Abstract

The lung tissue contains a heterogeneous milieu of bronchioles, epithelial, airway smooth muscle (ASM), alveolar and immune cell types. Healthy bronchiole comprises epithelial cells surrounded by ASM cells and helps in normal respiration. In contrast, airway remodeling, or plasticity, increases surrounding of bronchial epithelium during inflammation, especially in asthmatic condition. Given the profound functional difference between ASM, epithelial, and other cell types in the lung, it is imperative to separate and isolate different cell types of lungs for genomics, proteomics, and molecular analysis, which will improve the diagnostic and therapeutic approach to treat cell specific lung disorders. Laser capture microdissection (LCM) is the technique generally used for the isolation of specific cell populations under direct visual inspection, which plays a crucial role to evaluate cell specific effect in clinical and preclinical setup. However, maintenance of tissue RNA quality and integrity in LCM studies are very challenging tasks. It is obvious to believe that the major factor affecting the RNA quality is tissue fixation method. The prime focus of this study was to address the RNA quality factors within lung tissue using the different solvent system to fix tissue sample to obtain high quality RNA. Paraformaldehyde and Carnoy’s solutions were used for fixing the lung tissue and compared RNA integrity in LCM captured lung tissue samples. To further confirm the quality of RNA we measured cellular marker genes in collected lung tissue samples from control and mixed allergen (MA) induced asthmatic mouse model using qRT-PCR technique. RNA Integrity Number showed significantly better quality of RNA in lung tissue samples fixed with Carnoy’s solution compared to paraformaldehyde solution. Isolated RNA from MA induced asthmatic murine lung epithelium, smooth muscle and granulomatous foci using LCM showed significant increase in remodeling gene expression compared to control which confirm the quality and integrity of isolated RNA. Overall, the study concludes tissue fixation solvent can alter the quality of RNA in the lung and the outcome of the results.

Keywords: Carnoy’s solution, RNA integrity, Lung tissue fixation, Laser capture microdissection, qRT-PCR

Introduction

Histological section of tissue samples under the microscope shows different characterized cells with various genetic profiles. These cells also communicate with each other to conduct the physiological function in normal and diseased condition (Arthur 2016; Corces et al. 2016; Lander 1996; MacArthur et al. 2014; Oellrich and Smedley, 2014). However, the expression levels of genes and their function would significantly vary between different cells (Antanaviciute et al. 2015; Fatkin et al. 2014; Zaidi et al. 2013). Thus, identifying the specific gene expression in a particular cell type or tissue from a specific cell type under normal and diseased conditions would significantly expand our knowledge in understanding the role of gene expression in diagnostic and therapeutic approach (Dillon et al. 2001; Domazet et al. 2008; Emmert-Buck et al. 1996). Laser capture microdissection (LCM) is a method to obtain samples containing specific cell types or cells of interest from sectioned tissue subjected to next generation sequencing (NGS) or microarray to understand the entire RNA content of a single cell for functional elucidations (Ardekani et al. 2008; Brioschi et al. 2014; Venter et al. 2001). LCM is a highly efficient and accepted technique to obtain specific cells, however, it is more vulnerable to RNAse contamination (Kerk et al. 2003). Most microdissection based mRNA expression studies have been performed on frozen tissue samples which requires more attention to avoid damage to the tissue during transportation, handling, tissue sectioning and during post-LCM RNA isolation steps. More or less all these steps are responsible for poor quality of RNA, thereby, reducing the efficacy for proceeding further downstream applications (Amini et al. 2017; Takahashi et al. 2010).

Most of the pathophysiology laboratories in clinical setup apply formalin or paraformaldehyde solution for tissue fixation. Amongst other fixatives, Carnoy’s solution is commonly used in cancer related studies because of its easy handling and more accurate staging (Luz et al. 2008). However, very limited or no clinical studies have reported the use of Carnoy’s solution in the fixation of lung tissue specimens to study downstream analysis. In order to overcome these factors, we tried to optimize the best system for tissue fixation using mouse lung samples.

The lung, a well-developed organ, is essential for terrestrial life. The lung tissue is composed of heterogeneous cells; comprises tissues such as epithelial, mesenchymal, airway smooth muscle (ASM), alveolar and immune cells. Together, these cells are responsible for the normal functioning of respiration (Hines and Sun, 2014). Chronic inflammation centrally affecting the lung airway, which impairs the functions of multiple cells, including ASM, which plays a key role in airway remodeling via altered proliferation and deposition of extracellular matrix (ECM) (Anderson 2010; Bousquet et al. 1996; O’Byrne and Inman, 2003). Airway walls are composed of more than one cell type, which alone or in combination contributes to airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR), inflammation, and remodeling, a characteristic features of asthma. It gives immense therapeutic importance to identify particular cells involved in the pathophysiology of asthma. Here, LCM technique acts as a potent tool to isolate individual cell types to understand its role in lung pathophysiology by subsequent molecular analysis.

