Fatigue parameters measured at 50% of tendon fatigue life are presented in the data below.

Immobilization in Dorsiflexion Increases Tendon Length and Decreases Limb Function

Ankles immobilized in full plantarflexion for one week (1W160) displayed increased linear stiffness into dorsiflexion compared to ankles immobilized in full dorsiflexion (1W20, Fig. 2A), but decreased linear stiffness into plantarflexion compared to ankles in mid-point immobilization (1W90, Fig. 2B). Despite differences in passive ankle stiffness, there were no effects of immobilization angle on joint ROM (Table S-1). Stride length (Fig. 2C) and propulsion force (Fig. 2D) were increased for animals immobilized in full plantarflexion (1W160). Ultrasound analysis indicated increased matrix alignment (decreased collagen angle deviation) in the 1W20 and 1W90 groups compared to 1W160 group (Fig. 3A). Mid-point or full dorsiflexion immobilization also led to decreased laxity (Fig. 3B) compared to plantarflexion immobilization. However, full dorsiflexion (1W20) increased tendon length when compared to 1W90 and 1W160 (Fig. 3C).

Manipulation of Ankle Angle From Plantarflexion to a More Dorsiflexed Position Improves Function And Tendon Fatigue Properties Six Weeks After Injury

Manipulating ankle angle from full plantarflexion to mid-point (160–90) over a period of three weeks decreased dorsiflexion toe stiffness (Fig. 4A) and increased ankle ROM (Fig. 4B) when compared to ankles maintained at 160°. No gait parameters were affected after 160–90 manipulation. However, manipulating ankle angle from 90° to 20° over the same time period had detrimental effects on ankle function, increasing toe region ankle stiffness (Fig. 4A) and decreasing ROM (Fig. 4B) compared to ankles maintained at 90°. 90–20 manipulation yielded mixed results, decreasing braking force (Fig. 4C) but increasing the rate of loading after injury (Table S-2). HFUS analysis revealed that 160–90 manipulation increased collagen alignment (Fig. 5A) but decreased tendon echogenicity (Fig. 5B). 160–90 manipulation also increased Safranin O positive staining (Fig. 5C). It did not affect tendon length (Fig. 5D). Additionally, this group showed increased tendon stiffness (Fig. 5E) and decreased hysteresis (Fig. 5F), but there were no differences in tendon laxity (Fig. 5G) compared to those that remained at 160°. However, manipulation from full plantarflexion to mid-point (160–90) decreased cycles to failure (Fig. 5H). Few differences in ex vivo tendon properties existed between 3W90–20 manipulated animals and 3W90 animals, but significant changes include increased tendon length (Fig. 5D), decreased stiffness (Fig. 5E), and decreased hysteresis (Fig. 5F).

Earlier Return to Activity after Dorsiflexion Immobilization (90° or 20°) Improves Ankle Function and Tendon Mechanical Properties Six Weeks After Injury

When comparing time of immobilization at 90°, ankles immobilized for three weeks had increased toe region stiffness (Fig. 6 A, B) and decreased ROM (Fig. 6C) compared to those immobilized for only one week. Additionally, 3W90 animals demonstrated diminished gait quality compared to 1W90, with decreased rate of loading (Fig. 6D), decreased ground reaction force (Fig. 6E), and decreased propulsion force (Fig. 6F) compared to 1W90. When ankles were immobilized at 20°, three weeks of immobilization led to decreased toe region stiffness at 6 weeks post-op (Fig. 6A, B) but a decreased total ROM at 4 weeks (Fig. 6C) compared to the 1W20 group. 3W20 animals also demonstrated decreased ground reaction forces and decreased stride length at 4 weeks compared to 1W20 (Fig 6E; Table S-2). Animals immobilized at 90° for 3 weeks (3W90) demonstrated increased echogenicity (Fig. 7A) and decreased cycles to failure (Fig. 7B) compared to those immobilized for 1 week (1W90). There were no differences in alignment or histological properties between groups immobilized for 1 and 3 weeks at 90° (Table S-4). Immobilization at 20° for 3 weeks (3W20) increased tendon cross sectional area (Fig. 7C), and decreased modulus (Fig. 7D), secant stiffness (Fig. 7E), tangent stiffness (Fig. 7F), and fatigue modulus (Table S-3) compared to 1W20. There were no differences in HFUS or histological properties with increased time in the 20° splint (Table S-4).