In this study, we described the various technical approaches and updated LCM methods that we have used to isolate different lung cell types and their mRNA expression involved in airway remodeling in the lung. Furthermore, we optimized the lung fixation method using a Carnoy’s solution to maintain RNA quality and integrity in cells collected through LCM. Measured airway cellular gene expression levels by qRTPCR further confirms the quality and integrity of isolated RNA.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Murine lung tissue samples were collected from our ongoing pulmonary in vivo study, which is approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at North Dakota State University and conducted in accordance with guidelines derived from the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. We randomly selected six C57BL/6J mice each from control and mixed allergen (MA, allergic asthma model) treated groups. Animals were anesthetized using isoflurane (volatile anesthesia) for 10 sec to calm and lower the movement of mice during intra-nasal PBS or MA administration. Control mice received PBS and MA treated mice received alternate day intranasal (i.n.) administration of a mixture of equal amounts (10 μg) of ovalbumin, and extracts from Alternaria alternata, Aspergillus fumigatus and Dermatophagoides farinae (house dust mite) for 4 weeks (alternative day exposure) in PBS to induce asthma (Yarova et al. 2015). At the end of the study, animals were euthanized by using an excess dose of sodium pentobarbital (200 mg/kg). Both male and female mice were used in this study. Mice were always housed under constant temperature and 12 hour light and dark cycles provided with food and water ad libitum.

Histopathology using Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining

The left lung was ligated and the right lung was inflated with 0.8 ml of either paraformaldehyde or Carnoy’s solution and fixed overnight. Paraffin embedded tissues were cut into 6 μm sections using a tissue microtome (Leica, UK). The sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin stain (H&E) for histological observations to identify epithelium, airway smooth muscle and granulomatous foci. The stained tissues were then mounted onto a light microscope and examined at 40X magnification.

Laser Capture Microdissection (LCM)

Lung tissue was collected from mouse and fixed using two different methods: a) 4% paraformaldehyde and b) Carnoy’s fixative solution (Pereira, et al., 2015). Tissue blocks were embedded in paraffin wax and sectioned using a rotary microtome to obtain 10 μm tissue sections placed on RNAse free slides. The paraffin slides were washed in xylene for 9 minutes and ethanol for 30 seconds and then the excess xylene was blotted from the slide. LCM was performed using a Zeiss AxioImager Z1 PALM Microbeam laser capture microscope system (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY). The microdissection process was visualized with an AxioCam Icc camera coupled to a computer and controlled by a Palm-Robo software (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY). The slides were then visualized under bright-field microscopy with a 10X objective. An area of 0.3 or 1.0 mm2 was selected using the PALM-Robo software. Identified granulomatous foci and different airway cells were marked using an on screen tool of PALM MicroBeam. Laser cut was performed along the marking followed by catapulting the tissue. To confirm specific cell type, hematoxylin and eosin stained (H&E) section of same tissue was used as a reference. Catapulted cells, were collected into on RNAse free microtube containing 0.5 ml single cell PicoPure® RNA extraction buffer. Tissues were either stored temporarily at −80°C or directly used for RNA isolation. The capture success of microdissected tissue was confirmed by looking at the microtube cap under the microscope.

RNA extraction and DNase treatment

Total RNA extraction was performed by using the PicoPure® RNA Isolation Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). At first step 100 μl of extraction buffer were added in each Microtube containing tissue. For granulomatous foci 50 μl of extraction buffer were added to avoid an excessive dilution of RNA due to the small amount of microdissected tissue. Genomic DNA was removed by on-column DNAse digestion, treating bound RNA in the column for 20 min with 5 μl of DNase I diluted in 35 μl of DNAse digestion buffer (RNAse-Free DNAse Set, Zymoresearch, CA). Around 13 μl of elution buffer was pipetted directly onto the membrane of the column to elute the RNA into an RNAse free tube. Collected RNA was then stored immediately at − 80 °C.

Measurement of RNA yield and integrity

The yield and integrity of total isolated RNA from microdissected samples measured using a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies). RNA concentration of (1 μl per sample) was measured with the 2100 Bioanalyzer, then obtained concentration was divided by the tissue area value to calculate the RNA yield. Additionally, the RNA Integrity Number (RIN) was calculated by the 2100 Bioanalyzer according to an algorithm from Agilent Technologies (Kerman et al. 2006; Schroeder et al. 2006). RIN values obtained for each sample on a scale of 1–10 as an indication of RNA quality.

qRT-PCR analysis

Isolated and quantified RNA were used to synthesize cDNA using OneScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Applied Biological Materials Inc, Richmond, BC, Canada) for each sample. Bright Green Master mix qPCR kit (Applied Biological Materials Inc, Richmond, BC, Canada; Cat# MasterMix-S) protocol was followed using QuantStudio 3 qRT-PCR system as per the manufacturer’s instructions. The qRT-PCR products were loaded into a 2 % agarose gel with Gel green nucleic acid stain (Biotium), separated by electrophoresis and visualized licor D-Digit gel scanner. Following primer sequences were used to qRT-PCR analysis; For TNF-α, forward 5’-CTCCTCCTCCTGACCTTCTAATAAT-3’, reverse 5’-CTCCTCTGCCAAGTTCATATC C-3’; For α-Smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) forward 5’-GAGGCACCACTGAACCCTAA-3’, reverse 5’-CATCTCCAGAGTCC AGCACA-3’; For E-cadherin forward 5’-CACCTGGAGAGAGGCCATGT-3’, reverse 5’-TGGGAAACATG AGCAGCTCT-3’; For Fibronectin forward 5’-CGAGGTGACAGAGACCACAA-3’, reverse 5’-CTGGAGTCAAGCCAGACACA-3’; For Vimentin forward 5’-CTTGAACGGAAA GTGGAATCCT-3’, reverse 5’-GTCAGGCTTGGAAACGTCC-3’; for s16 forward 5’-GATGAAGTCGGAGCTGGTAAA-3’, reverse 5’-GGAGTGACAGGCAACTATGAA-3’. The fold changes in mRNA expression were calculated by normalization of cycle threshold [C(t)] value of target genes to reference gene s16 using the ΔΔCt method.

Statistical analysis.

All groups consisted of minimum six mice. “n” values represent number of samples from individual animals. All qRT-PCR experiments were repeated at least two times. Statistical analysis was performed using Sigma Plot (SYSTAT, San Jose, CA) software statistical package using individual one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test. All data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was tested at minimum of p<0.05 level.

Results

Effect of fixation on tissue capture success and RNA yield, and integrity after LCM

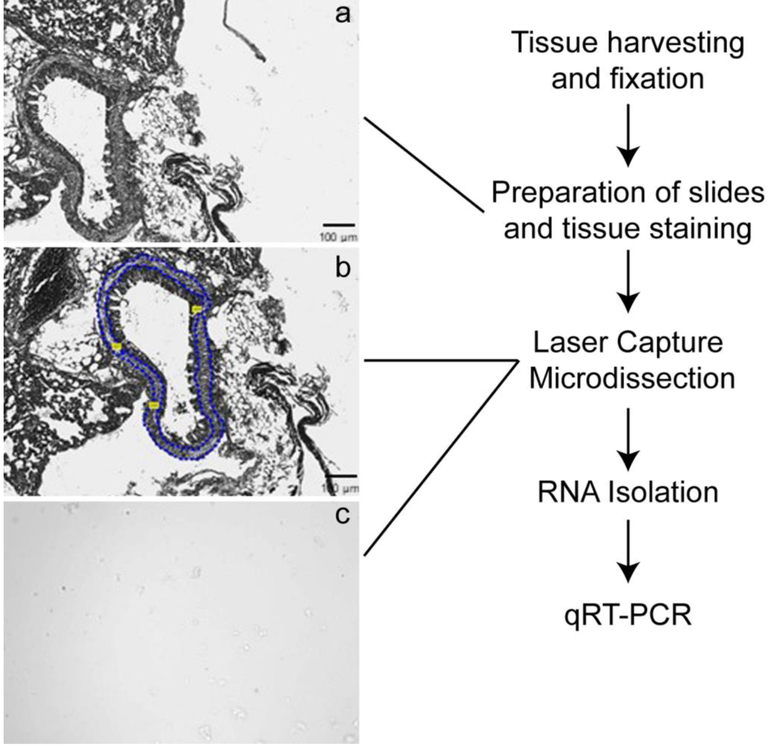

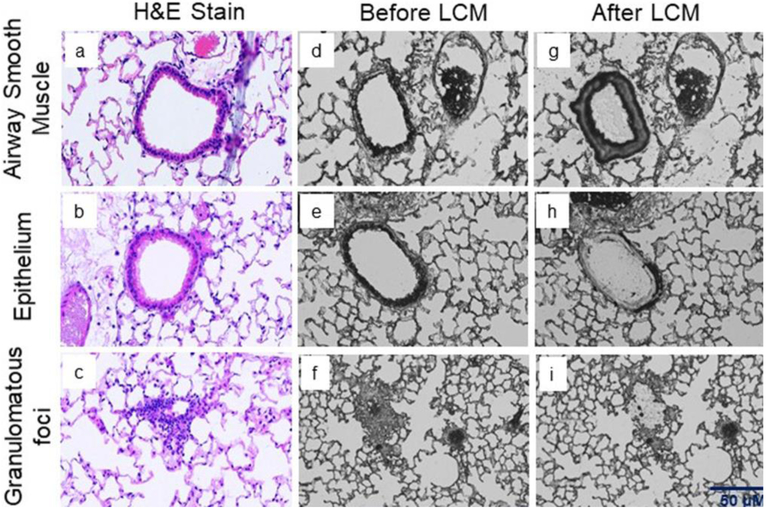

Six control (PBS only) and six mixed allergen (MA) induced asthmatic mice were used for the current study. Lung tissue samples were collected after 28 days of PBS and MA challenge. Mouse tissue samples cut to the thickness of 10 μm and mounted onto glass slides (glass or PEN-membrane coated) to isolate airway smooth muscle cells, epithelial and granulomatous foci. The workflow for this study is tissue preparation, LCM, and isolation of RNA followed by RNA analysis by qRT-PCR (Figure 1). We used PALM MicroBeam system (Zeiss) Laser Capture Microdissection system to isolate different airway cells from normal and inflammation induced lung tissue of mouse. The cells isolated was ensured microscopical observation before and after excision. Specific cell types are identified through H&E stained reference slides that are prepared from the tissue blocks used for making LCM slides (Figure 2).