DISCUSSION

Although recent clinical and basic science studies support the use of non-operative treatment and early active rehabilitation for Achilles tendon ruptures,3,13, 18, 19 the role of immobilization angle on tissue level healing has not been investigated. We used a rat model of non-operative repair of Achilles tendon rupture to evaluate the effects of both immobilization angle and immobilization time on the functional, mechanical, structural, and histological properties of Achilles tendons six weeks post injury.

Overall, Achilles tendon healing was influenced by the angle of ankle immobilization. Importantly, and as hypothesized, significantly increased Achilles tendon elongation was only seen if the ankle was immobilized at maximal dorsiflexion (20°) for 1 or 3 weeks. Clinical data suggest that Achilles tendon lengthening can be correlated with poor clinical outcomes and enduring changes in ankle dorsiflexion.11,32 In our model, even short immobilization (1 week) at 20° led to a significantly longer tendon than did immobilization in full plantarflexion (160°), and this corresponded with diminished propulsion force off the injured limb during ambulation post-injury. This finding suggests that dorsiflexed immobilization, or delayed treatment, may be associated with reduced push-off strength in end-range plantarflexion, mirroring an outcome seen clinically in humans.33 Although no statistical comparisons were made to uninjured tendon length, tendons immobilized in full plantarflexion remained closest in length to uninjured controls (Fig. S-1), as expected. However, tendons immobilized in more dorsiflexed positions (90° and 20°) had increased collagen organization, possibly due to increased tendon tension during the immobilization period. Indeed, previous work has shown that mechanical loading on tendons can induce tendon cell activation, the production of growth factors, tensional homeostasis, remodeling, and nuclear strain transfer.34–36

As hypothesized, both tendon structure and fatigue properties were significantly improved after manipulation from 160° to 90°, including increased matrix alignment and tendon stiffness, and decreased hysteresis. Additionally, ankle manipulation from 160° to 90° did not result in increased tendon length, and had positive effects on passive ankle motion when compared to those that remained in a fully plantarflexed position for three weeks. Loss of homeostatic tension (stress deprivation) has been shown to have detrimental effects on tendon development, homeostasis, and healing.37–39 As discussed above, immobilizing the ankle in a more dorsiflexed position may apply a static load to the ruptured tendon, thereby improving collagen production and matrix alignment and increasing fatigue resilience. However, these manipulated tendons (3W160–90) also showed decreased echogenicity and increased proteoglycan content as measured with Safranin O staining. Changes in echogenicity may be due to collagen fibers moving out of the plane of the ultrasound, or the differences in the loading environments between ex vivo ultrasound and mechanical testing. Ultrasound-based studies have demonstrated the complexity of measuring echogenicity in the Achilles tendon due to the spiraling, non-linear fibers and twisting anatomy.40, 41 Lower echogenicity could also be related to increased proteoglycan content, as tendon rupture can increase the presence of proteoglycan-rich inclusions.42 Ankle manipulation may further increase proteoglycan expression, possibly as an adaptation to increase tissue hydration to facilitate nutrient and metabolite diffusion.42–44

Early re-rupture during non-operative Achilles rehab has been attributed to “an adequate trauma,”45 which may parallel the conditions of our 3W90–20 group. Similar to 20° immobilization (1W20), manipulation of the ankle from 90° to 20° resulted in a significantly longer Achilles tendon than maintaining the ankle at 90°. This elongation occurred despite early healing in a more plantarflexed position (90°, a position in which tendons did not significantly elongate), suggesting that the scar tissue remains ductile at this point. Although the tendons were longer at 6 weeks post-injury in 3W90–20 animals, this group also demonstrated increased ankle stiffness in dorsiflexion and decreased total range of motion. Additionally, braking force for 3W90–20 animals was decreased compared to 3W90 animals at both post-operative time points which, together with passive mobility metrics, may be due to reduced ankle mobility. Together with diminished fatigue properties, this data does not support the manipulation of the ankle from a mid-point angle into full dorsiflexion during immobilization. We speculate that although this angle change in the context of remobilization (such as for 1W90 animals after cast removal) may initiate advantageous matrix production and remodeling due to tendon loading, an abrupt angle change followed by continued immobilization may damage newly formed scar tissue or impede early healing processes.

Previous work supports reduced immobilization time when immobilized in full plantarflexion.18–20 Assessing the variable of time in the context of a more dorsiflexed position extends this finding to other immobilization angles. Increases in passive motion toe stiffness in the 1W20 group compared to 3W20 did not correlate with a decreased range of motion, and 1W20 animals had increased ground reaction force at 4 weeks compared to the 3W20 group. Many functional properties were also improved for 1W90 compared to 3W90. Fatigue testing also supports the concept that early activity leads to better recovery. 3W90 tendons survived 70% fewer fatigue cycles before failure than 1W90 tendons. Similar to unexpected echogenicity differences in manipulated tendons, the increase in echogenicity in 3W90 compared to 1W90 may correspond with a change in tissue matrix density or protein content.46 Further analysis of this healing tissue would aim to elucidate the contribution of collagen fibril formation, other extracellular matrix proteins, and matrix remodeling to healing tendon material properties. No histological properties measured in this study demonstrated differences between these groups.