Figure 1: Workflow for the Laser-capture microdissection (LCM) of lung tissue, isolation and analysis of RNA.

Airway smooth muscle (ASM) cells, epithelium and lymphatic granules from normal and inflammation induced lung tissue collected by LCM and further processed for RNA isolation. (a) Selected region of interest before LCM, (b) After LCM, (c) Collected cells in lysis buffer. H&E stained tissue section used as a reference to identify different cell types.

Figure 2: Representative images of lung tissue specimens collected after mixed allergen exposure to induce asthma.

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining used as a reference to identify different cells types; Laser capture micro-dissected murine lung tissue of (a) ASM, (b) Epithelium and (c) Granulomatous foci (10 μm section). Tissue before laser dissection (d) ASM, (e) Epithelium and (f) Granulomatous foci; Tissue after laser dissection (g) ASM, (h) Epithelium and (i) Granulomatous foci. Scale bar 50 μM.

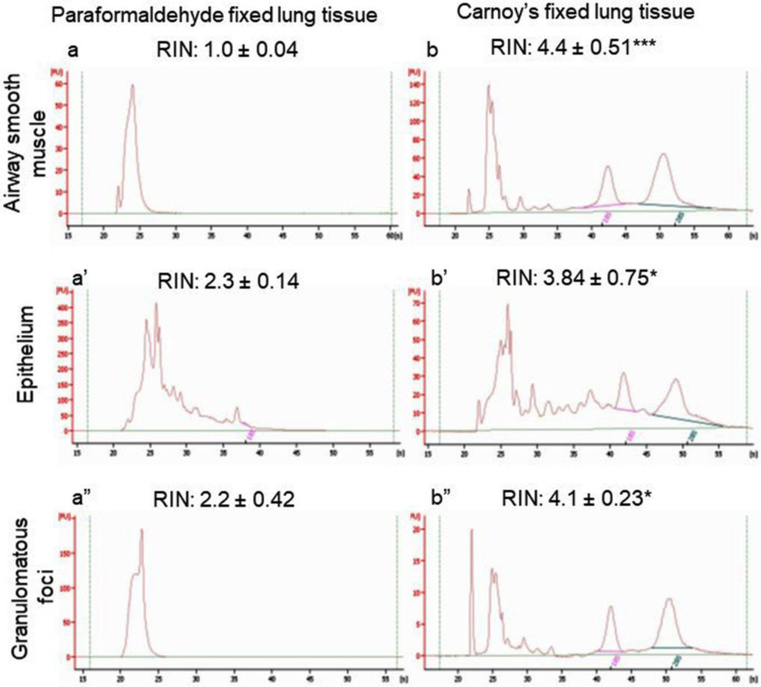

Effect of tissue fixation solvent on RNA quality

Mouse lung tissue specimens fixed into Carnoy’s or paraformaldehyde solution and LCM isolated different airway cell types used to measure RNA yield with integrity to compare the effectiveness of fixative solution. The obtained RNA yield and integrity were compared for both fixative solvent in granulomatous foci, ASM and epithelium (Figure 3). The RNA yield in Carnoy’s solution showed prominently more in comparison to paraformaldehyde (Table 1), which indicates that the tissue fixation with Carnoy’s provided better yield and more integrity.

Figure 3: RNA Integrity of specific cells isolated from LCM-derived tissue measured using Agilent bioanalyzer.

RNA integrity of (a) ASM, (a’) epithelium and (a”) Granulomatous foci from paraformaldehyde fixed lung tissue. RNA integrity of (b) ASM, (b’) epithelium and (b”) granulomatous foci from Carnoy’s fixed lung tissue. The average RIN values for different cell types shown with graphical representation. The RIN value indicates RNA Integrity Number which is better in Carnoy’s fixed tissue than paraformaldehyde fixed tissue. Data represented as Mean ± SEM of at least 06 mice per group; ***p<0.001, *p<0.01 paraformaldehyde vs Carnoy’s solution.

Table 1:

Measurement of microdissected tissue area, RNA concentration and RNA integrity.

| Paraformaldehyde Solution | Carnoy’s Solution | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue | ASM | Epi | GF | ASM | Epi | GF |

| Number of microdissected area (n) | 10.21 ± 2.81 | 12.01 ± 3.1 | 4.6 ± 1.14 | 11.22 ± 2.7 | 13.18 ± 2.42 | 4.08 ± 1.24 |

| Concentration (ng/μl) | 0.42 ± 0.03 | 0.72 ± 0.11 | 1.04 ± 0.12 | 1.44 ± 0.13*** | 1.98 ± 0.24*** | 2.18 ± 0.46*** |

ASM; Airway smooth muscle, Epi; Epithelium, GF; Granulomatous foci. Data represented as Mean ± SEM of at least 06 mice samples per group;

p<0.001 paraformaldehyde vs Carnoy’s solution for respective group.

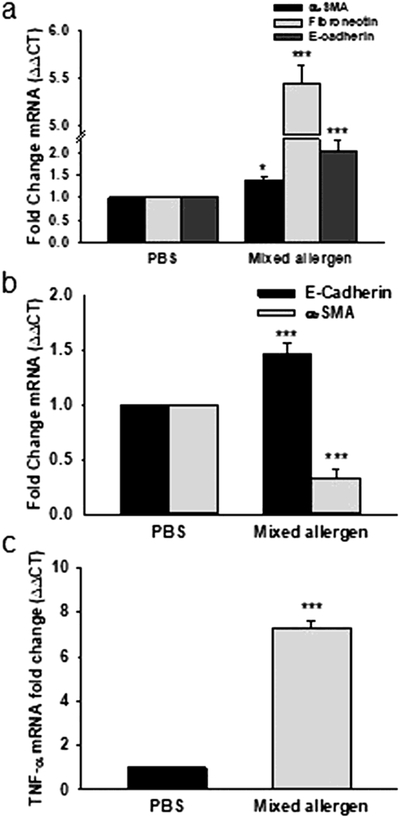

qRT-PCR for gene expression analysis in different cell types of mouse lung tissue

Mouse lung tissue collected from control and MA induced asthmatic mouse model and fixed with Carnoy’s solution resulted in better quality RNA isolated from three different cell types including airway smooth muscle cells, epithelium, and granulomatous foci. To evaluate the effectiveness of isolated RNA, we evaluated changes in various cellular specific gene expression in normal and pathological conditions in different cell types using qRT-PCR using s16 as a housekeeping gene. The primary focus of this current study was to optimize the LCM method to obtain good quality RNA to further study the downstream genetic changes in different airway cells during inflammation and normal condition. qRT-PCR data from RNA isolated from ASM cells revealed a significant increase (P<0.001) in α-smooth muscle actin, fibronectin and E-Cadherin in MA challenged mice compared to PBS treated mice (Figure 4a). Furthermore, epithelial cells isolated from airway showed a significant increase in expression of E-Cadherin, an important epithelium marker and significant low expression of α-SMA in MA challenged mice compared to PBS, indicating the homogenous cells with less contamination (Figure 4b). In an inflammatory condition, the granulomatous foci showed an increase in TNF-α gene expression. Concurrent with this, we observed that the expression of TNF-α was significantly (p<0.001) high in granulomatous foci in MA challenged mice than in PBS treated mice (Figure 4c).

Figure 4. Different cellular gene expression in LCM isolated mouse lung tissue.

Change in expression of different cellular genes are observed in accordance to treatment shows effectiveness of LCM and integrity of RNA. (a) In ASM cell expression of α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), fibronectin and E-cadherin is significantly changed. (b) Airway epithelium tissue showed increased expression of E-cadherin (epithelial marker) whereas decrease the α-SMA expression in MA treated group than the control. (c) Cell from Granulomatous foci showed high expression of TNFα gene in MA treated group compared to PBS. Data represented as Mean ± SEM of at least 06 mice per group; ***p<0.001, *p<0.05 PBS vs MA.

Discussion

LCM is a powerful technique that permits rapid dissection and isolation of specific tissues, cell organelles, and their fragments, which allow accurate examination of cellular genomic profiles by using qRT-PCR, RNA sequencing, genomics, and proteomics analysis. To process the prospective clinical tissue specimens the most commonly used methods in LCM studies is frozen tissue section. The major difficulty in carrying out this method is the tedious steps that required lots of attention which gives the high possibility of losing the yield and integrity of RNA prior to fixation and stabilization. Also, processing postoperative surgical specimens is very difficult with this method as it requires a multi-step process (Gautam et al. 2016). Multiple retrospectively collected clinical sample based studies require easy access, long-term storage and keeping up sample integrity. Limited studies have suggested the use of Carnoy’s solution for tissue fixation to overcome these limitations and provides the RNA stability and integrity (Cox et al. 2006).

Tissue fixation and processing method, together plays an important role in the protection and maintenance of tissue morphology at the cellular level that affects RNA quality. Investigators used different fixation systems depending on tissue type used to preserve the RNA integrity. Brown and Smith (2009) suggested to use high-salt buffer solution to fix rat brain tissue samples, whereas Santoro et al. (Santoro et al. 2018) used RNALater solution (Applied Biosystem, Foster City, CA, USA) to preserve skin biopsies for 1 week at 4°C to get stabilized RNA. In clinical studies most commonly used tissue preservation method is formalin fixation, however, it chemically alters the nucleotides inducing nucleic acid fragmentation and decrease RNA quality (Butler et al. 2016) for this reason it is not suitable for LCM studies. Very limited or no study attempted to optimize fixative solvent system for the lung tissue specimens in LCM studies.