This study is not without limitations. Despite steps to maximize clinical relevance through the use of immobilization and rehabilitation protocols that were designed to mimic rehabilitation in humans, some elements of the study may not reflect a human environment. Most notably, the “resting angle” of a sitting rat is more dorsiflexed than in a human. Disparities in this loading environment likely exist between species including compressive forces of the calcaneus on healing tissue47 and differential loading/unloading on both tendon and muscle. Furthermore, the open tendon transection does not fully mimic an injury being treated non-operatively. In addition, use of data from previously published work in conjunction with data collected for the additional groups defined in this manuscript could introduce data variation between groups. However, the consistent use of carefully developed and documented protocols across all procedures, as well as the presence of several coinciding authors across all experimental groups ensured consistency in data collection and interpretation. It should also be noted that this study did not include uninjured control data except in the context of tendon lengthening. The objective of this study was to determine best practices for tendon recovery after injury. For functional properties, our pre-operative values serve as uninjured controls to which post-operative values recover back towards over time. However, it is known that mechanical properties of injured tendons do not recover back to uninjured values, and in this case makes comparison between injured and uninjured less meaningful, justifying the study design presented.9 Finally, the data for injured tendons were obtained at a relatively early phase of healing, and at only one post-operative time point for ex vivo metrics, and it is likely that the functional and mechanical properties will continue to evolve over time.19 Because immobilization and return to activity/exercise allotments within the six week study time course varied, it is difficult to truly separate the effects of immobilization time versus the effects of return to activity time. Further work is needed to evaluate the interaction of tendon biology with altered mechanical environments, which could improve the treatment of injuries including that of the Achilles tendon.