The objective of this study was to optimize an appropriate tissue fixation solvent for lung tissue to support clinical setup as well our ongoing pulmonary research hypothesizing the role of sex hormones in lung physiology. The lung is comprised of multiple cells, so it is very crucial to identify the particular cell type responsible for altered physiology especially in the airway. In this, we utilized lung specimens from control and mixed allergen (MA) induced asthmatic C57BL6/J mouse model to optimize the RNA integrity. We used Carnoy’s solution or paraformaldehyde solution as fixative to determine the RNA integrity and optimized Carnoy’s solution is the best solvent for fixing tissue to perform LCM studies which provided good quality RNA for subsequent gene expression analysis. Selection of proper solvent system for tissue fixation is very important because RNA is a very labile biomolecule, and easily degraded, especially during LCM studies, where very low amounts of tissue material is collected. It is required to put special cautions to preserve RNA yield and integrity, which are decisive for downstream genomic studies. Solution used for tissue fixation in the study did not alter the tissue morphology and often is used in tissues subjected to LCM studies (Parlato et al. 2002). In the initial study, we found very low RNA integrity number (RIN) in LCM isolated cells from paraformaldehyde solution fixed mouse lung. PCR was performed in LCM isolated cells from paraformaldehyde fixed lung tissue and found highly variable CT value (ranges from 34–40) for s16 indicating the lower quality of RNA (Schroeder et al., 2006). Considering this fact, we could not able to get reliable qRTPCR data with cells isolated from paraformaldehyde fixed lung tissue.

RNA integrity number (RIN) represents the ratio of ribosomal subunit 26S and 18S, which measured at 1–10 scale. The higher RIN number represents a good quality of RNA. Ribosomal RNA is used as a standard for measuring the RNA quality and our study showed that using Carnoy’s solution for lung tissue fixation we got highest RNA yield and integrity (Kang et al. 2017; Kim et al. 2003; Shibutani et al. 2000). Further, to confirm the effectiveness of isolated RNA, we evaluated cellular gene expression in murine lung tissue by using different cell types like airway smooth muscle cells, epithelial cells and granulomatous foci under normal and pathological condition. Higher expression of α-SMA and fibronectin in airway smooth muscle cells concord with earlier reports suggesting increased airway remodeling genes in asthmatic condition. Whereas, RNA isolated from epithelium tissue showed epithelium marker E-cadherin and increased TNF-α expression in granulomatous foci upon MA exposure suggests quality and integrity of isolated RNA was optimum to evaluate downstream effects.

We optimized our protocol to reduce the impact of several events that affect the quality and quantity of RNA in lung tissue using LCM technique. With a small amount of RNA, we showed a difference in cellular genes as per pathophysiological condition by qRT-PCR, which shows the sensitivity of the optimized method. In the present study, we describe an optimized protocol using the Carnoy’s solution as a fixative solution for lung tissue to isolate RNA from ASM cells, epithelial and granulomatous foci. The fixative solution has major impact on RNA quality and integrity, Carnoy’s solution provides better RNA quality and integrity compared to paraformaldehyde in different lung cell types. Good quality RNA can provide a more accurate evaluation of cell specific downstream analysis, which offering the opportunity for more precise diagnostic and therapeutic approach in translational lung research.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Supported by NIH grants R01 HL123494 (Venkatachalem). Additional support in part from ND EPSCoR with NSF #1355466 and NDSU RCA Activity.

References:

- Amini P, Ettlin J, Opitz L, Clementi E, Malbon A, Markkanen E (2017) An optimised protocol for isolation of RNA from small sections of laser-capture microdissected FFPE tissue amenable for next-generation sequencing. BMC Mol Biol 18:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson SD (2010) Indirect challenge tests: Airway hyperresponsiveness in asthma: its measurement and clinical significance. Chest 138:25s–30s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antanaviciute A, Daly C, Crinnion LA, Markham AF, Watson CM, Bonthron DT, Carr IM (2015) GeneTIER: prioritization of candidate disease genes using tissue-specific gene expression profiles. Bioinformatics 31:2728–2735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardekani AM, Akhondi MM, Sadeghi MR (2008) Application of genomic and proteomic technologies to early detection of cancer. Arch Iran Med 11:427–434 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arthur G (2016) Albert Coons: harnessing the power of the antibody. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine 4:181–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bousquet J, Lacoste JY, Chanez P, Vic P, Godard P, Michel FB (1996) Bronchial elastic fibers in normal subjects and asthmatic patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 153:1648–1654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brioschi M, Eligini S, Crisci M, Fiorelli S, Tremoli E, Colli S, Banfi C (2014) A mass spectrometry-based workflow for the proteomic analysis of in vitro cultured cell subsets isolated by means of laser capture microdissection. Anal Bioanal Chem 406:2817–2825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown AL, Smith DW (2009) Improved RNA preservation for immunolabeling and laser microdissection. RNA 15(12): 2364–2374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler AE, Matveyenko AV, Kirakossian D, Park J, Gurlo T, Butler PC (2016) Recovery of high-quality RNA from laser capture microdissected human and rodent pancreas. J Histotechnol 39:59–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corces MR, Buenrostro JD, Wu B, Greenside PG, Chan SM, Koenig JL, Snyder MP, Pritchard JK, Kundaje A, Greenleaf WJ, Majeti R, Chang HY (2016) Lineage-specific and single-cell chromatin accessibility charts human hematopoiesis and leukemia evolution. Nat Genet 48:1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox ML, Schray CL, Luster CN, Stewart ZS, Korytko PJ, KN MK, Paulauskis JD, Dunstan RW (2006) Assessment of fixatives, fixation, and tissue processing on morphology and RNA integrity. Exp Mol Pathol 80:183–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon D, Zheng K, Costa J (2001) Rapid, efficient genotyping of clinical tumor samples by laser-capture microdissection/PCR/SSCP. Exp Mol Pathol 70:195–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domazet B, Maclennan GT, Lopez-Beltran A, Montironi R, Cheng L (2008) Laser capture microdissection in the genomic and proteomic era: targeting the genetic basis of cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 1:475–488 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmert-Buck MR, Bonner RF, Smith PD, Chuaqui RF, Zhuang Z, Goldstein SR, Weiss RA, Liotta LA (1996) Laser capture microdissection. Science 274:998–1001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatkin D, Seidman CE, Seidman JG (2014) Genetics and Disease of Ventricular Muscle. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine 4:a021063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautam V, Singh A, Singh S, Sarkar AK (2016) An Efficient LCM-Based Method for Tissue Specific Expression Analysis of Genes and miRNAs. Sci Rep 6:21577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hines EA, Sun X (2014) Tissue crosstalk in lung development. J Cell Biochem 115:1469–1477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang L, George P, Price DK, Sharakhov I, Michalak P (2017) Mapping Genomic Scaffolds to Chromosomes Using Laser Capture Microdissection in Application to Hawaiian Picture-Winged Drosophila. Cytogenet Genome Res 152:204–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerk NM, Ceserani T, Tausta SL, Sussex IM, Nelson TM (2003) Laser Capture Microdissection of Cells from Plant Tissues. Plant Physiol 132:27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerman IA, Buck BJ, Evans SJ, Akil H, Watson SJ (2006) Combining laser capture microdissection with quantitative real-time PCR: effects of tissue manipulation on RNA quality and gene expression. J Neurosci Methods 153:71–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JO, Kim HN, Hwang MH, Shin HI, Kim SY, Park RW, Park EY, Kim IS, Van Wijnen AJ, Stein JL, Lian JB, Stein GS, Choi JY (2003) Differential Gene Expression Analysis Using Paraffin-Embedded Tissues after Laser Microdissection. J Cellular Biochem 90:998–1006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lander ES (1996) The new genomics: global views of biology. Science 274:536–539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luz D, Ribeiro U Jr, Chassot C, De Salles Collet e Silva F, Cecconello I, Corbett C (2008) Carnoy’s solution enhances lymph node detection: an anatomical dissection study in cadavers. Histopathol 53:740–742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacArthur DG, Manolio TA, Dimmock DP, Rehm HL, Shendure J, Abecasis GR, Adams DR, Altman RB, Antonarakis SE, Ashley EA, Barrett JC, Biesecker LG, Conrad DF, Cooper GM, Cox NJ, Daly MJ, Gerstein MB, Goldstein DB, Hirschhorn JN, Leal SM, Pennacchio LA, Stamatoyannopoulos JA, Sunyaev SR, Valle D, Voight BF, Winckler W, Gunter C (2014) Guidelines for investigating causality of sequence variants in human disease. Nature 508:469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Byrne PM, Inman MD (2003) Airway