In conclusion, this study begins to uncover the effects of immobilization angle on early tendon healing to better understand evolving non-operative treatments for acute Achilles tendon injuries. We evaluated the role of immobilization angle and length of time on functional, ultrasound-based, mechanical, and histological measures following acute Achilles tendon rupture. This study provides evidence that positions of increased dorsiflexion can aid in passive and active functional properties, and can improve tendon structural, mechanical, and material properties during early fatigue loading. However, these effects should be evaluated in the context of the risk of significant tendon lengthening and weakening seen with excessive dorsiflexion. Future studies could evaluate whether these changes are due to the static position of the ankle or increased muscle activation and locomotion given the functional position of immobilization. Additionally, assessing additional dorsiflexion angles between 90° and 20° would be informative for determining the most ideal position.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1. (Top) Representative full-length tendon images taken of 7 um sagittal section from the midline of the tendon through the injury region and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Yellow line in 1W160 image represents technique used to measure tendon length, starting at the fibrocartilage insertion and ending at the beginning of the myotendinous junction. Black scale bar on bottom right: 2 mm. (Bottom) All tendon length data plotted together. Black bars indicate significant differences (p<0.05) between groups that were compared in this study.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was funded by the NIH/NIAMS supported Penn Center for Musculoskeletal Disorders (P30 AR069619) and the Orthopaedic Research Education Foundation, via a Resident Clinician Scientist Training Grant. We thank Dr. Corinne Riggin for assistance with ultrasound imaging.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wang D, Sandlin MI, Cohen JR, et al. 2015. Operative versus nonoperative treatment of acute Achilles tendon rupture: An analysis of 12,570 patients in a large healthcare database. Foot Ankle Surg 21:250–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cukelj F, Bandalovic A, Knezevic J, Pavic A, Pivalica B, Bakota B. 2015. Treatment of ruptured Achilles tendon: Operative or non-operative procedure? Injury 46 Suppl 6:S137–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lantto I, Heikkinen J, Flinkkila T, et al. 2016. A Prospective Randomized Trial Comparing Surgical and Nonsurgical Treatments of Acute Achilles Tendon Ruptures. Am J Sports Med 449:2406–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sveen TM, Troelsen A, Barfod KW. 2015. Higher rate of compensation after surgical treatment versus conservative treatment for acute Achilles tendon rupture. Dan Med J 62(4):1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilkins R, Bisson LJ. 2012. Operative versus nonoperative management of acute Achilles tendon ruptures: a quantitative systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Am J Sports Med 40:2154–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raikin SM, Garras DN, Krapchev PV. 2013. Achilles Tendon Injuries in a United States Population. Foot Ankle Int 34:475–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruggeman NB, Turner NS, Dahm DL et al. 2004. Wound Complications after Open Achilles Tendon Repair: An Analysis of Risk Factors. Clin Orthop Relat Res 427: 63–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soroceanu A, Sidhwa F, Aarabi S, et al. 2012. Surgical Versus Nonsurgical Treatment of Acute Achilles Tendon Rupture, A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Trials. J Bone Joint Surg Am 94: 2136–2143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freedman BR, Gordon JA, Soslowsky LJ. 2014. The Achilles tendon: fundamental properties and mechanisms governing healing. Muscles, Ligaments and Tendons Journal 4:245–255. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gulati V, Jaggard M, Al-Nammari SS, et al. 2015. Management of Achilles tendon injury: A current concepts systematic review. World Journal of Orthopedics 6:380–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maquirriain J 2011. Achilles tendon rupture: avoiding tendon lengthening during surgical repair and rehabilitation. Yale J Biomed 84:289–300. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Young SW, Patel A, Zhu M, et al. 2014. Weight-Bearing in the Nonoperative Treatment of Acute Achilles Tendon Ruptures, A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am 96:1073–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barfod KW, Benche J, Lauridsen HB, et al. 2014. Nonoperative Dynamic Treatment of Acute Achilles Tendon Rupture: The Influence of Early Weight-bearing on Clinical Outcome, A Blinded, Randomized Controlled Trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am 96:1497–1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barfod KW, Bencke J, Lauridsen HB, et al. 2015. Nonoperative, Dynamic Treatment of Acute Achilles Tendon Rupture: Influence of Early Weightbearing on Biomechanical Properties of the Plantar Flexor Muscle-Tendon Complex-A Blinded, Randomized, Controlled Trial. J Foot Ankle Surg 54:220–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olsson N, Karlsson J, Eriksson BI, Brorsson A, Lundberg M, Silbernagel KG. 2014. Ability to perform a single heel-rise is significantly related to patient-reported outcome after Achilles tendon rupture. Scand J Med Sci Sports 24:152–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kou J 2010. AAOS Clinical Practice Guideline: acute Achilles tendon rupture. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 18:511–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Akizuki KH, Gartman EJ, Nisonson B, Ben-Avi S, McHugh MP. 2001. The relative stress on the Achilles tendon during ambulation in an ankle immobiliser: implications for rehabilitation after Achilles tendon repair. British Journal of Sports Medicine 35:329–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freedman BR, Gordon JA, Bhatt PR, et al. 2016. Nonsurgical Treatment and Early Return to Activity Leads to Improved Achilles Tendon Fatigue Mechanics and Functional Outcomes During early Healing in an Animal Model. J Orthop Res 34:2172–2180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Freedman BR, Salka NS, Morris TR, Bhatt PR, Pardes AM, Gordon JA, Nuss CA, Riggin CN, Fryhofer GW, Farber DC, Soslowsky L. 2017. Temporal Healing of Achilles Tendons After Injury in Rodents Depends on Surgical Treatment and Activity. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 25:635–647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Freedman BR, Fryhofer GW, Salka NS, Raja HA, Hillin CD, Nuss CA, Farber DC, Soslowsky LJ. 2017. Mechanical, histological, and functional properties remain inferior in conservatively treated Achilles tendons in rodents: Long term evaluation. J Biomech 56:55–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murrell GA, Lilly EG 3rd, Goldner RD, Seaber AV, Best TM. 1994. Effects of immobilization on Achilles tendon healing in a rat model. J Orthop Res 12:582–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peltz CD, Dourte LM, Kuntz AF, et al. 2009. The effect of postoperative passive motion on rotator cuff healing in a rat model. J Bone Joint Surg Am 91:2421–2429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sarver JJ, Dishowitz MI, Kim SY, et al. 2010. Transient decreases in forelimb gait and ground reaction forces following rotator cuff injury and repair in a rat model. J Biomech 43:778–782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Favata M 2006. Scarless healing in the fetus: Implications and strategies for postnatal tendon repair Thesis; University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peltz CD, Perry SM, Getz CL, Soslowsky LJ. Mechanical properties of the long-head of the biceps tendon are altered in the presence of rotator cuff tears in a rat model. J Orthop Res 2009. March;27(3):416–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Riggin CN, Sarver JJ, Freedman BR, et al. 2013. Analysis of collagen organization in mouse Achilles tendon using high-frequency ultrasound imaging. J Biomech Eng 136:021–029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Freedman BR, Sarver JJ, Buckley MR, et al. 2013. Biomechanical and structural response of healing Achilles tendon to fatigue loading following acute injury. J Biomech 47:2028–2034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Freedman BR, Zuskov A, Sarver JJ, et al. 2015. Evaluating changes in tendon crimp with fatigue loading as an ex vivo structural assessment of tendon damage. J Orthop Res 33:904–910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gordon J, Freedman B, Zuskov A, et al. 2015. Achilles tendons from decorin- and biglycan-null mouse models have inferior mechanical and structural properties predicted by an image-based empirical damage model. J Biomech 48:2110–2115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fryhofer GW, Freedman BR, Hillin CD, et al. 2016. Postinjury biomechanics of Achilles tendon vary by sex and hormone status. J Appl Physiol 121:1106–1114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang TF, Perry SM, Soslowsky LJ. 2004. The effect of overuse activity on Achilles tendon in an animal model: a biomechanical study. Ann Biomed Eng 32:336–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Costa ML, Logan K, Heylings D, Donell ST, Tucker K. 2006. The effect of Achilles tendon lengthening on ankle dorsiflexion: a cadaver study. Foot Ankle Int 27:414–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mullaney MJ, McHugh MP, Tyler TF, Nicholas SJ, Lee SJ. 2006. Weakness in end-range plantar flexion after Achilles tendon repair. Am J Sports Med 7:1120–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sharma P, Maffulli N. 2005. Tendon injury and tendinopathy: healing and repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am 87:187–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Freedman BR, Bade ND, Riggin CN, et al. 2015. The (dys)functional extracellular matrix. Biochim Biophys Acta 1853(11 Pt B):3153–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Freedman BR, Rodriguez AB, Leiphart RJ, et al. 2018. Dynamic Loading and Tendon Healing Affect Multiscale Tendon Properties and ECM Stress Transmission. Sci Rep 8:10854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Egerbacher M, Arnoczky SP, Caballero O, Lavagnino M, Gardner KL.2008. Loss of homeostatic tension induces apoptosis in tendon cells: an in vitro study. Clin Orthop Relat Res 466:1562–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schwartz AG, Lipner JH, Pasteris JD, Genin GM, Thomopoulos S. 2013. Muscle loading is necessary for the formation of a functional tendon enthesis. Bone 55:44–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Andersson T, Eliasson P, Aspenberg P. 2009. Tissue memory in healing tendons: short loading episodes stimulate healing. J Appl Physiol (1985) 107:417–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Suydam SM, Buchanan TS. 2014. Is echogenicity a viable metric for evaluating tendon properties in vivo? J Biomech 47(8):1806–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Doral MN, Alam M, Bozkurt M, Turhan E, Atay OA, Dönmez G, Maffulli N. 2010. Functional anatomy of the Achilles tendon. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 18(5):638–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Karousou E, Ronga M, Vigetti D, Passi A, Maffulli N. 2008. Collagens, proteoglycans, MMP-2, MMP-9 and TIMPs in human Achilles tendon rupture. Clin Orthop Relat Res 466(7):1577–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Batson EL, Paramour RJ, Smith TJ, Birch HL, Patterson-Kane JC, Goodship AE. 2003. Are the material properties and matrix composition of equine flexor and extensor tendons determined by their functions? Equine Vet J 35(3):314–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Snedeker JG, Foolen J. 2017. Tendon injury and repair – A perspective on the basic mechanisms of tendon disease and future clinical therapy. Acta Biomaterialia 63:18–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reito AR, Logren HL, Ahonen K, Nurmi H, Paloneva J. 2018. Risk Factors for Failed Nonoperative Treatment and Rerupture in Acute Achilles Tendon Rupture. Foot Ankle Int 39:694–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marr CM, McMillan I, Boyd JS, Wright NG, Murray M. 1993. Ultrasonographic and histopathological findings in equine superficial digital flexor tendon injury. Equine Vet J 25(1):23–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rufai A, Benjamin M, Ralphs JR. 1992. Development and ageing of phenotypically distinct fibrocartilages associated with the rat Achilles tendon. Anat Embryol (Berl) 186(6):611–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1. (Top) Representative full-length tendon images taken of 7 um sagittal section from the midline of the tendon through the injury region and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Yellow line in 1W160 image represents technique used to measure tendon length, starting at the fibrocartilage insertion and ending at the beginning of the myotendinous junction. Black scale bar on bottom right: 2 mm. (Bottom) All tendon length data plotted together. Black bars indicate significant differences (p<0.05) between groups that were compared in this study.