hyperresponsiveness. Chest 123:411s–416s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oellrich A, Smedley D (2014) Linking tissues to phenotypes using gene expression profiles. Database (Oxford) 2014:bau017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parlato R, Rosica A, Cuccurullo V, Mansi L, Macchia P, Owens JD, Mushinski JF, De Felice M, Bonner RF, Di Lauro R (2002) A Preservation Method That Allows Recovery of Intact RNA from Tissues Dissected by Laser Capture Microdissection. Anal Biochem 300:139–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira MA, Dias AR, Faraj SF, Cirqueira CdS, Tomitao MT, Carlos Nahas S, Ribeiro U Jr, de Mello ES (2015) Carnoy’s solution is an adequate tissue fixative for routine surgical pathology, preserving cell morphology and molecular integrity. Histopathology 66:388–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoro S, Lopez ID, Lombardi R, Zauli A, Osiceanu AM, Sorosina M, Clarelli F, Peroni S, Cazzato D, Marchi M, Quattrini A, Comi G, Calogero RA, Lauria G, Martinelli Boneschi F (2018) Laser capture microdissection for transcriptomic profiles in human skin biopsies. BMC Mol Biol 19:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder A, Mueller O, Stocker S, Salowsky R, Leiber M, Gassmann M, Lightfoot S, Menzel W, Granzow M, Ragg T (2006) The RIN: an RNA integrity number for assigning integrity values to RNA measurements. BMC Mol Biol 7:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibutani M, Uneyama C, Miyazaki K, Toyoda K, Hirose M (2000) Methacarn Fixation: A Novel Tool for Analysis of Gene Expressions in Paraffin-Embedded Tissue Specimens. Lab Invest 80:199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi H, Kamakura H, Sato Y, Shiono K, Abiko T, Tsutsumi N, Nagamura Y, Nishizawa NK, Nakazono M (2010) A method for obtaining high quality RNA from paraffin sections of plant tissues by laser microdissection. J Plant Res 123:807–813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venter JC, Adams MD, Myers EW, Li PW, Mural RJ, Sutton GG, Smith HO, Yandell M, Evans CA, Holt RA, Gocayne JD, Amanatides P, Ballew RM, Huson DH, Wortman JR, Zhang Q, Kodira CD, Zheng XH, Chen L, Skupski M, Subramanian G, Thomas PD, Zhang J, Gabor Miklos GL, Nelson C, Broder S, Clark AG, Nadeau J, McKusick VA, Zinder N, Levine AJ, Roberts RJ, Simon M, Slayman C, Hunkapiller M, Bolanos R, Delcher A, Dew I, Fasulo D, Flanigan M, Florea L, Halpern A, Hannenhalli S, Kravitz S, Levy S, Mobarry C, Reinert K, Remington K, Abu-Threideh J, Beasley E, Biddick K, Bonazzi V, Brandon R, Cargill M, Chandramouliswaran I, Charlab R, Chaturvedi K, Deng Z, Francesco VD, Dunn P, Eilbeck K, Evangelista C, Gabrielian AE, Gan W, Ge W, Gong F, Gu Z, Guan P, Heiman TJ, Higgins ME, Ji R-R, Ke Z, Ketchum KA, Lai Z, Lei Y, Li Z, Li J, Liang Y, Lin X, Lu F, Merkulov GV, Milshina N, Moore HM, Naik AK, Narayan VA, Neelam B, Nusskern D, Rusch DB, Salzberg S, Shao W, Shue B, Sun J, Wang ZY, Wang A, Wang X, Wang J, Wei M-H, Wides R, Xiao C, Yan C, Yao A, Ye J, Zhan M, Zhang W, Zhang H, Zhao Q, Zheng L, Zhong F, Zhong W, Zhu SC, Zhao S, Gilbert D, Baumhueter S, Spier G, Carter C, Cravchik A, Woodage T, Ali F, An H, Awe A, Baldwin D, Baden H, Barnstead M, Barrow I, Beeson K, Busam D, Carver A, Center A, Cheng ML, Curry L, Danaher S, Davenport L, Desilets R, Dietz S, Dodson K, Doup L, Ferriera S, Garg N, Gluecksmann A, Hart B, Haynes J, Haynes C, Heiner C, Hladun S, Hostin D, Houck J, Howland T, Ibegwam C, Johnson J, Kalush F, Kline L, Koduru S, Love A, Mann F, May D, McCawley S, McIntosh T, McMullen I, Moy M, Moy L, Murphy B, Nelson K, Pfannkoch C, Pratts E, Puri V, Qureshi H, Reardon M, Rodriguez R, Rogers Y-H, Romblad D, Ruhfel B, Scott R, Sitter C, Smallwood M, Stewart E, Strong R, Suh E, Thomas R, Tint NN, Tse S, Vech C, Wang G, Wetter J, Williams S, Williams M, Windsor S, Winn-Deen E, Wolfe K, Zaveri J, Zaveri K, Abril JF, Guigó R, Campbell MJ, Sjolander KV, Karlak B, Kejariwal A, Mi H, Lazareva B, Hatton T, Narechania A, Diemer K, Muruganujan A, Guo N, Sato S, Bafna V, Istrail S, Lippert R, Schwartz R, Walenz B, Yooseph S, Allen D, Basu A, Baxendale J, Blick L, Caminha M, Carnes-Stine J, Caulk P, Chiang Y-H, Coyne M, Dahlke C, Mays AD, Dombroski M, Donnelly M, Ely D, Esparham S, Fosler C, Gire H, Glanowski S, Glasser K, Glodek A, Gorokhov M, Graham K, Gropman B, Harris M, Heil J, Henderson S, Hoover J, Jennings D, Jordan C, Jordan J, Kasha J, Kagan L, Kraft C, Levitsky A, Lewis M, Liu X, Lopez J, Ma D, Majoros W, McDaniel J, Murphy S, Newman M, Nguyen T, Nguyen N, Nodell M, Pan S, Peck J, Peterson M, Rowe W, Sanders R, Scott J, Simpson M, Smith T, Sprague A, Stockwell T, Turner R, Venter E, Wang M, Wen M, Wu D, Wu M, Xia A, Zandieh A, Zhu X (2001) The Sequence of the Human Genome. Science 291:130411181995 [Google Scholar]

- Yarova PL, Stewart AL, Sathish V, Britt RD, Thompson MA, Lowe AP, Freeman M, Aravamudan B, Kita H, Brennan SC (2015) Calcium-sensing receptor antagonists abrogate airway hyperresponsiveness and inflammation in allergic asthma. Sci Trans Med 7:284ra260–284ra260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaidi S, Choi M, Wakimoto H, Ma L, Jiang J, Overton JD, Romano-Adesman A, Bjornson RD, Breitbart RE, Brown KK, Carriero NJ, Cheung YH, Deanfield J, DePalma S, Fakhro KA, Glessner J, Hakonarson H, Italia MJ, Kaltman JR, Kaski J, Kim R, Kline JK, Lee T, Leipzig J, Lopez A, Mane SM, Mitchell LE, Newburger JW, Parfenov M, Pe’er I, Porter G, Roberts AE, Sachidanandam R, Sanders SJ, Seiden HS, State MW, Subramanian S, Tikhonova IR, Wang W, Warburton D, White PS, Williams IA, Zhao H, Seidman JG, Brueckner M, Chung WK, Gelb BD, Goldmuntz E, Seidman CE, Lifton RP (2013) De novo mutations in histone-modifying genes in congenital heart disease. Nature 498:220–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]